Abstract

Background and purpose

Patients developing postoperative acute kidney injury (AKI) are at risk of higher morbidity and mortality. In arthroplasty patients, many pre- and perioperative factors are associated with AKI but some of the risk factors are unclear. We report the incidence of postoperative AKI, the conditions associated with it, and survival rates in AKI patients.

Patients and methods

We obtained data from 20,575 consecutive hip or knee arthroplasties. Postoperative AKI, occurring within 7 days after the operation, was defined using the risk, injury, failure, loss, and end-stage (RIFLE) criteria. We analyzed independent risk factors for AKI using binary logistic regression. In addition, we reviewed the records of AKI patients and performed a survival analysis.

Results

The AKI incidence was 3.3 per 1,000 operations. We found preoperative estimated glomerular filtration rate, ASA classification, body mass index, and duration of operation to be independent risk factors for AKI. Infections, paralytic ileus, and cardiac causes were the predominant underlying conditions, whereas half of all AKI cases occurred without any clear underlying condition. Survival rates were lower in AKI patients.

Interpretation

Supporting earlier results, existing renal insufficiency and patient-related characteristics were found to be associated with an increased risk of postoperative AKI. Furthermore, duration of operation was identified as an independent risk factor. We suggest careful renal monitoring postoperatively for patients with these risk factors.

Acute kidney injury (AKI) affects 0.5–5.2% of joint replacement recipients and it is an independent risk factor for chronic renal impairment, increased morbidity, and death (Ympa et al. 2005, Jafari et al. 2010, Coca et al. 2012, Kimmel et al. 2014, Perregaard et al. 2016). AKI increases in-hospital mortality but the adverse effects of AKI can also occur late (Lafrance and Miller 2010).

The preoperative risk factors associated with postoperative AKI in arthroplasty patients include elevated body mass index (BMI), diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, liver disease, congestive heart failure, hypertension, and vascular diseases (Jafari et al. 2010, Weingarten et al. 2012, Bell et al. 2015). Also, age, preoperative kidney dysfunction, and the preoperative use of renin-angiotensin axis-blocking medication are associated with postoperative AKI in arthroplasty patients (Aveline et al. 2009, Kimmel et al. 2014, Nielson et al. 2014, Bell et al. 2015). Although the American Society of Anesthesiologists’ (ASA) physical status classification system has a connection with AKI in orthopedic patients (Bell et al. 2015), it is not associated with AKI in arthroplasty patients (Jafari et al. 2010, Kimmel et al. 2014).

Perioperative factors associated with AKI include general anesthesia and blood transfusions (Weingarten et al. 2012). Also, duration of operation has been reported to be longer in AKI patients, but not statistically significantly so (Jafari et al. 2010, Weingarten et al. 2012, and Kimmel et al. 2014). The effects of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and concomitant use of diuretics, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, and angiotensin receptor blockers in arthroplasty populations is unclear (Lee et al. 2007, Fournier et al. 2014). Aminoglycosides (such as gentamycin) that are used as intravenous antibiotic prophylaxis or in cement may trigger AKI because of their nephrotoxicity (Curtis et al. 2005, Patrick et al. 2006, Lau and Kumar 2013, Ross et al. 2013, Bell et al. 2014, Craxford et al. 2014, Johansson et al. 2016) but otherwise, there are no data on the conditions or underlying reasons that trigger postoperative AKI in arthroplasty patients.

We assessed the incidence and factors associated with AKI following hip and knee arthroplasty in a large Scandinavian cohort and report the specific conditions associated with AKI. We hypothesized that: (1) the Scandinavian population would have similar rates of AKI to those in other populations; and (2) the ASA classification system (as a measure of comorbidity) and duration of operation would show an association with AKI.

Patients and methods

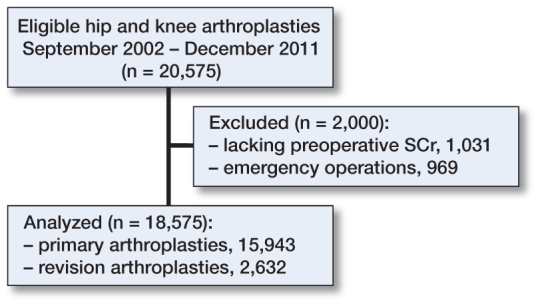

The study was performed in a large publicly funded orthopedic hospital specialized in joint replacement surgery, with an annual number of arthroplasties exceeding 3,000. The study population comprised patients with hip or knee arthroplasties performed at the hospital between September 2002 and December 2011 (n = 20,575). 2,000 patients were excluded from the study (Figure 1). The remaining 18,575 patients were used for the analyses. Demographic data and patient information were obtained from a prospective joint replacement database and patient administration database. The following data were collected for analysis: sex, age, indication for operation, BMI, ASA classification, anesthesia modality, prophylactic antibiotic, operated joint (hip or knee), duration of operation, fixation method (cemented, cementless, hybrid), laterality (unilateral or bilateral operation), type of operation (primary or revision), and use of antibiotic-impregnated bone cement (Tables 1 and 2).

Figure 1.

Exclusion of patients.

Table 1.

Association between preoperative factors and AKI; univariable regression results

| Descriptor | All patientsa | AKI | non-AKI | Incidence per 1,000 operations | OR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (range) | 69 (14–102) | 76 (41–88) | 69 (14–102) | 1.05 (1.02–1.08) | 0.001 | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 11,650 (63) | 33 | 11,617 | 2.8 | Reference | |

| Male | 6,925 (37) | 25 | 6,900 | 3.6 | 1.3 (0.76–2.1) | 0.4 |

| Body mass index | ||||||

| (missing, n = 1,719) median, (range) | 28.6 (14–59) | 31.6 (24–43) | 28.6 (14–59) | 1.1 (1.0–1.1) | 0.001 | |

| < 25 | 3,551 (21) | 6 | 3,545 | 1.7 | Reference | |

| 25–30 | 6,760 (40) | 14 | 6,746 | 2.1 | 1.2 (0.47–3.2) | 0.7 |

| 30–35 | 4,496 (27) | 14 | 4,482 | 3.1 | 1.9 (0.71–4.8) | 0.2 |

| > 35 | 2,049 (12) | 12 | 2,037 | 5.9 | 3.5 (1.3–9.3) | 0.01 |

| Joint | ||||||

| Hip | 8,821 (47) | 23 | 8,798 | 2.6 | Reference | |

| Knee | 9,754 (53) | 35 | 9,719 | 3.6 | 1.4 (0.8–2.3) | 0.2 |

| ASA classification (missing, n = 132) | ||||||

| 1 | 1,477 (8) | 0 | 1,477 | 0.0 | ||

| 2 | 8,427 (46) | 9 | 8,418 | 1.1 | Referenceb | < 0.001 |

| 3 | 8,046 (44) | 40 | 8,006 | 5.0 | 5.5 (2.7–11) | < 0.001 |

| 4 | 492 (3) | 7 | 485 | 14.4 | 16 (5.9–43) | < 0.001 |

| Preoperative SCr | 70 (25–1,125) | 78 (49–150) | 70 (25–1,125) | 1.004 (1.00–1.01) | 0.007 | |

| Preoperative eGFR, median (range)c | 85 (3–160) | 68 (30–108) | 85 (3–160) | 0.97 (0.95–0.98) | < 0.001 | |

| 1 (> 90 mL/min) | 6,519 (35) | 9 | 6,510 | 1.4 | Reference | |

| 2 (60–89 mL/min) | 9,917 (53) | 29 | 9,888 | 2.9 | 2.1 (1.0–4.5) | 0.05 |

| 3 (30–59 mL/min) | 2,023 (11) | 19 | 2,004 | 9.4 | 6.9 (3.1–15) | < 0.001 |

| 4 (15–29 mL/min) | 81 (0.4) | 1 | 80 | 12.5 | 9.0 (1.1–72) | 0.04 |

| 5 (< 15 mL/min) | 35 (0.2) | 0 | 35 | 0 | – | – |

| Preoperative hemoglobin, (missing, n = 72) | ||||||

| median (range) | 138 (76–189) | 135 (103–163) | 138 (80–189) | 0.97 (0.95–0.99) | 0.001 | |

| Preoperative anemiad | ||||||

| No | 16,423 (88) | 47 | 16,376 | 2.9 | Reference | |

| Yes | 2,080 (11) | 11 | 2,069 | 5.3 | 1.9 (0.96–3.6) | 0.07 |

| Diagnosis | ||||||

| Primary osteoarthritis | 15,467 (83) | 47 | 15,420 | 3.0 | Reference | |

| Other diagnosis | 3,073 (17) | 10 | 3,063 | 3.3 | 1.1 (0.54–2.1) | 0.8 |

In this column, numbers mean number of patients and percentage in parentheses unless otherwise stated.

ASA classes 1 and 2 were combined for the regression analysis.

eGFR calculated using CKD-EPI formula.

Anemia was defined as hemoglobin <117 g/L in women and <134 g/L in men.

Table 2.

Association between perioperative factors and AKI; univariable regression results

| Descriptor | All patientsa | AKI | Non-AKI | incidence per 1,000 operations | OR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Operation type | ||||||

| Primary | 15,943 (85) | 44 | 15,899 | 2.8 | Reference | |

| Revision | 2,632 (15) | 14 | 2,618 | 5.3 | 1.9 (1.1–3.5) | 0.03 |

| Knee operation type | ||||||

| Unicondylar | 607 (6) | 1 | 606 | 1.7 | Reference | |

| Total | 9,147 (94) | 34 | 9,113 | 3.7 | 2.3 (0.31–17) | 0.4 |

| Bilateral operation | ||||||

| No | 16,908 (91) | 55 | 16,853 | 3.3 | Ref | |

| Yes | 1,667 (9) | 3 | 1,664 | 1.8 | 0.55 (0.17–1.8) | 0.3 |

| Prothesis fixation method (missing n = 1,410) | ||||||

| Cementless | 4,107 (24) | 6 | 4,101 | 1.4 | Reference | 0.2 |

| Hybrid | 2,595 (15) | 7 | 2,591 | 2.7 | 1.9 (0.62–5.5) | 0.3 |

| Total cement | 10,460 (61) | 35 | 10,425 | 3.4 | 2.3 (0.96–5.5) | 0.06 |

| Use of antibiotic-impregnated bone cement (missing, n = 589) | ||||||

| Gentamycin | 11,764 (94) | 40 | 11,724 | 3.4 | ||

| Tobramycin | 541 (4) | 0 | 541 | 0 | ||

| Other | 164 (1) | 0 | 164 | 0 | ||

| Antibiotic prophylaxis (missing, n = 592) | ||||||

| Cefuroxime | 17,714 (99) | 48 | 17,666 | 2.7 | Reference | 0.005 |

| Clindamicin | 207 (1) | 3 | 204 | 14.7 | 5.4 (1.7–17) | 0.005 |

| Other | 62 (0.3) | 1 | 61 | 16.4 | 6.0 (0.82–44) | 0.08 |

| Anesthesia modality (missing, n = 105) | ||||||

| Spinal | 2,077 (11) | 4 | 2,073 | 1.9 | Reference | 0.8 |

| Continuous spinal | 1,710 (9) | 7 | 1,703 | 4.1 | 6.3 (0.66–61) | 0.2 |

| Combined spinal epidural | 14,302 (77) | 44 | 14,258 | 3.1 | 3.0 (0.41–23) | 0.4 |

| General | 287 (2.0) | 1 | 286 | 3.5 | 8.3 (0.52–133) | 0.6 |

| Other | 94 (0.5) | 0 | 94 | 0 | 1 | |

| Duration of operationb (missing, n = 110) | ||||||

| median (range) | 10 (10–68) | 12 (6–25) | 10 (10–68) | 1.0 (1.0–1.1) | 0.07 |

In this column, numbers mean number of patients and percentage in parentheses unless otherwise stated.

Duration in 10-min intervals (time from incision to end of wound closure).

Pre- and postoperative serum creatinine (SCr) levels were obtained from the database of a local laboratory that provides our hospital, an adjacent university hospital, and the majority of the communities in the catchment area with laboratory services. The SCr level is routinely obtained as part of the pre-anesthesia evaluation carried out 1–2 months before the operation, but measurements taken within 6 months before the operation were approved. If multiple preoperative SCr measurements were recorded, the most recent SCr measurement was used. Postoperatively, SCr was measured for clinical indications only and not routinely. In our study, we took account of all postoperative SCr measurements taken ≤7 days after the operation, which was done in 5,609 operations (30%). These patients had lower eGFR preoperatively (76 mL/min/1.73 m2 vs 87 mL/min/1.73 m2), older mean age (76 years vs 67 years), higher ASA classification (median 3 vs. 2), and a slightly longer mean duration of operation (105 min vs. 100 min) than patients with no SCr measurement done during the first 7 postoperative days. Of these patients, 39% (2,210) were male and 22% (1,222) had revision arthroplasty. There were also 5,361 patients (29%) who lacked postoperative laboratory follow-up after discharge from our unit because their home county used a different laboratory. We included these patients in our analysis to maximize the number of AKI cases and therefore to maximize statistical power. As the characteristics of these patients differed slightly from those of the patients who were examined in our laboratory (data not shown), we excluded these patients from the sensitivity analysis to eliminate a possible source of bias.

We used SCr to classify all the patients into one of the RIFLE classifications (risk, injury, failure) or into a non-AKI group (Bellomo et al. 2007). We assumed that the patients who were not tested for postoperative SCr would not have had postoperative AKI. To maintain high specificity, those patients who were in the risk of AKI class were classified as not having AKI. We used preoperative SCr to calculate the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) using the CKD-EPI formula (Levey et al. 2009).

In patients who developed AKI (class I or F according to the RIFLE criteria), we reviewed the medical records in order to define the possible pre- and postoperative risk factors associated with AKI (Table 4), and the outcome of AKI. We classified the outcome as spontaneous return of kidney function, loss of kidney function, or end-stage kidney disease.

Table 4.

Factors possibly contributing to development of AKI in 58 patients

| Risk factor | Frequency (missing) |

|---|---|

| ASA class ≥3 | 47 (2) |

| Baseline BP ≤80 mmHga | 14 (4) |

| Blood transfusion | 14 (5) |

| BMI ≥30 | 26 (12) |

| Duration ≥120 min | 30 (2) |

| eGFR ≤90 mL/min | 49 |

| Medication combinationb | 10 (9) |

| Perioperative NSAIDs | 20 (9) |

| Preoperative anemiac | 11 |

| Use of vasoactivesd | 22 (4) |

Perioperative blood pressure.

Concomitant use of 3 or more of the following drugs in perioperative period: diuretics, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEis) or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), NSAIDs.

Anemia was defined as hemoglobin <117 g/L in women and <134 g/L in men.

Atropine or etilefrine.

Statistics

For the statistical analyses, we identified the AKI cases using the criteria described above. Furthermore, we used all the non-AKI patients as a control group. 95% confidence interval (CI) for the incidence rate of postoperative AKI was calculated using the Wilson score interval. The relationship between potential risk factors and AKI was analyzed using univariable binary logistic regression. Multivariable binary logistic regression analysis was performed using the enter method to minimize bias. To create a multivariable model, we used a directed acyclic graph (DAG) to establish a causal relationship between variables and to find a minimal adjustment set to minimize bias. Due to the complexity of the causal relationships among all variables associated with AKI, we used the Dagitty tool (Textor et al. 2011) to create the multivariable model. We chose duration of operation as an exposure variable and AKI as an outcome variable. The Dagitty model showed that BMI, fixation technique, bilateral operation, and operation type and joint was the minimal sufficient adjustment set to minimize bias. We also included the ASA classifications and preoperative eGFR in the multivariable model according to clinical experience (see Supplementary data) and because these variables were interesting for our study hypothesis. We performed a sensitivity analysis that included only the minimal adjustment set to make sure that the results remained unchanged when the ASA classifications and eGFR were added to the model. A Kaplan-Meier analysis was performed to determine the effect of AKI on survival rates. The results were considered statistically significant when the p-value was <0.05. As the incidence of AKI is very low, all the odds ratios provided can be interpreted as relative risk (RR) unless otherwise stated. We used SPSS 21 software for the statistical analysis.

Ethics

In Finland, ethical committee approval is not required in retrospective studies with no human subjects, such as this one. The study was accepted by Pirkanmaa hospital district (ETL-code 13501) on Mar 1, 2013.

Funding and potential conflict of interest

We are grateful for the financial support for the project given by the Finnish Arthroplasty Association (Suomen Artroplastiayhdistys) in 2012. No competing interests declared.

Results

58 cases of AKI were identified in 18,575 patients. Among the 13,214 patients whose specimens were tested by our hospital laboratory, 44 AKI cases were identified and the incidence of AKI was 3.3 per 1,000 operations (95% CI: 2.5–4.5). Of the 58 patients with AKI, 43 had injury- and 15 had failure-stage AKI. In univariable analysis, the risk factors for AKI preoperatively were age, BMI, ASA classification, SCr, eGFR, and hemoglobin value (Table 1), and perioperatively the risk factors were operation type and intravenous antibiotic prophylaxis (Table 2). The multivariable model showed that duration of operation, ASA classification, BMI, and preoperative eGFR were independent risk factors for postoperative AKI (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariable regression results

| Descriptor | OR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Duration of operationa | 1.1 (1.0–1.2) | 0.003 |

| ASA classification | ||

| 1 and 2 | Reference | |

| 3 | 4.4 (1.8–11) | 0.002 |

| 4 | 13 (3.7–46) | < 0.001 |

| Bilaterality | ||

| Unilateral | Reference | |

| Bilateral | 0.31 (0.06–1.6) | 0.2 |

| Body mass index | 1.1 (1.0–1.1) | 0.02 |

| Fixation technique | ||

| Cementless | Reference | |

| Hybrid | 1.7 (0.56–5.1) | 0.3 |

| Total cement | 1.2 (0.39–3.7) | 0.8 |

| Joint | ||

| Hip | Ref | |

| Knee | 1.0 (0.43–2.5) | 1 |

| Operation type | ||

| Primary | Reference | |

| Revision | 0.46 (0.12–1.7) | 0.2 |

| Preoperative eGFRb | 0.98 (0.97–1.0) | 0.03 |

Duration in 10-min intervals (from incision to end of wound closure).

eGFR calculated using CKD-EPI formula.

Sensitivity analysis was performed to determine whether these results were also valid in the primary arthroplasty group (n = 15,943). Multivariable analysis demonstrated the same independent risk factors for AKI as identified in the original analysis. We also repeated the analysis with adjustment for only the variables in the minimal sufficient adjustment set, and the results remained unchanged, confirming that both duration of operation and BMI were independent risk factors for AKI. In the third sensitivity analysis, we excluded all 5,361 patients (14 of 58 AKI cases) with a different laboratory register in their community and thus possibly lacking a 7-day postoperative laboratory follow-up. This analysis showed the same independent risk factors for AKI.

A potential cause of AKI was identified in 28 cases. The most common conditions were postoperative infections in 15 patients, cardiac causes in 5 patients, and pseudo-obstruction in 5 patients. In 28 cases, no specific cause could be identified retrospectively. Most patients had several factors that possibly contributed to the development of AKI (Table 4). 2 of the AKI patients had no patient records concerning the postoperative period, so the reason for AKI could not be found. 2 patients with AKI underwent postoperative dialysis for less than 4 weeks and both recovered their kidney function. Thus, neither of these patients was classified in the loss of kidney function group or the end-stage kidney disease group.

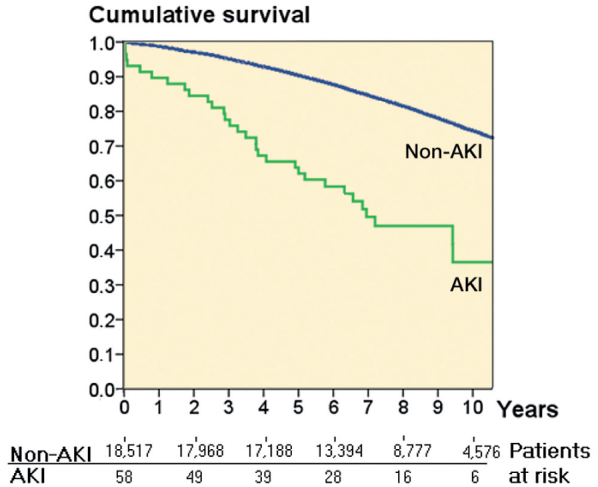

Mortality was substantially higher in AKI patients than in non-AKI patients throughout the follow-up (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Survival curve, with all-cause mortality as endpoint.

Discussion

Despite the fact that preoperative kidney dysfunction according to eGFR is common in our Scandinavian population (65% of the patients had eGFR <90 mL/min), AKI is rare (with an incidence of 3.3 per 1,000 arthroplasties). We found that duration of operation, preoperative eGFR, ASA class, and BMI were all independent risk factors for postoperative AKI. However, half of all cases of AKI occurred without any underlying cause identified. The survival of patients with AKI was worse than that of non-AKI patients.

The incidence of AKI was lower than that reported by other groups (3.3 per 1,000 vs. 5.5 per 1,000 vs. 52 per 1,000) (Jafari et al. 2010, Kimmel et al. 2014). This might be due to lower BMI (29 vs. 32 and 31), a smaller proportion of general anesthesia (1.5% vs. 6.1% and 60%), a larger proportion of ASA class 1 patients (8.0% vs. 4.8% and 2.8%), and shorter duration of operation (100 min vs 157 min vs 119 min) in our cohort compared to the other cohorts (Jafari et al. 2010, Kimmel et al. 2014). The incidence of AKI was lower compared to Perregaard et al. 2016 (3.3 per 1,000 vs. 21.9 per 1,000). Unlike in our study, they included mild-stage AKI in their analysis, which probably explains the difference.

We found that BMI was an independent risk factor for AKI, a finding supported by previous studies (Jafari et al. 2010. Kimmel et al. 2014). An association has also been shown between lower eGFR and AKI (Jafari et al. 2010, Kimmel et al. 2014, Bell et al. 2015). In univariable analysis, preoperative renal impairment increased doubled the risk of AKI by 2-fold, when eGFR was lower than 90 mL/min and increased it by 7-fold when eGFR was lower than 60mL/min. The indidence of AKI was higher following revision than after primary surgery, but the association was lost in multivariable analysis, probably because revision arthroplasty patients had more factors associated with AKI. In our population, patients undergoing revision arthroplasty generally had a longer duration of operation and a higher ASA class.

Some case reports have suggested that vancomycin-, tobramycin-, and gentamycin-impregnated bone cements may also induce AKI (Curtis et al. 2005, Patrick et al. 2006, Lau and Kumar 2013, Johansson et al. 2016). In our study, aminoglycoside bone cement (94% gentamycin) was used in all patients and still we had a low rate of AKI. Furthermore, AKI rates were similar between cementless, hybrid, and fully cemented arthroplasties.

Our study validates ASA class as an independent risk factor for AKI in arthroplasty patients. This is in accordance with cohorts comprising patients undergoing a large variety of orthopedic operations, including various arthroplasties, fractures, and osteotomies (Bell et al. 2015). Previous studies on arthroplasty patients (Jafari et al. 2010, Kimmel et al. 2014) again included multiple morbidities in the multivariable model alongside the ASA class, which might explain why ASA class was not a significant predictor of AKI in these studies. Our odds ratios in different ASA classes were high, and we suggest that readers should not interpret these results as relative risk.

We are the first group to find that duration of operation was a strong and independent risk factor for AKI. Other studies that have found an insignificant association between duration of operation and AKI were case-control studies with smaller control groups (Jafari et al. 2010, Kimmel et al. 2014) or smaller cohort studies (Weingarten et al. 2012). In our study population, the incidence of AKI almost doubled when the duration of surgery exceeded 120 min. Clinical experience shows that prolonged surgery is usually caused by perioperative problems, and longer duration has plenty of associations with other perioperative factors (for example, blood transfusions, cooling, coagulopathies, and use of anesthetics) that could mediate AKI. However, the systemic inflammation caused by increased tissue damage due to the prolonged duration of the operation and prolonged tourniquet use could also be the explanation (Andres et al. 2003, Basile et al. 2012).

Concerning antibiotic prophylaxis, earlier studies have shown an association between gentamycin and AKI (Ross et al. 2013, Bell et al. 2014, Craxford et al. 2014, Johansson et al. 2016). In our cohort, gentamycin was rarely used. Instead of gentamycin, the secondary option for cefuroxime was clindamycin. However, in the AKI patients, only 3 patients received clindamycin, so significant results in univariable analysis concerning clindamycin should be viewed with caution.

Whenever AKI occurred, its outcome was good—with only 2 of the 58 AKI patients receiving dialysis, and neither of them for more than 4 weeks. This result is in accordance with the earlier literature. Jafari et al. (2010) reported that 7 out of 98 of their AKI patients received dialysis, whereas Kimmel et al. (2014) reported that none of their AKI patients (AKI stage I or F, n = 22) received dialysis postoperatively. Although resolution of kidney function was common, the survival of patients with AKI was surprisingly poor, which warrants further research.

In half of the cases, no specific cause or condition underlying the AKI was found. It is possible that a triggering factor for AKI in these patients might simply be the systemic stress caused by the operation. Post- or preoperative infection, paralytic ileus, and cardiac causes were remarkable factors underlying AKI and served to explain almost half of the AKI cases. By preventing these factors, it might be possible to reduce rates of AKI. We do, however, acknowledge that in some cases the factors leading to AKI could not be identified because of the retrospective nature of the study.

The strength of the present study was the relatively large patient cohort compared to previous studies. We used a full, unselected cohort as controls in our analysis. Moreover, the underlying causes of AKI have not been adequately reported before. The study also had some limitations. Because the records of some patients were not available, there was a lack of information on the underlying reasons for their AKI. As SCr was measured for clinical indications and not routinely in all patients, it is probable that some AKI cases were not identified. Thus, it is likely that more AKI cases would have been found if the SCr of all patients had been screened every day during the first postoperative week. In the earlier literature, not all postoperative SCr levels were recorded either (Jafari et al. 2010), so the results are comparable. Kimmel et al. (2014) had postoperative SCr measured from every patient and reported remarkably higher rates of AKI than ours (52 per 1,000 vs. 3.3 per 1,000). In our study population, the incidence of AKI in patients for whom postoperative SCr was measured was much smaller (10 per 1,000 operations), although this incidence number is probably overstated due to selection bias.

In summary, we found that high rates of AKI might be prevented if the risk profile of patients is favorable. Contrary to our hypothesis, we found very low rates of AKI. The results suggest that the risk of developing AKI is elevated in patients with a duration of operation exceeding 120 min, higher BMI, ASA class ≥3, or impaired kidney function preoperatively (eGFR< 90 mL/min). We therefore suggest careful renal monitoring postoperatively for patients with these risk factors, in order to identify AKI. It is important to find and optimize patients who are at risk of AKI already preoperatively, to prevent future kidney manifestations—and also to communicate the risk to the patient when considering a procedure aimed at improving quality of life in a high-risk patient.

Supplementary data

A directed acyclic graph is available as supplementary data in the online version of this article, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17453674.2017.1301743.

All the authors contributed to the design of the study. PJ collected the data. PJ, EJ, and LPL contributed to the editing of the data. PJ wrote the draft of the manuscript and revised the manuscript according to the corrections made by the other authors.

Supplementary Material

References

- Andres B M, Taub D D, Gurkan I, Wenz J F.. Postoperative fever after total knee arthroplasty: the role of cytokines. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2003; (415): 221–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aveline C, Leroux A, Vautier P, Cognet F, Le Hetet H, Bonnet F.. Risk factors for renal dysfunction after total hip arthroplasty. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim 2009; 28(9): 728–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basile D P, Anderson M D, Sutton T A.. Pathophysiology of acute kidney injury. Compr Physiol 2012; 2(2), 1303–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell S, Davey P, Nathwani D, Marwick C, Vadiveloo T, Sneddon J, Patton A, Bennie M, Fleming S, Donnan PT.. Risk of AKI with gentamicin as surgical prophylaxis. J Am Soc Nephrol 2014; 25(11): 2625–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell S, Dekker F W, Vadiveloo T, Marwick C, Deshmukh H, Donnan P T, Van Diepen M.. Risk of postoperative acute kidney injury in patients undergoing orthopaedic surgery-development and validation of a risk score and effect of acute kidney injury on survival: observational cohort study. BMJ 2015; 11; 351: h5639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellomo R, Kellum J A, Ronco C.. Defining and classifying acute renal failure: from advocacy to consensus and validation of the RIFLE criteria. Intensive Care Med 2007; 33(3): 409–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coca S G, Singanamala S, Parikh C R.. Chronic kidney disease after acute kidney injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Kidney Int 2012; 81(5): 442–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis J M, Sternhagen V, Batts D.. Acute renal failure after placement of tobramycin-impregnated bone cement in an infected total knee arthroplasty. Pharmacotherapy 2005; 25(6): 876–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craxford S, Bayley E, Needoff M.. Antibiotic-associated complications following lower limb arthroplasty: a comparison of two prophylactic regimes. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol 2014; 24(4): 539–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fournier J P, Sommet A, Durrieu G, Poutrain J C, Lapeyre-Mestre M, Montastruc J L.. More on the "Triple Whammy": antihypertensive drugs, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents and acute kidney injury - a case/non-case study in the French pharmacovigilance database. Ren Fail 2014; 36(7): 1166–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jafari S M, Huang R, Joshi A, Parvizi J, Hozack W J.. Renal impairment following total joint arthroplasty: who is at risk? J Arthroplasty 2010; 25(6 Suppl): 49–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson S, Christensen O M, Thorsmark A H.. A retrospective study of acute kidney injury in hip arthroplasty patients receiving gentamicin and dicloxacillin. Acta Orthop 2016; 87(6): 589–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimmel L A, Wilson S, Janardan J D, Liew S M, Walker R G.. Incidence of acute kidney injury following total joint arthroplasty: a retrospective review by RIFLE criteria. Clin Kidney J 2014; 7(6): 546–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lafrance J P, Miller D R.. Acute kidney injury associates with increased long-term mortality. J Am Soc Nephrol 2010; 21(2): 345–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau B P, Kumar V P.. Acute kidney injury (AKI) with the use of antibiotic-impregnated bone cement in primary total knee arthroplasty. Ann Acad Med Singapore 2013; 42(12): 692–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee A, Cooper M G, Craiq J C, Knight J F, Keneally J P.. Effects of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on postoperative renal function in adults with normal renal function. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007; 18;(2): CD002765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levey A S, Stevens L A, Schmid C H, Zhang Y L, Castro A F 3rd, Feldman H I, Kusek J W, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Greene T, Coresh J.. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 2009; 150(9): 604–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielson E, Hennrikus E, Lehman E, Mets B.. Angiotensin axis blockade, hypotension, and acute kidney injury in elective major orthopedic surgery. J Hosp Med 2014; 9(5): 283–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick B N, Rivey M P, Allington D R.. Acute renal failure associated with vancomycin- and tobramycin-laden cement in total hip arthroplasty. Ann Pharmacother 2006; 40(11): 2037–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perregaard H, Damholt M B, Solgaard S, Petersen M B.. Renal function after elective total hip replacement - Incidence of acute kidney injury and prevalence of chronic kidney disease. Acta Orthop 2016; 87(3): 235–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross A D, Boscainos P J, Malhas A, Wigderowitz C.. Peri-operative renal morbidity secondary to gentamicin and flucloxacillin chemoprophylaxis for hip and knee arthroplasty. Scott Med J 2013; 58(4): 209–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Textor J, Hardt J, Knüppel S.. DAGitty: A graphical tool for analyzing causal diagrams. Epidemiology 2011; 22(4): 745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weingarten T N, Gurrieri C, Jarett P D, Brown D R, Berntson N J, Calaro R D Jr, Kor D J, Berry D J, Garovic V D, Nicholson W T, Schroeder D R, Sprung J.. Acute kidney injury following total joint arthroplasty: retrospective analysis. Can J Anaesth 2012; 59(12): 1111–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ympa Y P, Sakr Y, Reinhart K, Vincent J L.. Has mortality from acute renal failure decreased? A systematic review of the literature. Am J Med 2005; 118(8): 827–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.