This population-based study estimates the incidence of facial trauma among elderly nursing home residents and details mechanisms of injury, injury characteristics, and patient demographic data.

Key Points

Question

What are the incidence and mechanism of injury of facial trauma injuries sustained in the elderly nursing home population?

Findings

The National Electronic Injury Surveillance System was used to calculate incidence and characteristics of facial trauma among nursing home residents. The most common injuries were lacerations and other soft-tissue injuries and fractures, with nasal and orbital fractures the most common sites of fracture and direct contact with structural housing elements or fixed items and transfer to and from bed the most common injury causes.

Meaning

Despite falls being considered a Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services preventable never event in hospitals, these injuries likely contribute substantially to health care expenditures and leave room for areas for intervention.

Abstract

Importance

As the nursing home population continues to increase, an understanding of preventable injuries becomes exceedingly important. Although other fall-related injuries have been characterized, little attention has been dedicated to facial trauma.

Objectives

To estimate the incidence of facial trauma among nursing home residents and detail mechanisms of injury, injury characteristics, and patient demographic data.

Design, Setting, and Participants

The National Electronic Injury Surveillance System was used to calculate a weighted national incidence of facial trauma among individuals older than 60 years from a nationally representative collection of emergency departments from January 1, 2011, through December 31, 2015. Entries were screened for nursing home residents, and diagnosis, anatomical site, demographic data, and mechanism of injury were analyzed.

Results

There were 109 795 nursing home residents (median age, 84.1 years; interquartile range, 79-89 years; 71 466 women [65.1%]) who required emergency department care for facial trauma. Women sustained a greater proportion of injuries with increasing age. The most common injuries were lacerations (48 679 [44.3%]), other soft-tissue injuries (45 911 [41.8%]; avulsions, contusions, and hematomas), and fractures (13 814 [12.6%]). Nasal (9331 [67.5%]) and orbital (1144 [8.3%]) fractures were the most common sites. The most common injury causes were direct contact with structural housing elements or fixed items (62 604 [57.0%]) and transfer to and from bed (24 870 [22.6%]).

Conclusions and Relevance

Despite falls being considered a Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services preventable never event in hospitals, our analysis in the nursing home setting found more than 100 000 facial injuries during 5 years, suggesting these underappreciated injuries contribute substantially to health care expenditures. Although structural elements facilitated the greatest number of falls, transfer to and from bed remains a significant mechanism, suggesting an area for intervention.

Introduction

A significant number of elderly Americans reside in skilled nursing facilities, with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimating 1.4 million residents in 2014. As this number continues to rapidly increase in light of our aging population, an understanding of the clinical issues that affect nursing home residents is critical for physicians involved in the care of these patients, other health care professionals, administrators, and policy makers; consequently, population-based analysis estimating the incidence and characteristics of specific injuries carries a wide variety of implications that affect health care delivery. Furthermore, in light of evolving reimbursement practices and our changing health care environment, identifying the extent to which preventable injuries are sustained has never been more important.

Concomitant with our increasing nursing home population, there has been widespread inquiry into preventable injuries, including fall-related head trauma, hip and extremity fractures, and other fall-related sequelae, in recent years. Fall-related injury overall among the elderly population facilitates decreased independence, ultimately diminishing quality of life and costing society more than $60 billion annually. Nonetheless, there has been little analysis on nursing home–related facial trauma, despite the devastating consequences that such injury harbors, including a potential effect on speech, swallowing, sight, and other functional considerations. Our primary objectives entailed evaluating a nationally based resource to estimate a national incidence of nursing home–related facial trauma and further describing specific injuries, mechanisms of injury, and patient demographic data. Because facial trauma among this population has not been comprehensively evaluated and facial trauma in the elderly population in general represents an understudied and underrecognized entity, this information fills a void in the literature and may be valuable for patient education and for primary care physicians, geriatricians, physicians involved in the management of facial trauma, health care professionals, and policy makers.

Methods

The National Electronic Injury Surveillance System (NEISS) is a publicly available database offered through the Consumer Product Safety Commission. This resource uses a nationally representative collection of emergency departments (EDs) to provide estimates on injury incidence and demographic data. The NEISS has demonstrated its unique nationally representative value for a variety of clinical issues. The NEISS database is publicly available and qualifies as nonhuman subject research. Therefore, institutional review board approval was not required. All data entries are deidentified in the NEISS database; therefore, informed consent was not obtained.

Using methods suggested by Thompson et al for the use of the NEISS in reporting accurate injury trends, we used the NEISS database to collect data on all facial injuries among patients 60 years and older from the most recent 5-year period available, January 1, 2011, through December 31, 2015. Injury entries contain a text narrative, each of which was screened for mention of injury while at a nursing home or skilled nursing facility, and irrelevant entries were eliminated.

The NEISS can provide national incidence estimates based on grouped and weighted data, which are included in our analysis. After collection and weighting, data were reviewed for sex, injury type, and location of any fractures incurred. Items associated with each injury were also recorded and grouped into meaningful categories for further classification of cause of injury.

Two-sided analyses of variance were used for comparison of continuous variables as appropriate, with the threshold for significance set at P < .05. SAS statistical software (SAS Institute Inc) was used for weighing and statistical analysis.

Results

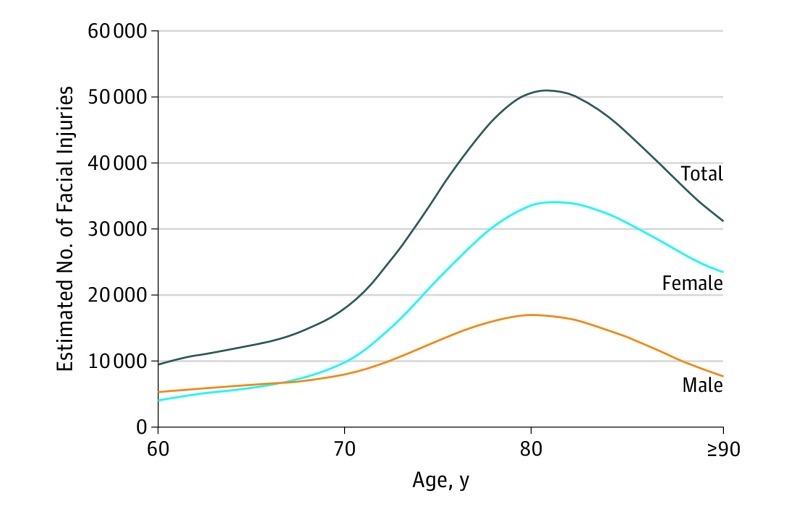

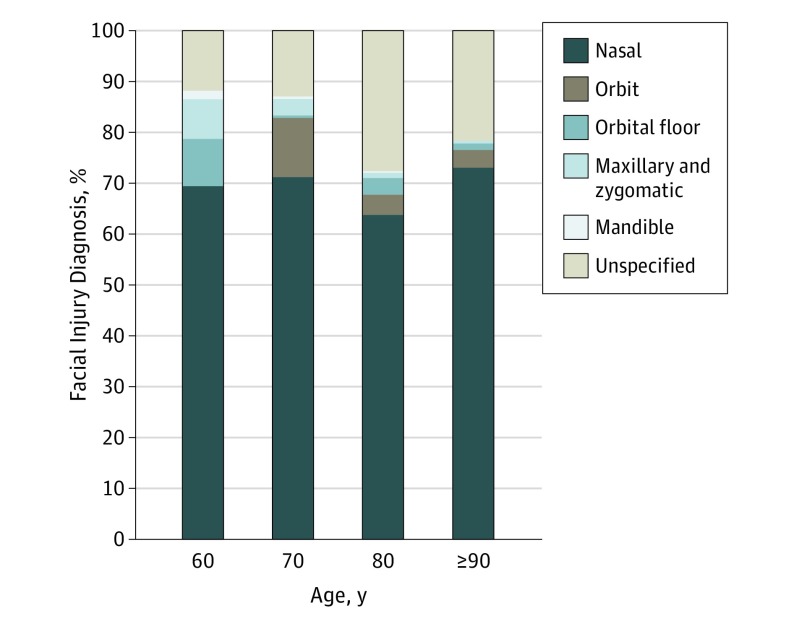

There were 109 795 nursing home residents (median age, 84.1 years; interquartile range, 79-89 years; 71 466 women [65.1%]) who required emergency department care for facial trauma, with a mean of 21 959 facial injuries per year. Although men and women in their 60s have relatively equal numbers of facial injuries, Figure 1 shows that as patients age, an increased number of these injuries occur in females. Furthermore, of all facial injuries sustained in nursing home patients, most are lacerations (48 679 [44.3%]) and other soft-tissue injuries (45 911 [41.8%]), such as hematomas (7220 [6.8%]), avulsions (495 [34.5%]), and contusions (37 912 [34.5%]). There are an estimated mean 2727 facial fractures in nursing home patients in the United States every year. Fractures comprise 13 814 (12.6%) of all facial trauma occurring at these facilities. Figure 2 shows the proportion of facial injuries in each 10-year age group organized by diagnosis; no significant difference was found in the proportion of injuries diagnosed to be facial fractures by decade.

Figure 1. Estimated US Incidence of Elderly Nursing Home Facial Injuries per 10-Year Age Group.

Figure 2. Facial Injury Diagnosis per 10-Year Age Group.

Fractions less than 0.2 are not shown.

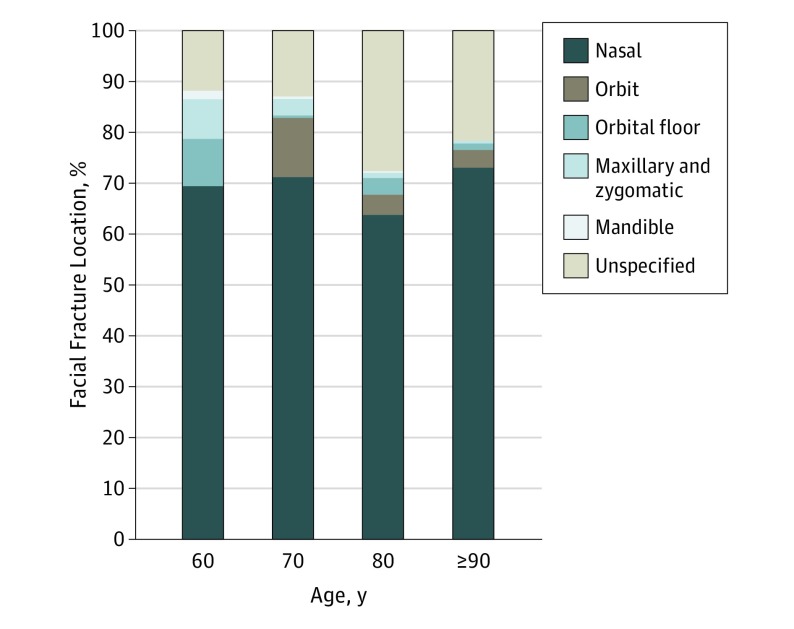

Most facial fractures in the elderly nursing home population were of the nasal bones (9331 [67.5%]), followed by orbital fractures (1144 [8.3%]) and maxillary and zygomatic fractures (306 [2.2%]) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Facial Fracture Location per 10-Year Age Group.

Fractions less than 0.2 are not shown.

As summarized in the Table, of all fractures sustained by elderly patients while at nursing homes, most were caused by direct contact with structural building elements or fixed household items (62 604 [57.0%]), such as the floor, walls, countertops, doors, and cabinets. A large number of fractures occurred from contact with other common items, such as beds and bedframes (24 870 [22.6%]), and various other household items, such as furniture (12 100 [11.0%]). Injuries related to heating, ventilation, and air-conditioning equipment (422 [0.4%]) refer to injuries caused by direct contact with objects, such as radiators, air-conditioner units, and vents. Bathroom-related falls comprised only 4012 fractures (3.6%) in the elderly nursing home population.

Table. Estimation of Facial Fractures Caused by Direct Contact With Various Nursing Home Items.

| Mechanism | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Floor or fixed items | 62 604 (57.0) |

| Bed | 24 870 (22.6) |

| House items or furniture | 12 100 (11.0) |

| Bathroom | 4012 (3.6) |

| Recreation | 3224 (2.9) |

| Clothing | 2135 (1.9) |

| HVAC equipment | 422 (0.4) |

| Kitchen | 295 (0.3) |

| Scooter | 132 (0.1) |

| Total | 109 795 (100) |

Abbreviation: HVAC, heating, ventilation, and air-conditioning.

Discussion

Although falls have been recognized as a significant clinical issue among the nursing home population, no population-based analysis has specifically evaluated facial trauma in this setting. In filling this void in the literature, our analysis notes nearly 110 000 ED visits for these injuries during a recent 5-year period, suggesting this is an underappreciated and underrecognized clinical entity that contributes a substantial amount of costs to our health care system. Most facial injuries occurred from direct contact with housing structural elements or fixed items (Table), suggesting that taking steps to educate patients, families, and nursing home staff about fall prevention measures remains an unmet clinical need. The National Institute on Aging offers myriad resources on injury prevention (nihseniorhealth.gov), including tips for fall proofing, and many of these suggestions may need to be extended to skilled nursing facilities. Furthermore, public health agencies, such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, have emphasized the importance of physical activity and exercise among older adults in recent years; in light of this campaign and in conjunction with our increasingly aging population, the profile and incidence of facial injuries may change significantly in coming years, making the development of further strategies for facial injury prevention an urgent clinical necessity.

A movement to minimize preventable events in hospitals has played a leading role in recent health care reform efforts. In 2008, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services defined never events, conditions for which hospitals would not receive reimbursement for managing. These never events include preventable hospital-acquired conditions, such as pressure ulcers, vascular catheter–associated injury, catheter-associated urinary tract infection, and, notably, sequelae from falls and trauma. In 2012, physician reviewers from the US Department of Health and Human Services retrospectively examined medical records from skilled nursing facilities, finding that 59% of adverse events were “clearly or likely preventable.”(p 25) Thus, the policy of withholding reimbursement for management of these never events from hospitals will likely eventually affect additional settings (such as nursing homes) and individual practitioners. Consequently, understanding the incidence and extent to which these events affect our health care system becomes increasingly important.

Increased propensity for hip and extremity fractures has been a long-recognized consequence of age-related bone remodeling and osteoporosis. A recent analysis evaluating an extrapolated 1.4 million adult ED visits noted an increased incidence of facial fracture with aging, particularly among postmenopausal white women. Nonetheless, although there has been widespread evaluation on the societal effect and individual prevention strategies when it comes to traumatic head injuries, fractured extremities, and hip trauma, little attention has been paid to the role of facial trauma among the elderly population. Facial trauma carries profound sequelae facilitating functional deficits relating to speech, swallowing, and sight, all of which may already be compromised among those requiring nursing home placement. Thus, because this concern has been largely neglected in the literature, characterization of facial injury patterns among the elderly population, including the extent to which this affects our health care system, may be exceedingly invaluable for primary care physicians, geriatricians, emergency physicians, and surgeons involved in the management of facial trauma and public health officials involved in policy decisions. A recent comparative analysis on elderly traumatic brain injury and craniofacial trauma stemming from bathroom-related falls noted that there were more than 3 million ED visits during a recent 5-year period for such injuries, with toilet transfer playing a significant role. Several suggestions for improvement were offered for prevention of these injuries; although this aforementioned study offers valuable lessons, only 3.6% of facial injuries in the present analysis occurred in the bathroom setting, emphasizing important differences in mechanism of injury on comparison of older adults who live independently compared with those who reside in nursing homes (Table).

Although comprising only 12.6% of injuries (Figure 2), facial fractures engender serious sequelae and can often have a significant effect on function and quality of life. As in other settings, most nursing home–related facial fractures were to the nose. In addition to educating primary care physicians, geriatricians, and other physicians involved in the care of these patients about the appropriate examination of a suspected nasal fracture (which should not routinely include imaging), several other notable trends are demonstrated. Of importance, orbital injuries comprised 8.3% of fractures. Because orbital trauma comprises a low proportion of injury in this patient population, these data suggest that computed tomography should not be routinely performed to evaluate for this unless there are clear concerns and findings that raise the index of suspicion for orbital fractures, including significant extraocular movement restriction outside the context of significant swelling, changes in visual acuity and visual fields, or poor pupillary responsiveness (Figure 3). However, this recommendation would benefit from a complementary study that specifically addresses such questions. Also of note is that less than 2% of fractures involved the mandible, a lower figure than reported in analyses among non–nursing home cohorts and younger patients. The reason for this finding, although speculative, is likely related to the mechanisms of injury noted in this population (Table). Of note, mandible fractures often require greater acceleration forces than injuries in some other common locations, such as nasal fractures; because much of the patient population in the present study has limited mobility compared with a more independent cohort, we noted largely low-velocity mechanisms of injury.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first focused analysis to estimate a national incidence of facial trauma occurring in nursing homes. In addition to educating patients, family members, and nursing home staff about the extent of this problem, primary care physicians and practitioners involved in the management of facial trauma harbor a responsibility to discuss potential preventive measures. Increased nursing home falls have been noted among patients immediately after relocation to a new facility. This finding emphasizes the importance of increased supervision of this patient population as 1 means of fall prevention. Our analysis revealed that transfers to and from beds comprised a significant proportion of facial fractures (22.7%) (Table), suggesting this process as an important area for targeted intervention and patient education. Bed alarms have been suggested as 1 strategy for prevention of bed transfer–related falls; however, a previous study found that although they can play an important potential role, they are not a sufficient substitute for adequate staffing and supervision. Another study noted that bed height is an important predictor for falls among nursing home residents, positing this as something that should be addressed.

Strengths and Limitations

As the first focused analysis estimating the extent to which facial trauma is a significant clinical issue among our increasing nursing home population, findings from this analysis potentially serve as a wake-up call on the need for further inquiry into injury prevention. Particularly in this current environment characterized by increasing recognition of the costs of care related to preventable injury, we believe these findings to be timely from the perspective of patient education and for practitioners involved in the treatment of these patients. Nonetheless, our analysis has several inherent limitations. Population-based resources, such as the NEISS, offer an important opportunity to look at a large number of patients in varying settings, lending greater external validity to our findings. However, the NEISS is not ideal for examining patient management and outcomes and thus is most useful as a complement to intrainstitutional analyses that may possess a smaller number of patients but more clinical details. In addition, the trends discussed are only as good as the data inputted; therefore, the designation nursing home may not always have referred to skilled nursing facilities, and there is a chance that some entries may have included patients in other types of settings, including assisted living facilities. During our original search, we noted numerous entries that specifically differentiated between assisted nursing facilities (not included in our sample), rehabilitation facilities (not included in our sample), and other types of settings. We included only entries that specifically referred to nursing home(s) and skilled nursing facilities in this analysis. Furthermore, it is possible that in the context of more severe trauma injuries, such as hip fractures or intracranial hemorrhage, the NEISS reporting personnel may fail to input secondary diagnoses, such as relatively minor facial injuries, which lends a possibility of underreporting of facial trauma in the elderly nursing home population.

Conclusions

Although falls have been recognized as a significant clinical issue among the elderly nursing home population, little attention has been paid to facial trauma in this setting. Our analysis revealed more than 100 000 facial injuries that required emergency care during a 5-year period; this figure suggests that this underappreciated occurrence contributes substantially to costs, particularly in this health care environment characterized by increasing recognition of preventable never events. Although housing structural elements facilitated the greatest number of falls, transfer to and from bed remained a significant mechanism of injury, suggesting an important area for targeted intervention.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Nursing Home Care. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/nursing-home-care.htm. Accessed August 1, 2016.

- 2.Rubenstein LZ, Josephson KR, Robbins AS. Falls in the nursing home. Ann Intern Med. 1994;121(6):442-451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thapa PB, Brockman KG, Gideon P, Fought RL, Ray WA. Injurious falls in nonambulatory nursing home residents: a comparative study of circumstances, incidence, and risk factors. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44(3):273-278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thompson HJ, McCormick WC, Kagan SH. Traumatic brain injury in older adults: epidemiology, outcomes, and future implications. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(10):1590-1595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vu MQ, Weintraub N, Rubenstein LZ. Falls in the nursing home: are they preventable? J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2004;5(6):401-406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System. http://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/. Accessed March 1, 2016.

- 7.Chen X, Milkovich S, Stool D, van As AB, Reilly J, Rider G. Pediatric coin ingestion and aspiration. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2006;70(2):325-329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baugh TP, Hadley JB, Chang CW. Epidemiology of wire-bristle grill brush injury in the United States, 2002-2014. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016;154(4):645-649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Umstattd LA, Chang CW. Pediatric oral electrical burns: incidence of emergency department visits in the United States, 1997-2012. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016;155(1):94-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walls A, Pierce M, Wang H, Harley EH Jr. Clothing hanger injuries: pediatric head and neck traumas in the United States, 2002-2012. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;150(2):300-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Svider PF, Sheyn A, Folbe E, et al. How did that get there? a population-based analysis of nasal foreign bodies. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2014;4(11):944-949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heilbronn CM, Svider PF, Folbe AJ, et al. Burns in the head and neck: a national representative analysis of emergency department visits. Laryngoscope. 2015;125(7):1573-1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shaigany K, Abrol A, Svider PF, et al. Recreational motor vehicle use and facial trauma. Laryngoscope. 2016;126(1):67-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Svider PF, Vong A, Sheyn A, et al. What are we putting in our ears? a consumer product analysis of aural foreign bodies. Laryngoscope. 2015;125(3):709-714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Svider PF, Bobian M, Hojjat H, et al. A chilling reminder: pediatric facial trauma from recreational winter activities. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;87:78-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hanba C, Gupta A, Svider PF, et al. Forgetful but not forgotten: Bathroom-related craniofacial trauma among the elderly [published online July 14, 2016]. Laryngoscope. 2016. doi: 10.1002/lary.26111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hanba C, Svider PF, Chen FS, et al. Race and sex differences in adult facial fracture risk. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2016;18(6):441-448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Watson DS, Shields BJ, Smith GA. Trimming- and pruning-related injuries in the United States, 1990 to 2007. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;72(1):257-262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lowell G, Quinlan K. Not child’s play: national estimates of microwave-related burn injuries among young children. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2016;81(4)(suppl 1):S20-S24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shah NS, Buzas D, Zinberg EM. Epidemiologic dynamics contributing to pediatric wrist fractures in the United States. Hand (N Y). 2015;10(2):266-271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Loder RT. The demographics of equestrian-related injuries in the United States: injury patterns, orthopedic specific injuries, and avenues for injury prevention. J Trauma. 2008;65(2):447-460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hostetler SG, Xiang H, Smith GA. Characteristics of ice hockey-related injuries treated in US emergency departments, 2001-2002. Pediatrics. 2004;114(6):e661-e666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith GA. Injuries to children in the United States related to trampolines, 1990-1995: a national epidemic. Pediatrics. 1998;101(3, pt 1):406-412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leininger RE, Knox CL, Comstock RD. Epidemiology of 1.6 million pediatric soccer-related injuries presenting to US emergency departments from 1990 to 2003. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(2):288-293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thompson MC, Wheeler KK, Shi J, Smith GA, Xiang H. An evaluation of comparability between NEISS and ICD-9-CM injury coding. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e92052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention How Much Physical Activity Do Older Adults Need? http://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/basics/older_adults/. Accessed August 1, 2016.

- 27.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Federal Policy Guidance [letter]. https://www.medicaid.gov/federal-policy-guidance/federal-policy-guidance.html. Accessed August 1, 2016.

- 28.Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Inspector General Adverse Events in Skilled Nursing Facilities: National Incidence Among Medicare Beneficiaries, 2014. https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-06-11-00370.pdf. Accessed August 1, 2016.

- 29.Cauley JA. Defining ethnic and racial differences in osteoporosis and fragility fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(7):1891-1899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sambrook P, Cooper C. Osteoporosis. Lancet. 2006;367(9527):2010-2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cranney A, Jamal SA, Tsang JF, Josse RG, Leslie WD. Low bone mineral density and fracture burden in postmenopausal women. CMAJ. 2007;177(6):575-580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hans D, Goertzen AL, Krieg MA, Leslie WD. Bone microarchitecture assessed by TBS predicts osteoporotic fractures independent of bone density: the Manitoba study. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26(11):2762-2769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jou HJ, Yeh PS, Wu SC, Lu YM. Ultradistal and distal forearm bone mineral density in postmenopausal women. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2003;82(2):199-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kanis JA, Borgstrom F, De Laet C, et al. Assessment of fracture risk. Osteoporos Int. 2005;16(6):581-589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hojjat H, Svider PF, Lin HS, et al. Adding injury to insult: a national analysis of combat sport-related facial injury. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2016;125(8):652-659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lawrence LA, Svider PF, Raza SN, Zuliani G, Carron MA, Folbe AJ. Hockey-related facial injuries: a population-based analysis. Laryngoscope. 2015;125(3):589-593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Friedman SM, Williamson JD, Lee BH, Ankrom MA, Ryan SD, Denman SJ. Increased fall rates in nursing home residents after relocation to a new facility. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1995;43(11):1237-1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Capezuti E, Brush BL, Lane S, Rabinowitz HU, Secic M. Bed-exit alarm effectiveness. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2009;49(1):27-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Capezuti E, Wagner L, Brush BL, Boltz M, Renz S, Secic M. Bed and toilet height as potential environmental risk factors. Clin Nurs Res. 2008;17(1):50-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]