Abstract

West Nile virus (WNV) can cause severe human neurological diseases including encephalitis and meningitis. The mechanisms by which WNV enters the central nervous system (CNS) and host-factors that are involved in WNV neuroinvasion are not completely understood. The proinflammatory chemokine osteopontin (OPN) is induced in multiple neuroinflammatory diseases and is responsible for leukocyte recruitment to sites of its expression. In this study, we found that WNV infection induced OPN expression in both human and mouse cells. Interestingly, WNV-infected OPN deficient (Opn −/−) mice exhibited a higher survival rate (70%) than wild type (WT) control mice (30%), suggesting OPN plays a deleterious role in WNV infection. Despite comparable levels of viral load in circulating blood cells and peripheral organs in the two groups, WNV-infected polymorphonuclear neutrophil (PMN) infiltration and viral burden in brain of Opn −/− mice were significantly lower than in WT mice. Importantly, intracerebral administration of recombinant OPN into the brains of Opn −/− mice resulted in increased WNV-infected PMN infiltration and viral burden in the brain, which was coupled to increased mortality. The overall results suggest that OPN facilitates WNV neuroinvasion by recruiting WNV-infected PMNs into the brain.

Introduction

West Nile virus (WNV) is a single-stranded RNA virus belonging to the flaviviridae family that is primarily transmitted to humans by infected mosquitos1, 2. Although the majority of WNV-infected individuals remain asymptomatic, some develop symptoms ranging from mild fever and maculopapular rash to severe neuroinvasive diseases, including flaccid paralysis, encephalitis, meningitis, and possible death. The pathogenesis of neuroinvasive WNV is still not well understood and there is no vaccine or specific antiviral therapeutic available for human use.

Osteopontin (OPN) is a multifunctional protein also known as early T-lymphocyte activation-1 (ETA-1) and secreted phosphoprotein-1 (SPP-1)3, 4. OPN is produced by a variety of immune cells, including mast cells, dendritic cells, macrophages, neutrophils, B lymphocytes and T lymphocytes5, 6. There are two primary protein isoforms of OPN, intracellular (iOPN) and secreted (sOPN) OPN, each having a distinct function in the context of immunity. For instance, iOPN is involved in amplification of the type I interferon (IFN) response following Toll-like receptor (TLR) engagement7, 8, whereas sOPN can recruit leukocytes to sites of its expression9, 10. OPN has a wide range of biological functions, such as biomineralization and bone remodeling3, but it is also involved in the pathogenesis of many neuroinflammatory diseases, including multiple sclerosis11, Parkinson’s disease12, Alzheimer’s disease13 and in cancer cell metastases and brain tumor formation14. OPN expression is also induced by various viral infections, including human immunodeficiency virus15, hepatitis C virus16 and Zika virus infection in human neural progenitor cells17. However, the role of OPN during WNV pathogenesis is not known.

Polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMN) constitute approximately 50–70% of the total human leukocyte population and are the first immune cells recruited to sites of infection18, 19. PMNs are crucial players in controlling bacterial and fungal infections through phagocytosis, degranulation and neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs)18. We have previously shown that PMNs were permissive to WNV infection and harbored 75% of WNV in the total leukocyte population of mice20, thus it is possible that WNV-infected PMNs play an important role in transporting the virus into the central nervous system (CNS), contributing to neuroinvasive disease. In line with this, human WNV cases with neurological disease have increased neutrophils in their cerebral spinal fluid (CSF), indicating a possible role for PMNs in the development of the neurological symptoms of WNV infection21, 22. In this study, we show that sOPN promotes WNV-infected PMN recruitment into the CNS, enhancing disease severity.

Results

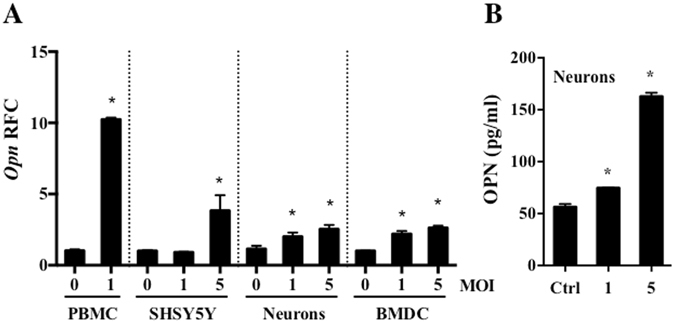

WNV infection induces OPN expression in both human and mouse cells

OPN is induced in various human neuroinflammatory diseases3, 11–14, 17. Here, we found that OPN was also induced in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) isolated from healthy human volunteers without a history of WNV infection, following WNV infection in vitro (Fig. 1A). In addition, Opn expression was increased in WNV-infected mouse bone marrow derived dendritic cells (BMDCs, Fig. 1A). Since WNV is a neurotropic virus23 and sOPN is involved in the recruitment of immune cells3, we determined if WNV-infected neurons express OPN. For this, human neuroblastoma cells (SH-SY5Y) and murine primary neurons were infected with WNV and Opn gene expression was measured by qPCR, and sOPN production in the medium of primary neurons was measured by ELISA. The results showed that the expression of Opn was induced in both human and murine neuronal cells (Fig. 1A and B). In summary, these results demonstrated that WNV infection induced OPN expression in both human and mouse cells.

Figure 1.

Osteopontin (OPN) is induced following WNV infection in human and mouse cells. (A) PBMCs isolated from healthy human volunteers (1 × 105 cells/ml, n = 4) were infected with WNV (MOI = 1) for 24 hr, human neuroblastoma cells (1 × 106 cells/ml, SHSY5Y, n = 3), primary mouse neurons (1 × 104 cells/ml, neurons, n = 3) and mouse bone marrow derived dendritic cells (3 × 105 cells/ml, BMDCs, n = 3) were infected with WNV at MOI of 1 or 5 for 24 hr, and the relative fold change (RFC) of Opn expression was measured by qPCR, and (B) OPN production in the cell medium of primary mouse neurons was measured by ELISA (n = 3). All experiments were performed twice and analyzed using a two-tailed, Student’s t-test (*denotes p < 0.05).

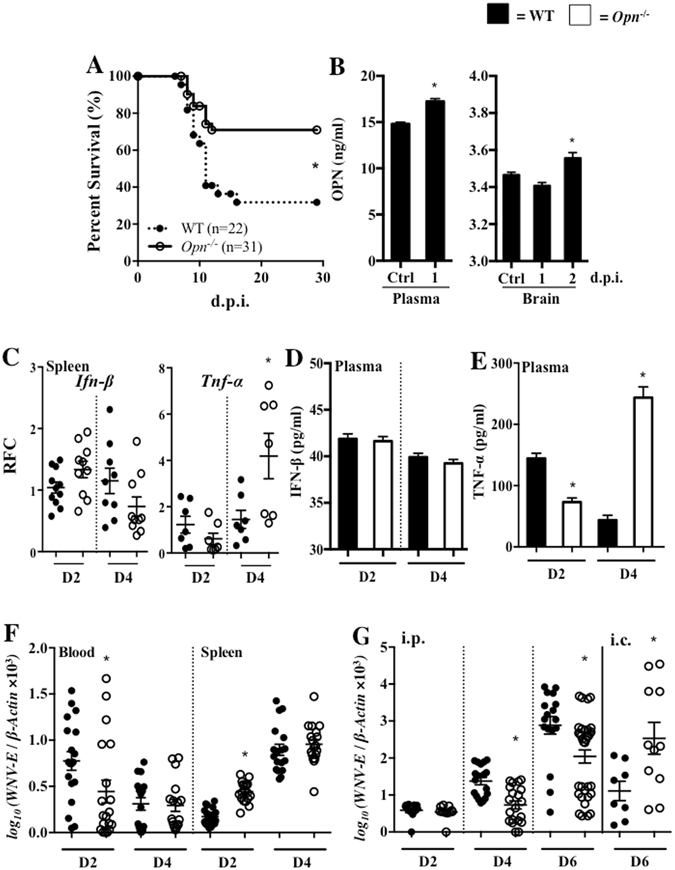

OPN facilitates WNV infection in mice

To determine the putative role of OPN in the pathogenesis of WNV in vivo, we intraperitoneally (i.p.) infected wild type (WT) and OPN deficient (Opn −/−) mice with WNV (2,000 PFU). The survival results showed that approximately 70% of Opn −/− mice and 30% of WT control mice survived WNV infection, suggesting a detrimental role for OPN during WNV infection (Fig. 2A). To further relate the role of OPN to viral burden, we measured OPN levels and viral burden in mice blood, plasma, spleens and brain tissues at various time points post-infection (p.i.). Consistent with the in vitro results in Fig. 1A and B, OPN levels were increased in WT mouse plasma at day 1 p.i., and in whole brain homogenates at day 2 p.i. (Fig. 2B). Since OPN has been suggested to regulate type I interferon production7, 8 and TNF-α has been implicated in blood brain barrier (BBB) compromise24, we measured the expression of Ifn-β and Tnf-α in spleens by qPCR. The results showed Ifn-β mRNA level was not significantly altered between WT and Opn −/− mice at D2 and D4 p.i., but Tnf-α mRNAs were marginally increased at D4 p.i. (Fig. 2C). Since these molecules circulate in blood and can interact at the BBB interface, we also measured the levels of IFN-β and TNF-α in plasma isolated from WNV-infected WT and Opn −/− mice. Although no significant difference was observed in the levels of IFN-β, interestingly TNF-α displayed a biphasic response in expression, whereby TNF-α levels were reduced at day 2 p.i. and increased at day 4 p.i. (Fig. 2D and E). WNV-envelope (WNV-E) RNA in blood and spleens were comparable between WT and Opn −/− mice at D4 p.i. (Fig. 2F). In contrast, viral RNA in the brain tissues of Opn −/− mice was significantly lower than WT mice at D4 and D6 p.i., while WNV-E RNA was marginally detected in brain tissues at D2 p.i. with no significant difference between the two groups (Fig. 2G). Viral RNA burden in the brain agreed with the survival results (Fig. 2A), suggesting that OPN may contribute to WNV disease by enhancing infection in the brain. Thus, resistance of Opn −/− mice to WNV infection could be due to two possible mechanisms: either Opn −/− mice brain tissue may be resistant to WNV infection, or fewer viruses invade Opn −/− mice brain parenchyma. To determine if brain-intrinsic antiviral factors were involved in Opn −/− mice, we injected 20 PFU of WNV into the brains of Opn −/− and WT control mice via an intracerebral (i.c) inoculation route, and measured viral RNA in brain tissue on D6 p.i. (Fig. 2G). The results showed there was slightly more viral RNA in the brains of Opn −/− mice than WT controls, excluding the possibility that brain tissue of Opn −/− mice might be intrinsically resistant to WNV replication. In contrast, these results suggest that OPN may facilitate WNV brain invasion.

Figure 2.

Opn −/− mice infected with WNV have increased survival and reduced viral burden in brain. (A) WT and Opn −/− mice were infected with 2,000 PFU of WNV (i.p.) and survival was monitored for 30 days. (B) Plasma (left) was collected from WT mice (n = 3) before infection (Ctrl) and on 1 day post infection (d.p.i.) and whole brain homogenates (right) were prepared on 1 and 2 d.p.i. to measure OPN by an ELISA. (C) RFC expression of Ifn-β and Tnf-α in spleens were measured by qPCR (n = 7–11) normalized to β-actin. (D and E) Plasma collected from WT and Opn −/− mice on days 2 (D2) and 4 (D4) p.i. to measure the levels of IFN-β and TNF-α by an ELISA (n = 3). WNV-E were quantified in blood (n = 16–21) and spleens (n = 18–22) (F), and (G) brains (n = 10–36) at selected time points (p.i.), and in WT (n = 8) and Opn −/− mice (n = 11) brains that were intracerebrally (i.c.) infected with 20 PFU of WNV on day 6 (D6) p.i. The survival data were analyzed using a Kaplan-Meier log-rank test. All remaining experiments were performed twice and analyzed using a two-tailed, Student’s t-test (*denotes p < 0.05).

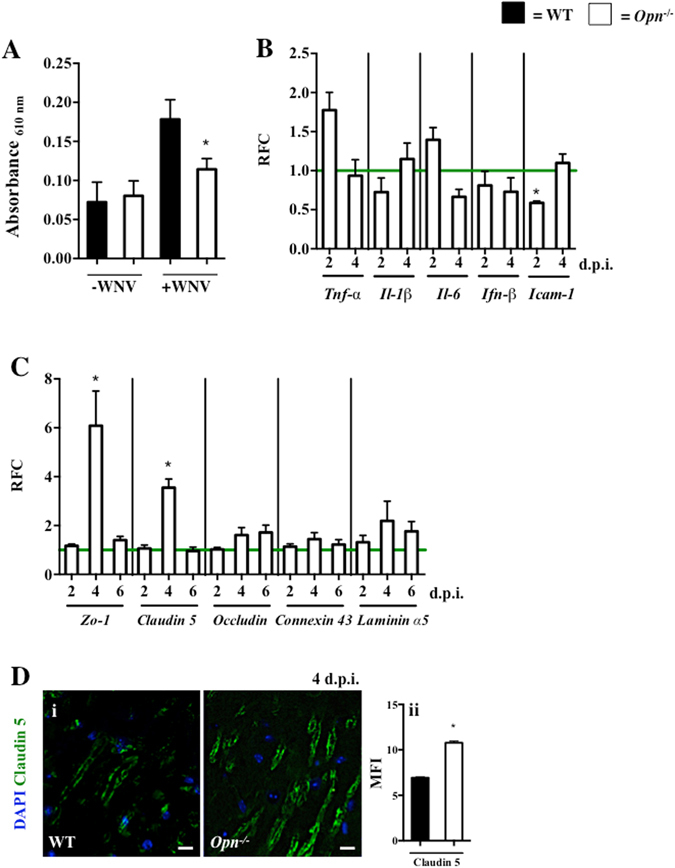

Opn−/− mice have a tighter BBB following WNV infection

The BBB is an important physiological barrier for protecting the brain against various insults, including WNV and other neuroinvasive pathogens23, 25. We next sought to determine if the BBB is tighter in Opn −/− mice than WT mice without or with WNV infection with an Evans blue assay. Similar levels of Evans blue dye was observed in brain tissues from uninfected Opn −/− and WT controls, which suggests that OPN does not contribute to BBB compromise. However, following WNV infection, Opn −/− mice had reduced Evans blue dye brain tissue integration as compared to WT controls (Fig. 3A), suggesting Opn −/− mice have a tighter BBB following infection. To determine if there were any changes in inflammatory or antiviral responses between WT and Opn −/− brain tissues, we used qPCR to measure the expression of Tnf-α, Il-1β, Il-6 and Ifn-β with the results indicating no significant difference in the expression of these genes (Fig. 3B). Interestingly, the gene expression of an endothelial cell marker involved in leukocyte extravasation, intracellular adhesion molecule-1 (Icam-1), was significantly reduced in the brain tissues of Opn −/− mice at 2 d.p.i., suggesting defective leukocyte extravasation into the brain of Opn −/− mice at the early stage of infection (Fig. 3B). In addition, we also evaluated mRNA expression of BBB tight junction related genes Zo-1, Claudin 5, Occludin, Connexin 43 and Laminin α5 and found Zo-1 and Claudin 5 were significantly higher in brain tissues of Opn −/− mice on D4 p.i., with a trend in higher expression of Occludin, Connexin 43 and Laminin α5 (Fig. 3C). We also confirmed the expression of Claudin 5 at the protein level by immunofluorescence of whole brain tissue sections, which showed increased mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) of Claudin 5 localized to blood vessels that innervated cortical brain parenchyma in Opn −/− mice compared to WT controls (Fig. 3D). Collectively, these results indicated that Opn −/− mice have a tighter BBB than WT control mice following WNV infection.

Figure 3.

Opn −/− mice have tighter blood brain barriers following WNV infection. WT (n = 21) and Opn −/− (n = 27) mice were infected with WNV (2,000 PFU i.p.) and uninfected WT (n = 12) and Opn −/− (n = 15) mice (PBS i.p., 100 μl) mice were used as absorbance controls. (A) Brain infiltrated Evans blue dye was measured with a spectrophotometer on day 4 p.i. (B) RFC of Tnf-α, Il-1β, Il-6, Ifn-β and Icam-1 normalized to β-Actin in brains of Opn −/− mice compared to WT controls (horizontal green line) on 2 and 4 d.p.i (n = 4–12). (C) RFC of Opn −/− whole brains were analyzed for the expression of tight junction genes Zo-1, Claudin 5, Occludin, Connexin 43 and Laminin α5 normalized to β-actin and compared to WT controls (horizontal green line) on 2, 4, and 6 d.p.i (n = 4–12). (D) (i) Immunofluorescence of Claudin 5 (green) and DAPI (blue) in cortical brain sections of WT and Opn −/− mice at 4 d.p.i. following WNV (2,000 PFU) infection, and (ii) mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) of Claudin 5. All experiments were performed twice and analyzed using a two-tailed, Student’s t-test (*denotes p < 0.05). Scale bar = 10 μm.

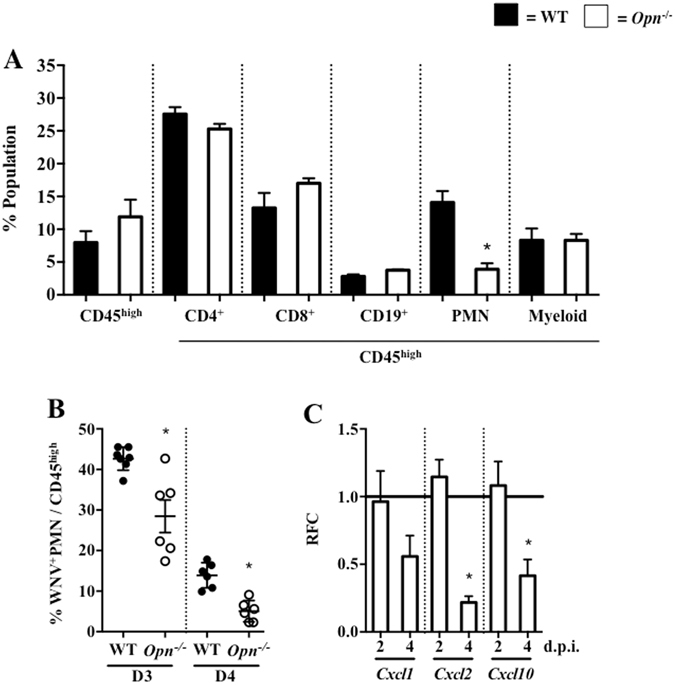

Opn−/− mice have less PMN-brain infiltration following WNV infection

To further investigate the contributing role of OPN during WNV-mediated BBB permeability, we examined immune cell infiltration and WNV-E antigens in the brains of Opn −/− and WT control mice by flow cytometry. The results showed that among all the measured brain-infiltrating leukocytes, PMNs were the predominant cell type that were reduced (approximately 70%) in Opn −/− mice compared to WT mice (Fig. 4A and Supplemental Fig. 1). To further determine if OPN recruits PMNs carrying WNV into the brain, we infected WT and Opn −/− mice with WNV (2,000 PFU, i.p.) and isolated their brains on D3 and D4 p.i. for flow cytometric analysis. We found that the percentages of WNV-infected PMNs were reduced in the brains of Opn −/− mice during the early infection course compared to WT controls (Fig. 4B). Since chemokines are responsible for PMN recruitment26, we measured expression of chemokines in brain tissues of WT and Opn −/− mice. We found that PMN chemoattractant genes Cxcl2 and another chemokine Cxcl10, had significantly reduced expression in Opn −/− mice compared to WT controls at 4 d.p.i. (Fig. 4C), which may be attributed to milder viral infection in the brain. In summary, these results suggest that PMN infiltration is reduced in the brains of Opn −/− mice, which may be in part due to reduced PMN chemoattractant gene expression.

Figure 4.

Opn −/− mice have reduced PMN-brain infiltration following WNV infection. WT and Opn −/− mice were infected with 2,000 PFU (i.p.). (A) Brain infiltrating leukocytes were quantified by flow cytometry on day 4 p.i., including total infiltrating leukocytes (CD45high), CD4+ cells (CD4+/CD45high), CD8+ cells (CD8+/CD45high), CD19+ cells (CD19+/CD45high), PMNs (Ly6G+CD11b+/CD45high) and myeloid cells (Ly6G-CD11b+/CD45high); n = 5–7 per group. (B) Brain-infiltrating WNV+ PMN (% WNV+Ly6G+/CD45high) were quantified on days 3 (D3) and 4 (D4) p.i. (n = 5–7). Brains were collected (2 and 4 d.p.i.), subjected to qPCR and the RFC of Opn −/− compared to WT controls (horizontal black line, n = 6–12) for Cxcl1, Cxcl2 and Cxcl10 were normalized to β-actin. Experiments were performed at least twice and analyzed using a two-tailed, Student’s t-test (*denotes p < 0.05).

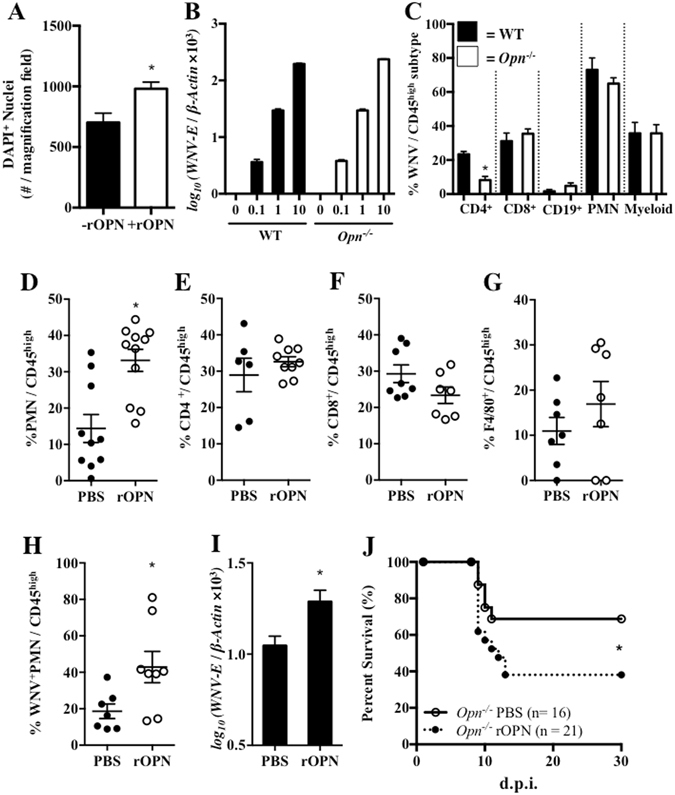

sOPN recruits WNV-infected PMNs into the brain enhancing disease severity

OPN has been shown to recruit PMNs in vitro 9. In our study, we confirmed that recombinant OPN (rOPN) could attract PMNs in a transwell migration assay (Fig. 5A), suggesting that along with reduced expression of Cxcl2, reduced PMN infiltration in brains of Opn −/− mice may also be due to lack of sOPN. In addition, we confirmed that deficiency of OPN did not alter PMN permissiveness to WNV infection by qPCR (Fig. 5B). We have previously demonstrated that PMNs were very permissive to WNV infection20, 27. In agreement with these reports, here we also identified PMNs as the primary carriers of WNV during neuroinvasive infection in mice, as approximately 75% of total infiltrated PMNs were WNV+ within both WT and Opn −/− mice (Fig. 5C). Therefore, it is possible that sOPN might recruit WNV-infected PMNs into brain, enhancing WNV neuroinvasion. To test this hypothesis in vivo, we injected rOPN (50 ng, i.c.) or an equal volume of PBS into the brains of Opn −/− mice and 1 hr later infected them with WNV (2,000 PFU, i.p.). Mice were euthanized and brains were isolated on D4 p.i., a time point when the BBB was largely compromised as indicated by the Evans blue assay (Fig. 3A) and total brain infiltrated leukocytes were quantified by flow cytometry. We found that infiltrated PMNs were considerably increased following rOPN supplement in Opn −/− mice brains, while the infiltration of CD4+ cells, CD8+ cells, and macrophages were not significantly altered (Fig. 5D–G), suggesting that rOPN can selectively recruit PMNs into brain following WNV infection. In complement with this, rOPN-supplemented Opn −/− mice had increased percentage of WNV-infected PMN infiltration into their brains (Fig. 5H) and WNV burden was significantly higher in brains of rOPN-supplemented Opn −/− mice (Fig. 5I), which resulted in dramatically reduced survival of rOPN-supplemented Opn −/− mice compared to PBS-supplemented Opn −/− mice (Fig. 5J). Collectively, our results suggested that sOPN could recruit WNV-infected PMNs into the brain, facilitating WNV neuroinvasive disease.

Figure 5.

Recombinant OPN recruits PMNs in vitro and in vivo and increases WNV infection in Opn −/− mice. (A) Transwell migration assay using bone marrow derived PMNs isolated from WT mice (n = 3) and recombinant mouse OPN (rOPN, 2 μg/ml). (B) Bone-marrow derived PMNs isolated from WT and Opn −/− mice (n = 4) were infected in vitro with WNV for 24 hr, followed by qPCR analysis to measure WNV-E relative to β-Actin. (C) WT and Opn −/− mice were infected with WNV (2,000 PFU) and the percentage (%) of WNV+ expressing brain infiltrating leukocytes were profiled for total populations of CD4+ cells (CD4+/CD45high), CD8+ cells (CD8+/CD45high), CD19+ cells (CD19+/CD45high), PMNs (CD11b+Ly6G+/CD45high) and myeloid cells (CD11b+Ly6G−/CD45high); n = 5–7 per group. Opn −/− mice were pretreated with rOPN (50 ng, i.c.) or a PBS-vehicle control and 1 hr later were infected with WNV (2,000 PFU, i.p.). Brain-infiltrating leukocytes (n = 6–11) were quantified by flow cytometry on day 4 p.i.; (D) PMNs (Ly6G+CD11b+/CD45high), (E) CD4+ cells (CD4+/CD45high), (F) CD8+ cells (CD8+/CD45high), and (G) macrophages (F4/80+/CD45high). Brains were collected on day 4 p.i. for flow cytometric analysis and qPCR measurement of WNV. (H) Percent (%) population of WNV+PMNs (WNV+Ly6G+) in total infiltrating leukocytes (CD45high) by flow cytometric analysis (n = 7–8). (I) WNV-E relative to β-Actin was analyzed by qPCR in brains of Opn −/− mice with PBS (n = 6) or rOPN (n = 7) i.c. supplement. (J) Survival of Opn −/− mice either pretreated i.c. with rOPN (n = 21) or PBS (n = 16) for 1 hr, followed by infection with 2,000 PFU of WNV (i.p.). The survival data were analyzed using a Kaplan-Meier log-rank test. All remaining experiments were performed twice and analyzed using a two-tailed, Student’s t-test (*denotes p < 0.05).

Discussion

Understanding the mechanisms by which WNV invades the CNS is a prerequisite for developing specific antiviral therapeutics to combat WNV neuroinvasive disease and associated long-term sequelae1, 2. In theory, WNV can enter the brain through multiple routes, including diffusion through endothelial tight junctions, direct infection of endothelial cells, infected leukocytes that ‘Trojan horse’ WNV into the CNS, infection of olfactory neurons, and/or direct axonal retrograde transport from infected peripheral neurons23, 28–31. Infected T cells and macrophages have been suggested as ‘Trojan horse’ WNV carriers into the CNS29, 32, 33, while our previous report demonstrated that WNV replicates more efficiently in human and mouse PMNs20. In addition, both clinical and experimental mouse data show that PMNs are the predominant infiltrating leukocyte subpopulation in the CNS during the early-stage of WNV infection22, 34, 35. Therefore, it is possible that a small number of viral particles enter the brain and infect neuronal cells and immune cells to produce chemoattractant molecules that could trigger an influx of WNV-infected PMNs into the brain, paradoxically making infection more severe. Understanding the host factors necessary for the regulation of PMN recruitment into the CNS and whether infiltrating PMNs carry WNV into the CNS becomes essential to elucidate the contribution of PMNs in WNV neuroinvasion.

In this study, we found that the expression of OPN was induced following WNV infection in human and mouse neuronal cells in vitro. In line with this, neurons have been described to be major producers of OPN in HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders36, while other CNS-resident cells including astrocytes37 and microglia38 induce OPN expression following glioma-associated activation, suggesting OPN may be involved in the pathogenesis of other neurodiseases. Here, we revealed a novel role for OPN in enhancing WNV neuroinvasion in mice, as shown by reduced viral burden in the brain and increased survival of WNV-infected Opn −/− mice compared to WT controls. Consistent with the previously reported role of sOPN in PMN recruitment9, we found that PMN infiltration was significantly reduced in the brains of Opn −/− mice compared to WT mice. By using a transwell migration assay and supplementing rOPN into the brains of Opn −/− mice, we further confirmed that OPN could recruit WNV-infected PMNs into the brain, resulting in a higher viral burden and reduced survival. Therefore, we concluded that OPN facilitates WNV neuroinvasive infection through the recruitment of WNV-infected PMNs.

Reduced leukocyte infiltration in particular with WNV-infected PMNs in the brains of Opn −/− mice following WNV infection, was negatively correlated with viral burden in brain tissue during an early stage of infection (D4 p.i.). Although antiviral functions of PMNs, such as NETs and reactive oxygen species (ROS) production were not studied in this report, PMNs isolated from WT and Opn −/− mice were both susceptible to equal viral loads and had similar capacity to transport WNV into the brain, which rules out defective immunity in Opn −/− PMNs. Our results confirmed that WNV induced OPN expression in neuronal cells, which indicates sOPN produced by WNV-infected neurons could play an important role in recruiting WNV-infected PMNs into the brain tissue following initial WNV brain entry. In support of this, i.c. rOPN supplement significantly increased WNV-infected PMN infiltration into the brains of Opn −/− mice compared to i.c. PBS supplemented controls. In addition, the expression of the PMN-attracting chemokine Cxcl2 was also diminished in the brains of WNV-infected Opn −/− mice, suggesting OPN may not be the sole factor responsible for reduced PMN infiltration in Opn −/− mice following WNV infection.

Although PMNs are necessary to combat WNV infection during a later time point of neuroinvasive WNV infection20, viral load was substantially reduced in Opn −/− mice early during infection (D4), which may be due to reduced PMN brain influx, contributing to enhanced survival. Indeed, the BBB was tighter in Opn −/− than WT mice following WNV infection, possibly due to the reduced influx of leukocytes and neuroinflammation, as robust immune cell infiltration could also interrupt the integrity of the BBB25, 39, 40. Furthermore, OPN did not appear to contribute to BBB compromise directly in our mouse model, while Opn −/− mice had reduced gene expression of Icam-1 and TNF-α levels early in the course of infection (D2 p.i.). ICAM-1 has been shown to regulate the integrity of the BBB in the mouse model of WNV infection41, which suggests other pathways that affect the integrity of the BBB may be also inhibited in Opn −/− mice directly or indirectly following infection. In addition, other than contributing to BBB compromise24, TNF-α has also been shown to be involved in the promotion of WNV clearance42 and to protect against WNV-induced neuronal apoptosis43, indicating multiple functions of TNF-α in the immune response that can support or inhibit viral-induced neurodisease, which requires further studies.

In conclusion, our results show that reduced PMN infiltration into the brain partially limits WNV neuroinvasion, suggesting OPN might serve as a potential therapeutic target to reduce WNV neuroinvasion.

Methods

Ethics statement and biosafety

Written informed consent was obtained from all human volunteers prior to their inclusion in this study. The protocol for human subject has been approved by the University of Southern Mississippi (USM) Institutional Review Board. All animal experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at USM. All in vitro experiments and animal studies involving live WNV were performed by certified personnel in biosafety level 3 (BSL3) laboratories following standard biosafety protocols approved by the USM Institutional Biosafety Committee.

Viruses and cell culture

WNV isolate (CT2741), kindly provided by John F. Anderson, was propagated one time in Vero cells (ATCC CCL-81) and titered by a Vero cell plaque assay44. Vero (ATCC CCL-131) were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) containing 1% L-glutamine (L-glu), 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Pen/Strep), and 10% FBS. SHSY5Y cells (ATCC CRL-2266) were maintained in Eagle’s minimal essential medium (EMEM) and F12 medium (1:1) containing 10% FBS. Mouse BMDCs were cultured in DMEM containing 10% FBS, 2% plasmacytoma cell medium containing GM-CSF (J588L), 1% Pen/Strep, 1% L-glu and 50 μM of β-mercaptoethanol. Mouse primary neurons were cultured in DMEM:F12 (1:1) medium containing 1% Pen/Strep, 10% FBS, 1% L-glu, and glucose (4.5 g/l) and Neurobasal®-A media (Life Technologies) containing 2% B-27, 10% FBS, 1% L-glu and 1% Pen/Strep. Polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs) were cultured in RPMI-1640.

Human peripheral blood mononuclear cells were isolated using Ficoll-Paque PLUS (GE Healthcare Life Sciences)20. Murine BMDCs were isolated and cultured from femurs of WT or Opn −/− mice (3 to 6 month-old)45, primary neuronal cells were isolated from adult (6–12 month-old) mice, triturated in Papain (2 mg/ml) and cultured on poly-ornithine pre-treated plates46, 47, and PMNs were isolated and cultured48, following previously published procedures. Purity of isolated PMNs was measured by flow cytometry as gated CD45+CD11b+Ly6G+ populations.

Animal Studies

C57BL/6J wild-type (WT) and Opn −/− (C57BL/6J background) mice breeding pairs were purchased from The Jackson laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Mice were bred in a USM animal facility clean room. Seven to nine week-old, sex-matched WT and Opn −/− mice were inoculated intraperitoneally (i.p.) with 2,000 plaque-forming units (PFUs) of WNV in 100 µl of PBS containing 1% gelatin20. Infected mice were monitored daily for morbidity and mortality for 30 days. Blood samples were collected by retro-orbital bleeding on D1–4 p.i. for viremia and Opn measurement by qPCR and mice were randomly euthanized on D2, D4, and D6 p.i. to collect spleen and brain tissues for gene expression and flow cytometric analysis. For intracerebral (i.c.) injections of WNV (20 PFU/mouse in 20 µl 1% gelatin) and recombinant OPN (rOPN; 50 ng/mouse in 20 µl in PBS) were performed on 8-week old, sex-matched mice anesthetized with 30% isoflurane in isopropanol27. For rOPN studies, one-hour post rOPN supplement, mice were inoculated with 2,000 PFU of WNV per mouse (i.p.) and monitored for 30 days.

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) and Enzyme-linked Immunosorbant Assays

Mouse tissues and cells were collected for total RNA extraction with TRIreagent (Molecular Research Center, Inc.) and converted into the first strand cDNA using the iSCRIPTTM cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad). qPCR assays were performed using iTAQTM polymerase supermix for probe-based assays (Bio-Rad) or iQ™ SYBR® Green Supermix polymerase (Bio-Rad). WNV-envelope (WNV-E) gene and mouse cellular gene primers and probes sequences were adapted according to previous publications: Opn 49, 50, WNV-E 51, β-Actin 20, 52, Zo-1 53, Claudin 5 54, Occludin 55, Connexin 43 56, Ifnβ 57, Tnf-a 58, Il-1β 59, Il-6 60 and Icam-1 60,Cxcl1 61, Cxcl2 62, and Cxcl10 63. Primers were designed for murine Laminin α5, forward 5′-TGGCTCACAGATGGCTCCTA-3′, and reverse 5′-CACTTGGATCGCCTTGCTGG-3′. Analyses were performed using either the 2−ΔΔCT method, normalized to β-Actin and represented as relative fold change (RFC) or the ratio of the absolute gene copy number of WNV-E to β-Actin. All primers and the WNV-E probe were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies or Applied Biosystems. Levels of OPN were quantified in murine plasma samples and culture media by using a mouse OPN ELISA kit (ENZO Life Sciences) following manufactures recommendations.

Evans Blue Assay

WT and Opn −/− mice were mock-infected with PBS or infected with 2,000 PFU of WNV (i.p.), and 800 µl of 2% Evans Blue dye (EBD) in PBS was injected (i.p.) on day 4 p.i. One hour after EBD injection, mice were transcardially perfused with ice-cold PBS. EBD in whole brain tissue was quantified using a spectrophotometer after DMSO homogenization (Bio-Rad Smart Spec 3000TM). All samples were normalized to control brains (with EBD, without WNV infection) for each genotype group (WT or Opn −/−).

Migration Assays

PMN migration assays were performed as previously described9, with additional modifications. Briefly, WT and Opn −/− PMNs in RPMI-1640 were added to the inserts of transwells (3 μm pore, Corning), while RPMI-1640 with or without rOPN (2 μg/ml, R&D Systems) was added to the bottom of each well. The cells were incubated for 8 hr in a 37 °C, 5% CO2 incubator. Migrated PMNs were quantified by counting the number of DAPI positive cells/magnification field that were 4% PFA fixed in the transwell interface using a confocal LSM 510 microscope (Zeiss) at 10× magnification.

Immunofluorescence assay

Mouse brains isolated after ice-cold PBS perfusion were 4% PFA fixed overnight, dehydrated, and paraffin-embedded for sectioning. Midsagittal sections (10 µm) were cut (American Optical Spencer 820 Microtome) and mounted. For immunostaining, sections were dried for 2 hr at 45 °C and rehydrated for 5 minutes in 100%, 95%, and 70% ethanol solutions followed by antigen retrieval by boiling in 5% sodium citrate for 10 minutes (50% power) in a microwave. Sections were probed with anti-Claudin 5 conjugated to flourophore 488 antibody (Thermo Fisher), mounted with Vectashield® mounting medium for fluorescence with DAPI, and imaged under a confocal LSM 510 microscope (Zeiss) at 63× magnification. Mean fluorescent intensity was quantified using ImageJ software64.

Flow cytometry

Procedures for brain cell preparation followed our previous report51. Cells (1 × 106 cells/ml) were probed with antibodies against CD45, Ly6G, CD11b, CD4, CD19, CD8 and F4/80 and analyzed with a flow cytometer (LSRFortessa, BD Bioscience) using version 6.0 FACSDiva™ software (BD Biosciences). All cell surface antibodies were purchased from eBioscience. Anti-WNV-Envelope (E) primary antibody (Abcam) and FITC-conjugated anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody (eBioscience) were used for viral detection. Unstained and single color compensation controls were used in parallel.

Enzyme-linked Immunosorbent Assay

Levels of OPN, IFN-β and TNF-α were measured using ELISA kits purchased from ENZO Life Sciences or Thermo Fisher following manufactures recommendations.

Statistical analyses

All data were analyzed using a two-tailed Student’s t-test and survival curves were analyzed using a Kaplan-Meier analysis. All statistical analyses were done by using GraphPad Prism software (version 6.0), with p < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. John F. Anderson at the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station for providing us with the WNV isolate (CT2741) and Matthew de Cruz for technical help with the confocal microscope. The authors also thank the Mississippi INBRE (funded by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences P20 GM103476-11) for use of the research facility. This work was supported in part, by The University of Southern Mississippi Start-up fund, the Wilson Research Foundation in Jackson, MS and American Heart Association.

Author Contributions

F.B. and A.M.P. conceived the experiments; A.M.P. conducted the experiments; D.A., L.D., L.L., and E.A.T. assisted in experiments; F.B. and A.M.P. wrote the manuscript; A.A.L. and D.S. provided experimental materials. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at doi:10.1038/s41598-017-04839-7

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Colpitts TMC, Montgomery MJ, Fikrig RR, West Nile E. Virus: biology, transmission, and human infection. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2012;25:635–648. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00045-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lim SM, Koraka P, Osterhaus AD, Martina BE. West Nile virus: immunity and pathogenesis. Viruses. 2011;3:811–828. doi: 10.3390/v3060811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sodek JGB, McKee MD. Osteopontin. Critical reviews in oral biology and medicine: an official publication of the American Association of Oral Biologists. 2000;11:279–303. doi: 10.1177/10454411000110030101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kahles F, Findeisen HM, Bruemmer D. Osteopontin: A novel regulator at the cross roads of inflammation, obesity and diabetes. Mol Metab. 2014;3:384–393. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2014.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nagasaka A, et al. Osteopontin is produced by mast cells and affects IgE-mediated degranulation and migration of mast cells. European journal of immunology. 2008;38:489–499. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lund SA, Giachelli CM, Scatena M. The role of osteopontin in inflammatory processes. Journal of cell communication and signaling. 2009;3:311–322. doi: 10.1007/s12079-009-0068-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cao W, Liu YJ. Opn: key regulator of pDC interferon production. Nature immunology. 2006;7:441–443. doi: 10.1038/ni0506-441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhao K, et al. Intracellular osteopontin stabilizes TRAF3 to positively regulate innate antiviral response. Scientific reports. 2016;6:23771. doi: 10.1038/srep23771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koh A, et al. Role of osteopontin in neutrophil function. Immunology. 2007;122:466–475. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2007.02682.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kariya Y, et al. Increased cerebrospinal fluid osteopontin levels and its involvement in macrophage infiltration in neuromyelitis optica. BBA clinical. 2015;3:126–134. doi: 10.1016/j.bbacli.2015.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bornsen L, Khademi M, Olsson T, Sorensen PS, Sellebjerg F. Osteopontin concentrations are increased in cerebrospinal fluid during attacks of multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2011;17:32–42. doi: 10.1177/1352458510382247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maetzler W, et al. Osteopontin is elevated in Parkinson’s disease and its absence leads to reduced neurodegeneration in the MPTP model. Neurobiology of disease. 2007;25:473–482. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Comi C, et al. Osteopontin is increased in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with Alzheimer’s disease and its levels correlate with cognitive decline. Journal of Alzheimer’s disease: JAD. 2010;19:1143–1148. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Atai NA, et al. Osteopontin is up-regulated and associated with neutrophil and macrophage infiltration in glioblastoma. Immunology. 2011;132:39–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2010.03335.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown A, et al. Osteopontin enhances HIV replication and is increased in the brain and cerebrospinal fluid of HIV-infected individuals. Journal of neurovirology. 2011;17:382–392. doi: 10.1007/s13365-011-0035-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iqbal J, McRae S, Banaudha K, Mai T, Waris G. Mechanism of hepatitis C virus (HCV)-induced osteopontin and its role in epithelial to mesenchymal transition of hepatocytes. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2013;288:36994–37009. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.492314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 17.Hanners NW, et al. Western Zika Virus in Human Fetal Neural Progenitors Persists Long Term with Partial Cytopathic and Limited Immunogenic Effects. Cell reports. 2016;15:2315–2322. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.05.075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Drescher BBF. Neutrophil in viral infections, friend or foe? Virus Res. 2013;171:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2012.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kolaczkowska E, Kubes P. Neutrophil recruitment and function in health and inflammation. Nature reviews. Immunology. 2013;13:159–175. doi: 10.1038/nri3399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bai F, et al. A paradoxical role for neutrophils in the pathogenesis of West Nile virus. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2010;202:1804–1812. doi: 10.1086/657416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Crichlow R, Bailey J, Gardner C. Cerebrospinal fluid neutrophilic pleocytosis in hospitalized West Nile virus patients. The Journal of the American Board of Family Practice/American Board of Family Practice. 2004;17:470–472. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.17.6.470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tyler KL, Pape J, Goody RJ, Corkill M, Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK. CSF findings in 250 patients with serologically confirmed West Nile virus meningitis and encephalitis. Neurology. 2006;66:361–365. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000195890.70898.1f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Verma S, et al. West Nile virus infection modulates human brain microvascular endothelial cells tight junction proteins and cell adhesion molecules: Transmigration across the in vitro blood-brain barrier. Virology. 2009;385:425–433. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.11.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Franceschi C, Campisi J. Chronic inflammation (inflammaging) and its potential contribution to age-associated diseases. The journals of gerontology. Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences. 2014;69(Suppl 1):S4–9. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glu057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dahm, T. R. H., Schwerk, C., Schroten, H., Tenenbaum, T. Neuroinvasion and Inflammation in Viral Central Nervous System Infections. Mediators Inflamm. 8562805, doi:10.1155/2016/8562805 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Kobayashi Y. The role of chemokines in neutrophil biology. Front Biosci. 2008;13:2400–2407. doi: 10.2741/2853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang PBF, et al. IL-22 signaling contributes to West Nile encephalitis pathogenesis. PloS one. 2012;7:e44153. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Diamond MS, Klein RS. West Nile virus: crossing the blood-brain barrier. Nature medicine. 2004;10:1294–1295. doi: 10.1038/nm1204-1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Samuel MA, Diamond MS. Pathogenesis of West Nile Virus infection: a balance between virulence, innate and adaptive immunity, and viral evasion. Journal of virology. 2006;80:9349–9360. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01122-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Samuel MA, Wang H, Siddharthan V, Morrey JD, Diamond MS. Axonal transport mediates West Nile virus entry into the central nervous system and induces acute flaccid paralysis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:17140–17145. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705837104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Suen WW, Prow NA, Hall RA, Bielefeldt-Ohmann H. Mechanism of West Nile virus neuroinvasion: a critical appraisal. Viruses. 2014;6:2796–2825. doi: 10.3390/v6072796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang S, et al. Drak2 contributes to West Nile virus entry into the brain and lethal encephalitis. J Immunol. 2008;181:2084–2091. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.3.2084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cardosa MJ, Porterfield JS, Gordon S. Complement receptor mediates enhanced flavivirus replication in macrophages. The Journal of experimental medicine. 1983;158:258–263. doi: 10.1084/jem.158.1.258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rawal A, Gavin PJ, Sturgis CD. Cerebrospinal fluid cytology in seasonal epidemic West Nile virus meningo-encephalitis. Diagn Cytopathol. 2006;34:127–129. doi: 10.1002/dc.20410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brehin AC, et al. Dynamics of immune cell recruitment during West Nile encephalitis and identification of a new CD19+B220-BST-2+ leukocyte population. J Immunol. 2008;180:6760–6767. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.10.6760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Silva K, et al. Cortical neurons are a prominent source of the proinflammatory cytokine osteopontin in HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. Journal of neurovirology. 2015;21:174–185. doi: 10.1007/s13365-015-0317-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jang T, et al. Osteopontin expression in intratumoral astrocytes marks tumor progression in gliomas induced by prenatal exposure to N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea. Am J Pathol. 2006;168:1676–1685. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Szulzewsky F, et al. Glioma-associated microglia/macrophages display an expression profile different from M1 and M2 polarization and highly express Gpnmb and Spp1. PloS one. 2015;10:e0116644. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miller DW. Immunobiology of the blood-brain barrier. Journal of neurovirology. 1999;5:570–578. doi: 10.3109/13550289909021286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ransohoff RM, Kivisäkk P, Kidd G. Three or more routes for leukocyte migration into the central nervous system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:569–581. doi: 10.1038/nri1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dai J, Wang P, Bai F, Town T, Fikrig E. Icam-1 participates in the entry of west nile virus into the central nervous system. Journal of virology. 2008;82:4164–4168. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02621-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shrestha B, Zhang B, Purtha WE, Klein RS, Diamond MS. Tumor necrosis factor alpha protects against lethal West Nile virus infection by promoting trafficking of mononuclear leukocytes into the central nervous system. Journal of virology. 2008;82:8956–8964. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01118-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang B, Patel J, Croyle M, Diamond MS, Klein RS. TNF-alpha-dependent regulation of CXCR3 expression modulates neuronal survival during West Nile virus encephalitis. Journal of neuroimmunology. 2010;224:28–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Paul AM, et al. Delivery of antiviral small interfering RNA with gold nanoparticles inhibits dengue virus infection in vitro. The Journal of general virology. 2014;95:1712–1722. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.066084-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lutz MB, et al. An advanced culture method for generating large quantities of highly pure dendritic cells from mouse bone marrow. Journal of immunological methods. 1999;223:77–92. doi: 10.1016/S0022-1759(98)00204-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Paul, A. M. et al. TLR8 Couples SOCS-1 and Restrains TLR7-Mediated Antiviral Immunity, Exacerbating West Nile Virus Infection in Mice. J Immunol (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Eide L, McMurray CT. Culture of adult mouse neurons. BioTechniques. 2005;38:99–104. doi: 10.2144/05381RR02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Swamydas MLMS. Isolation, purification and labeling of mouse bone marrow neutrophils for functional studies and adoptive transfer experiments. J Vis Exp. 2013;10:e50586. doi: 10.3791/50586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wu Y, et al. Breast cancer metastasis suppressor 1 regulates hepatocellular carcinoma cell apoptosis via suppressing osteopontin expression. PloS one. 2012;7:e42976. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chapman JMPD, et al. Osteopontin is required for the early onset of high fat diet-induced insulin resistance in mice. PloS one. 2010;5:e13959. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Town T, et al. Toll-like receptor 7 mitigates lethal West Nile encephalitis via interleukin 23-dependent immune cell infiltration and homing. Immunity. 2009;30:242–253. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bai F, et al. Use of RNA interference to prevent lethal murine west nile virus infection. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2005;191:1148–1154. doi: 10.1086/428507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yu H, et al. Interleukin-8 Regulates Endothelial Permeability by Down-regulation of Tight Junction but not Dependent on Integrins Induced Focal Adhesions. Int J Bio Sci. 2013;9:966–979. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.6996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hamers AAJ, et al. Limited Role of Nuclear Receptor Nur77 in Escherichia coli-Induced Peritonitis. Infect Immun. 2014;82:253–264. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00721-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dalessandri, T., Crawford1, G., Hayes, M., Seoane, R. C., Strida, J. IL-13 from intraepithelial lymphocytes regulates tissue homeostasis and protects against carcinogenesis in the skin. Nat Commun. 7, doi:10.1038/ncomms12080 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 56.Migale R, et al. Specific Lipopolysaccharide Serotypes Induce Differential Maternal and Neonatal Inflammatory Responses in a Murine Model of Preterm Labor. Am J Pathol. 2015;185:2390–2401. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2015.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Daffis, S. S. M., Keller, B. C., Gale, M. Jr., Diamond, M. S. Cell-specific IRF-3 responses protect against West Nile virus infection by interferon-dependent and -independent mechanisms. PLos Pathog3 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 58.Sun JH, et al. Active immunisation targeting soluble murine tumour necrosis factor alpha is safe and effective in collagen-induced arthritis model treatment. Clinical and experimental rheumatology. 2016;34:242–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Alderson RF, Pearsall D, Lindsay RM, Wong V. Characterization of receptors for ciliary neurotrophic factor on rat hippocampal astrocytes. Brain research. 1999;818:236–251. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(98)01273-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.D’Angelo, W. et al. The Molecular Basis for the Lack of Inflammatory Responses in Mouse Embryonic Stem Cells and Their Differentiated Cells. J Immunol, doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1601068 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 61.Bellet MM, Zocchi L, Sassone-Corsi P. The RelB subunit of NFκB acts as a negative regulator of circadian gene expression. Cell Cycle. 2012;11:3304–3311. doi: 10.4161/cc.21669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liu H, et al. Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid 1 Gene Deficiency Ameliorates Hepatic Injury in a Mouse Model of Chronic Binge Alcohol-Induced Alcoholic Liver Disease. Am J Pathol. 2015;185:43–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2014.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gao D, et al. Cyclic GMP-AMP synthase is an innate immune sensor of HIV and other retroviruses. Science. 2013;341:903–906. doi: 10.1126/science.1240933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat Methods. 2012;9:671–675. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.