Abstract

Reproducibility of in vivo research using the mouse as a model organism depends on many factors including experimental design, strain or stock, experimental protocols, and methods of data evaluation. Gross and histopathology are often the endpoints of such research and there is increasing concern about the accuracy and reproducibility of diagnoses in the literature. In order to reproduce histopathological results, the pathology protocol, including necropsy methods and slide preparation, should be followed by interpretation of the slides by a pathologist familiar with reading mouse slides and familiar with the consensus medical nomenclature used in mouse pathology. Likewise, it is important that pathologists are consulted as reviewers of manuscripts where histopathology is a key part of the investigation. The absence of pathology expertise in planning, executing, and reviewing in vivo research using mice leads to questionable pathology-based findings and conclusions from studies, even in high impact journals. We discuss the various aspects of this problem, give some examples from the literature, and suggest solutions.

Histopathological descriptions of the frequency and nature of lesions and disease entities are very often the endpoints in biomedical research conducted in model organisms such as the mouse. In contrast to clinical pathology where endpoints are usually assessed using biochemical and molecular assays, histopathological assessment, whilst using molecular markers and imaging as adjunct qualitative and quantitative techniques, is highly dependent on the individual expertise of trained expert pathologists. Pathologists must not only recognize lesions but also have knowledge of the background diseases of the mice and understand the meaning of the pattern of disease in the whole mouse1–4. Reproducibility of histopathological endpoints therefore depends on the implementation of a common standardized vocabulary, competent work-up, and an in-depth knowledge of the mouse strains under investigation so that, for example, background lesions are not mistaken for those that are experimentally induced. Such knowledge is critical in the design of experiments, as well as in understanding the impact of husbandry, the microbiome, and diet on the interpretation of results2, 5.

In recent years, funding agencies and scientific communities alike have expressed increasing concern about the lack of reproducibility of experiments in the biomedical domain. Attention was initially drawn to this issue by pharmaceutical companies which rely on preclinical, precompetitive research for drug development pipelines6–8. Identification of this problem has been followed by an outpouring of concern from funding agencies such as the U.S. National Institutes of Health9–11 and to an extent journals and professional bodies12–17.

While much attention has been paid to the reproducibility of molecular assays, in vitro (cell culture) assays and the inappropriate application of statistical methods, only recently have the issues surrounding reproducibility in animal experimentation been discussed in depth13. Much of these discussions have concerned husbandry and the effect of diet and microbiome on experimental outcomes18–20, particularly in neuroscience14. However, recent papers have addressed the problem of what a sound histopathological investigation should look like, how to use knowledge of pathology in experimental design, based on the ARRIVE and related guidelines, and the confounding impact of the environment and the gut and skin microbiomes5.

In this paper, we address some of the issues that impact the reproducibility of histopathological findings: (1) lack of pathology expertise, in author lists and in peer-review, (2) poor standards of reporting—illustrated with common errors seen in papers—, and inconsistent pathology nomenclature; and (3) availability of primary data, without which it is impossible to assess a paper without attempting a complete experimental replication21–23. Most importantly, we emphasize that if pathologists are not involved in designing mouse experiments and interpreting lesions, the accuracy of the diagnoses reported and conclusions drawn may be questionable.

The importance of pathologists

Pathology is a medical specialty that requires years of training, experience, and board certification as a minimum. Although pathology has many sub-disciplines, such as mouse pathology, a general pathologist is much more expert than a non-pathologist, and is often sufficient to provide substantial benefit to an animal research study24. However, Investigators often do not have enough funds to pay for research pathology services and/or believe that they can perform histopathology interpretations themselves. Lack of pathology expertise by investigators leads to inaccurate histopathological descriptions of lesions, and often missed, or spurious reporting of pathological findings in publications. Absence of a pathologist may be noticed in the figure legends, which often do not describe the lesions displayed, or in some rare cases, in images that are replicated in various orientations for different lesions or mice25. In some cases, a pathologist was not involved in late or final edits or did not review the galley proofs of an accepted manuscript26, leading to a substantial error in reporting.

In addition to accurate interpretation of data, pathologists are important to ensure proper nomenclature is used when reporting on results. The use of generally accepted pathology nomenclature for unexpected and novel findings leads to publications that can be interpreted by readers, including other pathologists. Rodent pathology terminology often mirrors that used for humans but differences do occur. Pathology of genetically engineered mice often requires interpretation of novel findings since each mouse may have unique lesions not previously reported, especially where the study is the first for a novel gene knockout or treatment. A classic example is the relatively common lesion in mouse hearts that pathologists diagnose as epicardial and myocardial mineralization and fibrosis, but non-pathologists often call “dystrophic cardiac calcinosis” or a variety of other names27–31. Investigators without pathology backgrounds often over-interpret their research findings, the temptation being to fit results to their hypotheses. Over-diagnosis of lesions as malignant when they may be, in fact, benign, hyperplastic, or even normal is a common problem. This latter point emphasizes the value of knowing anatomical differences between the species.

Some examples of errors seen in reported histopathological diagnoses

Besides incomplete reporting of the experimental design, including the pathology protocol, there are common questionable diagnoses that can be found in published results (Table 1)32–34. Often, the figure legends do not describe what is illustrated by the figure, normal tissues are misidentified as lesions, non-neoplastic lesions are reported as cancer, or benign lesions are diagnosed as malignant neoplasms. In addition, inflammatory lesions may be described as neoplasms or “tumors”, benign or malignant.

Our interpretations of histopathology figures in published reports, which we will give as examples, are based solely on our interpretation of what was present in the published figures and not based on microscopic slide review, which may reveal different findings than what is in the published figures. Often the published histopathology figures are small and when enlarged they can lose resolution to the point of being uninterpretable. One of many approaches to this problem is to post additional digital images at a variety of magnifications or whole slide images as supplemental data. Images could also be posted on public websites such the Mouse Tumor Biology Database35, 36, Gene Expression Database37, Pathbase38, 39, and many others5.

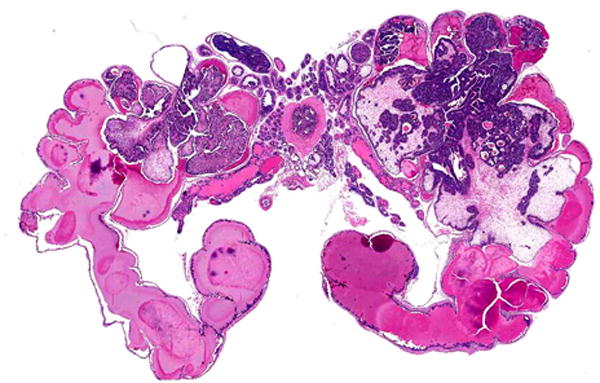

In order to evaluate any organs, a clear understanding of the normal anatomy is absolutely necessary in order to recognize any type of change, be it disease or just subtle changes in normal physiology. When evaluating the skin, the normal hair cycle is a commonly reported source of misinterpretation. All hair follicles regularly go through anagen, the normal growth phase; catagen, the transition stage to telogen, the long term resting stage; to exogen, when the old hair shaft is lost. This process then starts over again and is repeated throughout life. The cycle varies by hair type (vibrissae cycle is different compared to body hair) and species (mice cycle in waves while humans cycle in a mosaic pattern)1. The hypodermal fat layer in the skin changes thickness through the cycle. When thinnest, during telogen phase40, this is often reported as an abnormal phenotype. Sebaceous gland size also changes through the hair cycle, making estimation of the size of this gland an unpredictable feature that is also commonly misinterpreted41. Changes in numbers of hair follicles can be misinterpreted owing to artifacts of section orientation (Fig. 1)42.

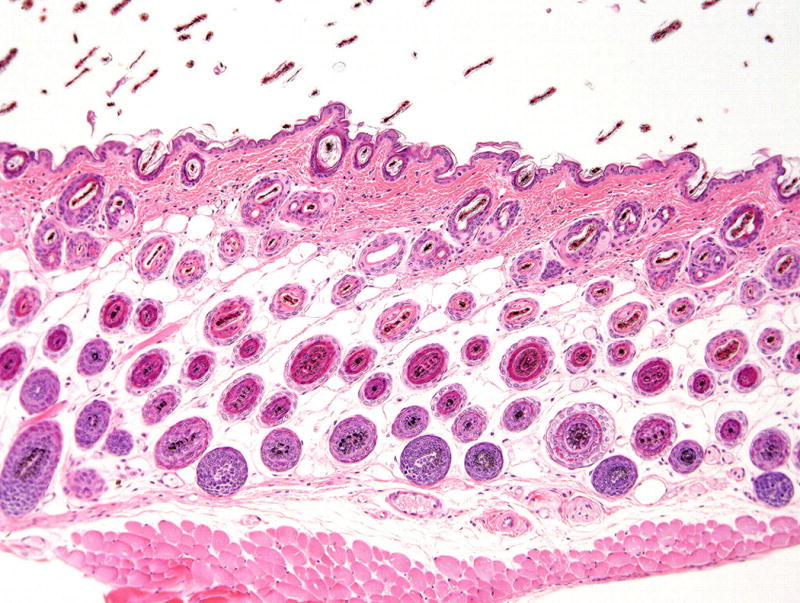

FIGURE 1.

Skin of mouse in anagen with abundant hair follicles.

This normal stage of the cell cycle has been reported to be hyperplasia. Hematoxylin and eosin stain, 10× magnification.

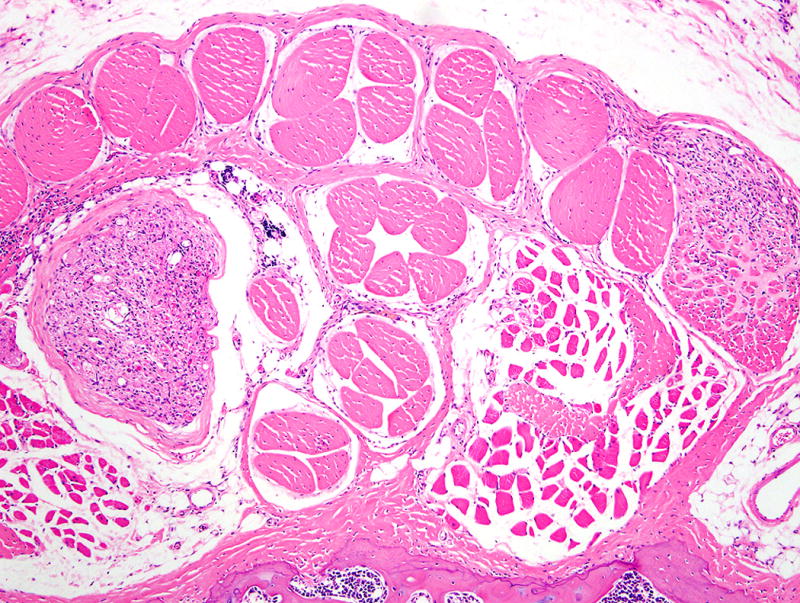

Male mice have modified sebaceous glands (with a large excretory duct along the penis) known as preputial glands; these are also known as clitoral glands in the inguinal area of females (Fig. 2). These tissues have been diagnosed as teratomas or skin tumors33, 43, 44, and an erratum has been published for one of the publications43. Mouse accessory sex glands include various prostate lobes, seminal vesicles, and other structures, the architecture of which differs from that of humans. Tissue artifacts have been diagnosed as early stage prostate cancer45 (Fig. 3).

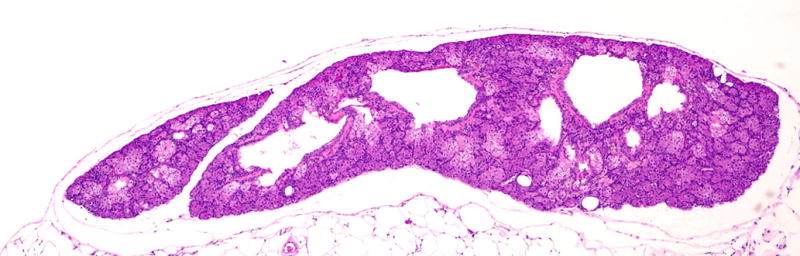

FIGURE 2.

Normal mouse preputial gland showing glandular tissue with central ducts. Two publications reported normal glands as teratomas or carcinomas. Hematoxylin and eosin stain, 4× magnification.

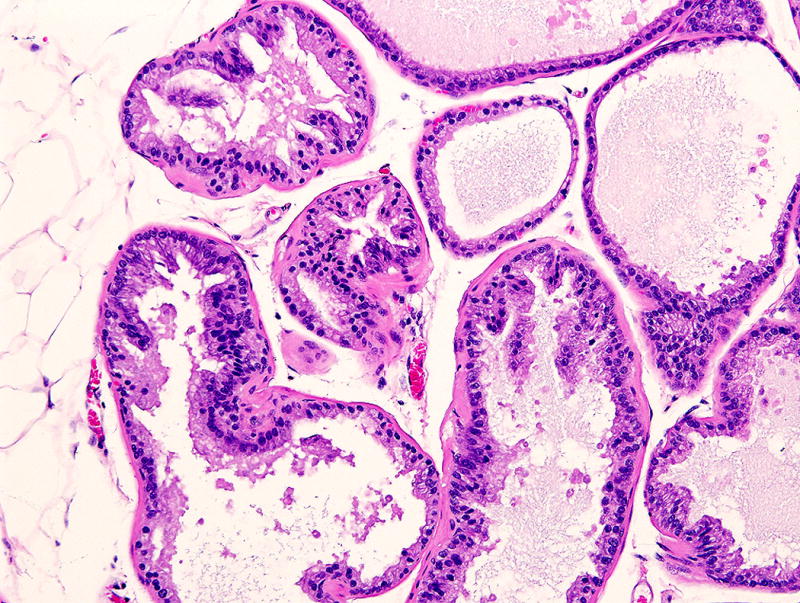

FIGURE 3.

Normal prostate of young mouse with artefactual folds of the acinar epithelium which were misdiagnosed as early stage prostate cancer in a publication. Hematoxylin and eosin stain, 40× magnification.

Immunohistochemistry findings can also be problematic in publications with pathology results. Owing to omission of proper controls, authors often report positive labeling (often with a brown chromogen) of cells and tissues which appear to represent nonspecific background staining46. A good example was reported in mouse prostate epithelial cells and connective tissue47 using an anti-human antibody that was never reported (even by the company selling the antibody) to work in mouse tissues. Mast cells are often nonspecifically positive in mouse tissues using peroxidase based reagents48.

When is a neoplasm not a neoplasm?

Knowledge of appropriate nomenclature is also important for accurate reporting. Neoplasms and their preneoplastic/precancerous lesions are commonly found in mouse experiments involving chemical carcinogens and/or in genetically engineered mice. Many papers involving mice with these induced or spontaneous lesions do not refer to the publications that focus on standardized nomenclature for the organ or disease under investigation, such as those noted above and in our reference list. While many journals list in their “instructions for authors” that they require authors to use standardized nomenclature, this requirement is often not enforced by editors. This policy holds not only for diagnostic terms but also for mouse strain and allele designations, as mouse genetic nomenclature is very uniformly standardized49, 50. Some examples of questionable diagnoses of preneoplastic and neoplastic lesions of mice are given below.

The most widely used prostate cancer mouse model, commonly called TRAMP, is an example of misuse of standardized nomenclature. A search of Mouse Genome Informatics (http://www.informatics.jax.org/genes.shtml) yielded 4 matches (Table 2), only one of which is the transgenic line used for prostate cancer research: Tg(TRAMP)08247Ng51. With over 600 publications, this transgenic line is often considered the best mouse model of human prostate cancer. The Tg(TRAMP)08247Ng line was noted to have a high incidence of prostate adenocarcinoma metastases, suggesting that this was a good model for human prostate cancer. However, these were later shown to be of neuroendocrine origin rather than epithelial, with non-neuroendocrine epithelial being the most common in humans (Fig. 4)51–53. Phylloides prostate carcinomas, initially diagnosed in the first Tg(TRAMP)08247Ng publication, were later shown to be adenomas or benign epithelial-stromal tumors of the seminal vesicles (Fig. 5)51, 54. Metastatic prostate carcinoma to bone marrow was described in a new genetically engineered mouse model, but a pathology nomenclature consensus committee determined that the cases were merely direct invasion from a large prostate mass51, 55.

TABLE 2.

Partial table from Mouse Genome Informatics (Accessed 19 Sept. 2016) to illustrate three genes and one transgene identified by the term TRAMP, three of which are unrelated genes.

| Genetic Location | Symbol | Why Matched |

|---|---|---|

| Chr4 82.89 cM | Tnfrsf25, tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, member 25 | synonym: TRAMP |

| Chr1 4.18 cM | Tram1, translocating chain-associating membrane protein 1 | synonym: TRAMP |

| Chr Unknown | Tg(TRAMP)8247Ng, transgene insertion 8247, Norman M Greenberg | currentSymbol: Tg(TRAMP)8247Ng |

| Chr1 72.12 cM | Dpt, dermatopontin | humanSynonym: TRAMP |

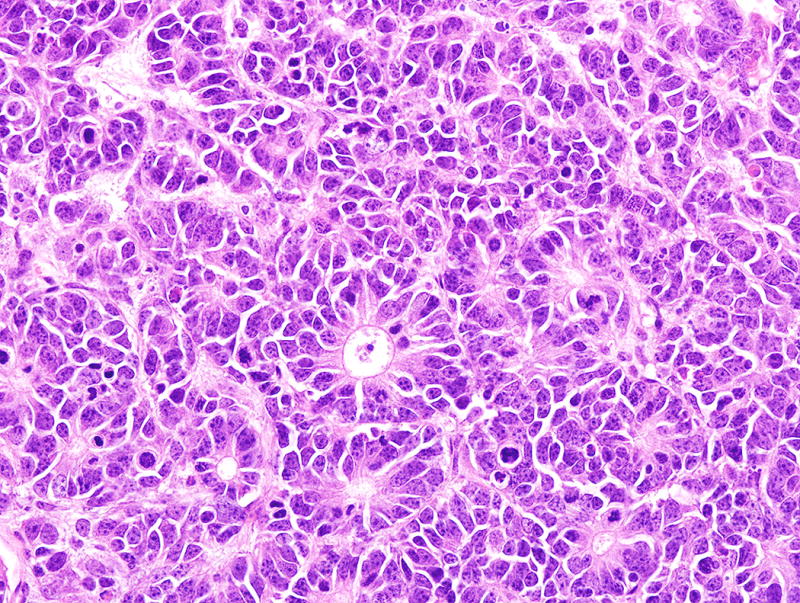

FIGURE 4.

Neuroendocrine carcinoma in the prostate of a TRAMP (Tg(TRAMP)8247Ng) mouse. These mice were reported to develop highly metastatic prostate adenocarcinoma. Hematoxylin and eosin stain, 40× magnification.

FIGURE 5.

Benign (epithelial-stromal) tumor in the seminal vesicles of a TRAMP mouse. Note tumor growth into the lumen and no invasion. These lesions were reported as phylloides prostate carcinomas. Hematoxylin and eosin stain, 4× magnification.

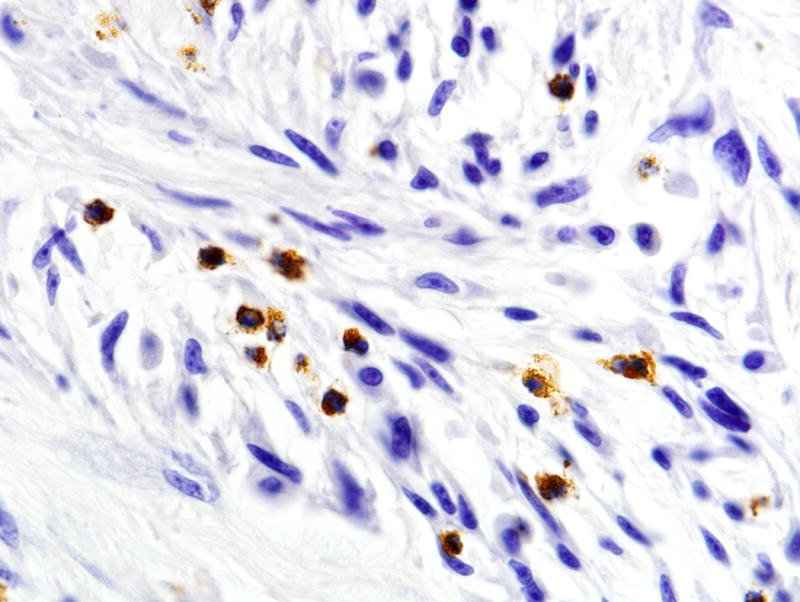

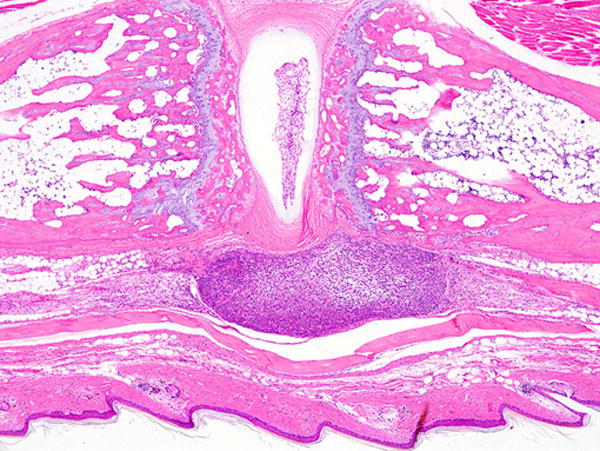

Inflammatory lesions caused by bacteria have sometimes been reported as tumors (neoplasms)56 as have been other types of inflammation57. This may be technically correct, as some textbooks define “tumor” literally as any type of swelling and one of the five cardinal signs of inflammation, but inflammation should and can be easily differentiated from neoplasia. Lymphomas and leukemias are often difficult to diagnose accurately. Tail tumors in transgenic mice were reported to be large granular lymphocytic (LGL) leukemia58 but other investigators working with the same mice found sarcomas of various types including those arising in tendons and nerves in the tail (Figs. 6–8). These tail tumors may have developed accompanying inflammatory responses which included LGLs. Large spleens have been diagnosed as myeloproliferative disorders and leukemias, especially in mice with ulcerative skin lesions which cause reactive myeloid hyperplasia in the spleen59. Using a Helicobacter felis mouse gastric model, a research group developed a model of chronic gastritis that eventually was reported to develop gastric lymphomas. These changes appeared histologically unconvincing as described in the initial publication. However, in this case, a subsequent publication did provide molecular proof that these were indeed lymphomas60.

FIGURE 6.

Tail of a HTLV-I tax transgenic mouse with early tumors (on left and right side) of tendon origin. This mouse was reported to develop leukemia and not tendon tumors. Hematoxylin and eosin stain, 4× magnification.

FIGURE 8.

Early tail tendon sarcoma showing tumor infiltration by myeloperoxidase positive neutrophils. Immunoperoxidase, 40× magnification.

How to increase reproducibility by improving nomenclature usage

Problems in pathology evaluation may occur at various stages of the study leading to questionable pathology interpretation in the manuscript submitted or published. In order to increase reproducibility in mouse studies, a trained pathologist knowledgeable in rodent pathology nomenclature should be involved, either in study design, manuscript writing, or chosen by editors during the peer-review process.

Pathology nomenclature in the paper should follow general guidelines for mouse pathology as published by international committees and experts, as discussed below.

As discussed above, the ability of a pathologist to accurately diagnose lesions in laboratory animals, especially rodents, depends on training and experience. Experience includes the use of widely acceptable veterinary pathology and species specific nomenclature often provided through publications by expert groups of pathologists and by international or national committees33, 61–65 and in books with multiple authors61, 66–69. Others have proposed formal ontologies for data capture and analysis39, 70, 71, which are also based on international nomenclatures and informatics standards.

There are numerous publications on neoplastic diseases in mice, especially in genetically engineered mice (GEM). The NCI Mouse Models of Human Cancer Consortium over the past 15 years has established pathology committees to develop nomenclatures for several important organs33, 51, 61. The publications on neoplastic diseases in mammary gland, prostate, lung, intestine, brain, skin and pancreas provide important guidelines for investigators. (The INHAND pathology nomenclatures have similarly created detailed terminological recommendations for both proliferative and non-proliferative lesions under the auspices of the committees established by a consortium of societies of toxicologic pathology63. These, together with detailed publications on individual classes of lesion, make up a significant terminological corpus with which pathologists making diagnoses should be familiar.

Conclusion

Compared to factors confounding reproducibility of mouse biological experiments originating in experimental design, husbandry, and microbiome, the problem of reliable histopathological interpretation of experimental animals is perhaps one of the most tractable sources of error. Enrollment of an experienced pathologist onto a study early in its inception and planning stages and then its subsequent analysis is clearly highly desirable, as many of the problems we discuss above are unlikely to arise under the guidance of appropriately trained personnel. The issue of finding experienced mouse pathologists has been discussed at length elsewhere2, 24, 34, though the authors feel that the mouse pathology community is sufficiently interactive that good advice can easily be sought out by motivated investigators.

Changes in priorities at journals and funding agencies are also needed to significantly improve the reliability of pathology in mouse model studies. Availability of the primary images on which experimental conclusions are based should be mandatory at journals and in line with the FAIR guidelines5,72. Similarly, funding agencies need to pay more attention to the intended use of histopathology in grant applications and insist on provision of appropriate expertise with an appropriate budget. Increased stringency surrounding the processes of funding and publishing studies might represent more effort for researchers, reviewers, and journal editors, but will reduce the instances of flawed histopathology we see in many journals today73.

FIGURE 7.

Tail of a HTLV-I tax transgenic mouse with an early tumor of tail tendon origin (darker tumor in the lower portion of the figure beneath the skin). This mouse was reported to develop leukemia. Hematoxylin and eosin stain, 4× magnification.

TABLE 1.

Evidence of Questionable Pathology Interpretation in Publications

| Figure legends do not accurately reflect what is in the figure |

| Figure legends do not describe anything in the figure |

| Lack of complete or appropriate necropsies and histopathology |

| Misidentification of normal organs and tissues as lesions |

| Diagnoses of non-neoplastic lesions as neoplasms |

| Diagnoses of tumors with unconventional terminology |

| Reporting of benign lesions as malignant |

| Reporting of inflammatory lesions as tumors |

| Reporting of novel lesions incorrectly |

| Use of incorrect (accepted) terminology/diagnoses |

Acknowledgments

Supported, in part, by NIH Grants R01 AR049288 and R21 AR063781 (to JPS) and by The Warden and Fellows of Robinson College, Cambridge (to PNS).

Footnotes

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS

Dr. Sundberg has a research contract with BIOCON LLC for preclinical trials not involving any part of this article. The other authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Sundberg JPN, L B, Fleckman P, King LE. Skin and adnexa. In: Treuting PM, Dintzis SM, editors. Comparative Anatomy and Histology. Elsevier; Amsterdam: 2012. pp. 433–455. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Treuting PM, et al. The Vital Role of Pathology in Improving Reproducibility and Translational Relevance of Aging Studies in Rodents. Vet Pathol. 2016;53:244–249. doi: 10.1177/0300985815620629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scudamore CL, et al. Recommendations for minimum information for publication of experimental pathology data: MINPEPA guidelines. J Pathol. 2016;238:359–367. doi: 10.1002/path.4642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sundberg JP, et al. Approaches to Investigating Complex Genetic Traits in a Large-Scale Inbred Mouse Aging Study. Vet Pathol. 2016;53:456–467. doi: 10.1177/0300985815612556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schofield PN, Ward JM, Sundberg JP. Show and tell: disclosure and data sharing in experimental pathology. Dis Model Mech. 2016;9:601–605. doi: 10.1242/dmm.026054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Begley CG, Ellis LM. Drug development: Raise standards for preclinical cancer research. Nature. 2012;483:531–533. doi: 10.1038/483531a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Begley CG, Ioannidis JP. Reproducibility in science: improving the standard for basic and preclinical research. Circ Res. 2015;116:116–126. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.303819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prinz F, Schlange T, Asadullah K. Believe it or not: how much can we rely on published data on potential drug targets? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2011;10:712. doi: 10.1038/nrd3439-c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wadman M. NIH mulls rules for validating key results. Nature. 2013;500:14–16. doi: 10.1038/500014a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baker M. 1,500 scientists lift the lid on reproducibility. Nature. 2016;533:452–454. doi: 10.1038/533452a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Collins FS, Tabak LA. Policy: NIH plans to enhance reproducibility. Nature. 2014;505:612–613. doi: 10.1038/505612a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Drucker DJ. Never Waste a Good Crisis: Confronting Reproducibility in Translational Research. Cell Metab. 2016;24:348–360. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Justice MJ, Dhillon P. Using the mouse to model human disease: increasing validity and reproducibility. Dis Model Mech. 2016;9:101–103. doi: 10.1242/dmm.024547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nature Neuroscience. Troublesome variability in mouse studies. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:1075. doi: 10.1038/nn0909-1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baker M. Dutch agency lauches first grants programme dedicated to rpelication. Nature. 2016 doi: 10.1038/nature.2016.20287. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frye SV, et al. Tackling reproducibility in academic preclinical drug discovery. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2015;14:733–734. doi: 10.1038/nrd4737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McNutt M. Journals unite for reproducibility. Science. 2014;346:679. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reardon S. A mouse’s house may ruin experiments. Nature. 2016;530:264. doi: 10.1038/nature.2016.19335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Servick K. Of mice and microbes. Science. 2016;353:741–743. doi: 10.1126/science.353.6301.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stappenbeck TS, Virgin HW. Accounting for reciprocal host-microbiome interactions in experimental science. Nature. 2016;534:191–199. doi: 10.1038/nature18285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morrison SJ. Time to do something about reproducibility. eLife. 2014;3 doi: 10.7554/eLife.03981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maher B. Cancer reproducibility project scales back ambitions. Nature. 2015 doi: 10.1038/nature.2015.18938. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ward A, Baldwin TO, Antin PB. Research data: Silver lining to irreproducibility. Nature. 2016;532:177. doi: 10.1038/532177d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sundberg JP, Hogenesch H, Nikitin AY, Treuting PM, Ward JM. Training mouse pathologists: ten years of workshops on the Pathology of Mouse Models of Human Disease. Toxicol Pathol. 2012;40:823–825. doi: 10.1177/0192623312439123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grenz A, et al. Equilibrative nucleoside transporter 1 (ENT1) regulates post-ischemic blood flow during acute kidney injury in mice. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:693–710. doi: 10.1172/JCI60214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 26.Chaudhry A, et al. CD4+ regulatory T cells control TH17 responses in a Stat3-dependent manner. Science. 2009;326:986–991. doi: 10.1126/science.1172702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Frith CH, Ward JM. Color Atlas of Neoplastic and Non-neoplastic Lesions in Aging Mice. Elsevier; Amsterdam: p. 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brunnert SR, Shi S, Chang B. Chromosomal localization of the loci responsible for dystrophic cardiac calcinosis in DBA/2 mice. Genomics. 1999;59:105–107. doi: 10.1006/geno.1999.5862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ivandic BT, et al. New Dyscalc loci for myocardial cell necrosis and calcification (dystrophic cardiac calcinosis) in mice. Physiol Genomics. 2001;6:137–144. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.2001.6.3.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li Q, et al. Mouse genome-wide association study identifies polymorphisms on chromosomes 4, 11, and 15 for age-related cardiac fibrosis. Mamm Genome. 2016;27:179–190. doi: 10.1007/s00335-016-9634-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Valenzuela N, et al. Cardiomyocyte-specific conditional knockout of the histone chaperone HIRA in mice results in hypertrophy, sarcolemmal damage and focal replacement fibrosis. Dis Model Mech. 2016;9:335–345. doi: 10.1242/dmm.022889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ince TA, et al. Do-it-yourself (DIY) pathology. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:978–979. doi: 10.1038/nbt0908-978. discussion 979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cardiff RD, Ward JM, Barthold SW. ‘One medicine–one pathology’: are veterinary and human pathology prepared? Lab Invest. 2008;88:18–26. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barthold SW, et al. From whence will they come? - A perspective on the acute shortage of pathologists in biomedical research. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2007;19:455–456. doi: 10.1177/104063870701900425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bult CJ, et al. Mouse Tumor Biology (MTB): a database of mouse models for human cancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D818–824. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krupke DM, Begley DA, Sundberg JP, Bult CJ, Eppig JT. The Mouse Tumor Biology database. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:459–465. doi: 10.1038/nrc2390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hill DP, et al. The mouse Gene Expression Database (GXD): updates and enhancements. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D568–571. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schofield PN, et al. Pathbase: a new reference resource and database for laboratory mouse pathology. Radiat Prot Dosimetry. 2004;112:525–528. doi: 10.1093/rpd/nch101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schofield PN, Gruenberger M, Sundberg JP. Pathbase and the MPATH ontology. Community resources for mouse histopathology. Vet Pathol. 2010;47:1016–1020. doi: 10.1177/0300985810374845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chase HB, Montagna W, Malone JD. Changes in the skin in relation to the hair growth cycle. Anat Rec. 1953;116:75–81. doi: 10.1002/ar.1091160107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Levkovich T, et al. Probiotic bacteria induce a ‘glow of health’. PLoS One. 2013;8:e53867. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Neutelings T, et al. Skin physiology in microgravity: a 3-month stay aboard ISS induces dermal atrophy and affects cutaneous muscle and hair follicles cycling in mice. npj Microgravity. 2015;1 doi: 10.1038/npjmgrav.2015.1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fu L, Pelicano H, Liu J, Huang P, Lee C. The circadian gene Period2 plays an important role in tumor suppression and DNA damage response in vivo. Cell. 2002;111:41–50. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00961-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nakamura Y, et al. Phospholipase Cdelta1 is required for skin stem cell lineage commitment. Embo J. 2003;22:2981–2991. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Maddison LA, Sutherland BW, Barrios RJ, Greenberg NM. Conditional deletion of Rb causes early stage prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2004;64:6018–6025. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-2509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ward JM, Rehg JE. Rodent immunohistochemistry: pitfalls and troubleshooting. Vet Pathol. 2014;51:88–101. doi: 10.1177/0300985813503571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mirantes C, et al. An inducible knockout mouse to model the cell-autonomous role of PTEN in initiating endometrial, prostate and thyroid neoplasias. Dis Model Mech. 2013;6:710–720. doi: 10.1242/dmm.011445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bolon B, Calderwood-Mays MB. Conjugated avidin-peroxidase as a stain for mast cell tumor. Vet Pathol. 1988;25:523–525. doi: 10.1177/030098588802500619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sundberg JP, Schofield PN. A mouse by any other name. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:1599–1601. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sundberg JP, Schofield PN. Commentary: mouse genetic nomenclature. Standardization of strain, gene, and protein symbols. Vet Pathol. 2010;47:1100–1104. doi: 10.1177/0300985810374837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ittmann M, et al. Animal models of human prostate cancer: the consensus report of the New York meeting of the Mouse Models of Human Cancers Consortium Prostate Pathology Committee. Cancer Res. 2013;73:2718–2736. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-4213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chiaverotti T, et al. Dissociation of epithelial and neuroendocrine carcinoma lineages in the transgenic adenocarcinoma of mouse prostate model of prostate cancer. Am J Pathol. 2008;172:236–246. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Suttie AW, et al. An investigation of the effects of late-onset dietary restriction on prostate cancer development in the TRAMP mouse. Toxicol Pathol. 2005;33:386–397. doi: 10.1080/01926230590930272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tani Y, Suttie A, Flake GP, Nyska A, Maronpot RR. Epithelial-stromal tumor of the seminal vesicles in the transgenic adenocarcinoma mouse prostate model. Vet Pathol. 2005;42:306–314. doi: 10.1354/vp.42-3-306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ding Z, et al. Telomerase reactivation following telomere dysfunction yields murine prostate tumors with bone metastases. Cell. 2012;148:896–907. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fukumoto S, et al. Ameloblastin is a cell adhesion molecule required for maintaining the differentiation state of ameloblasts. J Cell Biol. 2004;167:973–983. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200409077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhao ZG, et al. MicroRNA profile of tumorigenic cells during carcinogenesis of lung adenocarcinoma. J Cell Biochem. 2015;116:458–466. doi: 10.1002/jcb.24999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Grossman WJ, et al. Development of leukemia in mice transgenic for the tax gene of human T-cell leukemia virus type I. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:1057–1061. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.4.1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wheeler DL, et al. Overexpression of protein kinase C-{epsilon} in the mouse epidermis leads to a spontaneous myeloproliferative-like disease. Am J Pathol. 2005;166:117–126. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)62237-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mueller A, et al. The role of antigenic drive and tumor-infiltrating accessory cells in the pathogenesis of helicobacter-induced mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma. Am J Pathol. 2005;167:797–812. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62052-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cardiff RD, et al. Precancer in mice: animal models used to understand, prevent, and treat human precancers. Toxicol Pathol. 2006;34:699–707. doi: 10.1080/01926230600930129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cesta MF, et al. The National Toxicology Program Web-based non-neoplastic lesion atlas: a global toxicology and pathology resource. Toxicol Pathol. 2014;42:458–460. doi: 10.1177/0192623313517304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mann PC, et al. International harmonization of toxicologic pathology nomenclature: an overview and review of basic principles. Toxicol Pathol. 2012;40:7S–13S. doi: 10.1177/0192623312438738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mohr U. International Classification of Rodent Tumors: The Mouse. Springer; Berlin: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nolte T, et al. Nonproliferative and Proliferative Lesions of the Gastrointestinal Tract, Pancreas and Salivary Glands of the Rat and Mouse. J Toxicol Pathol. 2016;29:1S–125S. doi: 10.1293/tox.29.1S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jones TC, Dungworth DL, Mohr U. Respiratory System. Springer-Verlag; Berlin: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Maronpot RR. Pathology of the Mouse. Cache River Press; Vienna, Illinois: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mohr U, Dungworth DL, Capen CC, Carlton WW, Sundberg JP, Ward JM. Pathobiology of the Aging mouse. ILSI Press; Washington DC: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ward JM, Mahler JF, Maronpot RR, Sundberg JP, editors. Pathology of Genetically Engineered Mice. Iowa State University Press; Ames, Iowa: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Schofield PN, Sundberg JP, Sundberg BA, McKerlie C, Gkoutos GV. The mouse pathology ontology, MPATH; structure and applications. J Biomed Semantics. 2013;4:18. doi: 10.1186/2041-1480-4-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fisher HM, et al. DermO; an ontology for the description of dermatologic disease. J Biomed Semantics. 2016;7:38. doi: 10.1186/s13326-016-0085-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wilkinson MD,DM, et al. The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Sci Data. 2016 doi: 10.1038/sdata.2016.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wolf JC, Maack G. Evaluating the credibility of histopathology data in environmental endocrine toxicity studies. Environ Toxicol Chem. 2017;36:601–611. doi: 10.1002/etc.3695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]