Abstract

Nurses are knowledgeable regarding the importance of health-promoting activities such as healthy eating, physical activity, stress management, sleep hygiene, and maintaining healthy relationships. However, this knowledge may not translate into nurses’ own self-care. Nurses may not follow recommended guidelines for physical activity and proper nutrition. Long hours, work overload, and shift work associated with nursing practice can be stressful and contribute to job dissatisfaction, burnout, and health consequences such as obesity and sleep disturbances. The purpose of this article is to provide an overview of research examining nurses’ participation in health-promoting behaviors, including intrinsic and extrinsic factors that may influence nurses’ participation in these activities. This article also provides recommendations for perioperative nurse leaders regarding strategies to incorporate into the nursing workplace to improve the health of the staff nurses by increasing health-promoting behaviors.

Keywords: self-care, health-promoting behaviors, healthy workplace, burnout, stress

Noncommunicable, lifestyle-related diseases including obesity, cardiovascular disease, and type 2 diabetes have reached epidemic levels in the general population,1 and perioperative nurses may be at risk. Nurses are at the forefront in the battle to fight this epidemic, and with nursing as the most trusted of all professions,2 they are in a key position to counsel their patients regarding the importance of engaging in healthy lifestyle behaviors such as eating a nutritious diet, participating in regular physical activity, getting adequate sleep, reducing stress, and avoiding tobacco and excessive alcohol intake. However, the knowledge that nurses possess regarding health-promoting behaviors may not translate into nurses’ own self-care. The following case study describes a nurse who is struggling to practice health-promoting behaviors and how her particular job requirements specifically add to the difficulty of adopting and adhering to a healthy lifestyle.

CASE STUDY: IDENTIFYING THE PROBLEM

Ms Y is a 52-year-old perioperative nurse working 12-hour shifts in a busy, 800-bed academic medical center. As a 25-year veteran, she is one of the most experienced members of the OR team. She is married and has three teenage children at home, in addition to her aging parents. All three of her children are on multiple sports teams, consuming nearly all of her free time, and she is worried about her 81-year-old mother who has recently begun showing early signs of dementia.

During the past two years, administration changes have occurred at work, causing morale to drop and several nurses to leave. As the demands of her job and family have increased, Ms Y rarely has time for the activities she finds personally rewarding, such as attending yoga or spinning classes with her two closest friends, cooking healthy meals, and traveling with her family. Because of the complexities of the surgeries to which she is assigned, it is common for her shift to extend past 12 hours, leaving her limited time with her family and making it nearly impossible to get a good night’s sleep. On those nights, she usually grabs fast food on her way home. At work, her busy OR schedule leaves her feeling like she is always eating on the run, and if she misses the narrow window during which the hospital cafeteria provides full service, she is left with few healthy options. At those times, she grabs something from the vending machines or the collection of empty-calorie snacks supplied by coworkers. Not surprisingly, Ms Y has gained 20 pounds in the past five years. The weight gain coupled with long hours standing in the OR and lifting heavy patients has contributed to chronic low back pain. She is motivated to make some healthy behavior changes but is struggling with how to begin the journey to a more balanced, healthy lifestyle.

BACKGROUND

Nurses’ health has been the subject of research, most notably through the Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women’s Hospital Women’s Health Study,3 which followed almost 40,000 health professionals, nearly all nurses, for more than 20 years, and has contributed to key advances in women’s health. Because of this study and other research, it is clear that not only do nurses sometimes fail to engage in healthy behaviors, but that the environments in which nurses work may also contribute to poor health behaviors.4 Nurses need to engage in health promotion and disease prevention personally and professionally, and nurse leaders in complex health care environments must strive to be active partners who promote and foster self-care and wellness.

When examining health behaviors, it is important to make a distinction between health risk behaviors, health screening behaviors, and health promotion behaviors.5 Health risk behaviors include smoking, illicit drug use, and excessive alcohol consumption. Smoking in nurses has been well-documented, and despite clear evidence of the dangers of smoking, nurses appear to smoke at rates similar to the general population.6 Substance abuse in general has been recognized as a serious issue among nurses for more than a century and has received both research and policy attention.7

Health screening behaviors, defined as engaging in routine physical examinations and disease screenings to detect and treat preclinical health conditions,8 have received considerably less research attention than health risk behaviors in nurses. However, stress and social support are two facets that could influence health screening behaviors. Su et al9 found that Taiwanese nurses with higher job stress were less likely to undergo Pap smears than those with lower job stress. In another study, Brazilian nurses with higher levels of social support were more likely to undergo mammograms and Pap smears than those with lower levels of support.10

Health promotion behaviors (eg, physical activity, healthy eating, stress management, sleep hygiene, healthy relationships) increase personal resiliency and improve health.11 These behaviors are critically important in reversing the epidemic of obesity and obesity-related diseases currently afflicting our country.

NURSES AND HEALTH-PROMOTING BEHAVIORS

Health-promoting behaviors are important in preventing noncommunicable, lifestyle-related diseases. In the past decade, researchers have begun to focus on nurses’ participation in health-promoting activities. The remainder of this article will focus on the research related to nurses and health-promoting behaviors.

Healthy Eating and Physical Activity

Diet and physical activity are perhaps the two health-promoting behaviors that have received the most research attention to date, and they are often researched in tandem. Proper nutrition and physical activity are considered the first line of defense to combat obesity and to prevent cardiovascular disease.12 A sedentary lifestyle can be deadly; risk of mortality from all causes increases proportionately based on the amount of time per day spent sitting.13 Americans have exhibited a long-term pattern of decreasing physical activity, with adults spending approximately 7.7 hours per day (54.9% of time awake) performing sedentary behaviors, most typically watching television or sitting in front of a computer screen.14 Perhaps more alarming, researchers concluded that even if an individual participates in high levels of physical activity, it does not mitigate the effects of prolonged sitting on mortality risk.

The American Heart Association’s recommendations include a minimum of 150 minutes of moderate (or 75 minutes of intense) physical activity per week, in addition to a varied diet high in fruits, vegetables, and whole grains, and low in trans fats and sugar.12 Research suggests that nurses are not necessarily following these guidelines. Tucker et al15 surveyed 3,132 hospital-based RNs and found that only 50% met the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s guidelines for physical activity, and 62% consumed fast food at least twice weekly. In a cross-sectional survey of 325 British nurses, fewer than half (45.98%) met government guidelines for physical activity, and more than half (53.9%) reported consuming foods high in fat and sugar on a daily basis.16 This inactivity comes at a price; a recent literature review found that the prevalence of overweight nurses (ie, nurses with a body mass index [BMI] of 25 to < 30) ranges between 30% to 53%, similar to or higher than the 33.1% prevalence of overweight people in the general population.17 Although 4 of 11 research studies included in this review found obesity rates (BMI ≥ 30) in nurses to be below the national average of 28%, the majority reported obesity levels similar to the general public, and some studies found nurses’ obesity rates as high as 61.4%.17

Stress Management

In addition to poor nutrition and lack of physical activity, the Surgeon General cites stress as another reason for the obesity epidemic in the United States.18 There is considerable evidence that chronic stress is associated with weight gain, abdominal adiposity, and obesity; prolonged stress is associated with binge eating and increased consumption of sugar, fat, and salt.19 The nursing workplace is stressful for several reasons. The high demands and low control often associated with nursing practice and unfavorable work schedules (eg, work overload, shift work, long work hours) all contribute to decreased job satisfaction and increased burnout and stress.4,17,20 Shift work, particularly 12-hour rotating shifts, is associated with increased rates of obesity, smoking, alcohol consumption, physical inactivity, and sleep disturbance.4 Nurses who experience workplace stress are more likely to binge eat and consume more fast foods and fewer fruits and vegetables.21 There is hope, however, because nurses who exercise and get adequate sleep appear to be at less risk for obesity, even when they are required to work unfavorable schedules such as 12-hour night or rotating shifts.22

Sleep Hygiene

The importance of getting adequate amounts of high quality sleep should not be underestimated. In their literature review, Beccuti and Pannain23 reference abundant evidence of a consistent link between shortened sleep duration and obesity. Sleep disturbances, including getting too much or too little sleep, increase the risk of all-cause mortality.24 Sleep is an issue for nurses, particularly those taking overnight call or working 12-hour shifts. Both day- and nightshift hospital nurses working 12-hour shifts report an average of 5.5 hours of sleep per night, with progressively increasing drowsiness for each consecutive shift worked.25 This sleep debt comes at a cost, because sleep is needed for healthy immune system function and memory processing.26 Additionally, sleep deprivation is associated with reduced vigilance and reaction time and cognitive impairments in memory and executive function.27

Healthy Relationships

Diet, exercise, sleep hygiene, and stress reduction are widely accepted as health-promoting behaviors, but the quality of interpersonal relationships also can have a profound influence on health. In a meta-analysis of 145 studies, social isolation was as big a risk factor for all-cause mortality as smoking and alcohol consumption, and isolation had a larger effect on mortality rates than obesity and physical inactivity.28 Social support and isolation in the workplace may be an issue for nurses, partially because bullying is widespread in nursing. Forty-eight percent of a convenience sample of 95 nurses from one state’s professional organization reported having been bullied at work, and 12% reported being bullied several times a week.29 Exacerbated by an underlying culture of silence, workplace bullying can lead to health consequences for the victim, including fatigue, headaches, depression, anxiety, and increased levels of smoking and substance abuse.30

Social ties not only directly relate to mortality risk, but may also predict the level of participation in health-promoting behaviors. In a large-scale study of hospital RNs working in Thailand, nurses’ levels of social support positively predicted exercise participation.31 According to epidemiological data from the Framingham Heart Study, obesity appears to spread through social ties; the odds of becoming obese increase if siblings, spouses, and especially friends are obese.32 The authors concluded that obesity may be contagious partly because of underlying norms. Social support not only influences levels of obesity, but it also plays a key role in success with dieting and weight loss.33 A study by Persson and Mårtensson34 provides evidence of this relationship in nurses. Nightshift nurses reported that their peers influenced their patterns of diet and exercise both positively and negatively. Nurses reported that starting a healthy diet was easier with peer support, but peer pressure to consume junk food or special occasion treats was also present.

BARRIERS TO HEALTH-PROMOTING BEHAVIORS

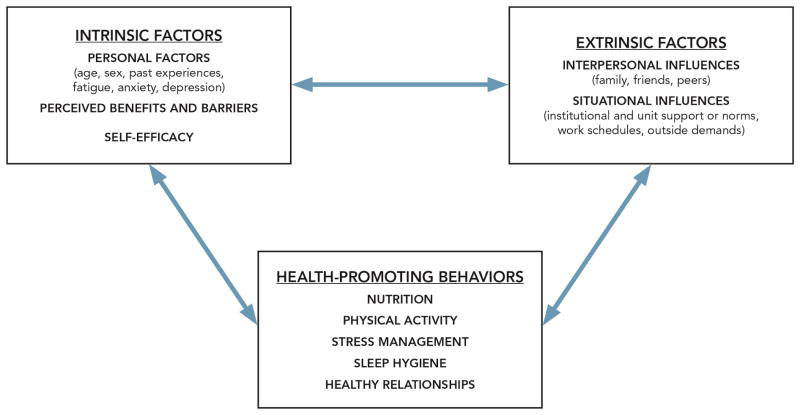

Factors that affect participation in health-promoting behaviors include those that are internal or intrinsic to the individual and those that are environmental or extrinsic (Figure 1). Removing intrinsic and extrinsic barriers and increasing personal motivation are the largest obstacles in health promotion.35 According to Pender’s Model of Health Promotion, intrinsic factors that influence whether one engages in health-promoting activities include personal characteristics and past experiences, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, and self-efficacy; the extrinsic factors include situational and interpersonal influences such as norms, social support, and role modeling.11

Figure 1.

Factors affecting nurses’ participation in health-promoting activities. Model influenced by the work of Seifert CM, Chapman LS, Hart JK, Perez P. Enhancing intrinsic motivation in health promotion and wellness. Am J Health Promot. 2012;26(3):TAHP1-TAHP12 and Pender N, Murdaugh C, Parsons MA. Health Promotion in Nursing Practice. 6th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, Inc; 2011.

Intrinsic characteristics that pose potential barriers to nurses’ participation in health promotion activities include sex and age. One study found that male nurses are more likely to consume a healthy diet and walk while on break than female nurses, and nurses older than 40 years are more likely to take such walks than younger nurses.36 Nurses’ personal beliefs affect their participation in healthy behaviors as well; self-efficacy and the perceived benefits and barriers are related to the frequency of health-promoting behaviors.31,37 Additionally, symptoms such as fatigue,38 depression, and anxiety39 may reduce a nurse’s motivation and participation in health promotion activities.

Research involving nurses reveals several extrinsic barriers to healthy living, including the lack of time and money,38 lack of institutional support,40 and lack of social support.31 Shift work or unhealthy work schedules may also represent barriers.17,22,41 For example, access to healthy foods may be limited for nurses working nights and weekends because cafeterias may be closed and nurses may, out of necessity, rely on vending machines for meals and snacks.42 Nurses who work night shifts report that disruptions in their circadian rhythms affect their ability to exercise and eat a healthy diet.34 Other research supports this, because nurses working the night shift are more likely to eat in response to negative emotions than nurses working the day shift.41 The number of hours worked may also affect health; nurses who work part time are less likely to be overweight or obese.43 The type of unit in which a nurse works may also present barriers. Critical care nurses scored lower than medical-surgical nurses on the Health-Promoting Lifestyle Profile II, which examines physical activity, nutrition, stress management, spirituality, interpersonal relationships, and health responsibility (ie, paying attention to one’s own health, seeking professional assistance).44

Another extrinsic factor that may affect whether a nurse participates in health-promoting behaviors is competing demands from outside the workplace.38,44 In a nationally representative sample of 33,549 RNs, approximately 55% reported having adult or child dependents in their household, and up to 25% reported providing care without the help of a spouse or partner.45 Some nurses may be delivering care to patients at work, then providing care to multiple generations at home. This phenomenon is currently not well researched; however, research in nursing home employees who simultaneously provided care at home to older adult family members or children shows that such “double duty” and “triple duty” caregiving leads to increased stress, exhaustion, and poor psychological functioning.46 Furthermore, according to the National Sample Survey of Registered Nurses, 63.2% of the nation’s estimated 3,063,162 RNs work full time, and 12% of those full-time nurses also work a second job.45

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR NURSE MANAGERS

The health-promoting activities that staff nurses engage in may affect clinical care. For example, nurses who do not exercise or are obese are more likely to suffer from back pain and other musculoskeletal conditions,47,48 potentially affecting their ability to meet the physical demands of their jobs. One study of 1,171 staff nurses revealed a musculoskeletal pain prevalence rate of 71%, with the majority of these nurses (62%) indicating that pain (and depression) led to decreased productivity at work.49 Staff member absences because of an unhealthy nursing workforce may disrupt care, lead to increased workload for the remaining staff members, and potentially compromise patient care.49,50 Thus, nursing leaders should be concerned with improving participation in health-promoting behaviors not only because it is a workplace health issue, but because it is potentially a financial and patient safety issue.

Perioperative nurse leaders might strategically focus their attention on the health-promoting behaviors that appear to be most problematic for nurses, including physical activity and stress reduction. Nurses cite several barriers to these activities, including environmental factors, competing demands, and a lack of time and support.44 These same nurses reported better nutrition, spirituality, and interpersonal relationships, perhaps because nurses can more easily incorporate these activities into the workday.

Workplace interventions for nurses that target physical activity, stress reduction, and diet can be successful.51–53 Workplace health initiatives do not have to be expensive or time-consuming. One such program, Nurses Living Fit, incorporated 12 weekly exercise classes and information related to a healthy lifestyle such as nutrition, yoga for stress, and sleep. This program was effective in reducing the BMIs of overweight nurses.54 Unfortunately, the effects of the program on BMI did not continue after the 12-week intervention ended, which emphasizes that health-promoting interventions should be ongoing, permanent components in the nursing workplace and not just limited-time events.

Nurse leaders may want to consider workplace health programs that are holistic in nature; these programs are effective in reducing stress and burnout and appear to hold particular appeal to nurses.55,56 Both mindfulness-based stress reduction interventions and weekly yoga classes can be helpful in improving self-care and reducing burnout in nurses.56,57

Health-promoting activities that can be incorporated into the workplace are essential and should be activities that staff members can perform during the workday or immediately before or after their shifts. The American Nurses Association created an informational web site called HealthyNurse that provides comprehensive health and safety information specifically for nurses,58 along with a link to a health-risk appraisal.59 At a minimum, nurse leaders should make information about healthy lifestyles available to staff nurses; ideally, nurse leaders will actively encourage and model healthy behaviors for their nursing workforce (Table 1).

Table 1.

Tips for Nurse Leaders to Increase Health-Promoting Behaviors in Nurses

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Nurse Leaders as Role Models and Advocates for Change

Nurse leaders should recognize the power of social support and the hospital or unit culture on a nurse’s ability to practice health-promoting behaviors. Nurse leaders can support and promote nurses’ efforts to eat a healthy diet or to exercise. If the culture of the unit is to celebrate every birthday or milestone with high-sugar, high-fat treats, leaders might consider other forms of recognition, such as flowers, a fruit tray, or a healthy lunch. When making staffing decisions, leaders should ensure that there is adequate support for nurses who want or need to turn off their cell phones or pagers or leave the unit for meals or a relaxation break. If access to exercise facilities, outdoor spaces, or a quiet room for meditation does not already exist at the facility, leaders could rally support to provide these services. Perhaps most importantly, leaders can work to create an open environment in which nurses feel comfortable discussing workplace stressors and barriers to healthy behaviors.

Effective nurse leaders encourage healthy work relationships and can serve as role models for health promotion. Nurse leaders should examine their own nutritional, exercise, stress reduction, and sleep patterns, and their own implementation of work-life balance. They can set examples by exercising regularly, engaging in stress reduction activities, taking the time to mindfully prepare their own healthy meals, and spending time with family and friends. Leaders may talk about the importance of healthy lifestyles, but when they repeatedly work long hours, eat on the run, and send e-mails late at night or on weekends, they are sending conflicting messages. One of the most important things that nurse leaders can do is maintain their own health and well-being, thereby encouraging staff members to do the same.

Nurse leaders can become advocates for system changes. Leaders can advocate for the cafeteria and vending machines to offer healthy foods and request a convenient place for staff members to eat outside. Because nurses themselves are best able to identify needed programs and workplace barriers to healthy living, leaders could perform a needs assessment or hold focus groups to determine how the organization or unit can best encourage and support healthy lifestyles. Incorporating healthy behaviors into the nursing workplace is an investment that not only can provide immediate dividends for the staff nurses, but long-term benefits for the organization and patients as well. Returning to our case study, consider how Ms. Y’s work life might improve if her OR manager worked to foster a healthy work environment.

CASE STUDY: IMPLEMENTING A SOLUTION

Ms Y’s nurse manager, Mr S, recently has noticed that the strain of a heavy OR schedule and budget cuts have taken a toll on the OR nursing staff members, particularly the more senior staff members, many of whom are responsible for training new staff members while working additional overtime hours. Morale is at an all-time low and absenteeism is up, overwhelming an already tense workforce. Although he cannot change the hospital’s finances, he realizes that he needs to make significant changes to increase staff morale and resiliency. Through a strong shared-governance structure, Mr S requests staff member guidance to develop a quality improvement pilot geared at improving the health and well-being of the OR staff members. He requests the budget to support this initiative through the office of recruitment and retention and the office of the Chief Nurse. Through a series of meetings, staff members enthusiastically design a proposal for a workplace wellness initiative that includes three wellness goals:

improved nutrition,

increased physical strength and flexibility training, and

stress reduction.

Staff members currently are prioritizing these goals and developing timelines and an evaluation plan under the guidance of the OR manager, the Chief Nurse, and senior hospital administrators. Morale has already improved.

CONCLUSION

Despite nurses’ knowledge of the importance of healthy behaviors, this knowledge does not always translate into self-care. The consequences of an unhealthy workforce can adversely affect nurses’ morale, productivity, and ultimately, patient care. Nurse leaders can serve as role models for healthy lifestyles, and they can support staff nurses’ health by encouraging nurses’ efforts to exercise, consume a healthy diet, reduce stress, and improve interpersonal relationships. Furthermore, nurse leaders can become advocates for system change by identifying and working to remove workplace barriers that discourage or prevent nurses from engaging in healthy behaviors.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Clinical Center, Bethesda, MD. The Office of Human Subjects Research Protections at the NIH Clinical Center approved this study.

Biographies

Alyson Ross, PhD, RN, is a nurse investigator in Nursing Research and Translational Science, Nursing Department, National Institutes of Health (NIH) Clinical Center, Bethesda, MD. Dr Ross has no declared affiliation that could be perceived as posing a potential conflict of interest in the publication of this article.

Margaret Bevans, PhD, RN, AOCN, FAAN, is a captain in the United States Public Health Service and a clinical nurse scientist and program director in Nursing Research and Translational Science, Nursing Department, NIH Clinical Center, Bethesda, MD. Dr Bevans has no declared affiliation that could be perceived as posing a potential conflict of interest in the publication of this article.

Alyssa T. Brooks, PhD, is a postdoctoral fellow in Nursing Research and Translational Science, Nursing Department, NIH Clinical Center, Bethesda, MD. Dr Brooks has no declared affiliation that could be perceived as posing a potential conflict of interest in the publication of this article.

Susanne Gibbons, PhD, AGPCNP-BC, is an assistant professor at the Daniel K. Inouye Graduate School of Nursing at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, MD. Dr Gibbons has no declared affiliation that could be perceived as posing a potential conflict of interest in the publication of this article.

Gwenyth R. Wallen, PhD, RN, is the deputy chief nurse of Research and Practice Development, the chief of Nursing Research and Translational Science, and the chief nurse officer (acting) of the NIH Clinical Center, Bethesda, MD. Dr Wallen has no declared affiliation that could be perceived as posing a potential conflict of interest in the publication of this article.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Alyson Ross, Nurse Investigator, National Institutes of Health (NIH) Clinical Center, Nursing Research and Translational Science, Nursing Department, 10 Center Drive, Room 2B07, Bethesda, MD 20892.

Margaret Bevans, CAPT, United States Public Health Service; Clinical Nurse Scientist; Program Director, Scientific Resources, NIH Clinical Center, Nursing Research and Translational Science, Nursing Department, 10 Center Drive, Room 2B13, MSC 1151, Bethesda, MD 20892, Contact telephone: (301) 402-9383.

Alyssa T. Brooks, Post-doctoral Fellow, NIH Clinical Center, Nursing Research and Translational Science, Nursing Department, 10 Center Drive, Bethesda, MD 20892, Contact telephone: (301) 496-5805.

Susanne Gibbons, Assistant Professor, Daniel K. Inouye Graduate School of Nursing, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, 4301 Jones Bridge Road, Building E, Room 2039, Bethesda, MD 20814, Contact telephone: (301) 295-1350.

Gwenyth R. Wallen, Chief Nurse Officer (Acting), Deputy Chief Nurse, Research and Practice Development, Chief, Nursing Research and Translational Science, NIH Clinical Center, 10 Center Drive, Room 2B13, MSC 1151, Bethesda, MD 20892, Contact telephone: (301) 496-0596.

References

- 1.Jones DS, Podolsky SH, Greene JA. The burden of disease and the changing task of medicine. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(25):2333–2338. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1113569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nurses rank as most honest, ethical profession for 14th straight year. American Nurses Association; [Accessed October 28, 2016]. http://www.nursingworld.org/2015-NursesRankedMostHonestEthicalProfession. Published December 21, 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Women’s Health Study. [Accessed October 28, 2016];Harvard Medical School, Brigham and Women’s Hospital. http://whs.bwh.harvard.edu/index.html.

- 4.Caruso CC. Negative impacts of shiftwork and long work hours. Rehabil Nurs. 2014;39(1):16–25. doi: 10.1002/rnj.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Committee on Health and Behavior: Research, Practice, and Policy; Board on Neuroscience and Behavioral Health; Institute of Medicine. Health and Behavior: The Interplay of Biological, Behavioral, and Societal Influences. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chandrakumar S, Adams J. Attitudes to smoking and smoking cessation among nurses. Nurs Stand. 2015;30(9):36–40. doi: 10.7748/ns.30.9.36.s44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Monroe T, Kenaga H. Don’t ask don’t tell: substance abuse and addiction among nurses. J Clin Nurs. 2011;20(3–4):504–509. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03518.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steptoe A, Wardle J. Health-related behaviour: prevalence and links with disease. In: Kaptein A, Weinman J, editors. Health Pscyhology. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing; 2004. pp. 21–51. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Su SY, Chiou ST, Huang N, Huang CM, Chiang JH, Chien LY. Association between Pap smear screening and job stress in Taiwanese nurses. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2016 Feb;20:119–124. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2015.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Silva IT, Griep RH, Rotenberg L. Social support and cervical and breast cancer screening practices among nurses. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2009;17(4):514–521. doi: 10.1590/s0104-11692009000400013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pender N, Murdaugh C, Parsons MA. Health Promotion in Nursing Practice. 6. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, Inc; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 12.The American Heart Association’s diet and lifestyle recommendations. American Heart Association; [Accessed October 28, 2016]. http://www.heart.org/HEARTORG/HealthyLiving/HealthyEating/Nutrition/The-American-Heart-Associations-Diet-and-Lifestyle-Recommendations_UCM_305855_Article.jsp. Reviewed August 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rezende LF, Sá TH, Mielke GI, Viscondi JY, Rey-López JP, Garcia LM. All-cause mortality attributable to sitting time: analysis of 54 countries worldwide. Am J Prev Med. 2016;51(2):253–263. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matthews CE, George SM, Moore SC, et al. Amount of time spent in sedentary behaviors and cause-specific mortality in US adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;95(2):437–445. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.019620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tucker SJ, Harris MR, Pipe TB, Stevens SR. Nurses’ ratings of their health and professional work environments. AAOHN J. 2010;58(6):253–267. doi: 10.3928/08910162-20100526-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blake H, Malik S, Mo PK, Pisano C. ‘Do as I say, but not as I do’: are next generation nurses role models for health? Perspect Public Health. 2011;131(5):231–239. doi: 10.1177/1757913911402547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buss J. Associations between obesity and stress and shift work among nurses. Workplace Health Saf. 2012;60(10):453–458. 459. doi: 10.1177/216507991206001007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.US Department of Health and Human Services. The Surgeon General’s Vision for a Healthy and Fit Nation. Rockville, MD: Office of the Surgeon General; 2010. [Accessed October 28, 2016]. http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/priorities/healthy-fit-nation/obesityvision2010.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sinha R, Jastreboff AM. Stress as a common risk factor for obesity and addiction. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;73(9):827–835. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.01.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khamisa N, Peltzer K, Oldenburg B. Burnout in relation to specific contributing factors and health outcomes among nurses: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2013;10(6):2214–2240. doi: 10.3390/ijerph10062214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Almajwal AM. Stress, shift duty, and eating behavior among nurses in Central Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2016;37(2):191–198. doi: 10.15537/smj.2016.2.13060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Han K, Trinkoff AM, Storr CL, Geiger-Brown J, Johnson KL, Park S. Comparison of job stress and obesity in nurses with favorable and unfavorable work schedules. J Occup Environ Med. 2012;54(8):928–932. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e31825b1bfc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beccuti G, Pannain S. Sleep and obesity. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2011;14(4):402–412. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e3283479109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gallicchio L, Kalesan B. Sleep duration and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sleep Res. 2009;18(2):148–158. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2008.00732.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Geiger-Brown J, Rogers VE, Trinkoff AM, Kane RL, Bausell RB, Scharf SM. Sleep, sleepiness, fatigue, and performance of 12-hour-shift nurses. Chronobiol Int. 2012;29(2):211–219. doi: 10.3109/07420528.2011.645752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brown RE, Basheer R, McKenna JT, Strecker RE, McCarley RW. Control of sleep and wakefulness. Physiol Rev. 2012;92(3):1087–1187. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00032.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fortier-Brochu E, Beaulieu-Bonneau S, Ivers H, Morin CM. Insomnia and daytime cognitive performance: a meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2012;16(1):83–94. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Layton JB. Social relationships and mortality risk: a meta-analytic review. PLoS Med. 2010;7(7):e1000316. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Etienne E. Exploring workplace bullying in nursing. Workplace Health Saf. 2014;62(1):6–11. doi: 10.1177/216507991406200102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vessey JA, DeMarco R, DiFazio R. Bullying, harassment, and horizontal violence in the nursing workforce: the state of the science. Annu Rev Nurs Res. 2010;28(1):133–157. doi: 10.1891/0739-6686.28.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaewthummanukul T, Brown KC, Weaver MT, Thomas RR. Predictors of exercise participation in female hospital nurses. J Adv Nurs. 2006;54(6):663–675. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03854.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Christakis NA, Fowler JH. The spread of obesity in a large social network over 32 years. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(4):370–379. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa066082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kiernan M, Moore SD, Schoffman DE, et al. Social support for healthy behaviors: scale psychometrics and prediction of weight loss among women in a behavioral program. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2012;20(4):756–764. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Persson M, Mårtensson J. Situations influencing habits in diet and exercise among nurses working night shift. J Nurs Manag. 2006;14(5):414–423. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2934.2006.00601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Seifert CM, Chapman LS, Hart JK, Perez P. Enhancing intrinsic motivation in health promotion and wellness. Am J Health Promot. 2012;26(3):TAHP1–TAHP12. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.26.3.tahp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zapka JM, Lemon SC, Magner RP, Hale J. Lifestyle behaviours and weight among hospital-based nurses. J Nurs Manag. 2009;17(7):853–860. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2008.00923.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Esposito EM, Fitzpatrick JJ. Registered nurses’ beliefs of the benefits of exercise, their exercise behaviour and their patient teaching regarding exercise. Int J Nurs Pract. 2011;17(4):351–356. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-172X.2011.01951.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bryer J, Cherkis F, Raman J. Health-promotion behaviors of undergraduate nursing students: a survey analysis. Nurs Educ Perspect. 2013;34(6):410–415. doi: 10.5480/11-614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Melnyk BM, Hrabe DP, Szalacha LA. Relationships among work stress, job satisfaction, mental health, and healthy lifestyle behaviors in new graduate nurses attending the nurse athlete program: a call to action for nursing leaders. Nurs Adm Q. 2013;37(4):278–285. doi: 10.1097/NAQ.0b013e3182a2f963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Phiri LP, Draper CE, Lambert EV, Kolbe-Alexander TL. Nurses’ lifestyle behaviours, health priorities and barriers to living a healthy lifestyle: a qualitative descriptive study. BMC Nurs. 2014;13(1):38. doi: 10.1186/s12912-014-0038-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wong H, Wong MC, Wong SY, Lee A. The association between shift duty and abnormal eating behavior among nurses working in a major hospital: a cross-sectional study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2010;47(8):1021–1027. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Faugier J, Lancaster J, Pickles D, Dobson K. Barriers to healthy eating in the nursing profession: part 1. Nurs Stand. 2001;15(36):33–36. doi: 10.7748/ns2001.05.15.36.33.c3030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bogossian FE, Hepworth J, Leong GM, et al. A cross-sectional analysis of patterns of obesity in a cohort of working nurses and midwives in Australia, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom. Int J Nurs Stud. 2012;49(6):727–738. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McElligott D, Siemers S, Thomas L, Kohn N. Health promotion in nurses: is there a healthy nurse in the house? Appl Nurs Res. 2009;22(3):211–215. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2007.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.US Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration. [Accessed November 23, 2016];The Registered Nurse Population: Findings From the 2008 National Sample Survey of Registered Nurses. http://bhw.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/bhw/nchwa/rnsurveyfinal.pdf. Published September 2010.

- 46.DePasquale N, Davis KD, Zarit SH, Moen P, Hammer LB, Almeida DM. Combining formal and informal caregiving roles: the psychosocial implications of double- and triple-duty care. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2016;71(2):201–211. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbu139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhao I, Bogossian F, Turner C. The effects of shift work and interaction between shift work and overweight/obesity on low back pain in nurses: results from a longitudinal study. J Occup Environ Med. 2012;54(7):820–825. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e3182572e6a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vieira ER, Kumar S, Narayan Y. Smoking, no-exercise, overweight and low back disorder in welders and nurses. Int J Ind Ergon. 2008;38(2):143–149. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Letvak SA, Ruhm CJ, Gupta SN. Nurses’ presenteeism and its effects on self-reported quality of care and costs. Am J Nurs. 2012;112(2):30–38. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000411176.15696.f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.While AE. Promoting healthy behaviours – do we need to practice what we preach? London J Prim Care (Abingdon) 2015;7(6):112–114. doi: 10.1080/17571472.2015.1113716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Palumbo MV, Wu G, Shaner-McRae H, Rambur B, McIntosh B. Tai Chi for older nurses: a workplace wellness pilot study. Appl Nurs Res. 2012;25(1):54–59. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Torquati L, Pavey T, Kolbe-Alexander T, Leveritt M. Promoting diet and physical activity in nurses: a systematic review [published online ahead of print September 21, 2015] Am J Health Promot. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.141107-LIT-562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chan CW, Perry L. Lifestyle health promotion interventions for the nursing workforce: a systematic review. J Clin Nurs. 2012;21(15–16):2247–2261. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2012.04213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Speroni KG, Earley C, Seibert D, et al. Effect of Nurses Living Fit exercise and nutrition intervention on body mass index in nurses. J Nurs Adm. 2012;42(4):231–238. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0b013e31824cce4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McElligott D, Capitulo KL, Morris DL, Click ER. The effect of a holistic program on health-promoting behaviors in hospital registered nurses. J Holist Nurs. 2010;28(3):175–183. doi: 10.1177/0898010110368860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Alexander GK, Rollins K, Walker D, Wong L, Pennings J. Yoga for self-care and burnout prevention among nurses. Workplace Health Saf. 2015;63(10):462–470. doi: 10.1177/2165079915596102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cohen-Katz J, Wiley SD, Capuano T, Baker DM, Shapiro S. The effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on nurse stress and burnout: a quantitative and qualitative study. Holist Nurs Pract. 2004;18(6):302–308. doi: 10.1097/00004650-200411000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Healthy Nurse, Healthy Nation. American Nurses Association; [Accessed October 28, 2016]. http://www.nursingworld.org/MainMenuCategories/WorkplaceSafety/Healthy-Nurse. [Google Scholar]

- 59. [Accessed October 28, 2016];Welcome to ANA’s HealthyNurse Health Risk Appraisal (HRA) http://www.anahra.org/