Abstract

Cancer has long been known to histologically resemble developing embryonic tissue. Since this early observation, a mounting body of evidence suggests that cancer mimics or co-opts developmental processes to facilitate tumor initiation and progression. Programs important in both normal ontogenesis and cancer progression broadly fall into three domains: the lineage commitment of pluripotent stem cells; the appropriation of primordial mechanisms of cell motility and invasion; and the influence of multiple aspects of the microenvironment on the parenchyma. In this review, we discuss how derangements in these developmental pathways drive cancer progression with a particular focus on how they have emerged as targets of novel treatment strategies.

Cancer Subverts Normal Developmental Processes

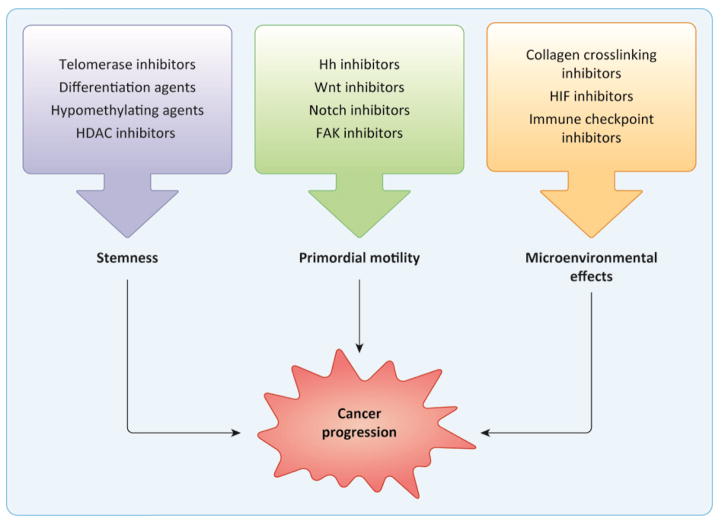

The idea that cancer mimics or co-opts developmental processes was proposed as early as the 19th century, when the renowned pathologist Rudolf Virchow first championed the “embryonal rest” theory: that carcinoma is the proliferation of embryonic epithelial cells that remain in an undeveloped state [1]. This hypothesis arose from the observation that tumors often histologically resemble embryonic tissue. Virchow’s idea was well ahead of its time and had at one point been lost to history, but with accumulating evidence demonstrating the critical role of various developmental pathways in cancer pathogenesis, elements of his original proposal are now reflected in present-day models. With this review, we aim to highlight important parallels between normal development and cancer progression, and to call attention to advances in the treatment of cancer resulting from our understanding of these links. While it can be overwhelming to individually consider the multiple connections between the two, many of the phenomena important in both normal development and cancer fall conceptually into three broad domains: the balance of stemness and differentiation; primordial mechanisms of cell motility; and cellular responses to microenvironmental signals (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Developmental processes implicated in cancer progression are targeted by novel therapies.

Phenomena important in both normal development and tumor progression broadly fall into three domains: stemness and lineage commitment; primordial mechanisms of motility; and microenvironmental effects. Understanding these processes has led to the development of new treatment modalities, with a selection of notable examples depicted. Importantly, many of these agents are not limited to a single mechanism of action. For instance, while the polarity signaling pathways promote motility and invasion through developmental mechanisms of motility like EMT, they also contribute to the maintenance of stemness.

Ontogenesis starts with undifferentiated embryonic stem cells (ESCs), and stemness refers to the ability of these cells to be both self-renewing and pluripotent. This requires telomerase activity to maintain replicative potential as well as epigenetic plasticity to undergo lineage commitment. Cancer cells can adopt these features for immortalization through pathologic telomerase activation and for impairments in differentiation via epigenetic alterations.

For normal development and differentiation of tissues, many growth factor signaling pathways are required, including Wnt, Fgf, TGF-β, Hh, and Notch. These are used reiteratively during development of different tissues, in different combinations, combined with other factors including epigenetic. Once differentiated, normal tissue development requires establishment of cell polarity, through which organization of cells and subcellular structures by apicobasal and planar axes is enforced. Inappropriate activation of any of the growth factors and/or polarity-regulating pathways can have different effects in different tissues, and consequently also in cancers arising from different tissues [2, 3] with implications in cancer progression as well [4, 5]. Furthermore, multiple polarity signaling pathways are implicated in the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), a primordial mechanism of cell motility critical for the appropriate migration of specific cell populations in the developing embryo. In cancer, EMT and other developmental mechanisms of cell migration are commandeered to promote invasion and metastasis.

Microenvironmental cues are known to promote EMT, but also generate other cellular responses. For instance, mechanical signals from the ECM guide branching morphogenesis of pancreatic ducts [6] and also drive progression of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) [7]. Chemical cues such as hypoxia are also critical, and hypoxic signaling is not only required for the normal development of the cardiovascular system [8], but has also been implicated in cancer invasion and metastasis [9]. Finally, signals from stromal cells prevent maternal immune rejection of the fetus during normal development [10], but the same pathways are hijacked in cancer to allow immune evasion [11]. Understanding how developmental phenomena contribute to cancer pathogenesis has led to a myriad of novel treatment strategies that have already revolutionized the treatment of cancer, and the promise of other potentially practice-changing therapies remains on the horizon.

Features of stemness are co-opted in cancer pathogenesis

Continuous replication of cells is limited by telomere attrition. Therefore, ESCs express telomerase to allow for indefinite self-renewal and even somatic stem cells (SSCs) have low levels of telomerase activity to prolong their time to senescence [12]. Failure of telomere maintenance leads to a spectrum of disorders that are frequently marked by failure of various organs, including idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, aplastic anemia, and cirrhosis of the liver [13]. In contrast, pathologic telomerase activation is seen in most cancers and contributes to immortalization [14]. Accordingly, telomerase inhibition has been an attractive target for potential cancer therapies. Imetelstat is the most mature of these agents and has shown promise in preclinical settings for breast cancer, non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [15], and acute myeloid leukemia (AML) [16]. While it proved too toxic for use in the salvage setting for pediatric brain tumors due to severe thrombocytopenia [17], early-phase clinical trials have shown promise in essential thrombocythemia (ET), a type of myeloproliferative neoplasm (MPN), and MPN-associated myelofibrosis [18, 19]. While imetelstat failed to improve progression-free survival when used as a maintenance therapy in advanced NSCLC, there was a trend toward improvement in patients with short telomere length [15], suggesting this may be a way to select for potential responders, and a number of clinical trials in other settings remain in process.

Following embryonic development, populations of lineage-restricted SSCs remain in mature tissues to allow maintenance and regeneration, well-characterized examples of which include hematopoietic, skin, and colonic crypt stem cells. Techniques such as spheroid culture, limiting dilution transplantation assays, and phenotypic characterization with flow cytometry were initially used to characterize ESCs and SSCs, but have since been applied in tumors to define a subpopulation of cancer stem cells (CSCs) that are sufficient to generate a whole neoplasm. Lineage tracing has significantly advanced our knowledge of organ development [20, 21] and is now being employed to characterize the cell of origin of many tumor types in vivo [22, 23]. Using this technique, bipotent progenitor cells, which can give rise to two distinct lineages, have been identified during the development of the mammary gland, lung, and prostate, which could explain the high degree of heterogeneity in primary tumors at these sites. For instance, in the mammary gland, a distinct luminal progenitor cell with alveolar characteristics was shown to be able to give rise to both luminal and basal subtypes of breast cancer [24]. Once believed to arise from an isolated clone, single cell sequencing of tumors has allowed us to identify multiple different clonal populations in precursor lesions that develop into heterogeneous invasive carcinomas [25]. Indeed, lineage commitment in physiologic development of blood and skin cells has been shown to rely upon epigenetic modifications working in tandem with changes in gene expression [26], and perturbations in this process interrupt differentiation and can lead to a variety of other hematologic malignancies [27].

Acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) is classically characterized by interrupted differentiation as a result of a recurrent fusion of the promyelocytic leukemia (PML) and retinoic acid receptor α (RARα) genes. Treatment with all-trans-retinoic acid (ATRA) and arsenic trioxide restores normal differentiation and frequently results in cure, even without the use of conventional cytotoxic chemotherapy in low-risk patients [28]. Interestingly, the PML-RARα fusion protein has been shown to alter epigenetic regulation of hematopoietic progenitors, suggesting that this is one mechanism by which differentiation arrest occurs in these cells [29]. A wide range of genes encoding chromatin modifiers are often mutated in the myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) and AML, including ten eleven translocation 2 (TET2), DNA methyltransferase 3A (DNMT3A), and lysine methyltransferase 2A (KMT2A) [27]. In addition to the modifying enzymes themselves, readers of chromatin modification such as the bromodomain and extra-terminal (BET) family proteins can also affect differentiation. A fusion protein combining nuclear protein in testis (NUT) and bromodomain-containing protein 4 (BRD4) is the defining genetic alternation of NUT midline carcinoma (NMC), an aggressive subtype of squamous cell carcinoma. While the exact mechanism of pathogenesis has not yet been fully elucidated, work to date has shown that this fusion product interrupts differentiation, which can be restored with histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors [30]. In multiple myeloma (MM) cells, wild-type BRD4 is enriched at enhancer sites in oncogene promoters, notably including MYC, and treatment with the BET inhibitor JQ1 displaced BRD4 from these enhancers and reduced oncogene expression [31]. BET inhibitors are now being studied in multiple cancers (Table 1). Other agents targeting epigenetics, including inhibitors of lysine-specific demethylase (LSD1) and Jumonji C (JmjC)-domain-containing histone demethylases, are undergoing preclinical and early clinical trials in AML [32]. Hypomethylation agents such as azacytidine and decitabine have already been approved for clinical use in MDS and are also used in AML patients who are not candidates for standard chemotherapy. HDAC inhibitors, including vorinostat, romidepsin, belinostat, and panobinostat, have been approved for use in cutaneous and peripheral T-cell lymphomas and MM, and trials evaluating their utility in a wide array of other malignancies are in process. The ultimate hope with these drugs would be to reprise the unmitigated success of differentiation therapy seen in APL.

Table 1. Selected agents currently being evaluated in clinical trials.

Trials were identified using ClinicalTrials.gov accessed between 9/7/16 and 9/14/16. Due to space constraints, only one trial per agent is listed, with preference for most advanced phase followed by newest NCT identifier number at time of search. Targets and agents are listed in alphabetical order.

| Target | Agent | Tumor type | Phase | Status | NCT identifier |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stemness, Epigenetics, and Lineage Commitment | |||||

| BET inhibitors | ABBV-075 | Advanced malignancies | 1 | Recruiting | NCT02391480 |

| BMS-986158 | Advanced solid tumors | 1/2 | Recruiting | NCT02419417 | |

| CPI-0610 | Hematologic malignancies | 1 | Recruiting | NCT02158858 | |

| GSK525762 | Solid tumors | 1 | Recruiting | NCT01587703 | |

| GSK2820151 | Advanced solid tumors | 1 | Not yet open | NCT02630251 | |

| INCB054329 | Advanced malignancies | 1/2 | Recruiting | NCT02431260 | |

| INCB057643 | Advanced malignancies | 1/2 | Recruiting | NCT02711137 | |

| OTX105/MK-8628 | AML and DLBCL | 1 | Recruiting | NCT02698189 | |

| RO6870810/TEN- 010 | AML and MDS | 1 | Recruiting | NCT02308761 | |

| ZEN003694 | Prostate cancer | 1 | Not yet open | NCT02711956 | |

| HDAC inhibitors | AR-42 | AML | 1 | Active, not recruiting | NCT01798901 |

| Mocetinostat | Advanced solid tumors | 1 | Recruiting | NCT02805660 | |

| Panobinostat | Melanoma | 1 | Recruiting | NCT02032810 | |

| Tefinostat | HCC | 1/2 | Recruiting | NCT02759601 | |

| Vorinostat | Melanoma | 1 | Recruiting | NCT02836548 | |

| LSD1 inhibitors | GSK2879552 | AML | 1 | Recruiting | NCT02177812 |

| IMG-7289 | AML | 1 | Not yet open | NCT02842827 | |

| INCB059872 | Advanced malignancies | 1/2 | Not yet open | NCT02712905 | |

| Tranylcypromine | AML and MDS | 1 | Recruiting | NCT02273102 | |

| Telomerase inhibitor | Imetelstat | MDS | 3 | Recruiting | NCT02598661 |

| Polarity Pathways and Primordial Motility | |||||

| FAK inhibitors | defactinib | Advanced solid tumors | 1/2 | Not yet open | NCT02758587 |

| GSK2256098 | Pancreatic cancer | 2 | Recruiting | NCT02428270 | |

| γ-secretase inhibitors | RO4929097 | GBM | 2 | Active, not recruiting | NCT01122901 |

| BMS-906024 | Advanced solid tumors | 1 | Active, not recruiting | NCT01292655 | |

| Porcupine inhibitors | ETC-1922159 | Advanced solid tumors | 1 | Recruiting | NCT02521844 |

| Smo inhibitors | Wnt974 | HNSCC | 2 | Not yet open | NCT02649530 |

| sonidegib | HCC | 1 | Recruiting | NCT02151864 | |

| PF-04449913 | AML and ALL | 2 | Recruiting | NCT01841333 | |

| Wnt5a agonist | Foxy-5 | Advanced solid tumors | 1 | Recruiting | NCT02655952 |

| Chemical and Cellular Microenvironment | |||||

| CCR2 inhibitors | PF-04136309 | PDAC | 1/2 | Recruiting | NCT02732938 |

| TAK-202 | Melanoma | 1 | Recruiting | NCT02723006 | |

| CD47 antibody | TTI-621 | CTCL and injectable tumors | 1 | Not yet open | NCT02890368 |

| CSF1R inhibitors | cabiralizumab | Advanced solid tumors | 1 | Recruiting | NCT02526017 |

| emactuzumab | Advanced solid tumors | 1 | Active, not recruiting | NCT01494688 | |

| LY3022855 | Advanced solid tumors | 1 | Recruiting | NCT02718911 | |

| pexidartinib | Pancreatic and colon cancers | 1 | Recruiting | NCT02777710 | |

| CTLA-4 inhibitors | ipilimumab | Pre-B ALL | 1 | Not yet open | NCT02879695 |

| tremelimumab | Ovarian cancer | 1/2 | Recruiting | NCT02571725 | |

| HIF-1α inhibitor | EZN-2968 | HCC | 1 | Recruiting | NCT02564614 |

| IDH mutant inhibitors | AG-120 | AML | 1/2 | Recruiting | NCT02677922 |

| AG-221 | AML | 3 | Recruiting | NCT02577406 | |

| AG-881 | Advanced solid tumors | 1 | Recruiting | NCT02481154 | |

| BAY1436032 | Advanced solid tumors | 1 | Recruiting | NCT02746081 | |

| FT-2102 | AML and MDS | 1 | Recruiting | NCT02719574 | |

| IDO inhibitor | indoximod | NSCLC | 1/2 | Recruiting | NCT02460367 |

| PD-1 inhibitors | JS001 | Triple-negative breast cancer | 1 | Recruiting | NCT02838823 |

| nivolumab | Pre-B ALL | 1 | Not yet open | NCT02879695 | |

| PDR001 | Selected solid tumors | 1/2 | Recruiting | NCT02404441 | |

| pembrolizumab | HNSCC | 1/2 | Recruiting | NCT02718820 | |

| PD-L1 inhibitors | durvalumab | Lymphoma and CLL | 1/2 | Recruiting | NCT02733042 |

| PD-L1, PD-L2 inhibitor | CA-170 | Solid tumors and lymphomas | 1 | Recruiting | NCT02812875 |

| Tim3 inhibitor | MBG453 | Advanced solid tumors | 1 | Recruiting | NCT02608268 |

Tumors adopt developmental mechanisms of motility

During embryonic development, differentiation can coincide with cell movement to a particular location within the body or tissue and the establishment of polarity. Neural crest progenitors give rise to multiple cell types that migrate extensively throughout the embryo, such as craniofacial derivatives, neurons and glia of the peripheral nervous system, and melanocytes [33]. Unsurprisingly, these lineages can give rise to highly motile and metastatic tumors, including melanomas and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors (MPNSTs). Melanoma cells migrate along the same pathways as their progenitor counterparts when transplanted into a developing embryo, showing that they retain their primordial attributes [34]. Melanocyte precursors leave the neural crest through a process of delamination, which requires EMT, a potent mechanism of individual cell motility. Many developmental mechanisms of EMT have been elucidated using non-mammalian vertebrate model systems, and these are discussed in detail separately (Box 1). However, the role of EMT in mammalian embryonic development is controversial, which hinders our ability to develop treatments that directly target EMT. EMT and its reverse, the mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition (MET), are necessary to cause non-invasive tumors to initiate metastasis and colonize secondary sites in vivo [35, 36]. EMT is directly facilitated by transcription factors in the Snail, Twist, and Zeb families, but is initiated by upstream cues from classical developmental signaling pathways such as Wnt, Hh, Notch, and transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) [37]. Many experimental drugs targeting these pathways are currently in preclinical and early clinical trials, while Smoothened (Smo)-inhibitors targeting Hh signaling such as vismodegib and sonidegib are already approved for clinical use [38]. At present, the Smo-inhibitors are indicated for use in patients with basal cell carcinoma (BCC) that are not candidates for complete surgical resection. While clinical trials aimed at expanding their labeled indications to other tumor types have not yet been successful at doing so, available trial data hint that they may have a role in the sonic hedgehog (Shh)-driven subset of medulloblastomas [39]. The hope remains that these and other drugs targeting different levels of the Hh pathway will have a role to play in correctly selected patient populations.

Text Box 1. EMT: A powerful force behind individual cell motility.

The epithelial-mesenchymal plasticity (EMP or EMT) is at the core of multiple developmental processes. It facilitates cellular movement coinciding with cell fate specification. Cell-cell contacts comprised of tight junctions, adherens junctions, and desmosomes ensure the relative positioning of the epithelial cells. Claudins, occludins, cadherins, and plakoglobins (the proteins which comprise cell-cell junctions) are the first transcriptional targets of the EMT master regulator transcription factors; namely Snail, Twist, and Zeb family members. These adhesive molecules are replaced by their less adhesive counterparts while the intermediate filaments of the cytoskeleton are converted from cytokeratins to vimentin as well as actin stress fibers in preparation of cellular movement. Dissolution of cell-cell contacts also disrupts apico-basal polarity. Distribution of protein complexes normally confined to the apical or basolateral compartments, such as Crumbs and Scribble respectively, is disturbed leading to further downregulation of epithelial lineage markers [37].

In embryonic development Wnt initiates the first EMT, known as primary EMT, during gastrulation and delamination from the primitive streak. Subsequently, induction of Snail1 activity by members of the TGFβ superfamily is necessary for gastrulation to occur, and Snail1 deficient embryos fail to form three germ layers in mice. Delamination from the neural crest follows as another form of primary EMT signaled by Wnt, Bmp4, and Notch through the direct action of Snail2. A second round of EMT, or secondary EMT, facilitates the formation of somites, the palate, pancreatic islet cells, liver, and reproductive tracts during embryogenesis. However, these cells must pass through mesenchymal to epithelial transition (MET) by repression of Snail factors before initiating secondary EMT. Shh and Noggin initiate secondary EMT to form somites which develop into vertebrae. The heart is a unique example as it undergoes primary, secondary, and tertiary rounds of EMT to form the cardiac cushion, valves, and epicardium [87].

Postnatally, an intermediate phenotype of EMT facilitates wound healing by promoting mobility of keratinocytes. Similar metastable states are seen in pathological settings such as fibrosis and cancer metastasis. TGFβ induction of SNAIL1 is the primary mediator of fibrotic EMT while more diverse mechanisms contribute to dissemination of tumor cells. Hypoxia, Notch, and TGFβ signaling activate Twist, Snail, and Zeb to induce EMT in diverse tumor types. Furthermore, features of EMT are seen at the invasive front of a variety of carcinomas and expression of Snail1/2 predict poor overall survival, indicating that therapeutic targeting of epithelial-mesenchymal plasticity could be an effective strategy to inhibit metastasis of solid tumors.

In contrast to individual cell motility, developmental studies of the fish lateral line primordium and of the Xenopus neural crest have identified how collective cell migration can be a highly efficient mode of directional cellular movement [40]. Developmental mechanisms of collective cell migration in mammals are less well understood and warrant further investigation. Maintenance of polarity and cell-cell contacts through adherens junctions is essential for collective cell migration as well as communication between follower cells and leader cells, the latter of which determine directionality by sensing the microenvironment [41]. Collective cell migration has been observed in multiple carcinomas, including those of the breast, prostate, and pancreas [42]. Only leader cells initiate invasive protrusions in organoid culture and in vivo; however, both leader and follower cells are present in metastatic lesions within the lung, demonstrating the importance of collective cell migration [43]. Cell-surface cadherins and ephrins mediate sensing of cell-cell contact while planar cell polarity (PCP) is active at cell junctions along the axis of the tissue [44]. The role of PCP in collective cell migration depends on the species and even cell type being studied. PCP, stimulated by Wnt5a and Wnt11 ligands, facilitates two divergent pathways that influence cell motility differently depending on adjacent cellular contact. Therefore, loss of Wnt5a protein expression has been linked to more aggressive breast cancers [45], while Wnt5a treatment of melanoma cells stimulates actomyosin contraction and migration [46]. Preclinical studies identified a Wnt5a peptide mimetic, Foxy-5, that reduced invasion and migration of breast cancer cells and inhibited pulmonary metastasis in vivo [47]. Based on these findings, Foxy-5 is in phase 1 clinical trials with the intention of establishing a maximum tolerated dose for later-phase trials in metastatic breast, colon, and prostate cancer. The antipodal roles of noncanonical Wnt signaling in breast cancer and melanoma underscores the complexity of the cell polarity pathways. Selection of appropriate treatment may depend on whether a particular cancer has a predilection for individual or collective cell motility.

Establishment of PCP and contact inhibition of locomotion (CIL) are proposed to mediate short-range directional cohesive movement during collective cell migration. Although CIL also heavily influences individual cell motility, it may play a dual role in collective movement by stimulating migration of leader cells while preventing formation of protrusions in follower cells [48]. Interestingly, cancer cells maintain homotypic CIL, but do not exhibit heterotypic CIL when in contact with stromal cells [49]. Distinct expression of members of the Ephrin family of receptors is responsible for this phenomenon in prostate cancer [50].

Cell motility, whether individual or collective, requires physical contact with the ECM through integrins and focal adhesions. Integrins cluster with adaptor proteins, actin stress fibers, and a variety of kinases, including focal adhesion kinase (FAK), integrin-linked kinase (ILK), and Src-family kinases, to form mature macromolecular complexes known as focal adhesions that anchor the cell to the ECM and signal through Rac and Cdc42. Preclinical studies have identified that FAK expression enhances tumor cell motility, and its loss prevents extravasation and lung colonization of breast cancer cells [51]. Small molecule FAK inhibitors have demonstrated promise in preclinical studies [52, 53], and are now in early-phase clinical trials for an array of solid tumors.

Microenvironmental cues shape both normal development and tumor progression

Originally thought to be little more than a scaffold upon which cells adhere and migrate, the ECM itself is now known to affect the behavior of associated parenchymal cells. Indeed, multiple aspects of the microenvironment have critical effects on the behavior of the cells within it. Components of the microenvironment include mechanical, chemical, and cellular elements. The mechanical microenvironment comprises the physical surroundings. The chemical microenvironment includes the local oxygen tension, pH, and metabolic byproducts. Finally, the cellular microenvironment refers to the stromal and immune cells associated with the parenchyma. Each of these compartments has unique roles in directing the behavior of parenchymal cells.

In organs known to produce stroma-rich tumors, such as pancreas, breast, and liver, the ECM guides ductal branching during embryonic and postnatal development. Time-lapse imaging of pancreatic explants revealed that integrin interaction with the basement membrane provides cues that facilitate embryonic ductal branching morphogenesis through reorganization of the cap and body cell layers [6]. Similarly, deposition of ECM components distal to the mammary terminal end bud (TEB) impedes ductal extension thereby causing bifurcation of the ductal tree during postnatal development [54]. ECM stiffness controls liver development by activating the Hippo signaling pathway, a mechanosensing pathway driven by TEA domain (TEAD) transcription factors and Yes-associated protein (YAP) and TAZ coactivators. Hippo in turn controls organ size by overriding contact inhibition of proliferation and, unsurprisingly, mice overexpressing YAP exhibit hepatomegaly that progresses into frank hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Correspondingly, cirrhosis of the liver, characterized by fibrosis and stiff ECM, predisposes patients to HCC [55]. Mechanistic studies have shown that altering the stiffness of ECM components causes an increase in incidence, velocity, and directionality of migration in both normal and cancer cells [56–58]. Tensile microenvironments induce concerted cellular division and collective migration, a process that has been characterized during gastrulation in fish, but may very well be essential in primary tumors where groups of cells invade into stromal regions of low tension [59]. Moreover, mutating β-integrin to promote tensile integrin clustering and associated downstream signaling in murine models accelerated the development of high-grade PDAC lesions [7]. In patients, tensile collagen in the ECM of PDAC is often associated with poorly differentiated histology as well as lower overall survival. Given these observations, treatments aimed at reducing the stiffness of the ECM have been proposed, including lysyl oxidase (LOX) family inhibitors, targeting enzymes that enhance tension by crosslinking structural collagen [60]. Preclinical studies suggest that simtuzumab and aminopropionitrile, inhibitors targeting LOXL2, would be effective at preventing dissemination of non-metastatic tumors. Phase II clinical trials did not show added benefit with addition of simtuzumab to standard of care in metastatic pancreatic and colorectal adenocarcinoma [61] [62, 63]. However, successfully targeting matrix stiffness may require broader inhibition of all LOX family members or use in pre-metastatic disease.

Chemical microenvironmental cues such as hypoxia and pH also govern cell behavior through hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs), transcription factors important in sensing depressed oxygen tension and local pH [64, 65]. In ontogenesis, hypoxic signaling is required for angiogenesis and development of the placenta and cardiovascular system, and deletion of HIF-1α is embryonic lethal [8, 66]. Hypoxia is also required for the production and delamination of neural crest cells, discussed earlier, and this process is normally limited by the maturation of the circulatory system [67]. In cancer, HIF signaling is involved in angiogenesis, invasion, and metastasis [9, 68] as well as in maintenance of the CSC niche [69–71]. Furthermore, hypoxic signaling can work through LOX to increase matrix stiffness and promote metastatic niches [72]. HIFs have also been implicated in escape of tumors from antiangiogenic therapies [73]. While the importance of HIFs in cancer is well-established in preclinical studies, targeting these transcription factors has been a challenge. A recent study characterized a newly developed HIF-2α antagonist, PT2399, in clear cell renal cell carcinoma (RCC) [74]. Importantly, treatment with PT2399 resulted in upregulation of HIF-1α, and higher levels of HIF-1α mRNA transcription were associated with drug-resistance, underscoring the complexities that exist in targeting this pathway.

The cellular microenvironment comprises stromal cells, including macrophages, which play a vital role in mammary development and in breast tumor progression. In the developing pubertal mammary gland monocytes negatively regulate branching morphogenesis by inhibiting luminal differentiation through major histocompatibility complex class 2 (MHC-II) antigen presentation to Th1-type CD4+ T cells [75]. Furthermore, anti-inflammatory macrophages are required for proper postpartum involution through lysosome-mediated and apoptotic epithelial cell death [76]. In breast cancer patients, infiltration by tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) decreases overall and recurrence free survival. Moreover, macrophage depletion enhanced responses to chemotherapy and inhibited metastasis in spontaneous mammary tumor models [77]. Antibodies against colony stimulating factor 1 receptor (CSF1R) as well as inhibitors preventing maturation of monocytes into macrophages have been undergone preclinical studies [78], and are now being pursued in clinical trials in triple negative breast cancer patients. Similarly, C-C chemokine receptor type 2 (CCR2) antagonists can prevent recruitment of monocytes to the tumor site via chemotaxis, and are currently being evaluated for toxicity and efficacy [79].

Understanding of the cellular microenvironment has led to one of the most important recent advances in clinical oncology: the development of the immune checkpoint inhibitors [80]. In normal development, coinhibitory signaling through cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) and programmed death 1 (PD-1) plays a role in maternal immune tolerance to the developing fetus [10, 81]. These immune checkpoints also help prevent autoimmunity by promoting tolerance to self-antigen and through feedback inhibition of activated T-cells [11]. As such, PD-1 expression is inducibly expressed in the setting of active inflammation. However, if the stimulating antigen is not cleared in a timely fashion, as is the case in chronic infection and cancer, prolonged expression of PD-1 can lead to T-cell exhaustion [11, 82]. Furthermore, expression of PD-L1 and PD-L2, the ligands for PD-1, is upregulated by several pathways implicated in a variety of cancers, including the PTEN-PI3K-Akt axis, NF-kB, JAK-STAT, and MAPK [11]. Blockade of both CTLA-4 and the PD-1/PD-L1 axis relieves the coinhibitory signal and promotes antitumoral immunity [11, 83]. A number of monoclonal antibodies antagonizing this pathway are now approved for clinical use, including: ipilimumab, a CTLA-4 inhibitor; nivolumab and pembrolizumab, PD-1 inhibitors; and atezolizumab, a PD-L1 inhibitor. Much of the excitement surrounding these agents lies in their efficacy in treating cancers for which options were previously limited, including metastatic melanoma and urothelial cell carcinoma, and a number of trials are ongoing to assess their utility in other settings. Strikingly, the most recent update of the CheckMate 067 trial, which compared treatment of metastatic melanoma with ipilimumab alone, nivolumab alone, and both in combination, showed that the median duration of response to combination therapy had not yet been reached at a minimum of 18-month follow-up, with approximately half of the patients demonstrating progression free survival [84]. Compared with the dismal prognosis previously expected of these patients, this represents a radical change in the treatment of advanced melanoma and exemplifies the current excitement surrounding the use of immune checkpoint inhibitors in the treatment of cancer.

Concluding Remarks

Better understanding of developmental mechanisms involved in cancer progression has led to major advances in the treatment of cancer, from targeting differentiation in APL to the use of immune checkpoint inhibitors to alter the tumor microenvironment. However, a number of outstanding questions remain (see Outstanding Questions). The study of epigenetics has led to the realization that mutations in chromatin modifiers contribute to differentiation arrest, but whether CSCs arise from de-differentiation of lineage committed somatic cells versus from mutations in the SSC population remains to be seen. What is evident is that epigenetic modifications largely contribute to differentiation, which is inextricably linked to stemness, EMT, and motility in normal as well as cancer cells. Elucidating primary mechanisms for cell motility for individual cancers, whether by individual or collective means, may lead to novel treatment strategies to better address the process of metastasis. While the specific molecular mechanisms behind EMT and its functions in cancer metastasis remain controversial, recent in vivo lineage tracing approaches have also identified new roles for EMT in mediating chemoresistance [85, 86]. In addition, stromal effects have been repeatedly shown to influence the motility and invasion of tumor cells, but how best to target these is an open question. Finally, while the immune checkpoint inhibitors have already improved outcomes in certain cancers, further study will be required to determine the optimal dosing, treatment duration, roles of maintenance therapy and combinations with other modalities going forward. While we have separately addressed the three domains of stemness, primordial motility, and microenvironment, it is clear that they are all interconnected, contributing to the difficulty that exists in fully understanding these processes. It has been over 150 years since Virchow published his observations linking embryogenesis to cancer histology, but there remain more lessons to be learned from developmental biology that undoubtedly can be applied to the treatment of cancer. However, the complexity of these processes is evident, and similar pathways may play vastly disparate roles in different cancers, underlining the need to carefully characterize them on a case-by-case basis. Despite the fact that a large number of unanswered questions remain, a myriad of other agents addressing these processes are on the horizon and promise to revolutionize the practice of clinical oncology.

Outstanding Questions (Box).

Do CSCs arise from SSCs themselves or from differentiated cells that de-differentiate?

Do bipotent progenitor cells influence tumor heterogeneity and therapeutic resistance?

Is individual cell motility or collective cell migration a better therapeutic target for preventing metastasis and is the answer tumor-dependent?

How is planar cell polarity disrupted in tumors?

Can restoring contact inhibition of locomotion in leader cells prevent tumor cell invasion into the surrounding stroma?

Is increased matrix stiffness targetable?

Are there any ways to address aberrant stroma to prevent disease recurrence?

What is the optimal dosing schedule and duration for immune checkpoint inhibitors to minimize toxicity and maintain durable disease responses?

What are the ideal combinations of conventional cytotoxic agents, targeted therapies, and immunotherapies to minimize toxicity and improve outcomes?

Trends in ontogenesis and cancer (Box).

Multiple processes required for normal ontogenesis are disrupted or reactivated in cancer.

Derangements in chromatin modification lead to differentiation arrest and play a critical role in tumor progression.

Cancer cells reactivate primordial mechanisms of motility to promote invasion and metastasis.

Microenvironmental factors are critically important in normal development and cancer pathogenesis.

Targeting developmental processes implicated in cancer has led to revolutionary advances in treatment.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by NCI grants R01CA138850 and R01CA169202, Department of Defense award W81XWH-14-1-0516, funds from the Breast Cancer Research Foundation of Alabama, and a Pilot Award from the UAB Diabetes Research Center (DRC)-UAB Comprehensive Diabetes Center (UCDC) to L. A. Shevde and NCI grant R01CA194048 and funds from Alabama Drug Discovery Alliance to R. S. Samant.

Glossary

- Polarity

The ordered orientation of cells and subcellular structures based on multiple axes, including the axis perpendicular to the basement membrane (apicobasal polarity) and the planar axis of a sheet of cells (planar cell polarity)

- Contact inhibition of locomotion

The phenomenon that cells cease moving in the same direction after contact with another cell of either the same type (homotypic CIL) or different type (heterotypic CIL). This is distinct from contact inhibition of proliferation, whereby continuing cell growth and division is impeded by contact with other cells

- Parenchyma

The functional elements of an organ or tissue, distinct from the stroma that supports it

- Ontogenesis

The process of development of an organ or organism from inception to maturity

- Gastrulation

A phase of development in which the embryo restructures itself from a single-layered blastula to a gastrula consisting of three germ layers: the ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm

- Delamination

Physical separation of epithelial cells from a cellular layer or structure

- Terminal end bud

Bulbous cellular structures that define the tips of elongating epithelial ducts during the development of the mammary gland

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hendrix MJ, et al. Reprogramming metastatic tumour cells with embryonic microenvironments. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7(4):246–55. doi: 10.1038/nrc2108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moyes LH, et al. Activation of Wnt signalling promotes development of dysplasia in Barrett's oesophagus. J Pathol. 2012;228(1):99–112. doi: 10.1002/path.4058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moraes RC, et al. Constitutive activation of smoothened (SMO) in mammary glands of transgenic mice leads to increased proliferation, altered differentiation and ductal dysplasia. Development. 2007;134(6):1231–42. doi: 10.1242/dev.02797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shenoy AK, et al. Transition from colitis to cancer: high Wnt activity sustains the tumor-initiating potential of colon cancer stem cell precursors. Cancer Res. 2012;72(19):5091–100. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-1806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dahmane N, et al. The Sonic Hedgehog-Gli pathway regulates dorsal brain growth and tumorigenesis. Development. 2001;128(24):5201–12. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.24.5201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shih HP, et al. ECM Signaling Regulates Collective Cellular Dynamics to Control Pancreas Branching Morphogenesis. Cell Rep. 2016;14(2):169–79. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.12.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Laklai H, et al. Genotype tunes pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma tissue tension to induce matricellular fibrosis and tumor progression. Nat Med. 2016;22(5):497–505. doi: 10.1038/nm.4082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dunwoodie SL. The role of hypoxia in development of the Mammalian embryo. Dev Cell. 2009;17(6):755–73. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rankin EB, Giaccia AJ. Hypoxic control of metastasis. Science. 2016;352(6282):175–80. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf4405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Habicht A, et al. A link between PDL1 and T regulatory cells in fetomaternal tolerance. J Immunol. 2007;179(8):5211–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.8.5211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schildberg FA, et al. Coinhibitory Pathways in the B7-CD28 Ligand-Receptor Family. Immunity. 2016;44(5):955–72. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flores I, et al. The longest telomeres: a general signature of adult stem cell compartments. Genes Dev. 2008;22(5):654–67. doi: 10.1101/gad.451008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holohan B, Wright WE, Shay JW. Cell biology of disease: Telomeropathies: an emerging spectrum disorder. J Cell Biol. 2014;205(3):289–99. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201401012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim NW, et al. Specific association of human telomerase activity with immortal cells and cancer. Science. 1994;266(5193):2011–5. doi: 10.1126/science.7605428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chiappori AA, et al. A randomized phase II study of the telomerase inhibitor imetelstat as maintenance therapy for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(2):354–62. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bruedigam C, et al. Telomerase inhibition effectively targets mouse and human AML stem cells and delays relapse following chemotherapy. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;15(6):775–90. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Salloum R, et al. A molecular biology and phase II study of imetelstat (GRN163L) in children with recurrent or refractory central nervous system malignancies: a pediatric brain tumor consortium study. J Neurooncol. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s11060-016-2189-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baerlocher GM, et al. Telomerase Inhibitor Imetelstat in Patients with Essential Thrombocythemia. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(10):920–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1503479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tefferi A, et al. A Pilot Study of the Telomerase Inhibitor Imetelstat for Myelofibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(10):908–19. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1310523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sada A, et al. Defining the cellular lineage hierarchy in the interfollicular epidermis of adult skin. Nat Cell Biol. 2016 doi: 10.1038/ncb3359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rios AC, et al. In situ identification of bipotent stem cells in the mammary gland. Nature. 2014;506(7488):322–7. doi: 10.1038/nature12948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang ZA, et al. Luminal cells are favored as the cell of origin for prostate cancer. Cell Rep. 2014;8(5):1339–46. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Desai TJ, Brownfield DG, Krasnow MA. Alveolar progenitor and stem cells in lung development, renewal and cancer. Nature. 2014;507(7491):190–4. doi: 10.1038/nature12930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tao L, van Bragt MP, Li Z. A Long-Lived Luminal Subpopulation Enriched with Alveolar Progenitors Serves as Cellular Origin of Heterogeneous Mammary Tumors. Stem Cell Reports. 2015;5(1):60–74. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2015.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sakr RA, et al. Targeted capture massively parallel sequencing analysis of LCIS and invasive lobular cancer: Repertoire of somatic genetic alterations and clonal relationships. Mol Oncol. 2016;10(2):360–70. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2015.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bock C, et al. DNA methylation dynamics during in vivo differentiation of blood and skin stem cells. Mol Cell. 2012;47(4):633–47. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ntziachristos P, Abdel-Wahab O, Aifantis I. Emerging concepts of epigenetic dysregulation in hematological malignancies. Nat Immunol. 2016;17(9):1016–24. doi: 10.1038/ni.3517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cicconi L, Lo-Coco F. Current management of newly diagnosed acute promyelocytic leukemia. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(8):1474–81. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martens JH, et al. PML-RARalpha/RXR Alters the Epigenetic Landscape in Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia. Cancer Cell. 2010;17(2):173–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.12.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.French C. NUT midline carcinoma. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14(3):149–50. doi: 10.1038/nrc3659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Loven J, et al. Selective inhibition of tumor oncogenes by disruption of super-enhancers. Cell. 2013;153(2):320–34. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Greenblatt SM, Nimer SD. Chromatin modifiers and the promise of epigenetic therapy in acute leukemia. Leukemia. 2014;28(7):1396–406. doi: 10.1038/leu.2014.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Erickson CA, Goins TL. Avian neural crest cells can migrate in the dorsolateral path only if they are specified as melanocytes. Development. 1995;121(3):915–24. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.3.915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kulesa PM, et al. Reprogramming metastatic melanoma cells to assume a neural crest cell-like phenotype in an embryonic microenvironment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(10):3752–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506977103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tsai JH, et al. Spatiotemporal regulation of epithelial-mesenchymal transition is essential for squamous cell carcinoma metastasis. Cancer Cell. 2012;22(6):725–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ocana OH, et al. Metastatic colonization requires the repression of the epithelial-mesenchymal transition inducer Prrx1. Cancer Cell. 2012;22(6):709–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lamouille S, Xu J, Derynck R. Molecular mechanisms of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15(3):178–96. doi: 10.1038/nrm3758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Takebe N, et al. Targeting Notch, Hedgehog, and Wnt pathways in cancer stem cells: clinical update. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2015;12(8):445–64. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2015.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Robinson GW, et al. Vismodegib Exerts Targeted Efficacy Against Recurrent Sonic Hedgehog-Subgroup Medulloblastoma: Results From Phase II Pediatric Brain Tumor Consortium Studies PBTC-025B and PBTC-032. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(24):2646–54. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.60.1591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.David NB, et al. Molecular basis of cell migration in the fish lateral line: role of the chemokine receptor CXCR4 and of its ligand, SDF1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(25):16297–302. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252339399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Theveneau E, et al. Collective chemotaxis requires contact-dependent cell polarity. Dev Cell. 2010;19(1):39–53. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Friedl P, et al. Classifying collective cancer cell invasion. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14(8):777–83. doi: 10.1038/ncb2548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cheung KJ, et al. Collective invasion in breast cancer requires a conserved basal epithelial program. Cell. 2013;155(7):1639–51. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.11.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mayor R, Etienne-Manneville S. The front and rear of collective cell migration. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2016;17(2):97–109. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2015.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jonsson M, et al. Loss of Wnt-5a protein is associated with early relapse in invasive ductal breast carcinomas. Cancer Res. 2002;62(2):409–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Witze ES, et al. Wnt5a directs polarized calcium gradients by recruiting cortical endoplasmic reticulum to the cell trailing edge. Dev Cell. 2013;26(6):645–57. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Safholm A, et al. The Wnt-5a-derived hexapeptide Foxy-5 inhibits breast cancer metastasis in vivo by targeting cell motility. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(20):6556–63. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mayor R, Carmona-Fontaine C. Keeping in touch with contact inhibition of locomotion. Trends Cell Biol. 2010;20(6):319–28. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Paddock SW, Dunn GA. Analysing collisions between fibroblasts and fibrosarcoma cells: fibrosarcoma cells show an active invasionary response. J Cell Sci. 1986;81:163–87. doi: 10.1242/jcs.81.1.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Astin JW, et al. Competition amongst Eph receptors regulates contact inhibition of locomotion and invasiveness in prostate cancer cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12(12):1194–204. doi: 10.1038/ncb2122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pylayeva Y, et al. Ras- and PI3K-dependent breast tumorigenesis in mice and humans requires focal adhesion kinase signaling. J Clin Invest. 2009;119(2):252–66. doi: 10.1172/JCI37160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang J, et al. A small molecule FAK kinase inhibitor, GSK2256098, inhibits growth and survival of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma cells. Cell Cycle. 2014;13(19):3143–9. doi: 10.4161/15384101.2014.949550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jiang H, et al. Targeting focal adhesion kinase renders pancreatic cancers responsive to checkpoint immunotherapy. Nat Med. 2016;22(8):851–60. doi: 10.1038/nm.4123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fata JE, Werb Z, Bissell MJ. Regulation of mammary gland branching morphogenesis by the extracellular matrix and its remodeling enzymes. Breast Cancer Res. 2004;6(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/bcr634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang DY, Friedman SL. Fibrosis-dependent mechanisms of hepatocarcinogenesis. Hepatology. 2012;56(2):769–75. doi: 10.1002/hep.25670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kai F, Laklai H, Weaver VM. Force Matters: Biomechanical Regulation of Cell Invasion and Migration in Disease. Trends Cell Biol. 2016;26(7):486–97. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2016.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cassereau L, et al. A 3D tension bioreactor platform to study the interplay between ECM stiffness and tumor phenotype. J Biotechnol. 2015;193:66–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2014.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pathak A, Kumar S. Independent regulation of tumor cell migration by matrix stiffness and confinement. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(26):10334–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1118073109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Campinho P, et al. Tension-oriented cell divisions limit anisotropic tissue tension in epithelial spreading during zebrafish epiboly. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15(12):1405–14. doi: 10.1038/ncb2869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Levental KR, et al. Matrix crosslinking forces tumor progression by enhancing integrin signaling. Cell. 2009;139(5):891–906. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Meissner EG, et al. Simtuzumab treatment of advanced liver fibrosis in HIV and HCV-infected adults: results of a 6-month open-label safety trial. Liver Int. 2016 doi: 10.1111/liv.13177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Benson A, et al. A phase 2 randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled study of simtuzumab or placebo in combination with gemcitabine for the first line treatment of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. ESMO 2014 Congress; 2014; Madrid, Spain. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hecht J, et al. A phase II, randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled study of simtuzumab or placebo in combination with FOLFIRI for the second line treatment of metastatic KRAS mutant colorectal adenocarcinoma. 2015 ASCO Annual Meeting; 2015; Chicago, IL. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang GL, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 is a basic-helix-loop-helix-PAS heterodimer regulated by cellular O2 tension. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92(12):5510–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.12.5510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mekhail K, et al. HIF activation by pH-dependent nucleolar sequestration of VHL. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6(7):642–7. doi: 10.1038/ncb1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Guimaraes-Camboa N, et al. HIF1alpha Represses Cell Stress Pathways to Allow Proliferation of Hypoxic Fetal Cardiomyocytes. Dev Cell. 2015;33(5):507–21. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Scully D, et al. Hypoxia promotes production of neural crest cells in the embryonic head. Development. 2016;143(10):1742–52. doi: 10.1242/dev.131912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lewis DM, et al. Intratumoral oxygen gradients mediate sarcoma cell invasion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(33):9292–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1605317113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yeung TM, Gandhi SC, Bodmer WF. Hypoxia and lineage specification of cell line-derived colorectal cancer stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(11):4382–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1014519107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Seidel S, et al. A hypoxic niche regulates glioblastoma stem cells through hypoxia inducible factor 2 alpha. Brain. 2010;133(Pt 4):983–95. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mathieu J, et al. HIF induces human embryonic stem cell markers in cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2011;71(13):4640–52. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cox TR, et al. The hypoxic cancer secretome induces pre-metastatic bone lesions through lysyl oxidase. Nature. 2015;522(7554):106–10. doi: 10.1038/nature14492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 73.Hu YL, et al. Hypoxia-induced autophagy promotes tumor cell survival and adaptation to antiangiogenic treatment in glioblastoma. Cancer Res. 2012;72(7):1773–83. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chen W, et al. Targeting Renal Cell Carcinoma with a HIF-2 antagonist. Nature. 2016 doi: 10.1038/nature19796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Plaks V, et al. Adaptive Immune Regulation of Mammary Postnatal Organogenesis. Dev Cell. 2015;34(5):493–504. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.O'Brien J, et al. Macrophages are crucial for epithelial cell death and adipocyte repopulation during mammary gland involution. Development. 2012;139(2):269–75. doi: 10.1242/dev.071696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.DeNardo DG, et al. Leukocyte complexity predicts breast cancer survival and functionally regulates response to chemotherapy. Cancer Discov. 2011;1(1):54–67. doi: 10.1158/2159-8274.CD-10-0028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ries CH, et al. Targeting tumor-associated macrophages with anti-CSF-1R antibody reveals a strategy for cancer therapy. Cancer Cell. 2014;25(6):846–59. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Nywening TM, et al. Targeting tumour-associated macrophages with CCR2 inhibition in combination with FOLFIRINOX in patients with borderline resectable and locally advanced pancreatic cancer: a single-centre, open-label, dose-finding, non-randomised, phase 1b trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(5):651–62. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)00078-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Nishimura H, et al. Autoimmune dilated cardiomyopathy in PD-1 receptor-deficient mice. Science. 2001;291(5502):319–22. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5502.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Jin LP, Fan DX, Li DJ. Regulation of costimulatory signal in maternal-fetal immune tolerance. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2011;66(2):76–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2010.00982.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Attanasio J, Wherry EJ. Costimulatory and Coinhibitory Receptor Pathways in Infectious Disease. Immunity. 2016;44(5):1052–68. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Leach DR, Krummel MF, Allison JP. Enhancement of antitumor immunity by CTLA-4 blockade. Science. 1996;271(5256):1734–6. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5256.1734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Carlino MS, Long GV. Ipilimumab Combined with Nivolumab: A Standard of Care for the Treatment of Advanced Melanoma? Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22(16):3992–8. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-2944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zheng X, et al. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition is dispensable for metastasis but induces chemoresistance in pancreatic cancer. Nature. 2015;527(7579):525–30. doi: 10.1038/nature16064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Fischer KR, et al. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition is not required for lung metastasis but contributes to chemoresistance. Nature. 2015;527(7579):472–6. doi: 10.1038/nature15748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Thiery JP, et al. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in development and disease. Cell. 2009;139(5):871–90. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]