ABSTRACT

Staphylococcus epidermidis is the leading cause of infections on indwelling medical devices worldwide. Intrinsic antibiotic resistance and vigorous biofilm production have rendered these infections difficult to treat and, in some cases, require the removal of the offending medical prosthesis. With the exception of two widely passaged isolates, RP62A and 1457, the pathogenesis of infections caused by clinical S. epidermidis strains is poorly understood due to the strong genetic barrier that precludes the efficient transformation of foreign DNA into clinical isolates. The difficulty in transforming clinical S. epidermidis isolates is primarily due to the type I and IV restriction-modification systems, which act as genetic barriers. Here, we show that efficient plasmid transformation of clinical S. epidermidis isolates from clonal complexes 2, 10, and 89 can be realized by employing a plasmid artificial modification (PAM) in Escherichia coli DC10B containing a Δdcm mutation. This transformative technique should facilitate our ability to genetically modify clinical isolates of S. epidermidis and hence improve our understanding of their pathogenesis in human infections.

IMPORTANCE Staphylococcus epidermidis is a source of considerable morbidity worldwide. The underlying mechanisms contributing to the commensal and pathogenic lifestyles of S. epidermidis are poorly understood. Genetic manipulations of clinically relevant strains of S. epidermidis are largely prohibited due to the presence of a strong restriction barrier. With the introductions of the tools presented here, genetic manipulation of clinically relevant S. epidermidis isolates has now become possible, thus improving our understanding of S. epidermidis as a pathogen.

KEYWORDS: Staphylococcus epidermidis, transformation, restriction system, DC10B, clonal complexes, HsdS, efficiency, methylation, restriction barrier

INTRODUCTION

Staphylococcus epidermidis is a ubiquitous human commensal that normally colonizes the human skin and mucous membranes (1). S. epidermidis can also assume an invasive lifestyle by colonizing indwelling medical devices, which in some cases can lead to invasive bacteremia. Indeed, due to the common use of implanted medical devices in modern medicine, S. epidermidis is now the number one cause of nosocomial bacteremia in the United States (2). Although these device-related infections are less severe than those due to their Staphylococcus aureus counterparts, these diseases tend to be more persistent, with most being described as subacute or chronic in nature. In many cases, infection cannot be eliminated unless the offending medical devices, such as catheters, prostheses, or pacemakers, are removed, thus leading to high morbidity rates (3). Treatment of S. epidermidis infections is also complicated by the high level of innate antibiotic resistance as well as robust biofilm formation, which can render host defenses and antibiotics ineffective (1).

To understand the commensal lifestyle of S. epidermidis and its transition into a pathogenic phenotype, it is vital to be able to genetically manipulate clinical strains of S. epidermidis. However, clinical isolates of S. epidermidis have been largely intractable genetically. The reason behind this difficulty can be traced to a strong restriction barrier that precludes the transformation of foreign DNA into clinical S. epidermidis isolates (4). In the case of S. aureus, intermediary strain RN4220 and Escherichia coli strain DC10B have been created to overcome this restriction barrier. S. aureus RN4220 is deficient in its restriction but is able to methylate, thus allowing foreign DNA to be passaged, properly modified, and subsequently used for transformation into laboratory and clinical S. aureus isolates (5). DC10B is an E. coli strain that lacks a functional Dcm methylase, thus leading to a failure to methylate the second cytosine residue in the sequences CCTGG and CCAGG and hence bypassing the type IV restriction barrier, one of the major restriction systems in S. aureus (4, 6). However, the application of these tools has proven narrow in heterologous S. aureus strains, as additional restriction systems are found in other clonal complexes (CCs). Likewise, these tools have also been found to be inadequate for the transformation of S. epidermidis.

Restriction-modification (RM) systems are the primary genetic barriers to bacterial transformation because they recognize and restrict foreign DNA (7). RM systems are categorized into four major types based on their homology and associated functions. Types I, II, and IV have been observed in both S. aureus (8–11) and S. epidermidis (4, 12, 13); the type III system appears infrequently in both species. The type I RM system is the most diverse among different clonal types and consists of restriction, modification, and specificity units, designated HsdR, HsdM, and HsdS, respectively, assembled into multisubunit complexes (14, 15). The basic modification complex, HsdMS, methylates adenine residues within a specific DNA sequence called the target recognition motif (TRM), as dictated by HsdS, while HsdR restricts unmethylated DNA. The various TRMs among type I RM systems represent bipartite and asymmetric sequences separated by a spacer of 6 to 8 random nucleotides (14). Similarly to S. aureus (10), we found that the hsdM and hsdR genes are fairly well conserved among S. epidermidis strains, while a particular hsdS gene appears to be conserved only within the same clonal complex, thus implying various specificities within the type I RM systems of S. epidermidis.

The type II RM system is composed of a methyltransferase and an endonuclease (restriction enzyme). Type II restriction enzymes usually recognize monopartite and palindromic TRMs and cut at a specific site either within the TRM or at a fixed distance from the TRM (16). Interestingly, DNA passaged through E. coli is able to bypass the type II RM system of S. aureus due to the orphan Dcm and Dam methyltransferases (6). Some S. epidermidis strains are also known to harbor at least one type II RM system: SepMI. SepMI recognizes the DNA sequence GATATC (12). This sequence, which is not methylated by either Dcm or Dam, suggests that the type II RM system in S. epidermidis, unlike its S. aureus counterpart, may play a role in preventing the effective transformation of E. coli-passaged DNA into selective S. epidermidis strains harboring the type II system.

The type III RM system occurs rarely in both S. aureus and S. epidermidis. This complex recognizes short asymmetric 5- to 6-bp-long TRMs. Methylation occurs at the N6 position within the adenine residue of the TRM (17). Restriction usually occurs some 20 bp from the TRM (17).

Finally, type IV RM systems usually contain a single endonuclease, which recognizes inappropriately methylated DNA as foreign and restricts it. S. epidermidis contains McrR, an ortholog of the S. aureus type IV RM system SauUSI (4). Like SauUSI in S. aureus, McrR is highly conserved among S. epidermidis strains and targets methylated cytosine residues for restriction (4). Thus, direct transformation of S. aureus or S. epidermidis with DNA from E. coli K-12 is difficult, as the native Dcm enzyme methylates DNA, which is recognized as foreign to S. epidermidis and also S. aureus (4). However, the type IV RM barrier in S. epidermidis and S. aureus can be bypassed with DNA from an E. coli Δdcm strain called DC10B, which produces unmethylated cytosines to avoid recognition by the type IV system (4).

In an attempt to improve the transformation of E. coli-passaged DNA into clinical S. epidermidis strains, we ascertained if type I and IV RM systems can be bypassed with proper methylation tools in E. coli. In addition, we assessed the role of the clonal complex-specific hsdS genes in the restriction barrier of S. epidermidis. For this purpose, we engineered DC10B cells, which can bypass the type IV restriction system, to encode a plasmid artificial modification (PAM) system (18) for type I HsdMS complexes of S. epidermidis strains, including NIH04008 (19), RP62A (20), NIH051475 (19), and VCU036 (21). NIH04008 belongs to CC2, the most common CC among clinical isolates, while RP62A is a CC10 laboratory-passaged strain, and the remaining two strains are clinical isolates belonging to CC89. We show that these PAM systems can enable the direct transformation of clinical S. epidermidis strains with shuttle plasmid pSK236 from E. coli DC10B.

RESULTS

Transformation efficiency in divergent strains of S. epidermidis.

Analysis of the available S. epidermidis genomes disclosed that the type I RM systems are divergent among clinical and laboratory isolates. To determine if the type I RM system belonging to a particular clonal complex is the major barrier to efficient transformation, we chose to investigate strains representing clonal complexes 10, 89, and 2. The strains included a well-characterized laboratory-passaged strain, RP62A (CC10), two clinical isolates with known genomes and a homologous type I RM system, NIH051475 (CC89) and VCU036, and NIH04008 (CC2), a clinical isolate that represents the most prominent lineage in S. epidermidis nosocomial infections (13). We used pSK236 as the target plasmid for transformation due to its copy number, pC194 origin of replication, and selectable antibiotic marker (chloramphenicol [Cm]) for all target S. epidermidis strains. Although the plasmid source used for transformation was a combination of pSK236 and recombinant pACYC184, only pSK236 was transformed into S. epidermidis recipients because pACYC184 lacks an origin of replication in S. epidermidis. Accordingly, the amount of pSK236 in each plasmid mixture (with pACYC184 and pSK236) for transformation was determined via quantitative PCR (qPCR), using a standard curve of known copy numbers of pSK236, as described previously (22). As shown in Fig. 1A, RP62A (CC10) was transformed easily with pSK236 originating from RP62A, resulting in ∼2,000 transformants per 5 μg of DNA. However, pSK236 originating from NIH051475 and VCU036, both of which belong to CC89, showed a significant reduction in transformation efficiency (∼75-fold and 5-fold decreases, respectively, compared to that for RP62A), while the plasmid from NIH04008 was at a level between those for VCU036 and NIH051475 (∼11-fold decrease compared to that for RP62A). Interestingly, pSK236 isolated from VCU036 was transformed into RP62A more efficiently (∼13-fold increase) than the plasmid from NIH051475 (Fig. 1A).

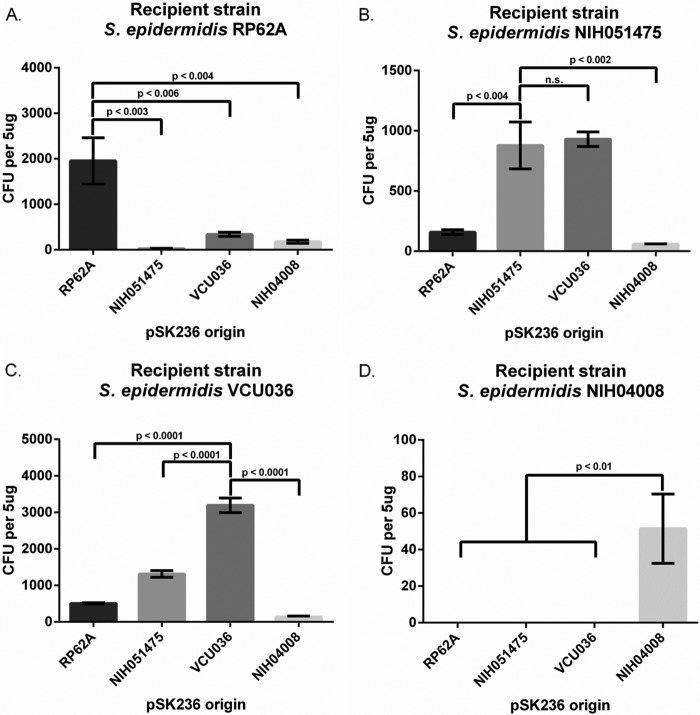

FIG 1.

Transformation efficiencies among four strains of S. epidermidis using shuttle plasmid pSK236. (A) RP62A transformed with 5 μg of pSK236 plasmids from RP62A, NIH051475, VCU036, and NIH04008. (B) NIH051475 transformed with 5 μg of pSK236 plasmids from RP62A, NIH051475, VCU036, and NIH04008. (C) VCU036 transformed with 5 μg of pSK236 plasmids from RP62A, NIH051475, VCU036, and NIH04008. (D) NIH04008 transformed with 5 μg of pSK236 plasmids from RP62A, NIH051475, VCU036, and NIH04008. NIH04008 yielded no transformants with pSK236 from RP62A, NIH051475, or VCU036. Each data point represents the mean number of transformants for each transformation (n = 3); error bars represent standard deviations. Student's unpaired t test was conducted for each experiment, with the P values shown where relevant.

We next explored the transformation of pSK236 into NIH051475 (CC89). Plasmid pSK236 originating from VCU036 was transformed into NIH051475 to a level similar to that of the plasmid derived from NIH051475 (Fig. 1B). In contrast, pSK236 originating from RP62A led to a significant reduction in the number of transformants (∼5-fold decrease) compared to that of the plasmid from NIH051475 (Fig. 1B), while pSK236 obtained from NIH04008 yielded even fewer colonies. Using VCU036 as the recipient strain, transformation of pSK236 obtained from VCU036 was easily accomplished, as expected, yielding ∼3,000 transformants per 5 μg of plasmid DNA (Fig. 1C). Curiously, pSK236 derived from NIH051475, which is part of CC89 along with VCU036, with its HsdS protein sharing 100% identity to the HsdS protein of VCU036, displayed a reduction in transformation efficiency (∼2.5-fold reduction) compared to that of the plasmid from VCU036 (Fig. 1C), even though the plasmid from either NIH051475 or VCU036 was transformed into NIH051475 with similar efficiencies (Fig. 1B). The transformation of VCU036 with pSK236 from strain RP62A resulted in an ∼6-fold reduction compared to that with the plasmid from VCU036, while the plasmid obtained from NIH04008 resulted in even fewer colonies (Fig. 1C). Finally, using NIH04008 (CC2) as the recipient strain, transformation was successful only with pSK236 obtained from NIH04008, yielding ∼50 transformants (Fig. 1D). Together, these data suggest that the efficiency of transformation between S. epidermidis strains belonging to the same clonal complex is generally higher than that between strains from a different clonal complex, thus implying at least some degree of specificity of the type I RM system within the same clonal complex.

The methylomes of S. epidermidis strains RP62A, NIH051475, VCU036, and NIH04008.

One possibility that could account for the divergent transformation frequencies among RP62A (CC10), NIH051475 (CC89), VCU036 (CC89), and NIH04008 (CC2) was the difference in their methylomes based on a particular clonal complex. Using single-molecule, real-time (SMRT) sequencing (23) to detect adenine methylation, we found that RP62A, a common laboratory-passaged isolate, contained a single major type I RM system with ∼98% of the TRM GTAN7CTC methylated at the adenine residue (underlined) (Table 1). Three additional motifs with unknown modified bases were also detected in RP62A at a lower frequency (∼12 to 29%): TTTATAVYD, GGNNBVNY, and GGBNNH. Currently, REBASE lists only two methylases in RP62A: the above-mentioned type I system and a lone type II methyltransferase. Thus, our SMRT sequencing data suggest an additional RM system(s) that has been unaccounted for in RP62A.

TABLE 1.

SMRT sequencing for residue methylation in S. epidermidis

| Staphylococcus epidermidis strain | Motifa | % motifs detected | No. of motifs detected | No. of motifs in genome | Mean modification QV | Mean motif coverage | No. of pSK236 cut sitesb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RP62A | GTANNNNNNNCTC1 | 98.1 | 673 | 686 | 209.62 | 162.53 | 2 |

| GAGNNNNNNNTAC1 | 97.81 | 671 | 686 | 197.53 | 160.10 | ||

| TTTATAVYD | 28.81 | 522 | 1,812 | 43.13 | 181.82 | ND | |

| GGNNBVNY | 26.31 | 8,436 | 32,066 | 48.16 | 162.28 | ND | |

| GGBNNH | 12.27 | 9,925 | 80,869 | 46.47 | 165.42 | ND | |

| NIH051475 | ACANNNNNGTG2 | 86.62 | 693 | 800 | 252.31 | 180.79 | 2 |

| CACNNNNNTGT2 | 86.62 | 693 | 800 | 246.75 | 181.99 | ||

| VCU036 | ACANNNNNGTG3 | 100.0 | 756 | 756 | 344.05 | 275.89 | 2 |

| CACNNNNNTGT3 | 100.0 | 756 | 756 | 330.26 | 277.13 | ||

| TTGGTAVYD | 39.75 | 192 | 483 | 50.15 | 369.35 | ND | |

| TTHHGAACR | 21.54 | 134 | 622 | 45.78 | 411.84 | ND | |

| GGNBV | 9.3 | 5,000 | 53,752 | 46.33 | 417.55 | ND | |

| NIH04008 | GAANNNNNNCTTA4 | 99.14 | 460 | 464 | 100.18 | 66.65 | 1 |

| TAAGNNNNNNTTC4 | 98.92 | 459 | 464 | 109.38 | 66.90 | ||

| CAGNNNNATC5 | 98.69 | 1,284 | 1,301 | 111.26 | 67.61 | 5 | |

| GATNNNNCTG5 | 97.77 | 1,272 | 1,301 | 104.50 | 67.26 | ||

| ATTNNNNNCTC6 | 97.5 | 1,518 | 1,557 | 110.11 | 67.80 | 3 | |

| GAGNNNNNAAT6 | 96.85 | 1,508 | 1,557 | 101.65 | 67.90 |

Matching superscript numbers indicate partner motifs; underlined residues represent methylated residues.

ND, not able to be determined due to the variability of the designated nucleotides for some of the positions.

Clinical isolates NIH051475 and VCU036, both of which belong to CC89, were predicted to contain identical type I RM systems based on sequence analysis, which revealed 100% identity between the hsdS genes of NIH051475 and VCU036. Indeed, both NIH051475 and VCU036 contain identical type I RM systems that recognize the TRM ACAN5GTG methylated at 86% and 100% frequencies, respectively. While NIH051475 contains a single adenine methylation site, VCU036 harbors three additional motifs with unknown modified bases, TTGGTAVYD, TTHHGAACR, and GGNBV, albeit at a much lower frequency of methylation (Table 1).

Finally, clinical isolate NIH04008 was predicted to contain three hsdS genes based on sequence analysis. Indeed, SMRT sequencing identified three unique TRMs present in NIH04008: GAAN6CTTA, CAGN4ATC, and TTN5CTC. All three TRM motifs were methylated at an ∼97% frequency. Collectively, these data imply that the type I RM TRM for RP62A (CC10) differs from those for strains belonging to CC89 (i.e., NIH051475 and VCU036) and CC2 (i.e., NIH04008). Among members of CC89, there are differences that can entail additional RM systems besides the major type I RM system. Finally, with the sequence of the TRM known, we identified TRMs for type I adenine methylation for all four sequenced strains in plasmid pSK236. The numbers of these TRMs, which represent cut sites in unmethylated pSK236, are indicated in Table 1.

Assessing bypass of restriction barriers I and IV in S. epidermidis.

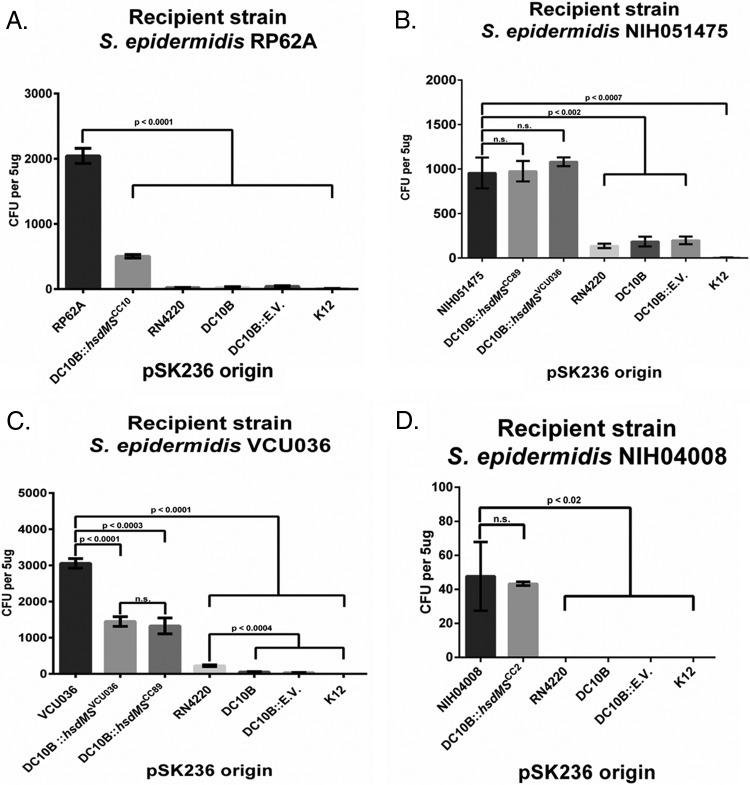

In our methylome studies, we found that RP62A, belonging to CC10, has a different type I TRM from those of clinical isolates NIH051475 and VCU036, both of which belong to CC89 and share a major and common TRM for adenine methylation, and NIH04008 (Table 1). Based on this finding and data from previous studies on S. aureus (24), we hypothesize that the major type I RM system in S. epidermidis methylating specific adenine residues on the cognate TRM to avoid homologous restriction is likely clonal complex specific. A corollary of this hypothesis is that foreign DNA that is properly methylated by the cognate RM system should be able to bypass the specific type I host restriction system. Recognizing that the type IV restriction system is another major restriction barrier in S. epidermidis (4), we proceeded to assess the effect of the CC-specific hsdMS-mediated modification of pSK236 in DC10B, an E. coli Δdcm strain that can bypass the type IV restriction system, to improve the transformation of pSK236 into divergent S. epidermidis strains. For comparison, we utilized 5 μg of pSK236 from multiple sources of E. coli, including DC10B, DC10B with empty vector pACYC184, and K-12, as well as intermediary S. aureus strain RN4220, which was previously used for proper plasmid methylation prior to transformation into divergent S. epidermidis isolates. Plasmid pSK236 isolated from E. coli strains K-12, DC10B, and DC10B with empty vector pACYC184 or S. aureus RN4220 failed to effectively transform RP62A (Fig. 2A). The plasmid pSK236 passaged through the hsdMSCC10 E. coli DC10B strain (see Table 2) can be transformed into RP62A at a frequency that is ∼12 times more efficient than that with DC10B or DC10B with empty vector pACYC184 alone (Fig. 2A). However, RP62A transformed with hsdMSCC10-modified pSK236 from DC10B did not recapitulate the transformation profile seen with the plasmid harvested directly from RP62A (Fig. 2A). This finding may be attributed to additional RM systems in RP62A, as revealed by SMRT sequencing (Table 1). In the case of NIH051475, the pSK236 plasmid (5 μg each) isolated from RN4220, DC10B, and DC10B with empty vector pACYC184 could be transformed into NIH051475, yielding ∼130 to 200 transformants each. Only the plasmid derived from K-12 was unable to transform NIH051475 (Fig. 2B). The plasmid purified from the hsdMSCC89 or hsdMSVCU036 DC10B strain (see Table 2) completely recapitulated the transformation profile of pSK236 obtained from NIH051475 (Fig. 2B). These findings suggest that the type I RM system is the primary barrier to transformation in NIH051475, which can be completely bypassed with pSK236 from VCU036, which harbors a type I RM system identical to that of NIH051475 (Table 1). The transformation of VCU036 yielded few colonies when pSK236 plasmids isolated from all E. coli strains without hsdMS genes were used (Fig. 2C). Significantly more transformants were obtained with pSK236 derived from RN4220 than with the plasmids derived from control E. coli strains (Fig. 2C). The plasmid isolated from DC10B containing either hsdMSVCU036 or hsdMSCC89 drastically increased the effectiveness of transformation, with a frequency higher than those of the control E. coli strains and RN4220, but failed to replicate the transformation profile of pSK236 from S. epidermidis strain VCU036, which yielded over 3,000 transformants (∼2-fold increase over those with the hsdMSVCU036 and hsdMSCC89 PAM strains) with 5 μg of plasmid DNA (Fig. 2C). Finally, transformation of NIH04008 could not be achieved with pSK236 derived from control E. coli strains or RN4220 (Fig. 2D). In contrast to RP62A, NIH051475, and VCU036, there are possibly three type I RM systems in NIH04008 (CC2), with two methylases (HsdM1 and HsdM2) and three specificity units (HsdS1, HsdS2, and HsdS3). Initially, we cloned single hsdMS and hsdS units (HsdM1S1, HsdM2S2, and HsdS3) into pACYC184 in DC10B; however, these constructs did not yield any transformants in NIH04008 (data not shown). Importantly, all permutations of double HsdMS units also did not lead to any transformants in NIH04008 (data not shown). When all three specificity units and two methylase units were cloned into pACYC184, a moderate number of transformants were obtained with pSK236. We designated this plasmid pACYC184::hsdCC2. Interestingly, NIH04008 was transformed with pSK236 harvested from either NIH04008 or the hsdMSCC2 PAM strain at a similar frequency (Fig. 2D), thus implying that hsdMSCC2 constitutes the major type I RM barrier in NIH04008, but other poorly described factors may prohibit the efficient transformation of this isolate belonging to CC2. Together, these observations are consistent with the divergence of type I RM systems among different clonal complexes of S. epidermidis. At its simplest, NIH051475 has a single type I RM system, while VCU036, with an analogous type I RM, entails additional RM systems, as confirmed by SMRT sequencing (Table 1), that may hinder the efficient transformation of VCU036 with the plasmid from NIH051475. Interestingly, CC2 strain NIH04008 likely encompasses a more complicated type I RM barrier, but the lower frequency of transformation in NIH04008 with the plasmid obtained directly from the cognate host indicated that there are additional factors other than the type I RM system that play a crucial role in transformation of this clonal complex.

FIG 2.

Transformation profiles of RP62A, NIH051475, VCU036, and NIH04008 with pSK236 plasmids from divergent sources. (A) RP62A transformed with 5 μg of pSK236 plasmids of various origins. (B) NIH051475 transformed with 5 μg of pSK236 plasmids of divergent origins. (C) VCU036 transformed with 5 μg of pSK236 plasmids of divergent origins. (D) NIH04008 transformed with 5 μg of pSK236 plasmids of divergent origins. NIH051475, S. epidermidis NIH051475; RP62A, S. epidermidis RP62A; VCU036, S. epidermidis VCU036; NIH04008, S. epidermidis NIH04008; DC10B::hsdMSCC10, E. coli DC10B with pACYC184::hsdMS from RP62A; DC10B::hsdMSCC89, E. coli DC10B with pACYC184::hsdMS from NIH051475; DC10B::hsdMSVCU036, E. coli DC10B with pACYC184::hsdMS from VCU036; DC10B::hsdMSCC2, E. coli DC10B with pACYC184::hsdM1S1M2S2S3 from NIH04008; DC10B, E. coli DC10B; DC10B::E.V., E. coli DC10B with empty vector pACYC184; K-12, E. coli K-12. Each data point represents the mean number of transformants for each transformation (n = 3); error bars represent standard deviations. Student's unpaired t test was conducted for each experiment, with relevant P values shown.

TABLE 2.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Bacterial strain or plasmid | Description or genotypea | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Plasmids | ||

| pACYC184 | E. coli plasmid; p15A origin of replication in E. coli; Tetr and Cmr; 4,245 bp | 33 |

| pSK236 | Shuttle plasmid; ColE1 and pC194 origins of replication in E. coli and staphylococci; Ampr in E. coli and Cmr in staphylococci; 5,597 bp | 34 |

| pMAD | Allelic replacement vector; pBR322 and pE194ts origins of replication in E. coli and staphylococci; Ampr in E. coli and Ermr in staphylococci; 9,666 bp | 32 |

| Strains | ||

| S. epidermidis RP62A | CC10; MRSEb; ST10 | 20 |

| S. epidermidis NIH051475 | CC89; ST89 | 19 |

| S. epidermidis VCU036 | CC89 | 21 |

| S. epidermidis NIH04008 | CC2; ST2 | 19 |

| S. epidermidis NIH051475 ΔhsdRMS | CC89; ST89 | This study |

| E. coli DC10B | E. coli K-12; Δdcm mutant | 5 |

| E. coli DC10B pACYC184::hsdMSCC10 | E. coli K-12; Δdcm mutant with pACYC184 containing hsdMSCC10; Cmr | This study |

| E. coli DC10B pACYC184::hsdMSCC89 | E. coli K-12; Δdcm mutant with pACYC184 containing hsdMSCC89; Cmr | This study |

| E. coli DC10B pACYC184::hsdMSVCU036 | E. coli K-12; Δdcm mutant with pACYC184 containing hsdMSVCU036; Cmr | This study |

| E. coli DC10B pACYC184::hsdMSCC2 | E. coli K-12; Δdcm mutant with pACYC184 containing hsdM1S1M2S2S3CC2; Cmr | This study |

ST10, sequence type 10.

MRSE, methicillin-resistant Staphylcoccus epidermidis.

Determination of the dose response of the PAM system in transforming S. epidermidis strains RP62A, NIH051475, VCU036, and NIH04008.

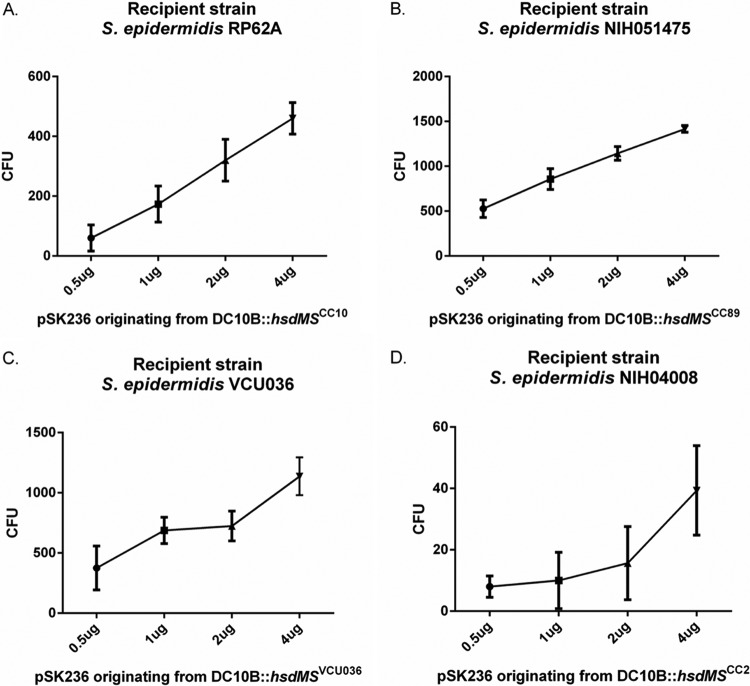

We next measured the efficiencies of our DC10B hsdMS isolates in transforming cognate S. epidermidis using pSK236 plasmids obtained from the respective PAM E. coli strains. Using pSK236 at increasing dosages, we show that the number of transformants increased with higher dosages of plasmid DNA for all S. epidermidis strains (Fig. 3A to D). NIH04008 yielded the lowest number of transformants per microgram of plasmid DNA (∼10 colonies/μg pSK26) among the four S. epidermidis strains (Fig. 3D). Both NIH051475 and VCU036 showed increased numbers of transformants with higher dosages of pSK236 (∼708 and ∼521 colonies/μg pSK236) (Fig. 3B and C). Notably, VCU036 and NIH051475 generally displayed similar numbers of transformants per microgram of PAM plasmid DNA (Fig. 3B and C). This is in contrast to the plasmid obtained from VCU036, which led to a higher efficiency of transformation into VCU036 than with the plasmids from E. coli strains containing hsdMSVCU036 or hsdMSCC89 (Fig. 2C). This finding may be explained by the presence of two additional RM systems in S. epidermidis strain VCU036 (Table 1).

FIG 3.

Transformation efficiencies of RP62A, NIH051475, VCU036, and NIH04008 with increasing concentrations of PAM-modified pSK236. (A) RP62A transformed with increasing concentrations of pSK236 derived from E. coli DC10B with pACYC184::hsdMSCC10; (B) NIH051475 transformed with increasing concentrations of pSK236 derived from E. coli DC10B with pACYC184::hsdMSCC89; (C) VCU036 transformed with increasing concentrations of pSK236 derived from E. coli DC10B with pACYC184::hsdMSVCU036; (D) NIH04008 transformed with increasing concentrations of pSK236 derived from E. coli DC10B with pACYC184::hsdM1S1M2S2S3CC2. Each point represents the mean number of transformants (n = 3); the error bars represent the standard deviations.

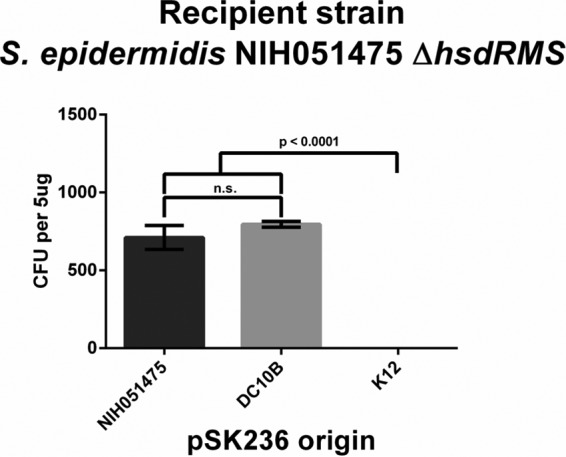

Transformation of the NIH051475 ΔhsdMS strain.

We observed in our methylome studies that NIH051475 contains a single type I RM system, which can be bypassed by a plasmid containing the homologous HsdMS system expressed in DC10B (Fig. 2B). Based on these results, we hypothesize that the deletion of the sole type I RM system in NIH051475 should enable effective transformation with the plasmid obtained from DC10B, which normally can bypass only the type IV restriction system of S. epidermidis. For this purpose, the type I RM system of NIH051475 was deleted by allelic exchange with pMAD (see Materials and Methods), and competent cells were then generated and transformed with pSK236 plasmids derived from wild-type (WT) NIH051475, DC10B, and K-12. Transformation of the NIH051475 ΔhsdRMS strain with pSK236 harvested from WT NIH051475 or DC10B yielded comparable levels of transformants, whereas pSK236 derived from E. coli K-12 failed to transform the NIH051475 ΔhsdRMS strain (Fig. 4). These data suggest that the reduced transformation efficiency of NIH051475 with the DC10B intermediary strain is likely due to the sole type I RM barrier and that the type IV barrier alone is efficient in preventing the introduction of recombinant DNA into NIH051475, since the plasmid transformation efficiency with DC10B is higher than that with K-12.

FIG 4.

Transformation profile of the NIH051475 ΔhsdRMS strain with pSK236 plasmids from divergent sources. The ΔhsdRMS mutant of NIH051475 was transformed with 5 μg of pSK236 plasmids of various origins. Each data point represents the mean number of transformants for each transformation (n = 3); error bars denote standard deviations. Student's unpaired t test was conducted for each experiment, and P values are shown where appropriate.

DISCUSSION

The pathogenesis of S. epidermidis in device-related infections is poorly understood, largely due to our inability to transform and genetically manipulate clinical isolates. Thus, it is imperative to construct tools to improve the transformation efficiency of clinically relevant S. epidermidis strains. Previously, E. coli strain DC10B was generated in order to bypass the type IV RM systems of S. aureus and S. epidermidis (4). However, this tool does not account for the type I RM barriers; as a result, its application to S. epidermidis proved limited. Other genetic tools, like the recently reported S. aureus phage ϕ187 adapted to coagulase-negative staphylococci (CoNS) (25), have augmented the number of transformable S. epidermidis strains to include strains that are recalcitrant to electroporation. However, ϕ187 transduction is dependent on the presence of the cognate phage receptor on the recipient strains; plasmid DNA, once inside the clinical isolate, is still subjected to type I restriction. Accordingly, we sought here to generate tools to enable the effective transformation of clinical isolates by bypassing both the type I and IV RM systems of S. epidermidis.

Previous work with S. aureus has shown that lineages from different clonal complexes of S. aureus express divergent HsdS enzymes recognizing different TRMs (24). In agreement with that observation, we found that this is also the case with S. epidermidis because RP62A (CC10), NIH051475 (CC89), and NIH04008 (CC2) express divergent hsdS genes that specify different TRMs, while NIH051475 and VCU036, both of which belong to CC89, exhibit identical TRMs for the type I RM system (Table 1). Consequently, the transformation efficiency between divergent lineages belonging to different clonal complexes of S. epidermidis is poor (Fig. 1). Transformation between strains NIH051475 and VCU036, which share identical type I RM systems, proved far more effective (Fig. 1B and C), as can be predicted from the methylomes. While the plasmid from VCU036 was able to completely bypass the sole RM system of NIH051475 (Fig. 1B), the contrary was not true for the plasmid obtained from NIH051475, since it failed to achieve the same level of efficiency of transformation into VCU036 as that of the plasmid derived from the homologous host (Fig. 1C). Notably, pSK236 isolated from VCU036 (CC89) was transformed into RP62A (CC10) significantly better than was the plasmid isolated from NIH051475 (CC89) (Fig. 1A). These results implied that RP62A and VCU036 may harbor additional RM systems that preclude more efficient transformation of plasmid DNA. Indeed, SMRT sequencing results confirmed that RP62A and VCU036 harbor additional but poorly defined RM systems not present in NIH051475 (Table 1). One of these motifs is GGNNBVNY in RP62A, which is similar to the GGNBV motif in VCU036 albeit with a lower frequency of detection, at 26% and 9%, respectively. These differences between and within lineages appear to support the observation that clinical populations of S. epidermidis are more diverse (26, 27) than those of the more homogeneous S. aureus (28). Therefore, not only are lineage-specific type I RM systems important considerations for efficient transformation, there also may be additional strain-specific RM systems that hinder efficient transformation among and within different lineages.

With respect to the type I RM system, we have found that the HsdS specificity units of S. epidermidis appear to be more divergent, showing a larger distance between individual clusters in S. epidermidis (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material) than in S. aureus (Fig. S2). The more distant but rare node in the S. aureus tree (e.g., FDA209P and H-EMRSA-15) may comprise possible recombination events between the two species. In a combined tree of S. aureus and S. epidermidis (not shown), the latter two isolates seem to cocluster in an S. epidermidis group. Overall, these data revealed a higher level of diversity of HsdS enzymes in the type I RM systems among S. epidermidis strains than among their S. aureus counterparts and may help explain why it is so much more difficult to transform plasmids into S. epidermidis isolates found in the clinical setting.

Based on sequence analyses of S. epidermidis and previous studies with S. aureus (24), we reckoned that type I and type IV RM systems are likely the major RM systems in S. epidermidis. Accordingly, DNA that is properly methylated at a specific TRM for the type I RM system in E. coli will enable direct efficient transformation into homologous S. epidermidis strains as long as the plasmid is propagated in DC10B to bypass the type IV RM system. Using this strategy (22), we have developed a PAM system in E. coli where the hsdMS genes from S. epidermidis are expressed to methylate target plasmid DNA based on specific clonal complexes. We were able to efficiently transform one laboratory isolate, RP62A, and, more importantly, three clinical S. epidermidis strains, NIH051475, VCU036, and NIH04008, with the DC10B-derived plasmid (Fig. 2). This finding is of major importance because clinical S. epidermidis isolates are notoriously difficult to transform, thus posing a formidable barrier to understanding the pathogenesis of S. epidermidis in a proper clinical context. As a proof of concept, we showed that these PAM strains enhance CC-specific transformation dramatically in S. epidermidis isolates compared to previously developed genetic tools, such as RN4220 (5) and DC10B (4) (Fig. 2), while the plasmid isolated from E. coli strain K-12 did not yield any transformants with each of the four S. epidermidis strains (Fig. 2). Taken together, our data suggest that, besides bypassing the type IV RM barrier via DC10B, it is crucial to overcome the barrier presented by the type I RM system to achieve efficient transformation. Based on the number of transformants from the plasmid derived from DC10B or PAM-enabled DC10B, it appears that the type I RM system is the major obstacle to effective transformation in S. epidermidis. Interestingly, the plasmid methylated by the gene product of hsdMSCC89 (derived from NIH051475) as well as that from VCU036 (also of CC89) can completely recapitulate the profile of transformation of pSK236 from the cognate strain into S. epidermidis NIH051475 (Fig. 2B). This finding was supported by SMRT sequencing data, where the TRMs of the type I RM systems (GTAN7CTC) in these two strains are identical. As additional motifs were discovered in the methylome of VCU036 compared to NIH051475 (Table 1), we observed that the plasmid obtained from NIH051475 led to fewer transformants in VCU036 than the plasmid derived from VCU036 itself (Fig. 1C). As we cannot completely recapitulate the transformation profiles of RP62A and VCU036, we surmise that the transformation efficiency could be augmented with the expression of additional RM systems in a single E. coli strain.

To confirm that NIH051475 holds single type I and type IV RM systems as the restriction barriers, we first transformed recombinant pMAD from our PAM strain into NIH051475. Using this recombinant pMAD, a deletion mutant of NIH051475 lacking the type I hsdRMS genes was constructed. Upon transformation of the NIH051475 ΔhsdRMS mutant, equal transformation efficiencies were realized with pSK236 harvested from NIH051475 and the DC10B (Fig. 4), thus confirming that single type I and type IV RM systems are the sole restriction barriers in NIH051475.

S. epidermidis strains belonging to CC2 are the most common isolates (up to 74%) encountered in clinical infections (13). Previously, Lee et al. were the first group to identify two complete type I RM systems and one incomplete type I RM system of a CC2 S. epidermidis isolate, BPH0662. They also showed that the two complete type I systems were functional, yielding TRMs of CAGN4ATC and GAGN5AAT, while the incomplete third system was nonfunctional (13). Interestingly, we determined that the two complete type I systems observed in CC2 isolate BPH0662 were also present in NIH04008, while the third type I RM system appears to be functional, with a TRM of GAAN6CTTA methylated at a high frequency. The expression of all three type I RM systems in our E. coli PAM strain was necessary to effectively transform NIH04008. In contrast to NIH051475 (CC89) and RP62A (CC10), the transformation efficiency of NIH04008 with pSK236 from the cognate host is much lower than those of the NIH051475 and RP62A counterparts (Fig. 1D). The plasmid harvested from the DC10B::hsdMSCC2 strain displayed a similarly low transformation efficiency compared to that of the plasmid harvested directly from NIH04008 (Fig. 2D). This finding indicated that other factors besides the RM systems (e.g., cell wall barrier, DNA uptake, or another as-yet-undescribed restriction system) account for the low overall transformation efficiency of NIH04008.

The type I and type IV RM systems of S. epidermidis act as strong barriers to transformation, largely prohibiting genetic manipulation in clinically relevant strains and thus limiting our ability to understand S. epidermidis as an opportunistic pathogen. Our study has demonstrated, for the first time, the direct and efficient transformation of clinical S. epidermidis strains with plasmids isolated from E. coli DC10B strains expressing the cognate HsdMS enzymes of S. epidermidis. The construction of these E. coli strains will open the way to genetically manipulating clinical S. epidermidis strains, especially those belonging to CC2, with extremely poor transformation efficiencies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 2. S. epidermidis strains were routinely cultured in filter-sterilized brain heart infusion (BHI) medium, and E. coli strains were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth. All strains were grown at 37°C with shaking at 250 rpm. Cell densities were determined by measuring the absorbance (optical density [OD]) at 600 nm (unless noted otherwise) in a Spectronic 20D+ spectrophotometer. Solid growth medium was prepared by solidifying BHI medium with 1.5% agar (BHA) or LB broth with 1.5% agar (LB agar). The following antibiotics were used: ampicillin (Amp) at 100 μg/ml and Cm at 30 μg/ml for E. coli and 10 μg/ml for S. epidermidis.

SMRT sequencing.

Genomic DNA was purified from 20-ml exponential-phase cultures by using the genomic-tip-500g kit (Qiagen). Large DNA was precipitated in isopropanol, extensively washed with cold 75% ethanol, and then solubilized by gentle mixing in 1× Tris-EDTA (TE) buffer. Purity and quantity were assessed by using NanoDrop and Qubit assays, respectively, before size evaluation with a Tape Station (Agilent). DNA was sequenced on a Pacific Biosciences RS system at the Lausanne Genomic Technologies Facility, Centre for Integrative Genomics. Using P6-C4 chemistry, libraries of approximately 8 to 20 kb were generated. Analyses of reads were carried out by using SMRT pipe version 2.3.0 software (Pacific Bioscience). The quality value (QV) threshold for motif calling was set to 30.

DNA manipulations and generation of competent cells.

Purification of E. coli plasmids was performed with Omega EZNA miniprep kits according to the manufacturer's instructions. Plasmid isolation from S. epidermidis was performed as previously described (29), using lysostaphin as the cell wall-lytic agent. For the preparation of competent cells, cultures of individual S. epidermidis strains grown overnight were diluted to an OD at 578 nm (OD578) of 0.5 in prewarmed BHI broth, incubated for an additional 30 min at 37°C with shaking, transferred to centrifuge tubes, and then chilled on ice for 10 min. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 4,000 rpm at 4°C for 10 min and washed serially with 1 volume, a 1/10 volume, and then a 1/25 volume of cold autoclaved water, followed by repelleting at 4°C after each wash. After the final wash, cells were resuspended in a 1/200 volume of cold 10% sterile glycerol and aliquoted at 50 μl into tubes for frozen storage at −80°C.

Transformation protocol.

Transformation of S. epidermidis isolates was performed with electrocompetent S. epidermidis cells that were prepared as described previously by Löfblom et al. (30) and Monk et al. (4). Frozen competent cells were placed on ice for 5 min and then at room temperature for 5 min, spun at 5,000 × g for 1 min, and resuspended in 50 μl of 10% glycerol supplemented with 500 mM sucrose. After the addition of purified DNA, the cells were then pulsed in a 1-mm cuvette on a Micropulser instrument (Bio-Rad) at 2.1 kV with a time constant of 1.1 ms. Cells were then immediately resuspended in 1 ml of BHI medium supplemented with 500 mM sucrose, shaken for 1 h at 37°C, and then plated onto BHI agar with 10 μg/ml Cm at 37°C.

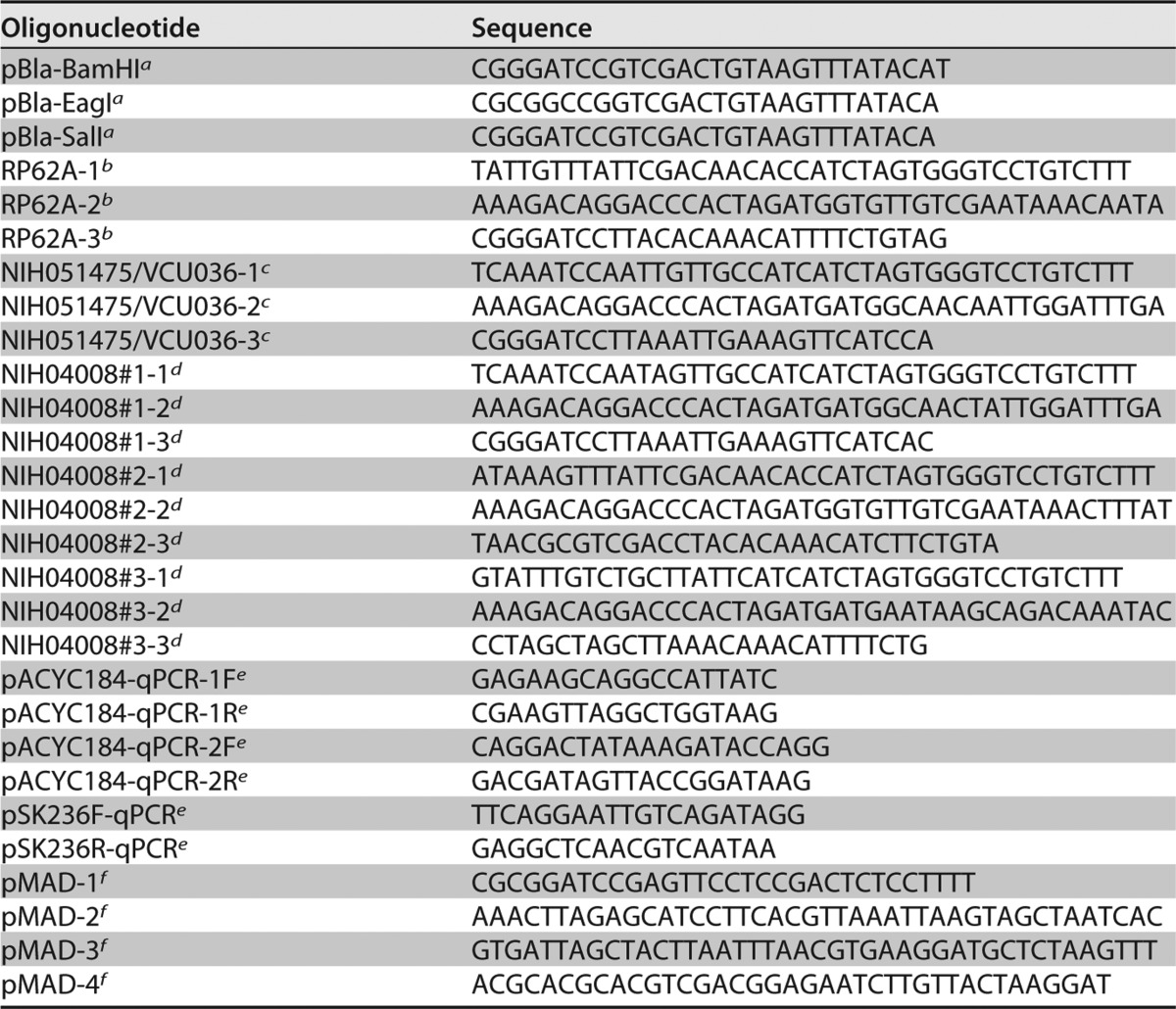

Engineering PAM systems into DC10B cells for transformation into S. epidermidis.

The hsdM and hsdS genes of S. epidermidis strains RP62A (20), NIH051475 (19), VCU036 (21), and NIH04008 (19) were amplified separately from chromosomal DNA by using the primers listed in Table 3. To ensure expression, we cloned, by the gene SOEing technique (31), the E. coli sigma-70 Pbla promoter and the consensus ribosome binding site (BBa_J61101) upstream of the respective hsdM and hsdS genes, which were amplified by PCR using specific primer sets (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Oligonucleotides used in this study

aForward Pbla cloning primers, introduced as either a BamHI, EagI, or SalI restriction site upstream of the cloned hsdMS genes.

bRP62A hsdMS cloning and SOEing primers.

cNIH051475 and VCU036 hsdMS cloning and SOEing primers.

dNIH04008 hsdMS cloning and SOEing primers.

eqPCR primers for quantifying pACYC184 and pSK236 levels in PAM E. coli strains.

fPrimers for cloning and SOEing ∼1,000-bp regions upstream and downstream of the NIH051475 hsdRMS genes.

The PCR-amplified products for RP62A, NIH051475, and VCU036 were digested with BamHI and SalI, ligated into similarly digested pACYC184 using T4 DNA ligase (New England BioLabs), transformed into E. coli DC10B, and plated onto LB agar with 30 μg/ml Cm at 37°C. In the case of NIH04008, which appears to contain three type I RM systems with two methylation units and three distinct specificity units (HsdM1, HsdM2, HsdS1, HsdS2, and HsdS3), each of these units was added sequentially to a single pACYC184 plasmid with subsequent digestion, ligation, and transformation reactions using EagI and SalI for hsdM2S2, SalI and BamHI for hsdM1S1, and BamHI and NheI for hsdS3. Correct transformants were validated by restriction digestion and sequencing of the insert. The correct constructs are annotated pACYC184::hsdMSCC10 for strain RP62A, pACYC184::hsdMSCC89 for strain NIH051475, pACYC184::hsdMSVCU036 for strain VCU036, and pACYC184::hsdMSCC2 for strain NIH04008 (Table 2). DC10B strains containing the respective recombinant pACYC184 plasmids were then transformed with the second “reporter plasmid” pSK236, selecting for Amp resistance.

The quantity and purity of the specific plasmids obtained from DC10B were first determined by measuring the absorbance at 260 nm and 280 nm on a NanoDrop 2000c instrument (Thermo Fisher Scientific). By using a Roche 480 II Light Cycler, real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) was carried out to determine the ratio of pACYC184::hsdMS to pSK236 for each strain of DC10B. Samples were run in triplicate by using LightCycler 480 SYBR green I master mix, according to the manufacturer's specifications and cycling conditions, using the primer sets listed in Table 3. Standard curves were generated by using known copy numbers of pACYC184 and pSK236, with the quantity of the unknown deduced from these standard curves by using Light Cycler 480SW software (version 1.5.1.62). Correct amplification products were validated by melt curve analysis.

As the recombinant pACYC184 plasmids do not replicate in S. epidermidis, the transformation efficiencies of the PAM strains can be assessed by electroporating the corresponding S. epidermidis strains with various concentrations of pSK236, as described above. The number of transformants per unit concentration of plasmid DNA was then plotted to determine the transformation efficiency of S. epidermidis with pSK236 plasmids obtained from the respective PAM E. coli strains.

Allelic replacement in S. epidermidis with pMAD.

Using allelic replacement plasmid pMAD (32), the hsdRMS genes of NIH051475, which contains a single type I RM system, were selectively deleted. Briefly, ∼1,000-bp fragments upstream and downstream of the hsdRMS genes of NIH051475 were amplified by PCR and joined by gene SOEing using specific primer sets (Table 3). Joined fragments were digested with BamHI and SalI, ligated into the similarly digested pMAD vector by using T4 DNA ligase (New England BioLabs), and subsequently used to transform E. coli DC10B harboring pACYC184::hsdMSCC89, followed by plating of cells onto LB agar with 100 μg/ml Amp and 30 μg/ml Cm at 37°C. Correct transformants were validated by restriction digestion and sequencing of the insert. The verified construct was annotated pMAD::ΔhsdRMSCC89. NIH051475 was then transformed with ∼5 μg of pMAD::ΔhsdRMSCC89 from DC10B and plated onto BHA with 2.5 μg/ml erythromycin and 50 μl of 40 mg/ml of 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (X-Gal) at 30°C. A single blue colony was selected, grown in BHI broth with 2.5 μg/ml erythromycin overnight at 30°C, diluted 1:100 (final volume, 100 ml) into fresh BHI medium without antibiotics, and incubated for 24 h at 43°C, followed by another dilution and growth at 43°C to promote the single-crossover event by selecting for light blue colonies grown on BHA supplemented with 2.5 μg/ml erythromycin and 50 μl of 40 mg/ml X-Gal at 43°C. To promote the double-crossover event, the light blue colonies described above were incubated in BHI broth without antibiotics overnight at 30°C. Dilutions were plated onto BHA supplemented with 50 μl of 40 mg/ml X-Gal and incubated overnight at 37°C. White colonies were selected and patched onto BHA supplemented with either 2.5 μg/ml erythromycin or 50 μl of 40 mg/ml of X-Gal. White colonies that failed to grow on BHA plus 2.5 μg/ml erythromycin were selected and verified for the deletion of hsdRMS by sequencing. The correct mutant was annotated the S. epidermidis NIH051475 ΔhsdRMS strain. Competent cells of the NIH051475 ΔhsdRMS strain were prepared as described above and used to assess the transformation efficiency with 5 μg of pSK236 derived from wild-type S. epidermidis NIH051475, the E. coli DC10B PAM strain, or E. coli K-12.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis was performed by using GraphPad Prism version 6.0c.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by the NIH (grant AI106937 to A.L.C.) and the Swiss National Foundation (grant 31003A_153474 to P.F.).

We acknowledge Nadia Gaïa for her analysis of HsdS in S. epidermidis and S. aureus.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/JB.00271-17.

REFERENCES

- 1.Otto M. 2009. Staphylococcus epidermidis—the “accidental” pathogen. Nat Rev Microbiol 7:555–567. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sievert DM, Ricks P, Edwards JR, Schneider A, Patel J, Srinivasan A, Kallen A, Limbago B, Fridkin S. 2013. Antimicrobial-resistant pathogens associated with healthcare-associated infections: summary of data reported to the National Healthcare Safety Network at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009-2010. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 34:1–14. doi: 10.1086/668770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blot SI, Depuydt P, Annemans L, Benoit D, Hoste E, De Waele JJ, Decruyenaere J, Vogelaers D, Colardyn F, Vandewoude KH. 2005. Clinical and economic outcomes in critically ill patients with nosocomial catheter-related bloodstream infections. Clin Infect Dis 41:1591–1598. doi: 10.1086/497833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Monk IR, Shah IM, Xu M, Tan M, Foster TJ. 2012. Transforming the untransformable: application of direct transformation to manipulate genetically Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis. mBio 3:e00277-11. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00277-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kreiswirth BN, Löfdahl S, Betley MJ, O'Reilly M, Schlievert PM, Bergdoll MS, Novick RP. 1983. The toxic shock syndrome exotoxin structural gene is not detectably transmitted by a prophage. Nature 305:709–712. doi: 10.1038/305709a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Palmer B, Marinus MG. 1994. The dam and dcm strains of Escherichia coli—a review. Gene 143:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90597-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vasusa K, Nagaraja V. 2013. Diverse functions of restriction-modification systems in addition to cellular defense. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 77:53–72. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00044-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stobberingh E, Schiphof R, Sussenbach J. 1977. Occurrence of a class II restriction endonuclease in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol 131:645–649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Szilak L, Venetianer P, Kiss A. 1990. Clonal and nucleotide sequence of the genes coding the Sau961 restriction and modification enzymes. Nucleic Acids Res 18:4659–4664. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.16.4659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Waldron DE, Lindsay JA. 2006. Sau1: a novel lineage-specific type I restriction-modification system that blocks horizontal gene transfer into Staphylococcus aureus and between S. aureus isolates of different lineages. J Bacteriol 188:5578–5585. doi: 10.1128/JB.00418-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu S, Corvaglia AR, Chan S, Zheng Y, Linder PA. 2011. Type IV modification-dependent restriction enzyme SauUSI from Staphylococcus aureus subsp. aureus USA300. Nucleic Acids Res 39:5597–5610. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Belkebir A, Azeddoug H. 2011. Purification and characterization of SepII a new restriction endonuclease from Staphylococcus epidermidis. Microbiol Res 167:90–94. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee JYH, Monk IR, Pidot SJ, Singh S, Chua KYL, Seemann T, Stinear TP, Howden BP. 2016. Functional analysis of the first complete genome sequence of a multidrug resistant sequence type 2 Staphylococcus epidermidis. Microb Genomics doi: 10.1099/mgen.0.000077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Loenen WAM, Dryden DTF, Raleigh EA, Wilson GG. 2013. Type I restriction enzymes and their relatives. Nucleic Acids Res 42:20–44. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murray NE. 2000. Type I restriction systems: sophisticated molecular machines (a legacy of Bertani and Weigle). Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 64:412–434. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.64.2.412-434.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pingoud A, Jeltsch A. 2001. Structure and function of type II restriction endonucleases. Nucleic Acids Res 29:3705–3727. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.18.3705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rao DN, Dryden DTF, Bheemanaik S. 2014. Type III restriction-modification enzymes: a historical perspective. Nucleic Acids Res 42:45–55. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yasui K, Kano Y, Tanaka K, Watanabe K, Shimizu-Kadota M, Yoshikawa H, Suzuki T. 2009. Improvement of bacterial transformation efficiency using plasmid artificial modification. Nucleic Acids Res 37:e3. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Conlan S, Mijares LA, NISC Comparative Sequencing Program, Becker J, Blakesley RW, Bouffard GG, Brooks S, Coleman H, Gupta J, Gurson N, Park M, Schmidt B, Thomas PJ, Otto M, Kong HH, Murray PR, Segre JA. 2012. Staphylococcus epidermidis pan-genome sequence analysis reveals diversity of skin commensal and hospital infection-associated isolates. Genome Biol 13:R64. doi: 10.1186/gb-2012-13-7-r64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Christensen GD, Simpson WA, Bisno AL, Beachey EH. 1982. Adherence of slime-producing strains of Staphylococcus epidermidis to smooth surfaces. Infect Immun 37:318–326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jones M, Brinkac LM, Durkin AS, Kim M, Kreiswirth B, Mishra P, Singh I, Peterson S. 2014. Genome sequence of Staphylococcus species. Direct submission to EMBL/GenBank/DDBJ databases (accession number JHUA00000000). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jones MJ, Donegan NP, Mikheyeva IV, Cheung AL. 2015. Improving the transformation of Staphylococcus aureus belonging to the CC1, CC5 and CC8 clonal complexes. PLoS One 10:e0119487. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Flusberg BA, Webster DR, Lee JH, Travers KJ, Olivares EC, Clark TA, Korlach J, Turner SW. 2010. Direct detection of DNA methylation during single-molecule, real-time sequencing. Nat Methods 7:461–465. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Monk IR, Tree JJ, Howden BP, Stinear TP, Foster TJ. 2015. Complete bypass of restriction systems for major Staphylococcus aureus lineages. mBio 6:e00308-15. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00308-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Winstel V, Kühner P, Krismer B, Peschel A, Rohde H. 2015. Transfer of plasmid DNA to clinical coagulase-negative staphylococcal pathogens by using a unique bacteriophage. Appl Environ Microbiol 81:2481–2488. doi: 10.1128/AEM.04190-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cherifi S, Byl B, Deplano A, Nonhoff C, Denis O, Hallin N. 2013. Comparative epidemiology of Staphylococcus epidermidis isolates from patients with catheter-related bacteremia and from healthy volunteers. J Clin Microbiol 51:1541–1547. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03378-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Francois P, Hochmann A, Huyghe A, Bonetti EJ, Renzi G, Harbarth S, Klingenberg C, Pittet D, Schrenzel J. 2008. Rapid and high-throughput genotyping of Staphylococcus epidermidis isolates by automated multilocus variable-number of tandem repeats: a tool for real-time epidemiology. J Microbiol Methods 72:296–305. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Witney A, Marsden GL, Holden MTG, Stabler RA, Husain SE, Vass JK, Butcher PD, Hinds J, Lindsay JA. 2005. Design, validation, and application of a seven-strain Staphylococcus aureus PCR product microarray for comparative genomics. Appl Environ Microbiol 71:7504–7514. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.11.7504-7514.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schenk S, Laddaga RA. 1992. Improved method for electroporation of Staphylococcus aureus. FEMS Microbiol Lett 73:133–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1992.tb05302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Löfblom J, Kronqvist N, Uhlén M, Ståhl S, Wernérus H. 2007. Optimization of electroporation-mediated transformation: Staphylococcus carnosus as model organism. J Appl Microbiol 102:736–747. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2006.03127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Galdzicki M, Rodriguez C, Chandran D, Sauro HM, Gennari JH. 2011. Standard Biological Parts Knowledgebase. PLoS One 6:e17005. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arnaud M, Chastanet A, Débarbouillé M. 2004. New vector for efficient allelic replacement in naturally nontransformable, low-GC-content, Gram-positive bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol 70:6887–6891. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.11.6887-6891.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chang AC, Cohen SN. 1978. Construction and characterization of amplifiable multicopy DNA cloning vehicles derived from the P15A cryptic miniplasmid. J Bacteriol 134:1141–1156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mahmood R, Khan SA. 1990. Role of upstream sequences in the expression of the staphylococcal enterotoxin B gene. J Biol Chem 265:4652–4656. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.