Abstract

Exposure of susceptible neuroblastoma N2a cells to mouse scrapie prions leads to infection, as evidenced by the continued presence of the scrapie form of the prion protein (PrPSc) and infectivity after 300 or more cell doublings. We find that exposure to phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C (PIPLC) or to the monoclonal anti-prion protein (PrP) antibody 6H4 not only prevents infection of susceptible N2a cells but also cures chronically scrapie-infected cultures, as judged by the long-term abrogation of PrPSc accumulation after cessation of treatment. A nonpassaged, stationary infected culture rapidly loses PrPSc when exposed to the antibody or PIPLC, indicating that the PrPSc level is determined by steady state equilibrium between formation and degradation, and that depletion of the cellular form of PrP can interrupt the propagation of PrPSc. These findings encourage the belief that passive immunization may provide a therapeutic approach to prion disease.

The “protein only” hypothesis proposes that the causative agent of transmissible spongiform encephalopathies, the prion, is identical with a conformational isoform of the cellular form of the prion protein (PrPC) (1). PrPC is a normal host protein (2–4) that occurs in most organs, but most abundantly in the brain. It carries up to two N-linked glycans, is anchored at the outer surface of the plasma membrane by a glycosylphosphatidylinositol tail, and is associated with caveolae, at least in cultured cells (5, 6). The abnormal conformer, when introduced into the organism, causes conversion of PrPC into a likeness of itself (1).

During the course of prion disease, a largely protease-resistant, aggregated form of PrP, designated PrPSc, accumulates mainly in brain, and may be the main or only constituent of the prion (2, 7). Because no differences in primary sequence were found between PrPC and PrPSc (8), the two species are believed to differ only in their conformation.

Only few cell lines, mostly derived from neural tissue, such as the N2a, GT1, and PC12 lines (9–12), but also an epithelial rabbit cell line (13), can be infected by scrapie agent, as evidenced by the presence of infectivity and/or PrPSc after multiple passages, sufficient to eliminate the original inoculum. Only a small fraction of a N2a or GT1 cell population is readily infected by the mouse-adapted Rocky Mountain Laboratory (RML) scrapie strain, but from such populations sublines can be established which are highly susceptible to infection (14, 15).

We have used the approach of Bosque and Prusiner (14) to isolate N2a sublines susceptible or resistant to RML scrapie prions. Scrapie infection of the susceptible subline N2a/Bos2 is prevented by the monoclonal anti-PrP antibody 6H4 (16) or by phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C (PIPLC), which cleaves PrPC off the cell surface. Exposure of infected cells to the antibody or to PIPLC causes rapid loss of PrPSc even without splitting of the cultures, showing that the level of PrPSc is determined by the rates of its formation from PrPC and its degradation. Finally, we show that transient treatment of infected cultures with antibody abrogates PrPSc formation for at least 6 weeks of further culturing in its absence, suggesting that the cells have been cured of prion infection.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture.

Mouse neuroblastoma N2a cells were cultured in OPTI-MEM supplemented with 10% FCS and penicillin G and streptomycin (complete medium) at 37°C in 5% CO2/95% air. Cells were routinely split 1:5 every 3–4 days and grown in 10-cm dishes (Corning Costar). PIPLC was from Sigma. Antibodies used were of the monoclonal IgG1 subtype: anti-PrP (6H4, Prionics, Zürich, Switzerland), anti-desmin (DE-U-ID, Sigma), and anti β-actin (AC-15, Sigma).

Prion Infection of N2a Cells.

Brains from scrapie-sick mice infected with RML mouse-adapted prions were homogenized by passing eight times each through 21- and 25-gauge needles and adjusted to 10% (wt/vol) with 1× Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline (GIBCO/BRL). After centrifuging for 5 min at 1,000 rpm (Eppendorf Centrifuge 5415c, Hamburg, Germany) and at room temperature, supernatants were recovered and stored at −80°C. Mouse PrPSc was partially purified as described (17). Cells (2–5 × 104 in 1 ml of medium) were seeded into 24-well plates (Corning Costar) and cultured for 1–2 days before exposure to either 20 ng/ml purified PrPSc (RML strain) or RML-infected mouse brain homogenate, diluted as indicated with complete medium. The inoculum was removed after 3 days and the cells were split 1:5 every 3–4 days. After 14 days the cells were assayed for PrPSc by the cell blot procedure (14).

Selection of Prion-Susceptible and Prion-Resistant N2a Sublines.

N2a cells were cotransfected with pSVneo (18), which confers neomycin resistance and a plasmid (pEF-Bos-EX; ref. 19) containing a “half-genomic” PrP transcription unit (20) with the ORF of wild-type PrP, MHM2 PrP (21, 22), or MH2M PrP (21, 22), under the control of the EF1α promoter. The intention was to generate N2a cell lines that overexpress mouse or hamster–mouse hybrid PrP molecules and thereby facilitate infection with mouse and/or hamster prions (22). As negative control, cotransformation was performed with pSVneo and pEF-BOS-EX devoid of an ORF. After selection in G418 at 0.7 mg/ml, clones of each group were tested for susceptibility to infection by RML scrapie prions, as described above. Clone N2a/Bos2 was selected as the most susceptible subline and aliquots thereof and of N2a/Bos2 cells chronically infected with RML prions were kept at −80°C.

Cell Blot Assay for PrPSc.

The assay was performed as described (14). In short, cells were transferred to a poly(vinylidene difluoride) membrane, treated with proteinase K, denatured, immunostained with antibody 6H4 (Prionics) followed by horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG1, and visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL kit; Pierce). After exposure, the membrane was stained for 15 min with 0.5 μg/ml ethidium bromide and photographed in UV light to document the transfer of the cell layer.

Western Blot Analysis.

Samples (15 μg total protein) were run through SDS/16% polyacrylamide gels (8 × 8 cm) and transferred to a poly(vinylidene difluoride) membrane by electroblotting at 35 V for 1 h. PrP was detected by incubation with 200 ng/ml monoclonal anti-PrP antibody 6H4 (16) followed by horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG1 (Zymed; 10,000-fold dilution in TBST [10 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween 20] containing 1% dry milk) at room temperature for 1 h. The immune complex was visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL kit, Pierce).

Results

Isolation of Cell Lines Susceptible and Resistant to RML Scrapie Prions.

N2a cells were transformed with PrP expression (or control) plasmids with the intent of raising their PrP level and thereby rendering them more susceptible to infection with prions from various sources. Transformed clones were assayed for their susceptibility to RML prion infection by an immunoblotting assay (14) (Fig. 1a). Unexpectedly, the most susceptible line, N2a/Bos2, was derived from cells that had been transformed with the control plasmid. To assess the proportion of cells susceptible to infection, N2a/Bos2 cells were subcloned and assayed by the blotting procedure; 49% of the cells were susceptible to infection (data not shown).

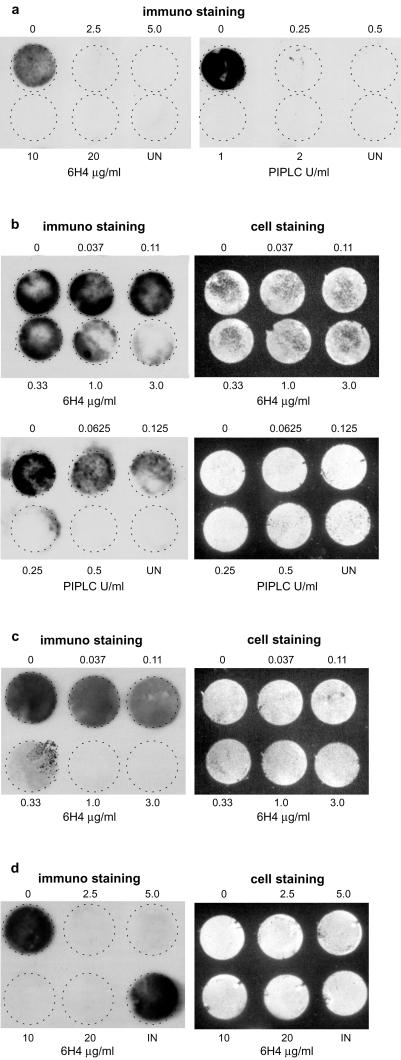

Figure 1.

Susceptibility to scrapie infection and PrP level of various sublines of N2a cells. N2a populations as propagated routinely in the lab and single clones transformed with a PrP expression or a control vector were seeded into 24-well plates (2 × 104 cells per well) and grown to confluence. (a) Cultures were exposed for 3 days to purified mouse PrPSc (RML strain, 20 ng/ml), cultured for 29 days (eight passages), and assayed for PrPSc formation by the cell blot assay (14). (b) Prion-susceptible N2a/Bos2 and resistant N2a/2M11 cells were exposed for 3 days to the dilutions indicated of infected 10% brain homogenate, cultured for 14 days (three passages), and assayed for PrPSc formation. Cells exposed to a 10−4 dilution are still slightly positive. (c) Western blot analysis of N2a sublines was performed with monoclonal anti-PrP antibody 6H4 as outlined in Materials and Methods. Cells transfected with the expression plasmid for mouse PrPc, MHM2 PrP (21) or MH2M PrP (21) are indicated by mo, M2, or 2M, respectively. BOS designates cells cotransfected with pSVneo and pEF-BOS-EX. N2a, the original uncloned cells, as well as the highly susceptible N2a/Bos2 cell line show similar low expression of PrPC as compared with the nonsusceptible mo5 or 2M11 lines.

N2a/Bos2 cells and a prion-resistant line, N2a/2M11 (transformed with a PrP expression plasmid), were challenged with mouse-scrapie-infected brain extract at various dilutions and passaged for 2 weeks. N2a/Bos2 cultures became PrPSc-positive after exposure to scrapie-infected 10% brain homogenate diluted up 10−4, whereas the resistant line remained negative at all dilutions tested (Fig. 1b).

Surprisingly, the susceptible line N2a/Bos2 expressed PrP at about the same low level as the original N2a cells, whereas the resistant line expressed PrP at a level 10 or more times higher, as shown by Western blot analysis (Fig. 1c). PrP is essential for prion propagation and scrapie pathogenesis (23, 24), and overexpression of PrP decreases incubation time in transgenic mice (20, 25). Nonetheless, overexpression does not increase levels of infectivity in brain (20), nor do tissues that do not normally produce prions become permissive by ectopic overexpression of PrP (26, 27). PrP was expressed at the cell surface of all lines, as evidenced by biotinylating intact cells, immunoprecipitating the extracted proteins with anti-PrP antibody, and subjecting them to Western blot assay with horseradish peroxidase-labeled streptavidin (data not shown). Our findings reinforce the conclusion that factors other than PrP are essential for susceptibility to infection by prions (26, 27).

PIPLC and Anti-PrP Monoclonal Antibody 6H4 Prevent Infection of the Susceptible N2a Cell Line by Scrapie Prions.

Monoclonal anti-PrP antibody 6H4 recognizes residues 144–152 of murine PrP and thus binds to its helix 1 (16). PIPLC cleaves the glycosylphosphatidylinositol moiety linking PrP to the outer surface of the plasma membrane, thereby releasing PrP from the cell surface. Antibody 6H4 or PIPLC was added to the medium at various concentrations 2 h before and during exposure of N2a/Bos2 cells to 0.1% scrapie-infected brain homogenate. After 3 days, the cells were washed and further cultured for 2 weeks, splitting 1:5 every 3–4 days. During this period, antibody, but not PIPLC treatment, was continued. As assayed by the blotting procedure after 14 days, antibody 6H4 at 2.5 μg/ml and PIPLC at 0.25 unit/ml sufficed to prevent appearance of PrPSc (Fig. 2a).

Figure 2.

Anti-PrP antibody 6H4 and PIPLC prevent infection of N2a/Bos2 cell with scrapie prions and abrogate PrPSc accumulation in chronically infected cells. (a) N2a/Bos2 cells were incubated for 2 h with antibody 6H4 or PIPLC at the concentrations indicated and exposed to 0.1% scrapie-infected brain homogenate (final concentration) for 3 days. After culturing for 14 days (3 passages) in the absence of PIPLC or in the continued presence of 6H4, PrPSc expression was determined (14). (b and c) Chronically scrapie-infected N2a/Bos2 cells were cultured for 3 days on coverslips, without splitting, at the levels of antibody 6H4 or of PIPLC indicated (b) or 14 days (three passages) at the concentrations of antibody 6H4 indicated (c), and PrPSc accumulation was monitored. (d) Chronically scrapie-infected N2a/Bos2 cells were exposed to 6H4 at the concentrations indicated for 2 weeks and further cultured in the absence of the antibody for 6 weeks. Cultures were split 1:5 every 3–4 days. There is no reappearance of PrPSc. “Cell staining” refers to staining of the membranes with ethidium bromide to monitor efficiency of transfer of the cell layer. UN, uninjected; IN, chronically scrapie-infected N2a/Bos2 cells.

Rapid Loss of PrPSc Elicited by Anti-PrP Monoclonal Antibody 6H4 and PIPLC.

Chronically prion-infected N2a/Bos2 cells were exposed to various concentrations of antibody 6H4 or PIPLC and cultured on coverslips without passaging. After 3 days, PrPSc was barely detectable in the case of 6H4 at 3 μg/ml and PIPLC at 0.25 unit/ml (Fig. 2b). No toxic effects were observed. Two other IgG1 monoclonal antibodies, anti-desmin and anti-β-actin, at concentrations up to 5 μg/ml, did not affect PrPSc levels (data not shown). After culturing for 2 weeks, splitting 1:5 every 3–4 days, as little as 1 μg/ml 6H4 led to disappearance of PrPSc (Fig. 2c).

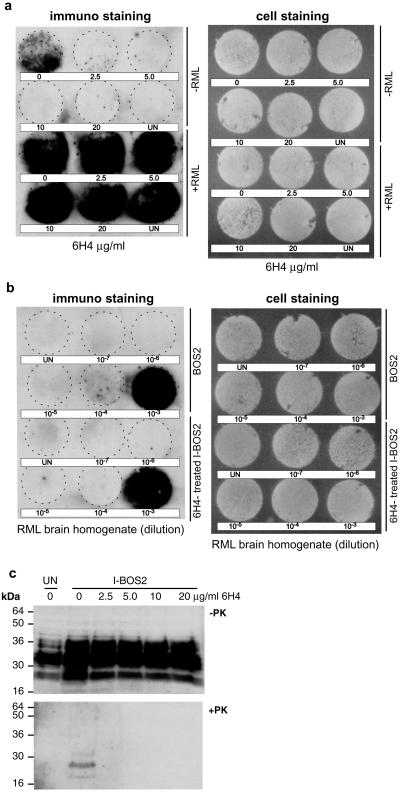

To determine whether the depletion of PrPSc was transient or permanent, chronically infected N2a/Bos2 cells were cultured for 2 weeks with various concentrations of antibody 6H4 and subsequently in its absence. Samples assayed 2, 4 (data not shown), or 6 weeks (Fig. 2d) after removal of the antibody were devoid of PrPSc, in contrast to the chronically infected, untreated cells. “Cured” cells were still susceptible to scrapie prion infection (Fig. 3 a and b) and expressed PrPC at the original level (Fig. 3c).

Figure 3.

Chronically infected N2a/Bos2 cells “cured” of PrPSc by antibody 6H4 treatment continue to produce PrP and are susceptible to reinfection. (a) Chronically infected N2a/Bos2 cells, treated with antibody 6H4 for 2 weeks at the concentrations indicated and propagated in its absence for 66 days were not exposed (upper 2 rows) or exposed to 0.1% RML-infected mouse brain homogenate for 3 days (lower 2 rows). After culturing for 14 days, PrPSc was monitored by the cell blot assay. (b) Relative susceptibility to prions of N2a/Bos2 cells (BOS2) and N2a/Bos2 cells “cured” by exposure to antibody 6H4 at 20 μg/ml was determined by exposing cultures to various dilutions of RML-infected mouse brain homogenate for 3 days and determining PrPSc as above. (c) Levels of PrPC and PrPSc in various sublines were determined by Western blotting. Chronically infected N2a/Bos2 cells, treated for 2 weeks with antibody 6H4 at the concentrations indicated, were passaged for 84 days after antibody withdrawal. Cells were lysed and samples corresponding to 2.25 × 105 cells were incubated in the presence (+PK) or absence (−PK) of proteinase K (5 μg/ml) for 90 min at 37°C. Western blotting was performed as described in Materials and Methods. UN, uninfected N2a/Bos2 cells; I-BOS2, chronically prion-infected BOS2 cells. Molecular mass markers are indicated at the left of each panel.

Discussion

Expression of PrPC is essential, albeit not sufficient (26, 27), for prion propagation and pathogenesis (23, 24), as well as for neuroinvasion after peripheral infection (28). Surprisingly, the N2a line most susceptible to RML prions we identified expressed PrPC at low levels compared with prion-resistant N2a sublines overexpressing PrPC.

It was suggested early on that suppression of PrP expression might be an approach to the therapy of prion diseases (23). Several drugs have been shown to diminish or abolish PrPSc in prion-infected cell cultures, for instance Congo red (29), polyene compounds such as amphothericin (30), pentosan sulfate (31), branched polyamines (32), and β-sheet-breaking peptides (33), to mention but a few. In some instances these drugs delayed, but never prevented, the appearance of clinical symptoms and death in experimental animals (34, 35).

Several mechanisms may lead to PrPSc depletion: prevention of PrPC to PrPSc conversion by stabilization of PrPC, interference with the interaction of PrPC and PrPSc (36), or sequestration and/or reversion of PrPSc to a protease-sensitive state (33). In addition, abrogation of PrPC synthesis or prevention of transport to the cell surface could interrupt prion propagation.

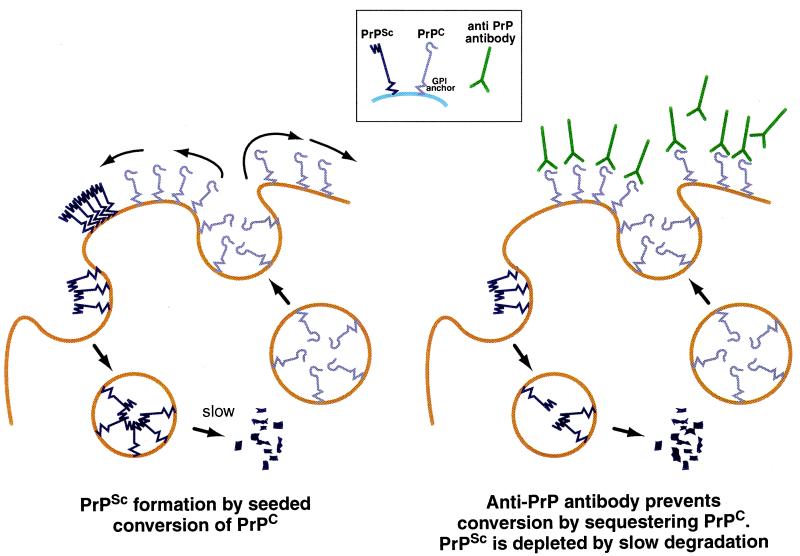

In our experiments, 6H4 prevents PrPSc formation either by occluding PrPC or PrPSc or both and thereby preventing conversion (Fig. 4). The finding that exposure of chronically infected N2a cells to PIPLC (or anti-PrP antibody 6H4) causes PrPSc to disappear almost completely in the course of 3 days, even without splitting of the culture, leads to the conclusion that PrPSc is rapidly degraded, while the antibody prevents formation of further PrPSc. Pulse-labeling experiments on N2a cells showed that exposure of scrapie-infected N2a cells to PIPLC prevents the formation of radioactive PrPSc (37, 38) and indicated a half-life of >24 h (37), longer than that suggested by our experiments. Because removal of PrPC from the cell surface by PIPLC has the same effect as exposure to PrP antibody, occlusion of PrPC by antibody binding suffices to explain its effect.

Figure 4.

Model to explain abolition of PrPSc by anti-PrP antibody (or PIPLC). PrPC is attached to the membrane by a glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchor, and it cycles between the cell surface and an endocytic compartment (43). In scrapie-infected cells, PrPC is recruited into PrPSc “seeds” (44), which may be located at the cell surface and/or in the endocytic/lysosomal compartment. PrPSc is degraded in the lysosomal compartment; if PrPC is prevented from converting to PrPSc either by a blocking antibody or by being stripped from the cell surface by PIPLC, PrPSc will diminish and ultimately disappear.

The findings that in transgenic mouse models of Alzheimer's disease immunization with amyloid-β protein (Aβ) causes a marked reduction in burden of the brain amyloid (39, 40), and that antibodies against the Alzheimer peptide Aβ penetrate the brain–blood barrier and lead to reversal of amyloid deposition (41, 42), suggest that active or passive immunization to PrP might have a beneficial effect in prion diseases.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. P.-C. Klöhn for his help, and Dr. J. Collinge for support and encouragement. This work was funded by the Medical Research Council.

Abbreviations

- PIPLC

phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C

- PrPC

cellular form of prion protein

- PrPSc

scrapie form of prion protein

- RML

Rocky Mountain Laboratory

References

- 1.Prusiner S B. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1989;43:345–374. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.43.100189.002021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oesch B, Westaway D, Wälchli M, McKinley M P, Kent S B, Aebersold R, Barry R A, Tempst P, Teplow D B, Hood L E, et al. Cell. 1985;40:735–746. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90333-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chesebro B, Race R, Wehrly K, Nishio J, Bloom M, Lechner D, Bergstrom S, Robbins K, Mayer L, Keith, et al. Nature (London) 1985;315:331–333. doi: 10.1038/315331a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Basler K, Oesch B, Scott M, Westaway D, Wälchli M, Groth D F, McKinley M P, Prusiner S B, Weissmann C. Cell. 1986;46:417–428. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90662-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vey M, Pilkuhn S, Wille H, Nixon R, DeArmond S J, Smart E J, Anderson R G, Taraboulos A, Prusiner S B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:14945–14949. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harmey J H, Doyle D, Brown V, Rogers M S. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;210:753–759. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McKinley M P, Meyer R K, Kenaga L, Rahbar F, Cotter R, Serban A, Prusiner S B. J Virol. 1991;65:1340–1351. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.3.1340-1351.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stahl N, Baldwin M A, Teplow D B, Hood L, Gibson B W, Burlingame A L, Prusiner S B. Biochemistry. 1993;32:1991–2002. doi: 10.1021/bi00059a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Markovits P, Dormont D, Delpech B, Court L, Latarjet R. C R Seances Acad Sci III. 1981;293:413–417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Race R E, Fadness L H, Chesebro B. J Gen Virol. 1987;68:1391–1399. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-68-5-1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Butler D A, Scott M R, Bockman J M, Borchelt D R, Taraboulos A, Hsiao K K, Kingsbury D T, Prusiner S B. J Virol. 1988;62:1558–1564. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.5.1558-1564.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schätzl H M, Laszlo L, Holtzman D M, Tatzelt J, DeArmond S J, Weiner R I, Mobley W C, Prusiner S B. J Virol. 1997;71:8821–8831. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.11.8821-8831.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vilette D, Andreoletti O, Archer F, Madelaine M F, Vilotte J L, Lehmann S, Laude H. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:4055–4059. doi: 10.1073/pnas.061337998. . (First Published March 20, 2001; 10.1073/pnas.061337998) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bosque P J, Prusiner S B. J Virol. 2000;74:4377–4386. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.9.4377-4386.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nishida N, Harris D A, Vilette D, Laude H, Frobert Y, Grassi J, Casanova D, Milhavet O, Lehmann S. J Virol. 2000;74:320–325. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.1.320-325.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Korth C, Stierli B, Streit P, Moser M, Schaller O, Fischer R, Schulz-Schaeffer W, Kretzschmar H, Raeber A, Braun U, et al. Nature (London) 1997;390:74–77. doi: 10.1038/36337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bolton D C, Bendheim P E, Marmorstein A D, Potempska A. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1987;258:579–590. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(87)90380-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Southern P J, Berg P. J Mol Appl Genet. 1982;1:327–341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murai K, Murakami H, Nagata S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:3461–3466. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fischer M, Rülicke T, Raeber A, Sailer A, Moser M, Oesch B, Brandner S, Aguzzi A, Weissmann C. EMBO J. 1996;15:1255–1264. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scott M, Groth D, Foster D, Torchia M, Yang S L, DeArmond S J, Prusiner S B. Cell. 1993;73:979–988. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90275-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scott M R, Kohler R, Foster D, Prusiner S B. Protein Sci. 1992;1:986–997. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560010804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Büeler H, Aguzzi A, Sailer A, Greiner R A, Autenried P, Aguet M, Weissmann C. Cell. 1993;73:1339–1347. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90360-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sailer A, Büeler H, Fischer M, Aguzzi A, Weissmann C. Cell. 1994;77:967–968. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90436-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scott M, Foster D, Mirenda C, Serban D, Coufal F, Walchli M, Torchia M, Groth D, Carlson G, DeArmond S J, et al. Cell. 1989;59:847–857. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90608-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Raeber A J, Sailer A, Hegyi I, Klein M A, Rulicke T, Fischer M, Brandner S, Aguzzi A, Weissmann C. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:3987–3992. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.3987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Montrasio F, Cozzio A, Flechsig E, Rossi D, Klein M A, Rulicke T, Raeber A J, Vosshenrich C A, Proft J, Aguzzi A, Weissmann C. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:4034–4037. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051609398. . (First Published March 13, 2001; 10.1073/pnas.051609398) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blättler T, Brandner S, Raeber A J, Klein M A, Voigtlander T, Weissmann C, Aguzzi A. Nature (London) 1997;389:69–73. doi: 10.1038/37981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Caughey B, Race R E. J Neurochem. 1992;59:768–771. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1992.tb09437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pocchiari M, Schmittinger S, Masullo C. J Gen Virol. 1987;68:219–223. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-68-1-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Caughey B, Raymond G J. J Virol. 1993;67:643–650. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.2.643-650.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Supattapone S, Wille H, Uyechi L, Safar J, Tremblay P, Szoka F C, Cohen F E, Prusiner S B, Scott M R. J Virol. 2001;75:3453–3461. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.7.3453-3461.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Soto C, Kascsak R J, Saborio G P, Aucouturier P, Wisniewski T, Prelli F, Kascsak R, Mendez E, Harris D A, Ironside J, et al. Lancet. 2000;355:192–197. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)11419-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Priola S A, Raines A, Caughey W S. Science. 2000;287:1503–1506. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5457.1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Adjou K T, Privat N, Demart S, Deslys J P, Seman M, Hauw J J, Dormont D. J Comp Pathol. 2000;122:3–8. doi: 10.1053/jcpa.1999.0338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Caspi S, Halimi M, Yanai A, Sasson S B, Taraboulos A, Gabizon R. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:3484–3489. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.6.3484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Borchelt D R, Scott M, Taraboulos A, Stahl N, Prusiner S B. J Cell Biol. 1990;110:743–752. doi: 10.1083/jcb.110.3.743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Caughey B, Raymond G J. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:18217–18223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Janus C, Pearson J, McLaurin J, Mathews P M, Jiang Y, Schmidt S D, Chishti M A, Horne P, Heslin D, French J, et al. Nature (London) 2000;408:979–982. doi: 10.1038/35050110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Games D, Bard F, Grajeda H, Guido T, Khan K, Soriano F, Vasquez N, Wehner N, Johnson-Wood K, Yednock T, et al. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;920:274–284. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bard F, Cannon C, Barbour R, Burke R L, Games D, Grajeda H, Guido T, Hu K, Huang J, Johnson-Wood K, et al. Nat Med. 2000;6:916–919. doi: 10.1038/78682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bacskai B J, Kajdasz S T, Christie R H, Carter C, Games D, Seubert P, Schenk D, Hyman B T. Nat Med. 2001;7:369–372. doi: 10.1038/85525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shyng S L, Huber M T, Harris D A. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:15922–15928. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lansbury P T, Caughey B. Chem Biol. 1995;2:1–5. doi: 10.1016/1074-5521(95)90074-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]