Abstract

Various studies have established the possibility of non-bacterial methane (CH4) generation in oxido-reductive stress conditions in plants and animals. Increased ethanol input is leading to oxido-reductive imbalance in eukaryotes, thus our aim was to provide evidence for the possibility of ethanol-induced methanogenesis in non-CH4 producer humans, and to corroborate the in vivo relevance of this pathway in rodents. Healthy volunteers consumed 1.15 g/kg/day alcohol for 4 days and the amount of exhaled CH4 was recorded by high sensitivity photoacoustic spectroscopy. Additionally, Sprague-Dawley rats were allocated into control, 1.15 g/kg/day and 2.7 g/kg/day ethanol-consuming groups to detect the whole-body CH4 emissions and mitochondrial functions in liver and hippocampus samples with high-resolution respirometry. Mitochondria-targeted L-alpha-glycerylphosphorylcholine (GPC) can increase tolerance to liver injury, thus the effects of GPC supplementations were tested in further ethanol-fed groups. Alcohol consumption was accompanied by significant CH4 emissions in both human and rat series of experiments. 2.7 g/kg/day ethanol feeding reduced the oxidative phosphorylation capacity of rat liver mitochondria, while GPC significantly decreased the alcohol-induced CH4 formation and hepatic mitochondrial dysfunction as well. These data demonstrate a potential for ethanol to influence human methanogenesis, and suggest a biomarker role for exhaled CH4 in association with mitochondrial dysfunction.

Introduction

Mammalian methanogenesis is regarded as a specific indicator of carbohydrate fermentation by the intestinal anaerobic microflora. It is also accepted that the bulk of methane (CH4) production is excreted via the lungs, and therefore changes in breath CH4 output are widely used for the diagnosis of certain gastrointestinal (GI) malabsorption conditions1. Nevertheless, the pulmonary route is not exclusive since a uniform CH4 release can be detected through the skin in healthy individuals2. It is also noteworthy that two distinct human populations are revealed with the diagnostic breath tests, CH4-producers and non-producers, when production is usually being defined as a >1 ppm increase above the atmospheric CH4 concentration3. Besides, a recent study using stable carbon isotope signatures provided clear evidence that the exhaled CH4 levels are always above the inhaled CH4 concentration, supporting the idea that all individuals might produce endogenous CH4 which cannot be detected by conventional analytical techniques4.

Of interest, the in vivo methane formation cannot be restricted to prokaryotes because various in vitro and in vivo experimental data have established the possibility of biotic, non-bacterial generation of CH4 under various stress conditions in plants and animals also5–10. In this line, significant in vivo CH4 release was demonstrated in a rodent model of chemical asphyxiation, after chronic inhibition of the activity of mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase11.

Collectively these findings suggested us that CH4 excretion in mammals may reflect bacterial and non-bacterial methanogenesis as well. In this context, the primary objective of the present study was to provide evidence for the opportunity of alternative, non-conventional CH4 production in humans. Since an increased ethanol input is a common way to induce hepatic oxido-reductive imbalance in man12, we set out to investigate the possibility of CH4 generation in previously non-methane producer volunteers consuming high doses of ethanol. For the detection of in vivo CH4 output we employed a high sensitivity, near-infrared laser technique-based photoacoustic spectroscopy (PS) system, which has previously been validated for real-time measurements of CH4 emissions in human and animal studies11, 13.

A further aim was to extend the scope of the human protocol in a comparable animal model of ethanol challenge. It has been shown that excessive ethanol intake may lead to a transient failure of the mitochondrial electron transport chain (METC) leading to oxidative membrane damage14–17 in humans and rodents18, thus we set out to collect analogous animal data on ethanol-induced CH4 generation in association with mitochondrial functional failure in the liver and hippocampus tissue.

The functional consequence of endogenous CH4 production is subject of debate. We hypothesized that if CH4 production is induced from target cellular components, a greater understanding of a process that modulates this response would be of interest. L-alpha-glycerylphosphorylcholine (GPC) is a water-soluble deacylated metabolite of membrane-forming phosphatidylcholine (PC) and a source of choline19–21. Interestingly, significantly lower concentrations of hepatic GPC have been reported after experimental haemorrhagic shock, a prototype of systemic hypoxia and mitochondrial dysfunction22 and our earlier in vivo findings demonstrated that GPC is protective against several signs of hypoxia- or redox-imbalance-induced tissue injuries11, 23, 24. Thus, in the next part of the rat study we examined the hypothesis that GPC may influence CH4 production through the modulation of alcohol-induced mitochondrial dysfunction.

Results

Human breath CH4 analysis

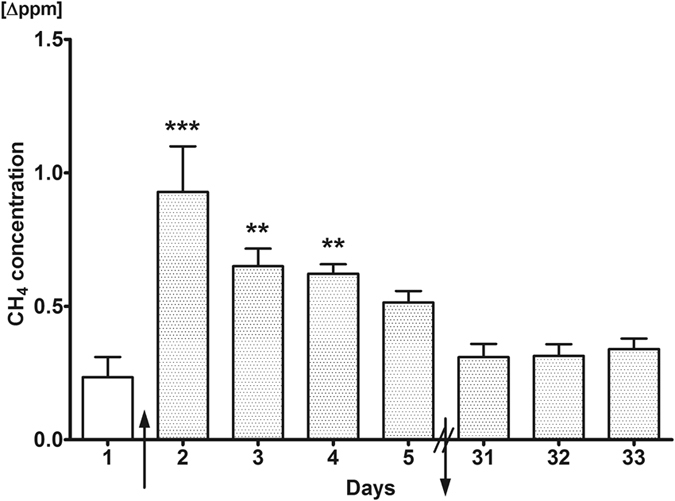

The possibility of ethanol-induced methanogenesis was monitored in previously non-CH4 producer individuals under standardized circumstances. The breath CH4 concentration was significantly elevated by approx. 0.9 Δppm on day 2 (0.93 ± 0.17 Δppm), day 3 (0.65 ± 0.07 Δppm) and day 4 (0.62 ± 0.04 Δppm), as compared to the baseline (day 1, 0.23 ± 0.08 Δppm). The CH4 output was decreasing by day 5 (0.51 ± 0.04 Δppm) but remained significantly higher over the baseline. When the breath CH4 analysis was repeated 31 days later, statistically significant CH4 production was not detected (see Fig. 1 ).

Figure 1.

Exhaled CH4 production profile of humans during the course of the study. Exhaled CH4 production on days 1–5 and 31–33 of the investigation is depicted. During the first measurement on day 1, all volunteers were untreated. Alcohol consumption induced significant CH4 production by the 2nd day compared to the 1st day, and this level decreased remarkably by the 5th day. Mean values and standard error of mean (SEM) are given; **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001 vs. day 1. The arrows pointing upwards and downwards represent start and end of alcohol intake, respectively. Statistics: one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparison test.

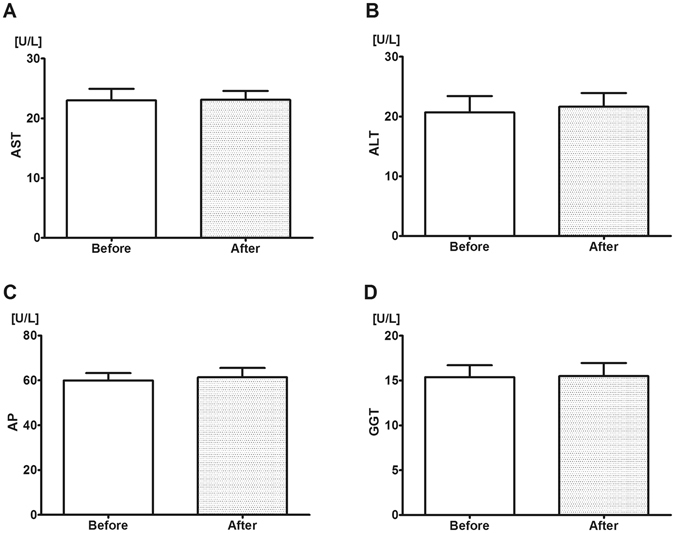

Liver-specific enzymes

Clinically established enzyme markers were used to monitor the liver function before and after the 4-days alcohol intake. Statistically significant changes were not observed in these parameters (see Fig. 2 ).

Figure 2.

Liver-specific enzyme levels before and after alcohol consumption in humans. Enzyme levels were determined in plasma from blood samples taken on days 1 (control, left boxes) and 5 (last day of alcohol consumption, right boxes) of the investigation. During the first measurement, all volunteers were untreated. (A) Aspartate aminotransferase (AST), (B) Alanine aminotransferase (ALT), (C) Alkaline phosphatase (AP) and (D) Gamma glutamyl transferase (GGT) levels. Alcohol consumption did not alter enzyme levels. Mean values and standard error of mean (SEM) are given; p < 0.05 vs. day 1 (control). Statistics: Paired-test.

CH4 release in rats

In a forward step, we followed the whole-body CH4 profile of rats during several days of alcohol consumption (see Fig. 3 ). This study has shown increased CH4 output (1.85 ± 0.48 Δppm/1000 dm2) compared to the control group on 3 day after an intake of 1.15 g/kg/day ethanol and this level was sustained until the end of the 8-days observation period (2.47 ± 1.29 Δppm/1000 dm2). However, no elevation in CH4 levels was seen in the 1.15 g/kg/day ethanol + GPC treated group compared to controls. By day 8, there was already a significant difference between the group with 1.15 g/kg/day ethanol without GPC (2.47 ± 1.29 Δppm/1000 dm2) and the group with GPC treatment (0.04 ± 0.04 Δppm/1000 dm2).

Figure 3.

Whole-body CH4 release of rats. Whole body CH4 production was measured on days 1, 3, 5, and 8 of the investigation. Ethanol feeding induced significant CH4 production by the 3rd day in the 1.15 g/kg/day alcohol-treated group and by the 5th day in the 2.7 g/kg/day alcohol-treated group, compared to control group. However, in the GPC-treated groups no increase was observed as compared to controls. Empty circles with continuous line relates to control group, black triangles with continuous line to the 1.15 g/kg/day alcohol-treated group, empty triangles with dashed line to the 1.15 g/kg/day alcohol + GPC-treated group, black squares with continuous line to 2.7 g/kg/day alcohol-treated group, and empty squares with dashed line to the 2.7 g/kg/day alcohol + GPC-treated group. During the measurement on day 1, all the rats were untreated. Mean values and standard error of mean (SEM) are given; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001 vs. Control group, ###p < 0.001 vs. corresponding GPC-treated groups. Statistics: Two-way ANOVA, Bonferroni post-hoc test.

By day 5, the 2.7 g/kg/day-ethanol load increased the whole-body generation of CH4 (2.3 ± 0.43 Δppm/1000 dm2), and the high CH4 production was kept up until the end of the 8-days experiments (1.03 ± 0.33 Δppm/1000 dm2). Similar to the low-dose ethanol + GPC, CH4 release in the 2.7 g/kg/day ethanol + GPC-treated group did not differ from controls. No changes were observed in the untreated control group during the observation period (day 8: 0.23 ± 0.18 Δppm/1000 dm2) as compared to baseline levels on day 1.

Mitochondrial function in the rat liver and hippocampus

The oxidative phosphorlylation capacity of METC in liver and brain homogenates was analyzed with high-resolution respirometry with saturating succinate and ADP concentrations (see Figs 4 and 5).

Figure 4.

Oxygen consumption of rat liver mitochondria. O2 consumption rate of mitochondria was assessed in liver homogenate after addition of 0.5 μM rotenone, 10 mM succinate and 2.5 mM ADP on day 9 of investigation. The 2.7 g/kg/day ethanol-fed group had decreased mitochondrial function compared to control, whereas the GPC treatment prevented the decline of mitochondrial oxygen consumption, demonstrated by higher levels compared to both non-GPC treated ethanol-fed groups. Mean values and standard error of mean (SEM) are given; **p < 0.01 vs. Control, #p < 0.05 vs. corresponding GPC-treated groups. Statistics: One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc test.

Figure 5.

Oxygen consumption of rat hippocampus mitochondria. O2 consumption rate of mitochondria was assessed in hippocampus homogenate after addition of 0.5 μM rotenone, 10 mM succinate and 2.5 mM ADP on day 9 of investigation. Mitochondrial respiratory capacity deteriorated upon alcohol intake regardless of GPC treatment. Mean values and standard error of mean (SEM) are given; ***p < 0.001 vs. Control. Statistics: One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc test.

In the liver, intake of 1.15 g/kg/day alcohol did not influence mitochondrial oxygen consumption as compared to control group (26.17 ± 2.45 pmol/s/mg protein vs 31.79 ± 1.74 pmol/s/mg protein), while 2.7 g/kg/day ethanol challenge resulted in a significant reduction in oxidative phosphorylation capacity (19.29 ± 1.73 pmol/s/mg). Dietary supplementation of GPC lead to an increase in respiration in both groups compared to their non-GPC-treated counterparts (1.15 g/kg/day alcohol + GPC: 38.08 ± 4.99 pmol/s/mg protein; 2.7 g/kg/day alcohol + GPC: 31.66 ± 8.11 pmol/s/mg protein).

The alcohol challenge significantly compromised the mitochondrial oxygen uptake in the hippocampus as well (Figs 4 and 5), and GPC treatment did not influence the change in this tissue.

Liver-specific enzyme levels in the rat plasma

The plasma levels of liver-specific enzymes were monitored before and after the 1.15 g/kg/day oral alcohol intake regime to obtain comparable data with the human study. The ALT and AST plasma levels increased from 34.6 U/L to 41.5 U/L and from 62.5 U/L to 80.3 U/L, respectively, while the AP levels did not change. The plasma enzymes levels in the GPC-treated group showed similar changes over time, as the values of ALT rose from 34.8 U/L to 53 U/L and the concentration of AST elevated from 61.5 U/L to 71.3 U/L, while the AP levels did not change (see Fig. 6). GGT was not measured in rat plasma samples due of methodological limitations.

Figure 6.

Liver-specific enzyme levels before and after alcohol consumption in rats. Enzyme levels were determined in plasma from blood samples taken on days 1 (untreated control, left boxes) and 8 (last day of alcohol treatment, right boxes) of the investigation. The 1.15 g/kg/day alcohol (panels A–C) and 1.15 g/kg/day alcohol + GPC-fed group (panels D–F) were monitored with same method. Both Aspartate aminotransferase (AST, panels A and D) and Alanine aminotransferase (ALT, panels B and E) levels increased significantly as compared to baseline. Alkaline phosphatase (AP, panels C and F) levels did not change. Mean values and standard error of mean (SEM) are given; *p < 0.05 vs. day 1 (Control). Statistics: Paired t-test.

Discussion

Methanogenesis in humans has been considered an exclusive attribute of methanogenic Archaea, a group well distinguished from the usual bacteria and the eukaryotes. These strictly anaerobic inhabitants of the GI tract are producing CH4 from decomposing organic matter through hydrogenotrophic, methylotrophic and acetotrophic classes of methanogenesis25. Nevertheless, to-date a number of studies have demonstrated the generation of non-bacterial CH4 also in aerobic living systems5, 6, 9, and it has also been suggested that the CH4-producing phenomenon can be in association with transient losses of redox homeostasis7, 8. Indeed, the administration of sodium azide (NaN3) leads to an increasing emanation of endogenous CH4 in plant and animal cells and whole animal organisms11, 26. The main effect of NaN3 in eukaryotes is its direct and irreversible binding to the heme cofactor of cytochrome c oxidase, the final electron acceptor of the METC; thus it can also be considered a tool via which to study mitochondrial oxido-reductive stress.

This study reports a combination of observational and experimental data on ethanol-induced CH4 generation, and to our knowledge, these results provide the first evidence for increased in vivo CH4 output after such manipulation. It should be added that analysis of exhaled breath samples is widely used in the clinical practice for the screening of patients, where the detection of CH4 concentration changes relative to other gaseous compounds can promote the diagnosis; the amount of exhaled H2 and CH4 proves that a carbohydrate substrate has been exposed to bacterial fermentation1, 27. However, Keppler et al. demonstrated that CH4 was produced by all of the human subjects studied4. Using laser absorption spectroscopy and stable carbon isotopes to precisely measure exhaled and inhaled CH4 concentrations in various age groups, evidence was presented that humans might also produce CH4 endogenously in cells4. Our results do not exclude the role of microorganisms or do not negate the validity of breath-testing-based diagnostic methods but also suggest that other factors and pathways need to be also taken into account in the background of mammalian CH4 generation. One of the possibilities is alcohol consumption.

In our studies the relatively high ethanol intake was followed by significant whole-body CH4 release in previously non-producer animals, and also in humans, the non-CH4 producer phenotype was “transformed” to CH4 producer. These parallel results do suggest that CH4 production may occur in vivo independently from the gut microbiome, but the bacterial origin cannot be excluded with certainty (see Supplementary Figure 1, as well). In the complex ecosystem of the GI tract, methanogens are compelled to compete with other microorganisms, such as sulphate-reducing bacteria for the common substrates in the human colon28. Bacterial enzymatic CH4 is formed when CO2 is reduced by electron donor H2 produced by anaerobic fermentation. Ethanol can be substrate for some methanogens as demonstrated in a recent in vitro study with different peatland methanogenic bacteria to use ethanol and acetate as substrate29. Although some studies examined the relation between alcohol consumption and gut microbiome composition in humans, specific information on the response of methanogenic bacteria is lacking30, 31. Nevertheless, prolonged alcohol consumption can alter the composition and function of colon microbiome, and in turn, the gut microbiome can have a profound impact on alcohol metabolism as well30.

In the clinical laboratory practice breath CH4 levels are usually analyzed by means of gas chromatography (GC) and GC-mass spectrometry, but these traditional methods have technical limitations32. The PAS system was tested for whole-body and single breath CH4 analyses in previous surveys11, 13, and the online detected CH4 changes have proved to be reproducible and highly specific for CH4 in a wide dynamic range13.

Today it is accepted that the CH4 concentration in the breath is usually greater than 1 ppm in 30–60% of humans3, 33. Our data suggest that large differences in breath gas analysis data are presumably not only due to the variations in the personal background, bacterial strains, sampling and analysis techniques, but other cause as well. Nevertheless, if nonbacterial CH4 is mixed with bacterial CH4 production, this addition is not easy to identify and recognize. To elucidate whether a similar process of CH4 generation exist in humans and rats, we have chosen a standardized, reversible mitochondrial stress induction procedure. Indeed, hepatic and hippocampal METC functions were affected significantly as evidenced by the direct mitochondrial analysis in the rat. It is known that alcohol consumption influences the activities of respiratory chain complexes II and III in the mouse brain34, and decreases the state III respiration and the respiratory control ratio in the liver of ethanol-fed animals35. Here we demonstrate that the complex II-linked state III respiration decreased significantly both in the liver and the hippocampus as compared to the control group. The ethanol challenge decreased the complex II-linked oxygen consumption of liver mitochondria in a dose-dependent manner, while this inhibitory effect was much more pronounced in the hippocampus already after the lower ethanol dosage. What is more, GPC administration did not improve the respiratory capacity of hippocampal mitochondria. GPC is a mitochondria-targeted compound which enhances mitochondrial oxygen consumption in hepatocytes36 and it has been shown that GPC can rapidly cross the blood-brain barrier20, 37. A possible explanation for these differences is provided by the higher susceptibility of hippocampal neurons and/or mitochondria towards the ethanol input and the organ-specific impact of ethanol-induced oxidative stress on mitochondria of these cell types38, 39.

The plasma concentrations of liver-specific enzymes were measured to provide an overview of the metabolic function of the liver after the transient ethanol challenge. AST and ALT are located normally in the cytoplasm of hepatocytes, and upon membrane damage a portion of the intracellular aminotransferases leak into the extracellular fluid40. The plasma levels of AST and ALT did not change in human volunteers after the 4 days of regular alcohol consumption, while a slight but significant (approx. 10–30%) increase in AST and ALT levels was detected in ethanol-fed rats. Inter-species variations and liver-specific reactions in ethanol metabolism and tolerance cannot be excluded, but these data suggest that the severity of alcohol-induced metabolic stress only slightly exceeded the hepatocellular injury threshold, and the model was associated only with a reversible hepatic functional imbalance in both species.

A transient, significant CH4 production was the appropriate answer to ethanol intake in both experimental series, and there is supporting data in the literature that METC dysfunction can be accompanied by CH4 generation8. The initial in vitro studies led to the proposal that electrophilic methyl groups (EMG) bound to positively charged nitrogen moieties (as in choline molecules) may potentially act as electron acceptors, during reductive stress conditions and that these reactions may entail the generation of CH4 5, 6. Liver NAD+/NADH + H+ changes are characteristically increased after alcohol intake41. Most of the alcohol is metabolized to acetaldehyde by alcohol dehydrogenase in the cytoplasm of hepatocytes and the catalyzer is NAD+ which is transformed to NADH + H+. Acetaldehyde is transformed further to carboxylic acid by aldehyde dehydrogenase meanwhile the system uses more NAD+ and water. The resultant increasing NADH + H+ level leads to reductive stress41, 42. In addition, alcohol exposure can both affect gene expressions and activity of S-adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase42, 43, and may change the methionine metabolism leading to intracellular S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) and S-adenoslyhomocystenine (SAH) increases42. Thus, the ethanol-induced imbalance of NADH can be an important key to the genesis of SAH and SAM. Moreover, the system produces CH4 during this reaction.

It should be added that reversible methionine oxidation could be a mechanism of redox- regulation, which involves the action of methionine sulfoxide reductases (MSR) whose main function is to protect membranes from oxidative damage44. Nevertheless, methionine and methionine sulfoxide exhibit high CH4-formation ability in vitro, without enzymes to catalyze the reaction44, and the sulfur-bonded CH3 group in methionine was unambiguously identified by stable isotope labeling techniques as the carbon precursor of the CH4 molecule in fungi under aerobic conditions45. In this line, a chemical reaction was recently described by Althoff et al. where CH4 is readily formed from the S-CH3 groups of organosulphur compounds in a model system containing iron(II/III), H2O2 and ascorbate that uses organic compounds with heterobonded CH3 groups for the generation under ambient (1.000 mbar and 22 °C) and aerobic (21% O2) conditions46, 47.

The role of choline in aerobic CH4 formation was also substantiated in previous in vivo and in vitro experiments. Exogenous phosphatidylcholine (PC) and choline metabolites can suppress the methanogenic reaction8, and similarly, when GPC, a water-soluble, deacylated PC derivative was administered in NaN3-induced chemical hypoxia, the extent of CH4 generation was reduced11. GPC is a bioavailable source of choline48, which can be directly or indirectly involved in the preservation of membranes in ischemic tissue damage49. The exact mechanism of GPC interference with the liver oxidative phosphorylation capacity is still unclear. Nevertheless, choline metabolites are involved in the preservation of the structural integrity of cellular membranes50. More importantly it has been shown that a choline deficiency impairs complex I (NADH dehydrogenase)-linked respiration51. Indeed, in our study exogenous GPC protected against the ethanol-induced METC dysfunction in the rat liver, the primary target of alcohol-induced oxido-reductive stress. There is evidence suggesting a direct action of GPC on mitochondrial complex II-linked respiration. After oral intake GPC is hydrolysed by phosphodiesterases in the intestinal mucosa20 and in liver as well52 producing choline and glycerol-3-phosphate (G3P). G3P can be directly oxidised by G3P-shuttle (G3P dehydrogenase) feeding FADH2 to mitochondrial complex II and enhancing mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation. We did not test to see whether GPC supplementation improves complex I-linked respiration, but this aspect definitely deserves elucidation in the future. Since it has been shown that GPC rapidly delivers both choline and glycerol to the brain across the blood–brain barrier20, 51 we have expected similar effectiveness in the central nervous system too, but this approach did not improve the respiratory capacity of hippocampal mitochondria. We speculate that maybe even the lower dose of ethanol did damage the sensitive pyramidal cells of the hippocampus so severe that GPC could not prevent loss mitochondrial respiratory function. As the reason for this finding is unclear, further studies with different doses and timing are clearly needed in this respect23.

Before making the final conclusions, it is important to note the limitations of the experimental setup. Firstly, the exact pathway through which CH4 is liberated after the in vivo alcohol load remained basically unexplored and several sources, bacterial and non-bacterial, can be postulated. In this sense it is still unknown whether the findings in this experimental setup are applicable to other conditions, and the therapeutic significance of GPC administration should be reinforced and reproduced in further studies. Nevertheless, we have provided evidence that transient, high ethanol input leads to significant increases in CH4 formation in previously non-CH4 producer humans, and a similarly high CH4 formation occurs in ethanol-consuming rats, in association with a mitochondrial dysfunction in the liver. Biomarkers are essential clinical tools through which to gain an understanding of human biology or the responses to therapies, and CH4 is regarded as disease-specific routine biomarker. Therefore this type of alternative CH4 formation might be an interesting focus for diagnostic and therapeutic strategies in IR episodes. Much remains unknown about hypoxic reactions and the fate of intracellular CH4 is an open question, but the results presented indicate a biomarker role for CH4.

Materials and Methods

Human protocol

All procedures in this study involving human subjects were in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Human Investigation Review Board of the University of Szeged, Albert Szent-Györgyi Clinical Centre (Institutional Ethical Board approval No. 49/B-165/2014). The participants signed an informed consent and all approved the publication of the data obtained. Healthy men (11 volunteers) with no known underlying disease, 25 to 30 years age (average weight 82 ± 13.1 kg) were included in the study. The participants underwent a general health check with repeated breath analyses (see later). The exclusion criteria were CH4 producer status, smoking, regular alcohol intake or ethanol dependency, competitive sports, liver disease and diabetes. Alcohol intake was not allowed for 3 days prior to the study and the enrolled subjects underwent a baseline measurement of breath ethanol.

On day 1 of the protocol control breath CH4 measurements were carried out, and then the subjects consumed 1.15 g/kg/day alcoholic beverage (200 ml whisky, 40 vol% ethanol content) which was repeated between 6 pm and 7 pm on 4 consecutive days. Breath CH4 measurements were performed every day at a preset time (between 8 am and 9 am) with empty stomach, before the first meal. In order to assess the activity of liver-specific enzymes, 3 ml peripheral venous blood samples were taken into EDTA-containing tubes before the start of alcohol consumption protocol and after the end of the last breath CH4 measurement. The breath CH4 analysis was repeated 31 days later for 3 consecutive days when the subjects did not consume alcohol for at least 3 days before the measurements.

CH4 analysis setup

The CH4 concentration of breath samples was detected by PAS as described previously13. PAS is a special mode of spectroscopy which measures optical absorption indirectly via the conversion of absorbed light energy into acoustic waves. The amplitude of the generated sound is directly proportional to the concentration of the absorbing gas component. The light source of the system is a near-infrared diode laser that emits around the CH4 absorption line at 1650.9 nm with an output power of 15 mW (NTT Electronics, Tokyo, Japan). Cross-sensitivity for common components of breath and ambient air were repeatedly examined, and no measurable instrument response was found for several vol % of CO2 or H2O vapour. The narrow line width of the diode laser provides high selectivity; the absorbance of CH4 is several orders of magnitude greater than that of H2O, CO2 or CO at 1.65 μm, the wavelength we used. The device was previously calibrated with various gas mixtures prepared by dilution of 100 ppm CH4 in synthetic air (Messer, Budapest, Hungary), and it has a dynamic range of 4 orders of magnitude; the minimum detectable concentration of the sensor was found to be 0.25 ppm (3σ), with an integration time of 12 s13.

Breath sampling in humans

The subjects were asked to breathe normally and the expired air was directed into a 200 cm3 glass flask. The optimal time for the attainment of a steady CH4 concentration proved to be between 1 and 3 min with a flow rate of 30 cm3/min. The room air CH4 level was determined and used as baseline in the calculations of in vivo CH4 emission. CH4 production is given in Δppm, referring to the net exhaled CH4 concentration, where the CH4 concentration of the ambient air was deducted from exhaled CH4 concentration.

Rat study

The experiments were performed on male Sprague-Dawley rats (190–300 g bw) in accordance with the National Institutes of Health guidelines on the handling and care of experimental animals and EU Directive 2010/63 for the protection of animals used for scientific purposes. The study protocol was reviewed by the National Scientific Ethical Committee on Animal Experimentation (National Competent Authority of Hungary) and was approved by the Animal Welfare Committee of the University of Szeged (V/148/2013).

Prior to the start of the experiments control whole-body CH4 measurements were carried out (see details later) and non-producer CH4 status (less than 0.3 ppm) animals were included into the study.

A pilot dose-response study was performed with 6 non-CH4 producer rats. These animals were fed per os with alcoholic solutions (40% whisky in gavage up to 2.86 ml/kg/day) for 8 days. The dosage was equivalent to 1.15 g/kg/day ethanol intake which was employed in the human study.

After receiving standard dose-responses, 24 non-CH4 producer rats were randomly allocated into four groups. Group 1 (n = 6) served as non-treated control, in Group 2 (n = 6) the animals received 1.15 g/kg/day alcohol with supplemented oral GPC feeding (0.8% GPC-enriched diet, Ssniff Spezialdiäten GmbH, Soest, Germany), in Group 3 (n = 6), the animals received 7.5 ml/kg/day 40% alcoholic solution per os for 8 days in daily gavage. This dose is equivalent to 2.7 g/kg/day ethanol intake, which has been reported to lead hepatic oxido-reductive stress reproducibly in rats47–49. In Group 4 (n = 6), the identical alcohol input (7.5 ml/kg/day) was supplemented with oral GPC feeding for 8 days.

The whole-body CH4 emission of the animals was measured in a specially-designed closed sampling chamber with an internal volume of 2510 cm3 as reported previously13. Prior to the experiments the CH4 concentration in the chamber was determined and used as baseline value. By means of a membrane pump (Rietschle Thomas, Puchheim, Germany) and a mass-flow controller, a sample of the gas from the chamber was drawn through the photoacoustic cell of the measuring device via a stainless steel tube. The rat was next placed into the chamber, which was then sealed. It was found that a period of 10 min was sufficient to reach the level of CH4 released by the animal to be measured reliably and reproducibly in an extraction sample. Accordingly, a sample of the chamber gas was analysed exactly 10 min after the animal had been placed in the chamber. The rat was then removed and the measurements were repeated on the subsequent day. The chamber was thoroughly flushed with room air before the next rat was placed in. The whole-body CH4 emission of the animals was calculated as the difference in the baseline CH4 concentration and the 10 min sample and referred to the body surface (F (dm2) = 10*S0.75 kg).

Analysis of mitochondrial function in the rat

After the last gas measurements the animals were anesthetized with 5% chloral hydrate (375 mg/kg), and approx. 50 mg tissue biopsies were subsequently taken to determine the mitochondrial function in the liver and the hippocampus. The tissue samples were immediately placed into 2 ml of PBS-based homogenization buffer containing 0.25 M saccharose, 10 mM Tris, 0.5 mM EDTA and 0.05% BSA. For determination of the respiratory activity of mitochondria high-resolution respirometry (Oxygraph-2k, Oroboros Instruments, Innsbruck, Austria) was used. 50 μl tissue homogenates were incubated with the same buffer in the measuring chamber for 30 sec to record state I respiration. At the end of state I, the steady-state basal oxygen consumption (respiratory flux) was detected. The complex II-linked respiration rate (state II) was determined after addition of complex I inhibitor 0.5 μM rotenone, and after reaching the plateau of flux, and additional administration of 10 mM succinate. After reaching the plateau of flux, 2.5 mM ADP was added for determination of oxidative phosphorlyation capacity of the samples (state III respiration). The oxygen consumption rates were referred to the protein content of the sample.

Liver-specific enzymes

Serum liver-specific enzymes were measured by commercially available diagnostic kits (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) was determined by UV kinetic method using alpha-ketoglutarate and L-aspartate as substrates. Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) was measured by UV kinetic method using alpha-ketoglutarate and L-alanine as substrates. Gamma glutamyl transferase (GGT) was measured by enzymatic colorimetric method using L-gamma-glutamyl-3-carboxy-4-nitroanilide and glycylglycine substrates. Alkaline phosphatase (AP) activity was measured 4-nitrophenyl phosphate as substrate and 2-amino-2-methyl-l-propanol as buffer on a Modular P800 (Roche) chemistry analyzer. IFCC standardized UV kinetic method without pyridoxal phosphate activation were used for AST and ALT, IFCC standardized colorimetric assay was used for the AP measurements.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed with the statistical software package GraphPad Prism 5.01 for Windows (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, California, USA). For time-dependent differences within groups repeated measures one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparison test and for time-dependent differences of multiple groups two-way ANOVA, followed by Bonferroni post-hoc test was applied. Two-tailed paired t-test was used to compare values before and after treatments within groups. One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc test was applied to compare multiple groups. In the figures, mean values and standard error of mean (SEM) are given, p values < 0.05 were considered significant.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Nikolett Beretka, Csilla Mester, Károly Tóth, Ágnes Lilla Szilágyi and Kálmán Vas for their skillful assistance. The study was supported by the Hungarian Scientific Research Fund OTKA K104656, the National Research Development and Innovation Office NKFI K120232 grants and GINOP-2.3.2-15-2016-00015 research grant.

Author Contributions

R.M. performed experiments, data analysis, statistical analysis and prepared figures. E.T., R.M. performed human measurements. R.M., T.T., G.S., E.T., P.H., R.T. A.T.M. performed respirometric analysis. I.F., A.S. performed liver enzyme measurements. A.M., A.S., G.S. provided the P.S. instrument for CH4 measurements. E.T. and T.T. are responsible for the study design. R.M. and E.T. wrote the main manuscript text. M.B. drafted the manuscript. M.B. and E.T. raises the hypothesis that CH4 is an indicator molecule. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

E. Tuboly and R. Molnár contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at doi:10.1038/s41598-017-07637-3

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.de Lacy Costello BP, Ledochowski M, Ratcliffe NM. The importance of methane breath testing: a review. J Breath Res. 2013;7:024001. doi: 10.1088/1752-7155/7/2/024001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nose K, Nunome Y, Kondo T, Araki S, Tsuda T. Identification of gas emanated from human skin: methane, ethylene, and ethane. Anal Sci. 2005;21:625–628. doi: 10.2116/analsci.21.625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Szabo A, et al. Exhaled methane concentration profiles during exercise on an ergometer. J Breath Res. 2015;9:016009. doi: 10.1088/1752-7155/9/1/016009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keppler F, et al. Stable isotope and high precision concentration measurements confirm that all humans produce and exhale methane. J Breath Res. 2016;10:016003. doi: 10.1088/1752-7155/10/1/016003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghyczy M, Boros M. Electrophilic methyl groups present in the diet ameliorate pathological states induced by reductive and oxidative stress: a hypothesis. Br J Nutr. 2001;85:409–414. doi: 10.1079/BJN2000274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ghyczy M, Torday C, Boros M. Simultaneous generation of methane, carbon dioxide, and carbon monoxide from choline and ascorbic acid: a defensive mechanism against reductive stress? FASEB J. 2003;17:1124–1126. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0918fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ghyczy M, et al. Hypoxia-induced generation of methane in mitochondria and eukaryotic cells: an alternative approach to methanogenesis. Cellular Physiology & Biochemistry. 2008;21:251–258. doi: 10.1159/000113766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ghyczy M, et al. Oral phosphatidylcholine pretreatment decreases ischemia-reperfusion-induced methane generation and the inflammatory response in the small intestine. Shock. 2008;30:596–602. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e31816f204a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keppler F, Hamilton JT, Brass M, Rockmann T. Methane emissions from terrestrial plants under aerobic conditions. Nature. 2006;439:187–191. doi: 10.1038/nature04420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Messenger DJ, McLeod AR, Fry SC. The role of ultraviolet radiation, photosensitizers, reactive oxygen species and ester groups in mechanisms of methane formation from pectin. Plant, Cell & Environment. 2009;32:1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2008.01892.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tuboly E, et al. Methane biogenesis during sodium azide-induced chemical hypoxia in rats. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2013;304:C207–214. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00300.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu D, Zhai Q, Shi X. Alcohol-induced oxidative stress and cell responses. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;21(Suppl 3):S26–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04589.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tuboly E, et al. Determination of endogenous methane formation by photoacoustic spectroscopy. J Breath Res. 2013;7:046004. doi: 10.1088/1752-7155/7/4/046004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thurman RG, Ji S, Lemasters JJ. Alcohol-induced liver injury. The role of oxygen. Recent Dev Alcohol. 1984;2:103–117. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4684-4661-6_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cederbaum AI, Lu Y, Wu D. Role of oxidative stress in alcohol-induced liver injury. Arch Toxicol. 2009;83:519–548. doi: 10.1007/s00204-009-0432-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gunzerath L, Hewitt BG, Li TK, Warren KR. Alcohol research: past, present, and future. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2011;1216:1–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05832.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sim MO, et al. Anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects of umbelliferone in chronic alcohol-fed rats. Nutr Res Pract. 2015;9:364–369. doi: 10.4162/nrp.2015.9.4.364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Katyal R, Saroch N, Bharat Bhushan A. Alcohol and periodontal health in adolescence. SRM Journal of Research in Dental Sciences. 2012;3:257–263. doi: 10.4103/0976-433X.114973. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brownawell AM, Carmines EL, Montesano F. Safety assessment of AGPC as a food ingredient. Food Chem Toxicol. 2011;49:1303–1315. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2011.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abbiati G, Fossati T, Lachmann G, Bergamaschi M, Castiglioni C. Absorption, tissue distribution and excretion of radiolabelled compounds in rats after administration of [14C]-L-alpha-glycerylphosphorylcholine. Eur J Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 1993;18:173–180. doi: 10.1007/BF03188793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parnetti L, Amenta F, Gallai V. Choline alphoscerate in cognitive decline and in acute cerebrovascular disease: an analysis of published clinical data. Mech Ageing Dev. 2001;122:2041–2055. doi: 10.1016/S0047-6374(01)00312-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scribner DM, et al. Liver metabolomic changes identify biochemical pathways in hemorrhagic shock. J Surg Res. 2010;164:e131–139. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2010.07.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tokes T, et al. Protective effects of L-alpha-glycerylphosphorylcholine on ischaemia-reperfusion-induced inflammatory reactions. Eur J Nutr. 2015;54:109–118. doi: 10.1007/s00394-014-0691-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hartmann P, et al. L-alpha-glycerylphosphorylcholine reduces the microcirculatory dysfunction and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate-oxidase type 4 induction after partial hepatic ischemia in rats. J Surg Res. 2014;189:32–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2013.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garcia JL, Patel BK, Ollivier B. Taxonomic, phylogenetic, and ecological diversity of methanogenic Archaea. Anaerobe. 2000;6:205–226. doi: 10.1006/anae.2000.0345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wishkerman A, et al. Enhanced formation of methane in plant cell cultures by inhibition of cytochrome c oxidase. Plant Cell Environ. 2011;34:457–464. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2010.02255.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee KN, et al. Association between symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome and methane and hydrogen on lactulose breath test. J Korean Med Sci. 2013;28:901–907. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2013.28.6.901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Strocchi A, Furne J, Ellis C, Levitt MD. Methanogens outcompete sulphate reducing bacteria for H2 in the human colon. Gut. 1994;35:1098–1101. doi: 10.1136/gut.35.8.1098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schmidt O, Hink L, Horn MA, Drake HL. Peat: home to novel syntrophic species that feed acetate- and hydrogen-scavenging methanogens. ISME J. 2016;10:1954–1966. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2015.256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mutlu EA, et al. Colonic microbiome is altered in alcoholism. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2012;302:G966–978. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00380.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Engen PA, Green SJ, Voigt RM, Forsyth CB, Keshavarzian A. The Gastrointestinal Microbiome: Alcohol Effects on the Composition of Intestinal Microbiota. Alcohol Res. 2015;37:223–236. doi: 10.35946/arcr.v37.2.07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yu Y, Pawliszyn J. On-line monitoring of breath by membrane extraction with sorbent interface coupled with CO2 sensor. J Chromatogr A. 2004;1056:35–41. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9673(04)01828-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Triantafyllou K, Chang C, Pimentel M. Methanogens, Methane and Gastrointestinal Motility. Journal of Neurogastroenterology & Motility. 2014;20:31–40. doi: 10.5056/jnm.2014.20.1.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bustamante J, Karadayian AG, Lores-Arnaiz S, Cutrera RA. Alterations of motor performance and brain cortex mitochondrial function during ethanol hangover. Alcohol. 2012;46:473–479. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2011.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.King AL, et al. The methyl donor S-adenosylmethionine prevents liver hypoxia and dysregulation of mitochondrial bioenergetic function in a rat model of alcohol-induced fatty liver disease. Redox Biol. 2016;9:188–197. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2016.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Strifler G, et al. Targeting Mitochondrial Dysfunction with L-Alpha Glycerylphosphorylcholine. PLoS One. 2016;18:e0166682. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0166682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee SH, et al. Late treatment with choline alfoscerate (l-alpha glycerylphosphorylcholine, α-GPC) increases hippocampal neurogenesis and provides protection against seizure-induced neuronal death and cognitive impairment. Brain Research. 2017;1654:66–76. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2016.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kunz WS. Different metabolic properties of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation in different cell types–important implications for mitochondrial cytopathies. Exp Physiol. 2003;88:149–54. doi: 10.1113/eph8802512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fernández-Vizarra E, Enríquez JA, Pérez-Martos A, Montoya J, Fernández-Silva P. Tissue-specific differences in mitochondrial activity and biogenesis. Mitochondrion. 2011;11:207–13. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2010.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lu Y, Gong P, Cederbaum AI. Pyrazole induced oxidative liver injury independent of CYP2E1/2A5 induction due to Nrf2 deficiency. Toxicology. 2008;30:9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2008.07.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Houtkooper RH, Canto C, Wanders RJ, Auwerx J. The secret life of NAD + : an old metabolite controlling new metabolic signaling pathways. Endocr Rev. 2010;31:194–223. doi: 10.1210/er.2009-0026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Watson WH, et al. Ethanol exposure modulates hepatic S-adenosylmethionine and S-adenosylhomocysteine levels in the isolated perfused rat liver through changes in the redox state of the NADH/NAD(+) system. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1812:613–618. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2011.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Villanueva JA, Halsted CH. Hepatic transmethylation reactions in micropigs with alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology. 2004;39:1303–1310. doi: 10.1002/hep.20168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Levine RL, Mosoni L, Berlett BS, Stadtman ER. Methionine residues as endogenous antioxidants in proteins. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1996;93:15036–15040. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.26.15036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lenhart K, et al. Evidence for methane production by saprotrophic fungi. Nat Commun. 2012;3:1046. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Althoff F, Jugold A, Keppler F. Methane formation by oxidation of ascorbic acid using iron minerals and hydrogen peroxide. Chemosphere. 2010;80:286–292. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Althoff F, et al. Abiotic methanogenesis from organosulphur compounds under ambient conditions. Nature Communications. 2014;5:4205. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bauernschmitt HG, Kinne RK. Metabolism of the ‘organic osmolyte’ glycerophosphorylcholine in isolated rat inner medullary collecting duct cells. I. Pathways for synthesis and degradation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1993;1148:331–341. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(93)90147-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Onishchenko LS, Gaikova ON, Yanishevskii SN. Changes at the focus of experimental ischemic stroke treated with neuroprotective agents. Neurosci Behav Physiol. 2008;38:49–54. doi: 10.1007/s11055-008-0007-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gibellini F, Smith TK. The Kennedy pathway–De novo synthesis of phosphatidylethanolamine and phosphatidylcholine. IUBMB Life. 2010;62:414. doi: 10.1002/iub.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hensley K, et al. Dietary choline restriction causes complex I dysfunction and increased H(2)O(2) generation in liver mitochondria. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:983–989. doi: 10.1093/carcin/21.5.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dawson RM. Studies on the phosphorylcholine diesterase. Biochem J. 1956;62:693–6. doi: 10.1042/bj0620693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.