Abstract

Bacterial separation from human blood samples can help with the identification of pathogenic bacteria for sepsis diagnosis. In this work, we report an acoustofluidic device for label-free bacterial separation from human blood samples. In particular, we exploit the acoustic radiation force generated from a tilted-angle standing surface acoustic wave (taSSAW) field to separate E. coli from human blood cells based on their size difference. Flow cytometry analysis of the E. coli separated from red blood cells (RBCs) shows a purity of more than 96%. Moreover, the label-free electrochemical detection of the separated E. coli displays reduced non-specific signals due to the removal of blood cells. Our acoustofluidic bacterial separation platform has advantages such as label-free separation, high biocompatibility, flexibility, low cost, miniaturization, automation, and ease of in-line integration. The platform can be incorporated with an on-chip sensor to realize a point-of-care (POC) sepsis diagnostic device.

Keywords: Acoustofluidics, standing surface acoustic wave (SSAW), bacterial separation

1. Introduction

The presence of pathogenic bacteria in the bloodstream is a vital concern to public health and causes sepsis in severe cases, which affects up to 19 million people worldwide and over 750,000 people in the United States annually with a mortality rate of 20–30%.[1,2] Rapid and reliable detection of bacteria from human blood samples can promote the early diagnosis and successful treatment of sepsis.[3] Conventional detection methods rely on bacterial blood cultures and are time-consuming and labor-intensive, thereby causing delay in sepsis diagnosis. To solve this issue, researchers have developed different culture-independent methods that can rapidly detect bacteria from human blood samples.[4–10] Although these direct detection systems can accelerate the identification of pathogenic bacteria, the presence of blood components (e.g., blood cells) can potentially increase the background noise and confound the detection results through non-specific interactions. The separation of bacteria from blood samples prior to detection offers an excellent solution to overcome this challenge.

One possible approach for bacterial separation from blood samples is through centrifugation.[11,12] However, the manual fluid handling in centrifugation hinders its integration with bacterial detection systems to realize an automated POC sepsis diagnostic device. With its high performance in cell manipulation, microfluidics has recently emerged as a powerful platform for cell separation.[13–16] Thus far, different microfluidic platforms have been developed for bacterial separation using affinity capture,[17] hydrodynamic force,[18] inertial force,[19,20] magnetic force,[21–26] dielectrophoretic force,[27,28] or acoustic force.[29–32] Among these bacterial separation technologies, acoustic approaches have some attractive features that make them suitable for separating pathogenic bacteria prior to detection. Acoustic methods can separate bacteria from blood samples in a label-free manner, which simplifies the procedure of sample preparation. In addition, the non-invasive nature of acoustic forces helps preserve the viability and proliferation of cells.[33] This high biocompatibility is beneficial for further culture of the separated bacteria. Moreover, acoustic approaches can be conveniently integrated with different detection systems to enable all-in-one, micro total analysis system (μTAS).[34–37]

In this work, we demonstrate a microfluidic device that can separate Escherichia coli bacteria (E. coli) from human blood samples using acoustic force. This bacterial separation device is built upon our acoustofluidic (i.e., the fusion of acoustics and microfluidics) based cell manipulation platform.[38–41] It features a tilted configuration between a microchannel and interdigital transducers (IDTs) to realize high-efficiency separation of E. coli from human blood samples in a tilted-angle standing surface acoustic wave (taSSAW) field.[38–40] The separation of E. coli reduces the non-specific signals generated from blood cells during the electrochemical detection of E. coli. With the advantages of label-free separation, high biocompatibility, flexibility to operate in different buffers, as well as low cost, miniaturization, automation, and ease of in-line integration, our acoustofluidic bacterial separation platform can be incorporated with an electrochemical sensor to realize a fully integrated, point-of-care (POC) device for sepsis diagnosis.[42,43]

2. Working Mechanism

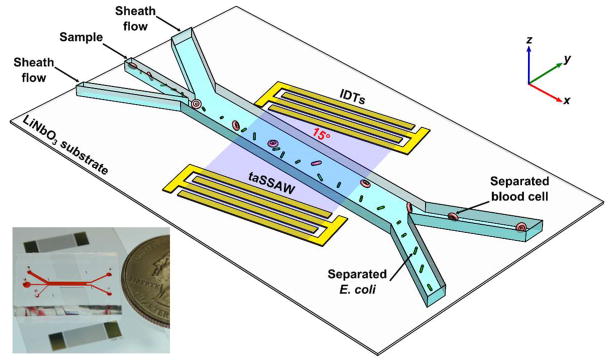

Fig. 1 illustrates the working mechanism of separating E. coli from human blood cells. Our acoustofluidic device (Fig. 1 inset) is made by bonding a polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) microchannel in between a pair of IDTs with a tilted angle of 15° on a lithium niobate (LiNbO3) piezoelectric substrate. When we excite the IDTs with radio frequency (RF) signals, two series of identical surface acoustic waves (SAWs) propagating in opposite directions are generated. Constructive interference between them forms a standing surface acoustic wave (SSAW) field. As a result, periodically distributed pressure nodes and antinodes are formed inside the microchannel with an angle of inclination to the fluid flow direction. When a human blood sample containing E. coli flows into the SSAW field, cells present in the sample are subject to a primary acoustic radiation force and drag force. The primary acoustic radiation force (Fr) and drag force (Fd) acting on any particle in the SSAW field can be expressed as[44]

Figure 1.

Schematic of our acoustofluidic separation of E. coli from human blood samples using the taSSAW technique. Inset: a photograph of our acoustofluidic device.

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

where p0, λ, Vp, k, x, ρp, ρm, βp, βm, η, Rp, and ur, are, respectively, acoustic pressure, SAW wavelength, volume of the particle, wave vector, distance from a pressure node, density of the particle, density of the medium, compressibility of the particle, compressibility of the medium, viscosity of the medium, radius of the particle, and relative velocity of the particle. Eq (2) calculates the acoustic contrast factor, ϕ, which determines whether the particle is directed to pressure nodes or antinodes in the SSAW field.

Human blood cells and E. coli pass multiple regions of paired pressure node and antinode when flowing through the taSSAW field. Because of their positive acoustic contrast factors, human blood cells and E. coli are directed towards the pressure node in each region and deviate from the flow direction repeatedly resulting in a lateral displacement. Eq (1) denotes that the amplitude of the primary acoustic radiation force is dependent on the cells’ physical properties (i.e., size, density, compressibility). Since human blood cells (e.g., white blood cells and red blood cells) are larger than E. coli, they are subject to stronger primary acoustic radiation force and are pushed to the upper outlet with larger lateral displacement. At the same time, E. coli are subject to a weak primary acoustic radiation force and remain in the lower outlet. This enables the size-dependent separation of E. coli from human blood cells.

3. Materials and Methods

Device fabrication

Fig. 1 inset is a photograph of our acoustofluidic device for the taSSAW-based E. coli separation. For the fabrication of IDTs, a double layer of chrome and gold (Cr/Au, 50 Å/500 Å) was first deposited on a photoresist-patterned LiNbO3 wafer (128° Y-cut, 500 μm thick, double-side polished) using an e-beam evaporator (RC0021, Semicore, USA). The pair of IDTs (period: ~200 μm) was then exposed by a lift-off procedure. A single-layer PDMS microchannel (1 mm wide and 75 μm high) with three inlets and two outlets was fabricated by standard soft-lithography using SU-8 photoresist. After drilling holes for inlets and outlets using a 0.75 mm punch (Prod# 15071, Harris Uni-Core™, Ted Pella, USA), we treated the IDTs and PDMS microchannel with oxygen plasma in a plasma cleaner (PDC001, Harrick Plasma, USA) for 3 minutes. After plasma treatment, we bonded the PDMS microchannel with IDTs (tilt angle ~ 15°) and cured the whole device at 65°C overnight before use.

Sample preparation

For size-dependent separation of microparticles, 4.95 μm green fluorescent microparticles (Cat# FC05F, Bangs Laboratory, USA) and 0.97 μm red fluorescent microparticles (Cat# FC03F, Bangs Laboratory, USA) were mixed in 500 μl of deionized (DI) water supplemented with 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS). The final concentrations of both microparticles were 107/ml. Human red blood cells (RBCs) and whole blood were purchased (Zen-Bio, USA). Green fluorescent protein (GFP)-expressing E. coli (BW25113/pCM18) was cultured in a sterilized nutrient broth medium (Prod# 233000, Becton Dickinson, USA) supplemented with 100 μg/ml of erythromycin (Cat# E5389, Sigma-Aldrich, USA) until OD600 = 1.1 (~ 8.8 × 108 cells/ml). For separation of E. coli from RBCs, 30 μl of E. coli and 6 μl of RBCs were mixed in 564 μl of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (Cat# 10010, Life Technologies, USA) supplemented with 0.5% Pluronic F-68 (Cat# P1300, Sigma-Aldrich, USA). The final concentrations of E. coli and RBCs in the mixture sample were approximately 4.4 × 107 and 1.32 × 108 cells/ml, respectively. For separation of E. coli from blood cells, 68 μl of E. coli and 12 μl of whole blood were mixed in 520 μl of PBS supplemented with 0.5% Pluronic F-68. Approximately, the final concentrations of both E. coli and blood cells in the mixture sample were 108 cells/ml.

Experimental setup

Separation experiments were conducted on the stage of an inverted microscope (Eclipse Ti-U, Nikon, Japan). The IDTs were excited by amplified RF signals using a function generator (E4422B, Agilent, USA) and a power amplifier (100A250A, Amplifier Research, USA). The mixture sample and sheath flow buffers were injected into the center inlet and two side inlets with flow rates controlled by syringe pumps (neMESYS, cetoni GmbH, Germany). DI water (0.1% SDS) and PBS (0.5% Pluronic F-68) were used as sheath flow buffers for separation of microparticles and cells, respectively. The flow rates of the upper and lower sheath flows were 9 and 7 μl/min, respectively, while the flow rate of sample flow was 0.5 (for separations of microparticles and E. coli from RBCs) or 1 (for separation of E. coli from blood cells) μl/min. Separated samples were collected in 1.7-ml microcentrifuge tubes (Cat# C2170, Denville Scientific, USA) from two outlets. A fast camera (SA4, Photron, Japan) and a charge-coupled device (CCD) camera (CoolSNAP HQ2, Photometrics, USA) were connected to the microscope for video acquisition.

Flow cytometry

For the characterization of E. coli separation from RBCs, the mixture sample, separated E. coli sample, and separated RBCs sample were examined using a commercial flow cytometer (FC500, Beckman Coulter, USA). Pure samples were also examined to set the gates for E. coli and RBCs. Flow cytometry results were analyzed using commercial software (FlowJo, FlowJo, LLC, USA).

E. coli detection

After separation of E. coli from human blood cells, three samples were collected: (a) 60 μl of the mixture sample without separation; (b) 510 μl of separated E. coli collected from the lower outlet; and (c) 510 μl of separated blood cells collected from the upper outlet. Collected samples were shipped to Zeng Lab on dry ice. Upon arrival, these three samples were diluted with 10 mM HEPES buffer to final volumes of 1 ml. For E. coli detection, these three samples were first diluted 200× to 6000× in 10 mM HEPES buffer. 1 ml of Concanavalin A (Con A) solution and diluted sample were added into the fixed electrochemical cell. After incubation at 25°C for 60 minutes, the electrochemical cell was rinsed thoroughly with incubation buffer to remove adsorbed Con A or E. coli. After rinsing, 1 ml of 10 mM HEPES buffer was added into the electrochemical cell, and square wave voltammetry (SWV) was measured under ambient temperature (~ 25°C). The biosensor fabrication and electrochemical detection of E. coli can be found in previous publications by Zeng Lab.[42,43]

4. Results and Discussion

Size-dependent separation of microparticles

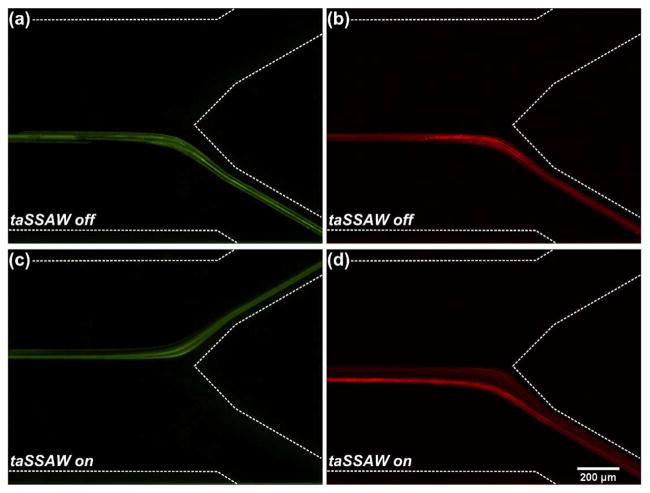

RBCs, the most common cell type in human blood, are typically disc-shaped with a diameter of 6.2–8.2 μm. The average volume of RBCs is 90 μm3, equivalent to a sphere with a diameter of 5.56 μm.[45] E. coli are typically rod-shaped with a length of 2 μm and a diameter of 0.25–1.0 μm. The average volume of E. coli is 0.7 μm3, equivalent to a sphere with a diameter of 1.1 μm.[46] Prior to separating E. coli from blood cells, we performed experimental verification of size-dependent separation using microparticles. In this experiment, we mixed 4.95 and 0.97 μm polystyrene microparticles with a 1:1 ratio and injected into the center inlet of our acoustofluidic device. Sheath flows were injected into two side inlets to focus the microparticles. The flow rate of the upper inlet was set greater than the lower inlet so that when the taSSAW was not applied, both the 4.95 and 0.97 μm microparticles exited the microchannel through the lower outlet (Fig. 2a–b). In order to separate the microparticles, we applied RF signals (19.54 MHz, 24.2 Vpp) to the IDTs to excite a taSSAW field. When the microparticles flowed into the taSSAW field, they deviated from the original flow stream under the influence of primary acoustic radiation force and drag force. These two types of polystyrene microparticles have the same density and compressibility, thus the same acoustic contrast factor. Eq (1) shows that the primary acoustic radiation force acting on the microparticle is dependent on the volume of the microparticle. Because of the size difference, the 4.95 μm microparticles experienced much greater primary acoustic radiation force than the 0.97 μm microparticles. Therefore, the lateral displacement of the 4.95 μm microparticles was much greater than for the 0.97 μm microparticles. When leaving the taSSAW field, the 4.95 μm microparticles were directed to the upper outlet, whereas the 0.97 μm microparticles remained in the lower outlet because of the insufficient lateral displacement (Fig. 2c–d). As a result, size-dependent separation of microparticles was achieved when the taSSAW was applied.

Figure 2.

Stacked fluorescence images showing the separation of 4.95 μm (green) and 0.97 μm (red) polystyrene microparticles: (a–b) When the taSSAW was off, both the 4.95 and 0.97 μm microparticles exited the microchannel through the lower outlet; (c–d) When the taSSAW was on, the 4.95 μm microparticles were forced to the upper outlet while the 0.97 μm microparticles remained in the lower outlet, resulting in size-dependent acoustic separation of the two types of microparticles.

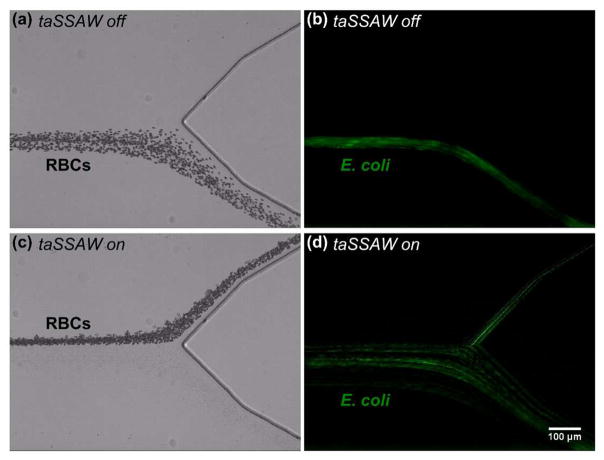

Separation of E. coli from RBCs

Since RBCs comprise the majority of cells in human blood, we tested the separation of E. coli from RBCs. In this experiment, we mixed GFP-expressing E. coli and RBCs with a 1:3 ratio and performed separation using our acoustofluidic device. When the taSSAW was not applied, RBCs exited the microchannel through the lower outlet (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Video S1). Since it is difficult to observe E. coli under bright-field images due to their small size, we captured fluorescence images to show the trajectories of E. coli. When the taSSAW was not applied, E. coli also exited the microchannel through the lower outlet mixed with RBCs (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Video S2). To separate E. coli from RBCs, we excited a taSSAW field with RF signals (19.54 MHz, 24.2 Vpp). Most of the RBCs were pushed to the upper outlet when the taSSAW was applied (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Video S3). In comparison, most of the E. coli remained in the lower outlet due to their small size and weak primary acoustic radiation force even when the taSSAW was applied (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Video S4). The experimental result illustrates that effective separation of E. coli from RBCs can be realized using our taSSAW-based acoustofluidic device.

Figure 3.

Stacked micrographs showing the acoustofluidic separation of E. coli from RBCs. (a, c) Bright-field and (b, d) fluorescence images represent RBCs and E. coli, respectively. (a–b) When the taSSAW was not applied, RBCs and E. coli were collected together from the lower outlet in a mixture. (c–d) When the taSSAW was applied, RBCs were pushed to the upper outlet while E. coli were collected from the lower outlet.

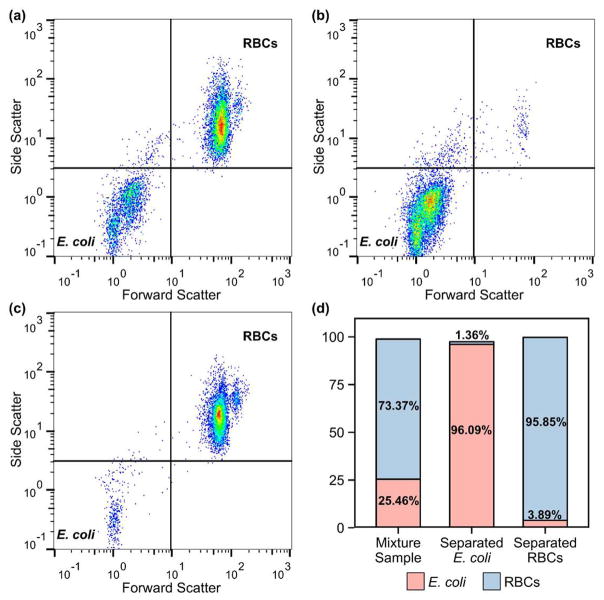

To characterize the separation results, we collected the mixture sample, separated E. coli sample from the lower outlet, and separated RBCs sample from the upper outlet and analyzed using a flow cytometer. Pure samples were also examined to set the gates for E. coli and RBCs. Because of their large difference in size, a 2D plot of side scatter vs. forward scatter clearly distinguished E. coli from RBCs. Fig. 4a is the flow cytometry result of the mixture sample, which consisted of 25.46% E. coli and 73.37% RBCs (Fig. 4d). After the taSSAW-based acoustofluidic separation, we extracted E. coli from the mixture sample through the lower outlet (Fig. 4b). The purity of the separated E. coli sample was 96.09% (Fig. 4d). In comparison, the sample collected through the upper outlet mainly consisted of RBCs (Fig. 4c), with a purity of 95.85% (Fig. 4d). This flow cytometry result verifies that our acoustofluidic platform can successfully separate E. coli from RBCs based on their size difference with more than 96% purity.

Figure 4.

Flow cytometry results of (a) the mixture sample (RBCs mixed with E. coli), (b) separated E. coli sample collected through the lower outlet, and (c) separated RBCs sample collected through the upper outlet. (d) Percentages of E. coli and RBCs in three samples.

Separation and detection of E. coli from human blood samples

After demonstrating the separation of E. coli from RBCs, we investigated the separation and detection of E. coli from human blood samples. In this experiment, E. coli and human whole blood were mixed in PBS and injected into our acoustofluidic device for taSSAW-based separation. Since the separation of E. coli from blood cells was mainly based on size differences, some platelets with size close to E. coli could have still remained with E. coli after separation. But the removal of RBCs and white blood cells (WBCs) should still be beneficial for downstream E. coli detection. After separation, we collected three samples (the mixture sample, separated E. coli, and separated blood cells) and conducted electrochemical detection of E. coli.

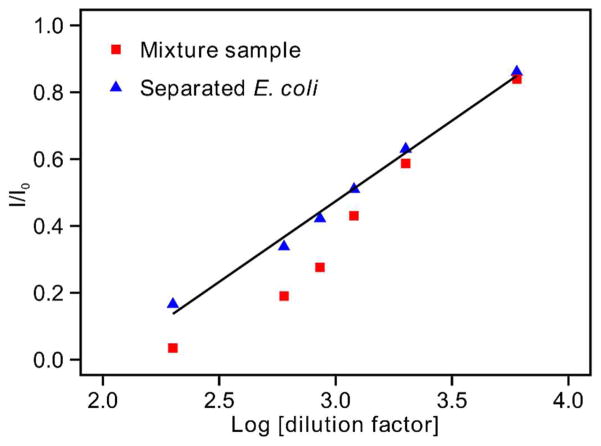

The samples were analyzed using our established label-free carbohydrate-lectin sensor.[43] We used a carbohydrate (i.e., mannose) conjugated conductive polymer (polythiophene containing fused quinone moieties) as the sensing interface to fabricate our lectin (Con A) sensor. We used this sensor to detect gram-negative bacteria utilizing specific lectin (Con A) mediated lipopolysaccharides (LPS)-mannose binding. The conductive polymer allows the monitoring of the binding events by label-free electrochemical readout with high specificity, high selectivity, and a widened logarithmic range of detection. As expected, separated blood cells generated negligible signal change, indicating that there were few E. coli in the sample that could specifically bind to the detection electrode (data not shown). The mixture sample and separated E. coli both generated obvious signal changes, confirming the presence of E. coli in the samples. In order to further evaluate the effect of E. coli separation on detection, we diluted the mixture sample and separated E. coli, detected the diluted samples using square wave voltammetry (SWV), and plotted the electrochemical detection signals (I/I0) against the logarithm of dilution factors (Log [dilution factor]) (Fig. 5). As discussed in our previous work, the electrochemical detection of E. coli is a signal OFF approach, which means that increased binding of E. coli to the sensing electrode will lead to decreased signal (I/I0).[43] Both the mixture sample and separated E. coli demonstrated increased signals at higher dilutions, indicating decreased E. coli binding to the detection electrode. We noticed that the data points from separated E. coli (Fig. 5, blue triangles) followed a good linear regression model, with a regression coefficient of 0.4823. This regression coefficient was similar to the 0.4196 reported in our previous work detecting pure E. coli in HEPES buffer.[43] In comparison, the data points from the mixture sample (Fig. 5, red squares) showed a non-linear relationship, indicating non-specific binding of blood cells to the detection electrode. Such non-specific binding was expected to be more obvious at lower dilutions (higher blood cell concentrations), resulting in a non-linear shift of the electrochemical detection curve at lower dilutions. The electrochemical detection result shown here indicates that the acoustofluidic separation of E. coli from the mixture sample benefits the downstream electrochemical detection of E. coli by reducing non-specific signals generated from blood cells. It is worth noting that the concentration of E. coli spiked into the human blood samples during this proof-of-concept test was relatively high compared to clinical blood samples of early-stage septic patients (1–100 colony-forming unit (CFU)/ml).[47] The limit of detection of our electrochemical sensor is 25 cell/ml.[43] In order to separate 25 E. coli cells from 1 ml of clinical blood sample in 1 h for electrochemical detection, the sample flow rate of our acoustofluidic bacterial separation platform needs to be increased to 4.17–417 μl/ml for future performance improvements.

Figure 5.

Electrochemical detection of E. coli from the mixture sample and separated E. coli sample using square wave voltammetry (SWV).

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, we have demonstrated an acoustofluidic device that can separate E. coli from human blood samples using the taSSAW technique. Our device takes advantage of the size difference between E. coli and blood cells and can separate E. coli from RBCs with more than 96% purity. In addition, the acoustofluidic separation of E. coli from human blood samples can decrease the non-specific signals generated from blood cells during the downstream electrochemical detection of E. coli. This result suggests the benefit of an integrated device that couples a separation unit and a detection unit to realize more sensitive, specific detection of pathogens from biofluids. The acoustofluidic bacterial separation platform demonstrated here is an excellent candidate for fulfilling this unmet need and leading to the development of a POC sepsis diagnostic device.[48–52]

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Arul Jayaraman for kindly providing us the GFP-expressing E.coli strain (BW25113/pCM18). This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01AI120560, R01HD086325, and R33EB019785) and the National Science Foundation (IDBR-1455658). S.L. and C.E.C. were funded in part by grant AI45818 from NIAID, NIH. Components of this work were conducted at the Penn State node of the NSF-funded National Nanotechnology Infrastructure Network (NNIN).

References

- 1.Cohen J. The immunopathogenesis of sepsis. Nature. 2002;420:885–91. doi: 10.1038/nature01326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Angus DC, van der Poll T. Severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:840–51. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1208623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reinhart K, Bauer M, Riedemann NC, Hartog CS. New Approaches to Sepsis: Molecular Diagnostics and Biomarkers. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2012;25:609–34. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00016-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chaney R, Rider J, Pamphilon D. Direct detection of bacteria in cellular blood products using bacterial ribosomal RNA-directed probes coupled to electrochemiluminescence. Transfus Med. 1999;9:177–88. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3148.1999.00196.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gao J, Li L, Ho P-L, Mak GC, Gu H, Xu B. Combining Fluorescent Probes and Biofunctional Magnetic Nanoparticles for Rapid Detection of Bacteria in Human Blood. Adv Mater. 2006;18:3145–8. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kang D-K, Ali MM, Zhang K, Huang SS, Peterson E, Digman MA, Gratton E, Zhao W. Rapid detection of single bacteria in unprocessed blood using Integrated Comprehensive Droplet Digital Detection. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5427. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rider J, Newton A. Electrochemiluminescent detection of bacteria in blood components. Transfus Med. 2002;12:115–23. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3148.2002.00364.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Störmer M, Kleesiek K, Dreier J. High-volume extraction of nucleic acids by magnetic bead technology for ultrasensitive detection of bacteria in blood components. Clin Chem. 2007;53:104–10. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2006.070987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yu H, Ahmed H, Vasta GR. Development of a magnetic microplate chemifluorimmunoassay for rapid detection of bacteria and toxin in blood. Anal Biochem. 1998;261:1–7. doi: 10.1006/abio.1998.2614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lim SH, Mix S, Xu Z, Taba B, Budvytiene I, Berliner AN, Queralto N, Churi YS, Huang RS, Eiden M, Martino RA, Rhodes P, Banaei N. Colorimetric Sensor Array Allows Fast Detection and Simultaneous Identification of Sepsis-Causing Bacteria in Spiked Blood Culture. J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52:592–8. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02377-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zelada-Guillén GA, Bhosale SV, Riu J, Rius FX. Real-time potentiometric detection of bacteria in complex samples. Anal Chem. 2010;82:9254–60. doi: 10.1021/ac101739b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tlili C, Sokullu E, Safavieh M, Tolba M, Ahmed MU, Zourob M. Bacteria Screening, Viability, And Confirmation Assays Using Bacteriophage-Impedimetric/Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification Dual-Response Biosensors. Anal Chem. 2013;85:4893–901. doi: 10.1021/ac302699x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lillehoj PB, Tsutsui H, Valamehr B, Wu H, Ho C-M. Continuous sorting of heterogeneous-sized embryoid bodies. Lab Chip. 2010;10:1678. doi: 10.1039/c000163e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gossett DR, Weaver WM, Mach AJ, Hur SC, Tse HTK, Lee W, Amini H, Di Carlo D. Label-free cell separation and sorting in microfluidic systems. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2010;397:3249–67. doi: 10.1007/s00216-010-3721-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lenshof A, Laurell T. Continuous separation of cells and particles in microfluidic systems. Chem Soc Rev. 2010;39:1203–17. doi: 10.1039/b915999c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu L, Lee H, Brasil Pinheiro MV, Schneider P, Jetta D, Oh KW. Phaseguide-assisted blood separation microfluidic device for point-of-care applications. Biomicrofluidics. 2015;9:14106. doi: 10.1063/1.4906458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schirhagl R, Hall EW, Fuereder I, Zare RN. Separation of bacteria with imprinted polymeric films. Analyst. 2012;137:1495. doi: 10.1039/c2an15927a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ishikawa T, Shioiri T, Numayama-Tsuruta K, Ueno H, Imai Y, Yamaguchi T. Separation of motile bacteria using drift velocity in a microchannel. Lab Chip. 2014;14:1023–32. doi: 10.1039/c3lc51302e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu Z, Willing B, Bjerketorp J, Jansson JK, Hjort K. Soft inertial microfluidics for high throughput separation of bacteria from human blood cells. Lab Chip. 2009;9:1193–9. doi: 10.1039/b817611f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee W, Kwon D, Choi W, Jung GY, Jeon S. 3D-Printed Microfluidic Device for the Detection of Pathogenic Bacteria Using Size-based Separation in Helical Channel with Trapezoid Cross-Section. Sci Rep. 2015;5:7717. doi: 10.1038/srep07717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qiu J, Zhou Y, Chen H, Lin J-M. Immunomagnetic separation and rapid detection of bacteria using bioluminescence and microfluidics. Talanta. 2009;79:787–95. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fugier E, Dumont A, Malleron A, Poquet E, Mas Pons J, Baron A, Vauzeilles B, Dukan S. Rapid and Specific Enrichment of Culturable Gram Negative Bacteria Using Non-Lethal Copper-Free Click Chemistry Coupled with Magnetic Beads Separation ed D Rittschof. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0127700. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0127700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xia N, Hunt TP, Mayers BT, Alsberg E, Whitesides GM, Westervelt RM, Ingber DE. Combined microfluidic-micromagnetic separation of living cells in continuous flow. Biomed Microdevices. 2006;8:299–308. doi: 10.1007/s10544-006-0033-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kang JH, Super M, Yung CW, Cooper RM, Domansky K, Graveline AR, Mammoto T, Berthet JB, Tobin H, Cartwright MJ, Watters AL, Rottman M, Waterhouse A, Mammoto A, Gamini N, Rodas MJ, Kole A, Jiang A, Valentin TM, Diaz A, Takahashi K, Ingber DE. An extracorporeal blood-cleansing device for sepsis therapy. Nat Med. 2014;20:1211–6. doi: 10.1038/nm.3640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee J-J, Jeong KJ, Hashimoto M, Kwon AH, Rwei A, Shankarappa SA, Tsui JH, Kohane DS. Synthetic Ligand-Coated Magnetic Nanoparticles for Microfluidic Bacterial Separation from Blood. Nano Lett. 2014;14:1–5. doi: 10.1021/nl3047305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ngamsom B, Esfahani MMN, Phurimsak C, Lopez-Martinez MJ, Raymond J-C, Broyer P, Patel P, Pamme N. Multiplex sorting of foodborne pathogens by on-chip free-flow magnetophoresis. Anal Chim Acta. 2016;918:69–76. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2016.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cai D, Xiao M, Xu P, Xu Y, Du W. An Integrated Microfluidic Device Utilizing Dielectrophoresis and Multiplex Array PCR for Point-of-Care Detection of Pathogens. Lab Chip. 2014;14:3917–24. doi: 10.1039/c4lc00669k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khoshmanesh K, Baratchi S, Tovar-Lopez FJ, Nahavandi S, Wlodkowic D, Mitchell A, Kalantar-zadeh K. On-chip separation of Lactobacillus bacteria from yeasts using dielectrophoresis. Microfluid Nanofluidics. 2012;12:597–606. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ai Y, Sanders CK, Marrone BL. Separation of Escherichia coli Bacteria from Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells Using Standing Surface Acoustic Waves. Anal Chem. 2013;85:9126–34. doi: 10.1021/ac4017715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ohlsson PD, Petersson K, Augustsson P, Laurell T. Acoustophoresis Separation of Bacteria From Blood Cells for Rapid Sepsis Diagnostics. 17th International Conference on Miniaturized Systems for Chemistry and Life Sciences; 2013. pp. 1320–2. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ohlsson P, Petersson K, Laurell T. Acoustic Separation of Bacteria From Blood Cells at High Cell Concentrations Enabled by Acoustic Impedance Matched Buffers. 18th International Conference on Miniaturized Systems for Chemistry and Life Sciences; 2014. pp. 388–90. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ngamsom B, Lopez-Martinez MJ, Raymond J-C, Broyer P, Patel P, Pamme N. On-chip acoustophoretic isolation of microflora including S. typhimurium from raw chicken, beef and blood samples. J Microbiol Methods. 2016;123:79–86. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2016.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ding X, Lin S-CS, Kiraly B, Yue H, Li S, Chiang I-K, Shi J, Benkovic SJ, Huang TJ. On-chip manipulation of single microparticles, cells, and organisms using surface acoustic waves. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2012;109:11105–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1209288109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu Y, Cheng D, Lin I-H, Abbott NL, Jiang H. Microfluidic sensing devices employing in situ-formed liquid crystal thin film for detection of biochemical interactions. Lab Chip. 2012;12:3746–53. doi: 10.1039/c2lc40462a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu H, Huang Y, Jiang H. Artificial eye for scotopic vision with bioinspired all-optical photosensitivity enhancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2016;113:3982–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1517953113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu F, KCP, Zhang G, Zhe J. Microfluidic Magnetic Bead Assay for Cell Detection. Anal Chem. 2016;88:711–7. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b02716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Choi N, Lee K, Lim DW, Lee EK, Chang S-I, Oh KW, Choo J. Simultaneous detection of duplex DNA oligonucleotides using a SERS-based micro-network gradient chip. Lab Chip. 2012;12:5160–7. doi: 10.1039/c2lc40890b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li P, Mao Z, Peng Z, Zhou L, Chen Y, Huang P, Truica CI, Drabick JJ, El-Deiry WS, Dao M, Suresh S, Huang TJ. Acoustic separation of circulating tumor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:4970–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1504484112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li S, Ding X, Mao Z, Chen Y, Nama N, Guo F, Li P, Wang L, Cameron CE, Huang TJ. Standing surface acoustic wave (SSAW)-based cell washing. Lab Chip. 2015;15:331–8. doi: 10.1039/c4lc00903g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ding X, Peng Z, Lin S-CS, Geri M, Li S, Li P, Chen Y, Dao M, Suresh S, Huang TJ. Cell separation using tilted-angle standing surface acoustic waves. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:12992–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1413325111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guldiken R, Jo MC, Gallant ND, Demirci U, Zhe J. Sheathless Size-Based Acoustic Particle Separation. Sensors. 2012;12:905–22. doi: 10.3390/s120100905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang Z, Sun C, Vegesna G, Liu H, Liu Y, Li J, Zeng X. Glycosylated aniline polymer sensor: Amine to imine conversion on protein–carbohydrate binding. Biosens Bioelectron. 2013;46:183–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2013.02.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ma F, Rehman A, Liu H, Zhang J, Zhu S, Zeng X. Glycosylation of Quinone-Fused Polythiophene for Reagentless and Label-Free Detection of E. coli. Anal Chem. 2015;87:1560–8. doi: 10.1021/ac502712q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yosioka K, Kawasima Y. Acoustic radiation pressure on a compressible sphere. Acustica. 1955;5:167–73. [Google Scholar]

- 45.McLaren CE, Brittenham GM, Hasselblad V. Statistical and graphical evaluation of erythrocyte volume distributions. Am J Physiol. 1987;252:H857–66. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1987.252.4.H857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kubitschek HE. Cell Volume Increase in Escherichia coli after shiters to richer media. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:94–101. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.1.94-101.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yagupsky P, Nolte FS. Quantitative aspects of septicemia. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1990;3:269–79. doi: 10.1128/cmr.3.3.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lillehoj PB, Huang M-C, Truong N, Ho C-M. Rapid electrochemical detection on a mobile phone. Lab Chip. 2013;13:2950–5. doi: 10.1039/c3lc50306b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gong MM, MacDonald BD, Nguyen TV, Van Nguyen K, Sinton D. Lab-in-a-pen: a diagnostics format familiar to patients for low-resource settings. Lab Chip. 2014;14:957–63. doi: 10.1039/c3lc51185e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gong MM, Nosrati R, San Gabriel MC, Zini A, Sinton D. Direct DNA Analysis with Paper-Based Ion Concentration Polarization. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:13913–9. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b08523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mitra B, Wilson CG, Que L, Selvaganapathy P, Gianchandani YB. Microfluidic discharge-based optical sources for detection of biochemicals. Lab Chip. 2006;6:60–5. doi: 10.1039/b510332k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jeong H, Li T, Gianchandani YB, Park J. High precision cell slicing by harmonically actuated ultra-sharp Si x N y blades. J Micromechanics Microengineering. 2015;25:25007. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.