Abstract

Ion channels represent the molecular entities that give rise to the cardiac action potential, the fundamental cellular electrical event in the heart. The concerted function of these channels leads to normal cyclical excitation and resultant contraction of cardiac muscle. Research into cardiac ion channel regulation and mutations that underlie disease pathogenesis has greatly enhanced our knowledge of the causes and clinical management of cardiac arrhythmia. Here we review the molecular determinants, pathogenesis, and pharmacology of congenital Long QT Syndrome. We examine mechanisms of dysfunction associated with three critical cardiac currents that comprise the majority of congenital Long QT Syndrome cases: 1) IKs, the slow delayed rectifier current; 2) IKr, the rapid delayed rectifier current; and 3) INa, the voltage-dependent sodium current. Less common subtypes of congenital Long QT Syndrome affect other cardiac ionic currents that contribute to the dynamic nature of cardiac electrophysiology. Through the study of mutations that cause congenital Long QT Syndrome, the scientific community has advanced understanding of ion channel structure-function relationships, physiology, and pharmacological response to clinically employed and experimental pharmacological agents. Our understanding of congenital Long QT Syndrome continues to evolve rapidly and with great benefits: genotype-driven clinical management of the disease has improved patient care as precision medicine becomes even more a reality.

I. INTRODUCTION

A genetic disorder disrupting electrical activity in the heart, congenital Long QT Syndrome (LQTS) can lead to life-threatening arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death. In the first cases of congenital LQTS, described in 1957, several children in one family presented with prolongation of the QT interval on the electrocardiogram (ECG) and congenital deafness (189). This came to be known as Jervell and Lange-Nielsen syndrome (JLNS), the autosomal recessive form of LQTS. The more common, autosomal dominant form of congenital LQTS that presents without deafness was first described in 1963 and 1964 in two separate cases and became known as Romano-Ward syndrome (346, 459). Since these initial patient descriptions, advances in our understanding of the mechanisms of cardiac electrical excitability at the tissue, cellular, and molecular level have yielded much insight into the pathophysiology of congenital LQTS.

Clinically, congenital LQTS patients often first present after episodes of syncope and/or seizure, and the ECG reveals a prolonged QT interval. The ECG measures electrical activity of the heart over time, at the patient's body surface. The primary electrical signals observed include the P wave, which signifies atrial depolarization; the QRS complex, which arises from ventricular depolarization; and the T wave, due to ventricular repolarization (Figure 1A). The QT interval, therefore, reflects the time elapsed from the initiation of ventricular depolarization to the end of ventricular repolarization. The QT interval shortens with increasing heart rate thus requiring a normalization, or “correction,” for heart rate. For a diagnosis of LQTS, this rate-corrected QT (QTc) interval prolongation on a 12-lead ECG generally is referenced as >470 ms for males and >480 ms for females. QTc also varies with age, and thus, an age-appropriate prolonged QTc interval in a patient aids the diagnosis of LQTS (209). However, diagnosis of LQTS based on absolute QT interval cutoffs can be challenging, since there is considerable overlap in the QTc distribution of affected patients and otherwise healthy individuals (193). Asymptomatic patients can have intervals beyond these cutoff and develop no arrhythmias; similarly, QTc intervals below this cutoff can be seen in patients with established LQTS (with clinical arrhythmias and positive genetic testing) (16, 17, 338). Clinical scoring systems (368), as well as genetic testing, can be helpful to assist with the diagnosis of congenital LQTS (193), particularly when QT intervals are on the borderline (within 20 ms of these cutoffs) or when clinical history is equivocal. This review will focus primarily on the various forms of congenital LQTS.

FIGURE 1.

ECG to cellular ionic currents. A: membrane depolarization and the rapid upstroke of the ventricular action potential give rise to the QRS complex. The duration of the QT-interval corresponds to the time to ventricular repolarization. The relatively stable membrane potential during the plateau phase of the action potential gives rise to a brief isoelectric period. Ventricular repolarization gives rise to the T-wave. B: time course of several ionic currents that underlie ventricular action potential morphology (currents not to scale). The rapidly activating and inactivating INa drives membrane depolarization. Two K+ currents, IKs and IKr, contribute most to the repolarizing current necessary to drive membrane potential back to rest.

Ion channels are the molecular entities underlying most ionic currents in the heart, allowing passive diffusion of ions across the cell membrane's electrochemical gradients (Figure 2). A selectivity filter in the channel pore, determined by distinct atomic components (152, 315), endows selective permeation of ions, such as Na+, K+, and Ca2+ (246). Some ion channels exhibit voltage-dependent gating, where voltage-sensing domains respond to changes in membrane potential to cause channel opening or closing (247).

FIGURE 2.

Schematic of a generic K+ and Na+ ion channel. Ion channels allow for selective permeation of ions through the plasma membrane down their electrochemical gradient. The classic K+ channel consists of four identical pore-forming subunits, whereas each Na+ channel is formed by a single polypeptide with four homologous domains.

The ventricular cellular action potential results from the summation of a large number of ion channel currents and electrogenic pumps that control the cellular membrane potential (see Nerbonne and Kass review, Ref. 299), but in this review we will focus on three key ion channels that are well-established to be linked to LQTS and that are illustrated in Figure 1B. The cellular resting membrane potential is approximately −85 mV, determined largely by inwardly rectifying K+ channels. Inward rectification is a property that hinders the outward flow of K+ as membrane potentials become positive, but passes K+ more efficiently at potentials negative to the K+ equilibrium potential where the flow of K+ would be inward. Hence, the term “inward rectification” is used to describe these channels (304). Activation of Nav1.5, the primary voltage-gated sodium channel in the heart, leads to sodium influx (INa) and membrane depolarization. As the cell reaches approximately −40 mV, voltage-gated L-type calcium channels begin to open, leading to calcium influx (ICa) (299). Concurrently during the upstroke of the action potential, potassium channels, including those carrying the IKs and IKr delayed rectifier currents, begin to activate slowly. As the cell reaches +30 mV, INa inactivates almost completely. At this time, a brief and small repolarization of the membrane potential occurs via fast activation of the transient outward K+ current, Ito. In the plateau phase that follows, influx of Ca2+ through voltage-gated calcium channels is balanced mainly by IKs and IKr. The plateau phase ceases as calcium channels inactivate and outward potassium efflux persists, leading to a net outward membrane current, and cell repolarization back to the cellular resting potential. During this process, the Na+-K+-ATPase helps maintain intracellular concentrations of these key ions (304).

In LQTS patients, the QT is prolonged presumably due to prolongation of underlying action potential durations (APDs), most often caused by decreased repolarizing IKs or IKr activity, or persistent sodium influx that extends through the plateau phase. A loss of IKs or IKr function, or a gain of INa function, predisposes ventricular myocytes to early afterdepolarizations (EADs), and in some cases to delayed afterdepolarizations (DADs) which may underlie degeneration into a characteristic sinusoidal wave pattern on the ECG, referred to as torsades de pointes, which may further regress into ventricular fibrillation and sudden cardiac death. EADs are driven in large part by calcium entry via L-type calcium channels during prolonged action potential plateau phases, whereas DADs, which occur over the diastolic range of potentials after action potential repolarization, are caused by intracellular calcium overload, also a consequence of action potential prolongation (126). Additionally, arrhythmic activity may result from altered refractoriness and impulse block, also putative consequences of prior APD prolongation. Thus treatment in LQTS aims to prevent malignant ventricular arrhythmia by shortening the QTc interval to minimize cardiac event rates.

Ion channels may interact with a variety of molecular entities that contribute to their trafficking, stabilization, signaling, and function (299). Coordination among different ion channel types facilitates the ionic balance necessary for the generation of an action potential and normal electrical propagation through the heart. LQTS mutations may cause an increase or decrease in ion channel function, disrupting normal ionic balance leading to pathological electrical activity in the heart.

There are 15 subtypes of congenital LQTS, each associated with mutations on a different gene (15) (Table 1). The most common subtypes, LQT1, LQT2, and LQT3, account for the vast majority of congenital LQTS. LQT1 and LQT2 are associated with mutations in KCNQ1 and KCNH2 (which encodes hERG), respectively, while LQT3 is associated with mutations in SCN5A, the gene coding for the Nav1.5 sodium channel alpha subunit. Disease association for variants in these three proteins is supported by genome-wide association studies (300) and functional electrophysiological characterization of mutant channels. In addition, LQTS-associated mutations exist less frequently in other ion channels, modulatory channel subunits, and signaling- or cytoskeleton-associated proteins. Understanding the molecular mechanisms that cause LQTS allows for optimization of genotype-specific treatments. In this review, we discuss the molecular physiology, biology, and pathophysiology underlying congenital LQTS, and the cellular and molecular underpinnings of genotype-driven clinical management of LQTS.

Table 1.

Subtypes of congenital LQTS and their associated genes, proteins, and effects on cardiac currents

| LQT Subtype | Gene | Protein | Current |

|---|---|---|---|

| LQT1 | KCNQ1 | KCNQ1 (Kv7.1) | ↓IKs |

| LQT2 | KCNH2 | hERG (Kv11.1) | ↓IKr |

| LQT3 | SCN5A | Nav1.5 | ↑INa |

| LQT4 (ankyrin-B syndrome) | ANK2 | Ankyrin-B | Multichannel interactions |

| LQT5 | KCNE1 | KCNE1 (minK) | ↓IKs |

| LQT6 | KCNE2 | KCNE2 (MiRP1) | ↓IKr |

| LQT7 (Andersen-Tawil syndrome type 1) | KCNJ2 | Kir2.1 | ↓IK1 |

| LQT8 (Timothy syndrome) | CACNA1C | Cav1.2 | ↑ICa |

| LQT9 | CAV3 | Caveolin 3 | ↑INa |

| LQT10 | SCN4B | Nav1.5 β4 | ↑INa |

| LQT11 | AKAP9 | AKAP-9 (yotiao) | ↓IKs |

| LQT12 | SNTA1 | α1-Syntrophin | ↑INa |

| LQT13 | KCNJ5 | Kir3.4 (GIRK4) | ↓IKACh |

| LQT14 | CALM1 | Calmodulin | Multichannel interactions |

| LQT15 | CALM2 | Calmodulin | Multichannel interactions |

II. IKs DYSFUNCTION IN CONGENITAL LQTS

A. Introduction

Of the different subtypes of inherited LQTS, subtypes 1, 5, and 11 are associated with mutations in proteins that participate in the macromolecular complex which generates and modulates the slow delayed rectifier potassium current (IKs), which plays a critical role in the repolarization of the cardiac action potential. Among all LQTS subtypes, LQT1 is the most common, representing 30-35% of all congenital LQTS (8). Upregulation of IKs during β-adrenergic stimulation is critical to normal physiology by shortening ventricular APD and allowing for adequate diastolic filling in the context of an elevated heart rate (354). Cardiac events in patients with IKs-associated LQTS are often triggered by stress and exercise, consistent with the role of adrenergic stimulation in the regulation of IKs (350, 371). Insight into the molecular mechanisms of disease mutations have greatly improved our understanding of LQTS pathophysiology and helped provide a first step to the future development of targeted therapies.

B. Physiology

IKs is an outward potassium current with unique kinetics and voltage dependence and plays a key role in the repolarization of the cardiac action potential (299). In 1969, the delayed rectifier potassium current in sheep Purkinje fibers was studied and shown to comprise two kinetically distinct components (305). These currents were later subjected to pharmacological dissection in guinea pig ventricular myocytes and identified as IKs and IKr (360).

IKs is slowly activating and most prominent during the plateau and repolarizing phases of the cardiac action potential, where it contributes to counterbalancing calcium influx and repolarization (Figure 1B). Expression of IKs has been demonstrated in both human atrial and ventricular myocytes (198, 235, 457). In addition, it has also been measured in cardiomyocytes from a variety of non-human mammalian species including dogs (241, 406, 437, 442, 493) and rabbits (352). On the other hand, IKs is expressed at very low levels or absent in mouse hearts (478), most likely because at very high heart rates in mouse heart (∼500 beats/min) this channel would have little or no time to activate and not affect cardiac electrophysiology in the mouse.

Importantly, IKs is subject to upregulation by β-adrenergic stimulation to control APD in the face of sympathetic nerve activity (210, 444). During sympathetic activation, adrenergic stimulation increases the outward IKs current, which counterbalances the concomitant increase in inward calcium current, prevents prolongation of the cardiac APD, and allows for adequate diastolic filling times between heart beats (386). However, insufficient IKs activation such as that seen in LQT1 results in failure to counterbalance the calcium influx, prolonging the action potential and increasing susceptibility to arrhythmia. This is consistent with exercise being a key trigger of cardiac events seen in LQT1 patients (371).

C. Molecular Biology

The first known subtypes of inherited LQTS, LQT1-3, were distinguished by mapping to distinct chromosomes, with LQT1 mapping to chromosome 11 (191, 212, 213). Eventually it was found that the KCNQ1 (KvLQT1) gene is responsible for LQT1 and encodes a potassium channel (451). The current conducted by this channel was rapidly activating and minimally inactivating, unlike any previously known current in the heart, but soon it was shown that KCNQ1 together with the accessory protein KCNE1 (minK) generates IKs (36, 358). While KCNE1 had previously been thought to be an independent potassium channel (167, 412), it was confirmed that KCNQ1 is actually the α- or pore-forming subunit of IKs while KCNE1 is a critical β- or modulatory subunit. Coexpression of KCNQ1 and KCNE1 generates the hallmark IKs current with slow activation. KCNQ1 and KCNE1 have been shown to be expressed in all four chambers in the heart (45), as well as the inner ear (301, 351), where IKs is thought to play a role in K+ secretion into the endolymph (68). This explains the observation that congenital deafness is a key feature of JLNS. In addition, KCNQ1 and KCNE1 are expressed elsewhere in the body, including the pancreas, the kidneys, and the brain (1).

1. KCNQ1, the pore-forming subunit

KCNQ1, like most voltage-gated potassium channels, consists of six transmembrane helices (451) (Figure 3A). Four subunits of KCNQ1 come together to form a channel that is capable of voltage-dependent gating (Figure 3B). On each subunit, the helices S1–S4 comprise the voltage-sensing domain, where the S4 helix, with its positively charged arginine residues, senses changes in membrane potential (310). Following the voltage-sensing domain is the pore domain, which comprises the pore-loop, an extracellular segment containing the selectivity filter, and helices that line the pore, S5 and S6. Furthermore, the cytoplasmic loop between S4 and S5 plays important roles in the voltage sensor-to-pore coupling and in voltage-dependent gating (82, 229, 498), which has been demonstrated in other voltage-gated channels as well (75, 122, 355). The cytoplasmic loop between S2 and S3 also plays a role in channel gating (498). The COOH-terminal domain (CTD) of KCNQ1 is large and contains four intracellular α-helices referred to as A-D. A wide range of functions has been attributed to the CTD including calmodulin binding, interaction with β-subunits and scaffolding proteins, as well as channel assembly and trafficking (159, 469).

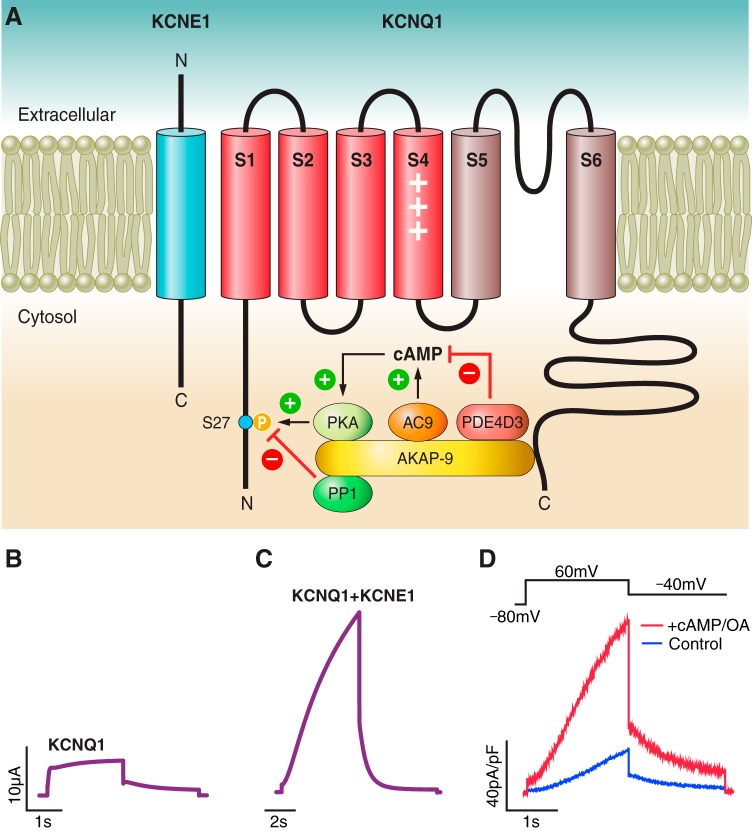

FIGURE 3.

Molecular biology of IKs and regulation by PKA-mediated signaling. A: the IKs macromolecular complex, including KCNQ1, KCNE1, and associated scaffolding and signaling proteins. B and C: single pulse voltage-clamp recordings of KCNQ1 expressed alone or coexpressed with KCNE1 in Xenopus oocytes. D: dialysis with 200 μM cAMP and 0.2 μM okadaic acid (OA) increases IKs amplitude and slows deactivation when heterologously expressed in CHO cells. [From Chen et al. (78).]

2. KCNE1, the β-subunit

Coexpression of KCNE1 with KCNQ1 leads to a drastic change in channel function to generate IKs. Most prominently, assembly with KCNE1 leads to a delay in the onset of activation, an increase in channel amplitude (Figure 3C), as well as a depolarizing shift in the current-voltage relationship (not illustrated) (36, 358). This results in a channel that, compared with most other voltage-gated potassium channels, activates at more positive voltages and with slower kinetics. KCNE1 is a 129-amino acid protein that consists of a single transmembrane helix, with an extracellular NH2 terminus and intracellular COOH terminus (412). It is thought to have extensive contact with KCNQ1 including the voltage-sensing domain (37, 84, 203, 309, 378, 479), the pore domain (84, 262, 311), as well as the CTD (161, 510). Previous crosslinking studies suggest that KCNE1 is located in a cleft between the voltage-sensing domain and pore domain of different KCNQ1 subunits (84, 479), underlying its ability to modulate KCNQ1 gating. With respect to the stoichiometry of KCNE1 to KCNQ1, some studies suggest a fixed 2:4 ratio (278, 326), while others suggest a flexibility in stoichiometry (293, 456) that allows for modulation of kinetics of assembled channels to provide another level of flexibility in channel function. Although three other members of the KCNE family, KCNE2-KCNE4, also are expressed in the heart (45) and are capable of modulating KCNQ1 activity (45, 154, 367, 422), whether they associate with KCNQ1 in vivo to contribute to potassium currents in the heart remains to be explored.

3. Molecular components of adrenergic stimulation

There have been considerable efforts to elucidate the molecular pathway for the β-adrenergic regulation of IKs. In 1988 it was shown that stimulation of PKA activity by a cAMP analog can upregulate the delayed rectifier current (444). Later it was shown that the scaffolding protein A-kinase anchoring protein 9 (AKAP-9), also known as yotiao, plays a central role in adrenergic regulation of IKs by compartmentalizing key elements of the PKA signaling pathway, allowing for spatiotemporal control. AKAP-9 binds to the CTD of KCNQ1 and recruits signaling proteins including protein kinase A (PKA), protein phosphatase 1 (PP1) (255), adenylyl cyclase 9 (AC9) (238), and the phosphodiesterase PDE4D3 (419) (Figure 3A). Together these proteins form the IKs macromolecular complex that can tightly control the phosphorylation state of the channel in response to adrenergic stimulation. PKA phosphorylates KCNQ1 at the S27 residue, adding a phosphate group and hence a change in charge to this residue, which leads to increased channel activation and slower deactivation (226, 255) (Figure 3D). In addition, phosphorylation of AKAP-9 itself contributes to the PKA-mediated upregulation of IKs (78).

4. Role of PIP2 and calmodulin in IKs function

The lipid molecule phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) is critical for KCNQ1 function. PIP2 is found in the inner leaflet of plasma membranes (260) and can regulate a variety of ion channels (51, 83, 172, 179, 250, 475). PIP2 mainly binds to KCNQ1 at its cytoplasmic loops and the COOH-terminal region near S6 (80, 208, 498), which are thought to form the interface between the voltage-sensing domain and the pore domain (82, 497). PIP2 binding is mediated by electrostatic interactions between the anionic lipid headgroup and positively charged channel residues (418). Rundown of PIP2 in the membrane leads to a drastically reduced IKs amplitude and accelerated deactivation, suggesting that PIP2 stabilizes the open state of IKs (250). Furthermore, PIP2 rundown reduces the current amplitude of KCNQ1 in the absence of KCNE1 (239). In addition, PIP2 plays a critical role in the coupling between voltage sensor movement and pore opening/closing (498). Interestingly, one modulatory effect of KCNE1 on KCNQ1 is a large (100-fold) increase in channel sensitivity for PIP2, which contributes to augmentation of KCNQ1 current amplitude (239). Whether PIP2 level is under control by physiological mechanisms to modulate IKs in cardiomyocytes remains to be demonstrated.

Calmodulin is a calcium-binding protein that serves in myriad calcium signaling pathways, some of which regulate ion channels (399). Calmodulin has been linked to IKs function (141, 379). Multiple studies have shown that calmodulin binding to the CTD of KCNQ1 is important for normal channel trafficking and folding (141, 379).

5. Channel trafficking

A variety of molecular entities are involved in the trafficking of KCNQ1KCNE1. The small GTPase-RAB11 plays an important role in the exocytosis of KCNQ1-KCNE1 to the plasma membrane, while RAB5 mediates endocytosis of KCNQ1-KCNE1 from the plasma membrane into endosomes (374). In a physiological stress response, serum and glucocorticoid-regulated kinase 1 (SGK1) upregulates KCNQ1-KCNE1 expression by increasing RAB-11-dependent channel exocytosis (374). There is also evidence to suggest that KCNQ1-KCNE1 can be internalized from the plasma membrane via clathrin-mediated endocytosis, a process facilitated by KCNE1 (480). Furthermore, KCNQ1 expression is regulated by ubiquitination, which can label membrane proteins for internalization and degradation. For example, the ubiquitin ligase Nedd42 can ubiquitinate KCNQ1 (190), while ubiquitin-specific protease 2 (USP2) can prevent channel ubiquitination (221). Both processes allow for control of KCNQ1 expression.

D. Molecular Pathophysiology

There are more than 530 disease-causing mutations associated with the IKs complex (15). While most of these are missense mutations, they also include nonsense mutations, splice site mutations, frameshifts, as well as deletions. The vast majority are mutations in KCNQ1, which cause LQT1, but a number of LQTS-causing mutations have also been found in KCNE1 and AKAP-9, which are classified as LQT5 and LQT11, respectively. JLNS, an autosomal recessive form of LQTS with severe bilateral sensorineural deafness, has so far only been associated with mutations in KCNQ1 or KCNE1 (423). Nonetheless, the majority of LQTS arising from mutations in IKs are autosomal dominant in a form known as Romano-Ward syndrome, which is not associated with deafness.

Congenital LQTS patients with dysfunction in IKs present with prolongation of the QT interval on ECG. An ECG characteristic associated with LQT1 patients more specifically is a broad based T wave (Figure 4A). Dysfunction of IKs reduces repolarizing current during the plateau phase, thereby leading to APD prolongation (Figure 4B). With a prolonged APD, the cardiomyocyte is vulnerable to EADs (441, 500), where a second depolarization occurs prior to the complete repolarization of the first due to recovery of voltage-gated Na+ or Ca2+ channels from inactivation, triggering life-threatening arrhythmia such as torsades de pointes (26, 464). As previously mentioned, during adrenergic stimulation IKs plays an especially important role in controlling the cardiac APD. This manifests clinically in LQT1 patients as a susceptibility to arrhythmia during exercise (371).

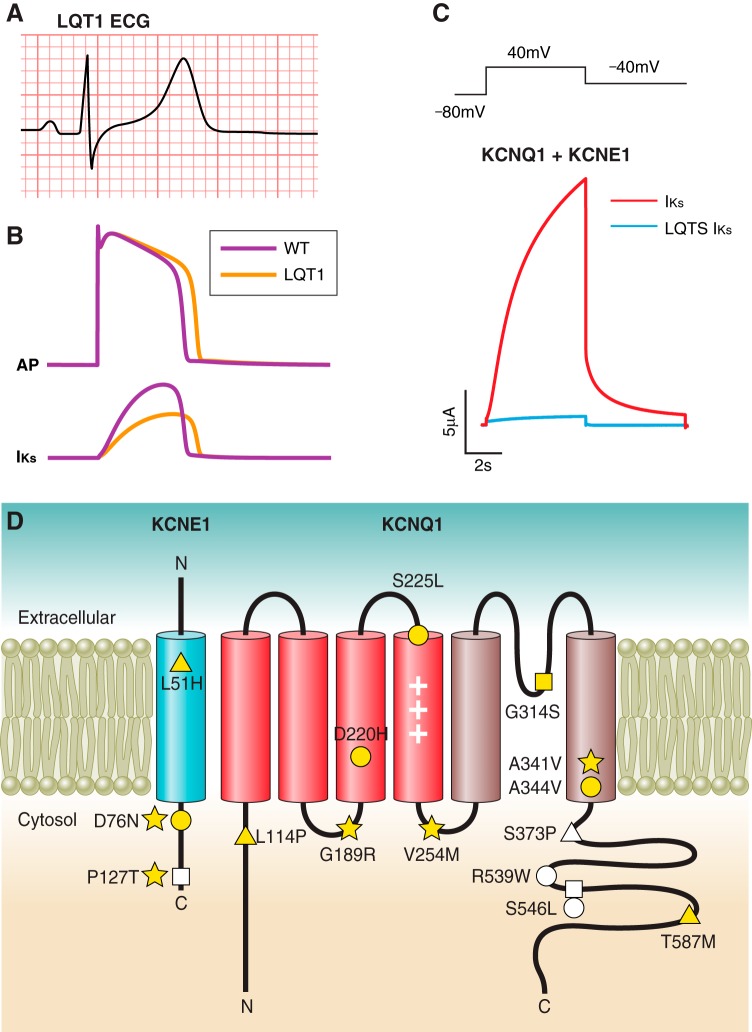

FIGURE 4.

IKs dysfunction leading to congenital LQTS. A: ECG from a LQT1 patient demonstrates a characteristic broad-based T wave (unpublished data). B: simulated action potential (top) and IKs (bottom) in WT (black) and heterozygous LQT1 (gray) conditions, demonstrating the effect of 50% reduction in IKs. C: single pulse voltage-clamp IKs recording in Xenopus oocytes demonstrating loss of channel function in an IKs-associated LQTS mutation. D: topology of KCNQ1 and KCNE1 in the plasma membrane. Several examples of LQT1- and LQT5-associated mutations are highlighted in blue and teal, respectively. These mutations represent a variety of mechanisms of loss-of-function including disruption of permeation (yellow-filled square), gating (yellow-filled circle), trafficking (yellow-filled triangle), PKA-mediated signaling (yellow-filled star), KCNQ1-KCNE1 interaction (white-filled square), PIP2 affinity (white-filled circle), and calmodulin affinity (white-filled triangle).

1. LQT1

Missense mutations are responsible for the majority of LQT1 cases and can cause channel loss of function through a variety of molecular mechanisms, including defects in ion permeation (altering the pathway through which ions flow through open channels), channel gating (mechanisms that regulate the opening and/or closing or channels), trafficking, KCNQ1-KCNE1 interaction, PKA-mediated signaling pathway, PIP2 binding, and calmodulin binding (Figure 4, C AND D) (Table 2). Non-missense mutations can also cause LQT1. Mutations belonging to certain groups may bear implications on patient phenotype, severity of arrhythmia, as well as response to therapy.

Table 2.

Representative LQT1-associated mutations classified by mechanism

| Mechanism | Mutations | Reference Nos. |

|---|---|---|

| K+ permeation | G314S, Y315C | 52, 237 |

| T322A, T322M, G325R | 13, 61 | |

| Gating | D202H | 113, 114 |

| S225L | 52, 170 | |

| R231C | 41 | |

| A344V | 391 | |

| Trafficking | Y111C, L114P, P117L | 98, 375 |

| T587M, R591H, R594Q | 205 | |

| PKA-mediated signaling | G189R, R190Q, R243C, V254M | 39 |

| A341V | 169 | |

| G589D | 255 | |

| KCNQ1-KCNE1 interaction | S546L, K557E | 110 |

| PIP2 affinity | R539W, R555C | 312 |

| S546L, K557E | 110 | |

| Calmodulin affinity | S373P, W392R | 379 |

| Large-scale defects | ||

| Nonsense | R518X, Q530X | 181 |

| Deletion-insertion, frameshift | Δ544 | 81 |

| Splice site | 1032G>A | 286 |

A) PERMEATION DEFECT.

A number of LQT1 mutations that lead to defects in permeation are found in the pore region of KCNQ1. Pore mutations are thought in general to carry greater risk of cardiac events than other mutations. One study shows that mutations in highly conserved residues, many of which are located in the pore-loop, are associated with higher risk of cardiac events (61, 197). Three LQT1 mutations near the selectivity filter, T322M, T322A, and G325R, have been shown to abolish channel conductance (13, 61). They exert dominant negative effects on wild-type (WT) IKs current in heterologous expression systems (61), suggesting that mutant subunits coassemble with WT subunits to form disrupted channels. Molecular dynamic simulations suggest that these mutations disrupt the conformation of the selectivity filter, leading to diminished K+ permeation. A pair of adjacent LQT1 pore mutations, G314S and Y315C, located in the selectivity filter, dramatically reduce IKs current amplitude and exert dominant negative effects on WT currents (52, 237). Immunofluorescence studies show that Y315C traffics to the membrane normally, suggesting that the mutation results in trafficking of non-conducting channels.

B) GATING DEFECT.

LQT1 mutations that cause defects in KCNQ1 gating can be found in the pore domain (S5–S6). Similar to other voltage-gated potassium channels, the COOH-terminal region of the S6 helix plays a key role in KCNQ1 gating (55, 157, 247). Scanning mutagenesis and heterologous expression studies show that a number of LQT1-linked residues in this region, such as F351 and L353, control KCNQ1 gating properties. For example, F351A leads to a drastic slowing of channel activation and a depolarizing shift in voltage dependence of activation, while L353K leads to a constitutively open channel (55). To further elucidate the mechanism of F351A, a technique known as voltage clamp fluorometry (VCF), which utilizes fluorophore labeling to allow simultaneous measurement of voltage sensor movement and channel current, has been used (37, 292, 308, 309, 348, 498). It was shown using VCF that F351A alters the coupling between voltage sensor and the pore (309), resulting in a slowly activating channel that partially resembles IKs. In addition, a LQT1 mutation in on the S6 helix, A344V, also affects channel gating by shifting the current-voltage relationship of IKs in the depolarizing direction by 30 mV, thereby destabilizing channel opening (391).

In addition to those in the pore domain, a number of LQT1 mutations that alter channel gating are found on the voltage-sensing S4 helix of KCNQ1. For example, the mutation S225L exerts dominant negative suppression of WT IKs current (52). This mutation alters channel gating, shifting the current-voltage relationship of IKs toward more depolarized membrane potentials (170). The effect of this mutation on voltage sensor movement remains to be determined, but given its location it is possible that it disrupts the movement of the S4 helix in response to changes in voltage. Another LQT1-associated mutation on S4, R231C, decreases peak IKs amplitude, but it also leads to constitutive activation at the same time (41). Interestingly, in one family, this mutation causes familial atrial fibrillation, which is more consistent with action potential shortening than prolongation (41, 296). To explain this finding, the study has used a computational model to show that the atrial action potential is more susceptible to shortening than ventricular action potential when IKs is made constitutively active (41). Structural and mutational studies suggest that R231 forms a salt-bridge interaction with E160 in S2 that stabilizes the channel in its closed state (340, 393, 472). Mutating R231 may disrupt this interaction and cause a defect in channel gating, resulting in constitutive activation. One tool that can be used to elucidate the effects of these S4 mutations on voltage sensor movement is VCF. The technique is capable of providing insights on IKs channel gating not possible with current measurement alone.

LQT1 gating mutations are also present in other transmembrane regions (S1–S3) of the voltage-sensing domain. For example, the mutation D202H leads to biophysical defects in IKs, shifting the current-voltage relationship to more positive potentials, slowing activation, and accelerating deactivation, all leading to reduced channel opening (114). Single-channel recordings of IKs utilized as a tool to study effects of select mutations (113) shows that D202H causes a decrease in channel open probability, a decrease in open states dwell time, and an increase in closed states dwell time, while maintaining single-channel conductance.

C) TRAFFICKING DEFECT.

In addition to altering channel gating, LQT1 mutations can also disrupt channel trafficking. Several LQT1 mutations in helix D of the CTD, including T587M, R591H, and R594Q, have been found to diminish channel trafficking to the membrane (205). These mutations are thought to disrupt a coiled-coil motif in helix D that plays an important role in channel trafficking (205). Yet trafficking mutations are not limited to the CTD of KCNQ1. LQT1 mutations in the NH2-terminal region of KCNQ1, including Y111C, L114P, and P117L, have also been found to reduce surface expression of KCNQ1 and increase retention in the endoplasmic reticulum (98). This region appears to be a conserved trafficking determinant across the KCNQ family. In particular, Y111C and L114P disrupt SKG1's ability to increase channel trafficking to the plasma membrane, suggesting that the NH2 terminus may be important in RAB-mediated exocytosis of channels (375).

D) DEFECT IN PKA-MEDIATED SIGNALING.

Given the critical importance of adrenergic stimulation and PKA-mediated signaling in the regulation of IKs and repolarization of the cardiac action potential during stress, disruption of this stimulation is expected to prolong the QT interval. For example, the mutation G589D is thought to disrupt a leucine zipper motif to which AKAP-9 binds, resulting in failure of IKs to be stimulated by cAMP (255). A mutation on S6, A341V, exhibits dominant suppression of IKs that fails to respond to adrenergic stimulation with cAMP (169). This effect is mediated by a reduction in the phosphorylation S27 on KCNQ1 and is not due to disruption in AKAP-9's interaction with KCNQ1. This result implicates a role of S6 in the regulation of the phosphorylation state of KCNQ1.

Mutations that lead to defective adrenergic stimulation of IKs in LQT1 patients are suggested to be associated with higher risk of cardiac events during exercise and greater response to β-blocker therapy. One study has identified missense mutations in the cytoplasmic loops between S2/S3 and S4/S5 of KCNQ1 to be associated with an elevated risk of aborted cardiac arrest and sudden cardiac death (39). Four mutations in these cytoplasmic loops, G189R, R190Q, R243C, and V254M, all diminish IKs upregulation in response to forskolin, an activator of the PKA signaling pathway, suggesting that patients with these mutations are expected to be especially susceptible to arrhythmic events during stress. This study bears implications on better risk-stratification for LQT1 patients and predicting response to β-blocker therapy. In addition, it suggests that the cytoplasmic loops are involved in adrenergic stimulation of KCNQ1.

E) DISRUPTED KCNQ1-KCNE1 INTERACTION.

A number of LQT1 mutations disrupt the KCNQ1-KCNE1 interaction. Two such mutations, S546L and K557E, are located in the helix C of the CTD of KCNQ1 and disrupt its interaction with the COOH terminus of KCNE1, as demonstrated by GST pulldown assays (110). The same mutations also decrease channel affinity for PIP2, leading to decreased current amplitude and a depolarizing shift in the current-voltage relationship. The decreased PIP2 affinity may be due to disruption of a potential PIP2 binding site on helix C.

F) DECREASED PIP2 AFFINITY.

Some LQT1 mutations have been shown to decrease channel PIP2 affinity. In addition to the mutations described above, two LQT1 mutations on helix C of the CTD, R539W and R555C, both lead to decreased PIP2 affinity, decreased IKs amplitude, and a depolarizing shift in the current-voltage relationship, underscoring the importance of the CTD in PIP2 binding (312). The cytoplasmic loops of KCNQ1 between S2/S3 and S4/S5 also play important roles in PIP2 binding and channel gating (208, 498). Several LQT1-linked residues in these cytoplasmic loops, including residues 195, 258, and 259, are thought to form a binding site for PIP2. Disease mutations in this binding site may result in decreased PIP2 affinity, leading to altered channel function (80, 498).

G) DECREASED CALMODULIN AFFINITY.

A number of LQT1 mutations have been found to weaken calmodulin binding to KCNQ1 as the underlying mechanism of disease. For example, the mutations S373P and W392R, located in the CTD, reduce calmodulin binding both in the absence and presence of KCNE1 (379). Both of these mutations cause decrease in surface channel expression and dramatic reduction in IKs amplitude. Overexpression of calmodulin is able to increase S373P mutant channel expression in the membrane. These results are consistent with the role calmodulin plays in channel assembly and trafficking (141, 379).

H) NON-MISSENSE MUTATIONS.

Non-missense mutations can also cause LQT1. For example, nonsense LQT1 mutations such as R518X and Q530X introduce a stop codon, leading to early termination of channel transcription and loss of IKs function (181). These mutations are mostly associated with autosomal recessive LQTS, although autosomal dominant cases have also been reported for R518X. One study shows that these mutant channels only mildly affect WT IKs current, consistent with their mostly recessive mode of inheritance (349). It is thought that the nonsense transcripts are selectively degraded and do not interfere with WT channel production. Interestingly, the same study suggests that LQT1 patients with nonsense mutations have reduced risk of cardiac events compared with patients with missense noncytoplasmic loop mutations, although the explanation remains to be determined.

Another non-missense LQT1 mutation is the deletion-insertion at residue 544, denoted Δ544, which leads to a frameshift that alters subsequent 107 amino acids and introduces an early stop codon (81). It is an autosomal recessive mutation occurring in the CTD. The mutation has been shown to disrupt channel assembly in vitro (364), underscoring the role of the CTD of KCNQ1 in channel assembly.

LQT1 mutations can also disrupt transcript splicing. A base substitution at a consensus splice donor site the end of exon 7, 1032G>A, can lead to a dropped exon 7 or exons 7 and 8 (286). In terms of channel regions affected, exon 7 encodes parts of the pore-loop and S6, while exon 8 encodes the rest of S6 and part of the CTD. Transcripts lacking one or both of these exons therefore are not expected to produce functioning channels. A study shows that this splicing mutation exerts a dominant-negative suppression of WT IKs, likely through a direct interaction between mutant and WT channels preventing trafficking to the membrane (428). In addition to splice donor sites, splice acceptor sites can also be mutated in LQT1, such as the base substitution 922-1 G→C at the end of intron 6, which leads to the loss of exons 7 and 8 (286).

2. LQT5

Coassembly of KCNQ1 with the KCNE1 subunit is key to the generation of the IKs current. Thus it follows that KCNE1 mutations can alter the physiologically critical current of the assembled channel and lead to LQT5. Similar to LQT1, the mode of inheritance for LQT5 can be autosomal dominant (RW) or recessive (JLNS) (107, 430). Mutations in KCNE1 can lead to defects in gating, trafficking, KCNQ1-KCNE1 interaction, as well as adrenergic stimulation (Figure 4D) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Representative LQT5-associated mutations classified by mechanism

A) GATING DEFECT.

One LQT5 mutation that affects channel gating is D76N. It is an autosomal dominant mutation in the COOH terminus of KCNE1 that has been shown to drastically suppress IKs amplitude, accelerate deactivation, and cause a depolarizing shift in the voltage dependence of IKs activation when expressed in Xenopus oocytes and CHO cells (76, 405). Overexpression of the mutant KCNE1 in guinea pig ventricular myocytes leads to APD prolongation and early afterdepolarizations (176). The mutant appears to traffic normally to the cell surface (53) and does not disrupt KCNE1 binding to the COOH terminus of KCNQ1 (510). However, it reduces IKs upregulation secondary to stimulation of the PKA signaling pathway, suggesting a role for the COOH terminus of KCNE1 in adrenergic stimulation of IKs (226).

B) TRAFFICKING DEFECT.

In addition to channel gating, LQT5 mutations can lead to defects in channel trafficking. The JLNS mutation L51H, located in the transmembrane helix of KCNE1, results in diminished KCNE1 trafficking to the cell surface (53). Furthermore, when coexpressed with KCNQ1 in HEK cells, the mutant KCNE1 decreases KCNQ1 trafficking to the surface (53, 220). In addition, coexpression of the mutant KCNE1 with KCNQ1 in CHO cells leads to a diminished current amplitude and channel biophysical properties that resemble KCNQ1 alone rather than IKs, consistent with a drastic reduction of functional KCNE1 in the membrane. These results together suggest that the mutant KCNE1 interacts with KCNQ1 to disrupt the trafficking of both proteins to the membrane surface, leading to a reduction in current. The transmembrane region of KCNE1 may therefore be important to channel trafficking.

C) DISRUPTED KCNQ1-KCNE1 INTERACTION.

LQT5 mutations can disrupt the interaction between KCNE1 and KCNQ1 required to generate IKs. For example, the double mutation T58P/L59P, located in the transmembrane region of KCNE1, results in near-complete loss of IKs amplitude but has minimal effect when coexpressed with WT IKs in Xenopus oocytes (181). The mutation leads to a diminished ability for KCNE1 to associate with KCNQ1 in coimmunoprecipitation studies, suggesting that the transmembrane region of KCNE1 is important for the KCNQ1-KCNE1 interaction (166). Furthermore, the mutation P127T, located in the COOH-terminal region of KCNE1, appears to disrupt the interaction of KCNE1 with helix C in the CTD of KCNQ1 (110). Interestingly, the mutation was also found to diminish PKA-stimulated upregulation of IKs by decreasing phosphorylation at the S27 residue. Since PKA phosphorylation at this site was previously shown to be independent of KCNE1 (226), it is possible that the disruption in adrenergic stimulation by P127T is independent of the mutation's disruption of KCNQ1-KCNE1 interaction (110).

3. LQT11

AKAP-9 is a scaffolding protein and part of the IKs macromolecular complex that plays a critical role in the compartmentalization of adrenergic-stimulated PKA signaling pathway leading to IKs upregulation. That a mutation in AKAP-9, S1570L, can cause LQTS is a testament to the critical role of PKA signaling in the regulation of IKs macromolecular complex (79). This mutation is located near the COOH-terminal binding domain of AKAP-9, disrupting its interaction with KCNQ1, reducing cAMP-stimulated phosphorylation of KCNQ1, and abolishing IKs upregulation in response to cAMP-mediated stimulation. Computational modeling suggests that a disruption in the basal phosphorylation state of IKs alone can alter IKs function sufficiently to prolong APD (79).

E. Molecular Pharmacology

1. β-Blockers

β-Blockers have been demonstrated as a particularly effective form of therapy for LQT1 patients, who are more sensitive to stress- and exercise-induced arrhythmia than other LQT subtypes (282, 371). Insufficient upregulation of IKs by adrenergic stimulation to counterbalance concomitant rise in inward calcium current is thought to underlie APD prolongation in LQT1 during sympathetic activation (386). β-Blockers antagonize adrenergic receptors and helps prevent this imbalance between potassium and calcium currents, decreasing predisposition for cardiac arrhythmic events.

2. Channel activators

While IKs plays a critical role in cardiac repolarization, it is not a direct target of drugs currently used to treat LQTS. However, conceptually, IKs activators could allow for more precise rescue of disease phenotype. In this section we briefly review IKs activators and refer readers to other studies in which activators of the ATP-sensitive K+ channel, such as nicorandil, have been used in LQTS patients and model systems (14, 388). Currently there are no IKs activators being used in clinical trials or therapy, but a number of small molecules that activate IKs have been identified at the benchside and may guide future development of therapeutic agents. For example, the compounds DIDS and mefenamic acid both increase IKs current amplitude (5). In addition, DIDS has been shown to drastically slow IKs deactivation. Interestingly, the effects of these drugs appear to be dependent on the presence of KCNE1. Compared with KCNQ1 alone, current augmentation by these compounds is much greater in the presence of KCNE1, suggesting their effects are mediated by the β-subunit. Indeed, deletion of the residues 39–43 of KCNE1 leads to a diminished response to these compounds. To demonstrate the potential for activators as a class of therapeutic agents for LQTS in in vitro studies, DIDS and mefenamic acid have been shown to rescue IKs function in a LQT5 mutation, D76N. Future studies will be required to better understand their mechanisms of action and to develop IKs-specific activators that can be effective and used safely in patients.

Another KCNQ1 activator, ML277, has been shown to augment current for KCNQ1 alone more effectively than KCNQ1 with KCNE1 (492). In fact, its activating effect diminishes with progressive increase in KCNE1:KCNQ1 stoichiometry, suggesting that the β-subunit may act to preclude the drug from binding to the channel (491). While a drug with such properties is expected to have minimal effectiveness in human cardiomyocytes, surprisingly the same study showed that the drug can augment IKs and shorten action potential in human iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes from a healthy control. The mechanism underlying this effect requires further elucidation.

3. Channel blockers

IKs-specific blockers are not useful as therapeutic agents for LQT1, but serve as useful tools for research by allowing for pharmacological dissection of IKs currents. Chromanol 293B is the first known IKs-specific blocker, with an IC50 of 6.9 μM in Xenopus oocytes (62, 139). A more effective blocker, HMR1556, with an IC50 of 0.12 μM, was developed using Chromanol 293B as the lead compound (139). These drugs inhibit KCNQ1 with KCNE1 more effectively than KCNQ1 alone. Blockers of IKs are speculated to serve useful roles in the treatment of disease conditions resulting from IKs gain of function, such as familial atrial fibrillation.

III. IKR DYSFUNCTION IN CONGENITAL LQTS

A. Introduction

Alterations in IKr, the rapid component of the delayed rectifier current in the cardiomyocyte action potential (Figure 1), underlies congenital Long QT (LQT) syndromes type 2 and 6, which arise from mutations in the KCNH2 and KCNE2 genes, respectively. LQT2 is the second most common cause of congenital LQTS. KCNH2 mutations lead to defective hERG protein, resulting in a decrease in IKr. Mutations in KCNE2 cause defects in the KCNE2 (or MiRP1) protein leading to LQT6, which also results in a decrease in IKr. Irrespective of the underlying cause, a decrease in IKr delays repolarization of the cardiac action potential prolongs the QT interval on the ECG, and predisposes patients to lethal arrhythmia. This section reviews IKr dysfunction leading to congenital and IKr-mediated drug-induced LQTS. [For a detailed summary of hERG channel structure, molecular biology, and basic electrophysiology, see Vandenberg et al. (436).]

B. Physiology

Heterologous expression of hERG reveals a strong, near identical resemblance to IKr in cardiomyocytes (359, 427). IKr is distinguished based on its relatively slow activation and deactivation kinetics, combined with rapid inactivation and recovery from inactivation (Figure 5). Inactivation refers to a conformation of the channel protein in which the channels cannot conduct ions even if the activating machinery is in a conformation that would promote conduction of ions. Channels will not conduct ions when in an inactivated state, but will conduct ions after the channels recover from the inactivated state, a recovery that takes place at negative voltages (174). Deactivation refers to the transition to a conformation in which channels return to a closed, nonconducting state, a transition that also occurs at negative (diastolic) voltages. hERG channels undergo voltage-dependent and C-type inactivation. Because channel activation is slow relative to the rapidly occurring inactivation process, the hERG I–V curve takes on a bell-shaped relationship, as shown in Figure 5C. Upon repolarization of the membrane, channels recover from inactivation much faster than they deactivate. This crucial channel property results in a marked outward K+ current during the repolarization phase of the cardiomyocyte action potential. By this time, a large percentage of hERG channels have recovered from inactivation, such that outward potassium efflux helps return the cell to its resting potential, despite the fact that the electrochemical gradient for potassium efflux decreases as repolarization progresses (Figure 1B).

FIGURE 5.

hERG structure and electrophysiology. A: schematic of the IKr channel complex. Four hERG1 subunits tetramerize to comprise the pore-forming alpha subunit of IKr. hERG1 contains a voltage-sensing domain (purple), including the S4 helix which contains positively charged gating residues, and a pore domain (gray). KCNE2, an accessory subunit of the IKr channel complex, consists of a single transmembrane helix (blue). B: voltage-clamp protocol (top panel) and heterologously expressed hERG1 ionic currents (bottom panel) recorded from a Xenopus oocyte. Currents were recorded at potentials that ranged from −70 to +50 mV; deactivating (“tail”) currents were measured at −70 mV. C: current-voltage (I-V) relationship for hERG1 currents measured at the end of test pulses, as indicated by red circle in B. D: voltage dependence of hERG1 current activation. The peak of tail currents measured at −70 mV (indicated by blue square in B) were normalized to the largest value and plotted as a function of the test potential. E: voltage dependence of hERG1 inactivation. Channel availability is decreased at positive potentials, resulting in a decreased magnitude of peak outward currents and the bell-shaped I-V relationship depicted in C. [B–E from Sanguinetti (356), with permission of Springer.]

Since hERG inactivation and recovery from inactivation proceed more rapidly than activation or deactivation of hERG (365, 394, 401), IKr contributes to prolongation of the plateau phase duration and thus cardiomyocyte contraction, in addition to cardiac repolarization (361, 394). As hERG recovers from inactivation during cell repolarization, the repolarization itself promotes greater hERG recovery from inactivation due to the voltage dependence of hERG inactivation gating (359, 394, 427). As the cell continues to repolarize and return to its resting membrane potential, the slower process of channel deactivation progresses, leading to closure of hERG (436). The fraction of channels remaining open near the resting potential (see Figure 5E) acts to oppose cell depolarization (242, 394), which helps prevent premature heart beats from leading to an early action potential and a tachyarrhythmia. Loss of hERG function thus predisposes to arrhythmia in the setting of premature beats(46).

C. Molecular Biology

The KCNH2 gene, located on chromosome 7q35-36, encoding the human ether a go-go-related K+ channel protein (hERG), was first discovered in 1994 (460). Mutations in KCNH2 associated with congenital LQTS were discovered a year later in 1995 (97), and soon after, it was determined that hERG represents the α-subunits of the K+ channel responsible for IKr (359, 427). hERG may be referred to as “hERG1,” since other hERG proteins (hERG2 and hERG3) have since been discovered (385). hERG1a, the main hERG isoform present in cardiomyocytes, is 1,159 amino acids in length, with a predicted molecular weight of 127 kDa. As with most voltage-gated K+ channels, functional hERG channels are composed of four hERG α-subunits, forming either a hERG1a homomeric channel, or a hERG1a/hERG1b heteromeric channel that contributes to native cardiac IKr activity. The heteromeric assembly of hERG isoforms 1a and 1b has distinctively altered kinetics compared with hERG1a monomeric channels, including faster activation and deactivation. hERG1b is expressed in smaller amounts at the mRNA level in the heart compared with hERG1a, but nevertheless adds to the complexity of hERG channel regulation and potential therapeutic modalities (195, 196, 231, 323, 353, 426).

Each of the four hERG α-subunits consists of six transmembrane helices, S1–S6, as shown in Figure 5A. The voltage-sensing domain spans from S1 to S4; the S4 transmembrane segment of hERG contains the primary positively charged amino acids required for voltage-sensing and opening of the activation gate (325, 408, 505). The pore domain of the channel, spanning from S5–S6, harbors the K+ permeation pathway necessary for K+ conduction (Figure 5A) (105). The long cytoplasmic NH2 terminus contains the PAS domain with a PAS-cap, and together these sequences make up the “EAG” domain that is conserved among EAG-related voltage-gated potassium channels(274). The long cytoplasmic COOH terminus of the channel contains the cyclic nucleotide-binding domain (cNBD) (56), as well as a more distal RXR endoplasmic reticulum retention signal (224), and a coiled-coil domain (188).

The NH2-terminal PAS domain accelerates deactivation of hERG and plays a role in channel trafficking (77, 274, 436). Slow deactivation of hERG may involve interaction of the PAS domain in the NH2 terminus of the channel, with the S4–S5 linker (450), which couples movement of the transmembrane voltage sensor to activation gate movement (247). Experimental hERG mutants with a deleted PAS domain have faster deactivation kinetics (274, 401). Proper folding of the PAS domain also leads to trafficking of hERG from the endoplasmic reticulum to the plasma membrane (314). The cNBD contributes to channel trafficking and gating as well, while cAMP binding to the cNBD domain results in changes in the gating kinetics of the channel, which are altered in the presence of KCNE2, an accessory hERG subunit (see below) (94). Furthermore, the PAS domain and cNBD appear to bind, working in concert to modulate hERG gating by positioning the NH2-terminal residues in close proximity to the cytosolic side of S6 (23, 100, 160, 287).

hERG can coassemble with two different β-subunits in heterologous systems: KCNE1, encoded for by the KCNE1 gene; and KCNE2 (or the MiRP1 protein), encoded for by the KCNE2 gene (Figure 5A) (2, 259). KCNE1 and KCNE2 are single-pass transmembrane subunits that can interact with the hERG channel (2, 3, 20, 259). While the precise physiological role of the KCNEs in regulating hERG and IKr remains unclear (21, 257, 462), mutations in KCNE1 and KCNE2 lead to LQT5 and LQT6, respectively, and mutation of either KCNE1 or KCNE2 can predispose patients to drug-induced LQT syndrome, possibly via modulation of hERG activity (2, 9, 53, 295, 376, 402).

KCNE1 and hERG associate in heterologous systems and may contribute to regulation of IKr; however, KCNE1 is better characterized physiologically as the β-subunit of the KCNQ1 complex that produces IKs (36, 53, 259, 358). KCNE2 was reported to alter gating properties and drug responses of hERG channels(2), and mutations in KCNE2 leading to LQT6 likely result from changes in hERG and thus IKr current activity, producing a pro-arrhythmic state, further supported by the KCNE2 T10M mutation that confers an arrhythmogenic substrate to auditory stimuli, a known trigger of LQT2-associated arrhythmia (see Figure 7) (2, 151, 182, 251). It is possible that physiologically relevant KCNE2 expression exists only in the Purkinje fibers and pacemaker cells of the human heart (297, 330), which further confounds the exact role of KCNE2 as a β-subunit of hERG in vivo. Moreover, KCNE2 coassembles with KCNQ1, which decreases IKs current(192), adding to the complexity and diversity of IKs and IKr channel subunit interactions.

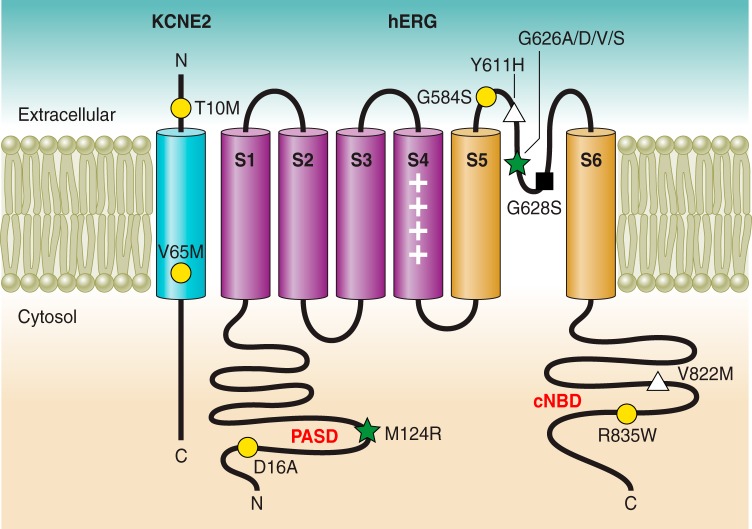

FIGURE 7.

Topology of hERG and KCNE1 in the plasma membrane, representative LQT2- and LQT6-associated mutations highlighted. Different mechanisms of loss of function in hERG or KCNE2, including gating (yellow-filled circle), K+ permeation (black-filled square), trafficking (white-filled triangle), or combined defects (green-filled star) are categorized.

D. Molecular Pathophysiology

A decrease in IKr results in LQT2 via mutations in the KCNH2 gene that encodes hERG, and LQT6 via mutations in the KCNE2 gene that encodes KCNE2 (or MiRP1) protein. The mechanisms underlying disease pathogenesis are described below.

1. LQT2

Patients with congenital LQT2 often present clinically after syncope or seizures not explained by a known medical condition. Prolongation of the QT interval on the ECG supports the diagnosis, and in LQT2 in particular, the T-wave may appear as a classic notched, or “bifid” T-wave (Figure 6A) (503). Syncope occurs following a common pathological process in the LQT syndromes, wherein delayed ventricular repolarization (and resultant QT interval prolongation on the ECG) precipitates an EAD, in some cases DADs, and ventricular tachycardia. EADs trigger the torsades de pointes sinusoidal waveform on the ECG, which may progress to ventricular fibrillation and sudden cardiac death (356).

FIGURE 6.

IKr dysfunction leading to congenital LQTS. A: ECG from a LQT2 patient demonstrates a characteristic “notched,” or bifid, T wave with QTc prolongation (unpublished data). B: simulated action potential (top) and IKr (bottom) in WT (black) and heterozygous LQT2 (gray) conditions, demonstrating the effect of 50% reduction in IKr.

Homozygous mutations in KCNH2 leading to LQT2 are extremely rare in humans, resulting in either death in utero, or very severe prolongation of the QT interval upon birth (175, 194). Heterozygous mutation leading to one defective hERG copy is far more common and may result in significant prolongation of the cardiac action potential duration (see Figure 6B). hERG mutations leading to LQT2 occur by a variety of genetic mechanisms. To date, ∼500 mutations in KCNH2 have been identified in association with LQT2 (23). A study analyzing 226 different LQT mutations in genotype-confirmed LQT2 patients reported that 62% of mutations were missense, 24% were frameshift, while 14% were a combination of nonsense mutations, inframe insertions/deletions, or splice site mutants in the KCNH2 gene. Of the combined 226 mutations, 32% resided in transmembrane and pore-pore domains; 29% in the NH2 terminus, including 8% in the PAS/PAC domains; and 31% in the COOH terminus, including 8% in the c-NBD (207). In terms of molecular mechanism, a small proportion of LQT2 mutations result in nonsense-mediated mRNA decay (150). More commonly, decreased protein trafficking to the cell surface leads to eventual endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation (ERAD) of mutant hERG (22, 149, 443, 512).

Several important general characteristics of KCNH2 mutations associated with congenital LQT2 were recently highlighted in a large-scale functional study of 167 different LQT2-associated missense mutations (23). Functional analysis was performed by voltage clamp after coexpression of WT and mutant subunits in HEK293 cells. Anderson et al. (23) found that 1) hERG trafficking defects comprised the most common (88%) mechanism of loss of function overall, derived from mutations in the PAS domain, pore domain, and C-linker/cyclic nucleotide-binding domain. Only the distal COOH-terminal region did not yield trafficking defects as the primary mechanism of loss-of-function. 2) Greater than 70% of pore mutations led to dominant negative suppression of hERG, whereas the other intracellular domain mutation locations did not yield dominant negative suppression of current. 3) All mutant channels, regardless of mutation location within the channel, were rescued pharmacologically by E4031, a hERG pore blocker that stabilizes channel structure and folding, thus promoting channel retention at the cell surface (148). Coexpression of WT with pore mutant channel rendered heteromeric pore mutant-WT channels especially responsive to pharmacological correction compared with coexpression of WT with non-pore mutant channels. Overall, these data suggest that pharmacological recovery of hERG channel function is feasible for a large proportion of LQT2 mutations(345) and raise the possibility of this approach as a therapeutic strategy for LQT-2 patients, but to our knowledge this has not been implemented in the clinic.

A) MUTATION SEVERITY: HAPLOTYPE INSUFFICIENCY VS. DOMINANT-NEGATIVE LOSS OF FUNCTION.

Heterozygous mutation resulting in defective KCNH2 gene expression or hERG protein that does not impact normal functioning of the WT hERG protein that remains yields haplotype insufficiency. Only the gene product from the mutant KCNH2 allele is negatively affected, while WT hERG subunits still homomerize to form functional channels. In contrast, some hERG mutations have increased pathogenicity by exerting a dominant-negative loss of channel function, wherein the mutant and defective KCNH2 gene product reduces function of the WT hERG protein encoded in the patient's genome via heteromerization of mutant with WT channel, rendering the healthy hERG subunits nonfunctional when combined with mutant hERG, either by decreasing forward trafficking of mutant WT channels, or decreasing function of the heteromers at the cell surface. In a study of LQT2 patients with 44 unique mutations in different regions of the hERG channel, it was discovered that those patients harboring mutations in the pore region of the channel were more susceptible to cardiac events than patients with non-pore region hERG mutations, likely due to a greater dominant-negative suppression of IKr current exerted by pore vs. non-pore mutations (187, 283).

Perhaps counterintuitively, more harmful mutations in one KCNH2 allele, resulting in a premature stop codon for instance, prevents formation of a hERG protein product from the mutant KCNH2 allele, leading to haplotype insufficiency and the possibility of a less severe phenotype compared with some dominant-negative mutations, as WT hERG remains unaffected(356).

Studies of specific hERG mutants have greatly enhanced our understanding of the underlying mechanisms of loss of function leading to LQT2. Figure 7 provides a schematic of representative LQT-associated hERG and KCNE2 mutations, categorized by mechanism of loss of function (see Table 4). Representative LQT-associated hERG mutations are divided into four general classes: I) decreased hERG synthesis, II) trafficking defect, III) gating defect, and IV) decreased K+ permeability (436).

Table 4.

Representative LQT2- and LQT6-associated mutations classified by mechanism

| Mechanism | Mutations | Reference Nos. |

|---|---|---|

| hERG LQT2 mutations | ||

| K+ permeation | G628S | 59, 116, 357 |

| Gating | D16A, G584S, T613A, I711V, R835W | 23, 329, 509 |

| Trafficking | Y611H, V822M | 512 |

| Decreased hERG synthesis | R1014X, W1001X, Y652X | 50, 150, 356, 409 |

| Multiple mechanisms (e.g., gating and trafficking) | F29L, M124R | 23, 206, 390 |

| KCNE2 LQT6 mutations | ||

| Gating | T10M, V65M | 151, 182 |

I) Decreased hERG synthesis. Defective biogenesis of hERG may occur via mRNA processing abnormalities or mRNA instability (150, 504). The hERG R1014X mutant mRNA transcript is degraded by “nonsense-mediated mRNA decay,” a cellular damage-control mechanism that destroys mRNA transcripts harboring nonsense mutations (premature stop codons), which prevents translation of a shortened hERG peptide (150, 356). Other nonsense-mediated decay mutants include W1001X (150) and Y652X (409). These mutations would result in haplotype insufficiency, as there would be 50% loss of function while the remaining WT hERG channels function normally. Nevertheless, a 50% reduction in IKr can lead to clinically significant LQTS.

II) hERG trafficking defects. Defective hERG trafficking is the most common mechanism of loss of hERG function (22, 23, 436), and most KCNH2 missense mutations cause trafficking defects in hERG (22). Trafficking mutants may result in either dominant negative loss of hERG function (22, 201) or haploinsufficiency (131). If WT hERG associates with trafficking-defective mutants to form heteromeric channels in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) or Golgi apparatus, dominant negative suppression of IKr results: 93% reduction in IKr was observed by this mechanism (123).

Defects in trafficking may be further subdivided by the underlying mechanism, protein trafficking, or protein misfolding (22, 124, 512); hERG protein becomes core glycosylated in the ER, with modifications made in the Golgi apparatus. When the mature hERG protein traffics to the plasma membrane, it weighs 155 kDa, versus 135 kDa for the core-glycosylated-only hERG protein. This difference in molecular weight aids in determining whether hERG possesses a trafficking and/or protein folding defect (512). The hERG Y611H and hERG V822M LQT2 associated mutations were found to have a molecular weight of 135 kDa, and thus had decreased trafficking to the plasma membrane due to protein misfolding. These mutant hERG channels were retained in the ER, and subsequently ubiquitinated and degraded in proteasomes (512).

III) hERG gating defects. Alteration in activation, deactivation, and/or inactivation kinetics can result in loss of function of hERG and a decrease in IKr at physiologically relevant membrane potentials. Any hERG mutation that, for instance, enhances the speed of inactivation, or causes a depolarizing shift in channel activation, ultimately leads to loss of hERG function at voltages ranging from the resting potential to the plateau phase of the action potential, depending on the nature of the gating defect (48, 77, 290, 357, 363, 509). Several hERG gating defect mutations have been described in mammalian cell lines (48, 363, 509).

Both the I711V and R835W mutations represent examples of c-NBD region LQT2 mutations in the COOH terminus of the channel, with altered channel gating. These hERG mutants deactivate faster at −50 mV compared with WT hERG. In addition, the R835W mutation confers a rightward, depolarizing shift (+16 mV) in the V0.5 of activation, while inactivation measured at 0 mV remains unchanged (23). Within the NH2 terminus of hERG, the LQT2 hERG D16A mutation exhibits a +13 mV rightward shift in the V0.5 of activation, with a minor slowing of inactivation at 0 mV and a slowing of deactivation at −50 mV (23, 302).

The hERG G584S pore mutation increases the rate of channel inactivation (509). G584S represents a pore mutation with a milder loss-of-function phenotype directly and solely attributed to its effect on inactivation. This finding adds further to the complexity of hERG mutant phenotypes as most other pore mutations cause increased arrhythmic events compared with non-pore hERG mutations (283). Recently, the hERG T613A mutation in the outer region of the pore helix, a regulatory site for C-type inactivation, was found to cause greater than 80% inhibition of maximal hERG current via a hyperpolarizing shift in channel inactivation when expressed in Xenopus oocytes alone; coexpression of WT and mutant channel resulted in an intermediate loss of channel function, without dominant-negative suppression of current (329).

Gating defects can arise from mutations across a wide range of locations in hERG, and predispose individuals to LQT2 of varying severity dependent on the functional impact of the mutation.

IV) hERG K+ permeation defect. The potassium selectivity filter in the pore of the hERG channel allows for potassium permeation with great specificity. Conserved amino acid residues comprise the selectivity filter, and mutation of any of these residues or nearby amino acids may greatly alter potassium permeation, even if only one of four hERG α-subunits within the mature channel bears the mutation (i.e., dominant negative suppression of IKr). The hERG G628S mutation, for instance, traffics to the cell surface and gates normally, which was confirmed by voltage-clamp fluorometry experimentation, but the mutant hERG channels do not conduct potassium under physiological conditions due to blockade of potassium permeation by intracellular potassium (116). The G628S mutation was also found to be cause lethal arrhythmia in transgenic rabbits with the mutation, as these rabbits possessed greater than 50% incidence of sudden cardiac death after one year (59).

B) COMBINED MECHANISMS OF LOSS-OF-FUNCTION IN LQT2.

Many mutations leading to LQT2 confer a loss-of-function hERG phenotype by multiple molecular mechanisms. Kanters et al. (206) recently reported the mechanistic basis of channel dysfunction of the hERG F29L mutation in a founder population of Danish families, which results in a malignant form of LQT2. The mutation causes clinically significant prolonged QT, with a penetrance of 73%. The F29L mutation was found to 1) reduce trafficking of hERG to the cell surface, posited to occur based on decreased glycosylation of the hERG F29L channel; and 2) reduce steady-state inactivation current density, positively shift the voltage dependence of inactivation, and increase the rate of deactivation. Similarly, the M124R mutation in the NH2 terminus residing close to the hydrophobic surface of hERG, results in faster channel deactivation, in addition to reduced trafficking to the cell surface (23, 390). Furthermore, the exact amino acid substitution can impact the mechanism of loss of function of the hERG channel: the LQT2-associated G626A mutation in the conserved K+ selectivity filter in the channel pore traffics to the cell surface normally, while the LQT2-associated G626D, G626V, and G626S mutations had trafficking defects. The exact amino acid substitution has potential therapeutic implications: of the three G626 trafficking mutants, only hERG G626S had its trafficking defect corrected by E4031, an experimental pharmacological agent that increases forward trafficking of hERG channels in addition to its pore blocking effects (23).

2. LQT6

KCNE2 (or MiRP1) protein, encoded for by the KCNE2 gene, modulates hERG activity as an accessory β-subunit (Figure 5A). Mutations in KCNE2 cause LQT6 due to a decrease in IKr (see Figure 7 and Table 4) (2). The V65M mutation in KCNE2, for example, induces faster inactivation of colocalized hERG/mutant KCNE2 channel complexes (182). The KCNE2 T10M was found linked to patients with cardiac arrhythmia and LQTS, with particular susceptibility to arrhythmia onset in the setting of auditory stimuli and hypokalemia, both common triggers of arrhythmia in LQT2 patients as well. Coexpression of KCNE2 T10M with hERG decreases tail currents and causes a hyperpolarizing shift in steady-state inactivation, along with slowed recovery from inactivation compared with WT channels in CHO cells. The impact of the KCNE2 T10M mutation in the setting of known LQT2 arrhythmia triggers supports the hypothesis that KCNE2 associates with hERG in the human heart to regulate IKr (151). As KCNE2 is known to interact with other K+ α-subunits in addition to hERG, defective KCNE2 may lead to varying phenotypes. Indeed, the KCNE2 M54T mutation leads clinically to LQT6 in addition to sinus bradycardia, the latter clinical finding mediated by reduction of the HCN4 pacemaker channel activity (297). The complexity of interactions of KCNE2 with a variety of potassium channels may inform differential phenotypes observed clinically in those harboring a KCNE2 mutation.

3. Autoimmune-associated LQT syndrome

Recently, Yue et al. (494) discovered that anti-Ro antibodies block the hERG channel, resulting in an autoimmune-associated LQTS. The anti-Ro antibodies, present in the serum of patients with a variety of common autoimmune illnesses, were found to inhibit IKr in HEK293 cells, and a guinea pig autoimmune model with circulating anti-Ro antibodies had a prolonged QTc interval, caused by inhibition of native IKr. Anti-Ro likely blocks hERG by binding within the pore region of the channel. Patients with anti-Ro-positive autoimmune illness may be well advised to take particular caution to avoid medications that prolong the QT interval (494).

E. Molecular Pharmacology

hERG channel modulation by pharmacological agents has become an increasingly studied research area because it is now well established that a wide variety of clinically used drugs block hERG and thus inhibit IKr, leading to drug-induced LQTS. The section below details mechanisms and the biomedical relevance of drug-induced LQTS, followed by a discussion of various pharmacological tools that hold promise as novel agents for the treatment of LQT2 (and LQT6) in the future.

1. Drug-induced LQTS

Most drugs that block IKr conduction bind to the open state of the hERG channel, binding the inner pore thereby preventing permeation of potassium (67, 215, 267, 400, 483, 513). The anti-arrhythmic pharmacological agent MK-499 interacts mostly with polar and/or aromatic residues within the channel pore, including Thr623, Tyr652, and Phe656, to induce hERG block (266). Different hERG-blocking drugs may interact with different combinations of these four residues (266, 319). For instance, the anti-arrhythmic agent dofetilide interacts with Phe656 to mediate hERG binding (233). While the aromatic and polar residues above are integral to hERG's supreme sensitivity to block by pharmacological agents, C-type inactivation may increase affinity of drugs to hERG's pore residues and enhance drug block (125, 171).

Some drugs, including pentamidine (90, 228) and probucol (156), cause a reduction in IKr by reducing trafficking of hERG to the plasma membrane, leading to prolongation of the QT interval. The widely clinically employed drugs fluoxetine and ketoconazole block hERG directly and decrease hERG channel density at the cell surface (337, 411). Several other pharmacological agents precipitate drug-induced LQTS in susceptible patients, via hERG blockade or modulation of other important ionic currents (e.g., INa, IKs) (439, 482).

KCR1, a 12-pass transmembrane segment regulatory protein, interacts with hERG and mitigates the proarrhythmic effects of hERG-blocking agents (178, 223). In heterologous conditions, KCR1 decreases the sensitivity of hERG to a variety of well-established hERG channel blockers, such as sotalol, quinidine, and dofetilide (223). Loss of function of KCR1 is associated with greater risk of arrhythmia: the KCR1 E33D mutant found in a patient with ventricular fibrillation and QT-interval prolongation conferred reduced protection against drug-induced hERG blockade (168). The KCR1 I447V variant is associated with lower frequency of drug-induced arrhythmia, and reduced sensitivity hERG block by dofetilide when coexpressed heterologously (322). These results suggest that functional KCR1 provides protection against a drug-induced decrease in IKr, with a mechanism of action thought to entail modulation of KCR1 α-1,2-glucosyltransferase activity (291).

2. Drug screening for hERG toxicity

Given the propensity for clinically relevant pharmacological agents to block hERG, leading to drug-induced arrhythmia, it is now a required practice for drugs early in development to undergo hERG toxicity screens. High-throughput screening techniques, including radioligand binding, ion flux and fluorescence assays, and hERG-Lite which measures cell surface density of hERG, detect candidate drugs with strong hERG-blocking and/or traffic-altering properties (436). The development of automated patch-clamp electrophysiology enhances the throughput of data acquisition tremendously, allowing for numerous hERG recordings from different cells, applying different drugs and at different concentrations, to be collected simultaneously. Automated patch-clamp technology is the best initial high-throughput hERG toxicity drug screening method to date (163). A focus on hERG toxicity screening early in the drug development process may save time, and prevent or minimize adverse clinical outcomes due to inadvertent IKr block.

3. Pharmacological treatment in LQT2

β-Blocker treatment represents first-line pharmacological therapy in LQT2 patients. For a more detailed discussion of β-blocker treatment in congenital LQTS, refer to section VI of this review.

A growing interest in hERG activators has developed. Such agents may be especially useful in the setting of congenital LQT2 and/or drug-induced LQT syndromes. hERG activators may be subdivided into type 1 activators type 2 activators, based on mechanism of hERG activation (436).

Type 1 hERG activators include RPR260243, an experimental small molecule compound that slows hERG deactivation in a temperature- and voltage-dependent fashion as its primary means of channel activation (204, 321). RPR260243 may slow deactivation via binding to the S4–S5 linker and the cytoplasmic regions of the S5 and S6 hERG domains (321).

Type 2 hERG activators act primarily by slowing channel inactivation, and/or shifting the voltage dependence of inactivation to more positive membrane voltages (69, 138, 153, 164). Type 2 activators may also have other relatively minor effects on deactivation kinetics and voltage dependence of activation, as well as single-channel open probability (69, 138, 164, 165, 407, 511). Several type 2 hERG activators have been described, including experimental compounds PD118057 (320), ICA105574 (28, 134, 263), and NS1643 (153, 155, 318), and key insights into their mechanism of action alongside their hERG binding location have been found, each having specific binding residues that mediate their mechanism of hERG activation within the “type 2” paradigm.

Other compounds have predominating mechanisms of hERG activation that do not fall into the “type 1” or “type 2” classes. For instance, mallotoxin and KB130015 primarily enhance hERG activation while shifting the voltage dependence of activation to more negative membrane voltages, likely by binding within the channel pore (140, 499). Some compounds, such as A935142 (407), have both “type 1” and “type 2” characteristics. As activators bind hERG at various locations within the channel, efforts to correlate binding location and channel stoichiometry with mechanism of hERG activation by small molecule compounds will aid the design of more selective and potent hERG channel activators by a variety of mechanisms (476).

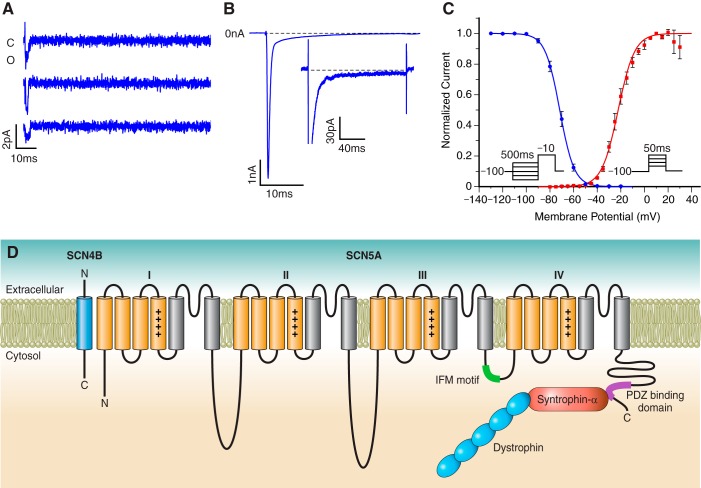

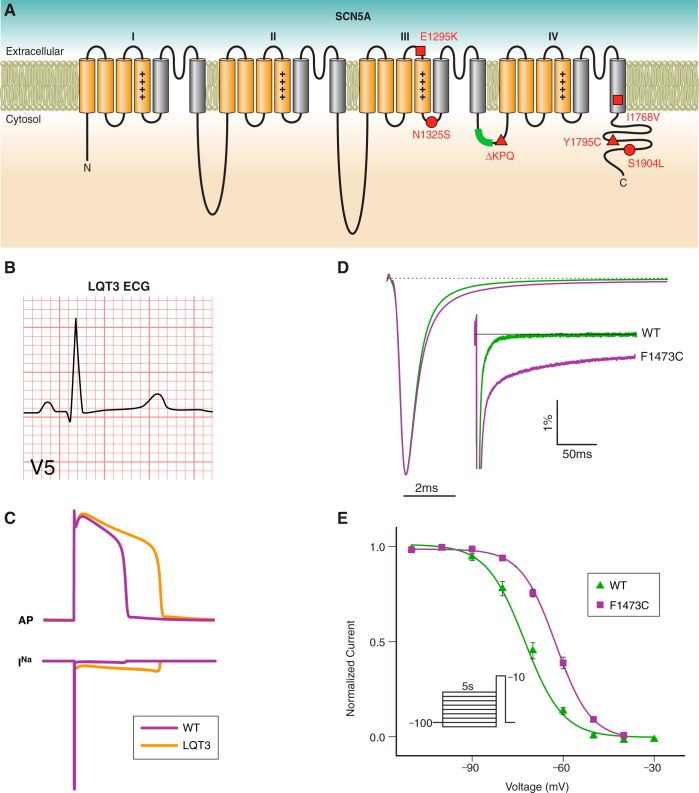

IV. INA DYSFUNCTION IN CONGENITAL LQTS

A. Introduction