Abstract

ERα17p is a peptide corresponding to the sequence P295LMIKRSKKNSLALSLT311 of the estrogen receptor alpha (ERα) and initially found to interfere with ERα‐related calmodulin binding. ERα17p was subsequently found to elicit estrogenic responses in E2‐deprived ERα‐positive breast cancer cells, increasing proliferation and ERE‐dependent gene transcription. Surprisingly, in E2‐supplemented media, ERα17p‐induced apoptosis and modified the actin network, influencing cell motility. Here, we report that ERα17p internalizes in breast cancer cells (T47D, MDA‐MB‐231, SKBR3) and induces a massive early (3 h) transcriptional activity. Remarkably, about 75% of significantly modified transcripts were also modified by E2, confirming the pro‐estrogenic profile of ERα17p. The different ER spectra of the used cell lines allowed us to identify a specific ERα17p signature related to ERα as well as its variant ERα36. With respect to ERα, the peptide activates nuclear (cell cycle, cell proliferation, nucleic acid and protein synthesis) and extranuclear signaling pathways. In contrast, through ERα36, it mainly triggers inhibitory actions on inflammation. This is the first work reporting a detailed ERα36‐specific transcriptional signature. In addition, we report that ERα17p‐induced transcripts related to apoptosis and actin modifying effects of the peptide are independent from its estrogen receptor(s)‐related actions. We discuss our findings in view of the potential use of ERα17p as a selective peptidomimetic estrogen receptor modulator (PERM).

Keywords: Estrogen receptor; Estrogen receptor alpha isoforms (ERα, ERα36); Breast cancer cell lines (T47D, MDA-MB-231, SKBR3); Transcriptome analysis; ERα17p

Highlights

-

►

A peptide issued from the ERα P295LMIKRSKKNSLALSLT311 structure (ERα17p) is investigated.

-

►

ERα17p internalizes in breast cancer cells, independently of the presence of ERα.

-

►

ERα17p induces a massive early transcription in breast cancer cell lines.

-

►

∼75% of transcripts are common with E2. Non‐E2‐related actions include apoptosis and migration.

-

►

ERα and ERα36 estrogenic transcriptional effects are opposite.

1. Introduction

Estrogen receptor alpha (ERα) is the major target of breast cancer endocrine therapy. Except for aromatase inhibitors, responsible for deprivation of the endogenous ligand by inhibiting the formation of 17β‐estradiol (E2), the majority of endocrine disruptors used in daily practice act as pure ER‐antagonists, partial agonists or mixed agonists/antagonists, depending on their structure and cell type (see Ali and Coombes, 2002; Jordan, 2002; Peng et al., 2009, for reviews). Despite a significant progress in breast cancer treatment, patient survival and quality of life, the emergence of resistance to endocrine therapy still remains a major therapeutic challenge. In such a context, a better understanding of the mechanism(s) involved in receptor function appears necessary. Accordingly, the identification of alternative receptor interaction sites that could lead to the development of new classes of specific endocrine disruptors has gained interest (Leclercq et al., 2006; Sengupta and Jordan, 2008). For example, the potential therapeutic value of peptides containing a canonical LxxLL motif, usually found at the surface of coactivators required for ERα‐mediated transcriptions (see Savkur and Burris, 2004, for review), is now under investigation (Houtman et al., 2012; Leduc et al., 2003; Rodriguez et al., 2004).

Recently, we have synthesized a 17‐mer peptide (H‐PLMIKRSKKNSLALSLT‐OH, ERα17p) corresponding to the P295‐T311 sequence of ERα and located between its hinge (D) and Ligand Binding (E) domains, in the autonomous activation function AF‐2a (Jacquot and Leclercq, 2009). This P295‐T311 ERα sequence is an important platform for various post‐translational modifications of the receptor as well as its association with calmodulin (Gallo et al., 2008). ERα mutants lacking this motif exhibit constitutive transcriptional activity, which is relevant to more aggressive phenotypes and resistance to aromatase inhibitors (Barone et al., 2010).

ERα17p was found to selectively enhance the proliferation of ERα‐positive breast cancer cells (Gallo et al., 2007a), in steroid‐deprived media, through ERα, as its action was reverted by antiestrogens (Gallo et al., 2008). Moreover, ERα17p decreased ERα intracellular concentration without affecting its affinity for E2 (Gallo et al., 2008, 2007a), an effect previously attributed to conventional ERα ligands (Laios et al., 2005; Seo et al., 2006). This down‐regulation was due to an enhanced proteasomal degradation of the receptor (Gallo et al., 2008), as well as to a decreased transcription of ERα mRNA and neosynthesis of the receptor protein, after prolonged incubation (Gallo et al., 2008), as was previously reported for E2 (Leclercq et al., 2006). In addition, ERα17p enhanced the transcription of two ER‐dependent genes (PR, Ps2, Gallo et al., 2007a), an action not further enhanced in the presence of E2 (Gallo et al., 2007b). In fact, ERα17p could induce agonistic conformational modifications of the receptor, rendering the E2‐binding pocket inaccessible to ligands (Gallo et al., 2007b). Accordingly, when associated with ERα, ERα17p modulated the receptor association with LxxLL‐bearing receptor coactivators (Gallo et al., 2007b).

On the contrary, in E2‐containing medium, ERα17p induced apoptosis of breast cancer cells and regression of human breast cancer cell xenografts in mice (Pelekanou et al., 2011a). Moreover, it modified actin cytoskeleton dynamics and migration characteristics, implicated in the metastatic potential of breast tumors (Kampa et al., 2011). These latter actions occurred independently of the presence of ERα, suggesting the existence of an alternative (ER‐independent) mode of action of the peptide. Additionally, ERα17p associated with the plasma membrane and enhanced the binding of BSA‐conjugated (membrane‐impermeable) steroids, without directly competing with their membrane‐binding sites (Kampa et al., 2011; Pelekanou et al., 2011a). All these data concur to the concept that ERα17p is a multifaceted peptide regulator devoted to multiple actions in breast cancer cells. Some of these actions are clearly mediated through ERα, while others are not, while internalization of the peptide into living cells has been evidenced, suggesting several novel possibilities for its action (Byrne et al., 2012).

The present work further deciphers and analyzes the action of ERα17p, and confirms its internalization into different breast cancer cell lines, with distinct ER profiles. In addition, we report that ERα17p induces early transcriptional effects (3 h) that are both ER‐dependent and ER‐independent. The interaction of the peptide with specific isoforms of ERα (ERα66, ERα36) is also examined in detail.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cell lines and chemicals

The human breast cancer cell lines T47D and MDA‐MB‐231 were obtained from DSMZ (Braunschweig, Germany) while SKBR3 cell were obtained from ATCC‐LGC Standards (Wesel, Germany). T47D and MDA‐MB‐231 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 and SKBR3 cells in McCoy's medium, supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, at 37 °C, with 5% CO2. All chemicals were purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MO), unless stated otherwise. All culture materials were from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, USA). The ERα17p peptide (sequence: H‐PLMIKRSKKNSLALSLT‐OH) was synthesized by solid phase peptide synthesis (Eurogentec, Seraing, Belgium), as previously described (Gallo et al., 2007b). P[4,5(n)‐3H‐Leu]MIKRSKKNSLALSLT‐OH ([3H]ERα17p, Specific Activity 78 Ci/mmol) was synthesized by Cambridge Research Biochemicals (CRB, Billingham, UK).

2.2. Uptake of [3H]ERα17p by cells

Cells were detached from culture flasks by trypsin, washed once with PBS and suspended in serum‐free medium containing low bicarbonate (0.35 g/L), pH 7.4. Cells (100,000 in a total volume of 400 μl) were incubated with [3H]ERα17p (50,000 cpm/tube, 1.2 μM) at 37 °C for different time intervals (1, 3, 6, 24 h), in triplicate. At the end of the incubation period, cells were pelleted by centrifugation (15 s, 6000 g) and washed twice with PBS containing 1 mg/ml BSA. Afterwards, they were lysed by sonication and centrifuged (2 min, 13,000 g) in order to separate the internalized radioactivity, in the supernatant. Each supernatant was mixed with 3 ml scintillation cocktail (SigmaFluor, Sigma, St Louis, MO) and radioactivity was counted in a scintillation counter (Tricarb, Series 4000, Packard), with a 60% efficiency for Tritium. The integrity of the internalized peptide was verified by thin layer chromatography on a C‐18 support, developed with 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid in acetonitrile.

2.3. Cell cycle analysis

One million ERα17p treated (10−6 Μ) and control cells were centrifuged (2000 rpm, 5 min) and the pellet was suspended in 100 μl ice cold 70% ethanol. After incubation of cells for 1 h at 4 °C, 1 ml of PBS was added, followed by centrifugation (2000 rpm, 5 min). The pellet was re‐suspended in 1 ml PBS and incubated with 100 μl RNAse A (1 mg/ml) for 1 h at 37 °C. Then, 10 μl propidium iodide (1 mg/ml in PBS) were added and the cells were incubated for 10 min in the dark at room temperature. FACS analysis was performed with the Attune ® Acoustic Focusing Cytometer (Applied Biosystems, Life Technologies) within 3 h after the addition of propidium iodide. Data were analyzed with the Attune program and verified with the Cyflogic (CyFlo Ltd, Turku, Finland).

2.4. Quantitative real‐time PCR

Quantitative real‐time PCR was performed as described previously (Notas et al., 2011). Primers were selected from qPrimer Depot (http://primerdepot.nci.nih.gov) (Supplemental Table 1) and synthesized by VBC Biotech (Vienna, Austria). Changes were normalized according to 18S RNA expression.

2.5. Whole transcriptome assay and analysis

After a 4 h incubation in a medium containing 10% charcoal stripped FBS, cells were incubated in the same conditions with or without equimolar concentrations of ERα17p (10−6 M) or E2 for 3 h. Total RNA was isolated using Nucleospin II columns (Macherey–Nagel, Dttren, Germany), following the manufacturer's instructions. RNA was labeled and hybridized according to the Affymetrix protocol (Affymetrix Gene‐Chip Expression Analysis Technical Manual), using the HGU133A plus 2 chip, analyzing a total of 54675 transcripts. Signals were detected by an Affymetrix microarray chip reader. Gene array data have been stored at the NIH Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) repository (Accession No. GSE39721). Normalization was performed with the raw data using Genespring GX V11.0 (Agilent, Foster City, CA). Any transcript modified by at least a factor of 1.5 in either direction (ERα17p/vehicle, E2/vehicle) were extracted and analyzed. Gene Ontology (GO) terms analysis and grouping were performed with the online resource REVIGO (Supek et al., 2011). Gene lists were further analyzed with the Gene Set Enrichment Analysis resource (GSEA, http://www.broadinstitute.org/gsea/index.jsp, Mootha et al., 2003; Subramanian et al., 2005). Modified gene lists were further analyzed for specific function and pathways. Furthermore, this signed list (separate for up‐ and down‐regulated genes) was introduced to the web resource TFactS (www.tfacts.org, Essaghir et al., 2010) for the detection of significantly modified transcription factors.

2.6. Statistical analysis

Statistics were performed with the PASW v 20.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL) program. A statistical threshold of 0.05 was retained for significance.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. ERα17p internalizes into breast cancer cells, independently of the presence of ERα

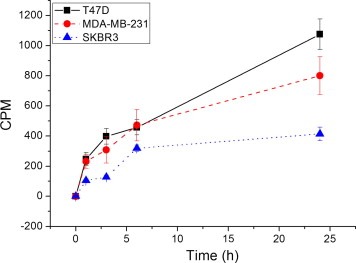

Previous data, carried out by MALDI‐TOFF mass spectrometry on CHO cells (devoid of any ER) incubated with 10 μM of ERα17p for 75 min, revealed a weak internalization of the peptide (Byrne et al., 2012), achieving an intracellular concentration of ∼200 nM. Here, we have used a tritiated analog of ERα17p and three breast cancer cell lines expressing distinct, well‐defined, ER profiles (Notas et al., 2011; Pelekanou et al., 2011a), i.e., T47D (ERα‐, ERβ‐, ERα46‐, ERα36‐ and GPR30‐positive), MDA‐MB‐231 (ERβ‐, ERα46‐, ERα36‐ and GPR30‐positive) and SKBR3 (ERα36‐ and GPR30‐positive). When cells were incubated with 1.2 μM (50,000 cpm) [3H]ERα17p for 1–24 h in a serum‐free medium, internalization occurred within the first hour, increasing thereafter until 24 h (Figure 1). Between 3% (1 h) and 8% (24 h) of intact tritiated peptide was internalized, independently of the presence of ERα. Hence, using such an extracellular concentration of peptide, one may attain an intracellular concentration above 40 nM after 3 h of incubation, which is sufficient to initiate specific intracellular effects. This ERα17p internalization occurred in cell lines that express a diverse profile of ERs (including ERα devoid cell lines MDA‐MB‐231 and SKBR3), suggesting that the net intracellular concentration of the peptide sums its intracellular (free or transporter‐mediated) movement and its internalization possibly via membrane‐related estrogen receptors. A more detailed study of ERα17p internalization is actually under investigation.

Figure 1.

Uptake of [3H]ERα17p by different breast cancer cell lines. Cells were incubated with [3H]ERα17p (1.2 μM) in serum‐free medium, for the indicated time periods. At each incubation point, cells were detached, washed with PBS, disrupted with sonication and the cytosolic fraction, separated by centrifugation, was counted. Figure presents specific uptake at each time point. Mean ± SEM of three independent experiments in triplicate.

3.2. ERα17p induces massive early transcription in ERα‐positive and ‐negative cell lines, similarly to estradiol

Previous studies revealed that incubation of breast cancer cells with ERα17p (6–48 h) results in a transcriptional enhancement of E2‐regulated genes, such as PR (as early as 6 h) and pS2 (after 24–48 h of incubation) (Gallo et al., 2007a,b). Here, we investigated the transcriptional effect of ERα17p (applied at an extracellular concentration of 1 μM) on the whole transcriptome of three breast cancer cell lines (T47D, MDA‐MB‐231 and SKBR3), after a 3‐h incubation, in order to identify early (direct) transcriptional events induced by the peptide; E2‐treated (1 μM) cells were studied in parallel. We used the same concentration of E2, in order to compare the transcriptional effects of ERα17p on an equimolar basis.

We observed that (Table 1 and Supplemental Table 2):

ERα17p induced massive early gene transcriptional effects in all cell lines. The number of modified transcripts was higher in ERα‐ and β‐expressing T47D and MDA‐MB‐231, than in ERα/β‐negative SKBR3 cells.

There was a great analogy among the three cell lines concerning the number of common transcripts, modified in parallel by ERα17p and E2 (75% in T47D and MDA‐MB‐231 cells, and 68% in SKBR3). Noticeably, only a very small number of transcripts (eight in T47D and MDA‐MB‐231 and none in SKBR3 cells) were modified in the opposite direction by E2 and ERα17p, confirming at the transcription level the estrogenic nature of the peptide.

The fact that 25–32% of ERα17p‐modified genes were different from those modified by E2 could be relevant to the previously described ER‐independent actions of the peptide (Kampa et al., 2011; Pelekanou et al., 2011a).

Table 1.

Transcripts modified by estradiol or ERα17p (1 μM) in the different breast cancer cell lines, after 3 h of incubation. The column denoted “% common” denotes the percentage of ERα17p‐modified transcripts which show a similar modification by E2. The column “opposite” denotes the number of transcripts modified in an opposite way by either substance.

| E2 | ERα17p | Common | % common | Opposite | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T47D | 10,321 | 10,474 | 7894 | 75 | 8 |

| MDA‐MB‐231 | 13,513 | 12,792 | 9521 | 75 | 8 |

| SKBR3 | 2699 | 1970 | 1342 | 68 | 0 |

3.2.1. Analysis of common ERα17p and E2 modified genes

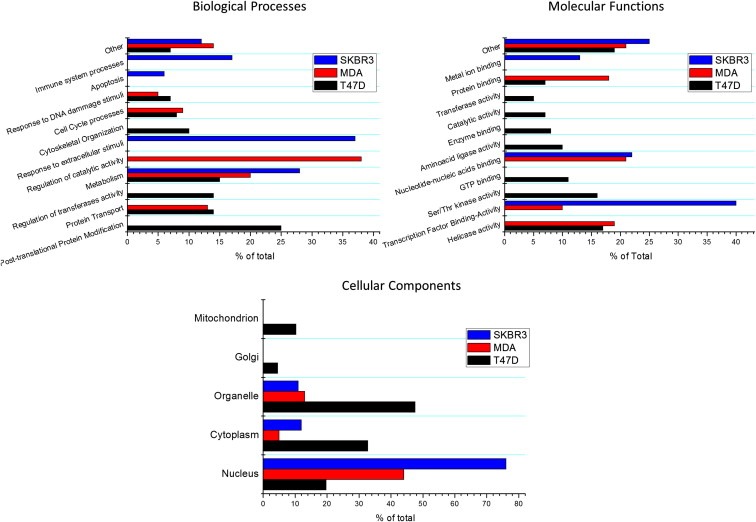

3.2.1.1. GO term analysis

GO term analysis of modified transcripts in the three investigated cell lines revealed a number of interesting elements (Figure 2): a common ERα17p effect identified in all cell lines concerned genes related to metabolism, an element shared also by E2 (Faulds et al., 2012). In addition, in T47D and MDA‐MB‐231 cells common significant GO terms were related to protein transport, cell cycle‐related processes, response to DNA‐damage stimuli and helicase activity. ERα17p exerts also a major effect on transcription factor activity and binding, in MDA‐MB‐231 and SKBR3 cells. Furthermore the peptide exerted a major action in the cell nucleus and had a significant effect on immune‐related functions in ERα/β‐negative SKBR3 cells.

Figure 2.

GO term analysis of ERα17p effects on the three cell lines studied.

3.2.2. ERα17p transcriptional events related to specific isoforms of the estrogen receptor

The different ER profiles of the studied breast cancer cell lines allowed us to further decipher ERα17p transcriptional effects on specific isoforms of the ERα:

3.2.2.1. ERα signature of ERα17p

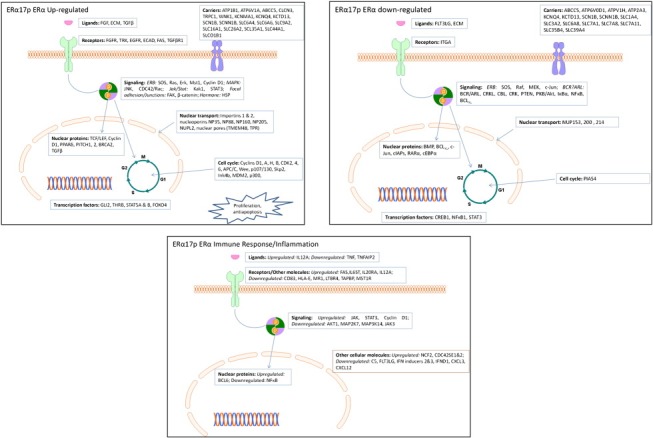

T47D and MDA‐MB‐231 cells share in common ERβ, ERα36, ERα46 and GPR30, while T47D additionally expresses ERα. Our analysis of ERα17p‐induced estrogenic effects in these two cell lines allowed the identification of an ERα‐related specific transcriptional signature: in T47D cells, 4406 transcripts, absent in the MDA‐MB‐231 list, were modified by ERα17p (Supplemental Table 3) and attributed to the ERα signature of the peptide. The modified GO terms (Supplemental Table 3 and Supplemental Figure 4) showed an increase of transport, cytoskeleton, cell adhesion, cell division and cycle‐related events. Pathway analysis revealed that ERα17p modified the NGF family‐, insulin‐, death receptor‐ and VEGF‐signaling, and signaling cascades involving mTor, PI3K/Akt, p38, ephrin and Ca2+‐calmodulin. Finally, the peptide interfered with multiple pathways regulating cell cycle checkpoints and apoptosis (Supplemental Table 3).

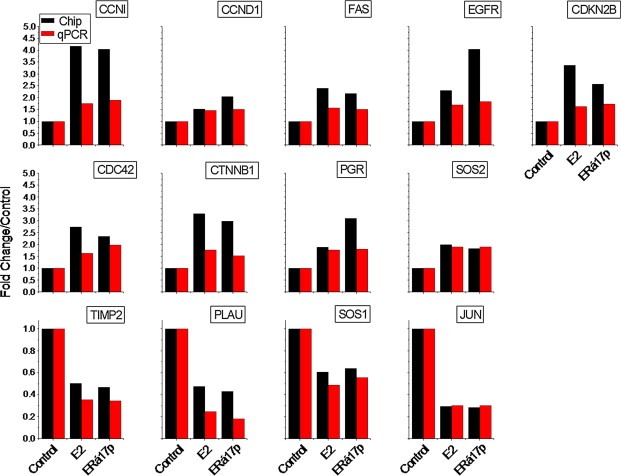

In order to further identify specific genes and pathways involved in ERα17p‐related ERα action, we performed a more strict analysis, using Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA, Ariazi et al., 2011; Mootha et al., 2003; Subramanian et al., 2005). We thus focused on 1035 ERα17p/ERα‐significantly modified genes (523 up‐regulated and 512 down‐regulated, Supplemental Table 3). Major cellular functions modified by the peptide include: (i) cell cycle, cell proliferation and apoptosis, (ii) cell migration and cytoskeleton network, (iii) inflammation and immune functions, and (iv) transport, receptor and signaling functions, nucleic acid‐related processes and protein synthesis (Table 2, Figure 3 and Supplemental Table 3). The effect of ERα17p on several of these transcripts was further verified by qRT‐PCR (Figure 4).

Table 2.

Major functions modified by ERα17p ERα‐related genes.

| Cell function | Regulation | Genes |

|---|---|---|

| Cell cycle proliferation differentiation | Down | AKT1S1, ANAPC2, ARAF, CAMK1, CAMK2B, CCND3, CDK5, CEBPA, CEP250, CHEK2, CLSPN, DDIT4, FOSL2, HTRA1, HYAL1, IFITM1, IFITM2, KIF3B, LAMB2, LASS1, MEF2D, NOTCH1, NRF1, PCGF2, PHB, RICTOR, RPS6KB2, SRM, TNF, TSPYL2, TSSK3 |

| Up | ABI2, ANAPC5, ANP32A, ANXA3, AURKA, BCCIP, BRWD1, BUB1, BUB1B, BUB3, CASC5, CCAR1, CCDC99, CCNA2, CCNB1, CCNC, CCND1, CCNG1, CCNH, CCNT2, CDC27, CDC42, CDC5L, CDCA8, CDH1, CDK2, CDK6, CDKN2B, CDKN3, CENPA, CENPE, CENPF, CENPK, CENPL, CENPQ, CEP110, CEP135, CEP70, CHEK1, CHFR, CHM, CIT, CP110, CSNK1A1, EP300, FBXW7, FGF12, FGFR1OP, FGFR2, GAS7, HDGFRP3, HSP90AA1, INCENP, KHDRBS1, KIF20A, KLHL13, LATS2, MAD2L1, MPHOSPH9, NCAPH, NEK1, OIP5, PPM1B, PPP2R5C, PWP1, RAD1, RAD21, RAD51L1, RBL2, RBM22, RERG, SDCCAG8, SGOL2, SKP2, SMC3, SRPK2, STAG2, TOB1, TP53BP1, TRIO, TTK, UHMK1, VRK2, WEE1, WTAP, ZAK | |

| Apoptosis migration cytoskeleton | Down | AATF, ADAMTS13, AKT1, AKT1S1, AKT2, ARHGEF11, ARHGEF2, ARHGEF7, ARHGEF9, BAG1, BCL2L1, BIRC3, CARD14, CDC42BPA, CDC42EP2, CDK5, COTL1, DDIT4, DFNB31, DNM2, FARP2, FGD5, FIS1, FLNA, HAX1, HOOK2, HTRA2, HYAL1, IFI6, IFITM1, IFITM2, IRF1, ITGA10, ITGA2B, JMY, JUND,,KRT7, MAPT, MCF2L, MEF2D, MYO9B, NFKB2, NOTCH1, OBSCN, OPHN1, PDLIM5, PEF1, PIM2, PLAU, PLEKHG2, PSD4, RERE, RIPK1, RRBP1, SEMA3B, SERPINB6, SMURF1, SOX4, TBCD, TCF25, TERF2, TERT, THBS3, TIMP2, TNF, TNNI3, TRIB3, TRPM2, WASF2 |

| Up | ABI2, ACTR2, ADD3, ALCAM, ANK3, ANLN, ANP32A, ARHGAP18, ATG3, AURKA, BCLAF1, BECN1, BRWD1, CALD1, CAP2, CASP6, CCAR1, CDC42, CDC42BPB, CDC42EP3, CDC42SE1, CDC42SE2, CEP70, CFL2, COL5A2, CRADD, CTNNB1, CYFIP1, DCDC2, DIAPH1, DIAPH3, DLG5, DOCK4, EML1, FAS, FGF12, GIT2, GSN, GULP1, IQGAP1, ITGB1BP1, KRAS, LAMB1, LATS2, LIMA1, MAP2, MAP7, MAPK8, MARCKS, MARK1, NEB, NFYB, OPA1, PALLD, PCDH18, PCDHB14, PCDHB17, PCDHB4, PCDHB5, PCDHB6, PCM1, PCNT, PDCD2, PFN2, PLCE1, PLOD2, PLS1, PRKCI, PRPF40A, PRUNE, PSIP1, PTK2, PTPN4, PTPRT, RBM25, RDX, RND3, ROBO1, ROBO2, SCIN, SON, SPAG9, SPTBN1, SSX2IP, STK3, TAOK1, TMOD3, TMPO, TPD52, TPD52L1, TPM1, TRIO, VAV3, VIM, XRN1, ZAK | |

| Inflammation | Down | AKT1, AZU1, C5, CASP8AP2, CD59, CD83, CEBPB, CXCL12, CXCL3, FCN2, FLT3LG, HDAC11, HLA‐E, IFI6, IFITM1, IFITM2, IFITM3, IFRD1, ISG20, JAK3, KCTD13, LCK, LTB4R, MADD, MAP2K7, MAP3K14, MR1, MST1R, MX1, NFATC1, NFKB2, NFKBIA, NR1H2, NR1H3, POLR3A, PRKX, PSMD3, PVR, RNF41, SIGIRR, TAPBP, TCIRG1, TIRAP, TNF, TNFAIP2, TNFRSF18, TNIP1, TSC22D3, TYK2, UCN, WARS, YARS, ZBTB7B |

| Up | ABI2, ALCAM, ANXA3, BCL6, BECN1, CDC42SE1, CDC42SE2, CDH1, CLEC7A, CRADD, FAS, HFE, IL12A, IL20RA, IL6ST, JAK1, KLHL20, KLHL9, LTBP1, M6PR, MAP3K1, MAPK8, NCF2, NFAT5, PCDHB4, PCDHB5, PCDHB6, PDCD2, PRKD3, ROBO1, ROBO2, SEMA3C, STAM2, STAT3, SULF1, TGFB2, TPP2, VEZF1, VIM | |

| Receptors‐signaling | Down | ADCY1, ADORA1, AK1, AKT1, AKT1S1, AKT2, ARAF, ARFGAP1, ARFIP2, ARHGEF11, ARHGEF2, ARHGEF7, ARHGEF9, ARRB1, ARSG, BCR, BIRC3, BMP4, BYSL, CARD14, CARM1, CASP8AP2, CBLC, CD59, CDC42BPA, CDC42EP2, CEBPG, CLTCL1, COPG, CRK, DUSP4, DUSP5, EEF2K, EFNA1, ERBB4, FGD5, FIBP, FLOT2, FOLR1, FOSL2, HOMER3, HTRA1, HTRA2, IFITM1, IGFBP4, IKBKE, IRS1, ITGA10, ITGA2B, JAK3, KISS1R, LAMB2, LASS1, LCK, LDLRAP1, LTB4R, MADD, MAP2K2, MAP2K5, MAP2K7, MAP3K12, MAP3K14, MAP3K3, MAP3K4, MAP3K9, MAPK11, MAPK8IP3, MAST2, MC1R, MCF2L, MIB2, MST1R, MX1, MYO9B, NFKB2, NFKBIA, NFKBIE, NOTCH1, NPW, NUCB1, OBSCN, OPHN1, OS9, PDE4A, PEF1, PHB2, PIAS4, PIM2, PLA2G4C, PLAU, PLEKHG2, PPP1R3C, PPP1R9B, PPP2R1A, PRKAA1, PRKAB1, PRKAR1A, PRKX, PSD4, PTEN, RAB31, RAB5B, RAB5C, RELA, RELB, RENBP, RGS11, RGS16, RICTOR, RIPK1, RTN4RL1, SH2B1, SH3GLB2, SHC2, SIGIRR, SMPD1, SMURF1, SMURF2, SNX6, SOS1, SPG7, SPINT1, SPRY4, SQSTM1, SUFU, TBRG1, TIRAP, TMF1, TNF, TNFAIP2, TNFRSF18, TNIP1, TNNI3, TRAK1, TRIB3, TRPM2, TSC2, TSC22D3, TSSK3, TYK2, WASF2, YARS |

| Up | ACVR1B, AGGF1, AKAP13, ARHGAP18, ARNTL, AURKA, BCCIP, BMPR2, CALD1, CAP2, CCAR1, CDC42, CDC42BPB, CDC42EP3, CDC42SE1, CDC42SE2, CDK2, CDK5RAP2, CDKN2B, CIT, CLCN3, CLEC7A, CRIM1, CSNK1A1, CTNNB1, CTSC, CXADR, DAB2, DCBLD2, DLG1, DLG2, DLG5, DTNA, DUSP11, DYRK2, EFNB2, EGFR, EP300, ERBB3, FAS, FGF12, FGFR1OP, FGFR2, GEM, GIT2, GNA13, GNAQ, GNAS, GNB1, GNG12, GPR126, GPR37, GUCA1C, HIPK2, HSP90AA1, HSP90B1, HSPD1, HSPH1, IL12A, IL20RA, IL6ST, JAK1, KHDRBS1, KRAS, LAMB1, LANCL1, LATS2, LEMD3, LTBP1, M6PR, MAGI1, MAN1A1, MAP3K1, MAP3K13, MAP4K5, MAPK1, MAPK8, MARCKS, MARK1, MDM2, MDM4, MPDZ, NEDD4, NF1, NLK, NPR3, NR1D2, NSD1, OLR1, OSTF1, P2RY2, PCDH18, PCDHB14, PCDHB17, PCDHB4, PCDHB5, PCDHB6, PDE7A, PGR, PIAS1, PKN2, PLCB1, PLCE1, PPARD, PPM1B, PRKACB, PRKCH, PRKCI, PRKD3, PRLR, PROM1, PRUNE, PTCH1, PTGER3, PTK2, PTP4A2, PTPLA, PTPN4, PTPRT, RAB27A, RAB35, RAB6A, RANBP2, RHEB, RIT1, RND3, SCIN, SEMA3C, SMAD5, SNAP23, SOS2, SPAG9, SPTLC2, SRPK2, SSR3, STAM2, STAT3, STK3, STK4, SULF1, TAOK1, TCF7L2, TGFB2, TJP1, TJP2, TOB1, TPD52, TPD52L1, TRPC1, TTK, UHMK1, VAV3, VRK2, WEE1, WNK1, ZAK | |

| Transport | Down | ABCB9, ABCC3, ABCC5, AP1G2, AP1M1, AP2B1, AP2S1, ARFGAP1, ARFIP2, ATP2A3, ATP6V0D1, ATP6V1H, BET1L, BRAP, CAMK1, CAMK2B, CHMP4A, CLN3, CLTCL1, COG2, COG7, COPE, COPG, COPZ1, CPLX1, CPNE1, CTNS, FLOT2, FXYD6, GBA2, GGA2, HIP1R, HOOK2, HPS1, HPX, ICA1, KCNQ4, KCTD13, KIF13A, KIF1B, KIF3B, LCN1, LDLRAP1, MAST2, MCOLN1, MTL5, NF2, NUCB1, NUP153, NUP210, NUP214, PEF1, RAB11FIP4, RAB31, RAB5B, RAB5C, RRBP1, SCAMP3, SCN1B, SCNN1B, SLC16A3, SLC1A4, SLC35B4, SLC39A4, SLC3A2, SLC44A2, SLC6A8, SLC7A1, SLC7A11, SLC7A8, SLC9A5, SLC9A8, SNX6, SPRR1A, STARD3, STX5, STX6, TCIRG1, TFF3, TGOLN2, TIMM13, TIMM17B, TMED10, TMF1, TMPRSS3, TOM1, TRAK1, TRPM2, VPS28, YIPF2, YIPF3, YKT6 |

| Up | ANP32A, AP1S1, AP1S3, AP3B1, ARL4D, ATP1B1, ATP6V1A, CASQ2, CDC42, CGN, CHM, CLCN3, CLDN1, CLDN8, CLEC3A, CLEC7A, COG5, COG6, COL5A2, COPA, DLG1, DLG2, DLG5, DSG2, DST, DTNA, DYNC1I2, DYNC1LI2, EEA1, ERGIC2, EXOC5, GOPC, GOSR1, HFE, IPO7, KCNMA1, KIF5B, KPNA3, KTN1, MYO6, NLGN1, NLGN4X, NUP160, NUP205, NUP35, NUP88, NUPL2, OLR1, PCM1, PCNT, RABEP1, RCN2, SCAMP1, SCARB2, SEC14L1, SEC22C, SEC23IP, SEC31A, SEC63, SLC16A1, SLC26A2, SLC35A1, SLC44A1, SLC6A4, SLC6A6, SLC9A2, SLCO1B1, SNAP23, SPAG9, SSR3, SSX2IP, STEAP1, TFRC, TJP1, TJP2, TMEM48, TMPO, TNPO1, TPR, TRAM1, TRPC1, VIM, VPS35, WNK1 |

Figure 3.

Specific genes modified by ERα17p and related to ERα activation. See text for details.

Figure 4.

qRT‐PCR verification of the E2‐ and ERα17p‐modified genes, related to the ERα signature of the peptide. Figure presents genes modified by ERα17p and E2. Red bars show qRT‐PCR results and black bars results obtained during the analysis of the gene‐chip data.

3.2.2.1.1. Analysis of ERα17p actions through ERα

3.2.2.1.1.1. Cell cycle, cell proliferation and apoptosis

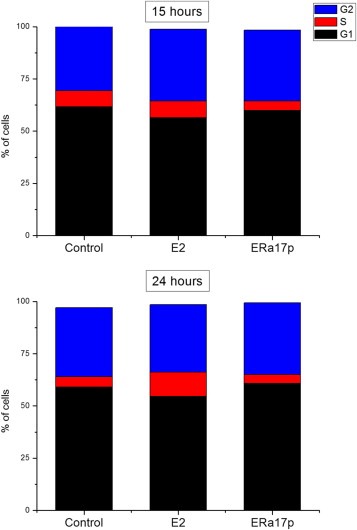

ERα17p induces proliferation of ERα‐positive cell lines exclusively (Gallo et al., 2008,b). We identified 118 genes (86 up‐regulated, 31 down‐regulated, Table 2 and Supplemental Table 3) related to cell cycle and cell proliferation. Up‐regulated genes include cyclins (B1, C, D1, G1, H, T2) acting on different phases of the cell cycle, cyclin‐dependent kinases (CDK2 and 6) or cyclin‐dependent kinase regulators (BCCIP, CDKN3, PPM1B, SKP2, UHMK1, WEE1), suggesting a stimulatory effects of the peptide at different phases of the cell cycle. In addition, a number of genes encoding for proteins related to spindle formation, stabilization and function (Aurora kinase A, BUB1, BUB1B, BUB3, CDD99, CDC42, LATS2, MAD2L1, OIP5, SMC3), centromere (CENPA, CENPE, CENPF, CENPK, CENPL, CENPQ, INCENP), centrosome (CEP70, 110 and 135, LATS2, NEK1, SGOL2) and cytokinesis (KIF20A, KLHL13) were also modified. Genes involved in DNA integrity and damage repair were also up‐regulated. Interestingly, many of these proteins are known to be under the control of ERα (Eichinger and Jentsch, 2011; He et al., 2008; Scorah and McGowan, 2009; Stengel et al., 2009; Yuan et al., 2007; Zhang and Herrup, 2011). These regulatory effects were further verified by performing a cell cycle analysis of T47D cells (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Cell cycle modification of T47D cells, incubated for different time periods with E2 or ERα17p. Incubation of cells in the presence of the peptide leads to an early increase of cells in the G2 phase (15 h) and a late (24 h) increase of cells in the G1 phase.

Inline with the above findings, the expression of several ERα‐dependent genes, related to the antiapoptotic action of estrogens was modified by ERα17p, in medium deprived of E2 (Supplemental Table 3). ERα17p down‐regulated interferon regulatory factor‐1 (IRF1), a tumor suppressor that mediates cell fate by facilitating protection in endocrine‐resistant breast cancer cells (Schwartz et al., 2011). Interestingly, IRF1 is crucial for regulating the IFN‐gamma positive apoptotic effects on TNF‐alpha (Suk et al., 2001) and activating the expression of CD95 (APO‐1/Fas) (Kirchhoff et al., 2002). In this regard, antiestrogens have been reported to increase IRF1 expression, thereby inducing caspases 1‐ and 3‐mediated apoptosis (Bouker et al., 2004; Bowie et al., 2004). ERα17p also blocked the expression of JunD, a member of the AP1 family of transcription factors that acts under the control of E2 (Srivastava et al., 1999). Other antiapoptotic genes modified by ERα17p and regulated by estrogens include Notch1 (Rizzo et al., 2008), ALCAM/CD166 (Jezierska et al., 2006a,b) and CCAR1 (Kim et al., 2008). Hence, under E2‐deprivation, ERα17p behaves as an antiapoptotic agent, operating in an ERα‐dependent manner, a result inline with the effects of estrogens in breast cancer cells.

3.2.2.1.1.2. Cell migration and cytoskeleton network

A number of genes involved in cell migration and modified by estrogens in breast and other tissues were also targeted by ERα17p, leading to modification of cell migratory capacity and cytoskeletal modifications (Table 2 and Supplemental Table 3). ERα17p, similarly to E2, modified CTNNB1 (catenin beta 1) a protein known to modify the migratory capacity and invasiveness of breast cancer cells (Planas‐Silva and Waltz, 2007) and Aurora‐A, another estrogen‐regulated molecule (Jiang et al., 2012) recently proposed as a proliferation marker and a predictor of aggressiveness in ER‐positive breast cancers (Ali et al., 2012). ERα17p also increased CDC42 expression, an important partner for E2‐mediated cell motility (Felty et al., 2005; Takahashi et al., 2011) and microtubule‐associated protein‐2 (MAP2), which regulates microtubule assembly (Reyna‐Neyra et al., 2002; Zhang et al., 2001). ERα17p repressed also the expression of several other E2‐regulated genes, contributing to cell migration (Walker et al., 2007; Yoffou et al., 2012). This is the case of HYAL1 (hyaluronoglucosaminidase‐1, a lysosomal hyaluronidase involved in cell proliferation, migration and differentiation), KRT7 (Keratin‐7, a type II cytokeratin, specifically expressed in the gland ducts) and PTK2 (Anaganti et al., 2011; Sanchez et al., 2010). Hence, ERα17p induces the modification of a set of genes involved at different stages of cell migration.

3.2.2.1.1.3. Inflammation and immune actions

ERα17p also exerted an inhibitory effect on immune/inflammatory responses (92 genes, Table 2 and Supplemental Table 3). It down‐regulated TNFα and TNFα‐induced protein‐2 (TNFAIP2), as well as the final effector of the TNF pathway, NFκB (O'Donnell and Ting, 2010; Schutze et al., 1992). A decrease of the E2‐related TNF transcriptional activity has been proposed to operate through a JNK–JUN‐related pathway (Srivastava et al., 1999), possibly in a tissue and cell specific manner. JUN expression was also found to be decrease in our study. Strikingly, cyclin D1 (up‐regulated in our set) may act as a transcriptional inhibitor of NFκB (Rubio et al., 2012), providing a complementary level of regulation. In the context of membrane‐associated antigen recognition, CD83, HLA‐E, MR1, LTBR4 and TAPBP as well as their intracellular signaling counterparts AKT1, MAP2K7, MAP3K14 and JAK3 were found to be down‐regulated, as was also the case of chemokines CXCL3 and 12, suggesting that ERα17p is a potent down‐regulator of immune responses.

Conversely, several immune‐related elements were up‐regulated by the ERα‐related action of ERα17p, including pathways relying on FAS and IL6ST (a member of the IL6R), IL20RA and IL12A previously reported as modified by E2 in other tissues (Antonios et al., 2010; Ratsep et al., 2008; Shao et al., 2009). Downstream signaling of these molecules might occur through JAK and STAT3 to the nuclear protein BCL6 (all found up‐regulated by ERα17p). Lastly, ERα17p modifies the expression of the immunophilins FKBP, which are targeted by the immunosuppressive macrolides FK506 (tacrolimus) or rapamycin (Solassol et al., 2011).

3.2.2.1.1.4. Transport, receptor and signaling functions, nucleic acid‐related processes and protein synthesis

Estrogen‐related non‐genomic actions are usually associated with the transport of ions and other molecules between the extracellular and the intracellular compartment, or between intracellular organelles (see Saint‐Criq et al., 2012, for a recent review). In our set of genes, we have identified 177 elements (Table 2 and Supplemental Table 3) involved in transport functions. The most noticeable effects of ERα17p concerned ion and solute carriers, including ATP1B1 and the lysosomal EGF‐related ATP6V1A (Li et al., 2011b; Vinayagam et al., 2011). In contrast, ERα17p decreased the transcription of ABCC5, ATP6V0D1 and ATPV1H (ensuring lysosomal H+ transport) and ATP2A3, which participates in the transfer of Ca++ into the sarcoplasmic reticulum. The CLCN3 (Cl−), TRPC1 (Ca++), WNK1 (Na+/Cl−), as well as the KCNMA1 (K+) ion transporters, previously reported as activated by ERα (Danesh et al., 2011), were also modified. In contrast, ERα17p decreased the transcription of K+‐channels KCNQ4 and KCTD13 and of Na+ transporters SCN1B and SCNN1B. Other major effects were observed on the transcription of CLDN1, CLDN8, DSG2, DST, SSX21P and TIJP1/2, which are components of tight junctions, ensuring the sealing of epithelia (Saint‐Criq et al., 2012). ERα17p also inhibited the Na+/H+ exchangers SCLA5 and SCLA8 and increased the transcription of solute carriers important for cell detoxification, i.e., SLC6A4 (serotonin), SLC6A6 (taurine), SLC9A2 (metabolic acids), SLC16A1 (monocarboxylates), SLC26A2 (sulfates), SCL35A1 (nucleotide sugars), SLC44A1 (choline) and SLCO1B1 (organic anions). In contrast, it inhibited SLC1A4 (Ser, Cys, Ala, Thr), SLC3A2 (l‐aminoacids), SLC6A8 (creatine), SLC7A1 and SLC7A8 (a general aminoacid transporter), SLC7A11 (Cys, Glu), SLC35B4 and SLC39A4 (Zn, Fe) transporters, preserving therefore building blocks involved in protein and metabolic processes and cell proliferation.

ERα contains in its sequence (in the hinge region, from which ERα17p is issued) the third nuclear localization signal (reviewed in Sebastian et al., 2004). In this context and according to the transport of proteins into the nucleus by importins (Gorlich et al., 1995; Moroianu et al., 1995), we identified two importin genes (importin‐IPO7‐ and importin‐2‐KPNA3‐) up‐regulated by the peptide. Likewise, the transcription of other nuclear pore‐related genes, such as nucleoporins (NP35, NP88, NP160, NP205, NUPL2), the karyophorin receptor (TNPO1), the nuclear pore protein TMEM48 and the Myc‐activated nuclear pore element TPR were also increased. Thus, the net effects of ERα17p on cytoplasmic‐to‐nuclear transport mechanisms could reflect transcription enhancement of major elements constituting nuclear pores and the nuclear envelope as well as specific carrier proteins.

Finally, a major event associated with rapid ERα‐related effects is the anchorage of the receptor at the plasma membrane, a property resulting from its palmitoylation at Cys‐447 (Acconcia et al., 2005; Reid et al., 2003) as well as its interaction with EGF receptors (reviewed in Thomas and Gustafsson, 2011). The interaction with EGFR occurs not only with Src (caveolin‐ and clathrin‐independent (Benten et al., 2001) or ‐related mechanisms (Moats and Ramirez, 2000; Sebastian et al., 2004; Sreeja and Thampan, 2004)), but also with other effectors, such as the G‐protein coupled membrane receptor GPR30 (Cheng et al., 2011a,b). Among ERα‐related ERα17p‐modified transcripts, we identified a number of proteins of the adaptor complex (plasma membrane proteins related to clathrin‐mediated endocytosis) (Jafar‐Nejad et al., 2002; Kjaerulff et al., 2002) either up‐regulated (AP1S1, AP1S3, AP3B1) or down‐regulated (AP1G2, AP1M1, AP2B1, AP2S1, CLTL1) by ERα17p.

3.2.2.1.1.5. Other genes‐functions (Supplemental Table 3)

In addition to the ERα17p‐mediated events described above, we verified the previously described induction of the progesterone receptor by the peptide (PGR, Figure 4) (Gallo et al., 2008) while pS2 (TFF1) transcription, which corresponds to a late event regulated by ERα and is probably related to late‐direct or indirect actions of E2 (Gallo et al., 2008; Jeong et al., 2012), was not identified in our dataset.

EGFR is a major partner for ERα‐associated cytoplasmic/membrane effects. Here, we show that ERα17p, through an ERα‐dependent mechanism, increased the transcription of EGFR and ERBB3. It is of note that an additional decrease of ERBB4 transcription was observed, while no effect was noticed for ERBB2 gene. To our knowledge, it is the first time that direct effects of ERα on EGFR are reported (Figures 3 and 4), even if it has already been suggested by RNA interference (Cochrane et al., 2010). Hence, our data could explain the parallel expression of EGFR isoforms with ERα, reported in breast cancer samples (Pinhel et al., 2012).

3.2.2.1.1.6. ERα‐related transcription factors modified by ERα17p

In silico transcription factors analysis revealed GLI2, THRB, STAT5A & B and FOXO4 as putatively activated by ERα17p, while CREB1, NFκB1 and STAT3 are down‐regulated (Supplemental Table 3). The GLI transcription factor family is classically associated with the Hedgehog pathway. However, recent data (reviewed in Javelaud et al., 2011) link TGFβ (a gene up‐regulated in our data set) and GLI. Likewise, we recently reported that CREB and NFκB are down‐regulated in breast cancer cells, through E2 non‐genomic pathways (Kampa et al., 2012), providing evidence of opposite nuclear and extranuclear actions of estrogens. In the same context, the thyroid hormone receptor (THR), down‐regulated in our study, has been reported to be affected by estrogens in fish (Filby et al., 2006), but never before in humans. Furthermore, this is the first report identifying a link between FOXO4 and ERα. Lastly, it should be stressed that we have already reported that STAT3 activation is a sustained effect of membrane‐acting androgen (Pelekanou et al., 2010) and estrogen (Kampa et al., 2012), providing a link between membrane and nuclear estrogenic effects.

3.2.2.2. ERα36‐related signature of ERα17p

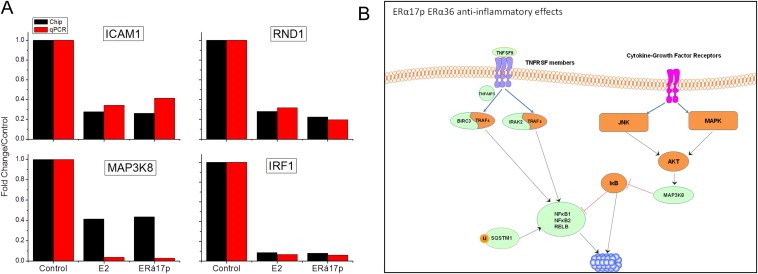

The ERα36 is an ERα variant, initially identified in ERα‐negative cell lines (Wang et al., 2005, 2006) as well as in “triple‐negative” breast tumors (Pelekanou et al., 2011b), in addition to ERα‐positive breast cancer cells (Kampa et al., 2012; Notas et al., 2011; Pelekanou et al., 2011b). Its presence could explain some of the E2 effects, previously claimed as ERα‐independent. The ERα17p sequence is conserved in ERα36, suggesting that this receptor variant might be subjected to similar regulatory interactions, as ERα. Although some reports identified fulvestrant (ICI 182,780, a pure ER antagonist) as an inert agent on ERα36 (Ohshiro et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2006), in our hands it acted as an antagonist (Pelekanou et al., 2011b, and unpublished observations), suggesting that the binding pocket of the ERα36 receptor adopts a conformation similar to that of wild‐type ERα. Thus, ERα17p may exert similar effects on this variant. In a previous study we have identified the transcriptional signature of ERα36 in SKBR3 cells (Pelekanou et al., 2011b), in which ERα17p exerts proapoptotic effects and influences cell migration (Kampa et al., 2011; Pelekanou et al., 2011a). Here, we compared ERα36‐modified genes (Pelekanou et al., 2011b) with either E2‐ or ERα17p‐modified transcripts and identified a list of 218 commonly modified elements (Supplemental Table 4). Of interest, all these transcripts/genes were down‐regulated by ERα17p and E2, pointing‐out ERα36 as a mainly inhibitory receptor. Regulation of some of these genes was verified by qRT‐PCR (Figure 6A). By comparing this list of transcripts in the T47D cells, equally positive for ERα36 (Pelekanou et al., 2011b), we identified 163 transcripts (75% of total) that were modified in a similar manner by ERα17p, giving further weight to our approach, i.e., of a specific transcriptional signature of ERα17p on the ERα36 receptor (Supplemental Table 4).

Figure 6.

qRT‐PCR verification of the E2‐ and ERα17p‐modified genes, and immune pathways inhibited by ERα36 activation in SKBR3 cells. A. Both E2 and ERα17p inhibited the expression of ICAM1, RND, MAP3K8 and IRF1 in SKBR3 cells. Red bars show qRT‐PCR results and black bars results obtained during the analysis of the gene‐chip data. B. Schematic presentation of immune pathways inhibited by ERα36 activation based on gene‐chip data analysis. See text for details.

GO associated terms of ERα36‐related ERα17p‐regulated transcripts (Supplemental Table 4 and Supplemental Figure 5) revealed the down‐regulation of genes involved in cell proliferation, apoptosis and immune‐related processes. Interestingly, the same GO terms were found in the subset of 163 common genes between T47D and SKBR3 cells. NGF family, Ca2+‐calmodulin, VEGF, death and apoptotic signaling (mediated by NRAGE, not previously identified in relation to estrogen), innate immunity and signaling through p38 isoforms, CREB and PLCγ are the main down‐regulated pathways (Supplemental Table 4).

A strict Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) of the 218 transcripts recovered 29 genes, significantly down‐regulated by the peptide. They were associated with (i) immunity and inflammatory processes; (ii) cell proliferation, invasiveness and apoptosis; (iii) actin cytoskeleton remodeling and (iv) signal transduction (Supplemental Table 4). For a number of genes (ALCAM, ATF3, BIRC3, CCL20, CXCL1, END1, EGR1, FOSB, GADD45B, HBEGF, JUN, JUNB, SQSTM1, TNFAIP3), an E2‐dependent increase had been previously reported (Brown et al., 2010; Clarke et al., 2009; Crane‐Godreau and Wira, 2005; Frasor et al., 2003; Jezierska et al., 2006a; Liu et al., 2007; Lu et al., 2008; Moreno‐Bueno et al., 2003; Pennanen et al., 2009; Pradhan et al., 2012; Rau et al., 2003; Seidlova‐Wuttke et al., 2003; Shen et al., 2011; Sun et al., 2012; Vendrell et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2007), evoking that ERα36 and ERα may exert opposing effects. It is further important to note that JUN modifications (decreased in our set of genes) were recently reported to be related to the activation of ERα36 (Zhang et al., 2012).

Several putative transcription factors down‐regulated by ERα17p on ERα36 were also identified by an in silico analysis (Supplemental Table 4). NFκB and CREB1 were inhibited, implying common ERα‐ and ERα36‐dependent mechanisms. However, opposite effects were found on GLI2 and FOXO family transcription factors: they were up‐regulated by ERα‐ and down‐regulated by ERα36‐related events. Lastly, a number of unique transcription factors decreased in an ERα36‐dependent manner, including SP1 and 4, ETS and JUN.

3.2.2.2.1. Anti‐inflammatory effects of ERα17p (Figure 6B)

ERα17p induces anti‐inflammatory effects by down‐regulating three elements of the NFκB/Rel family, namely NFκB1, NFκB2 and RELB. This may be further potentiated by the down‐regulation of BIRC3, which associates with TRAF1 and 2, inhibiting thereby NFκB (Diessenbacher et al., 2008). This gene was previously reported to be enhanced by ERα‐mediated ERE expression (Pradhan et al., 2012). This is an additional concrete example of a differential regulation of genes by ERα and ERα36. Other identified genes could also down‐regulate NFκB/REL, including IRAK2 (involved in IL1R (Li et al., 2011a) and TNF signaling to NFκB (Flannery et al., 2011)) as reported here. In this regard, the down‐regulation of MAP3K8 (TPL2/COT) is linked to the down‐regulation of NFκB‐dependent p38 and JNK signaling process. Since it is implicated in TNF, TLR4 and IL2 signaling, it could contribute to breast and prostate cell growth as well as therapeutic response (Jeong et al., 2011; Pang et al., 2011). This is the first time that MAP3K8 is reported as an ERα36‐related estrogen‐modulated gene. Other decreased genes include the adaptor protein SQSTM1, an ubiquitin‐binding protein functioning as a scaffolding/adaptor protein in concert with TRAF6, to mediate the activation of NFκB (McManus and Roux, 2012), TNFAIP3, and TNFSF9 (also involved in NFκB/REL activation). Therefore, ERα36 modifies the TNF superfamily cytokines, MAPK and JNK signaling cascades, decreasing NFκB/REL‐related inflammation. Moreover, it decreases the expression of chemokines (CCL20, CXCL1) (Supplemental Table 4).

3.2.3. Non‐ERα‐related actions of ERα17p

3.2.3.1. GO terms and pathways in different cell lines

As discussed above, 2580 (25%), 3271 (25%) and 628 (32%) transcripts, modified by ERα17p in T47D, MDA‐MB‐231 and SKBR3 cells, were not influenced by E2 (Table 1). Therefore, these transcripts might represent the “non‐estrogenic” signature of the peptide, an observation that suggests additional non‐ERα‐related targets (Supplemental Table 5):

T47D cells: ERα17p down‐regulated GO terms, related to the control of transcription and metabolism. Data analysis revealed a positive regulation of apoptosis (see below), metabolic‐related pathways and interestingly, EGFR‐related pathways, suggesting an alternative way of the EGFR signal mediation (in addition to E2‐related pathways reported above).

MDA‐MB‐231 cells: ERα17p up‐regulated GO terms related to transcription and cellular metabolism, through nucleic acid and transcription factor association.

SKBR3 cells: ERα17p up‐regulated apoptotic and catabolic pathways and down‐regulated signaling (STAT3, IL22, AhR and BCMA‐related) pathways.

3.2.3.2. Specific non‐ERα‐related ERα17p effects

Our previous data (Kampa et al., 2011; Pelekanou et al., 2011b) suggest that actin network remodeling, migration and apoptosis are common in all the ERα17p‐treated breast cancer cell lines, independently from the expressed ER isoforms. However, the net phenotypic effect of ERα17p depends, in the different cell lines, on the absence or presence of E2 in culture medium. In order to identify such ERα‐independent genes, we performed, in T47D cells, a GSEA analysis of ERα17p modified, non‐ERα‐related transcripts. Several significantly modified genes, related to apoptosis or actin remodeling, were identified. A brief discussion for the function of these genes is presented below:

Apoptosis: Several genes with either pro‐ or antiapoptotic functions were identified; up‐regulated proapoptotic genes included caspase 10, TNFSF10, FAS, PAK2 (p21 protein (Cdc42/Rac)‐activated kinase 2), MAPK2, MAP2K6, PMAIP1 (phorbol‐12‐myristate‐13‐acetate‐induced protein‐1), BCL2L11, PTEN and RB1. Additionally, a number of antiapoptotic genes were also identified here, including PTPN13 (blocks Fas mediated apoptosis), TAX1BP1 (Freiss and Chalbos, 2011)) and STAT1. Additionally, the up‐regulated BCL2L1 and GADD45 may act as potential switches for the pro‐ or antiapoptotic functions of this peptide.

Actin cytoskeleton and cell migration: Sixteen up‐regulated elements involved in actin cytoskeleton remodeling and dynamics were identified, including EGFR, PDGFD, the muscarinic receptor CHRM2, G‐proteins involved in actin cytoskeleton signaling (GNG12, GNA12), SOS1 and 2 (guanine nucleotide exchange factor for RAS proteins), ARAF (a Raf Ser/Thr kinase), as well as PAK1 and 2 (p21/Cdc42/Rac1‐activated kinases, which are critical for the action of Rho GTPases on cytoskeleton reorganization) (Burridge and Wennerberg, 2004; Pollard, 2003; Schmitz et al., 2000). Finally, genes coding for NCKAP1, CYFIP2, which are parts of the wave complex regulating actin filament reorganization, lamellipodia formation and MYH10 (myosin) (that participates in the final step of actin formation and action), were also found up‐regulated.

3.3. Concluding remarks

The results reported here show that ERα17p, which corresponds to the 295–311 region of the ERα, internalizes in breast cancer cells and exerts early/direct transcriptional actions. Comparing the effect of ERα17p with E2 under identical conditions, we observed that 70–75% of the ERα17p‐modified transcripts were similarly modified, confirming the estrogenic profile of the peptide (Gallo et al., 2008). The common transcriptional effects displayed by ERα17p and E2 in the various cell lines, in connection with our previous studies (Notas et al., 2011; Pelekanou et al., 2011b), allowed us to identify selective ER isoforms (ERα, ERα36)‐related ERα17p signatures. Furthermore, the finding that a subset of E2 and ERα17p‐related transcripts are not related to ERα or ERα36, suggests a direct or indirect interaction of the hormone and the peptide with other (iso)forms, such as ERα46, which is present in the majority of our cell lines (Pelekanou et al., 2011b). Remarkably, this isoform contains also a wild‐type hinge region (Heldring et al., 2007), assumed to be implicated, at least in part, in the mechanism of action of the peptide (Gallo et al., 2007b). In addition, since the H4/type II β turn of ERα (residues 364–370), which constitutes the intramolecular‐binding site of the ERα17p‐corresponding sequence according to molecular modeling, is well conserved in ERβ (Zhou et al., 2006), an interaction of the peptide with ERβ cannot be excluded. In this context, a thorough search of online protein–protein interaction databases and resources (http://mdl.shsmu.edu.cn/SPPS/) revealed that ERα17p might additionally interact with a panel of nuclear receptors, such as the androgen, glucocorticoid, vitamin D and retinoic acid receptors, as well as with non‐nuclear receptor elements (ABCA3, B3A3, MLL4 and AT11C transporters and other proteins). These in silico data could possibly explain our finding that ∼25% of the modified transcripts result from an ER‐independent action of the peptide. The observation that actin cytoskeleton modifications and apoptotic‐related genes previously identified in ERα‐positive and ‐negative breast cancer cells (Kampa et al., 2011; Pelekanou et al., 2011a) were identified as non‐ERα‐related effects of ERα17p further supports the view of a more complex peptide interactome.

Finally, the present study compares for the first time early transcriptional actions of E2 and ERα17p, on ERα and ERα36. In the context of ERα, the peptide induces positive effects relevant to cell cycle and cell proliferation, as well as on nucleic acid and protein synthesis like other estrogenic molecules (Heldring et al., 2007; Thomas and Gustafsson, 2011). It also induces major effects on signaling molecules, as well as on ion and solute transport, classically attributed to extranuclear ERα actions. However, diverse (positive and negative) effects on immune and inflammatory events were also recorded. ERα36 actions of ERα17p and E2 were inhibitory, including principally anti‐inflammatory effects. These observations are of major importance as the presence of ERα36 in triple‐negative breast tumors might signify a better prognosis for patients (Pelekanou et al., 2011b). Hence, further research on the ERα17p actions should be pursued, since it could open new possibilities for the development of novel therapeutic/diagnostic tools and could constitute a valid tool for the study of molecular interactions of estrogen receptor(s).

Supporting information

Supplementary Table 1. Primers used for qRT‐PCR verification of genes presented in Figures 3 and 5.

Supplementary Table 2. Complete list of transcripts and corresponding GO terms/pathways in T47D, MDA‐MB‐231 and SKBR3 cells, commonly modified by E2 and ERα17p.

Supplementary Table 3. ERα signature of ERα17p. The different sheets of this table show: (1) probes modified by E2 and ERα17p in T47D cells, not present in the MDA‐MB‐231 lists. Highlighted the eight probes differentially modified by either agent. (2) Significantly modified GO terms and pathways, with their statistical significance and number of modified probes. (3) Significantly modified genes, extracted after a GSEA analysis of modified probes and their implication in different cellular functions. See text for further details. (4) Significantly up‐ and down‐regulated transcription factors after in silico analysis of modified probes with the online resource TFacts.

Supplementary Table 4. ERα36 signature of ERα17p. The different sheets of this table show: (1) probes modified by E2 and ERα17p in SKBR3 cells, as compared to the previously reported ERα36 signature of estradiol in this cell line (26). (2) Significantly modified GO terms and pathways, with their statistical significance and number of modified probes. (3) Significantly modified genes, extracted after a GSEA analysis of modified probes and their implication in different cellular functions. See text for further details. (4) Significantly down‐regulated transcription factors after in silico analysis of modified probes with the online resource TFacts. (5) Subset of modified transcripts extracted from the T47D lists.

Supplementary Table 5. Complete list of transcripts and corresponding GO terms/pathways in T47D, MDA‐MB‐231 and SKBR3 cells, modified exclusively by ERα17p, corresponding to the non‐estrogenic signature of the peptide.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data 1.

1.1.

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.molonc.2013.02.012.

Notas George, Kampa Marilena, Pelekanou Vassiliki, Troullinaki Maria, Jacquot Yves, Leclercq Guy, Castanas Elias, (2013), Whole transcriptome analysis of the ERα synthetic fragment P295‐T311 (ERα17p) identifies specific ERα‐isoform (ERα, ERα36)‐dependent and ‐independent actions in breast cancer cells, Molecular Oncology, 7, doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2013.02.012.

References

- Acconcia, F. , Ascenzi, P. , Bocedi, A. , Spisni, E. , Tomasi, V. , Trentalance, A. , Visca, P. , Marino, M. , 2005. Palmitoylation-dependent estrogen receptor alpha membrane localization: regulation by 17beta-estradiol. Mol. Biol. Cell. 16, 231–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali, S. , Coombes, R.C. , 2002. Endocrine-responsive breast cancer and strategies for combating resistance. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2, 101–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali, H.R. , Dawson, S.J. , Blows, F.M. , Provenzano, E. , Pharoah, P.D. , Caldas, C. , 2012. Aurora kinase A outperforms Ki67 as a prognostic marker in ER-positive breast cancer. Br. J. Cancer [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anaganti, S. , Fernandez-Cuesta, L. , Langerod, A. , Hainaut, P. , Olivier, M. , 2011. p53-dependent repression of focal adhesion kinase in response to estradiol in breast cancer cell-lines. Cancer Lett. 300, 215–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonios, D. , Rousseau, P. , Larange, A. , Kerdine-Romer, S. , Pallardy, M. , 2010. Mechanisms of IL-12 synthesis by human dendritic cells treated with the chemical sensitizer NiSO4 . J. Immunol. 185, 89–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ariazi, E.A. , Cunliffe, H.E. , Lewis-Wambi, J.S. , Slifker, M.J. , Willis, A.L. , Ramos, P. , Tapia, C. , Kim, H.R. , Yerrum, S. , Sharma, C.G. , Nicolas, E. , Balagurunathan, Y. , Ross, E.A. , Jordan, V.C. , 2011. Estrogen induces apoptosis in estrogen deprivation-resistant breast cancer through stress responses as identified by global gene expression across time. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 108, 18879–18886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barone, I. , Iacopetta, D. , Covington, K.R. , Cui, Y. , Tsimelzon, A. , Beyer, A. , Ando, S. , Fuqua, S.A. , 2010. Phosphorylation of the mutant K303R estrogen receptor alpha at serine 305 affects aromatase inhibitor sensitivity. Oncogene 29, 2404–2414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benten, W.P. , Stephan, C. , Lieberherr, M. , Wunderlich, F. , 2001. Estradiol signaling via sequestrable surface receptors. Endocrinology 142, 1669–1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouker, K.B. , Skaar, T.C. , Fernandez, D.R. , O'Brien, K.A. , Riggins, R.B. , Cao, D. , Clarke, R. , 2004. interferon regulatory factor-1 mediates the proapoptotic but not cell cycle arrest effects of the steroidal antiestrogen ICI 182,780 (faslodex, fulvestrant). Cancer Res. 64, 4030–4039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowie, M.L. , Dietze, E.C. , Delrow, J. , Bean, G.R. , Troch, M.M. , Marjoram, R.J. , Seewaldt, V.L. , 2004. Interferon-regulatory factor-1 is critical for tamoxifen-mediated apoptosis in human mammary epithelial cells. Oncogene 23, 8743–8755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, C.M. , Mulcahey, T.A. , Filipek, N.C. , Wise, P.M. , 2010. Production of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines during neuroinflammation: novel roles for estrogen receptors alpha and beta. Endocrinology 151, 4916–4925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burridge, K. , Wennerberg, K. , 2004. Rho and Rac take center stage. Cell 116, 167–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, C. , Khemtemourian, L. , Pelekanou, V. , Kampa, M. , Leclercq, G. , Sagan, S. , Castanas, E. , Burlina, F. , Jacquot, Y. , 2012. ERalpha17p, a peptide reproducing the hinge region of the estrogen receptor alpha associates to biological membranes: a biophysical approach. Steroids 77, 979–987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, S.B. , Graeber, C.T. , Quinn, J.A. , Filardo, E.J. , 2011. Retrograde transport of the transmembrane estrogen receptor, G-protein-coupled-receptor-30 (GPR30/GPER) from the plasma membrane towards the nucleus. Steroids 76, 892–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, S.B. , Quinn, J.A. , Graeber, C.T. , Filardo, E.J. , 2011. Down-modulation of the G-protein-coupled estrogen receptor, GPER, from the cell surface occurs via a trans-Golgi-proteasome pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 22441–22455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, R. , Shajahan, A.N. , Riggins, R.B. , Cho, Y. , Crawford, A. , Xuan, J. , Wang, Y. , Zwart, A. , Nehra, R. , Liu, M.C. , 2009. Gene network signaling in hormone responsiveness modifies apoptosis and autophagy in breast cancer cells. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 114, 8–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochrane, D.R. , Cittelly, D.M. , Howe, E.N. , Spoelstra, N.S. , McKinsey, E.L. , LaPara, K. , Elias, A. , Yee, D. , Richer, J.K. , 2010. MicroRNAs link estrogen receptor alpha status and Dicer levels in breast cancer. Horm. Cancer 1, 306–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane-Godreau, M.A. , Wira, C.R. , 2005. Effects of estradiol on lipopolysaccharide and Pam3Cys stimulation of CCL20/macrophage inflammatory protein 3 alpha and tumor necrosis factor alpha production by uterine epithelial cells in culture. Infect. Immun. 73, 4231–4237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danesh, S.M. , Kundu, P. , Lu, R. , Stefani, E. , Toro, L. , 2011. Distinct transcriptional regulation of human large conductance voltage- and calcium-activated K+ channel gene (hSlo1) by activated estrogen receptor alpha and c-Src tyrosine kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 31064–31071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diessenbacher, P. , Hupe, M. , Sprick, M.R. , Kerstan, A. , Geserick, P. , Haas, T.L. , Wachter, T. , Neumann, M. , Walczak, H. , Silke, J. , Leverkus, M. , 2008. NF-kappaB inhibition reveals differential mechanisms of TNF versus TRAIL-induced apoptosis upstream or at the level of caspase-8 activation independent of cIAP2. J. Invest. Dermatol. 128, 1134–1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichinger, C.S. , Jentsch, S. , 2011. 9-1-1: PCNA's specialized cousin. Trends Biochem. Sci. 36, 563–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essaghir, A. , Toffalini, F. , Knoops, L. , Kallin, A. , van Helden, J. , Demoulin, J.B. , 2010. Transcription factor regulation can be accurately predicted from the presence of target gene signatures in microarray gene expression data. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, e120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faulds, M.H. , Zhao, C. , Dahlman-Wright, K. , Gustafsson, J.A. , 2012. The diversity of sex steroid action: regulation of metabolism by estrogen signaling. J. Endocrinol. 212, 3–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felty, Q. , Xiong, W.C. , Sun, D. , Sarkar, S. , Singh, K.P. , Parkash, J. , Roy, D. , 2005. Estrogen-induced mitochondrial reactive oxygen species as signal-transducing messengers. Biochemistry 44, 6900–6909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filby, A.L. , Thorpe, K.L. , Tyler, C.R. , 2006. Multiple molecular effect pathways of an environmental oestrogen in fish. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 37, 121–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flannery, S.M. , Keating, S.E. , Szymak, J. , Bowie, A.G. , 2011. Human interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase-2 is essential for Toll-like receptor-mediated transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation of tumor necrosis factor alpha. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 23688–23697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frasor, J. , Danes, J.M. , Komm, B. , Chang, K.C. , Lyttle, C.R. , Katzenellenbogen, B.S. , 2003. Profiling of estrogen up- and down-regulated gene expression in human breast cancer cells: insights into gene networks and pathways underlying estrogenic control of proliferation and cell phenotype. Endocrinology 144, 4562–4574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freiss, G. , Chalbos, D. , 2011. PTPN13/PTPL1: an important regulator of tumor aggressiveness. Anticancer Agents Med. Chem. 11, 78–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo, D. , Jacquemotte, F. , Cleeren, A. , Laios, I. , Hadiy, S. , Rowlands, M.G. , Caille, O. , Nonclercq, D. , Laurent, G. , Jacquot, Y. , Leclercq, G. , 2007. Calmodulin-independent, agonistic properties of a peptide containing the calmodulin binding site of estrogen receptor alpha. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 268, 37–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo, D. , Jacquot, Y. , Cleeren, A. , Jacquemotte, F. , Laïos, I. , Laurent, G. , Leclercq, G. , 2007. Molecular basis of agonistic activity of ER 17p, a synthetic peptide corresponding to a sequence located at the N-terminal part of the estrogen receptor ligand binding domain. Lett. Drug Des. Discov. 4, 346–355. [Google Scholar]

- Gallo, D. , Haddad, I. , Duvillier, H. , Jacquemotte, F. , Laios, I. , Laurent, G. , Jacquot, Y. , Vinh, J. , Leclercq, G. , 2008. Trophic effect in MCF-7 cells of ERalpha17p, a peptide corresponding to a platform regulatory motif of the estrogen receptor alpha-underlying mechanisms. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 109, 138–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorlich, D. , Kostka, S. , Kraft, R. , Dingwall, C. , Laskey, R.A. , Hartmann, E. , Prehn, S. , 1995. Two different subunits of importin cooperate to recognize nuclear localization signals and bind them to the nuclear envelope. Curr. Biol. 5, 383–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He, B. , Feng, Q. , Mukherjee, A. , Lonard, D.M. , DeMayo, F.J. , Katzenellenbogen, B.S. , Lydon, J.P. , O'Malley, B.W. , 2008. A repressive role for prohibitin in estrogen signaling. Mol. Endocrinol. 22, 344–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heldring, N. , Pike, A. , Andersson, S. , Matthews, J. , Cheng, G. , Hartman, J. , Tujague, M. , Strom, A. , Treuter, E. , Warner, M. , Gustafsson, J.A. , 2007. Estrogen receptors: how do they signal and what are their targets. Physiol. Rev. 87, 905–931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houtman, R. , de Leeuw, R. , Rondaij, M. , Melchers, D. , Verwoerd, D. , Ruijtenbeek, R. , Martens, J.W. , Neefjes, J. , Michalides, R. , 2012. Serine-305 phosphorylation modulates estrogen receptor alpha binding to a coregulator peptide array, with potential application in predicting responses to tamoxifen. Mol. Cancer Ther. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacquot, Y. , Leclercq, G. , 2009. The ligand binding domain of ERa: mapping and functions. In Bartos J., Estrogens: Production, Functions and Applications Nova Ed. New York: [Google Scholar]

- Jafar-Nejad, H. , Norga, K. , Bellen, H. , 2002. Numb: “adapting” notch for endocytosis. Dev. Cell. 3, 155–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javelaud, D. , Alexaki, V.I. , Dennler, S. , Mohammad, K.S. , Guise, T.A. , Mauviel, A. , 2011. TGF-beta/SMAD/GLI2 signaling axis in cancer progression and metastasis. Cancer Res. 71, 5606–5610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, J.H. , Bhatia, A. , Toth, Z. , Oh, S. , Inn, K.S. , Liao, C.P. , Roy-Burman, P. , Melamed, J. , Coetzee, G.A. , Jung, J.U. , 2011. TPL2/COT/MAP3K8 (TPL2) activation promotes androgen depletion-independent (ADI) prostate cancer growth. PLoS One 6, e16205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, K.W. , Chodankar, R. , Purcell, D.J. , Bittencourt, D. , Stallcup, M.R. , 2012. Gene-specific patterns of coregulator requirements by estrogen receptor-alpha in breast cancer cells. Mol. Endocrinol. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jezierska, A. , Matysiak, W. , Motyl, T. , 2006. ALCAM/CD166 protects breast cancer cells against apoptosis and autophagy. Med. Sci. Monit. 12, BR263–BR273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jezierska, A. , Olszewski, W.P. , Pietruszkiewicz, J. , Olszewski, W. , Matysiak, W. , Motyl, T. , 2006. Activated Leukocyte Cell Adhesion Molecule (ALCAM) is associated with suppression of breast cancer cells invasion. Med. Sci. Monit. 12, BR245–BR256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, S. , Katayama, H. , Wang, J. , Li, S.A. , Hong, Y. , Radvanyi, L. , Li, J.J. , Sen, S. , 2012. Estrogen-induced aurora kinase-A (AURKA) gene expression is activated by GATA-3 in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer cells. Horm. Cancer 1, 11–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, C. , 2002. Historical perspective on hormonal therapy of advanced breast cancer. Clin. Ther. 24, (Suppl. A) A3–A16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kampa, M. , Pelekanou, V. , Gallo, D. , Notas, G. , Troullinaki, M. , Pediaditakis, I. , Charalampopoulos, I. , Jacquot, Y. , Leclercq, G. , Castanas, E. , 2011. ERalpha17p, an ERalpha P295-T311 fragment, modifies the migration of breast cancer cells, through actin cytoskeleton rearrangements. J. Cell. Biochem. 112, 3786–3796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kampa, M. , Notas, G. , Pelekanou, V. , Troullinaki, M. , Andrianaki, M. , Azariadis, K. , Kampouri, E. , Lavrentaki, K. , Castanas, E. , 2012. Early membrane initiated transcriptional effects of estrogens in breast cancer cells: first pharmacological evidence for a novel membrane estrogen receptor element (ERx). Steroids 77, 959–967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.H. , Yang, C.K. , Heo, K. , Roeder, R.G. , An, W. , Stallcup, M.R. , 2008. CCAR1, a key regulator of mediator complex recruitment to nuclear receptor transcription complexes. Mol. Cell. 31, 510–519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchhoff, S. , Sebens, T. , Baumann, S. , Krueger, A. , Zawatzky, R. , Li-Weber, M. , Meinl, E. , Neipel, F. , Fleckenstein, B. , Krammer, P.H. , 2002. Viral IFN-regulatory factors inhibit activation-induced cell death via two positive regulatory IFN-regulatory factor 1-dependent domains in the CD95 ligand promoter. J. Immunol. 168, 1226–1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjaerulff, O. , Verstreken, P. , Bellen, H.J. , 2002. Synaptic vesicle retrieval: still time for a kiss. Nat. Cell. Biol. 4, E245–E248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laios, I. , Journe, F. , Nonclercq, D. , Vidal, D.S. , Toillon, R.A. , Laurent, G. , Leclercq, G. , 2005. Role of the proteasome in the regulation of estrogen receptor alpha turnover and function in MCF-7 breast carcinoma cells. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 94, 347–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leclercq, G. , Lacroix, M. , Laios, I. , Laurent, G. , 2006. Estrogen receptor alpha: impact of ligands on intracellular shuttling and turnover rate in breast cancer cells. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets 6, 39–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leduc, A.M. , Trent, J.O. , Wittliff, J.L. , Bramlett, K.S. , Briggs, S.L. , Chirgadze, N.Y. , Wang, Y. , Burris, T.P. , Spatola, A.F. , 2003. Helix-stabilized cyclic peptides as selective inhibitors of steroid receptor-coactivator interactions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 100, 11273–11278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, S. , Wang, L. , Berman, M. , Kong, Y.Y. , Dorf, M.E. , 2011. Mapping a dynamic innate immunity protein interaction network regulating type I interferon production. Immunity 35, 426–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y. , Yang, J. , Li, S. , Zhang, J. , Zheng, J. , Hou, W. , Zhao, H. , Guo, Y. , Liu, X. , Dou, K. , Situ, Z. , Yao, L. , 2011. N-myc downstream-regulated gene 2, a novel estrogen-targeted gene, is involved in the regulation of Na+/K+-ATPase. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 32289–32299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B. , Lin, G. , Willingham, E. , Ning, H. , Lin, C.S. , Lue, T.F. , Baskin, L.S. , 2007. Estradiol upregulates activating transcription factor 3, a candidate gene in the etiology of hypospadias. Pediatr. Dev. Pathol. 10, 446–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu, S. , Becker, K.A. , Hagen, M.J. , Yan, H. , Roberts, A.L. , Mathews, L.A. , Schneider, S.S. , Siegelmann, H.T. , MacBeth, K.J. , Tirrell, S.M. , Blanchard, J.L. , Jerry, D.J. , 2008. Transcriptional responses to estrogen and progesterone in mammary gland identify networks regulating p53 activity. Endocrinology 149, 4809–4820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McManus, S. , Roux, S. , 2012. The adaptor protein p62/SQSTM1 in osteoclast signaling pathways. J. Mol. Signal. 7, 1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moats, R.K. , Ramirez, V.D. , 2000. Electron microscopic visualization of membrane-mediated uptake and translocation of estrogen-BSA: colloidal gold by Hep G2 cells. J. Endocrinol. 166, 631–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mootha, V.K. , Lindgren, C.M. , Eriksson, K.F. , Subramanian, A. , Sihag, S. , Lehar, J. , Puigserver, P. , Carlsson, E. , Ridderstrale, M. , Laurila, E. , Houstis, N. , Daly, M.J. , Patterson, N. , Mesirov, J.P. , Golub, T.R. , Tamayo, P. , Spiegelman, B. , Lander, E.S. , Hirschhorn, J.N. , Altshuler, D. , Groop, L.C. , 2003. PGC-1alpha-responsive genes involved in oxidative phosphorylation are coordinately downregulated in human diabetes. Nat. Genet. 34, 267–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Bueno, G. , Sanchez-Estevez, C. , Cassia, R. , Rodriguez-Perales, S. , Diaz-Uriarte, R. , Dominguez, O. , Hardisson, D. , Andujar, M. , Prat, J. , Matias-Guiu, X. , Cigudosa, J.C. , Palacios, J. , 2003. Differential gene expression profile in endometrioid and nonendometrioid endometrial carcinoma: STK15 is frequently overexpressed and amplified in nonendometrioid carcinomas. Cancer Res. 63, 5697–5702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moroianu, J. , Blobel, G. , Radu, A. , 1995. Previously identified protein of uncertain function is karyopherin alpha and together with karyopherin beta docks import substrate at nuclear pore complexes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 92, 2008–2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Notas, G. , Kampa, M. , Pelekanou, V. , Castanas, E. , 2011. Interplay of estrogen receptors and GPR30 for the regulation of early membrane initiated transcriptional effects: a pharmacological approach. Steroids 77, 943–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Donnell, M.A. , Ting, A.T. , 2010. Chronicles of a death foretold: dual sequential cell death checkpoints in TNF signaling. Cell Cycle 9, 1065–1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohshiro, K. , Schwartz, A.M. , Levine, P.H. , Kumar, R. , 2012. Alternate estrogen receptors promote invasion of inflammatory breast cancer cells via non-genomic signaling. PLoS One 7, e30725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang, H. , Cai, L. , Yang, Y. , Chen, X. , Sui, G. , Zhao, C. , 2011. Knockdown of osteopontin chemosensitizes MDA-MB-231 cells to cyclophosphamide by enhancing apoptosis through activating p38 MAPK pathway. Cancer Biother. Radiopharm. 26, 165–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelekanou, V. , Notas, G. , Sanidas, E. , Tsapis, A. , Castanas, E. , Kampa, M. , 2010. Testosterone membrane-initiated action in breast cancer cells: Interaction with the androgen signaling pathway and EPOR. Mol. Oncol. 4, 135–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelekanou, V. , Kampa, M. , Gallo, D. , Notas, G. , Troullinaki, M. , Duvillier, H. , Jacquot, Y. , Stathopoulos, E.N. , Castanas, E. , Leclercq, G. , 2011. The estrogen receptor alpha-derived peptide ERalpha17p (P(295)-T(311)) exerts pro-apoptotic actions in breast cancer cells in vitro and in vivo, independently from their ERalpha status. Mol. Oncol. 5, 36–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelekanou, V. , Notas, G. , Kampa, M. , Tsentelierou, E. , Radojicic, J. , Leclercq, G. , Castanas, E. , Stathopoulos, E.N. , 2011. ERalpha36, a new variant of the ERalpha is expressed in triple negative breast carcinomas and has a specific transcriptomic signature in breast cancer cell lines. Steroids 77, 928–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng, J. , Sengupta, S. , Jordan, V.C. , 2009. Potential of selective estrogen receptor modulators as treatments and preventives of breast cancer. Anticancer Agents Med. Chem. 9, 481–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennanen, P.T. , Sarvilinna, N.S. , Ylikomi, T.J. , 2009. Gene expression changes during the development of estrogen-independent and antiestrogen-resistant growth in breast cancer cell culture models. Anticancer Drugs 20, 51–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinhel, I. , Hills, M. , Drury, S. , Salter, J. , Sumo, G. , A'Hern, R. , Bliss, J.M. , Sestak, I. , Cuzick, J. , Barrett-Lee, P. , Harris, A. , Dowsett, M. , 2012. ER and HER2 expression are positively correlated in HER2 non-overexpressing breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 14, R46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Planas-Silva, M.D. , Waltz, P.K. , 2007. Estrogen promotes reversible epithelial-to-mesenchymal-like transition and collective motility in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 104, 11–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard, T.D. , 2003. The cytoskeleton, cellular motility and the reductionist agenda. Nature 422, 741–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pradhan, M. , Baumgarten, S.C. , Bembinster, L.A. , Frasor, J. , 2012. CBP mediates NF-kappaB-dependent histone acetylation and estrogen receptor recruitment to an estrogen response element in the BIRC3 promoter. Mol. Cell. Biol. 32, 569–575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratsep, R. , Kingo, K. , Karelson, M. , Reimann, E. , Raud, K. , Silm, H. , Vasar, E. , Koks, S. , 2008. Gene expression study of IL10 family genes in vitiligo skin biopsies, peripheral blood mononuclear cells and sera. Br. J. Dermatol. 159, 1275–1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rau, S.W. , Dubal, D.B. , Bottner, M. , Wise, P.M. , 2003. Estradiol differentially regulates c-Fos after focal cerebral ischemia. J. Neurosci. 23, 10487–10494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid, G. , Hubner, M.R. , Metivier, R. , Brand, H. , Denger, S. , Manu, D. , Beaudouin, J. , Ellenberg, J. , Gannon, F. , 2003. Cyclic, proteasome-mediated turnover of unliganded and liganded ERalpha on responsive promoters is an integral feature of estrogen signaling. Mol. Cell. 11, 695–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyna-Neyra, A. , Camacho-Arroyo, I. , Ferrera, P. , Arias, C. , 2002. Estradiol and progesterone modify microtubule associated protein 2 content in the rat hippocampus. Brain Res. Bull. 58, 607–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzo, P. , Miao, H. , D'Souza, G. , Osipo, C. , Song, L.L. , Yun, J. , Zhao, H. , Mascarenhas, J. , Wyatt, D. , Antico, G. , Hao, L. , Yao, K. , Rajan, P. , Hicks, C. , Siziopikou, K. , Selvaggi, S. , Bashir, A. , Bhandari, D. , Marchese, A. , Lendahl, U. , Qin, J.Z. , Tonetti, D.A. , Albain, K. , Nickoloff, B.J. , Miele, L. , 2008. Cross-talk between notch and the estrogen receptor in breast cancer suggests novel therapeutic approaches. Cancer Res. 68, 5226–5235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez, A.L. , Tamrazi, A. , Collins, M.L. , Katzenellenbogen, J.A. , 2004. Design, synthesis, and in vitro biological evaluation of small molecule inhibitors of estrogen receptor alpha coactivator binding. J. Med. Chem. 47, 600–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubio, M.F. , Fernandez, P.N. , Alvarado, C.V. , Panelo, L.C. , Grecco, M.R. , Colo, G.P. , Martinez-Noel, G.A. , Micenmacher, S.M. , Costas, M.A. , 2012. Cyclin D1 is a NF-kappaB corepressor. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1823, 1119–1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saint-Criq, V. , Rapetti-Mauss, R. , Yusef, Y.R. , Harvey, B.J. , 2012. Estrogen regulation of epithelial ion transport: Implications in health and disease. Steroids 77, 918–923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez, A.M. , Flamini, M.I. , Baldacci, C. , Goglia, L. , Genazzani, A.R. , Simoncini, T. , 2010. Estrogen receptor-alpha promotes breast cancer cell motility and invasion via focal adhesion kinase and N-WASP. Mol. Endocrinol. 24, 2114–2125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savkur, R.S. , Burris, T.P. , 2004. The coactivator LXXLL nuclear receptor recognition motif. J. Pept. Res. 63, 207–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz, A.A. , Govek, E.E. , Bottner, B. , Van Aelst, L. , 2000. Rho GTPases: signaling, migration, and invasion. Exp. Cell. Res. 261, 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schutze, S. , Potthoff, K. , Machleidt, T. , Berkovic, D. , Wiegmann, K. , Kronke, M. , 1992. TNF activates NF-kappa B by phosphatidylcholine-specific phospholipase C-induced “acidic” sphingomyelin breakdown. Cell 71, 765–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, J.L. , Shajahan, A.N. , Clarke, R. , 2011. The role of interferon regulatory factor-1 (IRF1) in overcoming antiestrogen resistance in the treatment of breast cancer. Int. J. Breast Cancer 2011, 912102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scorah, J. , McGowan, C.H. , 2009. Claspin and Chk1 regulate replication fork stability by different mechanisms. Cell Cycle 8, 1036–1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebastian, T. , Sreeja, S. , Thampan, R.V. , 2004. Import and export of nuclear proteins: focus on the nucleocytoplasmic movements of two different species of mammalian estrogen receptor. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 260, 91–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidlova-Wuttke, D. , Becker, T. , Christoffel, V. , Jarry, H. , Wuttke, W. , 2003. Silymarin is a selective estrogen receptor beta (ERbeta) agonist and has estrogenic effects in the metaphysis of the femur but no or antiestrogenic effects in the uterus of ovariectomized (ovx) rats. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 86, 179–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]