Abstract

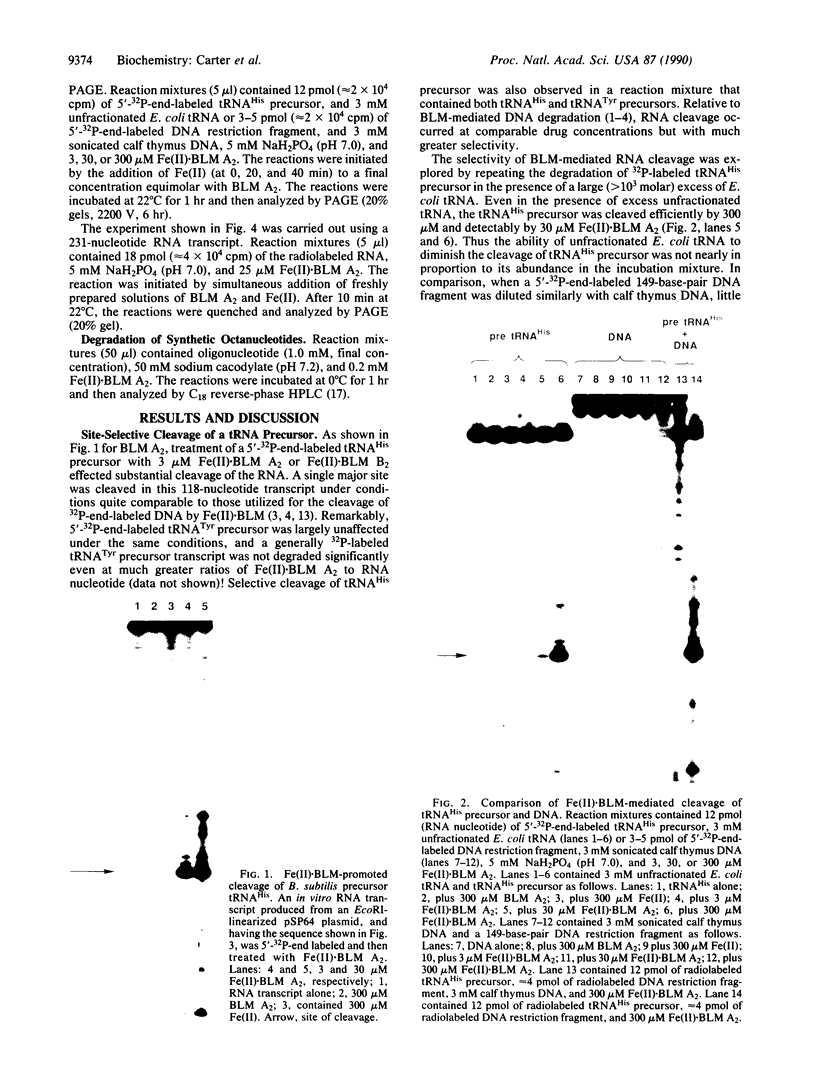

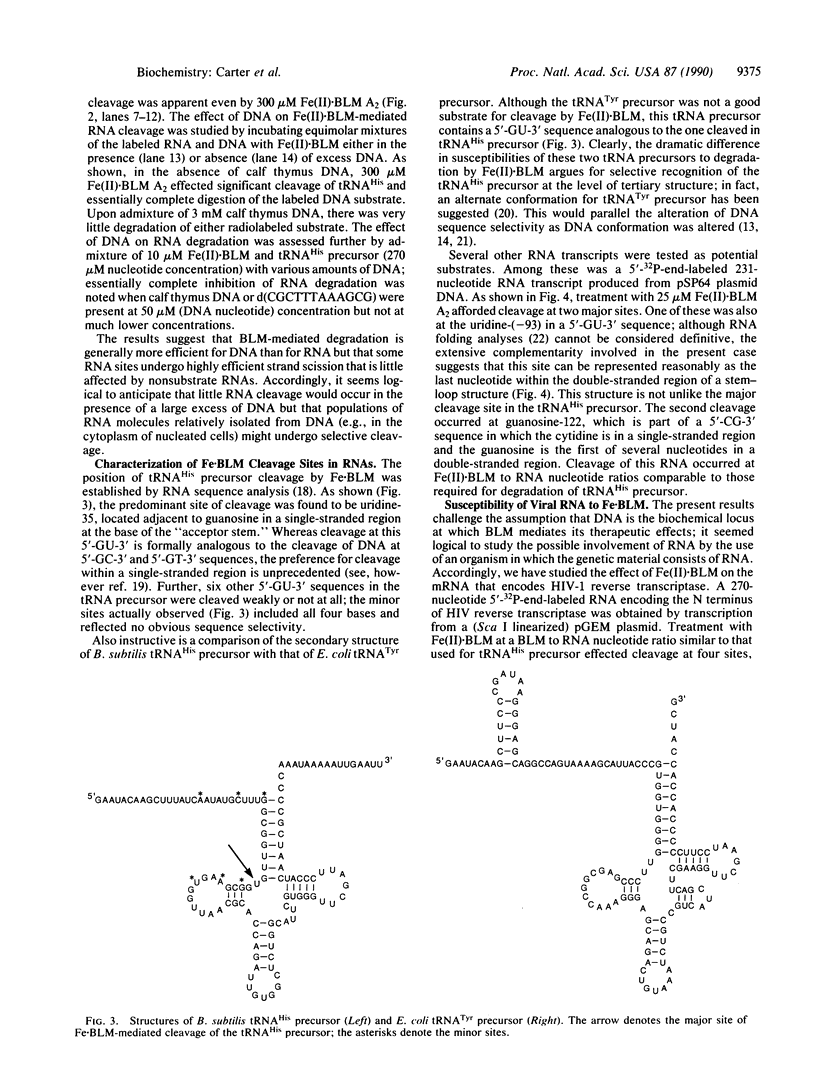

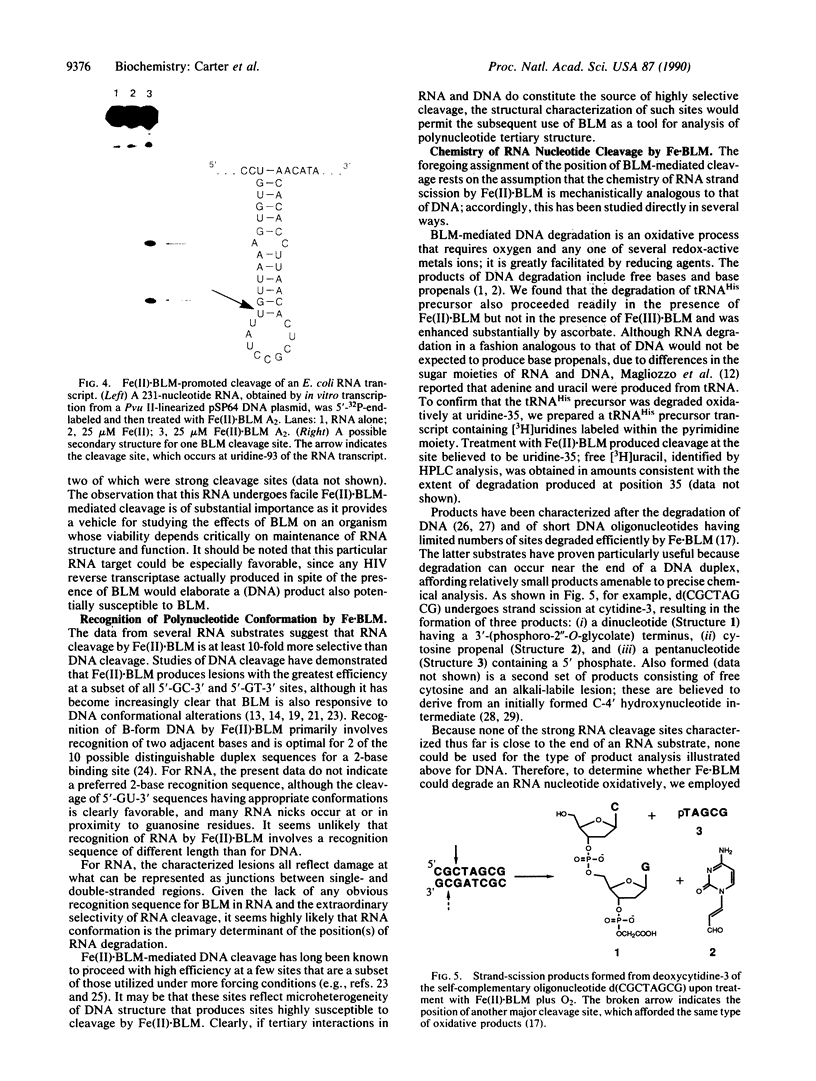

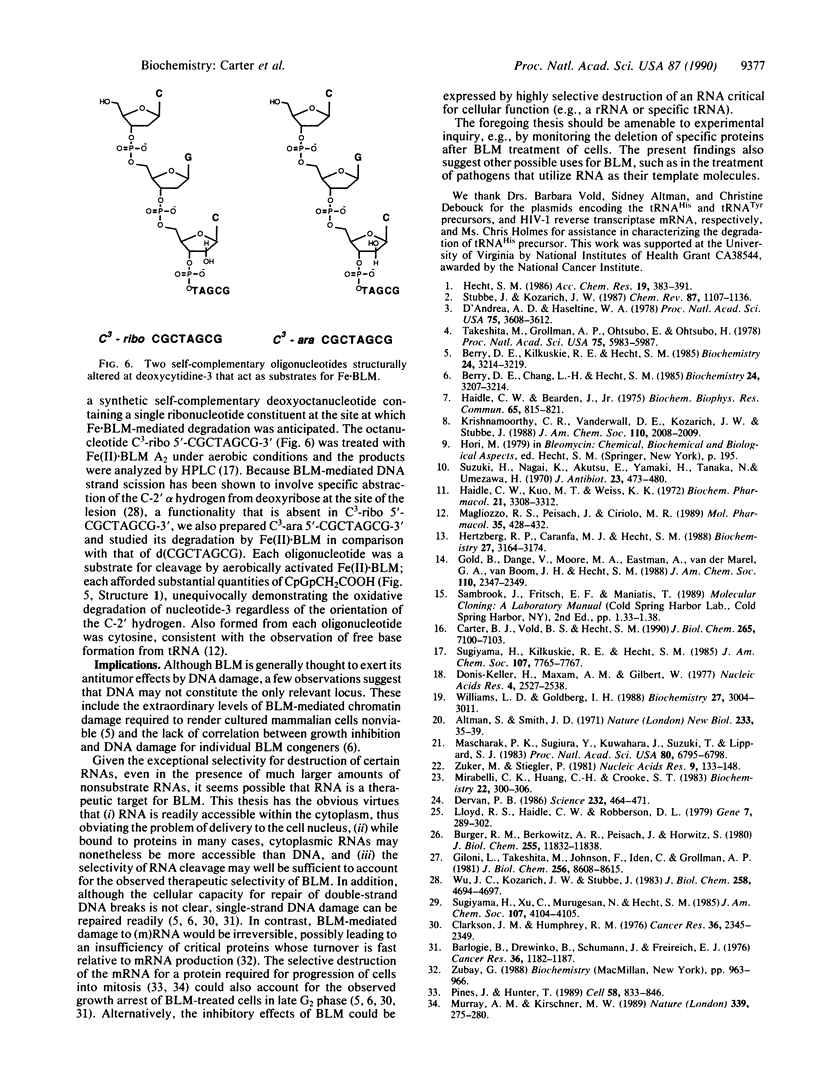

Bleomycin is an antitumor agent whose activity has long been thought to derive from its ability to degrade DNA. Recent findings suggest that cellular RNA may be a therapeutically relevant locus. At micromolar concentrations, Fe(II)-bleomycin readily cleaved a Bacillus subtilis tRNAHis precursor in a highly selective fashion, but Escherichia coli tRNA(Tyr) precursor was largely unaffected even under more forcing conditions. Other substrates included an RNA transcript encoding a large segment of the reverse transcriptase from human immunodeficiency virus 1. RNA cleavage was oxidative, approximately 10-fold more selective than DNA cleavage, and largely unaffected by nonsubstrate RNAs. RNA sequence analysis suggested recognition of RNA tertiary structure, rather than recognition of specific sequences; subsets of nucleotides at the junction of single- and double-stranded regions were especially susceptible to cleavage. The ready accessibility of cellular RNAs to xenobiotic agents, the high selectivity of bleomycin action on RNAs, and the paucity of mechanisms for RNA repair suggest that RNA may be a therapeutically relevant target for bleomycin.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Altman S., Smith J. D. Tyrosine tRNA precursor molecule polynucleotide sequence. Nat New Biol. 1971 Sep 8;233(36):35–39. doi: 10.1038/newbio233035a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlogie B., Drewinko B., Schumann J., Freireich E. J. Pulse cytophotometric analysis of cell cycle perturbation with bleomycin in vitro. Cancer Res. 1976 Mar;36(3):1182–1187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry D. E., Chang L. H., Hecht S. M. DNA damage and growth inhibition in cultured human cells by bleomycin congeners. Biochemistry. 1985 Jun 18;24(13):3207–3214. doi: 10.1021/bi00334a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry D. E., Kilkuskie R. E., Hecht S. M. DNA damage induced by bleomycin in the presence of dibucaine is not predictive of cell growth inhibition. Biochemistry. 1985 Jun 18;24(13):3214–3219. doi: 10.1021/bi00334a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger R. M., Berkowitz A. R., Peisach J., Horwitz S. B. Origin of malondialdehyde from DNA degraded by Fe(II) x bleomycin. J Biol Chem. 1980 Dec 25;255(24):11832–11838. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter B. J., Vold B. S., Hecht S. M. Control of the position of RNase P-mediated transfer RNA precursor processing. J Biol Chem. 1990 May 5;265(13):7100–7103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarkson J. M., Humphrey R. M. The significance of DNA damage in the cell cycle sensitivity of Chinese hamster ovary cells to bleomycin. Cancer Res. 1976 Jul;36(7 Pt 1):2345–2349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Andrea A. D., Haseltine W. A. Sequence specific cleavage of DNA by the antitumor antibiotics neocarzinostatin and bleomycin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1978 Aug;75(8):3608–3612. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.8.3608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dervan P. B. Design of sequence-specific DNA-binding molecules. Science. 1986 Apr 25;232(4749):464–471. doi: 10.1126/science.2421408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donis-Keller H., Maxam A. M., Gilbert W. Mapping adenines, guanines, and pyrimidines in RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1977 Aug;4(8):2527–2538. doi: 10.1093/nar/4.8.2527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giloni L., Takeshita M., Johnson F., Iden C., Grollman A. P. Bleomycin-induced strand-scission of DNA. Mechanism of deoxyribose cleavage. J Biol Chem. 1981 Aug 25;256(16):8608–8615. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haidle C. W., Bearden J., Jr Effect of bleomycin on an RNA-DNA hybrid. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1975 Aug 4;65(3):815–821. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(75)80458-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haidle C. W., Kuo M. T., Weiss K. K. Nucleic acid--specificity of bleomycin. Biochem Pharmacol. 1972 Dec 15;21(24):3308–3312. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(72)90096-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertzberg R. P., Caranfa M. J., Hecht S. M. Degradation of structurally modified DNAs by bleomycin group antibiotics. Biochemistry. 1988 May 3;27(9):3164–3174. doi: 10.1021/bi00409a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd R. S., Haidle C. W., Robberson D. L. Site specificity of bleomycin-mediated single-strand scissions and alkali-labile damage in duplex DNA. Gene. 1979 Nov;7(3-4):289–302. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(79)90049-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magliozzo R. S., Peisach J., Ciriolo M. R. Transfer RNA is cleaved by activated bleomycin. Mol Pharmacol. 1989 Apr;35(4):428–432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mascharak P. K., Sugiura Y., Kuwahara J., Suzuki T., Lippard S. J. Alteration and activation of sequence-specific cleavage of DNA by bleomycin in the presence of the antitumor drug cis-diamminedichloroplatinum(II). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1983 Nov;80(22):6795–6798. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.22.6795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirabelli C. K., Huang C. H., Crooke S. T. Role of deoxyribonucleic acid topology in altering the site/sequence specificity of cleavage of deoxyribonucleic acid by bleomycin and talisomycin. Biochemistry. 1983 Jan 18;22(2):300–306. doi: 10.1021/bi00271a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray A. W., Kirschner M. W. Cyclin synthesis drives the early embryonic cell cycle. Nature. 1989 May 25;339(6222):275–280. doi: 10.1038/339275a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pines J., Hunter T. Isolation of a human cyclin cDNA: evidence for cyclin mRNA and protein regulation in the cell cycle and for interaction with p34cdc2. Cell. 1989 Sep 8;58(5):833–846. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90936-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki H., Nagai K., Akutsu E., Yamaki H., Tanaka N. On the mechanism of action of bleomycin. Strand scission of DNA caused by bleomycin and its binding to DNA in vitro. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1970 Oct;23(10):473–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeshita M., Grollman A. P., Ohtsubo E., Ohtsubo H. Interaction of bleomycin with DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1978 Dec;75(12):5983–5987. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.12.5983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams L. D., Goldberg I. H. Selective strand scission by intercalating drugs at DNA bulges. Biochemistry. 1988 Apr 19;27(8):3004–3011. doi: 10.1021/bi00408a051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J. C., Kozarich J. W., Stubbe J. The mechanism of free base formation from DNA by bleomycin. A proposal based on site specific tritium release from Poly(dA.dU). J Biol Chem. 1983 Apr 25;258(8):4694–4697. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuker M., Stiegler P. Optimal computer folding of large RNA sequences using thermodynamics and auxiliary information. Nucleic Acids Res. 1981 Jan 10;9(1):133–148. doi: 10.1093/nar/9.1.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]