Abstract

IMPORTANCE

Guidelines assert that CPM should be discouraged in patients without an elevated risk of a second primary breast cancer. However, little is known about the impact of surgeons discouraging CPM on patient care satisfaction or decisions to seek treatment from another clinician.

OBJECTIVE

We examined the association between patient report of first surgeon recommendation against CPM and the extent of discussion about it with 3 outcomes: patient satisfaction with surgery decisions, receipt of a second opinion, and receipt of surgery by a second surgeon.

DESIGN, SETTING, and PARTICIPANTS

This population-based survey study was conducted in Georgia and California. We identified 3880 women with stages 0 to II breast cancer treated in 2013–2014 through the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results registries of Georgia and Los Angeles County. Surveys were sent approximately 2 months after surgery (71% response rate; n=2578). In this analysis conducted from February to May 2016, we included patients with unilateral breast cancer who considered CPM (n=1,140). Patients were selected between July 2013 and September 2014.

PRIMARY OUTCOME AND MEASURES

We examined report of surgeon recommendations, level of discussion about CPM, satisfaction with surgical decision-making, receipt of second surgical opinion, and surgery from a second surgeon.

RESULTS

The mean (SD) age of patients in this study was 56 (10.6) years. About one-quarter of patients (26.7%; n=304) reported that their first surgeon recommended against CPM and 30.1% (n=343) reported no substantial discussion about CPM. Dissatisfaction with surgery decision was uncommon (7.6%; n=130), controlling for clinical and demographic characteristics. One-fifth of patients (20.6%; n=304) had a second opinion about surgical options and 9.8% (n=158) had surgery performed by a second surgeon. Dissatisfaction was very low (3.9%; n=42) among patients who reported that their surgeon did not recommend against CPM but discussed it. Dissatisfaction was substantively higher for those whose surgeon recommended against CPM with no substantive discussion (14.5%; n=37). Women who received a recommendation against CPM were not more likely to seek a second opinion (17.1% among patients with recommendation against CPM vs 15.1% of others, p=.52) nor to receive surgery by a second surgeon (7.9% among patients with recommendation against CPM vs 8.3% of others, p=.883).

CONCLUSION AND RELEVANCE

Most patients are satisfied with surgical decision making. First-surgeon recommendation against CPM does not appear to substantively increase patient dissatisfaction, use of second opinions, or loss of the patient to a second surgeon.

INTRODUCTION

Rates of contralateral prophylactic mastectomy (CPM) in the United States in women with unilateral breast cancer have increased dramatically, largely because of patient desires for the procedure.1 More patients consider CPM today because of greater awareness of the treatment option and psychological factors that motivate their preferences for the most extensive surgical treatment.2 Current clinical guidelines suggest that CPM should be discouraged in patients who do not have elevated risk of a second primary breast cancer based on family history and results of genetic testing.3,4 However, most women who undergo CPM after a diagnosis of breast cancer have an average risk of developing a second breast primary and rates of contralateral breast cancer have been decreasing steadily due to the increased use of adjuvant systemic therapy for early stage disease.5,6 The complex interaction between patient desires for the most extensive treatment and the surgeon’s role in minimizing surgical morbidity is poorly understood. In particular, little is known regarding the impact of a surgeon discouraging CPM and patient satisfaction with care or the decision to seek treatment with another provider. In order to address this knowledge gap we examined patient reactions to recommendations regarding surgery options made by their first surgical consultant following a diagnosis of breast cancer by considering three outcomes: patient satisfaction with the surgery decision, receipt of a second surgical opinion, and whether a second surgeon performed the definitive surgery. We also examined the extent to which CPM was discussed and its association with patient appraisal of surgery decision-making. We hypothesized that patient report of a first surgeon recommendation against CPM may result in less satisfied patients, more second opinions, and greater likelihood of receipt of surgery from a second surgeon.

METHODS

Study Sample and Data Collection

After Institutional Review Board approval, we selected women aged 20 to 79 years and diagnosed with stages 0 to II breast cancer who were reported to the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) registries of Georgia and Los Angeles County. We received a waiver of written informed consent, as participation in the survey study (after receiving detailed information about the study, benefits and risks, and their rights as a participant) was considered adequate informed consent. Eligible patients were identified via initial surgical pathology reports from a list of “definitive” procedures (performed with intent of removing the entire tumor with clear margins). Patients were selected approximately 2 months after surgery and surveys were mailed on a monthly basis shortly after (diagnosis-survey completion average 6.0 months, sd 2.8 months). To select subjects with early-stage breast cancer, patients with stage III or IV disease, tumors greater than 5 cm, or 3 or more involved lymph nodes were excluded. Black, Asian, and Hispanic women were oversampled in Los Angeles using an approach we previously described.7 Patients were selected between July 2013 and September 2014. To encourage response, we provided a $20 cash incentive and used a modified Dillman method for patient recruitment,8 including reminders to non-respondents. All materials were sent in English. We also included Spanish-translated materials to all women with surnames suggesting Hispanic ethnicity.7 Responses to the survey were merged with clinical data from SEER.

We selected 3,880 women diagnosed with early-stage breast cancer in 2013–2014 based on rapid reporting systems from the SEER registries; among them, 249 were later deemed ineligible due to having a prior breast cancer diagnosis or stage III–IV disease; residing outside the SEER registry area; or being deceased, too ill/incompetent or unable to complete a survey in Spanish or English. Of 3,631 eligible women remaining, 1,053 did not return a survey or refused to participate. Of 2,578 patients who responded (71.0%), 110 patients with bilateral disease were excluded. Additionally, we excluded 1,328 patients who reported no consideration of CPM, leaving 1,140 (mean [SD] age, 56 [10.6] years; 46.2% of those with unilateral disease) for the analytic sample (Supplemental Figure 1).

Questionnaire design and content

Questionnaire content was developed based on a conceptual framework,9–12 research questions, and hypotheses. We developed measures drawing from the literature and our prior research. We utilized standard techniques to assess content validity, including systematic review by design experts, cognitive pretesting with patients, and pilot studies in selected internet and clinic populations.

Measures

There were 3 primary dependent variables in this study Dissatisfaction with the surgery decision was constructed from the Patient Satisfaction with the Surgery Decision Scale, validated in prior studies13,14 (continuous measure range from 1.0 to 5.0 calculated by averaging a 5-item scale; Likert response categories 1 to 5 from not at all to very satisfied). This was created as a binary outcome (satisfied/dissatisfied) as this had more clinically meaningful interpretation. A cutoff below 3 indicated dissatisfaction. We performed sensitivity analyses evaluating a continuous variable and varying the cutoff for the binary specification. The 2 other dependent variables were whether the patient reported receiving a second opinion about the surgery decision (yes/no) and whether they had their breast cancer surgery by a second surgeon (yes/no).

There were 2 primary independent variables. Patient report of first surgeon recommendation about CPM was ascertained by asking patients “How strongly did the first surgeon you consulted recommend having a mastectomy on both breasts?” The five response categories were strongly/weakly recommended for CPM, left up to the patient, or strongly/weakly recommended against CPM. We created a binary variable a priori that indicated that the surgeon recommended against CPM vs recommended for CPM or it was left up to the patient. A level of discussion about CPM during treatment deliberation was measured using a 5 item assessment of whether surgeons discussed the specific benefits and risks of CPM with regard to: 1) survival, 2) recurrence of treated cancer, 3) occurrence of new contralateral cancer, 4) cosmetic outcomes, and 5) recovery from surgery. This was also categorized as a binary outcome for clinical interpretability. We considered that CPM was not substantively discussed if patients reported that it was not discussed for any of the 5 items. Sensitivity analyses specified a priori were performed using an ordinal approach (no tradeoffs discussed, 3 discussed, all discussed). Additional covariates included age, marital status, education, insurance, race/ethnicity, and an indicator of elevated risk of second primary breast cancer vs average risk (based on a detailed assessment of family cancer history and genetic testing results) all derived from the patient survey. We also included geographic site and stage derived from SEER clinical information.

Analysis

First, we examined the characteristics of the total population followed by the distribution of key outcomes and covariates for women who reported any consideration of CPM. We then conducted logistic regression to examine the association between the binary variable first surgeon recommended against CPM and sociodemographic factors (marital status, age, education, race/ethnicity, paid work at time of diagnosis), risk for second primary and geographic site. Finally, we calculated adjusted proportions of the 3 outcome variables by surgeon recommendation and the CPM discussion variable by creating separate logistic regression models for each of the outcomes and generating the marginal probabilities, averaging across the independent variables. All statistical analyses incorporate weights to account for differential probabilities of sample selection, survey non-response and to assure that the distributions of our sample resemble those of the target population.15

Multiple imputations of missing data16 were used in all multivariable models to reduce potential for bias due to missing data, and improve efficiency by taking full advantage of our data. Estimates and their variances from the multiple imputation results were combined according to the Rubin method.17 Sensitivity analyses included re-specifying the binary decision dissatisfaction variable as a continuous variable, testing different cutoffs, and limiting models to non-missing data.

RESULTS

Table 1 shows characteristics and outcomes for the study sample. More than half of the patients (56.1%) were younger than age 60 years, 25.3% completed high school or less, 44.1% were nonwhite. More than half (57.5%) of the study sample considered CPM strongly or very strongly (vs weakly or moderately). Ultimately, 40.5% got breast conserving therapy, 22.0% unilateral mastectomy (41.4% of whom got breast reconstruction), and 38.2% CPM (76.7% of whom underwent breast reconstruction).

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics

| Characteristics | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Surgeon Recommendation | ||

| Not Against CPM | 767 | 67.3% |

| Against CPM | 304 | 26.7% |

| Missing | 69 | 6.0% |

| Discussion of CPM | ||

| Discussed | 720 | 63.1% |

| Not Discussed | 343 | 30.1% |

| Missing | 77 | 6.8% |

| Age, grouped | ||

| Less than 50 | 264 | 23.1% |

| 50–59 | 374 | 32.8% |

| 60–69 | 326 | 28.6% |

| 70 or Older | 174 | 15.3% |

| Missing | 2 | 0.2% |

| Education | ||

| High School or less | 288 | 25.3% |

| Some College/Technical School | 360 | 31.6% |

| College Graduate | 477 | 41.8% |

| Missing | 15 | 1.3% |

| Insurance | ||

| Private | 700 | 61.4% |

| Medicaid | 152 | 13.3% |

| Medicare | 239 | 21.0% |

| None | 8 | 0.7% |

| Missing | 41 | 3.6% |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| White | 613 | 53.7% |

| Black | 182 | 16.0% |

| Hispanic | 210 | 18.4% |

| Asian | 92 | 8.1% |

| Missing | 43 | 3.8% |

| Marital Status | ||

| Not Married | 396 | 34.7% |

| Married/Partner | 728 | 63.9% |

| Missing | 16 | 1.4% |

| Employment Status Before Diagnosis | ||

| Not Working For Pay | 255 | 22.4% |

| Working For Pay | 748 | 65.6% |

| Missing | 137 | 12.0% |

| Risk of Recurrence | ||

| Not High Risk | 455 | 39.9% |

| High Risk | 685 | 60.1% |

| Stage | ||

| 0 | 184 | 16.1% |

| I | 630 | 55.3% |

| II | 326 | 28.6% |

| Consideration of CPM | ||

| Weak/Moderate | 462 | 40.5% |

| Strong/Very Strong | 625 | 54.9% |

| Missing | 53 | 4.6% |

| Site | ||

| Georgia | 642 | 56.3% |

| LA | 498 | 43.7% |

| Ultimate Treatment | ||

| Breast Conserving Surgery | 447 | 39.2% |

| Unilateral Mastectomy | 251 | 22.0% |

| Bilateral Mastectomy | 435 | 38.2% |

| Missing | 7 | 0.6% |

About one-quarter (26.7%) of the total study sample patients reported that their first surgeon recommended against CPM and 32.3% reported no substantial discussion about CPM. Dissatisfaction with the surgery decision was uncommon (7.6%). One-fifth of patients (20.6%) had a second opinion about surgical options and 9.8% had surgery performed by a second surgeon. Dissatisfaction with the surgery decision was higher for women who reported that their surgeon recommended against CPM (12.8% vs 6.5%; p<.01) or for whom CPM was not discussed (13.5% vs 6.0%; p<.01). Dissatisfaction was also higher among women who were nonwhite race, at higher risk of developing a second primary cancer, had a higher stage cancer, or who resided in Los Angeles County. Second opinions were more common among patients who were younger, more educated, did not have Medicare, and who worked for pay. Receipt of surgery by a second surgeon was more common among patients who worked for pay or who resided in Los Angeles County.

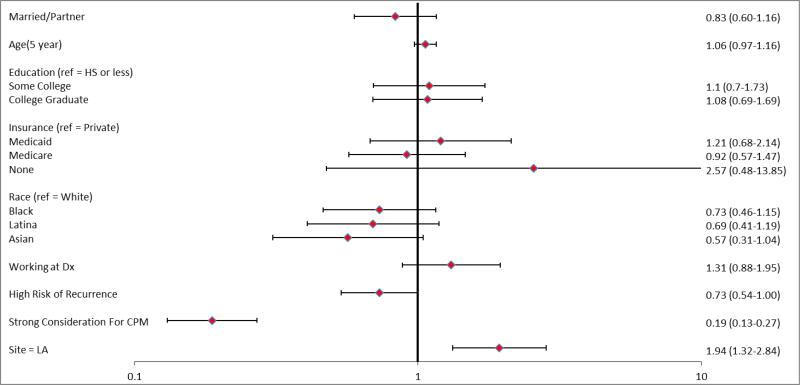

First-surgeon recommendation against CPM was highly associated with low rates of receipt of CPM (6.1% vs 57.5% of those with no recommendation against CPM; p<.01). Figure 1 shows correlates of recommendations against CPM. Recommendation against CPM was only associated with geographic site: surgeons in Los Angeles county were more likely to recommend against CPM. There was no significant association with marital status, age, education, insurance, race/ethnicity, working for pay at time of diagnosis, or risk of recurrence.

Figure 1. Correlates of surgeon recommendation against contralateral prophylactic mastectomy.

Odds ratios (95% confidence intervals) from a logistic regression model using multiple imputation for missing data and weights for differing probabilities of sample selection and non-response. Ref indicates reference group; Dx indicates diagnosis; LA indicates Los Angeles County.

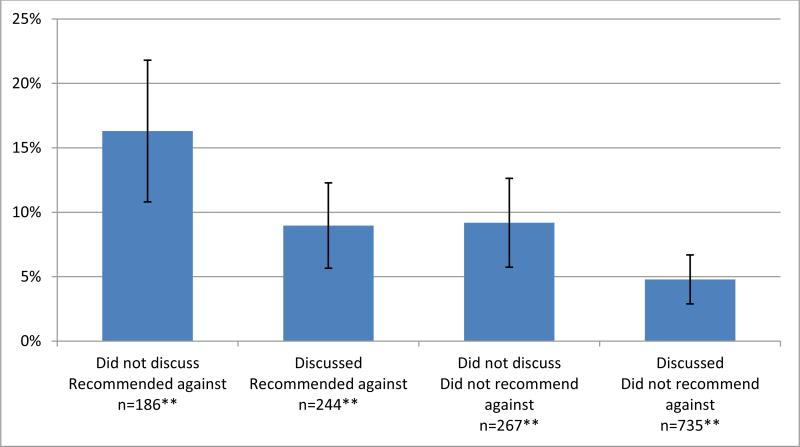

Figure 2 shows the adjusted proportion of patients dissatisfied with the surgery decision by surgeon recommendation and extent of discussion about CPM controlling for other factors. Dissatisfaction was very low (3.9%) among patients who reported that their surgeon did not recommend against CPM but discussed it. Dissatisfaction with the surgery decision was somewhat higher for women whose surgeon did not recommend against CPM but did not substantively discuss it (7.7%; n=267) or recommended against with discussion (7.6%; n=244). Dissatisfaction was highest for those whose surgeon recommended against CPM with no substantive discussion (14.5%; n=188), but this group represented only about 13% of patients in the sample. Dissatisfaction differed significantly across the four groups (p<.01).

Figure 2. Dissatisfaction with surgical decision by surgeon recommendation and extent of discussion about contralateral prophylactic mastectomy.

*Predicted probabilities of surgical decision dissatisfaction. Rates are marginal predictions derived from a multivariable logistic model, averaging over marital status, education, insurance, race, employment, stage, risk of recurrence, site, and consideration for CPM.

**Weighted to account for oversampled groups in the design and non-response

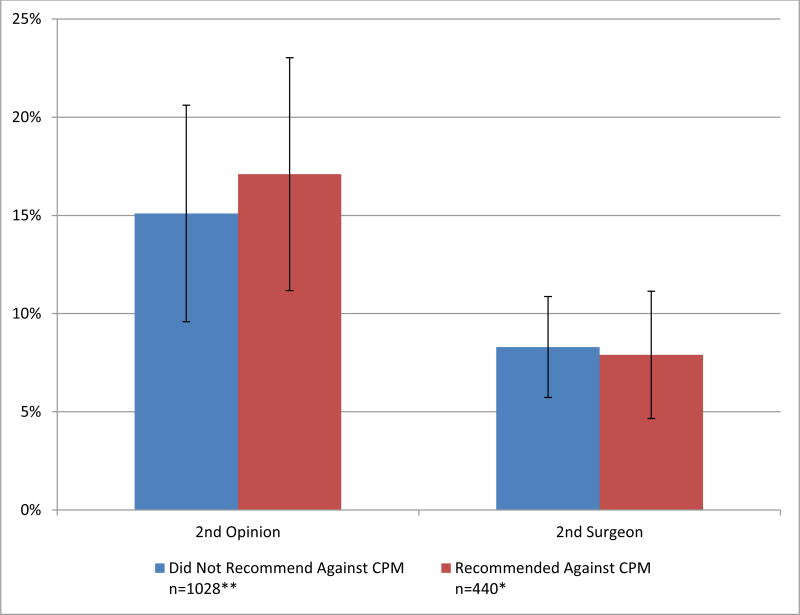

Figure 3 shows the proportion of patients who sought a second opinion or received surgery by a second surgeon by first surgeon CPM recommendation categories adjusted for other factors Women who received a recommendation against CPM were not more likely to seek a second opinion (17.1% among patients with recommendation against CPM vs 15.0% of others p=.52) nor to receive surgery by a second surgeon (7.9% among both patients with recommendation against CPM and of others, p=.88).

Figure 3. Receipt of second opinion or surgery by second surgeon by surgeon recommendation.

* Predicted probabilities of second opinion and surgery by second surgeon. Rates are marginal predictions derived from a multivariable logistic model, averaging over marital status, education, insurance, race, employment, stage, risk of recurrence, site, and consideration for CPM.

**Weighted to account for oversampled groups in the design and non-response

Hosmer-Lemeshow tests did not indicate significant lack of fit; the Chi Square statistics from these tests ranged from 3.4 to 9.9 across models and imputations (p= .27 – .90). Alternative specifications of the decision satisfaction measure looking at different cutoffs or treating it as a continuous variable showed no significant differences in model results. No significant interactions were found between any of the independent variables.

DISCUSSION

In this large diverse population-based sample of patients newly diagnosed with breast cancer about half with unilateral disease considered contralateral prophylactic mastectomy. Among these patients, about one-quarter reported that their first surgeon recommended against CPM and one-third reported that CPM was not substantively discussed with their surgeon(s). There were no significant differences in the likelihood of CPM recommendation by sociodemographic factors except for geographic location. Geographic variation in surgeon recommendation may suggest differences in practice network factors with regard to how surgeons approach communication about CPM. Both surgeon recommendation against CPM and lack of a substantive discussion were associated with patient dissatisfaction with the surgery decision. The additive effect was modest: nearly 15% of patients were dissatisfied with the surgery decision process when a first surgeon recommended against CPM but there was no substantive discussion about it (vs 4.0% in patients who did not receive a recommendation against CPM but had a discussion about it). However, only about 15% of patients reported this circumstance. Second opinions about surgery were not common (15.7%) and surgery performed by a second surgeon even less so (8.1%). First-surgeon recommendation against CPM was not associated with the frequency of second opinion or patient receipt of surgery by a second surgeon. Furthermore, there were no substantive sociodemographic or clinical correlates of second opinions or receipt of surgery from a second surgeon.

This is the first study to our knowledge that examined the nature of physician-patient discussions about CPM and patient reactions to surgeon recommendations regarding elective CPM. Published studies have documented the growth in receipt of CPM in the US over the last decade,6,18–21 and a few have addressed patient factors driving preferences for more extensive surgery.2 Other studies have examined surgeon perspectives but they have been limited by small samples, low response rates, or non-US practice settings.22,23

Some aspects of our study methods merit comment. The study was a large population-based survey in a diverse sample with a high survey response rate. We used weights and multiple imputation techniques to reduce non-response bias. Patient report of treatment deliberation and experiences were ascertained shortly after surgery. We were conservative with regard to specification of the main measures. For example, patients had to indicate that none of the 5 CPM treatment tradeoffs were discussed to be characterized as not having a substantive discussion. Furthermore, we performed sensitivity analyses to assure that main findings based on a priori decisions were robust for different specifications of key variables and different approaches to analyses. However, there were some limitations. Surgeon communication was reported by patients and thus may differ from a report from their surgeon. The population-based survey was necessarily retrospective. In particular, we evaluated strength of consideration of CPM after treatment which may have been influenced by deliberations and the surgical treatment ultimately performed. We had little information about potential barriers to discussion or care by second surgeons which may have affected our findings. Finally, results are limited to 2 large regions of the US.

IMPLICATIONS

Surgeons face a growing need to address patient interest in CPM for treatment of breast cancer. Communicating with patients about CPM is difficult because patient preferences are motivated by complex intuitive and affective reactions that may be difficult to elicit and address in a visit where a myriad of treatment options and potential outcomes need to be discussed. Under these circumstances, surgeons may not feel compelled to initiate a discussion of CPM or proactively make recommendations in women with no medical indication for the procedure in an effort to optimally facilitate patient participation in a complicated treatment decision process. Our findings are largely reassuring in that most patients are satisfied with surgical decision making and that first surgeon recommendation against CPM does not appear to substantively increase patient dissatisfaction or increase use of second opinions or loss of the patient to a second surgeon. However, the proportion of patients reporting a recommendation against CPM by their first surgeon was modest. The consequences of a greater number of surgeons advising against CPM are unknown, especially in women who strongly desire the procedure. For patients who remain uncertain about the benefits of CPM, a second opinion may be an appropriate source of additional information. Research is needed to develop and evaluate both decision tools for patients and training opportunities for surgeons that can facilitate these very important clinical encounters concerning challenging treatment decision issues.

Supplementary Material

Patient flow diagram. Flow diagram representing the final analytic sample (n=1,140) drawn from the iCanCare study population.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) of the National Institutes of Health under award number P01CA163233 to the University of Michigan.

The collection of cancer incidence data used in this study was supported by the California Department of Public Health pursuant to California Health and Safety Code Section 103885; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) National Program of Cancer Registries, under cooperative agreement 5NU58DP003862-04/DP003862; the NCI’s Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results Program under contract HHSN261201000140C awarded to the Cancer Prevention Institute of California, contract HHSN261201000035C awarded to the University of Southern California (USC), and contract HHSN261201000034C awarded to the Public Health Institute.

The collection of cancer incidence data in Georgia was supported by contract HHSN261201300015I, Task Order HHSN26100006 from the NCI and cooperative agreement 5NU58DP003875-04-00 from the CDC. The ideas and opinions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and endorsement by the State of California, Department of Public Health, the NCI, and the CDC or their Contractors and Subcontractors is not intended nor should be inferred. Funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

We acknowledge the outstanding work of our project staff (Mackenzie Crawford and Kiyana Perrino from the Georgia Cancer Registry; Jennifer Zelaya, Pamela Lee, Maria Gaeta, Virginia Parker, and Renee Bickerstaff-Magee from USC; Rebecca Morrison, Rachel Tocco, Alexandra Jeanpierre, Stefanie Goodell, Rose Juhasz, Kent Griffith, and Irina Bondarenko from the University of Michigan). We acknowledge with gratitude our survey respondents.

References

- 1.Albornoz CR, Matros E, Lee CN, et al. Bilateral Mastectomy versus Breast-Conserving Surgery for Early-Stage Breast Cancer: The Role of Breast Reconstruction. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2015;135(6):1518–1526. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000001276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosenberg SM, Sepucha K, Ruddy KJ, et al. Local Therapy Decision-Making and Contralateral Prophylactic Mastectomy in Young Women with Early-Stage Breast Cancer. Annals of surgical oncology. 2015;22(12):3809–3815. doi: 10.1245/s10434-015-4572-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Breast Cancer. [Accessed May 4, 2016];2016 https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/breast.pdf.

- 4.Boughey JC, Attai DJ, Chen SL, et al. Contralateral Prophylactic Mastectomy (CPM) Consensus Statement from the American Society of Breast Surgeons: Data on CPM Outcomes and Risks. Annals of Surgical Oncology. 2016:1–6. doi: 10.1245/s10434-016-5443-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nichols HB, Berrington de Gonzalez A, Lacey JV, Jr, Rosenberg PS, Anderson WF. Declining incidence of contralateral breast cancer in the United States from 1975 to 2006. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29(12):1564–1569. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.7395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.King TA, Sakr R, Patil S, et al. Clinical management factors contribute to the decision for contralateral prophylactic mastectomy. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29(16):2158–2164. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.29.4041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hamilton AS, Hofer TP, Hawley ST, et al. Latinas and breast cancer outcomes: population-based sampling, ethnic identity, and acculturation assessment. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18(7):2022–2029. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dillman DA, Smyth JD, Christian LM. Internet, Phone, Mail, and Mixed-Mode Surveys: The Tailored Design Method. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shumway D, Griffith KA, Jagsi R, Gabram SG, Williams GC, Resnicow K. Psychometric properties of a brief measure of autonomy support in breast cancer patients. BMC medical informatics and decision making. 2015;15:51. doi: 10.1186/s12911-015-0172-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martinez KA, Resnicow K, Williams GC, et al. Does physician communication style impact patient report of decision quality for breast cancer treatment? Patient education and counseling. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2016.06.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katz SJ, Hofer TP, Hawley S, et al. Patterns and correlates of patient referral to surgeons for treatment of breast cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2007;25(3):271–276. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.1846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Resnicow K, Abrahamse P, Tocco RS, et al. Development and psychometric properties of a brief measure of subjective decision quality for breast cancer treatment. BMC medical informatics and decision making. 2014;14:110. doi: 10.1186/s12911-014-0110-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hawley ST, Griggs JJ, Hamilton AS, et al. Decision involvement and receipt of mastectomy among racially and ethnically diverse breast cancer patients. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2009;101(19):1337–1347. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hawley ST, Lillie SE, Morris A, Graff JJ, Hamilton A, Katz SJ. Surgeon-level variation in patients' appraisals of their breast cancer treatment experiences. Annals of surgical oncology. 2013;20(1):7–14. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2582-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Groves RM, Fowler FJ, Jr, Couper MP, Lepkowski JM, Singer E, Torangeau R. Survey Methodology. John Wiley & Sons; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Little RJ, Rubin DB. Statistical Analysis with Missing Data. 2. Wiley-Interscience; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rubin DB. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. Hoboken, NY: John Wiley & Sons; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wong SM, Freedman RA, Sagara Y, Aydogan F, Barry WT, Golshan M. Growing Use of Contralateral Prophylactic Mastectomy Despite no Improvement in Long-term Survival for Invasive Breast Cancer. Annals of surgery. 2016 doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steiner CA, Weiss AJ, Barrett ML, Fingar KR, Davis PH. Trends in bilateral and unilateral mastectomies in hospital inpatient and ambulatory settings, 2005–2013. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Feb, 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grimmer L, Liederbach E, Velasco J, Pesce C, Wang CH, Yao K. Variation in Contralateral Prophylactic Mastectomy Rates According to Racial Groups in Young Women with Breast Cancer, 1998 to 2011: A Report from the National Cancer Data Base. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2015;221(1):187–196. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2015.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hawley ST, Jagsi R, Morrow M, et al. Social and Clinical Determinants of Contralateral Prophylactic Mastectomy. JAMA Surg. 2014;149(6):582–589. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2013.5689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bellavance E, Peppercorn J, Kronsberg S, et al. Surgeons' Perspectives of Contralateral Prophylactic Mastectomy. Annals of surgical oncology. 2016 doi: 10.1245/s10434-016-5253-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Musiello T, Bornhammar E, Saunders C. Breast surgeons' perceptions and attitudes towards contralateral prophylactic mastectomy. ANZ journal of surgery. 2013;83(7–8):527–532. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2012.06209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Patient flow diagram. Flow diagram representing the final analytic sample (n=1,140) drawn from the iCanCare study population.