Abstract

Eukaryotic gene expression is tightly regulated transcriptionally and post-transcriptionally by a host of noncoding (nc)RNAs. The best-studied class of short ncRNAs, microRNAs, mainly repress gene expression post-transcriptionally. Long noncoding (lnc)RNAs, which comprise RNAs differing widely in length and function, can regulate gene transcription as well as post-transcriptional mRNA fate. Collectively, ncRNAs affect a broad range of age-related physiologic deteriorations and pathologies, including reduced cardiovascular vigor and age-associated cardiovascular disease. This review presents an update of our understanding of regulatory ncRNAs contributing to cardiovascular health and disease as a function of advancing age. We will discuss (1) regulatory ncRNAs that control aging-associated cardiovascular homeostasis and disease, (2) the concepts, approaches, and methodologies needed to study regulatory ncRNAs in cardiovascular aging and (3) the challenges and opportunities that age-associated regulatory ncRNAs present in cardiovascular physiology and pathology. This article is part of a Special Issue entitled “CV Aging”.

Keywords: MicroRNA, Long noncoding RNA, Aging, Cardiovascular disease

1. Introduction

1.1. Gene regulation by ncRNAs

The adaptation of mammalian cells to external and internal signals requires precise transcriptional and post-transcriptional modulation of gene expression patterns. Transcription is controlled mainly through changes in chromatin composition and the recruitment of transcription factors, while post-transcriptional control is elicited through pre-mRNA splicing as well as mRNA transport, stability, storage, and translation. Noncoding (nc)RNAs, the main focus of this review, influence all of these gene regulatory levels [1]. Nuclear ncRNAs control transcription by associating with chromatin and transcriptional activators and repressors, and they control early post-transcriptional steps in gene regulation, such as pre-mRNA splicing [2]. Cytoplasmic ncRNAs regulate mRNA turnover rate, mRNA storage and localization, and mRNA recruitment to ribosomes [3,4]. Since aberrant gene control underlies the age-related decline in physiologic function and age-associated diseases, it is critically important to understand how gene expression is altered in aging. Gene regulation by DNA- and RNA-binding proteins affecting aging pathology and physiology has been studied for decades. However, the deep and broad impact of regulatory ncRNAs in aging is only now coming into view.

ncRNAs comprise a large and heterogeneous family. It includes many RNAs that have been known for decades and mainly have housekeeping functions, such as ribosomal RNAs (rRNAs), small nuclear RNAs (snRNAs), small nucleolar RNAs (snoRNAs), and transfer RNAs (tRNAs). However, the advent of tiling arrays and RNA-sequencing over the past ~15 years has revealed that large stretches of chromosomes previously believed not to be transcribed, are actually transcribed and encode vast numbers of ncRNAs [5]. Arbitrarily divided into long (lncRNAs, >200 nt), and short (<200 nt) ncRNAs, these regulatory transcripts display distinct temporal and spatial expression patterns. As details of the impact of ncRNAs on molecular and cellular processes are becoming better understood, their roles in aging-associated physiologic processes and disease conditions are also starting to emerge [6].

1.1.1. microRNAs

Although short RNAs also include piwi-interacting and small interfering RNAs (piRNAs, siRNAs), microRNAs (miRNAs) have been most actively studied in different contexts, including aging [7,8]. MicroRNAs are single-stranded, ~22 nt-long ncRNAs that regulate gene expression mainly by forming partial hybrids with target mRNAs and thereby lowering their translation and/or stability [9]. A microRNA is transcribed as a long, primary miRNA (pri-miRNA) which is cleaved by the microprocessor complex (containing the ribonuclease Drosha) to generate a miRNA precursor (pre-miRNA) that is exported to the cytoplasm [4]. In the cytoplasm, the ribonuclease Dicer cleaves the pre-miRNA to yield a ~22-bp-long duplex RNA; one strand of the duplex, the mature miRNA, is loaded onto the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), which contains Argonaute (Ago) proteins [10,11]. Each Ago-microRNA complex targets a subset of mRNAs forming partial hybrids, often at the 3′-untranslated region (UTR) of the mRNAs and frequently relying on the miRNA ‘seed’ region (nucleotides 2–7). Several microRNAs often work in concert to lower the expression of a shared target mRNA. MicroRNAs have been implicated in virtually all areas of mammalian homeostatic gene regulation, and disruption of miRNA function has been causally linked to a variety of cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) that rise with advancing age [7,8,12,13].

1.1.2. LncRNAs

LncRNAs can be classified according to their genomic localization and biogenesis: lincRNAs are expressed from intergenic regions, antisense lncRNAs are expressed from the opposite strand of mRNAs and lncRNAs, pseudogene-encoded lncRNAs are transcribed from vestigial genes that lost their coding potential, long intronic ncRNAs are present in introns of annotated genes, promoter-associated lncRNAs are transcribed from the promoter regions of coding mRNAs, and circular RNAs are often generated by the splicing machinery [14].

This large class of ncRNAs can also be classified according to their molecular mechanism of action. (1) Epigenetic regulation: some nuclear lncRNAs regulate gene expression by serving as scaffolds, bridges, and tethers of factors that regulate the state of the chromatin. By recruiting chromatin-modification enzymes, lncRNAs can transiently or permanently activate/inactivate genes and chromosomal regions. The ability to recognize DNA sequences uniquely enables lncRNAs to elicit highly precise, sequence-specific actions on transcription. Examples of chromatin-remodeling lncRNAs are XIST and HOTAIR [15,16]. (2) Transcriptional regulation: lncRNAs can also assemble transcriptional activators and repressors to modulate the rates of RNA polymerase II initiation and elongation. Examples of transcription-modulatory lncRNAs include NEAT1, ANRIL (CDKN2B-AS), GAS5, and MALAT1 [16,17]. (3) Nuclear compartmentalization: some nuclear lncRNAs have been implicated in maintaining nuclear structures, including nuclear speckles, paraspeckles, and interchromatin granules; examples include TUG1, MALAT1, NEAT1, and FIRRE [17]. (4) Post-transcriptional gene regulation: lncRNAs that basepair with mRNAs can modulate the translation and/or the stability of target mRNAs (e.g., 1/2-sbsRNAs, LINCRNAP21 [18,19]) while lncRNAs that do not basepair can affect precursor mRNA splicing and translation by acting as cofactors or competitors of RNA-binding proteins [20,21]. (5) Competing endogenous RNAs (ceRNAs): although lncRNAs are generally low-abundance transcripts, some lncRNAs accumulate because they are highly stable (e.g., circular RNAs) and can function as decoys or sponges for microRNAs (e.g., LINCMD1 [22]) and possibly other regulatory factors [23]. (6) Post-translational gene regulation on protein turnover has also been reported for the lncRNA HOTAIR, which scaffolds pairs of E3 ubiquitin ligases and their substrates [24]. As reviewed comprehensively elsewhere [25,26], lncRNA-modulated gene expression patterns are relevant to a variety of cell functions with impact upon many age-associated conditions.

1.2. Aging and CVDs

Age is the most important risk factor for CVDs, the most prominent cause of death worldwide [http://www.who.int/cardiovascular_diseases/resources/atlas/en/.]. Advancing age increases exposure to cardiovascular risk factors, and elicits intrinsic cardiovascular changes that compromise both the cardiovascular reserve capacity and the threshold for primary diseases to manifest [27,28].

The aging heart is characterized by several detrimental changes such as left ventricular hypertrophy, diastolic dysfunction, valve degeneration, increased cardiac fibrosis, increased prevalence of atrial fibrillation, and decreased maximal exercise capacity [29,30]. Endothelial function, particularly endothelium-dependent dilation [31,32], also decreases with aging; this decline is due, at least in part, to the reduced bioavailability of nitric oxide (NO) following inflammation and oxidative stress in the elderly [33,34]. Dysfunctional endothelium correlates with higher systolic and pulse pressure, and, consequently, with increased risk of age-associated conditions such as atherosclerosis, hypertension, acute myocardial infarction (AMI), and stroke [35]. Additionally, the walls of the arteries and arterioles become thicker and less elastic, making the vessels stiffer and less resilient [35,36].

2. Noncoding RNA in cardiovascular aging and age-associated CVDs

Our understanding of ncRNA function in the molecular mechanisms underpinning the age-associated changes in the cardiovascular systems is much more advanced for miRNAs than for lncRNAs. Thus, a provisional but already delineated scenario is emerging, with specific miRNAs regulating a variety of cardiovascular functions in both homeostasis and disease. By contrast, for lncRNAs, in most circumstances, we have just started scratching the surface, and, at the moment, the existing data linking individual lncRNAs and age-associated CVDs are mainly correlative. While many more studies specifically aimed at dissecting ncRNA functions in cardiovascular system aging are needed, the ncRNAs already identified in age-related CVDs are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

ncRNAs and age-related cardiovascular diseases.

| ncRNA | Disease/condition | Modulation | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|

| miR-146 | Heart failure | Up | [54] |

| miR-17-92 cluster | Heart failure (mouse) | Down | [69] |

| miR-1 | Heart failure, hypertrophy (mouse) | Up | [79] |

| miR-216a | Heart failure | Up | [188] |

| miR-29 family | Aorta aneurysm | Up | [53] |

| miR-155 | Atherosclerotic lesions | Up | [59] |

| miR-21 | Atherosclerotic plaques | Up | [96] |

| miR-216a | Atherosclerotic plaques | Up | [103] |

| miR-217 | Atherosclerotic plaques | Up | [109] |

| miR-1 | Myocardial infarction (mouse) | Up | [132] |

| miR-34a | Myocardial infarction (mouse) | Up | [61] |

| miR-200c | Peripheral ischemia | Up | [90] |

| miR-210 | Peripheral ischemia | Up | [99] |

| miR-145 | Ischemia/reperfusion | Down | [97] |

| Mkk7 | Heart failure (mouse) | Down | [126] |

| Mhrt | Heart failure (mouse) | Down | [132] |

| H19 | Heart failure | Up | [189] |

| Alc1-AS | Hypertrophy (mouse) | Up | [190] |

| Chrf | Hypertrophy (mouse) | Down | [125] |

| Mirt1/Mirt2 | Myocardial infarction (mouse) | Up | [137] |

2.1. miRNAs

MiRNAs are involved in virtually all processes of physiology and disease, including aging [11,37,38]. Some 65 miRNAs have been identified that display significantly different expression levels between young adult heart and older adult heart [39]. Here, we will review the miRNAs related to the dysfunction of several well-recognized age-associated processes affecting the cardiovascular system, including senescence, nutrient sensing, oxidative stress response, inflammation, and silent mating type information regulation 2 homolog (SIRT1)-regulated events.

2.1.1. Senescence

Cells from normal animal tissue placed in culture divide for a finite number of times but eventually stop proliferating and enter a state of terminal growth arrest named senescence [40]. Replicative senescence is triggered by the progressive shortening of the telomeres that results from cell division and by exposure to a range of damaging conditions [41]. Senescent cells do not divide, but they can remain viable and metabolically active for a long time, displaying a large and flat morphology, cytoplasmic vacuoles, enhanced autophagy, and elevated activity of lysosomal β-galactosidase [11,42]. Many senescent cells also display a characteristic senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) [43], whereby they secrete many cytokines and chemokines (e.g., GM-CSF, IL-6, IL-8, IL-1α), and matrix metalloproteases (e.g., MMP-1, MMP-3). Another hallmark of senescence is the activation of tumor suppression pathways, mainly those controlled by p53/p21 and pRB/p16 [41]. Finally, since senescent cells frequently experience oxidative and genotoxic damage, they generally express DNA-damage response proteins, such as γ-H2AX, NIBRIN (NBS), MDC1, and 53BP1 [41].

Cellular senescence has been studied most extensively in cultured cells, but there is broad recognition that senescence occurs in vivo and affects aging phenotypes profoundly [41]. Since senescent cells accumulate in tissues as the organism ages, their metabolic behavior and their signature gene expression profile have been linked to a number of age-related physiologic and pathologic changes including CVDs [44, 45]. For instance, accumulation of senescent endothelial cells (ECs) in atherosclerotic lesions is an important factor contributing to age-associated arterial dysfunction [46,47].

Several transcription factors, such as p53 and proteins in the AP-1, E2F, Id and Ets families, have been implicated in driving senescence. In addition, several RNA-binding proteins can regulate senescence via post-transcriptional gene regulation, including human antigen R (HuR), AU-binding factor 1 (AUF1), and tristetraprolin (TTP), through their association with target mRNAs that encode senescence factors [48,49]. However, a growing number of regulatory miRNAs also influence senescence-associated gene expression patterns by regulating key molecular pathways (Fig. 1):

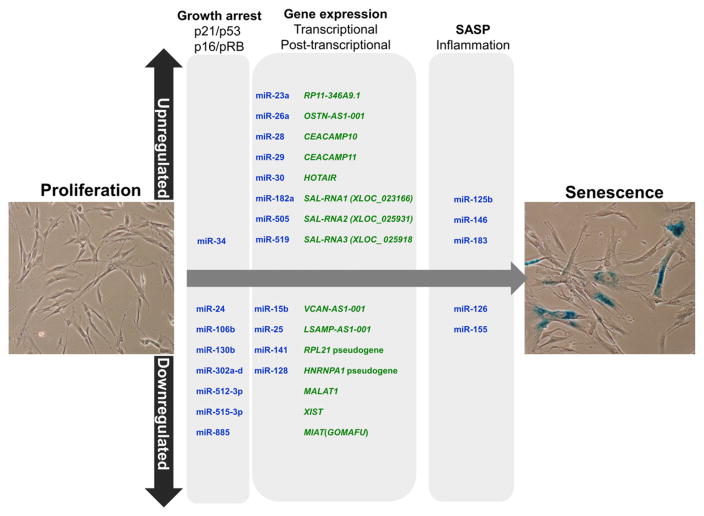

Fig. 1.

Senescence-associated ncRNAs. Several studies have identified ncRNAs upregulated and downregulated in senescence, but only few have been shown to modulate senescence experimentally. The figure shows microRNAs (blue) and lncRNAs (green) directly implicated in molecular pathways that govern cell senescence.

pRB/p16 pathway. Senescent cells have active (hypophosphorylated) pRB, resulting from risen levels of two potent inhibitors of cyclin-dependent kinases (cdks, which are pRB kinases): p21 (in part upregulated via p53) and p16. Some miRNAs that reduce p21 abundance (e.g., miR-106b, miR-130b) decline during senescence [50,51].

p53/p21 pathway. Senescent cells have elevated levels of p53, a protein subject to negative regulation by MCM5 (which is repressed by miR-885-5p) [52]. Elevated p53 transcriptionally upregulates miR-34a, which in turn reduces the levels of several proliferative proteins (E2F, c-Myc, cyclins and cdks) and anti-apoptotic proteins (Bcl-2 and SIRT1).

Senescent cell-specific gene expression programs. Numerous proteins modulate senescence-associated gene transcription, such as PCGF4, HMGA2, RARγ and B-Myb (MYBL2), while other proteins affect senescence-associated gene expression post-transcriptionally, including the splicing factor ASF/SF2 and the mRNA stability and translation regulator HuR. Each of these proteins is also subject to control by senescence-associated miRNAs [11], and some of these miRNAs cross-talk with the p53/p21 and the p16/RB pathways (e.g., HMGA2 represses p21 transcription and Bmi-1 represses p16 transcription). Importantly, senescence factors can also directly modulate the expression of senescence-regulatory miRNAs; for example, pRB transcriptionally increases miR-29/miR-30 levels and this regulation can impact upon the deposition of extracellular matrix (ECM). In aged aortas, increased levels of miR-29 family members were causally associated to the downregulation of ECM components, linking miR-29 to a decrease in ECM proteins and the age-associated formation of aorta aneurysms [53].

SASP. Secretion of some SASP factors (e.g., IL-6, IL-8) is under control of IRAK1, a protein whose levels are reduced by the senescence-associated miR-146. Factors secreted through the SASP cause inflammation, contributing to a general increase of inflammation also termed “inflammageing”. Accordingly, miR-146 has been shown to be increased in senescent ECs [54] as well as in endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) from heart failure (HF) patients [55].

The fact that miR-126 controls endothelial inflammation, at least in part by modulating the expression of VCAM-1 cell adhesion proteins [56], helps to explain why low levels of circulating miR-126 were found associated with in CVDs and diabetes [57], two conditions characterized by EC activation. These proinflammatory effects may also be linked to miR-126-mediated downregulation of NF-κBIB (IκBβ), a potent inhibitor of NF-κB signaling [58]. High levels of miR-155 were found in proinflammatory macrophages and atherosclerotic lesions, although the effects of miR-155 appear to differ between early and advanced atherosclerosis [59]. Interestingly, miR-155 lowers angiotensin II type 1 receptor (AT1R) activity leading to endothelial dysfunction, structural remodeling, and vascular inflammation [60].

Certain senescence-associated miRNAs function at the convergence of different pathways. For instance, miR-34a levels are increased in aged hearts, but since cardiomyocytes are mostly post-mitotic, miR-34a likely does not influence proliferation in these cells. Instead, cardiomyocyte miR-34a lowers Ppp1r10 (PNUTS) [61], a protein that interacts with the telomere regulator TRF2 to control DNA repair and reduce telomere attrition. PNUTS protects cardiomyocytes from oxidative damage and death and both increased PNUTS and reduced miR-34a prevent the deterioration of cardiac contractile function after AMI [61].

2.1.2. Fibrosis

Aging hearts are characterized by increased expression of ECM proteins [62], fibronectin [63], thrombospondin-2 (TSP-2) [64] and connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) [65]. These elevated levels are due, at least in part, to the age-dependent accumulation of senescent cells in these tissues, which promote inflammation and cardiac fibrosis [66–68]. Notably, miR-18a and miR-19a/b, from the miR-17–92 cluster, are causally linked to age-related fibrotic remodeling of the heart upon HF [69]. TSP-1 and CTGF, which contribute to the fibrotic process, are targets of miR-18a and miR-19a and their levels are inversely correlated.

Increased levels of miR-29 family members were causally associated to the downregulation of ECM components in aged aortas, linking miR-29 to the decrease in ECM proteins and the age-associated formation of aorta aneurysms [53]. Fibrotic myocardium also shows high levels of miR-21; by lowering the abundance of target protein SPRY2, miR-21 activates signaling through ERK/MAPK, leading to increased fibrosis and decreased apoptosis [70]. The role of miR-21 in age-associated fibrosis has not been elucidated, but it is worth noting that miR-21 levels increase in aged hearts [39]. Another microRNA linked to fibrosis, miR-30, targets the profibrotic growth factor CTGF. The downregulation of miR-30 in left ventricle hypertrophy is associated to increased production of ECM components [71].

2.1.3. Nutrient sensing pathways

Major metabolic pathways include those governed by insulin, insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1), and target of rapamycin (TOR). Excessive food intake leading to secretion of insulin, which facilitates the uptake of glucose to be stored as fat, the accumulation of visceral fat, and insulin resistance, are major risk factors for CVDs [72,73], including atherosclerosis [74–76]. The tendency of centenarians to maintain high insulin sensitivity [77] suggests that systemic insulin/IGF1 pathway activation itself confers protection from CVD in the absence of obesity.

The influence of miR-1 in IGF1 signaling in cardiomyocytes is well documented. miR-1 directly represses IGF1 mRNA in cardiac and skeletal muscle [78], and miR-1 levels are inversely correlated with IGF1 protein levels in models of cardiac hypertrophy and failure [79]. In this regard, Shan et al. [80] reported that the levels of IGF1 repressors miR-1 and miR-206 increased in the ischemic zone in rat AMI. Overexpression of miR-1 or silencing of IGF1 in H9C2 rat cardiomyoblasts upon serum withdrawal or hypoxia elevated caspase-3 activity and mitochondrial potential, in agreement with the anti-apoptotic function of IGF1 [81,82].

Moderate caloric restriction (CR) without malnutrition is a dietary regimen recognized to delay aging and extend lifespan [83]. In aged ECs, miR-144 abundance increases while that of its predicted target NF-E2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) decreases. This influence is potentially important, since activation of Nrf2 upon CR has potent anti-oxidative, pro-angiogenic, and anti-inflammatory effects in mouse ECs [84].

2.1.4. Oxidative stress

Mitochondrial dysfunction is another hallmark of aging-associated diseases. As cells and organisms age, the efficacy of the respiratory chain declines, causing increased electron leakage and reduced ATP generation [85]. Additionally, the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) by dysfunctional mitochondria can trigger cellular events culminating in a wide range of CVDs [86,87]. Different miRNAs modulated by oxidative stress are involved in endothelial and vascular dysfunction and are associated to CVDs caused by excessive ROS production [88].

miR-200, miR-141

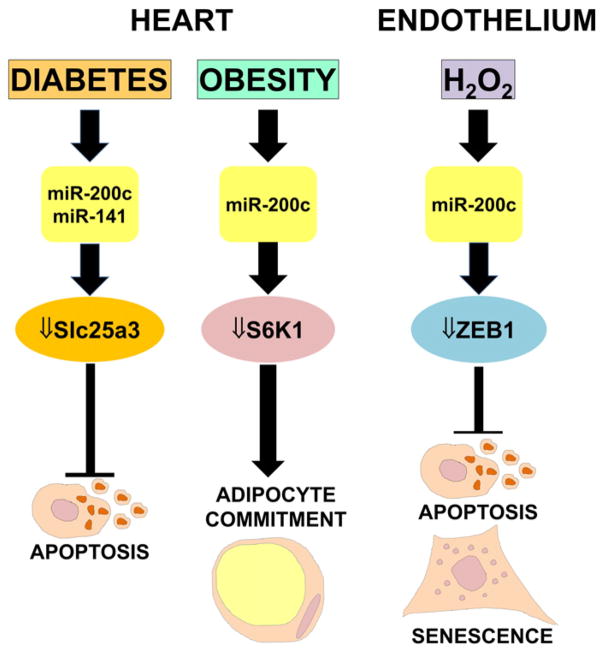

miRNA profiling experiments have revealed that the miR-200 family members miR-200c and miR-141 are upregulated in hydrogen peroxide (H2O2)-treated ECs [89] (Fig. 2). Moreover, the miR-200 family is also induced following acute ischemia, which generates oxidative stress [90]. Accordingly, in p66ShcA −/− mice, which display lower levels of oxidative stress upon ischemia, miR-200c and miR-200b are less upregulated [89]. The pro-survival protein ZEB1 was identified as a direct target of miR-200c, leading to the discovery that ZEB1 knockdown recapitulated miR-200c-triggered responses and that miR-200-mediated inhibition of ZEB1 was a key effector of ROS-induced apoptosis and senescence. In keeping with the increased oxidative stress levels observed in diabetes mellitus, miR-200c and miR-141 are among the most upregulated miRNAs in diabetic mouse heart [91]. The levels of miR-141-target SLC25A3 (solute carrier family 25 member 3), which provides inorganic phosphate to the mitochondrial matrix and is essential for ATP production, declines in type 1 diabetes, affecting adversely ATP production and cell viability. Finally, miR-200c, which is not normally expressed in heart, is readily detectable in the heart of Zucker obese rats, where it participates in adaptive mechanisms compensating excessive activation of the nutrient sensor kinase S6K1 [92].

Fig. 2.

miR-200 regulates endothelial dysfunction and cardiovascular complications linked to diabetes and obesity. ROS production or pathologies associated to elevated ROS production play a causal role in endothelial and cardiovascular diseases. (Left) MiR-200c and miR-141 are among the most highly upregulated miRNAs in diabetic mouse heart; accordingly, the target of miR-200 SLC25A3, a protein essential for ATP production, declines in type 1 diabetes, reducing ATP production and cell viability. (Center) In Zucker obese rats, a genetic model for obesity, hypertension and cardiac dysfunction, elevated miR-200c activates a compensatory mechanism to down-regulate excessive activation of the nutrient sensor kinase S6K1, involved in adipocyte lineage commitment. (Right) MiR-200c levels rise following oxidative stress; the ensuing inhibition of its target ZEB1 induces cell growth arrest, apoptosis and cellular senescence.

miR-21

Treatment of rat vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) with H2O2 elevated miR-21, which in turn protected VSMCs from H2O2-dependent apoptosis and death. A major target of miR-21-mediated repression is PDCD4 (Programmed cell death 4), a pro-apoptotic protein that inhibits the activity of the transcription factor AP-1 [93], providing a plausible mechanism whereby elevated miR-21 protects ECs from oxidative injury. Among the factors triggering the development of atherosclerotic lesions are disturbances in flow dynamics [94]. Shear stress increases miR-21 levels, which contributes to protecting ECs by increasing endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) and nitric oxide (NO) production [95]. However, miR-21 function is complex and context-dependent; in this regard, miR-21 has detrimental effects in atherosclerotic plaques, where high levels of miR-21 decreases the functions of the mitochondrial defense proteins SPRY2 and superoxide dismutase-2 (SOD-2). These effects, in turn, lead to ERK/MAPK activation, resulting in increased ROS levels and EPC migratory defects [96].

miR-145

After AMI, during ischemia–reperfusion injury, ROS typically causes oxidative stress in cardiomyocytes. Recently, Li et al. found reduced miR-145 levels in both ischemia/reperfused heart and H2O2-treated cardiomyocytes [97]. Given that miR-145 protected against oxidative stress-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis by inhibiting expression of its target BNIP3 and by preventing ROS generation, miR-145 was proposed to function as a cardioprotective molecule capable of counteracting ROS toxicity.

miR-210

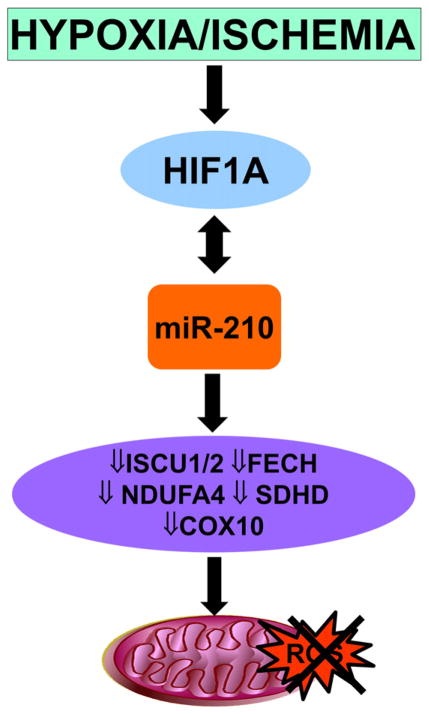

Another potent inducer of mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress is hypoxia [98]. miR-210 is robustly induced by hypoxia, contributing to the oxidative phosphorylation decline observed in low oxygen by repressing ISCU1, ISCU2, COX10 and FECH mRNAs. These transcripts, in turn, encode proteins which directly or indirectly affect the mitochondrial respiratory chain [98]. Accordingly, miR-210 inhibition triggered mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress and increased tissue damage upon ischemia [99] (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

miR-210 regulates mitochondrial activity. miR-210 represses target ISCU1, ISCU2, COX10 and FECH mRNAs, encoding proteins that directly or indirectly affect the mitochondrial respiratory chain and reduce ROS production.

2.1.5. Autophagy

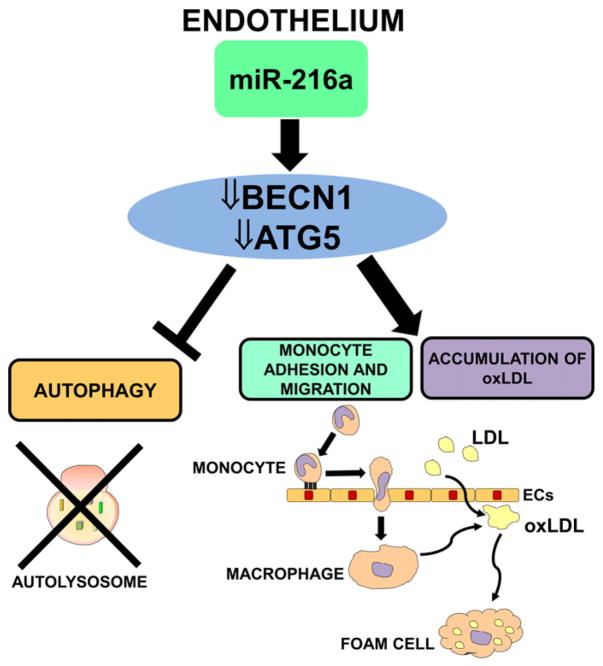

Autophagy is a recycling mechanism whereby cells degrade unnecessary cytoplasmic material and organelles in lysosomes [100]. A decline of the autophagy factors has been observed in aging tissues and in age-related disorders [101,102]. Autophagy seems to play a protective role during atherosclerosis, because it stabilizes plaques through the processing of oxidatively modified proteins, whereas acquired defects in plaques autophagy exacerbate atherosclerosis [100]. Menghini et al. [103] showed that expression of BECN1, ATG5 and LC3B-II/MAP1LC3B, key autophagy-related proteins, decreased during EC senescence, suggesting that the autophagic process is impaired with aging (Fig. 4). They also showed that miR-216a was induced during endothelial aging and that it was able to reduce the expression of BECN1 and ATG5. As a consequence, miR-216 also regulated autophagy induced by oxidized low-density lipoprotein (ox-LDL) treatment, stimulated ox-LDL accumulation, and promoted monocyte adhesion in ECs. The role of miR-216a seems to be particularly important not only in the development of atherosclerosis, but also in HF, since miR-216a expression in human failing hearts was inversely correlated with ejection fraction and with expression levels of BECN1 and ATG5 mRNAs [103].

Fig. 4.

miR-216a regulates autophagy. miR-216a activity on its targets BECN1 and ATG5 inhibits autophagy and stimulates ox-LDL accumulation in EC as well as monocyte adhesion and migration.

2.1.6. SIRT1 pathway

The “Silent mating type information regulation 2 homolog” (sirtuin 1 or SIRT1) is an NAD+-dependent class III histone deacetylase (HDAC) that can extend the lifespan of organisms and its levels are elevated with CR [104,105]. Via deacetylation, SIRT1 activates a myriad of stress-responsive transcription factors, co-regulators and enzymes, thus playing a direct role in metabolic control [106]. In ECs, SIRT1 upregulation and/or activation is associated with beneficial effects on ECs, while excessive ROS and aging decreases SIRT1 expression leading to endothelial dysfunction [107].

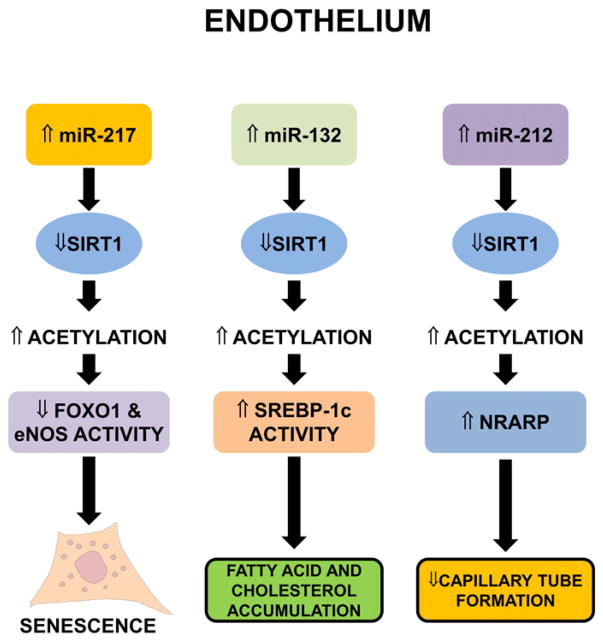

2.1.6.1. miR-217

This miRNA shows increased plasma levels with advancing age and decreased levels by CR in mouse [108]. Endothelial senescence is affected by this age-associated increase in miR-217, which lowers SIRT1 levels. In turn, decreasing SIRT1 levels promotes the acetylation state of Forkhead box protein O1 (FoxO1) and eNOS, reducing their activity [109] (Fig. 5). Accordingly, miR-217 correlates negatively with SIRT1 expression levels in human atherosclerotic plaques and with FOXO1 acetylation status [109].

Fig. 5.

SIRT1 regulation by miRNAs in ECs. miR-217 downregulates SIRT1 expression. This leads to lower deacetylation of its targets FOXO1 and eNOS, rendering them inactive and triggering senescence (left). By targeting SIRT1 expression, miR-132 decreases SREBP-1c acetylation and increases its activity, promoting the accumulation of fatty acids and cholesterol (center). In TGF-β-treated ECs, miR-212 reduces SIRT1 abundance, inhibits endothelial migration and capillary tube formation, and stimulates Notch signaling via NRARP (right).

2.1.6.2. miR-132

In ECs overexpressing miR-132, SIRT1 levels were reduced [110] (Fig. 5). By lowering SIRT1 abundance, miR-132 promotes the accumulation of fatty acids and cholesterol in HUVEC cells. In fact, SIRT1 was shown to deacetylate and hence inhibit the sterol regulatory element-binding protein (SREBP)-1c, decreasing its association with lipogenic target genes [111]. In view of these data, SIRT1 may be involved in the fine-tuning of vascular endothelial proinflammatory processes triggered by fatty acid accumulation in vessels.

MiR-132 belongs to the pro-hypertrophic miR-212/132 cluster. In TGF-β-treated ECs, miR-212 expression levels increase, while the expression of its target SIRT1 decreases [112]. Inhibiting miR-212, but not miR-132, restores endothelial migration and capillary tube formation upon TGF-β challenge, while overexpression of SIRT1 rescues.tube formation capacity inmiR-212 overexpressing ECs [112]. Morever, SIRT1 deacetylates Notch, thereby inhibiting signaling through Notch, which negatively regulates angiogenic functions [113]. The inhibition of miR-212 partly normalizes TGF-β-induced overexpression of NRARP (Notch-Regulated Ankyrin Repeat Protein), indicating that TGF-β suppresses SIRT1 and activates Notch signaling in ECs, at least in part, via miR-212 (Fig. 5).

2.1.6.3. miR-34a

This pleiotropic microRNA also regulates cellular senescence and angiogenesis by reducing SIRT1 levels. miR-34a levels increase and SIRT1 levels decrease in aging hearts and senescent ECs [114]. The repression of SIRT1 by miR-34a also decreases the resistance of Bone Marrow Cells (BMCs) to oxidative stress and lowers the ability of EPCs to rescue heart function after AMI [115]. In EPCs, decreased miR-34a due to statin treatment rescues SIRT1 levels, possibly contributing to the beneficial effects of statins on endothelial function in coronary artery disease (CAD) [116].

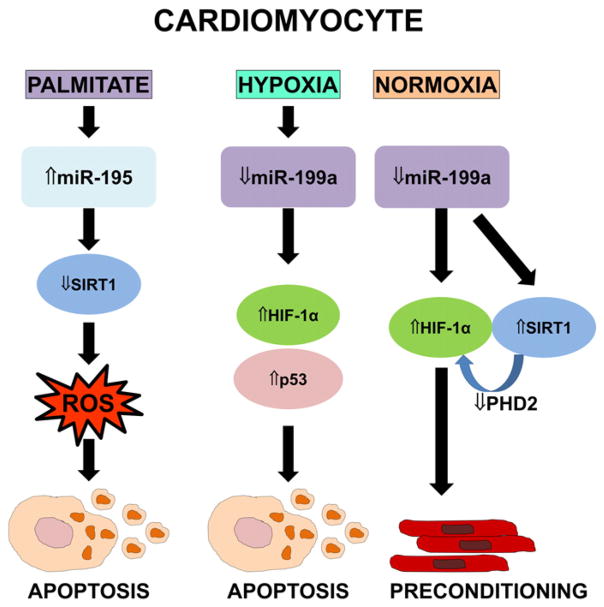

2.1.6.4. miR-195

In cardiomyocytes, the free fatty acid palmitate increases miR-195 levels, which in turn lowers SIRT1 production and promotes apoptosis, causing lipotoxic cardiomyopathy [117] (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

SIRT1 regulation by miRNAs in cardiomyocytes. In cardiomyocytes, the free fatty acid palmitate increases miR-195 levels, which in turn inhibits SIRT1 and promotes ROS-triggered apoptosis (left). In hypoxic cardiomyocytes, downregulation of miR-199a increases HIF-1α levels and p53-mediated cardiomyocyte apoptosis (center). In normoxic cardiomyocytes, low miR-199a raises SIRT1 and HIF-1α levels, simulating preconditioning (right).

2.1.6.5. miR-199

As shown in cardiomyocytes, the hypoxia-regulated miR-199a is another repressor of SIRT1 [118] (Fig. 6). Hypoxia acutely lowers miR-199a abundance, causing rapid upregulation of its target hypoxia inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) and triggering p53-dependent apoptosis. Similarly, inhibition of miR-199a during normoxia induces HIF-1α and SIRT1, which in turn downregulates PHD2, required for HIF-1α stabilization, and thus recapitulates hypoxia preconditioning.

2.2. lncRNAs

As previously noted, very little is known about lncRNAs and aging. However, given the variety of functions and biological mechanisms regulated by lncRNAs and considering the rapid progress in our knowledge of lncRNAs, it is likely that lncRNAs will prove to affect aging broadly. Here, we provide some emerging examples of lncRNAs implicated in regulating key features of aging and their dysregulation in a variety of age-related CVDs.

2.2.1. Senescence-associated long noncoding (SAL)RNAs

RNA-seqencing analysis of proliferating and senescent fibroblasts revealed numerous senescence-associated lncRNAs (SAL-RNAs) that were differentially expressed in senescent cells; some lncRNAs had been previously annotated, including antisense transcripts and pseudogene-encoded transcripts, while many others were novel lncRNAs [119] (Fig. 1). However, just as we have vastly incomplete knowledge of lncRNA function in general, the impact of lncRNAs on senescence is also almost entirely unknown. Some lncRNAs that are beginning to be implicated in senescence are:

2.2.1.1. Naturally occurring antisense lncRNAs (NA-SAL-RNAs)

Some NASAL-RNAs showing higher expression levels in senescent cells were those targeting the mRNAs that encode metallopeptidase ADAMTS19 and the secreted protein osteocrin. On the other hand, NA-SAL-RNAs less abundant in senescent cells targeted the mRNAs encoding versican (an extracellular matrix proteoglycan) and the limbic system-associated membrane protein (LSAMP).

2.2.1.2. LncRNAs encoded by pseudogenes (PE-SAL-RNAs)

PE-SAL-RNAs more highly expressed in senescent cells included the carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecules CEACAMP10 and CEACAMP11, while PE-SAL-RNAs lower in senescent cells include transcripts expressed from the ribosomal protein L21 pseudogene and from the heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A1 (HNRNPA1) pseudogene [120].

2.2.1.3. Other previously annotated lncRNAs

Among the previously annotated senescence-upregulated lncRNAs [119], HOTAIR functions as a scaffold factor for the ubiquitination and subsequent degradation of Ataxin-1 and Snurportin-1 mediated by E3 ubiquitin ligases [24]. By contrast, the well-known lncRNAs MALAT1, XIST, and MIAT/GOMAFU were less abundant in senescent cells. Silencing MALAT1 or MIAT enhanced cellular senescence, providing direct evidence that these lncRNAs were implicated in senescence [119]. Additionally, DNA-damage-activated p53 was necessary for the cell cycle arrest induced by MALAT1 [121]. The inhibition of cellular senescence by lncRNA 7SL was attributed, at least in part, to the repression of p53 translation by 7SL [120].

2.2.1.4. Novel differentially abundant SAL-RNAs

Among the novel differentially abundant SAL-RNAs identified in this screen, lncRNAs XLOC_023166, XLOC_025931 and XLOC_025918 modulated the onset of senescence and protected the viability of senescent cells [120].

2.2.2. LncRNAs and telomere shortening

Telomere shortening is a hallmark of aging and stress-induced senescence [122]. Telomere length critically affects cell senescence and organism life span. Accordingly, prevention of age-associated telomere shortening by telomerase activation increases both health and longevity [123]. A key component of the complex machinery regulating telomere length and erosion is the lncRNA family TERRA. Transcribed from the telomeres, TERRA lncRNAs associate with RNA-binding proteins such as hnRNPA1 and regulate telomerase activity. Only when the correct stoichiometry between TERRA and hnRNPA1 is achieved, telomerase is free to elongate telomeres and avoid erosion [124]. However, the impact of this mechanism upon age and age-associated CVDs remains unknown.

2.2.3. LncRNAs and age-associated CVDs

Even though the attention of the scientific community has only started to focus on lncRNAs in the past few years, several lncRNAs have been associated or causally linked to age-associated CVDs. Many further studies will be needed to discriminate lncRNAs that drive aging CVDs from those implicated only indirectly, but some information is already beginning to accumulate.

Sustained cardiac hypertrophy is often followed by maladaptive cardiac remodeling, which increases risk for HF. Recently, increased levels of CHRF were found in cardiomyocytes (CMs) treated with Angiotensin II (Ang II) to induce hypertrophy [125]. CHRF sponged and hence reduced the function of miR-489, lowering its activity in hypertrophic CMs; conversely, ectopic miR-489 expression in CMs and in transgenic mice reduced the hypertrophic influence of Ang II treatment.

In Pdk1-null mice, a different model of HF, Liu et al. identified several dysregulated lncRNAs [126]. Network and pathway analyses of these lncRNAs highlighted the involvement of the MAPK signaling pathway, which is causally involved in myocardial hypertrophy and HF [127]. Moreover, they identified MKK7, a sense overlapping lncRNA in the proximity of MAP2K7 (implicated in both HF and hypertrophy [126, 128]), as being downregulated in CMs in Pdk1-null mice.

Concerning naturally occurring antisense lncRNAs, cardiac troponin I (cTNI) is essential for normal sarcomere function in adult CMs and its expression appears to be regulated by cTNI sense-antisense duplexes [129]. Interestingly, cTNI expression levels correlate with ischemia and risk of HF, but the role of the antisense transcript in disease has not yet been evaluated.

Another interesting antisense lncRNA, NPPA-AS, modulates the alternative splicing of the NPPA (natriuretic peptide precursor A) pre-mRNA [130], which is usually expressed only in fetal atrial and ventricular myocardium. NPPA is re-expressed in patients exhibiting hypertrophy and HF [131], and is considered to be a marker for heart disease.

Very recently, an elegant study in mice identified a cluster of nuclear, cardiac-specific lncRNAs expressed from the Myh7 locus termed myosin heavy-chain-associated (Myheart or Mhrt) RNAs [132]. While abundant in adult mouse myocardium, Mhrt RNAs were downregulated in transaortic constriction (TAC)-induced HF, and this reduction coincided with a characteristic Myh6-to-Myh7 isoform switch. Mhrt transcription was inhibited by the Brg1–Hdac–Parp chromatin repressor complex 3, was activated by stress, and was essential for cardiomyopathy development. Accordingly, restoring Mhrt prevented heart hypertrophy and failure, indicating that Mhrt has a protective role in CVDs [132].

Reperfusion therapy is frequently used as treatment for AMI [133, 134]. However, after reperfusion therapy, patients often suffer from myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury and oxidative stress [135]. The levels of several lncRNAs are modulated at early stages of reperfusion following ischemia [136]. Zangrando et al. [137] showed that AMI in mice was associated with modulation of 30 lncRNAs; among these, myocardial infarction-associated transcript 1 (MIRT1) and 2 (MIRT2) lncRNAs showed robust upregulation. MIRT1 and MIRT2 expression levels were negatively correlated with infarct size and positively correlated with ejection fraction (EF). In addition, MIRT1 and MIRT2 correlated with the expression of multiple genes known to be involved in processes affecting left ventricular remodeling, such as inflammation, extracellular matrix turnover, fibrosis and apoptosis.

Finally, the chromosomal locus 9p21, which contains one of the strongest genetic susceptibility locus for CVDs and type 2 diabetes, spans 50 kb of DNA that do not contain protein-coding genes but do contain the lncRNA ANRIL (CDKN2A/INK4 locus) [138–141]. Accordingly, ANRIL expression is tightly regulated by the identified SNPs [142] and ANRIL expression levels positively correlate with atherosclerosis severity [143]. However, as a word of caution, multiple ANRIL transcripts have been identified (17 annotated in Ensembl so far, http://www.ensembl.org/Homo_sapiens/Gene/Summary?db=core;g=ENSG00000240498;r=9:21994778-22121097) and the results may differ among isoforms.

Functional studies showed that ANRIL expression stimulates cell proliferation, promotes adhesion, and decreases apoptosis, providing a potential disease mechanism, at least for atherosclerosis [144]. From a molecular perspective, ANRIL like several other lncRNAs, recruits Polycomb repressive complexes 1 and 2 and Polycomb-associated activating proteins RYBP and YY1, influencing gene expression both in cis and in trans [141].

3. Circulating ncRNAs

As illustrated in the previous sections, significant changes of tissue ncRNA ‘signatures’ occur in various diseases, including CVDs. However, routine biopsies for miRNA and/or lncRNA profiling are not clinically feasible. Given that some miRNAs are released from the cells of origin and can be measured in bodily fluids [145,146], extracellular miRNAs are remarkably stable in the circulation [147–150], and disease-specific miRNA signatures can be identified in fluids [151,152], investigators are turning to less invasive approaches such as miRNA biomarkers in circulation (e.g., in plasma or serum) [153–159]. Since distal tissues can take up circulating miRNAs, they may represent an important form of cell-to-cell communication [61,160,161]. Furthermore, very recent evidence show that lncRNAs are present in plasma/serum as well, and may potentially be used as biomarkers [146,162]. Plasma or serum ncRNA identified in age-related CVD are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Circulating ncRNAs and ncRNAs in age-related cardiovascular diseases.

| Disease/condition | Modulation | Refs | |

|---|---|---|---|

| miR-1 | Myocardial infarction | Up | [191–194] |

| miR-133 | Myocardial infarction | Up | [159,192] |

| miR-208a | Myocardial infarction | Up | [193] |

| miR-208b | Myocardial infarction | Up | [173,193] |

| miR-499 | Myocardial infarction | Up | [166,193,194] |

| miR-328 | Myocardial infarction | Up | [195] |

| miR-27b | Myocardial infarction | Down | [196] |

| miR-126 | Myocardial infarction | Down | [197] |

| miR-126, miR-92a, miR-17, miR-155, and miR-145 | Coronary artery disease | Down | [198] |

| miR-147 | Coronary artery disease | Down | [171] |

| miR-135 | Coronary artery disease | Up | [171] |

| miR-337-5p, miR-433, and miR-485-3p | Coronary artery disease | Up | [170] |

| miR-134, miR-198, and miR-370 | Unstable angina vs stable angina | Up | [171] |

| miR-106b, miR-25, miR-92a, miR-21, miR-590-5p, miR-126*, and miR-451 | Unstable angina vs stable angina | Up | [162] |

| miR-423-3p | Heart failure | Up | [172] |

| miR-499, -122 | Heart failure | Up | [173] |

| miR-126 | Heart failure | Down | [57] |

| miR-107, miR-139, miR-142-5p, miR-125b, and miR-497 | Heart failure | Down | [174] |

| miR-142-3p, miR-29b | Heart failure | Up | [174] |

| miR-503 | t2dm + critical limb ischemia | Up | [175] |

| ANRIL | Myocardial infarction | Down | [179] |

| aHIF | Myocardial infarction | Up | [179] |

| ANRIL, KCNQ1OT1 | Myocardial infarction | Down | [179] |

| LIPCAR | Myocardial infarction | Down | [181] |

3.1. Circulating microRNAs

3.1.1. MI

Altered levels of circulating miRNAs were detected in patients with AMI, some elevated (miR-1, miR-133, miR-208a/b, miR-499, miR-328), and some reduced (let-7b, miR-126) [153,163,164]. Many upregulated plasma miRNAs were highly expressed in myocytes and correlated with plasma cardiac troponin T (cTnT), suggesting that they were released from injured cardiomyocytes.

In an interesting commentary, Cui and Zao highlighted the importance of selecting the proper control group in this kind of studies and in general in all investigations aimed at identifying diagnostic markers [165]. Using healthy people as control group might artifactually increase the specificity of the diagnostic tests. Indeed, in clinical practice, patients often suffer from various other diseases, some of which might impact upon the biomarker under investigation.

Only a few studies have explored the specific. circulating microRNAs in geriatric patients. In acute non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) of the elderly, circulating miR-499-5p displayed a diagnostic accuracy superior to that of cTnT in patients with modest elevation at presentation [166]. Furthermore, circulating miR-499-5p levels were associated with 12-month cardiovascular mortality after NSTEMI in elderly subjects [167].

3.1.2. CAD

Plasma levels of EC-enriched miRNAs (miR-126, miR-17, and miR-92a), inflammation-associated miR-155, and smooth muscle-enriched miR-145 were reported to be significantly reduced in stable CAD patients compared to healthy controls [153,154,158,168,169]. In addition, miR-135a and miR-147 levels were found to be increased and decreased, respectively, in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from CAD patients. Recently, miR-337-5p, miR-433, and miR-485-3p expression levels were shown to be higher in CAD patients [170]. Interestingly, increased levels of miR-134, miR-198 and miR-370 [171], as well as miR-106b, miR-25, miR-92a, miR-21, miR-590-5p, miR-126* and miR-451 [162] were able to discriminate unstable from stable angina pectoris, suggesting that this miRNA signature could be used to identify patients at risk for acute coronary syndromes.

3.1.3. HF

A plethora of miRNAs have been found to be dysregulated in HF [153,154,158,168,169]: a) miR-423-5p, which correlates significantly with brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) levels and left ventricular ejection fraction [172]; b) elevated concentrations of miR-499 and miR-122 in acute HF [173]; and c) decreased levels of miR-126 in chronic HF, which correlated inversely with age and disease severity [57]. In addition, profiling PBMC miRNAs in both ischemic (ICM) and nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy (NIDCM) patients showed that miR-107, miR-139, and miR-142-5p levels were low in both HF classes, miR-142-3p and miR-29b levels increased only in NIDCM patients, and miR-125b and miR-497 levels decreased only in ICM patients [174].

3.1.4. Impaired peripheral angiogenesis

miR-503 contributed to the impaired peripheral angiogenic signaling in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and miR-503 plasma levels were elevated in diabetic patients with critical limb ischemia [175].

Finally, studies of the effects of CR on serum miRNAs in young and aged control mice have identified sets of miRNAs displaying increased levels with age and antagonization of this increase by CR [108]. Interestingly, the proteins predicted to be repressed by this set of age-modulated miRNAs are implicated in age-relevant biological processes, including metabolic changes [176–178]. It is tempting to speculate that serum miRNAs may participate in age-induced changes in physiology and pathology, and that their modulation may underlie, at least in part, the anti-aging effects of CR.

3.2. Circulating lncRNAs

Data on circulating lncRNAs are still emerging, and some of them are related to CVDs; however, so far, only one lncRNA was linked to aging. Vausort et al. [179] identified 5 dysregulated lncRNAs in peripheral blood cells of MI patients: aHIF, ANRIL, KCNQ1OT1, MIAT and MALAT1. The levels of aHIF, KCNQ1OT1 and MALAT1 were higher in AMI patients than in healthy volunteers, while the levels of ANRIL were lower in AMI patients. Patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) had lower levels of ANRIL, KCNQ1OT1, MIAT and MALAT1 compared to patients with non-STEMI patients. Lower levels of ANRIL were associated with advancing age, diabetes, and hypertension, while ANRIL and KCNQ1OT1 improved the prediction of left ventricular dysfunction [179].

Using microarrays, Li et al. [180] found several lncRNAs modulated in a mouse model of HF; 32 among these were simultaneously expressed in the heart, whole blood, and plasma, indicating their potential usefulness as HF biomarkers.

In global transcriptomic analyses on plasma RNA from patients with and without left ventricular remodeling after AMI, the mitochondrial lncRNA uc022bqs.1 (renamed LIPCAR) was found downregulated early after AMI but upregulated at later times following AMI [181]. Measurement of LIPCAR levels was successfully used to stratify patients with respect to their risk of developing cardiac remodeling, and to predict cardiac remodeling and cardiovascular death after HF.

4. Challenges and opportunities

Although the clinical value of ncRNAs is only beginning to surface, the available data already highlight opportunities for ncRNA-based therapies in age-related CVDs. MicroRNAs represent particularly attractive therapeutic targets, since they can be easily synthesized in both sense and antisense (inhibitory) orientation, modified for stability, and attached to medical devices and biomaterials. Strategies can be envisioned using ncRNAs as the therapeutic agents to be delivered ectopically. Reciprocally, the aim can also be to repress or neutralize pathologic endogenous ncRNAs. Preclinical studies adopting these approaches are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Effects of the administration of miRNAs and anti-miRNAs in animal models of CVDs.

| miR | Intervention | Effects | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|

| miR-15 | Inhibition | Infarct size reduction, cardiac remodeling, cardiac function improvement | [199] |

| miR ~ 17–92 | KO | Reduced proliferation | [200] |

| miR-24 | Inhibition | Infarct size reduction, cardiac and vascular function improvement | [201] |

| miR-29b | Inhibition | Reduced fibrosis | [202] |

| miR-320 | Inhibition | Infarct size reduction | [203] |

| miR-590/199a | Overexpression | Infarct size reduction, cardiac function improvement | [204] |

| miR-208a | KO, transgenic Inhibition | Hypertrophy reduction after trans-aorta binding | [205] |

| Cardiac remodeling reduction in Dahl rats | [206] | ||

| [207] | |||

| miR-132/212 family | Inhibition, KO | Protection from pressure overload-induced heart failure | [208] |

| miR-133 | Inhibition | Induction of cardiac hypertrophy | [209] |

| miR-21 | Inhibition | Fibrosis reduction after pressure overload | [70] |

| miR-101a/b | Overexpression | Fibrosis reduction after infarction | [210] |

| miR-24 | Inhibition | Prevention of decompensated hypertrophy | [211] |

| miR-22 | KO | Prevention of hypertrophy and remodeling | [212] |

| miR-199b | Inhibition | Prevention of hypertrophy and fibrosis in HF mouse model | [213] |

| miR-378 | Overexpression | Hypertrophy reduction after thoracic aortic constriction | [214] |

While no human experimentation targeting miRNAs has been started yet for CVDs, a phase I clinical trial for cancer therapy is ongoing using a mimic of miR-34a named MRX34 (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01829971). MRX34 is a liposome-formulated mimic of miR-34a, a microRNA showing decreased levels in many tumor types [182]. Moreover, the applicability of miRNA inhibition as a therapeutic tool is confirmed by the successful completion of a phase IIa clinical trial based on anti-miR-122 (NCT01200420) [183]. This study showed that locked nucleic acid (LNA)-anti-miRNA developed for hepatitis C therapy is effective, safe, and well tolerated.

LNA modifications might also be useful for inhibiting lncRNAs with GapmeRs, antisense oligonucleotides that contain a central stretch (gap) of DNA monomers flanked by blocks of LNA-modified nucleotides. The LNA-nucleotides increase the affnity for a target RNA and stability of the oligonucleotide, while the DNA forms a duplex DNA-RNA that is cleaved by RNase H. This tool is particularly useful to target nuclear transcripts that are poor RNAi substrates [184].

Many hurdles must be overcome to achieve clinically feasible strategies for ncRNA-based therapy, including the optimization of delivery systems and the chemistry of the therapeutic molecule. These obstacles are particularly challenging for lncRNAs, since they are longer, bulkier, and more labile. However, some of the lessons learned with mRNA-based gene therapy might prove useful for lncRNA-based interventions [185–187].

Delivering miRNAs as therapeutic agents offers a powerful tool for fine-tuning target proteins or pathways. A major potential drawback of this approach is the fact that one miRNA can theoretically affect many biological processes, not just a single gene product. However, this feature of microRNAs could be exploited for therapeutic gain in aging dysfunction and disease, if we wish to intervene in the broader molecular pathways regulated by the specific miRNA. To take full advantage of this trait, we must first understand in detail the actions of the miRNA in a relevant pathological context, before progressing to clinical application.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Ministero della Salute (SG and FM), Fondazione Cariplo grant #2013-0887 (SG and FM) and Telethon-Italy GGP14092 (FM). KM Kim assisted with illustrations. MG was supported by the NIA-IRP, NIH (AG000393-07).

Abbreviations

- 1/2-sbsRNAs

half-STAU1-binding site RNAs

- 53BP1

tumor suppressor p53-binding protein 1

- ANRIL

antisense noncoding RNA in the INK4 locus

- AP-1

activator protein 1

- ASF1/SF2

alternative splicing factor 1, pre-mRNA-splicing factor

- ATG5

autophagy-related 5

- BCL-2

B-cell lymphoma 2

- BECN

BECLIN 1, autophagy-related

- B-MYB

v-myb avian myeloblastosis viral oncogene homolog-like 2

- BNIP3

BCL2/adenovirus E1B 19 kDa protein-interacting protein 3

- Brg1 (Smarca4)

SWI/SNF related, matrix associated, actin dependent regulator of chromatin, subfamily a, member 4

- CDKN2A/INK4

cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A

- CEACAMP

carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule pseudogene

- CHFR

cardiac hypertrophy related factor

- COX10

cytochrome c oxidase assembly homolog 10

- ERK

extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- FECH

Ferrochelatase

- FIRRE

functional intergenic repeating RNA element

- GAS5

growth arrest-specific 5

- GMC-SF

granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor

- HDAC

histone deacetylase

- HMGA2

high-mobility group AT-hook 2

- HOTAIR

HOX transcript antisense RNA

- Id

DNA-binding protein, inhibitor

- IGF1

Insulin-linke growth factor 1

- IL1α

interleukin 1α

- IL-6

interleukin 6

- IL-8

interleukin 8

- IRAK1

interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase 1

- ISCU

iron–sulfur cluster assembly enzyme 1

- KCNQ1OT1

potassium voltage-gated channel, KQT-like subfamily, member 1 opposite strand 1

- LC3B-II/MAP1LC3B

microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 beta-II

- LincRNA

long intervening noncoding RNA

- LINCMD1

long noncoding RNA, muscle differentiation

- MALAT1

metastasis associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MCM5

minichromosome maintenance complex component 5

- MDC1

mediator of DNA-damage checkpoint protein 1

- MI

myocardial infarction

- MIAT/GOMAFU

myocardial infarction-associated transcript

- MKK7

MAP kinase kinase 7

- MMP-1

matrix metalloproteinase-1

- MMP-3

matrix metalloproteinase-3

- MYH6

myosin, heavy chain 6, cardiac muscle, alpha

- MYH7

myosin, heavy chain 7, cardiac muscle, beta

- NAD+

nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide

- NEAT1

nuclear enriched abundant transcript 1

- NFκBIB

nuclear factor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B cells inhibitor, beta

- NF-κB

nuclear factor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B cells

- NPPA

natriuretic peptide A

- NPPA-AS

natriuretic peptide A antisense RNA

- NRARP

notch-regulated ankyrin repeat protein

- Nrf2

NF-E2 related factor 2

- PARP

poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase

- PCGF4

polycomb group RING finger protein 4

- Pdk1

pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase, isozyme 1

- Ppp1r10

protein phosphatase 1, regulatory subunit 10

- RAR-γ

retinoic acid receptor gamma

- RB

retinoblastoma protein

- S6K1

ribosomal protein S6 kinase 1

- ShcA

Src homology 2 domain-containing

- SIRT1

silent mating type information regulation 2 homolog

- SPRY2

sprouty homolog 2

- SREBP-1c

sterol regulatory element-binding protein

- TERRA

telomeric repeat-containing RNA

- TRF2

telomeric repeat binding factor 2

- TUG1

taurine upregulated gene 1

- XIST

X-inactive specific transcript

- ZEB1

zinc finger E-box binding homeobox 1

- γ-H2AX

gamma-H2A histone family, member X

Footnotes

Disclosures

None.

References

- 1.Cech TR, Steitz JA. The noncoding RNA revolution-trashing old rules to forge new ones. Cell. 2014;157:77–94. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Salmanidis M, Pillman K, Goodall G, Bracken C. Direct transcriptional regulation by nuclear microRNAs. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2014;54c:304–11. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2014.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yoon JH, Abdelmohsen K, Gorospe M. Posttranscriptional gene regulation by long noncoding RNA. J Mol Biol. 2013;425:3723–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2012.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krol J, Loedige I, Filipowicz W. The widespread regulation of microRNA biogenesis, function and decay. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11:597–610. doi: 10.1038/nrg2843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Djebali S, Davis CA, Merkel A, Dobin A, Lassmann T, Mortazavi A, et al. Landscape of transcription in human cells. Nature. 2012;489:101–8. doi: 10.1038/nature11233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li L, Chang HY. Physiological roles of long noncoding RNAs: insight from knockout mice. Trends Cell Biol. 2014;24:594–602. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2014.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Small EM, Olson EN. Pervasive roles of microRNAs in cardiovascular biology. Nature. 2011;469:336–42. doi: 10.1038/nature09783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen LH, Chiou GY, Chen YW, Li HY, Chiou SH. MicroRNA and aging: a novel modulator in regulating the aging network. Ageing Res Rev. 2010;9(Suppl 1):S59–66. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fabian MR, Sonenberg N, Filipowicz W. Regulation of mRNA translation and stability by microRNAs. Annu Rev Biochem. 2010;79:351–79. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060308-103103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ha M, Kim VN. Regulation of microRNA biogenesis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15:509–24. doi: 10.1038/nrm3838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gorospe M, Abdelmohsen K. MicroRegulators come of age in senescence. Trends Genet. 2011;27:233–41. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jansson MD, Lund AH. MicroRNA and cancer. Mol Oncol. 2012;6:590–610. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fiore R, Siegel G, Schratt G. MicroRNA function in neuronal development, plasticity and disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1779:471–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2007.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kung JT, Colognori D, Lee JT. Long noncoding RNAs: past, present, and future. Genetics. 2013;193:651–69. doi: 10.1534/genetics.112.146704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spitale RC, Tsai MC, Chang HY. RNA templating the epigenome: long noncoding RNAs as molecular scaffolds. Epigenetics. 2011;6:539–43. doi: 10.4161/epi.6.5.15221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee JT. Epigenetic regulation by long noncoding RNAs. Science. 2012;338:1435–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1231776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bergmann JH, Spector DL. Long non-coding RNAs: modulators of nuclear structure and function. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2014;26:10–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2013.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gong C, Maquat LE. lncRNAs transactivate STAU1-mediated mRNA decay by duplexing with 3′ UTRs via Alu elements. Nature. 2011;470:284–8. doi: 10.1038/nature09701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yoon JH, Abdelmohsen K, Srikantan S, Yang X, Martindale JL, De S, et al. LincRNA-p21 suppresses target mRNA translation. Mol Cell. 2012;47:648–55. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.06.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mattick JS. Long noncoding RNAs in cell and developmental biology. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2011;22:327. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anko ML, Neugebauer KM. Long noncoding RNAs add another layer to pre-mRNA splicing regulation. Mol Cell. 2010;39:833–4. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cesana M, Cacchiarelli D, Legnini I, Santini T, Sthandier O, Chinappi M, et al. A long noncoding RNA controls muscle differentiation by functioning as a competing endogenous RNA. Cell. 2011;147:358–69. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.09.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tay Y, Rinn J, Pandolfi PP. The multilayered complexity of ceRNA crosstalk and competition. Nature. 2014;505:344–52. doi: 10.1038/nature12986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yoon JH, Abdelmohsen K, Kim J, Yang X, Martindale JL, Tominaga-Yamanaka K, et al. Scaffold function of long non-coding RNA HOTAIR in protein ubiquitination. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2939. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wapinski O, Chang HY. Long noncoding RNAs and human disease. Trends Cell Biol. 2011;21:354–61. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2011.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harries LW. Long non-coding RNAs and human disease. Biochem Soc Trans. 2012;40:902–6. doi: 10.1042/BST20120020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mozaffarian D, Afshin A, Benowitz NL, Bittner V, Daniels SR, Franch HA, et al. Population approaches to improve diet, physical activity, and smoking habits: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;126:1514–63. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e318260a20b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, Lim S, Shibuya K, Aboyans V, et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2095–128. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shioi T, Inuzuka Y. Aging as a substrate of heart failure. J Cardiol. 2012;60:423–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2012.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dai DF, Rabinovitch PS, Ungvari Z. Mitochondria and cardiovascular aging. Circ Res. 2012;110:1109–24. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.246140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Csiszar A, Ungvari Z, Edwards JG, Kaminski P, Wolin MS, Koller A, et al. Aging-induced phenotypic changes and oxidative stress impair coronary arteriolar function. Circ Res. 2002;90:1159–66. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000020401.61826.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lakatta EG. Arterial and cardiac aging: major shareholders in cardiovascular disease enterprises: part III: cellular and molecular clues to heart and arterial aging. Circulation. 2003;107:490–7. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000048894.99865.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gimbrone MA, Jr, Topper JN, Nagel T, Anderson KR, Garcia-Cardena G. Endothelial dysfunction, hemodynamic forces, and atherogenesis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;902:230–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06318.x. discussion 9–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ungvari Z, Sonntag WE, Csiszar A. Mitochondria and aging in the vascular system. JMol Med. 2010;88:1021–7. doi: 10.1007/s00109-010-0667-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lakatta EG, Levy D. Arterial and cardiac aging: major shareholders in cardiovascular disease enterprises: part I: aging arteries: a “set up” for vascular disease. Circulation. 2003;107:139–46. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000048892.83521.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee HY, Oh BH. Aging and arterial stiffness. Circ J. 2010;74:2257–62. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-10-0910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kato M, Slack FJ. Ageing and the small, non-coding RNA world. Ageing Res Rev. 2013;12:429–35. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2012.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Harries LW. MicroRNAs as mediators of the ageing process. Genes. 2014;5:656–70. doi: 10.3390/genes5030656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang X, Azhar G, Wei JY. The expression of microRNA and microRNA clusters in the aging heart. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e34688. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hayflick L. The limited in vitro lifetime of human diploid cell strains. Exp Cell Res. 1965;37:614–36. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(65)90211-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kuilman T, Michaloglou C, Mooi WJ, Peeper DS. The essence of senescence. Genes Dev. 2010;24:2463–79. doi: 10.1101/gad.1971610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Campisi J. Senescent cells, tumor suppression, and organismal aging: good citizens, bad neighbors. Cell. 2005;120:513–22. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rodier F, Campisi J. Four faces of cellular senescence. J Cell Biol. 2011;192:547–56. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201009094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tyner SD, Venkatachalam S, Choi J, Jones S, Ghebranious N, Igelmann H, et al. p53 mutant mice that display early ageing-associated phenotypes. Nature. 2002;415:45–53. doi: 10.1038/415045a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Baker DJ, Wijshake T, Tchkonia T, LeBrasseur NK, Childs BG, van de Sluis B, et al. Clearance of p16Ink4a-positive senescent cells delays ageing-associated disorders. Nature. 2011;479:232–6. doi: 10.1038/nature10600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fenton M, Barker S, Kurz DJ, Erusalimsky JD. Cellular senescence after single and repeated balloon catheter denudations of rabbit carotid arteries. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001;21:220–6. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.21.2.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Minamino T, Miyauchi H, Yoshida T, Ishida Y, Yoshida H, Komuro I. Endothelial cell senescence in human atherosclerosis: role of telomere in endothelial dysfunction. Circulation. 2002;105:1541–4. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000013836.85741.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Abdelmohsen K, Kuwano Y, Kim HH, Gorospe M. Posttranscriptional gene regulation by RNA-binding proteins during oxidative stress: implications for cellular senescence. Biol Chem. 2008;389:243–55. doi: 10.1515/BC.2008.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell. 2009;136:215–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Borgdorff V, Lleonart ME, Bishop CL, Fessart D, Bergin AH, Overhoff MG, et al. Multiple microRNAs rescue from Ras-induced senescence by inhibiting p21(Waf1/Cip1) Oncogene. 2010;29:2262–71. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Marasa BS, Srikantan S, Masuda K, Abdelmohsen K, Kuwano Y, Yang X, et al. Increased MKK4 abundance with replicative senescence is linked to the joint reduction of multiple microRNAs. Sci Signal. 2009;2:ra69. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Afanasyeva EA, Mestdagh P, Kumps C, Vandesompele J, Ehemann V, Theissen J, et al. MicroRNA miR-885-5p targets CDK2 and MCM5, activates p53 and inhibits proliferation and survival. Cell Death Differ. 2011;18:974–84. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2010.164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Boon RA, Seeger T, Heydt S, Fischer A, Hergenreider E, Horrevoets AJ, et al. MicroRNA-29 in aortic dilation: implications for aneurysm formation. Circ Res. 2011;109:1115–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.255737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Olivieri F, Lazzarini R, Recchioni R, Marcheselli F, Rippo MR, Di Nuzzo S, et al. MiR-146a as marker of senescence-associated pro-inflammatory status in cells involved in vascular remodelling. Age (Dordr) 2013;35:1157–72. doi: 10.1007/s11357-012-9440-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Olivieri F, Spazzafumo L, Santini G, Lazzarini R, Albertini MC, Rippo MR, et al. Age-related differences in the expression of circulating microRNAs: miR-21 as a new circulating marker of inflammaging. Mech Ageing Dev. 2012;133:675–85. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2012.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Asgeirsdottir SA, van Solingen C, Kurniati NF, Zwiers PJ, Heeringa P, van Meurs M, et al. MicroRNA-126 contributes to renal microvascular heterogeneity of VCAM-1 protein expression in acute inflammation. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2012;302:F1630–9. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00400.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fukushima Y, Nakanishi M, Nonogi H, Goto Y, Iwai N. Assessment of plasma miRNAs in congestive heart failure. Circ J. 2011;75:336–40. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-10-0457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Feng X, Wang H, Ye S, Guan J, Tan W, Cheng S, et al. Up-regulation of microRNA-126 may contribute to pathogenesis of ulcerative colitis via regulating NF-kappaB inhibitor IkappaBalpha. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e52782. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wei Y, Nazari-Jahantigh M, Neth P, Weber C, Schober A. MicroRNA-126, -145, and -155: a therapeutic triad in atherosclerosis? Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2013;33:449–54. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.300279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kim S, Iwao H. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of angiotensin II-mediated cardiovascular and renal diseases. Pharmacol Rev. 2000;52:11–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Boon RA, Iekushi K, Lechner S, Seeger T, Fischer A, Heydt S, et al. MicroRNA-34a regulates cardiac ageing and function. Nature. 2013;495:107–10. doi: 10.1038/nature11919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bradshaw AD, Baicu CF, Rentz TJ, Van Laer AO, Bonnema DD, Zile MR. Age-dependent alterations in fibrillar collagen content and myocardial diastolic function: role of SPARC in post-synthetic procollagen processing. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;298:H614–22. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00474.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Burgess ML, McCrea JC, Hedrick HL. Age-associated changes in cardiac matrix and integrins. Mech Ageing Dev. 2001;122:1739–56. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(01)00296-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Swinnen M, Vanhoutte D, Van Almen GC, Hamdani N, Schellings MW, D’Hooge J, et al. Absence of thrombospondin-2 causes age-related dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2009;120:1585–97. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.863266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang M, Zhang J, Walker SJ, Dworakowski R, Lakatta EG, Shah AM. Involvement of NADPH oxidase in age-associated cardiac remodeling. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2010;48:765–72. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.St John Sutton M, Pfeffer MA, Moye L, Plappert T, Rouleau JL, Lamas G, et al. Cardiovascular death and left ventricular remodeling two years after myocardial infarction: baseline predictors and impact of long-term use of captopril: information from the Survival and Ventricular Enlargement (SAVE) trial. Circulation. 1997;96:3294–9. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.10.3294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gould KE, Taffet GE, Michael LH, Christie RM, Konkol DL, Pocius JS, et al. Heart failure and greater infarct expansion in middle-aged mice: a relevant model for postinfarction failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;282:H615–21. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00206.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Minamino T, Komuro I. Vascular cell senescence: contribution to atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 2007;100:15–26. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000256837.40544.4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.van Almen GC, Verhesen W, van Leeuwen RE, van de Vrie M, Eurlings C, Schellings MW, et al. MicroRNA-18 and microRNA-19 regulate CTGF and TSP-1 expression in age-related heart failure. Aging Cell. 2011;10:769–79. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Thum T, Gross C, Fiedler J, Fischer T, Kissler S, Bussen M, et al. MicroRNA-21 contributes to myocardial disease by stimulating MAP kinase signalling in fibroblasts. Nature. 2008;456:980–4. doi: 10.1038/nature07511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Duisters RF, Tijsen AJ, Schroen B, Leenders JJ, Lentink V, van der Made I, et al. miR-133 and miR-30 regulate connective tissue growth factor: implications for a role of microRNAs in myocardial matrix remodeling. Circ Res. 2009;104:170–8. 6–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.182535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Oldham S. Obesity and nutrient sensing TOR pathway in flies and vertebrates: Functional conservation of genetic mechanisms. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2011;22:45–52. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Curtis B, Lage MJ. Glycemic control among patients with type 2 diabetes who initiate basal insulin: a retrospective cohort study. J Med Econ. 2014;17:21–31. doi: 10.3111/13696998.2013.862538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bornfeldt KE. 2013 Russell Ross memorial lecture in vascular biology: cellular and molecular mechanisms of diabetes mellitus-accelerated atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014;34:705–14. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.301928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yu Q, Gao F, Ma XL. Insulin says NO to cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc Res. 2011;89:516–24. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvq349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cersosimo E, DeFronzo RA. Insulin resistance and endothelial dysfunction: the road map to cardiovascular diseases. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2006;22:423–36. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Curtis R, Geesaman BJ, DiStefano PS. Ageing and metabolism: drug discovery opportunities. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2005;4:569–80. doi: 10.1038/nrd1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yu XY, Song YH, Geng YJ, Lin QX, Shan ZX, Lin SG, et al. Glucose induces apoptosis of cardiomyocytes via microRNA-1 and IGF-1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;376:548–52. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Elia L, Contu R, Quintavalle M, Varrone F, Chimenti C, Russo MA, et al. Reciprocal regulation of microRNA-1 and insulin-like growth factor-1 signal transduction cascade in cardiac and skeletal muscle in physiological and pathological conditions. Circulation. 2009;120:2377–85. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.879429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Shan ZX, Lin QX, Fu YH, Deng CY, Zhou ZL, Zhu JN, et al. Upregulated expression of miR-1/miR-206 in a rat model of myocardial infarction. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;381:597–601. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.02.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Li Y, Higashi Y, Itabe H, Song YH, Du J, Delafontaine P. Insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor activation inhibits oxidized LDL-induced cytochrome C release and apoptosis via the phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase/Akt signaling pathway. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:2178–84. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000099788.31333.DB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Delafontaine P, Brink M. The growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor 1 axis in heart failure. Ann Endocrinol. 2000;61:22–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ungvari Z, Parrado-Fernandez C, Csiszar A, de Cabo R. Mechanisms underlying caloric restriction and lifespan regulation: implications for vascular aging. Circ Res. 2008;102:519–28. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.168369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Valcarcel-Ares MN, Gautam T, Warrington JP, Bailey-Downs L, Sosnowska D, de Cabo R, et al. Disruption of Nrf2 signaling impairs angiogenic capacity of endothelial cells: implications for microvascular aging. J Gerontol A: Biol Med Sci. 2012;67:821–9. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glr229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Green DR, Galluzzi L, Kroemer G. Mitochondria and the autophagy-inflammation-cell death axis in organismal aging. Science. 2011;333:1109–12. doi: 10.1126/science.1201940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Napoli C, de Nigris F, Palinski W. Multiple role of reactive oxygen species in the arterial wall. J Cell Biochem. 2001;82:674–82. doi: 10.1002/jcb.1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Tsutsui H, Kinugawa S, Matsushima S. Oxidative stress and heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;301:H2181–90. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00554.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Magenta A, Greco S, Gaetano C, Martelli F. Oxidative stress and microRNAs in vascular diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14:17319–46. doi: 10.3390/ijms140917319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Magenta A, Cencioni C, Fasanaro P, Zaccagnini G, Greco S, Sarra-Ferraris G, et al. miR-200c is upregulated by oxidative stress and induces endothelial cell apoptosis and senescence via ZEB1 inhibition. Cell Death Differ. 2011;18:1628–39. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2011.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zaccagnini G, Martelli F, Fasanaro P, Magenta A, Gaetano C, Di Carlo A, et al. p66ShcA modulates tissue response to hindlimb ischemia. Circulation. 2004;109:2917–23. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000129309.58874.0F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Baseler WA, Thapa D, Jagannathan R, Dabkowski ER, Croston TL, Hollander JM. miR-141 as a regulator of the mitochondrial phosphate carrier (Slc25a3) in the type 1 diabetic heart. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2012;303:C1244–51. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00137.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]