ABSTRACT

There has been major interest by the scientific community in antivirulence approaches against bacterial infections. However, partly due to a lack of viable lead compounds, antivirulence therapeutics have yet to reach the clinic. Here we investigate the development of an antivirulence lead targeting quorum sensing signal biosynthesis, a process that is conserved in Gram-positive bacterial pathogens. Some preliminary studies suggest that the small molecule ambuic acid is a signal biosynthesis inhibitor. To confirm this, we constructed a methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) strain that decouples autoinducing peptide (AIP) production from regulation and demonstrate that AIP production is inhibited in this mutant. Quantitative mass spectrometric measurements show that ambuic acid inhibits signal biosynthesis (50% inhibitory concentration [IC50] of 2.5 ± 0.1 μM) against a clinically relevant USA300 MRSA strain. Quantitative real-time PCR confirms that this compound selectively targets the quorum sensing regulon. We show that a 5-μg dose of ambuic acid reduces MRSA-induced abscess formation in a mouse model and verify its quorum sensing inhibitory activity in vivo. Finally, we employed mass spectrometry to identify or confirm the structure of quorum sensing signaling peptides in three strains each of S. aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis and single strains of Enterococcus faecalis, Listeria monocytogenes, Staphylococcus saprophyticus, and Staphylococcus lugdunensis. By measuring AIP production by these strains, we show that ambuic acid possesses broad-spectrum efficacy against multiple Gram-positive bacterial pathogens but does not inhibit quorum sensing in some commensal bacteria. Collectively, these findings demonstrate the promise of ambuic acid as a lead for the development of antivirulence therapeutics.

KEYWORDS: Agr system, Staphylococcus aureus, ambuic acid, inhibitors, virulence regulation

INTRODUCTION

The World Health Organization describes antimicrobial resistance as a “growing public health threat of broad concern” (1). Drug-resistant bacterial infections are responsible for at least 23,000 mortalities in the United States each year, and their annual burden on our health care system is estimated to be more than $55 billion (1). One of the most common causes is methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), which is responsible for over 80,000 invasive infections and over 11,000 deaths per year (2). Compounding the problem of bacterial resistance development, the pipeline for new anti-infectives is severely depleted, and we have witnessed a decrease of more than 50% in the number of new anti-infective therapeutics approved for treatment from 1983 to 2002 (3). Increased incidence of drug-resistant infections combined with a lack of new approved treatments constitutes an impending crisis for human health (4).

The current practice of applying antibiotics as preventatives or for the treatment of minor infections speeds the process of resistance development and compromises the effectiveness of existing treatments. The arsenal of antibiotics at our disposal constitutes a precious resource that must be preserved through effective stewardship (5). One approach to improve antibiotic stewardship would be development of novel anti-infective therapeutic approaches, and the so-called “antivirulence” approach is a promising strategy toward this goal. Antivirulence agents function by targeting nonessential pathways to reduce bacterial pathogenicity (6). Although therapeutics based on the antivirulence approach have yet to reach the clinic, they have shown excellent efficacy in animal models (7–10). Hypothetical advantages of antivirulence therapeutics would include limiting the evolution of widespread drug resistance, facilitating the development of host immune responses, and avoiding negative impacts on the normal microbial flora (7).

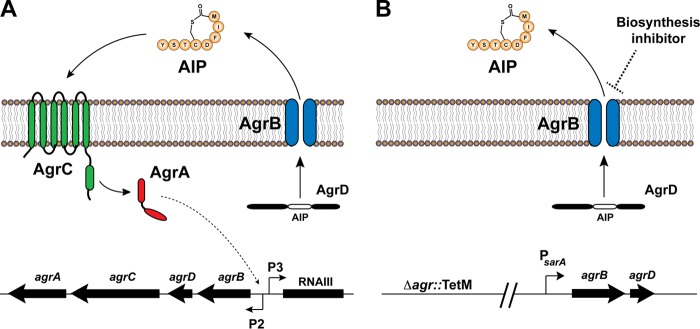

For Gram-positive bacterial pathogens, virulence is most often regulated via the agr quorum sensing system (Fig. 1A) (11). In S. aureus, this system consists of four primary components encoded by the agrBDCA operon. AgrD is a propeptide that is processed into an autoinducing peptide (AIP) and released from the cell by the membrane endopeptidase AgrB. AIP then binds to the membrane-bound histidine kinase AgrC, inducing a signal transduction cascade. This results in the phosphorylation of the AgrA response regulator, which binds two promoters, P2 and P3, resulting in the expression of transcripts RNAII and RNAIII, respectively. RNAII transcription leads to production of the encoded AgrBDCA components, while RNAIII transcription regulates a variety of cellular functions, including, most importantly, induction of expression of virulence factors, such as toxins and exo-enzymes.

FIG 1.

Quorum sensing system in Staphylococcus aureus. (A) Schematic of the agr quorum sensing system. Note that there are four different Agr types of S. aureus, each of which, by virtue of variability in the sequence of AgrD, produces a slightly different sequence of AIP (AIP-I, -II, -III, and -IV). (B) Schematic of the engineered S. aureus strain (AH2989). The entire agr system was deleted from this strain, and the agrBD type I genes were added back on the chromosome under the control of the sarA P1 promoter. This strain constitutively produces AIP without quorum sensing control.

A number of investigators have sought to identify small molecule antivirulence compounds that target the S. aureus agr system. Such compounds are often referred to as quorum quenchers or quorum sensing inhibitors. The majority of quorum sensing inhibitors identified to date target the AgrC receptor (12–16). Animal model studies have shown inhibitors targeting AgrC to be effective for reducing skin abscess formation in vivo (10). However, the structure of AgrC varies even among different strains of Staphylococcus aureus; there are four different agr types, each with a different AgrC protein and each producing a slightly different variant of AIP (AIP I, II, III, and IV). Furthermore, there is evidence that AgrC is hypermutable (17, 18), suggesting resistance could quickly evolve. Thus, there are concerns as to whether AgrC will serve as an effective target for development of clinically viable antivirulence therapeutics.

A promising target for broad-spectrum antivirulence agents is quorum sensing signal biosynthesis. Critical to the signal biosynthesis process is the transmembrane protein AgrB, which is present in multiple Gram-positive bacterial pathogens, including Staphylococcus, Listeria, Enterococcus, and Clostridium (11). To date, only one compound, the small molecule fungal metabolite ambuic acid, has been reported to be a putative agr signal biosynthesis inhibitor (19). Ambuic acid is a highly functionalized cyclohexenone first isolated by Strobel and coworkers from endophytes of tropical rainforest plants (20). In 2009, Nakayama et al. reisolated this compound when it demonstrated activity in a screen for antivirulence activity against Enterococcus faecalis (19). Nakayama and coworkers showed preliminary findings suggesting that ambuic acid inhibited quorum sensing signaling in several bacterial pathogens and hypothesized that it might function as a broad-spectrum agent against such pathogens. With this study, we employed a unique combination of genetic engineering and quantitative mass spectrometric measurements that enabled an in-depth exploration of the phenomenon of quorum sensing inhibition by ambuic acid. Using this approach, we confirm that ambuic acid functions as a signal biosynthesis inhibitor and show that it inhibits the quorum sensing system for a number of Gram-positive bacterial pathogens but does not impact the quorum sensing system of several commensal strains. On the basis of these promising findings, we employed a mouse skin infection model to measure in vivo quorum sensing inhibition by ambuic acid and to evaluate for the first time its ability to abate MRSA pathogenesis.

RESULTS

Ambuic acid functions as a signal biosynthesis inhibitor.

Signal biosynthesis is a particularly appealing target for quorum sensing inhibitors because of it is widely conserved among Gram-positive bacterial pathogens (18). Nakayama et al. proposed that ambuic acid inhibits the fsr system in Enterococcus faecalis, which is homologous to the agr system present in S. aureus. Their study suggested inhibition of enzyme activity of the biosynthesis protein FsrB (an AgrB analog) as the mode of action for this compound. This conclusion was based on the impact of ambuic acid on reducing production of gelatinase biosynthesis-activating pheromone (GBAP [an AIP analog]) by E. faecalis and the reduced processing of FsrD (an AgrD analog) by FsrB (19). On the basis of the studies conducted by Nakayama and coworkers (19), we hypothesized that ambuic acid targets signal biosynthesis in S. aureus (Fig. 1). The challenge is that AIP signal biosynthesis is also regulated by quorum sensing, and to properly test this hypothesis, AIP production needs to be decoupled from regulation, a task that has not previously been accomplished. To accomplish this decoupling, the entire agr locus was deleted from a USA300 MRSA strain, and in the same strain, the agrBD genes (agr type I system) under regulation of the sarA P1 promoter were integrated at a phage attachment site (Fig. 1B). This mutant MRSA strain contains only the machinery involved with signal biosynthesis; therefore, AIP-I production by this strain should be selectively influenced by inhibitors that specifically target signal biosynthesis.

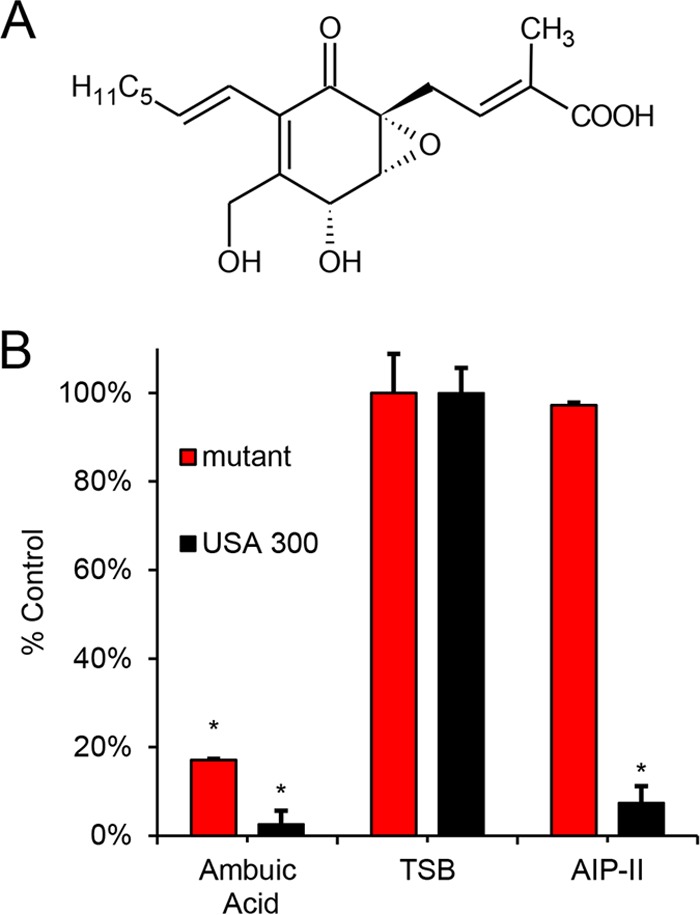

Mass spectrometric (MS) measurements of AIP-I production by a USA300 MRSA isolate and the mutant AIP-I constitutively producing strain strongly support signal biosynthesis inhibition as the mechanism of action for ambuic acid (Fig. 2). Both of these strains produce detectable levels of AIP-I in the absence of inhibitors, and the addition of ambuic acid inhibits AIP-I production for both strains of bacteria (Fig. 2). As a means of comparison, inhibition by the known receptor antagonist AIP-II was also measured. AIP-II is an AIP variant produced by some strains of S. aureus that competitively binds to AgrC, preventing activation by AIP-I (21). As expected, AIP-II inhibited AIP-I production by USA300 (Fig. 2), but importantly, production of AIP-I by the constitutively producing strain was unaffected by the addition of AIP-II (Fig. 2). Collectively, these findings demonstrate that ambuic acid operates as a signal biosynthesis inhibitor. It is important to note that the specific mechanism by which ambuic acid inhibits signal biosynthesis cannot be confirmed with these results. Detailed mechanistic investigations would be an interesting subject of further research.

FIG 2.

(A) Structure of ambuic acid. (B) Evaluation of AIP-I production in 16-h cultures of S. aureus strain AH1263, the LAC USA300 strain (black), and S. aureus strain AH2989, an engineered strain that constitutively produces AIP-I (red). Relative AIP-I production is shown in tryptic soy broth (TSB) and in the presence of 5 μM AIP-II, a known AgrC inhibitor, and 44 μM ambuic acid, a putative signal biosynthesis inhibitor. Statistical analyses were performed using the Student t test. An asterisk indicates a statistically significant difference between the treatment and control (TSB), with P < 0.01. The percentage of the control was calculated by dividing the AIP ion peak area detected by the mass spectrometer for the treatment by that of the relevant control (TSB). The optical density at 600 nm (OD600) was monitored over time for all doses tested here, and no growth delay or growth inhibition was observed (data not shown).

Ambuic acid inhibits virulence factor production and is specific to the agr system.

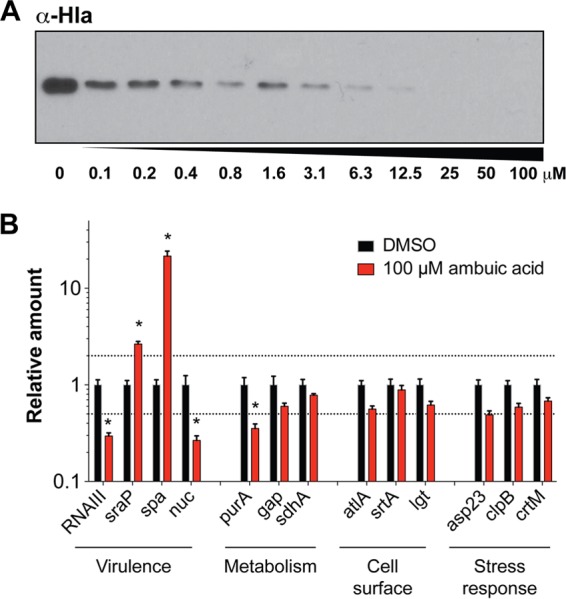

Our data (Fig. 2) suggest that ambuic acid functions as a quorum sensing inhibitor. Consistent with these findings, our recent report shows that ambuic acid inhibits the expression of the agr system in S. aureus at the transcriptional level (22). To further verify the action of this compound as a quorum sensing inhibitor, we sought to assess its impact on virulence factor production at the protein level. In a dose-response test, ambuic acid prevented alpha-toxin (Hla) production, as determined by Western blotting (Fig. 3A), verifying that exoprotein levels are indeed impacted. Next, to address the specificity of ambuic acid on S. aureus, we performed quantitative real-time PCR analysis on selected targets representing virulence factors, metabolism, cell surface components, and stress response. As anticipated, RNAIII levels significantly decreased and protein A (spa) levels increased in the presence of ambuic acid versus vehicle control (Fig. 3B), confirming the expected divergent response of these targets following agr system inhibition. No significant effects of ambuic acid were observed on stress response and cell surface components. Of the metabolic targets, purA levels decreased slightly in the presence of ambuic acid, while other targets were unaffected. For the other virulence factors, sraP levels slightly increased, while nuc levels decreased. Overall, the dominant impact of ambuic acid is repression of the agr quorum sensing system, demonstrating its specificity.

FIG 3.

Ambuic acid represses toxin production and shows specificity for the agr system. (A) Western blot of alpha-toxin (Hla) levels in response to increasing doses of ambuic acid. (B) Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis of relative expression of a variety of virulence, housekeeping, and stress response genes after treatment with 100 μM ambuic acid or DMSO. For each gene, expression was normalized to that of the DMSO control, and error bars represent the SEM from three biological replicates. Dashed lines indicate 2-fold cutoffs for change in expression. Bars marked with asterisks had a >2-fold change in expression when challenged with ambuic acid as determined by t tests on log-transformed data with a Holm-Sidak correction (P < 0.05).

Ambuic acid inhibits MRSA infection.

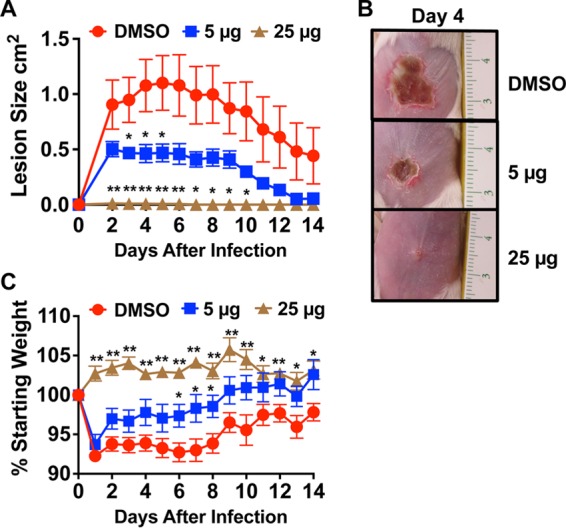

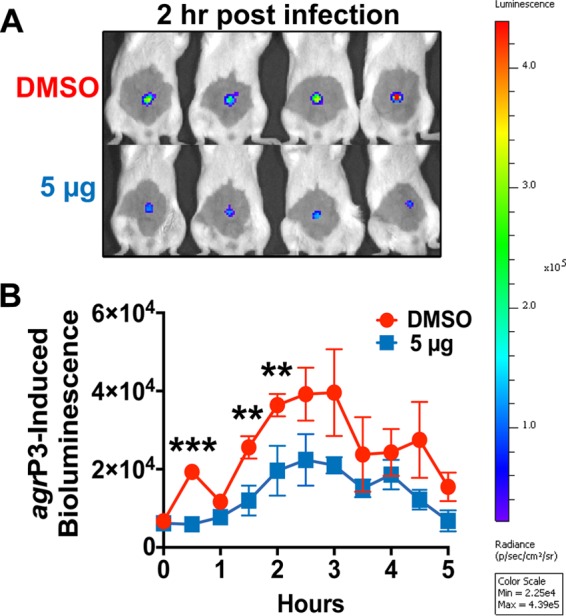

On the basis of the promising activity of ambuic acid in vitro, it was of interest to evaluate its efficacy in vivo in a skin model of MRSA infection. Using a murine model of intradermal MRSA challenge, a single dose of ambuic acid delivered at the time of infection was found to attenuate skin ulcer formation in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4). Ambuic acid delivered in this fashion did not elicit any overt signs of cutaneous injury or irritation (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material), indicating a lack of toxicity to the host. Ambuic acid-treated animals exhibited significantly less infection-induced morbidity (assessed by weight loss) than vehicle-treated controls. By challenging mice with a strain containing an agr-driven lux reporter, we show that the attenuation of MRSA virulence in ambuic acid-treated animals coincided with real-time suppression of agr activity (Fig. 5). Together, these data demonstrate that the ambuic acid-mediated attenuation of MRSA pathogenesis corresponds with potent quorum sensing inhibition both in vitro and in vivo.

FIG 4.

Ambuic acid attenuates MRSA-induced dermatopathology in a murine model of skin and soft tissue infection. BALB/c mice were intradermally injected with 1 × 108 CFU of LAC (USA300 isolate AH1263). Mice received a single dose of ambuic acid at 5 μg (blue squares) or 25 μg (brown triangles) or the vehicle control (DMSO [red circles]) at the time of infection. Significant differences between treatment and vehicle are represented by asterisks: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01. (A) Images of skin ulceration are shown from day 4 postinfection (scale in centimeters). (B) Ambuic acid reduces morbidity as assessed by measuring the weight of mice.

FIG 5.

Ambuic acid mediates quorum quenching in vivo. To determine if ambuic acid prevents activation of the quorum sensing system in vivo, mice were challenged intradermally with an agr-P3-lux reporter strain ± ambuic acid, and agr-driven bioluminescence was measured at the indicated time points via IVIS imaging. (A) Images were taken at 2 h postchallenge of vehicle (DMSO)- and ambuic acid (5 μg)-treated mice. (B) In vivo monitoring of quorum sensing was performed every 30 min and demonstrates that ambuic acid prevents quorum sensing signaling during infection even at the lower dose (5 μg). Significant differences between treatment at the lower dose and vehicle are represented by asterisks: **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

Ambuic acid inhibits quorum sensing in multiple bacterial pathogens.

The proposed advantage of signal biosynthesis as a target for quorum sensing inhibitors is the ability to broadly target virulence for multiple Gram-positive bacterial pathogens. In our studies, we sought to employ a recently developed quantitative mass spectrometric method (22) to compare 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) values of AIP inhibition for ambuic acid against multiple representative Gram-positive pathogenic bacterial isolates. As test organisms for this study, we chose four relevant species of Staphylococcus (S. aureus, S. epidermidis, S. lugdunensis, and S. saprophyticus). In addition, multiple agr types of S. aureus (types I to III) and S. epidermidis (types I to III) were evaluated. S. aureus agr type IV was not included in this evaluation due to its rarity among even large S. aureus collections (23). Finally, we also tested two other divergent Gram-positive pathogens, Listeria monocytogenes and Enterococcus faecalis.

As a first step toward quantitatively comparing quorum sensing inhibition against the various pathogens, it was necessary to detect their respective AIPs. AIP structures have previously been reported for all agr types of S. aureus (11, 24, 25), S. epidermidis (26), S. lugdunensis (25), and E. faecalis (27), and the results of our analyses with high-resolving-power mass spectrometry confirmed the structures reported in the literature. For S. saphrophyticus, AIP structures have never been reported, and mass spectrometry was employed to sequence the AIP from this organism. An ion with m/z 896.3971 was detected in an S. saphrophyticus culture, a value that corresponds to the [M+H]+ ion of the cyclic peptide Ile-Asn-Pro-c(Cys-Phe-Gly-Tyr-Thr), containing a thiolactone ring linked between the sulfhydryl group of the cysteine and the α-carboxyl group of the C-terminal threonine (calculated m/z, 896.39764; mass error, 2.6 ppm). Fragmentation of the peptide precursor resulted in product ions that agreed well with predicted fragmentation patterns for this peptide and with the fragmentation pattern for the synthetic peptide of the same structure (Fig. S1).

For L. monocytogenes, we detected an ion with m/z 699.29910 in spent medium. This value corresponds to the [M+H]+ ion of the cyclic peptide Ala-c(Cys-Phe-Met-Phe-Val), with a thiolactone ring linked between the sulfhydryl group of the cysteine and the α-carboxyl group of the C-terminal valine (calculated m/z, 699.29985; mass error, 1.5 ppm). Our proposed structure is one amino acid longer than a structure for the L. monocytogenes AIP recently suggested by Zetzmann et al. (28), c(Cys-Phe-Met-Phe-Val). We did not detect any ions corresponding to this shorter L. monocytogenes structure proposed in the Zetzmann report.

Once AIP structures had been determined, it was possible to employ quantitative measurements of AIP production to evaluate the IC50 for quorum sensing inhibition by ambuic acid for each pathogen (Table 1). As expected, ambuic acid inhibited AIP production for the majority of bacterial strains investigated (IC50 of <25 μM in 8 of the 11 strains). The most potent inhibition was observed against Enterococcus faecalis, for which an IC50 of 1.8 ± 0.7 μM was observed. Surprisingly, very little inhibition was observed for certain isolates of staphylococci that include S. lugdunensis agr type I and S. epidermidis agr types II and III (IC50s of >200 μM). Thus, it appears that the ability of ambuic acid to serve as a quorum sensing inhibitor is widespread among Gram-positive bacteria, but not universal.

TABLE 1.

IC50s of AIP inhibition for ambuic acid against multiple bacterial pathogens

| Strain | Agr type | IC50 (μM) | AIP sequencea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enterococcus faecalis AH3335 | NAb | 1.8 ± 0.7 | QNSPNIFGQWM |

| Listeria monocytogenesc LS1 | NA | 8.7 ± 0.2 | ACFMFV |

| Staphylococcus aureus | |||

| AH1263 | Type I | 2.5 ± 0.1 | YSTCDFIM |

| AH2623 | Type II | 23.6 ± 3.5 | GVNACSSLF |

| AH759 | Type III | 10.1 ± 0.3 | INCDFLL |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | |||

| 4804 | Type I | 15.1 ± 2.8 | DSVCASYF |

| 5183 | Type II | >200 | NASKYNPCSNYL |

| 5794 | Type III | >200 | NAAKYNPCASYL |

| Staphylococcus lugdunensis AH2160 | Type I | >200 | DICNAYF |

| Staphylococcus saprophyticusd AH2776 | NA | 2.6 ± 1.5 | INPCFGYT |

Underlined residues form the thiolactone or lactone ring with the C terminus.

NA, not applicable.

The proposed L. monocytogenes AIP structure, which was solved based on accurate mass and fragmentation spectra of an ion detected directly from an L. monocytogenes culture, conflicts with that recently proposed in the literature (28).

The S. saphrophyticus AIP was identified for the first time in this work.

DISCUSSION

One of the advantages of an ideal antivirulence agent would be the ability to selectively target the most problematic pathogens, such as MRSA, while demonstrating little impact on the resident microbiome (29). There is growing appreciation that a healthy microbiome is important for the prevention of bacterial infections (30). Antibiotics often cause unintended collateral damage to the resident flora, leading to adverse outcomes for the patient and potential secondary infections by resistant pathogens (31). Relevant to the findings presented here, S. epidermidis and S. lugdunensis are both commensal bacteria that are known to have beneficial properties in averting S. aureus and MRSA colonization (32, 33), an important determinant of subsequent infection (34). In this study (Table 1), S. lugdunensis and two of the three subtypes of S. epidermidis showed little response when challenged with ambuic acid, while all types of S. aureus were strongly inhibited. Thus, ambuic acid shows promise as a lead compound that demonstrates the desired selectivity against the most problematic pathogens, although further studies are needed to fully explore its resistance profile against commensal bacteria.

The mechanism whereby certain commensals remain resistant to ambuic acid is currently unknown. The role of AgrB in signal biosynthesis inhibition raises the question as to whether differences in AgrB structure might lead to this resistance, but comparison of AgrB sequences among the various strains tested (Table 1) yielded no obvious trends. The source of resistance could certainly yield insights into the mechanism by which ambuic acid inhibits signal biosynthesis and would be a worthy topic of further investigation.

Our work addresses for the first time the question of the specificity with which ambuic acid targets the agr quorum sensing system. The dominant effect of treatment with ambuic acid, as indicated in Fig. 2, is downregulation of several genes specifically controlled by the agr system. Minor off-target effects were observed, notably on nuc expression, potentially suggesting other two-component systems, such as the Sae system (35), might be also modestly impacted by ambuic acid.

Our studies demonstrate that ambuic acid is effective at preventing MRSA-induced tissue injury in a mouse model of skin infection. Using an agr-driven P3-lux reporter, the real-time kinetics of quorum sensing activation in response to ambuic acid can be tracked in vivo during infection. Based on previous studies by Wright et al. (36), the first 4 h of infection is critical to assess the functional status of the agr system, and the level of induction correlates to the extent of dermatopathology that will occur. We selected this key time period to monitor the kinetics of ambuic acid inhibition on MRSA agr activity in vivo (Fig. 5) and observed significant quenching of the P3-lux response in the first several hours of infection from a single 5-μg dose. Our work further establishes the utility of the P3-lux reporter as a means of investigating the mechanism of other quorum sensing inhibitors in vivo.

Another important contribution of this work is the application of mass spectrometric measurements to confirm structures of AIPs produced by a number of Gram-positive bacteria (Table 1). We report for the first time a structure of the S. saphrophyticus AIP and verify a number of reported AIP structures for other bacteria. The one case in which our AIP measurements do not agree with the literature is for the L. monocytogenes AIP, which was proposed by the Zetzmann et al. (28) to be a cyclic pentapeptide, c(Cys-Phe-Met-Phe-Val), but detected in our studies to be a hexapeptide with an alanine N-terminal extension from the same cyclic macrocycle Ala-c(Cys-Phe-Met-Phe-Val). It should be noted that the identical hexapeptide that we propose as the L. monocytogenes AIP was detected in spent medium from the related species Listeria innocua (19). Zetzmann et al. based their AIP structure assignment on synthesizing various potential signal structures and using reporter strains to identify the most potent inducer. Our study employed a more direct method by detecting the native peptide from the L. monocytogenes bacterial culture medium. Collectively, our data showing accurate mass and fragmentation patterns of the hexapeptide AIP structure, combined with the observation that AIP levels were reduced in the presence of a known signal biosynthesis inhibitor (ambuic acid), suggest correct identification of the L. monocytogenes AIP under the conditions employed here. It is possible that under alternative growth conditions, the N-terminal alanine is removed by an aminopeptidase or some other protease, leading to the pentapeptide identified by Zetzmann et al.

Collectively, our results demonstrate tremendous promise of ambuic acid as a lead compound for therapeutic development against diverse Gram-positive bacterial pathogens. We show that this compound selectively targets AIP signal biosynthesis in MRSA, both in vitro and in vivo, which translates to efficacy against skin infections. We also demonstrate that ambuic acid has potent activity against multiple other bacterial pathogens in vitro, suggesting it could be a broad-spectrum agent. Of further import, ambuic acid has limited impact on several commensal staphylococci. However, there are some commensals that remain susceptible to inhibition. Our results are relevant to the emerging field of antivirulence because they demonstrate that quorum sensing signal biosynthesis is a promising target. The assay developed herein could also be used in future screening efforts to identify signal biosynthesis inhibitors from compound libraries.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Instrumentation.

Optical density (OD) was measured using a Synergy H1 multimode reader (Biotek Instruments, Inc., Winooski, VT). Unless otherwise stated, liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) analyses were performed using an Aquity ultrahigh-performance liquid chromatography (UPLC) system (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA) coupled to a Q Exactive Plus hybrid quadrupole-Orbitrap mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). All solvents used for chemical analyses were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA).

Bacterial strains, media, and growth conditions.

Information regarding bacterial strains used in this study is listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. Strains AH3335 and LS1 were maintained in brain heart infusion broth (Teknova, Hollister, CA). All other strains were maintained in tryptic soy broth (TSB [Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO]).

Engineering of strain (AH2989) constitutively producing AIP.

Strain AH2989 was constructed in a series of steps. Initially, the sarA P1 promoter was amplified by PCR from the AH1263 genome using oligonucleotides ARH120 and CLM607. (For this and other primer sequences, see Table S2 in the supplemental material.) The PCR product was purified, digested with HindIII and XbaI, and cloned into plasmid pLL29 (37). Next, the agrBD genes from AH1263 (agr type I) were amplified by PCR using CLM608 and CLM606. The PCR product was purified, digested with XbaI and EcoRI, and cloned into pLL29 downstream of the sarA P1 promoter. Plasmid pLL29 with the sarA P1 promoter driving agrBD was integrated into RN4220 using the protocol previously described (37). The integrated construct was crossed by 80α phage transduction into AH1263 by selecting for tetracycline resistance. The Δagr::TetM construct was subsequently crossed from AH1292 into this strain by selecting for minocycline resistance, which is conferred by the TetM marker.

Identification of autoinducing peptides (AIPs) and measurement of AIP inhibition.

Single isolated colonies of each bacterial strain were grown overnight at 37°C. Overnight cultures were diluted 1:200 (bacterial culture to broth) and shaken for 16 h at 200 rpm and 37°C. Cells were pelleted by centrifugation at 6,000 × g for 5 min and removed by 0.22-μm-pore filtration. AIP was detected directly from spent medium filtrate using liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS). LC-MS analyses to quantify AIP were conducted using a previously published method (22).

Mass spectra were collected using two scan events. The first scan event was a positive-mode full scan with a mass range from 300 to 2,000 and a resolution of 70,000. The second scan event was positive-mode selected ion monitoring for the calculated mass of the predicted/identified AIP with an isolation window of 1 atomic mass unit (amu). Predicted m/z values were determined by using the known AgrD sequence as a guide. Starting with an initial 8-residue sequence, amino acid residues were added and subtracted from the N terminus. The mass spectrometer was operated using a heated electrospray ionization source with the capillary temperature set at 300°C, S-Lens RF level set at 80, spray voltage set at 4.0 kV, sheath gas flow set at 50 (arbitrary units), and auxiliary gas flow set at 15. Fragmentation spectra were employed to confirm the structures of the AIPs from L. monocytogenes and S. saphrophyticus, as described previously (22). Data and methods used to confirm these structures are provided in Fig. S1 and S2 in the supplemental material.

Western blot analysis and RNA purification.

Western blots for alpha-toxin were performed as previously described (38). To purify RNA, overnight cultures were diluted 1:100 in triplicate in TSB supplemented with either 100 μM ambuic acid or 0.35% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) as a vehicle control and grown for 6 h in a 48-well plate at 37°C with shaking at 750 rpm in a Stuart incubator. Cells were pelleted and washed briefly with RNAprotect bacterial reagent (Qiagen) before lysing with lysostaphin for 1 h at room temperature. RNA was purified using the RNeasy minikit (Qiagen), and genomic DNA was removed using the Turbo DNA free kit (Ambion).

qRT-PCR.

DNase-treated RNA was used as a template to generate cDNA with an Applied Biosystems high-capacity reverse transcription kit. Primers were designed using the PrimerQuest tool on the IDT website (for primer sequences, see Table S2). Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed using iTaq Universal SYBR green Supermix (Bio-Rad) on a CFX96 real-time thermocycler (Bio-Rad) under the following conditions: 3 min at 95°C, 40 cycles of 15 s at 95°C and 30 s at 55°C, followed by a dissociation curve. Expression was normalized to that of DNA gyrase (gyrB), and then for each primer set, expression was normalized to the DMSO control. Values represent the average and standard error of the mean (SEM) from three biological replicates. Statistical significance was determined using GraphPad Prism by t test of log-transformed data with a Holm-Sidak correction for multiple t tests.

Mice and S. aureus skin challenge model.

Male BALB/c mice were purchased from Charles River (Wilmington, MA) and allowed to acclimate to the biosafety level 2 (BSL2) animal housing facility at the University of Iowa (Iowa City, IA) for at least 7 days prior to their inclusion in this study. All animal studies described herein were performed in accordance with the recommendations of the Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Iowa (protocol no. 5051384). At day 0, age-matched mice were anesthetized with isoflurane, abdominal skin was carefully shaved with an Accu-Edge microtome blade (Sakura-Finnetek, Torrance, CA), and exposed skin was cleansed by wiping with an alcohol prep pad (Covidien, Mansfield, MA). To prepare inoculum for assessing MRSA virulence following skin challenge, a USA300 MRSA strain (LAC) was grown in TSB medium overnight at 37°C in a shaking incubator set to 200 rpm. Overnight cultures were diluted 1:100 TSB and subcultured to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.5 (≈2 h). Bacterial cells were the pelleted and resuspended in sterile saline. Inoculum suspensions (50 μl) containing 1 × 108 CFU bacteria and either ambuic acid (5, 25, or 50 μg diluted in neat DMSO) or DMSO alone were injected intradermally into abdominal skin using a 0.3-ml, 31-gauge insulin syringe (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ). Baseline body weights of mice were measured before infection and every day thereafter for a period of 14 days. For determination of lesion size, digital photos of skin lesions were taken daily with a Canon Rebel Powershot (ELPH 330 HS) and analyzed via ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health Research Services Branch, Bethesda, MD). To assess quorum quenching in vivo, the inoculum was prepared from a LAC reporter strain of MRSA engineered to couple agr activation with bioluminescence, agr-P3-lux (AH2759). The culture was grown in TSB medium plus chloramphenicol overnight at 37°C in a shaking incubator set to 200 rpm (39). Overnight cultures were diluted 1:100 in TSB plus chloramphenicol and subcultured to an OD600 of 0.1 (≈1 h). Bacterial cells were the pelleted and resuspended in sterile saline to a concentration of 1 × 107 CFU/45 μl. Inoculum suspensions (50 μl) containing 1 × 107 CFU and either 5 μg or 25 μg of ambuic acid diluted in neat DMSO or DMSO alone were injected intradermally into abdominal skin using a 0.3-ml, 31-gauge insulin syringe. As a technical control, several mice were injected in the same manner with 50 μl of sterile saline only. For all infections, the challenge dose was confirmed by plating serial dilutions of inoculum on tryptic soy agar (TSA) and counting ensuing colonies after overnight culture. For animals administered the DMSO control or 5 μg ambuic acid as part of inoculum suspension, n ≥ 5 mice/group.

Measurement of quorum quenching in vivo.

Beginning immediately after infection, mice were imaged under isoflurane inhalation anesthesia (2%). Photons emitted from luminescent bacteria were collected during a 2-min exposure using the Xenogen IVIS imaging system and Living Image software (Xenogen, Alameda, CA). Bioluminescent image data are presented on a pseudocolor scale (blue representing least intense and red representing the most intense signal) overlaid onto a grayscale photographic image. Using the image analysis tools in Living Image software, circular analysis windows (of uniform area) were overlaid onto abdominal regions of interest (as depicted in Fig. 5), and the corresponding bioluminescence values (photons per second per square centimeter per steradian) were measured and plotted versus time after infection. Data are representative of two independent experiments. For animals administered DMSO control or 5 μg ambuic acid as part of inoculum suspension, n = 8 mice/group. For animals administered 25 μg ambuic acid as part of the inoculum suspension, n = 4 mice/group.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to David Zich for technical assistance. Mass spectrometry data were collected in the Triad Mass Spectrometry Facility.

Research reported in this publication was supported in part by the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, a Center of the National Institutes of Health, under award no. R01 AT006860 to N.B.C and A.R.H. C.P.P. was supported by NIH T32 awards AI007511 and AI007343. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. A.R.H. was also supported by a Merit Award (I01 BX002711) from the Department of Veteran Affairs. The funders had no role in study design, data collection or interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.00263-17.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2013. Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States, 2013. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA: http://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/pdf/ar-threats-2013-508.pdf Accessed 25 January 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dantes R, Mu Y, Belflower R, Aragon D, Dumyati G, Harrison LH, Lessa FC, Lynfield R, Nadle J, Petit S, Ray SM, Schaffner W, Townes J, Fridkin S, Emerging Infections Program—Active Bacterial Core Surveillance MRSA Surveillance Investigators. 2013. National burden of invasive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections, United States, 2011. JAMA Intern Med 173:1970–1978. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.10423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Powers JH. 2004. Antimicrobial drug development—the past, the present, and the future. Clin Microbiol Infect 10(Suppl 4):S23–S31. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-0691.2004.1007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ventola CL. 2015. The antibiotic resistance crisis: part 1: causes and threats. PT 40:277–283. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spellberg B, Bartlett JG, Gilbert DN. 2013. The future of antibiotics and resistance. N Engl J Med 368:299–302. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1215093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rasko DA, Sperandio V. 2010. Anti-virulence strategies to combat bacteria-mediated disease. Nat Rev Drug Discov 9:117–128. doi: 10.1038/nrd3013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sully EK, Malachowa N, Elmore BO, Alexander SM, Femling JK, Gray BM, DeLeo FR, Otto M, Cheung AL, Edwards BS, Sklar LA, Horswill AR, Hall PR, Gresham HD. 2014. Selective chemical inhibition of agr quorum sensing in Staphylococcus aureus promotes host defense with minimal impact on resistance. PLoS Pathog 10:e1004174. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Daly SM, Elmore BO, Kavanaugh JS, Triplett KD, Figueroa M, Raja HA, El-Elimat T, Crosby HA, Femling JK, Cech NB, Horswill AR, Oberlies NH, Hall PR. 2015. ω-Hydroxyemodin limits Staphylococcus aureus quorum sensing-mediated pathogenesis and inflammation. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:2223–2235. doi: 10.1128/AAC.04564-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harjai K, Kumar R, Singh S. 2010. Garlic blocks quorum sensing and attenuates the virulence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 58:161–168. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2009.00614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhu J, Kaufmann GF. 2013. Quo vadis quorum quenching? Curr Opin Pharmacol 13:688–698. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2013.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thoendel M, Kavanaugh JS, Flack CE, Horswill AR. 2011. Peptide signaling in the staphylococci. Chem Rev 111:117–151. doi: 10.1021/cr100370n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murray EJ, Crowley RC, Truman A, Clarke SR, Cottam JA, Jadhav GP, Steele VR, O'Shea P, Lindholm C, Cockayne A, Chhabra SR, Chan WC, Williams P. 2014. Targeting Staphylococcus aureus quorum sensing with nonpeptidic small molecule inhibitors. J Med Chem 57:2813–2819. doi: 10.1021/jm500215s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.George EA, Novick RP, Muir TW. 2008. Cyclic peptide inhibitors of staphylococcal virulence prepared by Fmoc-based thiolactone peptide synthesis. J Am Chem Soc 130:4914–4924. doi: 10.1021/ja711126e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Otto M, Sussmuth R, Vuong C, Jung G, Gotz F. 1999. Inhibition of virulence factor expression in Staphylococcus aureus by the Staphylococcus epidermidis agr pheromone and derivatives. FEBS Lett 450:257–262. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(99)00514-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tal-Gan Y, Stacy DM, Foegen MK, Koenig DW, Blackwell HE. 2013. Highly potent inhibitors of quorum sensing in Staphylococcus aureus revealed through a systematic synthetic study of the group-III autoinducing peptide. J Am Chem Soc 135:7869–7882. doi: 10.1021/ja3112115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gordon CP, Williams P, Chan WC. 2013. Attenuating Staphylococcus aureus virulence gene regulation: a medicinal chemistry perspective. J Med Chem 56:1389–1404. doi: 10.1021/jm3014635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Somerville GA, Beres SB, Fitzgerald JR, DeLeo FR, Cole RL, Hoff JS, Musser JM. 2002. In vitro serial passage of Staphylococcus aureus: changes in physiology, virulence factor production, and agr nucleotide sequence. J Bacteriol 184:1430–1437. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.5.1430-1437.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cech NB, Horswill AR. 2013. Small-molecule quorum quenchers to prevent Staphylococcus aureus infection. Future Microbiol 8:1511–1514. doi: 10.2217/fmb.13.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakayama J, Uemura Y, Nishiguchi K, Yoshimura N, Igarashi Y, Sonomoto K. 2009. Ambuic acid inhibits the biosynthesis of cyclic peptide quormones in Gram-positive bacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 53:580–586. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00995-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li JY, Harper JK, Grant DM, Tombe BO, Bashyal B, Hess WM, Strobel GA. 2001. Ambuic acid, a highly functionalized cyclohexenone with antifungal activity from Pestalotiopsis spp. and Monochaetia sp. Phytochemistry 56:463–468. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(00)00408-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mayville P, Ji GY, Beavis R, Yang HM, Goger M, Novick RP, Muir TW. 1999. Structure-activity analysis of synthetic autoinducing thiolactone peptides from Staphylococcus aureus responsible for virulence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96:1218–1223. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.4.1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Todd DA, Zich DB, Ettefagh KA, Kavanaugh JS, Horswill AR, Cech NB. 2016. Hybrid quadrupole-Orbitrap mass spectrometry for quantitative measurement of quorum sensing inhibition. J Microbiol Methods 127:89–94. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2016.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shopsin B, Mathema B, Alcabes P, Said-Salim B, Lina G, Matsuka A, Martinez J, Kreiswirth BN. 2003. Prevalence of agr specificity groups among Staphylococcus aureus strains colonizing children and their guardians. J Clin Microbiol 41:456–459. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.1.456-459.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ji G, Beavis RC, Novick RP. 1995. Cell density control of staphylococcal virulence mediated by an octapeptide pheromone. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 92:12055–12059. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.26.12055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Novick RP, Muir TW. 1999. Virulence gene regulation by peptides in staphylococci and other Gram-positive bacteria. Curr Opin Microbiol 2:40–45. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5274(99)80007-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Olson ME, Todd DA, Schaeffer CR, Paharik AE, Van Dyke MJ, Büttner H, Dunman PM, Rohde H, Cech NB, Fey PD, Horswill AR. 2014. Staphylococcus epidermidis agr quorum-sensing system: signal identification, cross talk, and importance in colonization. J Bacteriol 196:3482–3493. doi: 10.1128/JB.01882-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakayama J, Cao Y, Horii T, Sakuda S, Akkermans AD, de Vos WM, Nagasawa H. 2001. Gelatinase biosynthesis-activating pheromone: a peptide lactone that mediates a quorum sensing in Enterococcus faecalis. Mol Microbiol 41:145–154. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02486.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zetzmann M, Sánchez-Kopper A, Waidmann MS, Blombach B, Riedel CU. 2016. Identification of the agr peptide of Listeria monocytogenes. Front Microbiol 7:989. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blaser M. 2011. Antibiotic overuse: stop the killing of beneficial bacteria. Nature 476:393–394. doi: 10.1038/476393a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van Rensburg JJ, Lin H, Gao X, Toh E, Fortney KR, Ellinger S, Zwickl B, Janowicz DM, Katz BP, Nelson DE, Dong Q, Spinola SM. 2015. The human skin microbiome associates with the outcome of and is influenced by bacterial infection. mBio 6:e01315-15. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01315-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Langdon A, Crook N, Dantas G. 2016. The effects of antibiotics on the microbiome throughout development and alternative approaches for therapeutic modulation. Genome Med 8:39. doi: 10.1186/s13073-016-0294-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Iwase T, Uehara Y, Shinji H, Tajima A, Seo H, Takada K, Agata T, Mizunoe Y. 2010. Staphylococcus epidermidis Esp inhibits Staphylococcus aureus biofilm formation and nasal colonization. Nature 465:346–349. doi: 10.1038/nature09074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zipperer A, Konnerth MC, Laux C, Berscheid A, Janek D, Weidenmaier C, Burian M, Schilling NA, Slavetinsky C, Marschal M, Willmann M, Kalbacher H, Schittek B, Brötz-Oesterhelt H, Grond S, Peschel A, Krismer B. 2016. Human commensals producing a novel antibiotic impair pathogen colonization. Nature 535:511–516. doi: 10.1038/nature18634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dryden MS. 2010. Complicated skin and soft tissue infection. J Antimicrob Chemother 65(Suppl 3):iii35–iii44. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Olson ME, Nygaard TK, Ackermann L, Watkins RL, Zurek OW, Pallister KB, Griffith S, Kiedrowski MR, Flack CE, Kavanaugh JS, Kreiswirth BN, Horswill AR, Voyich JM. 2013. Staphylococcus aureus nuclease is an SaeRS-dependent virulence factor. Infect Immun 81:1316–1324. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01242-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wright JS, Jin R, Novick RP. 2005. Transient interference with staphylococcal quorum sensing blocks abscess formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102:1691–1696. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407661102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Luong TT, Lee CY. 2007. Improved single-copy integration vectors for Staphylococcus aureus. J Microbiol Methods 70:186–190. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2007.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Quave CL, Lyles JT, Kavanaugh JS, Nelson K, Parlet CP, Crosby HA, Heilmann KP, Horswill AR. 2015. Castanea sativa (European Chestnut) leaf extracts rich in ursene and oleanene derivatives block Staphylococcus aureus virulence and pathogenesis without detectable resistance. PLoS One 10:e0136486. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0136486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Figueroa M, Jarmusch AK, Raja HA, El-Elimat T, Kavanaugh JS, Horswill AR, Cooks RG, Cech NB, Oberlies NH. 2014. Polyhydroxyanthraquinones as quorum sensing inhibitors from the guttates of Penicillium restrictum and their analysis by desorption electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. J Nat Prod 77:1351–1358. doi: 10.1021/np5000704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.