Abstract

Ninety years old male was admitted to hospital due to breathlessness. The prominent findings were extensive blue-grey skin pigmentation and large left chylothorax. Drug induced lupus was diagnosed due to either minocycline chronic treatment or no alternative illness to explain his sub-acute disease. Minocycline therapy was stopped with gradual improvement of pleural effusion and skin discoloration. This case is the first presentation of minocycline induced lupus with chylothorax.

Keywords: Drug induced lupus, Minocycline, Chylothorax, Skin pigmentation

1. Introduction

Minocycline is a member of tetracycline family of antibiotics in widespread use for the treatment of acne vulgaris. It is also used as a disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis [1]. Minocycline may also provide good treatment results in select patients with localized or generalized bullous pemphigoid [2].

The drug is generally well tolerated and the most common adverse drug reactions are photosensitivity and esophagitis. Minocycline can cause a variety of pulmonary adverse effects, most notably organizing pneumonia and pulmonary infiltrates with eosinophilia [3]. Rarely, immune-mediated hypersensitivity syndromes have been observed such as serum sickness-like reactions, Steven-Johnson syndrome, autoimmune hepatitis, vasculitis and a lupus-like illness [4], [5]. The incidence and prevalence of minocycline induced lupus is unknown, either without pleural involvement or with pleural effusion [6]. Although minocycline-induced pigmentation noted to occur in the skin, subcutaneous fat, nails, teeth, gingivae, oral mucosa, lips, conjunctiva, sclera as well as various internal structures throughout the body there are no reports described colored pleural fluid. Furthermore, there are no reports described minocycline induced chylothorax.

To our knowledge, this is the first report of minocycline related colored chylous pleural effusion as a part of drug induced lupus.

2. Case report

A 91-year-old man with cognitive impairment, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, chronic atrial fibrillation with no anticoagulant treatment and bullous pemphigoid, presented with a two weeks history of increased dyspnea, weakness and palpitation. He had been taking minocycline 200 mg/day for previous two years for bullous pemphigoid.

On admission he was afebrile, normotensive, in moderate respiratory distress, and SpO2 was 95% on 4 L/min supplemental oxygen. The oxygen saturation on room air was 88%.

Physical examination revealed well-circumscribed blue-grey pigmentation on the shins and forearms (Fig. 1), irregular cardiac rhythm and was remarkable for dullness to percussion and decreased breath sounds over the left hemithorax.

Fig. 1.

Well-circumscribed blue-grey skin pigmentation.

The peripheral white blood cell count was 5.8 × 103 cells/μL with 8.7% eosinophils and his hemoglobin count was 10.9 g/dL. Troponin level was normal. Electrocardiogram revealed atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response. Chest radiograph showed large left pleural effusion. Transthoracic echocardiogram displayed normal left ventricular chamber size with normal systolic function and moderate aortic stenosis with a gradient of 47.00 mm Hg.

Left thoracentesis was performed with evacuation of 1500 CC yellow colored exudative pleural fluid, which contained reactive mesothelial cells and fibrinous exudate with scattered granulocytes and few lymphocytes (Fig. 2). Pleural fluid triglyceride and cholesterol concentrations were determined to establish whether a chylous fluid was present. The levels were 164 mg/dL and 78 mg/dL respectively. The pleural fluid cholesterol to triglyceride ratio was found to be 0.47: the finding is compatible with chylous pleural effusion.

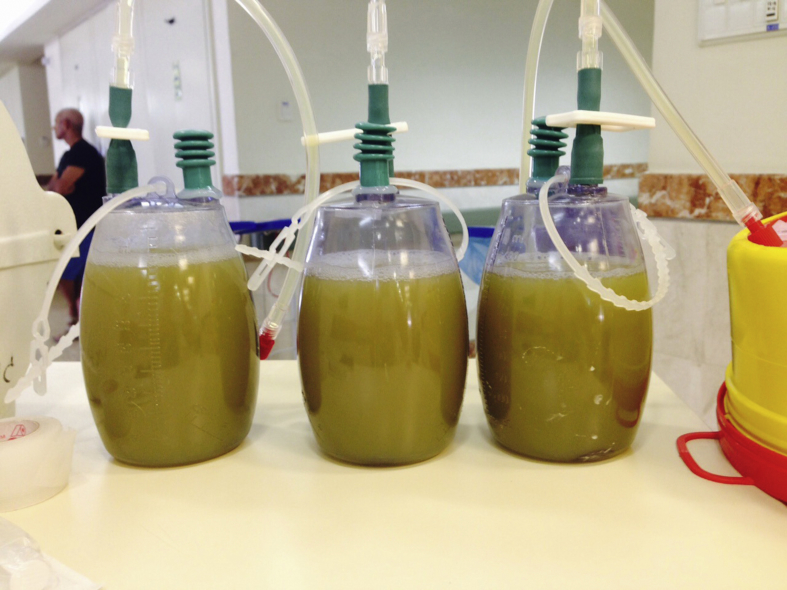

Fig. 2.

Yellow colored pleural fluid.

Cultures of the pleural fluid were negative, as were the Ziehl-Neelsen stainings.

Computed tomogram of the chest displayed normal parenchyma with left low lobe atelectasis and left moderate-size pleural effusion. No lymphadenopathy was observed.

Few days after the thoracentesis repeated chest radiograph indicated recurrence of pleural effusion. Tube thoracostomy into the pleural cavity was done for continuous drainage of chylothorax.

Minocycline side effect was suspected and lupus-like effect was considered. Minocycline treatment was discontinued.

Serological tests were positive for ANA and anti-dsDNA antibodies. The further investigation revealed negative ANA pattern and negative ANA in dilution 1:160. Antibodies against extractable nuclear antigens (ENA) were negative as well as pANCA, cANCA, Anti Cardiolipin and B2 Glycoprotein antibodies. Complement levels were within the reference range. Test for anti-histone antibodies was also negative.

No evidence of minocycline crystals was found on cytological examination of pleural fluid. The lymphocyte-stimulation test was not performed.

Two weeks following minocycline discontinuation the pleural effusion had completely resolved, chest tube was withdrawn and patient was discharged.

Four months later he remained well with no sign of pleural effusion recurrence and partial resolution of skin pigmentation.

3. Discussion

Minocycline is the only tetracycline associated with drug-induced lupus [7], [8]. This observation might be due to the fact that minocycline is prescribed much more commonly for long-term use, especially for treatment of acne, whereas doxycycline and tetracycline more likely prescribed for acute infections with short duration of therapy.

Substantial dose of minocycline (100, 200 mg/d) taken over prolonged periods often cause severe pigmentation like as reported in our patient [4]. The pathogenesis of minocycline-induced lupus is not known and there is a little evidence associating minocycline cumulative doses and the development of lupus-like illness [9]. In a case series from West of Scotland it was concluded that the use of minocycline for the treatment of acne and rheumatic diseases is associated with an 8.5 fold increased risk of developing a lupus-like syndrome [10]. The average time to onset of minocycline-induced lupus is two years after initiation of therapy, and it may be delayed as long as six years [7]. On the other hand an unusual feature of minocycline-induced lupus is the ability of the drug, on rechallenge, to exacerbate the symptoms, usually within 12–24 h [6].

There are no definitive tests or criteria for the diagnosis of drug-induced lupus. However, the diagnosis is highly likely in the presence of a history of taking one of the drugs known to be associated with this condition for at least one month with the development of one or more clinical symptoms of SLE; a positive test for ANA; and spontaneous resolution of the clinical manifestations after the offending drug has been discontinued [11]. Long-term therapy with associated drug, transient serology for ANA and resolution after suspected medication withdrawal are supporting the diagnosis of drug induced lupus. No clinical signs of lupus, as arthralgia/arthritis or fever, were detected during the admission.

Our patient has taken minocycline about two years with development of pleural effusion as a presentation of lupus-like illness. Although ANA are usual in drug-induced lupus associated with drugs such as hydralazine and procainamide, a negative test for ANA does not exclude a diagnosis of minocycline-induced lupus [6], [12], [13]. The study of Lawson et al. showed that four of 23 patients were negative for ANA and would not therefore fulfill the proposed criteria for drug-induced lupus [6]. Drug induced lupus with chylothorax was reported in some cases [14]. However, the tests for either ANA and anti-DNA levels or lipoproteins/chylomicrons in pleural fluid did not perform in our case. The results of LDH in pleural fluid were not available.

Another difference between minocycline-induced lupus and cases of drug-induced lupus secondary to hydralazine and procainamide is the frequency with which anti-histone antibodies are detected. Whilst these antibodies are present in more than 95% of cases of hydralazine and procainamide-induced lupus they were absent in nine out of nine of patients with minocycline-induced lupus in study of Lawson et al. [6], [15].

Other group has also found that anti-histone antibodies were uncommon (4 of 31 tests) among patients with minocycline-induced lupus [16].

Few reports were published about the pulmonary toxicity of minocycline [17], [18]. Radiological signs in these cases included pulmonary infiltrates, exudative pleural effusion and lymphadenopathy. Our patient had no pulmonary parenchymal and mediastinal lymph node abnormalities. Because of that is more likely that the pleural effusion was a part of immune response associated with drug induced lupus than direct pulmonary toxicity of minocycline. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS syndrome) was described with minocycline [19]. However, this severe multisystem illness is not compatible with our reported patient.

Chylous effusions are caused by a heterogeneous group of disorders that result in the disruption of the normal lymphatic flow. The patient denied history of trauma and surgery. The etiologies of chylothorax including infection and malignancy were not likely. Although drug-induced, typically, exudative pleural effuses are occurring with increasing incidence with the advent of new pharmaceutical agents; only cases of dasatinib-related chylothorax have rarely been reported [20], [21]. The possible mechanism of dasatinib-related chylothorax include inhibiting platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta (PDGFR-β) that leads to lymphatic dysregulation and microvasculopathy [22]. PDGFR-β and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) inhibition by minocycline is also possibly related to microscopic disruptions in lymphatic channels and development of chylothorax [23].

Minocycline, intriguingly, is in use to treat intractable pleural effusion, as persistent chylothorax, was reported to be successful in many, but not in all cases [24].

In conclusion, although minocycline is considered to be a safe drug it may be responsible for serious adverse effects such as drug-induced lupus with chylothorax. Moreover, this case is interesting because of the fact that minocycline may be responsible not only for pigmentation of skin, nails, teeth and various internal structures throughout the body but also for yellow discoloration of the pleural fluid.

References

- 1.Breedveld F.C. Minocycline in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:794–796. doi: 10.1002/art.1780400503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Loo W.J., Kirtschig G., Wojnarowska F. Minocycline as a therapeutic option in bullous pemphigoid. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2001;26:376–379. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2230.2001.00838.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Branley H.M., Kolvekar S., Brull D. Minocycline induced organizing pneumonia resolving without recourse to corticosteroids. Respir. Med. 2009;2:137–140. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown R.J., Rother K.I., Artman H., Mercurio M.G., Wang R., Looney R.J. Minocycline-induced drug hypersensitivity syndrome followed by multiple autoimmune sequelae. Arch. Dermatol. 2009;145:63–66. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2008.521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Joshi H., Chhikara V., Arya K., Pathak R. Some undesirable effects reported in past five years related to Minocycline therapy: a review. Ann. Biol. Res. 2010;1:64–71. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lawson T.M., Amos N., Bulgen D., Wiliams B.D. Minocycline-induced lupus: clinical features and response to rechallenge. Rheumatology. 2001;40:329–335. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/40.3.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shapiro L.E., Knowles S.R., Shear N.H. Comparative safety of tetracycline, minocycline, and doxycycline. Arch. Dermatol. 1997;133:1224–1230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Masson C., Chevailler A., Pascaretti C., Legrand E., Brégeon C., Audran M.J. Minocycline related lupus. Rheumatol. 1996;23:2160–2161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marai I., Schoenfeld Y. Lupus – like disease due to minocycline. Harefuah. 2002;141(2):151–152. 223, 222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gordon M.M., Porter D. Minocycline induced lupus : case series in the West of Scotland. J. Rhematol. 2001;28(5):1004–1008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vedove C.D., Del Giglio M., Schena D., Girolomoni G. Drug-induced lupus erythematosus. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2009;301:99–105. doi: 10.1007/s00403-008-0895-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hess E. Drug-related lupus. N. Engl. J. Med. 1988;318:1460–1462. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198806023182209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Knights S.E., Leandro M.J., Khamashta M.A., Hughes G.R.V. Minocycline-induced arthritis. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 1988;16:587–590. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee C.K., Han J.M., Le K.N., Lee E.Y., Shin J.H., Cho Y.S., Koh Y., Yoo B., Moon H.B. Concurrent occurrence of chylothorax, chylous ascites, and protein loosing enteropathy in systemic lupus erythematosus. J. Rheumatol. 2002;29(6):1330–1333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hess E.V. Environmental lupus syndrome. Br. J. Rhematol. 1995;34:597–601. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/34.7.597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elkayam O., Yaron M., Caspi D. Minocycline-induced autoimmune syndromes: an overview. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;28:392–397. doi: 10.1016/s0049-0172(99)80004-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arai S., Shinohara Y., Kato Y., Hirano S., Yoshizawa A., Hojyo M., Kobayashi N., Sugiyama H., Kudo K. Case of minocycline-induced pneumonitis with bilateral pleural effusion. Arerugi. 2007 Oct;56(10):1293–1297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bando T., Fujimura M., Noda Y., Hirose J., Ohta G., Matsuda T. Minocycline-induced pneumonitis with bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy and pleural effusion. Intern Med. 1994 Mar;33(3):177–179. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.33.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shaughnessy K.K., Bouchard S.M., Mohr M.R., Herre J.M., Salkey K.S. Minocycline –induced drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) with persistent myocarditis. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2010;62(20):315–318. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.05.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang Y.M., Wang C.H., Huang J.S., Lan Y.J. Dasatinib-related chylothorax. Turk. J. Hematol. 2015;32:68–72. doi: 10.4274/tjh.2012.0196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goldblatt M.R., Gurung P., Doelken P., Huggind J., Sahn S.A. Dastinib-induced pleural effusions: a pharmaceutical model for yellow nail syndrome? Chest. 2009;136 (4_MeetingAbstracts): 61S-e-62S. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berger G., Song S., Meyer-Morse N., Bergsland E., Hanaham D. Benefits of targeting both pericytes and endothelial cells in the tumor vasculature with kinase inhibitors. J. Clin. Investig. 2003;111:1287–1295. doi: 10.1172/JCI17929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yao J.S., Chen Y., Zhai W., Xu K., Young W.L., Yang G.Y. Minocycline exerts multiple inhibitory effects on vascular endothelial growth factor-induced smooth muscle cell migration: the role of ERK1/2, PI3K, and matrix metalloproteinases. Circ. Res. 2004;95:364–371. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000138581.04174.2f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cho Hyun Jin, Kim Dong Kwan, Lee Geung Dong, Sim Hee Je, Choi Se hoon, Kim Hyeong Ryul, Kim Yong -Hee, Park Seung-Il. Chylothorax complicating pulmonary resection for lung cancer: effective management and pleurodesis. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2014;97:408–413. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.10.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]