Abstract

Protein bioconjugation has been a crucial tool for studying biological processes and developing therapeutics. Sortase A (SrtA), a bacterial transpeptidase, has become widely used for its ability to site-specifically label proteins with diverse functional moieties, but a significant limitation is its poor reaction kinetics. In this work, we address this by developing proximity-based sortase-mediated ligation (PBSL), which improves the ligation efficiency to >95% by linking the target protein to SrtA using the SpyTag-SpyCatcher peptide-protein pair. By expressing the target protein with SpyTag C-terminal to the SrtA recognition motif, it can be covalently captured by an immobilized SpyCatcher-SrtA fusion protein during purification. Following the ligation reaction, SpyTag is cleaved off, rendering PBSL traceless, and only the labeled protein is released, simplifying target protein purification and labeling to a single step.

Keywords: bioconjugation, expressed protein ligation, protein engineering, protein modifications, sortase

Proximity-based labelling

The poor reaction kinetics of sortase A, a bacterial transpeptidase, has been a significant limitation for its use in site-specific protein bioconjugation. Proximity-based sortase-mediated ligation (PBSL) improves ligation efficiency by bringing target proteins in proximity to SrtA with the SpyTag-SpyCatcher peptide-protein pair and allows for protein purification and labelling to be simplified to a single step.

The ability to modify proteins with diverse chemical groups has been important for both understanding protein biology as well as engineering protein therapeutics.[1] Site-specific bioconjugation techniques are especially valuable because they produce more homogeneously labeled samples, important for many applications such as the production of antibody-drug conjugates.[2] Sortase A (SrtA), a bacterial transpeptidase, has become widely used for installing site-specific modifications since it only requires target proteins to have a short LPXTG recognition motif (for Staph. aureas SrtA).[3] In the presence of Ca2+, SrtA binds to its recognition motif and its catalytic Cys cleaves between the Thr and Gly to form a thioester acyl-enzyme intermediate, which is resolved most commonly by nucleophilic attack from a peptide with a N-terminal oligoglycine causing release of the ligated protein.[4] Due to the synthetic accessibility of peptides linked to chemical groups (e.g. imaging agents, drugs, etc.) and SrtA's broad nucleophile scope, SrtA has been used to conjugate proteins to not only peptides, but also other proteins,[5] lipids,[6] sugars,[7] nucleic acids,[8] polymers,[9] and surfaces.[10] Additionally, noncanonical SrtA labeling sites have been identified and can be exploited to label proteins at multiple sites in an orthogonal manner.[11]

One major limitation of SrtA, though, is its low binding affinity for its recognition motif (Km>7.3mM) and poor reaction kinetics, resulting in long reaction times and poor yields.[5,9,12-13] Using a large molar excess of both SrtA and the nucleophilic peptide can improve these parameters,[14] but can be cost-prohibitive for custom-synthesized peptides. Directed evolution has been used to engineer faster SrtA variants,[12] but they also have reduced ligation efficiency due to increased rates of the hydrolysis side-reaction.[15] We have previously addressed this limitation by developing sortase-tag expressed protein ligation (STEPL), which expresses the target protein in series with both the SrtA recognition motif and SrtA.[16] By linking the target protein to SrtA, its effective concentration in the subsequent intramolecular ligation reaction is significantly increased, accelerating ligation rates by overcoming SrtA's low recognition motif binding affinity. However, we have found that not only do some proteins poorly express once linked to SrtA, but also that protein-SrtA fusions that do express can in rare instances be catalytically inactive, which limits STEPL's generality.

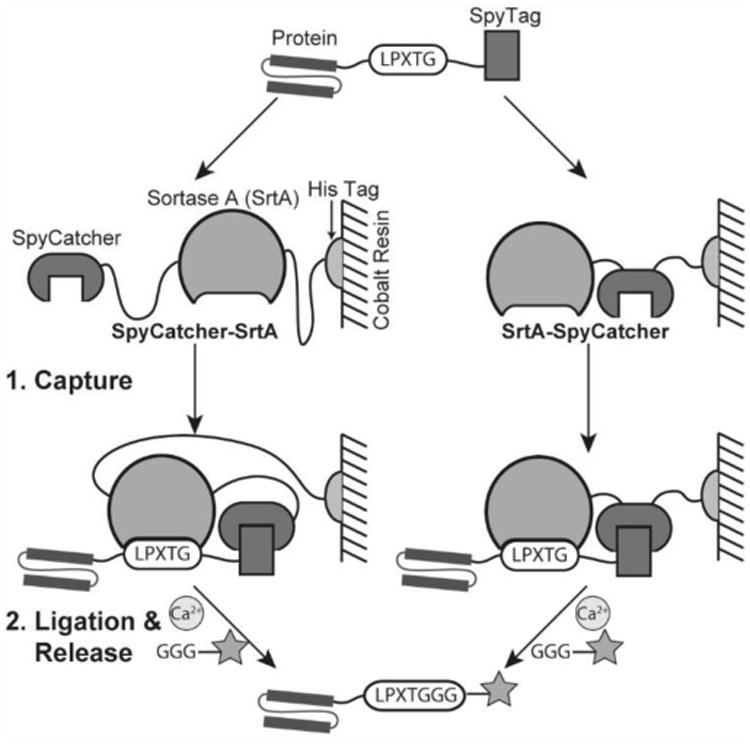

In this work, we describe a new ligation strategy, proximity-based sortase-mediated ligation (PBSL), in which the target protein is expressed separately from SrtA, but still allows for an intramolecular ligation reaction. The target protein is expressed with a C-terminal LPETG SrtA recognition motif linked to SpyTag via a flexible (GGS)5 linker. SpyTag is a short peptide (13aa) that upon incubation with SpyCatcher, its partner protein, will rapidly form an irreversible isopeptide bond.[17] Thus, a SrtA and SpyCatcher fusion protein immobilized on an affinity resin can first capture the target protein before initiating the ligation reaction with the addition of Ca2+ and a peptide with a N-terminal GGG (Scheme 1). By separating SrtA and target protein expression, PBSL retains the advantages of STEPL without any of the drawbacks associated with expression. Furthermore, since only labeled protein is released from the resin, PBSL simplifies purification, ligation, and enzyme removal to a single step. Significant efforts have been made just to increase the ease of removing SrtA following ligation.[18] Both SpyCatcher-SrtA and SrtA-SpyCatcher were tested to determine whether fusion protein orientation affected PBSL effectiveness.

Scheme 1.

PBSL overview. The target protein is expressed with a C-terminal LPXTG SrtA recognition motif linked to SpyTag. It is captured during purification by a SpyCatcher-SrtA fusion protein immobilized on cobalt resin. Addition of Ca2+ and a peptide with a N-terminal GGG triggers ligation and release of the labeled protein.

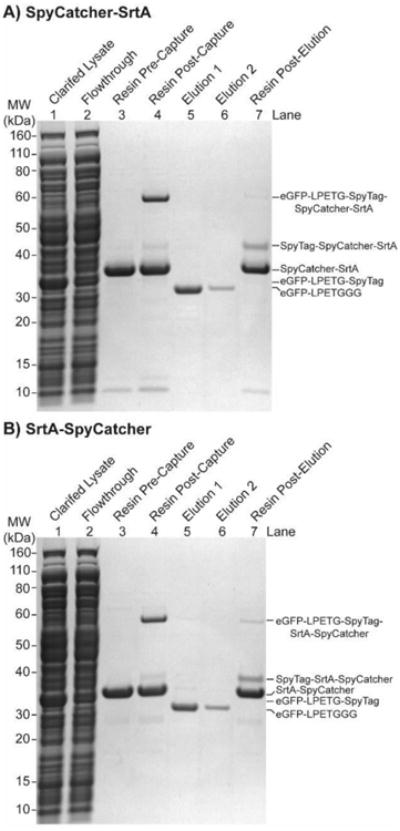

We used eGFP to characterize PBSL since its concentration can be tracked by measuring absorbance at 488nm (ε = 56,000 M-1cm-1).[19] By SDS-PAGE, both SpyCatcher-SrtA and SrtA-SpyCatcher resins captured expressed eGFP-LPETG-SpyTag from clarified lysates (Fig. 1 Lanes 1 vs 2), resulting in eGFP-LPETG-SpyTag covalently linked to the SpyCatcher and SrtA fusion protein on the resin (Fig.1 Lanes 3 vs 4). Nearly all captured eGFP was released following a 3 hour 37°C ligation reaction with 2mM triglycine (GGG) (Fig. 1 Lanes 4-7).

Figure 1.

SDS-PAGE of PBSL. Following a 30 min incubation, most of the eGFP-LPETG-SpyTag clarified lysates was captured with either a) SpyCatcher-SrtA or b) SrtA-SpyCatcher resin. Release of almost all captured protein is achieved with a 3h ligation reaction with 2mM GGG in reaction buffer (PBS + 50μM CaCl2, pH 7.4) at 37°C.

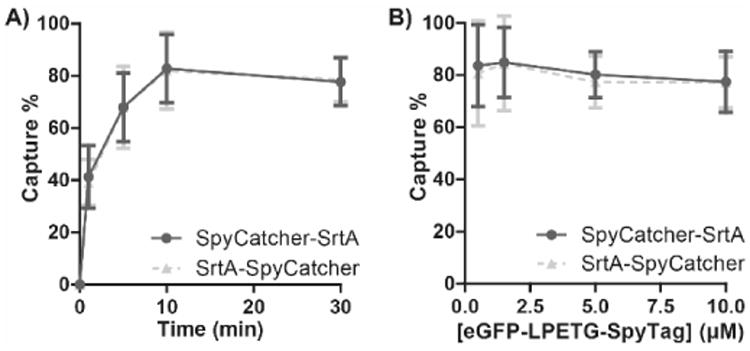

To quantify capture efficiency, we incubated 10μM eGFP-LPETG-SpyTag clarified lysates with 4 molar equivalents of either SpyCatcher-SrtA or SrtA-SpyCatcher resin for varying times. ∼80% capture was achieved with both resins within 10 min, consistent with previously reported SpyTag-SpyCatcher reaction rates (Fig.2a).[17] The ∼80% capture efficiency was maintained even with 0.5μM eGFP-LPETG-SpyTag lysates, demonstrating that PBSL is compatible with poorly expressed proteins as well (Fig.2b). Just SpyTag-SpyCatcher binding has a Kd of 0.2μM,[17] suggesting that target proteins expressed at even lower concentrations may still be efficiently captured. Finally, both resins remained stable when stored at 4°C out to 2 months with no decrease in capture efficiency (Fig.S1a).

Figure 2.

PBSL capture efficiency. a) 10μM eGFP-LPETG-SpyTag clarified lysates were incubated with either SpyCatcher-SrtA or SrtA-SpyCatcher resin for varying times. Approximately 80% capture occurred within 10 min for both resins. b) Varying concentrations of eGFP-LPETG-SpyTag clarified lysates were incubated with either resins for 30 min. ∼80% maximal capture was retained for lysate concentrations as low as 0.5μM. Captured [eGFP-LPETG-SpyTag] were determined by incubating the resin with stripping buffer (PBS + 200mM imidazole, pH 7.4) and measuring eGFP absorbance at 488nm. Data are mean ± SD; n=3.

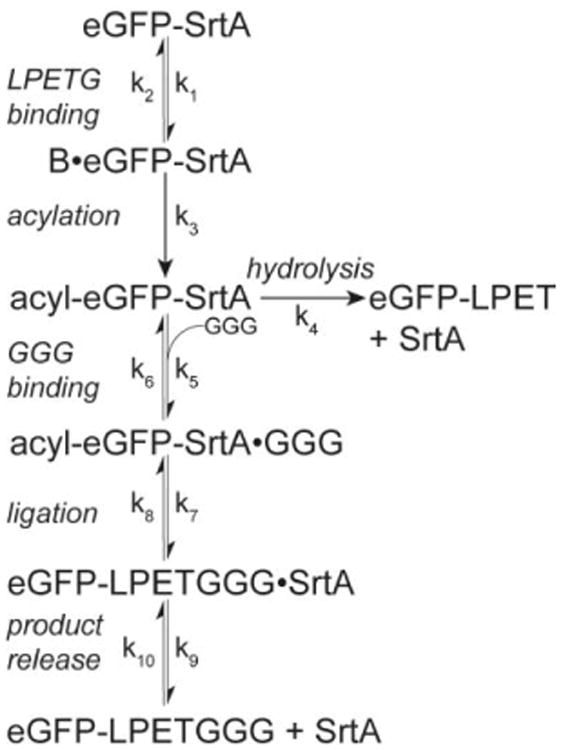

Next, we monitored eGFP release by performing the ligation reaction with ∼5μM eGFP-LPETG-SpyTag captured on either SpyCatcher-SrtA or SrtA-SpyCatcher resins with varying [GGG]. As expected, higher [GGG] increased release rates for both resins (Fig.3a & 3c, symbols). Interestingly, the hydrolysis side-reaction, which is the only reaction with the 0μM GGG condition, was slightly faster for SrtA-SpyCatcher. To determine ligation efficiency, the release data was fit to a model in which eGFP-SrtA first undergoes an intramolecular acylation reaction followed by either a reversible ligation reaction or an irreversible hydrolysis side-reaction reaction (Scheme 2).[20] This model is similar to the ping-pong bi-bi hydrolytic shunt kinetic mechanism proposed for SrtA alone,[13] except that the acylation reaction is intramolecular. As shown in Figure 2, the model provides an excellent fit to the observed data (Fig.3a & 3c, lines).

Figure 3.

PBSL release yields and predicted ligation efficiency. Yields for eGFP release from a) SpyCatcher-SrtA or c) SrtA-SpyCatcher resin was monitored over time following incubation with reaction buffer and varying [GGG] (symbols). [eGFP]released was determined by measuring absorbance at 488nm whereas [eGFP]captured was determined as the sum of [eGFP]released and [eGFP]stripped. Data are mean ± SD; n=3. Release yields were fitted to the model in Scheme 2 and superimposed (lines) onto the data. Ligation efficiency for b) SpyCatcher-SrtA and d) SrtA-SpyCatcher and varying [GGG] was then calculated. The dashed line indicates 95% ligation efficiency.

Scheme 2.

Model of eGFP release. An initial intramolecular acylation reaction is followed by either a reversible, GGG-dependent ligation reaction or an irreversible hydrolysis side-reaction.

The model predicts that the ligation efficiency for both resins is excellent with 200μM and 2mM GGG, but poor for 20μM GGG. SpyCatcher-SrtA has a slightly higher predicted efficiency due to its lower base hydrolysis rate (Fig.3b & 3d). The poor 20μM GGG ligation efficiency is likely due to a greater relative contribution from the reverse ligation reaction compared to that of the forward reaction. Furthermore, since the hydrolysis reaction is irreversible, ligation efficiency is predicted to slowly decrease over time. Thus, optimal reaction times require a compromise between maximizing product release and product purity. Although both issues could potentially be addressed by incrementally removing released eGFP, adopting a flow-based reaction system,[21] or using a nucleophile incompatible with the reverse ligation reaction,[22] PBSL still results in excellent ligation yields and efficiency. When peptide cost is not a concern, a 3h 37°C reaction with 2mM peptide results in ∼95% release for SpyCatcher-SrtA and ∼96% release for SrtA-SpyCatcher with a >99% predicted ligation efficiency for both. For 200μM reactions, which is more economical, a 4h 37°C reaction is recommended, which offers a balance between high release (∼87% for SpyCatcher-SrtA and ∼89% for SrtA-SpyCatcher) and high predicted ligation efficiency (∼98% for SpyCatcher-SrtA and ∼97% for SrtA-SpyCatcher). Actual ligation efficiency, though, may be higher as no hydrolysis product could be detected by MALDI-TOF when eGFP was labeled with 200μM GGG-TAMRA for 4h at 37°C (Fig.S2). Finally, both resins remained stable with no decrease in eGFP release (Fig.S1b).

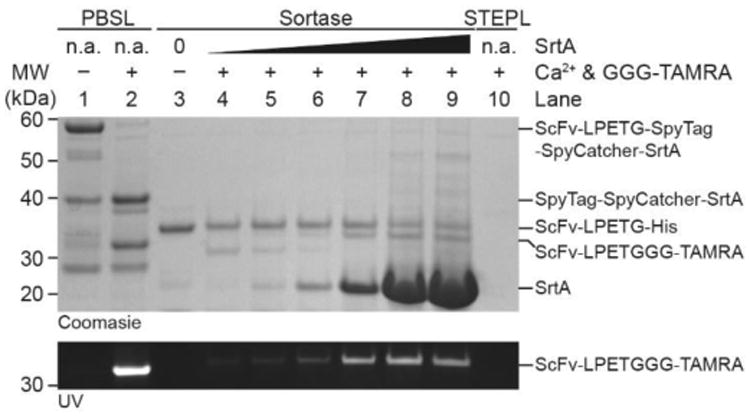

To directly compare labeling yields for PBSL against STEPL and traditional sortase ligation, we attempted to label an anti-CD3 ScFv, which is commonly used for therapeutics and in immunology research, with a fluorescent GGG-TAMRA peptide. For traditional sortase ligation, ScFv-LPETG-His was incubated with increasing molar ratios of SrtA (up to 100:1 SrtA:ScFv) and 200μM GGG-TAMRA. By SDS-PAGE, successful ligation was detected by a downward shift in the ScFv band, which also fluoresced under UV (Fig.4 Lanes 3-9). Even with enormous excess of SrtA, significant amounts of the ScFv remain unlabeled, consistent with previous reports of SrtA ligation efficiency.[5] The ScFv was incompatible with STEPL and no labeled protein could be purified (Fig.4 Lane 10) due to poor expression once linked to SrtA. Finally, with PBSL, ScFv-LPETG-SpyTag captured on SpyCatcher-SrtA resin was stripped and labeled in solution with GGG-TAMRA under the same conditions as that of traditional sortase ligation. The reaction was performed in solution to ensure that the same starting amount of unlabeled ScFv was used between PBSL and traditional SrtA ligation. There are no significant differences in reactivity between PBSL in solution and on resin (Fig.S3). As expected, the ligation reaction resulted in ScFv release from SpyCatcher-SrtA and the formation of SpyTag-SpyCatcher-SrtA as well as a fluorescent ScFv-LPETGGG-TAMRA product (Fig.4 Lanes 1-2). Consistent with the eGFP studies, little to no ScFv remained captured following the ligation (Fig.4 Lane 2) in contrast with the large amounts of unlabeled ScFv remaining with traditional sortase ligation. The labeled ScFv product obtained from PBSL on resin was of high purity and without any hydrolysis side-products as detected by MALDI-TOF (Fig.S4). Quantification of TAMRA fluorescence shows that PBSL labeled ∼2.5 times more ScFv than traditional sortase ligation (Fig. 4 UV image, Fig.S5), demonstrating the superiority of PBSL. Finally, kinetic comparisons between PBSL and traditional sortase ligation show that PBSL results in faster reaction times by increasing the effective concentration of the target protein by more than 100 fold (Fig.S6).

Figure 4.

SDS-PAGE comparing PBSL (Lanes 1-2) with traditional sortase ligation (Lanes 3-9) and STEPL (Lane 10). Following ligation with either PBSL in solution or sortase, a fluorescent band corresponding to the ScFv-LPETGGG-TAMRA product appears. PBSL results in significantly more fluorescently labeled product than either SrtA or STEPL. Traditional sortase ligation was carried out with SrtA:ScFv molar ratios ranging from 1:1 to 100:1. The ScFv-LPETGGG-TAMRA product for traditional sortase ligation runs slightly higher than that of PBSL due to a longer linker between the ScFv and the LPETG SrtA recognition motif.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that PBSL is a new SrtA ligation strategy with faster reaction times and greater efficiency than that of WT SrtA alone. This method only requires an additional 28 amino acids (2.5 kDa) to be expressed C-terminal to the SrtA recognition motif which should minimally perturb target protein expression and folding. Furthermore, PBSL is traceless since both SpyTag and the linker remain with SpyCatcher following protein release. Although the resin cannot be regenerated, SpyCatcher and SrtA fusion proteins can be easily purified in large quantities from E. coli. (∼80-100 mg L-1 culture) allowing for mg scale purification and labeling of target proteins (∼20-25mg labeled protein per L of SpyCatcher and SrtA culture). By separating target protein and SrtA expression, PBSL is compatible with target proteins that require expression environments containing high concentrations of Ca2+ such as yeast or mammalian system. Finally, we anticipate that using SpyTag and SpyCatcher to link substrate proteins to labeling enzymes could be applied to other enzymatic bioconjugation strategies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grants U01-EB016027 (NIBIB), R01-CA181429 (NCI), R21-CA187657 (NCI), and R21-EB018863 (NIBIB).

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is given via a link at the end of the document

Contributor Information

Hejia Henry Wang, Department of Biochemistry and Biophysics, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104 (USA).

Dr. Burcin Altun, Department of Bioengineering, University of Pennsylvania, 210 S. 33rd Street, 240 Skirkanich Hall, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104, (USA).

Dr. Kido Nwe, Department of Bioengineering, University of Pennsylvania, 210 S. 33rd Street, 240 Skirkanich Hall, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104, (USA)

Prof. Andrew Tsourkas, Department of Bioengineering, University of Pennsylvania, 210 S. 33rd Street, 240 Skirkanich Hall, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104, (USA)

References

- 1.a) Krall N, da Cruz FP, Boutureira O, Bernardes GJL. Nat Chem. 2016;8:103. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Sletten EM, Bertozzi CR. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:6974. doi: 10.1002/anie.200900942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem. 2009;121:7108. [Google Scholar]; c) Rashidian M, Dozier JK, Distefano MD. Bioconjugate Chem. 2013;24:1277. doi: 10.1021/bc400102w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.a) Chudasama V, Maruani A, Caddick S. Nat Chem. 2016;8:114. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Agarwal P, Bertozzi CR. Bioconjugate Chem. 2015;26:176. doi: 10.1021/bc5004982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.a) Mazmanian SK, Liu G, Ton-That H, Scheenwind O. Science. 1999;285:760. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5428.760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Kruger RG, Otvos B, Frankel BA, Bentley M, Dostal P, McCafferty DG. Biochemistry. 2004;43:1541. doi: 10.1021/bi035920j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.a) Ton-That H, Liu G, Mazmanian SK, Faull KF, Scheenwind O. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:12424. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Ton-That H, Mazmanian SK, Faull KF, Scheenwind O. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:9876. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.13.9876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mao H, Hart SA, Schink A, Pollok BA. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:2670. doi: 10.1021/ja039915e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Antos JM, Miller GM, Grotenbreg GM, Ploegh HL. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:16338. doi: 10.1021/ja806779e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Samantaray S, Marathe U, Dasgupta S, Nandicoori VK, Roy RP. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:2132. doi: 10.1021/ja077358g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pritz S, Wolf Y, Kraetke O, Klose J, Bienert M, Beyermann M. J Org Chem. 2007;72:3909. doi: 10.1021/jo062331l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parthasarathy R, Subramanian S, Boder ET. Bioconjugate Chem. 2007;18:469. doi: 10.1021/bc060339w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chan L, Cross HF, She JK, Cavalli G, Martins HFP, Neylon C. PLoS One. 2007;2:e1164. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bellucci JJ, Bhattacharyya J, Chilkoti A. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2015;54:441. doi: 10.1002/anie.201408126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem. 2015;127:451. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen I, Dorr BM, Liu DR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:11399. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1101046108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frankel BA, Kruger RG, Robinson DE, Kelleher NL, McCafferty DG. Biochemistry. 2005;44:11188. doi: 10.1021/bi050141j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Popp MW, Antos JM, Grotenbreg GM, Spooner E, Ploegh HL. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;3:707. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2007.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.a) Heck T, Pham P, Yerlikaya A, Thöny-Meyer L, Richter M. Catal Sci Technol. 2014;4:2946. [Google Scholar]; b) Heck T, Pham P, Hammes F, Thöny-Meyer L, Richter M. Bioconjugate Chem. 2014;25:1492. doi: 10.1021/bc500230r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Warden-Rothman R, Caturegli I, Popik V, Tsourkas A. Anal Chem. 2013;85:11090. doi: 10.1021/ac402871k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.a) Zakeri B, Fierer JO, Celik E, Chittock EC, Schwarz-Linek U, Moy VT, Howarth M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:e690. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115485109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Li L, Fierer JO, Rapoport TA, Howarth M. J Mol Biol. 2014;426:309. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2013.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosen CB, Kwant RL, MacDonald JI, Rao M, Francis MB. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2016;55:8585. doi: 10.1002/anie.201602353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem. 2016;128:8727. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cranfill PJ, Sell BR, Baird MA, Allen JR, Lavagnino Z, de Gruiter HM, Kremers G, Davidson MW, Ustione A, Piston DW. Nat Methods. 2016;13:557. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.a) Levary DA, Parthasarathy R, Boder ET, Ackerman ME. PLoS One. 2011;6:e18342. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Kornberger P, Skerra A. mAbs. 2014;6:354. doi: 10.4161/mabs.27444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Policarpo RL, Kang H, Liao X, Rabideau AE, Simon MD, Pentelute BL. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2014;53:9203. doi: 10.1002/anie.201403582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem. 2014;126:9357. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li YM, Li YT, Pan M, Kong XQ, Huang YC, Hong ZY, Liu L. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2014;53:2198. doi: 10.1002/anie.201310010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem. 2014;126:2230. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.