Abstract

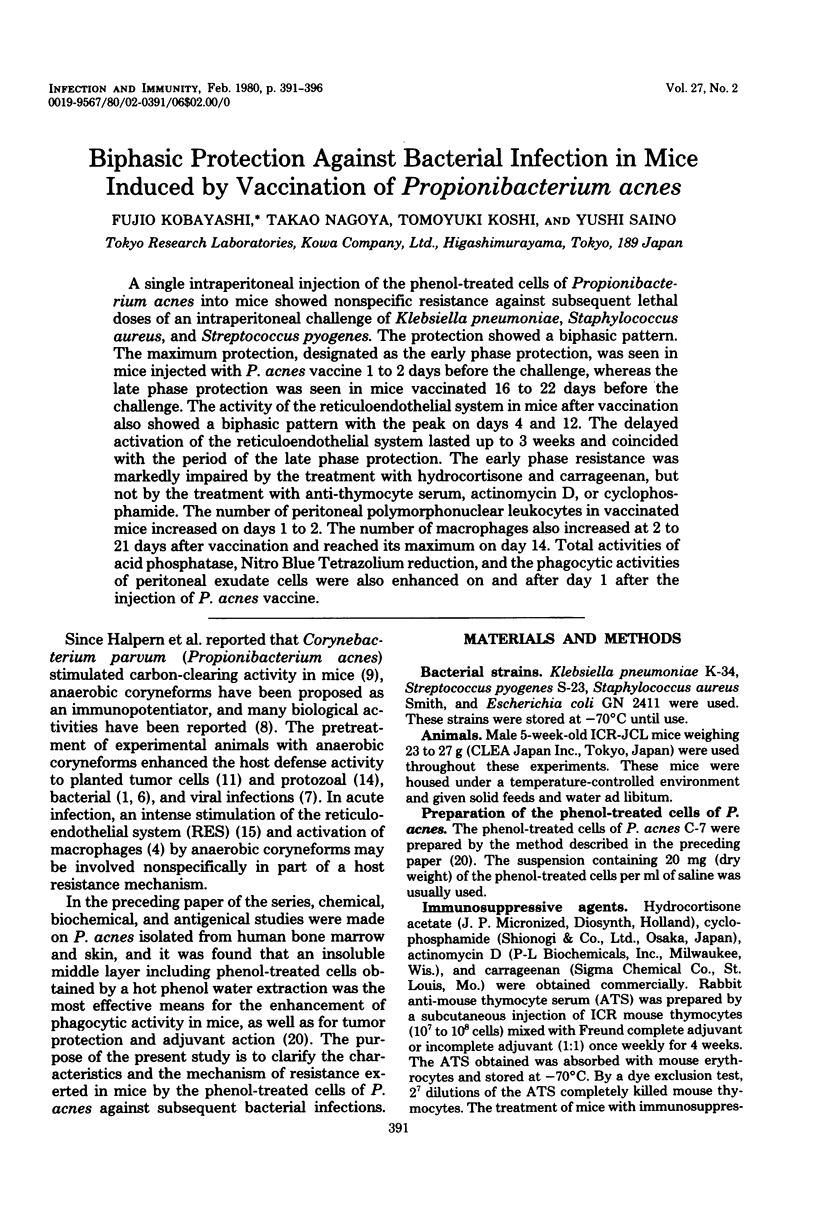

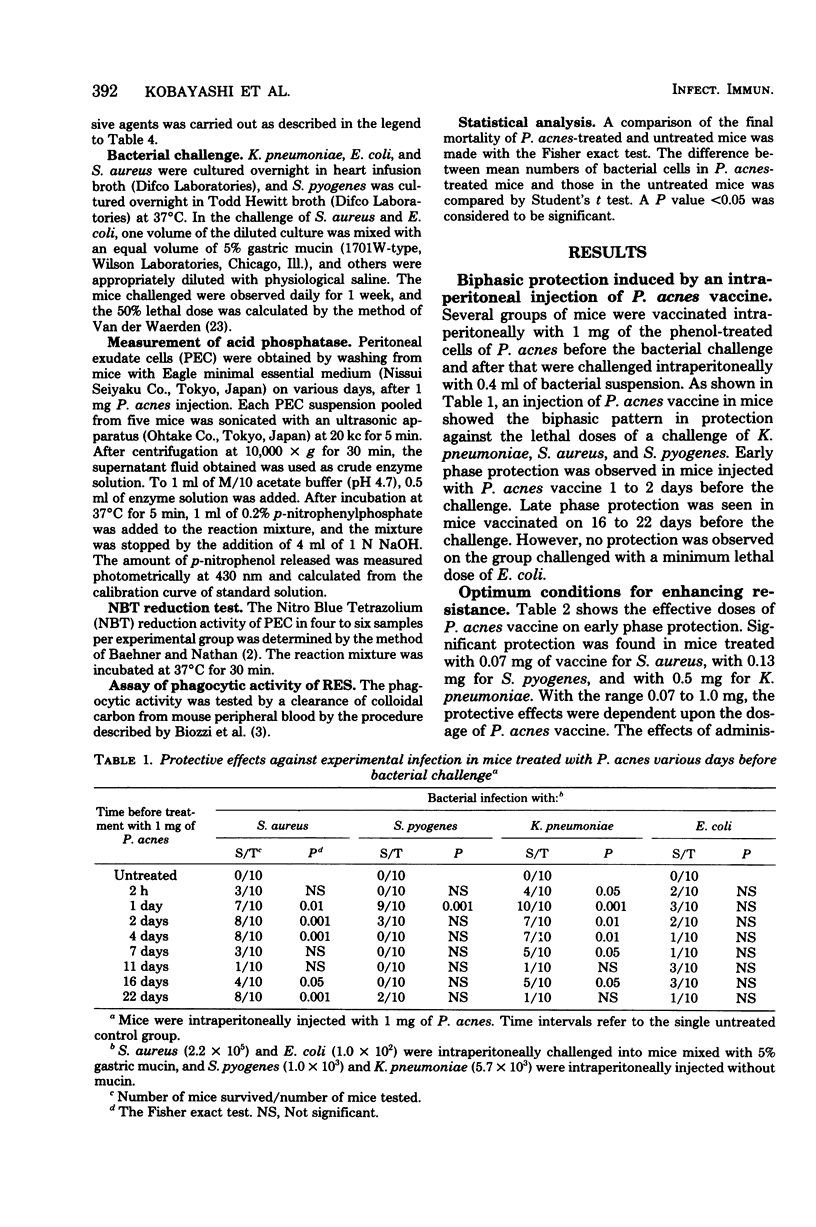

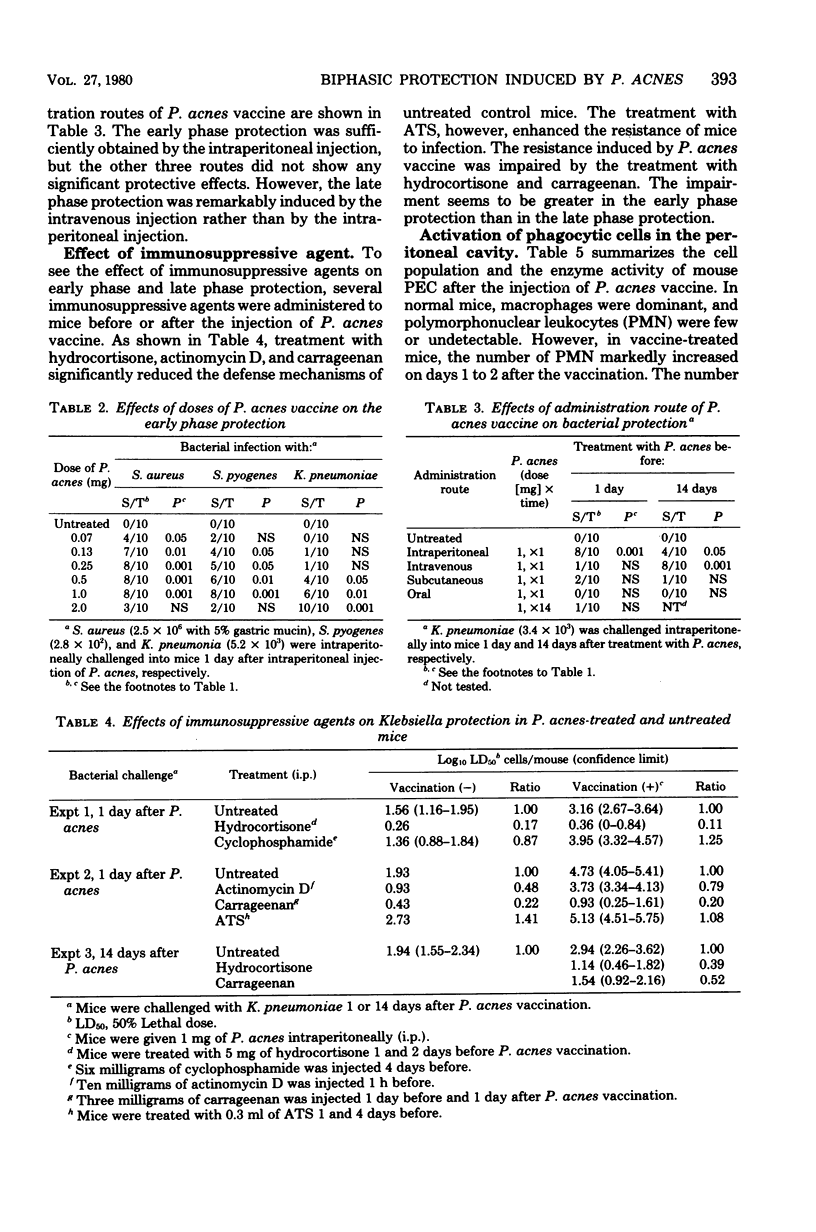

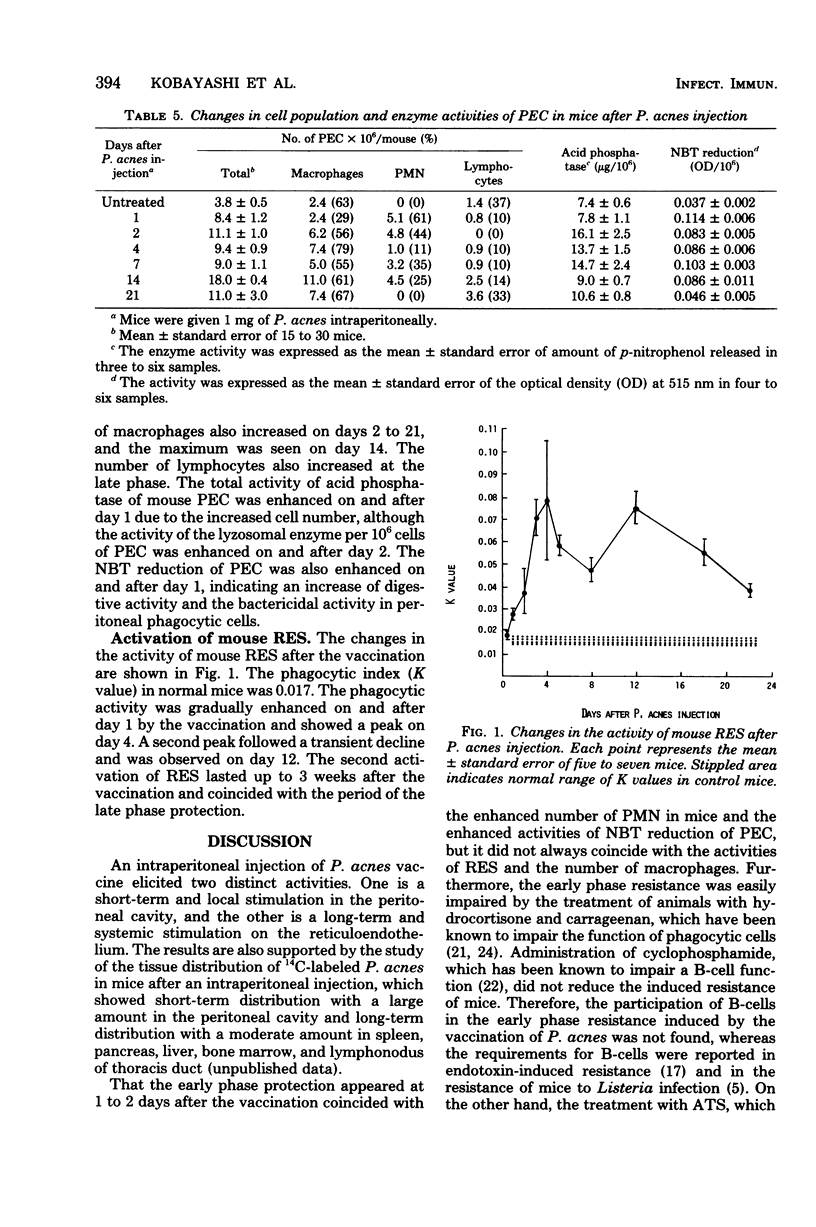

A single intraperitoneal injection of the phenol-treated cells of Propionibacterium acnes into mice showed nonspecific resistance against subsequent lethal doses of an intraperitoneal challenge of Klebsiella pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, and Streptococcus pyogenes. The protection showed a biphasic pattern. The maximum protection, designated as the early phase protection, was seen in mice injected with P. acnes vaccine 1 to 2 days before the challenge, whereas the late phase protection was seen in mice vaccinated 16 to 22 days before the challenge. The activity of the reticuloendothelial system in mice after vaccination also showed a biphasic pattern with the peak on days 4 and 12. The delayed activation of the reticuloendothelial system lasted up to 3 weeks and coincided with the period of the late phase protection. The early phase resistance was markedly impaired by the treatment with hydrocortisone and carrageenan, but not by the treatment with anti-thymocyte serum, actinomycin D, or cyclophosphamide. The number of peritoneal polymorphonuclear leukocytes in vaccinated mice increased on days 1 to 2. The number of macrophages also increased at 2 to 21 days after vaccination and reached its maximum on day 14. Total activities of acid phosphatase, Nitro Blue Tetrazolium reduction, and the phagocytic activities of peritoneal exudate cells were also enhanced on and after day 1 after the injection of P. acnes vaccine.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Adlam C., Broughton E. S., Scott M. T. Enhanced resistance of mice to infection with bacteria following pre-treatment with Corynebacterium parvum. Nat New Biol. 1972 Feb 16;235(59):219–220. doi: 10.1038/newbio235219a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BIOZZI G., BENACERRAF B., HALPERN B. N. Quantitative study of the granulopectic activity of the reticulo-endothelial system. II. A study of the kinetics of the R. E. S. in relation to the dose of carbon injected; relationship between the weight of the organs and their activity. Br J Exp Pathol. 1953 Aug;34(4):441–457. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baehner R. L., Nathan D. G. Quantitative nitroblue tetrazolium test in chronic granulomatous disease. N Engl J Med. 1968 May 2;278(18):971–976. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196805022781801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bomford R., Christie G. H. Mechanisms of macrophage activation by corynebacterium parvum. II. In vivo experiments. Cell Immunol. 1975 May;17(1):150–155. doi: 10.1016/s0008-8749(75)80015-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell P. A., Martens B. L., Cooper H. R., McClatchy J. K. Requirement for bone marrow-derived cells in resistance to Listeria. J Immunol. 1974 Apr;112(4):1407–1414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow L. A., Fischbach J., Bryant S. M., Kern E. R. Immunomodulation of host resistance to experimental viral infections in mice: effects of Corynebacterium acnes, Corynebacterium parvum, and Bacille calmette-guérin. J Infect Dis. 1977 May;135(5):763–770. doi: 10.1093/infdis/135.5.763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HALPERN B. N., PREVOT A. R., BIOZZI G., STIFFEL C., MOUTON D., MORARD J. C., BOUTHILLIER Y., DECREUSEFOND C. STIMULATION DE L'ACTIVIT'E PHAGOCYTAIRE DU SYST'EME R'ETICULOENDOTH'ELIAL PROVOQU'EE PAR CORYNEBACTERIUM PARVUM. J Reticuloendothel Soc. 1964 Jan;1:77–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride W. H., Weir D. M., Kay A. B., Pearce D., Caldwell J. R. Activation of the classical and alternate pathways of complement by Corynebacterium parvum. Clin Exp Immunol. 1975 Jan;19(1):143–147. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milas L., Scott M. T. Antitumor activity of Corynebacterium parvum. Adv Cancer Res. 1978;26:257–306. doi: 10.1016/s0065-230x(08)60090-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Möller G., Zukoski C. Differential effect of heterologous anti-lymphocyte serum on antibody-producing cells and antigen-sensitive cells. J Immunol. 1968 Aug;101(2):325–332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagoya T., Kobayashi F., Nomoto K. Immunological properties of Propionibacterium acnes. I. Potentiation and Suppression on antibody response to sheep and hamster erythrocytes in mice. Microbiol Immunol. 1977;21(1):33–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1977.tb02805.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nussenzweig R. S. Increased nonspecific resstance to malaria produced by administration of killed Corynebacterium parvum. Exp Parasitol. 1967 Oct;21(2):224–231. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(67)90084-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Neill G. J., Henderson D. C., White R. G. The role of anaerobic coryneforms on specific and non-specific immunological reactions. I. Effect on particle clearance and humoral and cell-mediated immunological responses. Immunology. 1973 Jun;24(6):977–995. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otu A. A., Russell R. J., White R. G. Biphasic pattern of activation of the reticuloendothelial system by anaerobic coryneforms in mice. Immunology. 1977 Mar;32(3):255–264. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parant M., Galelli A., Parant F., Chedid L. Role of B-lymphocytes in nonspecific resistance to Klebsiella pneumoniae infection of endotoxin-treated mice. J Infect Dis. 1976 Dec;134(6):531–539. doi: 10.1093/infdis/134.6.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruittenberg E. J., van Noorle Jansen L. M. Effect of Corynebacterium parvum on the course of a Listeria monocytogenes infection in normal and congenitally athymic (nude) mice. Zentralbl Bakteriol Orig A. 1975;231(1-3):197–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell R. J., McInroy R. J., Wilkinson P. C., White R. G. A lipid chemotactic factor from anaerobic coryneform bacteria including Corynebacterium parvum with activity for macrophages and monocytes. Immunology. 1976 Jun;30(6):935–949. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saino Y., Eda J., Nagoya T., Yoshimura Y., Yamaguchi M. Anaerobic coryneforms isolated from human bone marrow and skin. Chemical, biochemical and serological studies and some of their biological activities. Jpn J Microbiol. 1976 Feb;20(1):17–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1976.tb00903.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz H. J., Leskowitz S. The effect of carrageenan on delayed hypersensitivity reactions. J Immunol. 1969 Jul;103(1):87–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockman G. D., Heim L. R., South M. A., Trentin J. J. Differential effects of cyclophosphamide on the B and T cell compartments of adult mice. J Immunol. 1973 Jan;110(1):277–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodruff M. F., McBride W. H., Dunbar N. Tumour growth, phagocytic activity and antibody response in Corynebacterium parvum-treated mice. Clin Exp Immunol. 1974 Jul;17(3):509–518. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]