Abstract

Objectives To review randomised controlled trials of treatment with a proton pump inhibitor in patients with ulcer bleeding and determine the impact on mortality, rebleeding, and surgical intervention.

Design Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Data sources Cochrane Collaboration's trials register, Medline, and Embase, handsearched abstracts, and pharmaceutical companies.

Review methods Included randomised controlled trials compared proton pump inhibitor with placebo or H2 receptor antagonist in endoscopically proved bleeding ulcer and reported at least one of mortality, rebleeding, or surgical intervention. Trials were graded for methodological quality. Two assessors independently reviewed each trial, and disagreements were resolved by consensus.

Results We included 21 randomised controlled trials comprising 2915 patients. Proton pump inhibitor treatment had no significant effect on mortality (odds ratio 1.11, 95% confidence interval 0.79 to 1.57; number needed to treat (NNT) incalculable) but reduced rebleeding (0.46, 0.33 to 0.64; NNT 12) and surgery (0.59, 0.46 to 0.76; NNT 20). Results were similar when the meta-analysis was restricted to the 10 trials with the highest methodological quality: 0.96, 0.46 to 2.01, for mortality; 0.41, 0.25 to 0.68, NNT 10, for rebleeding; 0.62, 0.46 to 0.83, NNT 25, for surgery.

Conclusions Treatment with a proton pump inhibitor reduces the risk of rebleeding and the requirement for surgery after ulcer bleeding but has no benefit on overall mortality.

Introduction

Peptic ulcers are the main cause of upper gastrointestinal bleeding,1,2 which is associated with considerable morbidity and mortality. Endoscopic findings that predict rebleeding, surgical intervention, and death include active arterial bleeding, oozing of blood, or a non-bleeding visible vessel.3 Patients with an adherent clot in the base of the ulcer are at lower risk.4,5 A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials of various forms of endoscopic haemostatic therapy for ulcer bleeding showed significant reductions in rebleeding, surgical intervention, and mortality among patients with important findings on endoscopy.6

The role of treatment with proton pump inhibitors for patients with active or recent ulcer bleeding is controversial. If given in an adequate dose by continuous intravenous infusion, proton pump inhibitors can maintain intragastric pH at 6 or above.7,8 At those levels of pH, peptic activity is minimised, platelet function is optimised, and fibrinolysis is inhibited; these effects should help to stabilise clot formation over an ulcer. Although proton pump inhibitors are already widely used for ulcer bleeding,9,10 intravenous therapy may have been overused and given inappropriately for patients at low risk.11,12 We systematically reviewed the published literature and analysed the results by meta-analysis to define the contribution of proton pump inhibitors to the management of ulcer bleeding.

Methods

We performed a computerised literature search up to February 2003 of Medline, Embase, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, and the specialised trials register of the Cochrane Upper Gastrointestinal and Pancreatic Diseases Group. We also handsearched articles for additional citations, reviewed the proceedings of major conferences up to February 2003, and contacted pharmaceutical companies that marketed proton pump inhibitors. For data available only in abstract form, we contacted original authors when necessary.

We included randomised controlled trials that compared a proton pump inhibitor with placebo or an H2 receptor antagonist for treating ulcer bleeding. Bleeding had to have been confirmed endoscopically, and trials had to have reported at least one of mortality, rebleeding, or surgery. Our primary outcome measure was mortality within 30 days of randomisation. Secondary outcomes measures included recurrent ulcer bleeding and surgery for ulcer bleeding within 30 days of randomisation. Two reviewers independently checked each identified trial and determined inclusion and grading of methodological quality, which depended on concealment of allocation (grade A = adequate; grade B = uncertain; grade C = inadequate; grade D = not randomised); disagreements were resolved by consensus. Data were extracted on the method of randomisation; inclusion and exclusion criteria; details of all therapeutic interventions, including the dose and delivery method and control treatment; duration of treatment; and any cointerventions including endoscopic haemostatic therapy. We also extracted mean age or age range; sex ratio; ethnicity; numbers assigned to each treatment group; numbers with comorbid conditions; baseline comparison of treatment groups with respect to site of bleeding ulcer (that is, duodenal or gastric) and signs of recent haemorrhage (spurting, oozing, non-bleeding visible vessel, and adherent clot); degree of blinding of assessors of outcomes, patients, and investigators; numbers of patients withdrawn with reasons; outcomes reported according to source of haemorrhage at initial endoscopy; and any adverse reactions to treatment.

We performed meta-analysis of outcomes as appropriate by combining trials by the Mantel-Haenszel method (RevMan, version 4.2.2). Statistical heterogeneity was evaluated, and P < 0.1 was considered significant. Primary and secondary outcomes were summarised as odds ratio and 95% confidence intervals. We used a fixed effect model unless there was significant heterogeneity, in which case we applied a random effects model. We also derived pooled values for number needed to treat.

Using predetermined sensitivity analyses, we examined the influence of the degree of study validity, the type of control treatment, the initial use of endoscopic haemostatic therapy, the site of ulcer, the presence of signs of recent haemorrhage at the initial endoscopy, restriction of the analysis to trials using intravenous (as opposed to oral) proton pump inhibitors, and restriction of the analysis to trials that had used a high intravenous dose. Our predetermined definition of “high dose” was the equivalent of omeprazole as an intravenous bolus of 80 mg followed by a continuous intravenous infusion of 8 mg/hour for 72 hours.

Results

We initially identified 172 articles. Of these, we excluded 151 because they were not randomised controlled trials, the control group received neither placebo nor H2 receptor antagonist, they reported only pH data, they were abstracts of subsequently published randomised controlled trials, duplicate publication, it was not possible to isolate outcome data for patients with ulcer bleeding, or they did not report any of our predetermined outcomes. Contact with pharmaceutical companies in Europe and North America provided no additional data. Twenty one trials met our predefined inclusion criteria,13-33 18 were full peer reviewed publications,13-30 and three were abstracts.31-33 The funnel plots for the three outcomes of interest show slight asymmetry, suggesting the possibility of publication bias (fig 1). Table 1 summarises the characteristics of the trials, and table 2 summarises the main results. Treatment with proton pump inhibitors was associated with reduced rebleeding and surgery but not with mortality. Figures 2, 3, and 4 show the forest plots for the three outcome measures.

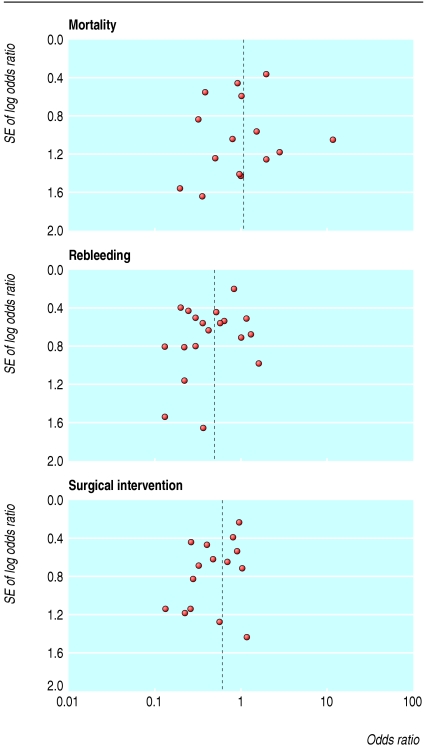

Fig 1.

Funnel plots of included trials for mortality, rebleeding, and surgical intervention rates

Table 1.

Summary of randomised controlled trials included in review of proton pump inhibitors in treatment of bleeding ulcers

|

Treatments

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Design | No of patients | Endoscopic signs | Proton pump inhibitor | Control | Outcomes reported | Comments | |

| Brunner13 Germany | Single centre, open, randomised after endoscopy | 39 | Oozing | Omeprazole IV bolus | Ranitidine IV bolus + infusion | Mortality, surgery | 19 were inpatients at time of bleed; 49% had gastric ulcer; no initial endoscopic haemostatic therapy |

| Daneshmend14 UK | Two centre, double blind, randomised before endoscopy | 503* | Excluded severe bleeding requiring surgery | Omeprazole IV bolus then orally | Placebo | Mortality, rebleeding, surgery | Excluded inpatients developing bleeding |

| Michel15 France | Multicentre, double blind | 75 | Spurting, oozing, NBVV, adherent clot | Oral lansoprazole | Oral ranitidine | Mortality, rebleeding, surgery | Timing of randomisation unclear |

| Perez-Flores16 Spain | Single centre, open | 81 | Oozing, NBVV, adherent clot | Omeprazole IV bolus then orally | Ranitidine IV bolus then orally | Mortality, rebleeding, surgery | Timing of randomisation unclear; not all high risk patients received endoscopic haemostatic therapy |

| Lanas17 Spain | Single centre, open, randomised after endoscopy | 51 | Oozing, NBVV, adherent clot | Omeprazole IV bolus | Ranitidine IV bolus | Mortality, rebleeding, surgery | No initial endoscopic haemostatic therapy |

| Villanueva18 Spain | Single centre, open, randomised after endoscopy | 86 | Spurting, oozing | Omeprazole IV bolus then orally | Ranitidine IV bolus then orally | Mortality, rebleeding, surgery | 16% had onset of bleeding as inpatient |

| Cardi19 Italy | Single centre, randomised after endoscopy | 45 | Oozing | Omeprazole IV bolus + infusion | Ranitidine IV bolus + infusion | Mortality, surgery | Level of blinding unclear; all patients had duodenal ulcer; no apparent initial endoscopic haemostatic therapy |

| Hasselgren20 Sweden, Norway | Multicentre, double blind, randomised after endoscopy | 322 | Spurting, oozing, NBVV, adherent clot | Omeprazole IV bolus + infusion | Placebo IV bolus + infusion | Mortality, surgery | Trial stopped prematurely because of concerns over higher mortality in proton pump inhibitor than control group; only patients aged >60 included; not all high risk patients received endoscopic haemostatic therapy |

| Khuroo21 India | Single centre, double blind, randomised after endoscopy | 220 | Spurting, oozing, NBVV, adherent clot | Oral omeprazole | Oral placebo | Mortality, rebleeding, surgery | No routine endoscopic haemostatic therapy; excluded patients with severe bleeding or terminal illness |

| Labenz22 Germany | Single centre, randomised after endoscopy | 40 | Spurting, oozing, NBVV, adherent clot | Omeprazole IV bolus + infusion | Ranitidine IV bolus + infusion | Rebleeding (within 24 hours) | Degree of blinding unclear |

| Lin23 Taiwan | Single centre, open, randomised after endoscopy | 52 | NBVV | Omeprazole IV bolus | Cimetidine IV bolus | Rebleeding | No initial endoscopic haemostatic therapy |

| De Muckadell24 Denmark, Holland, France | Multicentre, double blind, randomised after endoscopy | 265 | Spurting, oozing, NBVV, adherent clot | Omeprazole IV bolus + infusion | Placebo IV bolus + infusion | Mortality, surgery | Terminated prematurely after interim analysis pooled with parallel study (Hasselgren et al20) |

| Corragio25 Italy | Multicentre, randomised after endoscopy | 73 | Spurting, oozing, NBVV, adherent clot | Oral omeprazole | Ranitidine IV bolus | Mortality, rebleeding, surgery | Degree of blinding unclear |

| Lin26 Taiwan | Single centre, open, randomised after endoscopy | 100 | Spurting, oozing, NBVV | Omeprazole IV bolus + infusion | Cimetidine IV bolus + infusion | Mortality, rebleeding, surgery | — |

| Lau27 Hong Kong | Single centre, double blind, randomised after endoscopy | 240 | Spurting, oozing, NBVV | Omeprazole IV bolus + infusion | Placebo IV bolus + infusion | Mortality, rebleeding, surgery | — |

| Javid28 India | Single centre, double blind, randomised after endoscopy | 166 | Spurting, oozing, NBVV, adherent clot | Oral omeprazole | Oral placebo | Mortality, rebleeding, surgery | — |

| Sheu29 Taiwan | Single centre, randomised after endoscopy | 175 | Spurting, oozing, NBVV, adherent clot, clean base | Omeprazole IV bolus | Ranitidine IV bolus | Mortality, rebleeding, surgery | Degree of blinding unclear |

| Kaviani30 Iran | Two centre, double blind, randomised after endoscopy | 149 | Spurting, oozing, NBVV | Omeprazole IV bolus then orally | Placebo IV bolus then oral omeprazole | Mortality, rebleeding, surgery | — |

| Desprez31 France | Single centre, randomised after endoscopy | 76 | Oozing, NBVV, adherent clot | Omeprazole IV bolus then orally | Ranitidine IV bolus + infusion then orally | Mortality, rebleeding, surgery | Degree of blinding unclear; no apparent initial endoscopic haemostatic therapy; only available as abstract |

| Fried32 Switzerland, Germany | Multicentre, open, randomised after endoscopy | 113 | Spurting, oozing, NBVV, adherent clot | Pantoprazole IV bolus + infusion | Ranitidine IV bolus + infusion | Mortality, rebleeding | Only available as abstract |

| Duvnjak33 Croatia | Single centre, randomised after endoscopy | 62 | Spurting, oozing, NBVV, adherent clot | Pantoprazole IV bolus | Ranitidine IV bolus | Rebleeding | Only available as abstract; degree of blinding unclear |

NBVV=non-bleeding visible vessel.

503 patients had endoscopic confirmation of bleeding from peptic ulcer from total cohort of 1147 patients with upper gastointestinal tract bleeding.

Table 2.

Principal outcome measures in patients with ulcer bleeding according to treatment

|

No of patients

|

Pooled rates (%)

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome at 30 days after randomisation | No of trials | Proton pump inhibitor | Control | Heterogeneity (P value) | Proton pump inhibitor | Control | Odds ratio (95% CI) | Number needed to treat (95% CI) |

| Mortality | 18 | 1371 | 1403 | No (0.26) | 5.2 | 4.6 | 1.11 (0.79 to 1.57) | Not calculable |

| Rebleeding | 19 | 1408 | 1423 | Yes (0.05) | 10.6 | 18.7 | 0.46 (0.33 to 0.64) | 12 (8 to 25) |

| Surgical intervention | 17 | 1305 | 1336 | No (0.42) | 8.4 | 13.0 | 0.59 (0.46 to 0.76) | 20 (14 to 50) |

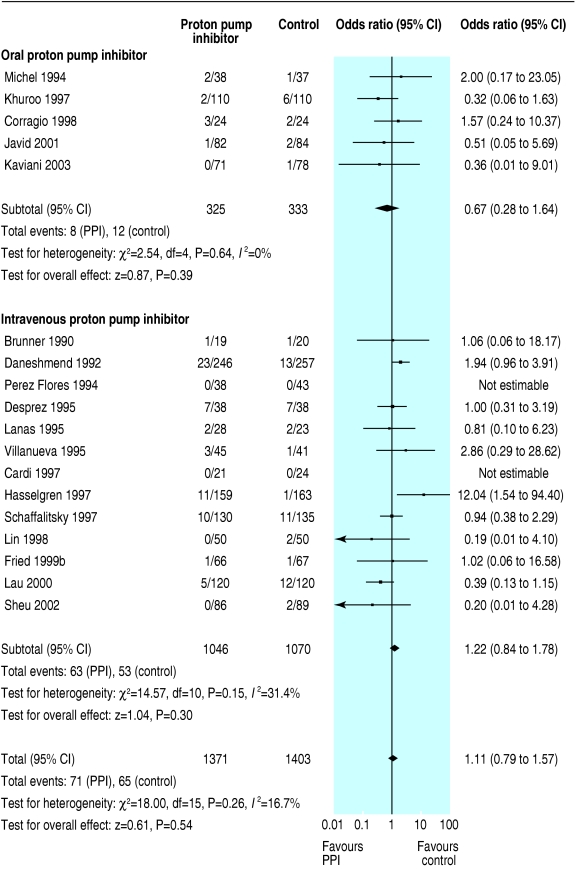

Fig 2.

Odds ratios for individual trials and pooled data for mortality, according to route of administration of proton pump inhibitor (PPI)

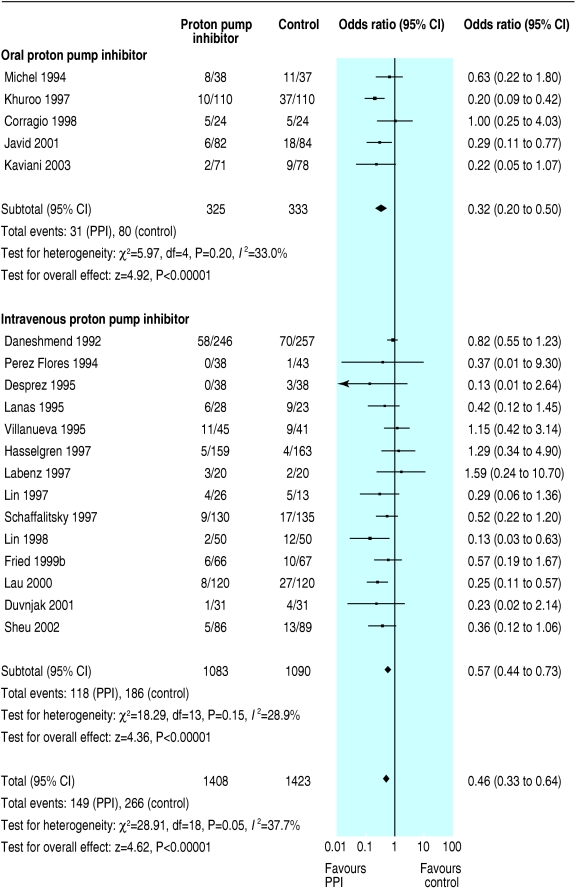

Fig 3.

Odds ratios for individual trials and pooled data for rebleeding, according to route of administration of proton pump inhibitor (PPI)

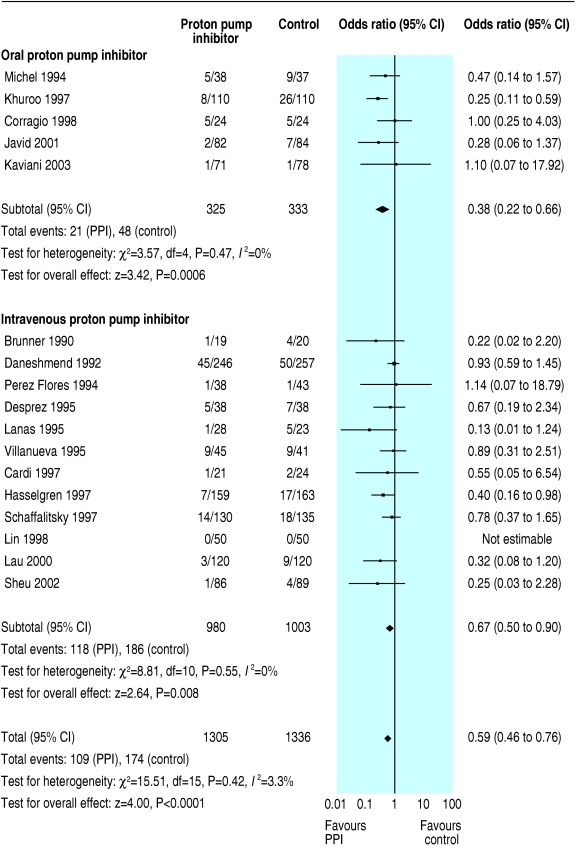

Fig 4.

Odds ratios for individual trials and pooled data for rates of surgical intervention, according to route of administration of proton pump inhibitor (PPI)

In a planned subgroup analysis of the 10 trials with grade A concealment of allocation we obtained essentially similar results; the odds ratios (95% confidence intervals) for mortality, rebleeding, and surgery were 0.96 (0.46 to 2.01), 0.41 (0.25 to 0.68), and 0.62 (0.45 to 0.83), respectively. We could not calculate number needed to treat for mortality. The number needed to treat for rebleeding and surgery was 10 (6 to 25) and 25 (14 to 50), respectively. In another subgroup analysis of the 13 trials that routinely used endoscopic haemostatic therapy before randomisation, the pooled odds ratios for mortality, rebleeding, and surgery were 1.01 (0.64 to 1.61), 0.52 (0.39 to 0.70), and 0.53 (0.35 to 0.79). Table 3 shows the results of this and other planned subgroup analyses according to the type of control treatment (placebo or H2 receptor antagonist), route of administration of proton pump inhibitor (intravenous or oral), and severity of ulcer bleeding.

Table 3.

Summary results of subgroup analyses in patients with ulcer bleeding

|

Pooled rates (%)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subgroup analyses and outcomes | PPI | Control | Heterogeneity (P value) | Odds ratio (95% CI) | Number needed to treat (95% CI) |

| H2 receptor antagonist as control (14 trials) | |||||

| Mortality | 4.2 | 4.2 | No (0.89) | 1.02 (0.51 to 2.05) | Not calculable |

| Rebleeding | 10.4 | 17.6 | No (0.51) | 0.53 (0.35 to 0.78) | 13 (8 to 25) |

| Surgical intervention | 7.9 | 11.1 | No (0.36) | 0.68 (0.38 to 1.20) | 25 (13 to 100) |

| Placebo as control (7 trials) | |||||

| Mortality | 5.7 | 4.9 | Yes (0.02) | 0.96 (0.43 to 2.15) | Not calculable |

| Rebleeding | 10.7 | 19.2 | Yes (0.005) | 0.41 (0.23 to 0.72) | 11 (8 to 20) |

| Surgical intervention | 8.7 | 13.5 | Yes (0.09) | 0.52 (0.32 to 0.84) | 20 (13 to 50) |

|

IV PPI versus IV placebo or IV H2 receptor antagonist (16 trials)

|

|

|

|

||

| Mortality | 6.0 | 5.0 | No (0.15) | 1.22 (0.84 to 1.78) | Not calculable |

| Rebleeding | 10.9 | 17.1 | No (0.15) | 0.57 (0.44 to 0.73) | 17 (11 to 25) |

| Surgical intervention | 9.0 | 12.6 | No (0.55) | 0.67 (0.50 to 0.90) | 25 (17 to 100) |

|

“High dose” IV PPI versus IV placebo or IV H2 receptor antagonist (4 trials)

|

|

|

|

||

| Mortality | 5.7 | 5.6 | Yes (0.02) | 0.98 (0.25 to 3.77) | Not calculable |

| Rebleeding | 5.2 | 12.8 | Yes (0.09) | 0.39 (0.18 to 0.87) | 11 (5 to 50) |

| Surgical intervention | 5.2 | 9.4 | No (0.36) | 0.53 (0.31 to 0.89) | 25 (14 to 100) |

|

IV PPI in doses other than “high dose” versus IV placebo or IV H2 receptor antagonist (12 trials)

|

|

|

|||

| Mortality | 6.3 | 4.5 | No (0.76) | 1.42 (0.85 to 2.38) | Not calculable |

| Rebleeding | 16.1 | 20.3 | No (0.53) | 0.67 (0.50 to 0.91) | 17 (10 to 100) |

| Surgical intervention | 12.3 | 15.3 | No (0.60) | 0.76 (0.53 to 1.08) | Not calculable |

|

Oral PPI treatment versus oral placebo or H2 receptor antagonist (5 trials)

|

|

|

|

||

| Mortality | 2.5 | 3.6 | No (0.64) | 0.67 (0.28 to 1.64) | Not calculable |

| Rebleeding | 9.5 | 24.0 | No (0.20) | 0.32 (0.20 to 0.50) | 7 (5 to 11) |

| Surgical intervention | 6.5 | 14.4 | No (0.47) | 0.38 (0.22 to 0.66) | 13 (8 to 25) |

|

Routine EHT before randomisation (13 trials)

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Mortality | 4.1 | 4.1 | No (0.24) | 1.01 (0.64 to 1.61) | Not calculable |

| Rebleeding | 8.6 | 15.0 | No (0.11) | 0.52 (0.39 to 0.70) | 14 (11 to 25) |

| Surgical intervention | 5.4 | 9.3 | No (0.73) | 0.53 (0.35 to 0.79) | 25 (14 to 50) |

|

No routine EHT before randomisation (8 trials)

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Mortality | 7.0 | 5.6 | No (0.34) | 1.25 (0.75 to 2.09) | Not calculable |

| Rebleeding | 16.0 | 25.8 | Yes (0.03) | 0.38 (0.18 to 0.81) | 9 (5 to 50) |

| Surgical intervention | 12.8 | 18.6 | No (0.16) | 0.64 (0.46 to 0.89) | 17 (10 to 50) |

|

Routine EHT before randomisation and use of high dose IV PPI treatment (4 trials)

|

|

|

|||

| Mortality | 5.7 | 5.6 | Yes (0.02) | 0.98 (0.25 to 3.77) | Not calculable |

| Rebleeding | 5.2 | 12.8 | Yes (0.09) | 0.39 (0.18 to 0.87) | 11 (8 to 33) |

| Surgical intervention | 5.2 | 9.4 | No (0.36) | 0.53 (0.31 to 0.89) | 25 (17 to 100) |

|

Routine EHT before randomisation and use of lower dose IV or oral PPI treatment (9 trials)

|

|

|

|||

| Mortality | 2.4 | 2.4 | No (0.80) | 1.00 (0.42 to 2.35) | Not calculable |

| Rebleeding | 10.2 | 17.2 | No (0.42) | 0.52 (0.35 to 0.78) | 14 (8 to 33) |

| Surgical intervention | 6.6 | 9.9 | No (0.71) | 0.59 (0.33 to 1.05) | Not calculable |

|

Endoscopic findings of active bleeding or NBVV before randomisation (10 trials)

|

|

|

|

||

| Mortality | 2.8 | 5.5 | No (0.79) | 0.51 (0.26 to 1.01) | Not calculable |

| Rebleeding | 10.5 | 24.7 | No (0.23) | 0.33 (0.22 to 0.50) | 7 (5 to 13) |

| Surgical intervention | 5.6 | 12.2 | No (0.69) | 0.39 (0.23 to 0.65) | 14 (10 to 33) |

|

Active bleeding or NBVV; routine EHT before randomisation (5 trials)

|

|

|

|

||

| Mortality | 2.7 | 5.2 | No (0.59) | 0.51 (0.23 to 1.12) | Not calculable |

| Rebleeding | 11.6 | 25.7 | Yes (0.09) | 0.35 (0.17 to 0.72) | 8 (6 to 17) |

| Surgical intervention | 4.5 | 7.3 | No (0.56) | 0.54 (0.27 to 1.08) | Not calculable |

|

Active bleeding or NBVV; without routine EHT before randomisation (5 trials)

|

|

|

|

||

| Mortality | 3.5 | 6.5 | No (0.57) | 0.51 (0.12 to 2.12) | Not calculable |

| Rebleeding | 19.4 | 46.8 | No (1.00) | 0.29 (0.13 to 0.63) | 4 (2 to 10) |

| Surgical intervention | 8.7 | 24.6 | No (0.81) | 0.27 (0.12 to 0.57) | 6 (4 to 14) |

PPI=proton pump inhibitor, IV=intravenous, EHT=endoscopic haemostatic therapy, NBVV=non-bleeding visible vessel.

Discussion

Proton pump inhibitors are widely used for patients with ulcer bleeding of varying severity,9-12 though it has not been specifically approved for that indication. Given the morbidity, mortality, and healthcare costs associated with bleeding peptic ulcer, it is important to establish definitively whether early treatment with proton pump inhibitors is associated with any meaningful clinical benefit. We deliberately focused on the use of proton pump inhibitors in patients with a proved diagnosis of ulcer bleeding and cannot, therefore, make any conclusions about use for managing other causes of upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding. Although one trial included patients with non-ulcer bleeding,14 we excluded those patients from our analysis. The other trials we included were confined to patients with a proved diagnosis. While we cannot exclude the possibility of some publication bias (see fig 1), our search was rigorous and we did not identify any other trials through contact with pharmaceutical companies.

We used odds ratios rather than absolute risk reduction as our pooled summary statistic. Though absolute risk reduction would have allowed the simple calculation of numbers needed to treat, a pooled number needed to treat derived from a meta-analysis of absolute risk differences can be misleading as baseline risk often varies considerably among included trials.34 We have, however, reported pooled number needed to treat for clinical applicability.

Overall, we found no evidence that treatment with proton pump inhibitors reduces mortality after ulcer bleeding. There were, however, significant reductions in rates of rebleeding and surgery. Much of the mortality after an episode of ulcer bleeding may be unrelated to continued or recurrent bleeding but to comorbid disease.35 Alternatively, there may have been too few patients in our pooled analysis of mortality data to enable us to detect a difference. The data are also compatible with treatment causing a small excess of deaths, which we consider unlikely on clinical grounds. In most trials, we could not determine whether deaths were attributable to comorbid conditions.

Some trials compared proton pump inhibitor therapy with placebo and others with an H2 receptor antagonist, though this is unlikely to have made any substantive difference in results. A meta-analysis by Collins and Langman,36 and its update by Levine and colleagues,37 found no benefit of intravenous H2 receptor antagonist over intravenous placebo in clinically important outcomes of bleeding duodenal ulcer and, at best, only small benefits in bleeding gastric ulcer.

This meta-analysis included randomised controlled trials of oral or intravenous proton pump inhibitor therapy; both methods of administration were associated with reduced rebleeding (table 3). Oral treatment is widely available and has the obvious advantage of costing less than intravenous administration. In areas of the world where intravenous treatment is unavailable or particularly expensive, oral treatment would be appropriate. Furthermore, it would be less costly for any patient with recent ulcer bleeding who did not require endoscopic haemostatic therapy.

Some trials of intravenous proton pump inhibitor treatment gave intermittent bolus injections, while others used a continuous infusion after a single intravenous bolus (table 1). These high dose regimens have been shown to maintain intragastric pH around 6.0.7,8 The continuous administration of proton pump inhibitor is not associated with the development of pharmacological tolerance, unlike continuous H2 receptor antagonist administration.38 Our predetermined subgroup analysis examining only those trials that had used such high doses found no significant reduction in mortality, but significant reductions in rebleeding and rates of surgery (table 3).

It was important to determine whether the addition of intravenous proton pump inhibitor therapy to appropriate endoscopic haemostatic therapy had any added benefit for those patients at the greatest risk. In our subgroup analysis of the trials that used endoscopic haemostatic therapy before randomisation we found no evidence for any effect on mortality, though there was a significant reduction in rebleeding. Of the trials that provided specific outcome data for patients with active arterial bleeding, oozing of blood, or a non-bleeding visible vessel, only five routinely incorporated some form of endoscopic haemostatic therapy before randomisation. In the five trials that did not routinely use endoscopic haemostatic therapy, proton pump inhibitor treatment was associated with significant reductions in rebleeding and surgical intervention but not in mortality. Failure to use endoscopic haemostatic therapy for such patients, however, would be considered as outside standard care. Proton pump inhibitor therapy is not an alternative to appropriate endoscopic haemostatic therapy, as shown in a trial from Hong Kong that randomised patients with bleeding ulcer and adherent clot or non-bleeding visible vessel to high dose intravenous omeprazole alone or to the combination of endoscopic haemostatic therapy and high dose intravenous omeprazole.39 Treatment with high dose intravenous omeprazole alone was associated with a significantly higher rate of rebleeding and a longer duration of hospital stay than combination therapy.

In summary, proton pump inhibitor treatment does not reduce mortality after ulcer bleeding, though it does reduce rates of rebleeding and, in general, the need for surgical intervention. This may be associated with important cost savings, which should be further evaluated in formal cost effectiveness studies.

What is already known on this topic

Proton pump inhibitors are effective for healing non-bleeding ulcers

Their role in the management of patients with bleeding ulcers is unclear

What this study adds

This systematic review and meta-analysis found that proton pump inhibitor treatment reduces the risk of ulcer rebleeding but does not influence overall mortality from ulcer bleeding

Requirement for surgery to manage ulcer bleeding is also likely to be reduced with early proton pump inhibitor treatment

Supplementary Material

Details of conference presentations, abstracts, and the Cochrane reference are on bmj.com

Details of conference presentations, abstracts, and the Cochrane reference are on bmj.com

We thank Iris Gordon, trial search coordinator, Cochrane Collaboration, Upper Gastrointestinal and Pancreatic Diseases Group, University of Leeds, for her help with the electronic literature search. We are grateful to Linda McIntyre for assistance with designing the protocol for this review and subsequent data extraction.

Contributors: GIL and CWH were involved in the composition and design of the systematic review and meta-analysis, the analysis and interpretation of the data, drafting of the article, critical revision of the article for intellectual content, final approval of the article, and collection and assembly of the data. VKS was involved in the composition and design of the systematic review and meta-analysis, critical revision of the article for intellectual content, final approval of the article, and assisted with the statistical analysis. CWH is guarantor.

Funding: There was no external funding for this work.

Competing interests: VKS has received research grants from TAP Pharmaceutical Products and speaking honorariums from AstraZeneca and TAP. CWH is a consultant for TAP Pharmaceutical Products, Santarus, and Schwarz Pharma; has received grant support from AstraZeneca, TAP, and Janssen; has been a trial investigator for AstraZeneca, TAP, and Merck; and has received speaking honorariums from TAP, Merck, AstraZeneca, Wyeth, and Novartis.

Ethical approval: Not required.

References

- 1.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. HCUP nationwide inpatient sample. Rock-ville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 1997.

- 2.Van Leerdam ME, Vreeburg EM, Rauws EAJ, Geraedts AAM, Tijssen JGP, Reitsma JB, et al. Acute upper GI bleeding: did anything change? Time trend analysis of incidence and outcome of acute upper GI bleeding between 1993/1994 and 2000. Am J Gastroenterol 2003;98: 1494-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laine L, Peterson WL. Bleeding peptic ulcer. N Engl J Med 1994;331: 717-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jensen DM, Kovacs TOG, Jutabha R, Machicado GA, Gralnek I, Savides TJ, et al. Randomized trial of medical or endoscopic therapy to prevent recurrent ulcer hemorrhage in patients with adherent clots. Gastroenterology 2002;123: 407-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laine L. Management of ulcers with adherent clots. Gastroenterology 2002;123: 632-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cook DJ, Salena B, Guyatt GH, Laine L. Endoscopic therapy for acute non-variceal upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage: a meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 1992;102: 139-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brunner G, Luna P, Hartmann M, Wurst W. Optimizing the intragastric pH as a supportive therapy in upper GI bleeding. YaleJBiolMed 1996;69: 225-31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Rensburg CJ, Thorpe A, Warren B, Venter JL, Theron I, Hartmann M, et al. Intragastric pH in patients with bleeding peptic ulceration during pantoprazole infusion of 8 mg/hour. Gut 1997;41(suppl 3): A98. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaplan GG, Bates D, McDonald D, Romagnuolo J. Inappropriate use of intravenous proton pump inhibitors: Problem extent and cost implications. Am J Gastroenterol 2002;97: S236. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chan EP, Goebig M, Demers RF, Katzka DA, Metz DC. Intravenous pantoprazole to prevent rebleeding after endoscopic hemostasis of bleeding ulcers: initial US experience [abstract]. Gastroenterology 2003;124: A626. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maimie I, Wiggins W, Thum T. Use of intravenous pantoprazole for the treatment of acute upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Gastrointest Endosc 2003;57: AB155. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Andrews C, Zandieh I, Levy A, Brodie M, Vivian M, Hahn M, et al. Comparison of IV PPI use between hospitals: preliminary results. Gastroenterology 2002;55: AB190. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brunner G, Chang J. Intravenous therapy with high doses of ranitidine and omeprazole in critically ill patients with bleeding peptic ulcerations of the upper gastrointestinal tract: an open randomized controlled study. Digestion 1990:45; 217-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Daneshmend TK, Hawkey CJ, Langman MJS, Logan RFA, Long RG, Walt RP. Omeprazole versus placebo for acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding: randomised double blind controlled study. BMJ 1992;304: 143-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Michel P, Duhamel C, Bazin B, Raoul J-L, Person B, Bigard MA, et al. Lansoprazole versus ranitidine dans la prévention des récidives précoces des hémorragies digestives ulcéreuses gastro-duodénales. Gastroenterol Clin Biol 1994;18: 1102-5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pérez Flores R, García Molinero MJ, Herrero Quirós C, Blasco Colmenarejo MM, Caneiro Alcubilla E, García-Rayo Somoza M, et al. Tratamiento de la hemorragia digestive alta de origen péptico: ranitidina intravenosa versus omeprazol intravenoso. Rev Esp Enf Digest 1994;86: 637-41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lanas A, Artal A, Blas JM, Arroyo MT, Lopez-Zaborras J, Sainz R. Effect of parenteral omeprazole and ranitidine on gastric pH and the outcome of bleeding peptic ulcer. J Clin Gastroenterol 1995;21: 103-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Villanueva C, Balanzo J, Torras X, Sainz S, Soriano G, Gonzalez D, et al. Omeprazole versus ranitidine as adjunct therapy to endoscopic injection in actively bleeding ulcers: a prospective and randomized study. Endoscopy 1995;27: 308-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cardi M, Muttillo IA, Amadori L, Barillari P, Sammartino P, Arnone F, et al. Omeprazole versus ranitidine intraveineux dans le traitement de l'ulcere duodenal hemorragique: une etude randomisee prospective. Ann Chir 1997:51; 136-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hasselgren G, Lind T, Lundell L, Aadland E, Efskind P, Falk A, et al. Continuous intravenous infusion of omeprazole in elderly patients with peptic ulcer bleeding. Results of a placebo-controlled multicenter study. Scand J Gastroenterol 1997;32: 328-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khuroo MS, Yattoo GN, Javid G, Khan BA, Shah AA, Gulzar GM, et al. A comparison of omeprazole and placebo for bleeding peptic ulcer. N Engl J Med 1997;336: 1054-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Labenz J, Peitz U, Leusing C, Tillenburg B, Blum AL, Borsch G. Efficacy of primed infusions with high dose ranitidine and omeprazole to maintain high intragastric pH in patients with peptic ulcer bleeding: a prospective randomised controlled study. Gut 1997;40: 36-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin HJ, Lo WC, Perng CL, Wang K, Lee FY. Can optimal acid suppression prevent rebleeding in peptic ulcer patients with a non-bleeding visible vessel: a preliminary report of a randomized comparative study. Hepatogastroenterology 1997;44: 1495-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schaffalitzky de Muckadell OB, Havelund T, Harling H, Boesby S, Snel P, Vreeburg EM, et al. Effect of omeprazole on the outcome of endoscopically treated bleeding peptic ulcers. Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled multicentre study. Scand J Gastroenterol 1997;32: 320-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coraggio F, Rotondano G, Marmo R, Balzanelli MG, Catalano A, Clemente F, et al. Somatostatin in the prevention of recurrent bleeding after endoscopic haemostasis of peptic ulcer haemorrhage: a preliminary report. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1998;10: 673-6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin HJ, Lo WC, Lee FY, Perng CL, Tseng GY. A prospective randomized comparative trial showing that omeprazole prevents rebleeding in patients with bleeding peptic ulcer after successful endoscopic therapy. Arch Intern Med 1998;158: 54-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lau JY, Sung JJ, Lee KK, Yung MY, Wong SK, Wu JC, et al. Effect of intravenous omeprazole on recurrent bleeding after endoscopic treatment of bleeding peptic ulcers. N Engl J Med 2000;343: 310-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Javid G, Masoodi I, Zargar SA, Khan BA, Yatoo GN, Shah AH, et al. Omeprazole as adjuvant therapy to endoscopic combination injection sclerotherapy for treating bleeding peptic ulcer. Am J Med 2001;111: 280-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sheu BS, Chi CH, Huang CC, Kao AW, Wang YL, Yang HB. Impact of intravenous omeprazole on Helicobacter pylori eradication by triple therapy in patients with peptic ulcer bleeding. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2002;16: 137-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaviani MJ, Hashemi MR, Kazemifar AR, Roozitalab S, Mostaghni AA, Merat S, et al. Effect of oral omeprazole in reducing re-bleeding in bleeding peptic ulcers: a prospective, double-blind, randomized, clinical trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2003;17: 211-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Desprez D, Blank P, Bories JM, Pageaux P, David XR, Veyrac M, et al. Acute upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage: preliminary report of a randomized controlled trial comparing intravenous administration of ranitidine and omeprazole. Gastroenterology 1995;108: A82. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fried R, Beglinger C, Meier R, Stumpf J, Alder G, Schepp W, et al. Comparison of intravenous pantoprazole with intravenous ranitidine in peptic ulcer bleeding. Gut 1999;45(suppl V): A100. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Duvnjak M, Supanc V, Troskot B, Kovacevic I, Antic Z, Hrabar D, et al. Comparison of intravenous pantoprazole with intravenous ranitidine in prevention of re-bleeding from gastroduodenal ulcers. Gut 2001;49(suppl III): 2379. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ebrahim S. Numbers needed to treat derived from meta-analyses: pitfalls and cautions. In: Egger M, Davey Smith G, Altman DG, eds. Systematic reviews in health care. Meta-analysis in context. London: BMJ Publishing, 2001: 386-99.

- 35.Rockall TA, Logan RF, Devlin HB, Northfield TC. Risk assessment after acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Gut 1996;38: 316-321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Collins R, Langman M. Treatment with histamine H2 antagonists in acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage: implications of randomised trials. N Engl J Med 1985;313: 660-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Levine JE, Leontiadis GI, Sharma VK, Howden CW. Meta-analysis: the efficacy of intravenous H2-receptor antagonists in bleeding peptic ulcer. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2002;16: 1137-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Merki HS, Wilder-Smith CH. Do continuous infusions of omeprazole and ranitidine retain their effect with prolonged dosing? Gastroenterology 1994;106: 60-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sung JJY, Chan FKL, Lau JYW, Yung MY, Leung WK, Wu JCY, et al. The effect of endoscopic therapy in patients receiving omeprazole for bleeding ulcers with nonbleeding visible vessels or adherent clots: a randomized comparison. Ann Intern Med 2003;139: 237-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.