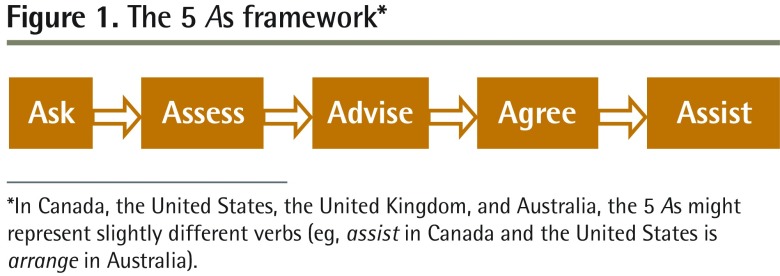

Family doctors are often involved in assisting patients with behaviour change. The 5 As framework has become the universal approach to teaching and practising the art of encouraging behaviour change (Figure 1).1 It is championed for its simplicity and easy-to-remember acronym. In Australia, it is applied within general practice in the prevention guidelines for smoking, nutrition, alcohol, and physical activity advice.2

Figure 1.

The 5 As framework*

*In Canada, the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia, the 5 As might represent slightly different verbs (eg, assist in Canada and the United States is arrange in Australia).

The 5 As model originates from the US Department of Health and Human Services, where it was developed as a framework for encouraging smoking cessation.3 The framework is informed by the transtheoretical model of behaviour change first proposed by Prochaska and DiClemente.4 Its strength is in taking the individual perceived need as the starting point, which makes it possible to direct the process of care toward the patient and his or her personal situation. Since being developed specifically for smoking cessation, the model’s approach has been transferred to obesity management.1,5 This model has served well as an initial descriptor of a process that occurs between a clinician and patient for behaviour change. However, the 5 As model could be further developed to reflect more explicitly the complexity of patient behaviour change in obesity management.

Further development of an existing approach

The linear, sequential 5 As model implies that assisting patients in behaviour change is a streamlined and straightforward process; however, this misinforms both learners and experienced clinicians, as assisting behaviour change is perhaps the most complicated task that a clinician can undertake. It is not simple to help a person identify changes he or she wants to make to his or her behaviour, and it is even more complex to determine appropriate goals for the person and how changes should be implemented. The current 5 As model does not explicitly acknowledge that some patients will not be ready to progress into the assessment phase and that this should be respected. A model that better reflects the complexities of behaviour change is needed.

The 5 As model has been a helpful approach in starting to understand the process for behaviour change. However, the simplistic representation of the process has led some research and teaching to suggest that a stepwise progression through the 5 As for each patient is needed. Experts in the field are aware that this was not the intention of the developers of the model. But the representation of the model with the 5 As does not make this clear for the learner or non-expert in behaviour change. To further develop research and teaching in this area, we suggest the following changes to the representation of the 5 As model:

using patient-centred language,

taking a person-centred approach, and

acknowledging the importance of a strong therapeutic relationship.

Patient-centred language

The importance of patient-centred language in clinical practice has been linked to patient satisfaction and better communication outcomes.6 Overall, the 5 A verbs in the model are not collaborative or patient-centred—they describe processes that you “do to” someone rather than “do with” someone. When the 5 As in obesity care are particularized, the description is collaborative and reflective of motivational interviewing processes.1 For example, the ask phase of the 5 As model might be better represented by seek permission. This clearly conveys the expectation of the initial phase of the process. The simple A verbs do not convey the importance of partnership in the process, and the model would be improved with the use of more collaborative verbs.

Person-centredness

Person-centredness is a concept that was fully explained by Starfield in 2011.7 She described person-focused care as a unique concept that was different from patient-centred care. With person-focused care,8,9 the care of a person takes place over time, with a focus on the whole person rather than interrelated disease processes, and the person’s health beliefs, cultural values, and lived experiences become central to the management planning. A person’s experience of health care and his or her sense of well-being is the primary outcome of all care. Placing person-centredness at the core of a modified 5 As model highlights the importance of this approach when we are aiming to improve a person’s sense of his or her own health. This is principally important, as person-centredness has been related to positive health outcomes.10

Studies in primary health care that correlate consultations with the 5 As process are described as successful only if the practitioner discusses every stage of the 5 As.11 Studies have repeatedly noted that practitioners most often ask and assess, but less frequently move to the advise, agree, and arrange or assist phases.12 This simplified view of the process does not recognize that for some patients, moving beyond the initial phases in a consultation is not appropriate. This view also overlooks that conversations about change do not need to occur in one consultation. Change over time is recognized in some research13 but not all, and is often overlooked when attempting to simplify the process when teaching learners. If a patient does not wish to discuss obesity or there are other more pressing concerns, the practitioner could be practising excellent, person-centred health care by not moving forward into further phases.

Therapeutic relationship

The therapeutic relationship between a practitioner and client has been well recognized in psychotherapy as a mediator for behaviour change.14 A strong therapeutic relationship is seen when there is mutual respect between the parties, an ability to collaborate on goal setting, and agreement on the best way to achieve the goals.15 There are increasing examples in the medical literature of a strong therapeutic relationship being associated with better patient outcomes.16 The 5 As model could be improved with the recognition of the all-encompassing nature of a strong therapeutic alliance in assisting patients in behaviour change. The current model does not include this concept and gives the impression that anyone could ask, assess, advise, and arrange with the same success in patient behaviour change. This approach is unlikely to be true.17

The current 5 As framework is not reflective of continuity of care that is central to primary care. A strong therapeutic relationship bridges time in that it allows individuals to adapt to the challenges in their lives, recognize their priorities, and temporarily (or permanently) decline to pursue an intervention. Continuity of care is associated with improved uptake of preventive care such as lifestyle interventions.18 A model that more closely reflects the strengths of primary care, using continuity of care and person-centredness, is likely to better reflect the needs of the individual rather than the constraints of a framework.

Proposed model

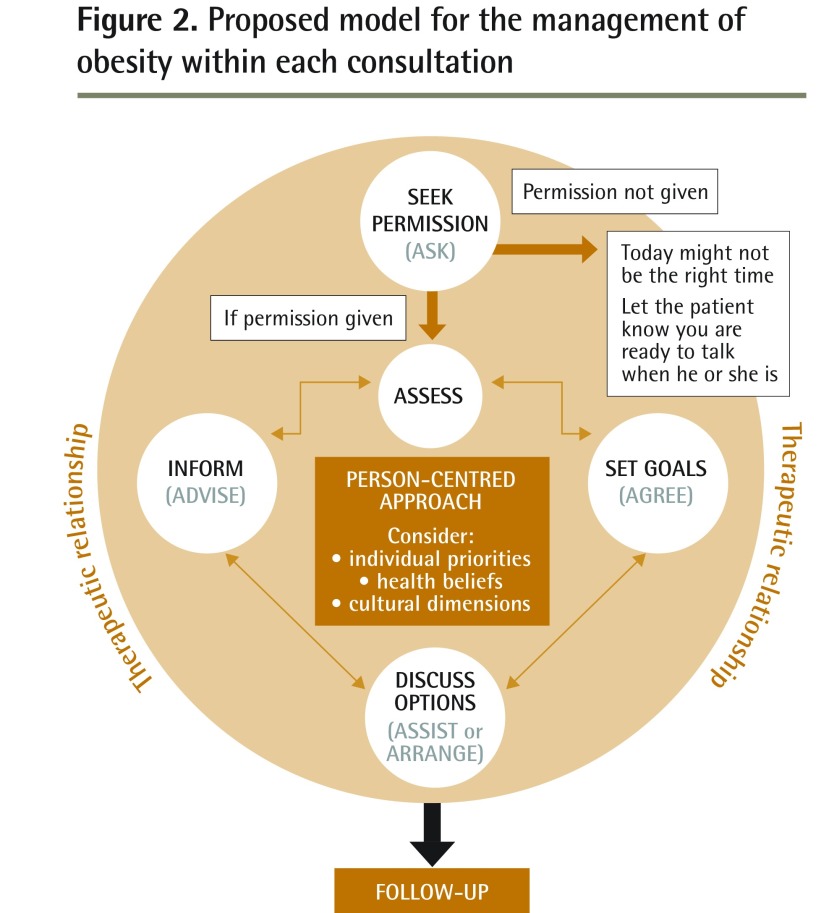

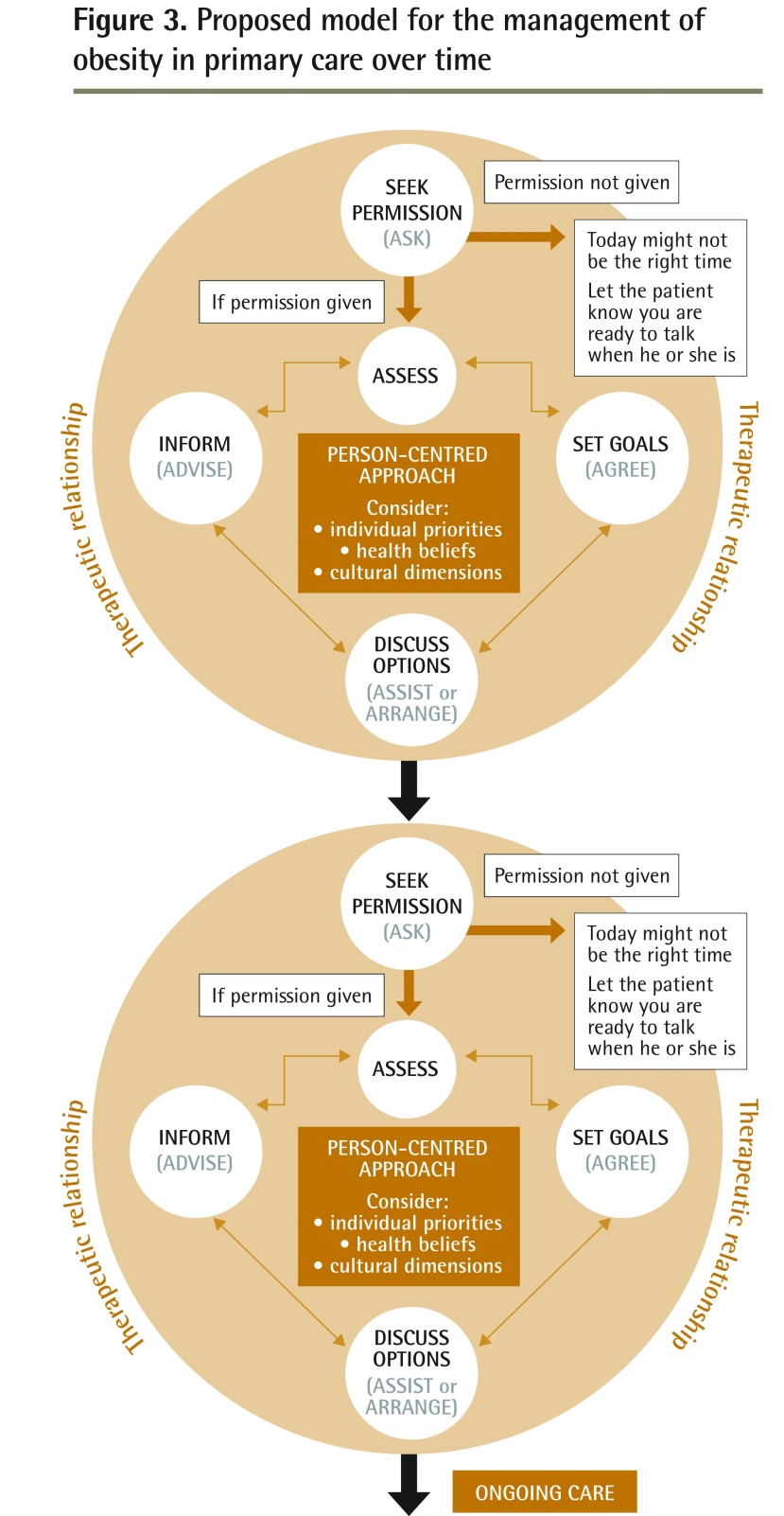

The 5 As model could be made circular to better align with the real complexities of patient behaviour change (Figure 2). The proposed model is encased in the therapeutic relationship recognizing the important strength this brings in patient behaviour change. Replacing A verbs with actions that are more collaborative and person-centred (eg, set goals) is aligned with current theories of patient-centred care and shared decision making. Explicitly outlining the good practice of desisting in the process if a patient does not give permission is essential. Person-centredness is the centrepiece of the model, acknowledging the fundamental role of this value. By adding the follow-up phase, along with a view of the model over time (Figure 3), it is explicit that the journey with a patient through behaviour change occurs over time, at a pace that suits the patient’s needs.

Figure 2.

Proposed model for the management of obesity within each consultation

Figure 3.

Proposed model for the management of obesity in primary care over time

Conclusion

Moving away from a linear, simplified model will better recognize the truly complex nature of assisting patients in behaviour change. It is not necessarily a “failure” when a consultation does not progress through all 5 stages of the 5 As framework and this should be reflected in ongoing research in obesity care. By presenting the 5 As without reference to the patient’s context, it has at times, in research and teaching, been used as a simple “tick box” list. By connecting the 5 As to person-centredness, more justice is done to the underlying strength of the transtheoretical model of behaviour change and the actions of the 5 As are explicitly connected to the values of primary care. This modified model of the 5 As could be used to inform future obesity research and teaching on supporting patient behaviour change in primary care.

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

La traduction en français de cet article se trouve à www.cfp.ca dans la table des matières du numéro de juillet 2017 à la page e330.

Competing interests

None declared

The opinions expressed in commentaries are those of the authors. Publication does not imply endorsement by the College of Family Physicians of Canada.

References

- 1.Vallis M, Piccinini-Vallis H, Sharma AM, Freedhoff Y. Modified 5 As. Minimal intervention for obesity counseling in primary care. Can Fam Physician. 2013;59:27–31. (Eng), e1–5 (Fr). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sim MG, Wain T, Khong E. Influencing behaviour change in general practice. Part 1—brief intervention and motivational interviewing. Aust Fam Physician. 2009;38(11):885–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tobacco Use and Dependence Guideline Panel . Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. Stages and processes of self-change in smoking: toward an integrative model of change. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1983;51(3):390–5. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.51.3.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rao G. Office-based strategies for the management of obesity. Am Fam Physician. 2010;81(12):1449–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.King A, Hoppe RB. “Best practice” for patient-centered communication: a narrative review. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;5(3):385–93. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-13-00072.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Starfield B. Is patient-centered care the same as person-focused care? Perm J. 2011;15(2):63–9. doi: 10.7812/tpp/10-148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mezzich J, Snaedal J, van Weel C, Heath I. Toward person-centered medicine: from disease to patient to person. Mt Sinai J Med. 2010;77(3):304–6. doi: 10.1002/msj.20187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reeve J, Dowrick CF, Freeman GK, Gunn J, Mair F, May C, et al. Examining the practice of generalist expertise: a qualitative study identifying constraints and solutions. JRSM Short Rep. 2013;4(12):1–9. doi: 10.1177/2042533313510155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stewart M, Brown JB, Donner A, McWhinney IR, Oates J, Weston WW, et al. The impact of patient-centered care on outcomes. J Fam Pract. 2000;49(9):796–804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sherson EA, Yakes Jimenez E, Katalanos N. A review of the use of the 5 A’s model for weight loss counselling: differences between physician practice and patient demand. Fam Pract. 2014;31(4):389–98. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmu020. Epub 2014 Jun 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alexander SC, Cox ME, Boling Turer CL, Lyna P, Østbye T, Tulsky JA, et al. Do the five A’s work when physicians counsel about weight loss? Fam Med. 2011;43(3):179–84. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schlair S, Moore S, McMacken M, Jay M. How to deliver high-quality obesity counseling in primary care using the 5As framework. J Clin Outcomes Manag. 2012;19(5):221–9. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bachelor A, Horvath A. The therapeutic relationship. In: Hubble MA, Duncan BL, Miller SD, editors. The heart and soul of change. What works in therapy. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1999. pp. 133–77. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bordin ES. The generalizability of the psychoanalytic concept of the working alliance. Psychother Theory Res Prac. 1979;16(3):252–60. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bennett WL, Wang NY, Gudzune KA, Dalcin AT, Bleich SN, Appel LJ, et al. Satisfaction with primary care provider involvement is associated with greater weight loss: results from the practice-based POWER trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2015;98(9):1099–105. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2015.05.006. Epub 2015 May 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kelley JM, Kraft-Todd G, Schapira L, Kossowsky J, Riess H. The influence of the patient-clinician relationship on healthcare outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e94207. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gray DP, Evans P, Sweeney K, Lings P, Seamark D, Seamark C, et al. Towards a theory of continuity of care. J R Soc Med. 2003;96(4):160–6. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.96.4.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]