ABSTRACT

Two-component systems are widespread in bacteria, allowing adaptation to environmental changes. The classical pathway is composed of a histidine kinase that phosphorylates an aspartate residue in the cognate response regulator (RR). RRs lacking the phosphorylatable aspartate also occur, but their function and contribution during host-pathogen interactions are poorly characterized. AtvR (PA14_26570) is the only atypical response regulator with a DNA-binding domain in the opportunistic pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Macrophage infection with the atvR mutant strain resulted in higher levels of tumor necrosis factor alpha secretion as well as increased bacterial clearance compared to those for macrophages infected with the wild-type strain. In an acute pneumonia model, mice infected with the atvR mutant presented increased amounts of proinflammatory cytokines, increased neutrophil recruitment to the lungs, reductions in bacterial burdens, and higher survival rates in comparison with the findings for mice infected with the wild-type strain. Further, several genes involved in hypoxia/anoxia adaptation were upregulated upon atvR overexpression, as seen by high-throughput transcriptome sequencing (RNA-Seq) analysis. In addition, atvR was more expressed in hypoxia in the presence of nitrate and required for full expression of nitrate reductase genes, promoting bacterial growth under this condition. Thus, AtvR would be crucial for successful infection, aiding P. aeruginosa survival under conditions of low oxygen tension in the host. Taken together, our data demonstrate that the atypical response regulator AtvR is part of the repertoire of transcriptional regulators involved in the lifestyle switch from aerobic to anaerobic conditions. This finding increases the complexity of regulation of one of the central metabolic pathways that contributes to Pseudomonas ubiquity and versatility.

KEYWORDS: atypical response regulator, hypoxia, macrophage, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, response regulator, virulence, anaerobic respiration, denitrification

INTRODUCTION

Two-component systems (TCSs) are signaling pathways that are widespread in bacteria and that sense and respond to environmental changes. These systems are also found in Archaea and Eukarya, but there is no evidence of their presence in animals (1), making these pathways good anti-infective drug targets.

The canonical TCS pathway has a histidine kinase that is autophosphorylated in response to an input signal and transfers its phosphoryl group to a cognate response regulator (RR). Once phosphorylated, the RR becomes active and initiates an appropriate cellular response to the initial stimulus, often by modulating gene expression (2–4).

Response regulators have a REC domain with a conserved secondary structure [(βα)5] important for their activity. The REC domain classically possesses residues critical for RR activation, which includes an aspartate at the end of the third β-strand that can be phosphorylated by the histidine kinase (HK) (5). Despite their conservation, some RRs lack this aspartate residue or other conserved features and thus are considered atypical response regulators. A particular subgroup of atypical RRs, named aspartate-less receivers (ALR), was recently described, and proteins that belong to this subfamily have the replacement of an aspartate by any other amino acid (with the exception of tryptophan) in the phosphorylatable site (6).

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a ubiquitous Gram-negative bacterium able to cause disease in several hosts (7–9) and one of the major causes of hospital-acquired infections, such as acute pneumonia in ventilator-assisted patients, which is associated with high rates of mortality. This bacterium is also one of the major pathogens in the lungs of individuals with cystic fibrosis, leading to chronic pulmonary infection and impairment of quality of life (10–12).

Macrophages are at the first line of defense, recognizing the pathogen and orchestrating the host immune response against P. aeruginosa infection. The recognition of pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) relies on their association with the cognate Toll-like receptors (TLR) in the immune cells, stimulating several signaling cascades, such as the proinflammatory NF-κB and mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways, leading to the production of cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and IL-1 (13).

During acute lung injury, both airway edema and atelectasis result in low-ventilation and low-perfusion conditions, leading to a hypoxic environment within the affected areas of the lungs (14–16). The hostility posed by this environment induces several signaling pathways in P. aeruginosa, including the TCS NarXL. At the top of the anoxic response regulatory cascade is the transcriptional regulator Anr, whose activity is dependent on low oxygen levels. Anr is essential for P. aeruginosa growth in anoxia (17), inducing expression of the nitrate reductase gene (nar) clusters, important for anaerobic respiration via denitrification, as well as the transcriptional regulators narXL and dnr. The NarXL TCS responds to nitrate and nitrite, directly activates expression of the nar clusters, and indirectly regulates other denitrification genes via Dnr, a transcriptional factor that positively regulates the nir (nitrite reductase), nor (nitric oxide reductase), and nos (nitrous oxide reductase) gene clusters (18, 19). The timing of expression of the denitrification genes is consistent with the position of the role of their products in this electron transport chain. In the absence of oxygen and nitrate, P. aeruginosa can also use a fermentative state using the arginine deiminase pathway (arc gene clusters) or the pyruvate pathway (18). In hypoxia, the virulence factor pyocyanin also acts as a terminal electron receptor (18, 20).

P. aeruginosa has one of the largest sets of two-component systems known in bacteria, and these TCSs certainly contribute to its ability to thrive in a wide range of niches, including humans. P. aeruginosa PA14 presents at least 64 sensor kinases and 76 response regulators (2, 21–23). Using a bioinformatics approach, Maule and collaborators suggested that four P. aeruginosa RRs belong to the ALR subfamily (PA14_30650, PA14_26570, PA14_64050, PA14_03470) (6). About 4% of all analyzed REC domains in bacteria belong to this subfamily, highlighting the particular importance of the further characterization of these still unappreciated RRs.

No atypical RR in P. aeruginosa has been characterized to date, and in fact, these RRs are poorly characterized in other bacteria as well. Here we studied PA14_26570, a member of the ALR subfamily that possesses a DNA-binding domain. We show that the atypical RR PA14_26570, here named AtvR (atypical virulence-related response regulator), is important for P. aeruginosa virulence, activating the transcription of several genes involved in the hypoxia/anoxia response, as well as virulence-related genes. We also found that a strain lacking AtvR is less virulent in both in vitro and in vivo infection models. Taken together, our data demonstrate that AtvR should be underscored as an important contributor to the bacterium's arsenal against host defenses.

RESULTS

AtvR (PA14_26570) belongs to the ALR subfamily of response regulators.

A multiple-sequence alignment using P. aeruginosa RR REC domains was performed. This domain's secondary structure is conserved across the RRs, as is the position of the aspartate that receives the phosphoryl group at the end of the third β-strand in classical RRs (Fig. 1, marked with an asterisk) (5). The CheY (PA14_45620) secondary structure was used as a representative of a typical REC domain in this analysis. In addition to the previously identified atypical response regulators in P. aeruginosa, we identified PA14_36920, which belongs to the aspartate-less receiver (ALR) subfamily (Fig. 1). In contrast to Maule et al. (6), who characterized the members of the ALR subfamily in several bacteria, a more refined analysis of only P. aeruginosa proteins was performed here. The proteins PA14_30650 and PA14_64050, classified by Maule et al. (6) to be atypical RRs, have an aspartate at the end of their third β-strand, characterizing them as typical RRs (Fig. 1). Moreover, PA14_30650 is the well-characterized GacA RR, phosphorylated by the HK GacS (24). PA14_64050 is annotated as GcbA, an RR containing a GGDEF domain in its C terminus (25).

FIG 1.

Multiple-sequence alignment of REC domains. Alignment of the REC domains from selected P. aeruginosa response regulators was performed with MUSCLE software. Green arrows above the sequences, β-sheets; blue rectangles, α-helices in the secondary structure; blue highlights, conserved residues in the catalytic active pocket in classical RRs; orange highlights, divergent residues in the atypical RRs PA14_03470, AtvR, and PA14_36920; asterisk, the phosphorylatable aspartate in classical RRs replaced by a glutamate in atypical RRs. The numbers correspond to the amino acid positions in the primary structure of each protein. The sequences were obtained from www.pseudomonas.com.

AtvR sequence analysis showed two conserved domains, a REC domain and a helix-turn-helix (HTH) DNA-binding domain. This architectural structure is typical of that of the NarL family of response regulators (2). AtvR has one substitution in a conserved amino acid that is important for the stabilization of the phosphorylated aspartate (D15S) and in the phosphorylatable aspartate itself (D61E) (Fig. 1). Replacement of an aspartate by a glutamate usually leads to an always-on state by mimicking an active conformation state (26–28); therefore, the activity of AtvR is inferred to be independent of phosphorylation. Hence, AtvR activity should be constitutive and independent of a cognate histidine kinase, and its presence in the cell is probably enough for its transcription-inducing activity.

AtvR is important for virulence against macrophages in vitro.

Macrophages play an important role against P. aeruginosa infections, leading to bacterial clearance and cytokine production. Pathogenic bacteria use several strategies to adapt to the host, among them being the inhibition of macrophage activation, which results in the reduction of both cytokine secretion and bacterial clearance (29). We asked whether AtvR would lead to bacterium adaptation to macrophages during infection, thus increasing P. aeruginosa virulence. To answer this question, we used an in vitro infection model with J774 macrophages incubated with the wild-type bacteria or the atvR deletion mutant (the ΔatvR mutant). First, we ascertained that the ΔatvR mutant grows as well as the wild type under conditions similar to those used in the macrophage infection assay (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

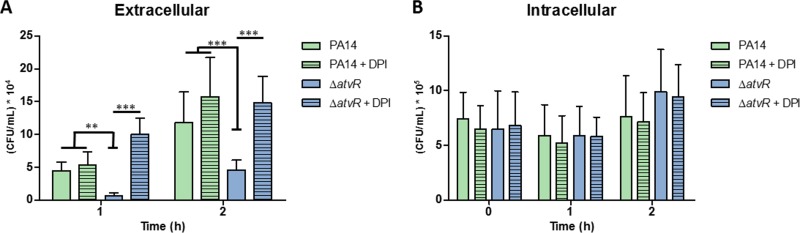

Macrophages were infected and incubated for 1 h prior to gentamicin addition to kill extracellular bacteria. After 30 min (time zero), the cells were washed and fresh medium without antibiotics was added. The number of CFU of extracellular bacteria in the culture supernatants was assessed at 1 and 2 h (Fig. 2A). Macrophages were washed and lysed at 0, 1, and 2 h, and the released bacteria were enumerated (intracellular bacteria) (Fig. 2B). The counts of phagocytosed bacteria were similar in macrophages infected with the wild type and those infected with the ΔatvR mutant at all time points, suggesting no differences in the internalization process. However, we observed a difference in the numbers of CFU of extracellular bacteria of the ΔatvR mutant and wild-type strain PA14 (Fig. 2A), indicating a role of AtvR in counteracting macrophage-mediated killing, leading to increased bacterial survival or reducing the amounts of harmful molecules produced by macrophages, such as reactive oxygen species. To uncover the oxidative state of macrophages responding to wild-type PA14 or the ΔatvR strain, they were incubated with diphenyleneiodonium (DPI), an NADPH oxidase inhibitor, prior to infection. In this setting, there were increased extracellular bacterial counts when macrophages were treated with DPI and infected with the ΔatvR mutant (compare the results for the ΔatvR mutant and the ΔatvR mutant from macrophages treated with DPI [ΔatvR + DPI] in Fig. 2A). The increase in the counts of extracellular PA14 bacteria from DPI-treated macrophages was less pronounced, indicating that the wild-type strain by itself is able to decrease the macrophage redox response, as we had already observed (29). The phagocytosis rate was the same when macrophages were treated or not treated with DPI, and the numbers of intracellular bacteria remained the same for all settings (Fig. 2B).

FIG 2.

AtvR is important for resistance to macrophages and affects their activation. J774 macrophages were treated with DPI for 4 h. Control and DPI-treated macrophages were incubated with P. aeruginosa PA14 or the ΔatvR mutant at an MOI of 10. (A) The cells were washed with PBS, R-10 medium containing 200 μg/ml gentamicin was added to the wells, the plate was incubated for 30 min, the wells were washed, and fresh medium was added. At the indicated time points, the supernatants were collected and diluted, and the number of CFU of extracellular bacteria was determined. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. (B) The macrophages were infected, treated as described in the legend to panel A, and lysed with Triton X-100. The released bacteria were diluted, and the number of CFU of intracellular bacteria was determined.

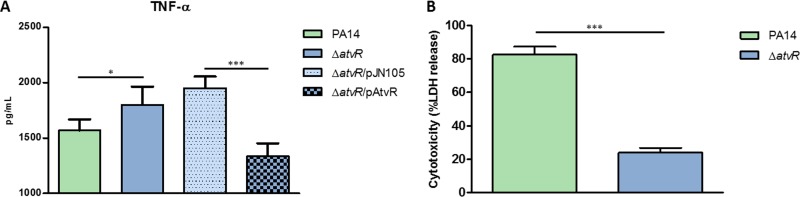

To determine if P. aeruginosa AtvR modulates macrophage activation, macrophages were infected with PA14, the ΔatvR mutant, the ΔatvR/pJN105 mutant (the ΔatvR mutant carrying an empty vector), or the ΔatvR/pAtvR mutant (the ΔatvR mutant carrying pAtvR, which is a pJN105 plasmid harboring atvR under the control of an arabinose-inducible promoter). After 3 h, supernatants were recovered and TNF-α levels were measured. Macrophages infected with the ΔatvR mutant secreted more TNF-α than macrophages infected with PA14 (Fig. 3A). This higher level of TNF-α production was due to a direct effect of the absence of AtvR, since the level of TNF-α secretion by macrophages infected with the complemented strain (the ΔatvR/pAtvR mutant) was restored to the wild-type level (Fig. 3A). Macrophage survival of bacterial infection was also increased when the macrophages were coincubated with the ΔatvR mutant over that when they were coincubated with PA14 (Fig. 3B), indicating that the AtvR function is needed for efficient killing of macrophages.

FIG 3.

AtvR is important for virulence in a macrophage in vitro model. J774 macrophages were incubated with P. aeruginosa PA14 or the ΔatvR, ΔatvR/pJN105, or ΔatvR/pAtvR mutant at an MOI of 10. (A) After 3 h of infection, the supernatants were recovered and the level of TNF-α secretion was determined by ELISA. (B) For the cytotoxicity assay, after 2 h of infection, LDH release was determined as a measure of macrophage death. Data are the means ± SDs from three independent experiments performed in triplicate. *, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001.

These in vitro infection results suggest that AtvR has a role in P. aeruginosa virulence, leading to higher bacterial counts and decreasing macrophage activation and survival. This hypothesis is strengthened by the results of the DPI assay, in which NADPH oxidase inhibition precludes the ability of the macrophages to kill ΔatvR bacteria (Fig. 2). We also found that AtvR positively regulates the expression of genes such as katA and rahU (Table 1), as discussed below, which are involved in modulating the oxidative status of macrophages (30, 31).

TABLE 1.

Genes differentially expressed in PA14/pAtvR and PA14/pJN105

| Function and PA14 locus | PAO1 locus | Gene | Fold change in expression |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nitrate reductase | |||

| PA14_13750 | PA3877 | narK1 | 3.62 |

| PA14_13770 | PA3876 | narK2 | 5.44 |

| PA14_13780 | PA3875 | narG | 10.23 |

| PA14_13800 | PA3874 | narH | 10.67 |

| PA14_13810 | PA3873 | narJ | 9.09 |

| PA14_13830 | PA3872 | narI | 9.61 |

| PA14_13840 | PA3871 | 4.34 | |

| PA14_13850 | PA3870 | moaA | 2.71 |

| Nitrite reductase | |||

| PA14_06650 | PA0509 | nirN | 5.80 |

| PA14_06660 | PA0510 | nirE | 9.51 |

| PA14_06670 | PA0511 | nirJ | 7.20 |

| PA14_06680 | PA0512 | nirH | 5.86 |

| PA14_06690 | PA0513 | nirG | 5.05 |

| PA14_06700 | PA0514 | nirL | 4.49 |

| PA14_06710 | PA0515 | nirD | 3.80 |

| PA14_06720 | PA0516 | nirF | 3.23 |

| PA14_06730 | PA0517 | nirC | 3.93 |

| PA14_06740 | PA0518 | nirM | 4.58 |

| PA14_06750 | PA0519 | nirS | 3.23 |

| PA14_06790 | PA0521 | nirO | 2.41 |

| PA14_06770 | PA0520 | nirQ | 2.82 |

| Nitric oxide reductase | |||

| PA14_06810 | PA0523 | norC | 6.12 |

| PA14_06830 | PA0524 | norB | 7.44 |

| Nitrous oxide reductase | |||

| PA14_20190 | PA3393 | nosD | 4.02 |

| PA14_20200 | PA3392 | nosZ | 7.53 |

| Arginine metabolism | |||

| PA14_68330 | PA5171 | arcA | 2.29 |

| PA14_68340 | PA5172 | arcB | 4.34 |

| PA14_68350 | PA5173 | arcC | 5.42 |

| QS regulated | |||

| PA14_36330 | PA2193 | hcnA | 2.01 |

| PA14_36320 | PA2194 | hcnB | 3.19 |

| PA14_36310 | PA2195 | hcnC | 4.46 |

| PA14_16250 | PA3724 | lasB | 2.23 |

| PA14_19100 | PA3479 | rhlA | 2.60 |

| Phenazine biosynthesis | |||

| PA14_09400 | PA4217 | phzS | 3.70 |

| PA14_09410 | PA4216 | phzG1 | 7.16 |

| PA14_09420 | PA4215 | phzF1 | 4.71 |

| PA14_09440 | PA4214 | phzE1 | 5.88 |

| PA14_09450 | PA4213 | phzD1 | 6.38 |

| PA14_09460 | PA4212 | phzC1 | 9.14 |

| PA14_09470 | PA4211 | phzB1 | 9.95 |

| PA14_09480 | PA4210 | phzA1 | 6.11 |

| PA14_09490 | PA4209 | phzM | 2.69 |

| PA14_39880 | PA1905 | phzG2 | 3.97 |

| PA14_39890 | PA1904 | phzF2 | 4.71 |

| PA14_39910 | PA1903 | phzE2 | 5.38 |

| PA14_39925 | PA1902 | phzD2 | 6.52 |

| PA14_39945 | PA1901 | phzC2 | 5.42 |

| PA14_39960 | PA1900 | phzB2 | 6.57 |

| PA14_39970 | PA1899 | phzA2 | 3.55 |

| Redox related | |||

| PA14_01490 | PA0122 | rahU | 2.10 |

| PA14_09150 | PA4236 | katA | 2.33 |

| Type VI secretion systems | |||

| PA14_00820 | PA0070 | tagQ1 | 2.09 |

| PA14_01030 | PA0085 | hcp1 | 2.11 |

| PA14_44290 | PA1656 | hsiA2 | 2.06 |

| PA14_43040 | PA1657 | hsiB2 | 3.27 |

| PA14_43030 | PA1658 | hsiC2 | 3.00 |

| PA14_43020 | PA1659 | 2.46 | |

| PA14_43000 | PA1660 | hsiG2 | 2.58 |

| PA14_42990 | PA1661 | hsiH2 | 2.48 |

| PA14_42980 | PA1662 | clpV2 | 2.50 |

| PA14_42970 | PA1663 | sfa2 | 2.35 |

| PA14_42950 | PA1665 | fha2 | 3.68 |

| PA14_42940 | PA1666 | lip2.1 | 2.76 |

| PA14_42920 | PA1667 | hsiJ2 | 2.10 |

| PA14_42910 | PA1668 | dotU2 | 2.74 |

| PA14_42900 | PA1669 | icmF2 | 2.19 |

| PA14_34020 | PA2368 | hsiF3 | 60.50 |

AtvR is essential for full P. aeruginosa virulence in vivo.

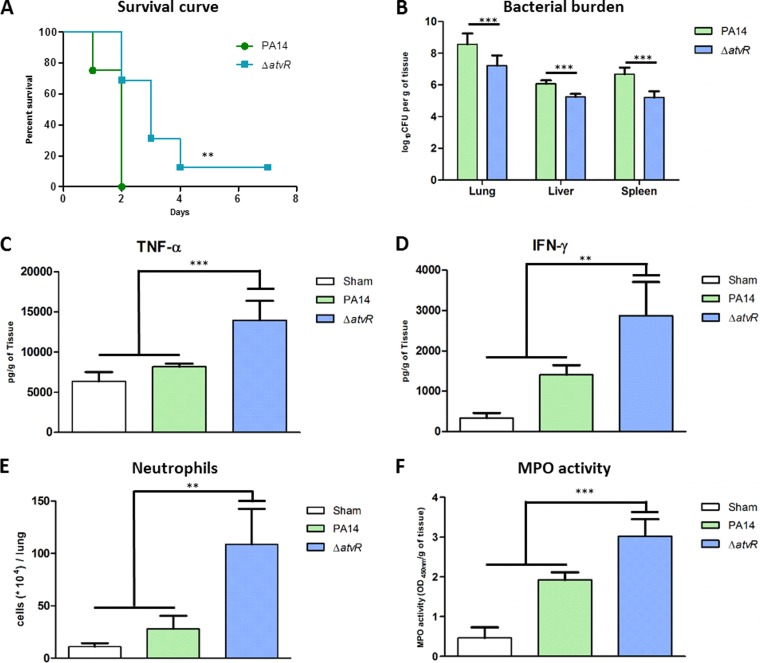

Since AtvR was involved in virulence in vitro, the next step was to ascertain whether this atypical RR was also relevant in a mouse model of acute pneumonia. All mice infected intratracheally (i.t.) with PA14 were dead at 48 h postinfection (h.p.i.), while mice infected with the ΔatvR strain had higher survival rates, with 68% of the animals still being alive at 48 h.p.i. and 12% of the animals being alive after 7 days (Fig. 4A).

FIG 4.

AtvR is important for P. aeruginosa virulence in a mouse model of acute pneumonia. BALB/c mice were infected i.t. with 2 × 106 bacteria of the wild-type strain PA14 or the ΔatvR mutant. (A) Mouse survival was followed during the course of the experiment. (B) At 24 h postinfection, animals were sacrificed, the organs were macerated, and the bacterial CFU were enumerated. (C, D) The levels of the cytokines TNF-α (C) and IFN-γ (D) in the lungs were determined by ELISA. (E) The animals were euthanized, the lungs were macerated, and the cell suspensions were labeled for neutrophils (Ly6G/Ly6C+, F4/80−) and analyzed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting. (F) The lung cells were lysed by sonication, and the suspension was centrifuged. The resulting supernatant was used for the MPO activity assay with TMB, and the OD at 450 nm was measured. (B to F) For all assays, samples were collected at 24 h postinfection. Data are the means ± SDs from three independent experiments. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

In this infection model, P. aeruginosa spreads quickly and reaches other organs, leading to animal death (29, 32). We assessed the bacterial burden in the primary infection site (lungs) as well as in secondary organs (liver and spleen) as an indication of sepsis. These organs were recovered at 24 h.p.i., and the bacterial load was evaluated. Animals infected with the ΔatvR mutant showed reduced bacterial burdens in all organs compared to those in wild-type strain-infected animals (Fig. 4B). This demonstrates that AtvR interferes with the host response against the bacterium, leading to reduced resolution of the bacterial infection by the host infected with wild-type strain PA14.

Because AtvR affects cytokine production in vitro (Fig. 3A), we asked whether AtvR also decreased immune system activation as well as neutrophil recruitment to the primary infection site. TNF-α and gamma interferon (IFN-γ) levels in the infected lungs were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) at 24 h.p.i., and the results showed that mice infected with the ΔatvR mutant released higher levels of both cytokines than PA14-infected or control mice (Fig. 4C and D). Higher levels of neutrophil (Ly6G/Ly6C+, CD11b+, F4/80−) recruitment were also found in mice infected with the ΔatvR mutant than wild-type strain-infected or sham-infected mice (Fig. 4E). Myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity was observed in infected and control mice, but it was higher in animals infected with the ΔatvR mutant than in control or PA14-infected mice, confirming that the recruited neutrophils were activated and necessary for the full immune response (Fig. 4F). The numbers of macrophages in the lungs were similar for mice infected with either the wild-type or the mutant strain (data not shown), but the in vitro data suggest that they were activated more efficiently when mice were infected with the ΔatvR strain than when they were infected with PA14, recruiting more neutrophils to the infection site.

These results indicate the relevance of AtvR in promoting P. aeruginosa adaptation in the host, by disrupting immune activation and reducing proinflammatory cytokine production and neutrophil recruitment as well as their activation, thus promoting higher rates of host mortality.

AtvR affects expression of genes related to adaptation to low O2 levels and virulence.

To better understand the contribution of AtvR to P. aeruginosa adaptation to the host, which leads to higher virulence, we performed a high-throughput transcriptome sequencing (RNA-Seq) analysis to identify genes regulated by AtvR. The AtvR-overexpressing strain (PA14/pAtvR) and a control strain (PA14/pJN105) were grown under inducing conditions until the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) was 1.0 at 37°C. A total of 287 genes were found to be differentially expressed; of these, 224 genes were upregulated (Table S3) and 63 genes were downregulated (Table S4) in PA14/pAtvR compared to their levels of regulation in PA14/pJN105. It is noteworthy that 44 out of 224 upregulated genes (19.6%) belong to nine gene clusters involved in anaerobic respiration in the presence of nitrate (Table 1). These genes include genes encoding the complete denitrification pathway for nitrate reduction to molecular nitrogen, comprising the nitrate reductase (nar and nap), nitrite reductase (nir), nitric oxide reductase (nor), and nitrous oxide reductase (nos) gene clusters. The arc operon, which is required for fermentative growth of P. aeruginosa on arginine, and clusters related to pyocyanin biosynthesis (phz) were also upregulated (Table 1). These results suggest a role of AtvR in the regulation of anaerobic/hypoxic metabolism.

Because Anr also directly or indirectly regulates all denitrification clusters, we compared our data with those for the Anr regulon previously described (17). We found that only about 16% of the Anr regulon was also under the control of AtvR and 89% of the AtvR regulon was not under the control of Anr (Fig. S2). The AtvR regulon includes genes for type VI secretion systems, lasB, rahU (see below), and the operon that comprises the aer2 aerotaxis transducer, which are not affected by the anr mutation (17, 33).

Some genes known to be relevant for virulence were also upregulated in the PA14/pAtvR strain, such as hcnA, lasB, katA, rahU, and genes for pyocyanin synthesis and type VI secretion systems (30, 31, 34–36). Catalase and RahU are implicated in modulating the production of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species, respectively, shutting down the macrophage response and therefore allowing an effective infection by P. aeruginosa (30, 31).

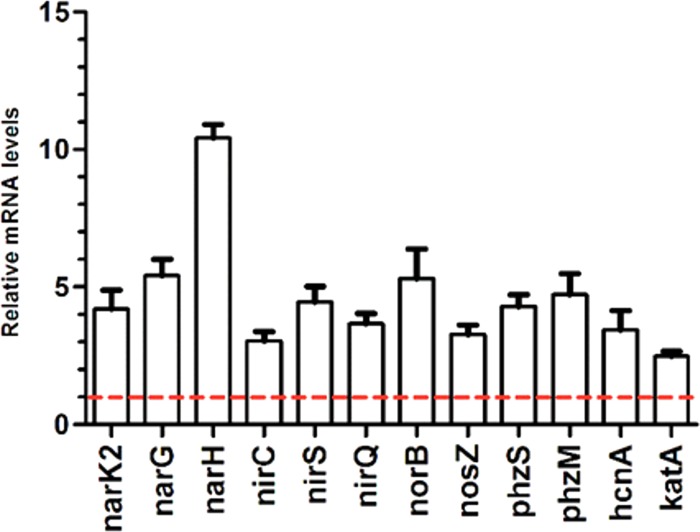

To validate the involvement of AtvR in the expression of denitrification and other genes, the transcription levels of nar (narK1, narG, and narH), nir (nirC, nirS, and nirQ), and phenazine biosynthetic genes (phzS, phzM), as well as cyanate biosynthesis (hcnA) and catalase (katA) genes, in the ΔatvR/pJN105 and ΔatvR/pAtvR strains were compared. Quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) analysis of these genes confirmed their increased expression levels in the ΔatvR strain complemented for AtvR compared to their expression levels in the control, the ΔatvR/pJN105 mutant (Fig. 5). This finding supports the direct or indirect transcriptional regulation of genes involved in denitrification and virulence by AtvR and is consistent with the RNA-Seq data.

FIG 5.

AtvR transcriptionally regulates denitrification and virulence-related genes. Quantitative RT-PCR was performed using cDNA made by reverse transcription of total RNA from ΔatvR/pJN105 or ΔatvR/pAtvR cells grown to an OD600 of 1 in LB medium at 37°C with 0.2% arabinose and 50 μg/ml gentamicin under agitation. Results are shown as values relative to the value for the ΔatvR/pJN105 control strain, which was considered 1 (red dashed line). Data are the means ± SDs from at least three independent experiments.

AtvR expression is induced in the presence of low O2 levels and nitrate.

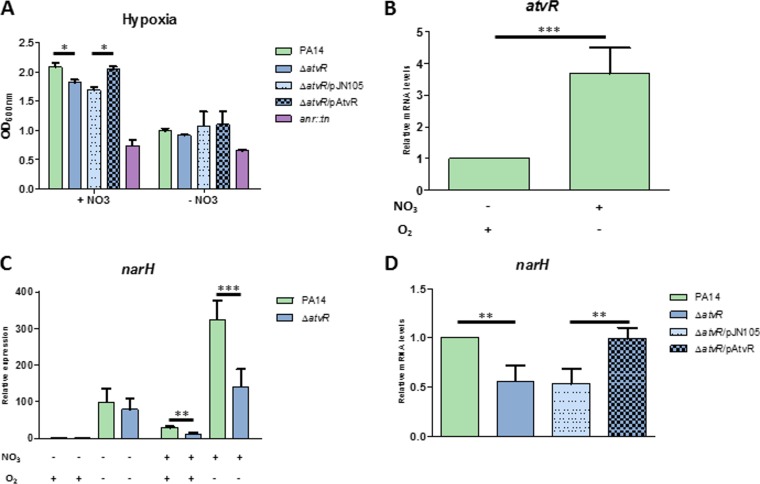

Because AtvR regulates genes involved in the response to hypoxia and anoxia at the transcriptional level, we asked whether this atypical RR is involved in P. aeruginosa fitness in the presence of a low O2 supply by regulating gene expression under this stressful condition. The PA14, ΔatvR, ΔatvR/pJN105, ΔatvR/pAtvR, and Δanr strains were grown under conditions of low O2 tension with or without nitrate; alternatively, these strains were grown in normoxia with shaking. The Δanr mutant was included as a hypoxia/anoxia-sensitive control (17, 37). After 24 h under low-O2 conditions or 3 h of normoxia, the OD600 was measured and RNA was extracted. Under these conditions, no differences in the growth of cultures submitted to low O2 levels without nitrate were observed (Fig. 6A). However, in the presence of nitrate and low levels of O2, cultures of the ΔatvR or ΔatvR/pJN105 strain presented significant cell growth that was slightly lower than that of wild-type PA14 or the ΔatvR/pAtvR complemented strain, suggesting that AtvR may sense the presence of nitrate (Fig. 6A).

FIG 6.

AtvR is expressed during low oxygen levels and regulates denitrification genes. (A) The wild-type PA14 strain, the ΔatvR, ΔatvR/pJN105, and ΔatvR/pAtvR strains, and the control Δanr strain were grown under hypoxic conditions with or without 50 mM nitrate, and the OD600 was determined after 24 h. (B, C) Total RNA was extracted from the PA14 and ΔatvR strains in normoxia or hypoxia with or without 50 mM nitrate, as indicated at the bottom. (B) Level of atvR expression relative to that in the PA14 strain grown in normoxia without nitrate. (C) The level of expression of narH was determined under different conditions; the data were plotted relative to those for the PA14 strain grown in normoxia without nitrate. (D) The level of expression of narH during hypoxia with nitrate was analyzed and normalized to the levels in PA14 under the same conditions. Data are the means ± SDs from at least three independent experiments. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

atvR expression was higher when PA14 was grown in the presence of low O2 levels with nitrate than when it was grown in normoxia, indicating a role for AtvR under the former conditions (Fig. 6B). To strengthen this hypothesis, the expression of narH, one of the genes from the nitrate reductase cluster identified in the RNA-Seq analysis, presented mRNA levels reduced 2-fold in the ΔatvR mutant compared to those in the wild type in the presence of nitrate in both hypoxia and normoxia (Fig. 6C). As expected, the complemented strain restored the level of narH expression to wild-type levels (Fig. 6D).

AtvR acts in parallel to the Anr-NarXL-Dnr denitrification regulatory cascade.

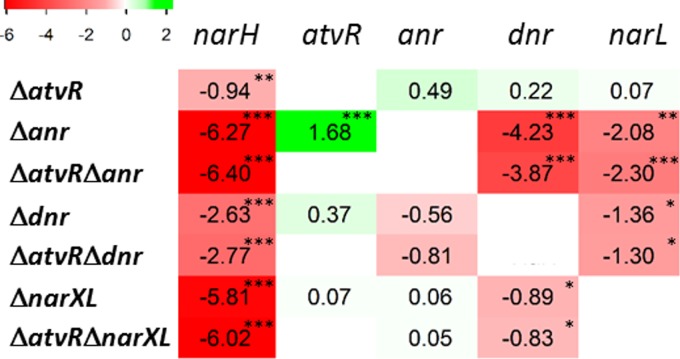

To investigate whether the AtvR regulatory role acts in concert with the denitrification regulatory pathway, strains with a deletions of anr, dnr, or narXL were constructed both in the wild type and in the ΔatvR mutant backgrounds, and the AtvR-overexpressing plasmid pAtvR or the control plasmid pJN105 was introduced into the mutants. Because the anr mutant barely grew under our low-O2 conditions, all strains were incubated in LB medium with 50 mM KNO3 under normoxic conditions until the OD600 was 2. At this point, cultures were transferred to a candle jar and total RNA was extracted after 4 h. In this setting, no growth differences were observed for any strain in normoxia (Fig. S1) and hypoxia (data not shown).

AtvR has no effect on the levels of anr, dnr, and narL mRNA, while the other transcriptional factors, Anr, Dnr, and NarXL, are part of an intricate regulatory network in which Anr is the master, inducing dnr and narL expression (Fig. 7 and S3) (18). As expected, we observed that Dnr and NarXL do not control anr expression but they regulate each other, as a lack of dnr resulted in lower levels of expression of narL and a lack of narXL led to reduced dnr mRNA levels. Dnr and NarXL had no influence on atvR mRNA levels, but, surprisingly, Anr had a negative role (Fig. 7 and S3).

FIG 7.

AtvR is not part of the known denitrification regulatory cascade, and it is repressed by Anr under low O2 levels. The wild-type PA14/pJN105 strain and the ΔatvR/pJN105, Δanr/pAtvR, Δdnr/pJN105, ΔnarXL/pJN105, ΔatvRΔanr/pJN105, ΔatvRΔdnr/pJN105, and ΔatvRΔnarXL/pJN105 mutants were grown in LB medium with 50 mM nitrate under aerobic conditions until the OD600 was 2. At this time point, cell cultures were transferred to a candle jar for 4 h, RNA was extracted, and qRT-PCR was performed for the genes indicated at the top. Relative expression levels for each gene were normalized to those in PA14/pJN105 and are depicted as log2 values. The upregulated genes are marked in green and the downregulated in red, with shades corresponding to the degree of regulation. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

To further dissect the role of AtvR in regulating the expression of denitrification genes, we evaluated the effect of combining the atvR deletion with the anr, dnr, and narXL deletions on narH mRNA levels. As expected, we observed a reduction of ∼70-fold and a reduction of ∼60-fold in narH mRNA levels in the Δanr and ΔnarXL strains, respectively, compared to those in the wild-type strain. A 6-fold reduction was observed in the Δdnr strain, which is also in agreement with previously described data (19). As we observed before (Fig. 6A), a lack of AtvR resulted in a 2-fold reduction in the level of narH compared to that in the wild type (Fig. 7). It is important to note that narH expression was not restored by AtvR overexpression in the single, double, or triple mutants, but it was in the ΔatvR strain (Fig. S3).

These data, added to the fact that the growth of the Δanr mutant in the presence of low O2 levels was not complemented by overexpression of AtvR (not shown), suggest that AtvR does not have an additive function with the functions of Anr, Dnr, or NarXL on narH expression and that AtvR may control denitrification gene expression in an alternative manner.

DISCUSSION

Two-component systems are among the most studied signaling pathways in bacteria. Atypical RRs, especially those with a replacement of the phosphorylatable aspartate by glutamate, probably lack phosphorylation control and, therefore, the histidine kinase-mediated signal transduction pathway. Atypical response regulators with DNA-binding domains are associated with several functions, such as regulating Helicobacter pylori cell growth, controlling Streptomyces development, and inducing a pathway that results in Synechococcus sp. bleaching under conditions of nutrient deprivation. To our knowledge, the only atypical RR previously associated with virulence was Chlamydia trachomatis ChxR, but this was inferred by the regulation of putative virulence genes, and no evidence of a direct link of this atypical RR to infection has been shown (38–46).

The importance of an atypical RR to virulence, impairment of the host immune response, and regulation of expression of virulence-related genes is shown here for the first time. Among those genes that encode well-established virulence factors are the genes of the phenazine cluster (phz), which is required for the synthesis of pyocyanin, a redox-active molecule; hcn, responsible for cyanide production; the catalase gene; and genes for the type VI secretion system (30, 35, 47, 48). Quorum sensing (QS)-regulated genes, such as lasB and rhlB, are also under the influence of AtvR and may account for the reduced virulence of the ΔatvR mutant as well, maybe due to an uncoordinated response of the QS cascade, as supported by the upregulation of the phz cluster as well. Curiously, QS-regulated genes are upregulated both in our AtvR-overexpressing strain and in an anr mutant (33), indicating opposite roles in this case and agreeing with the repression of atvR by Anr. Catalase, encoded by the katA gene, is an enzyme that reduces the oxygen peroxide that originates from the macrophage oxidative burst (30), and rahU codes for an extracellular enzyme that was shown to inhibit macrophage intracellular nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), being also part of the bacterial arsenal against host defenses (31).

Several genes involved in denitrification were induced in the AtvR-overexpressing strain. During acute and chronic infections, P. aeruginosa may find microaerobic conditions, and the presence of a complex regulatory system in response to low oxygen tension is not surprising. At least three main systems were shown to regulate anaerobic respiration in P. aeruginosa, namely, the NarXL, Anr, and Dnr systems (49, 50). NarXL and Anr directly regulate the nitrate reductase gene cluster and indirectly regulate other anaerobic respiration genes via the Dnr transcription factor. The importance of those systems in P. aeruginosa adaptability is reinforced by the reduced virulence of the anr, nar, and nir mutants, as anr, nar, and nir allow P. aeruginosa to survive under anoxic/hypoxic conditions when nitrate is present (49, 51, 52). Interestingly, the type III secretion system is not expressed in PA14 nirS mutants, but it is recovered by adding exogenous NO generators, suggesting that NO acts as a signaling molecule for cytotoxicity (53). During bacterial infections, the overall nitrate pool is increased (54); hence, it could be used as an electron acceptor to support bacterial alternative respiration. In fact, anaerobic respiration was already shown to be important in other pathogens, such as Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, in which the presence of periplasmic nitrate reductase is essential for virulence during colitis (55).

Therefore, AtvR contributes to P. aeruginosa virulence because it enables this bacterium to spread during infection, colonizing primary and secondary organs, leading to a severe acute infection which results in host death. AtvR is required for P. aeruginosa resistance against macrophage killing, as the deletion of AtvR resulted in higher levels of TNF-α production and higher levels of bacterial clearance in vitro. The ΔatvR strain was defective in the mouse model of acute pneumonia, being cleared more efficiently and allowing neutrophils to be recruited to the site of infection. These data suggest that AtvR plays an important role in P. aeruginosa adaptation against host defense by modulating the innate immune response.

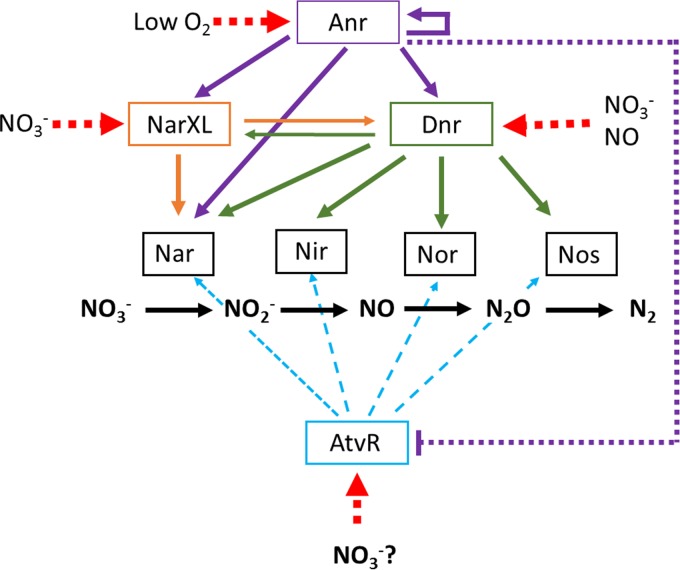

The roles of transcriptional regulators in fine-tuning adjustments in gene expression, leading to just-in-time gene expression, are very important for a highly adaptable bacterium to respond to a plethora of conditions that it encounters during the colonization of different niches. Survival in the absence of oxygen or in the presence of very low oxygen concentrations is crucial for P. aeruginosa to thrive during an infection, which is reflected by the numerous regulators involved in the metabolic switch to anaerobic respiration. To those already characterized activators, comprising Anr, NarL, and Dnr, we add the atypical RR AtvR (Fig. 8). We show here that AtvR does not fit into the already known denitrification regulatory cascade that has Anr as the master activator and Dnr and NarXL as downstream regulators. atvR mRNA levels are not under the regulation of Dnr and NarXL but are decreased by Anr (Fig. 7; see also Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). Although part of the AtvR regulon is superposed onto those regulators, it may respond to slightly different conditions by activating other virulence-relevant genes (Table 1). The AtvR function is not able to suppress the lack of Anr (Fig. 7 and S3), even though it can positively regulate the entire denitrification pathway.

FIG 8.

AtvR and the complex regulation of denitrification genes in P. aeruginosa. The structural genes for each electron transfer complex, nitrate (Nar), nitrite (Nir), nitric oxide (Nor), and nitrous oxide (Nos) reductases (gray boxes), are regulated by the Anr transcription activator, the TCS NarXL, the Dnr activator, and the newly discovered AtvR. Black arrows, electron transfer pathway; colored and solid arrows, positive transcriptional regulation; red dashed arrows, factors that affect the activity of the regulators are shown, in which the arrows point to the targets.

The challenge now is to understand how the expression and activity of AtvR are regulated, because the lack of an aspartate rules out regulation by phosphorylation. Would it be simply by modulating its transcription in the presence of nitrate, or are there more subtle mechanisms that regulate the stability of the message and/or the activity of the protein itself? How do all those regulators interact to warrant that the denitrification process is induced when needed? Those open questions need to be addressed to better understand one of the central metabolic pathways that contribute to Pseudomonas ubiquity and versatility.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, oligonucleotides, and culture conditions.

The strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. P. aeruginosa strains were grown at 37°C in LB broth supplemented with 250 μg/ml of kanamycin, 20 μg/ml nalidixic acid, or 50 μg/ml of gentamicin with or without 0.2% arabinose, when required. Escherichia coli strains were grown in LB medium supplemented with 100 μg/ml of ampicillin, 50 μg/ml of kanamycin, or 10 μg/ml of gentamicin, when required.

To construct the unmarked in-frame deletion of atvR (PA14_26570) or anr (PA14_44490), primers flanking the upstream and downstream regions of atvR or anr were designed (Table S2). atvR amplicons were cloned into pNPTS138 at the HindIII and EcoRI sites to generate pNPTS138ΔatvR. The anr, dnr, and narXL amplicons were cloned into pEX18Ap using sequence- and ligation-independent cloning (56) to generate pEX18Δanr, pEX18Δdnr, and pEX18ΔnarXL. The resulting constructs were used to introduce the atvR, anr, dnr, or narXL deletion into the wild-type strain PA14 genome or in the strain with the ΔatvR background by homologous recombination (57). Mutant clones were confirmed by PCR.

The atvR-overexpressing plasmid was constructed by amplifying the atvR coding region, cloning it into the pGEM-T vector, and digesting the resulting plasmid at the EcoRI and SpeI sites. This fragment was gel purified and cloned into pJN105 to generate pAtvR. The pAtvR and pJN105 plasmids were introduced into the wild-type strain and the ΔatvR, Δdnr, Δanr, and ΔnarXL mutants, generating the PA14/pJN105, PA14/pAtvR, ΔatvR/pJN105, ΔatvR/pAtvR, Δdnr/pJN105, Δdnr/pAtvR, Δanr/pJN105, Δanr/pAtvR, ΔnarXL/pJN105, and ΔnarXL/pAtvR strains.

Growth curves.

For growth curves, cultures were incubated overnight in LB or R-10 medium (RPMI 1640 supplemented with 2 mM glutamine, 10% fetal bovine serum [FBS], and 40 μg/ml gentamicin) and adjusted to an OD600 of 0.1 in LB or R-10 medium with or without gentamicin, and 1-ml samples were transferred to 24-well plates. The growth was monitored by determination of the OD600 at 15-min intervals with a SpectraMax Paradigm multimode microplate reader at 37°C with low orbital agitation. Alternatively, bacterial strains were grown to an OD600 of 2.0 in LB medium with or without gentamicin and arabinose. The bacteria were then diluted to 5 × 106 bacteria/ml in R-10 medium with (for the ΔatvR/pJN105 and ΔatvR/pAtvR strains) or without (for the PA14 and ΔatvR strains) 50 μg/ml of gentamicin and 0.2% arabinose. Then, 200 μl of the bacterial suspensions was added to a 96-well plate and the plate was incubated for 4 h 30 min at 37°C in 5% CO2, the same conditions used for the in vitro virulence assays. At the time points indicated above, each culture was serially diluted and plated and the numbers of CFU were determined.

RNA sequencing analysis.

PA14/pJN105 or PA14/pAtvR cultures were grown in LB medium with 0.2% arabinose and 50 μg/ml gentamicin at 37°C to an OD600 of 1.0. Two biological replicates were analyzed for each strain. Cells were harvested after addition of RNAprotect (Qiagen), total RNA was isolated using an RNeasy minikit (Qiagen), and RNA quality was assessed using a Bioanalyzer instrument. mRNA was enriched using a Ribo-Zero rRNA removal kit (for Gram-negative bacteria; Illumina), and rRNA depletion was confirmed by use of the Bioanalyzer instrument. Paired-end libraries were constructed using a TruSeq RNA library preparation kit (v2). The mean fragment size was determined by use of the Bioanalyzer instrument, and each library concentration was determined using a Kapa library quantification kit (Kapa Biosystems) according to the manufacturer's protocol. All samples were sequenced in an Illumina MiSeq system in the paired-end mode.

Gene expression quantification.

Sequence reads were separated according to their barcode, and barcode sequences were removed. For each sample, read quality was assessed using a FastQC sequencer, and the 3′ end was trimmed using a Fastx tool kit. After this step, the sequences were mapped to the P. aeruginosa PA14 reference strain genome and counted using the EDGE-pro program (58). The R package EDGE-R (59) was used for differential expression analysis. Genes were classified as differentially expressed if they presented a log2-fold change greater than 1 or less than −1 and if the Benjamini-Hochberg method-corrected P value (P-adj) was less than 0.05.

Hypoxia.

Experiments were performed under hypoxic conditions as described before with some modifications (60). Briefly, bacterial strains were grown aerobically in LB medium and diluted in 1 ml LB medium with or without 50 mM nitrate in a 1.5-ml microtube. The bacterial cultures were maintained for 24 h in a candle jar. After this incubation, the OD600 was determined and total RNA was extracted as described below.

qRT-PCR.

PA14/pJN105 or PA14/pAtvR was grown under the same conditions described above for the RNA-Seq experiments. For hypoxic conditions, samples were incubated in a candle jar and collected after 3 h (normoxia) or 24 h after inoculation (hypoxia). Alternatively, the strains with mutated anr, dnr, narXL, and/or atvR were grown to an OD600 of 2 in LB medium with 50 mM KNO3. Samples were incubated in a candle jar and collected after 4 h. All RNA samples were extracted with the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen), treated with DNase I (Thermo Scientific), and used for cDNA synthesis with RevertAid reverse transcriptase (Thermo Scientific) and random hexamer primers (Thermo Scientific). The cDNA was used as the template for quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) using Maxima SYBR green–carboxy-X-rhodamine quantitative PCR master mix (Thermo Scientific) and a StepOne Plus real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems). The primers used are listed in Table S2. Expression was normalized against that of nadB, and the relative expression from at least three biological replicates was calculated. Expression is given as the fold change with the standard deviation (SD) (61).

Cell culture.

The macrophage cell line J774 was maintained in R-10 medium at 37°C in 5% CO2. Cells were counted using a Neubauer chamber, and dead cells were excluded by trypan blue exclusion assay. Macrophages were seeded at 1 × 105 cells per well (96-well plates) or 5 × 105 cells per well (24-well plates) in R-10 medium without antibiotics or in R-10 medium with 50 μg/ml gentamicin and 0.2% arabinose. Macrophages were primed overnight with 10 ng/ml IFN-γ at 37°C in 5% CO2.

In vitro infection experiments.

All strains were grown in LB broth to an OD600 of 2.0. Bacteria were diluted in R-10 medium without antibiotics. For the phagocytosis and evasion assays, macrophages that had previously been seeded in 96-well plates with R-10 medium were pretreated or not pretreated with the NAPDH oxidase inhibitor diphenyleneiodonium (DPI) for 4 h. Bacteria were added at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10, and at 1 h postinfection, the supernatant was removed and fresh R-10 medium containing 200 μg/ml of gentamicin was added to the cell cultures to kill the remaining extracellular bacteria. After 30 min of incubation with gentamicin, cells were washed once with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and fresh medium was added. This point was defined as time zero. After the times indicated above, the supernatant was collected and serially diluted, the bacteria were plated, and the numbers of CFU, corresponding to the extracellular bacteria, were determined. To evaluate the amount of intracellular bacteria, macrophages were washed once and lysed with PBS with 0.1% Triton X-100; the lysates were serially diluted and plated, and the numbers of CFU were determined.

To quantify TNF-α, macrophages were seeded in 24-well plates and infected at an MOI of 10. At 3 h postinfection, the supernatants were removed, centrifuged, and stored at −20°C. Cytokine quantification was performed by ELISA (R&D Systems) by following the manufacturer's instructions. For the cytotoxicity assay, macrophages were seeded in a 96-well plate and infected as described above. Cytotoxicity was measured for samples taken at the times indicated above by quantifying the release of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) using a CytoTox 96 nonradioactive cytotoxicity assay according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Ethics statement.

All animal experiments were performed in agreement with the Ethical Principles in Animal Research adopted by the Brazilian Conselho Nacional de Controle da Experimentação Animal (CONCEA) and in accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Research Council (62). The animal protocol was approved by the Internal Animal Care and Use Committee of the Instituto de Química, Universidade de São Paulo (approval no. 17/2015).

Animals.

Female BALB/c mice (8 to 12 weeks old) were obtained from the in-house animal facility of the Biotério de Produção e Experimentação da Faculdade de Ciências Farmacêuticas e do Instituto de Química da Universidade de São Paulo. Mice were kept on a 12-h light/12-h dark cycle with free access to food and water and were maintained under specific-pathogen-free conditions. All mice were euthanized in a CO2 chamber, and every effort was made to minimize suffering.

Animal inoculation with bacteria.

The PA14 and ΔatvR strains were used for intratracheal (i.t.) inoculation as described before (29) with a few modifications. Bacteria were grown as described above, harvested by centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 2 min, washed twice in sterile PBS, and suspended in PBS at a concentration of 2 × 106 bacteria/60 μl. The number of CFU per milliliter was validated by plating serial dilutions of the suspensions. Each mouse received 60 μl of a bacterial suspension. A ketamine-xylazine mixture was injected intraperitoneally to anesthetize the mice before surgery. A midventral incision was made, and the trachea was exposed. The bacterial suspension was inoculated i.t. Controls were inoculated i.t. with 60 μl sterile PBS.

In vivo CFU determination.

At 24 h after infection, the lungs, spleen, and liver were harvested for determination of the numbers of CFU and cytokine measurements. The tissues were homogenized in 1 ml PBS for the lung and spleen and in 2 ml PBS for the liver. The supernatants were collected, and the numbers of CFU were determined by serial dilution and plating on LB plates. For cytokine measurements, the lungs were homogenized, and the supernatants were centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The cytokines TNF-α, IFN-γ, and IL-10 were quantified by ELISA (R&D Systems) by following the manufacturer's instructions.

Flow cytometry.

At 24 h after infection, the lungs were harvested, minced, and digested with collagenase for 30 min at 37°C. Red blood cells (RBC) were lysed by adding NH4Cl lysis buffer. Cells were resuspended in PBS with 3% FBS and stained with different combinations of conjugated antibodies, including F4/80-phycoerythrin (PE)-Cy5 (BM8), CD11c-fluorescein isothiocyanate (HL3), CD11b-PE (M1/70), and Ly6G/Ly6C-allophycocyanin (RB6-8C5), followed by incubation for 20 min on ice. Finally, the cells were washed and resuspended for flow cytometry analysis. FlowJo software (Tree Star) was used to analyze the data.

Myeloperoxidase activity assay.

The myeloperoxidase activity assay was performed as previously described with a few modifications (63, 64). Animals were infected as described above, and the lungs were harvested, mechanically lysed in the presence of 50 mM sodium phosphate, pH 5.4, 5 mM EDTA, and 0.5% cetyltrimethylammonium bromide, sonicated, and centrifuged. The supernatant (50 μl) was mixed with an equal volume of 3 mM 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine dihydrochloride (TMB) for 2 min. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 25 μl of 2 M H2SO4. The optical density (OD) at 450 nm was measured.

Survival.

After i.t. infection with wild-type PA14 or the ΔatvR mutant (n = 16 per group), animals were observed for survival. All deaths reported were from moribund/euthanized mice. Mice with labored or rapid breathing, decreased motility, ruffled or abnormal-looking fur, or other obvious signs of distress were considered moribund, as described before (65).

Statistical analyses.

Prism (v5) software (GraphPad Inc.) was used for all statistical analyses, except for statistical analysis of the data from RNA-Seq analysis. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were plotted, and significance was calculated using the log rank test. Data were compared using a t test and one-way or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni's multiple-comparison test.

Data availability.

The raw RNA-Seq data were deposited at BioProject (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject) under accession number PRJNA375803.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank L. F. Silva for assistance with RNA-Seq analysis and D. Schechtman for carefully reading the manuscript.

G.H.K., R.L.B., and S.R.D.A. conceived and designed the experiments. G.H.K., L.C.D.B., J.R.F.D.A., and T.D.O.P. performed the virulence experiments. G.H.K., G.G.N., and A.L.B. performed the RNA-Seq experiment and analysis. R.L.B. and S.R.D.A. wrote the paper. G.H.K., G.G.N., T.D.O.P., R.L.B., and S.R.D.A. contributed reagents, materials, and analysis tools.

Gilberto Hideo Kaihami was supported by FAPESP grant no. 2013/10385-7, and Regina Lúcia Baldini was partially supported by CNPq grant no. 307218/2014-7. Work in R. L. Baldini's lab is supported by FAPESP grant no. 2014/05082-8.

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/IAI.00207-17.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bourret RB. 2006. Census of prokaryotic senses. J Bacteriol 188:4165–4168. doi: 10.1128/JB.00311-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Galperin MY. 2006. Structural classification of bacterial response regulators: diversity of output domains and domain combinations. J Bacteriol 188:4169–4182. doi: 10.1128/JB.01887-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gao R, Mack TR, Stock AM. 2007. Bacterial response regulators: versatile regulatory strategies from common domains. Trends Biochem Sci 32:225–234. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stock AM, Robinson VL, Goudreau PN. 2000. Two-component signal transduction. Annu Rev Biochem 69:183–215. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bourret RB. 2010. Receiver domain structure and function in response regulator proteins. Curr Opin Microbiol 13:142–149. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2010.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maule AF, Wright DDP, Weiner JJ, Han L, Peterson FC, Volkman BFB, Silvaggi NR, Ulijasz AAT. 2015. The aspartate-less receiver (ALR) domains: distribution, structure and function. PLoS Pathog 11:e1004795. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mahajan-Miklos S, Tan M-W, Rahme LG, Ausubel FM. 1999. Molecular mechanisms of bacterial virulence elucidated using a Pseudomonas aeruginosa–Caenorhabditis elegans pathogenesis model. Cell 96:47–56. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80958-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lyczak JB, Cannon CL, Pier GB. 2000. Establishment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection: lessons from a versatile opportunist. Microbes Infect 2:1051–1060. doi: 10.1016/S1286-4579(00)01259-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wagner VE, Iglewski BH. 2008. P. aeruginosa biofilms in CF infection. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 35:124–134. doi: 10.1007/s12016-008-8079-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crouch Brewer S, Wunderink RG, Jones CB, Leeper KV. 1996. Ventilator-associated pneumonia due to Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Chest 109:1019–1029. doi: 10.1378/chest.109.4.1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weinstein RA, Gaynes R, Edwards JR, National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance System. 2005. Overview of nosocomial infections caused by gram-negative bacilli. Clin Infect Dis 41:848–854. doi: 10.1086/432803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williams BJ, Dehnbostel J, Blackwell TS. 2010. Pseudomonas aeruginosa: host defence in lung diseases. Respirology 15:1037–1056. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2010.01819.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kawai T, Akira S. 2010. The role of pattern-recognition receptors in innate immunity: update on Toll-like receptors. Nat Immunol 11:373–384. doi: 10.1038/ni.1863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leeper-Woodford SK, Carey PD, Byrne K, Fisher BJ, Blocher C, Sugerman HJ, Fowler AA. 1991. Ibuprofen attenuates plasma tumor necrosis factor activity during sepsis-induced acute lung injury. J Appl Physiol 71:915–923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ulich TR, Watson LR, Yin SM, Guo KZ, Wang P, Thang H, del Castillo J. 1991. The intratracheal administration of endotoxin and cytokines. Am J Pathol 138:1485–1496. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kisala JM, Ayala A, Stephan RN, Chaudry IH. 1993. A model of pulmonary atelectasis in rats: activation of alveolar macrophage and cytokine release. Am J Physiol 264:R610–R614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Trunk K, Benkert B, Quäck N, Münch R, Scheer M, Garbe J, Jänsch L, Trost M, Wehland J, Buer J, Jahn M, Schobert M, Jahn D. 2010. Anaerobic adaptation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: definition of the Anr and Dnr regulons. Environ Microbiol 12:1719–1733. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02252.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arai H. 2011. Regulation and function of versatile aerobic and anaerobic respiratory metabolism in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Front Microbiol 2:103. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schreiber K, Krieger R, Benkert B, Eschbach M, Arai H, Schobert M, Jahn D. 2007. The anaerobic regulatory network required for Pseudomonas aeruginosa nitrate respiration. J Bacteriol 189:4310–4314. doi: 10.1128/JB.00240-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dietrich LEP, Okegbe C, Price-Whelan A, Sakhtah H, Hunter RC, Newman DK. 2013. Bacterial community morphogenesis is intimately linked to the intracellular redox state. J Bacteriol 195:1371–1380. doi: 10.1128/JB.02273-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rodrigue A, Quentin Y, Lazdunski A, Méjean V, Foglino M. 2000. Two-component systems in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: why so many? Trends Microbiol 8:498–504. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(00)01833-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen Y-T, Chang HY, Lu CL, Peng H-L. 2004. Evolutionary analysis of the two-component systems in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. J Mol Evol 59:725–737. doi: 10.1007/s00239-004-2663-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gooderham WJ, Hancock REW. 2009. Regulation of virulence and antibiotic resistance by two-component regulatory systems in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. FEMS Microbiol Rev 33:279–294. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2008.00135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goodman AL, Merighi M, Hyodo M, Ventre I, Filloux A, Lory S. 2009. Direct interaction between sensor kinase proteins mediates acute and chronic disease phenotypes in a bacterial pathogen. Genes Dev 23:249–259. doi: 10.1101/gad.1739009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Petrova OE, Cherny KE, Sauer K. 2014. The Pseudomonas aeruginosa diguanylate cyclase GcbA, a homolog of P. fluorescens GcbA, promotes initial attachment to surfaces, but not biofilm formation, via regulation of motility. J Bacteriol 196:2827–2841. doi: 10.1128/JB.01628-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klose KE, Weiss DS, Kustu S. 1993. Glutamate at the site of phosphorylation of nitrogen-regulatory protein NTRC mimics aspartyl-phosphate and activates the protein. J Mol Biol 232:67–78. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gao R, Mukhopadhyay A, Fang F, Lynn DG. 2006. Constitutive activation of two-component response regulators: characterization of VirG activation in Agrobacterium tumefaciens. J Bacteriol 188:5204–5211. doi: 10.1128/JB.00387-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arribas-Bosacoma R, Kim S-K, Ferrer-Orta C, Blanco AG, Pereira PJB, Gomis-Rüth FX, Wanner BL, Coll M, Solà M. 2007. The X-ray crystal structures of two constitutively active mutants of the Escherichia coli PhoB receiver domain give insights into activation. J Mol Biol 366:626–641. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.11.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaihami GH, de Almeida JRF, dos Santos SS, Netto LES, de Almeida SR, Baldini RL. 2014. Involvement of a 1-Cys peroxiredoxin in bacterial virulence. PLoS Pathog 10:e1004442. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee J-S, Heo Y-J, Lee JK, Cho Y-H. 2005. KatA, the major catalase, is critical for osmoprotection and virulence in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA14. Infect Immun 73:4399–4403. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.7.4399-4403.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rao J, Elliott MR, Leitinger N, Jensen RV, Goldberg JB, Amin AR. 2011. RahU: an inducible and functionally pleiotropic protein in Pseudomonas aeruginosa modulates innate immunity and inflammation in host cells. Cell Immunol 270:103–113. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2011.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ramphal R, Balloy V, Jyot J, Verma A, Si-Tahar M, Chignard M. 2008. Control of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in the lung requires the recognition of either lipopolysaccharide or flagellin. J Immunol 181:586–592. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.1.586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hammond JH, Dolben EF, Smith TJ, Bhuju S, Hogan DA. 2015. Links between Anr and quorum sensing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. J Bacteriol 197:2810–2820. doi: 10.1128/JB.00182-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wretlind B, Pavlovskis OR. Pseudomonas aeruginosa elastase and its role in Pseudomonas infections. Rev Infect Dis 5(Suppl 5):S998–S1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gallagher LA, Manoil C. 2001. Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 kills Caenorhabditis elegans by cyanide poisoning. J Bacteriol 183:6207–6214. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.21.6207-6214.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alcorn JF, Wright JR. 2004. Degradation of pulmonary surfactant protein D by Pseudomonas aeruginosa elastase abrogates innate immune function. J Biol Chem 279:30871–30879. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400796200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Filiatrault MJ, Picardo KF, Ngai H, Passador L, Iglewski BH. 2006. Identification of Pseudomonas aeruginosa genes involved in virulence and anaerobic growth. Infect Immun 74:4237–4245. doi: 10.1128/IAI.02014-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Donczew R, Makowski Ł Jaworski P, Bezulska M, Nowaczyk M, Zakrzewska-Czerwińska J, Zawilak-Pawlik A. 2015. The atypical response regulator HP1021 controls formation of the Helicobacter pylori replication initiation complex. Mol Microbiol 95:297–312. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pflock M, Bathon M, Schar J, Muller S, Mollenkopf H, Meyer TF, Beier D. 2007. The orphan response regulator HP1021 of Helicobacter pylori regulates transcription of a gene cluster presumably involved in acetone metabolism. J Bacteriol 189:2339–2349. doi: 10.1128/JB.01827-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ruiz D, Salinas P, Lopez-Redondo ML, Cayuela ML, Marina A, Contreras A. 2008. Phosphorylation-independent activation of the atypical response regulator NblR. Microbiology 154:3002–3015. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2008/020677-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McDaniel TK, DeWalt KC, Salama NR, Falkow S. 2001. New approaches for validation of lethal phenotypes and genetic reversion in Helicobacter pylori. Helicobacter 6:15–23. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5378.2001.00001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Al-Bassam MM, Bibb MJ, Bush MJ, Chandra G, Buttner MJ. 2014. Response regulator heterodimer formation controls a key stage in Streptomyces development. PLoS Genet 10:e1004554. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Salinas P, Ruiz D, Cantos R, Lopez-Redondo ML, Marina A, Contreras A. 2007. The regulatory factor SipA provides a link between NblS and NblR signal transduction pathways in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. PCC 7942. Mol Microbiol 66:1607–1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Barta ML, Hickey JM, Anbanandam A, Dyer K, Hammel M, Hefty PS. 2014. Atypical response regulator ChxR from Chlamydia trachomatis is structurally poised for DNA binding. PLoS One 9:e91760. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0091760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hickey JM, Weldon L, Hefty PS. 2011. The atypical OmpR/PhoB response regulator ChxR from Chlamydia trachomatis forms homodimers in vivo and binds a direct repeat of nucleotide sequences. J Bacteriol 193:389–398. doi: 10.1128/JB.00833-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Koo IC, Walthers D, Hefty PS, Kenney LJ, Stephens RS. 2006. ChxR is a transcriptional activator in Chlamydia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103:750–755. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509690103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lesic B, Starkey M, He J, Hazan R, Rahme LG. 2009. Quorum sensing differentially regulates Pseudomonas aeruginosa type VI secretion locus I and homologous loci II and III, which are required for pathogenesis. Microbiology 155:2845–2855. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.029082-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lau GW, Ran H, Kong F, Hassett DJ, Mavrodi D. 2004. Pseudomonas aeruginosa pyocyanin is critical for lung infection in mice. Infect Immun 72:4275–4278. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.7.4275-4278.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Van Alst NE, Sherrill LA, Iglewski BH, Haidaris CG. 2009. Compensatory periplasmic nitrate reductase activity supports anaerobic growth of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 in the absence of membrane nitrate reductase. Can J Microbiol 55:1133–1144. doi: 10.1139/W09-065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Noriega CE, Lin H-Y, Chen L-L, Williams SB, Stewart V. 2010. Asymmetric cross-regulation between the nitrate-responsive NarX-NarL and NarQ-NarP two-component regulatory systems from Escherichia coli K-12. Mol Microbiol 75:394–412. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06987.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Van Alst NE, Picardo KF, Iglewski BH, Haidaris CG. 2007. Nitrate sensing and metabolism modulate motility, biofilm formation, and virulence in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infect Immun 75:3780–3790. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00201-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jackson AA, Gross MJ, Daniels EF, Hampton TH, Hammond JH, Vallet-Gely I, Dove SL, Stanton BA, Hogan DA. 2013. Anr and its activation by PlcH activity in Pseudomonas aeruginosa host colonization and virulence. J Bacteriol 195:3093–3104. doi: 10.1128/JB.02169-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Van Alst NE, Wellington M, Clark VL, Haidaris CG, Iglewski BH. 2009. Nitrite reductase NirS is required for type III secretion system expression and virulence in the human monocyte cell line THP-1 by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infect Immun 77:4446–4454. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00822-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Linnane SJ, Keatings VM, Costello CM, Moynihan JB, O'Connor CM, Fitzgerald MX, McLoughlin P. 1998. Total sputum nitrate plus nitrite is raised during acute pulmonary infection in cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 158:207–212. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.158.1.9707096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lopez CA, Rivera-Chávez F, Byndloss MX, Bäumler AJ. 2015. The periplasmic nitrate reductase NapABC supports luminal growth of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium during colitis. Infect Immun 83:3470–3478. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00351-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jeong J-Y, Yim H-S, Ryu J-Y, Lee HS, Lee J-H, Seen D-S, Kang SG. 2012. One-step sequence- and ligation-independent cloning as a rapid and versatile cloning method for functional genomics studies. Appl Environ Microbiol 78:5440–5443. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00844-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Simon R, Priefer U, Pühler A. 1983. A broad host range mobilization system for in vivo genetic engineering: transposon mutagenesis in gram negative bacteria. Biotechnology (NY) 1:784–791. doi: 10.1038/nbt1183-784. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Magoc T, Wood D, Salzberg SL. 2013. EDGE-pro: estimated degree of gene expression in prokaryotic genomes. Evol Bioinform Online 9:127–136. doi: 10.4137/EBO.S11250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK. 2010. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 26:139–140. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cooper M, Tavankar GR, Williams HD. 2003. Regulation of expression of the cyanide-insensitive terminal oxidase in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiology 149:1275–1284. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26017-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.National Research Council. 2011. Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals, 8th ed National Academies Press, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Véliz Rodriguez TV, Moalli F, Polentarutti N, Paroni M, Bonavita E, Anselmo A, Nebuloni M, Mantero S, Jaillon S, Bragonzi A, Mantovani A, Riva F, Garlanda C. 2012. Role of Toll interleukin-1 receptor (IL-1R) 8, a negative regulator of IL-1R/Toll-like receptor signaling, in resistance to acute Pseudomonas aeruginosa lung infection. Infect Immun 80:100–109. doi: 10.1128/IAI.05695-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pulli B, Ali M, Forghani R, Schob S, Hsieh KLC, Wojtkiewicz G, Linnoila JJ, Chen JW. 2013. Measuring myeloperoxidase activity in biological samples. PLoS One 8:e67976. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Koh AY, Priebe GP, Ray C, Rooijen Van N, Pier GB. 2009. Inescapable need for neutrophils as mediators of cellular innate immunity to acute Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia. Infect Immun 77:5300–5310. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00501-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The raw RNA-Seq data were deposited at BioProject (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject) under accession number PRJNA375803.