Abstract

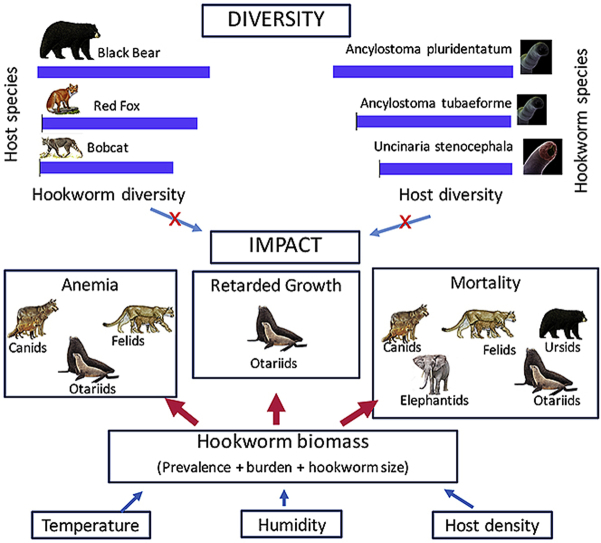

Hookworms are blood-feeding nematodes that parasitize the alimentary system of mammals. Despite their high pathogenic potential, little is known about their diversity and impact in wildlife populations. We conducted a systematic review of the literature on hookworm infections of wildlife and analyzed 218 studies qualitative and quantitatively. At least 68 hookworm species have been described in 9 orders, 24 families, and 111 species of wild mammals. Black bears, red foxes, and bobcats harbored the highest diversity of hookworm species and Ancylostoma pluridentatum, A. tubaeforme, Uncinaria stenocephala and Necator americanus were the hookworm species with the highest host diversity index. Hookworm infections cause anemia, retarded growth, tissue damage, inflammation and significant mortality in several wildlife species. Anemia has been documented more commonly in canids, felids and otariids, and retarded growth only in otariids. Population- level mortality has been documented through controlled studies only in canines and eared seals although sporadic mortality has been noticed in felines, bears and elephants. The main driver of hookworm pathogenic effects was the hookworm biomass in a population, measured as prevalence, mean burden and hookworm size (length). Many studies recorded significant differences in prevalence and mean intensity among regions related to contrasts in local humidity, temperature, and host population density. These findings, plus the ability of hookworms to perpetuate in different host species, create a dynamic scenario where changes in climate and the domestic animal-human-wildlife interface will potentially affect the dynamics and consequences of hookworm infections in wildlife.

Keywords: Ancylostoma, Hookworm, Uncinaria, Pathology, Epidemiology, Wildlife

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

At least 68 hookworm species have been described in 111 species of wild mammals.

-

•

Wildlife are permanent hosts of important hookworms of humans and domestic animals.

-

•

Hookworms cause anemia, retarded growth and mortality in canids, felids and otariids.

-

•

Hookworm biomass is a key driver of pathogenic effects in a host population.

1. Introduction

Hookworms (Nematoda: Strongylida: Ancylostomatoidae) are blood-feeding nematodes that parasitize the mammalian alimentary system (Popova, 1964). Regardless of the large diversity within this parasitic group, all Ancylostomatoidae species share basic morphologic, physiologic and life history traits that translate into similar consequences for their host. In humans and domestic animals, the deleterious effects of hookworms are well documented at the individual and population level, being one of the most significant neglected tropical diseases of humans (Bartsch et al., 2016), and an important cause or contributory factor of anemia and neonatal mortality in domestic dogs and cats (Traversa, 2012). Despite the potential deleterious impact in their hosts, there is no currently available summary on the number of hookworm species described and the significance of hookworm infection in free-ranging wild mammals.

The modification of landscapes and climate change create additional challenges for wildlife disease study, and it is predicted that these phenomena will modify the dynamics of nematode infections (Weaver et al., 2010, Weinstein and Lafferty, 2015). Therefore, improved description, analysis, and understanding of hookworm infections in wildlife are necessary to direct future research efforts and understand host-parasite relationships in a regional and global scale.

In this context, the objectives of this review are to i) provide a systematic summary of the literature available on hookworm infections of wildlife, ii) evaluate the reported hookworm diversity in wildlife corrected for sampling effort, iii) identify significant pathologic features of these infections and the potential drivers of the deleterious effects of hookworms on wildlife hosts.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Searching methods and inclusion criteria

A systematic literature review of Ancylostomatoidae nematodes of wildlife was performed using Google scholar, Web of Science and Biosis search engines on April 27th, 2016; following recommended practices for systematic reviews in the field of parasitology (Haddaway and Watson, 2016). The initial term searched was “hookworm(s)” AND “wildlife”. The abstracts of the papers retrieved were reviewed and included in the study if they met the following criteria: i) The parasitic nematode found belonged to a genus within the Ancylostomatoidae family. (Studies describing the presence of eggs or nematodes as “hookworms” or “strongyles” without genus identification were excluded). ii) The host species was any free-ranging non-domesticated (wild) animal. Captive wild animals were only included if they were taken from the wild soon before the study, and therefore, transmission of parasites was assumed to occur in the wild. In the case of domestic animal-wildlife hybrids, these were included if they were free-ranging. Additional searches were performed using the preliminary list of genera identified in the initial search plus the word “wildlife” (e.g. “Ancylostoma wildlife”). The studies selected based on abstract screening (N = 216) were fully reviewed and the most significant findings summarized into a master spreadsheet (supplementary material).

2.2. Data analyses

To identify host species with high hookworm diversity, an index penalized for sampling effort was calculated based on previously published methods (Nunn et al., 2003, Ezenwa et al., 2006). Briefly; the citations for each host species were extracted from the databases and after factor analyses condensed into one variable, citation-principal component (citation-PC). Additional sampling effort measures included the number of animals sampled in the reviewed studies and the number of studies in our review for each host species. Negative binomial regression models were fitted for each measure of sampling effort and the residuals were used as a penalized index of hookworm diversity. To assess which hookworm species parasitized higher number of wildlife species a similar approach was used with the difference that citation-PC was not used because of “too high” penalization for highly studied hookworm species infecting humans or domestic animals (e.g. Necator americanus). We used instead, the total number of mammalian species screened in the studies where that hookworm species was found, since in many studies several host species were assessed. The penalized measurements of host diversity were calculated as previously described.

To assess which factors influenced the likelihood of finding a mammalian-hookworm species relationship that had detrimental effects for the host, the paired mammalian-hookworm species were categorized as 1 if there was at least one study describing adverse health effects at the individual or population level and as 0 if there were no studies registering such effect. Evidence of adverse health effect included mortality, anemia, retarded growth, and significant degrees of macroscopic or histologic tissue damage (e.g. fibrosis, inflammatory infiltrate). Generalized linear models were fitted using these two categories (no pathologic effect vs. pathologic effect) as binomial response and the number of studies for each mammalian-hookworm species relationship, number of animals sampled, Citation-PC for the animals and hookworm species, hookworm host diversity index, average prevalence in the studies reporting pathology or no effect, mean infection intensity in studies reporting pathology or no effect, average host weight (in kilograms), average hookworm length (in millimeters), host weight-hookworm size ratio, geographic location (continent) and study methodology were used as predictors in the general model. We used a stepwise algorithm and calculated Akaike's information criteria (AIC) to determine which set of independent variables (including potential interactions between covariates) provided the best fit to the data.

3. Characterization of studies describing hookworm infections in wild animals

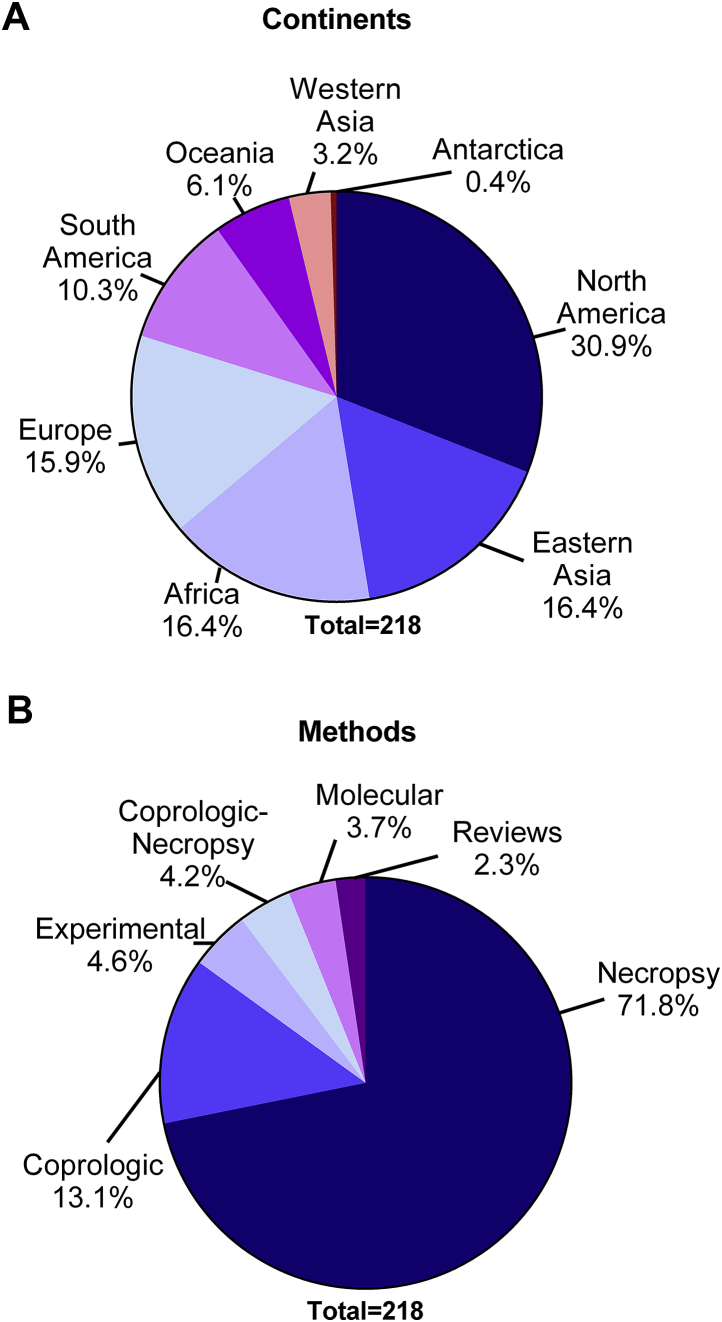

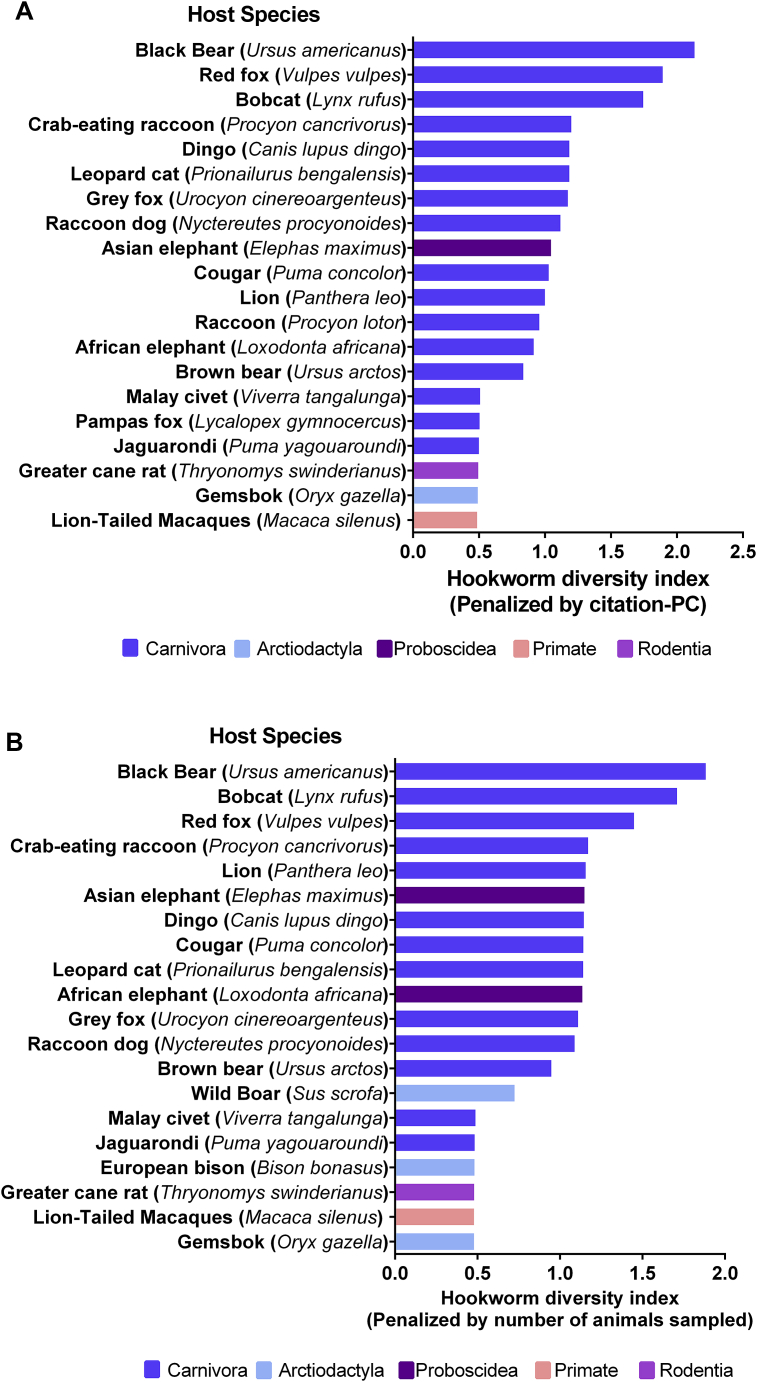

The initial search yielded 3710 abstracts in Google scholar, 38 in Web of Science and 42 in Biosis. Out of these, 180 papers met the inclusion criteria and later searches by hookworm genera produced additional 38 papers, totaling 218 studies. Most of the studies were conducted in North America (n = 66) followed by Eastern Asia (n = 35) and Europe (n = 35) (Fig. 1a), and the most commonly used methodology of data collection was through necropsies of culled or incidentally found dead animals (n = 153). Studies using experimental or molecular approaches for data collection corresponded to a minority of the papers (n = 10 and n = 8 respectively) (Fig. 1b). Most of the studies described hookworm infections in the order Carnivora (n = 125), particularly within the Canidae (n = 73) Felidae (n = 28) and Otariidae (n = 25) families. Regarding host species, most studies were performed in red fox (n = 26), coyote (n = 16), raccoons (n = 11) and Northern fur seals (n = 10). After penalizing by sampling effort (number of studies and number of animals), the host species harboring the larger number of hookworm species were black bear (Ursus americanus), bob cat (Lynx rufus), and red fox (Vulpes vulpes) (Fig. 2a and b).

Fig. 1.

Percentage of studies describing hookworm infections in wildlife hosts divided by continent (a) and the main methodology used to collect the data (b).

Fig. 2.

Hookworm diversity index penalized by the citation principal component (citation-PC) of the host species (a) and the number of sampled animals of each host species (b). Bar colors indicate represented mammalian orders. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

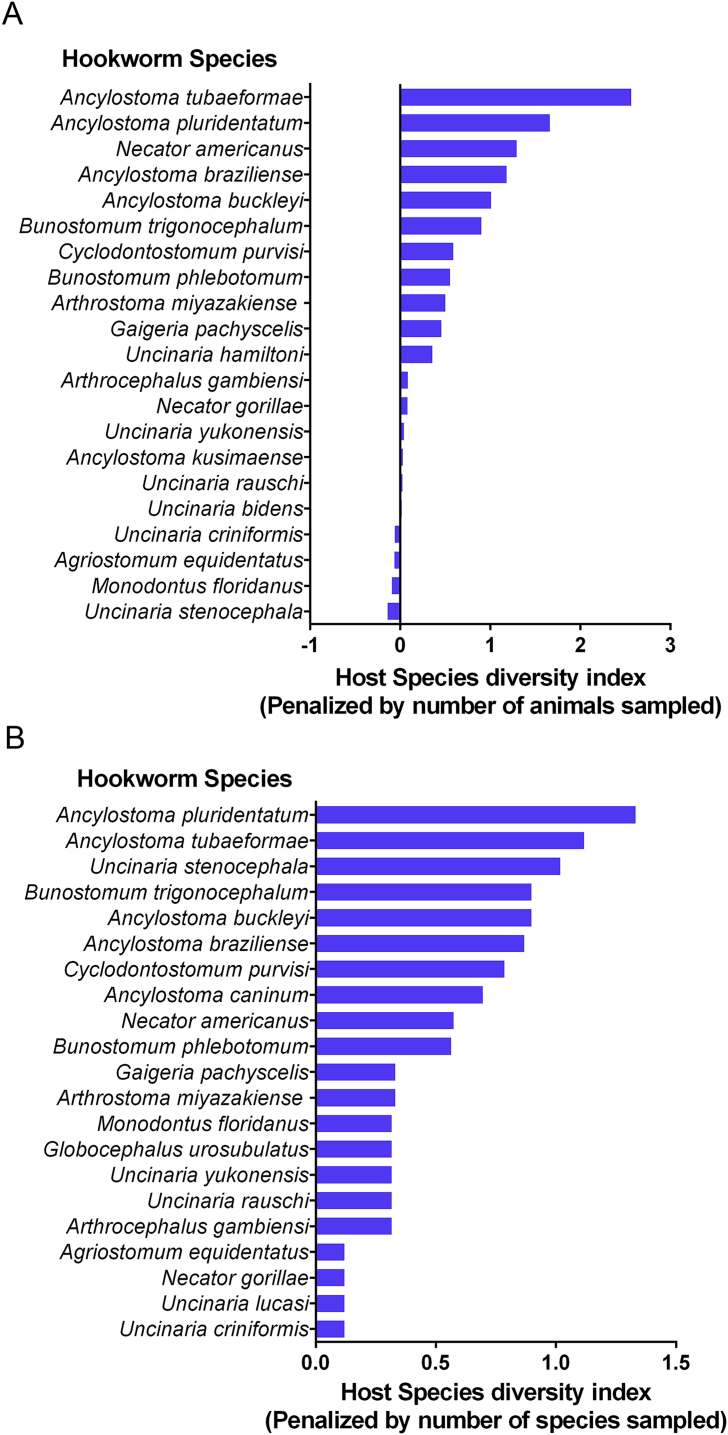

At least 68 hookworm species have been described in 9 orders, 22 families, and 108 species of wild mammals. Before penalizing for sampling effort the hookworm species with the largest host range were Uncinaria stenocephala (n = 11), Ancylostoma caninum (n = 10), Ancylostoma tubaeforme (n = 10), Ancylostoma pluridentatum (n = 6) and Necator americanus (n = 6); however, after penalizing for the number of sampled animals (Fig. 3a) or the number of species assessed in the studies of a particular hookworm species (Fig. 3b), U. stenocephala and A. caninum became less generalists, but the feline hookworms A. tubaeforme, A. pluridentatum, A. braziliencis and the human nematode N. americanus remained as more generalist parasites, affecting several host species.

Fig. 3.

Host species diversity index for represented hookworm species, penalized by number of animals sampled (a) and the number of animal species sampled in each study (b).

Thirty-five studies reported detrimental effects of hookworms at the individual or population level. All these studies were conducted on carnivores with the exception of a few reports on elephants and giraffes (n = 5). The final model to assess the likelihood of finding a detrimental host-hookworm relationship included the level of study of the particular hookworm species (citation-PC), the mean prevalence and infection intensity in the studies and the average hookworm length as predictors (binomial GLM, p value = 0.0003, df = 79); however, only the mean prevalence was statistically significant (p-value = 0.0008).

4. Mammalian orders and families infected with hookworms

4.1. Carnivora

4.1.1. Canidae

Nine hookworm species have been described in canids, all of them members of the Ancylostoma, Uncinaria and Arthrostoma genera (Table 1). Among canids, the best studied species are the red fox (Vulpes vulpes) and coyotes (Canis latrans), probably related to their widespread distribution and because they are commonly hunted/culled.

Table 1.

Canine hosts infected with hookworms with the corresponding references.

In Asia, the native hookworms Arthrostoma miyazakiense and Ancylostoma kusimaense are the most common gastrointestinal nematodes of native (raccoon dogs, Nyctereutes procyonoides) and introduced canids (red foxes) (Sato et al., 2006, Shin et al., 2007). Interestingly, introduced raccoon dogs in Denmark lack their native Asian hookworms but are infected with U. stenocephala (48.5% prevalence), a very common parasite of red foxes in that region (Al-Sabi et al., 2013), highlighting the potential of canine hookworms to infect multiple species (see Table 1).

Many common canine hookworms such U. stenocephala, A. caninum and A. ceylanicum are important zoonotic pathogens, especially in Australia and Southeast Asia (Smout et al., 2013).

4.1.2. Felidae

Twelve species of hookworms within the Ancylostoma, Uncinaria, Galoncus and Arthrostoma genera have been described in wild felids (Table 2). Despite the significant diversity of hookworm species within felines, and the vulnerable conservation status of many of them, considerably less research has been performed on hookworm parasites in felids compared to canids, and many aspects of their hookworms' biology are unknown.

Table 2.

Feline hosts infected with hookworms and corresponding references.

| Host Species | Hookworm species | References |

|---|---|---|

| Bobcat (Lynx rufus) | Ancylostoma caninum | Miller and Harkema, 1968, Little et al., 1971, Mitchell and Beasom, 1974, Schitoskey and Linder, 1981, Mclaughlin et al., 1993, Hiestand et al., 2014 |

| Ancylostoma braziliense | Miller and Harkema, 1968, Mclaughlin et al., 1993 | |

| Ancylostoma tubaeformae | Tiekotter, 1985, Mclaughlin et al., 1993 | |

| Ancylostoma pluridentatum | Mclaughlin et al., 1993 | |

| Iriomote cats (Prionailurus iriomotensis) | Uncinaria maya | Hasegawa, 1989, Yasuda et al., 1994 |

| Bengal tiger (Panthera tigris) | Galoncus perniciosus | Kalaivanan et al., 2015 |

| Leopard (Panthera pardus) | Galoncus tridentatus | Khalil, 1922a, Pythal et al., 1993 |

| Canadian lynx (Lynx canadensis) | Ancylostoma caninum | Smith et al., 1986 |

| Uncinaria stenocephala | Smith et al., 1986 | |

| Cougar (Puma concolor) | Ancylostoma tubaeformae | Waid and Pence 1988 |

| Ancylostoma pluridentatum | Forrester et al., 1985, Dunbar et al., 1994 | |

| Ancylostoma buckleyi | Thatcher 1971 | |

| Geoffroy's cat (Leopardus geoffroyi) | Ancylostoma tubaeformae | Beldomenico et al., 2005, Fiorello et al., 2006 |

| Iberian Lynx (Lynx pardinus) | Ancylostoma spp | Vicente et al., 2004 |

| Ancylostoma tubaeformae | Millán and Blasco-Costa, 2012 | |

| Jaguar (Felis onca) | Ancylostoma pluridentatum | Thatcher 1971 |

| Jaguarondi (Puma yagouaroundi) | Ancylostoma tubaeformae | Thatcher 1971 |

| Ancylostoma pluridentatum | Thatcher 1971 | |

| Leopard cat (Prionailurus bengalensis) | Ancylostoma tubaeformae | Yasuda et al., 1993 |

| Arthrostoma hunanensis | Yasuda et al., 1993 | |

| Uncinaria felidis | Yasuda et al., 1993, Yasuda et al., 1994, Shimono et al., 2012 | |

| Lion (Panthera leo) | Uncinaria stenocephala | Smith and Kok 2006 |

| Ancylostoma braziliense | Smith and Kok 2006 | |

| Ancylostoma paraduodenale | Bjork et al., 2000 | |

| Ancylostoma spp | Muller-Graf, 1995, Bjork et al., 2000 | |

| Margay cat (Leopardus wiedii) | Ancylostoma pluridentatum | Thatcher 1971 |

| Ocelot (Leopardus pardalis) | Ancylostoma tubaeformae | Pence et al., 2003, Fiorello et al., 2006 |

| Ancylostoma pluridentatum | Thatcher 1971 | |

| Uncinaria sp. | Fiorello et al., 2006 |

The dog hookworm A. caninum infects felids in many areas where wild cats are sympatric with domestic or wild canids, such as the southeastern United States (Miller and Harkema, 1968, Little et al., 1971, Mitchell and Beasom, 1974). In other areas, however, the domestic cat hookworms, A. tubaeforme and A. braziliense, are the predominant species in wild felids (Waid and Pence, 1988, Pence et al., 2003, Smith and Kok, 2006), and in some occasions these wildlife infections are most likely because of spillover from feral domestic cats (Millán and Basco-Costa, 2012).

In Asia, Uncinaria felidis and Uncinaria maya are the most common hookworms of native felids such as the leopard (Prionailurus bengalensis) and Iriomote cats (Prionailurus iriomotensis) (Hasegawa, 1989, Yasuda et al., 1993, Shimono et al., 2012). Although apparently rare, the nematode Arthrostoma hunanensis infects the bile duct of leopard cats in some areas (Yasuda et al., 1993).

4.1.3. Otariidae

Four Uncinaria species have been described in eared seals (otariids); however, molecular analyses suggest that there are at least 5 additional undescribed Uncinaria species (Nadler et al., 2013; Seguel et al., 2017) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Eared seals (otariids) infected with hookworms and corresponding references.

| Host Species | Hookworm species | References |

|---|---|---|

| Australian fur seal (Arctocephalus pusillus doriferus) | Uncinaria hamiltoni | Ramos et al., 2013 |

| Australian sea lion (Neophoca cinerea) | Uncinaria sanguinis | Haynes et al., 2014, Marcus et al., 2014a, Marcus et al., 2014b, Marcus et al., 2015a, Marcus et al., 2015b |

| California Sea Lion (Zalophus californianus) | Uncinaria lyonsi | Lyons et al., 2000, Lyons et al., 2001, Lyons et al., 2005, Acevedo-Whitehouse et al., 2006, Spraker et al., 2007, Lyons et al., 2011b, Kuzmina and Kuzmin, 2015 |

| Galapagos sea lion (Zalophus wollebaeki) | Uncinaria sp | Herbert 2014 |

| Juan Fernandez fur seal (Arctocephalus phillippii) | Uncinaria sp | Sepulveda, 1998 |

| New Zealand fur seal (Arctocephalus forsteri) | Uncinaria sp | Ramos et al., 2013 |

| New Zealand sea lion (Phocarctos hookeri) | Uncinaria sp | Castinel et al., 2006, Castinel et al., 2007a, Castinel et al., 2007b, Acevedo-Whitehouse et al., 2009, Chilvers et al., 2009, Michael et al., 2015 |

| Northern fur seal (Callorrhinus ursinus) | Uncinaria lucasi | Olsen and Lyons, 1965, Lyons et al., 1978, Lyons et al., 1997, Lyons et al., 2000, Lyons et al., 2001, Lyons et al., 2003, Delong et al., 2009, Lyons et al., 2011a, Lyons et al., 2011b, Lyons et al., 2014 |

| South American fur seal (Arctocephalus australis) | Uncinaria hamiltoni | Katz et al., 2012, Nadler et al., 2013 |

| Uncinaria sp | Seguel et al., 2011, Seguel et al., 2013, Seguel et al., 2017 | |

| South American sea lion (Otaria flavescens) | Uncinaria hamiltoni | Berón-vera et al., 2004 |

| Steller sea lion (Eumatopias jubatus) | Uncinaria lucasi | Lyons et al., 2003, Nadler et al., 2013 |

4.1.4. Procyonidae

Six species of hookworms within the Necator, Arthrocephalus, Ancylostoma, Arthrostoma and Uncinaria genera have been described in procyonids (Table 4). Most studies in procyonids have been conducted in raccoons (Procyon lotor), which in their native North America are infected with Arthrocephalus lotoris; however, in Japan, where they have been introduced, raccoons are infected with the native raccoon dog hookworms Ancylostoma kusimaense and Arthrostoma miyazakiense (Matoba et al., 2006, Sato and Suzuki, 2006).

Table 4.

Procyonids infected with hookworms and corresponding references.

| Host Species | Hookworm species | References |

|---|---|---|

| Crab-eating raccoon (Procyon cancrivorus) | Necator urichi | Cameron 1936 |

| Uncinaria maxillaris | Vicente et al., 1997 | |

| Uncinaria bidens | Vicente et al., 1997 | |

| Coati (Nasua nasua) | Uncinaria bidens | Duarte 2016 |

| Raccoon (Procyon lotor) | Arthrocephalus lotoris | Dikmans and Goldberg, 1949, Jordan and Hayes, 1959, Gupta, 1961, Balasingam, 1964, Snyder and Fitzgerald, 1985, Cole and Shoop, 1987, Yabsley and Noblet, 1999, Ching et al., 2000, Kresta et al., 2009 |

| Ancylostoma spp | Popiołek et al., 2011 | |

| Ancylostoma kusimaense | Matoba et al., 2006, Sato and Suzuki, 2006 | |

| Arthrostoma miyazakiense | Sato and Suzuki 2006 |

4.1.5. Mustelidae

Four species of hookworms within the Uncinaria and Tetragomphius genera and at least one unknown species within the Ancylostoma genus have been described in mustelids (Table 5). The most studied host species is the European badger (Meles meles), which is usually infected with Uncinaria criniformis, and in Korea Tetragomphius procyonis has been described in the Asian badger (Meles leucurus) (Son et al., 2009).

Table 5.

Mustelids infected with hookworms and corresponding references.

| Host Species | Hookworm species | References |

|---|---|---|

| Badger (Meles meles) | Uncinaria criniformis | Loos-Frank and Zeyhle, 1982, Magi et al., 1999, Torres et al., 2001, Millán et al., 2004, Rosalino et al., 2006, Cerbo et al., 2008, Stuart et al., 2013 |

| Tetragomphius procyonis | Son et al., 2009 | |

| Hog badger (Arctonyx collaris) | Tetragomphius arctonycis | Jansen 1968 |

| Japanese badger (Meles anakuma) | Tetragomphius melis | Ohbayashi et al., 1974, Ashizawa et al., 1976, Marcus et al., 2015a, Marcus et al., 2015b |

| Pine martens (Martes martes) | Uncinaria criniformis | Segovia et al., 2007 |

| Uncinaria sp. | Borecka et al., 2013 | |

| Ancylostoma spp | Borecka et al., 2013 |

In Europe, pine martens (Martes martes) are infected with Uncinaria sp., U. criniformis and an Ancylostoma sp. (Segovia et al., 2007, Borecka et al., 2013).

4.1.6. Ursidae

Six species of hookworms within the Ancylostoma, Arthrocephalus and Uncinaria genera have been described in bears (Table 6). The most important hookworm species in black bears is Uncinaria rauschi, which can reach up to 72% prevalence in some areas of Canada (Catalano et al., 2015a, Catalano et al., 2015b). Uncinaria yukonenesis is more common in brown bears in North America, while in Japan brown bears are infected with Ancylostoma malayanum (Catalano et al., 2015a, Catalano et al., 2015b, Asakawa et al., 2006). The canine hookworm, A. caninum, and the raccoon hookworm, A. lotoris, infect black bears in the southeastern United States; however, the mean intensities are usually low (<15 nematodes per animal) (Crum et al., 1978, Foster et al., 2011).

Table 6.

Bear species (ursids) infected with hookworms and corresponding references.

| Host Species | Hookworm species | References |

|---|---|---|

| Black Bear (Ursus americanus) | Ancylostoma caninum | Foster et al., 2011, Crum et al., 1978 |

| Ancylostoma tubaeformae | Foster et al., 2011 | |

| Arthrocephalus lotoris | Crum et al., 1978 | |

| Uncinaria rauschi | Olsen, 1968, Catalano et al., 2015a, Catalano et al., 2015b | |

| Uncinaria yukonensis | Frechette and Rau 1977 | |

| Uncinaria sp. | Worley et al., 1976 | |

| Brown bear (Ursus arctos) | Ancylostoma malayanum | Asakawa et al., 2006 |

| Uncinaria rauschi | Olsen 1968 | |

| Uncinaria yukonensis | Choquette et al., 1969, Rausch et al., 1979, Catalano et al., 2015a, Catalano et al., 2015b | |

| Uncinaria sp. | Greer, 1972, Worley et al., 1976, Kilinc et al., 2015 |

4.1.7. Mephtididae, Herpestidae, Phocidae, Hyenidae and Viverridae

There are few studies reporting hookworm infections in the Mephitidae (skunks), Herpestidae (mongoose), Phocidae (true seals), Hyenidae (hyenas) and Viverridae (civets) families (Table 7). Skunks can be infected with the raccoon hookworm A. lotoris in North America (Dikmans and Goldberg, 1949), while in South America the native skunk, Conepatus chinga, harbor its own hookworm, Ancylostoma conepati (Ibáñez, 1968). In Taiwan a few individuals of Arthrostoma vampire were found in the Palawan stink badger (Mydaus marchei) (Schmidt and Kuntz, 1968). Arthrocephalus gambiensi has been described in herpestids inhabiting Gambia and Taiwan (Ortlepp, 1925, Myers and Kuntz, 1964). Compared to their otariid relatives, hookworms have been rarely described in phocids; however, the description of Uncinaria sp. in Southern elephant seals (Mirounga leonina) from Antarctica (Ramos et al., 2013) highlights the extreme adaptability of some hookworm species. The human hookworm, Ancylostoma duodenale, has been found in low numbers (n = 7) in spotted hyenas (Crocuta crocuta) in Ethiopia (Graber and Blanc, 1979), and in other study in Kenya up to 90% of hyenas harbored an Ancylostoma sp. (Engh et al., 2003). The Malay civet (Viverra tangalunga) in Borneo harbors the zoonotic hookworm, Ancylostoma ceylanicum, in low prevalence (3%); however, they are more commonly infected (33% prevalence) with a different Ancylostoma sp. (Colon and Patton, 2012).

Table 7.

Members of the Mephtididae, Herpestidae, Phocidae, Hyenidae and Viverridae families on which hookworms have been described and the corresponding references.

| Host Species | Hookworm species | References |

|---|---|---|

| Palawan stink badger (Mydaus marchei) | Arthrostoma vampira | Schmidt and Kuntz, 1968 |

| Andean hog-nosed skunk (Conepatus chinga) | Ancylostoma conepati | Ibáñez, 1968 |

| Skunk (Mephitis nigra) | Arthrocephalus lotoris | Dikmans and Goldberg 1949 |

| Gambian mongoose (Mungos gambianus) | Arthrocephalus gambiensi | Ortlepp 1925 |

| Crab-eating mongoose (Herpestes urva) | Arthrocephalus gambiensi | Myers and Kuntz 1964 |

| Small Asian mongoose (Herpestes javanicus) | Uncinaria sp. | Ishibashi et al., 2010 |

| Southern elephant seal (Mirounga leonina) | Uncinaria sp | Ramos et al., 2013 |

| Mediterranean monk seal (Monachus monachus) | Uncinaria sp | Nadler et al., 2013 |

| Malay civet (Viverra tangalunga) | Ancylostoma ceylanicum | Colon and Patton 2012 |

| Ancylostoma sp. | Colon and Patton 2012 | |

| Spotted hyena (Crocuta crocuta) | Ancylostoma duodenale | Graber and Blanc 1979 |

| Ancylostoma spp | Engh et al., 2003 |

4.2. Arctiodactyla

4.2.1. Bovidae

Hookworm infections of bovines are dominated by the genera Agriostomum, Bunostomum and Gaigeria (Table 8). All Agriostomum species have been described in South African bovids such as blue wildebeest (Connochaetes taurinus) and kudu (Tragelaphus strepsiceros) (Van Wyk and Boomker, 2011). The cattle hookworm Bunostomum phlebotomum has been described in endangered European bison (Bison bonasus) in Poland (Karbowiak et al., 2014); however, numerous African bovines, including the African buffalo (Syncerus caffer) harbor hookworms of the Bunostomum genus although the definitive species have not been fully described (Ocaido et al., 2004, Phiri et al., 2011). Sheep hookworms also affect wild ruminants; Bunostomum trigonocephalum infects European wild bovids (Pérez et al., 1996, Karbowiak et al., 2014) and Gaigeria pachyscelis infects the cecum and colon of several South African bovines (Anderson, 1978, Horak et al., 1983).

Table 8.

Hookworm species described in members of the Bovidae family with corresponding references.

| Host Species | Hookworm species | References |

|---|---|---|

| Kudu (Tragelaphus strepsiceros) | Agriostomum gorgonis | Boomker et al., 1989a, Boomker et al., 1989b, Van Wyk and Boomker, 2011 |

| African buffalo (Syncerus caffer) | Bunostomum sp. | Ocaido et al., 2004, Senyael et al., 2013 |

| Blue wildebeest (Connochaetes taurinus) | Agriostomum gorgonis | Van Wyk and Boomker 2011 |

| Gaigeria pachyscelis | Horak et al., 1983 | |

| Common tsessebe (Damaliscus lunatus) | Agriostomum cursoni | Mönnig 1932 |

| Common reedbuck (Redunca arundinum) | Gaigeria sp. | Boomker et al., 1989a, Boomker et al., 1989b |

| Gemsbok (Oryx gazella) | Agriostomum monnigi | Ogden 1965 |

| Agriostomum equidentatus | Fourie et al., 1991 | |

| European bison (Bison bonasus) | Bunostomum phlebotomum | Karbowiak et al., 2014 |

| Bunostomum trigonocephalum | Karbowiak et al., 2014 | |

| Nyala (Tragelaphus angasii) | Gaigeria pachyscelis | Boomker et al., 1991 |

| Impala (Aepyceros melampus) | Gaigeria pachyscelis | Anderson 1978 |

| Bunostomum sp. | Ocaido et al., 2004 | |

| Iberian ibex (Capra pyrenaica) | Bunostomum trigonocephalum | Pérez et al., 1996 |

| Springbok (Antidorcas marsupialis) | Agriostomum equidentatus | Young et al., 1973, Horak et al., 1982, De Villiers et al., 1985 |

| Lechwe (Kobus leche) | Bunostomum sp. | Phiri et al., 2011 |

| Waterbuck (Kobus ellipsiprymnus) | Bunostomum sp. | Ocaido et al., 2004 |

4.2.2. Suidae and Tayassuidae

The domestic pig hookworm, Globocephalus urosubulatus, has been described in wild boars, feral domestic pigs-wild boar hybrids (Sus scrofa) and the central America wild pig, pecari (Pecari tajacu) (Table 9) (Coombs and Springer, 1974, Romero-castañón et al., 2008, Senlik et al., 2011). G. urosubulatus dominates in the Americas and Europe, and has been sporadically reported in eastern Asia; however, in Japan and Korea wild boars are usually infected with G. samoensis and G. longimucronatus (Kagei et al., 1984, Sato et al., 2008). In Africa, the bushpig (Potamochoerus porcus) harbors a different species of hookworm, G. versteri (Van Wyk and Boomker, 2011).

Table 9.

Hookworm species described in members of the Bovidae family with corresponding references.

| Host Species | Hookworm species | References |

|---|---|---|

| Wild Boar (Sus scrofa) | Globocephalus urosubulatus | Coombs and Springer, 1974, Eslami and Farsad-Hamdi, 1992, Rajković-Janje et al., 2002, Fernandez-De-Mera et al., 2004, Foata et al., 2005, Foata et al., 2006, Nanev et al., 2007, Senlik et al., 2011, Gasso et al., 2015 |

| Globocephalus samoensis | Kagei et al., 1984, Sato et al., 2008, Ahn et al., 2015 | |

| Globocephalus longimucronatus | Kagei et al., 1984, Sato et al., 2008 | |

| Bushpig (Potamochoerus porcus) | Globocephalus versteri | Van Wyk and Boomker 2011 |

| Pecari (Pecari tajacu) | Globocephalus urosubulatus | Romero-castañón et al., 2008 |

4.2.3. Cervidae and Giraffidae

The cattle and sheep hookworms B. phlebotomum, B. trigonocephalum are the most common Ancylostomids of deer in Europe and Asia (Table 10). In North America, however, Monodontus lousianensis has been found in the intestines of white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) (Chitwood and Jordan, 1965). Monodontella giraffae has been found in the bile duct of a captive giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis) (Ming et al., 2010) and in all (n = 7) necropsied giraffes in one study in Namibia (Bertelsen et al., 2009).

Table 10.

Hookworm species described in members of the Cervidae and Giraffidae families with corresponding references.

| Host Species | Hookworm species | References |

|---|---|---|

| Fallow deer (Dama dama) | Bunostomum phlebotomum | Omeragić et al., 2011 |

| Bunostomum trigonocephalum | Páv et al., 1975 | |

| Red deer (Cervus elaphus) | Bunostomum trigonocephalum | Zalewska-Schönthaler and Szpakiewicz 1986 |

| Roe deer (Capreolus capreolus) | Bunostomum trigonocephalum | Demiaszkiewicz et al., 2002 |

| White-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) | Monodontus lousianensis | Chitwood and Jordan 1965 |

| Reeves's muntjac (Muntiacus reevesi) | Bunostomum phlebotomum | Myers and Kuntz 1964 |

| Giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis) | Monodontella giraffae | Bertelsen et al., 2009, Ming et al., 2010 |

4.3. Primates

Primates within the Cercopithecidae, Hominidae and Loricidae families are affected by hookworms, and, as in people, Necator and Ancylostoma are the most important genera in non-human primates (Table 11). Necator gorillae has been described in western mountain gorillas (Gorilla gorilla) in the democratic Republic of Congo (Noda and Yamada, 1964), and in humans in close contact with gorillas in the Central African Republic (Kalousová et al., 2016). Additionally, the human hookworm Necator americanus, has been found in gorillas and chimpanzees in areas where this parasite is common among people (Hasegawa et al., 2014). In Cameroon, Ancylostoma sp. nematodes were common in endemic cercopithecids sold as bushmeat in a local market (Pourrut et al., 2011). In the endangered lion-tailed macaque (Macaca silenus), groups close to human populations have 40–70% prevalence of Ancylostoma sp while groups in areas with no human settlements had 0% prevalence (Hussain et al., 2013).

Table 11.

Primate species infected with hookworms with corresponding references.

| Host Species | Hookworm species | References |

|---|---|---|

| Lion-tailed macaques (Macaca silenus) | Ancylostoma spp | Hussain et al., 2013 |

| Bunostomum sp. | Hussain et al., 2013 | |

| Moustached guenon (Cercopithecus cephus) | Ancylostoma spp | Pourrut et al., 2011 |

| Mona monkey (Cercopithecus mona) | Ancylostoma spp | Pourrut et al., 2011 |

| De Brazza's monkey (Cercopithecus neglectus) | Ancylostoma spp | Pourrut et al., 2011 |

| Greater spot-nosed monkey (Cercopithecus nictitans) | Ancylostoma spp | Pourrut et al., 2011 |

| Crested mona monkey (Cercopithecus pogonias) | Ancylostoma spp | Pourrut et al., 2011 |

| Agile mangabey (Cercocebus agilis) | Ancylostoma spp | Pourrut et al., 2011 |

| Mantled guereza (Colobus guereza) | Ancylostoma spp | Pourrut et al., 2011 |

| Gabon talapoin (Miopithecus ogoouensis) | Ancylostoma spp | Pourrut et al., 2011 |

| Brown woolly monkeys (Lagothrix lagothricha) | Ancylostoma sp | Michaud et al., 2003 |

| Vervet monkey (Chlorocebus pygerythrus) | Necator sp. | Gillespie et al., 2004 |

| Western lowland gorillas (Gorilla gorilla gorilla) | Necator americanus | Hasegawa et al., 2014 |

| Necator gorillae | Noda and Yamada 1964 | |

| Chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) | Necator americanus | Hasegawa et al., 2014 |

| Ancylostoma spp | Pourrut et al., 2011 | |

| Bald uakari (Cacajao calvus) | Necator americanus | Michaud et al., 2003 |

| Baboons (Papio hamadryas) | Necator sp | Howells et al., 2011 |

| Javan slow loris (Nycticebus javanicus) | Necator sp | Albers, 2014, Rode-Margono et al., 2015 |

Occasional grey literature (technical reports), describe hookworms as common in non-human primates; however, they do not report the genus or species, and therefore could not be incorporated into this review.

4.4. Rodentia

Hookworms have been sporadically described in rodents. Most studies have focused in the nematode species description and little is known about the prevalence and patterns of hookworm infection in this animal group. Monodontus is one of the most common hookworm genera in rodents in the Americas (Table 12). In Australia, the native water rat (Hydromys chrysogaster) harbors Uncinaria hydromydis (Smales and Cribb, 1997), and in Malaysia Cyclodontostomum purvisi infects several native murid species (Balasingam, 1963). In Africa, the greater cane rat (Thryonomys swinderianus) is infected by two species of the Acheilostoma genus, of which A. simpsoni is found in the gallbladder and bile ducts of 60% of animals (Kankam et al., 2009).

Table 12.

Rodent species infected with hookworms with corresponding references.

| Host Species | Hookworm species | References |

|---|---|---|

| Australian water rat (Hydromys chrysogaster) | Uncinaria hydromyidis | Beveridge, 1980, Smales and Cribb, 1997 |

| Long-tailed giant rat (Leopoldamys sabanus) | Cyclodontostomum purvisi | Balasingam 1963 |

| Müller's giant Sunda rat (Sundamys muelleri) | Cyclodontostomum purvisi | Balasingam 1963 |

| Bower's white-toothed rat (Berylmys bowersi) | Cyclodontostomum purvisi | Balasingam 1963 |

| Greater cane rat (Thryonomys swinderianus) | Acheilostoma simpsoni | Kankam et al., 2009 |

| Acheilostoma moucheti | Popova 1964 | |

| Cotton rat (Sigmodon hispidus) | Monodontus floridanus | McIntosh 1935 |

| Round-tailed muskrat (Neofiber alleni) | Monodontus floridanus | Forrester et al., 1987 |

| Red-rumped agouti (Dasyprocta leporina) | Monodontus aguiari | Travassos 1937 |

| Brazilian spiny rat (Mesomys sp) | Monodontus rarus | Travassos 1929 |

4.5. Perissodactyla

The knowledge of hookworm infections in this order is limited to parasite descriptions usually based on a few nematodes recovered from a single animal (Khalil, 1922b). Within the perissodactyla, hookworms have been found in tapirs (Tapitus sp.) (Travassos, 1937), and the black Rhinoceros (Rhinoceros bicornis) (Table 13) (Neveu-Lemaire, 1924).

Table 13.

Mammalian species in the Perissodactyla, Proboscidea, Pholidota, Afrosoricida and Scandentia orders affected by hookworms.

| Host Species | Hookworm species | References |

|---|---|---|

| South American tapir (Tapirus terrestris) | Monodontus nefastus | Travassos 1937 |

| Malayan tapir (Tapirus indicus) | Brachyclonus indicus | Khalil 1922b |

| Black Rhinoceros (Rhinoceros bicornis) | Grammocephalus intermedius | Neveu-Lemaire, 1924 |

| African elephant (Loxodonta africana) | Bunostomum brevispiculum | Monnig 1925 |

| Bunostomum hamatum | Monnig 1925 | |

| Grammocephalus clathratus | Allen et al., 1974, Obanda et al., 2011 | |

| Grammocephalus sp | Debbie and Clausen 1975 | |

| Asian elephant (Elephas maximus) | Grammocephalus hybridatus | Romboli et al., 1975 |

| Asian elephant (Elephas maximus) | Grammocephalus varedatus | Van Der Westhuysen, 1938 |

| Asian elephant (Elephas maximus) | Bathmostomum sangeri | Setasuban 1976 |

| Chinese pangolin (Manis pentadactyla) | Necator americanus | Cameron and Myers, 1960, Myers and Kuntz, 1964 |

| Indian pangolin (Manis crassicaudata) | Necator americanus | Mohapatra et al., 2015 |

| Greater hedgehog tenrec (Setifer setosus) | Uncinaria bauchoti | Chabaud et al., 1964 |

| Treeshrew (Tupaia sp) | Uncinaria olseni | Chabaud and Durette-Desset, 1974 |

4.6. Proboscidea

Elephants are the only living family within the proboscidea order. In this group, despite the low number of studies conducted, at least 3 species of hookworms have been described in the African elephant (Loxodonta Africana) and another 3 in the Asian elephant (Elephas maximus) (Table 13). In these animals, hookworms in the Grammocephalus genus inhabit the bile duct while those in the Bunostomum and Bathmostomum genera inhabit the small and large intestines (Monnig, 1925, Debbie and Clausen, 1975, Setasuban, 1976).

4.7. Pholidota

In Asia, pangolins (Manis sp) are infected with low intensities (less than 16 nematodes per host) of the human hookworm N. americanus (Table 13) (Cameron and Myers, 1960, Mohapatra et al., 2015).

4.8. Afrosoricida and Scandentia

In the Afrosoricida order the greater hedgehog tenrec (Setifer setosus) is the only species in which hookworms have been described (Uncinaria bauchoti) (Table 13) (Chabaud et al., 1964). In the Scandentia order the hookworm Uncinaria olseni was described in a treeshrew (Tupaia sp) (Table 13) (Chabaud and Durette-Desset, 1974).

5. The impact of hookworm infections on wildlife

All members of the Ancylostomatoidae family are hematophagous and have developed efficient systems to extract and digest their host blood (Hotez et al., 2016). Most hookworm species use their well-developed buccal capsules to attach to mucosal surfaces and cut-out pieces of the tissue to produce “wounds” that bleed, in part because of the secretion of several anticoagulant proteins (Periago and Bethony, 2012, Hotez et al., 2016). Since most hookworms live in the small intestine, this process creates a perfect environment for chronic blood loss, secondary bacterial infections and significant inflammation in the mucosae, impairing digestion and absorption (Seguel et al., 2017). Therefore, the main adverse effects of hookworms recorded in humans, domestic animals and wildlife species are anemia, retarded growth, secondary bacteremia and mortality (Traversa, 2012, Hotez et al., 2016, Seguel et al., 2017). The following section summarizes available evidence of such effects on wildlife hosts and explores potential drivers of those effects on wildlife populations.

5.1. Pathologic effects

5.1.1. Anemia

Anemia is rarely documented in wildlife species infected with hookworms, because few studies include assessment of blood values. In wolves, A. caninum infection has been associated with iron deficiency anemia in pups (Kazacos and Dougherty, 1979). In Florida, USA, a young cougar was found markedly anemic due to A. pluridentatum infection (Dunbar et al., 1994). In Michigan, USA, the reintroduced American martens (Martes americana) infected with hookworms (not species specified), were more likely to have anemia (Spriggs et al., 2016). The pups of Northern fur seals, California sea lions (Acevedo-Whitehouse et al., 2006), New Zealand sea lions (Acevedo-Whitehouse et al., 2009), Australian sea lions (Marcus et al., 2015b) and South American fur seals (Seguel et al., 2017), present with mild to severe anemia related to Uncinaria sp. infection. Hookworm-induced anemia is markedly regenerative in Australian sea lions (Marcus et al., 2015b). In New Zealand and California sea lions, a single nuclear polymorphism (SNP) is linked with the degree of hookworm-associated anemia (Acevedo-Whitehouse et al., 2006, Acevedo-Whitehouse et al., 2009).

5.1.2. Retarded growth

The only hookworm-infected wildlife species in which retarded growth has been accurately measured are Northern fur seals (Delong et al., 2009), New Zealand sea lions (Chilvers et al., 2009) and South American fur seals (Seguel et al., 2017). In Australian sea lions, although pups from rookeries with lower hookworm prevalence had higher body mass index (Marcus et al., 2014a, Marcus et al., 2014b), controlled deworming experiments did not find significant difference between treated and hookworm-infected animals (Marcus et al., 2015a). The scarce literature on the effect of hookworms on wildlife host growth rates is probably related to logistic limitations to perform experimental studies in most free-ranging populations, an approach that facilitates measurement and comparison of growth rates in infected and uninfected animals. Additionally, hookworm infection is a primarily neonatal disease in pinnipeds, because infective stage 3 larvae only develop into adults when ingested by a pup with its mother's milk (Lyons et al., 2011a, Lyons et al., 2011b Seguel et al., 2017), therefore, retarded growth is a significant component of hookworm disease in these mammalian species (Chilvers et al., 2009, Delong et al., 2009 Seguel et al., 2017).

5.1.3. Tissue damage and inflammation

Probably most hookworm species cause some level of tissue damage as an unavoidable consequence of parasite feeding. This effect, however, along with inflammation, has been rarely documented in wildlife species, probably because most studies only assess these changes through gross examination of carcasses, where subtle lesions can be easily missed (Seguel et al., 2017).

When hookworms feed on the intestinal mucosa they leave small 1–2 mm erosions on the mucosal surface that sometimes can be observed grossly, as is the case of Coyote pups infected with low numbers of A. caninum (Pence et al., 1988), California sea lions, South American fur seals, New Zealand sea lions, and Northern fur seals infected with Uncinaria sp hookworms (Spraker et al., 2007, Lyons et al., 2011a, Lyons et al., 2011b, Seguel et al., 2017). The chronic bleeding of these intestinal wounds and accompanying inflammation elicited by the disruption of the mucosal barrier lead to different degrees of hemorrhagic enteritis, a common consequence of A. caninum infections in coyotes (Radomsky, 1989), A. pluridentatum in young cougars, Uncinaria sp. in otariids and A. lotoris in raccoons. However, in raccoons these lesions have only been documented with experimental infections leading to burdens not observed in the wild (∼1500 nematodes) (Balasingam, 1964).

The mentioned patterns of lesions in wildlife are similar to that reported in domestic animal and human hookworm infections (Periago and Bethony, 2012, Traversa, 2012). However, among the high diversity of hookworm species infecting wildlife, there are particular lesion patterns only described in wild host species. These are the cases of peritoneal penetration by Uncinaria sp. in pinnipeds, hookworm submucosal infections in large cats, and bile and pancreatic duct hookworm infections of badgers, giraffes and elephants. Complete intestinal penetration by adult hookworms (Uncinaria sp.), has been observed in a significant proportion (from 12.5 to 60% of pups found dead) of California sea lions (Spraker et al., 2007), Northern fur seals (Lyons et al., 2011b) and South American fur seals (Seguel et al., 2017), leading to peritonitis, septicemia and death. In large felines, the hookworms Galoncus trudentatus and Galoncus perniciosus, which infect leopards (Panthera pardus) and tigers (Pant hera tigris), respectively (Khalil, 1922a, Kalaivanan et al., 2015) have the particularity of feeding in the intestinal submucosa and muscularis where they form hemorrhagic nodules, which, once infected with enteric bacteria, can lead to sepsis and death (Khalil, 1922a, Kalaivanan et al., 2015). Tetragomphius melis and Tetragomphius arctonycis, which infect the Japanese (Meles anakuma) and Hog (Arctonyx collaris) badgers respectively, cause significant inflammation, fibrosis, and “mass-like” lesions in the pancreatic duct (Jansen, 1968, Ashizawa et al., 1976, Matsuda and Yamamoto, 2015). Despite significant tissue alterations caused by these mustelid parasites, mortality due to severe infection has not been reported, and the effect of these hookworms at the population level is unknown. Monodontella giraffae causes cholangitis and peribiliary fibrosis in giraffes (Bertelsen et al., 2009), and in elephants Grammocephalus spp cause severe eosinophilic cholangitis (Allen et al., 1974, Debbie and Clausen, 1975, Obanda et al., 2011).

5.1.4. Mortality

Mortality of wild animals due to hookworm infection is in most cases the final outcome of chronic anemia, retarded growth, tissue damage, and secondary bacterial infections. Mortality has been recorded most commonly in canids, felids, and otariids. In southern Texas coyote populations, the effect of A. caninum has been tested by experimental infection, where infective doses of over 300 stage 3 larvae/Kg of A. caninum were lethal in pups (Radomsky, 1989), and resulted in parasitic loads similar to those reported in naturally infected juvenile coyotes (range 50–150 nematodes) (Thornton and Reardon, 1974), suggesting a potential role of A. caninum in pup mortality and limiting the expansion of coyote populations. Similarly, in the same region, grey foxes (Urocyon cinereoargenteus) were infected with high burdens of A. caninum, suggesting some level of population mortality ((Miller and Harkema, 1968). In wolves, A. caninum and U. stenocephala have been associated with pup mortality; however, detailed assessment of parasite effects on mortality through controlled studies have not been performed (Kazacos and Dougherty, 1979, Kreeger et al., 1990, Guberti et al., 1993). In Europe, some level of population mortality has been assumed in peri-urban red foxes infected with high burdens of Uncinaria stenocephala (Willingham et al., 1996). In Asia, Arthrostoma miyazakiense can cause sporadic mortality in raccoon dogs (Sato et al., 2006, Shin et al., 2007). In felines, beside the highly pathogenic Galoncus spp. affecting tigers and leopards, probably A. caninum and A. pluridentatum cause some level of mortality in bobcats and cougars in the southeastern United States (Mitchell and Beasom, 1974, Forrester et al., 1985, Dunbar et al., 1994). In otariids, Uncinaria spp. can cause up to 70% mortality in some colonies of California sea lions (Spraker et al., 2007). In other species, such as New Zealand sea lions, northern fur seal, Australian sea lions and South American fur seals, hookworms cause between 15 and 50% of total pup mortality (Castinel et al., 2007a, Lyons et al., 2011a, Seguel et al., 2013, Marcus et al., 2014a). In other mammalian groups, reports of hookworms causing mortality are sporadic, as in the case of Uncinaria sp nematodes causing the death of a brown bear pup in Turkey (Kilinc et al., 2015), and the role of Grammocephalus hybridatus in the death of several young Asian elephants transported to a zoo (Romboli et al., 1975). Hookworms were suspected to be the cause of death of a maroon langur (Presbytis rubicunda) in Asia, but the hookworm genus or species causing death was unknown (Hilser et al., 2014).

5.2. Drivers of hookworm pathologic effects

According to the data retrieved from the reviewed literature and the regression models performed, population level hookworm prevalence is the most significant predictor of the pathogenic effect of hookworms. The role of infection intensity on the severity of hookworm disease is reported in several studies; however, it was not a significant predictor in regression models. This could be due to natural study bias, reporting pathologic effects, as many of them provide good descriptions of mean infection intensity but little or no assessment of tissue damage and other pathologic effects.

There is a wide range of variation in prevalence and mean intensity of hookworm infections among wildlife populations; however, a common pattern of regional and local differences in prevalence is noted, usually attributable to contrasts in local temperature and soil humidity, which are critical factors for survival of hookworm infective larvae in the soil (Ryan and Sc, 1976, Yabsley and Noblet, 1999, Criado-Fornelio et al., 2000, Gompper et al., 2003, Dybing et al., 2013). Additionally, hookworm species can differ in their resistance to environmental conditions, creating regional patterns of infection. Such is the case of canine hookworms since A. caninum is found in higher mean intensities in areas with mild climate like southeastern United States (Miller and Harkema, 1968, Mitchell and Beasom, 1974, Thornton and Reardon, 1974, Schitoskey, 1980, Custer and Pence, 1981) while U. stenocephala is usually reported in higher prevalence and intensity in canids inhabiting temperate or circumboreal areas (Willingham et al., 1996, Craig and Craig, 2005, Reperant et al., 2007, Stuart et al., 2013). An additional factor associated with changes in prevalence and mean intensities is the spatial density of host animals. Higher population density is usually associated with higher prevalence, as this increases the number of infective larvae in the soil (Henke et al., 2002, Lyons et al., 2011a Seguel et al., 2017). Beside environmental contrasts, intra-host dynamics of hookworm infection are probably important in explaining patterns of prevalence and burden. For instance, canid, felid, ursid and procyonid hookworms establish chronic infections, where significant immunity apparently does not occur, indicating that older animals have higher chances to be in contact with infective stages through their life and harbor higher numbers of parasites (Worley et al., 1976, Yabsley and Noblet, 1999, Kresta et al., 2009, Liccioli et al., 2012). In some canine populations, however, young animals are the most severely affected with Ancylostoma species, probably reflecting the role of lactogenic transmission in the disease dynamics (Custer and Pence, 1981). In the case of pinnipeds, infective larvae reach pups only through their mothers' milk and adult hookworms are cleared from the pup's intestine 2–6 months after initial infection. This results on a short life span for adult hookworms in pinnipeds and markedly seasonal prevalence (Lyons et al., 2011a, Marcus et al., 2014a, Seguel et al., 2017).

An additional element incorporated in the final model to explain pathologic effect was hookworm length, although the effect was not significant. There is evidence across the reviewed literature suggesting that larger hookworms are potentially more pathogenic, as the case of Grammocephalus spp in elephants, which are approximately 35 mm long (Obanda et al., 2011). Something similar occurs with pinniped Uncinaria spp., which are larger than their terrestrial relatives (Ramos et al., 2013, Nadler et al., 2013). For other groups of large hookworms, however, such as those within the Bunostominae subfamily, there is little evidence of pathologic effects in their wild ruminant host, although some of those species, such as Bunostomum phlebotomum, Bunostomum trigonocephalum and Gaigeria pachyscelis, are known to cause anemia, hemorrhagic enteritis and death in domestic ruminants (Hart and Wagner, 1971).

The three discussed drivers of hookworm pathogenic effects; prevalence, burden and hookworm length can be considered indicators of hookworm biomass within a population. Since the pathogenic effects described are related to the extraction of host resources by the parasite, it can be inferred that any factor that increases the hookworm biomass within a population will also increase the detrimental effect of these parasites in this group.

6. Discussion and conclusions

There are numerous hookworm species described in a wide range of wild mammals. Carnivores are over represented in the literature, and therefore most of the negative effects of hookworm infection have been described in this group. This does not necessarily imply that hookworms are important pathogens only in carnivores; for instance, there is enough evidence to infer that hookworm infections are significant disease agents in ruminants and primates. These groups, however, are less represented and probably neglected regarding the study of hookworms. This could be in part due to the fact that most wild ruminants and primates live in areas of the planet traditionally underrepresented in terms of parasitology research (Falagas et al., 2006).

Several studies have highlighted the potential of carnivore hookworms to infect multiple species, including humans (Reviewed in Travesa, 2012). The literature in wildlife species support these observations, as several human and domestic animal hookworms infect more than 10 different wildlife hosts in a wide range of taxonomic groups. In most cases, these hookworm species are capable of establishing complete life cycles and harm in their “non-native” hosts. This highlights the significance of domestic animal-human-wildlife interface for this disease and the potential for spillover and spillback processes playing an important role in the maintenance of high hookworm burdens in some areas.

A comprehensive understanding of the drivers of hookworm deleterious effects on wildlife hosts is complicated, given the likely strong bias towards the reporting only positive findings. In this sense, the literature available describes in which species and locations hookworms have an effect, but is insufficient to understand why these effects are observed in some species or populations and not in others. Evidence in the literature, however, indicates that hookworm biomass in a population and the host and environmental factors affecting biomass (e.g. environmental temperature, host density), are important in determining the outcome of hookworm infections. It is, however, likely that the importance of these elements change across populations. The role in disease dynamics of other hookworm-related traits, such as genetic variation and virulence factors, is less clear, and studies addressing these aspects are necessary to fully understand drivers of hookworm disease in wildlife.

The hookworms' effects on some populations of canines, felines and eared seals are of special concern, as several species in these families are endangered. Additionally, in all these groups, the dynamics of hookworm infections, and therefore the pathogenic effects, are linked to the density of susceptible animals and environmental variables such as humidity and temperature. These characteristics of wildlife hookworm infections, plus the generalist nature of these nematodes, creates a dynamic scenario where human-related disturbances of wildlife populations and climate change may potentially affect the dynamics and effects of hookworm infections in wildlife.

In the era of molecular pathogenesis, the study of hookworm disease is still very rudimentary in wildlife hosts, despite the fact that these pathogens impact wildlife, domestic animal, and human, health and wildlife conservation. The use of approaches other than opportunistic collection of carcasses, especially experimental and molecular when possible, could substantially improve our understanding of the impact and drivers of hookworm disease in wildlife populations.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Morris Animal Foundation [grant number D16ZO-413].

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijppaw.2017.03.007.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data related to this article:

References

- Acevedo-Whitehouse K., Petetti L., Duignan P., Castinel A. Hookworm infection, anaemia and genetic variability of the New Zealand sea lion. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2009;276:3523–3529. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2009.1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acevedo-Whitehouse K., Spraker T.R., Lyons E., Melin S.R., Gulland F., Delong R.L., Amos W. Contrasting effects of heterozygosity on survival and hookworm resistance in California sea lion pups. Mol. Ecol. 2006;15:1973–1982. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2006.02903.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguirre A., Angerbjörnph A., Tannerfeldtph M., Mörnerd T. Health evaluation of arctic fox (Alopex lagopus) cubs in Sweden health evaluation of arctic fox (Alopex lagopus) J. Zoo. Wildl. Med. 2000;31:36–40. doi: 10.1638/1042-7260(2000)031[0036:HEOAFA]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn K.S., Ahn A.J., Kim T.H., Suh G.H., Joo K.W., Shin S.S. Identification and prevalence of Globocephalus samoensis (Nematoda: Ancylostomatidae) among wild boars (Sus scrofa coreanus) from Southwestern regions of Korea. Korean J. Parasitol. 2015;53:611–618. doi: 10.3347/kjp.2015.53.5.611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Sabi M.N.S., Chriel M., Jensen T.H., Enemark H.L. Endoparasites of the raccoon dog (Nyctereutes procyonoides) and the red fox (Vulpes vulpes) in Denmark 2009-2012-A comparative study. Int. J. Parasitol. Parasites Wildl. 2013;2:144–151. doi: 10.1016/j.ijppaw.2013.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alagaili A.N., Mohammed O.B., Omer S.A. Gastrointestinal parasites and their prevalence in the Arabian red fox (Vulpes vulpes arabica) from the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Vet. Parasitol. 2011;180:336–339. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2011.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alarcón Ú. Fac. Ciencias Vet. Univ. Austral Chile; 2005. Estudio taxonómico de la fauna parasitaria del tracto gastrointestinal de zorro gris (Pseudalopex griseus, Gray 1837), en la XII región de Magallanes y Antártica Chilena; pp. 1–41. Undergrad Thesis. [Google Scholar]

- Albers M. Assessment of habitat, population density and parasites of the Javan slow loris (Nycticebus javanicus) in Ciapaganti, Garut-West Java. Canopy. 2014;14:22–24. [Google Scholar]

- Allen K., Follis T., Kistner T. Occurrence of Grammocephalus clathratus (Baird, 1868 ) Railliet and Henry, 1910 ( Nematoda: Ancylostomatidae ), in an African elephant imported into the United States. J. Parasitol. 1974;60:952. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ameel D. Parasites of the coyote in Kansas (1903-) Trans. Kans. Acad. Sci. 1955;58:208–210. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson I. Rand Afrikaans University; 1978. Parasitological Studies on Impala (Aepyceros melampus) in Natal. PhD Thesis. 139 pp. [Google Scholar]

- Asakawa M., Mano T., Gardner S.L. First record of Ancylostoma malayanum (Alessandrini, 1905) from brown bears (Ursus arctos) Comp. Parasitol. 2006;73:282–284. [Google Scholar]

- Ashizawa H., Murakami T., Usui M., Nosaka D., Tateyama S., Kugi G. Pathological findings of pancreas infected with Tetragomphius sp. I. Characteristic changes in the pancreatic duct of the Japanese badgers. Bull Fac AgricMiyazaki Univ. 1976;23:371–381. [Google Scholar]

- Balasingam E. Redescription of Cyclodontostomum purvisi Adams, 1933, a hookworm parasite of Malayan giant rats. Can. J. Zool. 1963;41:1237–1239. [Google Scholar]

- Balasingam E. On the pathology of Placoconus lotoris infections in raccoons (Procyon lotor) l. Can. J. Zool. 1964;42:903–905. [Google Scholar]

- Bartsch S.M., Hotez P.J., Asti L., Zapf K.M., Bottazzi E., Diemert D.J., Lee B.Y. The global Economic and health burden of human hookworm infection. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2016;10(9):e0004922. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beldomenico P.M., Kinsella J.M., Uhart M.M., Gutierrez G.L., Pereira J., del Valle Ferreyra H., Marull C.A. Helminths of Geoffroy's cat, Oncifelis geoffroyi Stefañski (Carnivora, Felidae) from the Monte desert, central Argentina. Acta Parasitol. 2005;50:263–266. [Google Scholar]

- Berón-Vera B., Crespo E.A., Raga J.A., Pedraza S.N. Uncinaria hamiltoni (Nematoda: Ancylostomatidae) in South american sea lions, Otaria flavescens, from northern Patagonia, Argentina. J. Parasitol. 2004;90:860–863. doi: 10.1645/GE-182R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertelsen M.F., Østergaard K., Monrad J., Brøndum E.T., Baandrup U. Monodontella giraffae infection in wild-caught southern giraffes (Giraffa camelopardalis giraffa) J. Wildl. Dis. 2009;45:1227–1230. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-45.4.1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beveridge I. Uncinaria hydromyides (Ancylostomatidae) from the Australian water rat, hydromys chrysogaster. J. Parasitol. 1980;66:1027–1031. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjork K.E., Averbeck G.A., Stromberg B.E., Ph D. Parasites and parasite stages of free-ranging wild lions (Panthera leo) of northern Tanzania. J. Zoo. Wildl. Med. 2000;31:56–61. doi: 10.1638/1042-7260(2000)031[0056:PAPSOF]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boomker J., Horak I., Vos V. de. Parasites of South African wildlife. IV. Helminths of kudu, Tragelaphus strepsiceros, in the Kruger National Park. Onderstepoort J. Vet. Res. 1989;50:205–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boomker J., Horak I.G., Flamand J.R. Parasites of South African wildlife. XII. Helminths of Nyala, Tragelaphus angasii, in natal. Onderstepoort J. Vet. Res. 1991;58:275–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boomker J., Horak I.G., Flamand J.R.B., Keep M.E. Parasites of South African wildlife. III. Helminths of common reedbuck, Redunca arundinum, in Natal. Onderstepoort J. Vet. Res. 1989;56:51–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borecka A., Gawor J., Zieba F. A survey of intestinal helminths in wild carnivores from the Tatra National Park, southern Poland. Ann. Parasitol. 2013;59:169–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridger K.E., Baggs E.M., Finney-Crawley J. Endoparasites of the coyote (Canis latrans), a recent migrant to insular newfoundland. J. Wildl. Dis. 2009;45:1221–1226. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-45.4.1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buechner H. Helminth parasites of the gray fox. J. Mammal. 1944;25:185–188. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron T. Studies on the Endoparasitic fauna of Trinidad. III. Some parasites of Trinidad carnivores. Can. J. Res. 1936;14:24–27. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron T.W.M., Myers B.J. Manistrongylus Meyeri (Travassos, 1937) gen. Nov., and necator americanus from the pangolin. Can. J. Zool. 1960;38:781–786. [Google Scholar]

- Castinel A., Duignan P.J., Pomroy W.E., Lyons E.T., Nadler S.A., Dailey M.D., Wilkinson I.S., Chilvers B.L. First report and characterization of adult Uncinaria spp. in New Zealand sea lion (Phocarctos hookeri) pups from the Auckland Islands, New Zealand. Parasitol. Res. 2006;98:304–309. doi: 10.1007/s00436-005-0069-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castinel A., Duignan P.J., Lyons E.T. Epidemiology of hookworm (Uncinaria spp.) infection in New Zealand (Hooker's) sea lion (Phocarctos hookeri) pups on Enderby Island, Auckland Islands ( New Zealand ) during the breeding seasons from 1999/2000 to 2004/2005. Parasitol. Res. 2007;101:53–62. doi: 10.1007/s00436-006-0453-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castinel A., Duignan P.J., Pomroy W.E., López-Villalobos N., Gibbs N.J., Chilvers B.L., Wilkinson I.S. Neonatal mortality in New Zealand sea lions (Phocarctos hookeri) at Sandy Bay, Enderby Island, Auckland Islands from 1998 to 2005. J. Wildl. Dis. 2007;43:461–474. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-43.3.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalano S., Lejeune M., Tizzani P., Verocai G.G., Schwantje H., Nelson C., Duignan P.J. Helminths of grizzly bears (Ursus arctos) and american black bears (Ursus americanus) in Alberta and British Columbia, Canada. Can. J. Zool. 2015;93:765–772. [Google Scholar]

- Catalano S., Lejeune M., van Paridon B., Pagan C.A., Wasmuth J.D., Tizzani P., Nadler S.A. Morphological variability and molecular identification of Uncinaria spp. (Nematoda: Ancylostomatidae) from grizzly and black bears: new species or Phenotypic Plasticity? J. Parasitol. 2015;101:182–192. doi: 10.1645/14-621.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerbo a. R., Manfredi M.T., Bregoli M., Milone N.F., Cova M. Wild carnivores as source of zoonotic helminths in north-eastern Italy. Helminthologia. 2008;45:13–19. [Google Scholar]

- Chabaud A.G., Brygoo E.R., Tchéprakoff R. Nématodes parasites d'insectivores malgaches. Bull. Mus. Natn. Hist. Not. 1964;36:245–261. [Google Scholar]

- Chabaud A.G., Durette-Desset M. Uncinaria (Megadeirides) olseni n. sp., Nematode with archaical morphological characters, parasite of a Tupaia from Borneo. A. Parasitol. Hum. Comp. 1974;50:789–793. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chilvers B.L., Duignan P.J., Robertson B.C., Castinel A., Wilkinson I.S. Effects of hookworms (Uncinaria sp.) on the early growth and survival of New Zealand sea lion (Phocarctos hookeri) pups. Pol. Biol. 2009;32:295–302. [Google Scholar]

- Ching H.L., Leighton B.J., Stephen C. Intestinal parasites of raccoons (Procyon lotor) from southwest British Columbia. Can. J. Vet. Res. 2000;64:107–111. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chitwood M.B., Jordan H.E. Monodontus louisianensis sp. n. (Nematoda: Ancylostomatidae) a hookworm from the white-tailed deer, Odocoileus virginianus (Zimmermann), and a key to the species of Monodontus. J. Parasitol. 1965;51:942–944. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choquette L.P., Gibson G.G., Pearson A.M. Helminths of the grizzly bear, Ursus arctos L., in northern Canada. Can. J. Zool. 1969;47:167–170. doi: 10.1139/z69-038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole R., Shoop W. Helminths of the raccoon ( Procyon lotor ) in western Kentucky. J. Parasitol. 1987;73:762–768. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colon C.P., Patton S. Parasites of civets (Mammalia, Viverridae) in Sabah, Borneo: a coprological survey. Malay. Nat. J. 2012;64:87–94. [Google Scholar]

- Conti J. a. Helminths of foxes and coyotes in Florida. Proc. Helm. Soc. Wash. 1984;51:365–367. [Google Scholar]

- Coombs D.W., Springer M.D. Parasites of feral pig x European wild boar hybrids in southern Texas. J. Wildl. Dis. 1974;10:436–441. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-10.4.436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig H.L., Craig P.S. Helminth parasites of wolves (Canis lupus): a species list and an analysis of published prevalence studies in Nearctic and Palaearctic populations. J. Helminthol. 2005;79:95–103. doi: 10.1079/joh2005282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Criado-Fornelio A., Gutierrez-Garcia L., Rodriguez-Caabeiro F., Reus-Garcia E., Roldan-Soriano M.A., Diaz-Sanchez M.A. A parasitological survey of wild red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) from the province of Guadalajara, Spain. Vet. Parasitol. 2000;92:245–251. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4017(00)00329-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crum J.M., Nettles V.F., Davidson W.R. Studies on endoparasites of the black bear (Ursus americanus) in the southeastern United States. J. Wildl. Dis. 1978;14:178–186. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-14.2.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Custer J.W., Pence D.B. Ecological analyses of helminth populations of wild canids from the gulf costal prairies of Texas and Louisiana. J. Parasitol. 1981;67:289–307. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/18.5.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalimi A., Sattari A., Motamedi G. A study on intestinal helminthes of dogs, foxes and jackals in the western part of Iran. Vet. Parasitol. 2006;142:129–133. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Villiers I.L., Liversidge R., Reinecke R.K. Arthropods and helminths in springbok (Antidorcas marsupialis) at Benfontein, Kimberley. Onderstepoort J. Vet. Res. 1985;52:1–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debbie J.G., Clausen B. Some hematological values of free-ranging African elephants. J. Wildl. Dis. 1975;11:79–82. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-11.1.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delong R.L., Orr A.J., Jenkinson R.S., Lyons E.T. Treatment of northern fur seal (Callorhinus ursinus) pups with ivermectin reduces hookworm-induced mortality. Mar. Mammal. Sci. 2009;25:944–948. [Google Scholar]

- Demiaszkiewicz A.W., Drozdz J., Lachowicz J. Exchange of gastrointestinal nematodes between roe and red deer (Cervidae) and European bison (Bovidae) in the Bieszczady Mountains (Carpathians, Poland) A. Parasitol. 2002;47:314–317. [Google Scholar]

- Dikmans G., Goldberg A. A note on Arthrocephalus lotoris (Schwartz, 1925) Chandler, 1942 and other roundworm parasites of the skunk, Mephitis nigra. Proc. Helminthol. Soc. Wash. 1949;16:9–11. [Google Scholar]

- Dos Santos K., Catenacci L., Pestelli M., Takahira R., Lopes R., Da Silva R. First report of Ancylostoma buckleyi le Roux and Biocca, 1957 (Nematoda: Ancylostomastidae) infecting Cerdocyon thous linnaeus, 1766 (Mammalia: Canidae) Braz. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. 2003;12:179–181. [Google Scholar]

- Duarte M. Univ. Estadual Paul; 2016. Estudos parasitológicos em cães domésticos errantes e carnívoros selvagens generalistas no Parque Nacional do Iguaçu, Foz do Iguaçu. Master Thesis. 102 pp. [Google Scholar]

- Dunbar M.R., McLaughlin G.S., Murphy D.M., Cunningham M.W. Pathogenicity of the hookworm, Ancylostoma pluridentatum, in a Florida panther (Felis concolor coryi) kitten. J. Wildl. Dis. 1994;30:548–551. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-30.4.548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dybing N.A., Fleming P.A., Adams P.J. Environmental conditions predict helminth prevalence in red foxes in Western Australia. Int. J. Parasitol. Parasites Wildl. 2013;2:165–172. doi: 10.1016/j.ijppaw.2013.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engh A.L., Nelson K.G., Peebles R., Hernandez A.D., Hubbard K.K., Holekamp K.E. Coprologic survey of parasites of spotted hyenas (Crocuta crocuta) in the Masai Mara National Reserve, Kenya. J. Wildl. Dis. 2003;39:224–227. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-39.1.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson A.B. Helminths of Minnesota Canidae in relation to food habits, and a host list and key to the species reported from north America. Am. Midl. Nat. 1944;32:358–372. [Google Scholar]

- Eslami a, Farsad-Hamdi S. Helminth parasites of wild boar, Sus scrofa, in Iran. J. Wildl. Dis. 1992;28:316–318. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-28.2.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezenwa V.O., Price S.A., Altizer S., Vitone N.D., Cook C., Ezenwa V.O., Price S.A., Altizer S., Vitone N.D., Cook K. Host traits and parasite species richness in even and odd-toed hoofed mammals, Artiodactyla and Perissodactyla. OIKOS. 2006;115:526–536. [Google Scholar]

- Falagas M.E., Papastamataki P.A., Bliziotis I.A. A bibliometric analysis of research productivity in Parasitology by different world regions during a 9-year period (1995-2003) BMC Infect. Dis. 2006;6:56. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-6-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-De-Mera I.G., Vicente J., Gortazar C., Hofle U., Fierro Y. Efficacy of an in-feed preparation of ivermectin against helminths in the European wild boar. Parasitol. Res. 2004;92:133–136. doi: 10.1007/s00436-003-0976-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorello C.V., Robbins R.G., Maffei L., Wade S.E. Parasites of free-ranging small canids and felids in the Bolivian Chaco. J. Zoo. Wildl. Med. 2006;37:130–134. doi: 10.1638/05-075.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foata J., Culioli J.L., Marchand B. Helminth fauna of wild boar in Corsica. Acta Parasitol. 2005;50:168–170. [Google Scholar]

- Foata J., Mouillot D., Culioli J.-L., Marchand B. Influence of season and host age on wild boar parasites in Corsica using indicator species analysis. J. Helminthol. 2006;80:41–45. doi: 10.1079/joh2005329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrester D.J., Conti J.A., Belden R.C. Parasites of the Florida panther (Felis concolor coryi) Proc. Helminthol. Soc. Wash. 1985;52:95–97. [Google Scholar]

- Forrester D.J., Pence D.B., Bush A.O., Holler N.R. Ecological analysis of the helminths of round-tailed muskrats (Neofiber alleni True) in southern Florida. Can. J. Zool. 1987;65:2976–2979. [Google Scholar]

- Foster G.W., Cunningham M.W., Kinsella J.M., Forrester D.J., Veterinary C. Parasitic helminths of black bear cubs (Ursus americanus) from Florida. J. Parasitol. 2011;90:173–175. doi: 10.1645/GE-127R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster G.W., Kinsella J.M., Dixon L.M., Terrell S.P., Forrester D.J., Main M.B. Parasitic helminths and arthropods of coyotes (Canis latrans) from Florida, U.S.A. Comp. Parasitol. 2003;70:162–166. [Google Scholar]

- Fourie L., Vrahimis S., Horak I., Terblanche H., Kok O. Ecto-and endoparasites of introduced gemsbok in the Orange Free State (1991).pdf. South Afr. J. Wildl. Res. 1991;21:82–87. [Google Scholar]

- Frechette E., Rau J. Helminths of the black bear in Quebec. J. Wildl. Dis. 1977;13:432–434. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-13.4.432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasso D., Feliu C., Ferrer D., Mentaberre G., Casas-Diaz E., Velarde R., Fernandez-Aguilar X., Colom-Cadena A., Navarro-Gonzalez N., Lopez-Olvera J.R., Lavin S., Fenandez-Llario P., Segal J., Serrano E. Uses and limitations of faecal egg count for assessing worm burden in wild boars. Vet. Parasitol. 2015;209:133–137. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2015.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie T.R., Greiner E.C., Chapmant C.A. Gastrointestinal parasites of the Guenons of western Uganda. J. Parasitol. 2004;90:1356–1360. doi: 10.1645/GE-311R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gompper M.E., Goodman R.M., Kays R.W., Ray J.C., Fiorello C.V., Wade S.E. A survey of the parasites of coyotes (Canis latrans) in New York based on fecal analysis. J. Wildl. Dis. 2003;39:712–717. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-39.3.712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graber M., Blanc J.P. Ancylostoma duodenale (Dubini, 1843) Creplin, 1843 (Nematoda: Ancylostomidae) parasite de l’hyenetachetee Crocuta crocuta (Erxleben), en Ethiopie. Rev. Elev. Med. Vet. Pay. 1979;32:155–160. doi: 10.19182/remvt.8169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greer K. Bears: Their Biology and Management. IUCN; 1972. Grizzly bear mortality and studies in Montana; pp. 53–66. [Google Scholar]

- Guberti V., Stancampiano L., Francisci F. Intestinal helminth parasite community in wolves (Canis lupus) in Italy. Parassitol. 1993;35:59–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta S.P. Skin penetration by infective larvae of Placoconus lotoris. Proc. Helm. Soc. Wash. 1961;28:219–220. [Google Scholar]

- Hackett F., Walters T. Helminths of the red fox in mid-Wales. Vet. Parasitol. 1980;7:181–184. [Google Scholar]

- Haddaway N.R., Watson M.J. On the benefits of systematic reviews for wildlife parasitology. Int. J. Parasitol. Parasites Wildl. 2016;5:184–191. doi: 10.1016/j.ijppaw.2016.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart R., Wagner A.M. The pathological physiology of Gaigeria pachyscelis Infestation. Onderstepoort J. Vet. Res. 1971;38:111–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa H. Two new nematodes from the Iriomote cat, Prionailurus iriomotensis, from Okinawa : Uncinaria ( Uncinaria ) maya n. sp. ( Ancylostomatoidea ) and Molineus springsmithi yayeyamanus n. subsp. (Trichostrongyloidea) J. Parasitol. 1989;75:863–869. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa H., Modrý D., Kitagawa M., Shutt K.A., Todd A., Kalousová B., Profousová I., Petrželková K.J. Humans and great apes cohabiting the forest ecosystem in Central African Republic harbour the same hookworms. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2014;8:e2715. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes B.T., Marcus A.D., Higgins D.P., Gongora J., Gray R., Slapeta J. Unexpected absence of genetic separation of a highly diverse population of hookworms from geographically isolated hosts. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2014;28:192–200. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2014.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henke S.E., Pence D.B., Bryant F.C. Effect of short-term coyote removal on populations of coyote helminths. J. Wildl. Dis. 2002;38:54–67. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-38.1.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbert A. Univ. Queretaro; Queretaro, Mexico: 2014. Caracterización Molecular, Morfológica y Ultra Estructural Del Nematodo Hematófago Uncinaria Sp. en el Lobo Marino de Galapagos. BSc Thesis. 71pp. [Google Scholar]

- Hiestand S.J., Nielsen C.K., Jiménez F.A. Epizootic and zoonotic helminths of the bobcat (Lynx rufus) in Illinois and a comparison of its helminth component communities across the American Midwest. Parasite. 2014;21:4. doi: 10.1051/parasite/2014005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilser H., Ehlers Smith Y.C., Ehlers Smith D.A. Apparent mortality as a result of an elevated parasite infection in presbytis rubicunda. Folia Primatol. 2014;85:265–276. doi: 10.1159/000363740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horak I., Meltzer G., De Vos V. Helminth and arthropod parasites of springbok, Antidorcas marsupialis, in the Transvaal and western Cape province. Onderstepoort J. Vet. Res. 1982;49:7–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horak Ivan G., Keep M.E., Spickett A.M., Boomker J. Parasites of domestic animals and wild animals in South Africa. Helminth and arthropod parasites of blue and black wildebeest. Onderstepoort J. Vet. Res. 1983;255:243–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]