Abstract

Cataract is the most frequent cause of blindness worldwide and is treated by surgical removal of the opaque lens to restore the light path to the retina. While cataract surgery is a safe procedure, some patients develop a complication of the surgery involving opacification and wrinkling of the posterior lens capsule. This process, called posterior capsule opacification (PCO), requires a second clinical treatment that can in turn lead to additional complications. Prevention of PCO is a current unmet need in the vision care enterprise. The pathogenesis of PCO involves the transition of lens epithelial cells to a mesenchymal phenotype, designated epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT). Our previous studies showed that transgenic mice designed for overexpression of human aldose reductase developed lens defects reminiscent of PCO. In the current study, we evaluated the impact of aldose reductase (AR) on expression of expression of EMT markers in the lens. Primary lens epithelial cells from AR-transgenic mice showed downregulated expression of Foxe3 and Pax6 and increased expression of α-SMA, fibronectin and snail, a pattern of gene expression typical of cells undergoing EMT. A role for AR in these changes was further confirmed when we observed that they could be normalized by treatment of cells with Sorbinil, an AR inhibitor. Smad-dependent and Smad-independent pathways are known to contribute to EMT. Interestingly, AR overexpression induced ERK but not Smad-2 activation. These results suggest that elevation of AR may lead to activation of ERK signaling and thus play a role in TGF-β/Smad independent induction of EMT in lens epithelial cells.

Keywords: Aldose reductase, PCO, EMT, ERK

Introduction

Posterior capsular opacification (PCO) is the most common complication of cataract surgery and occurs in up to approximately 25–30 percent of patients [1]. Surgical removal of the cataractous lens mass usually results in some quantity of lens epithelial cells (LEC) left behind due to their adherence to the inner lining of the capsular bag. Following surgery, these LEC are exposed to transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) that becomes elevated in the eye as part of the surgical wound response [2]. Engagement of the TGF-β receptor expressed on the cell surface of LECs induces them to undergo epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), a process that leads to migration of LECs to the posterior aspect of the lens capsular bag. During the EMT process, LECs begin to secrete extracellular matrix proteins and induce fibrosis and wrinkling of the capsular bag. These changes reduce the transparency of the postsurgical capsular bag, which results in a severe degradation of visual acuity due to scattering of light that should be focused on the retina. To recreate the visual axis in lenses with PCO, treatment with a Nd:YAG is used to produce a capsulotomy. However, this procedure adds additional costs to cataract care as well as increased risk for subsequent complications such as retinal detachment and retinal edema [3]. Therefore, an alternative strategy is needed for alleviating the onset and/or progression of PCO.

Initiation of the postsurgical EMT response in the lens is thought to be stimulated primarily by TGF-β2 [4]. EMT markers such as α-smooth muscle actin (αSMA) and fibronectin are upregulated by TGF-β in the progression of PCO [4, 5]. In addition, TGF-β-induced EMT increases matrix proteins such as secreted protein acidic rich in cysteine (SPARC) [6] and matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) [7, 8], which are known to be involved in cell migration. In previous studies we showed that aldose reductase (AR) can play a role in the TGF-β-mediated EMT response through interactions the Smad protein family of signaling proteins [9]. In a similar manner, Nahomi and colleagues showed that αB-crystallin plays an essential role for the TGF-β2-mediated EMT of LECs [10].

Aldose reductase (AR), is an NADPH-dependent aldo-keto reductase very well studied as a catalyst of glucose conversion to sorbitol in the polyol pathway [11, 12]. In the diabetic lens characterized by chronically high levels of glucose, AR is responsible for production of high levels of sorbitol and associated osmotic and oxidative stress [13, 14]. AR is also implicated in the pathogenesis of diabetic retinopathy, but most likely through its role in promoting inflammation in retinal cells such as retinal microglia and endothelial cells of the retinal vasculature [15, 16]. In our previous studies of AR-mediated pathogenesis of diabetic eye disease, we observed that a strain of transgenic mice designed for over-expression of human AR (AKR1B1) in the lens developed anterior subcapsular cataracts even in the absence of diabetes and hyperglycemia [17]. Histological analysis of cells associated with the subcapsular cataract revealed high levels of αSMA, a protein that is considered a key marker of cells that have undergone EMT. The aim of the present study was to further evaluate the impact of AR expression on markers of EMT in the lens. To do so we compared the expression of EMT marker genes in primary cultures of LEC from mutant mouse strains that either over-express human AR (AR-Tg) or are null for expression of AR (AR knock out, ARKO). Our studies revealed that elevated AR increases the basal expression levels of EMT marker genes such as αSMA, fibronectin, and Snail. In addition, elevated levels of activated ERK1/2 were observed in cells of AR-Tg mice, suggesting that the EMT-like phenotype of cells containing elevated levels of AR may be influenced by the activation of Smad-independent signaling pathways.

Materials and Methods

Materials and cell culture

Sorbinil was generously provided by Pfizer Center Research (Groton, CT, USA). Primary lens capsular epithelial cells were isolation from lenses of mice. Briefly lenses were collected from 6–10 week old mice and washed in 1x Hanks Balanced Salts Solution. After removal of the lens mass, the remaining dissected capsules were then placed in 1 ml 0.05% Trypsin-EDTA and incubated in a humidified atmosphere at 5% CO2, 37 °C for 15 min. 1 ml of complete DMEM media (containing 20% fetal bovine serum and 0.1% fungizone, units/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin) were added and centrifuged at 1000 rpm for 10 min. The pellet was resuspended in complete DMEM media and incubated in humidified atmosphere at 5% CO2, 37 °C.

Animals and treatments

This research was conducted in compliance with ARVO statement for the use of animals in ophthalmic and vision research. C57BL/6 wildtype (WT) mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). AR transgenic mice (strain Par40) and AR null (ARKO) were generated from previous studies [13, 18]. Animal work was approved by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at University of Colorado. All experimental mice were also genotyped as homozygous for the wild type allele of the retinal degeneration rd8 mutation [19].

Western blotting

Cells were collected in Laemmli sample buffer (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and heated to 100 °C for 10 min. Proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ, USA), using a wet blotter (Bio-Rad). Membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat milk and then probed with primary antibodies: rabbit anti- p-ERK, ERK, fibronectin, p-Smad2, Smad2 (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., Danvers, MA, USA) or mouse anti-β-actin (1:4000, Sigma-Aldrich) or rabbit anti-AR (1:1000) [20] overnight at 4 °C. Membranes were washed and probed with secondary antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA), and developed with the Western Blot Substrate kit (Bio-Rad) by detecting chemiluminescence using a Bio-Rad ChemiDoc™ XRS+ imaging system.

Real time PCR

Total RNA was isolated from primary lens capsular epithelial cells according to the manufacturer’s protocol (RNeasy Microarray Tissue Mini Kit, Qiagen). RNA (5 μg) was reverse transcribed using iScript™ cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad). For real-time PCR, the iTaq™ Universal SYBR® Green Supermix (Bio-Rad) was used according to the manufacturer’s protocol on a CFX Connect™ Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad). The primers for murine MMP-2, MMP-9, TGF-β2, Foxe3, Pax6, α-SMA, E-cadherin, Fibronectin and Snail were directly designed by Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA, USA). The thermocycler parameters were 94 °C for 5 min, followed by 40 cycles of 94 °C for 30 sec, 56 °C for 30 sec and 72 °C for 60 sec. GADPH and actin were used as internal control. All real-time PCR data was analyzed by 2ΔCt.

Immunohistochemistry

Eye globes of WT and AR-Tg mice were embedded in paraffin. Paraffin embedded lens sections (10 μm) were subjected to antigen retrieval and blocking of endogenous peroxidase activity. The sections were then incubated with rabbit monoclonal α-SMA (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) antibody in PBS for 2 h at 37 °C in humidity chamber. Rabbit IgG antibody (DAKO, Carpinteria, CA, USA) was used as a negative control. After washing three times in PBS, the sections were incubated with biotinylated secondary antibody for 1 h followed by HRP conjugated streptavidin (DAKO) in PBS for 30 min. The sections were then incubated in DAB working solution for 10 min at RT and counterstained with diluted hematoxylin for 2 min followed by dehydration and mounting for microscopic observation. The brown colored cytoplasmic staining indicates α-SMA. Immunohistochemical staining intensity was quantified essentially as previously described [21, 22].

Statistical analysis

Results are shown as the Means ± SEM of at least three experiments. Data were analyzed by ANOVA with Tukey’s test with P value of <0.05 considered significant.

Results

AR overexpression induces TGF-β2 gene expression but downregulates Foxe3 and Pax6 gene expression

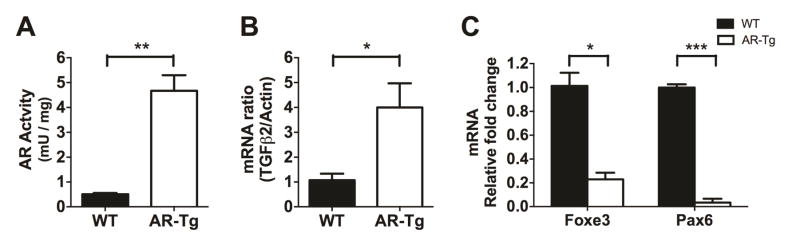

TGF-β2 is an inducer of EMT, which plays a very crucial role in cell fibrosis during PCO development [23]. Here we investigated the effect of AR on TGF-β2 and EMT activation. To study the effect of AR on EMT marker expression, protein or RNA samples were collected from lens capsular epithelial cells of WT and AR-Tg mice. AR enzymatic activity measured in the direction of DL-glyceraldehyde reduction is about 4.5-fold higher in AR-Tg lens as compared to WT (Fig 1A). When measured by qPCR, we observed that mRNA transcripts for TGF-β2 were also elevated in the AR-Tg lens as compared to WT (Fig 1B). This finding is consistent with previous study showing that AR mediates TGF-β expression [24]. Foxe3 and Pax6 are well-known transcription factors that are considered markers of lens epithelium [25, 26]. While transcripts derived from both of these LEC marker genes were detected in primary cell cultures from WT and AR-Tg lenses, the levels of Foxe3 and Pax6 were dramatically reduced in cells from the AR-Tg as compared to WT (Fig 1C). These results indicate that epithelial cells grown from the AR-Tg lens have already initiated the first steps of transition to a mesenchymal phenotype, and thus toward development of PCO [26].

Fig. 1. Aldose reductase elevation promotes TGF-β2 expression but attenuates Foxe3 and Pax6 expression.

Primary lens capsular epithelial cells were isolated from WT and AR-Tg mice and cultured in the normal medium for 48 h before harvested. AR enzymatic activity (A) was quantitated using DL-glyceraldehyde as substrate. mRNAs of TGF-β2 (B), Foxe3 and Pax6 (C) were measured by qPCR in WT and AR-Tg groups. Data shown are means ± SEM (N = 3). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.005.

AR overexpression elevates TGF-β2 expression and Smad-independent EMT activation

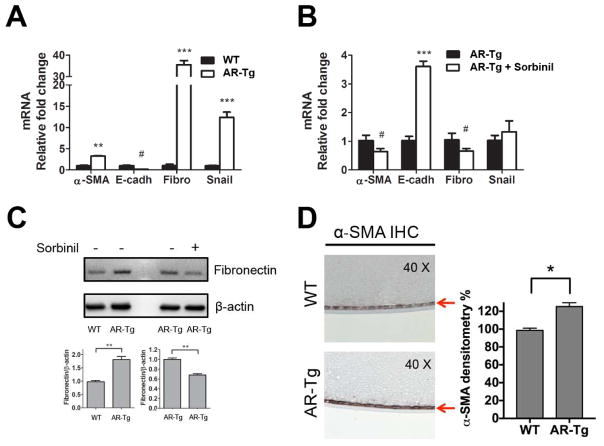

EMT is an important process that leads to PCO formation. To examine the effect of AR expression on EMT under basal conditions (no lens surgery), we used qPCR to compare age-matched WT and AR-Tg lenses for the abundance of EMT marker gene transcripts. As shown in Figure 2A, transcripts for α-SMA, fibronectin and Snail were significantly increased and E-cadherin was decreased in AR-Tg compared to WT group. As an additional means to test the role of AR in EMT, we compared the abundance of EMT marker gene transcripts in AR-Tg cultures with and without treatment with Sorbinil, a well-known AR inhibitor. Sorbinil treatment reduced α-SMA and fibronectin expression (p<0.05) and very dramatically induced E-cadherin expression (p<0.005) but had only a modest influence on snail expression (Fig 2B). We consider it possible that the modest influence of Sorbinil on snail results from the short duration of inhibitor treatment. Consistent with qPCR results, protein levels of fibronectin detected by Western blotting (Fig 2C) were significantly elevated in AR-Tg vs WT (p<0.01) and could be reduced in the AR-Tg cells by Sorbinil treatment (p<0.01). When examined in lens tissues dissected from animal models, we observed substantially heavier (25%) immunohistochemical staining for α-SMA in the capsule-epithelium of AR-Tg mice as compared to WT mice (Fig 2D). These data clearly show that AR overexpression in lens enhances EMT marker expression in vivo.

Fig. 2. Aldose reductase regulates EMT marker expression.

mRNA was extracted from primary lens capsular epithelial cells of WT and AR-Tg mice. EMT markers mRNA including α-SMA, E-cadherin (E-cad), Fibronectin (Fibro) and Snail were measured in the comparison of WT and AR-Tg (A) or AR-Tg with/without Sorbinil (10 μM) for 48 h (B). Protein level of fibronectin in the either comparison of WT and AR-Tg or AR-Tg with/without Sorbinil (10 μM) was probed using Western blot (C). IHC staining of α-SMA was detected in lens capsule (red arrow) of WT and AR-Tg mice (D). Data shown are means ± SEM (N = 3). # represents the significant upregulation. * represents the significant downregulation. #P, < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.005.

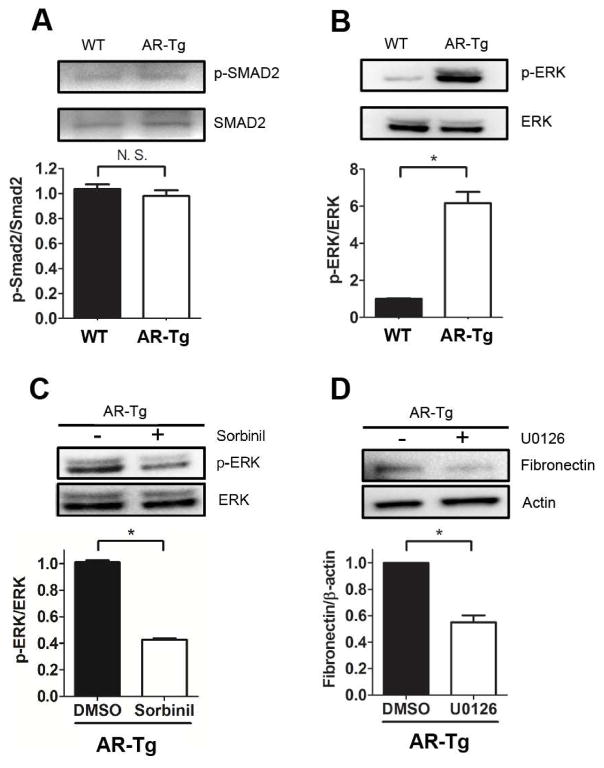

TGF-β-induced Smad activation is considered a critical step in EMT [27]. Given the high basal levels of EMT markers observed in the native lens of AR-Tg mice, we thought we might find elevated levels of phosphorylated Smad proteins that typically signal downstream from the TGF-β receptor [28]. However, no apparent difference was observed in the abundance of phospho-Smad2 in primary cultures of LEC from WT and AR-Tg lenses (Fig 3A). This result indicates that AR may have a role in stimulating EMT marker gene expression in a manner independent of Smad signaling. For example, others have shown that TGF-β2 induces Smad- independent EMT production by initiating MAP signaling kinases (RAS/MEK/ERK) [27]. Indeed, dramatically elevated levels of phospho-ERK2/3 (p<0.05 vs WT) in AR-Tg mice (Fig 3B) can be substantially reduced by treatment of cells with Sorbinil (Fig 3C). These data suggest that AR may play some role in regulating the ERK signaling pathway. The involvement of ERK signaling in driving expression of EMT markers was also suggested by results obtained with the ERK inhibitor U0126. In addition, U0126 treatment of LEC from AR-Tg mice reduced fibronectin expression by about 50% (p<0.05 vs inhibitor control; Fig 3D), suggesting the involvement of ERK in EMT process. Further studies will be required to understand the linkage between elevated AR expression and ERK activation.

Fig. 3. Aldose reductase mediates ERK activation and its downstream EMT expression.

Protein was extracted from primary lens capsular epithelial cells of WT and AR-Tg mice. p-Smad2 and total Smad2 (A), p-ERK and total ERK from WT and AR-Tg were measured by Western blot. Cells from AR-Tg were treated with Sorbinil (10 μM) for 48 h and probed with p-ERK and ERK (C) or treated with U0126 (10 μM) for 24 h and probed with fibronectin (D). Data shown are means ± SEM (N = 3). *P < 0.05.

Discussion

Cataract is one of the major causes of blindness among the world [29, 30]. Surgical removal of the opaque cataractous lens is a relatively safe procedure and results in a dramatic improvement in vision and quality of life. However, the wound response of the eye following removal of the degenerate lens can produce unwanted proliferation of lens epithelial cells left in the capsular bag following surgery. These cells undergo EMT as part of the wound response and cause PCO, a fibrotic wrinkling of the capsular bag and interruption of the light path needed to convey visual information to the retina. The end result of PCO is reduced visual acuity and significantly compromised quality of life to the patient and caregivers. Given the prevalence of cataract and the relatively high rate of PCO development following cataract surgery, especially among young patients [31], there is an urgent need for therapies to prevent cellular changes that lead to this blinding condition.

Previous studies from our lab and those from Ramana and Srivastava have shown that AR inhibition attenuates cell proliferation, cell migration and EMT process on LECs [9, 32]. In this study, we investigated different level of AR expression on primary LECs. We observed the elevation of TGF-β2 gene in the LECs of AR-Tg mice in the comparison to WT mice (Fig 1B). Elevation of AR increases flux of AR polyol pathway, which produces more oxidative stress due to NADPH/NADP+ and NAD+/NADH imbalance. Since oxidative stress is one of the mediators to induce TGF-β expression [33], AR-induced TGF-β2 elevation might be the result of oxidative stress (Fig 1B). Foxe3 and Pax6 are markers expressed in lens and would be attenuated under TGF-β2-induced EMT process [25, 26]. We found both genes were dramatically downregulated in AR-Tg compared to WT mice (Fig 1C), which suggests the EMT process is elevated by high levels of AR. We further investigated the EMT gene expression in WT and AR-Tg groups. We observed an increase in gene expression including α-SMA, fibronectin and Snail in LEC cultured from lenses of transgenic mice, and the elevated expression levels could be reduced by Sorbinil treatment (Fig 2A and B). These data suggest that AR positively regulates EMT production and AR inhibition reduces it. Western blotting of fibronectin presented consistent results with gene transcript expression data (Fig 2C). To further demonstrate the AR effect in vivo, we utilized immunohistochemical staining of α-SMA on the sections from WT and AR-Tg mice. Data showed that α-SMA expression is higher in transgenics compared to WT mice (Fig 2D). In vitro and in vivo studies demonstrate the positive correlation of AR and EMT production. AR levels are elevated in diabetic patients [34]. Cataract occurs more frequently in diabetic patients and surgical removal of the opaque lens is the most common therapy. Since AR induces EMT marker expression, there would be an increased risk of PCO formation after diabetic cataract removal. In an potentially related area, it is interesting to note that fructose, the end product of AR polyol pathway, has been demonstrated to form advanced glycated end-products (AGEs) much faster than glucose [35]. Raghavan and colleagues recently reported that AGEs in lens capsule enhance EMT of LECs under TGF-β2 treatment [36, 37]. Accordingly, AR-induced AGEs production might be another stimulus for PCO development following cataract surgery.

Overexpression of AR in a transgenic mouse model leads to a capsular cataract phenotype involving proliferation and formation of a fibrotic plaque of cells reminiscent of cells at the posterior capsule in PCO [17]. To investigate the molecular mechanism that could link AR expression to this phenotype, we examined Smad-dependent and Smad-independent signaling pathways. The Smad signaling pathway downstream from the receptor has been shown to play a crucial role in PCO development [38, 39]. TGF-β binding to its cell surface receptor induces a recruitment of Smad-2 and Smad-3 to the receptor complex where they are phosphorylated by receptor kinases and subsequently associate with Smad-4 and translocate to the nucleus to activate the transcription of a variety of genes involved in EMT. In our comparison of epithelial cells from lenses of WT and AR-Tg mice, we observed no significant difference in p-Smad2 activation (Fig 3A). Thus, overexpression of AR was not sufficient to increase basal levels of p-Smad2 even though the basal level of the EMT markers aSMA and fibronectin were increased over WT (Figs 2A and 2D). Thus, AR overexpression resulted in the activation of a Smad-independent pathway that caused the upregulation of some EMT markers. Other than the TGF-β2-stimulated Smads signaling pathway, PCO development could be mediated by MAP signaling kinases (RAS/MEK/ERK) [27, 40]. We observed that AR overexpression induces ERK activation (Fig 3B) indicating that AR-induced EMT elevation may involve a Smad-independent pathway. To understand the effect of AR on ERK activation, lens epithelial cells from AR-Tg mice were incubated in the presence or absence of Sorbinil. We observed that Sorbinil treatment reduced AR-induced ERK activation (Fig 3C). To further confirm that AR-induced EMT process is mediated by ERK activation, we observed that AR-Tg LECs treated with the ERK inhibitor U0126 expressed less fibronectin as compared to WT (Fig 3D). These results suggest that AR may influence EMT progression in a process mediated not only by Smad signaling downstream from the TGF-β2- receptor [9] but also through a process involving ERK activation. AR plays a role in the conversion aldehydes such as 4-hydroxy-trans-2-nonenal (4-HNE) into 1,4-dihydroxynonene (DHN) [41], which induces more oxidative stress. Consequently, it is possible that the AR effects observed here could be due to the aldehyde reducing capacity of the enzyme, rather than its role in glucose metabolism. Understanding the complexity of these mechanisms may provide clues to alternative therapeutic strategies, such as blockade of ERK signaling, for PCO prevention after cataract surgery.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Increased levels of AR in lens increase the expression of genes associated with EMT

AR overexpression induced ERK but not Smad-2 activation

ERK inhibition attenuates fibronectin expression in AR-Tg lens capsular epithelial cells

AR-dependent ERK activation may play a role in TGF-β/Smad independent induction of EMT in lens epithelial cells

Acknowledgments

This study is supported by NIH grants EY005856 and EY021498 and by a Challenge Grant from Research to Prevent Blindness.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Wormstone IM. Posterior capsule opacification: a cell biological perspective. Experimental Eye Research. 2002;74:337–347. doi: 10.1006/exer.2001.1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wallentin N, Wickstrom K, Lundberg C. Effect of cataract surgery on aqueous TGF-beta and lens epithelial cell proliferation. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 1998;39:1410–1418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karahan E, Er D, Kaynak S. An Overview of Nd:YAG Laser Capsulotomy. Medical hypothesis, discovery and innovation in ophthalmology. 2014;3:45–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hales AM, Schulz MW, Chamberlain CG, McAvoy JW. TGF-beta 1 induces lens cells to accumulate alpha-smooth muscle actin, a marker for subcapsular cataracts. Current eye research. 1994;13:885–890. doi: 10.3109/02713689409015091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ignotz RA, Massague J. Transforming growth factor-beta stimulates the expression of fibronectin and collagen and their incorporation into the extracellular matrix. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1986;261:4337–4345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gotoh N, Perdue NR, Matsushima H, Sage EH, Yan Q, Clark JI. An in vitro model of posterior capsular opacity: SPARC and TGF-beta2 minimize epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in lens epithelium. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 2007;48:4679–4687. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wormstone IM, Wang L, Liu CS. Posterior capsule opacification. Exp Eye Res. 2009;88:257–269. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2008.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zelenka PS, Arpitha P. Coordinating cell proliferation and migration in the lens and cornea. Seminars in cell & developmental biology. 2008;19:113–124. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang KC, Petrash JM. Aldose Reductase Mediates Transforming Growth Factor beta2 (TGF-beta2)-Induced Migration and Epithelial-To-Mesenchymal Transition of Lens-Derived Epithelial Cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015;56:4198–4210. doi: 10.1167/iovs.15-16557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nahomi RB, Pantcheva MB, Nagaraj RH. alphaB-crystallin is essential for the TGF-beta2-mediated epithelial to mesenchymal transition of lens epithelial cells. Biochem J. 2016;473:1455–1469. doi: 10.1042/BCJ20160128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Petrash JM. All in the family: aldose reductase and closely related aldo-keto reductases. Cellular and molecular life sciences: CMLS. 2004;61:737–749. doi: 10.1007/s00018-003-3402-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kinoshita JH, Nishimura C. The involvement of aldose reductase in diabetic complications. Diabetes-Metabolism Reviews. 1988;4:323–337. doi: 10.1002/dmr.5610040403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Snow A, Shieh B, Chang KC, Pal A, Lenhart P, Ammar D, Ruzycki P, Palla S, Reddy GB, Petrash JM. Aldose reductase expression as a risk factor for cataract. Chem Biol Interact. 2015;234:247–253. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2014.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee AY, Chung SK, Chung SS. Demonstration that polyol accumulation is responsible for diabetic cataract by the use of transgenic mice expressing the aldose reductase gene in the lens. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1995;92:2780–2784. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.7.2780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chang KC, Ponder J, Labarbera DV, Petrash JM. Aldose reductase inhibition prevents endotoxin-induced inflammatory responses in retinal microglia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55:2853–2861. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-13487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tang J, Kern TS. Inflammation in diabetic retinopathy. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2011;30:343–358. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zablocki GJ, Ruzycki PA, Overturf MA, Palla S, Reddy GB, Petrash JM. Aldose reductase-mediated induction of epithelium-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in lens. Chemico-Biological Interactions. 2011;191:351–356. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2011.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ho HT, Chung SK, Law JW, Ko BC, Tam SC, Brooks HL, Knepper MA, Chung SS. Aldose reductase-deficient mice develop nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. Molecular and cellular biology. 2000;20:5840–5846. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.16.5840-5846.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mattapallil MJ, Wawrousek EF, Chan CC, Zhao H, Roychoudhury J, Ferguson TA, Caspi RR. The Rd8 mutation of the Crb1 gene is present in vendor lines of C57BL/6N mice and embryonic stem cells, and confounds ocular induced mutant phenotypes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53:2921–2927. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-9662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang SP, Palla S, Ruzycki P, Varma RA, Harter T, Reddy GB, Petrash JM. Aldo-keto reductases in the eye. Journal of ophthalmology. 2010;2010:521204. doi: 10.1155/2010/521204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nguyen DH, Zhou T, Shu J, Mao J-H. Quantifying chromogen intensity in immuohistochemistry via reciprocal intensity. Cancer InCytes. 2013e;2 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamaleyeva LM, Pulgar VM, Lindsey SH, Yamane L, Varagic J, McGee C, daSilva M, Lopes Bonfa P, Gurley SB, Brosnihan KB. Uterine artery dysfunction in pregnant ACE2 knockout mice is associated with placental hypoxia and reduced umbilical blood flow velocity. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2015;309:E84–94. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00596.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wormstone IM, Tamiya S, Anderson I, Duncan G. TGF-beta2-induced matrix modification and cell transdifferentiation in the human lens capsular bag. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 2002;43:2301–2308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang P, Xing K, Randazzo J, Blessing K, Lou MF, Kador PF. Osmotic stress, not aldose reductase activity, directly induces growth factors and MAPK signaling changes during sugar cataract formation. Experimental eye research. 2012;101:36–43. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2012.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wormstone IM, Tamiya S, Eldred JA, Lazaridis K, Chantry A, Reddan JR, Anderson I, Duncan G. Characterisation of TGF-beta2 signalling and function in a human lens cell line. Experimental eye research. 2004;78:705–714. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2003.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mansfield KJ, Cerra A, Chamberlain CG. FGF-2 counteracts loss of TGFbeta affected cells from rat lens explants: implications for PCO (after cataract) Molecular vision. 2004;10:521–532. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dawes LJ, Sleeman MA, Anderson IK, Reddan JR, Wormstone IM. TGFbeta/Smad4-dependent and -independent regulation of human lens epithelial cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:5318–5327. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-3223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Derynck R, Zhang YE. Smad-dependent and Smad-independent pathways in TGF-beta family signalling. Nature. 2003;425:577–584. doi: 10.1038/nature02006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rowe NG, Mitchell PG, Cumming RG, Wans JJ. Diabetes, fasting blood glucose and age-related cataract: the Blue Mountains Eye Study. Ophthalmic epidemiology. 2000;7:103–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leske MC, Wu SY, Hennis A, Connell AM, Hyman L, Schachat A. Diabetes, hypertension, and central obesity as cataract risk factors in a black population. The Barbados Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 1999;106:35–41. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(99)90003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dawes LJ, Duncan G, Wormstone IM. Age-related differences in signaling efficiency of human lens cells underpin differential wound healing response rates following cataract surgery. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54:333–342. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-10425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yadav UC, Ighani-Hosseinabad F, van Kuijk FJ, Srivastava SK, Ramana KV. Prevention of posterior capsular opacification through aldose reductase inhibition. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 2009;50:752–759. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barcellos-Hoff MH, Dix TA. Redox-mediated activation of latent transforming growth factor-beta 1. Mol Endocrinol. 1996;10:1077–1083. doi: 10.1210/mend.10.9.8885242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nishimura C, Saito T, Ito T, Omori Y, Tanimoto T. High levels of erythrocyte aldose reductase and diabetic retinopathy in NIDDM patients. Diabetologia. 1994;37:328–330. doi: 10.1007/BF00398062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sadowska-Bartosz I, Galiniak S, Bartosz G. Kinetics of glycoxidation of bovine serum albumin by glucose, fructose and ribose and its prevention by food components. Molecules. 2014;19:18828–18849. doi: 10.3390/molecules191118828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Raghavan CT, Nagaraj RH. AGE-RAGE interaction in the TGFbeta2-mediated epithelial to mesenchymal transition of human lens epithelial cells. Glycoconj J. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s10719-016-9686-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Raghavan CT, Smuda M, Smith AJ, Howell S, Smith DG, Singh A, Gupta P, Glomb MA, Wormstone IM, Nagaraj RH. AGEs in human lens capsule promote the TGFbeta2-mediated EMT of lens epithelial cells: implications for age-associated fibrosis. Aging cell. 2016;15:465–476. doi: 10.1111/acel.12450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li J, Tang X, Chen X. Comparative effects of TGF-beta2/Smad2 and TGF-beta2/Smad3 signaling pathways on proliferation, migration, and extracellular matrix production in a human lens cell line. Exp Eye Res. 2011;92:173–179. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2011.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li H, Yuan X, Li J, Tang X. Implication of Smad2 and Smad3 in transforming growth factor-beta-induced posterior capsular opacification of human lens epithelial cells. Current eye research. 2015;40:386–397. doi: 10.3109/02713683.2014.925932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Derynck R, Akhurst RJ, Balmain A. TGF-beta signaling in tumor suppression and cancer progression. Nature genetics. 2001;29:117–129. doi: 10.1038/ng1001-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Srivastava S, Dixit BL, Cai J, Sharma S, Hurst HE, Bhatnagar A, Srivastava SK. Metabolism of lipid peroxidation product, 4-hydroxynonenal (HNE) in rat erythrocytes: role of aldose reductase. Free radical biology & medicine. 2000;29:642–651. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00351-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.