Abstract

The fungus-growing ant-microbe symbiosis is an ideal system to study chemistry-based microbial interactions due to the wealth of microbial interactions described, and the lack of information on the molecules involved therein. In this study, we employed a combination of MALDI imaging mass spectrometry (MALDI-IMS) and MS/MS molecular networking to study chemistry-based microbial interactions in this system. MALDI IMS was used to visualize the distribution of antimicrobials at the inhibition zone between bacteria associated to the ant Acromyrmex echinatior and the fungal pathogen Escovopsis sp. MS/MS molecular networking was used for the dereplication of compounds found at the inhibition zones. We identified the antibiotics actinomycins D, X2 and X0β, produced by the bacterium Streptomyces CBR38; and the macrolides elaiophylin, efomycin A and efomycin G, produced by the bacterium Streptomyces CBR53.These metabolites were found at the inhibition zones using MALDI IMS and were identified using MS/MS molecular networking. Additionally, three shearinines D, F, and J produced by the fungal pathogen Escovopsis TZ49 were detected. This is the first report of elaiophylins, actinomycin X0β and shearinines in the fungus-growing ant symbiotic system. These results suggest a secondary prophylactic use of these antibiotics by A. echinatior because of their permanent production by the bacteria.

Introduction

Symbioses are associations between different organisms which involve a high degree of dependence and coexistence and are broadly distributed in nature1. Such associations can be found in any ecosystem including most habitat types on earth, and the effects that one or more members of a symbiotic relationship have on each other can affect the system as a whole2–5. Living in symbiosis is an evolutionary strategy enabling organisms to interact. However, there are few examples that explain the maintenance, mechanisms, and survivorship of symbiosis that involve more than two symbionts6–8. To improve our understanding of the mechanisms that regulate the communication and interactions among organisms living in symbiosis, studies need to focus on exploring the nature and diversity of the chemical compounds produced by the organisms interacting in a symbiotic system3, 9–12.

The most complex case of symbiosis may be where an obligatory mutualism occurs in which each symbiotic partner is influenced by their co-evolutionary relationship13. The fungus-growing ants are part of a complex symbiosis between the ants and their microbes, where the attines maintain an obligatory mutualism with a basidiomycete fungus (cultivars) in the tribe Leucocoprineae, which is grown as a unique food source for the brood14–16. At least three other microbes have evolved in this system including: 1) antibiotic-producing bacteria in the order Actinomycetales, which are producers of compounds that inhibit the growth of fungal ant pathogens17; 2) a specialized micro-parasite of the cultivar in the genus Escovopsis 18; and 3) the least studied symbionts are black yeasts, that are antagonists of the antibiotic-producing bacteria19, 20.

Uncontrolled infections of the cultivar by pathogen Escovopsis sp. can cause the death of an entire ant colony. Therefore ants employ a diversity of strategies for maintaining a healthy colony including hygienic behavior, social immunity, waste management, and the use of antimicrobial compounds21, 22. The fungus-growing ant symbiotic system has a diversity of small molecules that potentially mediate interactions among the microbial members of this symbiosis23–27, and may additionally be a rich source of compounds for drug discovery programs23.

Interactions among antibiotic-producing bacteria (genus Pseudonocardia and Streptomyces) and the mutualistic basidiomycete and Escovopsis have been the subject of several studies. Such studies have shown that some ant-associated bacteria are able to produce compounds that inhibit the growth of Escovopsis and other entomopathogens, with and without affecting the cultivar28–31. Despite the fact that many of these antagonistic interactions have been described for the fungus growing ant system, in most cases the chemicals responsible for the inhibitory effects remains unknown. Previous work on the natural product chemistry of the bacteria associated with attine ants show that some bacterial metabolites are involved in the inhibition of Escovopsis. The few natural products that have been elucidated so far for the system include: dentigerumycin24; five angucycline antibiotics (pseudonocardones A–C, 6-deoxy-8-O-methylrabelomycin and X-14881 E)23, the antifungals (candicidin D, actinomycins D and X, valinomycin, antimycin A1-A4 and a several nystatin-like metabolites)26, 32–34; two antimycin antibiotics (urauchimycins A and B)23, 35 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Metabolites described for antibiotic producing bacteria associated to the fungus-growing ants.

| Fungus growing ants species | Bacteria | Bacterial activity | Compounds isolated | Compounds activity | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apterostigma dentigerum | Pseudonocardia spp. | Escovopsis sp. | dentigerumycin | Escovopsis sp. | 24 |

| Pseudonocardia sp. | Not reported | selvamicin | Candida albicans, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Aspergillus fumigatus, and Trichoderma harzianum | 33 | |

| Pseudonocardia sp. EC080529-01 | Not reported | 6-deoxy-8-O-methylrabelomycin | Bacillus subtilis 3610 and Plasmodium berghei | 23 | |

| X-14881 E (8-O-methyltetrangulol) | |||||

| pseudonocardones A | Inactive for test organism | ||||

| pseudonocardones B | |||||

| pseudonocardones C | |||||

| A. octospinosus | Pseudonocardia sp. | Candida albicans and E. weberi | nystatin P1 | Not tested | 26 |

| Streptomyces sp. | E. weberi | candicidin D | E. weberi | 26, 27, 32, 34 | |

| Streptomyces sp. Streptomyces sp. Av25_2 | Not reported | actinomycin D | B. subtilis | ||

| Acromyrmex sp. | Streptomyces sp. Av25_2 | Not reported | actinomycin X2 | B. subtilis | 34 |

| Streptomyces sp. Av25_3 | Not reported | valinomycin | B. subtilis | ||

| Streptomyces sp. Ao10 | E. weberi | antimycin A1 | E. weberi | ||

| antimycin A2 | |||||

| antimycin A3 | |||||

| antimycin A3 | |||||

| Trachymyrmex sp. | Streptomyces sp. TD025. | Five Candida species | urauchimycin A | Four Candida species | 35 |

| urauchimycin B | Six Candida species |

The table summarizes compounds that are produced by the bacteria associated with fungus growing ant’s species pointing out the activity against the fungal pathogen, Escovopsis.

The lack of information available on the chemical nature of the interactions between members of the attine ant-microbes system provides an opportunity to explore the production of interaction-mediator compounds, their metabolic pathways and their ecological role in the symbiosis. The use of techniques such as MALDI imaging mass spectrometry, MS-based molecular networking36–40, and metagenomics approaches41 can provide new insights into how microbial communities associated with attine ants interact at the molecular level.

Herein we used MALDI-IMS36, 37, 40 and MS/MS-based molecular networking38, 39, 41 to study antagonistic interactions between actinobacteria in the genus Streptomyces, isolated from the ant Acromyrmex echinatior, against strains of Escovopsis isolated from the fungal garden of A. echinatior and Trachymyrmex zeteki nests. Using these techniques we found a series of antimicrobial metabolites produced by Streptomyces CBR53 and Streptomyces CBR38. The conditions under they were produced, and their antimicrobial properties in the fungus-growing ants symbiotic system were assessed.

Results

DNA sequence identification

Bacterial strains CBR53 and CBR38 isolated from the propleura of A. echinatior were both identified as Streptomyces sp. based on the analysis of their partial 16S rRNA gene sequences. 16S rRNA gene sequences were deposited in Gene Bank with accession numbers KM096868 and KM096867 for CBR53 and CBR38, respectively. Fungal pathogen strains ACRO424 and TZ49 were identified as Escovopsis sp. based on the partial sequence of the internal transcribed spacers (ITS), sequences were deposited in Gene Bank under the accession numbers KM096865 and KM096866.

Identification of metabolites using MALDI IMS and molecular networking of Streptomyces CBR53 and Escovopsis TZ49 extracts

Streptomyces CBR53 showed an inhibition zone diameter of 3.47 ± 0.51 mm against Escovopsis TZ49. Streptomyces CBR53 metabolites not only affected the side that was head-on with Escovopsis, they additionally exert a negative effect on the opposite side of the radial growth of Escovopsis, reducing from normal grow of 17.19 ± 2.67 mm to 4.33 ± 0.14 mm in the presence of the bacteria.

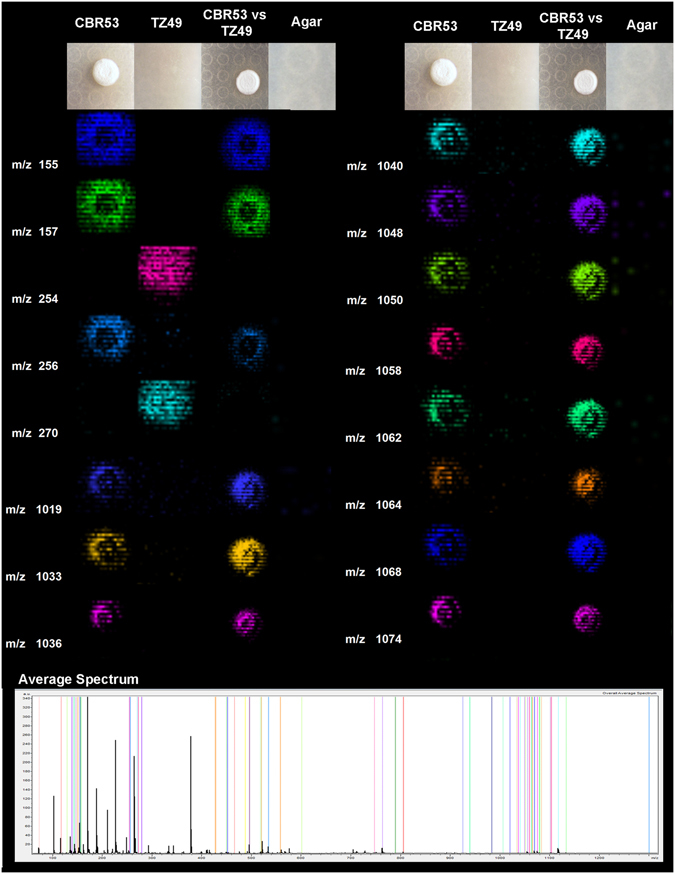

Using MALDI IMS we evaluated the pairwise interaction between Streptomyces sp. CBR53 and Escovopsis sp. TZ49, the results captured the distribution of several ions (metabolites) produced by the bacteria (m/z 519, 534, 924, 1033, 1048, 1062 and 1064, among others) and few from the fungi (m/z 254 and 270) (Fig. 1, Supplementary Figs S1 and S2). A detailed examination of the region between m/z 534 to m/z 1080 of the MALDI IMS experiments, showed that some compounds have similar spatial distribution around the Streptomyces sp. CBR53 growth in both inoculum procedures: single Streptomyces sp. CBR53 (Fig. 1: CBR53) and Streptomyces sp. vs Escovopsis sp. (Fig. 1: CBR53vsTZ49); indicating a lack of influence of the fungi towards the bacteria regarding the production of these metabolites. Furthermore, Escovopsis sp. TZ49 metabolites, ions at m/z 254 and 270 (Fig. 1: TZ49), are completely absent in the pairwise match (Fig. 1: CBR53vsTZ49; Supplementary Figs S1 and S2) likely because the presence of the bacterial metabolites.

Figure 1.

MALDI-TOF imaging mass spectrometry of microbial interactions between Streptomyces CBR53 and pathogenic fungi Escovopsis TZ49. Representative ions observed for the microbial interaction are presented as columns, first column show mass to charge ratio, second to fifth columns display false-colored images of the spatial distribution of the ions observed around: Streptomyces sp. (CBR53); Escovopsis sp. (TZ49); Streptomyces sp. vs Escovopsis sp. (CBR53vsTZ49); and SFM Agar. Average mass spectrum highlighting all the selected ions is shown at the bottom.

The chemical profile of the methanol extract of Streptomyces sp. CBR53 analyzed by high resolution ESI-TOFMS showed some ions at m/z 1033.5589, 1047.5779, 1061.5799, 1079.6032 that match with the ions visualized in the MALDI IMS experiment (Supplementary Figure S2).

MS-guided fractionation of the methanol extract of Streptomyces sp. CBR53 was carried out using a reverse phase solid phase extraction cartridge (SPE-C18) followed by HPLC purification yielding compound 1. Compound 1 (m/z 1047.5779 [M + Na]+) was identified as elaiophylin (Fig. 2C) on the basis of the comparison of its spectral data (Supplementary Figs S3, S4, S5 and Table S1) with spectroscopic data from the literature42–47.

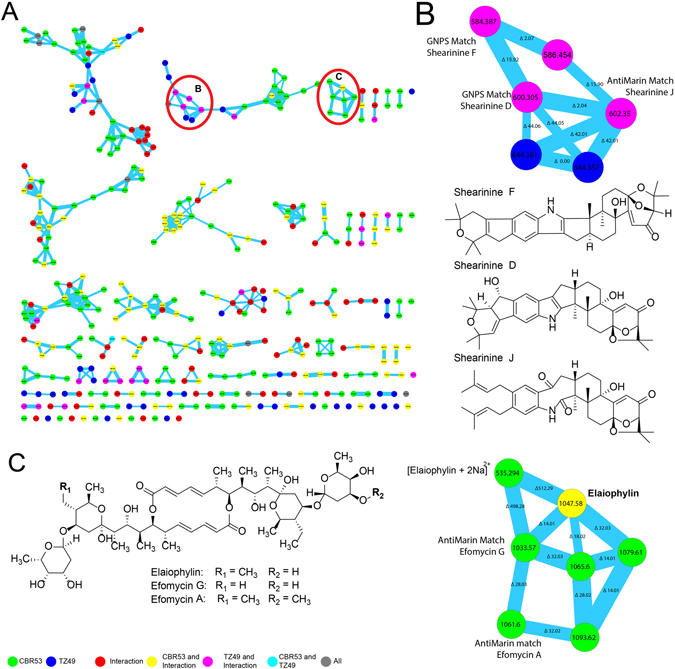

Figure 2.

Molecular network from the extract of the bacterium Streptomyces CBR53 with the identification of the elaiophylin macrolide. (A) Molecular network after filter blanks, colors indicate producers of the nodes: Streptomyces CBR53 green; Escvopsis TZ49 blue, Streptomyces sp. vs Escovopsis sp. (CBR53 vs TZ49) red. Nodes found in more than one producers are represented as combination of their colors: Streptomyces CBR53, Streptomyces sp. vs Escovopsis sp. (CBR53 vs TZ49) yellow; Escovopsis TZ49, Streptomyces sp. vs Escovopsis sp (CBR53 vs TZ49) pink; Streptomyces CBR53, Escvopsis TZ49 cian. (B) Enlarged cluster of shearinine derivatives indicating their location in the sub-network, chemical structures of shearinine D, shearinine F and shearinine J. (C) Chemical structures of elaiophylin, efomycin G and efomycin A macrolides dereplicated using GNPS and AntiMarin, enlarged cluster denoting their location in the cluster.

To characterize additional compounds we employed the HPLC ESI-Q-TOF-HRMS data of the methanol extract of: Streptomyces sp. CBR53, Streptomyces sp. vs Escovopsis sp. (CBR53vsTZ49) and Escvopsis sp. TZ49, to create a molecular network using the online workflow at GNPS (http://gnps.ucsd.edu/ProteoSAFe/status.jsp?task=013afe575fb7438a96c9ab60da167f98). As a result, a molecular network (Fig. 2A) consisting of three hundred seventy seven (377) nodes, clustered in seventy (70) spectral families and 29 individual nodes was obtained, after filtering nodes from background (matrix, agar and solvent). A search of each MS/MS spectrum against GNPS’s spectral libraries resulted in the dereplication of three compounds including elaiophylin, shearinine D and shearinine F.

Elaiophylin was found in a seven (7) nodes cluster in which all ions were produced by Streptomyces CBR53 in single culture and interaction with Escovopsis TZ49 (Fig. 2C and Supplementary Fig. S5); dereplication of these nodes using the AntiMarin database resulted in the identification of additional metabolites including efomycin G43, 48 and efomycin A48, along with the elaiophylin double-charged adduct [M + 2Na]2+ (Fig. 2C, Supplementary Figs S6 and S7).

HRESIQTOF MS2 analysis of efomycin G at m/z 1033.5742 [M + Na]+ (calculated for C54H88O18Na, 1033.5706) showed three mayor fragments at m/z: 411.1819, 715.3734 and 729.3860 which correspond to the aglycone and the cleavage of the nonsymmetrical groups between carbons 9-10 and 9″-10″ respectively, probably following a retro-heteroene rearrangement49, 50 (Supplementary Fig. S6). In a similar way efomycin A showed a fragmentation pattern consisting of three mayor fragments at m/z: 411.1800 which correspond to the aglycone; and the ions at m/z 743.3699 and 729.3763, which indicate a cleavage of the nonsymmetrical groups between carbons 9–10 and 9′′–10′′ (Supplementary Fig. S7).

We were unable to dereplicate three nodes of the elaiophylin cluster at m/z 1065.60, 1079.61 and 1093.62, with mass variations of 18, 32 and 46 Daltons compared to elaiophylin. These mass shifts suggests the presence of an extra atom of oxygen for node m/z 1065.60, two extra oxygen atoms for m/z 1079.61 and two extra oxygen plus a methyl group for m/z 1093.62 (Supplementary Fig. S8). These compounds are very likely new members of the elaiophylin family and their isolation and structural determination are needed in order to identify them.

Additionally a cluster of twenty three (23) nodes composed of metabolites produced by the Escovopsis sp. TZ49 in single culture and in the interaction with Streptomyces CBR53 was observed (Fig. 2B). Manual comparison of the MS/MS spectra of the nodes found in this cluster against the GNPS library resulted in the dereplication of shearinines D and F51 (Supplementary Figs S9 and S10). One of the nodes of the shearinines cluster at m/z 602.35200 didn’t match with any compound at the GNPS library, however it matched with shearinine J at the AntiMarin database.

The antimicrobial activity of elaiophylin was evaluated against several bacteria and fungi including Escovopsis (TZ49 and ACRO424), Aspergillus fumigatus, Candida albicans, Staphylococcus aureus subsp. aureus and Bacillus. subtilis subsp. subtilis. Elaiophylin did not show activity against the Escovopsis and Aspergillus strains assessed in this study, however antibacterial activity was observed against S. aureus subsp. aureus showing a minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of 13.7 µM; also against B. subtilis subsp. subtilis with a MIC value of 17.0 µM; and mild activity was observed against C. albicans with a MIC value of 102.2 µM.

Elaiophylin was also evaluated against parasites (IC50 value of 0.68 µM against the Plasmodium falciparum strain HB3, IC50 of 0.946 µM against Trypanosoma cruzi), and human breast cancer (IC50 value of 0.67 µM for the MCF-7 cell line).

Identification of metabolites using MALDI IMS and molecular networking of extracts from Streptomyces CBR38 and Escovopsis ACRO424

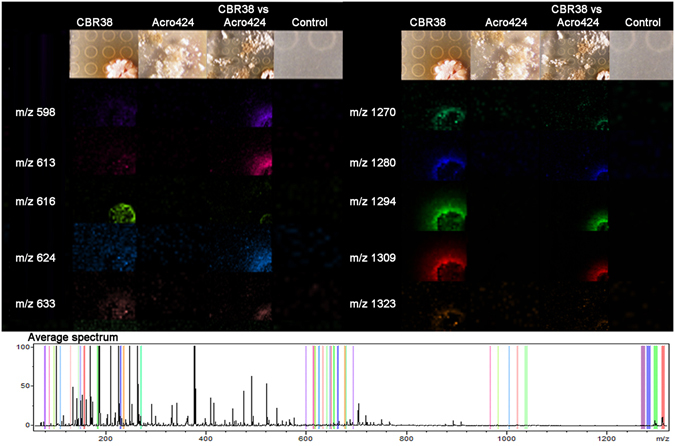

A pairwise interaction experiment among Streptomyces sp. CBR38 and Escovopsis ACRO424, both isolated from Acromyrmex echinatior nest, was carried out with the aim of understanding the microbial interaction between beneficial and antagonist microbes of this higher attine group. Co-culture in SFM media of Streptomyces sp. CBR38 and Escovopsis sp. ACRO424 for 10 days resulted in a clear inhibition of the fungi displaying an inhibition zone diameter of 4.49 ± 0.15 mm. MALDI IMS was used to elucidate the spatial spreading of metabolites in the interaction. The results showed several ions surrounding the bacterial growing, for instance m/z 624, 633, 1270, 1294 and 1309 (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. S11). These metabolites were detected in the single culture of Streptomyces sp. CBR38 (Fig. 3: CBR38) and during the pairwise experiment of Streptomyces sp. against Escovopsis sp. (Fig. 3: CBR38 vs ACRO424; Supplementary Fig. S11). Only one metabolite was assigned in association with the fungi at m/z 270 (Fig. S11).

Figure 3.

MALDI-TOF imaging mass spectrometry experiment of the bacterium Streptomyces CBR38 vs Escovopsis ACRO424. Selected ions observed in the microbial interaction are presented as columns, first column show mass to charge ratio, second to fifth columns display false-colored images of the spatial distribution of the ions detected around: Streptomyces CBR38; Escovopsis ACRO424; Streptomyces sp. vs Escovopsis sp.(CBR38 vs ACRO424); and SFM Agar. Average mass spectrum highlighting all the selected ions is show at the bottom.

The chemical profile of the ethyl acetate extract of Streptomyces sp. (CBR38) carried out by high resolution IT-FTICRMS showed ions at m/z 1255.6578, 1269.6329 and 1271.6213 which corresponded to the [M + H]+ adducts of the ions visualized in the MALDI IMS (1294 [M + H + K]+, 1309 [M + H + K]+ and 1270 Fig. 3) experiments. Dereplication of these ions using the AntiMarin database matched with actinomycin D and actinomycin X2 and actinomycin X0β 52, respectively.

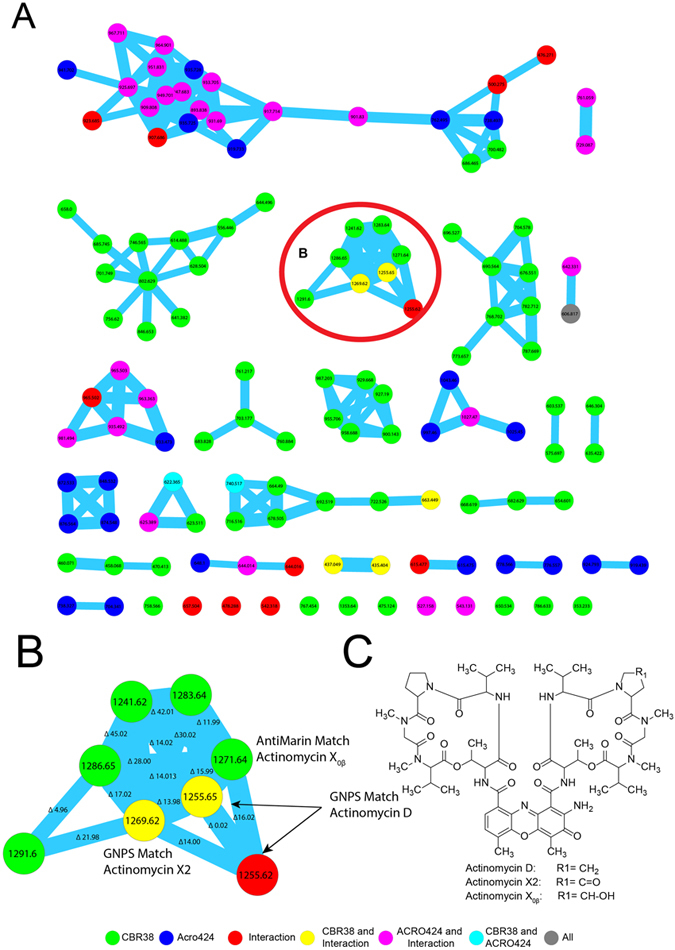

In order to confirm the identity of these compounds we used the HRESI-Q-TOF MS/MS data of the methanol extract of: Streptomyces sp. CBR38, Streptomyces sp. CBR38 vs Escovopsis sp. ACRO424 interaction and Escovopsis ACRO424, in order to create a molecular network using the online workflow at GNPS (http://gnps.ucsd.edu/ProteoSAFe/status.jsp?task=7043d3de65554f7aa127d343191abf6c). As a result we obtained a molecular network consisting of one hundred twenty five (125) nodes, clustered in twenty three molecular families and twelve individual nodes, after filtering nodes from matrix (agar and solvent) (Fig. 4A). Analysis of this data showed a cluster of eight nodes (Fig. 4B) containing the ions m/z 1255.6400, 1269.6200 and 1271.6415, among others. Search of each MS2 spectrum of these ions against GNPS’s spectral libraries resulted in the dereplication of actinomycin D, actinomycin X2, and actinomycin X0β (Fig. 4C). Actinomycin D at m/z 1255.6578, showed a cosine score of 0.90 and 41 shared peaks. Identification of the compound was supported by direct comparison of the MS2 spectra of actinomycin D (MS/MS from Streptomyces sp. CBR38) with a standard of actinomycin D from GNPS by mirror plot using mMass software53 (Supplementary Fig. S12). The ion m/z 1269.6329 was identified as actinomycin X2 with a cosine score of 0.91 and 49 shared peaks. Direct comparison of MS/MS spectra from GNPS standard of actinomycin X2 by mirror plot confirmed the identity of this compound (Supplementary Fig. S13). The ion m/z 1271.6415 was identified as Actinomycin X0β by direct comparison with MS/MS spectra from GNPS standard of actinomycin X0β (Supplementary Fig. S14). This GNPS-based analysis supported the presence of actinomycins in our bacterial extracts. The dereplication of other ions present in the cluster using AntiMarin Database matched with other members of the vast family of actinomycins, however we were unable to identify all of them because GNPS’s libraries contains only some actinomycin analogues.

Figure 4.

Molecular network from Streptomyces CBR38 and Escovopsis Acro424 with the identification of the actinomycins. (A) Molecular network after filter blank, colors indicate producers of the nodes: Streptomyces CBR38 green; Escvopsis ACRO424 blue, Streptomyces sp. vs Escovopsis sp (CBR38 vs ACRO424) red. Nodes found in more than one producers are represented as combination of their colors: Streptomyces CBR38, Streptomyces sp. vs Escovopsis CBR38 vs ACRO424 yellow; Escvopsis ACRO424, Streptomyces sp. vs Escovopsis sp (CBR38 vs ACRO424) pink; Streptomyces CBR38, Escvopsis ACRO424 cian. (B) Enlarged cluster of actinomycin D, actinomycin X2 and actinomycin X0β. (C) Chemical structures of actinomycin D, actinomycin X2 and actinomycin X0β.

Discussion

Microbes in the attine ant system use their biosynthetic machinery to produce metabolites dedicated to interact with the host, and also with other microbial symbionts in the system. However the specific purposes for which each of these metabolites are primarily produced remains unknown. Through microbial interactions using metabolites, microbes likely: get access to nutrients and also obtain protection and adaptation to different ecological niches54. Attine ants maintain a complex symbiotic system in which microbial interactions play a key role to keep the equilibrium in the fitness of the community, involving host-symbiont relationship and symbiont-symbiont microbial interactions.

Herein a combination of MALDI imaging mass spectrometry (MALDI-IMS) and mass spectrometry-based molecular networking was used to study microbial interactions in the attine ants system, specifically between actinobacteria and Escovopsis. In this work we report the identification of three molecular families associated to microbes in the attine ants system: the elaiophylins from Streptomyces sp. CBR53, the actinomycins from Streptomyces sp. CBR38 and a group of triterpenic indole alkaloids named shearinines from Escovopsis sp.TZ49. Elaiophylin macrolide and its analogues are well known antibiotics produced by several Streptomyces strains, these macrolides are classified as entities of biological interest55 presenting a wide range of antibacterial, antifungal, antiinflamatory, enzyme inhibition and anticancer activities43, 46, 48, 56–59. The actinomycins present a wide range of antifungal34, 60–64 antibacterial65 and anticancer66, 67 properties. On the other hand, the shearinines are alkaloids previously reported from fungi in the genus Eupenicillium and Penicillium. These compounds has been reported for anti-leukemia activity68, and also exhibit in vitro blocking activity on large-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels51, antiinsectan69 and anti-Candida activities70.

Based on our results and the known biological activities of the compounds reported in this work we suggest that the actinomycins D, X2 and X0β found in the Streptomyces sp. CBR38, are involved in the fungistatic action of this bacterium against Escovopsis, due to they were found distributed around the inhibition zone, observed in the MALDI IMS experiments (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. S11). On the other hand the elaiophylin and its analogues, found in Streptomyces sp. CBR53, are widely known for their antibacterial activity; hence we suggest they are more likely involved in the control of bacteria present in the nest of Acromyrmex ants.

Our data suggest that ant colonies require constant production of these antimicrobial compounds in order to control pathogens present in the nest; since Escovopsis apparently do not exert a stimulus over the bacteria as shown in the MALDI IMS experiments for both bacterial strains (Figs. 1, 3, Supplementary Figs S1, S2 and S11). The molecular network studies also show that some metabolites belong to Streptomyces and other to Escovopsis (Figs 2 and 4). However it is unknown if the ants could influence the production of this bacterial metabolites during infections of their nest. Currie et al. demonstrated that an increase in the concentration of actinobacteria associated to ants occurs after the inoculation of Escovopsis in the nest. They inferred this increase of actinomycetes bacteria as an strategy to control Escovopsis infection and proliferation13. Based on our results, we support the hypothesis of Currie et al. suggesting that an increase in the concentration of bacteria would result in an increase in the concentration of secreted compounds. However, there is no evidence of the minimal concentrations of bacteria required to control Escovopsis using these compounds, neither if there is an inhibition of the production of compounds by the bacteria once an optimum concentration is reached.

MALDI IMS experiments allowed us to detect few metabolites from Escovopsis, this result could be explained because of the sample pre-treatment, in which the excessive amount of mycelia produced by Escovopsis was removed and only a minimum amount is present in the target plate before applications of the ionization matrix71. This procedure may also disturb the agar surface affecting the shape or thickness of the agar which result in a distortion of the mass spectra, making the manual analysis of the data more challenging as it introduces small mass shifts (0.5 to 1 Da) to the parent mass. However, the HRESI-Q-TOF MS/MS data of the methanol extract of Escovopsis sp. TZ49 allowed us to identify the shearinines D, F and J. The identification of these compounds support the computational predictions of terpene secondary metabolites in the genome Escovopsis weberi 72.

Earlier studies (Table 1) consistently demonstrate that ants employ a community of bacteria to synthetize a variety of compounds for the control of Escovopsis and entomopathogens. Our results also report a high number of compounds produced by bacteria, established by the presence of ions observed in the MALDI IMS experiments.

In this work we describe the presence of three molecular families represented by the macrolide antibiotic elaiophylin isolated from Streptomyces CBR53; the actinomycins detected in Streptomyces CBR38 and the shearinines detected in Escovopsis TZ49 using IT-FTICRMS or HRESI-TOFMS combined with MS2 fragmentation experiments of the extracts. These metabolites were detected around the inhibition zones in the MALDI IMS experiments carried out for each bacteria and fungi. However more detailed studies must be conducted in order to characterize all the ions observed in the MALDI IMS experiments (Figs. 1, 3, Supplementary Figs S1, S2 and S11) and also all the ions observed in the molecular cluster of each bacteria generated by GNPS, twenty two unidentified clusters from Streptomyces CBR38-Escovopsis ACRO424 and sixty eight from Streptomyces CBR53- Escovopsis TZ49. Despite the fact that in this work we are characterizing the occurrence of three molecular families for these strains, MALDI IMS and GNPS tools suggests that the diversity of compounds associated with these bacteria and fungi is much greater than what it is reported in the scientific literature (Table 1).

We propose that the use of a diversity of chemicals is a strategy used by ants and their associated bacteria to reduce the chance of pathogens (opportunistic bacteria, fungi, yeast or the specialized pathogens Escovopsis sp.) for developing antibiotic resistance73. This hypothesis is based on the presence of multiple antibiotics, like the elaiophylins (and its related nodes not yet identified visualized as circular nodes in (Fig. 2C) or, actinomycin D, actinomycin X2 and actinomycin X0β(Fig. 4C), found in the inhibition zones produced by the Streptomyces strains26, 60.

A diversity of chemicals have been reported for the attine ants symbiotic system, including: i) the antibiotics produced by the actinobacteria and other bacteria23, 24, 26, 27 (ii) the metabolites secreted by the ants exocrine glands21, 22, 73–75 and (iii) the metabolites produced by cultivated fungus76. We postulate that the pressure exerted by the presence of this diversity of chemicals is used to avoid and control infections in the ant nest.

Our MALDI-IMS analysis and molecular networking of both bacteria revealed that elaiophylins and actinomycins were produced by the bacteria in the absence and presence of the pathogen Escovopsis, (Figs 1, 2, 3, 4, Supplementary Figs S1, S2 and S11), therefore we deduce that Escovopsis do not induce the production of these compounds. These effects correspondingly indicate a secondary prophylactic use of antibiotics in the nest of A. echinatior because of the permanent production of antibiotics by the bacteria. Similarly the production of shearinine alkaloids by Escovopsis TZ49 was not influenced by the precense of Streptomyces CBR53.

Understanding the chemistry and biology of the attine ant symbiotic system represent opportunities for new research lines that target the ecological importance of complex symbiotic systems, and also using those systems to explore the use of their chemical diversity in drug discovery. For instance, the fact that eliaophylin macrolide showed antibacterial, anticancer, antimalarial and antitrypanosomal activities in our assays clearly indicate the high potential for drug discovery of the natural products involved in this system.

Further studies including metagenomic, metatranscriptomic and metabolomic approaches would help to understand better the compositions of the microbial communities, their interactions and would give new insights on the influence of external factors in the regulation of their activities77, 78. It would also unlock substantial information of uncultured microbial diversity79. Furthermore, the chemical diversity should be assessed using comprehensive methodologies based on mass spectrometry which offers a valuable analysis of microbial proteomes and metabolomes80, potentially providing new molecules with therapeutic and biotechnological applications.

Other specific studies should be designed to clarify the fitness cost of antibiotics production and development of antibiotic resistance on the attine ant-microbe symbiotic system through direct and indirect interactions among all microorganisms19, 20 in order to understand how the microbial populations are organized and modulated81. Metabolic pathways also must be considered to evaluate if the pathways are silent, expressed only in the present of specific stimulus or under particular environmental conditions or activated permanently to produce metabolites82–84.

Conclusions

Mass spectrometry-based techniques such as MALDI-IMS and MS/MS molecular networking revealed, for the first time, metabolites that are directly involved in antagonistic interactions between actinobacteria associated with A. echinatior against the pathogen Escovopsis and other microbes. The presence of actinomycin D and actinomycin X2, two metabolites previously reported from ant-associated bacteria is confirmed. Moreover we are reporting the occurrence of actinomycin X0β in this system. Additionally we isolated and characterized the antibiotic elaiophylin and identified two analogs including efomycin A and efomycin G from Streptomyces CBR53. Also we detected the presence of the shearinines D, F and J for the first time associated with the fungal pathogen Escovopsis TZ49. Actinomycin X0β, the elaiophylins and the shearinines are reported for the first time in the attine ant symbiotic system.

Furthermore MALDI-IMS revealed that compounds were produced by the bacteria and fungi in the absence and presence of their antagonist microbes, suggesting that these microbes do not induce the production of these compounds on the others. These results likewise advocate a secondary prophylactic use of antimicrobials in the nest of A. echinatior because of their permanent production by the bacteria. Hence our work demonstrates that single bacterial strain produces multiple ions that are present on the inhibition zone. We also demonstrate the robustness of the molecular networking as an efficient strategy for dereplication to study microbial metabolites38.

Finally our results reveal the great potential of metabolites involved in microbial interactions of the attine ant symbiotic system to drug discovery, which demonstrated a variety of biological activities against microorganisms and parasites relevant to public health.

Methods

Study organisms

Acromyrmex echinatior and Trachymyrmex zeteki nests were collected85, 86 along Pipeline road, Gamboa, Panamá, in August of 2010, and in Boquerón, Chiriquí, Panamá, in December 2011. Ant nests, including the queen, workers, brood, and fungal gardens were placed in plastic containers85, 86, transported to the laboratory where they were fed and supplied with water twice times per week until studied.

Cuticular bacteria were obtained by directly scraping the propleura of A. echinatior ants over chitin agar media supplemented with cycloheximide and nystatin87. Purification of the bacterial strains was carried out by re-plating the different colonies on mannitol soy flour agar (SFM) until an axenic strain was obtained.

Escovopsis sp. fungus were isolated by collecting small pieces of the fungus garden (<0.5 cm diameter) of A. echinatior and T. zeteki and left onto a moist chamber upon fungus grows, presence of subglobose brown conidia88 confirm that the samples were Escovopsis. Purification was carried out by passages over potato dextrose agar (PDA)89.

DNA extraction and sequencing

DNA of fungal isolates were extracted using the Gentra Puregene Tissue kit (Qiagen, Valencia CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and the ITS locus amplified and sequenced90. The 16S rDNA of bacteria were PCR amplified directly from pure culture of bacteria91. The 16S rDNA gene was sequenced using the BigDye Terminator sequencing kit v 3.1, in an ABI PRISM ®3100 Genetic Analyser (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). DNA sequences were quality evaluated using the software Sequencher (Gene Codes Corporation, Ann Arbor, MI) and compared to the nucleotide database of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (Blast)92. Genus names of sequenced isolates were provided based on >99% DNA sequence similarity to reference strains in the database.

Pairwise microbial interactions

Antagonistic interactions between bacteria and the Escovopsis were done in Petri dishes of 90 × 15 mm filled with 10 mL of mannitol soya flour medium (SFM)89. SFM was inoculated with 0.5 µL of the spore suspension of bacteria (~6 × 106 CFU) and cultivated for ~3 days, spore of Escovopsis (~6 × 106 CFU) were them inoculated at 5 mm from the border of the bacterial colony and the plates were cultivated for ~3 days at room temperature (at 25 °C). Control plates with single cultures were grown in parallel under the same conditions.

Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization imaging mass spectrometry (MALDI-IMS)

To perform MALDI-IMS a small section of SFM agar (20 mm2) containing the cultured microorganisms were cut and transferred to a MALDI MSP 96 anchor plate93. The fungal spores and aerial mycelia were removed using a cotton swab dampened in acetonitrile71, followed by dry deposition of universal matrix (1:1 mixture of 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid and α-cyano-4-hydroxy-cinnamic acid) over the agar using a 53 µm molecular sieve, plates were dried at 37 °C for 10 hours, and photograph was taken before MALDI analysis. Samples were analyzed using a Bruker Autoflex MALDI-TOF mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics, Billerica, MA, USA) or a Bruker Microflex MALDI-TOF mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics, Billerica, MA, USA) in positive reflectron mode, with 500 µm–600 µm laser intervals in X and Y directions, and a mass range of 60–2500 Da. Data obtained were analyzed using FlexImaging 3.0 software (Bruker Daltonics, Billerica, MA, USA). Resulting images were processed using ImageJ 1.47 V software (Research Services Branch, National Institute of Mental Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) fractionation experiments

Extracts of microbial interactions were obtained by macerating 20 mm2 of SFM agar in 1000 µL of ethyl acetate or methanol for three hours and centrifuged at 4000 rpm. The supernatant was removed and analyzed using an ion trap-Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometer (IT-FTICRMS) or using electrospray ionization quadrupole- time of flight mass spectrometer (ESI-Q-TOF-MS).

For IT-FTICRMS analyses extracts were diluted 1:10 in electrospray mixture (49.5% MeOH, 49.5% H2O, 1% formic acid) and directly infused into the mass spectrometer 6.42 T Thermo Finnigan LTQ-FT-ICR (Thermo-Electron Corporation, San Jose, CA) using a TriVersa NanoMate chip-based electrospray ionization source (Advion Biosystems). Back pressure of 0.35–0.5 psi and spray voltage of 1.35–1.45 kV was used for the sample infusion. MS instrument was tuned with the 15+ charge state of Cytochrome C m/z 816 (isolation width: 1 m/z; activation Q: 0.25; activation time: 30 ms) using Tune Plus software version 1.0. Extracts and standards were run using QualBrowser software version 1.4 SR1 (Thermo) and consisted of one 10 minute segment, in which a high resolution FT profile mode scan cycled with four MS/MS data-dependent scans in the ion trap. MS/MS fragments were acquired for the four most intense ions of the FT scan by collision induced dissociation (CID) (isolation width: 2 m/z; activation Q: 0.25; activation time: 30 ms; Normalized collision energy: 35.0). After fragmentation the most intense ions were placed on a dynamic exclusion list for 600 s.

For ESI-Q-TOF-MS analyses extracts were diluted in methanol at 0.5 mg/mL and analyzed with an Agilent 1290 Infinity LC system (Agilent technologies, Santa Clara, CA) using a Kinetex® 1.7 µm C18 100 Å, LC Column 50 × 2.1 mm (Phenomenex Inc, Torrance, CA) and micrOTOF-Q III™ mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics, Billerica, MA, USA) supplied with a electrospray ionization source (ESI). The gradient for chromatographic separation was carried out using a step UPLC run of methanol and acidified water (99.9% water and 0.1% formic acid), 8 min gradient from 10% methanol and 90% acidified water to 100% methanol, held at 100% methanol for 8 min at a flow rate of 0.3 mL/min throughout the run. MS spectra were acquired in positive ion mode in the range of 50–2225 m/z using data depend MS/MS fragmentation as described by Garg et al.94. Prior to data collection an external calibration with Agilent ESI-L Low Concentration Tuning Mix (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) was performed and throughout the runs we use reserpine (Sigma-Aldrich Co. LLC.) for lock mass calibration.

Molecular networking

MS raw data obtained in the MS2 fractionation experiments were converted to 32 bit mzXML file using Bruker Compass Data analysis v4.1 (Bruker Daltonics, Billerica, MA, USA) or MSConvert GUI (ProteoWizard)95. Once all raw data from extracts and standards were converted to mzXML format, these were analyzed using mass spectral molecular networking96, 97, as described by Watrous et al. and Yang et al.36, 39. Data analysis included the following parameters: cosine threshold set at 0.6 value, precursor mass tolerance of 1.0 Da, fragment mass tolerance of 0.3 Da, minimum number of matched peaks per spectral alignment of 6, consensus spectra for cosine score higher than 0.95, parent mass tolerance of 1.0 Da, minimum percentage of overlapping masses between two spectra of 45%, minimum percentage of matched peaks in a spectral alignment of 40%, using global natural products social molecular networking platform (GNPS, http://gnps.ucsd.edu)38.

Visualization of the network as nodes and edges was done using Cytoscape 2.8.098 by importing clustering data and MATLAB attributes of the network98. A graph-drawing force-directed algorithm that uses the Fast Multipole Multilevel Method (FM3) was applied to the data set to organize and align the nodes within the network99. Other visual parameters were adjusted using VizMappers™, the node colors were illustrated according to the source of the precursor ions, and the edge thickness attribute is an interpretation cosine similarity score, with thicker lines indicating higher similarity. Sub-networks were created from selected parts of the complete network to show details of node connectivity.

Identification of metabolites

The purification of the compounds was carried out using solid phase extraction cartridge Supelclean™ LC-18 SPE Tube (Supelco Inc, Bellefonte, PA) eluted with a step gradient of 20%, 40%, 60%, 80%, and 100% of methanol in water, followed by HPLC separation using reverse phase silica gel column Synergi™ Fusion-RP (Phenomenex Inc, Torrance, CA), eluted with methanol:water, 40 min gradient from 60% methanol and 40% water to 100% methanol, held at 100% methanol for 20 min at a flow rate of 1 mL/min throughout the run.

NMR spectra were acquired on a Jeol Eclipse 400 MHz spectrometer and referenced to residual solvent 1H and 13C signals δH 3.31, δC 49.00 for Methanol-d6. Metabolites were dereplicated by comparing high resolution MS data using AntiMarin database (University of Canterbury, Christchurch, New Zealand) and chemical literature23, 24, 26, 27. Additionally, we annotated selected MS2 fractionation patterns of bacterial metabolites and comparing them with MS2 of commercial standards using GNPS public spectral libraries Version 1.2.8-GNPS (University of California at San Diego, La Jolla, CA)38.

In vitro bioassays

Compounds isolated were tested in bioassays against the human breast cancer cell line MCF-7100, the malaria parasite (Plasmodium falciparum)101, 102 and the Chagas’ disease causative agent (Trypanosoma cruzi)100, 103, 104, Escovopsis ACRO424 and TZ49, Aspergillus fumigatus (ATCC® 1028™)105, Candida albicans (ATCC® 10231™), Staphylococcus aureus subsp. aureus (ATCC® 43300™) and Bacillus subtilis subsp. subtilis (ATCC® 6051™)106, 107 (See Supplementary methods).

Data availability statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article (and its Supplementary Information files). MS data is deposited in the GNPS MassIVE repository under the accession number: MSV000081208.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This work was partially supported by National Secretariat for Science and Technology of Panama (SENACYT COL09-047 and FID14-171), the Fogarty International Center’s International Cooperative Biodiversity Groups program (TW006634). Cristopher Boya thanks SENACYT-IFARHU for financial support. We gratefully acknowledge the Government of Panama (Ministerio de Ambiente) for granting permission to collect the ants used in this study. Thanks to Julia Jones, Cristina Botias, Tobias Pamminger and William Hughes for English edition in the early draft, which were supported by Panama Science and Innovation fund from the British Embassy at Panama City. HFM, LCM, CS and MG acknowledge SNI-SENACYT for financial support.

Author Contributions

M.G. and H.F.M. design the project. C.B. and H.F.M. collected field colonies. L.C.M. performed the DNA sequencing and taxonomic identification of the sequences. C.S. executed in vitro bioassays. C.B. performed bacterial and fungal isolation, sample preparation, MS data generation and analysis, NMR acquisition and analysis. C.B., H.F.M., P.D. and M.G. wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at doi:10.1038/s41598-017-05515-6

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Chaves S, Neto M, Tenreiro R. Insect-symbiont systems: from complex relationships to biotechnological applications. Biotechnol. J. 2009;4:1753–65. doi: 10.1002/biot.200800237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stella JS, Munday PL, Walker SPW, Pratchett MS, Jones GP. From cooperation to combat: adverse effect of thermal stress in a symbiotic coral-crustacean community. Oecologia. 2014;174:1187–95. doi: 10.1007/s00442-013-2858-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scheuring I, Yu DW. How to assemble a beneficial microbiome in three easy steps. Ecol. Lett. 2012;15:1300–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2012.01853.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koren O, Rosenberg E. Bacteria associated with mucus and tissues of the coral Oculina patagonica in summer and winter. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006;72:5254–9. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00554-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shnit-Orland M, Kushmaro A. Coral mucus-associated bacteria: a possible first line of defense. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2009;67:371–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2008.00644.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Foster KR, Parkinson K, Thompson CRL. What can microbial genetics teach sociobiology? Trends Genet. 2007;23:74–80. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reznikova JI. Interspecific communication between ants. Behaviour. 1982;80:84–95. doi: 10.1163/156853982X00454. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nadell CD, Xavier JB, Foster KR. The sociobiology of biofilms. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2009;33:206–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2008.00150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xavier JB, Martinez-Garcia E, Foster KR. Social evolution of spatial patterns in bacterial biofilms: when conflict drives disorder. Am. Nat. 2009;174:1–12. doi: 10.1086/599297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith CR, Dolezal A, Eliyahu D, Holbrook CT, Gadau J. Ants (Formicidae): models for social complexity. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2009;4:1–13. doi: 10.1101/pdb.emo125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paul VJ, Puglisi MP. Chemical mediation of interactions among marine organisms. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2004;21:189–209. doi: 10.1039/b302334f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boya CA, Herrera L, Guzman HM, Gutierrez M. Antiplasmodial activity of bacilosarcin A isolated from the octocoral-associated bacterium Bacillus sp. collected in Panama. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2012;4:66–9. doi: 10.4103/0975-7406.92739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Currie CR, Bot ANM, Boomsma JJ. Experimental evidence of a tripartite mutualism: bacteria protect ant fungus gardens from specialized parasites. Oikos. 2003;101:91–102. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0706.2003.12036.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weber NA. Fungus-growing ants. Science. 1966;153:587–604. doi: 10.1126/science.153.3736.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schultz TR, Brady SG. Major evolutionary transitions in ant agriculture. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:5435–40. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711024105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mueller UG. Ant versus fungus versus mutualism: ant-cultivar conflict and the deconstruction of the attine ant-fungus symbiosis. Am. Nat. 2002;160:S67–S98. doi: 10.1086/342084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Caldera EJ, Poulsen M, Suen G, Currie CR. Insect symbioses: a case study of past, present, and future fungus-growing ant research. Environ. Entomol. 2009;38:78–92. doi: 10.1603/022.038.0110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Currie CR, Mueller UG, Malloch D. The agricultural pathology of ant fungus gardens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:7998–8002. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.14.7998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Little AEF, Currie CR. Black yeast symbionts compromise the efficiency of antibiotic defenses in fungus-growing ants. Ecology. 2008;89:1216–22. doi: 10.1890/07-0815.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Little AEF, Currie CR. Symbiotic complexity: discovery of a fifth symbiont in the attine ant-microbe symbiosis. Biol. Lett. 2007;3:501–4. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2007.0253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fernández-Marín H, Zimmerman JK, Rehner SA, Wcislo WT. Active use of the metapleural glands by ants in controlling fungal infection. Proc. R. Soc. London B Biol. Sci. 2006;273:1689–95. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2006.3492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fernández-Marín H, et al. Dynamic disease management in Trachymyrmex fungus-growing ants (Attini: Formicidae) Am. Nat. 2013;181:571–82. doi: 10.1086/669664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carr G, Derbyshire ER, Caldera E, Currie CR, Clardy J. Antibiotic and antimalarial quinones from fungus-growing ant-associated Pseudonocardia sp. J. Nat. Prod. 2012;75:1806–9. doi: 10.1021/np300380t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oh D, Poulsen M, Currie CR, Clardy J. Dentigerumycin: a bacterial mediator of an ant-fungus symbiosis. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2009;5:391–393. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Freinkman E, Oh D-C, Scott JJ, Currie CR, Clardy J. Bionectriol A, a polyketide glycoside from the fungus Bionectria sp. associated with the fungus-growing ant. Apterostigma dentigerum. Tetrahedron. 2009;50:6834–6837. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2009.09.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barke J, et al. A mixed community of actinomycetes produce multiple antibiotics for the fungus farming ant Acromyrmex octospinosus. BMC Biol. 2010;8:109. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-8-109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Seipke RF, et al. A single Streptomyces symbiont makes multiple antifungals to support the fungus farming ant Acromyrmex octospinosus. PLoS One. 2011;6:e22028. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Currie CR, Scott JA, Summebell RC, Malloch D. Fungus-growing ants use antibiotic-producing bacteria to control garden parasites. Nature. 1999;398:701–705. doi: 10.1038/19519. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mattoso TC, Moreira DDO, Samuels RI. Symbiotic bacteria on the cuticle of the leaf-cutting ant Acromyrmex subterraneus subterraneus protect workers from attack by entomopathogenic fungi. Biol. Lett. 2012;8:461–4. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2011.0963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Currie CR, Poulsen M, Mendenhall J, Boomsma JJ, Billen J. Coevolved crypts and exocrine glands support mutualistic bacteria in fungus-growing ants. Science. 2006;311:81–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1119744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Poulsen M, Erhardt DP, Molinaro DJ, Lin T-L, Currie CR. Antagonistic bacterial interactions help shape host-symbiont dynamics within the fungus-growing ant-microbe mutualism. PLoS One. 2007;2:e960. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haeder S, Wirth R, Herz H, Spiteller D. Candicidin-producing Streptomyces support leaf-cutting ants to protect their fungus garden against the pathogenic fungus. Escovopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:4742–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812082106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Van Arnam EB, et al. Selvamicin, an atypical antifungal polyene from two alternative genomic contexts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2016;113:12940–12945. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1613285113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schoenian I, et al. Chemical basis of the synergism and antagonism in microbial communities in the nests of leaf-cutting ants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:1955–60. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008441108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mendes TD, et al. Anti-Candida properties of urauchimycins from actinobacteria associated with Trachymyrmex ants. Biomed Res. Int. 2013;2013:1–8. doi: 10.1155/2013/835081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Watrous J, et al. Mass spectral molecular networking of living microbial colonies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:E1743–52. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1203689109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Esquenazi E, Yang Y-L, Watrous J, Gerwick WH, Dorrestein PC. Imaging mass spectrometry of natural products. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2009;26:1521–1534. doi: 10.1039/b915674g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang M, et al. Sharing and community curation of mass spectrometry data with global natural products social molecular networking. Nat. Biotechnol. 2016;34:828–837. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang JY, et al. Molecular networking as a dereplication strategy. J. Nat. Prod. 2013;76:1686–99. doi: 10.1021/np400413s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moree WJ, et al. Imaging mass spectrometry of a coral microbe interaction with fungi. J. Chem. Ecol. 2013;39:1045–54. doi: 10.1007/s10886-013-0320-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nguyen DD, et al. MS/MS networking guided analysis of molecule and gene cluster families. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:E2611–20. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1303471110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kaiser H, Keller-Schierlein W. Structure elucidation of elaiophylin: spectroscopic studies and degradation. Helv. Chim. Acta. 1981;64:407–424. doi: 10.1002/hlca.19810640206. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nakakoshi M, Kimura K, Nakajima N, Yoshihama M, Uramoto M. SNA-4606-1, a new member of elaiophylins with enzyme inhibition activity against testosterone 5 alpha-reductase. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo) 1999;52:175–7. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.52.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Iwasaki S, Namikoshi M, Sasaki K, Fukushima K, Okuda S. Studies on macrocyclic lactone antibiotics. V. The structures of azalomycins F3a and F5a. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1982;30:4006–4014. doi: 10.1248/cpb.30.4006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sheng Y, et al. Identification of elaiophylin skeletal variants from the indonesian Streptomyces sp. ICBB 9297. J. Nat. Prod. 2015;78:2768–2775. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.5b00752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nair MG, et al. Gopalamicin, an antifungal macrodiolide produced by soil actinomycetes. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1994;42:2308–2310. doi: 10.1021/jf00046a043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Han Y, et al. Halichoblelide D, a new elaiophylin derivative with potent cytotoxic activity from mangrove-derived Streptomyces sp. 219807. Molecules. 2016;21:970. doi: 10.3390/molecules21080970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Frobel, K. et al. Efomycins as performance promoters in animals. United States Pat. 5,073,369, (1991).

- 49.Demarque DP, Crotti AEM, Vessecchi R, Lopes JLC, Lopes NP. Fragmentation reactions using electrospray ionization mass spectrometry: an important tool for the structural elucidation and characterization of synthetic and natural products. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2016;33:432–455. doi: 10.1039/C5NP00073D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang H, Wu Y, Zhao Z. Fragmentation study of simvastatin and lovastatin using electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry. J. Mass Spectrom. 2001;36:58–70. doi: 10.1002/jms.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xu M, et al. Shearinines D–K, new indole triterpenoids from an endophytic Penicillium sp. (strain HKI0459) with blocking activity on large-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels. Tetrahedron. 2007;63:435–444. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2006.10.050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brockmann H, Pampus G, Manegold JH. Actinomycine, XXI. Antibiotica aus Actinomyceten, XLIII. Actinomycin X0β; zur Systematik und Nomenklatur der Actinomycine. Chem. Ber. 1959;92:1294–1302. doi: 10.1002/cber.19590920610. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Strohalm M, Kavan D, Novák P, Volný M, Havlícek V. mMass 3: a cross-platform software environment for precise analysis of mass spectrometric data. Anal. Chem. 2010;82:4648–51. doi: 10.1021/ac100818g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Phelan VV, Liu W-T, Pogliano K, Dorrestein PC. Microbial metabolic exchange–the chemotype-to-phenotype link. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2012;8:26–35. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Degtyarenko K, et al. ChEBI: a database and ontology for chemical entities of biological interest. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D344–50. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.KIM M-S, et al. Structure Determination and Biological Activities of Elaiophylin Produced by Streptomyces sp. MCY -846. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1996;6:245–249. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Supong K, et al. Antimicrobial compounds from endophytic Streptomyces sp. BCC72023 isolated from rice (Oryza sativa L.) Res. Microbiol. 2016;167:290–298. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2016.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Supong K, et al. Investigation on antimicrobial agents of the terrestrial Streptomyces sp. BCC71188. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017;101:533–543. doi: 10.1007/s00253-016-7804-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wu C, et al. Identification of elaiophylin derivatives from the marine-derived actinomycete Streptomyces sp. 7-145 using PCR-based screening. J. Nat. Prod. 2013;76:2153–2157. doi: 10.1021/np4006794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Toumatia O, et al. Antifungal properties of an actinomycin D-producing strain, Streptomyces sp. IA1, isolated from a Saharan soil. J. Basic Microbiol. 2015;55:221–228. doi: 10.1002/jobm.201400202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kristev K, Dimov A. The effect of actinomycin D on the development of leaf rust in susceptible and resistant combinations. Cereal Res. Commun. 1975;3:31–35. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Waksman, S. & Tishler, M. The chemical nature of actinomycin, an anti-microbial substance produced by Actinomyces antibioticus. J. Biol. Chem. (1942).

- 63.Solanki R, Kundu A, Das P, Khanna M. Characterization of antimicrobial compounds from Streptomyces isolates. World J. Pharm. Res. 2015;7:1626–1641. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Taechowisani T, Wanbanjob A, Tuntiwachwuttikul P, Taylor WC. Identification of Streptomyces sp Tc022, an endophyte in Alpinia galanga, and the isolation of actinomycin D. Ann. Microbiol. 2006;56:113–117. doi: 10.1007/BF03174991. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chen C, et al. A marine-derived Streptomyces sp. MS449 produces high yield of actinomycin X2 and actinomycin D with potent anti-tuberculosis activity. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012;95:919–927. doi: 10.1007/s00253-012-4079-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pinkel D. Actinomycin D in Childhood Cancer. Pediatrics. 1959;23:342–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Katz E, Williams WK, Mason KT, Mauger AB. Novel actinomycins formed by biosynthetic incorporation of cis- and trans-4-methylproline. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1977;11:1056–63. doi: 10.1128/AAC.11.6.1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Smetanina OF, et al. Indole alkaloids produced by a marine fungus isolate of Penicillium janthinellum Biourge. J. Nat. Prod. 2007;70:2054–2054. doi: 10.1021/np070296n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Belofsky GN, Gloer JB, Wicklow DT, Dowd PF. Antiinsectan alkaloids: Shearinines A-C and a new paxilline derivative from the ascostromata of Eupenicillium shearii. Tetrahedron. 1995;51:3959–3968. doi: 10.1016/0040-4020(95)00138-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.You J, Du L, King JB, Hall BE, Cichewicz RH. Small-molecule suppressors of Candida albicans biofilm formation synergistically enhance the antifungal activity of amphotericin B against clinical Candida isolates. ACS Chem. Biol. 2013;8:840–8. doi: 10.1021/cb400009f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Moree WJ, et al. Interkingdom metabolic transformations captured by microbial imaging mass spectrometry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:13811–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206855109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.de Man TJB, et al. Small genome of the fungus Escovopsis weberi, a specialized disease agent of ant agriculture. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:3567–72. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1518501113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Fernández-Marín, H. et al. Functional role of phenylacetic acid from metapleural gland secretions in controlling fungal pathogens in evolutionarily derived leaf-cutting ants. Proc. R. Soc. London B Biol. Sci. 282 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 74.Vieira AS, Morgan ED, Drijfhout FP, Camargo-Mathias MI. Chemical composition of metapleural gland secretions of fungus-growing and non-fungus-growing ants. J. Chem. Ecol. 2012;38:1289–1297. doi: 10.1007/s10886-012-0185-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ortius-Lechner D, Maile R, Morgan ED, Boomsma JJ. Metapleural gland secretion of the leaf-cutter ant Acromyrmex octospinosus: new compounds and their functional significance. J. Chem. Ecol. 2000;26:1667–1683. doi: 10.1023/A:1005543030518. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gerardo NM, Jacobs SR, Currie CR, Mueller UG. Ancient host-pathogen associations maintained by specificity of chemotaxis and antibiosis. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e235. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Moran MA. Metatranscriptomics: Eavesdropping on Complex Microbial Communities. Microbe. 2009;4:329–335. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Shi Y, Tyson GW, Eppley JM, DeLong EF. Integrated metatranscriptomic and metagenomic analyses of stratified microbial assemblages in the open ocean. ISME J. 2011;5:999–1013. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2010.189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Handelsman J. Metagenomics: application of genomics to uncultured microorganisms. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2004;68:669–685. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.68.4.669-685.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wilkins, C. L. & Lay, J. O. Identification of microorganisms by mass spectrometry. (John Wiley & Sons, 2005).

- 81.Cordero OX, et al. Ecological populations of bacteria act as socially cohesive units of antibiotic production and resistance. Science. 2012;337:1228–31. doi: 10.1126/science.1219385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Rodríguez H, Rico S, Díaz M, Santamaría RI. Two-component systems in Streptomyces: key regulators of antibiotic complex pathways. Microb. Cell Fact. 2013;12:127. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-12-127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bibb, M. & Hesketh, A. Analyzing the regulation of antibiotic production in Streptomycetes. in Methods in enzymology (eds. Abelson, J. & Simon, M.), 458, 93–116 (Elsevier, 2009). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 84.Huang J, et al. Cross-regulation among disparate antibiotic biosynthetic pathways of Streptomyces coelicolor. Mol. Microbiol. 2005;58:1276–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Weber, N. Gardening Ants: The Attines. (American Philosophical Society, 1972).

- 86.Smith, C. R. & Tschinkel, W. R. Collecting live ant specimens (colony sampling). Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2009, pdb.prot5239 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 87.Cafaro MJ, Currie CR. Phylogenetic analysis of mutualistic filamentous bacteria associated with fungus-growing ants. Can. J. Microbiol. 2005;51:441–446. doi: 10.1139/w05-023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Seifert KA, Samson RA, Chapela IH. Escovopsis aspergilloides, a rediscovered hyphomycete from leaf-cutting ant nests. Mycologia. 1995;87:407–413. doi: 10.2307/3760838. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kieser, T., Bibb, M. J., Buttner, M. J., Chater, K. F. & Hopwood, D. A. Practical Streptomyces Genetics. (John Innes Foundation, 2000).

- 90.Mejía LC, Castlebury La, Rossman AY, Sogonov MV, White JF. Phylogenetic placement and taxonomic review of the genus Cryptosporella and its synonyms Ophiovalsa and Winterella (Gnomoniaceae, Diaporthales) Mycol. Res. 2008;112:23–35. doi: 10.1016/j.mycres.2007.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lane, D. J. 16S/23S rRNA sequencing in nucleic acid techniques in bacterial systematics (eds. Stackebrandt, E. & Goodfellow, M.) 115–175 (John Wiley and Sons, 1991).

- 92.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990;215:403–10. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Yang JY, et al. Primer on agar-based microbial imaging mass spectrometry. J. Bacteriol. 2012;194:6023–8. doi: 10.1128/JB.00823-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Garg, N. et al. Mass spectral similarity for untargeted metabolomics data analysis of complex mixtures. Int. J. Mass Spectrom., doi:10.1016/j.ijms.2014.06.005 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 95.Kessner D, Chambers M, Burke R, Agus D, Mallick P. ProteoWizard: open source software for rapid proteomics tools development. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:2534–6. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Frank AM, et al. Clustering millions of tandem mass spectra. J Proteome Res. 2009;7:113–122. doi: 10.1021/pr070361e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Frank AM, et al. Spectral archives: extending spectral libraries to analyze both identified and unidentified spectra. Nat. Methods. 2011;8:587–591. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Shannon P, et al. Cytoscape: a software Environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003;13:2498–2504. doi: 10.1101/gr.1239303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hachul S, Jünger M. Large-graph layout algorithms at work: an experimental study. J. Graph Algorithms Appl. 2007;11:345–369. doi: 10.7155/jgaa.00150. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Higginbotham SJ, et al. Bioactivity of fungal endophytes as a function of endophyte taxonomy and the taxonomy and distribution of their host plants. PLoS One. 2013;8:e73192. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Trager W, Jensen JB. Human malaria parasites in continuous culture. Science. 1976;193:673–5. doi: 10.1126/science.781840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Corbett Y, et al. A novel DNA-based microfluorimetric method to evaluate antimalarial drug activity. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2004;70:119–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Díaz-Chiguer DL, et al. In vitro and in vivo trypanocidal activity of some benzimidazole derivatives against two strains of Trypanosoma cruzi. Acta Trop. 2012;122:108–12. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2011.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Martínez-Luis S, Gómez JF, Spadafora C, Guzmán HM, Gutiérrez M. Antitrypanosomal alkaloids from the marine bacterium Bacillus pumilus. Molecules. 2012;17:11146–55. doi: 10.3390/molecules170911146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Mejia LC, et al. Endophytic fungi as biocontrol agents of Theobroma cacao pathogens. Biol. Control. 2008;46:4–14. doi: 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2008.01.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Bonev B, Hooper J, Parisot J. Principles of assessing bacterial susceptibility to antibiotics using the agar diffusion method. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2008;61:1295–1301. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkn090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Ericsson H, Tunevall G, Wickman K. The paper disc method for determination of bacterial sensitivity to antibiotics: relationship between the diameter of the zone of inhibition and theminimum inhibitory concentration. Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Invest. 1960;12:414–422. doi: 10.3109/00365516009065406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article (and its Supplementary Information files). MS data is deposited in the GNPS MassIVE repository under the accession number: MSV000081208.