Abstract

This study aimed to genetically characterize two fully-sequenced novel IncFII-type multidrug resistant (MDR) plasmids, p0716-KPC and p12181-KPC, recovered from two different clinical Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates. p0716-KPC and p12181-KPC had a very similar genomic content. The backbones of p0716-KPC/p12181-KPC contained two different replicons (belonging to a novel IncFII subtype and the Rep_3 family), the IncFIIK and IncFIIY maintenance regions, and conjugal transfer gene sets from IncFIIK-type plasmids and unknown origins. p0716-KPC and p12181-KPC carried similar three accessory resistance regions, namely ΔTn6209, a MDR region, and the bla KPC-2 region. Resistance genes bla KPC-2, mph(A), strAB, aacC2, qacEΔ1, sul1, sul2, and dfrA25, which are associated with transposons, integrons, and insertion sequence-based mobile units, were located in these accessory regions. p0716-KPC carried two additional resistance genes: aphA1a and bla TEM-1. Together, our analyses showed that p0716-KPC and p12181-KPC belong to a novel IncFII subtype and display a complex chimeric nature, and that the carbapenem resistance gene bla KPC-2 coexists with a lot of additional resistance genes on these two plasmids.

Introduction

Carbapenemases can be divided into three main categories: Ambler class A serine β-lactamases, class B metallo-β-lactamases, and the class D OXA group. Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC) is a class A β-lactamase that was initially discovered in the USA in 1996. It has since disseminated worldwide among Enterobacteriaceae, Pseudomonas, and Acinetobacter species, with K. pneumoniae being the most common species harboring bla KPC genes1, 2. KPC-producing bacteria are becoming endemic in certain hospitals, and are responsible for increasing numbers of outbreaks in healthcare facilities. KPC confers resistance or decreased susceptibility to almost all β-lactams, and KPC-producing isolates are often resistant to many other non-β-lactam drugs because of the co-occurrence of bla KPC with other classes of resistance gene. This multidrug resistance (MDR) leaves few available options for antimicrobial treatment, and thereby results in high mortality rates3.

The bla KPC genes have been found on IncFII-related plasmids such as pKPHS2 (GenBank accession number CP003224)4 and pKPC-LK30 (accession number KC405622)5 from K. pneumoniae. Conjugative IncFIIK plasmid pKPHS2 has the core IncFIIK backbone regions for plasmid replication (repA IncFIIK5), maintenance (parAB, stbAB, umuCD, psiAB, ardAB, and relBE), and conjugal transfer (tra and trb), as well as additional replication genes repA2 IncFIB-like and repB Rep_3-family/pKPHS2. pKPC-LK30 lacks plasmid conjugal transfer regions, which might result in it being nonconjugative. The pKPC-LK30 backbone is composed of a single replication gene, repB Rep_3-family/pKPHS2, a 36-kb IncFIIY-type maintenance region homologous to a portion of the pKPHS2 maintenance regions, and a 16-kb IncFIIY-type plasmid maintenance region found in pKOX_NDM1, which is a bla NDM-1-carrying IncFIIY-type plasmid from Klebsiella oxytoca isolated in China6. Although highly unusual, these backbone components can function together to promote the replication and stability of pKPC-LK30 in K. pneumoniae.

This work presents the complete sequences of two novel MDR plasmids, p0716-KPC and p12181-KPC, from K. pneumoniae strains isolated from China (Table 1). The two closely related plasmids belong to a novel IncFII subtype, and displayed a complex chimeric nature with respect to both the plasmid backbone (closely related to pKPHS2 and pKPC-LK30) and the accessory resistance regions. Co-occurrence of bla KPC-2 (carbapenem resistance) with mph(A) (macrolide resistance), strAB and aacC2 (aminoglycoside resistance), qacEΔ1 (quaternary ammonium compound resistance), sul1 and sul2 (sulphonamide resistance), and dfrA25 (trimethoprim resistance) was observed in both plasmids.

Table 1.

Major features of p0716-KPC and p12181-KPC and their antibiotic resistance genes and host bacteria.

| Category | Plasmid | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p0716-KPC | p12181-KPC | |||||

| Accessory resistance regions | ∆Tn6029 | MDR region | bla KPC-2 region | ∆Tn6029 | MDR region | bla KPC-2 region |

| Resistance genes | strAB, and sul2 | aphA1a, ΔtmrB, aacC2, mph(A), sul1, qacEΔ1, and dfrA25 | bla TEM-1, and bla KPC-2 | strAB, and sul2 | mph(A), sul1, qacEΔ1, and dfrA25 | ΔtmrB, aacC2, and bla KPC-2 |

| Host bacterium | K. pneumoniae 0716 | K. pneumoniae 12181 | ||||

| Bacterial isolation | Recovered from ascitic fluid from Patient 1 in Hospital 1 | Recovered from sputum from Patient 2 in Hospital 2 | ||||

Results

Clinical cases

Patient 1 was a 59-year-old male admitted to Hospital 1 in October 2013, where he was diagnosed with a cardiac carcinoma. Nosocomial intra-abdominal infection occurred, and K. pneumoniae 0716 was isolated from ascitic fluid. The patient received intravenous administration of tigecycline, and the patient’s acute condition significantly improved.

Patient 2 was an 87-year-old man with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic bronchitis, pulmonary emphysema, coronary heart disease, and pancreatic carcinoma. Acute pancreatitis and peritonitis developed during treatment in Hospital 2 in September 2013. K. pneumoniae 12181 was isolated from a sputum sample, and the patient was treated with intravenous administration of meropenem plus ciprofloxacin. However, treatment was unsuccessful and the patient died.

Strains 0716 and 12181 were resistant to multiple antibiotics, including ampicillin, β-lactamase inhibitors (amoxicillin/clavulanic acid and piperacillin/tazobactam), cephalosporins (cefazolin and ceftriaxone), carbapenems (imipenem and meropenem), aztreonam, macrodantin, fluoroquinolones (ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin), aminoglycosides (amikacin and tobramycin), and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, but remained susceptible to tetracycline (data not shown).

Overview of p0716-KPC and p12181-KPC

PCR screening and sequencing indicated the presence of bla KPC-2, but none of the other carbapenemase genes tested for, in strains 0716 and 12181. The bla KPC markers could be transferred from strains 0716 and 12181 into TOP10 through electroporation, generating the E. coli electroporants 0716-KPC-TOP10 and 12181-KPC-TOP10, respectively. Subsequent high-throughput sequencing indicated that these two electroporants contained the bla KPC-2-carrying plasmids p0716-KPC and p12181-KPC, respectively. p0716-KPC but not p12181-KPC could be transferred from the respective strains 0716 and 12181 into EC600 through conjugation. In the negative control experiments using only the donor or the recipient, no colonies were observed on the agar plates containing indicated antibiotics, excluding the possibility of antibiotic resistance due to spontaneous mutation.

As expected, the resulting E. coli transformants and transconjugant demonstrated class A carbapenemase activity, and were resistant to ampicillin, amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, piperacillin/tazobactam, cefazolin, ceftriaxone, imipenem, meropenem, and aztreonam, but remained susceptible to macrodantin (data not shown).

Genome sequencing confirmed that p0716-KPC and p12181-KPC were circular DNA molecules, 143,538 bp and 140,089 bp in length, with 192 and 188 predicted open reading frames, respectively (Figure S1). The modular structure of each plasmid was composed of the backbone region, as well as multiple separate accessory modules inserted within the backbone (Figure S1). p0716-KPC and p12181-KPC shared 97% query coverage with a maximum nucleotide identity of 99% (Fig. 1).

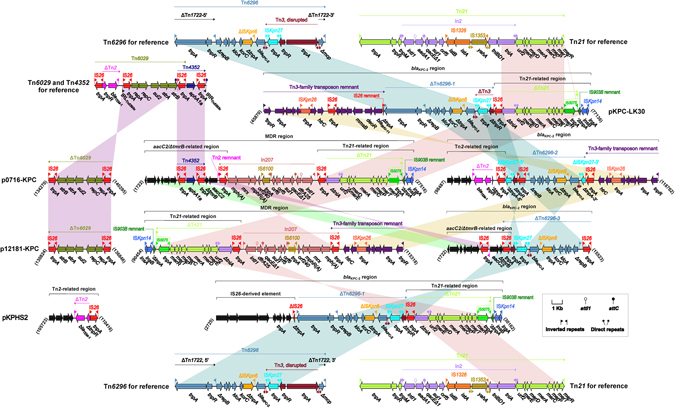

Figure 1.

Linear comparison of sequenced plasmids. Genes are denoted by arrows and are colored based on gene function classification. Shaded regions denote regions of homology (>95% nucleotide similarity). The sequences of p0716-KPC and p12181-KPC were determined in this study, while those of pKPC-LK30 and pKPHS2 are derived from GenBank.

Backbone regions of p0716-KPC and p12181-KPC

Two representative bla KPC-2-carrying plasmids pKPHS2 and pKPC-LK30 were included in the genomic comparison with p0716-KPC and p12181-KPC (Fig. 1). p0716-KPC and p12181-KPC were most closely related to pKPHS2 (67% coverage and 99% nucleotide identity; last accessed on August 15, 2015). pKPC-LK30 was selected because it contains a large plasmid maintenance region that is not found in pKPHS2 but was identified in p0716-KPC and p12181-KPC (see below).

The backbones of p0716-KPC and p12181-KPC were almost identical with respect to genetic content. p0716-KPC and p12181-KPC both contained two novel replicons, including a repB Rep_3-family/p0716-KPC gene and a repA IncFII-family gene, both of which were very different from their counterparts in pKPHS2 and pKPC-LK30. The repA IncFII-family gene was most closely related to the IncFII plasmid pEA49-KPC (accession number KU318419) with a nucleotide identity of 94% (last accessed on December 25, 2016). p0716-KPC and p12181-KPC also contained the complete 16-kb IncFIIY-type pKOX_NDM1 maintenance region, and almost the entire non-redundant IncFIIK-type maintenance region found in both pKPHS2 and pKPC-LK30 (Fig. 1). Compared with pKPHS2 and pKPC-LK30, p0716-KPC and p12181-KPC contained two unique backbone regions: a 5.6-kb plasmid maintenance region connected to the repB Rep_3-family/p0716-KPC gene, and a novel 3.2-kb conjugal transfer region contained the pld gene (conjugal transfer endonuclease). This 3.2-kb region was most closely related (93% query coverage and 98% maximum nucleotide identity; last accessed on December 25, 2016) to the MOBF family plasmid pEA49-KPC (Fig. 1).

p0716-KPC and p12181-KPC belonged to a novel IncFII subtype since it contained a novel repA gene belonging to the IncFII family, together with IncFIIK/IIY-type maintenance regions. Based on the three key regulatory DNA transfer genes traM, traJ, and finO and the ATPase gene traC, all of which encoded key proteins of a type IV secretion system, p0716-KPC and p12181-KPC were assigned into the subgroup A of the IncF/MOBF12 group7.

Accessory regions of p0716-KPC and p12181-KPC

p0716-KPC contained three accessory modules in total, namely ΔTn6029, the MDR region, and the bla KPC-2 region, which were inserted at different sites in the backbone (Fig. 2). ΔTn6029 is a partial fragment of the IS26-based composite transposon Tn6029 8, and comprises a strAB module flanked by two inverted IS26 elements. As initially characterized in the IncHI1 plasmid pSRC27-H, Tn6029 and Tn4352 are two overlapping transposons likely generated from complex recombination events between IS26, Tn2, and Tn5393c 8.

Figure 2.

Organization and alignment of resistance regions. The genetic organization of the resistance regions from p0716-KPC, p12181-KPC, pKPC-LK30, and pKPHS2 is shown, and relevant mobile elements are included for reference. Genes are denoted by arrows and are colored based on gene function classification. Shaded regions denote regions of homology (>95% nucleotide similarity).

The MDR region was further divided into an aacC2/ΔtmrB-related region, In207, and a Tn21-related region. The aacC2/ΔtmrB-related region harbored the aphA1a (aminoglycoside resistance)-carrying Tn4352 8, which lacked target site duplication signals of transposition. Tn4352 was further connected to a region composed of ΔtmrB, aacC2, and a 135-bp Tn2 remnant containing its inverted repeat right (IRR), resulting in truncation of tmrB (tunicamycin resistance). The association of aacC2-tmrB with Tn2 and IS26, as observed in pCTX-M3 and pU302L, constitutes one example of the multifarious aacC2-harboring structures9. In207 was identified in p0716-KPC and p12181-KPC, and is an In4-like integron10 containing a single dfrA25 cassette. Notably, In207 is connected to the macrolide resistance unit IS26-mph(A)-mrx-mphR(A)-IS6100, a structure frequently associated with class 1 integrons9, at its 3ʹ region. This likely occurred through IS6100-mediated recombination, and resulted in deletion of the inverted repeat terminal (IRt). In207 from p0716-KPC and p12181-KPC appeared to be more complete than the prototype In207 (GenBank accession number AB280920), which is only an integron cassette array fragment. The Tn21-related region was organized sequentially as follows: IS26, ∆Tn21, a 288-bp IS903B remnant, and ISKpn14. Tn21, a Tn3-family unit transposon, contained the core transposition module tnpA (transposase)-tnpR (resolvase), tnpM, inserted integron In2, urf2, and the mercuric resistance (mer) operon. The transposon was flanked by 38-bp IRL (inverted repeat left) and IRR sequences, and the In2 insertion was shown to disrupt a presumed ancestral urf2M gene, resulting in urf2 and tnpM 11. The ∆Tn21 element from p0716-KPC was composed of ΔtniA In2, the mer operon, and the IS5075-disrupted IRRTn21. The IS1111-family element IS5075 targets the terminal inverted repeats of the Tn21-subgroup transposons of the Tn3 family12.

The bla KPC-2 region consisted of a Tn2-related region, ΔTn6296-2, and a Tn3-family transposon remnant. Tn6296 (designated in this work) was originally identified in the MDR plasmid pKP04813 from K. pneumoniae, and is generated from the insertion of a core bla KPC-2 genetic platform (∆Tn3:ISKpn27-bla KPC-2 -ΔISKpn6-korC-orf6-klcA-ΔrepB) into Tn1722, resulting in truncation of mcp 14. Various Tn6296 derivatives with deletions, insertions, and rearrangements at different sites, such as ΔTn6296-1 in pKPHS2/pKPC-LK30, ΔTn6296-2 in p0716-KPC, and ΔTn6296-3 in p12181-KPC, have been identified in KPC-encoding plasmids from K. pneumoniae strains isolated in China14. A four-gene cluster coding for proteins of unknown function was located at the 5ʹ end of the Tn2-related region, followed by a partial bla TEM-1 (β-lactam resistance)-carrying Tn2 15 region, plus IS26. The cryptic Tn3-family transposon remnant contained a typical 38-bp IRL element, a core transposition module (tnpA-tnpR), and inserted IS elements ISKpn26 and IS26.

p12181-KPC also contained ΔTn6029, the MDR region, and the bla KPC-2 region, which resembled their counterparts in p0716-KPC. Tn4352 in the MDR region and the Tn2-related region in the bla KPC-2 locus were not found in p12181-KPC. Therefore, p0716-KPC contained two additional resistance genes, aphA1a and bla TEM-1, compared with p12181-KPC. Notably, aphA1a and bla TEM-1 are redundant determinants accounting for resistance to aminoglycosides and β-lactams, respectively, in p0716-KPC. In addition, extensive rearrangement of large fragments was observed not only within, but between the MDR region and the bla KPC-2 region of p12181-KPC relative to p0716-KPC. These rearrangements were likely promoted by IS26-based replicative transposition16 as multiple copies of IS26 were identified in these two accessory regions. p12181-KPC still maintained three small accessory regions: two IS903D copies and group IIB retro-transposable intron S.ma.I1, none of which were found in p0716-KPC. One copy of IS903D was inserted into a region between trbF and trbB, while traV (an essential gene encoding a core protein of type IV secretion system) was disrupted by a second copy, rendering p12181-KPC non-conjugative.

pKPC-LK30 contained a single accessory resistance region (the bla KPC-2 region) containing two antibiotic resistance genes: bla KPC-2 and bla SHV-11 (Fig. 2). pKPHS2 carried two accessory resistance regions, namely the bla KPC-2 region and the Tn2-related region, each of which contained a single antibiotic resistance gene (bla KPC-2 and bla TEM-1, respectively) (Fig. 2). All these accessory resistance regions were genetically related to their counterparts from p0716-KPC and p12181-KPC. Compared with pKPC-LK30 and pKPHS2, p0716-KPC and p12181-KPC appear to have acquired many more accessory regions containing several additional resistance genes.

Discussion

The bla KPC genes are largely associated with Tn4401 and Tn6296 14, which constitute the core bla KPC genetic environments. bla KPC-carrying Tn4401b and its close derivatives are frequently found on plasmids from bacteria isolated in European and American countries17–19. Tn4401 is rarely found in China20, with Tn6296 and its derivatives more frequently identified as the bla KPC platforms, such as those located in pKP04813, pKPHS24, pKPC-LK305, and p0716-KPC and p12181-KPC (this study).

bla KPC genes are also commonly identified in plasmids belonging to various incompatibility groups, including IncF, IncI, IncA/C, IncN, IncX, IncR, IncP, IncU, IncW, IncL/M, and ColE, ranging in size from 10–300 kb21. The IncF replicons can be classified into the groups FIA, FIB, FIC, and FII22. The IncFII plasmids are commonly low copy number plasmids and carry the primary FII replicon, often in association with additional replicons such as FIA and FIB. Moreover, the FII replicons can be further divided into various subtypes, including IIK, FIIY, and FIIS, generating many compatible variants that can be used to overcome the incompatibility barrier with incoming plasmids22.

The IncFII plasmid family can replicate in many different enterobacterial species, and is clearly playing an important role in the dissemination of antimicrobial resistance genes, including bla KPC, amongst Enterobacteriaceae21. The bla KPC-3-carrying IncFIIK plasmid pKpQIL and its close derivatives have spread in European and American countries23. bla KPC-2-carrying IncFIIK plasmids from China, such as pKP048 and pKPHS2, have very similar core backbone regions but limited overall sequence similarity to pKpQIL. It seems that the pKpQIL-like and pKP048-like plasmids followed distinct evolutionary routes after separating from their common ancestor.

Recovery of the closely related plasmids p0716-KPC and p12181-KPC from two independent cases of nosocomial infection from two different hospitals indicates the potential of trans-regional spread and circulation of these plasmids in hospital settings. p0716-KPC and p12181-KPC belong to a novel IncFII subtype, and display a complex chimeric nature, as observed within the backbone as well as the accessory resistance regions. The replication and stable inheritance of these two plasmids is likely promoted by the coordinated action of the IncFII and Rep_3-family replicons and the IncFIIK and IncFIIY maintenance gene sets, respectively.

Production of KPC-2 makes strains containing p0716-KPC or p12181-KPC resistant to almost all β-lactams, including carbapenems. The situation is exacerbated by the presence of five additional classes of antibiotic resistance genes [mph(A), strAB and aacC2, qacEΔ1, sul1 and sul2, and dfrA25] on these two plasmids. The accumulation of various antibiotic resistance genes on a plasmid have resulted from complex horizontal genetic transfer events under selection pressure of multiple antibiotics, and a bacterium will become resistant to multiple antibiotics at once by picking up such a MDR plasmid.

p0716-KPC is conjugative and contains the complete IncFIIK conjugal transfer gene content, while p12181-KPC has become non-conjugative likely because of the presence of multiple genetic lesions in the conjugal transfer regions. Non-transmissible plasmids rely largely on vertical transmission to be maintained in populations. Although classical models of plasmid evolution predict that conjugation is necessary for plasmid maintenance, it has been found that compensatory adaptation to ameliorate the cost of plasmid carriage coupled to rare (positive) selection for plasmid-encoded antibiotic resistance is sufficient to stabilize non-transmissible plasmids, explaining why non-conjugative plasmids are common24.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial strains and identification

The use of human specimens and all related experimental protocols was approved by the Committee on Human Research of all the institutions (Beijing Institute of Microbiology and Epidemiology, the 307th Hospital of the People’s Liberation Army, and Navy General Hospital), and was carried out in accordance with the approved guidelines. Informed consent was obtained from patients where indicated. Our research was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Imipenem-non-susceptible K. pneumoniae strains 0716 and 12181 were isolated from two inpatients with hospital-acquired infections from two different public hospitals, and there was no epidemiological link between the two patients. Bacterial species identification was performed by 16 S rRNA gene sequencing25. The major plasmid-borne carbapenemase genes were screened by PCR26. All PCR amplicons were sequenced on an ABI 3730 Sequencer using the PCR primers.

Plasmid conjugal transfer

Plasmid conjugal transfer experiments were carried out using rifampin-resistant Escherichia coli strain EC600 as the recipient, and K. pneumoniae strains 0716 and 12181 as donors. Aliquots (3 ml) of overnight culture of each donor and recipient strain were mixed, harvested, and resuspended in 80 μl of Brain Heart Infusion (BHI) broth (BD Biosciences). The mixtures were spotted on 1 cm2 hydrophilic nylon membrane filters with a 0.45-µm pore size (Millipore), which were then placed on BHI agar (BD Biosciences) plates and incubated at 37 °C for 12–18 h. Bacteria were washed from the filter membranes and spotted on Muller-Hinton (MH) agar (BD Biosciences) plates containing 1 mg/ml rifampin and 2 μg/ml imipenem for selection of bla KPC-positive E. coli transconjugants.

Plasmid electroporation

To prepare competent E. coli TOP10 cells for plasmid electroporation, 200 ml of overnight culture in Super Optimal Broth (SOB) at an optical density (OD600) of 0.4–0.6 were washed three times with electroporation buffer (0.5 M mannitol and 10% glycerol), and then concentrated into a final volume of 2 ml. A 1-µg aliquot of plasmid DNA, isolated from strain 0716 or 12181 using a Qiagen Plasmid Midi Kit, was mixed with 100 μl of competent cells for electroporation at 25 μF, 200 Ω, and 2.5 kV. Immediately following electroporation, cells were suspended in 500 μl of SOB, and an appropriate aliquot was spotted on an SOB agar plate containing 2 μg/ml imipenem for selection of bla KPC-positive E. coli transformants.

Detection of carbapenemase activity

Activity of class A/B/D carbapenemases in bacterial cell extracts was determined via a modified CarbaNP test26. Briefly, overnight bacterial culture in MH broth was diluted 1:100 into 3 ml of fresh MH broth, and then incubated at 37 °C with shaking at 200 rpm to an OD600 of 1.0–1.4. If required, ampicillin was used at 200 μg/ml. Bacterial cells were harvested from 2 ml of the above culture and washed twice with 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.8). Cell pellets were resuspended in 500 μl of 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.8), lysed by sonication, and then pelleted by centrifugation at 10000 × g for 5 min at 4 °C. Aliquots (50 µl) of the supernatant (the enzymatic bacterial suspension) were individually mixed with 50 μl of substrates I–V, followed by incubation at 37 °C for a maximum of 2 h. The substrates consisted of: (I) 0.054% phenol red, 0.1 mM ZnSO4 (pH 7.8); (II) 0.054% phenol red, 0.1 mM ZnSO4 (pH 7.8), 0.6 mg/μl imipenem; (III) 0.054% phenol red, 0.1 mM ZnSO4 (pH 7.8), 0.6 mg/μl imipenem, 0.8 mg/μl tazobactam; (IV) 0.054% phenol red, 0.1 mM ZnSO4 (pH 7.8), 0.6 mg/μl imipenem, 3 mM EDTA (pH 7.8); (V) 0.054% phenol red plus 0.1 mM ZnSO4 (pH 7.8), 0.6 mg/μl mg imipenem, 0.8 mg/μl tazobactam, 3 mM EDTA (pH 7.8).

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing was conducted using the VITEK 2 system (bioMérieux) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and interpreted as per the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute guidelines27.

Plasmid sequencing and annotation

Plasmid DNA was isolated from E. coli transformants using a Qiagen Large Construct Kit, and then sequenced from a paired-end library with an average insert size of 500 bp, and a mate-pair library with average insert size of 5,000 bp, using an Illumina MiSeq sequencer. The circled DNA contigs were assembled using Newbler 2.628. Open reading frames and pseudogenes were predicted using RAST 2.029 combined with BLASTP/BLASTN30 searches against the UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot31 and RefSeq32 databases. Annotation of resistance genes, mobile elements, and other features was carried out using CARD33, ResFinder34, ISfinder35, INTEGRALL36, and the Tn Number Registry37. Multiple and pairwise sequence comparisons were performed using MUSCLE 3.8.3138 and BLASTN, respectively. Gene organization diagrams were drawn in Inkscape 0.48.1.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers

The complete nucleotide sequences of p0716-KPC and p12181-KPC were submitted to GenBank under accession numbers KY270849 and KY270850, respectively.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Basic Research Program of China (2015CB554200) and the Special Key Project of Biosafety Technologies (2016YFC1202600) for the National Major Research & Development Program of China.

Author Contributions

D.S.Z., Y.L., and J.W. conceived the study and designed experimental procedures. J.F., Z.Y., Q.Z., Y.Z., D.Z., and X.J. performed the experiments. J. F., D.S.Z., Y.Z., and D.Z analyzed the data. Q.Z., W.W., W.C., H.W., Y.S., and Y.T. contributed reagents and materials. D.S.Z., Y.L., J.W., and J.F. wrote this manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Jiao Feng and Zhe Yin contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at doi:10.1038/s41598-017-06283-z

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Jinglin Wang, Email: wjlwjl0801@sina.com.

Yanjun Li, Email: liyanjun1230@163.com.

Dongsheng Zhou, Email: dongshengzhou1977@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Nordmann P, Cuzon G, Naas T. The real threat of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase-producing bacteria. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009;9:228–236. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70054-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Munoz-Price LS, et al. Clinical epidemiology of the global expansion of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemases. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13:785–796. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70190-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee GC, Burgess DS. Treatment of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC) infections: a review of published case series and case reports. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2012;11:32. doi: 10.1186/1476-0711-11-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu P, et al. Complete genome sequence of Klebsiella pneumoniae subsp. pneumoniae HS11286, a multidrug-resistant strain isolated from human sputum. J Bacteriol. 2012;194:1841–1842. doi: 10.1128/JB.00043-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen YT, et al. KPC-2-encoding plasmids from Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae in Taiwan. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014;69:628–631. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang TW, et al. Complete sequences of two plasmids in a blaNDM-1-positive Klebsiella oxytoca isolate from Taiwan. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:4072–4076. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02266-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fernandez-Lopez R, de Toro M, Moncalian G, Garcillan-Barcia MP, de la Cruz F. Comparative Genomics of the Conjugation Region of F-like Plasmids: Five Shades of F. Frontiers in molecular biosciences. 2016;3:71. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2016.00071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cain AK, Liu X, Djordjevic SP, Hall RM. Transposons related to Tn1696 in IncHI2 plasmids in multiply antibiotic resistant Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium from Australian animals. Microb Drug Resist. 2010;16:197–202. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2010.0042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Partridge SR. Analysis of antibiotic resistance regions in Gram-negative bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2011;35:820–855. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2011.00277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Partridge SR, Brown HJ, Stokes HW, Hall RM. Transposons Tn1696 and Tn21 and their integrons In4 and In2 have independent origins. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001;45:1263–1270. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.4.1263-1270.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liebert CA, Hall RM, Summers AO. Transposon Tn21, flagship of the floating genome. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1999;63:507–522. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.63.3.507-522.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Partridge SR, Hall RM. The IS1111 family members IS4321 and IS5075 have subterminal inverted repeats and target the terminal inverted repeats of Tn21 family transposons. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:6371–6384. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.21.6371-6384.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jiang Y, et al. Complete nucleotide sequence of Klebsiella pneumoniae multidrug resistance plasmid pKP048, carrying blaKPC-2, blaDHA-1, qnrB4, and armA. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:3967–3969. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00137-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang L, et al. Complete sequences of KPC-2-encoding plasmid p628-KPC and CTX-M-55-encoding p628-CTXM coexisted in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:838. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bailey JK, Pinyon JL, Anantham S, Hall RM. Distribution of the blaTEM gene and blaTEM-containing transposons in commensal Escherichia coli. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66:745–751. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.He S, et al. Insertion Sequence IS26 Reorganizes Plasmids in Clinically Isolated Multidrug-Resistant Bacteria by Replicative Transposition. MBio. 2015;6:e00762. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00762-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen L, et al. Partial Excision of blaKPC from Tn4401 in Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:1635–1638. doi: 10.1128/AAC.06182-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bryant KA, et al. KPC-4 Is encoded within a truncated Tn4401 in an IncL/M plasmid, pNE1280, isolated from Enterobacter cloacae and Serratia marcescens. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:37–41. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01062-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chmelnitsky I, et al. Mix and match of KPC-2 encoding plasmids in Enterobacteriaceae-comparative genomics. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2014;79:255–260. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2014.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ho PL, et al. Molecular Characterization of an Atypical IncX3 Plasmid pKPC-NY79 Carrying bla KPC-2 in a Klebsiella pneumoniae. Curr Microbiol. 2013;67:493–498. doi: 10.1007/s00284-013-0398-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen L, et al. Carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae: molecular and genetic decoding. Trends Microbiol. 2014;22:686–696. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2014.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Villa L, Garcia-Fernandez A, Fortini D, Carattoli A. Replicon sequence typing of IncF plasmids carrying virulence and resistance determinants. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010;65:2518–2529. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen L, et al. Comparative genomic analysis of KPC-encoding pKpQIL-like plasmids and their distribution in New Jersey and New York Hospitals. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58:2871–2877. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00120-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.San Millan A, et al. Positive selection and compensatory adaptation interact to stabilize non-transmissible plasmids. Nature communications. 2014;5:5208. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frank JA, et al. Critical evaluation of two primers commonly used for amplification of bacterial 16S rRNA genes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74:2461–2470. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02272-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen Z, et al. NDM-1 encoded by a pNDM-BJ01-like plasmid p3SP-NDM in clinical Enterobacter aerogenes. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:294. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing; Twenty-Second Informational Supplement. CLSI document M100-S25, Vol. 35 (CLSI, 2015).

- 28.Nederbragt AJ. On the middle ground between open source and commercial software - the case of the Newbler program. Genome Biol. 2014;15:113. doi: 10.1186/gb4173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brettin T, et al. RASTtk: a modular and extensible implementation of the RAST algorithm for building custom annotation pipelines and annotating batches of genomes. Sci Rep. 2015;5:8365. doi: 10.1038/srep08365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boratyn GM, et al. BLAST: a more efficient report with usability improvements. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:W29–33. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boutet E, et al. UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot, the Manually Annotated Section of the UniProt KnowledgeBase: How to Use the Entry View. Methods Mol Biol. 2016;1374:23–54. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-3167-5_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O’Leary NA, et al. Reference sequence (RefSeq) database at NCBI: current status, taxonomic expansion, and functional annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:D733–745. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jia B, et al. CARD 2017: expansion and model-centric curation of the comprehensive antibiotic resistance database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:D566–573. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zankari E, et al. Identification of acquired antimicrobial resistance genes. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67:2640–2644. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Siguier P, Perochon J, Lestrade L, Mahillon J, Chandler M. ISfinder: the reference centre for bacterial insertion sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D32–36. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moura A, et al. INTEGRALL: a database and search engine for integrons, integrases and gene cassettes. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1096–1098. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roberts AP, et al. Revised nomenclature for transposable genetic elements. Plasmid. 2008;60:167–173. doi: 10.1016/j.plasmid.2008.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Edgar RC. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:1792–1797. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.