Widespread access to and use of identifiable health information (IHI) are essential to public health practice, especially for interventions designed to control communicable conditions like HIV, other sexually transmitted infections, and tuberculosis. Yet, these data represent some of the most sensitive patient health information for which misuses or wrongful disclosures raise serious privacy concerns. As a result, patients, health care providers, and policymakers have routinely sought strong privacy protections through law for these (and other) types of data. One of the major foci of health information privacy laws is the prohibition of disclosures of IHI without patient authorization, subject to limited exceptions. Notable among these exceptions are exchanges to federal, tribal, state, or local public health authorities (PHAs).1 To assure ready access to communicable disease data, the Health Insurance Privacy and Portability Act (HIPAA) Privacy Rule2 and virtually all patient-centered privacy laws allow sharing of IHI from health care providers to PHAs (and their partners) without patient authorization. This exception makes possible the free flow of health data that are the lifeblood of public health prevention and control measures.3

What about privacy protections related to the use and disclosure of IHI within and between PHAs? Although these agencies have an outstanding track record of maintaining confidentiality, do privacy laws authorize or restrict their further uses or releases of IHI to fulfill public health missions and objectives? In this issue of AJPH, Begley et al., from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention, and the National Nurse-led Consortium, present their findings on legal opportunities and obstacles to enhanced data sharing within and among state and local PHAs.

The primary dilemma they address is both perceived and real. PHAs across the country regularly face contrived or actual legal objections to cross-use or sharing of IHI for laudable public health purposes on grounds that individual privacy may be infringed. These objections seem to make little sense. In most cases, existing privacy laws and policies already allow the unauthorized disclosure of IHI from health care providers to PHAs. Why should PHAs who lawfully possess the data not be able to use them for any public health purposes they see fit? The problem extends from a lack of uniformity among an array of state statutory and regulatory laws that (1) feature poorly worded or limiting provisions, (2) apply restrictive measures to certain types of IHI, (3) fail to explicitly address potential data uses or sharing, or (4) are simply misinterpreted by legal counsel or others perhaps concerned more about protecting privacy than the public’s health. Collectively, these issues can stymie public health data exchanges.

Despite acknowledged limitations in the scope of their assessment, the authors’ extensive research and tables go a long way toward providing a clearer path to enhanced data practices within and between health departments. For example, they illustrate how current state-based general legal allowances for “uses” and “releases” of IHI within and between PHAs facilitate cross-jurisdictional communicable disease control interventions. Still, some attorneys may opine that nonconsensual exchanges between departments are unlawful in states where disease-specific laws are silent on their permissibility despite general legal allowances. This type of ill-fated guidance displaces long-standing public health data norms in favor of patient privacy to the detriment of communal health and with no appreciable privacy benefit.

SEEKING SOLUTIONS TO IDENTIFIED IMPEDIMENTS

Still, there are lawful ways around existing legal impediments. To avoid all privacy laws in any form, PHAs can attempt to de-identify the data so individual patients are unknown. Working with limited data sets may also meet privacy norms in many cases. Alternatively, PHAs can garner advanced individual authorization for multiple uses or releases of IHI, which may satisfy most privacy laws. This technique may be particularly useful when PHAs are engaged in covered functions as hybrid entities under the HIPAA Privacy Rule. These techniques may placate privacy concerns, but they can be onerous or expensive for departments and contrary to public health purposes if individuals whose data are sought do not consent.

SYNERGY BETWEEN DATA PRIVACY AND PUBLIC HEALTH

Among principle findings presented by Begley et al. is that free-flowing public health data uses and releases are legally supported in most cases, provided that PHAs retain the confidentiality of IHI within the broader public health system. These takeaways are highly interconnected. Protecting the public’s health is synergistic with assuring adequate privacy protections. Individuals alone cannot assure the public’s health.4 Conversely, PHAs cannot sufficiently advance communal health if individuals fearful of privacy infringements reject public health programs (e.g., screening and testing, partner notification) or decline medical services (e.g., HIV or other tests). Before the use of anonymous testing for HIV in the 1980s, many at-risk adults would not be tested for fear of privacy invasions.5 The interrelatedness of privacy and public health is time-tested, empirically proven, and a primary driver of public health laws and policies nationally. It is an architectural lynchpin of the HIPAA Privacy Rule and multiple other privacy laws, including the Model State Public Health Privacy Act (MSPHPA).6

MODEL STATE PUBLIC HEALTH PRIVACY ACT

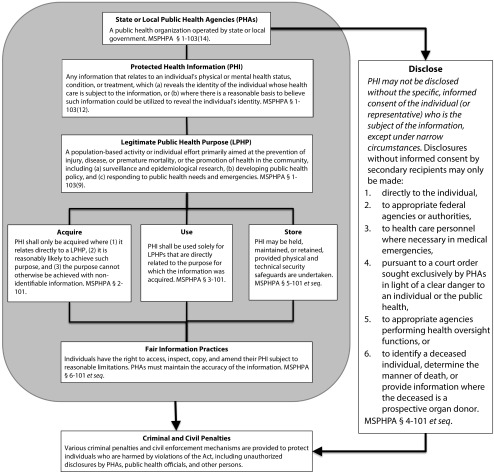

Developed initially in 1999 under the auspices of CDC and other partners, and later folded into the comprehensive Turning Point Model State Public Health Act of 2003,7 MSPHPA provisions reflect the findings by Begley et al. (and in some instances are incorporated into the state laws they studied). As outlined in Figure 1 (published originally in a modified format in the Journal in 20016), PHAs need extensive access to IHI and broad authority to use or release such data for cross purposes within and between like agencies. However, disclosures of such data outside PHAs are tightly controlled, similar to many states’ laws governing these data exchanges.

FIGURE 1—

The Model State Public Health Privacy Act (MSPHPA)

Source. Adapted from Gostin et al.6

Drafters of the MSPHPA rejected disease-specific laws proliferating across states (at the center of the study by Begley et al. in place of uniform privacy safeguards for IHI that preserve the ability of PHAs to act for the common good.

Although the legal assessment by Begley et al. was purposefully limited to reviewing use and release provisions governing data held by PHAs, provisions of the MSPHPA go further to assure adequate privacy safeguards through a series of fair information practices. Designed to help maintain the privacy of public health information without unreasonably burdening PHAs, these practices

require justification for IHI acquisitions and uses tied to accomplishing legitimate public health purposes;

publicize the types of information acquisitions sought by PHAs;

allow individual inquiries about nonpublic health disclosures of their IHI;

give persons rights to access, inspect, and copy their IHI; and

mandate that PHAs adhere to privacy and security safeguards.

States seeking to remedy privacy impediments while assuring adequate protections may seek reforms based on the provisions of the Model Act. As touted by Begley et al., lessening the array of disease-specific laws in any jurisdiction may facilitate greater data sharing within and between PHAs. Incorporation of the MSPHPA could essentially replace myriad condition-specific public health data laws with a consistent privacy framework. The net outcome is the enhanced promotion of public health coupled with respect for individual privacy in an increasingly national electronic public health data infrastructure.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I thank Sarah Noe at the Center for Public Health Law and Policy, Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law, Arizona State University, for reviewing the article.

Footnotes

See also Begley et al., p. 1272.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIPAA privacy rule and public health: guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and the Department of Health and Human Services. MMWR Suppl. 2003;52(suppl 1):1–17. 19–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Department of Health and Human Services. Standards for privacy of individually identifiable health information: final rule. 45 CFR parts 160 and 164. Fed Regist. 2002;67(157):53181–53273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gostin LO, Hodge JG. Personal privacy and common goods: a framework for balancing under the National Health Information Privacy Rule. Minn Law Rev. 2002;86(6):1439–1479. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hodge JG. Public Health Law in a Nutshell. 2nd ed. Eagan, MN: West Academic Publishing; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Obermeyer CM, Osborn M. The utilization of testing and counseling for HIV: a review of the social and behavioral evidence. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(10):1762–1774. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.096263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gostin LO, Hodge JG, Valdiserri RO. Informational privacy and the public’s health: the Model State Public Health Privacy Act. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(9):1388–1392. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.9.1388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hodge JG, Gostin LO, Gebbie K, Erickson DL. Transforming public health law: the Turning Point Model State Public Health Act. J Law Med Ethics. 2006;34(1):77–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2006.00010.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]