Significance

Our work addresses the question of compelling killer applications for quantum computers. Although quantum chemistry is a strong candidate, the lack of details of how quantum computers can be used for specific applications makes it difficult to assess whether they will be able to deliver on the promises. Here, we show how quantum computers can be used to elucidate the reaction mechanism for biological nitrogen fixation in nitrogenase, by augmenting classical calculation of reaction mechanisms with reliable estimates for relative and activation energies that are beyond the reach of traditional methods. We also show that, taking into account overheads of quantum error correction and gate synthesis, a modular architecture for parallel quantum computers can perform such calculations with components of reasonable complexity.

Keywords: quantum computing, quantum algorithms, reaction mechanisms

Abstract

With rapid recent advances in quantum technology, we are close to the threshold of quantum devices whose computational powers can exceed those of classical supercomputers. Here, we show that a quantum computer can be used to elucidate reaction mechanisms in complex chemical systems, using the open problem of biological nitrogen fixation in nitrogenase as an example. We discuss how quantum computers can augment classical computer simulations used to probe these reaction mechanisms, to significantly increase their accuracy and enable hitherto intractable simulations. Our resource estimates show that, even when taking into account the substantial overhead of quantum error correction, and the need to compile into discrete gate sets, the necessary computations can be performed in reasonable time on small quantum computers. Our results demonstrate that quantum computers will be able to tackle important problems in chemistry without requiring exorbitant resources.

Chemical reaction mechanisms are networks of molecular structures representing short- or long-lived intermediates connected by transition structures. The relative energies of all stable structures determine the relative thermodynamical stability. Differences of the energies of local minima and connecting transition structures determine the rates of interconversion, i.e., the chemical kinetics of the process. As they enter exponential expressions, very accurate energy differences are required for the reliable evaluation of the rate constants. At its core, the detailed understanding and prediction of complex reaction mechanisms then requires highly accurate electronic structure methods. However, the electron correlation problem remains, despite decades of progress (1), one of the most vexing problems in quantum chemistry. Although approximate approaches, such as density functional theory (DFT) (2), are very popular, their accuracy is often too low for quantitative predictions (see, e.g., refs. 3 and 4); this holds particularly true for molecules with many energetically close-lying orbitals. For such problems on classical computers, much less than a hundred strongly correlated electrons are already out of reach for systematically improvable ab initio methods that could achieve the required accuracy.

The apparent intractability of accurate simulations for such quantum systems led Richard Feynmann to propose quantum computers. The promise of exponential speedups for quantum simulation on quantum computers was first investigated by Lloyd (5) and Zalka (6) and was directly applied to quantum chemistry by Lidar, Aspuru-Guzik, and others (7–11). Quantum chemistry simulation has remained an active area within quantum algorithm development, with ever more sophisticated methods being used to reduce the costs of quantum chemistry simulation (12–20).

The promise of exponential speedups for the electronic structure problem has led many to suspect that quantum computers will one day revolutionize chemistry and materials science. However, a number of important questions remain. Not the least of these is the question of how exactly to use a quantum computer to solve an important problem in chemistry. The inability to point to a clear use case complete with resource and cost estimates is a major drawback; after all, even an exponential speedup may not lead to a useful algorithm if a typical, practical application requires an amount of time and memory that is beyond the reach of even a quantum computer.

Here, we demonstrate, for an important prototypical chemical system, how a quantum computer would be used, in practice, to address an open problem, and we estimate how large and how fast a quantum computer would have to be to perform such calculations within a reasonable amount of time. Our findings set a target for the type and size of quantum device that we would like to emerge from existing research and further gives confidence that quantum simulation will be able to provide answers to problems that are both scientifically and economically impactful.

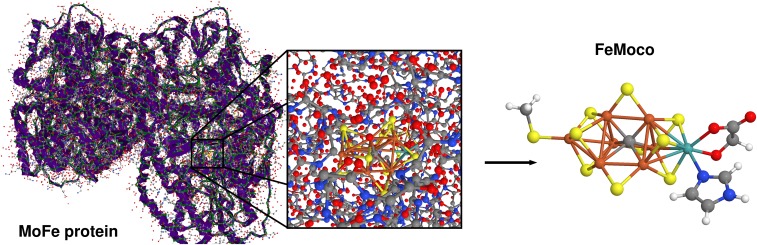

The chemical process that we consider in this work is that of biological nitrogen fixation by the enzyme nitrogenase (22). This enzyme accomplishes the remarkable transformation of dinitrogen into two ammonia molecules under ambient conditions. Whereas the industrial Haber–Bosch catalyst requires high temperature and pressure and is therefore energy-intensive, the active site of Mo-dependent nitrogenase, the iron molybdenum cofactor (FeMoco) (23, 24), can split the dinitrogen triple bond at room temperature and standard pressure. Mo-dependent nitrogenase consists of two subunits, the Fe protein, a homodimer, and the MoFe protein, an tetramer. Fig. 1 shows the MoFe protein of nitrogenase (Fig. 1, Left) and the FeMoco buried in this protein (Fig. 1, Middle). Despite the importance of this process for fertilizer production that makes nitrogen from air accessible to plants, the mechanism of nitrogen fixation at FeMoco is not known. Experiments have not yet been able to provide sufficient details on the chemical mechanism, and theoretical attempts are hampered by intrinsic methodological limitations of traditional quantum chemical methods.

Fig. 1.

(Left) X-ray crystal structure 4WES (21) of the nitrogenase MoFe protein from Clostridium pasteurianum taken from the protein database (the backbone is colored in green, and hydrogen atoms are not shown), (Middle) the close protein environment of the FeMoco, and (Right) the structural model of FeMoco considered in this work (C, gray; O, red; H, white; S, yellow; N, blue; Fe, brown; and Mo, cyan).

Quantum Chemical Methods for Mechanistic Studies

At the heart of any chemical process is its mechanism, the elucidation of which requires the identification of all relevant stable intermediates and transition states. In general, a multitude of charge and spin states need to be explicitly calculated in search of the relevant ones that make the whole chemical process viable. Such a mechanistic exploration can lead to thousands of elementary reaction steps (25) whose reaction energies must be reliably calculated. In the case of nitrogenase, numerous protonated intermediates of dinitrogen-coordinating FeMoco and subsequently reduced intermediates in different charge and spin states are feasible and must be assessed with respect to their relative energy. Especially, kinetic modeling poses tight limits on the accuracy of activation energies entering the argument of exponentials in rate expressions.

For nitrogenase, an electrostatic quantum mechanical/molecular mechanical (QM/MM) model (26) that captures the embedding of FeMoco into the protein pocket of nitrogenase can properly account for the protein environment. Accordingly, we consider a structural model for the active site of nitrogenase (Fig. 1, Right) carrying only models of the anchoring groups of the protein, which represents a suitable QM part in such calculations. To study this bare model is no limitation, as it does not at all affect our feasibility analysis (because electrostatic QM/MM embedding will not change the number of orbitals considered for the wave function construction). We carried out (full) molecular structure optimizations with DFT methods of this FeMoco model in different charge and spin states to avoid basing our analysis on a single electronic structure. Although our FeMoco model is taken from the resting state, binding of a small molecule such as dinitrogen, dihydrogen, diazene, or ammonia will not decisively change the complexity of its electronic structure.

The Born–Oppenheimer approximation assigns an electronic energy to every molecular structure. The accurate calculation of this energy is the pivotal challenge, here considered by quantum computing. Characteristic molecular structures are optimized to provide local minimum structures indicating stable intermediates and first-order saddle points representing transition structures. The electronic energy differences for elementary steps that connect two minima through a transition structure enter expressions for rate constants by virtue of Eyring’s absolute rate theory (ART). Although more information on the potential energy surface as well as dynamic and quantum effects may be taken into account, ART is accurate even for large molecules such as enzymes (27, 28). These rate constants then enter a kinetic description of all elementary steps that ultimately provide a complete picture of the chemical mechanism under consideration.

Exact Diagonalization Methods in Chemistry.

If the frontier orbital region around the Fermi level of a given molecular structure is dense, as is the case in -conjugated molecules or open-shell transition metal complexes (such as FeMoco), then so-called strong static electron correlation plays a decisive role already in the ground state. Static electron correlations are even more pronounced for electronically excited states relevant in photophysical and photochemical processes such as light harvesting for clean energy applications. Such situations require multiconfigurational methods of which the complete-active-space self-consistent-field (CASSCF) approach has been established as a well-defined model that also serves as the basis for more advanced approaches (29). CAS-type approaches require the selection of orbitals for the CAS, usually from those around the Fermi energy, which can be automatized (30–33). Although CAS-type methods well account for static electron correlation, the remaining dynamic correlation is decisive for quantitative results. A remaining major drawback of exact-diagonalization schemes therefore is to include the contribution of all neglected virtual orbitals.

CASSCF is traditionally implemented as an exact diagonalization method, which limits its applicability to 18 electrons in 18 (spatial) orbitals, because of the steep scaling of many-electron basis states with the number of electrons and orbitals (34). The polynomially scaling density matrix renormalization group (DMRG) algorithm (35) can push this limit to about 100 spatial orbitals; this, however, also comes at the cost of an iterative procedure whose convergence for strongly correlated molecules is, due to the matrix product state representation of the electronic wave function, neither easy to achieve nor guaranteed.

Ways Quantum Computers Will Help Solve These Problems.

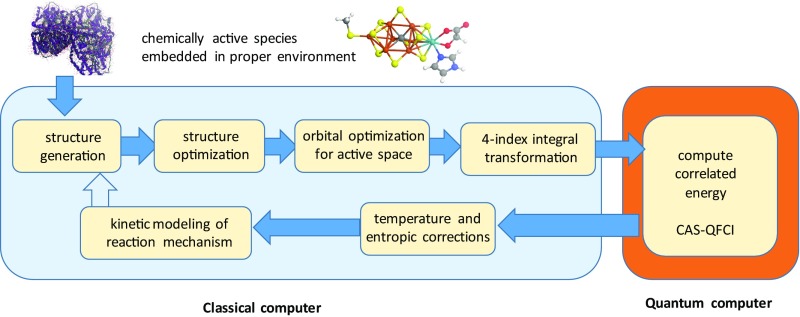

Molecular structure optimizations are commonly found with standard DFT approaches. DFT-optimized molecular structures are, in general, reliable, even if the corresponding energies are affected by large uncontrollable errors. The latter problem can be solved by a quantum computer that implements a multiconfigurational wave function model to access truly large active orbital spaces. The orbitals for this model do not necessarily need to be optimized, as natural orbitals can be taken from an unrestricted Hartree–Fock (36) or small-CAS CASSCF calculation. The missing dynamic correlation can then be implemented in a “perturb-then-diagonalize” fashion before the quantum computations start or in a “diagonalize-then-perturb” fashion, where the quantum computer is used to compute the higher-order reduced density matrices required. The former approach, i.e., built-in dynamic electron correlation, is considerably more advantageous, as no wave function-derived quantities need to be calculated. One option for this approach is, for example, to consider dynamic correlation through DFT that avoids any double counting effects by virtue of range separation, as has already been successfully studied for CASSCF and DMRG (37, 38). Fig. 2 presents a flowchart that describes the steps of a quantum computer-assisted chemical mechanism exploration. Moreover, the quantum computer results can be used for the validation and improvement of parametrized approaches such as DFT to improve on the latter for the massive prescreening of structures and energies.

Fig. 2.

Generic flowchart of a computational reaction mechanism elucidation with a quantum computer part that delivers a quantum full configuration interaction (QFCI) energy in a (restricted) complete active orbital space (CAS). Once a structural model of the active chemical species (here FeMoco, top right) embedded in a suitable environment (the metalloprotein, top left) is chosen, structures of potential intermediates can be set up and optimized. Molecular orbitals are then optimized for a suitably chosen Fock operator. A four-index transformation from the atomic orbital to the molecular basis produces all integrals required for the second-quantized Hamiltonian. Once the quantum computer produces the (ground state) energy of this Hamiltonian, this energy can be supplemented by corrections that consider nuclear motion effects to yield enthalpic and entropic quantities at a given temperature according to standard protocols (e.g., from DFT calculations). The temperature-corrected energy differences between stable intermediates and transition structures then enter rate expressions for kinetic modeling. For complex chemical mechanisms, this modeling might point to the exploration of additional structures.

Quantum Simulation of Quantum Chemical Systems

Ground state energies on a quantum computer can be obtained by quantum phase estimation (QPE). If we take the time evolution of an eigenstate to be , then QPE learns the phase in a manner analogous to a Mach–Zehnder interferometer. Measuring the phase starting from an approximate ground state collapses the wave function into an exact eigenstate and gives its energy. Time evolution is implemented using the Trotter–Suzuki approach (SI Appendix), and efficient methods exist to implement each of the terms in a second quantized Hamiltonian (11). Although algorithms are known that can achieve better scaling than low-order Trotter–Suzuki methods for some problems (39–44), they are more challenging to lay out, as circuits and preliminary estimates suggest that they perform worse at this problem size. For these reasons, we focus on low-order Trotter–Suzuki methods here and leave the task of fully costing out these alternative methods for future work.

To achieve reliable results, a fault-tolerant implementation of the quantum algorithm is crucial. Encoding a single logical qubit in a number of physical qubits with a quantum error-correcting code, such as the surface code (45), protects the logical qubit against decoherence and other experimental imperfections.

Quantum error correction cannot directly protect any arbitrary quantum operation, but it can protect a discrete set of gates, from which any continuous quantum operation can be approximated to within arbitrarily small error (46). Approximation takes two steps. First, the exponentials in the time evolution are decomposed into single-qubit rotations and so-called Clifford gates. In the surface code, which we consider here, Clifford gates can be implemented fault tolerantly. The single-qubit rotations, however, require approximation by a discrete set of gates consisting of Clifford operations and at least one non-Clifford operation, usually taken to be the T gate, a rotation by about the axis. Each T gate requires a procedure called magic state distillation, which consumes a host of noisy quantum states to output a single accurate magic state. The magic state is then used to teleport a T gate into the computation (47). The space and time overheads of state distillation render it the most costly aspect of quantum error correction, leading to a large overhead that is not taken into account in most previous cost estimates for quantum chemistry.

Resource Estimates.

We now estimate the costs of such simulations, focusing on two prototypical structures of FeMoco that are an example of the complexity of those that naturally would arise when probing the potential energy landscape of the complex. We first estimate the run time of the computation assuming a quantum computer can perform a logical T gate every ns or ns; Clifford circuits require negligible time and that a good trial state for the ground state is available. The cost of preparing trial states is discussed in SI Appendix. We then determine the cost of performing this simulation fault-tolerantly using the surface code, such that each physical gate takes ns or ns, including any time required by the decoder. We will predominantly look at two cases. In the first, we consider a quantum computer with error rates and -ns gates as a realistic estimate of where superconducting technology may be for near-term devices, and error rates and -ns gates as an aspirational target for future generations of quantum computers.

We aim to compute the energies with a total error of, at most, millihartree (mHa) adding up all sources of discretization and statistical error. We also consider errors of mHa which is comparable to the accuracy range of standard state-of-the-art quantum chemical methods for simple (mononuclear) transition metal complexes.

We consider three concrete implementations of the quantum algorithm and show the required gate counts in Table 1. In the “Serial” approach, the rotations are constrained to occur serially. In the “Nesting” approach (18), Hamiltonian terms that affect disjoint sets of spin orbitals are executed in parallel. In a third approach, programmable ancilla rotations (PAR), rotations are precomputed in parallel factories and then teleported into the circuit as needed (12). The overall cost of each approach is found by decomposing the rotations into Clifford and T gates using ref. 48 for the serial case and ref. 49 in the other cases. If all gates are executed in series, then we estimate that the simulation will complete in under a year and use a small number of logical qubits. PAR can reduce the time required to several days at the price of requiring nearly times as many logical qubits. Nesting gives a reasonable trade-off between the two.

Table 1.

Simulation time estimates

| Structure | T gates | Cl. gates | (10 ns) | (100 ns) | Qubits |

| Quantitatively accurate simulation (0.1 mHa) | |||||

| Structure 1 | |||||

| Serial | d | y | 111 | ||

| Nesting | d | mo | 135 | ||

| PAR | h | mo | 1,982 | ||

| Structure 2 | |||||

| Serial | d | y | 117 | ||

| Nesting | d | mo | 142 | ||

| PAR | h | mo | 2,024 | ||

| Qualitatively accurate simulation (1 mHa) | |||||

| Structure 1 | |||||

| Serial | d | mo | 111 | ||

| Nesting | d | d | 135 | ||

| PAR | h | d | 1,982 | ||

| Structure 2 | |||||

| Serial | d | mo | 117 | ||

| Nesting | d | d | 142 | ||

| PAR | h | d | 2,024 | ||

Listed are the number of Clifford and T-gate operations, the estimate of the run time (Δt), and the number of logical qubits required to obtain energies within 0.1 mHa or 1 mHa for two different structures of FeMoco on a quantum computer. Structure 1 is for spin state S = 0 and charge +3 elementary charges with 54 electrons in 54 spatial orbitals. Structure 2 is for spin state S = 1/2 and charge 0 with 65 electrons in 57 spatial orbitals (see SI Appendix for further details). These run times and gate counts are likely to be pessimistic.

These estimates can be improved, if necessary, using the techniques we provide in SI Appendix. Specifically, we provide simulation circuits that reduce the depth of the quantum simulation by a factor of and also give near-optimal phase estimation algorithms that use a cluster of quantum computers to estimate the phase. These methods not only can allow our algorithms to be run in much less time, if necessary, but also may be of independent interest to researchers.

Resource Requirements with Quantum Error Correction.

We next add the overheads required to perform the simulation fault-tolerantly and summarize the costs for structure 1 in Table 2. The underlying resource calculations for the fault-tolerant overheads follow ref. 45. These costs depend on the physical error rates in the hardware, and we consider three cases corresponding to (i) a near-term error rate of , (ii) error rates of that may one day be achievable in superconducting qubits or ion traps, and (iii) , which could be achievable for topological quantum computers (50).

Table 2.

Fault tolerance overheads

| Requirements | Serial rotations | PAR rotations | Nested rotations | ||||||

| Error rate | |||||||||

| Required code distance | 35,17 | 9 | 5 | 37,19 | 9,5 | 5 | 37,17 | 9 | 5 |

| Quantum processor | |||||||||

| Logical qubits | 111 | 111 | 111 | 110 | 110 | 110 | 109 | 109 | 109 |

| Physical qubits per logical qubit | 15313 | 1013 | 313 | 17113 | 1013 | 313 | 17113 | 1013 | 313 |

| Total physical qubits for processor | |||||||||

| Rotation factories | |||||||||

| Number | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1872 | 1872 | 1872 | 26 | 26 | 26 |

| Physical qubits per factory | – | – | – | 17113 | 1013 | 313 | 17113 | 1013 | 313 |

| Total physical qubits for rotations | – | – | – | ||||||

| T factories | |||||||||

| Number | 202 | 68 | 38 | 166462 | 41110 | 29659 | 5845 | 1842 | 1029 |

| Physical qubits per factory | |||||||||

| Total physical qubits for T factories | |||||||||

| Total physical qubits | |||||||||

This table gives the resource requirements, including error correction for simulations of nitrogenase’s FeMoco in structure 1 within the times quoted in Table 1 using physical gates operating at 100 MHz and taking the error target to be 0.1 mHa.

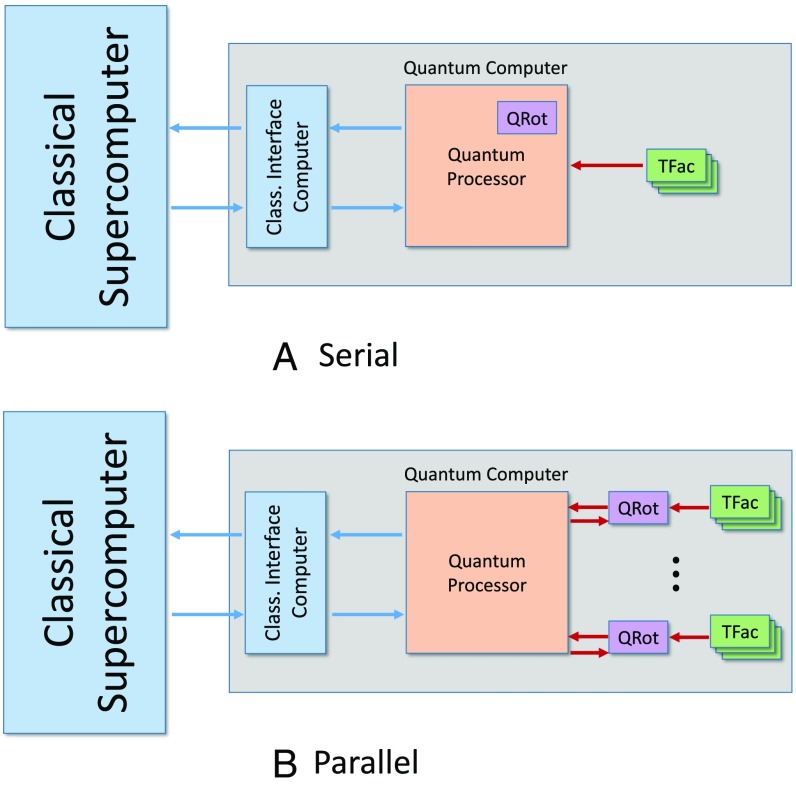

We consider a high-level architecture for a quantum computer, sketched in Fig. 3, consisting of a classical supercomputer interfacing with a quantum computer that consists of a main quantum processor and dedicated separate T factories and rotation factories to produce T gates and to synthesize rotations, respectively. Only the main quantum processor is intended for general purpose computing, whereas the other factories are intended for special purposes.

Fig. 3.

Hardware architectures for quantum computers. We show the architecture of a hybrid classical/quantum computer for quantum chemistry-type calculations. Shown are (A) a serial architecture using a single rotation factory and (B) a parallel architecture with multiple rotation factories. The quantum computer acts as an accelerator to the classical supercomputer. It consists of a classical control front end, a main quantum processor, and a number of auxiliary processing units. The devices labeled QRot build single-qubit rotations using rotations created in the T-gate factories labeled Tfac. Red arrows denote quantum communication, and blue arrows represent classical communication.

The subdivisions in our architecture need not be physical. Indeed, we implicitly assume that they are logical in our analysis, but thinking about the device from this perspective reveals that quantum computer architectures can be tailored to quantum simulation. In particular, such hardware can exploit the fact that such simulations only require magic states when the algorithm is performing single-qubit rotations. Optimizing against a fixed architecture designed for quantum simulation can furthermore reduce the bandwidth needed to control the device, make compilation easier, and simplify communication within the device.

We first observe in Table 2 that the number of logical qubits in the main quantum processor is only of the order of a hundred, which translates into tens of thousands to millions of physical qubits, which is challenging but not out of reach. Most of the qubits are used in the T factories, which each need fewer physical qubits than the main quantum processor. The number of T factories needed to perform the serial calculation is small, with such factories required, in this case, for an error rate of , and fewer for better qubits. After factoring in the number of qubits needed per T factory, we arrive at the conclusion that only to physical qubits are needed for the and error rates.

If we parallelize with the PAR approach, then these costs are more daunting. The number of T factories required increases by a factor of roughly . If we use the nesting approach, then the costs are an order of magnitude greater than the serial case in the number of qubits, with a comparable reduction in run times.

To summarize, our estimates suggest that a quantum computer that operates with -MHz gates with error rates could be simulated within a reasonable time using either nesting or PAR, but the number of physical qubits required will likely be prohibitive. On the other hand, the requirements are much more modest with the aspirational target of -MHz gates with error rates; a large but manageable number of physical qubits suffices, and the need to parallelize is nowhere near as dire. Therefore, barring further developments in quantum simulation algorithms or quantum error correction, we should aim to see quantum computers that meet our aspirational goal emerge from quantum computing programs. New simulation methods such as in refs. 41–44 may one day provide decisive advantages for problems like FeMoco, but more work is needed to provide complete cost estimates for them and, in turn, a fair comparison between the costs that they incur relative to Trotter–Suzuki methods for problems of this size. Finally, these low gate errors could one day be provided by topological quantum computers (50), which underscores the value in developing such hardware.

Discussion

Although, at present, a quantitative understanding of chemical processes involving complex open-shell species such as FeMoco in biological nitrogen fixation remains beyond the capability of classical computer simulations, our work shows that quantum computers used as accelerators to classical computers could be employed to elucidate this mechanism using a manageable amount of memory and time. The quantum computer is used here to obtain, validate, or correct the energies of intermediates and transition states and thus gives accurate activation energies for various transitions. The required space and time resources for simulating FeMoco using the 54-orbital basis and nesting are comparable to that of Shor’s factoring algorithm for -bit numbers (45).

Parallelizing the quantum computation of the energy landscape will be crucial to providing answers within a timeframe of several days instead of several years. Bounding the number of repetitions of phase estimation needed to prepare the ground state from an initial ansatz remains an open problem (see SI Appendix), and parallelism may often be needed to allow us to tolerate low success probability. Quantum computers therefore must be designed with a scalable architecture in mind and also built with the realization that constructing a single quantum computer is insufficient to solve such tasks. Instead, we should aim to have quantum computers that can be built en masse, because clusters of quantum computers will be needed to scan over the many structures that need to be examined to identify and estimate all important reaction rates (25).

Finally, chemical reactions that involve strongly correlated species that are hard to describe by traditional multiconfiguration approaches are not just limited to nitrogen fixation: They are ubiquitous. They range from C–H bond activating catalysts; to those for hydrogen and oxygen production, carbon dioxide fixation, and transformation; to industrially useful compounds; to photochemical processes. Given the economic and societal impact of chemical processes ranging from fertilizer production to polymerization catalysis and clean energy processes, the importance of a versatile, reliable, and fast quantum chemical approach powered by quantum computing can hardly be overemphasized.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. D.P.D. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1619152114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Dykstra C, Frenking G, Kim KS, Scuseria GE. Theory and Applications of Computational Chemistry: The First Forty Years. Elsevier; Amsterdam: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cramer CJ, Truhlar DG. Density functional theory for transition metals and transition metal chemistry. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2009;11:10757–10816. doi: 10.1039/b907148b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jiang W, DeYonker NJ, Determan JJ, Wilson AK. Toward accurate theoretical thermochemistry of first row transition metal complexes. J Phys Chem A. 2012;116:870–885. doi: 10.1021/jp205710e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weymuth T, Couzijn EPA, Chen P, Reiher M. New benchmark set of transition-metal coordination reactions for the assessment of density functionals. J Chem Theor Comput. 2014;10:3092–3103. doi: 10.1021/ct500248h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lloyd S. Universal quantum simulators. Science. 1996;273:1073–1078. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5278.1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zalka C. Simulating quantum systems on a quantum computer. Proc R Soc A Math Phys Eng Sci. 1998;454:313–322. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lidar DA, Wang H. Calculating the thermal rate constant with exponential speedup on a quantum computer. Phys Rev E. 1999;59:2429–2438. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang H, Kais S, Aspuru-Guzik A, Hoffmann MR. Quantum algorithm for obtaining the energy spectrum of molecular systems. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2008;10:5388–5393. doi: 10.1039/b804804e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lanyon BP, et al. Towards quantum chemistry on a quantum computer. Nat Chem. 2010;2:106–111. doi: 10.1038/nchem.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kassal I, Whitfield JD, Perdomo-Ortiz A, Yung MH, Aspuru-Guzik A. Simulating chemistry using quantum computers. Annu Rev Phys Chem. 2011;62:185–207. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physchem-032210-103512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Whitfield JD, Biamonte J, Aspuru-Guzik A. Simulation of electronic structure Hamiltonians using quantum computers. Mol Phys. 2011;109:735–750. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones NC, et al. Faster quantum chemistry simulation on fault-tolerant quantum computers. New J Phys. 2012;14:115023. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peruzzo A, et al. A variational eigenvalue solver on a photonic quantum processor. Nat Commun. 2014;5 doi: 10.1038/ncomms5213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wecker D, Bauer B, Clark BK, Hastings MB, Troyer M. Gate-count estimates for performing quantum chemistry on small quantum computers. Phys Rev A. 2014;90:022305. [Google Scholar]

- 15.McClean JR, Babbush R, Love PJ, Aspuru-Guzik A. Exploiting locality in quantum computation for quantum chemistry. J Phys Chem Lett. 2014;5:4368–4380. doi: 10.1021/jz501649m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hastings MB, Wecker D, Bauer B, Troyer M. Improving quantum algorithms for quantum chemistry. Quan Inf Comput. 2015;15:1–21. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Poulin D, et al. The Trotter step size required for accurate quantum simulation of quantum chemistry. Quan Inf Comput. 2015;15:361–384. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wecker D, Hastings MB, Troyer M. Progress towards practical quantum variational algorithms. Phys Rev A. 2015;92:042303. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Babbush R, McClean J, Wecker D, Aspuru-Guzik A, Wiebe N. Chemical basis of Trotter–Suzuki errors in quantum chemistry simulation. Phys Rev A. 2015;91:022311. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bauer B, Wecker D, Millis AJ, Hastings MB, Troyer M. 2015. Hybrid quantum-classical approach to correlated materials. arXiv:1510.03859.

- 21.Zhang LM, Morrison CN, Kaiser JT, Rees DC. Nitrogenase MoFe protein from Clostridium pasteurianum at 1.08 Å resolution: Comparison with the Azotobacter vinelandii MoFe protein. Acta Crystallogr. 2015;D71:274–282. doi: 10.1107/S1399004714025243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoffman BM, Lukoyanov D, Yang ZY, Dean DR, Seefeldt LC. Mechanism of nitrogen fixation by nitrogenase: The next stage. Chem Rev. 2014;114:4041–4062. doi: 10.1021/cr400641x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spatzal T, et al. Evidence for interstitial carbon in nitrogenase FeMo cofactor. Science. 2011;334:940. doi: 10.1126/science.1214025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lancaster KM, et al. X-ray emission spectroscopy evidences a central carbon in the nitrogenase iron-molybdenum cofactor. Science. 2011;334:974–977. doi: 10.1126/science.1206445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bergeler M, Simm GN, Proppe J, Reiher M. Heuristics-guided exploration of reaction mechanisms. J Chem Theor Comput. 2015;11:5712–5722. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.5b00866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Warshel A. Multiscale modeling of biological functions: From enzymes to molecular machines (Nobel Lecture) Angew Chem Int Ed. 2014;53:10020–10031. doi: 10.1002/anie.201403689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Olsson MH, Mavri J, Warshel A. Transition state theory can be used in studies of enzyme catalysis: Lessons from simulations of tunnelling and dynamical effects in lipoxygenase and other systems. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B. 2006;361:1417–1432. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2006.1880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Glowacki DR, Harvey JN, Mulholland AJ. Taking Ockham’s razor to enzyme dynamics and catalysis. Nat Chem. 2012;4:169–176. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Helgaker T, Jørgensen P, Olsen J. Molecular Electronic-Structure Theory. John Wiley; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pulay P, Hamilton TP. UHF natural orbitals for defining and starting MC-SCF calculations. J Chem Phys. 1988;88:4926–4933. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stein CJ, Reiher M. Automated selection of active orbital spaces. J Chem Theor Comput. 2016;12:1760–1771. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.6b00156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stein CJ, Reiher M. Automated identification of relevant frontier orbitals for chemical compounds and processes. Chimia. 2017;71:170–176. doi: 10.2533/chimia.2017.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stein CJ, Reiher M. Measuring multi-configurational character by orbital entanglement. Mol Phys. February 22, 2017 doi: 10.1080/00268976.2017.1288934. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aquilante F, et al. Molcas 8: New capabilities for multiconfigurational quantum chemical calculations across the periodic table. J Comput Chem. 2016;37:506–541. doi: 10.1002/jcc.24221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.White SR. Density matrix formulation for quantum renormalization groups. Phys Rev Lett. 1992;69:2863–2866. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.69.2863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bofill JM, Pulay P. The unrestricted natural orbital-complete active space (UNO-CAS) method: An inexpensive alternative to the complete active space-self-consistent-field (CAS-SCF) method. J Chem Phys. 1989;90:3637–3646. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fromager E, Toulouse J, Jensen HJA. On the universality of the long-/short-range separation in multiconfigurational density-functional theory. J Chem Phys. 2007;126:074111. doi: 10.1063/1.2566459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hedegård ED, Knecht S, Kielberg JS, Jensen HJA, Reiher M. Density matrix renormalization group with efficient dynamical electron correlation through range separation. J Chem Phys. 2015;142:224108. doi: 10.1063/1.4922295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Berry DW, Ahokas G, Cleve R, Sanders BC. Efficient quantum algorithms for simulating sparse Hamiltonians. Commun Math Phys. 2007;270:359–371. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Childs AM, Wiebe N. Hamiltonian simulation using linear combinations of unitary operations. Quan Inf Comput. 2012;12:901–924. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Berry DW, Childs AM, Cleve R, Kothari R, Somma RD. Simulating Hamiltonian dynamics with a truncated Taylor series. Phys Rev Lett. 2015;114:090502. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.114.090502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Babbush R, et al. 2015. Exponentially more precise quantum simulation of fermions ii: Quantum chemistry in the CI matrix representation. arXiv:1506.01029.

- 43.Babbush R, et al. Exponentially more precise quantum simulation of fermions in second quantization. New J Phys. 2016;18:033032. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kivlichan ID, Wiebe N, Babbush R, Aspuru-Guzik A. 2016. Bounding the costs of quantum simulation of many-body physics in real space. arXiv:1608.05696. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Fowler AG, Mariantoni M, Martinis JM, Cleland AN. Surface codes: Towards practical large-scale quantum computation. Phys Rev A. 2012;86:032324. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nielsen MA, Chuang IL. Quantum Computation and Quantum Information. Cambridge Univ Press; New York: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bravyi S, Kitaev A. Universal quantum computation with ideal Clifford gates and noisy ancillas. Phys Rev A. 2005;71:022316. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bocharov A, Roetteler M, Svore KM. Efficient synthesis of probabilistic quantum circuits with fallback. Phys Rev A. 2015;91:052317. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.114.080502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Selinger P. Efficient Clifford+ T approximation of single-qubit operators. Quan Inf Comput. 2015;15:159–180. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sarma SD, Freedman M, Nayak C. 2015. Majorana zero modes and topological quantum computation. arXiv:1501.02813.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.