Abstract

There is increasing evidence that the predisposition for development of chronic diseases arises at the earliest times of life. In this context, maternal pre-pregnancy weight might modify fetal metabolism and the child’s predisposition to develop disease later in life. The aim of this study is to investigate the association between maternal pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI) and miRNA alterations in placental tissue at birth. In 211 mother-newborn pairs from the ENVIRONAGE birth cohort, we assessed placental expression of seven miRNAs important in crucial cellular processes implicated in adipogenesis and/or obesity. Multiple linear regression models were used to address the associations between pre-pregnancy BMI and placental candidate miRNA expression. Maternal pre-pregnancy BMI averaged (±SD) 23.9 (±4.1) kg/m2. In newborn girls (not in boys) placental miR-20a, miR-34a and miR-222 expression was lower with higher maternal pre-pregnancy BMI. In addition, the association between maternal pre-pregnancy BMI and placental expression of these miRNAs in girls was modified by gestational weight gain. The lower expression of these miRNAs in placenta in association with pre-pregnancy BMI, was only evident in mothers with low weight gain (<14 kg). The placental expression of miR-20a, miR-34a, miR-146a, miR-210 and miR-222 may provide a sex-specific basis for epigenetic effects of pre-pregnancy BMI.

Introduction

Detrimental effects of a disturbed intrauterine environment, caused by maternal inadequate nutrition before and during pregnancy, on fetal growth and the development of metabolic disease in adult life were first reported by Barker1. Prevalence of obesity is increasing worldwide, posing a high risk for pregnancy complications2. In utero exposure to maternal obesity has a key role in adverse pregnancy outcomes (pre-eclampsia, gestational diabetes, gestational hypertension, infant mortality and prematurity), fetal development (large for gestational age, congenital anomalies) and metabolic programming3, 4. Particularly, a maternal obesogenic environment has been associated with increased systolic blood pressure in offspring5, development of schizophrenia, elevated levels of cholesterol and triglycerides, impaired glucose tolerance, obesity and cardiovascular risk in childhood2, 6 and in adulthood7. Induction of oxidative stress and chronic inflammation in newborns8, 9 and children10 has been linked to maternal obesity during pregnancy. There is increasing evidence that in utero exposures can influence birth outcomes via epigenetic mechanisms including microRNA (miRNA) expression11. MiRNAs can regulate expression of up to one-third of the human genome12 and are involved in many physiological processes influencing adverse health outcomes in later life, including obesity and diabetes11. As such, miRNAs are implicated in adipocyte differentiation, metabolic integration, insulin resistance and appetite regulation, all of which are relevant for the onset and development of obesity13.

Numerous studies have focused on the role of miRNAs in pregnancy complications, including pre-eclampsia, prematurity and gestational diabetes mellitus14. Although several miRNAs have been linked to BMI in adults15, 16, evidence on the association between maternal pre-pregnancy BMI and fetal miRNA expression is very limited.

We selected a set of seven miRNAs previously shown to be expressed in human placental tissue or cell lines (Table 1), all of which are known to be related to crucial processes involved in the ontogeny or maintenance of obesity, such as inflammation17, oxidative stress18, apoptosis19, cell cycle20 and angiogenesis21: miR-1622, miR-20a23, miR-2124, miR-34a25, miR-146a26, miR-21027 and miR-22228 (Table 5).

Table 1.

Relevant studies of the studied candidate miRNAs on human placental tissue or cell lines.

| miRNA | Function | Pathologic or Physiologic condition/Exposure | Biological system | Regulation | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-16 | Cell cycle & apoptosis | Development | Placenta | +BW, −SGA & −NAS | 66, 85 |

| Pre-eclampsia | Placenta | − | 67 | ||

| Cigarrete smoke | Placenta | + | 37 | ||

| miR-20a | Cell proliferation & invasion, angiogenesis | Pre-eclampsia | Placenta & BeWo cells | + | 68 |

| Pre-eclampsia | JEG-3 cells | + | 69 | ||

| Trimester-specific PM2.5 | Placenta | +/− | 65 | ||

| miR-21 | Cell cycle & proliferation | Development | Placenta | +BW & −SGA | 70, 85 |

| Cigarrete smoke | Placenta | − | 37 | ||

| Trimester-specific PM2.5 | Placenta | +/− | 65 | ||

| miR-34a | Cell growth & invasion | Placenta accreta | JAR cells & placenta | − | 63 |

| Cervical cancer | BeWo & JAR cells | + | 71 | ||

| Pre-eclampsia | Placenta | − | 86 | ||

| miR-146a | Inflammation | Development | Placenta | +MS | 66 |

| Pre-eclampsia | Placenta | − | 68 | ||

| BSA | Trophoblast cells | + | 72 | ||

| Nicotine&BaP/Cigarrete smoke | TCL-1 cells & placenta | − | 37 | ||

| Trimester-specific PM2.5 | Placenta | − | 65 | ||

| miR-210 | Hypoxia/Oxidative stress | Preeclampsia | Placenta | + | 73 |

| miR-222 | Angiogenesis | Pre-eclampsia | Placenta | + | 67 |

| Gestational Diabetes | Placenta | − | 74 | ||

| Trimester-specific PM2.5 | Placenta | − | 65 |

BW: birth weight, NAS: neonatal attention scores, SGA: small gestational age, BeWo, JEG-3 & JAR cells: trophoblast choriocarcinoma cell lines, TCL-1 cells: extravillous trophoblast from choriodecidua of a term placenta, MS: movement scores, BSA: bisphenol A, BaP: Benzopyrene.

Table 5.

Measured miRNAs related to key processes implicated in obesity.

| miRNA | Regulation | Function | Biological system | Target | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-16 | ↑ | Inhibition of blood vessel formation & migration of trophoblast cells | Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells | ↓CCNE1 & VEGFA | 75 |

| ↓ | Weight loss in severe obesity (surgery-induced) | Human Plasma | 22 | ||

| miR-20a | ↑ | Inhibition of spheroid cell sprouting, network formation & cell migration | Human Endothelial Cells | 76 | |

| ↑ | Adipogenesis | Mouse Adipocytes (3T3L1) | ↓Rb2 | 23 | |

| miR-21 | ↑ | Inhibition of cell proliferation, migration & tubulogenesis | Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells | ↓RhoB | 77 |

| ↑ | Adipogenesis | Human Adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal Stem Cells (hASCs) | ↓TGFBR2 | 24 | |

| ↑ | Weight loss in severe obesity (surgery-induced) | Human Plasma | 22 | ||

| miR-34a | ↑ | Inhibition of angiogenesis by induction of senescence | Rat Endothelial Progenitor Cells | ↓SIRT1 | 78 |

| ↓ | Reduced adiposity | Murine White/Brown Adipose Tissue | ↑FGF21 & SIRT1 | 25 | |

| ↑ | Adipogenesis | Human mature adipocytes | 39 | ||

| miR-146a | ↑ | Weight loss in severe obesity (surgery-induced) | Human Plasma | 22 | |

| ↑ | Increased cell migration, tube formation & angiogenesis | Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells | ↓CARD10 & NF-kB | 79 | |

| ↓ | Inflammation/ Increased insulin resistance | Human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (Diabetic patients)/ Human Serum | ↑TNFα/↑IL-8 & HGF | 26 | |

| miR-210 | ↓ | Decreased tubulogenesis & cell migration (normoxic conditions) | Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells | 80 | |

| ↑ | Enhanced angiogenesis | Human endothelial cells | 36 | ||

| ↓ | Adipogenesis | Human mature adipocytes | 39 | ||

| ↑ | Maternal Obesity | Human placenta (girls) | ↑TNFα | 38 | |

| miR-222 | ↑ | Reduced tube formation, migration & wound healing | Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells | ↓KIT & eNOS | 81, 82 |

| ↑ | Inhibition cell migration | Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells | ↓ETS1 | 83 | |

| ↓ | Inflammation-mediated vascular growth factors | Human Endothelial Cells | ↑STAT5a | 45 | |

| ↓ | Adipogenesis | Human mature adipocytes | 39 | ||

| ↑ | Severe obesity | Human Plasma (men or children) | 22, 84 |

CARD10: Caspase Recruitment Domain Family, Member 10, CCNE1: Cyclin E1, eNOS: endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase 3, ETS1: V-Ets Avian Erythroblastosis Virus E26 Oncogene Homolog 1, FGF21: Fibroblast growth factor 21, HGF: Hepatocyte growth factor, IL-8: Interleukin 8, NF-kB: Nuclear Factor Of Kappa Light Polypeptide Gene Enhancer In B-Cells, KIT: V-Kit Hardy-Zuckerman 4 Feline Sarcoma Viral Oncogene Homolog, Rb2: Retinoblastoma-like protein 2, RhoB: Ras Homolog Family Member B, SIRT1: Sirtuin 1, STAT5a: Signal transducer and activator of transcription 5A, TGFBR2: Transforming Growth Factor, Beta Receptor II, TNFa: Tumor necrosis factor a, VEGFA: Vascular endothelial growth factor A.

We hypothesize that maternal pre-pregnancy BMI affects newborn’s epigenetic changes through differential miRNA expression in placental tissue at birth, which may provide further insights into mechanisms underlying these potential associations.

Results

General characteristics of the study population

Demographic characteristics of 211 mother-newborn pairs are given in Table 2. The mothers had an average (±SD) age of 29.5 (±4.3) years and an average (±SD) maternal pre-pregnancy BMI of 23.9 (±4.1) kg/m2. 49 (23.2%) of the mothers were overweight and 19 (9.0%) were obese, while 6 (2.8%) were underweight. Based on the Institute of Medicine (IOM) recommendations29 on the maternal gestational weight gain, 44.5% (n = 94) had an excessive weight gain, while 38.4% (n = 81) had a normal weight gain. The newborns, among them 112 girls (53.1%), had a mean (range) gestational age of 39.2 (35–41) weeks and comprised of 103 (48.8%) primiparous and 85 (40.3%) secundiparous newborns. The mean (±SD) birth weight of the newborns was 3413 (±447) grams. About 90.1% (n = 190) of the newborns were Europeans of Caucasian ethnicity and 3.3% delivered by Caesarian section (C-section). The average (±SD) gestational weight gain was 14.9 (±5.8) kg. Most of the mothers (71.1%) never smoked cigarettes and 57.8% had a high educational level.

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of study population (n = 211).

| Characteristics | Mean ± SD/Frequency (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Both genders (n = 211) | Boys (n = 99) | Girls (n = 112) | |

| Maternal | |||

| Age, years | 29.5 ± 4.3 | 29.2 ± 4.3 | 29.7 ± 4.2 |

| Pre-gestational weight, kg | 66.5 ± 13.3 | 66.9 ± 11.8 | 66.2 ± 14.5 |

| Height, m | 1.67 ± 0.1 | 1.67 ± 0.1 | 1.67 ± 0.1 |

| Pre-pregnancy BMI, kg/m2 | 23.9 ± 4.1 | 24.1 ± 3.7 | 23.7 ± 4.4 |

| Gestational weight gain, kg | 14.9 ± 5.8 | 14.7 ± 5.3 | 15.1 ± 6.2 |

| BMI at delivery, kg/m2 | 29.3 ± 4.5 | 29.5 ± 3.8 | 29.1 ± 5.1 |

| Smoking status | |||

| Never-smoker | 150 (71.1) | 68 (68.7) | 82 (73.2) |

| Past-smoker | 31 (14.7) | 14 (14.1) | 17 (15.2) |

| Current- smoker | 30 (14.2) | 17 (17.2) | 13 (11.6) |

| Parity | |||

| 1 | 103 (48.8) | 49 (49.5) | 54 (48.2) |

| 2 | 85 (40.3) | 38 (38.4) | 47 (42.0) |

| ≥3 | 23 (10.9) | 12 (12.1) | 11 (9.8) |

| Education | |||

| Low | 24 (11.4) | 11 (11.1) | 13 (11.6) |

| Middle | 65 (30.8) | 38 (38.4) | 27 (24.1) |

| High | 122 (57.8) | 50 (50.5) | 72 (64.3) |

| Gestational diabetes | 5 (2.7) | 3 (3.0) | 2 (1.8) |

| Hypertension | 5 (2.7) | 2 (2.0) | 3 (2.7) |

| Hyper/Hypothyroidism | 4 (1.9) | 1 (1.0) | 3 (2.7) |

| Pre-eclampsia | 2 (0.9) | — | 2 (1.8) |

| Asthma | 2 (0.9) | 1 (1.0) | 1 (0.9) |

| Gastric band | 3 (1.4) | 2 (2.0) | 1 (0.9) |

| Newborn | |||

| Gestational age, weeks | 39.2 ± 1.3 | 39.1 ± 1.4 | 39.3 ± 1.2 |

| Birth weight, g | 3,413 ± 447 | 3,466 ± 476 | 3,366 ± 416 |

| Ethnicity | |||

| European-Caucasian | 190 (90.1) | 87 (87.9) | 103 (92.0) |

| Non-European | 21 (9.9) | 12 (12.1) | 9 (8.0) |

| C-section | 7 (3.3) | 5 (5.1) | 2 (1.8) |

| Other | |||

| Outdoor Temperature, °C | |||

| Third trimester (quartiles) | |||

| <5.6 | 51 (24.2) | 23 (23.2) | 28 (25.0) |

| ≥5.6 and <9.4 | 54 (25.6) | 23 (23.2) | 31 (27.7) |

| ≥9.4 and <14.8 | 52 (24.6) | 27 (27.3) | 25 (22.3) |

| ≥14.8 | 54 (25.6) | 26 (26.3) | 28 (25.0) |

Within our study population, two pregnant women (0.9%) had a diagnosis of pre-eclampsia, five mothers (2.7%) were diagnosed with gestational diabetes, five mothers (2.7%) had hypertension, four (1.9%) had hyper- or hypothyroidism and two mothers (0.9%) had asthma. Three mothers (1.4%) underwent gastric banding surgery for weight loss prior to their pregnancy.

Association of maternal pre-pregnancy BMI, gestational weight gain and BMI at delivery with placental miRNA expression at birth

Placental relative expression of miRNAs did not differ between girls and boys, did not correlate with maternal age, gestational duration, parity and maternal education. To allow for potential non-linear associations between placental miRNA expression and outdoor temperature, we categorized temperature based on quartiles and found that miRNA expression was positively correlated with low outdoor temperature.

Independent of newborn’s ethnicity and gestational age, maternal age, smoking status, educational status, parity, gestational weight gain, health complications, delivery by C-section and outdoor temperature during third trimester, placental expression miR-20a (−5.85%, [CI: −10.91, −0.50, p = 0.035]), miR-34a (−8.85%, [CI: −15.22, −2.00, p = 0.014]) and miR-222 (−4.64%, [CI: −9.23, 0.18, p = 0.062]) were lower with increasing maternal pre-pregnancy BMI in newborn girls but not in newborn boys (Table 3).

Table 3.

Changes (%) in placental relative miRNA expression associated with maternal pre-pregnancy BMI, gestational weight gain and BMI at delivery.

| miRNAs | Pre-pregnancy BMIa | Gestational weight gainb | BMI at deliveryb | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % change (95% CI) | P-value | % change (95% CI) | P-value | % change (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Girls (n = 112) | ||||||

| miR-16 | −4.26 (−9.28, 1.05) | 0.12 | 0.57 (−3.11, 4.39) | 0.77 | −2.98 (−7.27, 1.51) | 0.19 |

| miR-20a | −5.85 (−10.91, −0.50) | 0.035 | 1.21 (−2.57, 5.13) | 0.54 | −3.87 (−8.25, 0.72) | 0.10 |

| miR-21 | −4.65 (−10.69, 1.80) | 0.16 | 0.98 (−3.48, 5.65) | 0.67 | −3.08 (−8.26, 2.39) | 0.27 |

| miR-34a | −8.85 (−15.22, −2.00) | 0.014 | −1.45 (−6.14, 3.46) | 0.56 | −7.90 (−13.32, −2.15) | 0.009 |

| miR-146a | −4.77 (−9.76, 0.50) | 0.078† | −2.60 (−6.92, 1.93) | 0.26¥ | −3.40 (−7.72, 1.13) | 0.14 |

| miR-210 | −4.95 (−11.19, 1.72) | 0.14† | −4.15 (−9.48, 1.49) | 0.15¥ | −4.64 (−9.94, 0.97) | 0.11 |

| miR-222 | −4.84 (−9.38, −0.09) | 0.049† | −1.99 (−5.95, 2.12) | 0.34¥ | −3.43 (−7.34, 0.65) | 0.10 |

| Boys (n = 99) | ||||||

| miR-16 | 0.20 (−6.35, 7.21) | 0.95 | 2.73 (−2.21, 7.91) | 0.29 | 0.99 (−5.36, 7.76) | 0.77 |

| miR-20a | −2.99 (−9.57, 4.07) | 0.40 | 2.31 (−2.80, 7.69) | 0.38 | −2.10 (−8.49, 4.74) | 0.54 |

| miR-21 | −2.58 (−9.85, 5.28) | 0.51 | 0.06 (−5.44, 5.89) | 0.98 | −2.61 (−9.55, 4.87) | 0.48 |

| miR-34a | 4.01 (−5.34, 14.29) | 0.42 | 2.03 (−4.26, 8.73) | 0.54 | 3.81 (−5.09, 13.55) | 0.42 |

| miR-146a | −1.97 (−8.14, 4.62) | 0.55 | 0.80 (−3.87, 5.70) | 0.74 | −1.74 (−7.66, 4.56) | 0.58 |

| miR-210 | −3.81 (−11.65, 4.71) | 0.37 | 5.45 (−0.89, 12.19) | 0.097 | −1.61 (−9.44, 6.91) | 0.70 |

| miR-222 | −0.76 (−6.76, 5.63) | 0.81 | 3.85 (−0.77, 8.69) | 0.11 | 0.84 (−5.08, 7.13) | 0.79 |

Estimates (95% confidence intervals) for a 1 kg/m2 increase in BMI or for a 1 kg increment in gestational weight gain.

aAdjusted for newborn’s ethnicity and gestational age, maternal age, smoking status, educational status, parity, gestational weight gain, health complications, delivery by C-section and outdoor temperature during the third trimester of pregnancy.

bAdjusted for same set of covariates except gestational weight gain.

†Additionally adjusted for the interaction between pre-pregnancy BMI and gestational weight gain. Estimate for a gestational weight gain of 14 kg (50th percentile).

¥Additionally adjusted for the interaction between pre-pregnancy BMI and gestational weight gain. Estimate for a pre-pregnancy BMI of 23 kg/m2 (50th percentile).

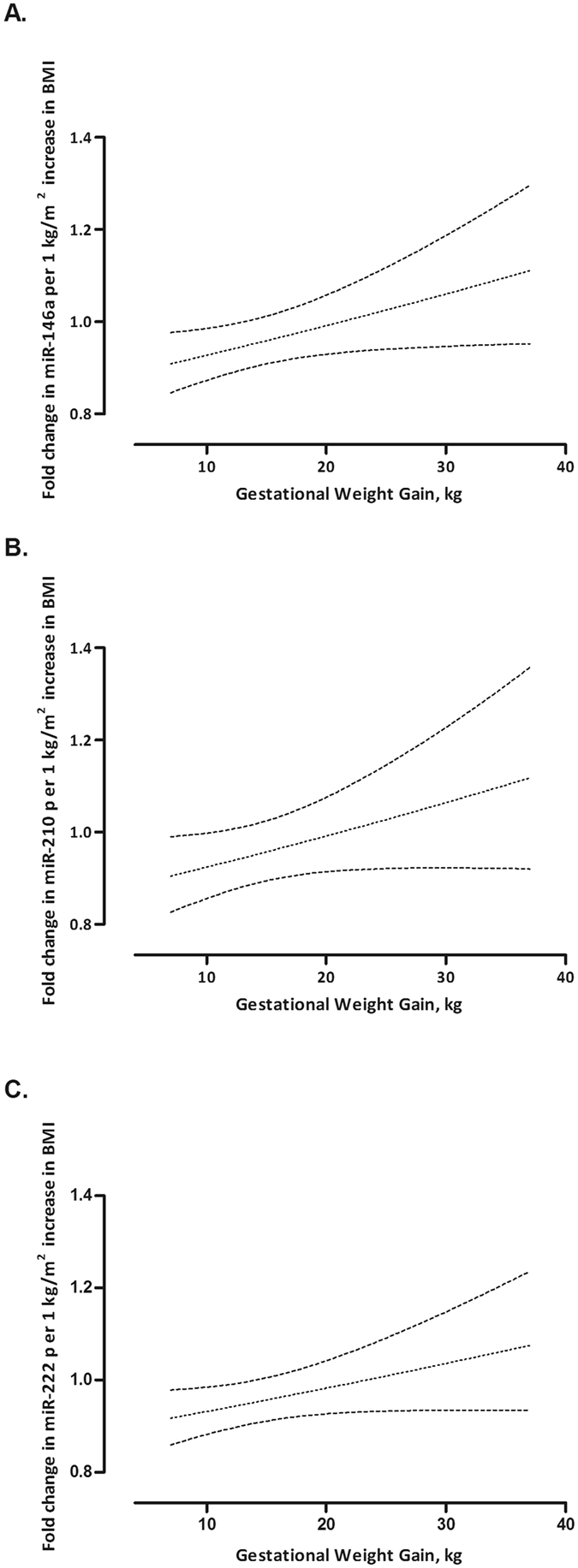

With similar adjustments as before, we explored the interaction between pre-pregnancy BMI and weight gain during pregnancy using continuous nature of the variables. These interaction terms were not significant for miR-16, miR-20a, miR-21 and miR-34a, but borderline significant (p interaction < 0.10) for miR-210 and miR-222, and significant for miRNA-146a (p = 0.043), only in girls. In addition, in girls the associations between pre-pregnancy BMI and placental miRNAs (miR-146a, miR-210 and miR-222) which were found to be modified by the gestational weight gain are illustrated in Figure 1. Placental miR-146a (−6.66%, [CI: −11.92, −1.09, p = 0.022]), miR-210 (−6.94%, [CI: −13.50, 0.12, p = 0.057) and miR-222 (−6.34%, [CI: −11.14, −1.29, p = 0.016]) expression was inversely associated with each increase of 1 unit (1 kg/m2) in mother’s pre-pregnancy BMI for a gestational weight gain of 11 kg (corresponding to 25th percentile). The association was not significant in mothers with a gestational weight gain above approximately 14 kg. Table 4 provides the predicted effect sizes, for an increase in pre-pregnancy BMI for 1 kg/m² and for 7, 11, 14, 18 and 25 kg increase in gestational weight gain. These adjusted estimates accounted for the aforementioned covariates and include the interaction between pre-pregnancy BMI and gestational weight gain.

Figure 1.

Effect modification by gestational weight gain on the association between maternal pre-pregnancy BMI and placental expression of miR-146a (panel A), miR-210 (panel B) and miR-222 (panel C) in newborn girls.

Table 4.

Changes (%) in placental miRNA (miR-146a, miR-210 and miR-222) expression in newborn girls in association with pre-pregnancy BMI at specific gestational weight gain values.

| Gestational Weight Gain (kg)a | miR-146a | miR-210 | miR-222 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % change (95% CI) | P-value | % change (95% CI) | P-value | % change (95% CI) | P-value | |

| 7 | −9.12 (−15.40, −2.38) | 0.01 | −9.53 (−17.34, −0.98) | 0.032 | −8.31 (−14.07, −2.16) | 0.01 |

| 11 | −6.66 (−11.92, −1.09) | 0.022 | −6.94 (−13.50, 0.12) | 0.057 | −6.34 (−11.14, −1.29) | 0.016 |

| 14 | −4.77 (−9.76, 0.50) | 0.078 | −4.95 (−11.19, 1.72) | 0.14 | −4.84 (−9.38, −0.09) | 0.049 |

| 18 | −2.19 (−7.74, 3.70) | 0.46 | −2.23 (−9.18, 5.24) | 0.55 | −2.81 (−7.82, 2.48) | 0.29 |

| 25 | 2.50 (−5.99, 11.76) | 0.58 | 2.70 (−7.90, 14.53) | 0.63 | 0.86 (−6.74, 9.08) | 0.83 |

Estimates (95% confidence intervals) are given for a 1 kg/m2 increase in BMI and adjusted for newborn’s ethnicity and gestational age, maternal age, smoking status, educational status, parity, gestational weight gain, interaction between pre-pregnancy BMI and gestational weight gain, health complications, delivery by C-section and outdoor temperature during third trimester.

aThe gestational weight gain (kg) is indicated for 5th, 25th, 50th, 75th and 95th percentiles.

Considering maternal BMI at delivery, only the placental relative miR-34a expression was associated with mother’s BMI at delivery (−7.90% for 1 unit BMI increase, [CI: −13.32, −2.15, p = 0.009]).

Finally, sensitivity analyses, from which we excluded mothers with pregnancy complications, or with C-section deliveries were confirmatory (see Supplementary Table S1).

Discussion

Maternal obesity signifies an important public health issue, as it affects the health of the mother and has a large impact on the health of the unborn fetus possibly leading to health risks later in life10, 30–32. The onset of metabolic diseases including obesity in childhood or adulthood has been described to commence in early life33. Perturbations in the intrauterine environment can affect epigenetic mechanisms, which are involved in fetal programming and could be important in development of various diseases throughout life34.

MiRNAs play key regulatory roles in diverse biological processes, including inflammation, oxidative stress, apoptosis, angiogenesis, adipogenesis, which are all implicated in development of metabolic disorders, such as obesity and cardiovascular diseases13, 35, 36.

Our results indicate that higher maternal pre-pregnancy BMI is associated with lower placental miRNA expression for miR-20a, miR-34a, miR-146a, miR-210 and miR-222 expression in girls but not in boys. Further, the effect of pre-pregnancy BMI on some placental miRNA (miR-146a, miR-210 and miR-222) expression was modified by maternal gestational weight gain.

Our study population consisted mostly (64.9%) of women with normal pre-pregnancy BMI (23.9 ± 4.1 kg/m2) and found that for 1 kg/m2 increment in pre-pregnancy BMI corresponds to a decrease in placental miRNA expression within a range of 4.3–8.8%, in girls. These changes for only 1 unit increase in pre-pregnancy BMI were similar to the range of decrease (3.9–9.4%) in miRNA expression, including miR-16, miR-21 and miR-146a, reported for placentas exposed to maternal cigarette smoke during pregnancy37.

Aberrant expression of miR-222 has been reported in obese or morbidly obese men compared to a control group of healthy weight individuals (n = 80). Decreased levels of circulating miR-16 and increased levels of miR-21 and miR-146a were found in morbidly obese patients (n = 22) before versus after surgically-induced weight loss22. Higher placental expression of miR-210 has been shown in obese mothers (pre-pregnancy BMI > 30 kg/m2) versus mothers with a healthy weight (n = 36)38. In addition, overexpression of miR-20a23, miR-2124, miR-34a39, and decreased expression of miR-210 and miR-22239 has been linked to increased adipocyte differentiation.

The observed changes in placental candidate miRNA expression associated with an increase in maternal pre-pregnancy BMI may regulate processes involved in placental inflammation and angiogenesis. Increased levels of placental pro-inflammatory cytokines have been reported in response to maternal obesity40, 41. Maternal obesity has been also linked to placental abruption and abnormal spiral artery remodeling which is likely to be caused by insufficient trophoblast invasion42. MiR-146a has been involved in inflammatory responses by activating NF-kB signaling43. Decreased levels of miR-146a expression in serum were linked to chronic inflammation in diabetic patients26, insulin resistance and pro-inflammatory cytokine genes44. Moreover, Dentelli et al., have reported that down-modulated miR-222 in endothelial cells was involved in inflammation-mediated vascular remodeling45.

Based on numerous studies, many miRNAs also referred to as angiomiRs have been identified to play an important role in (placental) angiogenesis46, 47. Among them, miR-21, miR-20a and miR-210 have been shown to induce angiogenesis, whereas miR-16, miR-34a and miR-222 inhibit angiogenesis (Table 5). In placenta, miR-20a and miR-34a have been identified in spiral artery remodeling, miR-16 in vascular endothelial growth factor signaling pathway and miR-210 in trophoblastic migration and invasion47. In case of an imbalance between pro- and anti-angiogenic factors, an increased or decreased formation of blood vessels can occur48, which may lead to abnormal placental development47. Additionally, oxidative stress has been implicated in placental vascular dysfunction49.

We analyzed the association between placental miRNA expression and maternal pre-pregnancy BMI in a gender-specific approach and found no association with our miRNA candidates and mothers pre-pregnancy BMI in boys. This is in line with a previous smaller study (n = 36)38 that noted only significant alterations in placental miRNA expression in association with mother’s pre-pregnancy BMI for girls. This supports the hypothesis that placental miRNAs in female fetuses are more responsive to maternal BMI changes than those from boys. Several studies have shown that fetal development and growth exhibit gender specificity50–52. Gender differences have been observed when studying placental immune function53, gene54 and protein expression53.

Till now, the exact mechanism underlying this observed sex-specificity on placenta remains unknown. The increased sensitivity of the female placenta observed here, as well as in other studies51, 55–57, might be interpreted as potential protective mechanisms, that might explain the lower risk for adult diseases, such as hypertension and/or cardiovascular diseases, in women compared with men58, 59.

A strong point of our study is the use of measured pre-pregnancy BMI at the first antenatal visit of the mother at the hospital (around week 7–9 of pregnancy) that minimizes the chance of misreported pre-pregnancy BMI. In addition, there is no large population based birth cohort yet which addressed the association between pre-pregnancy BMI and placental miRNA expression. Notwithstanding these strong points, our study should be interpreted within the context of its possible limitations. First, the obesity-related factors can induce epigenetic changes in germ line cells as well, that can be transmittable to the next generation. In this regard, a study showed that paternal obesity modulates sperm miRNA content and germ cell methylation and impairs the metabolic status of the next generation60. We did not have information of the BMI of the father. Second, based only on these findings we cannot assure whether these miRNA alterations persist in later life. Finally, we adjusted our statistical model for a range of possible covariates, but this does not rule out the possibility of under- or over-estimation by other important variables not yet identified which may be associated with both maternal pre-pregnancy BMI and placental miRNA expression.

Conclusion

We observed an inverse association between maternal pre-pregnancy BMI and placental miRNA expression in a sex-specific pattern, with effects of placental miR-20a, miR-34a, miR-146a, miR-210 and miR-222 only in newborn girls. These miRNAs may be implicated in the development of metabolic diseases in postnatal or later life. Therefore, we believe maintaining a healthy BMI before pregnancy is an important factor to contribute to normal placental function and can prevent detrimental health outcomes later in life. Further studies are needed to investigate long-term effects of these molecular changes.

Methods

Study population

This study included 215 mother-newborn pairs (with only singletons) selected from the ongoing ENVIRONAGE (ENVIRonmental influence ON AGEing in early life) birth cohort in the province Limburg in Belgium61. The study protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee of Hasselt University and South-East-Limburg Hospital (ZOL) in Genk (Belgium) and has been carried out according to the declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all participating mothers. The recruitment of mother-newborn pairs took place from March 2010 till January 2014, between Friday 12.00 hours and Monday 07.00 hours. Inclusion criteria included the mother’s ability to fill out questionnaires in Dutch. The overall participation rate was 61%. Detailed information on maternal age, education, occupation, smoking status, alcohol consumption, place of residence, use of medication, parity and newborn’s ethnicity were provided by the participants. Smoking status of the mothers was categorized into three groups: non-smokers (those who never smoked), past-smokers (those who quit smoking before pregnancy) and current-smokers (those who continued smoking during pregnancy). Ethnicity of the newborn was classified based on the native country of the newborn’s grandparents: European-Caucasian (those with more than two European grandparents) and non-European (those with at least three non-European grandparents). Maternal educational status was grouped as low (no diploma or primary school), middle (high school) or high (college or university degree).

The maternal health complications including pre-eclampsia, gestational diabetes, hypertension, hypo- or hyperthyroidism, asthma, gastric band surgery prior to pregnancy, were retrieved from the medical records.

Data on mean daily outdoor temperature for the study region were provided by the Royal Meteorological Institute (Brussels, Belgium).

Maternal pre-pregnancy BMI, gestational weight gain and BMI at delivery

The maternal pre-pregnancy BMI was recorded in the hospital at the first antenatal visit around week 7–9 of pregnancy. Maternal height and weight were measured to the nearest centimeter and to the nearest 0.1 kg respectively, without wearing shoes and wearing light clothes. Maternal pre-pregnancy BMI is calculated as the pre-pregnancy body weight (kg) divided by the square of the height (m2). According to the World Health Organization (WHO) classification62, BMI in adults is categorized into the following groups: underweight (<18.5 kg/m2), normal weight (18.5–24.9 kg/m2), overweight (25.0–29.9 kg/m2) and obese (≥30 kg/m2). Women with a pre-pregnancy BMI > 40 kg/m2 (class III obesity) were excluded from further analyses, resulting in a final study population of 211 mother-newborn pairs.

The gestational weight gain (kg) is defined as the weight at delivery minus the pre-pregnancy weight. Mothers were weighed on admission to the delivery ward to obtain their weight at delivery. Using the recommended gestational weight gain guidelines by the IOM29, based on the maternal pre-pregnancy BMI according to WHO62, the gestational weight gain is expected to be within the range of 12.7–18.1 kg for underweight, 11.3–15.9 kg for normal weight, 6.8–11.3 kg for overweight and 5.0–9.1 kg for obese women. The BMI (kg/m2) at delivery is calculated by the weight (kg) at delivery divided by the square of the height (m2).

Selection candidate miRNAs

In this study, we investigated the effect of maternal pre-pregnancy BMI on placental candidate miRNA expression, using the fetal portion of placental tissue. We selected a set of seven miRNAs, miR-16, miR-20a, miR-21, miR-34a, miR-146a, miR-210 and miR-222, which are expressed in human placental tissue and are involved in key cellular processes (Table 1 and Table 5) implicated in obesity15, 17, 18. MiR-16 has been implicated in regulation of the cell cycle and apoptosis, miR-20a in cell proliferation, invasion and angiogenesis, miR-21 in cell cycle and proliferation, miR-34a in cell growth and invasion, miR-146a in inflammation, miR-210 in angiogenesis and oxidative stress, and miR-222 in angiogenesis. Furthermore, the selected miRNAs for study are known to be responsive to various in utero exposures which possibly affect fetal programming and subsequently can lead to adverse health outcomes in later life37, 63–65.

Sample Collection

After delivery, placental tissue was collected and deep-frozen within 10 minutes. On the fetal side of the placenta, four standardized biopsies were collected and stored in RNA later at 4 °C overnight and then at −20 °C for longer period. These biopsies were taken at fixed locations across the middle point of the placenta, at approximately 4 cm distance from the umbilical cord.

RNA isolation and DNase treatment

Total RNA and miRNA were extracted from pooled placenta biopsies using the miRNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, KJ Venlo, the Netherlands) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. We used pooled placenta samples from 4 collected biopsies, in order to minimize possible intra-placental variation. Quantity and purity of the extracted total RNA and miRNA was assessed by spectrophotometry (Nanodrop ND-1000; Isogen Life Science, De Meern, the Netherlands). The average (±SD) yield of total RNA per placenta pooled biopsies was 4.4 (±1.2) µg with average A260/280 and A260/230 ratios of 1.95 (±0.04) and 1.71 (±0.16), respectively. DNase treatment was performed on extracted RNA samples according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Turbo DNA-free kit, Ambion, Life Technologies, Diegem, Belgium). Isolated RNA was stored at −80 °C until further applications.

Reverse transcription and miRNA expression analysis

Briefly, using the TaqMan miRNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and Megaplex stem-loop primer pool A (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), RNA was reverse transcribed allowing miRNA specific cDNA synthesis, which we performed for the 7 selected miRNAs, according to the manufacturer’s protocol. All target sequences of the miRNAs and control RNA are available in Supplementary Table S2. RNA was reverse transcribed and produced cDNA was stored at −20 °C for a maximum of one week until further downstream measurements. For the measurement of miRNA expression, cDNA was used for PCR reactions on a 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), using Taqman miRNA assays (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), all according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Detailed methods have been described previously65. For normalization the endogenous control RNU6 was used. In order to minimize the technical variation between the different runs of the same miRNA assay, inter-run calibrators (IRCs) were applied. Amplification efficiencies were between 90–115% for all assays. The obtained Cq values were extracted by SDS 2.3 software (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and then the relative miRNA expression was calculated by 2−ΔΔCq method using qBase plus software (Biogazelle, Belgium). All samples were analyzed in triplicate. Replicates were included when ΔCq was smaller than 0.5.

Statistical analysis

The relative quantities of miRNA expressions were log-transformed (log10) because of their non-normal distribution. Maternal pre-pregnancy BMI, gestational weight gain and BMI at delivery were included as continuous variables. SAS software (Version 9.4 SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) was used for the statistical analysis.

The associations between log10-transformed relative placental miRNA expression and maternal pre-pregnancy BMI, gestational weight gain and BMI at delivery were assessed using multiple linear regression models, stratifying by gender (n = 112 girls, n = 99 boys). Models were adjusted for the following a priori chosen covariates: newborn’s ethnicity (European or non-European) and gestational age (weeks), maternal age (years), smoking status (never-smoker, past-smoker or current-smoker), educational status (low, middle or high), parity (1, 2 or ≥3), health complications (pre-eclampsia, gestational diabetes, hypertension, hypo/hyperthyroidism, asthma and gastric band surgery prior to pregnancy), delivery by C-section and outdoor temperature during the third trimester of pregnancy (categorized into quartiles). Maternal health complications were treated as dichotomous variables. Models with pre-pregnancy BMI as independent variable were additionally adjusted for gestational weight gain.

We started by testing the interaction between pre-pregnancy BMI and gestational weight gain for each measured miRNA. The interaction term was kept in the final model when the p-value was <0.1, and the estimated effect of pre-pregnancy BMI (or gestational weight gain) was reported for the median value of gestational weight gain (or pre-pregnancy BMI).

We calculated the change (%) in placental miRNA expression per 1 unit increase in the independent variable of interest (1 kg/m2 for pre-pregnancy BMI and BMI at delivery; 1 kg for gestational weight gain) as follows:

with 95% confidence intervals (CI), where β is the estimated regression coefficient.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

The ENVIRONAGE birth cohort is supported by grants from the European Research Council (ERC-2012-StG 310898) and Flemish Research Council (FWO G073315N). Karen Vrijens is a postdoctoral fellow of the FWO (12D7714N).

Author Contributions

M.T. performed the miRNA expression experiments, D.S.M. collected data on maternal pre-pregnancy BMI and gestational weight gain, N.M. and W.G. recruited the study population, M.T., D.S.M. and N.M. collected molecular samples for analyses. M.T.,E.W., B.C., T.S.N. and K.V. analyzed and interpreted the data. M.T., T.S.N. and K.V. wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Tim S. Nawrot and Karen Vrijens contributed equally to this work.

A correction to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-24090-y.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at doi:10.1038/s41598-017-04026-8

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Barker DJ. Fetal origins of coronary heart disease. BMJ: British Medical Journal. 1995;311:171–174. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.6998.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leddy MA, Power ML, Schulkin J. The Impact of Maternal Obesity on Maternal and Fetal Health. Rev. Obstet. Gynecol. 2008;1:170–178. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Valsamakis GKE, Mouslech Z, Siristatidis C, Mastorakos G. Effect of maternal obesity on pregnancy outcomes and long-term metabolic consequences. Hormones (Athens) 2015;14:345–357. doi: 10.14310/horm.2002.1590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lawlor DA. The Society for Social Medicine John Pemberton Lecture 2011. Developmental overnutrition—an old hypothesis with new importance? Int. J. Epidemiol. 2013;42:7–29. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wen X, Triche EW, Hogan JW, Shenassa ED, Buka SL. Prenatal Factors for Childhood Blood Pressure Mediated by Intrauterine and/or Childhood Growth? Pediatrics. 2011;127:e713–e721. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ganu RS, Harris RA, Collins K, Aagaard KM. Early Origins of Adult Disease: Approaches for Investigating the Programmable Epigenome in Humans, Nonhuman Primates, and Rodents. ILAR Journal. 2012;53:306–321. doi: 10.1093/ilar.53.3-4.306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hochner H, et al. Associations of Maternal Pre-Pregnancy Body Mass Index and Gestational Weight Gain with Adult Offspring Cardio-Metabolic Risk Factors: The Jerusalem Perinatal Family Follow-up Study. Circulation. 2012;125:1381–1389. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.070060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Malti N, et al. Oxidative stress and maternal obesity: Feto-placental unit interaction. Placenta. 2014;35:411–416. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2014.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gallardo JM, et al. Maternal obesity increases oxidative stress in the newborn. Obesity. 2015;23:1650–1654. doi: 10.1002/oby.21159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leibowitz K, et al. Maternal obesity associated with inflammation in their children. World J. Pediatr. 2012;8:76–79. doi: 10.1007/s12519-011-0292-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kappil M, Chen J. Environmental exposures in utero and microRNA. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2014;26:243–251. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0000000000000073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Filipowicz, W., Bhattacharyya, S. N. & Sonenberg, N. Mechanisms of post-transcriptional regulation by microRNAs: are the answers in sight? Nat Rev Genet9, 102–114, doi:http://www.nature.com/nrg/journal/v9/n2/suppinfo/nrg2290_S1.html (2008). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Heneghan HM, Miller N, Kerin MJ. Role of microRNAs in obesity and the metabolic syndrome. Obes. Rev. 2010;11:354–361. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2009.00659.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao Z, Moley KH, Gronowski AM. Diagnostic potential for miRNAs as biomarkers for pregnancy-specific diseases. Clin. Biochem. 2013;46:953–960. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2013.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McGregor RA, Choi M. S. microRNAs in the Regulation of Adipogenesis and Obesity. Curr. Mol. Med. 2011;11:304–316. doi: 10.2174/156652411795677990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peng Y, et al. MicroRNAs: Emerging roles in adipogenesis and obesity. Cell. Signal. 2014;26:1888–1896. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2014.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lumeng CN, Saltiel AR. Inflammatory links between obesity and metabolic disease. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2011;121:2111–2117. doi: 10.1172/JCI57132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fernández-Sánchez A, et al. Inflammation, Oxidative Stress, and Obesity. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2011;12:3117–3132. doi: 10.3390/ijms12053117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Herold C, Rennekampff HO, Engeli S. Apoptotic pathways in adipose tissue. Apoptosis. 2013;18:911–916. doi: 10.1007/s10495-013-0848-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakatsuka AWJ, Makino H. Cell cycle abnormality in metabolic syndrome and nuclear receptors as an emerging therapeutic target. Acta Med. Okayama. 2013;67:129–134. doi: 10.18926/AMO/50405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lemoine AY, Ledoux S, Larger E. Adipose tissue angiogenesis in obesity. Thromb. Haemost. 2013;110:661–669. doi: 10.1160/TH13-01-0073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ortega FJ, et al. Targeting the Circulating MicroRNA Signature of Obesity. Clin. Chem. 2013;59:781–792. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2012.195776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang Q, et al. miR-17-92 cluster accelerates adipocyte differentiation by negatively regulating tumor-suppressor Rb2/p130. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:2889–2894. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800178105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim YJ, Hwang SJ, Bae YC, Jung JS. MiR-21 Regulates Adipogenic Differentiation through the Modulation of TGF-β Signaling in Mesenchymal Stem Cells Derived from Human Adipose Tissue. Stem Cells. 2009;27:3093–3102. doi: 10.1002/stem.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fu T, et al. MicroRNA 34a Inhibits Beige and Brown Fat Formation in Obesity in Part by Suppressing Adipocyte Fibroblast Growth Factor 21 Signaling and SIRT1 Function. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2014;34:4130–4142. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00596-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baldeón RL, et al. Decreased Serum Level of miR-146a as Sign of Chronic Inflammation in Type 2 Diabetic Patients. PLoS One. 2014;9:e115209. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0115209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Qin L, et al. A deep investigation into the adipogenesis mechanism: Profile of microRNAs regulating adipogenesis by modulating the canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. BMC Genomics. 2010;11:1–10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xie H, Lim B, Lodish HF. MicroRNAs Induced During Adipogenesis that Accelerate Fat Cell Development Are Downregulated in Obesity. Diabetes. 2009;58:1050–1057. doi: 10.2337/db08-1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Institute of Medicine, I. Weight gain during pregnancy: reexamining the guidelines. (Washington, 2009).

- 30.Guelinckx I, Devlieger R, Beckers K, Vansant G. Maternal obesity: pregnancy complications, gestational weight gain and nutrition. Obes. Rev. 2008;9:140–150. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2007.00464.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ramsay JE, et al. Maternal Obesity Is Associated with Dysregulation of Metabolic, Vascular, and Inflammatory Pathways. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2002;87:4231–4237. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-020311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kulie T, et al. Obesity and Women’s Health: An Evidence-Based Review. The Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine. 2011;24:75–85. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2011.01.100076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lawrence GM, et al. Associations of Maternal Pre-pregnancy Body Mass Index and Gestational Weight Gain with Offspring Longitudinal Change in BMI. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.) 2014;22:1165–1171. doi: 10.1002/oby.20643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yajnik CS. Transmission of Obesity-Adiposity and Related Disorders from the Mother to the Baby. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2014;64(suppl 1):8–17. doi: 10.1159/000362608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nishiguchi T, Imanishi T, Akasaka T. MicroRNAs and Cardiovascular Diseases. BioMed Research International. 2015;2015:14. doi: 10.1155/2015/682857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hulsmans M, De Keyzer D, Holvoet P. MicroRNAs regulating oxidative stress and inflammation in relation to obesity and atherosclerosis. The FASEB Journal. 2011;25:2515–2527. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-181149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maccani MA, et al. Maternal cigarette smoking during pregnancy is associated with downregulation of miR-16, miR-21, and miR-146a in the placenta. Epigenetics. 2010;5:583–589. doi: 10.4161/epi.5.7.12762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Muralimanoharan, S., Guo, C., Myatt, L. & Maloyan, A. Sexual dimorphism in miR-210 expression and mitochondrial dysfunction in the placenta with maternal obesity. Int. J. Obes., doi:10.1038/ijo.2015.45 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Ortega FJ, et al. MiRNA Expression Profile of Human Subcutaneous Adipose and during Adipocyte Differentiation. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9022. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roberts KA, et al. Placental structure and inflammation in pregnancies associated with obesity. Placenta. 2011;32:247–254. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2010.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Challier JC, et al. Obesity in pregnancy stimulates macrophage accumulation and inflammation in the placenta. Placenta. 2008;29:274–281. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2007.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pereira RD, et al. Angiogenesis in the Placenta: The Role of Reactive Oxygen Species Signaling. BioMed Research International. 2015;2015:12. doi: 10.1155/2015/814543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Taganov KD, Boldin MP, Chang K-J, Baltimore D. NF-κB-dependent induction of microRNA miR-146, an inhibitor targeted to signaling proteins of innate immune responses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:12481–12486. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605298103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Balasubramanyam M, et al. Impaired miR-146a expression links subclinical inflammation and insulin resistance in Type 2 diabetes. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2011;351:197–205. doi: 10.1007/s11010-011-0727-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dentelli P, et al. microRNA-222 Controls Neovascularization by Regulating Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 5A Expression. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2010;30:1562–1568. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.206201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang S, Olson EN. AngiomiRs—Key Regulators of Angiogenesis. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2009;19:205–211. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rodríguez Santa Laura María, G. T. L. Y., Forero Forero Jose Vicente, and Castillo Giraldo Andres Orlando AngiomiRs: Potential Biomarkers of Pregnancy’s Vascular Pathologies. Journal of Pregnancy2015, 10, doi:10.1155/2015/320386 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Yin K-J, Hamblin M, Chen YE. Angiogenesis-regulating microRNAs and ischemic stroke. Curr. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2015;13:352–365. doi: 10.2174/15701611113119990016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Myatt L, Kossenjans W, Sahay R, Eis A, Brockman D. Oxidative stress causes vascular dysfunction in the placenta. J. Matern. Fetal Med. 2000;9:79–82. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6661(200001/02)9:1<79::AID-MFM16>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Challis, J., Newnham, J., Petraglia, F., Yeganegi, M. & Bocking, A. Fetal sex and preterm birth. Placenta34, 95–99, doi:10.1016/j.placenta.2012.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51.Murphy VE, et al. Maternal Asthma Is Associated with Reduced Female Fetal Growth. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2003;168:1317–1323. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200303-374OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Clifton, V. L. Review: Sex and the Human Placenta: Mediating Differential Strategies of Fetal Growth and Survival. Placenta31, S33–S39, doi:10.1016/j.placenta.2009.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 53.Scott NM, et al. Placental Cytokine Expression Covaries with Maternal Asthma Severity and Fetal Sex. The Journal of Immunology. 2009;182:1411–1420. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.3.1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sood R, Zehnder JL, Druzin ML, Brown PO. Gene expression patterns in human placenta. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2006;103:5478–5483. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508035103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Corcoran MP, et al. Sex hormone modulation of proinflammatory cytokine and CRP expression in macrophages from older men and postmenopausal women. The Journal of endocrinology. 2010;206:217–224. doi: 10.1677/JOE-10-0057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mao J, et al. Contrasting effects of different maternal diets on sexually dimorphic gene expression in the murine placenta. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:5557–5562. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000440107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tarrade A, et al. Sexual Dimorphism of the Feto-Placental Phenotype in Response to a High Fat and Control Maternal Diets in a Rabbit Model. PLoS One. 2013;8:e83458. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Grigore D, Ojeda NB, Alexander BT. Sex differences in the fetal programming of cardiovascular disease. Gend. Med. 2008;5:S121–S132. doi: 10.1016/j.genm.2008.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Woods LL, Ingelfinger JR, Rasch R. Modest maternal protein restriction fails to program adult hypertension in female rats. American Journal of Physiology - Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology. 2005;289:R1131–R1136. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00037.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fullston, T. et al. Paternal obesity initiates metabolic disturbances in two generations of mice with incomplete penetrance to the F2 generation and alters the transcriptional profile of testis and sperm microRNA content. The FASEB Journal, doi:10.1096/fj.12-224048 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 61.Bram G. Janssen, N. M., Wilfried Gyselaers, Esmée Bijnens, Diana B. Clemente, Bianca Cox, Janneke Hogervorst, Leen Luyten, Dries S. Martens, Martien Peusens, Michelle Plusquin, Eline B. Provost, Harry A. Roels, Nelly D. Saenen, Maria Tsamou, Annette Vriens, Ellen Winckelmans, Karen Vrijens, Tim S. Nawrot. Cohort Profile: The ENVIRonmental influence ON early AGEing (ENVIRONAGE): a birth cohort study. Int. J. Epidemiol., doi:10.1093/ije/dyw269 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 62.WHO, W. H. O. Obesity and overweight. Global strategy on diet, physical activity and health., http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/publications/facts/obesity/en/ (2015).

- 63.Umemura K, et al. Roles of microRNA-34a in the pathogenesis of placenta accreta. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2013;39:67–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2012.01898.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vrijens, K., Bollati, V. & Nawrot, T. S. MicroRNAs as Potential Signatures of Environmental Exposure or Effect: A Systematic Review. Environ Health Perspect, doi:10.1289/ehp.1408459 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 65.Tsamou, M. et al. Air pollution-induced placental epigenetic alterations in early life: a candidate miRNA approach. Epigenetics, 00–00, doi:10.1080/15592294.2016.1155012 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 66.Maccani MA, Padbury JF, Lester BM, Knopik VS, Marsit CJ. Placental miRNA expression profiles are associated with measures of infant neurobehavioral outcomes. Pediatr. Res. 2013;74:272–278. doi: 10.1038/pr.2013.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hu Y, et al. Differential expression of microRNAs in the placentae of Chinese patients with severe pre-eclampsia. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2009;47:923. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2009.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wang W, et al. Preeclampsia Up-Regulates Angiogenesis-Associated MicroRNA (i.e., miR-17, −20a, and −20b) That Target Ephrin-B2 and EPHB4 in Human Placenta. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2012;97:E1051–E1059. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-3131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wang Y, et al. Aberrantly Up-regulated miR-20a in Pre-eclampsic Placenta Compromised the Proliferative and Invasive Behaviors of Trophoblast Cells by Targeting Forkhead Box Protein A1. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2014;10:973–982. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.9088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Maccani MA, Padbury JF, Marsit CJ. miR-16 and miR-21 Expression in the Placenta Is Associated with Fetal Growth. PLoS One. 2011;6:e21210. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pang, R. T. et al. MicroRNA-34a suppresses invasion through downregulation of Notch1 and Jagged1 in cervical carcinoma and choriocarcinoma cells. Carcinogenesis31, doi:10.1093/carcin/bgq066 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 72.Avissar-Whiting M, et al. Bisphenol A Exposure Leads to Specific MicroRNA Alterations in Placental Cells. Reproductive toxicology (Elmsford, N.Y.) 2010;29:401–406. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Muralimanoharan S, et al. Mir-210 modulates mitochondrial respiration in placenta with preeclampsia. Placenta. 2012;33:816–823. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2012.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhao C, et al. Early Second-Trimester Serum MiRNA Profiling Predicts Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. PLoS One. 2011;6:e23925. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wang Y, et al. miR-16 inhibits the proliferation and angiogenesis-regulating potential of mesenchymal stem cells in severe pre-eclampsia. FEBS Journal. 2012;279:4510–4524. doi: 10.1111/febs.12037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Doebele C, et al. Members of the microRNA-17-92 cluster exhibit a cell-intrinsic antiangiogenic function in endothelial cells. Blood. 2010;115:4944–4950. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-01-264812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sabatel C, et al. MicroRNA-21 Exhibits Antiangiogenic Function by Targeting RhoB Expression in Endothelial Cells. PLoS One. 2011;6:e16979. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zhao T, Li J, Chen AF. MicroRNA-34a induces endothelial progenitor cell senescence and impedes its angiogenesis via suppressing silent information regulator 1. American Journal of Physiology - Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2010;299:E110–E116. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00192.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rau C-S, et al. Lipopolysaccharide-Induced microRNA-146a Targets CARD10 and Regulates Angiogenesis in Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells. Toxicol. Sci. 2014;140:315–326. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfu097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Fasanaro P, et al. MicroRNA-210 Modulates Endothelial Cell Response to Hypoxia and Inhibits the Receptor Tyrosine Kinase Ligand Ephrin-A3. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:15878–15883. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800731200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Poliseno L, et al. MicroRNAs modulate the angiogenic properties of HUVECs. Blood. 2006;108:3068–3071. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-01-012369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Urbich C, Kuehbacher A, Dimmeler S. Role of microRNAs in vascular diseases, inflammation, and angiogenesis. Cardiovasc. Res. 2008;79:581–588. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zhu N, et al. Endothelial enriched microRNAs regulate angiotensin II-induced endothelial inflammation and migration. Atherosclerosis. 2011;215:286–293. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Prats-Puig A, et al. Changes in Circulating MicroRNAs Are Associated With Childhood Obesity. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2013;98:E1655–E1660. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Maccani Matthew A., Padbury James F., Marsit Carmen J., Lustig Arthur J. miR-16 and miR-21 Expression in the Placenta Is Associated with Fetal Growth. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(6):e21210. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Doridot L, et al. miR-34a expression, epigenetic regulation, and function in human placental diseases. Epigenetics. 2014;9(1):142–151. doi: 10.4161/epi.26196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.