Abstract

Scaffold-free systems have emerged as viable approaches for engineering load-bearing tissues. However, the tensile properties of engineered tissues have remained far below the values for native tissue. Here, by using self-assembled articular cartilage as a model to examine the effects of intermittent and continuous tension stimulation on tissue formation, we show that the application of tension alone, or in combination with matrix remodelling and synthesis agents, leads to neocartilage with tensile properties approaching those of native tissue. Implantation of tension-stimulated tissues results in neotissues that are morphologically reminiscent of native cartilage. We also show that tension stimulation can be translated to a human cell source to generate anisotropic human neocartilage with enhanced tensile properties. Tension stimulation, which results in nearly 6-fold improvements in tensile properties over unstimulated controls, may allow the engineering of mechanically robust biological replacements of native tissue.

Introduction

During embryonic development, tight regulation of chemical gradients drives the formation of specialized tissues. Similar to chemical factors, biomechanical stimuli are critical during embryogenesis. Beyond development, biomechanics is also essential for maturation, maintenance, and pathophysiological processes. To study the role of biomechanical forces on tissue formation from the tissue level to the cellular level, we used scaffold-free articular cartilage, formed using a self-assembling process, as a model. In articular cartilage, it is known that biomechanical forces similarly drive development, maturation, maintenance, and pathophysiology1. Moreover, since articular cartilage is considered to function primarily in compression and shear, application of these stimuli dominates the cartilage regeneration field. Tensile forces also play a role in cartilage homeostasis, but the use of tension stimulation is largely understudied.

In addition to exploring biomechanics in a model system where the use of tension is understudied, we selected cartilage tissue formation because of the clinical impact it can have for those with osteoarthritis. Worldwide, approximately 240 million cases of osteoarthritis were reported in 2013, a 72% increase from 19902. With the aging population and increasingly effective methods of diagnosis, the prevalence of osteoarthritis will continue to increase. The degeneration of articular cartilage—the smooth tissue that lines the articulating surfaces within a joint—can be a result of acute trauma or long-term overuse. Healthy articular cartilage functions as a load-bearing tissue, self-lubricated to provide a frictionless surface for joint movement. When cartilage is damaged, the joint compartments no longer translate smoothly, leading to increased tissue wear and, ultimately, degeneration.

Though the difficulty of repair and regeneration of articular cartilage has been recognized as early as the 4th century BCE, when Aristotle stated that “Cartilage…when once cut off, [does not]' grow again”3, only in the last five decades have tissue regeneration strategies specifically sought to replace damaged cartilage by creating implants in vitro4,5. These implants must be able to withstand the mechanically strenuous joint environment; as such, the aim is to generate tissues with properties matching those of native cartilage6,7. Chemical stimulation methods have been widely employed, as have mechanical stimulation regimens in the form of compression, hydrostatic pressure, or shear8-10. In contrast, tension stimulation has not been examined commonly. A few representative studies include tension stimulation of chondrocytes in monolayer11, of chondrocytes or fibroblasts seeded in scaffold12,13, and of chondrocytes seeded in fibrin gel14,15. However, no studies have identified an efficacious tensile loading regimen for improving tensile properties of tissue-engineered cartilage; in particular, tension has not been examined at all for scaffold-free cartilage formation. While the compressive properties of native articular cartilage have been attained in engineered cartilage16,17, achieving tensile properties akin to native tissue remains a major challenge. Motivated by the lack of studies examining tension as a potential stimulus in scaffold-free systems, we first sought to examine the effects of tension stimulation on tissue formation. To do so, we used self-assembling neocartilage as a model system of tissue formation in the absence of exogenous scaffolds. This system allows tensile forces to be directly applied to matrix and cells, without stress-shielding from scaffolds. Furthermore, to address the disparity between engineered and native tissue tensile properties, an additional goal of this study was to create neocartilage with tensile modulus and strength mimicking native articular cartilage via the application of Intermittent or Continuous Tension Stimulation (InTenS and CoTenS, respectively).

Toward achieving these objectives, we executed a series of studies involving the use of tension stimulation alone or in combination with matrix remodeling and synthesis agents known to enhance tissue formation and organization. Previous studies have shown that bioactive factors transforming growth factor-β1 (TGFβ1), chondroitinase-ABC (CABC), and LOXL2 (lysyl oxidase-like protein 2 with copper sulfate and hydroxylysine) can increase the tensile properties of scaffold-free neocartilage18-20. Here, we hypothesized that tension stimulation would improve neocartilage tensile properties to native tissue-like levels—beyond what is achieved by bioactive factors—as well as produce an anisotropic extracellular matrix (ECM) to mimic native cartilage structure. We also explored cellular mechanisms by which tension stimulation may affect the neotissue, identifying potential pathways via which mechanotransduction occurs to initiate matrix remodeling. Since the ion channel transient receptor potential vanilloid-4 (TRPV4) channel has been shown to modulate cellular response to compressive mechanical loading21, it was also hypothesized that TRPV4 channel function is responsible for cellular response to InTenS. The CoTenS regimen was developed to further build on the effects seen with InTenS, aiming to fully explore the role that tension as a stimulus may play in the development of neocartilage. To determine the stability of the enhanced properties when subject to the in vivo milieu, we implanted these constructs in a subcutaneous environment. Finally, to highlight the clinical potential of these tensile and bioactive regimens, we applied these regimens to self-assembled, human neocartilage.

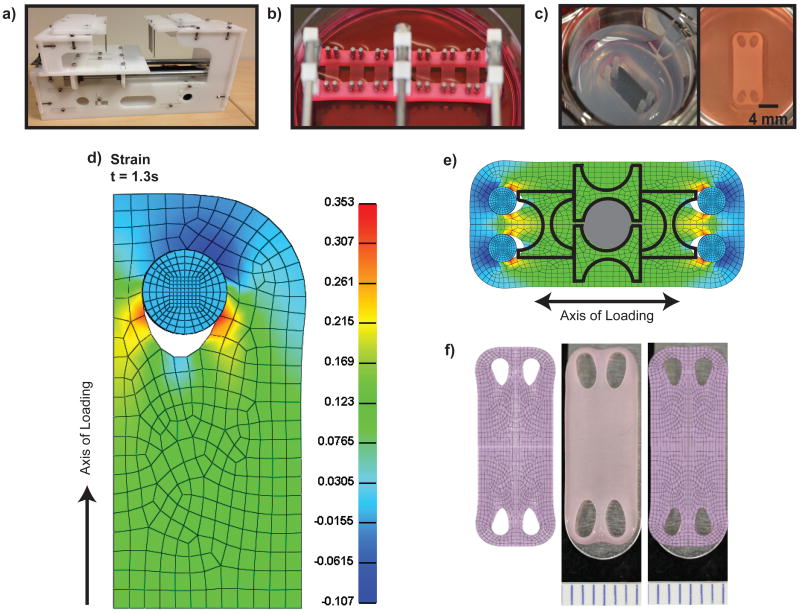

Design and validation of tension stimulation devices

We report the design and fabrication of tensile loading devices capable of InTenS and CoTenS (Figures 1a and 1b). Custom well-makers were fabricated to create rectangular neocartilage constructs, generated using the self-assembling process22, with a surface area of 80mm2 (Figure 1c). To predict the strain distribution in the neocartilage during tension stimulation, finite element modeling using the biphasic mixture theory was used. The model predicted uniform strain distribution through the center portion of neocartilage (Figure 1d). For InTenS, 12-15% strain was applied each day for 1 hr for 5 days. For CoTenS, a continuous strain of 12-15% strain was applied initially, followed by an additional 4-6% strain per day for 5 days. The highest strains were predicted in regions around the loading posts (i.e., openings in the neocartilage), reaching approximately 18%. Despite these areas of higher strain, mechanical and biochemical samples were easily portioned from the center region experiencing uniform strain (Figure 1e). Indeed, a topographical analysis across neocartilage samples demonstrated uniform tensile properties, with InTenS-stimulated neocartilage exhibiting enhanced tensile properties as compared to untreated tissues (Supplemental Figure 1a and 1b). It was demonstrated that just 2 days of InTenS was sufficient to induce significant increases in tensile properties (Supplemental Figure 1e). Finally, the model was validated by confirming that the predicted deformation matched the actual deformation of neocartilage after tension stimulation (Figure 1f). We, thus, built and employed devices that could successfully apply tension stimulation to neocartilage.

Figure 1. Large construct generation and uniform strain validation.

Modeling of stress and strain distribution during tension stimulation enabled the rational design of constructs displaying uniformity through the central portion. An agarose mold was created to generate rectangular self-assembled constructs (a). A custom tensile loading device was created for Intermittent Tension Stimulation (InTenS) (b). A custom tensile loading device was also designed and fabricated for Continuous Tension Stimulation (CoTenS) of neocartilage (c). Tension stimulation was applied along the long axis. Modeling of stress and strain distribution during tension stimulation predicts uniform distribution through the center of the neocartilage using a biphasic model (d). From the finite element (FE) model, uniform areas of strain were selected to portion compressive samples (hatched circle) and dumbbell-shaped parallel and perpendicular samples for tensile testing (outline) (e). The FE model was validated by overlaying the model with the actual deformed neocartilage (f).

Neocartilage engineering with tension stimulation

Regimens have been established for the application of growth factors, matrix remodeling enzymes, and matrix synthesis agents to enhance the material properties of neocartilage; these regimens of soluble stimuli are amenable to the addition of mechanical stimuli such as InTenS and CoTenS. The soluble stimuli, alone or in combination, can enhance the tensile properties of scaffold-free and scaffold-based neocartilage. TGFβ1 has been shown to enhance collagen production18,23,24. CABC, a catabolic enzyme that cleaves glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), removes excess GAGs within developing neocartilage and helps to reorganize the collagen matrix25. In this study, we showed that, once the collagen matrix is free of hydrophilic GAGs, the neocartilage is most responsive to tension stimulation, which also serves to align the collagen fibers. Finally, LOXL2 increases neocartilage tensile properties through crosslinking of nearby collagen molecules20. This study explored the use of tension alone and in combination with bioactive agents TGFβ1, CABC, and LOXL2 for engineering neocartilage. The various combinations of these agents were applied with InTenS. With CoTenS, an optimized bioactive regimen, or OBR, combining all three of these stimuli (TGFβ1, CABC, and LOXL2), was used (see Methods).

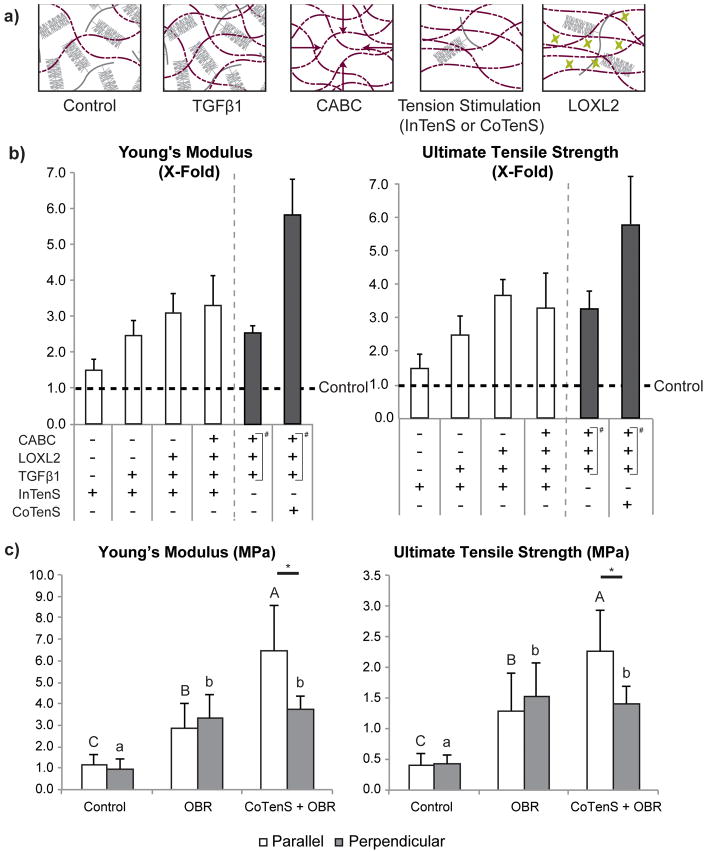

Tension stimulation had a significant effect on neocartilage formation. Tension influenced matrix synthesis and remodeling to increase matrix density and organization (Figure 2a), resulting in functional enhancements in the tensile properties (Figure 2b). Specifically, we demonstrated that InTenS alone could enhance the tensile properties up to 1.3-times those of untreated neocartilage, as measured in dumbbell-shaped specimens cut out from the neocartilage constructs (Figure 1e). The effects of tension stimulation were impressive when combined with bioactive factors, increasing tensile modulus and strength. The individual contribution of each of these stimuli to improving neocartilage material properties was also examined. InTenS, in combination with TGFβ1, elicited tensile Young's modulus and ultimate tensile strength (UTS) 2.4- and 2.7-times those of untreated controls, respectively (Figure 2b, and Supplemental Table 1). InTenS, in combination with TGFβ1, LOXL2, and CABC (or InTenS + TGFβ1/LOXL2/CABC), increased both the tensile modulus and UTS to 3.9-times untreated control values (Figure 2b). The Young's modulus reached 8.4±0.9MPa with InTenS + TGFβ1/LOXL2/CABC, in the range of reported values for native tissues6,7 (Supplemental Table 1), and is reflective of the developmental stage of the cell source (i.e., juvenile bovine cartilage)26. These values are the highest achieved for this scaffold-free, cell-based neocartilage system using primary cells, which previously reached values up to 2.3MPa for tensile modulus20. To achieve greater benefits from tension stimulation, the magnitude and duration of tension stimulation in InTenS were extended in CoTenS. Indeed, additional gains in material properties were observed. Overall, we discovered that while the contributions from bioactive factors were significant, tension stimulation was critical to bring the neocartilage material properties to native tissue-like levels, as CoTenS + OBR treatment increased tensile modulus 2.3-times that of OBR alone. Overall, tension stimulation resulted in neocartilage with tensile properties 5.8-times of untreated controls (Figure 2b). Therefore, tension as a stimulus can generate significant increases in scaffold-free neocartilage properties.

Figure 2. Tissue engineering of neocartilage with enhanced tensile properties.

In combination with tension stimulation, transforming growth factor β1 (TGFβ1), chondroitinase-ABC (CABC), and lysyl oxidase-like protein 2 (LOXL2) were applied to achieve neocartilage with tensile properties that are on par with native tissue. The sequential application of these agents alters the extracellular matrix (a): TGFβ1 enhances collagen production; CABC temporarily causes loss of glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), allowing collagen fibers to be in closer proximity; tension stimulation aligns the collagen fiber network that is unrestricted by bulky GAGs; and LOXL2 crosslinks the aligned collagen matrix. A series of experiments investigated the step-wise addition of these agents to InTenS (b, white bars) and found increases in both Young's modulus and ultimate tensile strength (UTS). To quantitatively compare the data across these multiple experiments, Young's modulus and UTS values of treated groups were normalized to those of untreated control in each experiment. Fold-changes with respect to untreated control (dotted line) are presented. The absolute tensile properties are presented in Supplemental Table 1A and 1B. The combination of InTenS, TGFβ1, CABC, and LOXL2, achieved a Young's modulus 3.3-times control values. CoTenS elicited further dramatic increases in Young's modulus and UTS—both 5.8-times control values; these increases were found to be due to CoTenS. This is because the optimized bioactive regimen (OBR), consisting of TGFβ1, CABC, and LOXL2 (denoted in panel b by #), reached a Young's modulus and UTS only 2.5- and 3.3-times control values, respectively (b, dark bars). Moreover, CoTenS + OBR elicited anisotropy in stimulated neocartilage, with the parallel direction stiffer and stronger than the perpendicular direction (c). Neither the OBR regimen nor the no-treatment group was able to induce anisotropy. Two one-way ANOVAs, followed by a Tukey's post hoc test, were performed to statistically assess the results. Groups not connected by the same letter are statistically significant. Student's t-test was performed to compare tensile properties of parallel and perpendicular directions, *p<0.05. Data are represented as mean±SD.

Concurrent with the increases in tensile values, the compressive properties of treated neocartilages also approached native tissue values. Interestingly, LOXL2 application in the presence of TGFβ1 and InTenS resulted in a significant decrease in compressive stiffness and shear modulus compared to TGFβ1 and InTenS; this reduction was not previously seen with LOXL2 use alone20 (Supplemental Table 1). LOX family members are known to possess growth factor binding domains and are able to modulate TGFβ1 activity via direct inhibition, processing alteration, and enzyme activation27. The simultaneous use of TGFβ1 and LOXL2 in this study may therefore result in their undesirable interaction. Further examination of timing regimens of TGFβ1 and LOXL2 may optimize their respective effects on neocartilage properties. Favorably, despite a decrease in compressive stiffness with InTenS + TGFβ1/LOXL2 treatment compared to InTenS + TGFβ1, the InTenS + TGFβ1/LOXL2 treatment was not significantly different than untreated neocartilage. Similarly, InTenS and bioactive treatment yielded neocartilage with comparable compressive modulus and shear modulus as neocartilage treated with bioactive agents alone (Supplemental Table 2). Moreover, use of CoTenS abrogates the decreases in compressive properties possibly induced by LOXL2, increasing the compressive stiffness to 199±33kPa from 148±22kPa with OBR alone. Overall, tension stimulation does not sacrifice other properties in favor of enhancing tensile values (Supplemental Table 1a).

In our study, we successfully engineered fully biologic tissues in the absence of exogenous scaffolds. In other tissue engineering studies using scaffold-based systems where mechanical properties were reported, native tissue-like properties can be achieved. However, it should be noted that a significant portion of those properties can be derived from the scaffold28. Besides preventing stress-shielding of cells, a benefit of scaffold-free systems is the ability to control fiber alignment to generate anisotropy. In addition to eliciting native tissue-like properties, tension stimulation—especially CoTenS—was highly effective in driving anisotropy in neocartilage (Figure 2c); the tensile modulus in the direction parallel to tension stimulation was 1.7-times that of the perpendicular direction. Moreover, this anisotropy is driven by tension stimulation because anisotropy was not present in non-tension stimulated groups. These studies, thus, demonstrate that tension stimulation, when combined with matrix enhancing agents, can produce neocartilage constructs that recapitulate native tissue properties in the absence of scaffolds. In particular, anisotropy was successfully engineered in neocartilage without the use of exogenous materials.

Tension stimulation modes of action

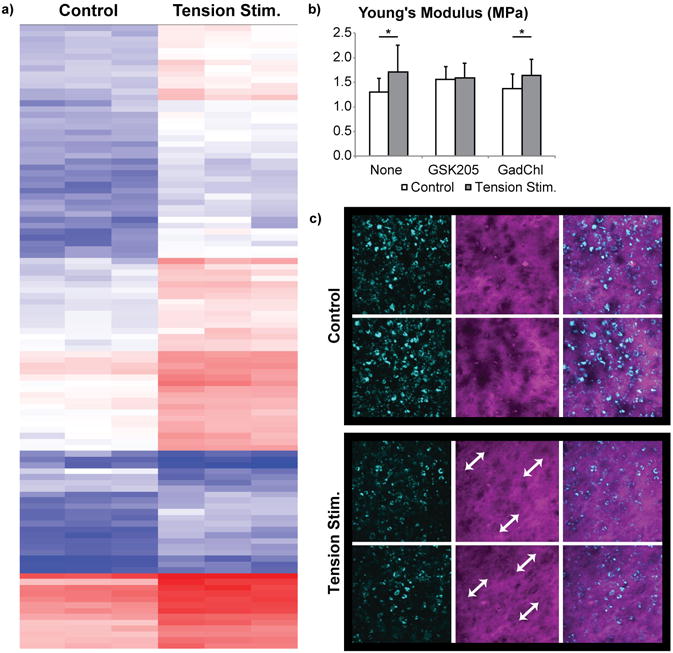

The enhanced functional properties of tension-stimulated neocartilage constructs are the result of complex cellular signaling and matrix remodeling events. Microarray analysis (2 hours post-tension) revealed that tension stimulation results in 99/9 up-/down-regulated genes, as compared to unloaded controls (Figure 3a, Supplemental Table 6). The major gene categories that appeared to be altered in response to tension stimulation relate to matrix remodeling enzymes, cellular signaling pathways, and membrane-bound receptors and channels. These findings suggest that tension stimulation up-regulates mRNA expression of molecules related to matrix remodeling (ADAMTS1, LOXL4), cell-matrix interactions (ITGA2), and signaling pathways (BMP2, SMAD7) (Supplemental Figure 3). ADAMTS1 plays a role in the maintenance of articular cartilage and is not associated with pathological changes29,30; up-regulation of ADAMTS1 in this study likely served to enhance matrix remodeling. LOXL4, like LOXL2, serves to cross-link collagen fibers within the ECM. Though lysyl oxidase-like protein 2 has been shown to be the major isoform of cartilage31, thus motivating our exogenous use of LOXL2 specifically, LOXL4 is also widely expressed in cartilage32. As in studies exposing cartilage cells to direct strain33, tension stimulation in these studies caused significant up-regulation of integrin α2, which may enable enhanced cell-matrix interaction. Finally, signaling of TGFβ1 and SMAD7 is known to function in a negative regulatory feedback loop34, while the balance of BMP2 and SMAD7 is known to regulate proper development and maturation of cartilage35. Tension stimulation may induce a similar BMP2/SMAD7 equilibrium to modulate matrix development. Though additional studies are necessary to examine thoroughly the mechanism of action of tension stimulation, the preliminary gene expression data suggest that the early response to tension stimulation involves changes in cellular signaling, cell-matrix interactions, and matrix remodeling, which, ultimately, may lead to neocartilage with enhanced properties.

Figure 3. Under tension stimulation, the TRPV4 ion channel is implicated to initiate matrix remodeling.

To investigate the effects of tension stimulation on increased tensile properties, microarray analysis and selective inhibitors were used to assess cell-based responses, while tissue-level responses (i.e., matrix alignment) were visualized using second harmonic generation (SHG) and quantified via mechanical analysis (see Figure 2). Microarray data (a) revealed significant differences in gene expression in the tension-treated group (red/blue indicate higher/lower amount of signal). Functional response (b) to tension stimulation is dependent on mechanosensitive TRPV4 channel activity, but, counter-intuitively, independent of stretch-activated channel (SAC) function. Student's t-test was used to assess statistical differences, *p<0.05. Data are represented as mean±SD. GSK205 and gadolinium chloride (GadChl) are inhibitors of the TRPV4 channel and SAC, respectively. SHG imaging (c) at 4 weeks revealed increased alignment of collagen fibers with tension stimulation, as shown with the white arrows.

In this study, we demonstrated that TRPV4 channel function plays a role in the mechanotransduction of tension stimulation. TRPV4 has previously been shown to be an important mechanosensitive ion channel that mediates the cellular response to compressive stimulation and ultimately affects neotissue functional properties21; without a functioning TRPV4 channel, compressive stimulation did not increase the compressive modulus. In our hands, TRPV4 agonism resulted in up to a 153% increase in tensile properties36,37. Here we showed that TRPV4 channel function is needed to sense tension stimulation and initiate signal transduction to result in functional property increases (Young's modulus), as GSK205 inhibition of TRPV4 during tension stimulation eliminated the emergent tissue-level response to tension (Figure 3b). While GSK205 alone appeared to cause a slight increase in tensile modulus, this effect was not significant (one-way ANOVA across groups, p = 0.77). In contrast to GSK205, non-specific inhibition of stretch-activated channels via gadolinium chloride did not affect the response to tension stimulation (Figure 3b), suggesting that the TRPV4 ion channel is more likely responsible for mechanotransduction. TRPV4 function and mechanosensation of tensile forces did not result in an increase in TRPV4 gene expression (Supplemental Figure 3). With the present study, the role of TRPV4 mechanotransduction is emerging more clearly. Prior literature has shown that acute inhibition of TRPV4 during compressive stimulation abrogates the effect of the stimulus21, implicating it in mechanotransduction. A TRPV4 agonist in the absence of tension leads to increased mechanical properties30. Finally, we show that applying a TRPV4 antagonist in combination with tension abolishes tension stimulation's effects. Thus, these studies further contribute to the role of TRPV4 as an essential element in sensing mechanical forces, specifically of tensile forces, to elicit cellular responses that enhance functional neotissue properties.

To assess matrix-level organizational changes resulting from tension stimulation, we used second harmonic generation to image the collagen fiber network. Second harmonic generation demonstrated that tension stimulation enhanced collagen fiber density and organization within neocartilage, resulting in alignment of fibers (Figure 3c). This remodeling process occurred over the final 2 weeks of culture to elicit significant differences in tensile properties between tension-stimulated and untreated neocartilage. Neotissues were also assessed immediately after loading to avoid detecting cellular responses to tensile loading. After 1 day of loading, neotissues were not significantly different from unloaded controls, suggesting that a permanent matrix response was not induced at this time scale (data not shown). Permanent deformation was present 2 days after tension stimulation (Supplemental Figure 1c, 1d). Following the tension stimulation regimen and after 2 additional weeks of culture, 28-day-old neocartilage treated with tension stimulation—either InTenS or CoTenS—were permanently elongated as compared to neocartilage without tension stimulation (Supplemental Figure 2c, 2d). This result was likely due in part to physical deformation of the matrix during the time course of tension stimulation; however, the cellular responses induced by tension stimulation, as discussed above, likely played a larger role in driving matrix remodeling. Continued development of neocartilage properties—leading to anisotropy and increased tensile modulus and strength—was initiated by tension stimulation, but required the remainder of tissue culture to develop and for the properties to emerge. At the matrix level, InTenS served to generate anisotropy within the collagen network, ultimately contributing to increases in neocartilage properties.

Collectively, our cell- and tissue-level analyses suggest that tension stimulation works primarily at the cellular level, inducing production of matrix enzymes to initiate matrix remodeling, up-regulation of BMP2/SMAD7 signaling, and expression of cell-matrix interaction proteins to improve mechanotransduction. Moreover, TRPV4 channel function was found to be a component of the cellular response to tension stimulation. Finally, InTenS served to align matrix collagen, resulting in substantial increases in tensile properties. These tension-induced changes, when combined with up-regulation of collagen synthesis by TGFβ1, led to synergistic increases in functional properties. Specifically, TGFβ1 increased the matrix density, while tension stimulation enhanced the cell's ability to sense mechanical forces through increased integration with the matrix. Ultimately, the integration of these cell- and tissue-level responses to tension led to functional changes in tensile modulus and strength toward those of native tissues.

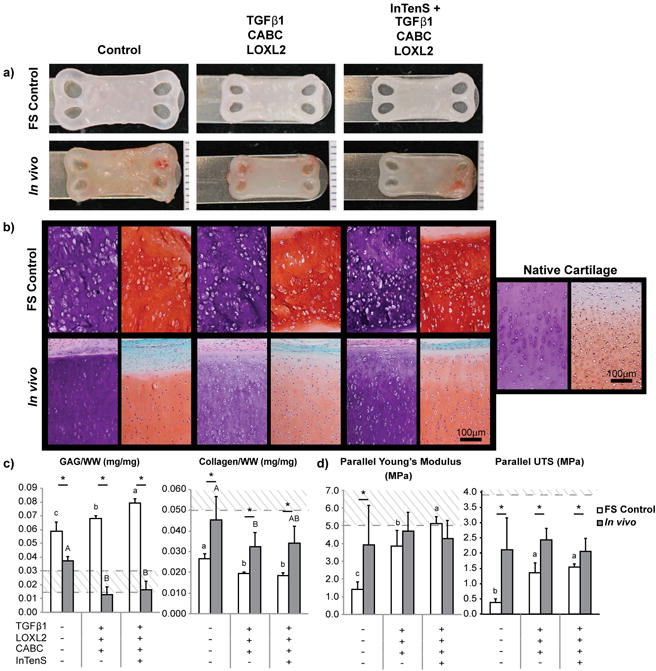

In vivo implantation of InTenS-treated neocartilage

Subcutaneous implantation of neocartilage constructs treated with InTenS + TGFβ1/LOXL2/CABC and with TGFβ1/LOXL2/CABC in athymic mice allowed for assessment of the long-term stability of tensile properties in an in vivo environment. Before implantation, all neocartilage groups exhibited properties similar to those obtained in the other experiments of this study (Figure 4). After 4 weeks in vivo, neocartilage shape and structure were maintained, and growth was limited, as compared to constructs grown in vitro (free-swelling culture controls) (Figure 4a). Histological analysis revealed substantial differences between free-swelling controls and constructs implanted in vivo (Figure 4b). In both free-swelling and in vivo conditions, the InTenS + TGFβ1/LOXL2/CABC treatment induced richer deposition of GAGs compared to neocartilage treated with TGFβ1/LOXL2/CABC. Interestingly, the in vivo environment elicited changes in the cellular morphology of stimulated constructs, with cells in these tissues appearing to orient themselves in a columnar fashion perpendicular to the tissue surface. This organization is reminiscent of native articular cartilage. The use of scaffold-free method in tissue engineering led to a slightly higher cellularity in engineered neocartilage compared to native articular cartilage (Figure 4b). The high cellularity is reminiscent of juvenile articular cartilage, which has a higher regeneration potential38. As the implanted cartilage matures the cellularity is expected to decrease. The biochemical and mechanical properties of implanted neocartilage reflected values closer to those of native articular cartilage, as compared to those in free-swelling culture (Figure 4c). The free-swelling control neocartilage treated with InTenS + TGFβ1/LOXL2/CABC possessed the highest tensile properties as compared to the TGFβ1/LOXL2/CABC-treated and untreated control groups, despite receiving no tension stimulation for the remaining 6 of 8 weeks of culture. This result suggests that properties attained by tension stimulation are persistent and can be maintained in culture. We previously reported that the subcutaneous environment leads to increased neocartilage properties19. In this study specifically, collagen content, Young's modulus, and UTS of in vivo implanted constructs reach 90%, 94%, and 60% of native articular cartilage values, respectively, as compared to those grown in free-swelling culture (54%, 102%, and 38%, respectively). Thus, the subcutaneous in vivo environment not only maintains or further enhances the properties of treated neocartilage toward those of native articular cartilage, but also results in neocartilage that is morphologically reminiscent of native tissues.

Figure 4. The in vivo environment results in neocartilage with morphological structure reminiscent of native articular cartilage.

Implanted neocartilage constructs retained their shape after excision and are smaller compared to free-swelling (FS) culture conditions (a). Formalin-fixed, 5μm tissue sections were stained with H&E and Safranin-O/Fast Green (b) to visualize matrix and glycosaminoglycan (GAG) distribution, respectively. Staining in the GAG-rich FS neocartilage constructs was uniformly distributed. Implanted neocartilage attained a columnar morphology and matrix distribution reminiscent of native articular cartilage. Flatter cells can be identified toward the surface of the tissue, whereas elongated cells were distributed toward the center. In vivo conditions resulted in neocartilage with biochemical properties (c) closer to native tissue values, as indicated by the dotted lines, reducing GAG and increasing collagen content as compared to FS culture. InTenS-treated neocartilage in FS culture maintained a significantly higher Young's modulus than neocartilage treated with bioactive agents alone, which was greater than untreated controls (d). Further, tensile properties were maintained (for Young's modulus) or increased (for UTS) in the in vivo environment. Two one-way ANOVAs, followed by a Tukey's post hoc test, were performed to statistically assess the results. Groups not connected by the same letter are statistically significant. Student's t-test was also performed to compare FS and in vivo explanted groups, *p<0.05. Data are represented as mean±SD.

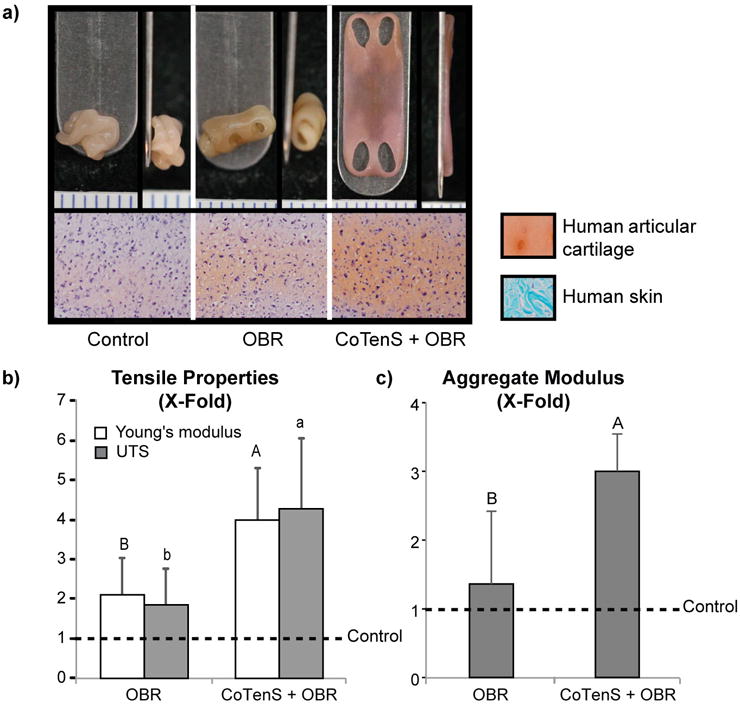

Translation of tension stimulation to a human cell source

The increases in neocartilage tensile properties described in the preceding sections were achieved using a bovine cell source. Inasmuch as the ultimate goal of engineering mechanically robust neocartilage is clinical translation to human patients, we examined the effectiveness of the newly developed CoTenS regimen in passaged human articular chondrocytes. Importantly, without tension stimulation, human neocartilage of the large dimensions employed here could not be engineered. Specifically, unstimulated and OBR-treated neocartilage contracted and folded dramatically, whereas tension-treated constructs maintained their flat morphology and dimensions (Figure 5a). Similar to the effects seen with bovine cells, tension stimulation, in combination with OBR, drove significant increases in human neocartilage tensile and compressive stiffness, reaching 4.0-times and 3.0-times of unstimulated control values, and even 1.9-times and 2.2-times of OBR values alone, respectively (Figure 5b and 5c). The absolute values achieved for human-derived neocartilage are not yet on par with those of native human adult cartilage39,40, but are the highest properties of scaffold-free, human cell-based engineered cartilage achieved to-date. In addition to increases in tensile properties, human neocartilage constructs also exhibited statistically significant tensile anisotropy in response to tension stimulation, with the direction parallel to tensile loading achieving a Young's modulus of 2.3±0.7MPa versus 1.4±0.7MPa in the perpendicular direction. Since human articular cartilage is anisotropic—as evidenced by split lines at the surface of the tissue41—the generation of anisotropy in our human cell-derived neocartilage supports the translational potential of tension stimulation in the self-assembling process to generate neocartilage similar to the native tissue in terms of functional properties.

Figure 5. Translation of tension stimulation to human neocartilage.

CoTenS was necessary in achieving flat and robust human neocartilage; without tension, neocartilage constructs folded and wrinkled non-uniformly (a, top). Tension stimulation also increased GAG content in the neocartilage, as compared to untreated constructs or those treated with an optimized bioactive regimen (OBR) (a, bottom). In addition, tension stimulation significantly increased the mechanical properties of human neocartilage. Young's modulus and UTS of treated groups were normalized to those of untreated control, and fold-changes with respect to untreated control (dotted line) are presented (b). The absolute tensile properties are presented in Supplemental Table 4. CoTenS + OBR enhanced the tensile modulus and strength to 4.0-times and 4.3-times, respectively, of control values, significantly greater than values achieved by OBR alone. Similarly, the compressive stiffness, as indicated by the aggregate modulus, significantly increased 3.0-times over control as a result of CoTenS + OBR treatment (c). Two one-way ANOVAs, followed by a Tukey's post hoc test, were used to statistically assess the results. Groups not connected by the same letter are statistically significant. Data are represented as mean±SD.

Conclusions and future directions

Despite the existence of tensile loading capabilities for musculoskeletal tissue engineering, successful achievement of native tissue-like tensile properties has not yet been obtained. Indeed, static and dynamic tensile loading has been applied in tendon and ligament engineering42-44, but these fall short of achieving native tissue-like properties45. The successful application of static or dynamic tensile loading to neocartilage is significantly more limited, with only a handful of studies on dynamic tensile load application demonstrating the potential of tension application.46-48 It should be noted that no tension stimulation studies have been performed in scaffold-free systems; also, no effective tension stimulation regimens have been identified in cartilage tissue engineering. Therefore, it is significant that this body of work has generated scaffold-free musculoskeletal tissues with tensile properties on the order of native tissue values, using custom-fabricated stimulation devices and intermittent and continuous tension stimulation regimens.

The scaffold-free tissue formation process used in this study further contributes to the successful application of tension stimulation. Scaffold-based methods can result in discontinuities in matrix distribution and stress-shielding of resident cells49-51. Application of tensile load to a scaffold-based neocartilage, then, may not allow for appropriate force transfer from the bulk tissue to the cellular level. As a result, a scaffold-free neocartilage system, where cells synthesize and integrate intimately with their ECM and do not rely on migration, integration, or remodeling as may be needed with scaffolds, may be more amenable to tensile loading. Enhanced matrix integration allows for direct mechanotransduction of the applied tensile load from the bulk tissue level to the matrix and cellular levels without dampening via an exogenous scaffold. Unique aspects of the current system include the combination of tension stimulation with a scaffold-free approach, the avoidance of stress shielding resulting in direct application of mechanical stimulation to cells, and the use of an articular cartilage model system since tension is not thought to be the prevailing stimulus in cartilage. Additional studies on the use of tensile loading in both scaffold-free and scaffold-based musculoskeletal tissue formation efforts will elucidate tensile loading regimens that can recapitulate native tissue-like properties in a variety of musculoskeletal tissues. Similarly, continued exploration of the mechanisms by which tension stimulation induces the significant enhancements in scaffold-free neocartilage tensile properties achieved in these studies would further improve the field's understanding of mechanotransduction.

Here, we report the design and use of tensile loading devices that successfully apply intermittent and continuous tension stimulation regimens to engineer neocartilage with greater tensile properties. The effects of tension stimulation and its interactions with TGFβ1, CABC, and LOXL2—agents specifically selected for their role in enhancing the collagen network—are multifaceted and are the topic of continued exploration by our group. The scaffold-free, cell-based neocartilage constructs generated herein possess the highest tensile properties to-date by rationally targeting matrix synthesis and collagen organization via the combination of tension and matrix enhancing agents. We showed that the mechanosensitive ion channel TRPV4 is implicated in the successful application of tension stimulation, resulting in increased functional properties. The in vivo microenvironment was shown to enhance the tissues' biochemical and mechanical properties and to mimic native cartilage's morphological structure. Finally, we translated tension stimulation to human neocartilage to enhance the tissue's mechanical properties, toward those of native tissues. These loading devices may be amenable to the scaffold-free or scaffold-based engineering of other musculoskeletal tissues such as ligament, tendon, muscle, or bone. In the case of articular cartilage, we demonstrated increases in tensile modulus and strength nearly 6-times those of untreated neocartilage, generating scaffold-free neocartilage with native tissue-like properties. Similarly, tension stimulation of human neocartilage reached tensile properties over 4-times those of untreated controls, demonstrating the translational nature of the regimen. Achievement of these mechanical properties suggests better graft survival and function when translated to the clinic. Our examination of tension stimulation regimens in tissue formation enhances our understanding of the importance of biomechanics in driving tissue formation in a biomimetic fashion.

Methods

Application of tension stimulation

Design of tension stimulation devices

To create custom devices capable of applying tension stimulation to neocartilage, the open source MakerBot was modified to produce the devices shown in Figure 1a and 1b. The device designs incorporate stainless steel rods, onto which neocartilage constructs can be loaded. The rationale for using rod systems was to avoid directly gripping and potentially damaging the tissues.

Shape-specific mold design

Toward applying tensile strains to neotissues, a rectangular construct was desired. To be compatible with the tensile loading devices, four openings were engineered into the neocartilage to avoid generation of stress concentrations that may result from the use of a punch. A positive mold was designed and 3D printed with biocompatible materials to generate a well-maker, which was placed in molten 2% agarose to generate wells for forming the self-assembled constructs. Each well was rinsed with four exchanges of Dulbecco's Modified Eagles Medium prior to use.

Self-assembling process for bovine and human neocartilage

Articular chondrocytes were harvested from the distal femur of juvenile bovine joints (Research 87, Boston, MA) as previously described52. Neocartilage was formed using the self-assembling process53 at a seeding density of 8 million cells in 100μL of chondrogenic medium (CHG)52 per 13×8mm construct. Human articular chondrocytes were obtained from three Caucasian, male donors, ages 19, 21, and 43, with no known musculoskeletal pathology (Musculoskeletal Transplant Foundation, Kansas City, MO). The isolated cells were passaged and chondrotuned as described previously 54. Briefly, human articular chondrocytes were expanded in TGFβ1, bFGF, and PDGF-bb-containing (all from Peprotech, Rocky Hills, NJ) CHG to passage 3. Then, the cells were cultured in 3D aggregates to redifferentiate them into chondrocytes, after which cells were self-assembled at 7 million cells per 13x8mm construct.

Applied tension stimulation

The InTenS regimen involved subjecting neocartilage to 18-20% tensile strain for 1 hour per day, during days 10-14 of the 28-day culture period. Each treatment group was subjected to InTenS with or without bioactive agents. The CoTenS regimen involved the application of strain as follows: 18% on day 7, followed by approximately 4.9-6.5% additional strain applied each day from days 8-12 and then held constant until day 28; tensile strain in this group was, thus, applied continuously from days 7-28.

Matrix enhancing treatment regimens

TGFβ1 at 10ng/mL was used from days 1-28 of the 28-day culture period. In the InTenS regimen, CABC (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) at 2U/mL CHG was applied for 4 hours on day 7. After CABC treatment, neocartilage was thoroughly rinsed with CHG. From days 15-28, 0.15μg/mL lysyl oxidase-like protein 2 (SignalChem, Richmond, British Columbia) with 1.6μg/ml copper sulfate (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and 0.146μg/ml hydroxylysine (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), defined as LOXL2, were applied. In studies employing CoTenS, CABC was applied at day 8, and LOXL2 was used from days 10-28, with both factors applied at the same concentrations as in InTenS. This regimen, referred to as OBR, was logistically necessary to accommodate continuous tension stimulation. Medium was changed every other day.

Ion channel inhibition

For channel inhibitor studies, GSK205 (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) and gadolinium chloride (GadChl; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), were used to block the function of the TRPV4 channel and non-specifically block stretch-activated channels, respectively55,56. Neocartilage was transferred to CHG containing 10μM GSK205, 10μM GadChl, or no drug and allowed to equilibrate for 30 minutes. InTenS was then applied to neocartilage in a bath of GSK205 or GadChl to inhibit channel function while neocartilage was subjected to tensile strain.

Neocartilage characterization

Mechanical and biochemical analyses

Tensile and compressive tests (n=6 per group) and biochemical evaluation (n=6 per group) for collagen, sulfated GAG, and DNA content were performed as previously described52. Dumbbell-shaped tensile test samples were obtained in the direction parallel and perpendicular to the axis of tension stimulation and as indicated in Figure 1e and Supplemental Figure 1a. Tensile Young's modulus and UTS are reported (although structural properties are also provided in Supplemental Table 7). In each experiment of the study, untreated group was included as control. When comparing data across multiple experiments in the study, Young's modulus and UTS from treated groups were normalized to those of untreated control, and fold-changes with respect to untreated control were presented. Collagen and GAG data were normalized to tissue wet weight, by dividing the weight of collagen or GAG in sample by sample wet weight, and reported as collagen/WW and GAG/WW. Cellularity values in constructs are reported from measuring DNA content.

Microarray analysis

RNA was isolated 2 hours post-InTenS on day 10 using an RNAqueous-micro kit (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA); untreated samples were also prepared on day 10 of culture. Reverse transcription was performed to generate cDNA. InTenS-treated and untreated cDNA were hybridized to Bovine Gene 1.0 ST Arrays (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA) based on the manufacturer's instructions (n=3 per group). Expression results were analyzed using the Affymetrix Transcriptome Analysis Console. Results were filtered based on a minimum 2-fold change and p<0.05.

Gene expression

Quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) was performed on genes of interest that were up-regulated via microarray analysis. Total RNA was reverse transcribed using random primers (Amersham Biosciences, Little Chalfont, UK), with GAPDH primers used to control for cDNA concentration in separate PCR reactions for each sample. Primers for GADPH, ADAMTS1, LOXL4, BMP2, SMAD7, ITGA2, and TRPV4 were designed using Primer3 and are shown in Supplemental Table 5. To each PCR reaction (triplicates), LightCycler Fast Start DNA Master SYBR Green Mix (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) was added, along with cDNA and 1pmol primer in a total reaction volume of 10μl. Ct values were converted to fold expression changes (2–ΔΔCt values) after normalization to GAPDH expression levels.

Histological analysis

Free-swelling and explanted neocartilage samples were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin before paraffin-embedding and sectioning at 5μm. Slides were stained with H&E, picrosirius red, and Safranin-O/Fast Green.

Second harmonic generation

For two-photon imaging, whole neocartilage samples were fixed in 4% neutral buffered formalin for 3 days before storing in 1% sodium azide. Second harmonic imaging was performed as previously described57. Z-stacks were captured at 3μm increments through the neocartilage thickness. Stacks were Z-projected at maximum intensity using ImageJ software to normalize across samples.

Finite element modeling

Finite element analysis was performed using FEBio 2.1 (febio.org) to appropriately model the biphasic behavior of engineered neocartilage58. Due to the symmetry in loading and geometry, a quarter of the system was modeled and analyzed. The neocartilage geometry was modeled using Abaqus 6.14 (3ds.com) and meshed with 2104 solid elements. FEBio was then used to model the tissue as a biphasic material, based on experimental measurements of neocartilage properties at day 10. The stainless steel loading pole through the neocartilage opening was modeled as a rigid body. A strain of 18% was applied to the model.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using JMP Pro 12 (jmp.com) statistical package. Analysis of variance, followed by Tukey's post hoc test, was performed for multiple group comparisons, with statistical significance set at p<0.05. Student's t-test was performed to compare two groups, with statistical significance also set at p<0.05. Specific p-values were also indicated where appropriate. Data were presented as mean±SD. Samples were excluded from analysis only if a box plot deemed samples outliers. N=8 was used for all InTenS experiments, including animal work, while N=6 was used in CoTenS experiments. N=3 was used for microarray analysis. A power analysis confirmed n=6 sufficient to detect statistical significance in studies employing the self-assembling process for neocartilage.

Animal studies

Athymic male mice (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA), aged 6-8 weeks, were used under the approval of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of UC Davis (IACUC protocol #18612). Under general anesthesia, one 1.5cm-long incision was made along the dorsal surface of 12 animals. Bilateral pouches were formed on either side; one neocartilage sample (untreated, TGFβ1/CABC/LOXL2-treated, or InTenS + TGFβ1/CABC/LOXL2-treated) was randomly inserted per pouch (n=8 per group), with no animal receiving two samples from the same experimental group. No blinding of investigators was used. Wounds were closed with surgical clips. Mice were humanely sacrificed 4 weeks after implantation. Mechanical, biochemical, and histological analyses were performed on explanted constructs (as described above).

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available as Supplemental Tables or from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was made possible with the support of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) awards R01 AR067821 (National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases), R01 DE015038 (National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research), and T32 GM00799 (National Institute of General Medical Sciences) for JKL. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. Microarray analysis was made possible by the UC Davis Comprehensive Cancer Center Genomics Shared Resource (NCI P30 CA93373). We also thank L. Cassereau and the Weaver laboratory for assistance with second harmonic generation imaging.

Footnotes

Author contributions: JKL, LWH, JCH, and KAA were responsible for the design and execution of InTenS and CoTenS studies. NP and JKL together conducted all animal work, while NP, AA, and LWH performed the human articular chondrocyte experiments. CAG assisted in the design and fabrication of the tensile loading device. JKL, LWH, NP, AA, and CAG collected all data. AA performed finite element modeling and analysis. JKL and LWH performed the data analysis. JKL, LWH, JCH, and KAA prepared the manuscript.

Competing Interests statement: The authors have no competing interests to declare.

References

- 1.Responte DJ, Lee JK, Hu JC, Athanasiou KA. Biomechanics-driven chondrogenesis: from embryo to adult. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2012;26:3614–3624. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-207241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vos T, et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188. countries, 1990-2013 a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. The Lancet. 2015 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60692-4. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60692-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Ogle W. Aristotle's De Partibus Animalium. Oxford: Clarendon Press; 1911. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vacanti CA. The history of tissue engineering. J Cell Mol Med. 2006;10:569–576. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2006.tb00421.x. doi:D -NLM: PMC3933143 EDAT- 2006/09/23 09:00 MHDA- 2007/01/16 09:00 CRDT-2006/09/23 09:00 AID - 010.003.20 [pii] PST - ppublish. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huey DJ, Hu JC, Athanasiou KA. Unlike bone, cartilage regeneration remains elusive. Science. 2012;338:917–921. doi: 10.1126/science.1222454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Little CJ, Bawolin NK, Chen X. Mechanical Properties of Natural Cartilage and Tissue-Engineered Constructs. Tissue Engineering Part B: Reviews. 2011;17:213–227. doi: 10.1089/ten.teb.2010.0572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eleswarapu SV, Responte DJ, Athanasiou KA. Tensile properties, collagen content, and crosslinks in connective tissues of the immature knee joint. PloS one. 2011;6:e26178. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Makris EA, Gomoll AH, Malizos KN, Hu JC, Athanasiou KA. Repair and tissue engineering techniques for articular cartilage. Nature reviews Rheumatology. 2014 doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2014.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Athanasiou KA, Responte DJ, Brown WE, Hu JC. Harnessing biomechanics to develop cartilage regeneration strategies. J Biomech Eng. 2015;137:020901. doi: 10.1115/1.4028825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee C, Grad S, Wimmer M, Alini M. The Influence of Mechanical Stimuli on Articular Cartilage Tissue Engineering. Topics in Tissue Engineering. 2006;2 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen C, et al. Cyclic Equibiaxial Tensile Strain Alters Gene Expression of Chondrocytes via Histone Deacetylase 4 Shuttling. PLOS ONE. 2016;11:e0154951. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0154951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu QQ, Chen Q. Mechanoregulation of chondrocyte proliferation, maturation, and hypertrophy: ion-channel dependent transduction of matrix deformation signals. Exp Cell Res. 2000;256:383–391. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.4847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang D, Chang Tr Tr, Aggarwal A, Lee RC, Ehrlich HP. Mechanisms and dynamics of mechanical strengthening in ligament-equivalent fibroblast-populated collagen matrices. 1993 doi: 10.1007/BF02368184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Connelly JT, Vanderploeg EJ, Levenston ME. The influence of cyclic tension amplitude on chondrocyte matrix synthesis: Experimental and finite element analyses. Biorheology. 2004;41:377–387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vanderploeg EJ, Wilson CG, Levenston ME. Articular chondrocytes derived from distinct tissue zones differentially respond to in vitro oscillatory tensile loading. Osteoarthritis and cartilage / OARS, Osteoarthritis Research Society. 2008;16:1228–1236. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2008.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Erickson IE, et al. High mesenchymal stem cell seeding densities in hyaluronic acid hydrogels produce engineered cartilage with native tissue properties. Acta Biomater. 2012;8:3027–3034. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2012.04.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nims RJ, Cigan AD, Albro MB, Hung CT, Ateshian GA. Synthesis rates and binding kinetics of matrix products in engineered cartilage constructs using chondrocyte-seeded agarose gels. Journal of Biomechanics. 2014;47:2165–2172. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2013.10.044. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiomech.2013.10.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elder BD, Athanasiou KA. Systematic assessment of growth factor treatment on biochemical and biomechanical properties of engineered articular cartilage constructs. Osteoarthritis and cartilage / OARS, Osteoarthritis Research Society. 2009;17:114–123. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Responte DJ, Arzi B, Natoli RM, Hu JC, Athanasiou KA. Mechanisms underlying the synergistic enhancement of self-assembled neocartilage treated with chondroitinase-ABC and TGF-beta1. Biomaterials. 2012;33:3187–3194. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.01.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Makris EA, Responte DJ, Paschos NK, Hu JC, Athanasiou KA. Developing functional musculoskeletal tissues through hypoxia and lysyl oxidase-induced collagen cross-linking. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:E4832–4841. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1414271111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O'Conor CJ, Leddy HA, Benefield HC, Liedtke WB, Guilak F. TRPV4-mediated mechanotransduction regulates the metabolic response of chondrocytes to dynamic loading. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:1316–1321. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1319569111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hu JC, Athanasiou KA. A self-assembling process in articular cartilage tissue engineering. Tissue engineering. 2006;12:969–979. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yaeger PC, et al. Synergistic Action of Transforming Growth Factor-β and Insulin-like Growth Factor-I Induces Expression of Type II Collagen and Aggrecan Genes in Adult Human Articular Chondrocytes. Experimental cell research. 1997;237:318–325. doi: 10.1006/excr.1997.3781. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/excr.1997.3781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blunk T, et al. Differential effects of growth factors on tissue-engineered cartilage. Tissue Eng. 2002;8:73–84. doi: 10.1089/107632702753503072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Asanbaeva A, Masuda K, Thonar EJ, Klisch SM, Sah RL. Mechanisms of cartilage growth: modulation of balance between proteoglycan and collagen in vitro using chondroitinase ABC. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:188–198. doi: 10.1002/art.22298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Williamson AK, Chen AC, Masuda K, Thonar EJMA, Sah RL. Tensile mechanical properties of bovine articular cartilage: Variations with growth and relationships to collagen network components. Journal of Orthopaedic Research. 2003;21:872–880. doi: 10.1016/s0736-02660266(03)00030-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Atsawasuwan P, et al. Lysyl oxidase binds transforming growth factor-beta and regulates its signaling via amine oxidase activity. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:34229–34240. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803142200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Steele JA, et al. Combinatorial scaffold morphologies for zonal articular cartilage engineering. Acta Biomater. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2013.12.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kevorkian L, et al. Expression profiling of metalloproteinases and their inhibitors in cartilage. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2004;50:131–141. doi: 10.1002/art.11433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wachsmuth L, et al. ADAMTS-1, a gene product of articular chondrocytes in vivo and in vitro, is downregulated by interleukin 1beta. The Journal of Rheumatology. 2004;31:315–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Iftikhar M, et al. Lysyl oxidase-like-2 (LOXL2) is a major isoform in chondrocytes and is critically required for differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:909–918. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.155622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ito H, et al. Molecular Cloning and Biological Activity of a Novel Lysyl Oxidase-related Gene Expressed in Cartilage. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276:24023–24029. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100861200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lahiji K, Polotsky A, Hungerford D, Frondoza C. Cyclic strain stimulates proliferative capacity, α2 and α5. integrin, gene marker expression by human articular chondrocytes propagated on flexible silicone membranes. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol-Animal. 2004;40:138–142. doi: 10.1290/1543-706X(2004)40<138:CSSPCA>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nakao A, et al. Identification of Smad7, a TGF[beta]-inducible antagonist of TGF-[beta] signalling. Nature. 1997;389:631–635. doi: 10.1038/39369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Iwai T, Murai J, Yoshikawa H, Tsumaki N. Smad7 Inhibits Chondrocyte Differentiation at Multiple Steps during Endochondral Bone Formation and Down-regulates p38 MAPK Pathways. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2008;283:27154–27164. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801175200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eleswarapu SV, Athanasiou KA. TRPV4 channel activation improves the tensile properties of self-assembled articular cartilage constructs. Acta biomaterialia. 2013;9:5554–5561. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2012.10.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee JK, Gegg CA, Hu JC, Kass PH, Athanasiou KA. Promoting increased mechanical properties of tissue engineered neocartilage via the application of hyperosmolarity and 4alpha-phorbol 12,13-didecanoate (4alphaPDD) J Biomech. 2014;47:3712–3718. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2014.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu H, et al. Enhanced tissue regeneration potential of juvenile articular cartilage. The American journal of sports medicine. 2013;41:2658–2667. doi: 10.1177/0363546513502945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Temple MM, et al. Age- and site-associated biomechanical weakening of human articular cartilage of the femoral condyle. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage. 2007;15:1042–1052. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Temple-Wong MM, et al. Biomechanical, structural, and biochemical indices of degenerative and osteoarthritic deterioration of adult human articular cartilage of the femoral condyle. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage. 2009;17:1469–1476. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2009.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Below S, Arnoczky SP, Dodds J, Kooima C, Walter N. The split-line pattern of the distal femur: A consideration in the orientation of autologous cartilage grafts. Arthroscopy. 2002;18:613–617. doi: 10.1053/jars.2002.29877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Butler DL, et al. Functional tissue engineering for tendon repair: A multidisciplinary strategy using mesenchymal stem cells, bioscaffolds, and mechanical stimulation. J Orthop Res. 2008;26:1–9. doi: 10.1002/jor.20456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Henshaw DR, Attia E, Bhargava M, Hannafin JA. Canine ACL fibroblast integrin expression and cell alignment in response to cyclic tensile strain in three-dimensional collagen gels. J Orthop Res. 2006;24:481–490. doi: 10.1002/jor.20050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moreau JE, Bramono DS, Horan RL, Kaplan DL, Altman GH. Sequential biochemical and mechanical stimulation in the development of tissue-engineered ligaments. Tissue Eng Part A. 2008;14:1161–1172. doi: 10.1089/tea.2007.0147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rodrigues MT, Reis RL, Gomes ME. Engineering tendon and ligament tissues: present developments towards successful clinical products. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2013;7:673–686. doi: 10.1002/term.1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Connelly JT, Vanderploeg EJ, Mouw JK, Wilson CG, Levenston ME. Tensile Loading Modulates Bone Marrow Stromal Cell Differentiation and the Development of Engineered Fibrocartilage Constructs. Tissue Engineering Part A. 2010;16:1913–1923. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2009.0561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen JP, Liao HT, Cheng TH. Cultivation of chondrocytes and meniscus cells in thermo-responsive hydrogels containing chitosan and hyaluronic acid under mechanical tensile stimulation. Journal of Mechanics in Medicine & Biology. 2011;11:1003–1015. [Google Scholar]

- 48.McMahon L, Reid A, Campbell V, Prendergast P. Regulatory Effects of Mechanical Strain on the Chondrogenic Differentiation of MSCs in a Collagen-GAG Scaffold: Experimental and Computational Analysis. Annals of Biomedical Engineering. 2008;36:185–194. doi: 10.1007/s10439-007-9416-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hung CT, Mauck Rl, Wang CCB, Lima EG, Ateshian GA. A paradigm for functional tissue engineering of articular cartilage via applied physiologic deformational loading. 2004 doi: 10.1023/b:abme.0000007789.99565.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bryant SJ, Anseth KS. Controlling the spatial distribution of ECM components in degradable PEG hydrogels for tissue engineering cartilage. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2003;64:70–79. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.10319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Demirbag B, Huri PY, Kose GT, Buyuksungur A, Hasirci V. Advanced cell therapies with and without scaffolds. Biotechnology journal. 2011;6:1437–1453. doi: 10.1002/biot.201100261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lee JK, Gegg CA, Hu JC, Reddi AH, Athanasiou KA. Thyroid hormones enhance the biomechanical functionality of scaffold-free neocartilage. Arthritis Res Ther. 2015;17:28. doi: 10.1186/s13075-015-0541-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hu JC, Athanasiou KAA. Self-Assembling Process in Articular Cartilage Tissue Engineering. Tissue Engineering. 2006;12:969–979. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Murphy MK, Huey DJ, Hu JC, Athanasiou KA. TGF-beta1, GDF-5, and BMP-2 stimulation induces chondrogenesis in expanded human articular chondrocytes and marrow-derived stromal cells. Stem cells. 2015;33:762–773. doi: 10.1002/stem.1890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Guilak F, et al. Mechanically induced calcium waves in articular chondrocytes are inhibited by gadolinium and amiloride. Journal of Orthopaedic Research. 1999;17:421–429. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100170319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Phan MN, et al. Functional characterization of TRPV4 as an osmotically sensitive ion channel in porcine articular chondrocytes. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:3028–3037. doi: 10.1002/art.24799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Acerbi I, et al. Human breast cancer invasion and aggression correlates with ECM stiffening and immune cell infiltration. Integrative Biology. 2015 doi: 10.1039/C5IB00040H. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Maas SA, Ellis BJ, Ateshian GA, Weiss JA. FEBio: finite elements for biomechanics. J Biomech Eng. 2012;134:011005. doi: 10.1115/1.4005694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available as Supplemental Tables or from the corresponding author on reasonable request.