Abstract

We do not all grow older in the same way. Some individuals have a cognitive decline earlier and faster than others who are older in years but cerebrally younger. This is particularly easy to verify in people who have maintained regular physical activity and healthy and cognitively stimulating lifestyle and even in the clinical field. There are patients with advanced neurodegeneration, such as Alzheimer's disease (AD), that, despite this, have mild cognitive impairment. What determines this interindividual difference? Certainly, it cannot be the result of only genetic factors. We are made in a certain manner and what we do acts on our brain. In fact, our genetic basis can be modulated, modified, and changed by our experiences such as education and life events; daily, by sleep schedules and habits; or also by dietary elements. And this can be seen as true even if our experiences are indirectly driven by our genetic basis. In this paper, we will review some current scientific research on how our experiences are able to modulate the structural organization of the brain and how a healthy lifestyle (regular physical activity, correct sleep hygiene, and healthy diet) appears to positively affect cognitive reserve.

1. Introduction

Numerous clinical and experimental studies demonstrated that many environmental factors may affect both the physiological functions of the central nervous system (CNS) and its ability to counteract pathological changes. It has been demonstrated that experience shapes our neural circuits, making them more functional, keeping them “young.” Experience is then the factor which induces our brain to be more plastic. In other words, experience may increase neuroplasticity. The complex of molecular and cellular processes known as neuroplasticity represents the biological basis of the so called “cerebral reserves.” The first to introduce the concept of “reserve” was Yaakov Stern who noticed a higher prevalence of Alzheimer's disease (AD) in people with lower education. For Stern, the reserve is a mechanism, which may explain how, in the face of neurodegenerative changes that are similar in nature and extent, individuals vary considerably in the severity of cognitive aging and clinical dementia [1]. Clinical studies provide evidence that people with a high level of education have a slower cognitive decline [2, 3].

According to Stern, two types of cerebral reserves are recognized: brain reserve (BR) and cognitive reserve (CR). BR is based on the protective potential of anatomical features such as brain size, neuronal density, and synaptic connectivity. This reserve is passive and is also defined as the amount of brain damage that can be sustained before reaching a threshold for clinical expression [1]. It also explains differential susceptibility to functional impairment in the presence of pathology or neurological insult [4]. This concept arose by the observation that the prevalence of dementia is lower in individuals with larger brains [5–7]. In contrast, CR posits the differences in cognitive processes as a function of lifetime intellectual activities and other environmental factors that explain the nonlinear relationship between the severity of patients' brain damage and the correspondent clinical symptoms. The CR suggests that the brain actively copes with brain damage by using the preexisting cognitive processes or by enlisting compensatory mechanisms [1, 3]. Thus, CR represents a functional reserve because it is based on the efficiency of neural circuits [8]. CR is considered an “active reserve” because the brain dynamically attempts to cope with brain damage by using preexisting cognitive processing networks or by enlisting compensatory networks [1, 3]. It is important to emphasize that BR and CR are not mutually exclusive but are involved together, at different levels, in providing protection against brain damage [9]. For this reason, it is possible to refer to the accumulated structural reserve (BR) and capacity for functional compensation (CR) using the new construct of “brain and cognitive reserve” (BCR) [10]. In fact, any morphological change results in a modification of the functional properties of a circuit and vice versa, and any change in neuronal efficiency and functionality is based on morphological modifications. For example, factors associated with an increased CR, such as cognitively stimulating experiences or a great deal of physical activity, are associated with neurogenesis, increased levels of neurotrophic factors, and diminution of neuronal apoptosis [11]. Therefore, functional and anatomical factors interact in the construction of the cerebral reserves [12].

In clinical research, we can study the relation between structural (BR) and functional (CR) changes by analyzing the gray matter damage in AD patients (structural measure) and then correlating it with a cognitive evaluation (functional measure) [13].

More direct measures of experience-due structural and functional changes are provided by experimental research on animal models. For example, BR measures are the changes at cellular and molecular levels [14], while direct CR measures are the performances in behavioral tasks, such as spatial tasks [8, 15]. The studies carried out by using enriched environment animal models enabled us to understand what kinds of experiences are necessary to trigger the phenomenon of brain plasticity and thus to increase cerebral reserves.

The purpose of the present work is to provide an up-to-date overview on the effects of the environmental factors on promoting neural plasticity in physiological and pathological conditions taking into account both human and animal studies.

2. Animal Studies

There is evidence showing that individuals with more CR are those who have a high level of education, who maintain regular physical activity, and who eat in a healthy way [16–19]. Despite such evidence, human studies do not allow us to determine whether one kind of experience determines the increase in cognitive reserve more than the other ones. Human research cannot separate the different variables that make up experience because we cannot analyze them separately. The experimental research on animals may compensate for these shortcomings by forcing the stimulation of a specific experience or a combination of experiences, as occurs in enriched environment animal models. The animal models of environmental enrichment (EE) allow us to obtain a direct, real, and tangible measure of which environmental factors are able to model neuronal circuits [8].

EE represents an experimental model in which the animal is exposed for a certain time period to a combination of experiences, such as an intense motor activity and sustained cognitive stimulation. This condition is usually compared to the standard condition of regular laboratory housing [20].

The majority of EE animal models concern rodents, but studies have also been carried out on nonhuman primates, birds, and fish [21].

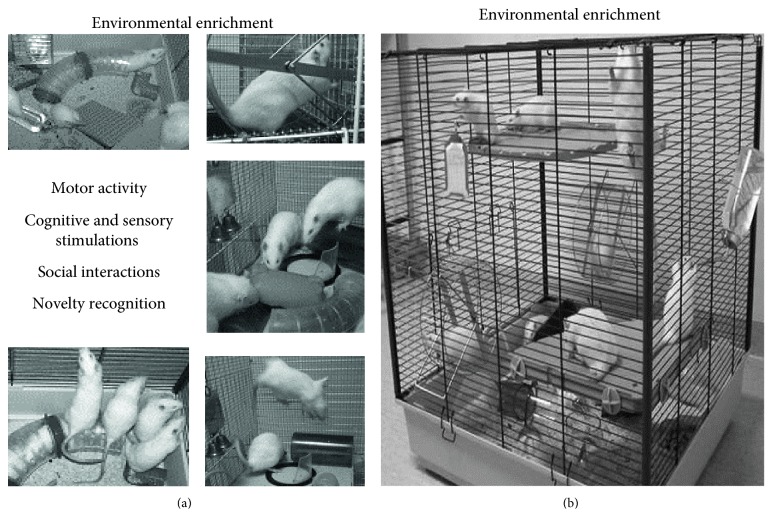

At the first glance, it may seem strange that the EE in animals may be really compared to cognitive, motor, social, and emotional experiences in humans. Although this correlation may seem impossible, exposure of animals to an enriched environment is actually similar to that which occurs in human lifestyle [8]. In fact, in humans, the development of reserves can be influenced by several factors, such as educational level, physical activity, social integration, and emotional involvement. In animal models, all these factors are provided by the environmental complexity and novelty the animals are exposed to. The repeated replacing of objects in the home cages creates a wide range of opportunities for enhanced cognitive stimulation, formation of efficient spatial maps, and heightened ability to detect novelty. Physical training is represented by foraging in large cages, exploration of new objects that are constantly introduced into the cages, and general motor activity related to the use of wheels. The social aspect that characterizes human relationships may be mimicked by rearing the animals in a group of conspecifics. In fact, if the animals are stimulated to live together in the same cage, a social hierarchy emerges and a dominant figure arranges and controls the spaces of the cage and when to eat. Figure 1 shows an example of the rearing in an enriched environment.

Figure 1.

A typical enriched setting that enhances motor, sensory, cognitive, and social stimulations in rodents is illustrated in (b). In (a), the different components acting in the environmental enrichment are shown. Modified from [8].

The first to introduce the experimental concept of enriched environment was Donald Hebb, although it was the famous American psychologist Mark Richard Rosenzweig who clarified the enriched environment as “a combination of complex inanimate and social stimulations” [22].

Thus, the implementation of a setting of EE is a quite complex procedure, in which motor activity, cognitive abilities, and social interaction should be taken into account. Although recently it has been shown that also physical activity alone is able to increase CR, most studies show that all these factors should be stimulated to increase brain plasticity [8].

An EE paradigm is used with healthy animals to analyze neuroplastic functional and structural changes [23], with animals that present neurodegenerative lesions or transgenic mutations to analyze neuroprotective and therapeutic effects [10, 15, 24–27], and recently even with an animal model of psychiatric disorders, such as schizophrenia, to evaluate the ameliorative effects on behavioral symptoms [28–30].

In general, cognitive abilities in animals are evaluated by means of specific behavioral tasks such as Morris water maze (MWM) and radial arm maze (RAM) that analyze the different facets of spatial memory. In fact, the memory can be divided into at least two types, such as declarative and procedural. Declarative knowledge refers to things that we know that are accessible to conscious recollection (“knowing that”), while procedural material regards memories on how to do something (“knowing how”) and those that are seen as implicit and unconsciously learned [31]. The two types of memory have different and specific neural correlates. Declarative memory mainly involves the hippocampal structures, while procedural learning and memory rely more on the cerebellum and basal ganglia [32–34]. Majority results discussed in the next sessions come from MWM and RAM behavioral tasks.

2.1. Functional and Structural Effects of EE

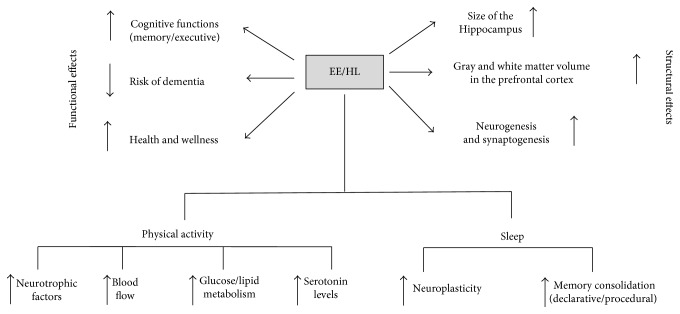

Many studies conducted on healthy animals show that rearing in an enriched environment has significant functional and structural effects (Table 1, Figure 2).

Table 1.

Structural and functional effects of environmental enrichment (EE).

| Sample | EE condition | Functional Effects (behavioral effects) | Structural Effects (molecular and cellular effects) | Refs. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effects of EE on healthy rodents | |||||

| Wistar rats | EE from weaning for 2.5/3 months | Precocious development of spatial cognitive map; enhanced spatial memory and cognitive flexibility | Increases dendritic length and spine density in frontal and parietal pyramidal neuron apical and basal arborizations; synaptogenesis; increases of BDNF levels in the hippocampus and cerebellum | [14, 23, 35–37, 40] | |

| Wistar rats C57BL/6J mice |

Maternal and paternal EE: a transgenerational model | In pups: accelerated acquisition of complex motor behaviors; decreased anxiety-related behaviors | In pups: high expression of neurotrophin in cerebellar and striatal areas; low ACTH levels | [38–41] | |

|

| |||||

| Neuroprotective effects of EE on neurodegeneration | |||||

| Neurodegenerative disorders | HD mouse models | Running exercise about from 4 weeks of age | Partially delayed onset of motor symptoms and cognitive deficits (memory/executive functions) | Altered BDNF mRNA levels | [10, 15, 42–45] |

| EE about from 4 weeks of age | Delayed onset of motor symptoms and cognitive deficits (memory/executive functions) | Decreased cortical and striatal volume loss; ameliorated deficit in neurogenesis; increased neurotrophin expression; enhanced CB1 receptor levels | |||

| PD mouse models | Running exercise from 6 weeks | Attenuated motor impairment, reduced anxiety behavior | Decreased loss of striatal DA | [10, 15, 46–49] | |

| AD mouse/rat models | Intensive locomotor training | Increases performances in spatial memory tasks | Decreased beta-amyloid plaques | [10, 15, 24–27, 50–57, 62] | |

| EE from weaning for 2.5/3 months; EE for 2 months at different age | Enhanced spatial memory and executive functions (cognitive flexibility) | Decreased beta-amyloid plaques; increased levels of neurotrophic substances; increased spine number and density in pyramidal neurons | |||

| Aging | EE and locomotor training in middle age | Preservation of spatial abilities in old age | Changes in hippocampal astrocytes; hippocampal neurogenesis | [58–61] | |

EE refers to a complex stimulation of experiences. BDNF: brain-derived neurotrophic factor; NGF: nerve growth factor; ACTH: adrenocorticotropic hormone; HD: huntington's disease; PD: parkinson's disease; AD: alzheimer's disease; DA: dopamine.

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the structural and functional effects of environmental enrichment (EE) on animal models and healthy lifestyle (HL) on humans.

To evaluate the functional effects of EE on the performances in behavioral tasks, spatial tasks are analyzed. In particular, these tasks permit us to analyze the different facets of spatial cognitive function and then to evaluate the functioning of underlying neural circuits. For example, Leggio and coworkers compared the spatial performances in radial arm maze and in Morris water maze of healthy animals reared in an enriched environment for three months after the weaning with those of animals reared in standard conditions [23]. In both spatial tasks, the animals reared in an enriched environment made fewer errors than the conspecifics reared in standard laboratory conditions and showed a precocious development of spatial cognitive mapping of the environment.

In EE structural effects, the changes at cellular level (such as neurogenesis, gliogenesis, angiogenesis, and synaptogenesis) and the alterations at molecular level (such as changes in neurotransmitter and neurotrophin expression) are considered [15]. By studying synaptogenesis, Gelfo and coworkers evidenced as indices of improved neuronal circuitry the increased dendritic length and spine density shown by the frontal and parietal pyramidal neuron apical and basal arborizations of rats reared in EE [35]. Molecular effects that follow EE have been demonstrated by analyzing the neurotrophin levels in brain structures where neurotrophins are produced or transported. In particular, multiple studies in rodent models showed that EE increases the expression of a brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in the hippocampus that heavily supports the EE-induced improvement in learning and memory [36, 37]. Moreover, neurotrophin levels were found to be also increased in the cerebellum and other cerebral areas following EE [14].

Functional and structural effects of EE are analyzed even from a transgenerational point of view. In particular, Caporali and coworkers [38] reared female rats in enriched conditions and then studied the motor behavior and the neurotrophin levels of their pups reared in standard conditions. This study demonstrates that positive maternal experiences were transgenerationally transmitted and influenced offspring phenotype at both behavioral and biochemical levels. In fact, the pups from enriched mothers acquired complex motor behaviors earlier than the pups from mothers reared in standard conditions. Moreover, in the pups from enriched mothers, the cerebellar and striatal neurotrophin expression was significantly higher. Evidence presents that also paternal EE is able to transgenerationally alter affective behavioral and neuroendocrine phenotypes of the offspring [39–41]. These studies suggest that the cerebral reserves could be even inherited.

2.2. Neuroprotective Effects of EE

As we mentioned, many studies showed that EE or even just motor exercise induces neuroprotection against neurodegenerative diseases [15, 24–26]. In a brilliant review on the EE models, Nithianantharajah and Hannan showed that motor exercise alone produces a positive effect at behavioral, cellular, and molecular levels on some diseases that affect the cognitive-motor sphere, such as Huntington's disease (HD), Parkinson's disease (PD), and AD [15]. To give some examples, in HD mouse models, it was demonstrated that wheel-running exercise delays the onset of specific motor deficits [42–44] and diminished the impairment in spatial memory and cognitive flexibility, also attenuating neuropathology [45]. Behavioral performance has been demonstrated to be improved by physical training also in PD rodent models [46, 47], with neuroprotective effects on the regulation of neurochemical factors [48, 49]. Finally, in AD, an intensive locomotor training increases the quality of performance in behavioral tasks concerning spatial learning and memory [50]. At cellular level, a decrease in beta-amyloid plaques occurs and, only in the case of more complex stimulation, an increase in the levels of neurotrophic substances as synaptophysin was also observed [51–53].

Examples coming from transgenic murine models, which provide the precious advantage to determine exactly when a structural alteration occurs, allow to evaluate when it is best to enrich the animals. For example, by means of transgenic AD mice (Tg2576), Verret and coworkers showed that the EE effects are more powerful if the animals are reared in an enriched environment before the formation of beta-amyloid plaques [54], that is, before their deleterious effects on brain function and memory processing become permanent.

Decreased levels of beta-amyloid plaque in response to EE have been highlighted also by Beauquis and coworkers who analyzed the astroglial changes in the hippocampus of transgenic animals [55]. In fact, growing evidence shows that glial changes may precede neuronal alterations and behavioral impairment in the progression of AD and that the modulation of these changes could be addressed as a potential therapeutic strategy [56–58]. In particular, Beauquis and coworkers evidenced that in enriched transgenic animals (APP mice), a decrement in levels of astrocytes was present, suggesting that glial alterations have an early onset in AD pathogenesis and the exposure to an enriched environment is an appropriate strategy to reverse them.

Moreover, the confirmation that glial alterations play an important role in cerebral reserves comes from a recent study that investigated the functional and structural effects of intermittent EE (3 hours/day for two months) on aged rats [58]. In fact, even at advanced ages, behavioral results showed that EE improved performances in a radial water maze task and structural data evidenced plastic changes in the hippocampal astrocytes suggesting that these neuroplastic alterations are involved in a coping mechanism with age-related cognitive impairment.

Several authors wondered until which point in life the enrichment has positive effects on cognitive function. Fuchs and coworkers assessed the impact of late housing condition (e.g., from the age of 18 months) on spatial learning and memory of aged rats (24 months) previously exposed or unexposed to EE during young adulthood (until 18 months) [59]. The results showed that late EE was not required for spatial memory maintenance in aged rats previously housed in EE. In contrast, late EE mitigates spatial memory deficit in aged rats previously unexposed to EE. These outcomes suggest that EE exposure up to middle age provides a reserve-like advantage that supports an enduring preservation of spatial capabilities in old age [60, 61].

In addition to the transgenic animal models of EE, also the studies on lesioned animals contributed to highlighting the neuroprotective role of environmental stimulation. For example, it was found that rats exposed to EE at weaning about three months before a cholinergic basal forebrain depletion (which mimics AD) recover some cognitive abilities such as spatial memory and cognitive flexibility [62]. These improvements in the cognitive-motor domain were also accompanied by changes at the morphological level [26], demonstrating once again the close link between structure and function and, in this case, between CR and BR.

The main neuroprotective effects of EE are shown in Table 1.

3. Environmental Factors and Lifestyle in Human

Research on animal models provides an important insight into understanding the key role of environmental factors in promoting cognitive reserve. On the other hand, human studies showed that not only high-demand cognitive activities are able to improve cognitive skills and counteract a physiological and pathological cognitive decline but even other environmental factors such as regular physical activity and correct sleep hygiene can substantially contribute to brain well-being.

3.1. Physical Activity (PA) and Neuroplasticity

In EE animal models, it has been shown that motor exercise has significant effects on neuroplasticity and counteracts a pathological cognitive decline [10, 15]. In humans, it seems necessary to distinguish between physical activity (PA) and physical exercise (PE). In fact, PA is any movement of the body produced by skeletal muscles that results in energy expenditure over the baseline levels, including all structured daily activities, such as housework and leisure activities. Conversely, PE is a structured and repetitive physical activity, aimed at maintaining or improving one or more components of physical fitness.

PA and PE are often related to health benefits in the prevention and in the treatment of many pathological conditions, such as metabolic diseases [63–65] as well as diseases associated with compromised cognition and brain function [66]. Several studies do exist showing that the practice of regular and constant PA reduces the risk of developing dementia [67].

PA increases blood flow, improves cerebrovascular health, and determines benefits of glucose and lipid metabolism carrying “food” to the brain. It has been showed that PA causes neural plasticity phenomena. For example, PA facilitates the release of neurotrophic factors like BDNF, stimulates neurogenesis phenomena, and determines structural changes such as the improvement of white matter integrity [68]. The brain changes are inevitably reflected in functional modifications. In this context, children with higher levels of aerobic fitness showed greater brain volumes in gray matter brain regions (structural changes) and the best performances in learning and memory tasks (functional changes) in comparison to sedentary children [69]. It is important to underlie that all the structural and functional changes are derived by an aerobic type of PA. Recently, it has been showed that only regular aerobic exercise is associated with larger size of the hippocampal regions [70]. Moreover, aerobic exercise increases gray and white matter volume in the prefrontal cortex [71] and increases the functioning of key nodes in the executive control network [72, 73] (Figure 2).

3.2. Sleep and Neuroplasticity

In the last decades, it has been shown that sleep is an essential feature of animal and human brain plasticity, which involves both basic (e.g., [74]) and higher-order functions (e.g., [75]).

Sleep is an active, repetitive, and reversible behavior that is in the service of several different functions that occur all over the brain and the body [76, 77]: from repair and growth to learning or memory consolidation and up to restorative processes. This basic role of sleep is also indirectly substantiated by the fact that almost all the animal species, from fruit flies to the biggest mammals [78], share a behavioral state that can be defined as “sleeplike.” Thus, if sleep subserves all these aspects of animal life, it would be seen as a crucial survival-directed drive, so that chronic or repeated sleep deprivation in rodents brings cellular and molecular changes in the brain [79] while in humans, it can dramatically disrupt several high-order cognitive functions [75, 80–83].

Different hypotheses have been suggested to deeply explain the functions of sleep, and one of the well-accepted ideas is that sleep is linked to memory, learning, and neuroplasticity mechanisms [74] (Figure 2).

Several studies showed that sleep plays an important role in learning processes and memory consolidation [84, 85] although no direct relationships have been found between different kinds of memory and different sleep stages [86]. These studies clearly indicated that sleep deprivation can impair learning and different kinds of memory that can be divided into at least two types, such as declarative and procedural (as discussed above). Thanks to this distinction, a dual-process hypothesis has been proposed [87]: the effect of a sleep state on memory processes would be task-dependent, with the procedural memory gaining from REM (rapid eye movement) sleep and declarative memory from NREM (nonrapid eye movement) sleep [88].

But other data [89] have been interpreted as in line with the alternative point of view, that is, the hypothesis of a sequential processing of memories during sleep stages [90, 91] suggesting that memory formation would be prompted by NREM sleep (and particularly by its slow-wave content, namely, stages 3 and 4) and then consolidated by REM sleep, indicating that for an efficient consolidation of both knowledge (declarative) and skills (procedural), the worst enemy is sleep loss or, at least, sleep fragmentation.

The nature of the link between sleep and synaptic plasticity is not fully understood: several different processes of synaptic reorganization would occur during sleep period, but their functional role needs to be clarified. In a very recent review [74], it has been discussed that induction of plastic changes during wake can produce coherent and topographically specific local changes in EEG slow activity in the subsequent sleep and that during sleep, synaptic plasticity would be restored.

Independently by the actual nature of the link between sleep and neuroplasticity, now, it is well known and accepted that a good quality of sleep allows an efficient and successful aging [92]. In fact, several recent studies have clearly indicated the relevance of sleep quantity and quality as a marker of general health, well-being, and adaptability in later life [93–95]. This literature can help in developing health programs devoted to the oldest aim of improving sleep hygiene in order to guarantee avoidance of disease, maintenance of high cognitive and physical function, and continued engagement with life.

4. Conclusions

Experimental research strongly suggests that in order to increase our cerebral reserves, we have to follow a lifestyle that takes into account many factors. Clinical studies provided evidence that individuals with more cerebral reserves are those who have a high level of education, who maintain regular physical activity, who eat in a healthy way, and so on. The EE animal models confirmed that the experience plays a key role in increasing brain plasticity phenomena. Although we are still far from identifying the basic ingredient responsible for increasing our brain plasticity and for counteracting neurodegenerative damage, we can say with confidence that to deal with physiological and pathological situations, it is not only important to be “genetically lucky” but also to maintain a lifestyle rich in experiences also including high levels of physical activity and good sleep hygiene.

Acknowledgment

The work was supported by the University of Naples Parthenope “Ricerca locale” (Giuseppe Sorrentino and Laura Mandolesi) and “Ricerca Competitiva” (Laura Mandolesi).

Ethical Approval

This article is based on the review of previous papers, and thus, it does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Stern Y. What is cognitive reserve? Theory and research application of the reserve concept. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2002;8:448–460. doi: 10.1017/S1355617702813248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bozzali M., Dowling C., Serra L., et al. The impact of cognitive reserve on brain functional connectivity in Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 2015;44:243–250. doi: 10.3233/JAD-141824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stern Y. Cognitive reserve. Neuropsychologia. 2009;47:2015–2028. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2009.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stern Y. Cognitive reserve in ageing and Alzheimer’s disease. The Lancet Neurology. 2012;11:1006–1012. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70191-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Katzman R., Terry R., DeTeresa R., et al. Clinical, pathological, and neurochemical changes in dementia: a subgroup with preserved mental status and numerous neocortical plaques. Annals of Neurology. 1988;23:138–144. doi: 10.1002/ana.410230206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mortimer J. A., Borenstein A. R., Gosche K. M., Snowdon D. A. Very early detection of Alzheimer neuropathology and the role of brain reserve in modifying its clinical expression. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology. 2005;18:218–223. doi: 10.1177/0891988705281869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schofield P. W., Logroscino G., Andrews H. F., Albert S., Stern Y. An association between head circumference and Alzheimer’s disease in a population-based study of aging and dementia. Neurology. 1997;49:30–33. doi: 10.1212/WNL.49.1.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Petrosini L., De Bartolo P., Foti F., et al. On whether the environmental enrichment may provide cognitive and brain reserves. Brain Research Reviews. 2009;61:221–239. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stern Y. Cognitive reserve and Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders. 2006;20:112–117. doi: 10.1097/01.wad.0000213815.20177.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nithianantharajah J., Hannan A. J. Mechanisms mediating brain and cognitive reserve: experience dependent neuroprotection and functional compensation in animal models of neurodegenerative diseases. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry. 2011;35:331–339. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2010.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van Praag H., Kempermann G., Gage G. H. Neural consequences of environmental enrichment. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2000;1:191–198. doi: 10.1038/35044558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Petrosini L., Mandolesi L., Laricchiuta D. Le riserve cerebrali. In: Serra L., Caltagirone C., editors. La malattia di Alzheimer: highlights clinici e sperimentali. Roma, Italia: Critical Medicine Publishing; 2010. pp. 209–218. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Serra L., Cercignani M., Petrosini L., et al. Neuroanatomical correlates of cognitive reserve in Alzheimer disease. Rejuvenation Research. 2011;14:143–151. doi: 10.1089/rej.2010.1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Angelucci F., De Bartolo P., Gelfo F., et al. Increased concentrations of nerve growth factor and brain-derived neurotrophic factor in the rat cerebellum after exposure to environmental enrichment. The Cerebellum. 2009;8:499–506. doi: 10.1007/s12311-009-0129-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nithianantharajah J., Hannan A. J. Enriched environments, experience-dependent plasticity and disorders of the nervous system. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2006;7:697–709. doi: 10.1038/nrn1970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Borenstein A. R., Copenhaver C. I., Mortimer J. A. Early-life risk factors for Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders. 2006;20:63–72. doi: 10.1097/01.wad.0000201854.62116.d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Horr T., Messinger-Rapport B., Pillai J. A. Systematic review of strengths and limitations of randomized controlled trials for non-pharmacological interventions in mild cognitive impairment: focus on Alzheimer’s disease. The Journal of Nutrition, Health and Aging. 2015;19:141–153. doi: 10.1007/s12603-014-0565-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McDowell I., Xi G., Lindsay J., Tierney M. Mapping the connections between education and dementia. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 2007;29:127–141. doi: 10.1080/13803390600582420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roe C. M., Xiong C., Miller J. P., Morris J. C. Education and Alzheimer disease without dementia: support for the cognitive reserve. Neurology. 2007;68:223–228. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000251303.50459.8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kempermann G., Fabel K., Ehninger D., et al. Why and how physical activity promotes experience-induced brain plasticity. Frontiers in Neuroscience. 2010;4:p. 189. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2010.00189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Foti F., De Bartolo P., Petrosini L. Ruolo dei fattori ambientali in presenza di neurodegenerazione. In: Serra L., Caltagirone C., editors. La malattia di Alzheimer: highlights clinici e sperimentali. Roma, Italia: Critical Medicine Publishing; 2010. pp. 209–218. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosenzweig M. R., Bennett E. L. Psychobiology of plasticity: effects of training and experience on brain and behavior. Behavioural Brain Research. 1996;78:57–65. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(95)00216-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leggio M. G., Mandolesi L., Federico F., et al. Environmental enrichment promotes improved spatial abilities and enhanced dendritic growth in the rat. Behavioural Brain Research. 2005;163:78–90. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2005.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jankowsky J. L., Melnikova T., Fadale D. J., et al. Environmental enrichment mitigates cognitive deficits in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Neuroscience. 2005;25:5217–5224. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5080-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lazarov O., Robinson J., Tang Y. P., et al. Environmental enrichment reduces Aβ levels and amyloid deposition in transgenic mice. Cell. 2005;120:701–713. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mandolesi L., De Bartolo P., Foti F., et al. Environmental enrichment provides a cognitive reserve to be spent in the case of brain lesion. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 2008;15:11–28. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2008-15102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Puzzo D., Gulisano W., Palmeri A., Arancio O. Rodent models for Alzheimer’s disease drug discovery. Expert Opinion on Drug Discovery. 2015;10:703–711. doi: 10.1517/17460441.2015.1041913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tang Y. P., Wang H., Feng R., Kyin M., Tsien J. Z. Differential effects of enrichment on learning and memory function in NR2B transgenic mice. Neuropharmacology. 2001;41:779–790. doi: 10.1016/S0028-3908(01)00122-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brenes J. C., Rodriguez O., Fornaguera J. Differential effect of environment enrichment and social isolation on depressive-like behavior, spontaneous activity and serotonin and norepinephrine concentration in prefrontal cortex and ventral striatum. Pharmacology Biochemistry Behavior. 2008;89:85–93. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burrows E. L., McOmish C. E., Buret L. S., Van den Buuse M., Hannan A. J. Environmental enrichment ameliorates behavioral impairments modeling schizophrenia in mice lacking metabotropic glutamate receptor 5. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2015;40:1947–1956. doi: 10.1038/npp.2015.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Squire L. R., Zola-Morgan S. The medial temporal lobe memory system. Science. 1991;253:1380–1386. doi: 10.1126/science.1896849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eichenbaum H., Cohen N. J. From Conditioning to Conscious Recollection: Memory Systems of the Brain. New York, USA: Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leggio M. G., Neri P., Graziano A., Mandolesi L., Molinari M., Petrosini L. Cerebellar contribution to spatial event processing: characterization of procedural learning. Experimental Brain Research. 1999;127:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s002210050768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ragozzino M. E., Ragazzino K. E., Mizumori S. J. Y., Kesner R. P. Role of the dorsomedial striatum in behavioral flexibility for response and visual cue discrimination learning. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2002;116:105–115. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.116.1.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gelfo F., Bartolo P., Giovine A., Petrosini L., Leggio M. G. Layer and regional effects of environmental enrichment on the pyramidal neuron morphology of the rat. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 2009;91:353–365. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2009.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Falkenberg T., Mohammed A. K., Henriksson B., Persson H., Winblad B., Lindefors N. Increased expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor mRNA in rat hippocampus is associated with improved spatial memory and enriched environment. Neuroscience Letters. 1992;138(1):153–156. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(92)90494-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meng F. T., Zhao J., Ni R. J., et al. Beneficial effects of enriched environment on behaviors were correlated with decreased estrogen and increased BDNF in the hippocampus of male mice. Neuroendocrinology Letters. 2015;36(5):490–497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Caporali P., Cutuli D., Gelfo F., et al. Prereproductive maternal enrichment influences offspring developmental trajectories: motor behavior and neurotrophin expression. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience. 2014;8:p. 195. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yeshurun S., Short A. K., Bredy T. W., Pang T. Y., Hannan A. J. Paternal environmental enrichment transgenerationally alters affective behavioural and neuroendocrine phenotypes. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2017;77:225–235. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2016.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Voss M. W., Vivar C., Kramer A. F., van Praag H. Bridging animal and human models of exercise-induced brain plasticity. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2013;17:525–544. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2013.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Short A. K., Yeshurun S., Powell R., et al. Exercise alters mouse sperm small noncoding RNAs and induces a transgenerational modification of male offspring conditioned fear and anxiety. Translational Psychiatry. 2017;7(5, article e1114) doi: 10.1038/tp.2017.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.van Dellen A., Blakemore C., Deacon R., York D., Hannan A. J. Delaying the onset of Huntington’s in mice. Nature. 2000;404(6779):721–722. doi: 10.1038/35008142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van Dellen A., Cordery P. M., Spires T. L., Blakemore C., Hannan A. J. Wheel running from a juvenile age delays onset of specific motor deficits but does not alter protein aggregate density in a mouse model of Huntington’s disease. BMC Neuroscience. 2008;9:p. 34. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-9-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pang T. Y., Stam N. C., Nithianantharajah J., Howard M. L., Hannan A. J. Differential effects of voluntary physical exercise on behavioral and brain-derived neurotrophic factor expression deficits in Huntington’s disease transgenic mice. Neuroscience. 2006;141(2):569–584. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Harrison D. J., Busse M., Openshaw R., Rosser A. E., Dunnett S. B., Brooks S. P. Exercise attenuates neuropathology and has greater benefit on cognitive than motor deficits in the R6/1 Huntington’s disease mouse model. Experimental Neurology. 2013;248:457–469. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2013.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Faherty C. J., Raviie Shepherd K., Herasimtschuk A., Smeyne R. J. 2005 “environmental enrichment in adulthood eliminates neuronal death in experimental parkinsonism”. Brain Research Molecular Brain Research. 2005;134:170–1799. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2004.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jadavji N. M., Kolb B., Metz G. A. Enriched environment improves motor function in intact and unilateral dopamine-depleted rats. Neuroscience. 2006;140:1127–1138. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gorton L. M., Vuckovic M. G., Vertelkina N., Petzinger G. M., Jakowec M. W., Wood R. I. Exercise effects on motor and affective behavior and catecholamine neurochemistry in the MPTP-lesioned mouse. Behavioural Brain Research. 2010;213(2):253–262. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tuon T., Valvassori S. S., Lopes-Borges J., et al. Physical training exerts neuroprotective effects in the regulation of neurochemical factors in an animal model of Parkinson’s disease. Neuroscience. 2012;227:305–312. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.09.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Arendash G. W., Garcia M. F., Costa D. A., Cracchiolo J. R., Wefes I. M., Potter H. Environmental enrichment improves cognition in aged Alzheimer’s transgenic mice despite stable beta-amyloid deposition. Neuroreport. 2004;15:1751–1754. doi: 10.1097/01.wnr.0000137183.68847.4e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Adlard P. A., Perreau V. M., Pop V., Cotman C. W. Voluntary exercise decreases amyloid load in a transgenic model of Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Neuroscience. 2005;25:4217–4221. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0496-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Levi O., Jongen-Relo A. L., Feldon J., Roses A. D., Michaelson D. M. ApoE4 impairs hippocampal plasticity isoform-specifically and blocks the environmental stimulation of synaptogenesis and memory. Neurobiology of Disease. 2003;13:273–282. doi: 10.1016/S0969-9961(03)00045-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lista I., Sorrentino G. Biological mechanisms of physical activity in preventing cognitive decline. Cellular and Molecular Neurobiology. 2010;30:493–503. doi: 10.1007/s10571-009-9488-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Verret L., Krezymona A., Halleya H., et al. Transient enriched housing before amyloidosis onset sustains cognitive improvement in Tg2576 mice. Neurobiology of Aging. 2013;34:211–225. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2012.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Beauquis J., Pavía P., Pomilio C., et al. Environmental enrichment prevents astroglial pathological changes in the hippocampus of APP transgenic mice, model of Alzheimer’s disease. Experimental Neurology. 2013;239:28–37. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2012.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Viola G. G., Rodrigues L., Américo J. C., et al. Morphological changes in hippocampal astrocytes induced by environmental enrichment in mice. Brain Research. 2009;1274:47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Webster B., Hansen L., Adame A., et al. Astroglial activation of extracellular-regulated kinase in early stages of Alzheimer disease. Journal of Neuropathology & Experimental Neurology. 2006;65:142–151. doi: 10.1097/01.jnen.0000199599.63204.6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sampedro-Piquero P., De Bartolo P., Petrosini L., Zancada-Menendez C., Arias J. L., Begega A. Astrocytic plasticity as a possible mediator of the cognitive improvements after environmental enrichment in aged rats. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 2014;114:16–25. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2014.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fuchs F., Cosquer B., Penazzi L., et al. Exposure to an enriched environment up to middle age allows preservation of spatial memory capabilities in old age. Behavioural Brain Research. 2016;299:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2015.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cummins R. A., Walsh R. N., Budtz-Olsen O. E., Konstantinos T., Horsfall C. R. Environmentally-induced changes in the brains of elderly rats. Nature. 1973;243:516–518. doi: 10.1038/243516a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kobayashi S., Ohashi Y., Ando S. Effects of enriched environments with different durations and starting times on learning capacity during aging in rats assessed by a refined procedure of the Hebb-Williams maze task. Journal of Neuroscience Research. 2002;70:340–346. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.De Bartolo P., Leggio M. G., Mandolesi L., et al. Environmental enrichment mitigates the effects of basal forebrain lesions on cognitive flexibility. Neuroscience. 2008;54:444–453. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.03.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.LeBrasseur N. K., Walsh K., Arany Z. Metabolic benefits of resistance training and fast glycolytic skeletal muscle. American Journal of Physiology: Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2011;300(1):E3–E10. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00512.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Marwick T. H., Hordern M. D., Miller T., et al. Exercise training for type 2 diabetes mellitus: impact on cardiovascular risk: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2009;119:3244–3262. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Valerio G., Spagnuolo M. I., Lombardi F., Spadaro R., Siano M., Franzese A. Physical activity and sports participation in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Nutrition, Metabolism and Cardiovascular Diseases. 2007;17(5):376–382. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2005.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Voss M. W., Erickson K. I., Prakash R. S., et al. Neurobiological markers of exercise-related brain plasticity in older adults. Brain, Behavior and Immunity. 2013;28:90–99. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2012.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Colberg S. R., Somma C. T., Sechrist S. R. Physical activity participation may offset some of the negative impact of diabetes on cognitive function. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2008;9(6):434–438. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2008.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chaddock-Heyman L., Erickson K. I., Holtrop J. L., et al. Aerobic fitness is associated with greater white matter integrity in children. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 2014;8:p. 584. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2014.00584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Voss M. W., Chaddock L., Kim J. S., et al. Aerobic fitness is associated with greater efficiency of the network underlying cognitive control in preadolescent children. Neuroscience. 2011;199:166–176. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Erickson K. I., Prakash R. S., Voss M. W., et al. Aerobic fitness is associated with hippocampal volume in elderly humans. Hippocampus. 2009;19(10):1030–1039. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Colcombe S. J., Erickson K. I., Scalf P. E., et al. Aerobic exercise training increases brain volume in aging humans. Journals of Gerontology Series a: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2006;61(11):1166–1170. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.11.1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Colcombe S. J., Kramer A. F., Erickson K. I., et al. Cardiovascular fitness, cortical plasticity, and aging. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101(9):3316–3321. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400266101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rosano C., Venkatraman V. K., Guralnik J., et al. Psychomotor speed and functional brain MRI 2 years after completing a physical activity treatment. Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2010;65(6):639–647. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glq038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gorgoni M., D'Atri A., Lauri G., Rossini P. M., Ferlazzo F., De Gennaro L. Is sleep essential for neural plasticity in humans, and how does it affect motor and cognitive recovery? Neural Plasticity. 2013;2013:13. doi: 10.1155/2013/103949.103949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Curcio G., Ferrara M., De Gennaro L. Sleep loss, learning capacity and academic performance. Sleep Medicine Reviews. 2006;10(5):323–337. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2005.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Benington J. H. Sleep homeostasis and the function of sleep. Sleep. 2000;23:959–966. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Krueger J. M., Obal F. Sleep function. Frontiers in Bioscience. 2003;8:d511–d519. doi: 10.2741/1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cirelli C., Tononi G. Is sleep essential? PLoS Biology. 2008;6(8, article e216) doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Cirelli C. Cellular consequences of sleep deprivation in the brain. Sleep Medicine Reviews. 2006;10(5):307–321. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Durmer J. S., Dinges D. F. Neurocognitive consequences of sleep deprivation. Seminars in Neurology. 2005;25(1):117–129. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-867080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Harrison Y., Horne J. A. The impact of sleep deprivation on decision making: a review. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied. 2006;6:236–249. doi: 10.1037//1076-898x.6.3.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.McCoy J. G., Strecker R. E. The cognitive cost of sleep lost. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 2011;96(4):564–582. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2011.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Walker M. P. Cognitive consequences of sleep and sleep loss. Sleep Medicine. 2008;9(1) supplement 1:S29–S34. doi: 10.1016/S1389-9457(08)70014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hobson J. A., Pace-Schott E. F. The cognitive neuroscience of sleep: neuronal systems, counsciousness and learning. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2002;3:679–693. doi: 10.1038/nrn915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Smith C. Sleep states and memory processes in humans: procedural versus declarative memory systems. Sleep Medicine Reviews. 2001;5:491–506. doi: 10.1053/smrv.2001.0164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rauchs G., Desgranges B., Foret J., Eustache F. The relationships between memory systems and sleep stages. Journal of Sleep Research. 2005;14:123–140. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2005.00450.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Peigneux P., Laureys S., Delbeuck X., Maquet P. Sleeping brain, learning brain. The role of sleep for memory systems. Neuroreport. 2001;12:A111–A124. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200112210-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Plihal W., Born J. Effect of early and late nocturnal sleep on declarative and procedural memory. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 1997;9:534–547. doi: 10.1162/jocn.1997.9.4.534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Gais S., Plihal W., Wagner U., Born J. Early sleep triggers memory for early visual discrimination skills. Nature Neuroscience. 2000;3:1335–1339. doi: 10.1038/81881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ambrosini M. V., Giuditta A. Learning and sleep: the sequential hypothesis. Sleep Medicine Reviews. 2001;5:477–490. doi: 10.1053/smrv.2001.0180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Giuditta A., Ambrosini M. V., Montagnese P., et al. The sequential hypothesis of the function of sleep. Behavioural Brain Research. 1995;69:157–166. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(95)00012-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Driscoll H. C., Serody L., Patrick S., et al. Sleeping well, aging well: a descriptive and cross-sectional study of sleep in “successful agers” 75 and older. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2008;16(1):74–82. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181557b69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Dew M. A., Hoch C. C., Buysse D. J., et al. Healthy older adults’ sleep predicts all-cause mortality at 4 to 19 years of follow-up. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2003;65:63–73. doi: 10.1097/01.PSY.0000039756.23250.7C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Dew M. A., Reynolds C. F., Monk T. H., et al. Psychosocial correlates and sequelae of electroencephalographic sleep in healthy elders. The Journals of Gerontology. 1994;49:P8–P18. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.1.P8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Hoch C. C., Dew M. A., Reynolds C. F., et al. A longitudinal study of laboratory- and diary-based sleep measures in healthy “old old” and “young old” volunteers. Sleep. 1994;17:489–496. doi: 10.1093/sleep/17.6.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]