Abstract

Background

Binge eating is a marker of weight gain and obesity, and a hallmark feature of eating disorders. Yet, its component constructs—overeating and loss of control (LOC) while eating—are poorly understood and difficult to measure.

Objective

To critically review the human literature concerning the validity of LOC and overeating across the age and weight spectrum.

Data sources

English-language articles addressing the face, convergent, discriminant, and predictive validity of LOC and overeating were included.

Results

LOC and overeating appear to have adequate face validity. Emerging evidence supports the convergent and predictive validity of the LOC construct, given its unique cross-sectional and prospective associations with numerous anthropometric, psychosocial, and eating behavior-related factors. Overeating may be best conceptualized as a marker of excess weight status.

Limitations

Binge eating constructs, particularly in the context of subjectively large episodes, are challenging to measure reliably. Few studies addressed overeating in the absence of LOC, thereby limiting conclusions about the validity of the overeating construct independent of LOC. Additional studies addressing the discriminant validity of both constructs are warranted.

Discussion

Suggestions for future weight-related research and for appropriately defining binge eating in the eating disorders diagnostic scheme are presented.

Keywords: Binge eating, loss of control, overeating, validity

Binge eating and overeating are two prevalent obesity-related phenotypes that contribute to excess energy intake and weight gain.1 Binge eating is characterized by the subjective experience of loss of control (LOC) while eating, irrespective of the actual amount of food consumed. Overeating is characterized by eating a large amount of food, irrespective of LOC. Therefore, LOC and overeating are two independent but inter-related constructs.

In addition to being associated with weight-related characteristics, binge eating is a hallmark feature of eating disorders, which affect up to 5% of the population.2 An additional 10–15% of individuals in the community report LOC and overeating behaviors that fail to meet the size and/or frequency thresholds for these diagnoses.3,4 Because LOC and overeating lie at the intersection of obesity and eating disorders, researchers have studied these constructs more closely over the past several decades.

Research suggests that LOC is uniquely related to weight-related and psychosocial outcomes, while overeating may best be conceptualized as a marker of risk for excess weight gain and obesity.5 However, both constructs have been difficult to operationalize and measure reliably because of their complexity and variability in phenotypic presentation. The current paper critically reviews the human literature supporting and challenging the validity of binge eating constructs. Studies related to face, convergent, discriminant, and predictive validity of LOC and overeating are described and synthesized with the goal of highlighting major gaps in the literature and emphasizing priorities for future research.

Methods

Searches of PUBMED and PSYCINFO were conducted between November, 2015 and July, 2016 to identify peer-reviewed articles published in English-language journals. No start date was enforced in the search. Search terms included, “loss of control,” “overeating,” “binge eating,” “objective,” “subjective,” and “large.” Reference lists of identified articles were also searched to locate additional studies.

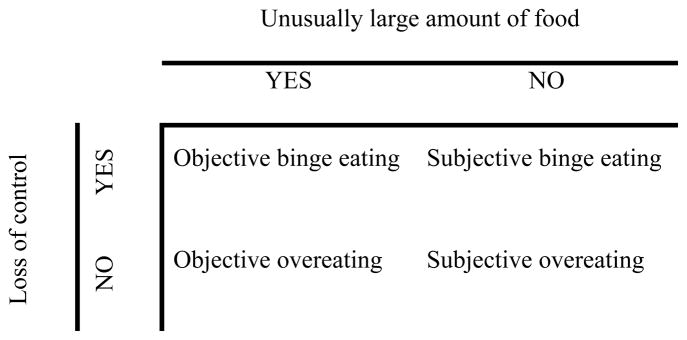

To address whether LOC and overeating are uniquely valid constructs, special efforts were made to identify studies that investigated LOC irrespective of episode size, and overeating irrespective of LOC. Thus, four types of binge eating and overeating episodes were assessed:6 objective binge eating (OBE) involving consumption of an unambiguously large amount of food accompanied by LOC; subjective binge eating (SBE) involving LOC while eating an amount of food that is deemed excessive by the respondent, but is not unusually large according to clinical rating standards; objective overeating (OO) involving consumption of an unambiguously large amount of food in the absence of LOC; and subjective overeating (SO), involving consumption an amount of food that is considered excessive by the respondent, but is not unusually large by clinical rating standards, in the absence of LOC (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Matrix of binge eating constructs

Data addressing face validity (the degree to which the measurement of a construct reflects what it is purported to measure) were included if they pertained to individuals’ appraisals of their own or others’ LOC and/or overeating behaviors. Data concerning convergent validity (the extent to which a construct is related to other constructs to which it should theoretically be related) and discriminant validity (the extent to which a construct empirically differs from theoretically unrelated constructs) were included if they pertained to cross-sectional associations among binge eating constructs and other anthropometric, psychosocial, or behavioral constructs. Data addressing predictive validity (the degree to which a construct predicts meaningful outcomes) were included if they referred to longitudinal outcomes of binge eating constructs, that is, if assessment of binge eating constructs preceded assessment of relevant outcomes. EMA data were included with studies of convergent validity, rather than studies of predictive validity, because although analysis of EMA data is often prospective in that it assesses momentary antecedents and consequences of binge eating constructs, extant EMA studies of binge eating constructs are focused on capturing a cross-section of experiences as opposed to investigating how these constructs longitudinally predict experiential outcomes. Across validity domains, studies that did not attempt to parse the unique effects of LOC and overeating (e.g., comparisons of individuals with BED and healthy controls, which are confounded by size, frequency, and duration criteria for the disorder) were not included.

This review focuses primarily on studies of children and adults with overweight and obesity. However, given the relevance of binge eating constructs to eating disorders classification, studies conducted in eating disordered samples are also included. Although analogue studies have been developed to approximate binge eating in animals,7 these studies were beyond the scope of this review and thus were not included.

Assessment

In order to facilitate an understanding of the ways in which the validity of LOC and overeating have been explored, a detailed description of current methods for measuring binge eating constructs is provided in Table 1. In short, binge eating constructs are most commonly assessed via semi-structured interviews and self-report measures, the latter of which includes pencil-and-paper questionnaires, self-monitoring records, and ecological momentary assessment (EMA). Directly observing binge eating constructs via feeding laboratory paradigms is an alternate methodology that avoids many of the biases inherent in assessments based upon self-report. Emerging research suggests that psychophysiological assessment may also be useful in directly observing objective, in vivo markers of binge eating constructs.

Table 1.

Description of tools for measuring binge eating constructs

| Domain | Description | Strengths | Limitations | Measures | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Respondent-based measures

| ||||||

| Title | Age | Sample items | ||||

| Semi-structured interviews | Trained assessors rate behavioral, cognitive, and affective experiences based on information provided by respondents |

|

|

Eating Disorder Examination6 | 14+* |

|

| Eating Disorders Assessment for DSM-5104 | 18+ |

|

||||

| Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders: Patient Edition105 | 18+ |

|

||||

| Structured Interview for Anorexic and Bulimic Syndromes106 | 18+ |

|

||||

|

| ||||||

| Self-report questionnaires | Respondents read and independently respond to written questions |

|

|

Binge Eating Scale107 | 18+ |

|

| Eating Attitudes Test108 | 11–18* |

|

||||

| Eating Disorder Diagnostic Scale109 | 13–65 |

|

||||

| Eating Disorder Examination-Questionnaire110 | 16+* |

|

||||

| Questionnaire on Eating and Weight Patterns111 | 18+* |

|

||||

| Loss of Control Over Eating scale112 |

|

|||||

| Eating Loss of Control scale113 | 18+ |

|

||||

|

| ||||||

| Self-monitoring | Respondents record the occurrence of target behaviors and their correlates in the natural environment |

|

|

|

||

|

| ||||||

|

Laboratory-based measures

| ||||||

| Feeding laboratory paradigms | Standardized test meals designed to model LOC and/or overeating episodes administered under controlled conditions |

|

|

|

||

|

| ||||||

| Physiological assessment | Physiological responses tracked during exposure to real or imagined food-related cues |

|

|

Neuroimaging |

|

|

| Eye-tracking |

|

|||||

| Other |

|

|||||

Abbreviations: LOC=loss of control

Also available in formats adapted for youth.

Results

Face Validity

A total of 8 adult and 2 pediatric studies addressing the face validity of LOC and overeating were identified; results of these studies are summarized in Table 2. 75–90% of adults identified LOC as critical in their personal appraisals of binge eating, and 43–90% identified overeating.8–10 LOC was identified less frequently than overeating in personal definitions of binge eating among college students and adolescents.11–13 Factors that influenced binge ratings included BED status, gender of raters and models, and sample composition (e.g., lay persons, clinicians).11,14–16

Table 2.

Summary of studies assessing the face validity of binge eating constructs

| Reference | Sample | n | % female | Age | BMI | Procedure | Summary of main findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Adults

| |||||||

| 10 | TS: family practice patients | 243 | 100 | 26.6±5.5 | NR | Participants completed EDE and a subset defined binge eating in their own words | 83% of EDE-defined OBE labeled as binges 42% of EDE-defined SBE labeled as binges 19% of EDE-defined OO labeled as binges 13% of EDE-defined SO labeled as binges 93% of participants required large amount of food to classify binge episodes 90% of participants required LOC to classify binge episodes |

|

| |||||||

| 9 | TS: bariatric surgery | 197 | 100 | 39.8±11.2 | 43.0±6.7 | Eating and Exercise Examination interview for quantity/quality of eating episodes | LOC predicted self-reported binge eating (B=.16, t=5.19***) Of women who self-reported binge eating: 75% reported associated LOC; 25% did not report associated LOC; 61% reported consuming ≥6 or more servings of food; 19% reported consuming 1–4 servings of food Of women who self-reported overeating, 22% reported associated LOC but did not define episodes as binge eating |

|

| |||||||

| 114 | NTS: college students | 99 | 76.8 | 25.5 | NR | Vignettes of a model eating varied according to quantity, duration, and LOC, and rated on binge scales | Larger size [t(95)=340.05***] and LOC [t(98)=119.10***] predicted judgements of episodes as binges |

|

| |||||||

| 14 | NTS: community-based | 48 | 100 | 38.9±11.4 | 34.6 | Participants recorded type/amount of food and duration of eating episodes for 3 weeks; peer and dietitian judges rated randomly selected eating episodes as binges or non-binges | Peer judges more likely than dietitians to label eating episodes as binges for participants with full- (z=4.61***) and subthreshold BED (z=3.09**) Peer κ=.39 Dietitian κ=.44 Peer vs. dietitian κ=.40–.48 Participants vs. peer and dietitian κ=.07–.19 |

|

| |||||||

| 15 | NTS: community-based with BED | 23 | 95.7 | 44.7±10.9 | NR | Vignettes of a model eating varied according to quantity, duration, and LOC, and rated on binge scales | Episodes involving a large quantity of food [F(1,80)=374.93**] or LOC [F(1,80)=109.90***] rated as more binge-like Episodes rated as more binge-like if a large amount of food consumed when LOC was present [F(1,80)=3.95*] Participants with BED rated vignettes involving large amounts of food higher on binge scale compared to undergraduates [F(2,80)=4.92**] |

| NTS: mental health professionals | 34 | 50.0 | 30.2±2.2 | ||||

| NTS: college students | 25 | 88.0 | 40.2±8.1 | ||||

|

| |||||||

| 16 | NTS: college students sample 1 | 238 | 70.0 | 20.2±3.0 | 22.3±3.7 | Videotaped eating episodes varied according to model’s gender and quantity of food, and rated as binges/non-binges | Larger size predicted judgements of episodes as binges [Wald χ2(1)=21.22***] |

| NTS: college students sample 2 | 139 | 66.0 | 19.8±2.8 | 22.4±3.0 | |||

| NTS: college students sample 3 | 83 | 59.0 | 20.6±3.7 | 23.0±3.4 | |||

|

| |||||||

| 11 | NTS: college students | 969 | 64.0 | Range=18–40+ | NR | Participants asked to define binge eating in their own words | ~10–25% of participants endorsed LOC as necessary to define a binge; ~65–75% identified quantity of food consumed as necessary to define a binge Individuals with BED identified LOC in defining a binge more frequently than those without BED [χ2(1)=6.57*] Males and females with and without BED were similarly likely to identify quantity in defining a binge |

|

| |||||||

| 8 | NTS: community-based with BED | 60 | 100 | 42.7±9.9 | 36.2±8.4 | Participants asked to define binge eating in their own words and independent raters coded responses for presence/absence of binge features | 82% of participants included LOC in binge eating definition 43% of participants included eating a large amount of food binge eating definition |

|

| |||||||

|

Youth

| |||||||

| 12 | NTS: school-based | 259 | 41.7 | 14.7 | NR | Participants asked to define binge eating in their own words | 72.2% of participants defined binge eating exclusively in terms of quantity of food eaten 12.9% of participants defined binge eating in terms of quantity, duration, and LOC |

|

| |||||||

| 13 | NTS: community-based adolescent/mother dyads | 19 | 100 | 14.5±1.2 | NR | Focus groups with adolescents who reported LOC eating via phone screen | Few participants directly endorsed LOC or binge eating Binge eaters described as “lacking self control” LOC associated with eating sneakily, negative affective antecedents, short-term relief |

Abbreviations: BMI=body mass index (kg/m2); TS=treatment-seeking; NR=not reported; EDE=Eating Disorders Examination; OBE=objective binge eating; SBE=subjective binge eating; OO=objective overeating; SO=subjective overeating; LOC=loss of control; NTS=non-treatment seeking; BED=binge eating disorder

p≤.05

p<.01

p<.001

Convergent Validity

A total of 39 adult and 26 pediatric studies addressed the convergent validity of LOC and overeating; results are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Summary of studies assessing the convergent validity of binge eating constructs

| Study | Sample | n | %F | Age | BMI | Measurement | Convergence with anthropometric, psychosocial, and behavioral measures | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Domain | Method | |||||||

|

Respondent-based

| ||||||||

|

Adults

| ||||||||

| 70 | NTS: obese with BED | 12 | 100 | 37.9±7.8 | 39.6±6.2 | Energy intake | Interview | OBE>SBE (t=2.71*) |

| % energy from carbohydrate | Interview | OBE>SBE (t=2.79*) | ||||||

| % energy from fat | Interview | OBE=SBE (t=2.20) | ||||||

| % energy from protein | Interview | OBE=SBE (t=0.38) | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 24 | TS: college students enrolled in weight gain prevention program | 294 | 100 | 18.2±0.4 | 23.7±2.9 | BMI | Measured | LOC frequency, r=−.03 |

| Total % body fat | Measured | LOC=no-LOC; LOC frequency, r=.04 | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 50 | TS: AN | 471 | 97.6 | 25.9±7.7 | NR | Eating-related psychopathology | Self-report | OBE=SBE (F=1.87) |

| TS: BN | 836 | Eating-related QOL | Self-report | OBE=SBE (F=3.42) | ||||

| TS: EDNOS | 845 | Negative affect | Self-report | OBE=SBE (F=0.00) | ||||

| TS: BED | 202 | Global functioning | Self-report | OBE=SBE (F=0.93) | ||||

| Negative self-image | Self-report | OBE=SBE (F=0.21) | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 25 | Mixed TS/NTS: BN | 144 | 100 | 25.7±8.8 | 22.9±5.2 | BMI | Self-report | OBE-only=SBE-only |

| Eating-related psychopathology | Self-report | OBE-only=SBE-only [F(1,66)=0.96] | ||||||

| Compensatory behaviors | Self-report | OBE-only=SBE-only [F(4,63)=0.90] | ||||||

| Mixed TS/NTS: subthreshold BN | 60 | Negative affect | Self-report | OBE-only=SBE-only [F(2,64)=2.25] | ||||

| Interpersonal problems | Self-report | OBE-only=SBE-only [F(2,65)=2.11] | ||||||

| Impulsivity | Self-report | SBE-only>OBE-only [F(3,64)=3.42*] | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 17 | TS: bariatric surgery | 180 | 78.3 | 44.8±11.2 | 44.5±6.8 | BMI | Self-report | BED>SBE>no-LOC* |

| Body image distress | Self-report | BED>SBE>no-LOC* | ||||||

| Eating-related distress | Self-report | BED>SBE>no-LOC* | ||||||

| Restraint | Self-report | BED=SBE=no-LOC | ||||||

| TS: weight loss support group | 93 | 91.4 | 55.1±12.4 | 32.7±7.3 | Disinhibition | Self-report | BED>SBE>no-LOC* | |

| Hunger | Self-report | BED>SBE>no-LOC* | ||||||

| Depression | Self-report | BED, SBE>no-LOC* | ||||||

| Mental QOL | Self-report | BED>SBE, no-LOC* | ||||||

| NTS: community-based | 158 | 78.5 | 41.3±13.5 | 24.8±5.1 | Physical QOL | Self-report | BED=SBE; SBE=no-LOC; BED>no-LOC* | |

| Energy intake | Self-report | BED>SBE>no-LOC* | ||||||

| Carbohydrates | Self-report | BED>SBE>no-LOC* | ||||||

| Fat | Self-report | BED>SBE, no-LOC* | ||||||

| Protein | Self-report | BED>SBE, no-LOC* | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 18 | TS: underweight eating disorders with OBE | 33 | 100 | 27.9±6.9 | 15.4±1.6 | BMI | Measured | OBE>SBE, no-LOC (F=8.14**) |

| Eating-related psychopathology | Interview | OBE, SBE>no-LOC (F=4.60*) | ||||||

| Depression | Self-report | OBE=SBE=no-LOC (F=1.07) | ||||||

| Anxiety | Self-report | OBE=SBE=no-LOC (F=1.14) | ||||||

| TS: underweight eating disorders with SBE | 36 | 25.8±10.5 | 14.0±1.3 | Novelty seeking | Self-report | OBE=SBE=no-LOC (F=2.85) | ||

| Harm avoidance | Self-report | OBE=SBE=no-LOC (F=0.50) | ||||||

| Reward dependence | Self-report | OBE=SBE=no-LOC (F=0.32) | ||||||

| Persistence | Self-report | OBE=SBE=no-LOC (F=1.95) | ||||||

| TS: underweight eating disorders with no LOC | 36 | 24.3±9.0 | 14.4±1.7 | Self-directedness | Self-report | OBE, SBE<no-LOC (F=6.33**) | ||

| Cooperativeness | Self-report | OBE=SBE=no-LOC (F=2.93) | ||||||

| Self-transecendence | Self-report | OBE=SBE=no-LOC (F=0.24) | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 32 | TS: diabetes | 274 | 65.0 | 52.5±12.1 | 33.9±6.9 | BMI | Measured | Correlated with binge eating (r=.27*) but not overeating |

|

| ||||||||

| 20 | NTS: community-based with LOC | 16 | 100 | 42.9±10.4 | 31.3±6.7 | BMI | NR | LOC=no-LOC (t=−1.70) |

| NTS: community-based without LOC | 16 | 41.0±14.6 | 28.5±5.6 | Eating-related psychopathology | Interview | LOC>no-LOC (t=−4.63***) | ||

|

| ||||||||

| 53 | Mixed TS/NTS: PD | 101 | 100 | 22.4±5.3 | 22.3±1.9 | Restraint | Self-report | LOC frequency, r=−.22 |

| Disinhibition | Self-report | LOC frequency, r=.35** | ||||||

| Hunger | Self-report | LOC frequency, r=.29** | ||||||

| Body image | Self-report | LOC frequency, r=.21* | ||||||

| Eating-related psychopathology | Interview | LOC frequency, r=.20* | ||||||

| Mood disorder | Interview | LOC frequency, r=.16 | ||||||

| Anxiety disorder | Interview | LOC frequency, r=.23* | ||||||

| Substance use disorder | Interview | LOC frequency, r=.27** | ||||||

| Impulse control disorder | Interview | LOC frequency, r=.32** | ||||||

| Depression | Self-report | LOC frequency, r=.32** | ||||||

| State anxiety | Self-report | LOC frequency, r=.17 | ||||||

| Trait anxiety | Self-report | LOC frequency, r=.15 | ||||||

| Impulsivity | Self-report | LOC frequency, r=.07 | ||||||

| Negative urgency | Self-report | LOC frequency, r=.44*** | ||||||

| Lack of premeditation | Self-report | LOC frequency, r=.25 | ||||||

| Lack of perseverence | Self-report | LOC frequency, r=−.06 | ||||||

| Sensation-seeking | Self-report | LOC frequency, r=.20 | ||||||

| Eating-related QOL | Self-report | LOC frequency, r=.39** | ||||||

| Global functioning | Interview | LOC frequency, r=−.34** | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 28 | NTS: community-based with OBE, SBE, and vomiting (1) | 30 | 100 | 24.3±5.4 | 22.7±2.3 | BMI | 1=2=3=4 (F=2.15) | |

| NTS: community-based with OBE (2) | 86 | 24.7±5.4 | 25.7±6.0 | Social functioning | 1, 2>4 (F=8.94***) | |||

| NTS: community-based with SBE (3) | 30 | 25.2±5.4 | 26.7±6.2 | Psychiatric distress | 1>4 (F=6.05***) | |||

| NTS: community-based with heterogeneous symptoms (4) | 102 | 24.6±5.7 | 25.1±5.3 | Self-esteem | 1<4 (F=6.86***) | |||

| Alcohol use | 1=2=3=4 (F=0.15) | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 19 | NTS: college students with OBE | 52 | 100 | 19.3±1.5 | 23.5±4.5 | BMI | Self-report | OBE>no pathology; OBE=SBE=OO; SBE=OO=no pathology [F(4,333)=9.2**] |

| NTS: college students with SBE | 40 | 19.1±0.8 | 22.1±3.6 | Eating-related psychopathology | Self-report | OBE, SBE>OO, no pathology [F(4,333)=49.7***] | ||

| NTS: college students with OO | 55 | 19.4±2.0 | 21.9±3.2 | Psychiatric distress | Self-report | OBE, SBE>OO, no pathology [F(4,332)=17.8***] | ||

| NTS: college students with no pathology | 145 | 19.3±2.3 | 21.7±3.2 | Eating-related QOL | Self-report | OBE, SBE>OO, no pathology [F(4,333)=48.3***] | ||

|

| ||||||||

| 51 | NTS: BN | 30 | 100 | 25.4±5.5 | NR | Restraint | Self-report | OBE=SBE [F(1,51)=2.0] |

| Cognitive restraint | Self-report | OBE=SBE [F(1,51)=0.3] | ||||||

| Disinhibition | Self-report | OBE=SBE [F(1,51)=2.5] | ||||||

| Hunger | Self-report | OBE=SBE [F(1,51)=1.7] | ||||||

| Eating-related psychopathology | Self-report | OBE>SBE [F(1,51)=11.1**] | ||||||

| Binge frequency | Self-report | OBE>SBE [F(1,51)=8.0**] | ||||||

| NTS: BN with SBE | 24 | 21.4±3.4 | NR | Purge frequency | Self-report | OBE>SBE [F(1,51)=8.3**] | ||

| Depression | Self-report | OBE=SBE [F(1,51)=0.6] | ||||||

| State anxiety | Self-report | OBE=SBE [F(1,51)=0.0] | ||||||

| Trait anxiety | Self-report | OBE=SBE [F(1,51)=0.0] | ||||||

| Alcohol use | Self-report | OBE=SBE [F(1,51)=3.4] | ||||||

| Drug use | Self-report | OBE=SBE [F(1,51)=1.8] | ||||||

| Impulsivity | Self-report | OBE>SBE [F(1,51)=7.8**] | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 54 | NTS: community-based with BED | 18 | 100 | 28.1±10.6 | 27.7±6.5 | Vomiting | Interview | OBE frequency, r=.42**; SBE frequency, r=.40** |

| Laxatives | Interview | OBE frequency, r=.22; SBE frequency, r=.05 | ||||||

| Diuretics | Interview | OBE frequency, r=.21**; SBE frequency, r=.51** | ||||||

| Driven exercise | Interview | OBE frequency, r=.23**; SBE frequency, r=.21** | ||||||

| Restraint | Interview | OBE frequency, r=.47**; SBE frequency, r=.41** | ||||||

| Eating concern | Interview | OBE frequency, r=.51**; SBE frequency, r=.44** | ||||||

| Weight concern | Interview | OBE frequency, r=.50**; SBE frequency, r=.39** | ||||||

| Shape concern | Interview | OBE frequency, r=.53**; SBE frequency, r=.40** | ||||||

| NTS: community-based with BN | 7 | Depression | Self-report | OBE frequency, r=.44**; SBE frequency, r=.33** | ||||

| Anxiety | Self-report | OBE frequency, r=.46**; SBE frequency, r=.36** | ||||||

| Stress | Self-report | OBE frequency, r=.53**; SBE frequency, r=.38** | ||||||

| Drive for thinness | Self-report | OBE frequency, r=.46**; SBE frequency, r=.44** | ||||||

| NTS: community-based with subthreshold BN and BED | 35 | Interospective awareness | Self-report | OBE frequency, r=.49**; SBE frequency, r=.30 | ||||

| Bulimia | Self-report | OBE frequency, r=.69**; SBE frequency, r=.32** | ||||||

| Body dissatisfaction | Self-report | OBE frequency, r=.33**; SBE frequency, r=.27 | ||||||

| Ineffectiveness | Self-report | OBE frequency, r=.46**; SBE frequency, r=.28 | ||||||

| Maturity fears | Self-report | OBE frequency, r=.15; SBE frequency, r=.30** | ||||||

| NTS: community-based with no eating pathology | 21 | Perfectionism | Self-report | OBE frequency, r=.15; SBE frequency, r=.08 | ||||

| Interpersonal distrust | Self-report | OBE frequency, r=.24; SBE frequency, r=.18 | ||||||

| Cognitive restraint | Self-report | OBE frequency, r=.12; SBE frequency, r=.28 | ||||||

| Disinhibition | Self-report | OBE frequency, r=.53**; SBE frequency, r=.26 | ||||||

| Hunger | Self-report | OBE frequency, r=.48**; SBE frequency, r=.23 | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 115 | TS: AN | 26 | 100 | 26.3±9.0 | 21.6±7.3 | Physical QOL | Self-report | Variance for OBE=NS; variance for SBE: β=.38* |

| TS: BN | 4 | |||||||

| TS: BED | 1 | Mental QOL | Self-report | Variance for OBE=NS; variance for SBE=NS | ||||

| TS: EDNOS | 10 | |||||||

| TS: undiagnosed | 12 | Depression | Self-report | Variance for OBE=NS; variance for SBE=NS | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| 63 | TS: BN | 21 | 100 | 27.0±9.9 | 21.5±2.9 | Energy intake | Interview | Degree of LOC, r=.57*** |

| Vomiting | Interview | Positively associated with LOC (estimate=.67; SE=.15***) and energy intake (estimate=.00; SE=.00***) | ||||||

| Hunger prior to eating | Interview | Positively associated with LOC (estimate=.14; SE=.05**) but not energy intake | ||||||

| Feeling compelled to start eating | Interview | Positively associated with LOC (estimate=.58; SE=.05***) but not energy intake | ||||||

| Feeling compelled to continue eating | Interview | Positively associated with LOC (estimate=.67; SE=.04***) but not energy intake | ||||||

| Feeling upset after eating | Interview | Positively associated with LOC (estimate=.56; SE=.04***) but not energy intake | ||||||

| Feeling full after eating | Interview | Positively associated with LOC (estimate=.15; SE=.05***) and energy intake (estimate=.00; SE=.00***) | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 29 | NTS: community-based with OBE | 37 | 100 | 29.4±6.4 | 29.0±7.8 | BMI | Self-report | OBE>SBE (t=2.25*) |

| Eating-related psychopathology | Self-report | OBE=SBE (t=0.08) | ||||||

| Physical QOL | Self-report | OBE=SBE (t=−1.00) | ||||||

| NTS: community-based with SBE | 52 | 28.6±6.5 | 25.7±5.2 | Mental QOL | Self-report | OBE=SBE (t=0.02) | ||

| Psychological distress | Self-report | OBE=SBE (t=−0.24) | ||||||

| Severe mental health impairment | Self-report | OBE=SBE (χ2=0.04) | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 26 | TS: BED | 101 | 100 | 45.7±11.0 | 37.9±7.1 | BMI | NR | OBE=SBE |

| Binge eating severity | Self-report | OBE=SBE | ||||||

| Depression | Self-report | OBE=SBE | ||||||

| Psychiatric distress | Self-report | OBE=SBE | ||||||

| Interpersonal problems | Self-report | OBE=SBE | ||||||

| Restraint | Self-report | OBE=SBE | ||||||

| Hunger | Self-report | OBE=SBE | ||||||

| Disinhibition | Self-report | OBE=SBE | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 30 | NTS: community-based with OBE | 154 | 100 | 26.2±7.0 | 27.4±7.2 | BMI | Self-report | OBE>SBE [F(2,311)=6.7***] |

| Driven exercise | Self-report | OBE=SBE=no-LOC (χ2=4.29) | ||||||

| NTS: community-based with SBE | 68 | 25.6±7.8 | 24.1±5.8 | Vomiting | Self-report | OBE=SBE=no-LOC (χ2=0.10) | ||

| Eating-related psychopathology | Self-report | OBE, SBE>no-LOC | ||||||

| NTS: community-based with no LOC | 108 | 25.4±7.6 | 25.4±5.4 | Physical QOL | Self-report | OBE=SBE=no-LOC | ||

| Mental QOL | Self-report | OBE=SBE=no-LOC | ||||||

| Negative affect | Self-report | OBE>no-LOC; OBE=SBE; SBE=no-LOC [F(2,321)=8.0***] | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 27 | TS: eating pathology with OBE | 56 | 95.0 | 36.3±10.9 | 37.1±3.7 | BMI | Measured | OBE=SBE |

| Binge eating severity | Self-report | OBE=SBE | ||||||

| TS: eating pathology with SBE | 14 | 93.0 | 39.5±11.7 | 37.8±4.5 | Depression | Self-report | OBE=SBE | |

| Psychiatric comorbidity | Interview | OBE=SBE | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 116 | TS: BN | 174 | 100 | 28.4±7.1 | 22.8±4.4 | BMI | NR | OBE+SBE, β=−0.07; OBE-SBE, β=0.08 |

| Weight concern | Interview | OBE+SBE, β=0.07; OBE-SBE, β=0.14 | ||||||

| Shape concern | Interview | OBE+SBE, β=0.18; OBE-SBE, β=0.05 | ||||||

| Restraint | Interview | OBE+SBE, β=−0.03; OBE-SBE, β=0.05 | ||||||

| Depression | Interview | OBE+SBE, β=0.29; OBE-SBE, β=0.02 | ||||||

| Self-esteem | Self-report | OBE+SBE, β=0.12; OBE-SBE, β=0.02 | ||||||

| Psychiatric distress | Self-report | OBE+SBE, β=0.19; OBE-SBE, β=−0.03 | ||||||

| Interpersonal problems | Self-report | OBE+SBE, β=0.16; OBE-SBE, β=0.03 | ||||||

| Social adjustment | Self-report | OBE+SBE, β=0.16; OBE-SBE, β=0.04 | ||||||

| Confidence to resist binge eating | Self-report | OBE+SBE, β=−0.18; OBE-SBE, β=−0.04 | ||||||

| Ability to resist binge eating | Self-report | OBE+SBE, β=−0.24**; OBE-SBE, β=0.20 | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 55 | TS: AN-binge/purge subtype | 70 | 97.1 | 29.5±10.6 | 16.3±1.7 | Eating-related psychopathology | Self-report | AN: OBE frequency, r=.21; SBE frequency, r=.12 BN: OBE frequency, r=.39**; SBE frequency, r=.18 |

| TS: BN | 110 | 98.2 | 30.3±8.0 | 23.0±6.7 | Emotional eating | Self-report | AN: OBE frequency, r=.12; SBE frequency, r=.75** BN: OBE frequency, r=.69**; SBE frequency, r=.02 |

|

|

| ||||||||

| 21 | TS: bariatric surgery with LOC | 123 | 79.0 | 43.8±10.9 | 50.5±9.2 | BMI | Measured | LOC=no-LOC (t=−1.50) |

| Eating-related psychopathology | Self-report | LOC>no-LOC (t=−7.26***) | ||||||

| Depression | Self-report | LOC>no-LOC (t=−5.42***) | ||||||

| TS: bariatric surgery without LOC | 103 | 48.9±7.0 | Physical QOL | Self-report | LOC=no-LOC (t=1.53) | |||

| Mental QOL | Self-report | LOC<no-LOC (t=3.63***) | ||||||

| Night eating | Self-report | LOC>no-LOC (t=−5.51***) | ||||||

| Alcohol use | Self-report | LOC=no-LOC (t=−1.10) | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 22 | NTS: community-based, obese BED | 53 | 62.3 | F:42.6±11.5 M:42.8±9.7 |

F:39.7±5.9 M:35.2±3.9 |

BMI | Self-report | BED=subBED=OO=no pathology |

| Current shape | Self-report | BED=subBED=OO=no pathology | ||||||

| NTS: community-based, obese subthreshold BED | 119 | 66.4 | F:43.2±11.8 M:47.9±13.2 |

F:38.6±5.9 M:37.2±6.5 |

Desired shape | Self-report | BED=subBED=OO=no pathology | |

| Current/ideal difference | Self-report | BED, subBED>OO, no pathology | ||||||

| Weight dissatisfaction | Self-report | BED, subBED>OO, no pathology | ||||||

| NTS: community-based, obese with OO | 60 | 35.0 | F:47.4±8.1 M:47.8±11.0 |

F:39.3±7.0 M:35.6±4.1 |

Weight importance | Self-report | BED>subBED>OO, no pathology | |

| NTS: community-based, obese with no pathology | 160 | 50.0 | F:44.1±10.4 M:50.8±10.5 |

F:37.9±5.4 M:35.0±4.3 |

Stress | Self-report | BED>OO, no pathology (F=3.18*) | |

| Sadness | Self-report | BED>subBED>OO, no pathology (F=8.68***) | ||||||

| Self-esteem | Self-report | BED<subBED, OO, no pathology; subBED<no pathology (F=7.68***) | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 52 | NTS: college students with LOC | 252 | 100 | 20.7±2.0 | NR | Eating-related QOL | Self-report | OBE-only=SBE-only (OR=1.00) |

| NTS: college students without LOC | 297 | Psychiatric comorbidity | Interview | OBE-only=SBE-only (OR=.61) | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| 31 | TS: BN | 112 | 98.0 | 25.0±9.0 | 21.1±2.5 | BMI | Measured | BN>BN with SBE |

| Eating-related psychopathology | Interview | BN=BN with SBE | ||||||

| Compensatory behaviors | Interview | BN=BN with SBE | ||||||

| Psychiatric comorbidity | Interview | BN=BN with SBE | ||||||

| Depression | Self-report | BN=BN with SBE | ||||||

| Anxiety | Self-report | BN=BN with SBE | ||||||

| TS: BN with SBE | 28 | 23.5±3.4 | Stress | Self-report | BN=BN with SBE | |||

| QOL | Self-report | BN=BN with SBE | ||||||

| Self-esteem | Self-report | BN=BN with SBE | ||||||

| Perfectionism | Self-report | BN=BN with SBE | ||||||

| Impulsivity | Self-report | BN=BN with SBE | ||||||

| Interpersonal problems | Self-report | BN=BN with SBE | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 23 | TS: bariatric surgery with LOC | 221 | 86.1 | 43.7±10.0 | 51.1±8.3 | BMI | Self-report | LOC=no-LOC(F=2.39) |

| Depression | Self-report | LOC>no-LOC (F=35.82***) | ||||||

| Mental QOL | Self-report | LOC<no-LOC (F=16.19***) | ||||||

| TS: bariatric surgery without LOC | 131 | Physical QOL | Self-report | LOC<no-LOC (F=8.02**) | ||||

| Eating-related psychopathology | Self-report | LOC>no-LOC (F=59.38***) | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

|

Youth

| ||||||||

| 33 | NTS: school-based with BED | 94 | 3.1 | Range=11–17 | F:24.1±4.8 M:27.4±7.9 |

Obesity status | Measured |

F: BED=subBED=OO=no pathology (χ2=4.62) M: BED, sub-BED, OO>no pathology (χ2=17.10***) |

| NTS: school-based with subthreshold BED | 243 | 7.9 | F:24.3±4.9 M:25.8±6.1 |

Body satisfaction | Self-report |

F: BED, subBED<OO<no pathology (F=66.94***) M: BED<OO, no pathology; BED=subBED; subBED=OO (F=17.75***) |

||

| NTS: school-based with OO | 255 | 6.3 | F:24.4±5.5 M:23.4±5.2 | Depression | Self-report |

F: BED, subBED>OO>no pathology (F=40.42***) M: BED, subBED, OO>no pathology (F=10.47***) |

||

| NTS: school-based with no pathology | 4142 | 1950 | F:23.0±4.9 M:23.0±4.7 | Self-esteem | Self-report |

F: BED, subBED>OO>no pathology (F=62.01***) M: BED, subBED, OO>no pathology (F=27.99***) |

||

| Suicidality | Self-report |

F: BED, subBED, OO>no pathology (χ2=111.72***) M: BED, subBED, OO>no pathology (χ2=36.62***) |

||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 34 | NTS: community-based with LOC | 62 | 64.5 | 12.9 ± 2.8 | 1.4±1.0 (z-score) | BMI | Measured | LOC>no-LOC*** |

| Depression | Self-report | LOC>no-LOC (t=−4.91***) | ||||||

| NTS: community-based without LOC | 157 | 43.9 | 13.2 ± 2.8 | 0.8±1.1 (z-score) | Anxiety | Self-report | LOC>no-LOC (t=−6.14***) | |

| Interpersonal problems | Parent-report | LOC>no-LOC (t=−3.73***) | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 58 | TS: BN with OBE | 27 | 97.5 | 16.1±1.6 | 22.1±3.0 | Compensatory behaviors | Interview | OBE=SBE [F(4,32)=1.79] |

| Eating pathology | Interview | OBE=SBE [F(1,35)=0.72] | ||||||

| TS: BN with SBE | 10 | Depression | Self-report | OBE<SBE [F(1,35)=6.14*] | ||||

| Self-esteem | Self-report | OBE=SBE [F(1,35)=0.02] | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 49 | TS: BN | 128 | 96.1 | 16.4±1.4 | 114.2±25.6 (%EBW) | %EBW | Measured | BN=PD-LOC=PD-noLOC>AN-B/P [F(3,241)=30.72***] |

| Restraint | Interview | BN=PD-LOC=PD-noLOC=AN-B/P [F(3,233)=1.95] | ||||||

| TS: AN-binge/purge | 38 | 97.4 | 15.6±1.8 | 78.2±4.8 (%EBW) | Shape concern | Interview | BN=PD-LOC=PD-noLOC=AN-B/P [F(3,233)=2.19] | |

| Weight concern | Interview | BN=PD-LOC=PD-noLOC=AN-B/P [F(3,233)=1.95] | ||||||

| TS: PD with LOC | 23 | 87.0 | 15.3±1.9 | 105.8±15.0 (%EBW) | Eating concern | Interview | BN>PD-noLOC, AN-B/P; BN=PD-LOC; PD-noLOC=PD-LOC=AN-B/P [F(3,233)=7.53***] | |

| Depression | Self-report | BN=PD-LOC=PD-noLOC=AN-B/P [F(3,233)=0.77; p=.51] | ||||||

| TS: PD without LOC | 56 | 91.1 | 16.2±1.4 | 106.3±13.5 (%EBW) | Self-esteem | Self-report | PD-LOC>BN, PD-noLOC, AN-B/P [F(3,209)=12.45***] | |

|

| ||||||||

| 46 | TS: overweight with BED | 26 | 76.9 | 14.8±0.9 | 1.9±0.4 (z-score) | BMI z-score | Measured | BED=subBED=OO=no pathology |

| TS: overweight with subthreshold BED | 13 | 69.2 | 15.1±0.9 | 1.9±0.6 (z-score) | Weight/shape concerns | Self-report | BED, sub BED>OO, no pathology [F(3,95)=9.17***] | |

| TS: overweight with OO | 18 | 50.0 | 15.4±1.1 | 1.8±0.6 (z-score) | Depression | Self-report | BED>OO, no-pathology; subBED=OO; subBED>no-pathology; OO=no-pathology [F(3,93)=7.39***] | |

| TS: overweight with no pathology | 39 | 76.9 | 15.2±1.1 | 1.8±0.5 (z-score) | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| 3 | NTS: school-based with OBE | 222 | 63.5 | 12–17 | NR | Overweight status | Measured |

F: OBE, OO>no pathology** M: OBE, OO>no pathology** |

| Risky weight control behavior | Self-report |

F: OBE>OO>no pathology* M: OBE, OO>no pathology* |

||||||

| Dieting | Self-report |

F: OBE, OO>no pathology* M: OBE, OO>no pathology* |

||||||

| NTS: school-based with OO | 165 | 61.2 | Body satisfaction | Self-report |

F: OBE, OO<no pathology* M: OBE<OO<no pathology* |

|||

| Cigarette use | Self-report |

F: OBE=OO=no pathology M: OO<OBE, no pathology* |

||||||

| Drug and alcohol use | Self-report |

F: OBE=OO=no pathology M: OBE=OO=no pathology |

||||||

| NTS: school-based with no pathology | 2374 | 51.8 | Self-injury | Self-report |

F: OBE>no pathology; OO>no pathology; OBE=OO* M: OBE, OO>no pathology* |

|||

| Depression | Self-report |

F: OBE>OO>no pathology* M: OBE>OO>no pathology* |

||||||

| Self-esteem | Self-report |

F: OBE<OO<no pathology* M: OBE, OO<no pathology* |

||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 48 | TS: overweight with LOC | 35 | 71.4 | 12.9±1.9 | 179.1±25.4 (adjusted) | Adjusted BMI | NR | LOC=no-LOC [F(1,194)=3.45] |

| Eating-related psychopathology | Interview | OBE>no-LOC; OBE=SBE; SBE=no-LOC [F(8,364)=3.08**] | ||||||

| External eating | Self-report | OBE>no-LOC; OBE=SBE; SBE=no-LOC [F(2,161)=4.36*] | ||||||

| TS: overweight without LOC | 161 | 59.0 | 12.7±1.7 | 169.9±26.8 (adjusted) | Restraint | Self-report | OBE=SBE=no-LOC [F(2,161)=1.23] | |

| Emotional eating | Self-report | OBE>SBE, no-LOC [F(2,161)=14.99***] | ||||||

| Depression | Self-report | OBE>no-LOC; OBE=SBE; SBE=no-LOC [F(2,163)=8.82***] | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 35 | NTS: school-based with LOC | 108 | 69.4 | 13.8±0.9 | 19.0±3.2 | BMI | Self-report | LOC>no-LOC (F=2.01) |

| Restraint | Self-report | OBE, SBE>no-LOC (F=19.62***) | ||||||

| Eating concern | Self-report | OBE, SBE>no-LOC (F=30.91***) | ||||||

| Weight concern | Self-report | OBE, SBE>no-LOC (F=17.56***) | ||||||

| Shape concern | Self-report | OBE, SBE>no-LOC (F=19.28***) | ||||||

| NTS: school-based without LOC | 538 | 55.8 | 13.9±0.9 | 18.6±2.5 | Drive for thinness | Self-report | OBE, SBE>no-LOC (F=14.07***) | |

| Bulimia | Self-report | OBE, SBE>no-LOC (F=24.24***) | ||||||

| Body dissatisfaction | Self-report | OBE>no-LOC; OBE=SBE; SBE=no-LOC (F=7.57***) | ||||||

| Depression | Self-report | OBE>SBE>no-LOC (F=4.03***) | ||||||

| Self-esteem | Self-report | OBE>no-LOC; OBE=SBE; SBE=no-LOC (F=6.34**) | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 57 | NTS: community-based with LOC | 60 | 56.7 | 10.7±1.5 | 23.0±5.0 | Eating-related psychopathology | Interview | LOC>no-LOC** |

| Empathy | Self-report | LOC=no-LOC [F(1,59)=0.08] | ||||||

| Risk-taking | Self-report | LOC=no-LOC [F(1,59)=1.40] | ||||||

| Impulsivity | Self-report | LOC>no-LOC [F(1,59)=8.72**] | ||||||

| Novelty-seeking | Parent-report | LOC=no-LOC [F(1,59)=3.20] | ||||||

| NTS: community-based without LOC | 60 | Harm avoidance | Parent-report | LOC=no-LOC [F(1,59)=1.74] | ||||

| Reward dependence | Parent-report | LOC=no-LOC [F(1,59)=1.12] | ||||||

| Persistence | Parent-report | LOC=no-LOC [F(1,59)=2.59] | ||||||

| Self-directedness | Parent-report | LOC<no-LOC [F(1,59)=5.92*] | ||||||

| Cooperativeness | Parent-report | LOC<no-LOC [F(1,59)=5.88*] | ||||||

| Self-transcendence | Parent-report | LOC=no-LOC [F(1,59)=0.22] | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 56 | TS: overweight with LOC | 4 | 44.0 | 10.1±1.6 | 33.5±4.5 | Restraint | Interview | LOC=no-LOC |

| Eating concern | Interview | LOC>no-LOC*** | ||||||

| TS: overweight without LOC | 23 | Weight concern | Interview | LOC>no-LOC** | ||||

| Shape concern | Interview | LOC=no-LOC | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 36 | NTS: community-based, obese with LOC | 37 | 22.0 | 8.3±1.5 | 27.9±4.2 | BMI | Measured | LOC>no-LOC (F=14.5***) |

| Eating-related psychopathology | Self-report | LOC>no-LOC (F=7.8**) | ||||||

| Body dissatisfaction | Self-report | LOC>no-LOC (F=4.0*) | ||||||

| NTS: community-based, obese without LOC | 75 | 38.0 | 8.7±1.4 | 24.6±4.2 | Anxiety | Self-report | LOC>no-LOC (F=9.9**) | |

| Depression | Self-report | LOC>no-LOC (F=10.0**) | ||||||

| Behavioral problems | Parent-report | LOC=no-LOC (F=0.7) | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 37 | Mixed TS/NTS: overweight with OBE | 70 | 90.0 | 15.2±1.5 | 27.7±6.5 | BMI | Measured | LOC>no-LOC (t=2.05*); OBE=SBE (t=0.54) |

| Systolic blood pressure | Measured | LOC>no-LOC (F=10.36**); OBE=SBE (F=1.27) | ||||||

| Diastolic blood pressure | Measured | LOC=no-LOC (F=0.75); OBE=SBE (F=1.96) | ||||||

| Mixed TS/NTS: overweight with SBE | 80 | 98.0 | 14.5±1.7 | 28.2±4.2 | Waist circumference | Measured | LOC=no-LOC (F=0.98); OBE=SBE (F=0.17) | |

| Triglycerides | Measured | LOC=no-LOC (F=0.03); OBE=SBE (F=1.60) | ||||||

| HDL-cholesterol | Measured | LOC=no-LOC (F=2.76); OBE>SBE (F=4.03*) | ||||||

| Mixed TS/NTS: overweight with no LOC | 179 | 82.0 | 14.8±1.5 | 26.2±7.9 | LDL-cholesterol | Measured | LOC>no-LOC (F=9.90**); OBE>SBE (F=6.30**) | |

| Plasma glucose | Measured | LOC=no-LOC (F=0.14); OBE=SBE (F=0.83) | ||||||

| Metabolic syndrome | Measured | LOC=no-LOC (χ2=0.00); OBE=SBE (χ2=1.85) | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 45 | NTS: community-based with recurrent LOC | 1643 | 84.0 | 14.9±2.7 | 22.1±3.6 | BMI | Measured | Recurrent LOC>non-recurrent LOC>no-LOC [F(2,1587)=34.73***] |

| NTS: community-based with non-recurrent LOC | 156 | 80.1 | 14.8±2.6 | 21.1±3.7 | Eating-related psychopathology | Self-report | Recurrent LOC>non-recurrent LOC>no-LOC [F(2,1640)=240.69***] | |

| NTS: community-based with no LOC | 226 | 56.5 | 15.1±2.8 | 20.0±3.1 | Eating-related QOL | Self-report | Recurrent LOC>non-recurrent LOC>no-LOC [F(2,1640)=264.59***] | |

|

| ||||||||

| 38 | NTS: community-based with OBE | 46 | 60.9 | 12.6±.4 | 1.4±.2 (z-score) | BMI z-score | Measured | OBE, SBE>OO, no pathology (F=5.04**) |

| NTS: community-based with SBE | 42 | 61.9 | 13.4±.4 | 1.4±.2 (z-score) | Eating-related psychopathology | Interview | OBE, SBE>OO, no pathology (F=21.79***) | |

| NTS: community-based with OO | 68 | 50.0 | 13.0±.4 | 1.0±.1 (z-score) | Depression | Self-report | OBE, SBE>OO, no pathology (F=5.83**) | |

| NTS: community-based with no pathology | 211 | 41.7 | 12.5±.2 | .8±.1 (z-score) | Anxiety | Self-report | OBE, SBE>OO, no pathology (F=7.13***) | |

|

| ||||||||

| 39 | Mixed: TS overweight and NTS community-based with OBE | 106 | 60.2 | 13.1±2.6 | Range of means= 1.3±1.2 to 2.4±0.3 (z-score) | BMI z-score | Measured | OBE, SBE>no pathology; OBE>OO SBE=OO [F(3,427)=4.8**] |

| Meal type of episode | Interview | OBE, SBE>OO, normal episode for snack vs. meal [χ2(N=442)=40.3**] | ||||||

| Overeaten/eaten forbidden food before eating episode | Interview | OBE, SBE>OO, normal episode [χ2(N=444)=27.4**] | ||||||

| Negative emotion before episode | Interview | OBE, SBE>OO, normal episode [χ2(N=445)=38.6**] | ||||||

| Mixed: TS overweight and NTS community-based with SBE | 67 | Restricting before episode | Interview | OBE=SBE=OO=normal episode [χ2(N=445)=2.6] | ||||

| Emotional before episode | Interview | OBE=SBE=OO=normal episode [χ2(N=445)=6.6] | ||||||

| Hungry before episode | Interview | OBE=SBE=OO=normal episode [χ2(N=445)=6.3] | ||||||

| Eating despite lack of hunger before episode | Interview | OBE, SBE>OO, normal episode [χ2(N=440)=70.0**] | ||||||

| Tired before episode | Interview | OBE, SBE, OO>normal episode [χ2(N=445)=8.2*] | ||||||

| Mixed: TS overweight and NTS community-based with OO | 106 | With whom during episode | Interview | OBE, SBE>OO, normal episode for eating alone [χ2(N=441)=20.8**] | ||||

| Time of day during episode | Interview | [χ2(N=443)=15.4] | ||||||

| Celebration during episode | Interview | [χ2(N=443)=4.0] | ||||||

| Secretive during episode | Interview | OBE, SBE>OO, normal episode [χ2(N=444)=38.6**] | ||||||

| Numbing out during episode | Interview | OBE, SBE>OO, normal episode [χ2(N=445)=46.7**] | ||||||

| Mixed: TS overweight and NTS community-based with no pathology | 166 | Hiding food during episode | Interview | OBE>SBE, OO, normal episode [χ2(N=442)=18.4**] | ||||

| Eating quickly during episode | Interview | OBE>SBE, OO, normal episode [χ2(N=444)=43.1**] | ||||||

| Eating more than others during episode | Interview | OBE>SBE, OO, normal episode [χ2(N=441)=57.8**] | ||||||

| Location during episode | Interview | SBE>OBE, OO, normal episode for watching television [χ2(N=439)=32.5**] | ||||||

| Negative emotion after eating | Interview | OBE, SBE>OO, normal episode [χ2(N=445)=53.5**] | ||||||

| Guilt/shame after eating | Interview | OBE, SBE>OO, normal episode [χ2(N=445)=46.2**] | ||||||

| Full after eating | Interview | OBE=SBE=OO=normal episode [χ2(N=445)=5.2] | ||||||

| Sick after eating | Interview | OBE>SBE, OO, normal episode [χ2(N=445)=11.6**] | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 41 | NTS: community-based with LOC | 18 | 44.4 | 13.1±2.7 | 1.6±0.9 (z-score) | BMI z-score | Measured | LOC>no-LOC* |

| Eating in response to depression | Self-report | LOC>no-LOC (F=13.2***) | ||||||

| NTS: community-based without LOC | 137 | 54.0 | 14.4±2.3 | 1.0±1.1 (z-score) | Eating in response to anger/anxiety/frustration | Self-report | LOC>no-LOC (F=5.4*) | |

| Eating in response to feeling unsettled | Self-report | LOC>no-LOC (F=12.4**) | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 44 | NTS: community-based with LOC | 15 | 86.7 | 10.0±1.8 | 28.2±8.1 | BMI | Measured | OBE+SBE>OO, no pathology [F(2,158)=3.6*] |

| Eating-related psychopathology | Interview | OBE+SBE>OO, no pathology [F(2,158)=7.8**] | ||||||

| NTS: community-based with OO | 33 | 23.8±8.6 | Depression | Self-report | OBE+SBE=OO=no pathology [F(2,150)=0.19] | |||

| Anxiety | Self-report | OBE+SBE=OO=no pathology [F(2,149)=0.24] | ||||||

| NTS: community-based with no pathology | 114 | 21.9±8.0 | Behavioral problems | Parent-report | OBE+SBE=OO=no pathology [F(2,148)=1.2] | |||

|

| ||||||||

| 42 | Mixed TS/NTS: community-based with LOC | 81 | 63.0 | 12.0±2.7 | 2.0±0.8 (z-score) | BMI z-score | Measured | LOC>no-LOC* |

| Energy intake | Interview | LOC=no-LOC | ||||||

| % energy from carbohydrate | Interview | LOC>no-LOC*; OBE=SBE | ||||||

| Mixed TS/NTS: community-based without LOC | 168 | 51.0 | 12.2±2.6 | 1.6±1.1 (z-score) | % energy from protein | Interview | LOC<no-LOC**; OBE, SBE<OO, no pathology | |

| % energy from fat | Interview | LOC=no-LOC; OBE=SBE | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 43 | TS: diabetic with BED | 42 | 69.0 | 14.0 | 2.4±0.4 (z-score) | BMI z-score | Measured | BED>OO>no pathology** |

| TS: diabetic with subthreshold BED | 135 | 67.4 | 2.3±0.5 | Eating-related psychopathology | Self-report | BED>OO, no pathology** | ||

| TS: diabetic with OO | 164 | 62.2 | 2.2±0.5 | Depression | Self-report | BED>OO, no pathology** | ||

| TS: diabetic with no pathology | 337 | 65.3 | 2.2±0.5 | QOL | Self-report | BED>OO>no pathology** | ||

|

| ||||||||

|

Ecological momentary assessment

| ||||||||

|

Adults

| ||||||||

| 59,65,117 | NTS: community-based obese with BED | 5 | 84.0 | 43.0±11.9 | 40.3±8.5 | Pre-episode negative affect | Self-report | Increased prior to OBE* but not SBE or OO65 OBE and OO more likely on days characterized by high or increasing negative affect Likelihood of SBE did not differ by affect trajectory117 OBE>SBE, OO, normal episode; SBE>normal episode; SBE=OO; OO=normal episode (Wald χ2=15.67**)59 |

| Post-episode negative affect | Self-report | Decreased after OBE* but not SBE or OO65 OBE>SBE, OO, normal episode; SBE>normal episode; SBE=OO; OO=normal episode (Wald χ2=24.39***)59 |

||||||

| Pre-episode hunger | Self-report | OBE<SBE, normal episode; OBE=OO; SBE=OO, normal episode (Wald χ2=18.14***)59 | ||||||

| Post-episode hunger | Self-report | OBE, OO<SBE, normal episode (Wald χ2=39.75***)59 | ||||||

| NTS: community-based obese without BED | 45 | Pre-episode cravings | Self-report | OBE=SBE=OO=normal episode (Wald χ2=8.14)59 | ||||

| Post-episode cravings | Self-report | OBE<SBE; OBE>OO; OBE=normal episode; SBE>OO; SBE=normal episode; OO<normal episode (Wald χ2=25.87***)59 | ||||||

| Location | Self-report | OBE=SBE=OO=normal episode (Wald χ2=1.22)59 | ||||||

| Eating alone | Self-report | SBE>OBE, OO; SBE=normal eating; normal eating=OBE, OO (Wald χ2=13.2**)59 | ||||||

| Eating while watching television | Self-report | OBE=SBE=OO=normal episode (Wald χ2=0.92)59 | ||||||

| Pre-episode eating because others are eating | Self-report | OBE=SBE=OO=normal episode (Wald χ2=2.07)59 OBE=SBE=OO=normal episode | ||||||

| Post-episode eating because others are eating | Self-report | OBE=SBE=OO=normal episode (Wald χ2=5.37)59 | ||||||

| Pre-episode alcohol ingestion | Self-report | OBE=SBE=OO=normal episode (Wald χ2=10.55)59 | ||||||

| Post-episode stressful event | Self-report | OBE=SBE=OO=normal episode (Wald χ2=2.81)59 | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 61,62 | NTS: community-based obese with BED | 9 | 86.4 | 35.7±11.9 | 38.9±8.7 | Pre-episode negative affect | Self-report | Positively associated with LOC [t(1,427)=4.61***]61 Not associated with energy intake [t(1,427)=0.82]61 |

| Post-episode negative affect | Self-report | No main effect for LOC [t(1,427)=1.68]61 No main effect for energy intake [t(1,427)=−1.46]61 Positively associated with energy intake in non-BED [t(1,427)=−2.86**] but not BED61 Positively associated with LOC in BED, irrespective of energy intake, and negatively associated with LOC and energy intake in non-BED [t(1,427)=−2.28*]61 |

||||||

| NTS: community-based without BED | 13 | Post-meal LOC while eating | Self-report | Positively associated with BED status (OR=3.60; SE=0.29***), energy intake (OR=1.00; SE=0.00***), and negative affect (OR=1.16; SE=0.04***) | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| 60 | NTS: AN | 118 | 100 | 25.3±8.4 | 17.2±1.0 | Negative affect | Self-report | OBE,SBE>avoidant eating, restrictive eating>solitary eating (Wald χ2=88.47***) |

| Compensatory behaviors | Self-report | OBE>SBE avoidant eating, restrictive eating; SBE>solitary eating (Wald χ2=87.45***) | ||||||

| Body checking | Self-report | Solitary eating>OBE, avoidant eating>restrictive eating; SBE=binge eating (Wald χ2=29.00***) | ||||||

| Self-weighing | Self-report | OBE=SBE=avoidant eating=restrictive eating=solitary eating (Wald χ2=4.17) | ||||||

| Stress | Self-report | Restrictive eating>OBE, SBE (Wald χ2=65.86***) | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

|

Youth

| ||||||||

| 67 | NTS: community-based with LOC | 59 | 55.9 | 10.8±1.5 | 23.0±5.1 | Energy intake | Interview | LOC>no-LOC across meal types [F(1,106)=4.39*]; binge meal in LOC>normal meal in no-LOC [F(1,157)=4.41*] |

| Carbohydrate | Interview | Binge meal>normal meal in LOC [F(1,366)=6.99**]; binge meal in LOC>normal meal in no-LOC [F(1,150)=9.65**] | ||||||

| Fat | Interview | LOC=no-LOC across meal types; binge meal=normal meal across groups | ||||||

| Protein | Interview | LOC=no-LOC across meal types; binge meal=normal meal across groups | ||||||

| Happy | Interview | Binge meals, regular meals<random signal in LOC [F(2,875)=24.98***]; LOC=no-LOC across meal types; binge meal=normal meal across groups | ||||||

| Sad | Interview | Binge days in LOC>non-binge days in no-LOC [F(1,71)=6.29**]; LOC=no-LOC across meal types; binge meal=normal meal across groups | ||||||

| NTS: community-based without LOC | 59 | Afraid | Interview | LOC=no-LOC across meal types; binge meal=normal meal across groups | ||||

| Upset | Interview | LOC=no-LOC across meal types; binge meal=normal meal across groups | ||||||

| Food/eating-related cognitions | Interview | LOC>no-LOC across meal types [F(1,110)=16.62***]; binge meal, normal meal>random signal in LOC [F(2,892)=43.32***]; binge meal in LOC>normal meal in no-LOC [F(1,113)=16.55***] | ||||||

| Body-related cognitions | Interview | LOC>no-LOC across meal types [F(1,116)=10.14**]; binge meal, normal meal>random signal in LOC [F(2,872)=9.22***]; binge meal in LOC>normal meal in no-LOC [F(1,96)=52.73***] | ||||||

| Hunger | Interview | LOC=no-LOC across meal types; binge meal=normal meal across groups | ||||||

| Satiety | Interview | LOC=no-LOC across meal types; binge meal=normal meal across groups | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 68 | NTS: community-based overweight with LOC | 30 | 100 | 14.9±1.5 | 36.1±7.5 | Interpersonal problems | Self-report | Predictive of LOC eating at between (estimate=0.31; SE=0.14*) and within-subjects level (estimate=0.14; SE=0.07*) |

| Negative affect | Self-report | Not predictive of LOC eating at between- (estimate=1.21; SE=0.76) or within-subjects level (estimate=0.33; SE=0.34) | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 69 | NTS: community-based overweight with LOC | 17 | 100 | 14.8±1.6 | 2.2±0.5 (z-score) | Heartrate | Measured | Positively associated with LOC at within- (estimate=0.02; SE=0.00***), but not between-subjects level |

| Heartrate variability | Measured | Negatively associated with LOC at within- (estimate=−0.01; SE=0.00***), but not between-subjects level | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

|

Feeding laboratory

| ||||||||

|

Adults

| ||||||||

| 71 | NTS: more obese with BED | 12 | 100 | 31.7±1.3 | 41.5±0.9 | Energy intake | Measured |

BED: Binge meal>normal meal [t(1,37)=2.45*] Non-BED: binge meal=normal mean |

| NTS: more obese without BED | 6 | 35.0±2.8 | 40.4±0.5 | % energy from protein | Measured | Binge meal=normal meal across groups | ||

| NTS: less obese with BED | 9 | 33.7±2.2 | 31.1±0.5 | % energy from carbohydrate | Measured | Binge meal=normal meal across groups | ||

| NTS: less obese without BED | 8 | 32.5±1.8 | 30.4±0.5 | % energy from fat | Measured | Binge meal=normal meal across groups | ||

| NTS: normal-weight with no pathology | 7 | 31.1±3.4 | 21.0±0.7 | Satiety | Self-report |

BED: Binge meal>normal meal [t(1,37)=2.45*] Non-BED: binge meal=normal meal for obese |

||

|

| ||||||||

| 72 | TS: BN | 11 | 100 | 24.2±2.2 | −1.5±12.4 (%deviation from EBW) | Energy intake | Measured | Binge meal>normal meal across groups [F(1,19)=27.20***] |

| NTS: No pathology | 10 | 23.9±4.3 | 0.8±10.3 (%deviation from EBW) | Rate of energy intake | Measured | Binge meal>normal meal across groups [F(1,19)=13.23**] | ||

|

| ||||||||

| 73 | TS: BN | 8 | 100 | 23.0±3.5 | 95.1±12.1 (%EBW) | Energy intake | Measured | Mean binge meal>Mean normal meal for multi-course and single item meals (no statistical tests reported) |

|

| ||||||||

| 74 | TS: BN | 8 | 100 | 24.6±5.0 | 19.5±1.8 | Energy intake | Measured |

BN: binge meal>normal meal [t(14)=4.24***] College students: Binge meal=normal meal |

| Rate of eating | Measured |

BN: binge meal>normal meal for multi-item [t(14)=3.63*] but not single-item meal [t(14)=1.26] College students: binge meal=normal meal |

||||||

| NTS: college students | 8 | 25.3±8.0 | 20.2±1.2 | Pre-episode satiety | Self-report | Binge meal=normal meal across groups [F(1,14)=0.71] | ||

| Post-episode satiety | Self-report | Binge meal=normal meal across groups [F(1,14)=2.82] | ||||||

| Control over eating | Self-report | Binge meal<normal mea across groupsl [F(1,14)=9.38**] | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 64 | NTS: community-based with BED | 30 | 100 | 43.8±8.7 | 34.6±6.1 | Energy intake | Measured | Degree of control, r=−.56** |

| NTS: community-based without BED | 30 | 44.7±10.4 | 32.2±6.3 | Depressed mood | Self-report | Self-labeled OBE>self-labeled OO (t=2.51*) Degree of control, r=−.26* |

||

| Anxious mood | Self-report | Self-labeled OBE=self-labeled OO (t=1.95) Degree of control, r=−.21* |

||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 75 | TS: BN | 12 | 100 | 24.1±2.9 | 1.6±11.9 (%deviation from EBW) | Energy intake | Measured |

Multi-item meal: binge meal>multi-item normal meal*; degree of contol, r=.58** for normal meal and r=.61** for binge meal in BN; degree of control, r=NS for normal meal and binge meal in no pathology group Single-item meal: degree of contol, r=.17 for normal meal and r=.63** for binge meal in BN; degree of control, r=.02 for normal meal and r=.00 binge meal in no pathology group |

| NTS: no pathology | 10 | 23.9±4.3 | 0.8±10.3 (%deviation from EBW) | % energy from carbohydrate | Measured | Multi-item binge meal=multi-item normal meal across groups | ||

| % energy from protein | Measured | Multi-item binge meal<multi-item normal meal across groups* | ||||||

| % energy from fat | Measured | Multi-item binge meal=multi-item normal meal across groups | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 76 | NTS: obese with BED | 10 | 100 | 36.2±2.6 | 40.1±3.4 | Energy intake | Measured | Binge meal>normal meal in BED* but not non-BED |

| % energy from protein | Measured | Binge meal=normal meal across groups | ||||||

| NTS: obese without BED | 9 | 39.0±2.9 | 38.8±1.4 | % energy from carbohydrate | Measured | Binge meal=normal meal across groups | ||

| % energy from fat | Measured | Binge meal=normal meal across groups | ||||||

| LOC while eating | Self-report | Binge meal=normal meal across groups | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

|

Youth

| ||||||||

| 77 | NTS: community-based with LOC | 60 | 56.7 | 10.8±1.5 | 23.0±5.0 | Energy intake | Measured |

Parent-child test meal: LOC=no-LOC Child-only snack: LOC>no-LOC* |

| Total protein | Measured |

Parent-child test meal: LOC=no LOC Child-only snack: LOC>no-LOC* |

||||||

| Total carbohydrate | Measured |

Parent-child test meal: LOC=no LOC Child-only snack: LOC=no LOC |

||||||

| NTS: community-based without LOC | 60 | Total fat | Measured |

Parent-child test meal: LOC=no LOC Child-only snack: LOC>no-LOC* |

||||

| LOC while eating | Self-report |

Parent-child test meal: LOC=no-LOC Child-only snack: LOC>no-LOC* |

||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 47 | NTS: overweight with LOC | 22 | 100 | 10.6±1.8 | 2.3±0.4 (z-score) | BMI z-score | Measured | LOC=no-LOC |

| Energy intake | Measured | LOC=no-LOC | ||||||

| NTS: overweight without LOC | 22 | 10.3±2.0 | 2.1±0.4 (z-score) | LOC while eating | Self-report | Predicted by negative affect prior to mood induction in LOC group [α2 (N=22)=7.08*] | ||

|

| ||||||||

| 66 | NTS:community-based with LOC | 110 | 100 | 14.5±1.7 | 1.5±0.3 (z-score) | Pre-episode negative affect | Measured | Energy intake, β=NS |

| Post-episode negative affect | Measured | Energy intake, β=NS | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 40 | NTS: community-based with LOC | 50 | 64.0 | 13.3±2.7 | 27.7±9.9 | BMI | Measured | LOC>no-LOC** |

| Energy intake | Measured | Binge meal>normal meal across groups (estimate=−0.04; SE=0.02**); LOC=no-LOC (estimate=0.00; SE=0.03) | ||||||

| % energy from protein | Measured | LOC<no-LOC across binge and normal meals** | ||||||

| % energy from carbohydrate | Measured | LOC>no-LOC across binge and normal meals* | ||||||

| % energy from fat | Measured | Binge meal=normal meal; LOC=no-LOC | ||||||

| Post-episode anxiety | Self-report | Binge meal=normal meal; positively associated with LOC status* | ||||||

| NTS: community-based without LOC | 127 | 41.7 | 13.6±2.8 | 23.4±7.3 | Post-episode anger | Self-report | Binge meal=normal meal across groups | |

| Post-episode confusion | Self-report | Binge meal=normal meal; positively associated with LOC status* | ||||||

| Post-episode depression | Self-report | Binge meal=normal meal across groups | ||||||

| Post-episode fatigue | Self-report | Binge meal=normal meal across groups | ||||||

| Post-episode tension | Self-report | Binge meal=normal meal across groups | ||||||

| Post-episode vigor | Self-report | Binge meal=normal meal across groups | ||||||

Note: Studies using identical samples are grouped together for ease of reading. Age and BMI reported as means unless otherwise stated. Only comparisons involving binge eating constructs are reported.

Abbreviations: F=female; BMI=body mass index (kg/m2); NTS=non-treatment-seeking; BED=binge eating disorder; OBE=objective binge eating; SBE=subjective binge eating; TS=treatment-seeking; LOC=loss of control; QOL=quality of life; AN=anorexia nervosa; BN=bulimia nervosa; EDNOS=eating disorder not otherwise specified; NR=not reported; PD=purging disorder; OO=objective overeating; NS=not significant; SE=standard error; M=male

p≤.05

p<.01

p<.001

Anthropometric factors

A total of 17 adult and 16 pediatric studies reported on anthropometric characteristics in relation to LOC and/or overeating.

Adults

Of seven adult studies involving controls with no eating pathology, three reported that those with LOC and/or overeating had elevated BMIs relative to those with no LOC or overeating pathology.17–19 However, in two of these studies, BMI differences were found only for those with OBE and not those with SBE.18,19 By contrast, four studies found that BMI did not differ in individuals with LOC and/or overeating compared to those with no LOC or overeating pathology.20–23 One adult study reported elevated %trunk fat, but not total %body fat or %abdominal fat, in those with LOC relative to those without LOC.24 Of 11 adult studies directly comparing those with different forms of LOC and/or overeating, 6 found that OBE, SBE, and/or OO did not differ on BMI,19,22,25–28 while 5 found that BMI was higher in those with OBE relative to those with SBE.17,18,29–31 One adult study reported that BMI was correlated with OBE but not OO frequency,32 while another reported no associations between LOC eating frequency and any anthropometric variables.24

Youth

Of 16 pediatric studies involving controls with no LOC or overeating pathology, 13 found that indices of cardiovascular risk, including BMI and overweight status, were elevated in youth with OBE and/or SBE relative to healthy controls.3,33–45 Of note, in one of these studies, differences in weight status held only for males and not females.33 By contrast, three studies reported no differences in those with OBE, SBE, and/or OO relative to those with no LOC.46–48 Seven pediatric studies reported that individuals with OBE did not differ from those with OO3,33,46 or those with SBE37–39,49 on BMI. Four studies that compared those with OBE and/or SBE to those with OO reported higher BMI in the former than the latter,38,39,43,44 with the exception that Tanofsky-Kraff and colleauges39 reported that youth reporting SBE were similar to those reporting OO on BMI. No pediatric studies reported BMI differences between those with OBE and those with SBE. Finally, 5 pediatric studies reported that youth with OO did not differ from controls on BMI,38,39,44,46 while 3 reported that those with OO had higher BMIs/rates of overweight or obesity than controls (although again, in one study,33 these results pertained only to males).3,33,43

Psychosocial factors

A total of 21 adult and 15 pediatric studies reported on cross-sectional associations between binge eating constructs and psychosocial factors, including eating-related and general psychopathology, quality of life, personality, and interpersonal functioning.

Adults

Of the 21 adult studies, 8 included a control group with no LOC or overeating pathology. All 8 of these studies reported more severe impairment among those with OBE and/or SBE relative to those with no LOC or overeating on at least one index of psychosocial functioning.17–23,30 Of 13 adult studies directly comparing individuals with different forms of LOC and/or overeating, 12 found that those with OBE endorsed similar levels of psychosocial impairment as compared to those with SBE across most measures,18,19,25–31,50–52 while 1 reported greater impairment in those with OBE relative to those with SBE.17 However, the OBE group in this latter study was comprised of individuals with BED; thus, it is unclear whether psychosocial differences were attributable to episode size, frequency, or other diagnostic features of BED. Of only two adult studies reporting on psychosocial functioning in individuals with OO, both found that these individuals endorsed lower impairment than those with LOC, and comparable impairment as compared to those with no eating pathology, on most measures of distress.19,22 Generally, correlations between OBE and SBE frequency and measures of psychosocial impairment were in the moderate to large range.53–55

Youth

Of the 15 pediatric studies, 13 included a control group with no LOC or overeating pathology. Of these, all 13 studies reported more severe impairment among those with OBE and/or SBE relative to those with no LOC or overeating on at least one index of psychosocial functioning.3,33–36,38,43–46,48,56,57 There tended to be fewer differences between youth with LOC and controls with no LOC or overeating pathology on measures of dietary restraint48,56 and personality.57 All six pediatric studies directly comparing individuals with different forms of LOC and/or overeating found that those with OBE endorsed similar levels of psychosocial impairment as compared to those with SBE across most measures;35,38,46,48,49,58 youth with OBE reported greater psychosocial impairment than those with SBE on very few measures.48 Of six pediatric studies reporting on psychosocial functioning in individuals with OO, three found that these individuals endorsed lower impairment than those with LOC, and similar levels of impairment as compared to those with no eating pathology, on most measures of distress.38,43,46 Three studies reported that youth with OO endorsed similar impairment as those with LOC, and/or greater psychosocial impairment than those with no eating pathology on most psychosocial measures.3,33,44

Momentary data

In addition to these distal cross-sectional associations, multiple studies of distress and binge eating constructs have found that LOC frequently occurs in response to negative emotions.

Adults

In adults, one self-report study reported that SBE frequency was correlated with self-reported emotional eating tendencies in individuals with AN-binge/purge subtype, and OBE frequency was correlated with emotional eating tendencies in individuals with BN.55 Data from three independent EMA studies, one dietary recall study, and one laboratory-based study of adults indicated that LOC, particularly in the context of OBE, was associated with elevated pre- and post-episode negative affect pre-episode.59–65 Two adult EMA studies, both of which involved adults with obesity, reported on OO in relation to momentary distress. One of these studies found that that negative affect was not increased prior to OO.65 The other found that pre-episode negative affect was unrelated to energy intake, a potential proxy for OO; post-episode negative affect was related to energy intake in obese individuals without BED, but was unrelated to energy intake in those with BED.61

Youth

Three out of three pediatric self-report studies suggested that LOC eating was associated with eating in response to negative affect,39,41,48 although in one of these studies, associations were only significant for youth with OBE and not SBE.48 Of two laboratory-based studies reporting on negative affect in youth with LOC eating, one found that negative mood ratings predicted the degree to which youth reported LOC during a subsequent test meal,47 while the other found no association between energy intake and negative affect.66 Of two EMA studies of negative affect, both reported that negative affect did not precede LOC eating in adolescents.67,68 In one of these studies, happiness was found to be lower during both binge and normal meals of youth with LOC eating relative to random signal events prompted by the investigators, and sadness was higher on binge days in youth with LOC eating relative to non-binge days of youth without LOC eating.67 Cognitive, stress-related, and interpersonal factors may be more consistently associated with LOC eating episodes in youth.67–69

Eating behavior

Adults

A total of 12 adult studies reported on eating behavior in relation to LOC and/or overeating (as approximated by energy intake), including 5 respondent-based17,59,62,63,70 and 7 laboratory-based studies.64,71–76 The one study17 that specifically investigated binge eating constructs among individuals with eating pathology relative to controls with no eating pathology reported higher overall energy intake in those endorsing LOC and/or overeating relative to controls. Four out of four studies reported that degree of control over eating was highly correlated with energy intake during a self-reported or laboratory-based meal.62–64,75 OBE episodes were associated with greater energy intake than SBE in two out of two studies.17,70 Binge meals were associated with greater energy intake than non-binge meals in six out of six studies,71–76 but, with one exception,72 these findings only applied to individuals with eating disorders and not to healthy controls.

Youth

A total of six pediatric studies reported on eating behavior in relation to LOC and/or overeating, including three respondent-based39,42,67 and three laboratory-based studies.40,47,77 Of five studies generally comparing energy intake in youth with LOC relative to non-LOC controls, three reported no differences between the former and the latter40,42,47 and two reported greater energy intake in youth with LOC relative to controls67,77 (although in Hilbert and colleagues’ 2010 study, differences were reported only during a child-only snack meal). Meals involving LOC were associated with greater energy intake than non-LOC meals in two out of two studies.40,67

Adult and pediatric findings regarding other eating behavior-related variables, such as macronutrient composition, hunger, and satiety, are reported in Table 3.

Discriminant Validity

There were no studies that directly addressed the discriminant validity of binge eating constructs.

Predictive Validity

A total of 9 adult and 8 pediatric studies reported on the predictive validity of binge eating constructs; results of these studies are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Summary of studies assessing the predictive validity of binge eating constructs

| Study | Sample | n | %F | Age | BMI | Predictor | Outcome measure | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Length of F/U¥ |

Domain | Method | |||||||

|

Adults

| |||||||||

| 81 | TS: BN | 85 | 96.5 | 29.5±9.1 | 22.8±5.8 | Baseline SBE frequency | 3y | Remission from BN: OR=0.87* | Interview |

| TS: BED | 133 | 88.0 | 43.9±11.9 | 38.0±7.3 | Remission from BED: OR=0.90* | ||||

|

| |||||||||

| 18 | TS: underweight eating disorders with OBE | 33 | 100 | 27.9±6.9 | 15.4±1.6 | Baseline LOC status | 5m | Increase in BMI: OBE, SBE<no-LOC [F(1,2,68)=5.30**] | Measured |

| Decrease in eating-related psychopathology: OBE=SBE=no-LOC [F(1,2,68)=2.24] | Interview | ||||||||

| Decrease in depression: OBE=SBE=no-LOC [F(1,2,68)=2.97] | Self-report | ||||||||

| Decrease in anxiety: OBE=SBE=no-LOC [F(1,2,68)=1.82] | Self-report | ||||||||

| TS: underweight eating disorders with SBE | 36 | 25.8±10.5 | 14.0±1.3 | Decrease in novelty seeking: OBE=SBE=no-LOC [F(1,2,68)=0.80] | Self-report | ||||

| Decrease in harm avoidance: OBE=SBE=no-LOC [F(1,2,68)=0.60] | Self-report | ||||||||

| Decrease in reward dependence: OBE=SBE=no-LOC [F(1,2,68)=0.21] | Self-report | ||||||||

| Decrease in persistence: OBE=SBE=no-LOC [F(1,2,68)=0.70] | Self-report | ||||||||

| TS: underweight eating disorders with no LOC | 36 | 24.3±9.0 | 14.4±1.7 | Decrease in self-directedness: OBE=SBE=no-LOC [F(1,2,68)=0.75] | Self-report | ||||

| Decrease in cooperativeness: OBE=SBE=no-LOC [F(1,2,68)=0.28] | Self-report | ||||||||

| Decrease in self-transecendence: OBE=SBE=no-LOC [F(1,2,68)=0.16] | Self-report | ||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| 78 | TS: bariatric surgery | 129 | 80.0 | 45.2±11.5 | 44.3±6.8 | Pre-surgical LOC status | 12m | % weight loss: LOC=no-LOC | Measured |

|

| |||||||||

| 79 | TS: bariatric surgery | 183 | 83.1 | 46.0 (median) | 45.1 | Pre-surgical monthly OBE | 3y | Weight change: β=−0.7 | Measured |

| Pre-surgical monthly SBE | Weight change: β=1.8 | ||||||||

| Pre-surgical monthly OO | Weight change: β=−1.6 | ||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| 83 | TS: BN | 80 | 90 | 27.3±9.6 | 23.9±5.5 | Baseline to end-of-treatment change in OBE frequency | 4m | Decrease in eating-related psychopathology: B=0.00; SE=0.01 | Interview |

| Decrease in depression: B=0.03; SE=0.07 | Self-report | ||||||||

| Decrease in anxiety: B=0.12; SE=0.08 | Self-report | ||||||||

| Increase in self-esteem: B=−0.00; SE=0.01 | Self-report | ||||||||

| Baseline to end-of-treatment change in SBE frequency | Decrease in eating-related psychopathology: B=0.03; SE=0.01** | Interview | |||||||

| Decrease in depression: B=0.24; SE=0.08** | Self-report | ||||||||

| Decrease in anxiety: B=0.37; SE=0.09*** | Self-report | ||||||||

| Increase in self-esteem: B=−0.02; SE=0.01 | Self-report | ||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| 80 | TS: BED placeb-responders | 147 | 90.3 | 41.8±9.6 | 35.3±5.3 | Baseline OBE days | 4w | Placebo responders<non-responders [t(446)=2.83**] | Interview |

| Baseline SBE days | Placebo responders>non-responders [t(446)=2.70**] | Interview | |||||||

| TS: BED non-placebo-responders | 304 | ||||||||

| Baseline OO days | Placebo responders=non-responders [t(447)=0.05] | Interview | |||||||

|

| |||||||||

| 30 | NTS: community-based with OBE | 154 | 100 | 26.2±7.0 | 27.4±7.2 | Baseline LOC status | 5y | Increase in BMI: OBE=no-LOC (coefficient=−0.90; SE=0.68); OBE>SBE (coefficient=−2.51; SE=0.79*) | Self-report |

| NTS: community-based with SBE | 68 | 25.6±7.8 | 24.1±5.8 | Increase in eating-related psychopathology: OBE>no-LOC (coefficient=−0.42; SE=0.12*); OBE=SBE (coefficient=−0.17; SE=0.13) | Self-report | ||||

| Decrease in physical QOL: OBE=no-LOC (coefficient=0.22; SE=0.84); OBE=SBE (coefficient=0.23; SE=0.98) | Self-report | ||||||||

| NTS: community-based with no LOC | 108 | 25.4±7.6 | 25.4±5.4 | Decrease in mental QOL: OBE<no-LOC (coefficient=2.16; SE=1.08*); OBE=SBE (coefficient=−0.33; SE=1.25) | Self-report | ||||

| Decrease in negative affect: OBE=no-LOC (coefficient=−1.42; SE=0.77); OBE=SBE (coefficient=1.27; SE=0.89) | Self-report | ||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| 82 | TS: BED | 50 | 100 | 42.4±10.1 | 34.2±7.1 | Baseline OBE frequency | 8w | Binge eating remission: B=0.43* | Self-report |

| Baseline SBE frequency | Binge eating remission: NS | ||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| 23 | TS: bariatric surgery | 361 | 86.1 | 43.7±10.0 | 51.1±8.3 | Baseline LOC status | 2y | % weight loss at all available F/U: F(1,381)=0.03 | Self-report |

| 6m LOC status | % weight loss at 12m and 24m: F(1,252)=4.75* | ||||||||

| 12m LOC status | % weight loss at 24m: F(1,130)=8.79** | ||||||||

|

| |||||||||

|

Youth

| |||||||||

| 118 | TS: obesity | 132 | 62.1 | 13.6±2.2 | 2.2±0.3 (z-score) | Baseline OBE status | 10m | Change in BMI: t=1.11 | Measured |

| Attrition: Wald χ2=1.55 | Measured | ||||||||

| Baseline SBE status | Change in BMI: B=0.27 | Measured | |||||||

| Attrition: Wald χ2=3.96* | Measured | ||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| 84 | NTS: community-based with LOC | 60 | 58.3 | 10.8±1.5 | 23.0±5.0 | Baseline LOC status | 5.5y | BMI at F/U: t(59)=−1.06 | Measured |

| Eating-related psychopathology at F/U: t(59)=−1.22 | Self-report | ||||||||

| NTS: community-based without LOC | 60 | 55.0 | Onset of BED: OR=1.39 | Interview | |||||

| Depression at F/U: t(59)=−0.10 | Self-report | ||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| 85 | NTS: community-based with LOC | 55 | 59.8 | 10.7±1.5 | 24.0±5.5 | Baseline LOC status | 2.2y | Change in BMI: LOC=no-LOC | Measured |

| Onset of BED: LOC>no-LOC [t(46)=2.71**] | Interview | ||||||||

| NTS: community-based with LOC | 57 | Change in eating-related psychopathology: LOC=no-LOC [t(46)=1.78] | Interview | ||||||

| Change in depression: LOC=no-LOC [t(46)=0.27] | Self-report | ||||||||

|

| |||||||||