ABSTRACT

Lyme borreliosis is the most common zoonotic disease transmitted by ticks in Europe and North America. Despite having multiple tick vectors, the causative agent, Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato, is vectored mainly by Ixodes ricinus in Europe. In the present study, we aimed to review and summarize the existing data published from 2010 to 2016 concerning the prevalence of B. burgdorferi sensu lato spirochetes in questing I. ricinus ticks. The primary focus was to evaluate the infection rate of these bacteria in ticks, accounting for tick stage, adult tick gender, region, and detection method, as well as to investigate any changes in prevalence over time. The data obtained were compared to the findings of a previous metastudy. The literature search identified data from 23 countries, with 115,028 ticks, in total, inspected for infection with B. burgdorferi sensu lato. We showed that the infection rate was significantly higher in adults than in nymphs and in females than in males. We found significant differences between European regions, with the highest infection rates in Central Europe. The most common genospecies were B. afzelii and B. garinii, despite a negative correlation of their prevalence rates. No statistically significant differences were found among the prevalence rates determined by conventional PCR, nested PCR, and real-time PCR.

IMPORTANCE Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato is a pathogenic bacterium whose clinical manifestations are associated with Lyme borreliosis. This vector-borne disease is a major public health concern in Europe and North America and may lead to severe arthritic, cardiovascular, and neurological complications if left untreated. Although pathogen prevalence is considered an important predictor of infection risk, solitary isolated data have only limited value. Here we provide summarized information about the prevalence of B. burgdorferi sensu lato spirochetes among host-seeking Ixodes ricinus ticks, the principal tick vector of borreliae in Europe. We compare the new results with previously published data in order to evaluate any changing trends in tick infection.

KEYWORDS: Borrelia burgdorferisensu lato, tick, Ixodes ricinus, genospecies, meta-analysis, Lyme borreliosis, Lyme disease

INTRODUCTION

The Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato group includes the causative agents of Lyme borreliosis (LB), the most prevalent human tick-borne disease in the Northern Hemisphere (1). The bacterium is maintained in a horizontal transmission cycle between its vector, ticks of the genus Ixodes, and vertebrate reservoir host species. In Europe, there are a number of different B. burgdorferi sensu lato genospecies, many of them directly associated with human LB. The disease is caused predominantly by Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto, B. afzelii, B. garinii, and B. bavariensis (previously known as B. garinii OspA serotype 4) (2). In addition, four other genospecies are occasionally detected in humans: B. bissettiae (3, 4), B. lusitaniae (5, 6), B. spielmanii (7), and B. valaisiana (8); however, their pathogenicity is still unclear (9).

The principal tick vector for Borrelia species in Europe is the castor bean tick, Ixodes ricinus. To date, B. burgdorferi sensu stricto, B. afzelii, B. garinii, B. valaisiana, B. lusitaniae, B. spielmanii, B. bavariensis, B. bissettiae, B. finlandensis, and B. carolinensis have been detected in I. ricinus ticks (10, 11). Different genospecies display different patterns of host specialization and tissue tropism and are associated with overlapping but distinct spectra of clinical manifestations: B. burgdorferi sensu stricto is most often associated with arthritis and neuroborreliosis, B. garinii with neuroborreliosis, and B. afzelii with chronic skin conditions such as acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans (12). Apart from spirochetes associated with LB, I. ricinus is well recognized as a vector of many other pathogens of veterinary and human medical importance, particularly tick-borne encephalitis virus (TBEV), Babesia spp., spotted fever group rickettsiae, Anaplasma phagocytophilum, and Bartonella spp. (13).

A number of field studies have already pointed to increases in average densities and activities of questing ticks in parts of Europe with long-documented I. ricinus populations (14, 15). Moreover, the distributional area of I. ricinus appears to be steadily shifting toward higher altitudes and latitudes, increasing the total surface area of tick-suitable habitats in many European countries (16–18). However, several studies have identified a strong negative association of tick density with altitude, associated mainly with local climatic conditions (19, 20). Climate changes and their direct effects on vertebrate host distribution, population dynamics, and vegetation are associated with the altitudinal and latitudinal changes in the distribution of I. ricinus (16, 17).

In the present study, we aimed to systematically analyze the existing literature covering the prevalence of B. burgdorferi sensu lato and its different genospecies in host-seeking I. ricinus ticks in Europe. We focused on the evaluation of the prevalence rate in ticks according to tick developmental stage, adult tick gender, region of sampling, and method of detection, as well as investigating any changes in prevalence over time. The work represents a follow-up of the meta-analysis done by Rauter and Hartung (21) in order to reevaluate the spatiotemporal trends in B. burgdorferi sensu lato prevalence after another decade of data accumulation.

RESULTS

Prevalences of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato in ticks at different developmental stages.

Reports published between 2010 and 2016 on the prevalence of B. burgdorferi sensu lato in questing I. ricinus ticks in Europe were reviewed and analyzed (Table 1). Of all 115,028 ticks tested, 14,134 (12.3%) were determined to be positive for the presence of B. burgdorferi sensu lato. The average prevalence per study reached 15.6%.

TABLE 1.

Studies used for the analysis of rates of B. burgdorferi sensu lato infection in I. ricinus ticks in Europe

| Country | Reference(s) |

|---|---|

| Austria | 46–48 |

| Belarus | 50 |

| Belgium | 55 |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | 62 |

| Czech Republic | 75–78 |

| Denmark | 51 |

| Estonia | 83 |

| Finland | 87, 88 |

| France | 11, 51, 75, 92–98 |

| Germany | 14, 23, 75, 95, 100–106 |

| Hungary | 111, 112 |

| Italy | 22, 46, 119–124 |

| Luxembourg | 49 |

| The Netherlands | 51–54 |

| Norway | 56–61, 127, 128 |

| Poland | 63–75 |

| Portugal | 75, 79, 80 |

| Romania | 24, 81, 82 |

| Serbia | 84–86 |

| Slovakia | 89–91 |

| Spain | 99 |

| Switzerland | 10, 107–110, 125, 126 |

| United Kingdom | 113–118 |

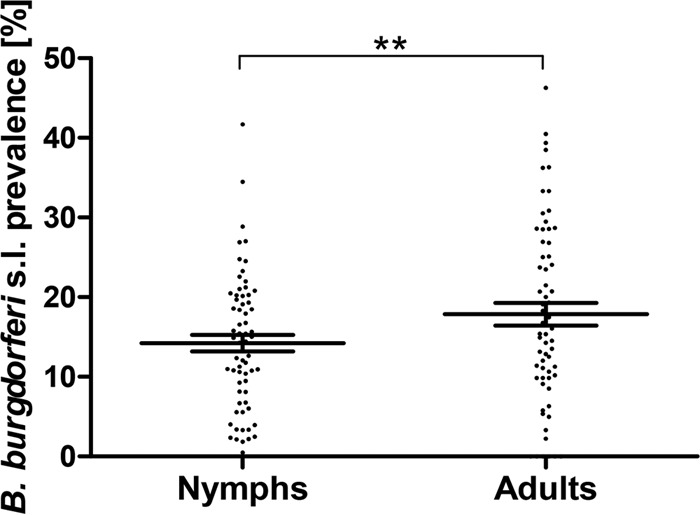

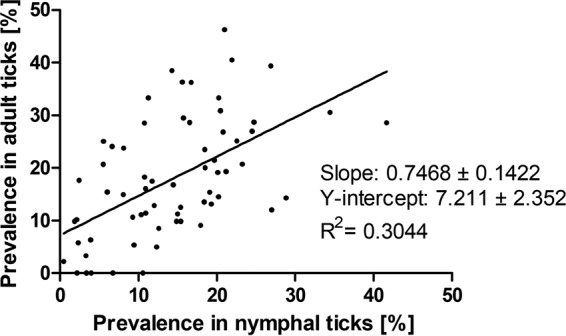

In some studies, only adult or only nymphal ticks were analyzed, or it was not possible to assign the prevalence rate to a specific tick developmental stage. In order to provide a direct comparison of B. burgdorferi sensu lato prevalence among adult and nymphal ticks, we analyzed only those entries (n = 65) where the prevalence rates for both adult and nymphal ticks were reported. In this subset, the prevalence of LB spirochetes reached significantly higher average values for adult (14.9% [3,784/25,377]) than for nymphal (11.8% [6,670/56,401]) ticks (P, <0.001 by the χ2 test). The average prevalence per study reached 17.8% for adult and 14.2% for nymphal I. ricinus ticks. When individual results paired for each study were compared, the difference in the prevalence of B. burgdorferi sensu lato between the tick developmental stages was also statistically significant (P, <0.01 by a paired t test) (Fig. 1). In 61.5% (40/65) of individual entries with both developmental stages analyzed and numbers specified, the prevalence of B. burgdorferi sensu lato in adult ticks surpassed that in nymphs. Considering only entries with more than 100 adult samples analyzed, the prevalence in adults was higher than that in nymphs in 73.2% (30/41) of the entries. A moderate linear correlation was found between the B. burgdorferi sensu lato prevalence rates in adult and nymphal I. ricinus ticks (R2 = 0.30; Pearson's r = 0.5518; P < 0.001) (Fig. 2).

FIG 1.

Comparison of B. burgdorferi sensu lato prevalences in nymphal and adult I. ricinus ticks in Europe. Each dot represents a single entry (locality). Data were extracted from 65 entries where the prevalence rates for both developmental stages were reported. The middle lines represent the means; error bars, standard errors of the means. **, P < 0.01.

FIG 2.

Linear correlation analysis for the prevalence of B. burgdorferi sensu lato in adult and nymphal I. ricinus ticks in Europe. Each dot represents a single entry (locality). Data were extracted from 65 entries where the prevalence rates for both developmental stages were reported.

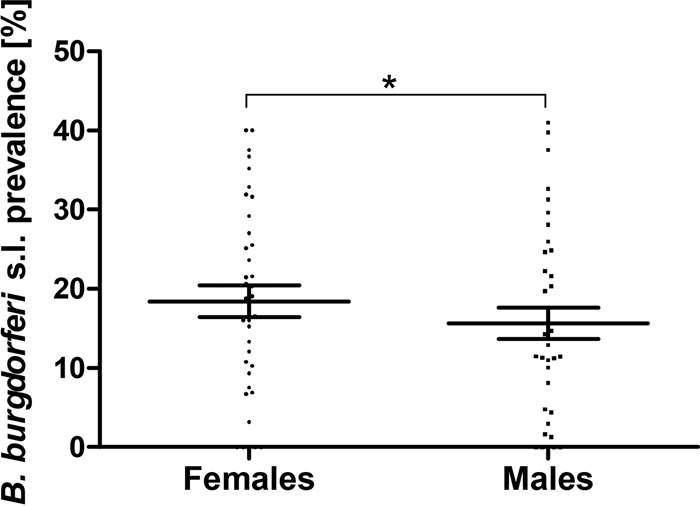

In 37 entries, the adult ticks were included and the prevalence of B. burgdorferi sensu lato was reported for each sex separately. The overall prevalence in females (13.9% [1,271/9,164]) surpassed the prevalence rate in males (11.1% [960/8,664]) (P, <0.001 by the χ2 test). The average prevalence per entry reached 18.4% for females and 15.7% for males. The differences were also statistically significant when paired values for each study were compared (P, <0.05 by a paired Student t test) (Fig. 3). For females, higher prevalence rates were reached in 67.6% (25/37) of the individual studies. When only entries with at least 50 samples of each sex tested were taken into account, the proportion increased to 78.9% (15/19).

FIG 3.

Comparison of B. burgdorferi sensu lato prevalence rates between female and male I. ricinus ticks in Europe. Each dot represents a single entry (locality). Data were extracted from 37 entries where the prevalence rate for each sex was reported. The middle lines represent the means; error bars, standard errors of the means. *, P < 0.05.

Notably, some studies included in the data set reported the detection of B. burgdorferi sensu lato spirochetes in larval I. ricinus (22–24). The overall prevalence among larvae reported in these papers reached 1.5% (17/1,147 [range, 0.4% to 25.8%]).

Prevalence of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato in ticks according to the method of detection.

Although lower mean prevalence rates were determined using simple conventional PCR than using nested PCR or quantitative PCR (qPCR) for the detection of B. burgdorferi sensu lato in all tick samples, adults only, and nymphs only (Table 2), no statistically significant differences were found. Only in two studies were microscopy-based detection techniques (dark-field and phase-contrast) used. In 15 of 78 entries on prevalence in nymphal ticks, pooling was used (usually 10 individuals per pool). Significantly lower mean prevalence rates were found in studies using pooled samples (from which uncorrected minimum infection rates were calculated) than in studies testing individual ticks (6.0% and 15.2%, respectively) (P, <0.001 by a t test with Welch's correction).

TABLE 2.

Mean prevalence rates of B. burgdorferi sensu lato determined by different molecular methods of detection

| Detection method | Prevalence (%)a |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| All ticks | Adults | Nymphs | |

| PCR | 14.0 ± 1.5 (42) | 15.4 ± 1.9 (36) | 12.3 ± 1.5 (29) |

| Nested PCR | 17.3 ± 2.2 (18) | 20.4 ± 3.0 (16) | 14.6 ± 2.1 (13) |

| qPCR | 17.9 ± 1.7 (35) | 21.0 ± 2.3 (29) | 15.4 ± 1.7 (31) |

Values are means ± standard errors of the means (number of records).

Prevalence of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato in ticks according to the year of tick sampling.

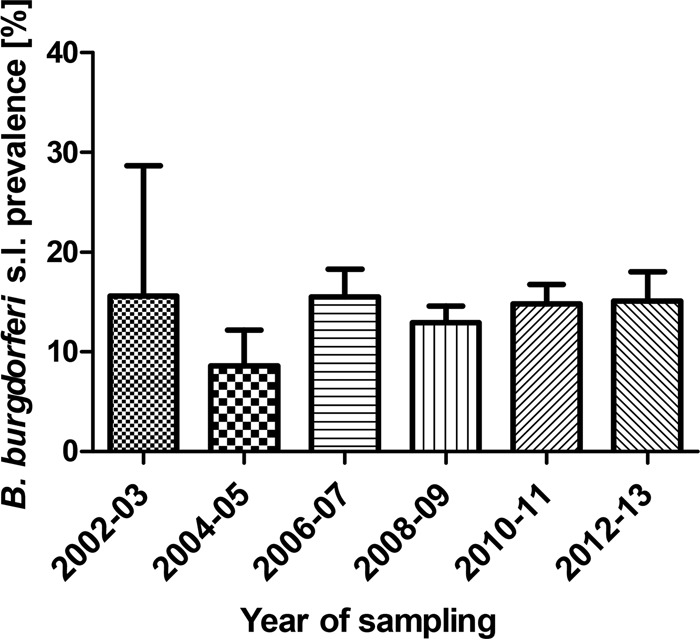

In order to compare the infection rates in all ticks over the years, the data were divided into 2-year cycles (2002–2003 up to 2012–2013) according to the year of tick sampling. Data for 2001 and 2015 consisted only of a single entry each and therefore were not included in the analysis. If the collection period was longer or did not fit exactly into the given 2-year time frame, the data were excluded (resulting in 66 separate entries). Because of big differences in the numbers of entries available for particular years, the 2-year cycles were used in order to get comparable numbers of entries per time period. No trend was observed when the mean prevalence rates in 2-year cycles were analyzed by linear regression, no significant differences were found among the 2-year periods (Fig. 4), and no statistically significant difference was found when the 2002–2007 group (mean prevalences in adults and nymphs, 18.2% and 14.5%, respectively) was compared to the 2008–2014 group (16.7% and 13.1%, respectively).

FIG 4.

Mean prevalences of B. burgdorferi sensu lato in I. ricinus ticks in Europe in 2-year cycles. Each bar represents the mean prevalence reached in a particular 2-year cycle. Error bars, standard errors of the means.

In contrast, the mean B. burgdorferi sensu lato prevalence rate in our whole data set (2002 to 2014 for nymphs and 2001 to 2015 for adults) was statistically significantly lower for adult ticks (14.9%), but significantly higher for nymphal ticks (11.8%), than those determined from the data collected by Rauter and Hartung (21) for 1985 to 2004 (18.6% and 10.1%, respectively) (P, <0.001 by the χ2 test). The numbers of samples analyzed were comparable.

Geographical differences in the prevalence of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato in ticks.

Statistically significant differences in the prevalence of B. burgdorferi sensu lato were observed among individual countries (P, <0.05 by the Kruskal-Wallis test), but no significant differences were found in the paired comparison. Therefore, the data were stratified by area, and countries were merged into bigger regional units based on geographical proximity and environmental/climate similarity. The European regions in which the tick infection rate was calculated are defined as follows: British Isles (England, Scotland, and Wales), Iberian Peninsula (Portugal and Spain), Western Europe (Belgium, France, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands), Scandinavia (Belarus, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, and Norway), Central Europe (Austria, Czech Republic, Germany, Hungary, Poland, Slovakia, and Switzerland), Southern Europe (Italy), and the Balkan Peninsula (Romania, Serbia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina). In each region, at least 3 independent entries were available for all ticks as well as for each of the developmental stages.

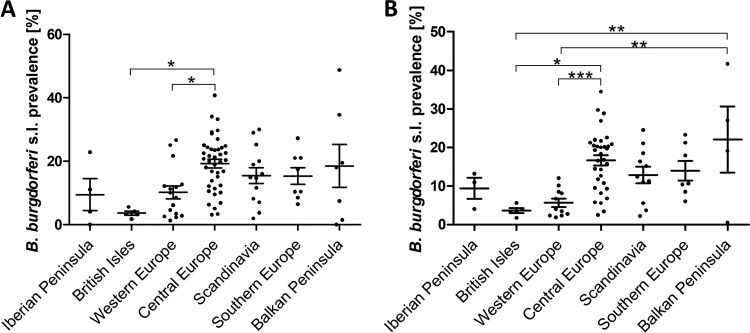

The mean prevalence rates of B. burgdorferi sensu lato in I. ricinus ticks differed among the regions (P, <0.01 by analysis of variance [ANOVA]) (Table 3). The highest prevalence for all ticks was found in Central Europe (19.3%). The lowest prevalence was observed in the British Isles (3.6%). The difference in infection rates between these two regions and that between Central Europe (19.3%) and Western Europe (10.2%) were the only statistically significant differences in paired-region comparisons (P, <0.05 by Bonferroni's multiple-comparison test) (Fig. 5). Similarly, the nymphal infection rate differed significantly among the regions (P, <0.001 by ANOVA). In paired comparisons of prevalence among nymphs, significant differences were found not only between Central Europe (16.7%) and the British Isles (3.6%) and between Central Europe (16.7%) and Western Europe (5.7%) but also between the Balkan Peninsula (22.1%) and the British Isles (3.6%) and between the Balkan Peninsula (22.1%) and Western Europe (5.7%) (P, <0.05 by Bonferroni's multiple-comparison test) (Fig. 5). No significant differences in the infection rate of adult I. ricinus ticks were found among the regions.

TABLE 3.

Mean prevalence rates of B. burgdorferi sensu lato in I. ricinus ticks in defined regions of Europe

| Region | Prevalence (%) of B. burgdorferi

sensu lato in I. ricinus ticksa |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Nymphs | Adults | Total | |

| Iberian Peninsula | 9.4 (2.8) | 11.4 (6.6) | 9.5 (5.0) |

| British Isles | 3.6 (0.6) | 3.2 (1.8) | 3.6 (0.6) |

| Western Europe | 5.7 (1.1) | 14.6 (3.0) | 10.2 (2.0) |

| Central Europe | 16.7 (1.4) | 21.6 (1.9) | 19.3 (1.3) |

| Scandinavia | 12.9 (2.2) | 21.0 (4.0) | 15.5 (2.5) |

| Southern Europe | 14.0 (2.5) | 14.7 (3.4) | 15.3 (2.6) |

| Balkan Peninsula | 22.1 (8.6) | 19.1 (7.0) | 18.5 (6.8) |

Values are means (standard errors of the means).

FIG 5.

Prevalence of B. burgdorferi sensu lato in I. ricinus ticks in defined regions of Europe. Each dot represents a single entry (locality). The middle lines represent the means; error bars, standard errors of the means. Results were compared by ANOVA, followed by Bonferroni's multiple-comparison test. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. (A) Comparison of all ticks; (B) comparison of nymphal I. ricinus ticks.

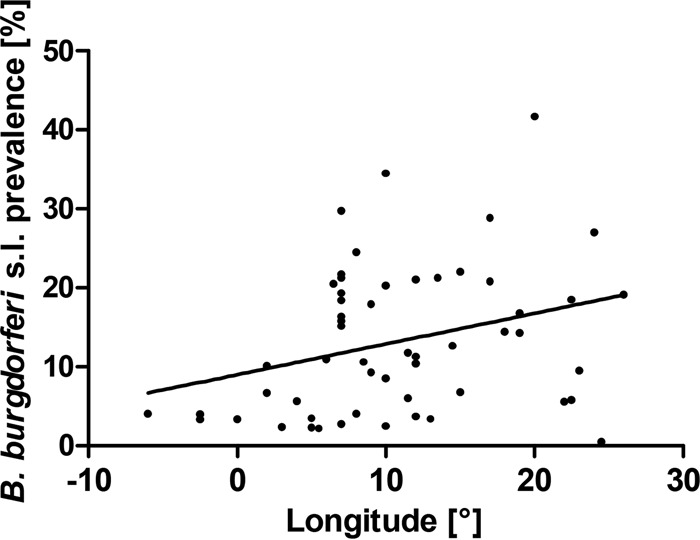

The prevalence rate of B. burgdorferi sensu lato in nymphal ticks rises with increasing longitude (linear regression; R2 = 0.0927; P < 0.05) (Fig. 6). A similar tendency, but one that was not statistically significant, was observed for infection of adult ticks. The relationship between the B. burgdorferi sensu lato prevalence rate and latitude was not found significant for either nymphal, adult, or all ticks. Nevertheless, special attention was paid to the northern distribution limit of I. ricinus, which is reported to be steadily shifting in latitudes above 60°N (25). In our data set, 5 studies contained ticks sampled at localities above this limit (61 to 65°N). Altogether, 5,574 ticks (4,797 nymphs and 777 adults) were analyzed in this subset, reaching an average B. burgdorferi sensu lato prevalence of 15.9% in nymphal ticks and 23.2% in adult ticks, values statistically significantly higher than those in localities south of the limit (13.2% for nymphs and 19.3% for adults) (P, <0.01 by a χ2 test with the Yates correction).

FIG 6.

Regression analysis of the prevalence of B. burgdorferi sensu lato in nymphal I. ricinus ticks in Europe with longitude (linear regression; R2 = 0.0927; P < 0.05). Each dot represents a single entry (locality).

Representation of individual Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato genospecies.

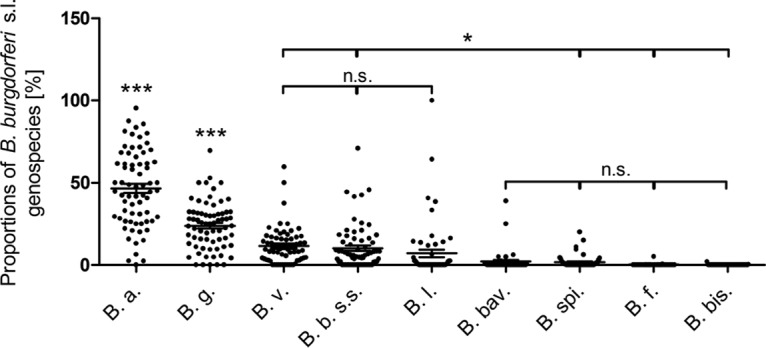

For the analysis of genospecies composition, the proportion of each genospecies was expressed as a percentage of all identified samples of B. burgdorferi sensu lato for each study. The data were extracted from a total of 69 entries. To minimize the impact of sample size per study, the overall proportions were calculated as averages of the percentages from individual papers (not from the sums of numbers). For each genospecies, the proportion was calculated by including only studies that employed a method that could safely identify that particular genospecies.

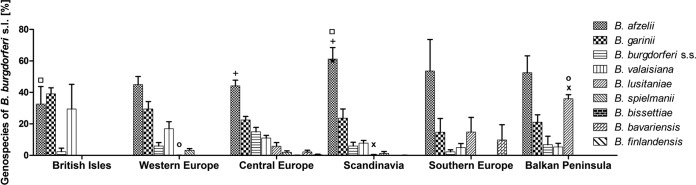

Statistically significant differences in the representation of the nine genospecies analyzed were observed. B. afzelii (46.6%; 69 values) and B. garinii (23.8%; 69 values) were the most frequently detected genospecies (P, <0.001 for differences from all other genospecies and from each other by Bonferroni's multiple-comparison test), followed by B. valaisiana (11.4%; 65 values), B. burgdorferi sensu stricto (10.2%; 68 values), and B. lusitaniae (7.0%; 58 values) (P, <0.05 for differences from all other genospecies but not from each other). B. bavariensis (2.0%; 44 values), B. spielmanii (1.7%; 54 values), B. finlandensis (0.2%; 35 values), and B. bissettiae (0.06%; 51 values), were rarely detected (P, <0.05 for differences from all other genospecies except B. lusitaniae; not significantly different from each other) (Fig. 7).

FIG 7.

Proportions of B. burgdorferi sensu lato genospecies in I. ricinus ticks in Europe. Each dot represents a single entry (locality). The middle lines represent the means; error bars, standard errors of the means. Results were compared by ANOVA, followed by Bonferroni's multiple-comparison test. B. a., B. afzelii; B. g., B. garinii; B. v., B. valaisiana; B. b. s.s., B. burgdorferi sensu stricto; B. l., B. lusitaniae; B. bav., B. bavariensis; B. spi., B. spielmanii; B. f., B. finlandensis; B. bis., B. bissettiae. *, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001; n.s., not statistically significant.

Negative correlations were found by the Spearman rank test between the proportions of B. afzelii and B. garinii (r = −0.46; P < 0.001), B. afzelii and B. burgdorferi sensu stricto (r = −0.37; P < 0.01), B. afzelii and B. valaisiana (r = −0.52; P < 0.001), and B. afzelii and B. lusitaniae (r = −0.29; P < 0.05). The proportions of B. garinii and B. lusitaniae also correlated negatively (r = −0.263; P < 0.05).

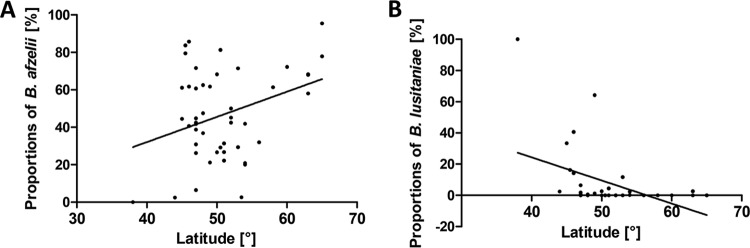

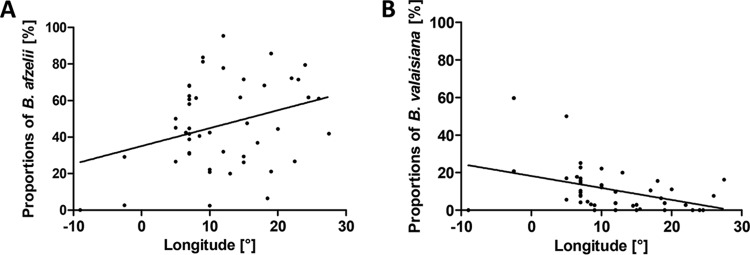

The relationships of the proportional representation of the individual genospecies with latitude and longitude were examined using linear regression. The proportion of B. afzelii among B. burgdorferi sensu lato-infected ticks increases from the south of Europe to the north (r2 = 0.1119; P < 0.05), whereas the prevalence of B. lusitaniae decreases in the same direction (r2 = 0.1949; P < 0.01) (Fig. 8). Similarly, the proportion of B. afzelii increases toward the east (r2 = 0.0994; P < 0.05), whereas the prevalence of B. valaisiana decreases significantly in the same direction (r2 = 0.1633; P < 0.001) (Fig. 9).

FIG 8.

Regression analyses of B. afzelii (A) and B. lusitaniae (B) infection rates in I. ricinus ticks in Europe with latitude.

FIG 9.

Regression analyses of B. afzelii (A) and B. valaisiana (B) infection rates in I. ricinus ticks in Europe with longitude.

The data on the proportional representation of individual genospecies were grouped according to the geographic region of tick sampling (Table 4). The distribution of individual genospecies among different geographic regions was analyzed (Fig. 10). The impact of the region was not found to be statistically significant, whereas the B. burgdorferi sensu lato genospecies and the interaction of region and genospecies were found to contribute statistically significantly to the total variation (P, <0.01 and <0.001, respectively, by two-way ANOVA). Significant differences were found in the representation of B. afzelii between the British Isles and Scandinavia as well as between Central Europe and Scandinavia (P, <0.05 by Bonferroni's multiple-comparison test). The prevalence of B. lusitaniae was statistically significantly different between Western Europe and the Balkan Peninsula as well as between Scandinavia and the Balkan Peninsula (P, <0.05 by Bonferroni's multiple-comparison test). Because there was only a single entry for genospecies composition from the Iberian Peninsula (100% B. lusitaniae), this region was not included in the analysis.

TABLE 4.

Proportional representation of B. burgdorferi sensu lato genospecies in I. ricinus ticks in Europe

| Region | % prevalence of the indicated genospeciesa |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B. afzelii | B. garinii | B. burgdorferi sensu stricto | B. valaisiana | B. lusitaniae | B. spielmanii | B. bissettiae | B. bavariensis | B. finlandensis | |

| Iberian Peninsula | 0 ± 0 (1) | 0 ± 0 (1) | 0 ± 0 (1) | 0 ± 0 (1) | 100 ± 0 (1) | 0 ± 0 (1) | 0 ± 0 (1) | 0 ± 0 (1) | 0 ± 0 (1) |

| British Isles | 33 ± 11 (4) | 39 ± 4 (4) | 2 ± 2 (3) | 30 ± 16 (3) | 0 ± 0 (3) | 0 ± 0 (3) | 0 ± 0 (3) | 0 ± 0 (3) | 0 ± 0 (2) |

| Western Europe | 45 ± 5 (10) | 29 ± 5 (10) | 6 ± 2 (10) | 17 ± 4 (10) | 0.1 ± 0.1 (9) | 3 ± 1 (8) | 0 ± 0 (7) | 0 ± 0 (4) | 0 ± 0 (4) |

| Scandinavia | 61 ± 7 (10) | 24 ± 6 (10) | 6 ± 2 (10) | 8 ± 2 (10) | 0.3 ± 0.3 (9) | 1 ± 1 (9) | 0 ± 0 (9) | 0.1 ± 0.1 (7) | 0 ± 0 (7) |

| Central Europe | 44 ± 4 (34) | 23 ± 2 (34) | 15 ± 3 (34) | 11 ± 2 (31) | 6 ± 2 (29) | 2 ± 1 (27) | 0.1 ± 0.1 (25) | 2 ± 1 (23) | 0.4 ± 0.4 (14) |

| Southern Europe | 54 ± 20 (4) | 15 ± 9 (4) | 2 ± 1 (4) | 5 ± 3 (4) | 15 ± 9 (4) | 0 ± 0 (4) | 0 ± 0 (4) | 10 ± 10 (4) | 0 ± 0 (4) |

| Balkan Peninsula | 52 ± 11 (5) | 21 ± 5 (5) | 7 ± 5 (5) | 5 ± 2 (5) | 36 ± 3 (2) | 0 ± 0 (1) | 0 ± 0 (1) | 0 ± 0 (1) | 0 ± 0 (1) |

Values are means ± standard errors of the means (number of records).

FIG 10.

Proportional representation of B. burgdorferi sensu lato genospecies in I. ricinus ticks in Europe in different geographic regions. Each bar represents the mean proportion of a particular genospecies in a region; error bars, standard errors of the means. Each symbol (◽, o, +, x) indicates a statistically significant difference (P < 0.05) in the proportional representation of a particular genospecies between two different regions, as determined by two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's multiple-comparison test. s.s., sensu stricto.

The presence of the relapsing fever spirochete Borrelia miyamotoi in I. ricinus ticks was reported by several studies (26). In our study, we did not specifically search for the prevalence of B. miyamotoi in I. ricinus ticks, but if this information was present in the screened studies, the value was noted. The prevalence rate of this spirochete reached an average of 1.27%, ranging from 0 to 3.85%. Records of the presence of B. miyamotoi were reported from all regions as defined in this study except the Iberian Peninsula, where no records of B. miyamotoi detection attempts were available in our data set.

DISCUSSION

As vectors of many disease-causing parasites, ticks pose a serious threat to human health and a considerable economic burden to public health systems. I. ricinus, the most common European tick, is the principal vector of B. burgdorferi sensu lato, the agent causing the most prevalent human tick-borne disease in Europe, Lyme borreliosis. A meta-analysis of data was performed with the aim of obtaining an all encompassing picture of B. burgdorferi sensu lato and its genospecies distribution in European I. ricinus ticks.

The prevalence of B. burgdorferi sensu lato spirochetes in ticks has been considered one of the most crucial elements of risk assessment for LB (21). Nevertheless, local prevalence studies have a very limited value in terms of epidemiological risk assesment. In contrast, integration of the data from studies based on similar methodologies allows for the analysis of spatial and temporal variations and trends and may even reveal potential methodological pitfalls in detection or disease diagnostics. This work is a successor to a previous Europe-wide study done by Rauter and Hartung (21), which was based on data collected from 1984 to 2003. We attempted to use the same methodology, where possible, in order to be able to perform direct comparisons. The analysis showed that the overall mean prevalence of B. burgdorferi sensu lato in I. ricinus ticks reached 12.3%. The prevalence in adult ticks (14.9%) was higher than that in nymphal ticks (11.8%), a finding in accordance with data presented by others (21, 27). Since the minimum infection rate was used in case of pooled samples of nymphal ticks (a single positive tick per pool is expected), the calculated values for nymphs may slightly underestimate the real prevalence. Although transovarial transfer of B. burgdorferi sensu lato is considered dubious (28), some studies from our data set reported the infection of larvae with B. burgdorferi sensu lato. An alternative means of infection of larvae may be interrupted feeding. It has been shown previously that ixodid ticks are able to complete feeding on a second host after interruption (29); thus, partially fed ticks may be sampled as seemingly unfed larvae. This finding, together with the recent findings that I. ricinus larvae are able to transmit B. afzelii to laboratory mice (30), suggests the potential role of larvae in spreading human LB (30).

In contrast to earlier data reviews, where microscopic techniques were the main tools for determining Borrelia prevalence (21, 27), the current values were obtained almost exclusively by using PCR-based methods. Microscopic techniques, used as a standard procedure in the past, do not allow one to distinguish between genospecies, and if not used properly, they may lead to an underestimation of Borrelia infection rates (27). On the other hand, the prevalences of LB spirochetes in I. ricinus ticks reported in the past could be also overestimates due to the misidentification of the relapsing fever spirochete B. miyamotoi by microscopy.

The PCR-based techniques are considered the most sensitive (27) and can detect a Borrelia load as low as a single spirochete (31). However, single-cell sensitivity may be superfluous in view of data suggesting that a minimum of 300 spirochetes may be required in order for a host-seeking nymphal tick to be able to transmit infection (32). In our study, we observed no significant differences in the prevalences estimated by the various PCR methods—conventional PCR, nested PCR, and qPCR—although qPCR is generally considered the most sensitive of the three (33). With regard to changes in prevalence over time, no trends in infection rates were observed over the course of 10 years in our study or in the earlier study of Rauter and Hartung (21). On the other hand, direct comparison of our data set to that of the earlier metastudy (21) indicates significant changes in overall prevalence. Numerically, the mean infection rates in all ticks and adults decreased by 1.4% and 3.7%, respectively, whereas the infection rate in nymphs increased by 1.7% relative to the data given by Rauter and Hartung (21). We may hypothesize that this difference between the results of the metastudies could be caused by the recently increased involvement of ungulates (like deer or moose), which are generally considered transmission-incompetent hosts for B. burgdorferi sensu lato (34, 35) but are frequent hosts of nymphal rather than larval I. ricinus ticks (36, 37). An increase in the total abundance of I. ricinus ticks was associated with the abundance of large ungulates previously (15, 25, 38).

As in the study of Rauter and Hartung (21), the correlation of B. burgdorferi sensu lato prevalence in ticks with the tick collection area showed a significant trend, with the rates increasing from the west to the east of Europe. The same effect was seen for nymphal ticks (in contrast to the study of Rauter and Hartung [21]) and adult ticks separately. The west-to-east trend is probably associated with the high prevalence of ticks in Central Europe. Regression analysis of the prevalence rate and latitude was not significant for B. burgdorferi sensu lato in nymphal, adult, or all ticks. Nevertheless, the prevalence rate in ticks sampled near their northern distribution limit reached values significantly higher than those in the rest of Europe. We hypothesize that this might be due to the lower host species diversity available for these newly established I. ricinus populations, making it possible to feed mostly on B. burgdorferi sensu lato transmission-competent hosts.

The prevalence of B. burgdorferi sensu lato in females surpassed the prevalence rate in males, and the difference was statistically significant when paired values were compared. Rauter and Hartung (21) also observed a higher infection rate for females (by 1.8%). Another study demonstrated a relationship between the weights of engorged nymphal ixodid ticks and their resultant sexes, revealing that the mean body weight of engorged nymphs that molted to females was significantly greater than that of nymphs that became males (39). A larger bloodmeal might result directly in a higher probability of infection and might be associated with prolonged feeding, resulting, again, in a higher chance of ingestion of the spirochetes.

Since different genospecies are involved in distinct clinical manifestations, it is important to know accurate numbers for the prevalence of a particular species with regard to risk assessment. The data show that B. afzelii is the most common genospecies, followed by B. garinii and B. valaisiana, findings consistent with data provided earlier. Interestingly, B. burgdorferi sensu stricto is the fourth most common species, despite the described dominant behavior of B. burgdorferi sensu stricto over some other genospecies (40).

Genospecies that were differentiated more recently are likely underrepresented in the data set, even though zero prevalence values were included only if they were generated in studies that used an identification method allowing the differentiation of the particular genospecies. In a number of reviewed studies, only the “major” genospecies were differentiated and the designation “NPD” (not possible to determine) was assigned to the other, “unidentified” genospecies (see Materials and Methods). However, during the analysis of those studies, we occasionally checked the specificity of the primers used and found that more than one genospecies could be detected with a given set of primers (e.g., the primer set distinguished between B. afzelii, B. garinii, and B. burgdorferi sensu stricto but could not distinguish, for instance, between B. burgdorferi sensu stricto and B. bissettiae).

The data showed that B. valaisiana is the third most common genospecies in Europe. Intriguingly, this species is only very rarely associated with human infection (8). It was demonstrated in vitro that B. burgdorferi sensu lato genospecies showed different patterns of resistance or sensitivity to the complement systems of different vertebrates (41). Therefore, higher sensitivity to some of the components of the human immune system might be the reason for efficient clearance of B. valaisiana.

Over recent decades, our planet has gone through an apparent climate change that has resulted, among other trends, in a shift toward milder winters in Europe (42). As a consequence, ticks have spread into higher latitudes (43) and altitudes (44). Interestingly, the data presented here, together with the previously published data (21, 27), covering a period of about 30 years, indicate that the prevalence of B. burgdorferi sensu lato in questing I. ricinus ticks remains reasonably constant since the beginning of investigations into this issue. Therefore, there seems to be no general effect of climate change on the prevalence rates of this pathogen. This hypothesis can also be supported by the outcomes of the analysis on the dependence of Borrelia prevalence on latitude and longitude. In our data set, analysis of the prevalence rate and latitude did not find a significant correlation for B. burgdorferi sensu lato in nymphal, adult, or all ticks (as in the study of Rauter and Hartung [21]), whereas a significant effect of longitude on prevalence was found. In light of these findings, it may also be debatable how much, in terms of resources, should be invested in future studies determining the infection rates in host-seeking ticks if no fundamental change in infection rates has been seen in the past 30 years of apparent climate change.

Monitoring changes in the prevalences of different B. burgdorferi sensu lato genospecies in ticks might produce an important indicator of host adaptation, which, in turn, has been suggested to contribute to differences in pathogenicity in humans (45). Nevertheless, although we have reported statistically significant changes in the overall prevalence of B. burgdorferi sensu lato and relatively high geographical variability, these differences have only a limited effect on the total infection risk compared with differences in total tick abundance. Therefore, we conclude that detailed monitoring of B. burgdorferi sensu lato prevalence is important mainly in areas undergoing current dynamic changes in tick/pathogen distribution (at the latitudinal and altitudinal limits of distribution), whereas in areas with stable vector populations, regular examination of long-term trends, including habitat-specific distribution patterns of vector/pathogen occurrence, seems more reasonable. Concerning the variable pathogenicity of B. burgdorferi sensu lato genospecies, information on genospecies variability may be valuable in risk estimation, especially in areas with large proportions of nonpathogenic/conditionally pathogenic genospecies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A systematic literature search (using the keywords “Borrelia AND prevalence AND Ixodes ricinus” and “Borrelia AND Ixodes”) was carried out on the electronic database PubMed, and reports on the prevalence of B. burgdorferi sensu lato in I. ricinus ticks that were published in English between January 2010 and December 2016 were extracted. Reports identified by the database search (>900) were first assessed for eligibility by their titles and abstracts, followed by an in-depth analysis for relevant data regarding B. burgdorferi sensu lato prevalence in ticks.

Only data on questing nymphs and adults were used. Larvae were not included, since only a few studies included larvae in the prevalence analysis. Publications were not included in the analysis if (i) it was not possible to subtract/exclude the rate of infection with the relapsing fever spirochete (B. miyamotoi), (ii) it was not possible to subtract/exclude data on larvae, (iii) data were incomplete, or serious discrepancies or errors in numbers/calculations were noticed, or (iv) samples were collected earlier than the year 2000. If the number of infected I. ricinus ticks was not given, it was calculated, if possible, based on the reported tick infection rate and the number of ticks examined. Cleaning the data set by removing incomplete, inaccurate, or confusing data resulted in a set of 101 individual entries on B. burgdorferi sensu lato prevalence and 69 entries on B. burgdorferi sensu lato genospecies identification. When the ticks were collected over more years, the study, if possible, was divided into separate entries. When the sampling in a single study was done in several countries, the data were again separated into several entries according to the country of sampling. In some studies, the nymphal ticks were analyzed as pooled samples from multiple individuals. In those cases, the minimum infection rate was calculated for the purpose of our study (on the assumption of a single positive tick per positive pool).

Data regarding the area (country), its global positioning system (GPS) coordinates, if available (range, 38 to 65°N, 9°W to 27.5°E), the year of tick sampling (range, 2001 to 2015), the number of ticks according to developmental stage, gender, infection with B. burgdorferi sensu lato (and B. miyamotoi when available), and specific B. burgdorferi sensu lato genospecies were extracted and documented. GPS coordinates were either stated by the authors or inferred from the description of the sampling site. The coordinates were rounded off to whole degrees. In case of multiple sampling points per entry, the range of coordinates was recorded, and the mean value was calculated. Furthermore, the methods used for B. burgdorferi sensu lato detection and genospecies identification were recorded.

In order to maximize the accuracy of the calculated infection rates of B. burgdorferi sensu lato genospecies, the method used to distinguish between genospecies was inspected and assessed with regard to how many genospecies the particular method could distinguish. If the method was not able to determine certain genospecies, the designation “NPD” (not possible to determine) was assigned to a particular genotype, and it was left out of the calculation. For the calculation of genospecies prevalence, if a tick was multiply infected, each genospecies found was added to the corresponding single-infection category. The proportional representation of genospecies was calculated as a percentage of all successful identifications.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analyses were done using GraphPad Prism, version 5.04 (GraphPad Software, Inc., CA, USA). A paired t test or an unpaired t test (with Welch's correction) was used for the comparison of two groups. To assess the statistical significance of differences among more than two groups, ANOVA with Bonferroni's multiple-comparison post hoc test was used. Nonparametric alternatives (the Mann-Whitney U test, the Kruskal-Wallis test) were used for data lacking normality. Relationships among quantitative variables were examined using linear regression or correlation analysis (the Pearson regression coefficient, the Spearman rank test). The χ2 test was employed for comparing prevalences between two or more groups. P values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant. In scatter plots, points represent individual values, middle lines represent means, and error bars represent standard errors of the means, unless stated otherwise in the figure legend.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by the Technology Agency of the Czech Republic (grant TG02010034), ANTIGONE (grant EU-7FP 278976), and ANTIDotE (grant EU-7FP 602272–2). M.S. was supported by the Grant Agency of the University of South Bohemia (grant 04-026/2015/P). V.H. and D.R. were supported by project LO1218 of the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic under the NPU I program. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication. We declare no competing financial interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Stanek G, Wormser GP, Gray J, Strle F. 2012. Lyme borreliosis. Lancet 379:461–473. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60103-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Margos G, Vollmer SA, Cornet M, Garnier M, Fingerle V, Wilske B, Bormane A, Vitorino L, Collares-Pereira M, Drancourt M, Kurtenbach K. 2009. A new Borrelia species defined by multilocus sequence analysis of housekeeping genes. Appl Environ Microbiol 75:5410–5416. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00116-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strle F, Picken RN, Cheng Y, Cimperman J, Maraspin V, Lotric-Furlan S, Ruzic-Sabljic E, Picken MM. 1997. Clinical findings for patients with Lyme borreliosis caused by Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato with genotypic and phenotypic similarities to strain 25015. Clin Infect Dis 25:273–280. doi: 10.1086/514551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rudenko N, Golovchenko M, Růzek D, Piskunova N, Mallátová N, Grubhoffer L. 2009. Molecular detection of Borrelia bissettii DNA in serum samples from patients in the Czech Republic with suspected borreliosis. FEMS Microbiol Lett 292:274–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2009.01498.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Collares-Pereira M, Couceiro S, Franca I, Kurtenbach K, Schäfer SM, Vitorino L, Gonçalves L, Baptista S, Vieira ML, Cunha C. 2004. First isolation of Borrelia lusitaniae from a human patient. J Clin Microbiol 42:1316–1318. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.3.1316-1318.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.da Franca I, Santos L, Mesquita T, Collares-Pereira M, Baptista S, Vieira L, Viana I, Vale E, Prates C. 2005. Lyme borreliosis in Portugal caused by Borrelia lusitaniae? Clinical report on the first patient with a positive skin isolate. Wien Klin Wochenschr 117:429–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fingerle V, Schulte-Spechtel UC, Ruzic-Sabljic E, Leonhard S, Hofmann H, Weber K, Pfister K, Strle F, Wilske B. 2008. Epidemiological aspects and molecular characterization of Borrelia burgdorferi s.l. from southern Germany with special respect to the new species Borrelia spielmanii sp. nov. Int J Med Microbiol 298:279–290. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diza E, Papa A, Vezyri E, Tsounis S, Milonas I, Antoniadis A. 2004. Borrelia valaisiana in cerebrospinal fluid. Emerg Infect Dis 10:1692–1693. doi: 10.3201/eid1009.030439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stanek G, Reiter M. 2011. The expanding Lyme Borrelia complex—clinical significance of genomic species? Clin Microbiol Infect 17:487–493. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lommano E, Bertaiola L, Dupasquier C, Gern L. 2012. Infections and coinfections of questing Ixodes ricinus ticks by emerging zoonotic pathogens in Western Switzerland. Appl Environ Microbiol 78:4606–4612. doi: 10.1128/AEM.07961-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cotté V, Bonnet S, Cote M, Vayssier-Taussat M. 2010. Prevalence of five pathogenic agents in questing Ixodes ricinus ticks from western France. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 10:723–730. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2009.0066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ornstein K, Berglund J, Nilsson I, Norrby R, Bergström S. 2001. Characterization of Lyme borreliosis isolates from patients with erythema migrans and neuroborreliosis in southern Sweden. J Clin Microbiol 39:1294–1298. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.4.1294-1298.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schorn S, Pfister K, Reulen H, Mahling M, Silaghi C. 2011. Occurrence of Babesia spp., Rickettsia spp. and Bartonella spp. in Ixodes ricinus in Bavarian public parks, Germany. Parasit Vectors 4:135. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-4-135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schwarz A, Hönig V, Vavrušková Z, Grubhoffer L, Balczun C, Albring A, Schaub GA. 2012. Abundance of Ixodes ricinus and prevalence of Borrelia burgdorferi s.l. in the nature reserve Siebengebirge, Germany, in comparison to three former studies from 1978 onwards. Parasit Vectors 5:268. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-5-268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scharlemann JPW, Johnson PJ, Smith AA, Macdonald DW, Randolph SE. 2008. Trends in ixodid tick abundance and distribution in Great Britain. Med Vet Entomol 22:238–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2915.2008.00734.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jaenson TGT, Eisen L, Comstedt P, Mejlon HA, Lindgren E, Bergström S, Olsen B. 2009. Risk indicators for the tick Ixodes ricinus and Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato in Sweden. Med Vet Entomol 23:226–237. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2915.2009.00813.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lindgren E, Tälleklint L, Polfeldt T. 2000. Impact of climatic change on the northern latitude limit and population density of the disease-transmitting European tick Ixodes ricinus. Environ Health Perspect 108:119–123. doi: 10.1289/ehp.00108119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Materna J, Daniel M, Danielová V. 2005. Altitudinal distribution limit of the tick Ixodes ricinus shifted considerably towards higher altitudes in central Europe: results of three years monitoring in the Krkonose Mts. (Czech Republic). Cent Eur J Public Health 13:24–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morán Cadenas F, Rais O, Jouda F, Douet V, Humair P-F, Moret J, Gern L. 2007. Phenology of Ixodes ricinus and infection with Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato along a north- and south-facing altitudinal gradient on Chaumont Mountain, Switzerland. J Med Entomol 44:683–693. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/44.4.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jouda F, Perret J-L, Gern L. 2004. Ixodes ricinus density, and distribution and prevalence of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato infection along an altitudinal gradient. J Med Entomol 41:162–169. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585-41.2.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rauter C, Hartung T. 2005. Prevalence of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato genospecies in Ixodes ricinus ticks in Europe: a metaanalysis. Appl Environ Microbiol 71:7203–7216. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.11.7203-7216.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nazzi F, Martinelli E, Del Fabbro S, Bernardinelli I, Milani N, Iob A, Pischiutti P, Campello C, D'Agaro P. 2010. Ticks and Lyme borreliosis in an alpine area in northeast Italy. Med Vet Entomol 24:220–226. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2915.2010.00877.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tappe J, Jordan D, Janecek E, Fingerle V, Strube C. 2014. Revisited: Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato infections in hard ticks (Ixodes ricinus) in the city of Hanover (Germany). Parasit Vectors 7:441. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-7-441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kalmár Z, Mihalca AD, Dumitrache MO, Gherman CM, Magdaş C, Mircean V, Oltean M, Domşa C, Matei IA, Mărcuţan DI, Sándor AD, D'Amico G, Paştiu A, Györke A, Gavrea R, Marosi B, Ionică A, Burkhardt E, Toriay H, Cozma V. 2013. Geographical distribution and prevalence of Borrelia burgdorferi genospecies in questing Ixodes ricinus from Romania: a countrywide study. Ticks Tick-Borne Dis 4:403–408. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2013.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jaenson TGT, Jaenson DGE, Eisen L, Petersson E, Lindgren E. 2012. Changes in the geographical distribution and abundance of the tick Ixodes ricinus during the past 30 years in Sweden. Parasit Vectors 5:8. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-5-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kjelland V, Rollum R, Korslund L, Slettan A, Tveitnes D. 2015. Borrelia miyamotoi is widespread in Ixodes ricinus ticks in southern Norway. Ticks Tick-Borne Dis 6:516–521. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2015.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hubálek Z, Halouzka J. 1998. Prevalence rates of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato in host-seeking Ixodes ricinus ticks in Europe. Parasitol Res 84:167–172. doi: 10.1007/s004360050378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rollend L, Fish D, Childs JE. 2013. Transovarial transmission of Borrelia spirochetes by Ixodes scapularis: a summary of the literature and recent observations. Ticks Tick-Borne Dis 4:46–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2012.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang H, Henbest PJ, Nuttall PA. 1999. Successful interrupted feeding of adult Rhipicephalus appendiculatus (Ixodidae) is accompanied by reprogramming of salivary gland protein expression. Parasitology 119(Part 2):143–149. doi: 10.1017/S0031182099004540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van Duijvendijk G, Coipan C, Wagemakers A, Fonville M, Ersöz J, Oei A, Földvári G, Hovius J, Takken W, Sprong H. 2016. Larvae of Ixodes ricinus transmit Borrelia afzelii and B. miyamotoi to vertebrate hosts. Parasit Vectors 9:97. doi: 10.1186/s13071-016-1389-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilhelmsson P, Lindblom P, Fryland L, Ernerudh J, Forsberg P, Lindgren P-E. 2013. Prevalence, diversity, and load of Borrelia species in ticks that have fed on humans in regions of Sweden and Åland Islands, Finland with different Lyme borreliosis incidences. PLoS One 8:e81433. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang G, Liveris D, Brei B, Wu H, Falco RC, Fish D, Schwartz I. 2003. Real-time PCR for simultaneous detection and quantification of Borrelia burgdorferi in field-collected Ixodes scapularis ticks from the northeastern United States. Appl Environ Microbiol 69:4561–4565. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.8.4561-4565.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gooskens J, Templeton KE, Claas EC, van Dam AP. 2006. Evaluation of an internally controlled real-time PCR targeting the ospA gene for detection of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato DNA in cerebrospinal fluid. Clin Microbiol Infect 12:894–900. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2006.01509.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kjelland V, Ytrehus B, Stuen S, Skarpaas T, Slettan A. 2011. Prevalence of Borrelia burgdorferi in Ixodes ricinus ticks collected from moose (Alces alces) and roe deer (Capreolus capreolus) in southern Norway. Ticks Tick-Borne Dis 2:99–103. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tälleklint L, Jaenson TG. 1994. Transmission of Borrelia burgdorferi s.l. from mammal reservoirs to the primary vector of Lyme borreliosis, Ixodes ricinus (Acari: Ixodidae), in Sweden. J Med Entomol 31:880–886. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/31.6.880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kiffner C, Lödige C, Alings M, Vor T, Rühe F. 2010. Abundance estimation of Ixodes ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) on roe deer (Capreolus capreolus). Exp Appl Acarol 52:73–84. doi: 10.1007/s10493-010-9341-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vor T, Kiffner C, Hagedorn P, Niedrig M, Rühe F. 2010. Tick burden on European roe deer (Capreolus capreolus). Exp Appl Acarol 51:405–417. doi: 10.1007/s10493-010-9337-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Medlock JM, Hansford KM, Bormane A, Derdakova M, Estrada-Peña A, George J-C, Golovljova I, Jaenson TGT, Jensen J-K, Jensen PM, Kazimirova M, Oteo JA, Papa A, Pfister K, Plantard O, Randolph SE, Rizzoli A, Santos-Silva MM, Sprong H, Vial L, Hendrickx G, Zeller H, Van Bortel W. 2013. Driving forces for changes in geographical distribution of Ixodes ricinus ticks in Europe. Parasit Vectors 6:1. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-6-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hu R, Rowley WA. 2000. Relationship between weights of the engorged nymphal stage and resultant sexes in Ixodes scapularis and Dermacentor variabilis (Acari: Ixodidae) ticks. J Med Entomol 37:198–200. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585-37.1.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hovius JWR, Li X, Ramamoorthi N, van Dam AP, Barthold SW, van der Poll T, Speelman P, Fikrig E. 2007. Coinfection with Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto and Borrelia garinii alters the course of murine Lyme borreliosis. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 49:224–234. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2006.00177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kurtenbach K, De Michelis S, Etti S, Schäfer SM, Sewell H-S, Brade V, Kraiczy P. 2002. Host association of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato—the key role of host complement. Trends Microbiol 10:74–79. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(01)02298-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Semenza JC, Menne B. 2009. Climate change and infectious diseases in Europe. Lancet Infect Dis 9:365–375. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70104-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tälleklint L, Jaenson TG. 1998. Increasing geographical distribution and density of Ixodes ricinus (Acari: Ixodidae) in central and northern Sweden. J Med Entomol 35:521–526. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/35.4.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Danielová V, Rudenko N, Daniel M, Holubová J, Materna J, Golovchenko M, Schwarzová L. 2006. Extension of Ixodes ricinus ticks and agents of tick-borne diseases to mountain areas in the Czech Republic. Int J Med Microbiol 296(Suppl 40):S48–S53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mechai S, Margos G, Feil EJ, Barairo N, Lindsay LR, Michel P, Ogden NH. 2016. Evidence for host-genotype associations of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto. PLoS One 11:e0149345. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0149345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sonnleitner ST, Margos G, Wex F, Simeoni J, Zelger R, Schmutzhard E, Lass-Flörl C, Walder G. 2015. Human seroprevalence against Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato in two comparable regions of the eastern Alps is not correlated to vector infection rates. Ticks Tick-Borne Dis 6:221–227. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2014.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Glatz M, Müllegger RR, Maurer F, Fingerle V, Achermann Y, Wilske B, Bloemberg GV. 2014. Detection of Candidatus Neoehrlichia mikurensis, Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato genospecies and Anaplasma phagocytophilum in a tick population from Austria. Ticks Tick-Borne Dis 5:139–144. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2013.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Glatz M, Muellegger RR, Hizo-Teufel C, Fingerle V. 2014. Low prevalence of Borrelia bavariensis in Ixodes ricinus ticks in southeastern Austria. Ticks Tick-Borne Dis 5:649–650. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2014.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Reye AL, Hübschen JM, Sausy A, Muller CP. 2010. Prevalence and seasonality of tick-borne pathogens in questing Ixodes ricinus ticks from Luxembourg. Appl Environ Microbiol 76:2923–2931. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03061-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Reye AL, Stegniy V, Mishaeva NP, Velhin S, Hübschen JM, Ignatyev G, Muller CP. 2013. Prevalence of tick-borne pathogens in Ixodes ricinus and Dermacentor reticulatus ticks from different geographical locations in Belarus. PLoS One 8:e54476. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Michelet L, Delannoy S, Devillers E, Umhang G, Aspan A, Juremalm M, Chirico J, van der Wal FJ, Sprong H, Boye Pihl TP, Klitgaard K, Bødker R, Fach P, Moutailler S. 2014. High-throughput screening of tick-borne pathogens in Europe. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 4:103. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2014.00103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pacilly FCA, Benning ME, Jacobs F, Leidekker J, Sprong H, Van Wieren SE, Takken W. 2014. Blood feeding on large grazers affects the transmission of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato by Ixodes ricinus. Ticks Tick-Borne Dis 5:810–817. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2014.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Coipan EC, Jahfari S, Fonville M, Maassen CB, van der Giessen J, Takken W, Takumi K, Sprong H. 2013. Spatiotemporal dynamics of emerging pathogens in questing Ixodes ricinus. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 3:36. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2013.00036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gassner F, Takken W, Plas CL, Kastelein P, Hoetmer AJ, Holdinga M, van Overbeek LS. 2013. Rodent species as natural reservoirs of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato in different habitats of Ixodes ricinus in The Netherlands. Ticks Tick-Borne Dis 4:452–458. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2012.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kesteman T, Rossi C, Bastien P, Brouillard J, Avesani V, Olive N, Martin P, Delmée M. 2010. Prevalence and genetic heterogeneity of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato in Ixodes ticks in Belgium. Acta Clin Belg 65:319–322. doi: 10.1179/acb.2010.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tveten A-K. 2013. Prevalence of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto, Borrelia afzelii, Borrelia garinii, and Borrelia valaisiana in Ixodes ricinus ticks from the northwest of Norway. Scand J Infect Dis 45:681–687. doi: 10.3109/00365548.2013.799288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mysterud A, Easterday WR, Qviller L, Viljugrein H, Ytrehus B. 2013. Spatial and seasonal variation in the prevalence of Anaplasma phagocytophilum and Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato in questing Ixodes ricinus ticks in Norway. Parasit Vectors 6:187. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-6-187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Soleng A, Kjelland V. 2013. Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato and Anaplasma phagocytophilum in Ixodes ricinus ticks in Brønnøysund in northern Norway. Ticks Tick-Borne Dis 4:218–221. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2012.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kjelland V, Stuen S, Skarpaas T, Slettan A. 2010. Prevalence and genotypes of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato infection in Ixodes ricinus ticks in southern Norway. Scand J Infect Dis 42:579–585. doi: 10.3109/00365541003716526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hvidsten D, Stordal F, Lager M, Rognerud B, Kristiansen B-E, Matussek A, Gray J, Stuen S. 2015. Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato-infected Ixodes ricinus collected from vegetation near the Arctic Circle. Ticks Tick-Borne Dis 6:768–773. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2015.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Quarsten H, Skarpaas T, Fajs L, Noraas S, Kjelland V. 2015. Tick-borne bacteria in Ixodes ricinus collected in southern Norway evaluated by a commercial kit and established real-time PCR protocols. Ticks Tick-Borne Dis 6:538–544. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2015.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hodžić A, Fuehrer H-P, Duscher GG. 22 January 2016 First molecular evidence of zoonotic bacteria in ticks in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Transbound Emerg Dis doi: 10.1111/tbed.12473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Skotarczak B, Wodecka B, Rymaszewska A, Adamska M. 2016. Molecular evidence for bacterial pathogens in Ixodes ricinus ticks infesting Shetland ponies. Exp Appl Acarol 69:179–189. doi: 10.1007/s10493-016-0027-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wójcik-Fatla A, Zając V, Sawczyn A, Sroka J, Cisak E, Dutkiewicz J. 2016. Infections and mixed infections with the selected species of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato complex in Ixodes ricinus ticks collected in eastern Poland: a significant increase in the course of 5 years. Exp Appl Acarol 68:197–212. doi: 10.1007/s10493-015-9990-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Król N, Kiewra D, Szymanowski M, Lonc E. 2015. The role of domestic dogs and cats in the zoonotic cycles of ticks and pathogens. Preliminary studies in the Wrocław Agglomeration (SW Poland). Vet Parasitol 214:208–212. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2015.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Strzelczyk JK, Gaździcka J, Cuber P, Asman M, Trapp G, Gołąbek K, Zalewska-Ziob M, Nowak-Chmura M, Siuda K, Wiczkowski A, Solarz K. 2015. Prevalence of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato in Ixodes ricinus ticks collected from southern Poland. Acta Parasitol 60:666–674. doi: 10.1515/ap-2015-0095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sytykiewicz H, Karbowiak G, Chorostowska-Wynimko J, Szpechciński A, Supergan-Marwicz M, Horbowicz M, Szwed M, Czerniewicz P, Sprawka I. 2015. Coexistence of Borrelia burgdorferi s.l. genospecies within Ixodes ricinus ticks from central and eastern Poland. Acta Parasitol 60:654–661. doi: 10.1515/ap-2015-0093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kiewra D, Stańczak J, Richter M. 2014. Ixodes ricinus ticks (Acari, Ixodidae) as a vector of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato and Borrelia miyamotoi in Lower Silesia, Poland—preliminary study. Ticks Tick-Borne Dis 5:892–897. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2014.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dunaj J, Zajkowska JM, Kondrusik M, Gern L, Rais O, Moniuszko A, Pancewicz S, Świerzbińska R. 2014. Borrelia burgdorferi genospecies detection by RLB hybridization in Ixodes ricinus ticks from different sites of North-Eastern Poland. Ann Agric Environ Med 21:239–243. doi: 10.5604/1232-1966.1108583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cisak E, Wójcik-Fatla A, Zając V, Dutkiewicz J. 2014. Prevalence of tick-borne pathogens at various workplaces in forest exploitation environment. Med Pr 65:575–581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Asman M, Nowak M, Cuber P, Strzelczyk J, Szilman E, Szilman P, Trapp G, Siuda K, Solarz K, Wiczkowski A. 2013. The risk of exposure to Anaplasma phagocytophilum, Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato, Babesia sp. and co-infections in Ixodes ricinus ticks on the territory of Niepołomice forest (southern Poland). Ann Parasitol 59:13–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wójcik-Fatla A, Zając V, Cisak E, Sroka J, Sawczyn A, Dutkiewicz J. 2012. Leptospirosis as a tick-borne disease? Detection of Leptospira spp. in Ixodes ricinus ticks in eastern Poland. Ann Agric Environ Med 19:656–659. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cisak E, Wójcik-Fatla A, Zając V, Sroka J, Dutkiewicz J. 2012. Risk of Lyme disease at various sites and workplaces of forestry workers in eastern Poland. Ann Agric Environ Med 19:465–468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sytykiewicz H, Karbowiak G, Werszko J, Czerniewicz P, Sprawka I, Mitrus J. 2012. Molecular screening for Bartonella henselae and Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato co-existence within Ixodes ricinus populations in central and eastern parts of Poland. Ann Agric Environ Med 19:451–456. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Richter D, Matuschka F-R. 2012. “Candidatus Neoehrlichia mikurensis,” Anaplasma phagocytophilum, and Lyme disease spirochetes in questing European vector ticks and in feeding ticks removed from people. J Clin Microbiol 50:943–947. doi: 10.1128/JCM.05802-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hönig V, Svec P, Halas P, Vavruskova Z, Tykalova H, Kilian P, Vetiskova V, Dornakova V, Sterbova J, Simonova Z, Erhart J, Sterba J, Golovchenko M, Rudenko N, Grubhoffer L. 2015. Ticks and tick-borne pathogens in South Bohemia (Czech Republic)—spatial variability in Ixodes ricinus abundance, Borrelia burgdorferi and tick-borne encephalitis virus prevalence. Ticks Tick-Borne Dis 6:559–567. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2015.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Daniel M, Rudenko N, Golovchenko M, Danielová V, Fialová A, Kříž B, Malý M. 2016. The occurrence of Ixodes ricinus ticks and important tick-borne pathogens in areas with high tick-borne encephalitis prevalence in different altitudinal levels of the Czech Republic. Part II. Ixodes ricinus ticks and genospecies of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato complex. Epidemiol Mikrobiol Imunol 65:182–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Venclíková K, Betášová L, Sikutová S, Jedličková P, Hubálek Z, Rudolf I. 2014. Human pathogenic borreliae in Ixodes ricinus ticks in natural and urban ecosystem (Czech Republic). Acta Parasitol 59:717–720. doi: 10.2478/s11686-014-0296-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Nunes M, Parreira R, Lopes N, Maia C, Carreira T, Sousa C, Faria S, Campino L, Vieira ML. 2015. Molecular identification of Borrelia miyamotoi in Ixodes ricinus from Portugal. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 15:515–517. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2014.1765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Milhano N, de Carvalho IL, Alves AS, Arroube S, Soares J, Rodriguez P, Carolino M, Núncio MS, Piesman J, de Sousa R. 2010. Coinfections of Rickettsia slovaca and Rickettsia helvetica with Borrelia lusitaniae in ticks collected in a Safari Park, Portugal. Ticks Tick-Borne Dis 1:172–177. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2010.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Coipan EC, Vladimirescu AF. 2011. Ixodes ricinus ticks (Acari: Ixodidae): vectors for Lyme disease spirochetes in Romania. Exp Appl Acarol 54:293–300. doi: 10.1007/s10493-011-9438-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Coipan EC, Vladimirescu AF. 2010. First report of Lyme disease spirochetes in ticks from Romania (Sibiu County). Exp Appl Acarol 52:193–197. doi: 10.1007/s10493-010-9353-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Geller J, Nazarova L, Katargina O, Golovljova I. 2013. Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato prevalence in tick populations in Estonia. Parasit Vectors 6:202. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-6-202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Tomanović S, Radulović Z, Masuzawa T, Milutinović M. 2010. Coexistence of emerging bacterial pathogens in Ixodes ricinus ticks in Serbia. Parasite (Paris, Fr) 17:211–217. doi: 10.1051/parasite/2010173211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Tomanović S, Chochlakis D, Radulović Z, Milutinović M, Cakić S, Mihaljica D, Tselentis Y, Psaroulaki A. 2013. Analysis of pathogen co-occurrence in host-seeking adult hard ticks from Serbia. Exp Appl Acarol 59:367–376. doi: 10.1007/s10493-012-9597-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Potkonjak A, Kleinerman G, Gutiérrez R, Savić S, Vračar V, Nachum-Biala Y, Jurišić A, Rojas A, Petrović A, Ivanović I, Harrus S, Baneth G. 2016. Occurrence of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato in Ixodes ricinus ticks with first identification of Borrelia miyamotoi in Vojvodina, Serbia. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 16:631–635. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2016.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sormunen JJ, Penttinen R, Klemola T, Hänninen J, Vuorinen I, Laaksonen M, Sääksjärvi IE, Ruohomäki K, Vesterinen EJ. 2016. Tick-borne bacterial pathogens in southwestern Finland. Parasit Vectors 9:168. doi: 10.1186/s13071-016-1449-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sormunen JJ, Klemola T, Vesterinen EJ, Vuorinen I, Hytönen J, Hänninen J, Ruohomäki K, Sääksjärvi IE, Tonteri E, Penttinen R. 2016. Assessing the abundance, seasonal questing activity, and Borrelia and tick-borne encephalitis virus (TBEV) prevalence of Ixodes ricinus ticks in a Lyme borreliosis endemic area in Southwest Finland. Ticks Tick-Borne Dis 7:208–215. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2015.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Pangrácová L, Derdáková M, Pekárik L, Hviščová I, Víchová B, Stanko M, Hlavatá H, Pet'ko B. 2013. Ixodes ricinus abundance and its infection with the tick-borne pathogens in urban and suburban areas of Eastern Slovakia. Parasit Vectors 6:238. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-6-238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Subramanian G, Sekeyova Z, Raoult D, Mediannikov O. 2012. Multiple tick-associated bacteria in Ixodes ricinus from Slovakia. Ticks Tick-Borne Dis 3:406–410. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2012.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Taragel'ová VR, Mahríková L, Selyemová D, Václav R, Derdáková M. 2016. Natural foci of Borrelia lusitaniae in a mountain region of Central Europe. Ticks Tick-Borne Dis 7:350–356. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2015.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Cosson J-F, Michelet L, Chotte J, Le Naour E, Cote M, Devillers E, Poulle M-L, Huet D, Galan M, Geller J, Moutailler S, Vayssier-Taussat M. 2014. Genetic characterization of the human relapsing fever spirochete Borrelia miyamotoi in vectors and animal reservoirs of Lyme disease spirochetes in France. Parasit Vectors 7:233. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-7-233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Reis C, Cote M, Paul REL, Bonnet S. 2011. Questing ticks in suburban forest are infected by at least six tick-borne pathogens. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 11:907–916. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2010.0103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Halos L, Bord S, Cotté V, Gasqui P, Abrial D, Barnouin J, Boulouis H-J, Vayssier-Taussat M, Vourc'h G. 2010. Ecological factors characterizing the prevalence of bacterial tick-borne pathogens in Ixodes ricinus ticks in pastures and woodlands. Appl Environ Microbiol 76:4413–4420. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00610-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Dietrich F, Schmidgen T, Maggi RG, Richter D, Matuschka F-R, Vonthein R, Breitschwerdt EB, Kempf VAJ. 2010. Prevalence of Bartonella henselae and Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato DNA in ixodes ricinus ticks in Europe. Appl Environ Microbiol 76:1395–1398. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02788-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Bonnet S, de la Fuente J, Nicollet P, Liu X, Madani N, Blanchard B, Maingourd C, Alongi A, Torina A, Fernández de Mera IG, Vicente J, George J-C, Vayssier-Taussat M, Joncour G. 2013. Prevalence of tick-borne pathogens in adult Dermacentor spp. ticks from nine collection sites in France. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 13:226–236. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2011.0933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Moutailler S, Valiente Moro C, Vaumourin E, Michelet L, Tran FH, Devillers E, Cosson J-F, Gasqui P, Van VT, Mavingui P, Vourc'h G, Vayssier-Taussat M. 2016. Co-infection of ticks: the rule rather than the exception. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 10:e0004539. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Vourc'h G, Abrial D, Bord S, Jacquot M, Masséglia S, Poux V, Pisanu B, Bailly X, Chapuis J-L. 2016. Mapping human risk of infection with Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato, the agent of Lyme borreliosis, in a periurban forest in France. Ticks Tick-Borne Dis 7:644–652. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2016.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ruiz-Fons F, Fernández-de-Mera IG, Acevedo P, Gortázar C, de la Fuente J. 2012. Factors driving the abundance of Ixodes ricinus ticks and the prevalence of zoonotic I. ricinus-borne pathogens in natural foci. Appl Environ Microbiol 78:2669–2676. doi: 10.1128/AEM.06564-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.May K, Jordan D, Fingerle V, Strube C. 2015. Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato and co-infections with Anaplasma phagocytophilum and Rickettsia spp. in Ixodes ricinus in Hamburg, Germany. Med Vet Entomol 29:425–429. doi: 10.1111/mve.12125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Bingsohn L, Beckert A, Zehner R, Kuch U, Oehme R, Kraiczy P, Amendt J. 2013. Prevalences of tick-borne encephalitis virus and Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato in Ixodes ricinus populations of the Rhine-Main region, Germany. Ticks Tick-Borne Dis 4:207–213. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2012.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Richter D, Schröder B, Hartmann NK, Matuschka F-R. 2013. Spatial stratification of various Lyme disease spirochetes in a Central European site. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 83:738–744. doi: 10.1111/1574-6941.12029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Richter D, Matuschka F-R. 2011. Differential risk for Lyme disease along hiking trail, Germany. Emerg Infect Dis 17:1704–1706. doi: 10.3201/eid1709.101523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Franke J, Hildebrandt A, Meier F, Straube E, Dorn W. 2011. Prevalence of Lyme disease agents and several emerging pathogens in questing ticks from the German Baltic coast. J Med Entomol 48:441–444. doi: 10.1603/ME10182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Franke J, Fritzsch J, Tomaso H, Straube E, Dorn W, Hildebrandt A. 2010. Coexistence of pathogens in host-seeking and feeding ticks within a single natural habitat in Central Germany. Appl Environ Microbiol 76:6829–6836. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01630-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Hildebrandt A, Pauliks K, Sachse S, Straube E. 2010. Coexistence of Borrelia spp. and Babesia spp. in Ixodes ricinus ticks in Middle Germany. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 10:831–837. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2009.0202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Herrmann C, Gern L. 2012. Do the level of energy reserves, hydration status and Borrelia infection influence walking by Ixodes ricinus (Acari: Ixodidae) ticks? Parasitology 139:330–337. doi: 10.1017/S0031182011002095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Herrmann C, Gern L. 2013. Survival of Ixodes ricinus (Acari: Ixodidae) nymphs under cold conditions is negatively influenced by frequent temperature variations. Ticks Tick-Borne Dis 4:445–451. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2013.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Pérez D, Kneubühler Y, Rais O, Gern L. 2012. Seasonality of Ixodes ricinus ticks on vegetation and on rodents and Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato genospecies diversity in two Lyme borreliosis-endemic areas in Switzerland. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 12:633–644. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2011.0763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Gern L, Douet V, López Z, Rais O, Cadenas FM. 2010. Diversity of Borrelia genospecies in Ixodes ricinus ticks in a Lyme borreliosis endemic area in Switzerland identified by using new probes for reverse line blotting. Ticks Tick-Borne Dis 1:23–29. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Hornok S, Meli ML, Gönczi E, Halász E, Takács N, Farkas R, Hofmann-Lehmann R. 2014. Occurrence of ticks and prevalence of Anaplasma phagocytophilum and Borrelia burgdorferi s.l. in three types of urban biotopes: forests, parks and cemeteries. Ticks Tick-Borne Dis 5:785–789. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2014.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Szekeres S, Coipan EC, Rigó K, Majoros G, Jahfari S, Sprong H, Földvári G. 2015. Eco-epidemiology of Borrelia miyamotoi and Lyme borreliosis spirochetes in a popular hunting and recreational forest area in Hungary. Parasit Vectors 8:309. doi: 10.1186/s13071-015-0922-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Nelson C, Banks S, Jeffries CL, Walker T, Logan JG. 2015. Tick abundances in South London parks and the potential risk for Lyme borreliosis to the general public. Med Vet Entomol 29:448–452. doi: 10.1111/mve.12137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Hansford KM, Fonville M, Jahfari S, Sprong H, Medlock JM. 2015. Borrelia miyamotoi in host-seeking Ixodes ricinus ticks in England. Epidemiol Infect 143:1079–1087. doi: 10.1017/S0950268814001691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Bettridge J, Renard M, Zhao F, Bown KJ, Birtles RJ. 2013. Distribution of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato in Ixodes ricinus populations across central Britain. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 13:139–146. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2012.1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Millins C, Gilbert L, Johnson P, James M, Kilbride E, Birtles R, Biek R. 2016. Heterogeneity in the abundance and distribution of Ixodes ricinus and Borrelia burgdorferi (sensu lato) in Scotland: implications for risk prediction. Parasit Vectors 9:595. doi: 10.1186/s13071-016-1875-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.James MC, Gilbert L, Bowman AS, Forbes KJ. 2014. The heterogeneity, distribution, and environmental associations of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato, the agent of Lyme borreliosis, in Scotland. Front Public Health 2:129. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2014.00129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.James MC, Bowman AS, Forbes KJ, Lewis F, McLeod JE, Gilbert L. 2013. Environmental determinants of Ixodes ricinus ticks and the incidence of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato, the agent of Lyme borreliosis, in Scotland. Parasitology 140:237–246. doi: 10.1017/S003118201200145X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Ragagli C, Mannelli A, Ambrogi C, Bisanzio D, Ceballos LA, Grego E, Martello E, Selmi M, Tomassone L. 2016. Presence of host-seeking Ixodes ricinus and their infection with Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato in the Northern Apennines, Italy. Exp Appl Acarol 69:167–178. doi: 10.1007/s10493-016-0030-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Aureli S, Galuppi R, Ostanello F, Foley JE, Bonoli C, Rejmanek D, Rocchi G, Orlandi E, Tampieri MP. 2015. Abundance of questing ticks and molecular evidence for pathogens in ticks in three parks of Emilia-Romagna region of Northern Italy. Ann Agric Environ Med 22:459–466. doi: 10.5604/12321966.1167714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Mancini F, Di Luca M, Toma L, Vescio F, Bianchi R, Khoury C, Marini L, Rezza G, Ciervo A. 2014. Prevalence of tick-borne pathogens in an urban park in Rome, Italy. Ann Agric Environ Med 21:723–727. doi: 10.5604/12321966.1129922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Pintore MD, Ceballos L, Iulini B, Tomassone L, Pautasso A, Corbellini D, Rizzo F, Mandola ML, Bardelli M, Peletto S, Acutis PL, Mannelli A, Casalone C. 2015. Detection of invasive Borrelia burgdorferi strains in north-eastern Piedmont, Italy. Zoonoses Public Health 62:365–374. doi: 10.1111/zph.12156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Corrain R, Drigo M, Fenati M, Menandro ML, Mondin A, Pasotto D, Martini M. 2012. Study on ticks and tick-borne zoonoses in public parks in Italy. Zoonoses Public Health 59:468–476. doi: 10.1111/j.1863-2378.2012.01490.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Pistone D, Pajoro M, Fabbi M, Vicari N, Marone P, Genchi C, Novati S, Sassera D, Epis S, Bandi C. 2010. Lyme borreliosis, Po River Valley, Italy. Emerg Infect Dis 16:1289–1291. doi: 10.3201/eid1608.100152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Herrmann C, Voordouw MJ, Gern L. 2013. Ixodes ricinus ticks infected with the causative agent of Lyme disease, Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato, have higher energy reserves. Int J Parasitol 43:477–483. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2012.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]