Abstract

Purpose

Molecular-based cancer tests have been developed to augment the standard clinical and pathologic features used to tailor treatments to individual breast cancer patients. Homologous recombination (HR) repairs double-stranded DNA breaks and promotes tolerance to lesions that disrupt DNA replication. Recombination Proficiency Score (RPS) quantifies HR efficiency based on the expression of four genes involved in DNA damage repair. We hypothesized low RPS values can identify HR-deficient breast cancers most sensitive to DNA-damaging chemotherapy.

Experimental Design

We collected pathologic tumor responses and tumor gene expression values for breast cancer patients that were prospectively enrolled on clinical trials involving pre-operative chemotherapy followed by surgery (N=513). We developed an algorithm to calculate breast cancer-specific RPS (RPSb) values on an individual sample basis.

Results

Low RPSb tumors are approximately twice as likely to exhibit a complete pathologic response or minimal residual disease to pre-operative anthracycline-based chemotherapy as compared to high RPSb tumors. Basal, HER2-enriched and luminal B breast cancer subtypes exhibit low RPSb values. In addition, RPSb predicts treatment responsiveness after controlling for clinical and pathologic features, as well as intrinsic breast subtype.

Conclusion

Overall, our findings indicate that low RPS breast cancers exhibit aggressive features at baseline, but they have heightened sensitivity to DNA-damaging chemotherapy. Low RPSb values in basal, HER2-enriched and luminal B subtypes provide a mechanistic explanation for their clinical behaviors and genomic instability. RPSb augments standard clinical and pathologic features used to tailor treatments, thereby enabling more personalized treatment strategies for individual breast cancer patients.

Keywords: DNA damage, DNA repair, homologous recombination, genomic instability, breast cancer, chemotherapy, personalized medicine

Introduction

Breast cancer remains a leading cause of cancer death for women worldwide(1). Molecular-based cancer tests have been developed to augment the standard clinical and pathologic features used to tailor treatments to individual breast cancer patients(2). While some of these tests provide prognostic information(3–5) and/or predict responsiveness to therapies in general(5–7), relatively few are effective in predicting tumor sensitivity to individual types of treatment. Notable exceptions include the detection of estrogen receptor (ER) expression, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) gene amplification, and BRCA1/2 mutations, which predict sensitivity to endocrine therapy, trastuzumab, and inhibitors of poly (adenosine diphosphate-ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP1), respectively(8–11).

Human tumors exhibit a wide range of responsiveness to DNA-damaging treatments. This variation is hypothesized to result, at least in part, from differential efficiencies in DNA repair pathways. Homologous recombination (HR) mediates resistance to several classes of DNA-damaging therapies by catalyzing the repair of double-stranded breaks and by promoting tolerance to lesions that disrupt replication forks(12). HR also serves a genome-stabilizing role by ameliorating endogenous DNA lesions(12). In the context of patient care, HR deficiency in tumors can induce opposing net outcomes in terms of patient outcome. The underlying genomic instability associated with HR deficiency can fuel malignant progression and generate more aggressive tumor characteristics; however, HR deficiency can simultaneously induce sensitivity to DNA damaging treatments, which creates a therapeutic opportunity(13).

We hypothesized that measuring HR proficiency in individual tumors can be used to guide clinical cancer care. We previously described the Recombination Proficiency Score (RPS), which provides prognostic and predictive data on individual cancers by indirectly quantifying their HR repair proficiency(13). RPS is calculated based on the expression levels for four genes involved in DNA repair pathway preference (RIF1, PARI [PARPBP], RAD51, and Ku80 [XRCC5]); high expression of these genes yields a low RPS value. We found that these four RPS-defining genes provided a superior prediction of HR activity when compared to algorithms that utilize smaller or larger combinations of genes. Cells with a low RPS exhibit HR suppression and frequent DNA copy number alterations, which are characteristic of error-prone repair processes that arise in HR-deficient backgrounds. Consistent with this observed genomic instability, tumors with low RPS exhibit more malignant clinical and pathologic features. The RPS system was initially studied in patients with non-small cell lung carcinomas (NSCLC), which revealed that HR suppression plays a central role in promoting malignant progression. The adverse prognosis associated with a low RPS was diminished in NSCLC patients that received adjuvant platinum-based chemotherapy, suggesting that HR suppression and associated sensitivity to DNA crosslinking drugs counteracts the adverse baseline prognosis associated with a low RPS.

Our preliminary work also suggested that low RPS breast cancers similarly present with abundant malignant features, including ER loss, large-segment genomic deletions/ amplifications, HER2 gene amplification, and TP53 gene mutations(13). Here we test the hypothesis that RPS has utility in predicting responsiveness of breast cancers to therapy, by demonstrating that low RPS tumors are especially vulnerable to DNA-damaging chemotherapy. Importantly, we find that basal, HER2-enriched, and luminal B breast cancer subtypes(14) exhibit relatively low RPS values, which may help explain the aggressive clinical behaviors of these subtypes(5). Although RPS values associate with these molecularly defined ‘intrinsic subtypes’ of invasive breast cancer, RPS independently predicts sensitivity to anthracycline-based chemotherapy when controlled for subtype.

Materials and Methods

Identification of neoadjuvant breast cancer datasets

All datasets were identified (as of August 19, 2016) and downloaded from publicly available electronic databases (PubMed, GEO, ArrayExpress) using the following keywords: breast cancer, preoperative chemotherapy and neoadjuvant chemotherapy. After reviewing all retrieved studies, we identified 28 relevant datasets. Five neoadjuvant chemotherapy breast cancer datasets (Table 1 and Table S1) were selected for subsequent analysis after elimination of ineligible studies or patients based on criteria outlined in Figure S1. Briefly, patients were excluded from analysis if they received trastuzumab or if their chemotherapy regimen did not include all three of the following: an anthracycline, cyclophosphamide, and a taxane. Available data regarding pathologic complete response (pCR) incidence, age, tumor grade, estrogen receptor (ER) and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) statuses, tumor size, and nodal status was required for inclusion. Incidence of pCR following chemotherapy was defined as no residual invasive cancer in the breast and axillary lymph nodes. Post-chemotherapy residual cancer burden (RCB) information was available for 358 patients. RCB values indicate the extent of residual disease as follows: 0=none, I=minimal, II=moderate and III=extensive(15).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics in neoadjuvant chemotherapy studies

| Dataset | Percentage with the following features | Chemo drugs* | Citation# | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Age≤50 | T3/4 | Node+ | ER− | HER2+ | Grade3 | |||

| GSE25055 | 87 | 59 | 53 | 74 | 57 | 3 | 61 | A, T, C, +/− F | (18) |

| GSE25065 | 140 | 52 | 49 | 63 | 34 | 1 | 64 | A, T, C, F | (18) |

| GSE20194 | 230 | 39 | 34 | 68 | 37 | 17 | 54 | A, T, C, F | (20) |

| GSE20271 | 45 | 58 | 42 | 60 | 44 | 27 | 56 | A, T, C, F | (19) |

| GSE42822 | 11 | 45 | 82 | 73 | 73 | 55 | 73 | A, T, C, F | (22) |

| Combined | 513 | 48 | 43 | 67 | 41 | 12 | 59 | ||

A=doxorubicin or epirubicin; T=paclitaxel or docetaxel; C=cyclophosphamide; F=5-fluorouracil or capecitabine; ER=estrogen receptor; HER2=human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; T=tumor stage; ER and HER2 denote status determined by immunohistochemistry.

The gene expression data for these five publicly available datasets were previously generated on a uniform microarray platform (Affymetrix HG-U133A). Three additional independent breast cancer datasets (Table S2), also generated on the Affymetrix HG-U133A microarray platform, were selected and combined to serve as an independent frozen reference cohort, which enabled a per-subject calculation of gene expression z-scores in the five study datasets. We performed background correction, quantile normalization, robust-weighted-average summarization and log2-tranformation on each raw CEL file using the Single-Channel Array Normalization (SCAN) algorithm(16). SCAN is a microarray normalization algorithm that only uses data from within each array to estimate and remove probe-specific bias and background noise, hence every sample can be processed without dependence on other samples or requirement of external reference sets. Samples with identical raw signals across all probesets and identical array scan dates were identified and removed, since these likely represented redundant subjects shared by different studies (Table S3). Of these potentially redundant samples, 90% exhibited identical clinical information and 10% showed inconsistencies in clinical information between studies.

Derivation of breast cancer-specific RPS values

Our previous studies defined RPS as a linear combination of four signature genes (13): RPS = −1 * (RIF1 + PARPBP + RAD51 + XRCC5), where values denote median-normalized and log2-transformed gene expression measurements for an individual sample. This formula was used to determine RPS values for BRCA-mutant and sporadic clinical breast cancers (GSE40115 dataset). Basal and luminal B intrinsic breast subtypes were selected for this analysis to minimize the impact of breast subtype on differences in RPS values between BRCA mutants and sporadic tumors.

As a modification to the previously described method for calculating RPS, the mean (μ) and standard deviation (σ) of the independent frozen reference cohort was used to transform SCAN-normalized gene expression signals (x) to z-scores using the following formula: (Figure S2). Non-uniform weighting of each gene was used to develop a logistic model predicting probability of pCR after neoadjuvant chemotherapy (Figure S3). To determine the weight of each gene, we built a random forest (RF) model to estimate the variable importance of each gene. The five neoadjuvant chemotherapy datasets were combined into a single cohort after SCAN normalization and z-transformation, and samples were randomly split into training and independent test sets. The training set was used to tune the parameters and select the best model using 10-fold cross validation with custom evaluation metrics to handle imbalanced classes (17). After training, the test set was used to independently assess the performance of the final model. In each case we used various splitting percentages from 50%–50% to 90%–10% for training and test sets. We started with a full model with ten predictors, including the four gene expression values, as well as clinical and pathologic factors: pCR ~ RIF1 + PARPBP + RAD51 + XRCC5 +Age < 50 + ERplus + HER2plus + T3or4 + LNplus + Grade3. Variables with importance scores <20 (scaled to have a range of 0 to 100) were eliminated, leaving only the four RPS genes and ER status as predictors (Figure S4): pCR ~ RIF1 + PARPBP + RAD51 + XRCC5 + ERplus. The performance of this reduced model was evaluated in the test set with 81% sensitivity and 67% specificity, respectively (Table S4).

To further reduce the complexity of the predictor, samples were stratified into ER-positive (n=301) and ER-negative (n=212) subsets to eliminate the effect of ER status in the model. Using the expression levels for the four genes as predictors, we built two separate models in ER-positive and ER-negative subsets of samples (50%–50% for training and test sets): pCR ~ RIF1 + PARPBP + RAD51 + XRCC5 (Figure S3). The performance of the ER-negative model was superior in predicting pCR as compared to the ER-positive model. Therefore, we used the variable importance estimates in the ER-negative model to calculate the weight of each gene in contribution to RPSb. This generated the final breast cancer-specific RPS model: RPSb = −1 * (0.2171423 * RIF1 + 0.1946173 * PARPBP + 0.2783017 * RAD51 + 0.3099387 * XRCC5), with the sum of gene weight coefficients equal to 1.

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy dataset analysis

Continuous RPSb values were compared to expected probability of pCR using logistic regression models (Figure 1 and Table S5). We built logistic regression models to fit the relationship between probability of pCR (y variable, binary) and RPSb value (x variable, continuous) using the Generalized Linear Models method (R function glm, link function logit). We fitted a logistic regression model (R function glm) on each of the ER-positive and ER-negative subsets. Hosmer-Lemeshow tests (R function hoslem.test) were used to assess whether the models fit the respective data. Chi-squared tests were used to assess for differences between RCB class frequencies as a function of RPSb value. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to assess for interaction between RPSb and class of neoadjuvant chemotherapy (anthracycline- vs. non-anthracycline-based) in the GSE21997 dataset. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to determine the odds ratio of achieving a pCR as a function of RPSb, after controlling for standard clinical and pathologic factors or intrinsic breast subtype. Annotations of intrinsic breast subtypes (as defined by the PAM50 algorithm(5)) were available for 457 patients (Table S5). In these analyses we omitted patients with so called ‘normal breast-like’ intrinsic subtypes breast cancer, since controversy exists as to whether this pattern of gene expression is simply an artifact due to normal tissue contamination of tumor specimens(18).

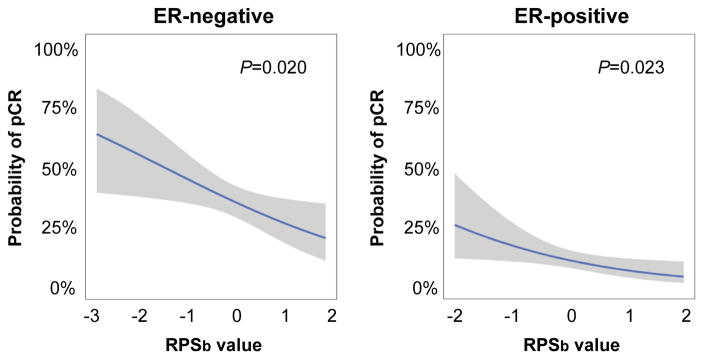

Figure 1. RPS predicts likelihood of achieving a pathologic complete response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer.

Depicted are logistic regression models relating RPSb values to predicted probability of pathologic complete response (pCR) following neoadjuvant anthracycline-based chemotherapy for ER-negative (left) and ER-positive (right) tumors. Solid line=fitted model; shaded region=95% confidence interval. P-values indicate significance of RPSb parameter estimate based on Chi-square test. Both training and testing sets were combined for ER-negative patients.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed using JMP 9.0 (SAS Institute Inc.; Cary, NC) and R software. The predictive model training and testing was performed using R package caret, Classification and Regression Training, R package, version 6.0–52 (17).

Results

We examined whether HR suppression in low RPS breast cancers predicts sensitivity to DNA-damaging chemotherapies. This hypothesis is supported by the low RPS values that exist in the setting of BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations, relative to sporadic breast tumors with wild-type BRCA1 and BRCA2 (Figure S5). However, breast cancers can also exhibit HR suppression and sensitivity to DNA-damaging chemotherapies, or so-called BRCAness, even in the absence of a BRCA gene mutation. Therefore, we examined several prospectively collected publicly available clinical breast cancer datasets, which were identified based on specific criteria highlighted in Figure S1. We specifically focused on patients whose treatment consisted of pre-operative chemotherapy followed by tumor resection. This is a particularly powerful clinical setting for evaluating chemo-sensitivity of tumors, since rates of tumor responsiveness are quantified histologically using standardized methods. These criteria yielded 513 total patients (5 studies summarized in Table 1 and Table S1), all of whom received relatively uniform chemotherapy regimens that included an anthracycline, a taxane, and cyclophosphamide(18–22). Anthracycline-based regimens were deemed appropriate for this analysis given that anthracyclines intercalate between stacked DNA base pairs, resulting in double-stranded DNA breaks that involve HR for their repair(23). Importantly, data on these 513 patients were collected in accordance with prospective trials, suggesting a minimal degree of selection bias and a favorable degree of patient uniformity with respect to tumor and treatment characteristics.

We developed a method to measure RPS from tumors on a per-sample basis. This important detail enables the calculation of ‘stand-alone’ scores for any given patient, rather than relying on percentiles within larger study cohorts. This method also ensures reproducibility of normalized expression signals, eliminating test set bias introduced during data preprocessing(24). This was accomplished by first constructing a frozen reference cohort, consisting of three independent clinical breast cancer datasets comprising 756 total patients (Table S2). The expression of each RPS-defining gene was then determined for 513 study subjects, using the mean (μ) and standard deviation (σ ) precomputed from the frozen reference cohort to transform the gene expression signals to a z-score value. Variable importance measures were computed from optimized and validated RFs models for each RPS-defining gene (RIF1, XRCC5, RAD51 and PARPBP), together with other clinical-pathologic variables (age, T stage, N stage, grade, ER status and HER2 status) that are commonly used to evaluate breast cancers (Figure S4). Notably, each of the four RPS genes and ER status ranked among the most important factors in terms of predicting pCR following chemotherapy. Among the four RPS-defining gene expression levels themselves, there were slight differences in their individual importance scores. For this reason, the definition of RPS was modified to account for the relative contribution of each gene in breast cancer (hereafter termed RPSb to denote breast cancer-specific score): RPSb = −1 * (0.2171423 * RIF1 + 0.1946173 * PARPBP + 0.2783017 * RAD51 + 0.3099387 * XRCC5). This makes use of SCAN-normalized, z-transformed gene expression values as described in the Methods.

We evaluated the probability of achieving a pathologic complete response (pCR) to pre-operative anthracycline-based chemotherapy as a function of tumor RPSb (Figure 1). Logistic regression analysis demonstrated an inverse relationship between RPSb and probability of pCR (P=0.020) in ER-negative tumors. In ER-negative tumors with RPSb values ≤ -1.4, the probability of pCR exceeded 50%. In contrast, less than 25% of ER-negative tumors with RPSb values ≥ 1.2 exhibited a pCR. As expected, pCR rates were considerably lower in ER-positive tumors than ER-negative tumors (10.6 vs. 35.9%, P <0.0001). Among these ER-positive tumors, logistic regression analysis also confirmed an inverse relationship between RPSb and probability of pCR (P=0.023). In addition, in ER-positive tumors with RPSb values ≤ −1.2, the probability of pCR exceeded 20%.

RPSb was directly compared to clinical and pathologic factors that can influence response to chemotherapy, using univariate (Figure S6) and multivariate logistic regression analyses (Table 2). The multivariate analysis demonstrated that RPSb (considered as a continuous variable) is an independently predictive factor for pCR rates after anthracycline-based chemotherapy (P=0.0091). Over the range of RPSb values (−2.7 to 1.9), there was a 1.5-fold increased multivariate odds ratio of achieving a pCR for each unit decrease in RPSb. Therefore, RPS provides additional predictive information on tumor sensitivity which exceeds that provided by standard clinical-pathologic factors.

Table 2.

Multivariate analysis testing the probability of pCR as a function of clinical-pathologic features and RPS

| Variable | Odds Ratio (95%CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical-pathologic factors | ||

| Age <50 years | 1.37 (0.86–2.19) | 0.18 |

| Tumor stage 3, 4 | 0.63 (0.39–1.02) | 0.058 |

| Node positive | 0.96 (0.58–1.60) | 0.87 |

| Grade 3 | 1.87 (1.04–3.43) | 0.037 |

| ER negative | 3.49 (2.11–5.90) | <0.0001 |

| HER2 positive | 2.16 (1.16–3.97) | 0.016 |

| RPS value (per one unit decrease) | 1.49 (1.10–2.02) | 0.0091 |

Odds ratio of pCR determined using multivariate logistic regression analysis of the indicated covariates. Chi-square P-value determined using likelihood ratio test. ER=estrogen receptor; HER2=human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; CI=confidence interval.

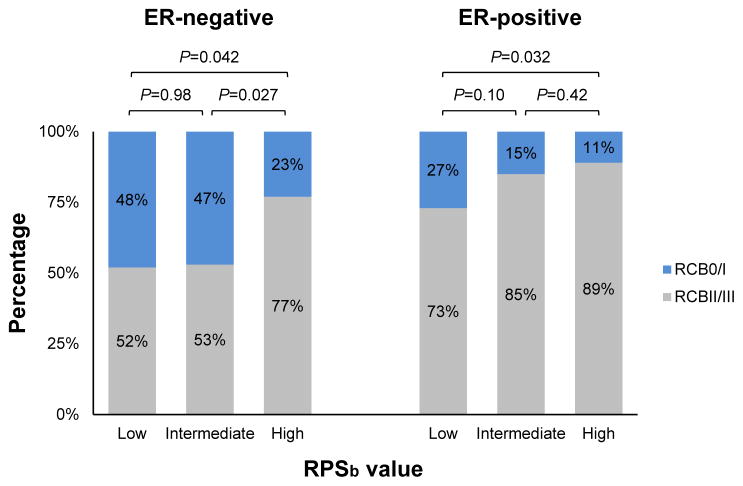

While pCR is a commonly utilized measure of chemo-sensitivity in breast cancer, the binary nature of this endpoint carries practical limitations. For this reason residual cancer burden (RCB) measurements have been developed to document graded levels of pathologic tumor response. This distinction is clinically relevant, since the degree of pathologic response can influence management decisions, like the choice between breast-conserving surgery vs. mastectomy. We evaluated RCB responses as a function of tumor RPSb. We found that low RPSb tumors are approximately twice as likely to achieve an RCB-0/I (pCR or minimal residual disease) as compared to high RPSb tumors (Figure 2). In ER-negative tumors, 48% of low RPSb tumors demonstrated an RCB-0/I response as compared to 23% of high RPSb tumors (P = 0.042). Similarly, in ER-positive tumors, 27% of low RPSb tumors achieved an RCB-0/I response as compared to 11% of high RPSb tumors (P = 0.032). This suggests that RPS testing may serve a useful role in both ER-negative and ER-positive tumors.

Figure 2. RPS predicts residual cancer burden following neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer.

RCB-0/I=pathologic complete response (pCR)/minimal residual disease; RCB-II/III=moderate/extensive residual disease. Low, intermediate and high RPS values denote the lowest 25th, middle 50th, and highest 25th RPS percentiles. P-values were determined using Chi-Square tests between groups.

We tested the hypothesis that the predictive utility of RPSb is specific to DNA-damaging chemotherapy by evaluating tumor response rates after neoadjuvant treatment with single-agent doxorubicin (a DNA-damaging anthracycline) vs. docetaxel (a non-DNA-damaging taxane). Multivariate logistic regression analysis confirmed a significant interaction between low RPSb value and chemotherapy type (favoring doxorubicin over docetaxel) in the prediction of RCB response (likelihood ratio Chi-square test, P=0.0044). As expected, neoadjuvant doxorubicin generated RCB-0 response rates in 25% of low RPSb tumors vs. 0% of high RPSb tumors (Figure S7). By contrast, the lower RPSb tumors did not respond better to neoadjuvant docetaxel, relative to higher RPSb tumors. In fact, lower RPSb tumors instead exhibited a greater resistance to docetaxel, which is consistent with published observations suggesting taxane resistance in BRCA mutant tumors(25). These findings support the conclusion that the predictive power of RPSb is specific to DNA-damaging therapies.

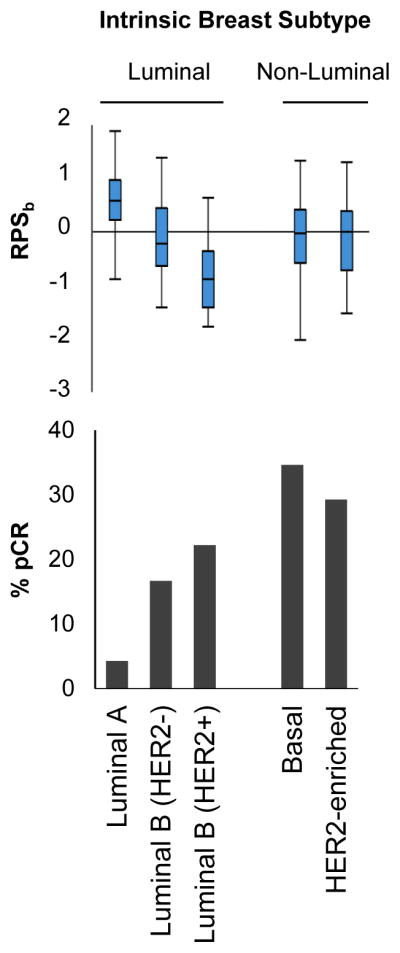

In clinical practice, breast cancers are commonly categorized based on ER status and HER2/neu gene amplification, and the resulting sub-categories associate with varying levels of treatment sensitivity. We observed that HER2+ and triple-negative tumors exhibit lower RPSb values as compared to hormone receptor-positive tumors (Figure S8). More recently, breast cancers have been further categorized into molecularly defined subtypes based on gene expression patterns(14). Consistent with previous reports(5), we observed variable degrees of chemo-sensitivity associated with these distinct subtypes (Figure 3). Therefore, we investigated for a potential relationship between RPSb and intrinsic subtypes. Among luminal subtypes we observed significantly higher RPSb values in luminal A tumors (mean ± standard error of mean: 0.56 ± 0.062), relative to luminal B tumors (luminal B/HER2−: −0.16 ± 0.087; luminal B/HER2+: −0.80 ± 0.25; both 2-tailed Student’s t-test P<0.0001). Both of the non-luminal subtypes also exhibited relatively low RPSb values (basal: −0.10 ± 0.059; HER2-enriched: −0.12 ± 0.12) relative to luminal A tumors (both 2-tailed Student’s t-test P<0.0001).

Figure 3. RPS associates with intrinsic breast cancer subtypes.

Box-whisker plots of RPSb values (top) and pCR rates (bottom) by intrinsic breast subtypes.

Tumor subtypes with highest pCR rates (basal, HER2-enriched, and luminal B/HER2+) exhibit relatively low RPS values (Figure 3). Given this apparent relationship between these two factors in breast cancer, we investigated whether the treatment-predictive power of RPSb is independent of subtype. RPSb was analyzed together with intrinsic breast subtype using multivariate logistic regression analyses (Table 3). This demonstrated that RPS (considered as a continuous variable) is independently predictive of pCR (considered as a binary variable) following treatment with anthracycline-based chemotherapy. Over the range of RPSb values (−2.7 to 1.9), there was a 1.7-fold increased multivariate odds ratio of achieving a pCR for each unit decrease in RPSb. Therefore, RPSb provides predictive information on tumor sensitivity that exceeds existing clinical-pathologic factors or intrinsic subtyping alone.

Table 3.

Multivariate analysis testing the probability of pCR as a function of intrinsic breast subtype and RPS

| Variable | Odds Ratio (95%CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Array-based subtypes | ||

| Luminal A | 1 (reference) | |

| Basal | 9.30 (4.02–25.5) | <0.0001 |

| HER2-enriched | 7.20 (2.50–22.7) | 0.0002 |

| Luminal B (HER2 negative) | 3.40 (1.21–10.4) | 0.020 |

| Luminal B (HER2 positive) | 3.79 (0.47–21.9) | 0.19 |

| RPS value (per one unit decrease) | 1.48 (1.04–2.10) | 0.027 |

Odds ratio of pCR determined using multivariate logistic regression analysis of the indicated covariates. Odds ratios for intrinsic subtypes were calculated relative to Luminal A tumors. Chi-square P-value determined using likelihood ratio test. CI=confidence interval.

Discussion

RPS provides an estimate of DNA repair efficiency in human malignancies, wherein low RPS tumors harbor HR suppression. We previously demonstrated that low RPS breast cancers exhibit genomic instability and adverse clinical features, suggesting that HR suppression in these tumors promotes malignant progression and the emergence of aggressive phenotypes(13). We now show that low RPSb breast tumors simultaneously exhibit a heightened sensitivity to DNA-damaging therapy, which creates a novel therapeutic opportunity. Therefore, RPSb provides both prognostic and predictive characterization of individual breast cancers: it identifies the tumors likely to behave most aggressively, while simultaneously identifying the tumors most likely to benefit from DNA-damaging therapies.

Numerous gene expression classifier systems have been proposed to the predict sensitivity of breast cancers to anthracycline-based chemotherapy, however relatively few have undergone extensive clinical validation(26). The OncotypeDx 21-gene recurrence score (RS), which remains the most extensively validated test of its class, is indicated primarily for ER-positive cases(3, 6, 7). By comparison, RPSb appears to be effective in both ER-positive and ER-negative cases. Additionally, our results demonstrate that RPSb and intrinsic subtyping are independently predictive of sensitivity to anthracycline-based chemotherapy on multivariate analysis. This suggests that RPSb testing and intrinsic subtyping may be superior to either test alone.

The low RPSb values we observed in basal, HER2-enriched and luminal B subtypes may provide mechanistic explanations for their clinical behaviors(5) and their propensity for genomic instability(27, 28). These subtypes are known to exhibit a relatively high risk for recurrence in patients that receive no systemic therapy, suggesting that they harbor more malignant baseline characteristics(5). However, these subtypes are more likely to respond to pre-operative chemotherapy(5). Our results suggest that both of these clinical behaviors may be explained by HR suppression, and that this can be readily quantified by RPSb testing.

Some sporadic breast cancers exhibit behaviors that are reminiscent of tumors occurring in BRCA germline mutations carriers, and this feature has been termed BRCAness(29). While BRCAness can result from somatic mutations in HR-promoting genes(30), it is more commonly identified based on characteristic patterns of resulting genomic instability. Various detection methods have been proposed, including the identification of large-segment DNA copy number alterations(31–35) or smaller DNA sequence signatures(36) that associate with HR loss. Low RPSb measurements may share some commonality with these competing tests of BRCAness. It is worth considering, however, that these DNA-based detection methods recognize the consequences of HR deficiency; therefore, test results are not expected to recognize the eventual development of treatment resistance. Further work is ongoing to test whether RPSb (which instead depends on gene expression levels) may provide a more dynamic real-time approximation of HR activity over the course of treatment.

We chose to study RPSb in the context of commonly used anthracycline-based chemotherapy regimens because numerous large clinical datasets were available for such analyses. However, HR deficiency is more commonly associated with tumor sensitivity to other drug classes, including PARP1 inhibitors and DNA cross-linkers(10–12). Several recent studies using platinum-based chemotherapy and PARP1 inhibitors have observed correlations between measured BRCAness and tumor sensitivity(37–40). For example, the I-SPY-2 investigators recently demonstrated impressive sensitivity of triple-negative breast cancers to pre-operative therapy with veliparib plus carboplatin(40). Similarly, Telli and colleagues observed relatively high response rates to platinum-based chemotherapy in breast tumors that harbor low homologous recombination deficiency (HRD) scores(37). Further work is needed to test whether RPSb can similarly predict efficacy for these drug classes, thereby enabling ideal selection of therapies to individual patients.

Supplementary Material

Translational Relevance.

Breast cancer remains a leading cause of cancer death. Molecular-based cancer tests have been developed to augment the tumor features used to tailor treatments to individual breast cancer patients; however, relatively few are effective in predicting tumor sensitivity to individual types of treatment. We previously developed the Recombination Proficiency Score (RPS), which quantifies DNA repair efficiency based on the expression of genes that mediate DNA repair. Herein, we trained and validated a breast cancer-specific RPS test (RPSb) that calculates individual per-patient scores. Low RPSb tumors exhibit relatively aggressive features at baseline but are approximately twice as likely to respond to pre-operative anthracycline-based chemotherapy, as compared to higher RPSb tumors. Therefore, RPSb augments standard clinical and pathologic features used to tailor treatments, thereby enabling more personalized treatment strategies for individual breast cancer patients.

Acknowledgments

Funding Support: This work was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health [NIH grant 2R01CA142642, P.P. Connell], the Ludwig Foundation for Cancer Research [R.R. Weichselbaum], the Chicago Tumor Institute [R.R. Weichselbaum], a gift from the Foglia Foundation [R.R. Weichselbaum], and Stand Up To Cancer – Ovarian Cancer Research Fund, the Ovarian Cancer National Alliance, and the National Ovarian Cancer Coalition Ovarian Cancer Dream Team Translational Research Grant (Grant Number: SU2C-AACR-DT16-15). Stand Up To Cancer is a program of the Entertainment Industry Foundation administered by the American Association for Cancer Research, the scientific partner of SU2C.

We are indebted to the curators of publicly available datasets.

Footnotes

AUTHORS’ DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST:

The University of Chicago has filed the patent application “Methods and Compositions Relating to Cancer Therapy with DNA Damaging Agents,” which is currently pending. PPC, SPP, and RRW are all named as inventors on this application. PPC is a paid advisor of Shuwen Biotech, which licensed this intellectual property.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS:

All of the analyses were designed by SPP and PPC and performed by SPP, RB, JA and PPC. The manuscript was drafted by PPC and SPP and revised by RRW and RB.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wirapati P, Sotiriou C, Kunkel S, et al. Meta-analysis of gene expression profiles in breast cancer: toward a unified understanding of breast cancer subtyping and prognosis signatures. Breast Cancer Res. 2008;10:R65. doi: 10.1186/bcr2124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paik S, Shak S, Tang G, et al. A multigene assay to predict recurrence of tamoxifen-treated, node-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2817–26. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van ‘t Veer LJ, Dai H, van de Vijver MJ, et al. Gene expression profiling predicts clinical outcome of breast cancer. Nature. 2002;415:530–6. doi: 10.1038/415530a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parker JS, Mullins M, Cheang MC, et al. Supervised risk predictor of breast cancer based on intrinsic subtypes. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1160–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.1370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paik S, Tang G, Shak S, et al. Gene expression and benefit of chemotherapy in women with node-negative, estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3726–34. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.7985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Albain KS, Barlow WE, Shak S, et al. Prognostic and predictive value of the 21-gene recurrence score assay in postmenopausal women with node-positive, oestrogen-receptor-positive breast cancer on chemotherapy: a retrospective analysis of a randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:55–65. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70314-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davies C, Godwin J, Gray R, et al. Relevance of breast cancer hormone receptors and other factors to the efficacy of adjuvant tamoxifen: patient-level meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet. 2011;378:771–84. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60993-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Slamon DJ, Leyland-Jones B, Shak S, et al. Use of chemotherapy plus a monoclonal antibody against HER2 for metastatic breast cancer that overexpresses HER2. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:783–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200103153441101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farmer H, McCabe N, Lord CJ, et al. Targeting the DNA repair defect in BRCA mutant cells as a therapeutic strategy. Nature. 2005;434:917–21. doi: 10.1038/nature03445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bryant HE, Schultz N, Thomas HD, et al. Specific killing of BRCA2-deficient tumours with inhibitors of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase. Nature. 2005;434:913–7. doi: 10.1038/nature03443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thompson LH, Schild D. Homologous recombinational repair of DNA ensures mammalian chromosome stability. Mutat Res. 2001;477:131–53. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(01)00115-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pitroda SP, Pashtan IM, Logan HL, et al. DNA repair pathway gene expression score correlates with repair proficiency and tumor sensitivity to chemotherapy. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:229ra42. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3008291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fan C, Oh DS, Wessels L, et al. Concordance among gene-expression-based predictors for breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:560–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Symmans WF, Peintinger F, Hatzis C, et al. Measurement of residual breast cancer burden to predict survival after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4414–22. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.10.6823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Piccolo SR, Sun Y, Campbell JD, Lenburg ME, Bild AH, Johnson WE. A single-sample microarray normalization method to facilitate personalized-medicine workflows. Genomics. 2012;100:337–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2012.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuhn M. Building Predictive Models in R Using the caret Package. Journal of Statistical Software. 2008:28. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hatzis C, Pusztai L, Valero V, et al. A genomic predictor of response and survival following taxane-anthracycline chemotherapy for invasive breast cancer. Jama. 2011;305:1873–81. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tabchy A, Valero V, Vidaurre T, et al. Evaluation of a 30-gene paclitaxel, fluorouracil, doxorubicin, and cyclophosphamide chemotherapy response predictor in a multicenter randomized trial in breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:5351–61. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Popovici V, Chen W, Gallas BG, et al. Effect of training-sample size and classification difficulty on the accuracy of genomic predictors. Breast Cancer Res. 2010;12:R5. doi: 10.1186/bcr2468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miyake T, Nakayama T, Naoi Y, et al. GSTP1 expression predicts poor pathological complete response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in ER-negative breast cancer. Cancer Sci. 2012;103:913–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2012.02231.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shen K, Qi Y, Song N, et al. Cell line derived multi-gene predictor of pathologic response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer: a validation study on US Oncology 02-103 clinical trial. BMC Med Genomics. 2012;5:51. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-5-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spencer DM, Bilardi RA, Koch TH, et al. DNA repair in response to anthracycline-DNA adducts: a role for both homologous recombination and nucleotide excision repair. Mutat Res. 2008;638:110–21. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patil P, Bachant-Winner PO, Haibe-Kains B, Leek JT. Test set bias affects reproducibility of gene signatures. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:2318–23. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kriege M, Jager A, Hooning MJ, et al. The efficacy of taxane chemotherapy for metastatic breast cancer in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. Cancer. 2012;118:899–907. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ignatiadis M, Singhal SK, Desmedt C, et al. Gene modules and response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer subtypes: a pooled analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1996–2004. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.5624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Comprehensive molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2012;490:61–70. doi: 10.1038/nature11412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bergamaschi A, Kim YH, Wang P, et al. Distinct patterns of DNA copy number alteration are associated with different clinicopathological features and gene-expression subtypes of breast cancer. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2006;45:1033–40. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Turner N, Tutt A, Ashworth A. Hallmarks of ‘BRCAness’ in sporadic cancers. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:814–9. doi: 10.1038/nrc1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pennington KP, Walsh T, Harrell MI, et al. Germline and somatic mutations in homologous recombination genes predict platinum response and survival in ovarian, fallopian tube, and peritoneal carcinomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:764–75. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-2287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Joosse SA, Brandwijk KIM, Devilee P, et al. Prediction of BRCA2-association in hereditary breast carcinomas using array-CGH. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2012;132:379–89. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-1016-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Joosse SA, van Beers EH, Tielen IHG, et al. Prediction of BRCA1-association in hereditary non-BRCA1/2 breast carcinomas with array-CGH. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2009;116:479–89. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-0117-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schouten PC, Marme F, Aulmann S, et al. Breast cancers with a BRCA1-like DNA copy number profile recur less often than expected after high-dose alkylating chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2014 doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-1894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tirkkonen M, Johannsson O, Agnarsson BA, et al. Distinct somatic genetic changes associated with tumor progression in carriers of BRCA1 and BRCA2 germ-line mutations. Cancer Res. 1997;57:1222–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wessels LF, van Welsem T, Hart AA, van’t Veer LJ, Reinders MJ, Nederlof PM. Molecular classification of breast carcinomas by comparative genomic hybridization: a specific somatic genetic profile for BRCA1 tumors. Cancer Res. 2002;62:7110–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alexandrov LB, Nik-Zainal S, Wedge DC, et al. Signatures of mutational processes in human cancer. Nature. 2013;500:415–21. doi: 10.1038/nature12477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Telli ML, Timms KM, Reid J, et al. Homologous Recombination Deficiency (HRD) Score Predicts Response to Platinum-Containing Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in Patients with Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22:3764–73. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-2477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vollebergh MA, Lips EH, Nederlof PM, et al. Genomic patterns resembling BRCA1- and BRCA2-mutated breast cancers predict benefit of intensified carboplatin-based chemotherapy. Breast Cancer Res. 2014;16:R47. doi: 10.1186/bcr3655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schouten PC, Marme F, Aulmann S, et al. Breast cancers with a BRCA1-like DNA copy number profile recur less often than expected after high-dose alkylating chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:763–70. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-1894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rugo HS, Olopade OI, DeMichele A, et al. Adaptive Randomization of Veliparib-Carboplatin Treatment in Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:23–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1513749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.