Abstract

Purpose

To identify novel breast cancer subtypes by extracting quantitative imaging phenotypes of the tumor and surrounding parenchyma, and to elucidate the underlying biological underpinnings and evaluate the prognostic capacity for predicting recurrence-free survival (RFS).

Methods

We retrospectively analyzed dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging data of patients from a single-center discovery cohort (n=60) and an independent multi-center validation cohort (n=96). Quantitative image features were extracted to characterize tumor morphology, intra-tumor heterogeneity of contrast agent wash-in/wash-out patterns, and tumor-surrounding parenchyma enhancement. Based on these image features, we used unsupervised consensus clustering to identify robust imaging subtypes, and evaluated their clinical and biological relevance. We built a gene expression-based classifier of imaging subtypes and tested their prognostic significance in five additional cohorts with publically available gene expression data but without imaging data (n=1160).

Results

Three distinct imaging subtypes, i.e., homogeneous intratumoral enhancing, minimal parenchymal enhancing, and prominent parenchymal enhancing, were identified and validated. In the discovery cohort, imaging subtypes stratified patients with significantly different 5-year RFS rates of 79.6%, 65.2%, 52.5% (logrank P=0.025), and remained as an independent predictor after adjusting for clinicopathological factors (hazard ratio=2.79, P=0.016). The prognostic value of imaging subtypes was further validated in five independent gene expression cohorts, with average 5-year RFS rates of 88.1%, 74.0%, 59.5% (logrank P from <0.0001 to 0.008). Each imaging subtype was associated with specific dysregulated molecular pathways that can be therapeutically targeted.

Conclusion

Imaging subtypes provide complimentary value to established histopathological or molecular subtypes, and may help stratify breast cancer patients.

Keywords: Imaging subtype, consensus clustering, pathway analysis, breast cancer, prognostic biomarker

Introduction

Breast cancer is routinely divided into several subtypes based on clinical and pathological factors such as hormone receptor and HER2 status, which are used to determine appropriate therapy and guide clinical decision-making(1,2). Gene expression profiling of breast cancer has identified four intrinsic molecular subtypes (luminal A, luminal B, HER2-enriched, and basal-like), each associated with distinct gene expression patterns, prognosis, and response to treatment(3,4). However, molecular tests are limited by the requirement for invasive biopsy or surgery, and surrogate subtypes based on routinely measured tumor markers (estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, HER2) do not fully approximate the intrinsic subtypes. Moreover, recent studies have shown profound intra-tumor genetic heterogeneity in breast cancer(5,6), which poses a significant challenge for molecular profiling based on a single biopsy. There is a critical need for reliable, noninvasive prognostic or predictive biomarkers that can aid in patient stratification.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) plays an important role in breast cancer management, from the initial diagnosis to the evaluation of therapy response(7–10). MRI is exquisitely sensitive to physiological changes (e.g., blood flow) in the underlying tissue, and is well suited for noninvasive characterization of the tumor. One important advantage of MRI over biopsy-derived molecular data is that imaging provides a global, unbiased view of the entire tumor as well as its surrounding tissue. Beyond visual assessment by radiologists, quantitative image analysis may reveal additional useful biomarkers in cancer(11–14). Recent studies have shown that intra-tumor imaging heterogeneity, which might reflect underlying genetic heterogeneity, is associated with aggressive disease, resistance to chemotherapy, and poor prognosis(15–21). There is also emerging evidence suggesting that imaging characteristics of breast parenchyma are associated with the risk of developing breast cancer, treatment response, long-term disease recurrence, and patient survival(22–24).

The availability of large-scale curated image and gene expression datasets has spurred a significant interest in linking tumor phenotypes at the molecular and tissue (imaging) level(14,25–34). These studies used a similar study design to identify the correlation of individual imaging features with specific molecular features, such as gene expression, mutation, or predefined molecular subtypes. Significant associations have been identified in breast cancer(31,32,34), leading to an improved understanding of the molecular mechanisms behind imaging phenotypes.

In this study, we aim to discover novel breast cancer subtypes by extracting quantitative image phenotypes of the tumor as well as the breast parenchyma for a detailed characterization of the tumor and its invasion into surrounding tissue. By creating an imaging-genomic association map, we show that the imaging subtypes are associated with differing molecular pathways, and that patients stratified by the imaging subtypes have distinct prognoses in multiple independent cohorts.

Materials and Methods

Study design

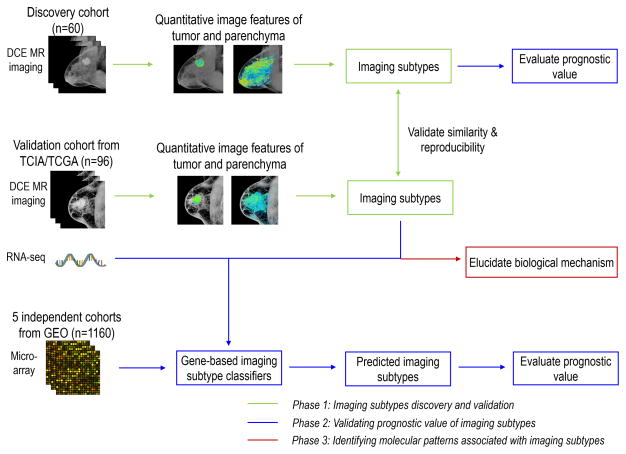

We aimed to discover novel breast cancer subtypes defined by quantitative imaging features, investigate the prognostic relevance of these imaging subtypes, and explore their underlying biological mechanism. To do this, we carried out this study in three phases, as shown in Fig. 1. In phase one, we independently explored intrinsic imaging subtypes of breast cancer in discovery (single institutional) and validation (The Cancer Genome Atlas [TCGA]) cohorts based on unsupervised clustering of quantitative imaging features, and further validated the similarity and reproducibility of the imaging subtypes across these two cohorts. See Supplementary Methods for details of the two patients’ cohorts. In phase two, the prognostic value of the imaging subtypes was investigated in its ability to stratify recurrence-free survival in 1) discovery cohort, and 2) five additional gene expression datasets. In phase three, we explored the biological mechanism associated with the discovered imaging subtypes through two types of pathway analyses. The details of each phase are elaborated in the following.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the overall design of the study. This study contains three phases. Abbreviations: DCE = Dynamic contrast-enhanced, TCIA = The Cancer Imaging Archive, TCGA = The Cancer Genome Atlas, GEO = Gene Expression Omnibus.

Overview of patient cohorts

The overall study design is shown in Fig. 1. We retrospectively analyzed two publicly accessible breast cancer imaging cohorts from The Cancer Imaging Archive (TCIA). Sixty patients from a single institution were used as the imaging subtype discovery cohort, for which both imaging and recurrence-free survival (RFS) data were available. Another 96 patients from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) were used as the imaging subtype validation cohort, for which both imaging and gene expression data were available. Patient characteristics of these two cohorts are summarized in Supplementary Table S1 (see Supplementary Methods for patient selection and imaging protocols). To validate the prognostic relevance of the imaging subtypes, we identified five publicly available datasets comprising microarray gene expression profiles for a total of 1160 breast cancer patients, for whom the RFS information was available. Among them, the Netherlands Cancer Institute (NKI) dataset (295 patients) was obtained from the NKI homepage (http://ccb.nki.nl/data, accessed April 1, 2016). The other four datasets were retrieved from the Gene Expression Omnibus (series accession numbers: GSE1456 [159 patients], GSE25055 [310 patients], GSE25065 [198 patients], GSE7390 [198 patients]).

Image analysis and feature extraction

We analyzed each patient’s dynamic contrast-enhanced (DCE) MR images in three steps: 1) tumor and background parenchyma segmentation, 2) image preprocessing and harmonization, and 3) quantitative image feature extraction. In step 1, two radiologists (G. C. and X. S. with 17 and 11 years of experience in breast imaging) blinded to the patients’ clinical outcome, i.e., recurrence-free survival, manually delineated the tumor in a slice-by-slice manner on the DCE MRI and reached consensus regarding the tumor contours. The background parenchyma ipsilateral to tumor was automatically segmented using fuzzy c-means (35) and confirmed by both radiologists in consensus (see details in Supplementary Methods). In step 2, the image data were harmonized via a series of imaging processing algorithms, which allows subsequent quantitative image analysis. First, the temporal sequences for the DCE MR imaging were extracted at three time points, including the pre-contrast, early post-contrast (around 2.5 min) and late post-contrast (around 7.5 min). The N4 bias correction (36) was used to remove the shading artifacts in the MR images. Then each of the three sequential MR images was normalized by the average pixel value of breast parenchyma in pre-contrast images. The DCE MR images were resized to an isotropic voxel resolution of 0.8 mm to allow for consistent calculation of image features. In step 3, a set of 110 quantitative image features were extracted to characterize the phenotypes of each tumor and its parenchymal enhancement as well as intra-tumor heterogeneity. The feature set contains 8 tumor morphological features, 66 tumor texture features of kinetic maps including wash-in/wash-out and signal enhancement ratio (SER) maps, 4 functional tumor volume features, 10 background parenchymal enhancement features, and 22 tumor-surrounding parenchymal enhancement features. The details of the image features are explained in Supplementary Table S2. The image analysis and feature extraction were implemented with MATLAB (MathWorks, Natick, Massachusetts).

Imaging subtype discovery and validation

We used unsupervised consensus clustering (37) to discover intrinsic imaging subtypes for the discovery and validation cohorts, respectively. Compared with traditional k-mean and hierarchical clustering algorithms, consensus clustering is shown to be more robust and insensitive to random starts, and has been widely used to identify biologically meaningful clusters (37). In details, we used the partition-around-medoids clustering algorithm (38) with the Euclidean distance metric and performed 10,000 bootstraps with 80% item resampling of the quantitative imaging features. We varied the cluster number from 2 to 10 and selected the optimal cluster number that produced the most stable consensus matrices and the most unambiguous cluster assignments across permuted clustering runs (37). The final clusters identified as such correspond to imaging subtypes of breast cancer. Further, the same procedure was independently implemented in the validation cohort to determine and validate the imaging subtypes. The significance analysis of microarrays (SAM) algorithm (39) was used to identify the quantitative image features significantly associated with the identified imaging subtypes. SAM is a permutation-based non-parametric statistical algorithm and designed to identify significantly different variables (imaging features) that are associated with a given trait (imaging subtype). The in-group proportion (IGP) statistic(40) was used to test whether similar imaging subtypes from the discovery cohort existed in the validation cohort. The IGP quantitatively measure the similarity of clusters when defined using training and testing data. If the clusters are identical between two data sets, the IGP approaches to 100%. The consensus clustering, SAM algorithm, and IGP statistic were performed in R.

Prognostic significance of the imaging subtypes

We first evaluated the imaging subtypes in terms of their prognostic capacity for predicting recurrence-free survival in the discovery cohort. Then, we tested the prognostic relevance of the imaging subtypes on 5 additional breast cancer cohorts with gene expression data publically available but no imaging data available. To do this, we first built a gene expression-based imaging subtype classifier using clustered imaging subtype labels and gene expression data (RNA-seq) from the TCGA cohort. Specifically, we performed one-way ANOVA with fixed-effect (41) to first identify genes significantly associated with imaging subtypes (P<0.05). Then we trained a nearest shrunken centroid classifier (42) with the preselected genes and validated it using 10-fold cross validation with stratified sampling. We subsequently applied this classifier to the microarray datasets to classify each patient into one of the three imaging subtypes and evaluated their prognostic value in stratifying recurrence-free survival (RFS). In order to account for the different dynamic ranges of RNA-seq and DNA microarray data, we performed copula transformation (43) to each gene, respectively and independently for each dataset so that they were comparable in the classification model (Supplemental Methods).

Identifying molecular pathways associated with the imaging subtypes

We performed two types of pathway analyses to elucidate the biological mechanisms of the imaging findings. First, we used the Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) to identify enriched biological pathways associated with each imaging subtype within the TCGA cohort. The gene expression data of normal breast tissue available for 113 patients, were set as the baseline. Then the samples from the tumor tissue were compared to the paired normal tissue, respectively in each imaging subtype. The KEGG pathway database was used for GSEA. Second, we integrated gene expression and copy number variation (CNV) data with Pathway Recognition Algorithm Using Data Integration on Genomic Models (PARADIGM)(44). The NCI Pathway Interaction Database was used for PARADIGM analysis. See details in Supplementary Methods.

Statistical analysis

We used the Cox proportional hazard model to build survival model to predict recurrence-free survival (RFS). Kaplan-Meier analysis and logrank test were used to evaluate patient stratification into different survival groups. To adjust for multiple statistical testing, the Benjamini-Hochberg method was used to control the false discovery rate (FDR) on univariate analysis. All statistical tests were two-sided, with a p-value less than 0.05 or FDR less than 0.25 considered statistically significant. The rationale of using a larger threshold for FDR is to increase the likelihood of positive findings. All statistical analyses were performed in R.

Results

Three imaging subtypes emerge in the discovery cohort

Based on consensus clustering of the patients’ quantitative imaging features characterizing both tumor and surrounding parenchyma, we determined the optimal cluster number to be three. The three-cluster solution corresponded to the largest cluster number that induced the smallest incremental change in the area under the under cumulative distribution function (CDF) curves, while maximizing consensus within clusters and minimizing the rate of ambiguity in cluster assignments, as shown in Fig. 2A–B. This resulted in 18 patients (30%) in cluster 1, 19 patients (32%) in cluster 2, and 23 patients (38%) in cluster 3 for the discovery cohort.

Figure 2.

Unsupervised consensus clustering of quantitative imaging phenotypes. A) and C) The consensus matrices represented as heat maps for the chosen optimal cluster number (k = 3) for discovery and validation cohorts respectively. Patient samples are both rows and columns, and consensus values range from 0 (never grouped together) to 1 (always clustered together). The dendrogram above the heat map illustrates the ordering of patient samples in three clusters. B) and D) The corresponding relative change in area under the cumulative distribution function (CDF) curves when cluster number changing from k to k+1. The range of k changed from 2 to 10, and the optimal k = 3.

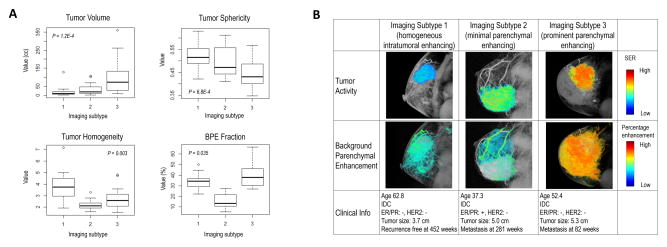

The significance analysis of microarrays (SAM)(39) identified quantitative image features significantly associated with each imaging subtype (Supplementary Fig. S1). The boxplot of four representative imaging features was shown in Fig. 3A, for which there were significant differences (ANOVA P<0.05) across the subtypes. In particular, imaging subtype 1 was characterized by the lowest intratumoral heterogeneity compared with others (Wilcox P<2.2E-16), and hence was named ‘homogeneous intratumoral enhancing subtype’. Imaging subtype 2 was characterized by the lowest amount of background parenchymal enhancement (BPE) compared with others (Wilcox P=0.0002), and was named ‘minimal parenchymal enhancing subtype’. Compared with subtype 2, subtype 3 was characterized by a higher amount of BPE (Wilcox P=5.49E-16), and was named ‘prominent parenchymal enhancing subtype’. These patterns were consistent in the validation cohort (Supplementary Fig. S2). Images of typical patients from three subtypes are shown in Fig. 3B.

Figure 3.

A) Selected four quantitative imaging features significantly associated with three imaging subtypes, including tumor volume, tumor sphericity, tumor homogeneity measured at early enhancement phase, and background parenchymal enhancement (BPE) fraction with percentage enhancement > 0.6. B) Details of analyzing the tumor and BPE for a representative patient from each imaging subtype. The tumor active function was measured and color-coded with signal enhancement ratio (SER). The BPE was measured and color coded with percentage enhancement at early enhancement phase.

Imaging subtypes are validated in an external multi-institutional cohort

We independently applied the same consensus clustering analysis to the multi-institutional TCGA cohort, and determined the optimal cluster number to be three, as shown in Fig. 2C–D. The in-group proportion (IGP) statistic(40) was used to evaluate the reproducibility of the imaging subtypes across the discovery and validation cohorts. Imaging subtypes 1 and 2 showed a high consistency between the two cohorts, with the corresponding IGP values at 82.4% and 92.3%, respectively. On the other hand, imaging subtype 3 was associated with a lower IGP of 60.0%, suggesting a large degree of inter-tumor phenotypic heterogeneity among this group. All three imaging subtypes were statistically significant, with P < 0.01, P < 0.001, and P < 0.05 for each subtype respectively.

Imaging subtypes are distinct from established breast cancer subtypes

The three imaging subtypes were not associated with intrinsic molecular subtypes (Pearson’s Chi-square P = 0.865) or immunohistochemistry (IHC) based measurements such as ER, PR, HER2 (Pearson’s Chi-square P > 0.05). Every imaging subtype contained all molecular subtypes and all IHC-based subtypes, and vice versa (Supplementary Table S3 and S4). Additionally, the imaging subtypes were not associated with the BI-RADS based characteristics including tumor shape, margin and internal enhancement patterns (Pearson’s Chi-squared test P = 0.344, 0.769, 0.432, respectively).

Imaging subtypes stratify patients in terms of recurrence-free survival (RFS) in the discovery cohort

We observed significant differences in recurrence-free survival (logrank P = 0.025) in the discovery cohort (Fig. 4A), with 5-year RFS rates of 79.6%, 65.2%, 52.5% for Subtype 1, 2, 3, respectively. On univariate analysis, imaging subtype was a strong predictor of RFS (hazard ratio: 2.11, 95% confidence interval: [1.19, 3.71], P = 0.01). On multivariate analysis, imaging subtype was the only independent predictor of RFS (P = 0.016) after adjusting for clinical and pathological factors, including patients’ age, receptor status, histologic type, and lymph node involvement (Table 1).

Figure 4.

Kaplan-Meier curves of recurrence-free survival stratified by the imaging subtypes. The plots are for A) the discovery cohort, and B–F) five independent validation cohorts, with predicted imaging subtypes via gene expression-based imaging subtype classifiers built in TCGA cohort.

Table 1.

Univariate and multivariate analyses of the imaging subtype and clinical risk factors for predicting recurrence-free survival in the discovery cohort.

| Predictors | Univariate | Multivariate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P Value | HR | 95% CI | P Value | |

| Imaging subtype† | 2.11 | 1.19 – 3.71 | 0.010 * | 2.79 | 1.21 – 6.44 | 0.016 * |

| Age | 0.79 | 0.53 – 1.19 | 0.260 | 0.57 | 0.30 – 1.09 | 0.087 |

| ER | 0.60 | 0.23 – 1.55 | 0.289 | 0.57 | 0.11 – 2.95 | 0.499 |

| PR | 0.67 | 0.25 – 1.75 | 0.409 | 0.30 | 0.06 – 1.50 | 0.143 |

| HER2 | 0.75 | 0.24 – 2.29 | 0.610 | 0.49 | 0.10 – 2.34 | 0.370 |

| Histologic type‡ | 0.97 | 0.42 – 2.24 | 0.940 | 0.73 | 0.23 – 2.34 | 0.602 |

| Lymph node status | 3.43 | 1.16 – 10.14 | 0.026 * | 3.42 | 0.64 – 18.20 | 0.149 |

| Molecular subtype†† | 1.49 | 0.84 – 2.65 | 0.177 | - | - | - |

Note:

indicates p-value < 0.05;

Image subtype was treated as a continuous variable, i.e., subtype 1 was coded as 1, subtype 2 was coded as 2, subtype 3 was coded as 3;

the invasive ductal carcinoma was coded as 1, other types as 0;

molecular subtype includes luminal, HER2+ and triple negative, and it was not adjusted in multivariate analysis;

Gene expression-based imaging subtype classifier predicted RFS in 5 independent cohorts

We identified 692 genes whose expression was significantly associated with the imaging subtypes using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), and trained a nearest shrunken centroid classifier(42) to predict imaging subtypes based on the selected genes in the TCGA cohort. This gene expression-based classifier had an accuracy of 90.6%, 75.0%, and 82.3% in predicting each imaging subtype based on 10-fold cross validation. We then applied the classifier to 5 independent microarray datasets respectively, in order to assign each patient into one of the three imaging subtypes. Patient stratification based on the predicted imaging subtypes showed significantly different RFS in all 5 datasets (Fig. 4B–F, logrank P ranging from 1.16e-6 to 7.92e-3), with average 5-year RFS rates of 88.1%, 74.0%, 59.5% for Subtype 1 to 3, respectively. Further, the patterns of RFS were consistent with those in the discovery cohort (subtype 1, 2, and 3 corresponding to favorable, intermediate, and poor prognosis).

Imaging subtypes are associated with distinct molecular pathways

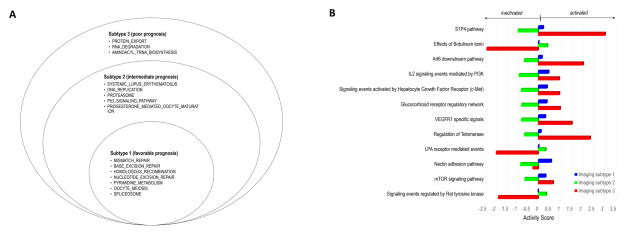

Fig. 5A shows the molecular pathways significantly enriched in each imaging subtype (FDR < 0.25) based on gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA). The number of enriched pathways progressively increased from Subtype 1 through Subtype 3 (Fig. 5A and Supplementary Table S5). In addition, we combined gene expression and copy number variation data and computed the pathway activity scores for each imaging subtype using the Pathway Recognition Algorithm Using Data Integration on Genomic Models (PARADIGM)(44). Again, we observed a clear trend: the number and activity (or inactivity) of dysregulated pathways (FDR < 0.25) progressively increased from Subtype 1 through Subtype 3 (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

A) Stacked Venn plots of the significantly associated (FDR < 25%) KEGG pathways for three imaging subtypes with Gene Set Enrichment Analysis. B) Pathway activity scores for three imaging subtypes. The pathways are from NCI Pathway Interaction Database Pathways, which are significantly (FDR<25%) associated with three imaging subtypes with PARADIGM analysis. The bar length indicates the magnitude of activity score. From two independent pathway analyses, we observed consistent pathway dysregulation patterns across imaging subtypes, which might explain the differential prognoses associated with the three imaging subtypes.

Discussion

We discovered three subtypes of breast cancer based on quantitative imaging phenotypes of the tumor and surrounding parenchymal tissue, and validated these imaging subtypes in an independent multi-institutional cohort. We showed that the imaging subtypes were associated with distinct molecular pathways and provided independent prognostic value beyond conventional clinicopathological factors. Further, by building a gene expression-based imaging subtype classifier, we showed that the imaging subtypes stratified RFS in five independent cohorts totaling >1,000 patients. These newly identified imaging subtypes and associated findings warrant further validation in large prospective studies, and if successful, may serve as useful biomarkers for personalized management of breast cancer.

Our findings offer an intriguing perspective on the biology of breast cancer. The three imaging subtypes shared several disturbances in biological pathways that are implicated in breast cancer, including DNA damage repair, pyrimidine metabolism, oocyte meiosis, and spliceosome (Fig. 5A). Malfunction of DNA damage repair can lead to mutation and chromosomal instability, a hallmark of oncogenesis and tumor progression(45). Pyrimidine metabolism is a limiting step for DNA replication during mitosis(46). The disturbance of pyrimidine metabolism is consistent with the fact that the antimetabolite drugs such as fluorouracil and capecitabine are often effective treatments for breast cancer(47). Additionally, there is evidence showing that the extent of dysregulation of genes involved in the spliceosome correlates with the malignant behavior of breast cancer(48). In Subtypes 2 and 3 (but not in Subtype 1), the immune pathway of systemic lupus erythematosus was found to be disturbed, which might correspond to the enhanced intratumoral angiogenesis observed in these two subtypes(49). In Subtype 3 (but not in Subtypes 1 or 2), the protein export pathway was disturbed. During tumor progression, cancer cells activate immune infiltrate and endothelial cells to increase the secretion and export of proteins into the tumor microenvironment, such as cytokines and angiogenesis factors that promote tumor growth (50). The disturbed pathways in Subtypes 2 and/or 3 could be the biological reasons for their distinct imaging phenotypes and might explain their differential prognoses. Our study thus provides novel insight into the biological processes associated with the aggressiveness of breast cancers.

Our results show that imaging phenotypes may be used to infer dysregulated molecular pathways that can be targeted (Fig. 5B). For example, imaging Subtype 3 was characterized by the up-regulation of the c-Met, PI3K, and mTOR pathways. Targeted therapies inhibiting these pathways are being actively tested in clinical trials(51–53). Such therapies might prove to be most effective in Subtype 3, which had the worst prognosis, whereas in Subtype 2 they might prove not be effective due to inactivation of the corresponding pathways. Compared with Subtypes 1 and 2, Subtype 3 had reduced reproducibility across discovery and validation cohorts. This might reflect greater phenotypical diversity or inter-tumor heterogeneity among this group, implying that combinatory therapies targeting multiple pathways may be needed for Subtype 3.

Based on two independent pathway analyses (Fig. 5A and 5B), we showed that the number and activity of dysregulated biological pathways had similar patterns across imaging subtypes, which was consistent with their differential prognoses. Our findings support the potential of imaging analysis to inform clinical trial design, and ultimately to help guide precision therapy of breast cancer.

The proposed image-based subtyping overcomes several key challenges of current approaches for breast cancer classification. Traditional analysis requires molecular profiling of the tumor sampled in a small biopsy, which is limited by intra-tumor genetic heterogeneity(5,6,54,55) and other confounders such as normal tissue contamination, making downstream class discovery susceptible to sampling errors. By contrast, imaging provides a complete, unbiased picture of the tumor. Thus, subtypes defined by quantitative imaging phenotypes may be more reliable. Our results show that imaging subtypes were distinct from established IHC-based or molecular subtypes, suggesting that imaging could provide complementary prognostic information. One key issue with image-based markers is that the scanner and acquisition protocols such as MR field strengths are often quite heterogeneous, and these variations could limit the study power especially in multi-institutional retrospective studies. Appropriate standardization and harmonization of imaging data are critical to ensure more reliable results. Another important advantage of our approach is that imaging is often used clinically for treatment response evaluation and long-term follow-up(9,13). This opens the door to noninvasive disease monitoring using imaging subtypes as surrogate markers of underlying molecular activity, which would be far more tolerable to patients than frequent invasive biopsies.

Our work represents a major shift in direction from traditional imaging genomics studies. Instead of finding imaging features associated with predefined genomic properties, here we started with an extensive characterization of imaging phenotypes and applied unsupervised clustering for subtype discovery. A previous study used a similar approach to identify imaging subtypes for glioblastoma multiforme (GBM)(56). Beside the apparent differences in cancer types (GBM versus breast cancer) and imaging modalities (anatomical versus functional MRI), there are several important strengths of our study: 1) our image analysis extended beyond the tumor and included background breast parenchyma, thus providing a more detailed imaging characterization of tumor invasion into surrounding tissue; 2) we built gene expression-based imaging subtype classifiers and validated the prognostic significance of these subtypes in multiple independent cohorts. One recent breast cancer radiogenomic study (32) aimed to identify the genomic underpinnings associated with individual MRI-based radiomic features. On the other hand, our study focused on discovering clinically relevant breast cancer subtypes based on imaging phenotypes, which can be directly used to stratify patients. While our radiogenomic study included molecular features such as gene expression and copy number variation, it may be beneficial to incorporate other types of –omic data (32) such as genetic mutation, miRNA expression, and protein expression, which could provide a more complete picture of the molecular characteristics. Similar to previous radiogenomic studies, our work identified correlative but not necessarily causative relations between imaging phenotypes and molecular features. In order to mechanistically validate these imaging genomic associations, experimental validation using a preclinical knock-out model will be required, and this warrants further investigation in future studies.

Conclusions

We have identified three breast cancer subtypes based on quantitative imaging phenotypes of the tumor and surrounding tissue. The three imaging subtypes reflect distinct underlying molecular pathways, and are associated with significantly different survival. This work may serve as the basis for future prospective studies to evaluate the imaging subtypes as potential biomarkers for precision medicine.

Supplementary Material

Translational relevance.

Breast cancer is a heterogeneous disease. Biomarkers that stratify patients with clinical relevance are critically needed for precision medicine. Molecular profiling is currently used to stratify breast cancer, but is limited by the requirement for invasive biopsy and confounded by intra-tumor genetic heterogeneity. Conversely, imaging provides a global, unbiased picture of the entire tumor. Using unsupervised consensus clustering of quantitative imaging phenotypes of the tumor and parenchyma, we identify three imaging subtypes in a single-institution cohort, and validate them in an independent multi-institutional cohort. Each imaging subtype is associated with distinct molecular pathways with therapeutic implications. Further, we show that imaging subtypes and their gene expression-based classifiers predict patient survival in a discovery cohort and five external validation cohorts, respectively. Our method can potentially stratify patients noninvasively for personalized management of breast cancer.

Acknowledgments

Financial support

This research was partially supported by the NIH grant number R01 CA193730.

The authors thank The Cancer Imaging Archive (TCIA) for providing the breast cancer cases enrolled in The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) study and the UCSF study.

Footnotes

Disclaimers

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

J.W., Y.C., and R.L. conceived and designed research. J.W., X.S., and G.C. acquired MRI and performed annotations and preprocessing. J.W., Y.C., and B.L. collected genomic data and provided bioinformatics analysis. J.W. and R.L. integrated and analyzed the data. D.M.I. and A.W.K. provided expert knowledge. J.W., Y.C., B.L., and R.L., wrote the manuscript. All authors edited and approved the manuscript.

References

- 1.Hammond ME, Hayes DF, Dowsett M, Allred DC, Hagerty KL, Badve S, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology/College Of American Pathologists guideline recommendations for immunohistochemical testing of estrogen and progesterone receptors in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(16):2784–95. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.6529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harris LN, Ismaila N, McShane LM, Andre F, Collyar DE, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, et al. Use of biomarkers to guide decisions on adjuvant systemic therapy for women with early-stage invasive breast cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2016:JCO652289. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2016.010868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sotiriou C, Pusztai L. Gene-expression signatures in breast cancer. New Engl J Med. 2009;360(8):790–800. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0801289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Voduc KD, Cheang MC, Tyldesley S, Gelmon K, Nielsen TO, Kennecke H. Breast cancer subtypes and the risk of local and regional relapse. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(10):1684–91. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.9284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barry WT, Kernagis DN, Dressman HK, Griffis RJ, J’Vonne DH, Olson JA, et al. Intratumor heterogeneity and precision of microarray-based predictors of breast cancer biology and clinical outcome. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(13):2198–206. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.7245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zardavas D, Irrthum A, Swanton C, Piccart M. Clinical management of breast cancer heterogeneity. Nature reviews Clinical oncology. 2015;12(7):381–94. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2015.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hylton N. Dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging as an imaging biomarker. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(20):3293–8. doi: 10.1200/Jco2006.06.8080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhooshan N, Giger ML, Jansen SA, Li H, Lan L, Newstead GM. Cancerous breast lesions on dynamic contrast-enhanced MR images: computerized characterization for image-based prognostic markers. Radiology. 2010;254(3):680–90. doi: 10.1148/radiol.09090838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hylton NM, Blume JD, Bernreuter WK, Pisano ED, Rosen MA, Morris EA, et al. Locally Advanced Breast Cancer: MR Imaging for Prediction of Response to Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy-Results from ACRIN 6657/I-SPY TRIAL. Radiology. 2012;263(3):663–72. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12110748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li X, Abramson RG, Arlinghaus LR, Kang H, Chakravarthy AB, Abramson VG, et al. Multiparametric Magnetic Resonance Imaging for Predicting Pathological Response After the First Cycle of Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in Breast Cancer. Invest Radiol. 2015;50(4):195–204. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0000000000000100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yankeelov TE, Mankoff DA, Schwartz LH, Lieberman FS, Buatti JM, Mountz JM, et al. Quantitative imaging in cancer clinical trials. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22(2):284–90. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-3336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gillies RJ, Kinahan PE, Hricak H. Radiomics: Images Are More than Pictures, They Are Data. Radiology. 2016 doi: 10.1148/radiol.2015151169. Ahead of Print:151169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hylton NM, Gatsonis CA, Rosen MA, Lehman CD, Newitt DC, Partridge SC, et al. Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy for Breast Cancer: Functional Tumor Volume by MR Imaging Predicts Recurrence-free Survival—Results from the ACRIN 6657/CALGB 150007 I-SPY 1 TRIAL. Radiology. 2015:150013. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2015150013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aerts HJ, Velazquez ER, Leijenaar RT, Parmar C, Grossmann P, Cavalho S, et al. Decoding tumour phenotype by noninvasive imaging using a quantitative radiomics approach. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4006. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O’Connor JP, Rose CJ, Waterton JC, Carano RA, Parker GJ, Jackson A. Imaging intratumor heterogeneity: role in therapy response, resistance, and clinical outcome. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21(2):249–57. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-0990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fehr D, Veeraraghavan H, Wibmer A, Gondo T, Matsumoto K, Vargas HA, et al. Automatic classification of prostate cancer Gleason scores from multiparametric magnetic resonance images. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2015;112(46):E6265–E73. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1505935112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Agner SC, Rosen MA, Englander S, Tomaszewski JE, Feldman MD, Zhang P, et al. Computerized image analysis for identifying triple-negative breast cancers and differentiating them from other molecular subtypes of breast cancer on dynamic contrast-enhanced MR images: a feasibility study. Radiology. 2014;272(1):91–9. doi: 10.1148/radiol.14121031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sutton EJ, Oh JH, Dashevsky BZ, Veeraraghavan H, Apte AP, Thakur SB, et al. Breast cancer subtype intertumor heterogeneity: MRI-based features predict results of a genomic assay. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2015;42(5):1398–406. doi: 10.1002/jmri.24890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parikh J, Selmi M, Charles-Edwards G, Glendenning J, Ganeshan B, Verma H, et al. Changes in Primary Breast Cancer Heterogeneity May Augment Midtreatment MR Imaging Assessment of Response to Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy. Radiology. 2014;272(1):100–12. doi: 10.1148/radiol.14130569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Win T, Miles KA, Janes SM, Ganeshan B, Shastry M, Endozo R, et al. Tumor Heterogeneity and Permeability as Measured on the CT Component of PET/CT Predict Survival in Patients with Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19(13):3591–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-12-1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu J, Gong G, Cui Y, Li R. Intratumor partitioning and texture analysis of dynamic contrast-enhanced (DCE)-MRI identifies relevant tumor subregions to predict pathological response of breast cancer to neoadjuvant chemotherapy. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2016 doi: 10.1002/jmri.25279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.King V, Brooks JD, Bernstein JL, Reiner AS, Pike MC, Morris EA. Background Parenchymal Enhancement at Breast MR Imaging and Breast Cancer Risk. Radiology. 2011;260(1):50–60. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11102156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dontchos BN, Rahbar H, Partridge SC, Korde LA, Lam DL, Scheel JR, et al. Are Qualitative Assessments of Background Parenchymal Enhancement, Amount of Fibroglandular Tissue on MR Images, and Mammographic Density Associated with Breast Cancer Risk? Radiology. 2015;276(2):371–80. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2015142304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van der Velden BHM, Dmitriev I, Loo CE, Pijnappel RM, Gilhuijs KGA. Association between Parenchymal Enhancement of the Contralateral Breast in Dynamic Contrast-enhanced MR Imaging and Outcome of Patients with Unilateral Invasive Breast Cancer. Radiology. 2015;276(3):675–85. doi: 10.1148/radiol.15142192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burnside ES, Drukker K, Li H, Bonaccio E, Zuley M, Ganott M, et al. Using computer-extracted image phenotypes from tumors on breast magnetic resonance imaging to predict breast cancer pathologic stage. Cancer. 2016;122(5):748–57. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li H, Zhu Y, Burnside ES, Drukker K, Hoadley KA, Fan C, et al. MR Imaging Radiomics Signatures for Predicting the Risk of Breast Cancer Recurrence as Given by Research Versions of MammaPrint, Oncotype DX, and PAM50 Gene Assays. Radiology. 2016:152110. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2016152110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Segal E, Sirlin CB, Ooi C, Adler AS, Gollub J, Chen X, et al. Decoding global gene expression programs in liver cancer by noninvasive imaging. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25(6):675–80. doi: 10.1038/nbt1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Diehn M, Nardini C, Wang DS, McGovern S, Jayaraman M, Liang Y, et al. Identification of noninvasive imaging surrogates for brain tumor gene-expression modules. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(13):5213–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801279105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gevaert O, Xu JJ, Hoang CD, Leung AN, Xu Y, Quon A, et al. Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: Identifying Prognostic Imaging Biomarkers by Leveraging Public Gene Expression Microarray Data-Methods and Preliminary Results. Radiology. 2012;264(2):387–96. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12111607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nair VS, Gevaert O, Davidzon G, Napel S, Graves EE, Hoang CD. Prognostic PET F-18-FDG Uptake Imaging Features Are Associated with Major Oncogenomic Alterations in Patients with Resected Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (vol 72, pg 3725, 2012) Cancer Res. 2012;72(18):4870–1. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-3161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yamamoto S, Han W, Kim Y, Du LT, Jamshidi N, Huang DS, et al. Breast Cancer: Radiogenomic Biomarker Reveals Associations among Dynamic Contrast-enhanced MR Imaging, Long Noncoding RNA, and Metastasis. Radiology. 2015;275(2):384–92. doi: 10.1148/radiol.15142698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhu Y, Li H, Guo W, Drukker K, Lan L, Giger ML, et al. Deciphering Genomic Underpinnings of Quantitative MRI-based Radiomic Phenotypes of Invasive Breast Carcinoma. Scientific reports. 2015:5. doi: 10.1038/srep17787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yamamoto S, Huang D, Du L, Korn RL, Jamshidi N, Burnette BL, et al. Radiogenomic Analysis Demonstrates Associations between 18F-Fluoro-2-Deoxyglucose PET, Prognosis, and Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition in Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer. Radiology. 2016:160259. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2016160259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yamamoto S, Maki DD, Korn RL, Kuo MD. Radiogenomic analysis of breast cancer using MRI: a preliminary study to define the landscape. Am J Roentgenol. 2012;199(3):654–63. doi: 10.2214/AJR.11.7824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen W, Giger ML, Bick U. A Fuzzy C-Means (FCM)-Based Approach for Computerized Segmentation of Breast Lesions in Dynamic Contrast-Enhanced MR Images 1. Academic radiology. 2006;13(1):63–72. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2005.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tustison NJ, Avants BB, Cook PA, Zheng Y, Egan A, Yushkevich PA, et al. N4ITK: improved N3 bias correction. IEEE transactions on medical imaging. 2010;29(6):1310–20. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2010.2046908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Monti S, Tamayo P, Mesirov J, Golub T. Consensus clustering: a resampling-based method for class discovery and visualization of gene expression microarray data. Machine learning. 2003;52(1–2):91–118. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reynolds AP, Richards G, de la Iglesia B, Rayward-Smith VJ. Clustering rules: a comparison of partitioning and hierarchical clustering algorithms. Journal of Mathematical Modelling and Algorithms. 2006;5(4):475–504. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tusher VG, Tibshirani R, Chu G. Significance analysis of microarrays applied to the ionizing radiation response. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2001;98(9):5116–21. doi: 10.1073/pnas.091062498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kapp AV, Tibshirani R. Are clusters found in one dataset present in another dataset? Biostatistics. 2007;8(1):9–31. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxj029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wilcox RR. Adjusting for unequal variances when comparing means in one-way and two-way fixed effects ANOVA models. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 1989;14(3):269–78. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tibshirani R, Hastie T, Narasimhan B, Chu G. Diagnosis of multiple cancer types by shrunken centroids of gene expression. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2002;99(10):6567–72. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082099299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu H, Lafferty J, Wasserman L. The nonparanormal: Semiparametric estimation of high dimensional undirected graphs. Journal of Machine Learning Research. 2009;10(Oct):2295–328. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vaske CJ, Benz SC, Sanborn JZ, Earl D, Szeto C, Zhu J, et al. Inference of patient-specific pathway activities from multi-dimensional cancer genomics data using PARADIGM. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(12):i237–i45. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. cell. 2011;144(5):646–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Foekens JA, Romain S, Look MP, Martin P-M, Klijn JG. Thymidine kinase and thymidylate synthase in advanced breast cancer: response to tamoxifen and chemotherapy. Cancer Res. 2001;61(4):1421–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Longley DB, Harkin DP, Johnston PG. 5-fluorouracil: mechanisms of action and clinical strategies. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2003;3(5):330–8. doi: 10.1038/nrc1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.André F, Michiels S, Dessen P, Scott V, Suciu V, Uzan C, et al. Exonic expression profiling of breast cancer and benign lesions: a retrospective analysis. The lancet oncology. 2009;10(4):381–90. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70024-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Barbera-Guillem E, Nyhus JK, Wolford CC, Friece CR, Sampsel JW. Vascular endothelial growth factor secretion by tumor-infiltrating macrophages essentially supports tumor angiogenesis, and IgG immune complexes potentiate the process. Cancer Res. 2002;62(23):7042–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang M, Kaufman RJ. The impact of the endoplasmic reticulum protein-folding environment on cancer development. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2014;14(9):581–97. doi: 10.1038/nrc3800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Baselga J, Campone M, Piccart M, Burris HA, III, Rugo HS, Sahmoud T, et al. Everolimus in postmenopausal hormone-receptor–positive advanced breast cancer. New Engl J Med. 2012;366(6):520–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1109653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bachelot T, Bourgier C, Cropet C, Ray-Coquard I, Ferrero J-M, Freyer G, et al. Randomized phase II trial of everolimus in combination with tamoxifen in patients with hormone receptor–positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2–negative metastatic breast cancer with prior exposure to aromatase inhibitors: A GINECO study. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(22):2718–24. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.0708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gherardi E, Birchmeier W, Birchmeier C, Woude GV. Targeting MET in cancer: rationale and progress. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12(2):89–103. doi: 10.1038/nrc3205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Martelotto LG, Ng CK, Piscuoglio S, Weigelt B, Reis-Filho JS. Breast cancer intra-tumor heterogeneity. Breast Cancer Research. 2014;16(3):1. doi: 10.1186/bcr3658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shipitsin M, Campbell LL, Argani P, Weremowicz S, Bloushtain-Qimron N, Yao J, et al. Molecular definition of breast tumor heterogeneity. Cancer cell. 2007;11(3):259–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Itakura H, Achrol AS, Mitchell LA, Loya JJ, Liu T, Westbroek EM, et al. Magnetic resonance image features identify glioblastoma phenotypic subtypes with distinct molecular pathway activities. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7(303):303ra138. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa7582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.