Abstract

Retinitis pigmentosa is a group of genetically transmitted disorders affecting 1 in 3000–8000 individual people worldwide ultimately affecting the quality of life. Retinitis pigmentosa is characterized as a heterogeneous genetic disorder which leads by progressive devolution of the retina leading to a progressive visual loss. It can occur in syndromic (with Usher syndrome and Bardet-Biedl syndrome) as well as non-syndromic nature. The mode of inheritance can be X-linked, autosomal dominant or autosomal recessive manner. To date 58 genes have been reported to associate with retinitis pigmentosa most of them are either expressed in photoreceptors or the retinal pigment epithelium. This review focuses on the disease mechanisms and genetics of retinitis pigmentosa. As retinitis pigmentosa is tremendously heterogeneous disorder expressing a multiplicity of mutations; different variations in the same gene might induce different disorders. In recent years, latest technologies including whole-exome sequencing contributing effectively to uncover the hidden genesis of retinitis pigmentosa by reporting new genetic mutations. In future, these advancements will help in better understanding the genotype–phenotype correlations of disease and likely to develop new therapies.

Keywords: Retinitis pigments, Autosomal dominant, Autosomal recessive, Whole-exome sequencing, X-linked

Introduction

More than 240 genetic mutations are involved in inherited retinal dystrophies which are an overlapping group of genetic and clinical heterogeneous disorders (El-Asrag et al. 2015). Retinitis pigmentosa is a heterogeneous genetic disorder which is characterized by progressive devolution of the retina, affecting 1 in 3000–8000 people worldwide (Hamel 2006; Hartong et al. 2006); starting in the mid-fringe and advances towards the macula lutea and fovea. Symptoms include diminishing visual fields that lead to Kalnienk vision, ultimately leading to legal blindness or complete blindness (Hartong et al. 2006). Retinitis pigmentosa is also depicted as rod-cone dystrophy because of primarily degeneration of photoreceptor rods along with secondary degeneration of cones; eventually causing complete blindness. Photoreceptor rods are appeared to be more affected than cones. The rod-cone sequences elaborate why the night blindness is initially appeared in patients and in later life patients suffer from visual disability in periodic conditions (Hamel 2006). Diseased photoreceptors face apoptosis (Marigo 2007), which is resulted in reducing the thickness of the outer nuclear layer in the retina, and retinal pigments with abnormal structural changes are deposited in the fundus.

Clinical phenotypes may include, (1) abnormal absence of a-waves and b-waves in electroretinogram results, (2) reduced field vision. Symptoms appear in early teenage but severe visual impairment occurs by 40–50 years of age (Hamel 2006). In a multicentre study, 999 patients (age 45 or older) were evaluated for visual acuity, carrying multiple genetic subtypes of retinitis pigmentosa revealed that 69% patients had visual acuity of 20/70 or better, 52% of 20/40 or better, 25% of 20/200 or worse and 0.5% had no light sensing in both eyes (Grover et al. 1999). Genetic nature of retinitis pigmentosa is heterogeneous. In 1984, after first reported linkage of retinitis pigmentosa locus to a DNA marker on chromosome X (Bhattacharya et al. 1984), currently mutation over 58 genes are known to cause retinitis (Table 1).

Table 1.

Genes associated with retinitis pigmentosa (adapted from; Retnet)

| Disease category | Genes and loci (total number) | No. of identified genes |

|---|---|---|

| Autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa | 23 | 22 |

| Autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa | 37 | 36 |

| X-linked retinitis pigmentosa | 5 | 2 |

In retinitis pigmentosa carriers, the nature of the disease can be non-syndromic (limited to the eye), or it can appear in syndromic nature. For example, in the case of syndromic nature of the disorder, patients carrying Usher syndrome express the combination of retinitis pigmentosa and hearing impairment (Mathur and Yang 2015). Approximately 20–30% of patients carrying retinitis pigmentosa has an association with the non-ocular disorder, and would be categorized as carrying syndromic retinitis pigmentosa. For an instant, missense mutations of the BBS2 gene cause Bardet-Biedl syndrome (retinitis pigmentosa, obesity, mental retardation and polydactyl) or non-syndromic retinitis pigmentosa (Shevach et al. 2015). Non-syndromic retinitis pigmentosa may be inherited as autosomal recessive, autosomal dominant digenic, X-linked and even mitochondrial patterns (Ferrari et al. 2011). Overall percentage prevalence of non-syndromic and syndromic retinitis pigmentosa is shown in Table 2. The most patronize types of syndromic retinitis pigmentosa are Usher syndrome and Bardet-Biedl syndrome (Ferrari et al. 2011).

Table 2.

Overall percentage prevalence of retinitis pigmentosa

| Pattern of inheritance | Type of disease | Prevalence | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Systematic or syndromic retinitis pigmentosa | Bardet-Biedl syndrome | 5% | Ferrari et al. (2011), Daiger et al. (2007), Bowne et al. (2006), Schwartz et al. (2003) |

| Usher syndrome | 10% | ||

| Non-syndromic retinitis pigmentosa | Autosomal recessive | 15–20% | |

| Autosomal dominant | 20–25% | ||

| X-linked | 10–15% | ||

| Digenic | Very rare | ||

| Leber congenital amaurosis | 4% |

Genetic characterizations of retinitis pigments are complicated, so authorized genotype–phenotype correlation is impossible to define. In addition to numerosity of variations, as a matter of fact, different disorders may be caused by the different mutations in the same gene and same mutations can cause inter-familial and intra-familial phenotypic variability. For example, the vast majority of rhodopsin mutations depict a classical autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance, leading to retinitis pigmentosa. However, low numbers of mutations depict autosomal recessive patterns of inheritance (Berger et al. 2010). Likewise, major X-linked recessive retinitis pigmentosa gene—RPGR—is linked with the mutations in male patients and no phenotypic male-to-male characteristics have ever been reported to transmit. The current review focuses on the genesis on the retinitis pigmentosa and how mutations lead to pathophysiological effects. For the accurate outcomes, mutations frequency of the genes will be evaluated that are associated with retinitis pigmentosa and how these mutations lead to retinal degradation; ultimately inducing retinitis pigmentosa.

Visual phototransduction

To better understand how the mutations in genes associated with retinitis pigmentosa influence the functions of proteins, the molecular basis of the visual phototransduction is needed to be understood. Visual phototransduction is a biological process through which light signals are converted into electrical signals in the light-sensitive cells(rod and cone photoreceptors) in the retina of the eye. The photoreceptors cells are the polarized type of neurons in the retina that is capable of phototransduction. Photoreceptors cells consist of a cell body, an inner segment, an outer segment and synaptic region. Inner segment is connected to the outer segment via cilium. The molecular machinery resides within the inner segment that is involved in the biosynthesis, membrane trafficking and the energy metabolism system. Outer segment is comprised of membranous discs circumvented by a plasma membrane. Over 90% of the total protein in the outer segment is rhodopsin. Vision begins via an apoprotein (opsins) and a chromophore (11-cis, derived from vitamin A) attached to the opsin by Schiff base bond. Isomerization of 11-cis retinal is induced via light absorption by rhodopsin protein to all-trans retinal, ultimately conformation of the opsin is changed, hence vision is initiated. In photoreceptor cells, all-trans retinal that is released from opsin is reduced to all-trans retinol and then moved to the pigmented layer of the retina. For the continuity of vision, in retinal pigment epithelium the 11-cis retinal is produced again from all-trans-retinol. This process is accomplished by 65 kDa isomerohydrolase expressed in retinal pigment epithelium known as RPE65 (Daiger et al. 2007; Redmond et al. 1998). Rhodopsin acts and triggers its GTP-binding protein, transducin, and canonical second-messenger signaling pathway is initiated with help of heterotetrameric phosphodiesterase 6 complexes.

Clinical description of retinitis pigmentosa

Retinitis pigmentosa develops over multiple decades; long lasting disease. Even so in extreme cases rapid development has also been shown. Retinitis pigmentosa can be handily classified into three stages; (1) the early stage, (2) the middle stage, and (3) the end stage.

Early stage

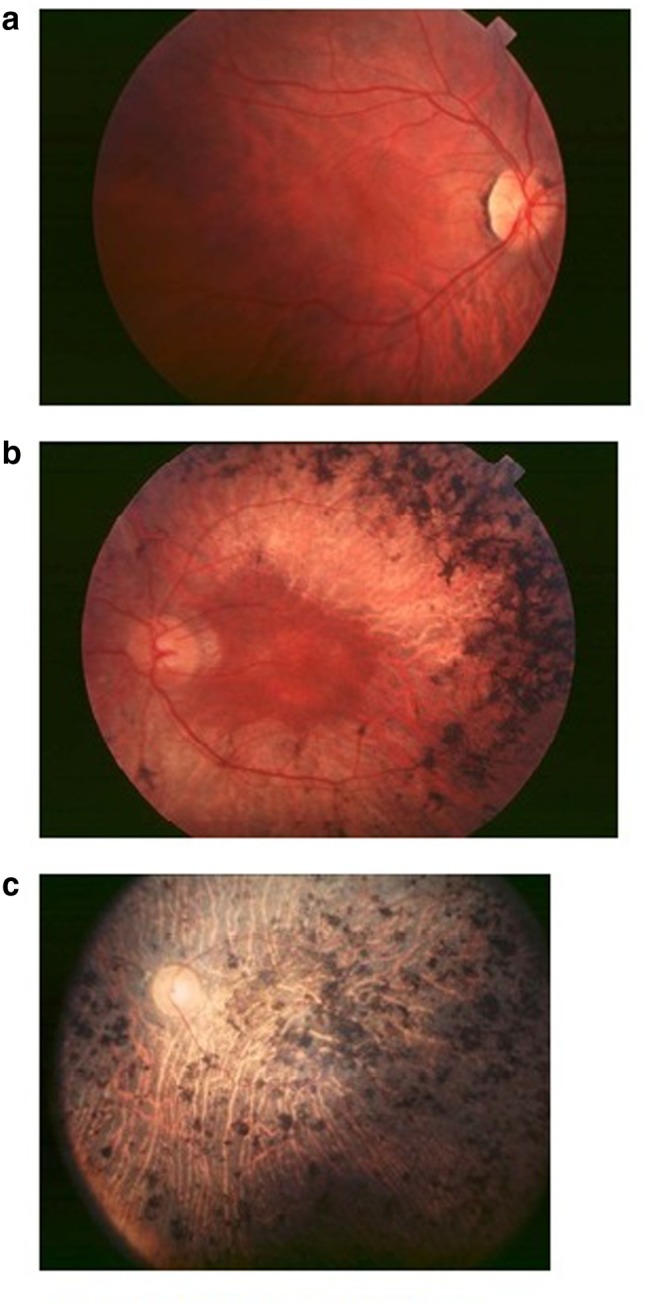

A major symptom of early stage retinitis pigmentosa is night blindness; may be appeared at different stages of life; from the first years of age, or during the second decade of life or even later. Patients carrying mild night blindness often ignore it, and it appears in teen ages, in dim light. At this stage, defects like peripheral visual field appear in dim light, but in daylights patients spent normal life and intensity of these defects are minimal. At the early stage of retinitis pigmentosa it is difficult to diagnose, especially when any kind of familial history is not available. Clinical examination of the fundus may appear normal (Fig. 1a); the optic disc is normal, no bone-spicule shaped pigment deposits are present, retinal arterioles fading is at a modest level, and color vision is normal. In the visual field tests under scotopic conditions, scotomas are revealed, but this test is usually carried out in mesopic conditions. Electroretinogram is a key test to better understand the prevailing conditions. Mostly, low amplitude b-waves are shown in results that dominate in scotopic conditions. However, if the retina partially defects, electroretinogram may appear normal.

Fig. 1.

a Early stage fundus of patients carrying retinitis pigmentosa. b Mid stage fundus of patients carrying retinitis pigmentosa. c End stage fundus of patients carrying retinitis pigmentosa

Middle stage

Patients become cognizant of the loss of peripheral visual field in daylight conditions; patients miss hands in handshaking, during drive they cannot see side-coming cars. Night blindness is evident; with troubles to drive during night, walking at evening or in dark staircases. Dyschromatopsia to very light colors (yellow and blue hues) is present. Photophobic conditions appear, particularly in diffuse lights, leads to reading problems because of the narrow window between too bright light and insufficient light, also because of lower visual acuity. Clinical examination of fundus discloses the retinal atrophy along with bone-spicule shaped pigments in the mid-periphery (Fig. 1b). The optic disc is fairly pale and retinal vessels narrowing are apparent. In scotopic conditions electroretinogram is commonly unrecordable, and at 30 Hz flickers, bright light cone responses are hypo voluted.

End stage

Without external control, patients cannot move from one place to other, because of peripheral vision loss. Reading is difficult without magnifying glasses (reading become impossible when central visual field vaporizes), and photophobia is intense. Clinical examination of the fundus (Fig. 1c) reveals the macular area with widespread pigment deposits. The optic disc has impressible achromasia and blood vessels are thin. Electroretinogram is unrecordable.

Genetic characterization of retinitis pigmentosa

Non-syndromic retinitis pigmentosa

Autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa

So far mutations in 24 different genes have been associated with autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa (RetNet 2015) but only a few genes account for a relevant percentage of the retinitis pigmentosa cases, these include, RHO (26.5%), RPRH2 (5-9%), PRPF31 (8%) and RP1 (3-5%) (Ferrari et al. 2011). Table 3 shows the genes that are associated with autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa.

Table 3.

Genes associated with autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa (adapted from; GeneCards, Retnet and OMIM)

| Identified gene | Chromosomal location | Function of gene | Other phenotypes | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPP2 | 2q37.1 | It could coordinate an aspect of bone turnover | None | Liu et al. (2015) |

| OR2W3 | 1q44 | Initiate a neuronal response that triggers the perception of a smell | None | Ma et al. (2015) |

| HK1 | 10q22.1 | Helps in glycolysis and gluconeogenesis, energy pathway | Excessive nonspherocytic hemolytic anemia, recessive hereditary neuropathy (Russe) | Sullivan et al. (2014), Wang et al. (2014) |

| BEST1 | 11q12.3 | Provides instructions for making Bestrophin | Recessive retinitis Pigmentosa | Burgess et al. (2008), Davidson et al. (2009) |

| CA4 | 17q23.2 | Involves in respiration, calcification, acid–base balance | None | Kohn et al. (2008), Alvarez et al. (2007) |

| CRX | 19q13.32 | Maintain normal rod and cone function | Dominant Leber congenital amaurosis | Menotti-Raymond et al. (2010) |

| TOPORS | 9p21.1 | It has the ability to interact with the tumor suppressor protein P53 | None | Chakarova et al. (2007), (2011) |

| FSCN2 | 17q25.3 | Acts as an actin bundling protein | None | Zhang et al. (2007a), Wada et al. (2001, 2003) |

| GUCA1B | 6p21.1 | Stimulates guanylyl cyclase 1 and guanylyl cyclase 2 | Dominant macular dystrophy | Sato et al. (2005), Payne et al. (1999) |

| IMPDH1 | 7q32.1 | Catalyzes the conversion of inosine 5′-phosphate (IMP) to xanthosine 5′-phosphate | Dominant Leber congenital amaurosis | Mortimer et al. (2008), Mortimer and Hedstrom (2005) |

| NRL | 14q11.2 | Transcription factor which regulates the expression of RHO and PDE6B genes | Autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa | Mears et al. (2001), Bessant et al. (1999) |

| NR2E3 | 15q23 | Rod development and repressor of cone development | Recessive retinitis pigmentosa | Escher et al. (2009), Coppieters et al. (2007), Gire et al. (2007) |

| SEMA4A | 1q22 | Cell surface receptor | Dominant cone-rod dystrophy | Abid et al. (2006), Rice et al. (2004), Kumanogoh et al. (2002) |

| RHO | 3q22.1 | Required for photoreceptor cell viability after birth | Recessive retinitis pigmentosa | Dryja et al. (1993), Rosenfeld et al. 1992), Dryja et al. (1991) |

| PRPH2 | 6p21.1 | Essential for disk morphogenesis | Digenic forms with ROM1 | Boon et al. (2009), Chang et al. (2002), Ali et al. 2000) |

| RPE65 | 1p31.2 | Roles in the production of 11-cis retinal and in visual pigment regeneration | None | Acland et al. (2001), Lotery et al. (2000) |

| PRPF8 | 17p13.3 | Functions as a scaffold that mediates the ordered assembly of spliceosomal proteins and snRNAs | None | McKie et al. (2001), Kojis et al. (1996), Goliath et al. (1995) |

| ROM1 | 11q12.3 | Essential for disk morphogenesis | Digenic retinitis pigmentosa with PRPH2 | Yang et al. (2008), Zhang et al. (2007b) |

| PRPF31 | 19q13.42 | Involved in pre-mRNA splicing | None | Venturini et al. (2012), Sullivan et al. (2006b) |

| KLHL7 | 7p15.3 | mediates’Lys-48'-linked ubiquitination | None | Friedman et al. (2009) |

| RP1 | 8q12.1 | Required for the differentiation of photoreceptor cells | Recessive retinitis pigmentosa | Avila-Fernandez et al. (2012), Riazuddin et al. (2005) |

| PRPF4 | 9q32 | Participates in pre-mRNA splicing | None | Chen et al. (2014) |

| PRPF3 | 1q21.2 | Participates in pre-mRNA splicing | None | Chakarova et al. (2002), Heng et al. (1998) |

| RDH12 | 14q24.1 | Key enzyme in the formation of 11-cis-retinal from 11-cis-retinol during regeneration of the cone visual pigments | Recessive leber congenital amaurosis | Fingert et al. (2008), Perrault et al. (2004), Janecke et al. (2004) |

| PRPF6 | 20q13.33 | Participates in pre-mRNA splicing | None | Tanackovic et al. (2011) |

| RP9 | 7p14.3 | Roles in B-cell proliferation in association with PIM1 | None | Sullivan et al. (2006a), Maita et al. (2004), Keen et al. (2002) |

| SNRNP200 | 2q11.2 | Involves in spliceosome assembly, activation and disassembly | None | Benaglio et al. (2011), Li et al. (2010b), Zhao et al. (2009) |

PRPF31 (Pre-mRNA processing factor 31)

Mutation in PRPF31 (Pre-mRNA splicing factor of 61 kDa) is currently proposed to play a vital role in autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa, inducing 1–8% cases of autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa (Audo et al. 2010a; Venturini et al. 2012).

Apparently PRPF31 is one of the three pre-mRNA splicing factors inducing autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa, two other factors are PRPF3 (1% of all cases) and PRPF8 (3% of all cases). One of the unique characteristics of mutations in PRPF31 is the incomplete penetrance. Mode of inheritance may be complicated to determine if symptomless carriers have affected parents and children, because of that genetic counseling of family is hindered. Symptomatic patients have been reported to experience night blindness and loss of visual field in teenage, and are generally reported as blind, when they are in the 30 s. Comparison of haplotype analysis of asymptomatic and symptomatic patients reveals that both types inherit different wild-type allele. Wild-type allele with a high level of expression may adjust for the nonfunctional mutated allele, but wild-type allele with low expression is unable to reach the activity threshold level of required photoreceptor-specific PRPF31 (Waseem et al. 2007; Vithana et al. 2003).

RP1 (retinitis pigmentosa 1)

By positional cloning RP1 gene was first time reported by linkage testing in large autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa family southeastern Kentucky. Mutations in RP1 gene induce both dominant and recessive types of retinitis pigmentosa (Blanton et al. 1991; Field et al. 1982). 240-kD retinal photoreceptor-specific protein is encoded by RP1 gene and the expression of RP1 in very prominent. Clinical diagnosis of patients carrying RP1 mutated gene shows reduced visual field diameters. Generally genetic disorders are thought to be caused by environmental factors, allelic heterogeneity and genetic variations, but for RP1 disorders, genetic variants are thought to important because of the severity of disorder variety reveals the patients with the same primary mutation.

RHO (rhodopsin)

The first component of visual transduction pathway is rhodopsin and when the light is absorbed by the rod cell of the retina, it is activated (Murray et al. 2009). With more than 100 mutations, approximately 30–40% cases of autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa are induced due to mutations in RHO gene. Autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa and autosomal dominant congenital night blindness can also be induced by the mutations in RHO gene. Murray and colleagues reported the autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa case resulted from RHO gene mutation, which nominated a protein with no 6th and 7th transmembrane, including the 11-cis retinal binding site (Rosenfeld et al. 1992). In a mouse model experiment carrying dominant retinitis pigmentosa, improved retinal function was achieved, following subretinal administration of recombinant are non-associated virus vectors containing RNAi-based suppressors (Chadderton et al. 2009). Latterly, restoration of visual function was achieved in P23H transgenic rats following subretinal administration of recombinant are non-associated virus vectors containing Bip/Grp78 gene (Gorbatyuk et al. 2010). In spite of all knowledge in autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa induced by the RHO gene mutation, therapeutical approaches did not proceed at the same pace.

PRPH2 (Peripherin 2)

The PRPH2 (Peripherin 2) gene, once recognized as RDS (retinal degeneration slow) gene containing 3 exons and encoded 346 amino acid protein (39-kDa integral membrane glycoprotein). The protein is reported at the outer segment disc of cone and rod photoreceptor, containing one intradiscal domain (D2) and four transmembrane domains (known as M1–M4). The protein in combination with another protein (ROM1) forms homo-tetrameric and heterotetrameric complexes and also forms a homo-oligomeric structure with itself (Loewen et al. 2001). In 1991, PRPH2 mutations inducing retinitis pigmentosa were first time reported and cause about 5-9% of autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa cases. Mutation in PRPH2 gene and ROM1 gene has been observed to cause digenic retinitis pigmentosa (Dryja et al. 1997).

Autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa

For autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa, over 40 genes have been mapped (Table 4) and most of the genes are rare and cause 1% of fewer cases. Some genes like RP25, PDE6A, RPE65, and PDE6B have higher prevalence percentage up to 2–5% of all cases.

Table 4.

Genes associated with autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa (adapted from; GeneCards, Retnet and OMIM)

| Identified gene | Gene function | Chromosomal location | Phenotypes other than recessive retinitis pigmentosa | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADIPOR1 | Receptor for ADIPOQ, required for normal glucose and fat homeostasis | 1q32.1 | Bardet-Biedl like | Xu et al. (2016a) |

| POMGNT1 | Participates in O-mannosyl glycosylation | 1p34.1 | None | Xu et al. (2016b) |

| ZNF408 | May be involved in transcriptional regulation | 11p11.2 | Dominant familial exudative vitreoretinopathy | Avila-Fernandez et al. (2015), Collin et al. (2013) |

| NEUROD1 | Neurogenesis regulator D1, acts as a transcriptional activator | 2q31.3 | None | Wang et al. (2015) |

| IFT172 | Necessary for cilia maintenance and formation. Plays an indirect role in hedgehog signaling | 2p33.3 | Recessive Bardet-Biedl syndrome | Bujakowska et al. (2015) |

| IFT140 | Component of the IFT complex A, important role in proper development and function of ciliated cells and maintenance of ciliogenesis and cilia | 16p13.3 | Recessive Mainzer-Saldino syndrome, recessive Leber congenital amaurosis | Xu et al. (2015b), Schmidts et al. (2013) |

| HGSNAT | Participates in glycosaminoglycan degradation and glycan structures degradation | 8p11.21 | Recessive mucopolysaccharidosis | Haer-Wigman et al. (2015) |

| RDH11 | Shows an oxidoreductive catalytic activity for retinoids, involves in the metabolism of short-chain aldehydes | 14q24.1 | None | Xie et al. (2014) |

| DHX38 | Embryogenesis, spermatogenesis, and cellular growth and division | 16q22.2 | Early onset with macular coloboma | Ajmal et al. (2014) |

| KIZ | Required for stabilizing the expanded pericentriolar material around the centriole | 20p11.23 | None | El Shamieh et al. (2014) |

| BEST1 | Anion channel | 11q12.3 | Dominant retinitis Pigmentosa | Burgess et al. (2008), Davidson et al. (2009) |

| ABCA4 | Retinal metabolism | 1p22.1 | Recessive macular dystrophy | Maugeri et al. (2000), Zhang et al. (1999) |

| ARL2BP | Role in the nuclear translocation | 16p13.3 | None | Davidson et al. (2013) |

| C2orf71 | Might have an important role in developing of normal vision | 2p23.2 | None | Downs et al. (2013), Nishimura et al. (2010) |

| C8Oorf37 | Unknown | 8q22.1 | None | van Huet et al. (2013), Estrada-Cuzcano et al. (2012) |

| CERKL | Tissue maintenance and development | 2q31.3 | None | Aleman et al. (2009), Tuson et al. (2004 |

| CLRN1 | Conjugation | 3q25.1 | None | Khan et al. (2011), Adato et al. (2002) |

| CNGA1 | Phototransduction | 4p12 | None | Dryja et al. (1995), Griffin et al. (1993 |

| CNGB1 | Phototransduction | 16q13 | None | Bareil et al. (2001), Ardell et al. (2000) |

| CRB1 | Tissue maintenance and development | 1q31.3 | Recessive leber congenital amaurosis | McKay et al. (2005 |

| DHDDS | Catalysis | 1p36.11 | None | Zuchner et al. (2011), Zelinger et al. (2011) |

| DHX38 | ATP-binding RNA helicase involves in pre-mRNA splicing | 16q22.2 | None | Ajmal et al. (2014) |

| EMC1 | Unknown | 1p36.13 | None | Abu-Safieh et al. (2013) |

| EYS | Protein of the extracellular matrix | 6q12 | Unknown | Audo et al. (2010b), Barragán et al. (2008) |

| FAM161A | Unknown | 2p15 | Unknown | Langmann et al. (2010), Bandah-Rozenfeld et al. (2010b) |

| GPR125 | Orphan receptor | 4p15.2 | None | Abu-Safieh et al. (2013) |

| IDH3B | Involved in Krebs cycle | 20p13 | Unknown | Hartong et al. 2008 |

| IMPG2 | Component of the retinal intercellular matrix | 3q12.3 | Unknown | Bandah-Rozenfeld et al. (2010a) |

| KIAA1549 | Unknown | 7q34 | None | Abu-Safieh et al. (2013) |

| KIZ | Unknown | 20p11.23 | None | Tuz et al. (2014), Shaheen et al. (2014), Akizu et al. (2014) |

| LRAT | Retinal metabolism | 4q32.1 | Recessive leber congenital amaurosis | Xiao et al. (2011 |

| MAK | An important function in spermatogenesis | 6p24.2 | None | Stone et al. (2011) |

| MERTK | Transmembrane protein | 2q13 | None | Mackay et al. (2010) |

| MVK | Regulatory site in cholesterol biosynthetic pathway | 12q24.11 | None | Siemiatkowska et al. (2013) |

| NEK2 | Involves in control of centrosome separation and bipolar spindle formation | 1q32.3 | None | Nishiguchi et al. (2013) |

| NR2E3 | Transcription factor | 15q23 | Dominant retinitis pigmentosa, Recessive enhanced S-cone syndrome | Escher et al. (2009), Coppieters et al. (2007), Gire et al. (2007) |

| NRL | Tissue maintenance and development | 14q11.2 | Dominant retinitis pigmentosa | Mears et al. (2001), Bessant et al. (1999) |

| PDE6A | Phototransduction | 5q33.1 | None | Dryja et al. (1999) |

| PDE6B | Phototransduction | 4p16.3 | Dominant congenital stationary night blindness | Chang et al. (2006) |

| PDE6G | Phototransduction | 17q25.3 | None | Dvir et al. (2010) |

| PRCD | Unknown | 17q25.1 | Unknown | Nevet et al. (2010) |

| PROM1 | Cellular structure | 4p15.32 | Recessive retinitis pigmentosa with macular degeneration | Yang et al. (2008) |

| RBP3 | Retinal metabolism | 10q11.22 | Unknown | Parker et al. (2009) |

| RGR | Retinal metabolism | 10q23.1 | Dominant choroidal sclerosis | Morimura et al. (1999) |

| RHO | Phototransduction | 3q22.1 | Dominant retinitis pigmentosa | Dryja et al. (1993), Rosenfeld et al. (1992), Dryja et al. (1991) |

| RLBP1 | Retinal metabolism | 15q26.1 | Recessive Bothnia dystrophy | Eichers et al. (2002 |

| RP1 | Tissue maintenance and development | 8q12.1 | Dominant retinitis pigmentosa | Avila-Fernandez et al. (2012), Riazuddin et al. (2005), Liu et al. (2002) |

| RPE65 | Retinal metabolism | 1p31.2 | Recessive leber congenital amaurosis | Acland et al. (2001), Lotery et al. (2000) |

| SAG | Phototransduction | 2q37.1 | Recessive Oguchi disease | Nakazawa et al. (1998) |

| SLC7A14 | 3q26.2 | None | Jin et al. (2014) | |

| SPATA7 | Unknown | 14q31.3 | None | Wang et al. (2009) |

| TTC8 | Cellular structure | 14q32.11 | Recessive Bardet-Biedl syndrome | Riazuddin et al. (2010) |

| TULP1 | Tissue maintenance and development | 6p21.31 | Recessive leber congenital amaurosis | Hanein et al. (2004) |

| USH2A | Cellular structure | 1q41 | Recessive Usher syndrome | Seyedahmadi et al. (2004), Bhattacharya et al. (2002) |

| ZNF513 | Expression factor | 2p23.3 | None | Naz et al. (2010), Li et al. (2010a) |

Rp25

Mutations that are rare to another geographical region can be the common reason to cause autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa in particular populations, for example the RP25 locus has been reported for causing 10-20% of autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa cases in Spanish populations (Barragán et al. 2008).

PDE6 (PDE6A, PDE6B, PDE6G)

One α, β and two γ subunits are important parts of the PDE6 complex; which encode a protein that has a vital function in rod photoreceptor visual phototransduction. Intracellular cGMP level is maintained by the complex by the hydrolyzing process of cGMP, due to G protein light activation(Tsang et al. 1998). In retinitis pigmentosa case, processes are unknown that induce rod photoreceptor death, but it is thought that low PDE6 activity may lead to rode-cone devolution. For proper photoreceptor function every subunit of PDE6 complex is necessary, in fact for autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa, mutations in PDE6A and PDE6B genes are second most familiar cause for inducing disease. Visual loss is the main risk for heterozygous carriers, carrying mutations in PDE6 gene, when PDE6 is inhibited using drugs like revatio, cialis, or levitra (Tsang et al. 2008). Latterly PDE6G gene is reported with a mutation, causing autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa (early onset) (Dvir et al. 2010).

Rpe65

RPE65 (an enzyme by which all-trans-retinyl esters in hydrolyzed into 11-cis-retinol) is vital for the re-formation of the visual pigments essential for rod-mediated and cone-mediated vision and it is expressed in the pigmented layer of the retina. RPE65 gene has been reported for approximately 60 mutations and causing recessive retinitis pigmentosa (2%) and leber congenital amaurosis (16%) (Cai et al. 2009). In three pre-clinical experiments, patients with leber congenital amaurosis were injected with adeno-associated viral vectors comprising the human RPE65 cDNA. Modest level improvements were achieved in visual acuity (Bainbridge et al. 2008; Cideciyan et al. 2008; Maguire et al. 2008).

X-linked retinitis pigmentosa

X-linked retinitis pigmentosa patients exhibit severe phenotypes in early phases of disorder development and account approximately 10–15% of all retinitis pigmentosa cases. In some cases, deafness, abnormal sperm development and defective respiratory tract were noticed (Veltel and Wittinghofer 2009). Only two gene loci (RP2 and RP3) have been recognized so far out of six mapped gene loci (RP2, RP6, RP23, RP24, RP34 and RPGR) on X-chromosome (Table 5). More than 70% patients carrying X-linked retinitis pigmentosa have mutations in RP3 gene, and RP3 gene product is located on an external segment of rod photoreceptor (Vervoort et al. 2000). Approximately 10–15% patients carry X-linked retinitis pigmentosa due to mutations in RP2 gene (Veltel and Wittinghofer 2009).

Table 5.

Genes associated with X-linked retinitis pigmentosa (GeneCards, Retnet and OMIM)

| Identified gene | Gene Function | Chromosomal location | Phenotypes | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OFD1, RP23 | Involves in biogenesis of the cilium | Xp22.2 | None | Webb et al. (2012), Coene et al. (2009) |

| RP2 | Involved in beta-tubulin folding | Xp11.23 | None | Hardcastle et al. (1999), Mears et al. (1999) |

| RPGR | Intraflagellar transport | Xp11.4 | X-linked cone dystrophy, X-linked congenital stationary night blindness | Branham et al. (2012), Pelletier et al. (2007) |

| RP6 | Unknown | Xp21.3-p21.2 | None | Breuer et al. (2000), Musarella et al. (1990) |

| RP24 | Unknown | Xq26-q27 | None | Gieser et al. (1998) |

| RP34 | Tissue development and maintenance | Xq28-qter | None | Melamud et al. (2006) |

Syndromic retinitis pigmentosa

Retinitis pigmentosa is generally an isolated problem; the only eye is affected, but in other various rare cases retinitis pigmentosa is also linked to other disorders. Examples may include Usher syndrome, refsum syndrome, Bardet-Biedl syndrome.

Usher syndrome

Usher syndrome is an autosomal recessive disorder, in which retinitis pigmentosa, hearing impairment and sometimes vestibular dysfunction are associated. Deaf-blindness is the most common disorder due to this syndrome. Prevalence is 1:12,000–1:30,000 individuals in different populations. 10–30% of autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa cases are caused due to usher syndrome (Millan et al. 2011). In clinical manners, usher syndrome is separated into three types, (1) usher type I (severe form), (2) usher type II (moderate to severe form) and (3) usher type III. To date 12 genes have been reported for usher syndrome; 7 genes for usher type I, 3 genes for usher type II and 2 genes for usher type III (Table 6).

Table 6.

Genes identified for Usher syndrome (adapted from; GeneCards, Retnet and OMIM)

| Disease | Identified gene | Chromosomal location | Gene Function | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Usher type I | MYO7A | 11q13.5 | An important role in the renewal of the outer photoreceptor disks, Mediates mechanotransduction in cochlear hair cells | Gibbs et al. (2003), (2004) |

| CDH23 | 10q22.1 | Maintain a proper system of the stereocilia bundle of hair cells in the cochlea, Mediates mechanotransduction in cochlear hair cells | Zheng et al. (2005), Astuto et al. (2002) | |

| PCDH15 | 10q21.1 | Maintain normal retinal and cochlear function | Ahmed et al. (2001), (2003) | |

| USH1C | 11p15.1 | Required for normal hearing, Mediates mechanotransduction in cochlear hair cells | Ebermann et al. (2007a), Ouyang et al. (2002) | |

| USH1G | 17q25.1 | Develop and maintain cochlear hair cell bundles | Weil et al. (2003), Kikkawa et al. (2003) | |

| CIB2 | 15q25.1 | Important for proper photoreceptor cell maintenance and function | Riazuddin et al. (2012) | |

| CLRN1 | 3q25.1 | Role in the excitatory ribbon that conjugates hair cells and cochlear ganglion cells | Khan et al. (2011), Adato et al. (2002) | |

| Usher type II | USH2A | 1q41 | Involves in hearing and vision | Seyedahmadi et al. (2004), Bhattacharya et al. (2002 |

| GPR98 | 5q14.3 | Receptor may have a crucial role in the development of the central nervous system | Hilgert et al. (2009), Ebermann et al. (2009) | |

| DFNB31 | 9q32 | Essential for elongation and sustainment of inner and outer hair cells in the organ of Corti | Ebermann et al. (2007b), Mburu et al. (2003) | |

| Usher type III | HARS | 5q31.3 | Responsible for the synthesis of histidyl-transfer RNA | Puffenberger et al. (2012) |

| ABHD12 | 2p11.21 | May regulate endocannabinoid signaling pathway | Eisenberger et al. (2012), Fiskerstrand et al. (2010) |

Bardet-Biedl syndrome

Bardet-Biedl syndrome is defined a recessive inherited disorder with symptoms of obesity (72%), learning difficulties, abnormalities of the fingers/toes, kidney disease, rod-cone dystrophy (>90%) and renal abnormalities. Bardet-Biedl syndrome affects 1: 120,000 Caucasians, but high prevalence (1:13,000) has been reported in a population of north Atlantic (Moore et al. 2005) and within the Bedouins (1:13500-1:16900) (Teebi 1994). Children carry Bardet-Biedl syndrome has a poor visual prognosis. Night blindness is usually apparent by age 7 to 8 years (Heon et al. 2005; Azari et al. 2006). To date, 21 genes have been associated with Bardet-Biedl syndrome (Table 7).

Table 7.

Genes identified for autosomal recessive Bardet-Biedl syndrome(adapted from; GeneCards, Retnet and OMIM)

| Identified gene | Chromosomal location | Gene function | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| ARL6 | 3q11.2 | Requires for proper retinal function and organization | Chiang et al. (2004) |

| BBIP1 | 10q25.2 | Regulates cytoplasmic microtubule constancy and acetylation | Scheidecker et al. (2014) |

| BBS1 | 11q13 | BBSome requires for ciliogenesis but unnecessary for centriolar satellite function | Mykytyn et al. (2002) |

| BBS2 | 16q12.2 | Katsanis et al. (2001) | |

| BBS4 | 15q24.1 | Requires for microtubule anchoring at the centrosome | Katsanis et al. (2001) |

| BBS5 | 2q31.1 | BBSome requires for ciliogenesis but unnecessary for centriolar satellite function | Li et al. (2004) |

| BBS7 | 4q27 | Badano et al. (2003) | |

| BBS9 | 7p14.3 | Nishimura et al. (2005) | |

| BBS10 | 12q21.2 | Helps in folding of proteins ATP hydrolysis | White et al. (2006) |

| BBS12 | 4q27 | Stoetzel et al. (2007) | |

| CEP290 | 12q21.32 | Triggers ATF4-mediated transcription | Leitch et al. (2008) |

| IFT27 | 22q12.3 | Possesses GTPase activity | Aldahmesh et al. (2014) |

| INPP5E | 9q34.3 | Particular for lipid substrates | Bielas et al. (2009) |

| KCNJ13 | 2q37.1 | Lindstrand et al. (2014) | |

| LZTFL1 | 3p21.31 | May function as a tumor suppressor | Marion et al. (2012) |

| MKKS | 20p12.2 | Helps in folding of proteins ATP hydrolysis | Katsanis et al. (2001) |

| MKS1 | 17q22 | Requires for cell branching morphology | Leitch et al. (2008) |

| NPHP1 | 2q13 | Control epithelial cell polarity in combination with BCAR1 | Lindstrand et al. (2014), Mollet et al. (2002) |

| SDCCAG8 | 1q43 | Establish cell polarity and epithelial lumen formation | Chaki et al. (2012) |

| TRIM32 | 9q33.1 | May mediate biological activity of the HIV-1 | Chiang et al. (2006) |

| TTC8 | 14q32.11 | Requires for ciliogenesis but unnecessary for centriolar satellite function | Riazuddin et al. (2010) |

Whole-exome sequencing as an effective tool in clinical and symptomatic genetics

Advancement in DNA sequencing has become the most efficient resources for basic biological and clinical research, and has been applied in various fields such as biological systematics, diagnostics, biotechnology, parental testing and forensic identifications. The combination of chain termination sequence (Mullis et al. 1992) and polymerase chain reaction (Sanger et al. 1977) established many of the prominent events such as the completion of the Human Genome Project that provided barely ample references to study the genetic modifications in associated phenotypes (Venter 2003; Sachidanandam et al. 2001). Recently new technologies for whole-genome sequencing and whole-exome sequencing replaced the traditional methods with low-cost sequencing cost per exome/genome. These advanced next-generation sequencing technologies, revolutionized the clinical structure to improve human health, although there are many problems to be addressed like, the high cost of the procedure, user-friendly software to analysis raw genetics and sequence data and the ethical issues that are related to gathering genetic data.

Role of whole-exome sequencing in human genetic disorders

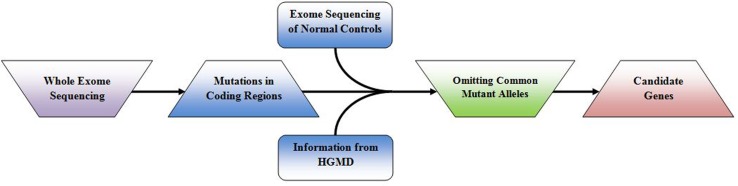

According to OMIM Statistics presently, over 6000 presumptively single gene disorders have been reported, but the molecular basis of nearly two-third of disorders has not been described. Finding phenotypic variants and causative genes help in understanding the pathogenic mechanism of the prevailing disorder. In patients or small families with newly identified variants, genetic diagnosis is difficult to conceivable just on the basis of variant finding. It is much difficult to find more patients if the disorder is very rare. Recently reported variants are needed to validate for having pathologic effect with the help of functional experiments; biochemical confirmatory experiments are allowed to execute if the mutated gene has delimitated function in a well-known pathway associated with the disease. Novel genes identification causing rare single gene disorders is important to apprehend the biological pathways causing disorder as well as therapeutic management. Recent studies emphases that whole-exome sequencing is a powerful technique to find out casual genes responsible for Mendelian disorders (Rabbani et al. 2012); Fig. 2 shows the combination of exome sequencing and filtering strategy is helpful to distinguish the fundamental gene causing Mendelian disorders.

Fig. 2.

Filtering methodologies and exome sequencing

Heterogeneous single gene phenotypes

There are many genetically heterogeneous disorders like retinitis pigmentosa, intellectual disability, hereditary hearing impairment, and autistic spectrum disorder. Whole-exome sequencing has successfully resulted to distinguish various genes causing retinal disorders. Table 8 shows the role of whole-exome sequencing in identifying de novo genes in retinal disorders.

Table 8.

De novo genes of retinal disorders reported by whole-exome (adapted from; GeneCards, Retnet and OMIM)

| Disorder (type of retinal disorder) | Chromosomal location | Gene identified | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recessive macular dystrophy | 1p13.3 | DRAM2 | El-Asrag et al. (2015) |

| Recessive achromatopsia | 1q23.3 | ATF6 | Ansar et al. (2015), Kohl et al. (2015), Xu et al. (2015a) |

| Dominant retinitis pigmentosa | 1q44 | OR2W3 | Ma et al. (2015) |

| Recessive Bardet-Biedl syndrome; recessive retinitis pigmentosa | 2p33.3 | IFT172 | Bujakowska et al. (2015) |

| Recessive retinitis pigmentosa | 2q31.3 | NEUROD1 | Wang et al. (2015) |

| Dominant retinitis pigmentosa | 2q37.1 | SPP2 | Liu et al. (2015) |

| Recessive oculoauricular syndrome | 4p16.1 | HMX1 | Gillespie et al. (2015) |

| Recessive microcephaly, growth failure and retinopathy | 4q28.2 | PLK4 | Martin et al. (2014) |

| Recessive retinitis pigmentosa, non-syndromic recessive mucopolysaccharidosis | 8p11.21 | HGSNAT | Haer-Wigman et al. (2015) |

| Recessive retinal dystrophy with iris coloboma | 9q21.12 | MIR204 | Conte et al. (2015) |

| Dominant retinitis pigmentosa; recessive nonspherocytic hemolytic anemia, recessive hereditary neuropathy | 10q22.1 | HK1 | Sullivan et al. (2014), Wang et al. (2014) |

| Dominant familial exudative vitreoretinopathy; recessive retinitis pigmentosa with vitreal alterations | 11p11.2 | ZNF408 | Avila-Fernandez et al. (2015), Collin et al. (2013) |

| Recessive cone-rod dystrophy; recessive Joubert syndrome | 12q21.33 | POC1B | Beck et al. (2014), Durlu et al. (2014), Roosing et al. (2014) |

| Recessive retinitis pigmentosa | 14q24.1 | RDH11 | Xie et al. (2014) |

| Recessive cone and cone-rod dystrophy | 14q24.3 | TTLL5 | Sergouniotis et al. (2014) |

| Recessive chorioretinopathy and microcephaly | 15q15.3 | TUBGCP4 | Scheidecker et al. (2015) |

| Recessive retinal dystrophy and cerebellar dysplasia | 18p11.31-p11.23 | LAMA1 | Aldinger et al. (2014) |

| Recessive Boucher-Neuhauser syndrome with chorioretinal dystrophy | 19p13.2 | PNPLA6 | Kmoch et al. (2015), Synofzik et al. 2013, Topaloglu et al. (2014) |

| Recessive retinitis pigmentosa | 20p11.23 | KIZ | El Shamieh et al. (2014) |

| Recessive Usher syndrome | 20q11.22 | CEP250 | Khateb et al. (2014) |

Future concerns

In near future it is hoped that, new strategies will be introduced for molecular diagnosis of retinitis pigmentosa for clinical practices, and disease inducing variations in genes will be discovered. But for this hope to come true, specific conditions are needed to meet; (1) All disease-causing variations in genes should possibly be reported, (2) techniques for molecular diagnosis should be low-cost, authentic, quick and widely available, (3) clinical should have the ability to understand the molecular information provided by a molecular diagnosis of disease. Currently reliable technologies are available and new technologies are rising that enhance the chances to report new mutations in individuals. For known mutations detection, currently array-based diagnostic technology is available for several retinal diseases. Next-generation sequencing is allowing the researchers to identify disease-causing variants and to report novel genes for the specific disease. The latest techniques have recently been utilized to detect genes and variants causing autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa against the conventional methods (Daiger et al. 2010; Bowne et al. 2011).

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interests.

Contributor Information

Muhammad Umar Ali, Email: m.umar.ali03@gmail.com.

Muhammad Saif Ur Rahman, Email: fiasanar@gmail.com.

Jiang Cao, Email: caoj@zju.edu.cn.

Ping Xi Yuan, Email: pingxiyuan@126.com.

References

- Abid A, Ismail M, Mehdi SQ, Khaliq S. Identification of novel mutations in the SEMA4A gene associated with retinal degenerative diseases. J Med Genet. 2006;43(4):378–381. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2005.035055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abu-Safieh L, Alrashed M, Anazi S, Alkuraya H, Khan AO, Al-Owain M, Al-Zahrani J, Al-Abdi L, Hashem M, Al-Tarimi S, Sebai MA, Shamia A, Ray-Zack MD, Nassan M, Al-Hassnan ZN, Rahbeeni Z, Waheeb S, Alkharashi A, Abboud E, Al-Hazzaa SA, Alkuraya FS. Autozygome-guided exome sequencing in retinal dystrophy patients reveals pathogenetic mutations and novel candidate disease genes. Genome Res. 2013;23(2):236–247. doi: 10.1101/gr.144105.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acland GM, Aguirre GD, Ray J, Zhang Q, Aleman TS, Cideciyan AV, Pearce-Kelling SE, Anand V, Zeng Y, Maguire AM, Jacobson SG, Hauswirth WW, Bennett J. Gene therapy restores vision in a canine model of childhood blindness. Nat Genet. 2001;28(1):92–95. doi: 10.1038/ng0501-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adato A, Vreugde S, Joensuu T, Avidan N, Hamalainen R, Belenkiy O, Olender T, Bonne-Tamir B, Ben-Asher E, Espinos C (2002) USH3A transcripts encode clarin-1, a four-transmembrane-domain protein with a possible role in sensory synapses. European Journal of Human Genetics 10 (6) [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ahmed ZM, Riazuddin S, Bernstein SL, Ahmed Z, Khan S, Griffith AJ, Morell RJ, Friedman TB, Riazuddin S, Wilcox ER. Mutations of the protocadherin gene PCDH15 cause usher syndrome type 1F. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;69(1):25–34. doi: 10.1086/321277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed ZM, Riazuddin S, Ahmad J, Bernstein SL, Guo Y, Sabar MF, Sieving P, Riazuddin S, Griffith AJ, Friedman TB. PCDH15 is expressed in the neurosensory epithelium of the eye and ear and mutant alleles are responsible for both USH1F and DFNB23. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12(24):3215–3223. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajmal M, Khan MI, Neveling K, Khan YM, Azam M, Waheed NK, Hamel CP, Ben-Yosef T, De Baere E, Koenekoop RK (2014) A missense mutation in the splicing factor gene DHX38 is associated with early-onset retinitis pigmentosa with macular coloboma. Journal of medical genetics:jmedgenet-2014-102316 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Akizu N, Silhavy JL, Rosti RO, Scott E, Fenstermaker AG, Schroth J, Zaki MS, Sanchez H, Gupta N, Kabra M, Kara M, Ben-Omran T, Rosti B, Guemez-Gamboa A, Spencer E, Pan R, Cai N, Abdellateef M, Gabriel S, Halbritter J, Hildebrandt F, van Bokhoven H, Gunel M, Gleeson JG. Mutations in CSPP1 lead to classical Joubert syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2014;94(1):80–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldahmesh MA, Li Y, Alhashem A, Anazi S, Alkuraya H, Al-Awaji A, Sakati S, Alkharashi A, Alzahrani S, Al Hazzaa SA (2014) IFT27, encoding a small GTPase component of IFT particles, is mutated in a consanguineous family with Bardet-Biedl syndrome. Human Molecular Genetics:ddu044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Aldinger KA, Mosca SJ, Tétreault M, Dempsey JC, Ishak GE, Hartley T, Phelps IG, Lamont RE, O’Day DR, Basel D. Mutations in LAMA1 cause cerebellar dysplasia and cysts with and without retinal dystrophy. Am J Hum Genet. 2014;95(2):227–234. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aleman TS, Soumittra N, Cideciyan AV, Sumaroka AM, Ramprasad VL, Herrera W, Windsor EA, Schwartz SB, Russell RC, Roman AJ, Inglehearn CF, Kumaramanickavel G, Stone EM, Fishman GA, Jacobson SG. CERKL mutations cause an autosomal recessive cone-rod dystrophy with inner retinopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50(12):5944–5954. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-3982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali RR, Sarra GM, Stephens C, Alwis MD, Bainbridge JW, Munro PM, Fauser S, Reichel MB, Kinnon C, Hunt DM, Bhattacharya SS, Thrasher AJ. Restoration of photoreceptor ultrastructure and function in retinal degeneration slow mice by gene therapy. Nat Genet. 2000;25(3):306–310. doi: 10.1038/77068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez BV, Vithana EN, Yang Z, Koh AH, Yeung K, Yong V, Shandro HJ, Chen Y, Kolatkar P, Palasingam P. Identification and characterization of a novel mutation in the carbonic anhydrase IV gene that causes retinitis pigmentosa. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48(8):3459–3468. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansar M, Santos-Cortez RL, Saqib MA, Zulfiqar F, Lee K, Ashraf NM, Ullah E, Wang X, Sajid S, Khan FS, Amin-ud-Din M, University of Washington Center for Mendelian G. Smith JD, Shendure J, Bamshad MJ, Nickerson DA, Hameed A, Riazuddin S, Ahmed ZM, Ahmad W, Leal SM. Mutation of ATF6 causes autosomal recessive achromatopsia. Hum Genet. 2015;134(9):941–950. doi: 10.1007/s00439-015-1571-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ardell MD, Bedsole DL, Schoborg RV, Pittler SJ. Genomic organization of the human rod photoreceptor cGMP-gated cation channel beta-subunit gene. Gene. 2000;245(2):311–318. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(00)00023-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astuto LM, Bork JM, Weston MD, Askew JW, Fields RR, Orten DJ, Ohliger SJ, Riazuddin S, Morell RJ, Khan S, Riazuddin S, Kremer H, van Hauwe P, Moller CG, Cremers CW, Ayuso C, Heckenlively JR, Rohrschneider K, Spandau U, Greenberg J, Ramesar R, Reardon W, Bitoun P, Millan J, Legge R, Friedman TB, Kimberling WJ. CDH23 mutation and phenotype heterogeneity: a profile of 107 diverse families with Usher syndrome and nonsyndromic deafness. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;71(2):262–275. doi: 10.1086/341558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Audo I, Bujakowska K, Mohand-Said S, Lancelot ME, Moskova-Doumanova V, Waseem NH, Antonio A, Sahel JA, Bhattacharya SS, Zeitz C. Prevalence and novelty of PRPF31 mutations in French autosomal dominant rod-cone dystrophy patients and a review of published reports. BMC Med Genet. 2010;11:145. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-11-145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Audo I, Sahel JA, Mohand-Saïd S, Lancelot ME, Antonio A, Moskova-Doumanova V, Nandrot EF, Doumanov J, Barragan I, Antinolo G. EYS is a major gene for rod-cone dystrophies in France. Hum Mutat. 2010;31(5):E1406–E1435. doi: 10.1002/humu.21249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avila-Fernandez A, Corton M, Nishiguchi KM, Munoz-Sanz N, Benavides-Mori B, Blanco-Kelly F, Riveiro-Alvarez R, Garcia-Sandoval B, Rivolta C, Ayuso C. Identification of an RP1 prevalent founder mutation and related phenotype in Spanish patients with early-onset autosomal recessive retinitis. Ophthalmology. 2012;119(12):2616–2621. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avila-Fernandez A, Perez-Carro R, Corton M, Lopez-Molina MI, Campello L, Garanto A, Fernadez-Sanchez L, Duijkers L, Lopez-Martinez MA, Riveiro-Alvarez R (2015) Whole Exome Sequencing Reveals ZNF408 as a New Gene Associated With Autosomal Recessive Retinitis Pigmentosa with Vitreal Alterations. Human molecular genetics:ddv140 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Azari AA, Aleman TS, Cideciyan AV, Schwartz SB, Windsor EAM, Sumaroka A, Cheung AY, Steinberg JD, Roman AJ, Stone EM. Retinal disease expression in Bardet-Biedl syndrome-1 (BBS1) is a spectrum from maculopathy to retina-wide degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47(11):5004–5010. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badano JL, Ansley SJ, Leitch CC, Lewis RA, Lupski JR, Katsanis N. Identification of a novel Bardet-Biedl syndrome protein, BBS7, that shares structural features with BBS1 and BBS2. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72(3):650–658. doi: 10.1086/368204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bainbridge JW, Smith AJ, Barker SS, Robbie S, Henderson R, Balaggan K, Viswanathan A, Holder GE, Stockman A, Tyler N, Petersen-Jones S, Bhattacharya SS, Thrasher AJ, Fitzke FW, Carter BJ, Rubin GS, Moore AT, Ali RR. Effect of gene therapy on visual function in Leber’s congenital amaurosis. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(21):2231–2239. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandah-Rozenfeld D, Collin RW, Banin E, van den Born LI, Coene KL, Siemiatkowska AM, Zelinger L, Khan MI, Lefeber DJ, Erdinest I, Testa F, Simonelli F, Voesenek K, Blokland EA, Strom TM, Klaver CC, Qamar R, Banfi S, Cremers FP, Sharon D, den Hollander AI. Mutations in IMPG2, encoding interphotoreceptor matrix proteoglycan 2, cause autosomal-recessive retinitis pigmentosa. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;87(2):199–208. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandah-Rozenfeld D, Mizrahi-Meissonnier L, Farhy C, Obolensky A, Chowers I, Pe’er J, Merin S, Ben-Yosef T, Ashery-Padan R, Banin E. Homozygosity mapping reveals null mutations in FAM161A as a cause of autosomal-recessive retinitis pigmentosa. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;87(3):382–391. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bareil C, Hamel CP, Delague V, Arnaud B, Demaille J, Claustres M. Segregation of a mutation in CNGB1 encoding the beta-subunit of the rod cGMP-gated channel in a family with autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa. Hum Genet. 2001;108(4):328–334. doi: 10.1007/s004390100496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barragán I, Abd El-Aziz MM, Borrego S, El-Ashry MF, O’Driscoll C, Bhattacharya SS, Antinolo G. Linkage validation of RP25 using the 10 K genechip array and further refinement of the locus by new linked families. Ann Hum Genet. 2008;72(4):454–462. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.2008.00448.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck BB, Phillips JB, Bartram MP, Wegner J, Thoenes M, Pannes A, Sampson J, Heller R, Gobel H, Koerber F, Neugebauer A, Hedergott A, Nurnberg G, Nurnberg P, Thiele H, Altmuller J, Toliat MR, Staubach S, Boycott KM, Valente EM, Janecke AR, Eisenberger T, Bergmann C, Tebbe L, Wang Y, Wu Y, Fry AM, Westerfield M, Wolfrum U, Bolz HJ. Mutation of POC1B in a severe syndromic retinal ciliopathy. Hum Mutat. 2014;35(10):1153–1162. doi: 10.1002/humu.22618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benaglio P, McGee TL, Capelli LP, Harper S, Berson EL, Rivolta C. Next generation sequencing of pooled samples reveals new SNRNP200 mutations associated with retinitis pigmentosa. Hum Mutat. 2011;32(6):E2246–E2258. doi: 10.1002/humu.21485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger W, Kloeckener-Gruissem B, Neidhardt J. The molecular basis of human retinal and vitreoretinal diseases. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2010;29(5):335–375. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bessant DA, Payne AM, Mitton KP, Wang Q-L, Swain PK, Plant C, Bird AC, Zack DJ, Swaroop A, Bhattacharya SS. A mutation in NRL is associated with autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa. Nat Genet. 1999;21(4):355–356. doi: 10.1038/7678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya SS, Wright AF, Clayton JF, Price WH, Phillips CI, McKeown CME, Jay M, Bird AC, Pearson PL, Southern EM (1984) Close genetic linkage between X-linked retinitis pigmentosa and a restriction fragment length polymorphism identified by recombinant DNA probe L1. 28 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharya G, Miller C, Kimberling WJ, Jablonski MM, Cosgrove D. Localization and expression of usherin: a novel basement membrane protein defective in people with Usher’s syndrome type IIa. Hear Res. 2002;163(1):1–11. doi: 10.1016/S0378-5955(01)00344-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bielas SL, Silhavy JL, Brancati F, Kisseleva MV, Al-Gazali L, Sztriha L, Bayoumi RA, Zaki MS, Abdel-Aleem A, Rosti RO, Kayserili H, Swistun D, Scott LC, Bertini E, Boltshauser E, Fazzi E, Travaglini L, Field SJ, Gayral S, Jacoby M, Schurmans S, Dallapiccola B, Majerus PW, Valente EM, Gleeson JG. Mutations in INPP5E, encoding inositol polyphosphate-5-phosphatase E, link phosphatidyl inositol signaling to the ciliopathies. Nat Genet. 2009;41(9):1032–1036. doi: 10.1038/ng.423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanton SH, Heckenlively JR, Cottingham AW, Friedman J, Sadler LA, Wagner M, Friedman LH, Daiger SP. Linkage mapping of autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa (RP1) to the pericentric region of human chromosome 8. Genomics. 1991;11(4):857–869. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(91)90008-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boon CJ, Klevering BJ, Cremers FP, Zonneveld-Vrieling MN, Theelen T, Den Hollander AI, Hoyng CB (2009) Central areolar choroidal dystrophy. Ophthalmology 116 (4):771–782, 782 e771 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bowne SJ, Sullivan LS, Mortimer SE, Hedstrom L, Zhu J, Spellicy CJ, Gire AI, Hughbanks-Wheaton D, Birch DG, Lewis RA, Heckenlively JR, Daiger SP. Spectrum and frequency of mutations in IMPDH1 associated with autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa and leber congenital amaurosis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47(1):34–42. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowne SJ, Sullivan LS, Koboldt DC, Ding L, Fulton R, Abbott RM, Sodergren EJ, Birch DG, Wheaton DH, Heckenlively JR. Identification of disease-causing mutations in autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa (adRP) using next-generation DNA sequencing. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52(1):494–503. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branham K, Othman M, Brumm M, Karoukis AJ, Atmaca-Sonmez P, Yashar BM, Schwartz SB, Stover NB, Trzupek K, Wheaton D. Mutations in RPGR and RP2 account for 15% of males with simplex retinal degenerative disease. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53(13):8232–8237. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-11025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breuer DK, Musarella M, Swaroop A (2000) Verification and fine mapping of the X-linked retinitis pigmentosa locus RP6. In: Investigative ophthalmology & visual science, vol 4. Assoc Research Vision Ophthalmology Inc 9650 Rockville Pike, Bethesda, MD, 20814–3998 USA, pp S191–S191

- Bujakowska KM, Zhang Q, Siemiatkowska AM, Liu Q, Place E, Falk MJ, Consugar M, Lancelot ME, Antonio A, Lonjou C, Carpentier W, Mohand-Said S, den Hollander AI, Cremers FP, Leroy BP, Gai X, Sahel JA, van den Born LI, Collin RW, Zeitz C, Audo I, Pierce EA. Mutations in IFT172 cause isolated retinal degeneration and Bardet-Biedl syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 2015;24(1):230–242. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess R, Millar ID, Leroy BP, Urquhart JE, Fearon IM, De Baere E, Brown PD, Robson AG, Wright GA, Kestelyn P, Holder GE, Webster AR, Manson FD, Black GC. Biallelic mutation of BEST1 causes a distinct retinopathy in humans. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82(1):19–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai X, Conley SM, Naash MI. RPE65: role in the visual cycle, human retinal disease, and gene therapy. Ophthalmic Genet. 2009;30(2):57–62. doi: 10.1080/13816810802626399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chadderton N, Millington-Ward S, Palfi A, O’Reilly M, Tuohy G, Humphries MM, Li T, Humphries P, Kenna PF, Farrar GJ. Improved retinal function in a mouse model of dominant retinitis pigmentosa following AAV-delivered gene therapy. Mol Ther. 2009;17(4):593–599. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakarova CF, Hims MM, Bolz H, Abu-Safieh L, Patel RJ, Papaioannou MG, Inglehearn CF, Keen TJ, Willis C, Moore AT, Rosenberg T, Webster AR, Bird AC, Gal A, Hunt D, Vithana EN, Bhattacharya SS. Mutations in HPRP3, a third member of pre-mRNA splicing factor genes, implicated in autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11(1):87–92. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakarova CF, Papaioannou MG, Khanna H, Lopez I, Waseem N, Shah A, Theis T, Friedman J, Maubaret C, Bujakowska K, Veraitch B, Abd El-Aziz MM, de Prescott Q, Parapuram SK, Bickmore WA, Munro PM, Gal A, Hamel CP, Marigo V, Ponting CP, Wissinger B, Zrenner E, Matter K, Swaroop A, Koenekoop RK, Bhattacharya SS. Mutations in TOPORS cause autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa with perivascular retinal pigment epithelium atrophy. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81(5):1098–1103. doi: 10.1086/521953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakarova CF, Khanna H, Shah AZ, Patil SB, Sedmak T, Murga-Zamalloa CA, Papaioannou MG, Nagel-Wolfrum K, Lopez I, Munro P. TOPORS, implicated in retinal degeneration, is a cilia-centrosomal protein. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20(5):975–987. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaki M, Airik R, Ghosh AK, Giles RH, Chen R, Slaats GG, Wang H, Hurd TW, Zhou W, Cluckey A, Gee HY, Ramaswami G, Hong CJ, Hamilton BA, Cervenka I, Ganji RS, Bryja V, Arts HH, van Reeuwijk J, Oud MM, Letteboer SJ, Roepman R, Husson H, Ibraghimov-Beskrovnaya O, Yasunaga T, Walz G, Eley L, Sayer JA, Schermer B, Liebau MC, Benzing T, Le Corre S, Drummond I, Janssen S, Allen SJ, Natarajan S, O’Toole JF, Attanasio M, Saunier S, Antignac C, Koenekoop RK, Ren H, Lopez I, Nayir A, Stoetzel C, Dollfus H, Massoudi R, Gleeson JG, Andreoli SP, Doherty DG, Lindstrad A, Golzio C, Katsanis N, Pape L, Abboud EB, Al-Rajhi AA, Lewis RA, Omran H, Lee EY, Wang S, Sekiguchi JM, Saunders R, Johnson CA, Garner E, Vanselow K, Andersen JS, Shlomai J, Nurnberg G, Nurnberg P, Levy S, Smogorzewska A, Otto EA, Hildebrandt F. Exome capture reveals ZNF423 and CEP164 mutations, linking renal ciliopathies to DNA damage response signaling. Cell. 2012;150(3):533–548. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang B, Hawes NL, Hurd RE, Davisson MT, Nusinowitz S, Heckenlively JR. Retinal degeneration mutants in the mouse. Vision Res. 2002;42(4):517–525. doi: 10.1016/S0042-6989(01)00146-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang B, Khanna H, Hawes N, Jimeno D, He S, Lillo C, Parapuram SK, Cheng H, Scott A, Hurd RE. In-frame deletion in a novel centrosomal/ciliary protein CEP290/NPHP6 perturbs its interaction with RPGR and results in early-onset retinal degeneration in the rd16 mouse. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15(11):1847–1857. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Liu Y, Sheng X, Tam PO, Zhao K, Chen X, Rong W, Liu Y, Liu X, Pan X, Chen LJ, Zhao Q, Vollrath D, Pang CP, Zhao C. PRPF4 mutations cause autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23(11):2926–2939. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang AP, Nishimura D, Searby C, Elbedour K, Carmi R, Ferguson AL, Secrist J, Braun T, Casavant T, Stone EM. Comparative genomic analysis identifies an ADP-ribosylation factor–like gene as the cause of Bardet-Biedl syndrome (BBS3) Am J Hum Genet. 2004;75(3):475–484. doi: 10.1086/423903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang AP, Beck JS, Yen H-J, Tayeh MK, Scheetz TE, Swiderski RE, Nishimura DY, Braun TA, Kim K-YA, Huang J. Homozygosity mapping with SNP arrays identifies TRIM32, an E3 ubiquitin ligase, as a Bardet-Biedl syndrome gene (BBS11) Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2006;103(16):6287–6292. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600158103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cideciyan AV, Aleman TS, Boye SL, Schwartz SB, Kaushal S, Roman AJ, Pang JJ, Sumaroka A, Windsor EA, Wilson JM, Flotte TR, Fishman GA, Heon E, Stone EM, Byrne BJ, Jacobson SG, Hauswirth WW. Human gene therapy for RPE65 isomerase deficiency activates the retinoid cycle of vision but with slow rod kinetics. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(39):15112–15117. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807027105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coene KLM, Roepman R, Doherty D, Afroze B, Kroes HY, Letteboer SJF, Ngu LH, Budny B, van Wijk E, Gorden NT. OFD1 Is Mutated in X-Linked Joubert Syndrome and Interacts with LCA5-Encoded Lebercilin. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;85(4):465–481. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collin RW, Nikopoulos K, Dona M, Gilissen C, Hoischen A, Boonstra FN, Poulter JA, Kondo H, Berger W, Toomes C. ZNF408 is mutated in familial exudative vitreoretinopathy and is crucial for the development of zebrafish retinal vasculature. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2013;110(24):9856–9861. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1220864110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conte I, Hadfield KD, Barbato S, Carrella S, Pizzo M, Bhat RS, Carissimo A, Karali M, Porter LF, Urquhart J. MiR-204 is responsible for inherited retinal dystrophy associated with ocular coloboma. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2015;112(25):E3236–E3245. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1401464112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coppieters F, Leroy BP, Beysen D, Hellemans J, De Bosscher K, Haegeman G, Robberecht K, Wuyts W, Coucke PJ, De Baere E. Recurrent mutation in the first zinc finger of the orphan nuclear receptor NR2E3 causes autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81(1):147–157. doi: 10.1086/518426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daiger SP, Bowne SJ, Sullivan LS. Perspective on genes and mutations causing retinitis pigmentosa. Arch Ophthalmol. 2007;125(2):151–158. doi: 10.1001/archopht.125.2.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daiger SP, Sullivan LS, Bowne SJ, Birch DG, Heckenlively JR, Pierce EA, Weinstock GM. Targeted high-throughput DNA sequencing for gene discovery in retinitis pigmentosa. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2010;664:325–331. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-1399-9_37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson AE, Millar ID, Urquhart JE, Burgess-Mullan R, Shweikh Y, Parry N, O’Sullivan J, Maher GJ, McKibbin M, Downes SM, Lotery AJ, Jacobson SG, Brown PD, Black GC, Manson FD. Missense mutations in a retinal pigment epithelium protein, bestrophin-1, cause retinitis pigmentosa. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;85(5):581–592. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson AE, Schwarz N, Zelinger L, Stern-Schneider G, Shoemark A, Spitzbarth B, Gross M, Laxer U, Sosna J, Sergouniotis PI, Waseem NH, Wilson R, Kahn RA, Plagnol V, Wolfrum U, Banin E, Hardcastle AJ, Cheetham ME, Sharon D, Webster AR. Mutations in ARL2BP, encoding ADP-ribosylation-factor-like 2 binding protein, cause autosomal-recessive retinitis pigmentosa. Am J Hum Genet. 2013;93(2):321–329. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downs LM, Bell JS, Freeman J, Hartley C, Hayward LJ, Mellersh CS. Late-onset progressive retinal atrophy in the Gordon and Irish Setter breeds is associated with a frameshift mutation in C2orf71. Anim Genet. 2013;44(2):169–177. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2052.2012.02379.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dryja TP, Hahn LB, Cowley GS, McGee TL, Berson EL. Mutation spectrum of the rhodopsin gene among patients with autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88(20):9370–9374. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.20.9370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dryja TP, Berson EL, Rao VR, Oprian DD. Heterozygous missense mutation in the rhodopsin gene as a cause of congenital stationary night blindness. Nat Genet. 1993;4(3):280–283. doi: 10.1038/ng0793-280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dryja TP, Finn JT, Peng YW, McGee TL, Berson EL, Yau KW. Mutations in the gene encoding the alpha subunit of the rod cGMP-gated channel in autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92(22):10177–10181. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.22.10177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dryja TP, Hahn LB, Kajiwara K, Berson EL. Dominant and digenic mutations in the peripherin/RDS and ROM1 genes in retinitis pigmentosa. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1997;38(10):1972–1982. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dryja TP, Rucinski DE, Chen SH, Berson EL. Frequency of mutations in the gene encoding the alpha subunit of rod cGMP-phosphodiesterase in autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999;40(8):1859–1865. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durlu YK, Koroglu C, Tolun A. Novel recessive cone-rod dystrophy caused by POC1B mutation. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2014;132(10):1185–1191. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2014.1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dvir L, Srour G, Abu-Ras R, Miller B, Shalev SA, Ben-Yosef T. Autosomal-recessive early-onset retinitis pigmentosa caused by a mutation in PDE6G, the gene encoding the gamma subunit of rod cGMP phosphodiesterase. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;87(2):258–264. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebermann I, Lopez I, Bitner-Glindzicz M, Brown C, Koenekoop RK, Bolz HJ. Deafblindness in French Canadians from Quebec: a predominant founder mutation in the USH1C gene provides the first genetic link with the Acadian population. Genome Biol. 2007;8(4):R47. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-4-r47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebermann I, Scholl HPN, Issa PC, Becirovic E, Lamprecht J, Jurklies B, Millán JM, Aller E, Mitter D, Bolz H. A novel gene for Usher syndrome type 2: mutations in the long isoform of whirlin are associated with retinitis pigmentosa and sensorineural hearing loss. Hum Genet. 2007;121(2):203–211. doi: 10.1007/s00439-006-0304-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebermann I, Wiesen MHJ, Zrenner E, Lopez I, Pigeon R, Kohl S, Löwenheim H, Koenekoop RK, Bolz HJ. GPR98 mutations cause Usher syndrome type 2 in males. J Med Genet. 2009;46(4):277–280. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2008.059626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichers ER, Green JS, Stockton DW, Jackman CS, Whelan J, McNamara J, Johnson GJ, Lupski JR, Katsanis N. Newfoundland rod-cone dystrophy, an early-onset retinal dystrophy, is caused by splice-junction mutations in RLBP1. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;70(4):955–964. doi: 10.1086/339688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberger T, Slim R, Mansour A, Nauck M, Nürnberg G, Nürnberg P, Decker C, Dafinger C, Ebermann I, Bergmann C. Targeted next-generation sequencing identifies a homozygous nonsense mutation in ABHD12, the gene underlying PHARC, in a family clinically diagnosed with Usher syndrome type 3. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2012;7(1):59. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-7-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Shamieh S, Neuillé M, Terray A, Orhan E, Condroyer C, Démontant V, Michiels C, Antonio A, Boyard F, Lancelot M-E. Whole-exome sequencing identifies KIZ as a ciliary gene associated with autosomal-recessive rod-cone dystrophy. Am J Hum Genet. 2014;94(4):625–633. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Asrag ME, Sergouniotis PI, McKibbin M, Plagnol V, Sheridan E, Waseem N, Abdelhamed Z, McKeefry D, Van Schil K, Poulter JA, Consortium UKIRD. Johnson CA, Carr IM, Leroy BP, De Baere E, Inglehearn CF, Webster AR, Toomes C, Ali M. Biallelic mutations in the autophagy regulator DRAM2 cause retinal dystrophy with early macular involvement. Am J Hum Genet. 2015;96(6):948–954. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2015.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escher P, Gouras P, Roduit R, Tiab L, Bolay S, Delarive T, Chen S, Tsai CC, Hayashi M, Zernant J. Mutations in NR2E3 can cause dominant or recessive retinal degenerations in the same family. Hum Mutat. 2009;30(3):342–351. doi: 10.1002/humu.20858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estrada-Cuzcano A, Neveling K, Kohl S, Banin E, Rotenstreich Y, Sharon D, Falik-Zaccai TC, Hipp S, Roepman R, Wissinger B, Letteboer SJ, Mans DA, Blokland EA, Kwint MP, Gijsen SJ, van Huet RA, Collin RW, Scheffer H, Veltman JA, Zrenner E, den Hollander AI, Klevering BJ, Cremers FP. Mutations in C8orf37, encoding a ciliary protein, are associated with autosomal-recessive retinal dystrophies with early macular involvement. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;90(1):102–109. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari S, Di Iorio E, Barbaro V, Ponzin D, Sorrentino FS, Parmeggiani F. Retinitis pigmentosa: genes and disease mechanisms. Curr Genomics. 2011;12(4):238–249. doi: 10.2174/138920211795860107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field LL, Heckenlively JR, Sparkes RS, Garcia CA, Farson C, Zedalis D, Sparkes MC, Crist M, Tideman S, Spence MA. Linkage analysis of five pedigrees affected with typical autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa. J Med Genet. 1982;19(4):266–270. doi: 10.1136/jmg.19.4.266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fingert JH, Oh K, Chung M, Scheetz TE, Andorf JL, Johnson RM, Sheffield VC, Stone EM. Association of a novel mutation in the retinol dehydrogenase 12 (RDH12) gene with autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126(9):1301–1307. doi: 10.1001/archopht.126.9.1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiskerstrand T, H’mida-Ben Brahim D, Johansson S, M’zahem A, Haukanes BI, Drouot N, Zimmermann J, Cole AJ, Vedeler C, Bredrup C. Mutations in ABHD12 cause the neurodegenerative disease PHARC: an inborn error of endocannabinoid metabolism. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;87(3):410–417. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman JS, Ray JW, Waseem N, Johnson K, Brooks MJ, Hugosson T, Breuer D, Branham KE, Krauth DS, Bowne SJ, Sullivan LS, Ponjavic V, Granse L, Khanna R, Trager EH, Gieser LM, Hughbanks-Wheaton D, Cojocaru RI, Ghiasvand NM, Chakarova CF, Abrahamson M, Goring HH, Webster AR, Birch DG, Abecasis GR, Fann Y, Bhattacharya SS, Daiger SP, Heckenlively JR, Andreasson S, Swaroop A. Mutations in a BTB-Kelch protein, KLHL7, cause autosomal-dominant retinitis pigmentosa. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;84(6):792–800. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs D, Kitamoto J, Williams DS. Abnormal phagocytosis by retinal pigmented epithelium that lacks myosin VIIa, the Usher syndrome 1B protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2003;100(11):6481–6486. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1130432100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs D, Azarian SM, Lillo C, Kitamoto J, Klomp AE, Steel KP, Libby RT, Williams DS. Role of myosin VIIa and Rab27a in the motility and localization of RPE melanosomes. J Cell Sci. 2004;117(Pt 26):6473–6483. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gieser L, Fujita R, Göring HH, Ott J, Hoffman DR, Cideciyan AV, Birch DG, Jacobson SG, Swaroop A. A novel locus (RP24) for X-linked retinitis pigmentosa maps to Xq26-27. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;63(5):1439–1447. doi: 10.1086/302121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie RL, Urquhart J, Lovell SC, Biswas S, Parry NR, Schorderet DF, Lloyd IC, Clayton-Smith J, Black GC. Abrogation of HMX1 function causes rare oculoauricular syndrome associated with congenital cataract, anterior segment dysgenesis, and retinal dystrophy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015;56(2):883–891. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-15861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gire AI, Sullivan LS, Bowne SJ, Birch DG, Hughbanks-Wheaton D, Heckenlively JR, Daiger SP. The Gly56Arg mutation in NR2E3 accounts for 1–2% of autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa. Mol Vis. 2007;13:1970–1975. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goliath R, Shugart Y, Janssens P, Weissenbach J, Beighton P, Ramasar R, Greenberg J. Fine localization of the locus for autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa on chromosome 17p. Am J Hum Genet. 1995;57(4):962–965. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorbatyuk MS, Knox T, LaVail MM, Gorbatyuk OS, Noorwez SM, Hauswirth WW, Lin JH, Muzyczka N, Lewin AS. Restoration of visual function in P23H rhodopsin transgenic rats by gene delivery of BiP/Grp78. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(13):5961–5966. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911991107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin CA, Ding CL, Jabs EW, Hawkins AL, Li X, Levine MA. Human rod cGMP-gated cation channel gene maps to 4p12-centromere by chromosomal in situ hybridization. Genomics. 1993;16(1):302. doi: 10.1006/geno.1993.1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grover S, Fishman GA, Anderson RJ, Tozatti MS, Heckenlively JR, Weleber RG, Edwards AO, Brown J., Jr Visual acuity impairment in patients with retinitis pigmentosa at age 45 years or older. Ophthalmology. 1999;106(9):1780–1785. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(99)90342-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haer-Wigman L, Newman H, Leibu R, Bax NM, Baris HN, Rizel L, Banin E, Massarweh A, Roosing S, Lefeber DJ (2015) Non-syndromic retinitis pigmentosa due to mutations in the mucopolysaccharidosis type IIIC gene, heparan-alpha-glucosaminide N-acetyltransferase (HGSNAT). Human molecular genetics:ddv118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hamel C. Retinitis pigmentosa. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2006;1:40. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-1-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanein S, Perrault I, Gerber S, Tanguy G, Barbet F, Ducroq D, Calvas P, Dollfus H, Hamel C, Lopponen T. Leber congenital amaurosis: comprehensive survey of the genetic heterogeneity, refinement of the clinical definition, and genotype–phenotype correlations as a strategy for molecular diagnosis. Hum Mutat. 2004;23(4):306–317. doi: 10.1002/humu.20010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardcastle AJ, Thiselton DL, Van Maldergem L, Saha BK, Jay M, Plant C, Taylor R, Bird AC, Bhattacharya S. Mutations in the RP2 gene cause disease in 10% of families with familial X-linked retinitis pigmentosa assessed in this study. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;64(4):1210. doi: 10.1086/302325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartong DT, Berson EL, Dryja TP. Retinitis pigmentosa. Lancet. 2006;368(9549):1795–1809. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69740-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartong DT, Dange M, McGee TL, Berson EL, Dryja TP, Colman RF. Insights from retinitis pigmentosa into the roles of isocitrate dehydrogenases in the Krebs cycle. Nat Genet. 2008;40(10):1230–1234. doi: 10.1038/ng.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heng HH, Wang A, Hu J. Mapping of the human HPRP3 and HPRP4 genes encoding U4/U6-associated splicing factors to chromosomes 1q21.1 and 9q31-q33. Genomics. 1998;48(2):273–275. doi: 10.1006/geno.1997.5181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heon E, Westall C, Carmi R, Elbedour K, Panton C, Mackeen L, Stone EM, Sheffield VC. Ocular phenotypes of three genetic variants of Bardet-Biedl syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2005;132A(3):283–287. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilgert N, Kahrizi K, Dieltjens N, Bazazzadegan N, Najmabadi H, Smith RJH, Van Camp G. A large deletion in GPR98 causes type IIC Usher syndrome in male and female members of an Iranian family. J Med Genet. 2009;46(4):272–276. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2008.060947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]