Abstract

The ranking of scientific journals is important because of the signal it sends to scientists about what is considered most vital for scientific progress. Existing ranking systems focus on measuring the influence of a scientific paper (citations)—these rankings do not reward journals for publishing innovative work that builds on new ideas. We propose an alternative ranking based on the proclivity of journals to publish papers that build on new ideas, and we implement this ranking via a text-based analysis of all published biomedical papers dating back to 1946. In addition, we compare our neophilia ranking to citation-based (impact factor) rankings; this comparison shows that the two ranking approaches are distinct. Prior theoretical work suggests an active role for our neophilia index in science policy. Absent an explicit incentive to pursue novel science, scientists underinvest in innovative work because of a coordination problem: for work on a new idea to flourish, many scientists must decide to adopt it in their work. Rankings that are based purely on influence thus do not provide sufficient incentives for publishing innovative work. By contrast, adoption of the neophilia index as part of journal-ranking procedures by funding agencies and university administrators would provide an explicit incentive for journals to publish innovative work and thus help solve the coordination problem by increasing scientists' incentives to pursue innovative work.

1. Introduction

The ranking of scientific journals is important because of the signal it sends to scientists about what is considered important in science. The top ranked journals by their editorial policies set standards and often also the agenda for scientific investigation. Editors make decisions about which papers to send out for review, which referees to ask for comments, requirements for additional analysis, and which papers to ultimately publish. These decisions work to check on the correctness of submitted papers, but they also let other scientists, administrators, and funding agencies know what is considered novel, important, and worthy of study (e.g. Brown 2014; Frey and Katja 2010; Katerattanakul et al. 2005; Weingart 2005). Highly ranked journals thus exert considerable influence on the direction that scientific disciplines move.

Journal rankings are also important because they provide a filter for scientists in the face of a rapidly growing scientific literature (e.g. Bird 2008). Given the vast volume of published scientific work and finite work time, it is impossible for scientists to read and independently evaluate every publication even in their field. Journal rankings provide a way to quickly identify those articles that other scientists in a field are most likely to be familiar with.

Existing measures rely almost exclusively upon citation counts to determine journal rankings.1 Citations, of course, are a good measure of the influence of any given paper; a highly cited paper, almost by definition, has influenced many other scientists.

While the reliance on citations is sensible if the goal of a ranking system is to identify the most influential journals, there is circularity in the logic. As financial rewards and professional prestige are tied to publishing in highly cited journals, scientists have a strong incentive to pursue work that has the best chance of being published in highly cited journals. Often, this entails work that builds upon and emulates other work that has been published in such journals. That a journal is highly cited need not tell us anything about what kind of science – novel science or conventional science – the journal promotes.

The view that reliance on citations has a harmful effect on the direction of science has become common; even the editor-in-chief of the most cited scientific journal has warned that citation-based metrics block innovation and lead to me-too science (Alberts 2013). Moreover, the rise of citation-based metrics over the past three decades may already be changing how scientists work: evidence from biomedicine shows that during this time scientists have become less likely to pursue novel research paths (Foster et al. 2015).

One important reason why rankings should consider matters in addition to influence is that both individual scientists and journals face a coordination problem in pursuing and promoting novel science.2 As new ideas are often raw when they are first born, they need revision and the attention of many scientists for the ideas to mature (Kuhn 1962; Marshall 1920). Debate among an emerging community of scientists who build on a new idea is essential both for the idea to mature. If only one scientist, or only a few, try out a new idea, this idea is unlikely to gain broader scientific attention even if the idea held great potential (Kuhn 1962). The presence of this coordination problem — that is, the dependence of scientists on other scientists to productively engage with their work — implies that even if citations accurately reflect the ex post value of working in a given area of investigation, a suboptimal amount of novel science takes place absent specific incentives that reward novel science more than conventional science. Thus, a journal ranking system that rewards only influence will provide too little incentive for scientists to pursue novel science.

Reputable journals also face a similar coordination problem; publishing a one-off paper in a new area of investigation is unlikely to generate many cites unless multiple journals publish related papers. This exacerbates the coordination problem among scientists who are considering trying out a new idea in their work, as they need their articles published in reputable journals to attract the attention of fellow scientists to this new area of investigation.

This coordination failure applies to work on new ideas when interpreted broadly (as in “new fields”) and when interpreted much more narrowly (as in “new areas of investigation”). The latter interpretation encompasses almost any scientific play with a new idea; any such attempt is based on the hope that it results in successfully opening a new area of investigation. One such example is the use of the transformative and widely celebrated “CRISPR” technology for human genome editing. Before CRISPR, other approaches (such as “TALE”) had been applied in human genome editing, and researchers who decided to try out CRISPR in the context of human genome editing — in place of the well-established TALE technology — considered it to be the riskier research avenue within the field of therapeutic genetics.3

Beyond coordination problems, there are at least two other reasons why influence-based rankings alone do not provide sufficient incentives for high-impact journals to publish novel science. First, disruptive science causes a decrease in citations to past breakthroughs, so journals that published those past breakthroughs face a disincentive in publishing novel work. Second, editors of high-impact journals are often people whose ideas disruptive science seeks to challenge.

Given these considerations, the ranking of scientific journals should instead be based at least partly on things that measure what type of science is being pursued. We emphasize here that our goal is not to displace influence-based rankings entirely, but rather to provide an alternate ranking that measures an aspect of science missed by the traditional ranking criteria.

In this paper, we construct a new journal ranking that measures to what extent the articles published by a given journal build on new ideas. Our neophilia-based ranking is tied directly to an objective of science policy; journals are ranked higher if they publish articles that explore the scientific frontier. Our index is thus a useful complement to citation-based rankings — the latter fail to reward journals that promote innovative science.

To construct our neophilia ranking of journals, we focus on journals in medicine because of the substantive importance of medical science, because this focus builds on our existing work (e.g. Packalen and Bhattacharya 2015a), and because of the availability of a large and comprehensive database on publications in medicine (MEDLINE).

For our corpus of medical research papers, we must first determine which published papers are built on new ideas and which are built on older ones. We base our determination on the textual content of each paper. We take advantage of the availability of a large and well-accepted thesaurus, the United Medical Language System (“UMLS”). We allow each term in this thesaurus to represent an idea, broadly interpreted. Hence, to determine which ideas each paper builds upon, we search each paper for all 5+ million terms that appear in the UMLS thesaurus. For each paper we then determine the vintage of each term that appears in it based the paper's publication year and the year in which the term first appeared in published biomedical literature. Next, we determine for each paper the age of the newest term that appears in it. Based on this age of the newest term that appears in each paper, we then determine for each journal to what degree it publishes innovative work — papers that mention relatively new terms. This yields us the neophilia index that we propose in this paper.

One advantage of the UMLS thesaurus is that it reveals which terms are synonyms, allowing us to treat synonyms as representing the same idea when we construct our neophilia index. However, we also show that neophilia rankings change very little when we employ an alternative approach to constructing the neophilia index that does not take advantage of the UMLS thesaurus in any way. In this alternative approach, we construct the neophilia index by indexing all words and word sequences that appear in each paper rather than just those that appear in the UMLS thesaurus. This sensitivity analysis shows that the neophilia ranking can be constructed even in areas of science for which no thesaurus is available.

Not all papers that our approach deems novel started new fields or even new areas of investigation. We view this a feature of our approach, since it allows us to capture the trying out of some new ideas that do not ultimately succeed on a grand scale; scientific progress depends on trying ideas that ultimately fail along with ideas that ultimately succeed.

Besides calculating the new ranking for each journal, we examine the relationship between the neophilia-based measure and the traditional citation-based impact factor rankings. We find that impact factor ranking and our neophilia index are only weakly linked, which shows that our index captures a distinct aspect of each journal's role in promoting scientific progress.

2. Methods

In this section, we present the two sets of medical journals to which we apply our neophilia ranking procedure and explain how the neophilia index is constructed. Next, we discuss our approach for comparing the neophilia ranking against an influence-based ranking. The section concludes with methods for four sets of sensitivity analyses.

2.1 Journals Sets

We analyze two sets of medical journals. The first set of journals is the set of 156 journals that are ranked annually by Thomson Reuters (TR) under the category General and Internal Medicine. Journals in this category are aimed at a general medical audience, so it does not include field journals — even highly ranked field journals — that are aimed at practitioners in a particular medical specialty. This set has at least two major advantages. The general nature of these journals implies that the rankings will be relevant to a large audience. Moreover, reliance on a journal set used by TR allows us to examine the relationship between our neophilia index and the widely used citation-based impact factor ranking published by TR.

While TR lists 156 journals in the General and Internal Medicine category, we calculate the neophilia index for only 126 journals. This is for several reasons. Four of the 156 journals are not indexed in MEDLINE. Some of the 156 journals are exclusively review journals (e.g. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews) whereas we rank only original research articles (and thereby exclude reviews, editorials, commentaries, etc.). Moreover, for some journals MEDLINE has little or no information on article abstracts; we only rank articles for which the database includes sufficient textual information.

The second set of journals that we analyze is the set of 119 journals that are listed as belonging to the Core Clinical Journals category by MEDLINE. This set includes general medicine journals as well as well-known field journals from different areas of medicine. This set allows us to test whether it is journals aimed at the whole profession or specialized journals that play a dominant role in promoting the trying out of new ideas.

2.2 Constructing the Neophilia Index for a Journal

The neophilia index that we propose measures a journal's propensity to publish innovative articles that try out new ideas. We construct this index based on the textual content of original research articles that appear in a journal.4

We determine the textual content of a journal from the MEDLINE database. MEDLINE is a comprehensive database of 20+ million biomedical scientific publications. The coverage of this database is comprehensive beginning in 1946. For articles published before 1975, the textual information generally includes the title but not the abstract of each article. For articles published since 1975, the data generally include both the title and the abstract of each article. Thus, to guarantee the availability of textual content, we calculate the neophilia index for a journal based on articles published during 1980-2013 in our baseline specification.

To determine which ideas each paper builds upon we use the United Medical Language System (UMLS) metathesaurus. The UMLS database is a comprehensive and widely used medical thesaurus that consists of over 5 million different terms (e.g. Chen et al. 2007; Xu et al. 2010). The UMLS database is referred to as a metathesaurus because it links the terms mentioned in over 100 separate medical vocabularies. Each term in the UMLS database is linked to one or more of 127 categories of terms. An earlier version of this paper (available at www.nber.org/papers/w21579) presents the name of each of these categories and for each category a plethora of examples of terms in the category.

For the sake of several sensitivity analyses (see section 2.4), we grouped each of UMLS's 127 categories for terms to the following 8 category groups (the number in parenthesis is the number of UMLS categories we assigned to the group): Clinical (21), Anatomy (8), Drug (4), Research Tools (3), Basic Science I (11), Basic Science II (31), Miscellaneous I (27), and Miscellaneous II (22). We constructed two basic science groups merely to limit the size of each list; the first includes processes and functions, the other everything else. The group “Miscellaneous II” includes many terms that one may argue do not represent idea inputs to scientific work in the traditional sense; in a sensitivity analysis we exclude from the analysis the terms in this group.

An additional curated feature of the UMLS metathesaurus is that terms that are considered synonyms are linked to one another.5 This feature enables us to treat terms that are synonyms as representing the same idea. We will thus avoid the mistake of assigning a high neophilia ranking to a journal that merely prefers to publish articles that use novel terminology for seasoned ideas.

The construction of the neophilia index for a journal proceeds in four steps. In steps 1-3 we treat original research articles published in any journal the same. That is, our determination of whether a paper published relies on new ideas depends on all research articles in MEDLINE from its inception, rather than on a particular journal set. Only in step 4 do we focus the analysis on the two journal sets mentioned in section 2.1.

Step 1. Determine when each term was new

For each term in the UMLS thesaurus, we determine the earliest publication year among all those articles in the MEDLINE database that mention the term (we search all 20+ million MEDLINE articles for each term). For terms that have no synonyms in the UMLS metathesaurus, we refer to this year of first appearance in MEDLINE as the term's cohort year. For a term that has synonyms, we find the earliest year in which the term itself or any of its synonyms appeared in MEDLINE and then assign that year as the cohort year of the term. Thus, all terms that are considered synonyms receive the same cohort year. Determining the cohort year of each term allows us to determine in the next steps which papers mention terms that are relatively new.

Step 2. Determine age of newest term mentioned in each article

For each original research paper in MEDLINE we then index which of the 5+ million terms in the UMLS database appear in the article. Having found which UMLS terms appear in each article, we determine the age of each such UMLS term by calculating the difference between the publication year of the MEDLINE article in question and the cohort year of the UMLS term. Next, we determine the identity and age of the newest terms mentioned in each paper (here we consider all terms in cohorts 1961-2013). This concludes Step 2.

Before presenting Step 3, we pause to discuss lists of example terms in each category. These lists are shown in an earlier version of this paper (available at www.nber.org/papers/w21579). We hope that browsing those lists of example terms makes two issues evident to the reader. First, the terms captured by our approach represent ideas that have served as inputs to biomedical science in recent decades. Second, the cohort year for most terms is a reasonable reflection of the time when the idea represented by the term was a new idea as an input to biomedical scientific work.

Our results reported further below (section 3) also point to a less subjective validation: specific journals that aim to promote the very thing that our approach aims to capture are ranked very high by our approach. In principle, one could attempt to further validate our approach by comparing our rankings against scientists' perceptions of the innovativeness of the articles published in each journal. This would mimic the way citation-based rankings are evaluated (scientists are asked about the quality of articles). We have chosen not to do this exercise for two reasons. First, conducting a large scale survey is beyond the resources currently available to us. Second, it is not clear to us that scientists' responses to questions about innovativeness would be that informative; scientists themselves often are not particularly good scientific historians, and would not necessarily be able to interpret the question as intended. Indeed, the ubiquitous focus on impact factors as a measure of a journal's success has made it hard for scientists to distinguish between concepts such as quality, impact, and innovativeness. Hence, the scientists' responses to a survey about innovativeness might instead reflect their perceptions about the journal's impact or quality. For these reasons, we leave formal validation exercises for further studies.

Step 3. Determining which papers mention relatively new terms

Having determined the age of the newest UMLS term that appear in each article, we next determine which articles mention relatively new terms. To achieve this, we first order all original research papers published in any given year based on the age of the newest UMLS term that mention in it. Using this ordering, we then construct a dummy variable Top 20% by Age of Newest Idea Input that is 1 for papers that are in the top 20% based on the age of the newest term that appears in them and 0 for all other papers. Thus, this dummy variable is 1 for papers that mention one or more relatively new terms and 0 for papers that only mention older terms.

The reason for using a dummy variable to measure the vintage of idea inputs is that the age of an idea input that can be considered new is relative — it depends on the research area and on the year of publication. In some areas novel work involves building on only 3 year old ideas, whereas in other areas it involves building on ideas that are 10 years old or even older. Our variable identifies those papers that build on new ideas relative to other comparable papers.

In our baseline specification, the comparison group for each article is very broad when the Top 20% by Age of Newest Idea Input dummy variable is constructed: it is all other articles published in the same year. However, in sensitivity analyses we employ much narrower comparison groups. Specifically, we compare articles to others published in the same research area in the same year (section 2.4.3). We selected the 20% cutoff to allow for such very strict comparison sets in the sensitivity analyses.6 In our related previous work (Packalen and Bhattacharya 2015a) we have not found any meaningful differences owing to different cutoff percentiles.

Step 4. Constructing the neophilia index for a journal

Having constructed for each article our measure for whether the paper mentions a new term (the dummy variable Top 20% by Age of Newest Idea Input), we then calculate the average value of this variable for each journal during the time period under consideration.7 Next, we perform a normalization: we divide these journal-specific average values by the average value of the variable Top 20% by Age of Newest Idea Input for all articles in the journal set, General and Internal Medicine. The resulting variable is our journal-specific neophilia index. Based on this index, we determine the neophilia ranking of each journal in a given journal set.

Given our normalization, the neophilia index is between 0 and 1 for journals that promote the trying out of new ideas less than the average article in the journal set General and Internal Medicine. For example, a neophilia index of 0.75 for a journal implies that articles in it mention a relatively new idea 25% less often than the average article in this journal set. The neophilia index is greater than 1 for journals that promote the trying out of new ideas more than the average article published in this journal set. For example, a neophilia index of 1.5 for a journal implies that articles in it mention a relatively new idea 50% more often than the average article published in the journal set General and Internal Medicine.

2.3 Comparison of a Neophilia Index and Citation Ranking

To compare our neophilia index against citation based journal rankings, we use impact factor rankings published by TR for the year 2013 for journals in the set General and Internal Medicine. We measure the relationship between our neophilia index and the citation ranking. Our goal for this part of our analysis is to ask whether our neophilia index captures an aspect of scientific progress that is distinct from features of scientific progress that are captured by citation based measures. If a journal with a higher citation ranking than another journal always has also a higher neophilia ranking than the other journal, the neophilia index would be of little marginal value. On the other hand, the neophilia index does have value as an input to science policy if the relationship between the neophilia index and impact factor rankings is weak. We emphasize that this analysis is not meant as an in depth analysis of the factors that determine the link between the neophila measure and the influence-based measure, but rather to show that in this simple reduced form analysis, our neophila measure is measuring something different.

2.4 Sensitivity Analyses

We perform four sets of sensitivity analyses.

2.4.1 Sensitivity Analysis I: Time Periods

In our baseline specification, we calculate the neophilia index of a journal based on the 8+ million original research articles published between 1980 and 2013. To examine how stable the neophilia index is over time, we also calculate the index separately for four time periods: 1980s, 1990s, 2000s, and 2010-2013.

2.4.2 Sensitivity Analysis II: Subsets of UMLS Terms

In our baseline specification, we construct the neophilia index based on all UMLS terms. In this set of sensitivity analyses, we construct the index based on narrower sets of UMLS terms.

First, we calculate the neophilia index after excluding mentions of terms in the category group “Miscellaneous II.” This allows us to examine if the neophilia ranking is robust to excluding terms that may not reflect traditional idea inputs to scientific work. 8

Second, we calculate the neophilia index after excluding mentions of terms in the category groups “Miscellaneous II” and “Drug”. This allows us to examine to what extent our baseline neophilia ranking is driven by research on novel pharmaceutical agents.

Third, we calculate the neophilia index by only including in the analysis terms in the category groups “Clinical” and “Drug”. This allows us to examine how different the neophilia rankings would be for a decision maker that is only interested in advancing applied clinical knowledge.

2.4.3 Sensitivity Analysis III: Narrower Comparison Groups

In our baseline specification, we construct the neophilia index by comparing each article to all articles published in the same year. In this set of sensitivity analyses, we address the fact that the extent of novelty may vary across fields. A journal may appear innovative when inspected relative to all of medicine but at the same time appear not as innovative when inspected relative to the standards of other journals in the same field. Specifically, in these sensitivity analyses, we compare the publication to other publications published in the same research area in the same year when we determine a publication's top 20% status (rather than simply the same year).

For these analyses, we follow our earlier work (Packalen and Bhattacharya 2015a) and determine research areas based on the 6-digit Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) codes by which each MEDLINE publication indexed. MeSH is a controlled medical vocabulary of over 27,000 terms.9 We consider papers marked with the same MeSH codes to be in the same research area. In one analysis, we construct research areas based on the MeSH Disease terms mentioned in each article; for our purposes these terms serve as a proxy for clinical research areas. In another analysis, we construct the research areas based on the MeSH Phenomena and Processes terms mentioned in each article; for our purposes these terms serve as a proxy for basic research areas.

Having determined the comparison group (based on research area and year of publication) for each publication, we determine which papers in that comparison group are in the top 20% based on the age of the newest term mentioned in them. We then use this dummy variable to construct the neophilia index analogously to the baseline specification.

2.4.4 Sensitivity Analysis IV: N-Gram Approach

In our baseline specification, we determine the ideas that each paper builds upon based on the vintage of any UMLS terms that appear in it. In this sensitivity analysis, we follow our earlier work (Packalen and Bhattacharya 2015a b c) and determine the ideas that each paper builds upon based the vintage of words and 2- and 3- word sequences that appear in it.

In this alternative approach (“n-gram approach”), we index each publication for all 1- 2- and 3-word sequences that appear in it. For all such “concepts” that appear in MEDLINE, we then determine the cohort year of each such concept as the earliest publication year among papers that mention the concept in the MEDLINE database.

For each concept cohort we then determine which 100 concepts in the cohort are the most popular concepts in the cohort. Popularity of each concept is determined based on the number of publications in which it has appeared since its first appearance. For each cohort year during 1970-2013, we then cull by hand through the list of the top 100 most popular concepts in the cohort and exclude concepts that appear to us to not represent idea inputs in the traditional sense. The remaining top 100 concepts for each cohort are then used to determine the vintage of idea inputs in any given publication — in the exact the same way that we employ the UMLS thesaurus in the baseline specification. We then calculate the neophilia index for a journal based on the vintage of the newest idea input in each paper.

One advantage of constructing the neophilia index using the n-gram approach is that it does not depend on the availability of a thesaurus, which may not exist for all fields. One potential disadvantage of the n-gram approach relative to the baseline specification is that the it may assign a different cohort year to two words that are synonyms. To the extent that this occurs, in the present context it would imply that journals that prefer using newer terminology for old ideas receive higher neophilia scores even though the work published in these journals is not particularly innovative in any way that genuinely advances science.

3. Results

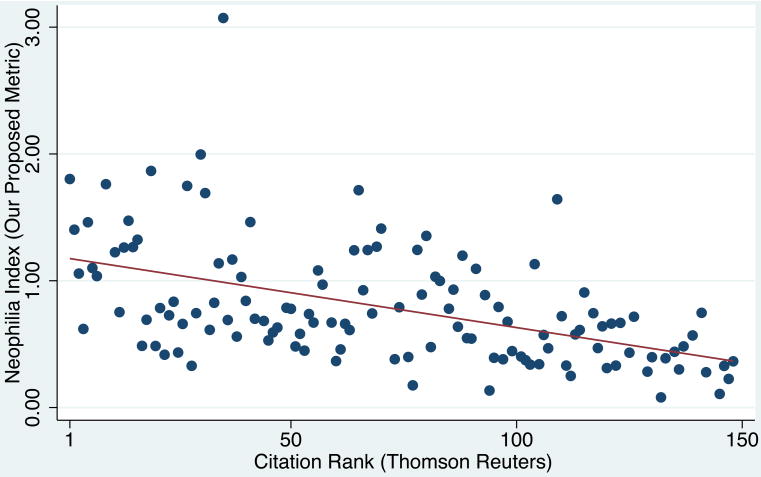

We present our result in four sets: (1) neophilia rankings for 10 highly cited journals in the General and Internal Medicine journal set (Table 1), (2) neophilia rankings for all journals in the same journal set (Table 2), (3) a scatterplot and a regression line for the relationship between the neophilia index and the citation-based impact factor rankings for the same journal set (Figure 1), and (4) neophilia rankings for the journal set Core Clinical Journals (Table 3).

Table 1.

Neophilia Rankings for 10 Highly Cited Journals in General and Internal Medicine.

| (1a) | (1b) | (1c) | (1d) | (2a) | (2b) | (2c) | (2d) | (3a) | (3b) | (3c) | (4a) | (4b) | (5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neophilia Ranking |

Journal | Number of Articles |

Neophilia Index |

1980s | 1990s | 2000s | 2010-2013 | Exclude UMLS Terms in Category Group “Miscellaneo us II” |

Exclude UMLS Terms in Category Groups “Miscellaneo us II” and “Drug” |

Only Include UMLS Terms in Category Groups “Clinical” and “Drug” |

Compare Papers Only within Same Clinical Research Area |

Compare Papers Only within Same Basic Research Area |

N-Gram Approach |

| 1 | N Engl J Med | 8765 | 1.81 | 1.54 | 1.78 | 1.85 | 2.06 | 1.87 | 1.69 | 1.60 | 1.69 | 1.78 | 1.71 |

| 2 | BMC Med | 406 | 1.76 | 1.77 | 1.75 | 1.69 | 1.81 | 1.25 | 1.44 | 1.48 | 2.17 | ||

| 3 | Ann Intern Med | 4948 | 1.50 | 1.99 | 1.86 | 1.10 | 1.04 | 1.47 | 1.46 | 1.50 | 1.27 | 1.57 | 1.67 |

| 4 | Lancet | 13518 | 1.41 | 1.54 | 1.37 | 1.22 | 1.49 | 1.41 | 1.28 | 1.16 | 1.31 | 1.40 | 1.39 |

| 5 | Mayo Clin Proc | 2063 | 1.22 | 1.29 | 1.05 | 1.28 | 1.28 | 1.23 | 1.23 | 1.14 | 1.18 | 1.24 | 1.07 |

| 6 | PLoS Med | 1021 | 1.11 | 1.44 | 0.78 | 1.14 | 1.18 | 0.97 | 1.10 | 1.00 | 1.51 | ||

| 7 | JAMA | 11180 | 1.08 | 1.21 | 1.09 | 1.20 | 0.81 | 1.05 | 1.09 | 1.00 | 1.08 | 1.07 | 1.12 |

| 8 | JAMA Intern Med | 6150 | 1.04 | 1.22 | 1.32 | 0.94 | 0.70 | 1.02 | 1.02 | 1.22 | 1.08 | 1.10 | 1.14 |

| 9 | CMAJ | 3449 | 0.76 | 1.01 | 0.66 | 0.63 | 0.72 | 0.71 | 0.74 | 0.68 | 0.84 | 0.73 | 0.74 |

| 10 | BMJ | 7656 | 0.62 | 0.88 | 0.68 | 0.44 | 0.47 | 0.57 | 0.54 | 0.64 | 0.71 | 0.66 | 0.51 |

| Other Journals in “General and Internal Medicine” | 167772 | 0.92 | 0.86 | 0.89 | 0.96 | 0.97 | 0.92 | 0.93 | 0.95 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.92 |

Explanations for the columns:

(1a-1d) Column 1a shows the neophilia ranking; the ranking for each journal is calculated based on original research articles published in the journal during 1980-2013. Column 1b shows the MEDLINE abbreviation of the journal. Column 1c shows for each journal the number of publications based on which the neophilia index was calculated (articles on which the database has little or no textual information are excluded). Column 1d shows the neophilia index based on which the ranking reported in column 1a is determined.

(2a-2d): Columns 2a-2d show the neophilia index for four different time periods: 1980s, 1990s, 2000s, and 2010-2013. Across these columns, other aspects of the analysis are as in the analysis reported in column 1d.

(3a-3c): Column 3a shows the neophilia index when UMLS terms in category group “Miscellaneous II” are excluded from the analysis. Column 3b shows the neophilia index when UMLS terms category groups “Miscellaneous II” and “Drug” are excluded from the analysis. Column 3c shows the neophilia index when only UMLS terms category groups “Clinical” and “Drug” are included in the analysis. Across these columns, other aspects of the analysis are as in the analysis reported in column 1d.

(4a-4b): Column 4a shows the neophilia index when the relative age of terms mentioned in each article is calculated by comparing the article to other articles published in the same clinical research area in the same year (as opposed to a comparison of the article to all other articles published in the same year). Column 4b shows the neophilia index when the relative age of terms mentioned in each article is calculated by comparing the article to other articles published in the same basic research area in the same year. Across these columns, other aspects of the analysis are as in the analysis reported in column 1d.

(5): Column 5 shows the neophilia index when calculated using the n-gram approach (Packalen and Bhattacharya 2015a,b,c) as opposed to using the UMLS metathesaurus approach that was employed to calculate the neophilia indices reported in columns 1-4. The neophilia index for a journal is calculated based on original research articles published during 1980-2013.

Table 2.

Neophilia Rankings for Journals in General and Internal Medicine.

| (1a) | (1b) | (1c) | (1d) | (2a) | (2b) | (2c) | (2d) | (3a) | (3b) | (3c) | (4a) | (4b) | (5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neophilia Ranking |

Journal | Number of Articles |

Neophilia Index |

1980s | 1990s | 2000s | 2010-2013 | Exclude UMLS Terms in Category Group “Miscellaneo us II” |

Exclude UMLS Terms in Category Groups “Miscellaneo us II” and “Drug” |

Only Include UMLS Terms in Category Groups “Clinical” and “Drug” |

Compare Papers Only within Same Clinical Research Area |

Compare Papers Only within Same Basic Research Area |

N-Gram Approach |

| 1 | Curr Med Res Opin | 2865 | 3.07 | 2.59 | 2.20 | 3.89 | 3.60 | 3.20 | 1.09 | 2.59 | 2.67 | 3.02 | 1.61 |

| 2 | Am J Chin Med | 1584 | 2.00 | 1.91 | 2.24 | 2.25 | 1.58 | 2.13 | 2.00 | 1.37 | 1.82 | 2.07 | 1.08 |

| 3 | Transl Res | 4065 | 1.87 | 1.55 | 1.68 | 2.06 | 2.18 | 2.05 | 2.35 | 1.68 | 1.67 | 1.85 | 2.34 |

| 4 | N Engl J Med | 8765 | 1.80 | 1.54 | 1.78 | 1.84 | 2.05 | 1.87 | 1.69 | 1.60 | 1.69 | 1.77 | 1.71 |

| 5 | BMC Med | 406 | 1.76 | 1.77 | 1.75 | 1.68 | 1.81 | 1.25 | 1.44 | 1.44 | 2.16 | ||

| 6 | Eur J Clin Invest | 3551 | 1.75 | 1.36 | 1.42 | 2.01 | 2.20 | 1.86 | 2.11 | 1.59 | 1.62 | 1.81 | 2.26 |

| 7 | Int J Med Sci | 438 | 1.71 | 1.63 | 1.80 | 1.98 | 2.24 | 1.56 | 1.51 | 1.44 | 1.72 | ||

| 8 | Int J Clin Pract | 2455 | 1.69 | 1.25 | 1.42 | 1.94 | 2.14 | 1.70 | 0.80 | 1.40 | 1.56 | 1.73 | 0.99 |

| 9 | Acta Clin Belg | 537 | 1.64 | 1.37 | 1.70 | 1.76 | 1.73 | 1.72 | 1.26 | 1.41 | 1.33 | 1.58 | 1.31 |

| 10 | Am J Med | 6304 | 1.47 | 2.38 | 1.80 | 0.88 | 0.83 | 1.44 | 1.29 | 1.47 | 1.33 | 1.50 | 1.59 |

| 11 | Am J Manag Care | 1109 | 1.46 | 1.64 | 1.66 | 1.08 | 1.17 | 0.69 | 1.08 | 1.34 | 1.51 | 1.16 | |

| 12 | Ann Intern Med | 4948 | 1.46 | 1.81 | 1.90 | 1.10 | 1.04 | 1.43 | 1.42 | 1.46 | 1.27 | 1.51 | 1.66 |

| 13 | J Investig Med | 630 | 1.41 | 0.35 | 1.95 | 1.79 | 1.55 | 1.54 | 2.12 | 1.47 | 1.64 | 1.46 | 2.00 |

| 14 | Lancet | 13518 | 1.40 | 1.53 | 1.37 | 1.21 | 1.49 | 1.41 | 1.28 | 1.16 | 1.31 | 1.39 | 1.38 |

| 15 | J Korean Med Sci | 2497 | 1.35 | 1.24 | 1.35 | 1.53 | 1.30 | 1.43 | 1.77 | 1.35 | 1.19 | 1.27 | 1.80 |

| 16 | Ann Med | 641 | 1.32 | 0.30 | 1.08 | 2.34 | 1.58 | 1.35 | 1.59 | 1.13 | 1.06 | 1.45 | 1.71 |

| 17 | Am J Med Sci | 1759 | 1.27 | 1.60 | 1.20 | 1.03 | 1.25 | 1.31 | 1.33 | 1.33 | 1.14 | 1.30 | 1.50 |

| 18 | Medicine (Baltimore) | 545 | 1.27 | 1.53 | 1.29 | 1.15 | 1.09 | 1.23 | 1.25 | 1.27 | 1.06 | 1.23 | 1.18 |

| 19 | J Intern Med | 2194 | 1.26 | 0.99 | 0.85 | 1.17 | 2.03 | 1.34 | 1.38 | 1.19 | 1.17 | 1.13 | 1.75 |

| 20 | Tohoku J Exp Med | 3686 | 1.24 | 1.13 | 1.14 | 1.26 | 1.44 | 1.32 | 1.56 | 1.19 | 1.12 | 1.18 | 1.57 |

| 21 | Postgrad Med | 2486 | 1.24 | 0.71 | 0.87 | 0.90 | 2.49 | 1.27 | 0.78 | 1.20 | 1.12 | 1.28 | 0.78 |

| 22 | Gend Med | 221 | 1.24 | 1.53 | 0.95 | 1.05 | 1.28 | 0.91 | 1.14 | 1.23 | 1.23 | ||

| 23 | Mayo Clin Proc | 2063 | 1.22 | 1.30 | 1.07 | 1.28 | 1.25 | 1.22 | 1.22 | 1.15 | 1.17 | 1.23 | 1.06 |

| 24 | Chin Med J (Engl) | 8267 | 1.20 | 0.40 | 0.90 | 1.77 | 1.72 | 1.29 | 1.60 | 1.20 | 1.01 | 1.19 | 1.47 |

| 25 | Eur J Intern Med | 484 | 1.17 | 1.03 | 1.31 | 1.16 | 1.27 | 1.22 | 1.11 | 1.20 | 1.22 | ||

| 26 | Intern Emerg Med | 240 | 1.14 | 0.58 | 1.34 | 1.49 | 1.15 | 1.29 | 1.07 | 0.96 | 1.01 | 1.31 | |

| 27 | Wien Klin Wochenschr | 1322 | 1.13 | 1.03 | 1.37 | 1.08 | 1.04 | 1.17 | 1.15 | 1.09 | 0.98 | 1.13 | 0.92 |

| 28 | PLoS Med | 1021 | 1.10 | 1.43 | 0.78 | 1.13 | 1.18 | 0.97 | 1.09 | 1.01 | 1.50 | ||

| 29 | Intern Med | 1981 | 1.09 | 0.87 | 1.08 | 1.12 | 1.30 | 1.13 | 1.25 | 1.26 | 1.04 | 1.06 | 1.45 |

| 30 | Intern Med J | 2064 | 1.08 | 1.35 | 1.19 | 0.85 | 0.93 | 1.10 | 1.12 | 1.25 | 1.05 | 1.13 | 1.09 |

| 31 | JAMA | 11180 | 1.06 | 1.14 | 1.08 | 1.19 | 0.81 | 1.03 | 1.07 | 0.98 | 1.08 | 1.05 | 1.12 |

| 32 | JAMA Intern Med | 6150 | 1.04 | 1.19 | 1.32 | 0.94 | 0.69 | 1.01 | 1.01 | 1.21 | 1.08 | 1.09 | 1.13 |

| 33 | Ann Acad Med Singapore | 2529 | 1.03 | 1.04 | 1.05 | 1.00 | 1.04 | 1.03 | 1.22 | 1.09 | 1.11 | 0.97 | 1.10 |

| 34 | Pain Med | 821 | 1.03 | 1.07 | 0.99 | 0.93 | 0.87 | 1.09 | 1.45 | 1.13 | 0.63 | ||

| 35 | Minerva Med | 1001 | 1.00 | 0.33 | 0.68 | 1.61 | 1.38 | 1.00 | 1.18 | 0.91 | 0.83 | 0.93 | 0.79 |

| 36 | J Formos Med Assoc | 2997 | 0.97 | 0.37 | 1.21 | 1.11 | 1.18 | 1.01 | 1.12 | 1.06 | 0.93 | 0.92 | 1.09 |

| 37 | Med Princ Pract | 670 | 0.93 | 0.77 | 1.09 | 1.01 | 1.18 | 1.09 | 1.04 | 0.89 | 0.83 | ||

| 38 | Postgrad Med J | 2037 | 0.93 | 1.77 | 1.01 | 0.52 | 0.39 | 0.97 | 0.71 | 1.06 | 0.84 | 0.90 | 0.82 |

| 39 | Dan Med J | 125 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 1.01 | 1.08 | 0.67 | 0.91 | 0.68 | 0.79 | |||

| 40 | Yonsei Med J | 1899 | 0.89 | 0.30 | 1.15 | 1.01 | 1.10 | 0.94 | 1.22 | 1.09 | 1.01 | 0.85 | 1.31 |

| 41 | Isr Med Assoc J | 3298 | 0.89 | 1.16 | 0.70 | 0.88 | 0.81 | 0.88 | 0.97 | 0.93 | 0.96 | 0.88 | 0.93 |

| 42 | Neth J Med | 841 | 0.84 | 0.48 | 1.00 | 1.02 | 0.86 | 0.77 | 0.52 | 0.93 | 0.88 | 0.86 | 0.97 |

| 43 | Cleve Clin J Med | 642 | 0.83 | 0.58 | 0.55 | 0.97 | 1.24 | 0.88 | 0.60 | 0.83 | 0.66 | 0.83 | 0.85 |

| 44 | QJM | 1933 | 0.83 | 1.05 | 1.10 | 0.46 | 0.70 | 0.84 | 0.94 | 0.98 | 0.87 | 0.83 | 1.06 |

| 45 | J Chin Med Assoc | 1615 | 0.79 | 0.48 | 0.87 | 0.83 | 0.99 | 0.85 | 0.92 | 1.01 | 0.85 | 0.73 | 0.77 |

| 46 | Croat Med J | 784 | 0.79 | 0.49 | 1.20 | 0.68 | 0.81 | 1.00 | 0.88 | 0.84 | 0.53 | 0.95 | |

| 47 | Swiss Med Wkly | 1043 | 0.79 | 0.58 | 0.70 | 1.17 | 0.69 | 0.81 | 0.80 | 0.90 | 0.77 | 0.75 | 0.94 |

| 48 | Med J Aust | 4793 | 0.78 | 0.98 | 1.00 | 0.54 | 0.62 | 0.74 | 0.76 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.73 |

| 49 | South Med J | 3295 | 0.78 | 0.92 | 1.01 | 0.45 | 0.74 | 0.77 | 0.86 | 0.96 | 0.85 | 0.78 | 0.77 |

| 50 | J Am Board Fam Med | 596 | 0.78 | 1.11 | 0.94 | 0.53 | 0.54 | 0.68 | 0.72 | 0.85 | 0.80 | 0.74 | 0.84 |

| 51 | CMAJ | 3449 | 0.75 | 1.01 | 0.67 | 0.63 | 0.70 | 0.71 | 0.74 | 0.68 | 0.83 | 0.74 | 0.74 |

| 52 | Rev Invest Clin | 314 | 0.75 | 0.57 | 1.10 | 0.63 | 0.70 | 0.75 | 0.80 | 0.94 | 0.74 | 0.71 | 0.89 |

| 53 | J Pain Symptom Manage | 1789 | 0.74 | 0.52 | 0.86 | 1.07 | 0.54 | 0.51 | 0.44 | 0.63 | 1.17 | 0.68 | 0.29 |

| 54 | J Nippon Med Sch | 771 | 0.74 | 0.27 | 0.70 | 1.04 | 0.97 | 0.77 | 0.86 | 0.75 | 0.54 | 0.83 | 1.12 |

| 55 | J Travel Med | 511 | 0.74 | 1.31 | 0.73 | 0.19 | 0.76 | 0.38 | 0.79 | 0.91 | 0.76 | 0.38 | |

| 56 | S Afr Med J | 4492 | 0.74 | 1.04 | 0.73 | 0.51 | 0.68 | 0.77 | 0.77 | 0.96 | 0.76 | 0.80 | 0.72 |

| 57 | J Gen Intern Med | 1758 | 0.73 | 0.52 | 0.91 | 0.77 | 0.71 | 0.47 | 0.61 | 0.74 | 0.87 | 0.74 | 0.86 |

| 58 | Ann Saudi Med | 448 | 0.72 | 0.54 | 0.90 | 0.75 | 1.02 | 1.02 | 0.64 | 0.71 | 0.68 | ||

| 59 | Acta Clin Croat | 671 | 0.72 | 0.37 | 1.01 | 0.75 | 0.74 | 0.76 | 0.94 | 0.78 | 0.68 | 0.79 | 0.61 |

| 60 | J Hosp Med | 237 | 0.70 | 0.49 | 0.91 | 0.71 | 0.71 | 0.76 | 0.60 | 0.68 | 0.62 | ||

| 61 | Am J Prev Med | 2118 | 0.69 | 0.81 | 0.93 | 0.44 | 0.59 | 0.55 | 0.64 | 0.71 | 0.93 | 0.76 | 0.63 |

| 62 | Br J Gen Pract | 1714 | 0.69 | 0.92 | 0.60 | 0.57 | 0.67 | 0.52 | 0.60 | 0.53 | 0.79 | 0.70 | 0.42 |

| 63 | Pol Arch Med Wewn | 420 | 0.68 | 0.24 | 0.00 | 0.73 | 1.76 | 0.74 | 0.94 | 0.82 | 0.58 | 0.74 | 0.91 |

| 64 | J Natl Med Assoc | 2055 | 0.68 | 0.79 | 0.78 | 0.66 | 0.48 | 0.66 | 0.75 | 0.86 | 0.70 | 0.68 | 0.75 |

| 65 | Indian J Med Res | 4977 | 0.67 | 0.31 | 0.66 | 0.74 | 0.97 | 0.70 | 0.92 | 0.76 | 0.62 | 0.65 | 0.71 |

| 66 | Ups J Med Sci | 661 | 0.67 | 0.70 | 0.30 | 0.65 | 1.03 | 0.70 | 0.74 | 0.72 | 0.74 | 0.71 | 0.94 |

| 67 | Medicina (Kaunas) | 514 | 0.67 | 0.71 | 0.63 | 0.69 | 0.84 | 0.93 | 0.64 | 0.68 | 0.56 | ||

| 68 | Scott Med J | 899 | 0.66 | 0.82 | 0.49 | 0.61 | 0.73 | 0.58 | 0.56 | 0.63 | 0.62 | 0.67 | 0.47 |

| 69 | J Eval Clin Pract | 625 | 0.66 | 0.56 | 0.64 | 0.78 | 0.37 | 0.51 | 0.53 | 0.91 | 0.73 | 1.13 | |

| 70 | Palliat Med | 616 | 0.66 | 1.06 | 0.39 | 0.53 | 0.30 | 0.25 | 0.52 | 1.22 | 0.59 | 0.17 | |

| 71 | Saudi Med J | 2765 | 0.64 | 0.48 | 0.81 | 0.65 | 0.88 | 0.92 | 0.61 | 0.62 | 0.73 | ||

| 72 | Arch Iran Med | 479 | 0.64 | 0.55 | 0.72 | 0.68 | 0.84 | 1.08 | 0.65 | 0.56 | 0.55 | ||

| 73 | J Womens Health (Larchmt) | 1517 | 0.63 | 0.62 | 0.65 | 0.62 | 0.57 | 0.57 | 0.84 | 0.74 | 0.64 | 0.73 | |

| 74 | BMJ | 7656 | 0.62 | 0.88 | 0.69 | 0.44 | 0.47 | 0.57 | 0.54 | 0.64 | 0.71 | 0.66 | 0.51 |

| 75 | Amyloid | 433 | 0.61 | 0.61 | 0.70 | 0.53 | 0.66 | 0.95 | 1.13 | 1.18 | 0.60 | 1.18 | |

| 76 | Singapore Med J | 2414 | 0.61 | 0.42 | 0.59 | 0.68 | 0.76 | 0.57 | 0.64 | 0.74 | 0.68 | 0.59 | 0.57 |

| 77 | Mt Sinai J Med | 902 | 0.61 | 0.24 | 0.81 | 0.82 | 0.57 | 0.59 | 0.61 | 0.71 | 0.72 | 0.62 | 0.70 |

| 78 | J Urban Health | 1158 | 0.59 | 0.29 | 1.01 | 0.61 | 0.45 | 0.56 | 0.69 | 1.04 | 0.80 | 0.59 | 0.80 |

| 79 | Am Fam Physician | 2238 | 0.58 | 0.68 | 0.68 | 0.51 | 0.45 | 0.58 | 0.47 | 0.70 | 0.61 | 0.59 | 0.40 |

| 80 | Afr Health Sci | 477 | 0.58 | 0.53 | 0.62 | 0.58 | 0.66 | 0.72 | 0.57 | 0.63 | 0.43 | ||

| 81 | J Fam Pract | 2268 | 0.57 | 0.76 | 0.70 | 0.65 | 0.19 | 0.54 | 0.51 | 0.64 | 0.74 | 0.64 | 0.41 |

| 82 | Vojnosanit Pregl | 933 | 0.57 | 0.28 | 0.21 | 0.54 | 1.24 | 0.60 | 0.65 | 0.67 | 0.61 | 0.63 | 0.35 |

| 83 | Panminerva Med | 875 | 0.56 | 0.34 | 0.40 | 0.56 | 0.94 | 0.61 | 0.60 | 0.84 | 0.62 | 0.59 | 0.76 |

| 84 | Dan Med Bull | 655 | 0.55 | 0.42 | 0.56 | 0.58 | 0.63 | 0.54 | 0.66 | 0.66 | 0.50 | 0.55 | 0.62 |

| 85 | J Postgrad Med | 830 | 0.54 | 0.19 | 0.40 | 0.90 | 0.69 | 0.55 | 0.67 | 0.79 | 0.68 | 0.51 | 0.48 |

| 86 | J R Soc Med | 1606 | 0.53 | 0.75 | 0.54 | 0.67 | 0.16 | 0.47 | 0.49 | 0.46 | 0.64 | 0.46 | 0.34 |

| 87 | Ann Fam Med | 321 | 0.49 | 0.56 | 0.42 | 0.30 | 0.27 | 0.50 | 0.59 | 0.55 | 0.40 | ||

| 88 | Br Med Bull | 105 | 0.49 | 0.51 | 0.46 | 0.72 | 0.79 | 0.45 | 0.41 | 0.64 | 0.66 | ||

| 89 | West Indian Med J | 1343 | 0.48 | 0.40 | 0.47 | 0.51 | 0.55 | 0.47 | 0.59 | 0.61 | 0.52 | 0.48 | 0.52 |

| 90 | Fam Pract | 1154 | 0.48 | 0.55 | 0.43 | 0.55 | 0.40 | 0.29 | 0.44 | 0.38 | 0.64 | 0.48 | 0.34 |

| 91 | Med Clin (Barc) | 881 | 0.48 | 0.23 | 0.74 | 0.33 | 0.61 | 0.47 | 0.35 | 0.42 | 0.36 | 0.46 | 0.43 |

| 92 | Ir J Med Sci | 1420 | 0.47 | 0.32 | 0.69 | 0.40 | 0.47 | 0.50 | 0.63 | 0.80 | 0.62 | 0.48 | 0.60 |

| 93 | Mil Med | 2977 | 0.47 | 0.27 | 0.56 | 0.57 | 0.48 | 0.35 | 0.42 | 0.48 | 0.67 | 0.48 | 0.47 |

| 94 | Chronic Dis Can | 195 | 0.46 | 0.52 | 0.61 | 0.24 | 0.40 | 0.41 | 0.19 | 0.46 | 0.47 | 0.33 | |

| 95 | BMC Fam Pract | 515 | 0.45 | 0.52 | 0.38 | 0.27 | 0.39 | 0.49 | 0.55 | 0.48 | 0.36 | ||

| 96 | Fam Med | 445 | 0.45 | 0.35 | 0.81 | 0.40 | 0.22 | 0.36 | 0.41 | 0.41 | 0.67 | 0.48 | 0.28 |

| 97 | J Coll Physicians Surg Pak | 1193 | 0.44 | 0.37 | 0.51 | 0.47 | 0.60 | 0.92 | 0.62 | 0.41 | 0.38 | ||

| 98 | Prev Med | 3071 | 0.43 | 0.81 | 0.44 | 0.31 | 0.17 | 0.38 | 0.48 | 0.48 | 0.60 | 0.48 | 0.50 |

| 99 | Bratisl Lek Listy | 1175 | 0.43 | 0.13 | 0.58 | 0.49 | 0.52 | 0.43 | 0.48 | 0.51 | 0.52 | 0.41 | 0.42 |

| 100 | Dtsch Arztebl Int | 86 | 0.42 | 0.42 | 0.27 | 0.21 | 0.64 | 0.53 | 0.47 | 0.08 | |||

| 101 | Prim Care | 370 | 0.40 | 0.45 | 0.34 | 0.42 | 0.37 | 0.48 | 0.37 | 0.59 | 0.36 | 0.42 | |

| 102 | Rev Med Interne | 362 | 0.40 | 1.20 | 0.22 | 0.17 | 0.00 | 0.41 | 0.16 | 0.30 | 0.27 | 0.39 | 0.11 |

| 103 | J Pak Med Assoc | 2941 | 0.40 | 0.28 | 0.46 | 0.40 | 0.45 | 0.41 | 0.46 | 0.54 | 0.45 | 0.42 | 0.31 |

| 104 | Med Probl Perform Art | 73 | 0.39 | 0.39 | 0.43 | 0.50 | 0.17 | 0.62 | 0.36 | 0.00 | |||

| 105 | Br J Hosp Med (Lond) | 1370 | 0.39 | 0.40 | 0.72 | 0.32 | 0.12 | 0.39 | 0.34 | 0.43 | 0.36 | 0.40 | 0.16 |

| 106 | Can Fam Physician | 1097 | 0.38 | 0.34 | 0.36 | 0.44 | 0.33 | 0.25 | 0.52 | 0.56 | 0.40 | 0.34 | |

| 107 | Natl Med J India | 650 | 0.38 | 0.41 | 0.38 | 0.34 | 0.39 | 0.45 | 0.60 | 0.57 | 0.46 | 0.57 | |

| 108 | J R Army Med Corps | 488 | 0.37 | 0.43 | 0.56 | 0.26 | 0.24 | 0.38 | 0.36 | 0.31 | 0.67 | 0.36 | 0.14 |

| 109 | Scand J Prim Health Care | 831 | 0.37 | 0.66 | 0.23 | 0.29 | 0.29 | 0.34 | 0.37 | 0.46 | 0.44 | 0.36 | 0.22 |

| 110 | Srp Arh Celok Lek | 358 | 0.36 | 0.19 | 0.00 | 0.90 | 0.42 | 0.40 | 0.49 | 0.37 | 0.38 | 0.47 | |

| 111 | Aviat Space Environ Med | 4150 | 0.34 | 0.64 | 0.27 | 0.23 | 0.23 | 0.34 | 0.38 | 0.44 | 0.77 | 0.43 | 0.24 |

| 112 | Eur J Gen Pract | 128 | 0.34 | 0.25 | 0.43 | 0.27 | 0.20 | 0.32 | 0.59 | 0.42 | 0.28 | ||

| 113 | Sao Paulo Med J | 715 | 0.33 | 0.00 | 0.24 | 0.50 | 0.58 | 0.32 | 0.45 | 0.52 | 0.42 | 0.26 | 0.41 |

| 114 | Dis Mon | 148 | 0.33 | 0.66 | 0.22 | 0.11 | 0.21 | 0.27 | 0.24 | 0.25 | 0.32 | 0.39 | |

| 115 | Med Clin North Am | 342 | 0.33 | 0.46 | 0.33 | 0.20 | 0.34 | 0.50 | 0.36 | 0.48 | 0.28 | 0.48 | |

| 116 | Te r A rkh | 1444 | 0.33 | 0.19 | 0.42 | 0.38 | 0.34 | 0.11 | 0.32 | 0.33 | 0.30 | 0.19 | |

| 117 | Dtsch Med Wochenschr | 3164 | 0.31 | 0.35 | 0.36 | 0.27 | 0.27 | 0.31 | 0.26 | 0.30 | 0.27 | 0.32 | 0.22 |

| 118 | Acta Med Port | 133 | 0.30 | 0.25 | 0.35 | 0.31 | 0.72 | 0.53 | 0.04 | 0.32 | 0.83 | ||

| 119 | Niger J Clin Pract | 480 | 0.28 | 0.25 | 0.31 | 0.33 | 0.40 | 0.59 | 0.46 | 0.29 | 0.13 | ||

| 120 | Bull Acad Natl Med | 222 | 0.28 | 0.18 | 0.37 | 0.27 | 0.38 | 0.41 | 0.16 | 0.30 | 0.31 | ||

| 121 | Aust Fam Physician | 2565 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.21 | 0.32 | 0.22 | 0.23 | 0.22 | 0.35 | 0.36 | 0.26 | 0.12 |

| 122 | JNMA J Nepal Med Assoc | 207 | 0.23 | 0.22 | 0.23 | 0.24 | 0.26 | 0.47 | 0.53 | 0.22 | 0.38 | ||

| 123 | Rev Clin Esp (Barc) | 412 | 0.18 | 0.20 | 0.21 | 0.11 | 0.18 | 0.19 | 0.22 | 0.13 | 0.18 | 0.33 | |

| 124 | Aten Primaria | 248 | 0.13 | 0.21 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.04 | 0.12 | 0.05 | 0.14 | 0.18 | ||

| 125 | Gac Med Mex | 482 | 0.11 | 0.27 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.16 | 0.18 | 0.13 | 0.11 | |

| 126 | Rev Med Chil | 78 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.17 | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.16 |

Explanations for the columns: Please see notes to Table 1.

Figure 1.

Relationship between Neophilia Index and Citation Rank for Journals in General and Internal Medicine.

Table 3.

Neophilia Rankings for Journals in Core Clinical Journals.

| (1a) | (1b) | (1c) | (1d) | (2a) | (2b) | (2c) | (2d) | (3a) | (3b) | (3c) | (4a) | (4b) | (5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neophilia Ranking |

Journal | Number of Articles |

Neophilia Index |

1980s | 1990s | 2000s | 2010-2013 | Exclude UMLS Terms in Category Group “Miscellaneo us II” |

Exclude UMLS Terms in Category Groups “Miscellaneo us II” and “Drug” |

Only Include UMLS Terms in Category Groups “Clinical” and “Drug” |

Compare Papers Only within Same Clinical Research Area |

Compare Papers Only within Same Basic Research Area |

N-Gram Approach |

| 1 | Blood | 29049 | 3.38 | 2.92 | 3.98 | 3.76 | 2.85 | 3.57 | 4.13 | 2.24 | 2.03 | 3.19 | 3.61 |

| 2 | J Immunol | 48213 | 3.10 | 2.80 | 3.66 | 3.41 | 2.52 | 3.31 | 3.97 | 1.81 | 2.12 | 3.20 | 3.66 |

| 3 | Med Lett Drugs Ther | 1751 | 3.06 | 1.56 | 2.10 | 4.38 | 4.19 | 3.21 | 0.51 | 2.22 | 2.58 | 2.99 | 0.85 |

| 4 | J Clin Invest | 14724 | 3.04 | 2.54 | 3.19 | 3.63 | 2.80 | 3.23 | 3.83 | 1.61 | 2.35 | 2.96 | 3.39 |

| 5 | Am J Pathol | 11133 | 2.90 | 1.93 | 3.22 | 3.71 | 2.76 | 3.11 | 3.88 | 1.90 | 2.17 | 2.86 | 3.56 |

| 6 | Clin Pharmacol Ther | 4969 | 2.86 | 2.61 | 2.86 | 3.46 | 2.50 | 2.97 | 2.17 | 2.09 | 2.43 | 2.90 | 2.28 |

| 7 | Endocrinology | 22876 | 2.84 | 1.88 | 2.95 | 3.77 | 2.78 | 3.05 | 3.62 | 1.51 | 2.33 | 2.89 | 3.24 |

| 8 | Diabetes | 10222 | 2.42 | 1.66 | 2.21 | 3.08 | 2.74 | 2.59 | 3.00 | 1.33 | 2.02 | 2.28 | 3.02 |

| 9 | Gastroenterology | 11364 | 2.30 | 1.52 | 2.02 | 2.95 | 2.73 | 2.47 | 2.84 | 1.85 | 1.85 | 2.11 | 2.45 |

| 10 | J Infect Dis | 14833 | 2.12 | 1.75 | 2.75 | 2.14 | 1.82 | 2.25 | 2.49 | 2.13 | 1.70 | 2.04 | 2.53 |

| 11 | J Clin Endocrinol Metab | 19147 | 2.07 | 1.72 | 2.12 | 2.35 | 2.09 | 2.20 | 2.46 | 1.51 | 1.93 | 2.04 | 2.22 |

| 12 | J Allergy Clin Immunol | 7589 | 2.01 | 1.61 | 1.88 | 2.35 | 2.19 | 2.12 | 2.24 | 1.73 | 1.66 | 1.96 | 1.79 |

| 13 | Gut | 7354 | 1.98 | 1.42 | 1.85 | 2.15 | 2.51 | 2.10 | 2.41 | 1.68 | 1.70 | 1.88 | 2.12 |

| 14 | Circulation | 20040 | 1.97 | 1.73 | 1.89 | 2.37 | 1.89 | 2.06 | 2.24 | 1.81 | 1.72 | 1.95 | 2.19 |

| 15 | Am Heart J | 10000 | 1.87 | 1.66 | 1.29 | 1.86 | 2.67 | 1.94 | 2.01 | 1.95 | 1.68 | 1.97 | 2.13 |

| 16 | Transl Res | 4065 | 1.87 | 1.55 | 1.68 | 2.06 | 2.18 | 2.05 | 2.35 | 1.68 | 1.67 | 1.85 | 2.34 |

| 17 | J Am Coll Cardiol | 12324 | 1.85 | 1.69 | 1.63 | 1.96 | 2.13 | 1.92 | 2.15 | 1.98 | 1.68 | 1.96 | 2.02 |

| 18 | N Engl J Med | 8765 | 1.80 | 1.54 | 1.78 | 1.84 | 2.05 | 1.87 | 1.69 | 1.60 | 1.69 | 1.77 | 1.71 |

| 19 | J Clin Pathol | 5790 | 1.73 | 1.31 | 2.03 | 1.87 | 1.71 | 1.82 | 2.35 | 1.47 | 1.28 | 1.64 | 1.95 |

| 20 | Cancer | 21480 | 1.73 | 1.58 | 1.46 | 1.86 | 2.00 | 1.75 | 1.84 | 1.60 | 1.23 | 1.61 | 2.07 |

| 21 | Am J Cardiol | 20983 | 1.67 | 1.77 | 1.17 | 1.65 | 2.09 | 1.72 | 1.75 | 1.80 | 1.48 | 1.76 | 1.89 |

| 22 | Am J Ophthalmol | 6200 | 1.59 | 1.63 | 1.57 | 1.56 | 1.60 | 1.66 | 1.66 | 1.60 | 1.46 | 1.49 | 1.60 |

| 23 | Am J Clin Pathol | 5592 | 1.59 | 1.55 | 1.87 | 1.67 | 1.27 | 1.68 | 2.18 | 1.67 | 1.13 | 1.58 | 1.71 |

| 24 | JAMA Ophthalmol | 5441 | 1.57 | 1.84 | 1.55 | 1.43 | 1.48 | 1.65 | 1.62 | 1.46 | 1.42 | 1.48 | 1.12 |

| 25 | JAMA Neurol | 4138 | 1.56 | 1.24 | 1.40 | 1.78 | 1.82 | 1.58 | 1.88 | 1.52 | 1.46 | 1.36 | 1.55 |

| 26 | Am J Respir Crit Care Med | 13238 | 1.52 | 1.21 | 1.41 | 1.74 | 1.72 | 1.59 | 1.87 | 1.45 | 1.54 | 1.61 | 1.90 |

| 27 | Anesthesiology | 8053 | 1.49 | 1.16 | 1.86 | 1.71 | 1.23 | 1.60 | 1.36 | 1.73 | 1.50 | 1.64 | 1.27 |

| 28 | Am J Med | 6304 | 1.47 | 2.38 | 1.80 | 0.88 | 0.83 | 1.44 | 1.29 | 1.47 | 1.33 | 1.50 | 1.59 |

| 29 | Ann Intern Med | 4948 | 1.46 | 1.81 | 1.90 | 1.10 | 1.04 | 1.43 | 1.42 | 1.46 | 1.27 | 1.51 | 1.66 |

| 30 | Dig Dis Sci | 8982 | 1.46 | 1.46 | 1.62 | 1.30 | 1.46 | 1.54 | 1.56 | 1.63 | 1.31 | 1.48 | 1.46 |

| 31 | Neurology | 13742 | 1.44 | 1.38 | 1.56 | 1.47 | 1.36 | 1.46 | 1.69 | 1.46 | 1.40 | 1.37 | 1.23 |

| 32 | Brain | 4528 | 1.44 | 1.09 | 1.39 | 1.57 | 1.71 | 1.50 | 2.00 | 1.47 | 1.45 | 1.52 | 1.37 |

| 33 | Anesth Analg | 9870 | 1.42 | 1.48 | 1.53 | 1.49 | 1.16 | 1.47 | 1.10 | 1.73 | 1.50 | 1.49 | 1.07 |

| 34 | Lancet | 13518 | 1.40 | 1.53 | 1.37 | 1.21 | 1.49 | 1.41 | 1.28 | 1.16 | 1.31 | 1.39 | 1.38 |

| 35 | Heart | 5621 | 1.40 | 1.67 | 0.87 | 1.32 | 1.73 | 1.40 | 1.60 | 1.55 | 1.32 | 1.47 | 1.55 |

| 36 | Surgery | 7120 | 1.34 | 1.40 | 1.47 | 1.49 | 0.99 | 1.42 | 1.69 | 1.33 | 1.17 | 1.19 | 1.61 |

| 37 | Arch Pathol Lab Med | 2981 | 1.34 | 1.32 | 1.42 | 1.34 | 1.26 | 1.37 | 1.80 | 1.46 | 1.12 | 1.24 | 1.53 |

| 38 | Rheumatology (Oxford) | 4682 | 1.33 | 1.06 | 1.26 | 1.46 | 1.55 | 1.35 | 1.48 | 1.27 | 1.17 | 1.35 | 1.69 |

| 39 | JAMA Dermatol | 2750 | 1.30 | 1.63 | 1.52 | 1.30 | 0.73 | 1.30 | 1.20 | 1.29 | 1.18 | 1.30 | 1.01 |

| 40 | Am J Med Sci | 1759 | 1.27 | 1.60 | 1.20 | 1.03 | 1.25 | 1.31 | 1.33 | 1.33 | 1.14 | 1.30 | 1.50 |

| 41 | J Urol | 20274 | 1.27 | 1.26 | 1.24 | 1.44 | 1.12 | 1.27 | 1.47 | 1.25 | 1.13 | 1.20 | 0.95 |

| 42 | Medicine (Baltimore) | 545 | 1.27 | 1.53 | 1.29 | 1.15 | 1.09 | 1.23 | 1.25 | 1.27 | 1.06 | 1.23 | 1.18 |

| 43 | Radiology | 15005 | 1.25 | 1.71 | 1.17 | 1.13 | 0.98 | 1.08 | 1.37 | 1.23 | 1.27 | 1.38 | 1.56 |

| 44 | Postgrad Med | 2486 | 1.24 | 0.71 | 0.87 | 0.90 | 2.49 | 1.27 | 0.78 | 1.20 | 1.12 | 1.28 | 0.78 |

| 45 | Mayo Clin Proc | 2063 | 1.22 | 1.30 | 1.07 | 1.28 | 1.25 | 1.22 | 1.22 | 1.15 | 1.17 | 1.23 | 1.06 |

| 46 | Anaesthesia | 3762 | 1.18 | 1.77 | 1.29 | 0.86 | 0.82 | 1.17 | 0.80 | 1.53 | 1.38 | 1.26 | 0.90 |

| 47 | Ann Surg | 6264 | 1.17 | 1.40 | 1.35 | 1.01 | 0.91 | 1.19 | 1.46 | 1.21 | 1.15 | 1.07 | 1.27 |

| 48 | Crit Care Med | 7796 | 1.16 | 1.27 | 1.31 | 1.18 | 0.87 | 1.16 | 1.35 | 1.40 | 1.40 | 1.24 | 1.07 |

| 49 | JAMA Psychiatry | 2965 | 1.13 | 1.42 | 1.05 | 0.95 | 1.11 | 1.07 | 1.26 | 1.44 | 1.64 | 1.10 | 1.67 |

| 50 | Am J Trop Med Hyg | 8181 | 1.13 | 1.45 | 1.44 | 0.97 | 0.66 | 1.19 | 1.37 | 1.10 | 1.18 | 1.14 | 1.04 |

| 51 | J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg | 9593 | 1.10 | 1.33 | 1.05 | 1.14 | 0.86 | 1.11 | 1.35 | 1.18 | 1.09 | 1.09 | 1.17 |

| 52 | Chest | 13040 | 1.08 | 1.05 | 1.00 | 1.10 | 1.17 | 1.09 | 1.21 | 1.20 | 1.15 | 1.08 | 1.07 |

| 53 | JAMA | 11180 | 1.06 | 1.14 | 1.08 | 1.19 | 0.81 | 1.03 | 1.07 | 0.98 | 1.08 | 1.05 | 1.12 |

| 54 | JAMA Intern Med | 6150 | 1.04 | 1.19 | 1.32 | 0.94 | 0.69 | 1.01 | 1.01 | 1.21 | 1.08 | 1.09 | 1.13 |

| 55 | Am J Obstet Gynecol | 15418 | 1.03 | 1.25 | 1.27 | 0.93 | 0.66 | 1.06 | 1.24 | 1.17 | 1.36 | 1.06 | 0.96 |

| 56 | JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck | Surg3901 | 0.98 | 0.93 | 1.04 | 1.03 | 0.92 | 0.97 | 1.09 | 0.93 | 1.47 | 0.90 | 0.77 |

| 57 | AJR Am J Roentgenol | 11905 | 0.97 | 1.53 | 0.76 | 0.71 | 0.90 | 0.95 | 1.18 | 0.96 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.87 |

| 58 | Ann Thorac Surg | 13423 | 0.95 | 1.06 | 0.89 | 1.09 | 0.77 | 0.97 | 1.20 | 1.03 | 0.96 | 0.94 | 1.03 |

| 59 | Am J Psychiatry | 5123 | 0.95 | 1.11 | 0.93 | 0.90 | 0.84 | 0.89 | 1.06 | 1.34 | 1.44 | 0.95 | 1.50 |

| 60 | J Neurosurg | 7628 | 0.93 | 1.25 | 1.08 | 0.85 | 0.56 | 0.95 | 1.13 | 1.19 | 1.15 | 0.90 | 1.08 |

| 61 | Radiol Clin North Am | 438 | 0.93 | 1.22 | 0.72 | 0.85 | 0.93 | 1.12 | 0.77 | 0.73 | 0.92 | 0.86 | |

| 62 | J Pediatr | 8930 | 0.93 | 1.20 | 1.14 | 0.73 | 0.64 | 0.92 | 1.02 | 1.03 | 1.02 | 0.95 | 0.80 |

| 63 | Br J Radiol | 4001 | 0.92 | 1.20 | 0.77 | 0.82 | 0.87 | 0.90 | 1.10 | 1.00 | 0.93 | 0.98 | 0.93 |

| 64 | Obstet Gynecol | 9525 | 0.90 | 1.21 | 1.06 | 0.67 | 0.67 | 0.92 | 1.10 | 1.14 | 1.23 | 0.97 | 0.65 |

| 65 | Public Health Rep | 1855 | 0.89 | 1.29 | 1.51 | 0.48 | 0.29 | 0.83 | 0.99 | 1.03 | 1.06 | 0.97 | 0.89 |

| 66 | JAMA Surg | 5318 | 0.88 | 1.10 | 1.27 | 0.78 | 0.37 | 0.91 | 1.07 | 1.11 | 0.99 | 0.85 | 0.99 |

| 67 | J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci | 2543 | 0.87 | 0.89 | 0.83 | 0.89 | 0.85 | 1.12 | 0.80 | 0.99 | 0.87 | 1.02 | |

| 68 | Am J Surg | 7776 | 0.87 | 1.01 | 1.09 | 0.86 | 0.51 | 0.87 | 1.03 | 0.93 | 0.89 | 0.83 | 0.69 |

| 69 | Pediatrics | 11217 | 0.84 | 1.09 | 1.06 | 0.74 | 0.49 | 0.81 | 0.88 | 0.95 | 1.10 | 0.88 | 0.64 |

| 70 | Clin Toxicol (Phila) | 1126 | 0.84 | 1.01 | 0.89 | 0.84 | 0.62 | 0.80 | 0.68 | 0.85 | 1.32 | 0.87 | 0.36 |

| 71 | BJOG | 5994 | 0.84 | 1.06 | 0.98 | 0.71 | 0.61 | 0.86 | 0.95 | 0.99 | 1.23 | 0.93 | 0.53 |

| 72 | Plast Reconstr Surg | 8714 | 0.80 | 1.24 | 0.69 | 0.81 | 0.47 | 0.85 | 1.23 | 0.78 | 1.06 | 0.85 | 0.31 |

| 73 | Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol | 3827 | 0.80 | 0.89 | 0.78 | 0.84 | 0.69 | 0.80 | 0.97 | 0.78 | 1.27 | 0.84 | 0.52 |

| 74 | J Trauma Acute Care Surg | 9025 | 0.78 | 1.00 | 0.91 | 0.65 | 0.57 | 0.71 | 0.85 | 0.79 | 1.35 | 0.74 | 0.64 |

| 75 | South Med J | 3295 | 0.78 | 0.92 | 1.01 | 0.45 | 0.74 | 0.77 | 0.86 | 0.96 | 0.85 | 0.78 | 0.77 |

| 76 | CMAJ | 3449 | 0.75 | 1.01 | 0.67 | 0.63 | 0.70 | 0.71 | 0.74 | 0.68 | 0.83 | 0.74 | 0.74 |

| 77 | Am J Clin Nutr | 10212 | 0.74 | 0.72 | 0.49 | 0.76 | 0.98 | 0.73 | 0.92 | 0.67 | 0.88 | 0.71 | 0.82 |

| 78 | Ann Emerg Med | 3320 | 0.74 | 0.98 | 0.70 | 0.76 | 0.50 | 0.67 | 0.72 | 0.84 | 1.08 | 0.78 | 0.57 |

| 79 | Br J Surg | 7973 | 0.71 | 0.97 | 0.79 | 0.60 | 0.48 | 0.72 | 0.87 | 0.86 | 0.79 | 0.68 | 0.70 |

| 80 | Arch Phys Med Rehabil | 5926 | 0.71 | 0.92 | 0.82 | 0.51 | 0.57 | 0.52 | 0.66 | 0.65 | 1.07 | 0.79 | 0.43 |

| 81 | J Am Coll Surg | 5705 | 0.70 | 0.82 | 0.84 | 0.75 | 0.39 | 0.72 | 0.89 | 0.84 | 0.82 | 0.67 | 0.64 |

| 82 | Am J Public Health | 5678 | 0.70 | 0.94 | 1.03 | 0.43 | 0.41 | 0.67 | 0.83 | 0.69 | 0.78 | 0.75 | 0.84 |

| 83 | Hosp Pract (1995) | 1172 | 0.68 | 0.27 | 0.53 | 0.00 | 1.94 | 0.72 | 0.57 | 0.65 | 0.62 | 0.95 | 0.64 |

| 84 | Clin Orthop Relat Res | 10324 | 0.66 | 0.91 | 0.55 | 0.52 | 0.66 | 0.66 | 0.83 | 0.74 | 1.08 | 0.65 | 0.38 |

| 85 | Bone Joint J | 5744 | 0.65 | 0.69 | 0.42 | 0.61 | 0.85 | 0.64 | 0.81 | 0.66 | 1.04 | 0.64 | 0.25 |

| 86 | Arch Dis Child | 5844 | 0.64 | 0.90 | 0.64 | 0.44 | 0.58 | 0.60 | 0.69 | 0.72 | 0.77 | 0.69 | 0.44 |

| 87 | J Nerv Ment Dis | 1728 | 0.62 | 1.26 | 0.69 | 0.38 | 0.15 | 0.46 | 0.56 | 0.73 | 1.10 | 0.67 | 0.73 |

| 88 | BMJ | 7656 | 0.62 | 0.88 | 0.69 | 0.44 | 0.47 | 0.57 | 0.54 | 0.64 | 0.71 | 0.66 | 0.51 |

| 89 | J Bone Joint Surg Am | 6353 | 0.61 | 0.77 | 0.63 | 0.53 | 0.51 | 0.60 | 0.79 | 0.73 | 1.14 | 0.61 | 0.39 |

| 90 | Phys Ther | 2062 | 0.59 | 0.84 | 0.61 | 0.57 | 0.35 | 0.47 | 0.69 | 0.64 | 0.97 | 0.67 | 0.23 |

| 91 | Am Fam Physician | 2238 | 0.58 | 0.68 | 0.68 | 0.51 | 0.45 | 0.58 | 0.47 | 0.70 | 0.61 | 0.59 | 0.40 |

| 92 | JAMA Pediatr | 2100 | 0.58 | 0.71 | 0.58 | 0.45 | 0.53 | 0.62 | 0.79 | 0.93 | 0.63 | 0.44 | |

| 93 | J Fam Pract | 2268 | 0.57 | 0.76 | 0.70 | 0.65 | 0.19 | 0.54 | 0.51 | 0.64 | 0.74 | 0.64 | 0.41 |

| 94 | Am J Phys Med Rehabil | 1690 | 0.57 | 0.47 | 1.04 | 0.34 | 0.44 | 0.46 | 0.52 | 0.52 | 0.94 | 0.67 | 0.39 |

| 95 | CA Cancer J Clin | 334 | 0.56 | 0.46 | 0.56 | 0.45 | 0.78 | 0.57 | 0.53 | 0.56 | 0.40 | 0.57 | 0.48 |

| 96 | Nurs Outlook | 95 | 0.56 | 0.44 | 0.88 | 0.35 | 0.39 | 0.52 | 0.39 | 0.72 | 0.77 | 0.29 | |

| 97 | J Laryngol Otol | 3754 | 0.55 | 0.50 | 0.58 | 0.62 | 0.49 | 0.56 | 0.65 | 0.61 | 0.95 | 0.53 | 0.20 |

| 98 | Acad Med | 516 | 0.53 | 0.86 | 0.63 | 0.32 | 0.31 | 0.45 | 0.54 | 0.25 | 0.32 | 0.42 | 0.57 |

| 99 | J Oral Maxillofac Surg | 4855 | 0.51 | 0.63 | 0.45 | 0.45 | 0.50 | 0.53 | 0.62 | 0.72 | 1.14 | 0.49 | 0.41 |

| 100 | Clin Pediatr (Phila) | 1934 | 0.49 | 0.86 | 0.37 | 0.45 | 0.29 | 0.50 | 0.55 | 0.62 | 0.68 | 0.53 | 0.35 |

| 101 | Heart Lung | 1253 | 0.49 | 0.56 | 0.50 | 0.38 | 0.51 | 0.41 | 0.53 | 0.59 | 0.57 | 0.53 | 0.47 |

| 102 | Surg Clin North Am | 601 | 0.48 | 0.45 | 1.01 | 0.00 | 0.50 | 0.55 | 0.53 | 0.70 | 0.45 | 0.75 | |

| 103 | Arch Environ Occup Health | 1547 | 0.46 | 0.70 | 0.45 | 0.41 | 0.28 | 0.43 | 0.57 | 0.38 | 0.78 | 0.45 | 0.38 |

| 104 | J Acad Nutr Diet | 4114 | 0.42 | 0.75 | 0.35 | 0.34 | 0.23 | 0.34 | 0.45 | 0.36 | 0.66 | 0.56 | 0.22 |

| 105 | Nurs Res | 1004 | 0.42 | 0.81 | 0.38 | 0.22 | 0.25 | 0.35 | 0.47 | 0.59 | 0.77 | 0.52 | 0.38 |

| 106 | Orthop Clin North Am | 653 | 0.40 | 0.76 | 0.61 | 0.22 | 0.00 | 0.39 | 0.50 | 0.34 | 0.78 | 0.52 | 0.29 |

| 107 | Nurs Clin North Am | 498 | 0.37 | 0.66 | 0.31 | 0.41 | 0.12 | 0.20 | 0.32 | 0.38 | 0.57 | 0.41 | 0.33 |

| 108 | Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal | Ed 1456 | 0.36 | 0.57 | 0.36 | 0.16 | 0.37 | 0.41 | 0.55 | 0.69 | 0.38 | 0.32 | |

| 109 | Dis Mon | 148 | 0.33 | 0.66 | 0.22 | 0.11 | 0.21 | 0.27 | 0.24 | 0.25 | 0.32 | 0.39 | |

| 110 | Med Clin North Am | 342 | 0.33 | 0.46 | 0.33 | 0.20 | 0.34 | 0.50 | 0.36 | 0.48 | 0.28 | 0.48 | |

| 111 | Pediatr Clin North Am | 415 | 0.33 | 0.30 | 0.20 | 0.49 | 0.26 | 0.32 | 0.36 | 0.46 | 0.34 | 0.30 | |

| 112 | J Nurs Adm | 194 | 0.28 | 0.18 | 0.24 | 0.52 | 0.19 | 0.11 | 0.24 | 0.33 | 0.36 | 0.27 | 0.33 |

| 113 | Am J Nurs | 1837 | 0.22 | 0.29 | 0.16 | 0.14 | 0.29 | 0.20 | 0.21 | 0.23 | 0.26 | 0.20 | 0.12 |

| 114 | Hosp Health Netw | 544 | 0.22 | 0.34 | 0.21 | 0.32 | 0.00 | 0.18 | 0.20 | 0.11 | 0.15 | 0.20 | 0.15 |

| 115 | J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc | Sci 929 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.15 | 0.36 | 0.12 | 0.10 |

Explanations for the columns: Please see notes to Table 1.

In each table, columns 1d and 1a, respectively, show the neophilia index and the corresponding neophilia ranking for the baseline specification. Column 1b shows the journal name (MEDLINE abbreviation) and column 1c shows the number of original research articles published during 1980-2013 based on which the neophilia index shown in column 1d was calculated. Columns 2-5 show the results for the four sets of sensitivity analyses. Entries in each table are color coded, with reddish hues indicating a high propensity to publish articles that mention novel terms relative to the average paper and blue indicating the lowest propensity.

Table 1 shows the neophilia ranking for 10 highly cited medical journals. To construct this table, we calculated the neophilia index for the 10 most cited journals that are both ranked by TR in the General and Internal Medicine journal category and for which data is available in MEDLINE to construct the neophilia index. The highly cited status is determined based on TR impact factors in 2013.10 These 10 journals are among the most prestigious English language medical journals.

Among these 10 highly cited medical journals, the New England Journal of Medicine (N Engl J Med) ranks at the top of our neophilia index. The number 1.81 in the top row of column 1d indicates that over the period 1980 to 2013, the New England Journal of Medicine was 81% more likely to publish articles that mention novel ideas compared to the average article published in the General and Internal Medicine journal set. By contrast, out of these 10 journals, the British Medical Journal (BMJ) was less likely to publish articles that mention new terms than the typical journal in this set during this period.

Overall, several features stand out from the results reported in Table 1. First, these highly cited journals vary considerably in their propensity to publish articles that try out new ideas. For the two journals with the highest neophilia indices in column 1d — the New England Journal of Medicine and BMC Medicine (BMC Med) — the neophilia index is more than twice as large as the neophilia index is for either of the two journals with the lowest neophilia index — the British Medical Journal and the Canadian Medical Association Journal (CMAJ). Prestigious high-influence journals are not equal in terms of their propensity to reward innovative science.

Second, while eight out of the ten prestigious journals have a higher than average propensity to publish articles that try out new ideas (that is, the neophilia index in column 1d is above 1.0 for eight journals in Table 1), at the same time, two of these journals have a lower than average propensity to publish articles that try out new. Being a prestigious high-influence journal does not automatically imply that the journal encourages innovative science.

Third, for most of these journals the neophilia index and the corresponding neophilia ranking remain relatively stable over time. This is shown by the time-period specific neophilia indices reported in columns 2a-2d of Table 1. That said, some changes over time are apparent. For instance, the neophilia index for the New England Journal of Medicine has increased substantially from 1980s to 2010s (from 1.54 to 2.06). On the other hand, for Annals of Internal Medicine (Ann Intern Med) the neophilia index has changed from well-above average to merely average (from 1.81 to 1.04), and the neophilia indices for the British Medical Journal and the Canadian Medical Association Journal have fallen from average to well-below average (from 1.01 to 0.70, and from 0.88 to 0.47, respectively). It is also interesting to note that one relatively new journal, BMC Medicine, fares so well in the rankings, but another, PLoS Medicine, appears to be struggling in recent years after initially succeeding in publishing innovative work.

Fourth, for most journals the neophilia index and the corresponding neophilia ranking remain robust to the sensitivity analyses that are reported in columns 3a-3c, 4a-4b, and 5 of Table 1. The neophilia indices reported in columns 3a-3c rely on different subsets of UMLS terms, such as the set that excludes novel pharmaceutical terms (column 3b). The neophilia indices reported in columns 4a and 4b in turn control for the propensity to publish in hot clinical research areas or in hot basic science areas, respectively. These adjustments have only small effects on the relative rankings of these top 10 journals in our neophilia index. This consistency with our main results is not surprising given that these general interest journals tend to publish papers from a broad set of areas, not just drug trials or particular hot clinical or basic science fields. Finally, the neophilia indices reported in column 5 show that the rankings are robust to using the alternative n-gram based approach in place of the UMLS thesaurus approach used in the baseline specification.

We now turn our attention to Table 2, which lists the neophilia index and the corresponding ranking for all 126 journals in the General and Internal Medicine category. We have indicated in bold those journals which are also present in Table 1. The top ranked journals in Table 2 are Current Medical Research and Opinion, the American Journal of Chinese Medicine, and Translational Research, none of which rank among the top 10 based on citations. This indicates that our neophilia rankings and citations-based impact factor rankings capture different aspects of science. The fact that Translational Research and Journal of Investigative Medicine are highly ranked in our neophilia rankings (3rd and 13th, respectively) is reassuring because these journals strive to promote the very thing that our measure seeks to capture — innovative science that builds on new ideas (the journals aim to translate new ideas in ways that benefit patient health).

Columns 2a-2d of Table 2 show that also for this broad set of journals, the neophilia index remains relatively stable over time. This stability implies that the neophilia rankings during any given time period are not random; to a significant degree the rankings are the result of variations in editorial policies across journals. We return to this issue below in the Discussion section.

Columns 3a-3c of Table 2 in turn show that, with some exceptions, the neophilia rankings are independent of the set of UMLS terms that are included in the analysis. One such exception concerns the exclusion of terms in the “Drug” category from the analysis (column 3b): unsurprisingly this dramatically lowers the neophilia index for journals that are mainly focused on research on effects of new pharmaceutical agents. Such journals include Current Medical Research and Opinion and International Journal of Clinical Practice (rows 1 and 8).

Columns 4a-4d of Table 2 show that the neophilia rankings are stable to selecting narrower comparison groups in determining which articles build on new ideas. Finally, column 5 shows that the neophilia rankings remain robust to constructing the neophilia index based on appearance of new n-grams rather than based on the appearance of new UMLS terms. 11

We now turn to the results shown in Figure 1 on the link between our neophilia index and the traditional citation-based impact factor rankings. The scatterplot shows for each journal in the General and Internal Medicine category the journal's citation based impact factor ranking in 2013 (horizontal axis) against the journal's neophilia index for the 1980-2013 period (vertical axis). The figure also shows the least squares regression line for these observations.

The scatterplot and the regression line shown in Figure 1 demonstrate that more cited journals generally have also a higher neophilia index (p < 0.01).12 There is, however, considerable variation around this regression line, with some less cited journals faring very well on our neophilia index, and some highly cited journals appearing relatively averse to publishing papers that build on fresh ideas. Our earlier results showing the strong persistence in the neophilia index over time (Table 1 and Table 2) implies that to a significant degree this variation around the regression line reflects genuine and persistent differences in editorial policies across journals. That the relationship between the citation ranking and our neophilia index is not monotonic implies that the neophilia index captures an aspect of scientific progress that is not captured by citations. The neophilia index thus has value as an additional input to science policy.

We next turn our attention to results in Table 3, which reports neophilia rankings for the journal set Core Clinical Journals. This set includes general medical journals and specialized field journals.13 Journals that are also present in Table 1 are indicated in bold. The most neophilic journals on this list are Blood, the Journal of Immunology, and Medical Letters on Drugs and Therapeutics, showing that no field dominates over others in terms of the propensity to try out new ideas. The same observation is supported by scrolling further down the list; no field appears to have an obvious domination over others in terms of having more journals closer to the top.

In the rankings of Table 3, there are 17 specialized journals above the most neophilic general medical journal (the New England Journal of Medicine), and there are even many more specialized journals above another highly cited general medical journal (the British Medical Journal, ranked 88th). Thus, while general medical journals are usually viewed as more prestigious, field journals play an important role in promoting the trying out of new ideas in medicine. Neither type of medical journal appears to have a monopoly in this regard.

The results across the different columns of Table 3 follow the pattern that is familiar from Tables 1 and 2. First, there is a lot of variation in the neophilia index across journals. Second, the neophilia index is stable over time, though some variation exists. The journal Hospital Practice (row 83) is an extreme outlier in this regard. But the sudden change its neophilia index is not unexpected as it published no articles during 2002-2008; when the journal was brought back to life it followed very different editorial practices compared to its previous incarnation. Third, the neophilia index is generally robust to employing a different set of UMLS terms in the analysis. One exception to this robustness is that excluding terms in the “Drug” category group leads journals such as Medical Letters on Drugs and Therapeutics and Anesthesia and Analgesia (rows 3 and 33, respectively) to fall quite dramatically in the rankings. Because these journals focus on research on new drug compounds, this is not a surprising finding. In fact, it acts as a check on the validity of our methods. Finally, the neophilia index is insensitive to choosing narrower comparison sets and to employing the n-gram approach over the UMLS thesaurus approach.

4. Discussion

We organize our discussion in a series of eight short observations about the nature of medical publishing, speculation about causes, some suggestions for future research, and implications for science policy implied by our analysis.

4.1 Highly cited journals tend to publish innovative work in medicine

The comparison of our neophilia ranking against the citation based ranking indicates that, on average, highly cited prestige journals in biomedicine actually do a good job in promoting innovative science. This result is surprising in one regard. One might think that lower ranked journals would attempt to distinguish themselves by seeking novelty. One possible explanation for this surprising finding is our focus on medicine, rather than other scientific disciplines. By focusing on medicine, we have selected the area of science that may be most disciplined by the practical usefulness of its findings. This discipline may lead prestige journals to be less likely influenced by citation-oriented rankings, and to seek out innovative work that will affect the treatment of patients. Hence, when our neophilia index is exported to other fields, we might expect different results. Furthermore, we should be careful about what to expect given the nature of the coordination problem mentioned in the Introduction. This problem causes journals to publish less innovative science than they would absent the problem — it does not necessarily make less influential journals more likely to publish innovative work.

4.2 Less prestigious journals also serve a role as an outlet for innovative work

While we find that, on average, journals that rank high on citation-based rankings tend to do well also in our neophilia ranking, knowing the impact factor alone does not automatically predict the position in the neophilia-based index. While the link between citation-based rankings and the neophilia index is positive, it is not a one-to-one relationship. For example, we found that some prestigious highly cited medical journals have even a below average neophilia score. Furthermore, many medium-ranked journals appear to play an important role in medical science by serving as an outlet for innovative work that — for whatever reason — is not poised to draw many citations from others in a field. Moreover, neither general medical journals nor specialized field journals dominate over one another in publishing innovative work.

One implication of these results is that focusing on impact factors alone does not provide appropriate incentives for journals to publish innovative work in biomedicine. Hence, it is important to devise and utilize metrics such as our neophilia ranking that can provide quantitative guidance on this dimension.

4.3 There is a need to measure other forms of novelty too

The reason we focus on measuring novelty based on the use of new ideas — instead of the novelty of a combination — is two-fold. First, we want to consider a more comprehensive set of idea inputs than is typically considered in studies that examine the novelty of a combination. For example, Foster et al. (2015) and Rzhetzky et al. (2015) measure the novelty of a combination based on mentions of approximately 50,000 chemicals, whereas we measure novelty based on mentions of approximately 5,000,000 terms that obviously capture a much broader set of idea inputs than just chemicals. For computational reasons, there is a sharp tradeoff in terms of how many idea inputs one can consider when measuring combinatorial novelty.

Second, while work on new combinations is important too, work that builds on new ideas is arguably even more important. For science without new ideas — science that relentlessly pursues new combinations of relatively old ideas — eventually becomes stagnant science. The trying out of new ideas is crucial for avoiding stagnation: new ideas are raw and poorly understood when they are born (Kuhn 1962) and thus need a lot of attention by many scientists before they can develop into transformative ideas. With this in mind, the proposed neophilia ranking of scientific journals provides a quantitative tool for those institutions and funding agencies that wish to reward scientists who are willing to try out and further develop these new ideas in their work.

4.4 The race to publish innovative papers is a feature, not a bug

One possible critique of taking the neophilia index seriously is that it might lead a journal to publish work that builds on new ideas simply for the sake of improving its neophilia score, even when the editors do not view the innovative work as particularly important in the field. Propagating the neophilia index, under this reasoning, may create incentives on the part of journals to game the index by distorting publication decisions in order to improve a journal's position. In our view, this is a benefit arising from the neophilia index, rather than an unintended harm. We want journals to compete to publish work that elaborates on newer ideas because it makes science healthier: prior theoretical work suggests that absent such an incentive scientists underinvest in innovative science. Furthermore, one can tweak the index in many ways depending on the purpose; for instance, one can construct the index only based on ideas that have stood the test of time or based on ideas that exceed some popularity threshold.

4.5 The threat of gaming mirrors the threat of gaming citation-based rankings