Abstract

Preclinical evidence suggests that concomitant BRAF and EGFR inhibition leads to sustained suppression of MAPK signaling and suppressed tumor growth in BRAF V600E colorectal cancer (CRC) models. Patients with refractory BRAF V600–mutant metastatic CRC (mCRC) were treated with a selective RAF kinase inhibitor (encorafenib) plus a monoclonal antibody targeting EGFR (cetuximab), with (n = 28) or without (n = 26) a PI3K-alpha inhibitor (alpelisib). The primary objective was to determine the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) or a recommended phase 2 dose. Dose-limiting toxicities were reported in three patients receiving dual- and two patients receiving triple-treatment. The MTD was not reached for either group and the Phase 2 doses were selected as 200 mg encorafenib (both groups) and 300 mg alpelisib. Combinations of cetuximab and encorafenib show promising clinical activity and tolerability in patients with BRAF-mutant mCRC; confirmed overall response rates of 19% and 18% were observed, and median progression-free survival was 3.7 and 4.2 months, for the dual- and triple-therapy groups, respectively.

Keywords: BRAF-mutant, metastatic colorectal cancer, BRAF inhibitor, EGFR inhibitor, PI3K inhibitor

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most commonly diagnosed cancer in men and the second in women; 693,900 patients with CRC died in 2012.(1) The anti–epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) monoclonal antibody cetuximab is indicated for wild-type RAS metastatic CRC (mCRC), either in combination with cytotoxic chemotherapy or as a single agent.

Investigations of the signaling pathways downstream of EGFR have shown that mutations of Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog (KRAS), Neuroblastoma RAS viral oncogene homolog (NRAS) and B-Raf proto-oncogene, serine/threonine kinase (BRAF) play an important role in cancer progression.(2) Mutations in the BRAF gene at valine 600 occur in approximately 7% of all cancers, including approximately 8% to 15% of CRCs.(3–5) BRAF-mutant CRC is molecularly distinct from BRAF wild-type CRC(6), indeed, a recent publication outlined four distinct consensus molecular subtypes of CRC and the majority of BRAF-mutations were found in one of the four subtypes.(7) BRAF-mutated CRC is associated with a significantly poorer prognosis and poor response to standard treatments, highlighting the unmet medical need for this group of patients.(8, 9)

Two BRAF inhibitors (vemurafenib and dabrafenib) have been approved for the treatment of BRAF-mutant melanoma.(10, 11) In contrast, BRAF inhibitors have shown limited efficacy in BRAF-mutant mCRC.(12–17) Preclinical studies of BRAF-mutant CRC and melanoma cell lines treated with selective BRAF V600 inhibitors have found that rapid EGFR-mediated reactivation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway contributed to the unresponsiveness of BRAF-mutant CRC cells.(12, 14)

Despite the limited efficacy of EGFR and BRAF inhibitors given as single agents in patients with BRAF-mutant CRC, preclinical evidence suggests that concomitant inhibition leads to sustained suppression of MAPK signaling resulting in reduced cell proliferation and increased antitumor activity.(12, 14, 18)

Activation of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT pathway has also been identified as a mechanism of resistance to BRAF inhibitors in BRAF-mutant CRC cell lines.(13, 19) Combinatorial approaches with BRAF and PI3K inhibitors have been suggested to improve outcomes in patients with BRAF-mutant mCRC.(13)

Encorafenib is a potent, selective RAF kinase inhibitor with promising activity in preclinical models, including greater potency compared with vemurafenib and dabrafenib.(20) Alpelisib is a class I α-specific PI3K inhibitor with antitumor activity in various cancer cell lines, especially those with documented PIK3CA mutations, and in tumor xenograft models with mutated or amplified PIK3CA.(21)

The synergistic activity of dual inhibition of BRAF, EGFR, or PI3K has been reported in preclinical studies, and preliminary preclinical activity has also been reported for triple inhibition (12–14, 18, 19). These observations led to the initiation of this phase 1b/2 study of encorafenib + cetuximab with or without alpelisib in patients with BRAF V600–mutant mCRC. Herein we report results of the phase 1b portion of this study, which had the primary aim of selecting a dose of encorafenib and alpelisib for phase 2 by determining the incidence of dose-limiting toxicities (DLTs).

Results

Patient Disposition and Characteristics

A total of 54 patients were enrolled into either the dual- (n = 26) or triple-combination (n = 28) therapy groups and received escalating doses of encorafenib and/or alpelisib (Table 1). By February 1, 2015, treatment had been discontinued in 24 (92.3%) of the patients in the dual-combination therapy group due to disease progression (n = 18; 69.2%), AEs (n = 3; 11.5%), physician decision (n = 1; 3.8%), patient decision (n = 1; 3.8%), or death (n = 1; 3.8%). In the triple-combination therapy group, treatment had been discontinued in 22 (78.6%) patients due to disease progression (n = 19; 67.9%), AEs (n = 2; 7.1%), or death (n = 1; 3.6%).

Table 1.

Dose-escalation cohorts for dual- and triple-combination therapies

| ENC + CTX n = 26 | ENC + ALP + CTX n = 28 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Patient number, n | Dose of encorafenib, mg qd | DLT | Patient number, n | Dose of encorafenib, mg qd | Dose of alpelisib, mg qd | DLT |

| 2 | 100 | None | 3 | 200 | 100 | None |

| 7 | 200 | G3 arthralgia (n = 1) | 8 | 200 | 200 | None |

| 9 | 400 | G3 vomiting (n = 1) | 7 | 300 | 200 | G4 acute renal failure (n = 1) |

| 8 | 450 | G3 QT interval prolongation (n = 1) | 10 | 200 | 300 | G3 bilateral interstitial pneumonitis (n = 1) |

Abbreviations: ENC + ALP + CTX, encorafenib combined with alpelisib and cetuximab; ENC + CTX, encorafenib combined with cetuximab; G3, grade 3; G4, grade 4; qd, daily.

Patient characteristics in the two groups were similar; however, more patients had a poorer ECOG PS in the dual-combination group than the triple-combination group (ECOG PS ≥1: 69.2% vs 35.7%, respectively) (Table 2); comparisons between the two groups should be made with caution. The majority of patients had received two prior lines of therapy and a considerable proportion had been treated with three or more lines of therapy (23% in the dual- and 11% in the triple-combination therapy groups). Fifteen (28%) patients had received prior EGFR targeted therapy in the form of cetuximab and/or panitumumab (7 [27%] in the dual-combination therapy group and 8 [29%] in the triple-combination therapy group). Most patients had BRAF V600E, only two patients had mutations outside the 600 codon.

Table 2.

Patient and disease characteristics at baseline

| ENC + CTX n = 26 | ENC + ALP + CTX n = 28 | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Female | 15 (58) | 18 (64) |

| Male | 11 (42) | 10 (36) |

| Age, median (range), years | 63 (43–80) | 59 (40–76) |

| Primary site of cancer derived, n (%) | ||

| Colon | 24 (92) | 25 (89) |

| Rectum | 2 (8) | 3 (11) |

| ECOG PS, n (%) | ||

| 0 | 8 (31) | 18 (64) |

| 1 | 16 (62) | 10 (36) |

| 2 | 2 (8) | 0 |

| Visceral involvement at baseline, n (%) | ||

| Liver | 15 (58) | 16 (57) |

| Peritoneum | 5 (19) | 8 (29) |

| Lactate dehydrogenase levels at baseline, n (%) | ||

| Normal | 9 (35) | 10 (36) |

| >upper limit of normal | 15 (58) | 14 (50) |

| Missing | 2 (8) | 4 (14) |

| Number of prior treatment regimens, n (%) | ||

| 1 | 7 (27) | 10 (36) |

| 2 | 8 (31) | 14 (50) |

| 3 | 5 (20) | 1 (4) |

| ≥ 3 | 6 (23) | 3 (11) |

| Best response to last prior therapy, n(%) | ||

| Partial response | 0 | 2 (7) |

| Stable disease | 10 (39) | 12 (43) |

| Progressive disease | 9 (35) | 9 (32) |

| Unknown/not applicable | 7 (27) | 5 (18) |

Abbreviations: ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; ENC + ALP + CTX, encorafenib combined with alpelisib and cetuximab; ENC + CTX, encorafenib combined with cetuximab.

Dose Determination

Twenty-one patients in the dual-combination therapy group and 25 patients in the triple-combination therapy group were considered evaluable for dose determination. Three DLTs were identified in the dual-combination therapy group: grade 3 arthralgia, grade 3 vomiting, and grade 3 corrected QT interval prolongation (one patient each), and two DLTs were identified in the triple-combination therapy group: grade 4 acute renal failure and grade 3 bilateral interstitial pneumonitis (one patient each; Table 1).

Following assessment of the overall tolerability of treatment, it was decided not to complete dose escalation up to the MTD in either of the treatment combinations, and only RP2Ds were established. Studies of single-agent alpelisib have suggested that a clinical dose of ≥270 mg is required for efficacy.(22) As one DLT was reported in the triple-combination therapy group at a dose level of 300 mg alpelisib (+ 200 mg encorafenib + cetuximab), it was considered unlikely that a dose of >300 mg alpelisib could be achieved. Hence, 300 mg alpelisib was established as the RP2D in the triple-combination therapy arm. Similarly, among the 7 patients treated at the dose of 300 mg encorafenib (+ 200 mg alpelisib + cetuximab), one patient experienced a DLT of Grade 4 acute renal failure suggesting that when combined with alpelisib, encorafenib should be dosed below 300 mg. Although higher encorafenib doses could have been used in the dual combination arm, the RP2D dose was kept consistent at 200 mg in both the dual and triple combinations in order to allow for the assessment of the safety and efficacy of the addition of alpelisib to the encorafenib + cetuximab combination. These dose levels fulfilled the protocol criteria for MTD/RP2D: ≥6 patients had been treated at this dose and either the posterior probability of targeted toxicity at this dose exceeded 50% or a minimum of 12 patients had been treated with the dual and triple combinations.

Safety

The overall safety profiles for the two therapy groups are shown in Table 3. AEs occurred in all patients in both treatment groups. Similar proportions of patients in the dual- and triple-combination therapy groups experienced fatigue (n = 13; 50% and n = 12; 43%) and vomiting (n = 12; 46% and n =14; 50%), respectively. Higher proportions of patients in the triple- than in the dual-combination therapy group experienced nausea (n = 17; 61% vs n = 8; 31%) and diarrhea (n = 15; 54% vs n = 5; 19%). Furthermore, dermatologic AEs were more common in the triple- than the dual-combination therapy group (rash [n = 10, 36% vs n = 5; 19%], dermatitis acneiform [n = 8; 29% vs n = 3; 12%], dry skin [n = 9; 32% vs n = 5; 19%] and melanocytic nevus [n = 7; 25% vs n = 1; 4%]). Eleven (39%) patients in the triple-combination therapy group exhibited hyperglycemia compared with two patients (8%) in the dual-combination therapy group. Grade 3/4 AEs were commonly reported in the both the dual- and triple-combination therapy groups (69% and 79%), respectively, with the most common grade 3/4 AEs being hypophosphatemia (n = 5; 19%) in the dual-combination therapy group and dyspnea and hyperglycemia (n = 3; 11% each) in the triple-combination therapy group.

Table 3.

Adverse events, regardless of treatment attribution, occurring in >20% of patients

| ENC + CTX n = 26 | ENC + ALP + CTX n = 28 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adverse event, n (%) | All grades | Grade 3/4 | All grades | Grade 3/4 |

| Fatigue | 13 (50.0) | 3 (11.5) | 12 (42.9) | 1 (3.6) |

| Vomiting | 12 (46.2) | 2 (7.7) | 14 (50.0) | 0 |

| Dyspnea | 9 (34.6) | 1 (3.8) | 5 (17.9) | 3 (10.7) |

| Abdominal pain | 8 (30.8) | 3 (11.5) | 7 (25.0) | 1 (3.6) |

| Nausea | 8 (30.8) | 0 | 17 (60.7) | 1 (3.6) |

| Hyperglycemia | 2 (7.7) | 0 | 11 (39.3) | 3 (10.7) |

| Back pain | 7 (26.9) | 1 (3.8) | 3 (10.7) | 1 (3.6) |

| Constipation | 7 (26.9) | 1 (3.8) | 4 (14.3) | 0 |

| Decreased appetite | 7 (26.9) | 0 | 8 (28.6) | 1 (3.6) |

| Hypophosphatasemia | 7 (26.9) | 5 (19.2) | 4 (14.3) | 1 (3.6) |

| Infusion-related | 7 (26.9) | 0 | 1 (3.6) | 0 |

| reaction | ||||

| Weight decreased | 7 (26.9) | 0 | 10 (35.7) | 1 (3.6) |

| Dysphonia | 2 (7.7) | 0 | 7 (25.0) | 0 |

| Melanocytic nevus | 1 (3.8) | 0 | 7 (25.0) | 0 |

| Peripheral edema | 2 (7.7) | 0 | 7 (25.0) | 0 |

| Cough | 6 (23.1) | 0 | 2 (7.1) | 1 (3.6) |

| Headache | 6 (23.1) | 0 | 4 (14.3) | 0 |

| Myalgia | 6 (23.1) | 0 | 4 (14.3) | 0 |

| Pain in extremity | 6 (23.1) | 0 | 2 (7.1) | 0 |

| Stomatitis | 6 (23.1) | 0 | 4 (14.3) | 1 (3.6) |

| Dysgeusia | 1 (3.8) | 0 | 6 (21.4) | 0 |

| Diarrhea | 5 (19.2) | 1 (3.8) | 15 (53.6) | 1 (3.6) |

| Dry skin | 5 (19.2) | 0 | 9 (32.1) | 0 |

| Rash | 5 (19.2) | 0 | 10 (35.7) | 0 |

| Hypomagnesaemia | 4 (15.4) | 0 | 8 (28.6) | 1 (3.6) |

| Dermatitis acneiform | 3 (11.5) | 0 | 8 (28.6) | 1 (3.6) |

| Pyrexia | 3 (11.5) | 0 | 8 (28.6) | 1 (3.6) |

All patients had at least 1 AE. Abbreviations: ENC + ALP + CTX, encorafenib combined with alpelisib and cetuximab; ENC + CTX, encorafenib combined with cetuximab.

Efficacy

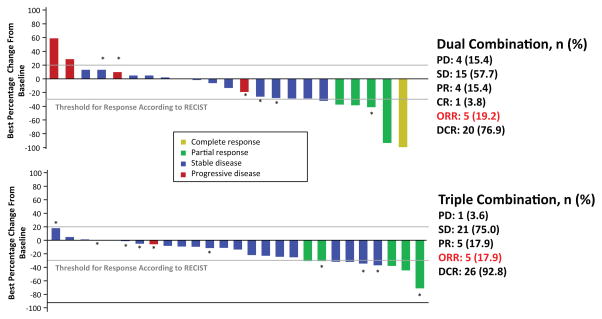

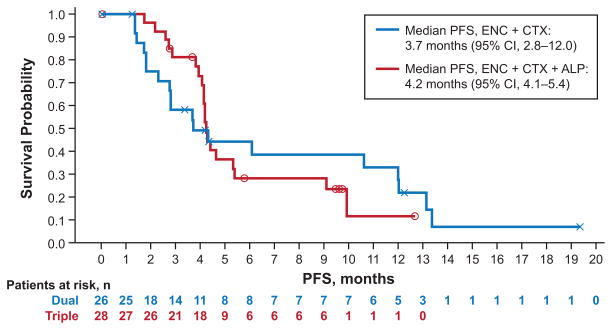

The dual- and triple-combination therapies both demonstrated efficacy in patients with BRAF-mutant mCRC (Table 4), with overall response rates of 19% in the dual- and 18% in the triple-combination therapy group (Fig. 1). Images of radiological response are shown in Supplementary Figure 1A–C. The median duration of response was 46 weeks in the dual- and 12 weeks in the triple-combination therapy group for patients with confirmed responses (five patients in either arm). Duration of exposure to treatment was longer in the dual-combination therapy arm (Supplementary Figure 2A) than the triple-combination therapy arm (Supplementary Figure 2B). Median progression-free survival (PFS) for the dual- and triple-combination therapy groups was 3.7 and 4.2 months, respectively (Fig. 2). At 50 weeks, 31% of patients in the dual- and 11% in the triple-combination therapy group remained on treatment.

Table 4.

Best overall response to treatment

| Response, n (%) | ENC + CTX n = 26 | ENC + ALP + CTX n = 28 |

|---|---|---|

| Complete response (CR) | 1 (3.8) | 0 |

| Partial response (PR) | 4 (15.4) | 5 (17.9) |

| Stable disease* (SD) | 15 (57.7) | 21 (75.0) |

| Progressive disease (PD) | 4 (15.4) | 1 (3.6) |

| Unknown | 2 (7.7) | 1 (3.6) |

| Overall response rate (CR + PR) | 5 (19.2) | 5 (17.9) |

| Disease control rate (CR + PR + SD) | 20 (76.9) | 26 (92.8) |

Abbreviations: ENC + ALP + CTX, encorafenib combined with alpelisib and cetuximab; ENC + CTX, encorafenib combined with cetuximab.

In the ENC + CTX group, 1 patient with SD had unconfirmed PR, and 4 patients in the ENC + ALP + CTX group with SD had unconfirmed PR.

Figure 1. Waterfall plot of best percentage change of tumor size from baseline by best response.

Data cutoff date: February 1, 2015. *Patients treated at the RP2D; Abbreviations: CR, complete response; DCR, disease control rate; ENC + ALP + CTX, encorafenib combined with alpelisib and cetuximab; ENC + CTX, encorafenib combined with cetuximab; ORR, overall response rate; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response; RECIST, Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors; RP2D, recommended phase 2 dose; SD, stable disease.

Figure 2. Progression-free survival for all patients.

Abbreviations: ENC + ALP + CTX, encorafenib combined with alpelisib and cetuximab; ENC + CTX, encorafenib combined with cetuximab; PFS, progression-free survival. The two cohorts were recruited sequentially.

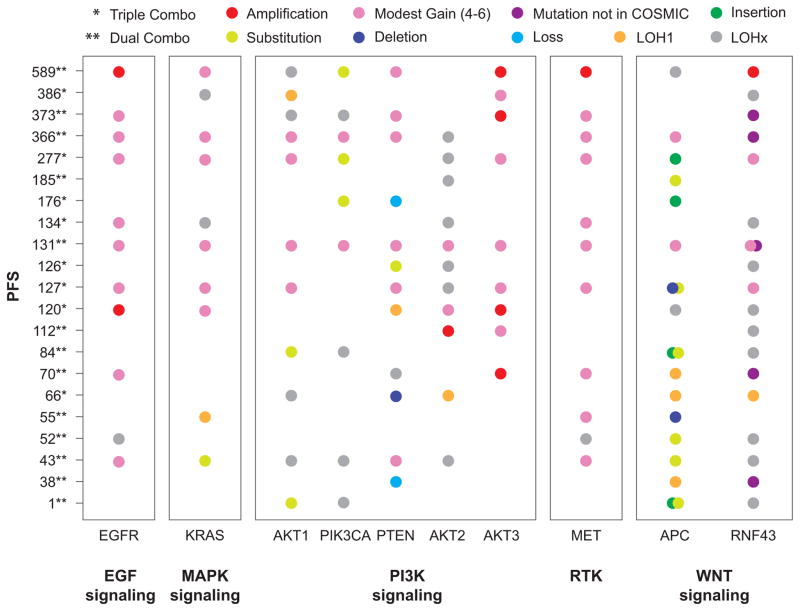

Biomarker Analyses

Fresh tumor biopsies were collected before and during treatment for 21 patients (n = 13 in dual- and n = 8 in triple-combination arm). Genes from key signaling pathways (MAPK, PI3K, WNT/β-catenin, and EGFR) were investigated over the course of treatment in both treatment combinations (Fig. 3). The majority of mutations were present pre-enrolment in the study. Significant correlations between exploratory genetic analyses and clinical outcomes were not observed in this small sample of patients. However, some interesting trends were noted.

Figure 3. Progression-free survival vs genetic alterations and allele frequency by gene pathways.

Abbreviations: APC, adenomatous polyposis coli; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; ENC + ALP + CTX, encorafenib combined with alpelisib and cetuximab; ENC + CTX, encorafenib combined with cetuximab; KRAS, Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog; LOH1, copy-loss loss of heterozygosity; LOHx, copy-neutral loss of heterozygosity; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; MET, MET proto-oncogene, receptor tyrosine kinase; PI3K, phosphoinositide 3-kinase; PTEN, phosphatase and tensin homolog; RNF43, ring finger protein 43; RTK, receptor tyrosine kinase.

At baseline, KRAS gain of copy number was observed in 6 of 21 patients and neutral LOH (duplication of one copy and concurrent loss of the other) was observed in 2 patients. KRAS gain was seen both in patients with long PFS as well as shorter PFS, suggesting that modest gains of KRAS did not preclude response to the encorafenib/cetuximab combination.

Patients with EGFR amplification appeared to experience longer PFS. Gain of copies of the EGFR gene were seen in ten patients; the majority of these patients also had MET copy number gain, most likely due to global amplification of chromosome 7. Six patients treated with the dual combination showed gain of copies in the EGFR gene and these patients had a median of 248 days of PFS (range, 43 to 589 days). One patient had a complete response (CR), two had a partial response (PR), two had a stable disease (SD) and one had progressive disease (PD). In contrast, the seven patients in the dual-combination therapy group without alteration in the EGFR gene had a median of 84 days of PFS (range, 1 to 185 days); one patient had a PR. Four patients receiving triple treatment showed gain of copies in the EGFR gene, and had a median of 130 days of PFS (range, 120 to 277 days); however, none of the patients had tumor regression meeting RECIST criteria for a radiological response (all target tumor shrinkage was between 0% and 28%). The four patients in this treatment group who did not have any alterations in the EGFR gene exhibited prolonged PFS of 66, 126, 176, and 386 days, and one patient achieved a PR. However, these patients had alterations in the PI3K pathway, including phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN), PIK3CA, or AKT1; hence the addition of alpelisib may explain the differences in observation.

Initial observations for patients with PI3K pathway alterations did not reveal clear associations with treatment response. Patients who received dual treatment appeared to have similar responses to patients who received triple treatment. Seven patients in the dual-combination therapy group had PIK3CA alterations; this did not appear to preclude benefit because the median duration of PFS for these patients was 248 days (range, 1 to 589), one patient experienced CR and two had PRs. Only two patients in the triple-combination therapy group had PIK3CA alterations. One patient had a PFS of 176 days and the other 277 days. Five patients had PTEN loss or deletions: the one patient in the dual-combination therapy group did not respond and had a PFS of 38 days and among the four patients in the triple-combination therapy group, one had a PR and three did not respond (median PFS of 123 days (66–176).

Alterations in the WNT pathway were also observed. Fourteen patients (67%) had Adenomatous Polyposis Coli (APC) mutations: nine in the dual and five in the triple-combination therapy group. Patients treated with dual-combination therapy whose tumors harbored APC mutations had relatively short PFS, with a median of 70 days (range, 1 to 589). Patients who received triple-combination therapy had a median PFS of 127 days (range, 66 to 277 days). Seventeen patients (81%) had Ring Finger Protein 43 (RNF43) alterations, and the majority, eleven patients, was treated with the dual-combination. These 11 patients had a median of 112 days of PFS (range, 1 to 589), with three patients having a PR and one a CR. The six patients with RNF43 alterations that were treated with the triple-combination treatment responded well to treatment and had median PFS of 130 days (120–386).

The patient with the best response to dual-combination therapy (CR; 100% best percentage change from the baseline) had alterations in EGFR, AKT1, PIK3CA, PTEN, AKT3, MET, and RNF43, whereas the patient with the best response to triple-combination therapy (PR; 71% best percentage change from baseline) had alterations in PTEN, AKT2, and RNF43.

End-of-treatment biopsies were collected from six patients who had responded to study treatment. Interestingly, acquired mutations or amplifications of the KRAS gene were noted in four of these patients. PTEN loss was observed in one patient, and an AKT1 mutation was seen in the remaining patient.

Pharmacokinetics

Exposure of encorafenib increased with dose in the dual-combination group and had a half-life that ranged from 3 to 4 hours (Supplementary Table S1). Exposure was similar to levels observed in a monotherapy study (K. Litwiler, personal communication; Cmax [mean ± standard deviation]: 1427 ± 824 ng/mL, Tmax [median (range)]: 2 (1–4) hours and AUCtau [mean ± standard deviation]: 7172 ± 2888 h·ng/mL with 200 mg encorafenib at steady state in the current study).

For the triple-combination therapy group, the exposure of 200 mg encorafenib in the presence of 100 mg alpelisib was similar to that in the dual-combination therapy group. However, the exposure of 200 mg encorafenib increased by about 2-fold in the presence of 300 mg alpelisib (Cmax [mean ± standard deviation]: 2394 ± 2077 ng/mL, Tmax [median (range)]: 3 (1–8) hours and AUCtau [mean ± standard deviation]: 12,948 ± 10,649 h·ng/mL at steady state; Supplementary Table S1). Exposure of alpelisib increased with dose and was similar to levels observed in an unpublished monotherapy study (data not shown; Cmax [mean ± standard deviation]: 2743 ± 520 ng/mL, Tmax [median (range)]: 4 (2–6) hours and AUCtau [mean ± standard deviation]: 25,126 ± 3513 h·ng/mL with 300 mg alpelisib at steady state in the current study).

Discussion

The primary objective of the phase 1b portion of this study was to establish a recommended dose for the dual- and triple-combination therapies for use in the phase 2 section of the study. The selected doses were 200 mg encorafenib daily plus cetuximab in the dual-combination therapy group and 200 mg encorafenib daily plus 300 mg alpelisib daily plus cetuximab in the triple-combination therapy group. Following an overall assessment of tolerability and observation of objective responses in all tested dose cohorts, it was decided not to proceed to the MTD in either the dual- or triple-combination therapy arms, and doses for the triple-combination therapy were selected on the basis of the overall tolerability profiles. Although higher encorafenib doses were likely to have been tolerated in the dual combination, the RP2D was selected to be the same in both groups to allow for the assessment of safety and efficacy of additive alpelisib compared with encorafenib plus cetuximab dual-combination therapy.

Both the dual- and triple-combination treatments showed clinical efficacy and acceptable safety profiles in patients with BRAF-mutant mCRC. Efficacy and safety in the two groups may be compared only with caution: the ECOG PS suggests the health of patients in the dual-combination therapy group was poorer than that of patients in the triple-combination therapy group prior to the start of treatment and patients in the triple-combination therapy group also showed a better response to the last prior therapy than patients in the dual-combination therapy group. This phase 1b portion of the study was also not powered or designed for comparison purposes, and patient numbers are small.

Previous studies of single-agent BRAF or EGFR inhibitors have shown limited activity in patients with BRAF-mutant mCRC.(12–14, 23–27) However, clinical studies of combinations of BRAF inhibitors with EGFR inhibitors or MEK inhibitors have shown improved efficacy in this patient population. (16, 17, 28, 29) Results from our study compare favorably with combinations of BRAF and EGFR inhibitors in these studies. In our study ORRs of 19% in the dual- and 18% in the triple-combination therapy group were achieved. In a study of 55 patients treated with dabrafenib plus panitumumab vs dabrafenib + panitumumab + trametinib the dual combination of BRAF and EGFR inhibitor achieved an ORR of 10% and the triple combination of BRAF, EGFR and MEK inhibitors achieved an ORR of 26%.(28) In another study of 15 patients treated with vemurafenib plus panitumumab two (13%) achieved a PR.(29) Furthermore, a phase 2 study of vemurafenib in nonmelanoma cancers with BRAF V600 mutations that enrolled 27 patients with BRAF-mutant CRC showed an ORR of 4% when treated with vemurafenib + cetuximab.(16) Median PFS in our study (3.7 months in the dual- and 4.3 months in the triple-combination therapy arm) also compare well with results from these studies: 3.2 months (95% CI: 1.6–5.3 months) for vemurafenib + panitumumab(29) and 3.7 months (95% CI: 1.8–5.1) for vemurafenib + cetuximab.(16) It should be noted that these studies were small and further follow-up is required. The duration of treatment in our study of patients with previously treated disease, was also encouraging.

In our study, the safety profile was acceptable for both combination treatments, and all three drugs were given continuously in the triple therapy, which has been challenging in other targeted combinations. More dermatologic AEs were reported in the triple- than the dual-combination therapy group. It should be noted, however, that the incidence of dermatologic AEs was much lower than has been previously reported for single-agent use of BRAF inhibitors (67% of 18 patients had hand-foot skin reaction)(30) or EGFR inhibitors (82% of 116 patients had papulopustular rash)(31), consistent with an opposing effect of encorafenib and cetuximab on ERK signaling in skin. Paradoxical activation of ERK signaling in BRAF wild-type tissues with BRAF inhibitors has been previously reported.(32, 33) It is therefore likely that encorafenib opposes cetuximab-mediated inhibition of ERK signaling, which may decrease skin toxicity with the combination. More cases of melanocytic nevi were seen in the triple-combination therapy than in the dual-combination therapy arm (25% versus 4%), possibly secondary to higher effective doses of encorafenib in the triple-combination therapy arm as encorafenib exposure was increased 2-fold with the addition of 300 mg alpelisib. Hyperglycemia was more common in the triple- than the dual-combination therapy group due to the ability of PI3K inhibitors to regulate the insulin-like growth factor receptor. Compared with the incidence of hyperglycemia in patients with solid tumors treated with single-agent alpelisib (47% all grade; 24% grade 3/4),(34) the incidences reported for the triple-therapy group in this trial were lower, albeit at different dose levels.

Alterations in genes associated with the key signaling pathways were assessed and correlated with clinical activity. Due in part to the limited availability of tumor biopsies in the phase 1 population of the study, no significant correlations could be determined, and further follow-up will be carried out in phase 2; however, some preliminary observations were noted. A subgroup of patients with EGFR amplifications or gain of copies, especially those patients who received dual-combination therapy, responded well to study treatment, and better than patients without EGFR alterations. These results suggest that the presence of EGFR alterations may identify tumors more dependent on EGFR signaling(35–37) that are thus more sensitive to combined EGFR- and BRAF-targeted treatment, whereas in patients with no EGFR-mediated pathway activation, other signaling pathways may be activated and may need to be co-targeted with BRAF to lead to tumor regressions.

Patients with WNT pathway alterations, especially those patients with APC mutations, had a tendency towards lower PFS rates. This trend was not clear for RNF43 mutations, suggesting, in agreement with previous theories, that RNF43 mutations do not activate the WNT pathway in the same manner as APC mutations.(38) It will be of interest to see whether trials of combination treatments targeting the WNT pathway (eg, NCT02278133) yield higher response rates.

As has been previously documented for BRAF-mutant mCRC, alterations in the PI3K pathway were noted in the limited patient samples.(17) Unfortunately, the majority of patients with PIK3CA mutations received the dual-combination treatment; however, these patients still responded and remained on treatment for prolonged periods of time, suggesting that such activating mutations may not be a primary source of resistance. Furthermore, some patients with PTEN loss responded well to both the triple- and dual-combination treatments. Due to the small sample size, however, it is impossible to draw significant correlations. Data from previous studies have reported conflicting information with either no association between response to cetuximab treatment and PI3KCA mutation/PTEN expression or a correlation with low response to cetuximab.(25, 39)

Interestingly, the few samples collected during acquired resistance showed MAPK activation, where patients developed either KRAS mutations or amplifications. Similar results have been previously reported for other RAF/EGFR/MEK targeted treatments.(40)

No evidence of drug–drug interaction between encorafenib and cetuximab was observed in the dual-combination therapy group. In the triple-combination therapy group, a mild drug–drug interaction was observed with encorafenib (encorafenib exposure increased 2-fold) in the presence of high alpelisib dose levels, possibly due to alpelisib inhibiting the metabolic enzyme (CYP3A4) of encorafenib. Alpelisib exposure was not affected by encorafenib and cetuximab.

In conclusion, data from this phase 1b study show promising clinical activity and tolerability, warranting further evaluation.

Patients and methods

Study Design

This multicenter, open-label, phase 1b dose-escalation study enrolled patients with BRAF V600-mutant mCRC. The primary objective of phase 1b was to determine the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) and/or recommended dose for phase 2 (RP2D) of encorafenib in combination with cetuximab or with cetuximab and alpelisib.

Adult patients with mCRC were enrolled on the basis of documented wild-type KRAS and a BRAF V600 mutation. Eligibility criteria included: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS) of ≤2, either progression after ≥1 prior standard-of-care regimen or intolerance to irinotecan-based regimens, and life expectancy of ≥3 months. All patients gave written informed consent, per Declaration of Helsinki recommendations and the protocol was reviewed and approved by a properly constituted Institutional Review Board prior to study start. The study is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01719380).

Study Treatment

Patients were assigned sequentially to either encorafenib and cetuximab (dual) or encorafenib, cetuximab, and alpelisib (triple) combination therapy groups. Treatment cycles were 28 days in length. Cetuximab was dosed intravenously according to the label for patients with mCRC: a 400 mg/m2 loading dose (cycle 1 day 1) and 250 mg/m2 for subsequent weekly doses. In the dual combination, the starting dose of encorafenib was chosen as 100 mg daily based on available data from the first-in-human study of encorafenib,(41) including a single agent MTD/RP2D of 450 mg, the estimation of the Bayesian logistic regression model (BLRM), and the escalation with overdose control (EWOC) criteria. The triple combination was not initiated until a minimum of 12 evaluable patients had been treated with the dual combination. The starting dose of encorafenib in the triple-combination therapy group was based on the dual-combination dose, and the starting dose of alpelisib (100 mg) was selected at 25% of the single-agent MTD identified in a phase 1 clinical study of alpelisib in patients with solid tumors.(34) Dose-escalation decisions were based on data from all evaluable patients, including safety information, DLTs, all grade ≥2 toxicity data during cycle 1, and pharmacokinetics (PK). The recommended dose for each level was guided by a Bayesian logistic regression model.(42, 43) A DLT was defined as an adverse event (AE) or abnormal lab value assessed as unrelated to disease, disease progression, inter-current illness, or concomitant medications that occurred within the first 28 days of treatment, with the exceptions listed in Supplementary Table S2. In order to be evaluable, patients had to complete a minimum of one cycle of treatment with the minimum safety evaluation and drug exposure (21 of the 28 oral daily doses and the cetuximab loading dose, plus two weekly doses within the 28-day cycle). The MTD was defined as the highest combination drug dosage not causing medically unacceptable DLTs in >35% of treated patients in the first cycle.

Study Assessments

Tumor response was evaluated locally based on RECIST v1.1. assessments, by means of CT scan with intravenous contrast of chest, abdomen, and pelvis, which were performed at screening and every 6 weeks after starting study treatment until disease progression. The best overall response was defined as the best response recorded from the start of the treatment until disease progression/relapse. The study required that for a response of PR or CR, changes in tumor measurements must be confirmed by repeat assessments that should be performed at least 4 weeks and no later than 6 weeks after the criteria for response were first met.

Safety was monitored at screening and throughout the treatment period by physical examination and collection of AEs. Blood samples for plasma PK analysis were collected from all patients during treatment. A full PK profile (pre-dose, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 24 h) was performed on day 1 of cycles 1 and 2. Samples were assayed using validated liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. When feasible, fresh tumor biopsies were collected before and during treatment for the investigation of pharmacodynamics, including comprehensive genomic analysis. Somatic mutations, loss of heterozygosity, and copy number aberrations were assessed by Foundation Medicine assay analytics. Additional annotations from the Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer were used to filter functional mutations.

Statistical methods

An adaptive BLRM guided by the EWOC principle directed the dose escalation to its MTD/RP2D.(42) A 10-parameter BLRM for combination treatment was fitted on the cycle 1 DLT data accumulated throughout the dose escalation to model the dose-toxicity relationship of encorafenib, cetuximab and alpelisib given in combination. Dose recommendation was based on posterior summaries including the mean, median, standard deviation, 95% credibility interval and the probability that the true DLT rate for each dose lies in one of the following categories: under-dosing (0–16%), targeted toxicity (16–35%) or excessive toxicity (35–100%). The recommended next dose was the one with the highest posterior probability of DLT in the targeted toxicity interval and less than 25% chance of excessive toxicity.

Initially, cohorts of 3–6 evaluable patients were enrolled. At least six evaluable patients were treated at MTD/RP2D. PFS was calculated as the time from the start date of study drug until documented disease progression or death due to any cause. Patients who have not progressed or died at the time of the data cut-off were censored at the date of last tumor assessment.

Supplementary Material

SIGNIFICANCE.

Herein we demonstrate that dual- (encorafenib plus cetuximab) and triple- (encorafenib plus cetuximab and alpelisib) combination treatments are tolerable and provide promising clinical activity in the difficult-to-treat patient population with BRAF-mutant mCRC.

Acknowledgments

Role of the Funding Source

The trial was planned, initiated, and sponsored by Novartis Pharmaceuticals. The sponsor was responsible for data gathering and pharmacovigilance, shared safety data during the study with the corresponding author and contributed to preparing and reviewing the report for publication submission. The sponsor and authors were responsible for data analysis and interpretation. The corresponding author had full access to all the study data and all authors approved the manuscript for publication submission.

Encorafenib (LGX818) is owned by Array BioPharma Inc. Samia Kabi and Nassim Sleiman from Novartis Pharmaceuticals and Jennifer Regensburger from Array BioPharma Inc. are thanked for their assistance with preparing tables, figures and listings of the study data. Ashwin Gollerkeri and Victor Sandor from Array BioPharma Inc. are thanked for their critical review and editing of the manuscript.

Editorial assistance was provided by Zoe Crossman of Articulate Science Ltd. and was funded by Novartis Pharmaceuticals.

Grant Support

Martin Schuler: German Cancer Consortium (DKTK), partner site University Hospital Essen; and Oncology Center of Excellence grant (no. 110534) of the German Cancer Aid.

Josep Tabernero and Elena Elez: Financial support for this work was provided by the EU Seventh Framework Programme (COLTHERES, grant agreement 259015) and the Cellex Foundation.

Takayuki Yoshino: Research grants (to institution): Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma Co. Ltd

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

JT reports compensation for an advisory role from Amgen, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Chugai, Lilly, MSD, Merck, Novartis, Roche, Sanofi, Symphogen, Takeda and Taiho. MS reports compensation for advisory boards from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Novartis; compensation for CME presentations from Alexion, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, GlaxoSmithKline, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi and research grants (to institution) from Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis. TY reports research grants (to institution) from Daiichi Sankyo, Taiho, Bayer Yakuhin, Lilly, Pfizer, Yakult Honsha, Chugai, Dainippon Sumitomo; personal fees from Merck Serono, Chugai, Takeda. ML reports research grants (to institution) from Astellas, Johnson & Johnson and Sanofi. JEF reports current employment with Novartis and personal fees from N-of-One Therapeutics, Merrimack Pharmaceuticals. SS reports research grants (to institution) from Novartis and compensation for an advisory role from Novartis. RY reports research grants (to institution) from Novartis, GlaxoSmithKline, Genentech and compensation for advisory boards from GlaxoSmithKline. ZW reports research grants (to institution) from Novartis. EA, AC, SJ, ET and TD report employment with Novartis. KM reports employment with Array BioPharma Inc. RVG, EE, JCB, AS, J-PD, YY, FE, H-J L and JHMS have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Authors’ Contributions

RVG, JT, RY, EA, SJ, TD, ET, and JHMS researched the scientific literature. RVG, JT, EA, AC, TD, ET, and JHMS contributed to study design. RVG, JT, EE, JB, AS, MS, TY, J-PD, YY, ML, JEF, FE, SS, RY, H-JL, ZW, and JHMS collected data. RVG, JT, EA, AC, SJ, TD, ET, KM, and JHMS analyzed and interpreted data. All authors participated in drafting or reviewing of the report and all authors approved the submitted version.

References

- 1.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2015;65(2):87–108. doi: 10.3322/caac.21262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chappell WH, Steelman LS, Long JM, Kempf RC, Abrams SL, Franklin RA, et al. Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK and PI3K/PTEN/Akt/mTOR inhibitors: rationale and importance to inhibiting these pathways in human health. Oncotarget. 2011 Mar;2(3):135–64. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Roock W, Biesmans B, De Schutter J, Tejpar S. Clinical biomarkers in oncology: focus on colorectal cancer. Mol Diagn Ther. 2009;13(2):103–14. doi: 10.1007/BF03256319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rizzo S, Bronte G, Fanale D, Corsini L, Silvestris N, Santini D, et al. Prognostic vs predictive molecular biomarkers in colorectal cancer: is KRAS and BRAF wild type status required for anti-EGFR therapy? Cancer Treat Rev. 2010 Nov;36( Suppl 3):S56–61. doi: 10.1016/S0305-7372(10)70021-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tejpar S, Bertagnolli M, Bosman F, Lenz HJ, Garraway L, Waldman F, et al. Prognostic and predictive biomarkers in resected colon cancer: current status and future perspectives for integrating genomics into biomarker discovery. Oncologist. 2010;15(4):390–404. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2009-0233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shen L, Toyota M, Kondo Y, Lin E, Zhang L, Guo Y, et al. Integrated genetic and epigenetic analysis identifies three different subclasses of colon cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007 Nov 20;104(47):18654–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704652104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guinney J, Dienstmann R, Wang X, de Reynies A, Schlicker A, Soneson C, et al. The consensus molecular subtypes of colorectal cancer. Nat Med. 2015 Nov;21(11):1350–6. doi: 10.1038/nm.3967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Cutsem E, Kohne CH, Lang I, Folprecht G, Nowacki MP, Cascinu S, et al. Cetuximab plus irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin as first-line treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer: updated analysis of overall survival according to tumor KRAS and BRAF mutation status. J Clin Oncol. 2011 May 20;29(15):2011–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.5091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Modest DP, Jung A, Moosmann N, Laubender RP, Giessen C, Schulz C, et al. The influence of KRAS and BRAF mutations on the efficacy of cetuximab-based first-line therapy of metastatic colorectal cancer: an analysis of the AIO KRK-0104-trial. Int J Cancer. 2012 Aug 15;131(4):980–6. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zelboraf. Summary of Product Characteristics. [Internet] F. Hoffmann-La Roche; 2012. [cited May 2015]. Available at: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/002409/WC500124317.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tafinlar. Summary of Product Characteristics [Internet] GlaxoSmithKline; 2013. [cited May 2015]. Available at: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/002604/WC500149671.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Corcoran RB, Ebi H, Turke AB, Coffee EM, Nishino M, Cogdill AP, et al. EGFR-mediated reactivation of MAPK signaling contributes to insensitivity of BRAF mutant colorectal cancers to RAF inhibition with vemurafenib. Cancer Discov. 2012 Mar;2(3):227–35. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mao M, Tian F, Mariadason JM, Tsao CC, Lemos R, Jr, Dayyani F, et al. Resistance to BRAF inhibition in BRAF-mutant colon cancer can be overcome with PI3K inhibition or demethylating agents. Clin Cancer Res. 2013 Feb 1;19(3):657–67. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prahallad A, Sun C, Huang S, Di Nicolantonio F, Salazar R, Zecchin D, et al. Unresponsiveness of colon cancer to BRAF(V600E) inhibition through feedback activation of EGFR. Nature. 2012 Jan 26;483(7387):100–3. doi: 10.1038/nature10868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kopetz S, Desai J, Chan E, Hecht JR, O'Dwyer PJ, Lee RJ, et al. PLX4032 in metastatic colorectal cancer patients with mutant BRAF tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(15s):3534. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hyman DM, Puzanov I, Subbiah V, Faris JE, Chau I, Blay JY, et al. Vemurafenib in Multiple Nonmelanoma Cancers with BRAF V600 Mutations. N Engl J Med. 2015 Aug 20;373(8):726–36. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1502309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Corcoran RB, Atreya CE, Falchook GS, Kwak EL, Ryan DP, Bendell JC, et al. Combined BRAF and MEK Inhibition With Dabrafenib and Trametinib in BRAF V600–Mutant Colorectal Cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2015 Sep 21;33(34):4023–31. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.2471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang H, Higgins B, Kolinsky K, Packman K, Bradley WD, Lee RJ, et al. Antitumor activity of BRAF inhibitor vemurafenib in preclinical models of BRAF-mutant colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 2012 Feb 1;72(3):779–89. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-2941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Caponigro G, Cao ZA, Zhang X, Wang HQ, Fritsch CM, Stuart DD. Efficacy of the RAF/PI3Ka/anti-EGFR triple combination LGX818 + BYL719 + cetuximab in BRAFV600E colorectal tumor models. Cancer Research. 2013 Apr 15;73(8 Supplement):2337. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stuart DD, Li N, Poon DJ, Aardalen K, Kaufman S, Merritt H, et al. Preclinical profile of LGX818: A potent and selective RAF kinase inhibitor. Cancer Res. 2012;72(8) Abstract 3790. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fritsch C, Huang A, Chatenay-Rivauday C, Schnell C, Reddy A, Liu M, et al. Characterization of the novel and specific PI3Kalpha inhibitor NVP-BYL719 and development of the patient stratification strategy for clinical trials. Mol Cancer Ther. 2014 May;13(5):1117–29. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-13-0865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Juric D, Rodon J, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, Burris HA, Bendell J, Berlin JD, et al. BYL719, a next generation PI3K alpha specific inhibitor: Preliminary safety, PK, and efficacy results from the first-inhuman study. Cancer Research. 2012 Apr 15;72(8 Supplement):CT-01. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pietrantonio F, Petrelli F, Coinu A, Di Bartolomeo M, Borgonovo K, Maggi C, et al. Predictive role of BRAF mutations in patients with advanced colorectal cancer receiving cetuximab and panitumumab: a meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer. 2015 Mar;51(5):587–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.01.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rowland A, Dias MM, Wiese MD, Kichenadasse G, McKinnon RA, Karapetis CS, et al. Meta-analysis of BRAF mutation as a predictive biomarker of benefit from anti-EGFR monoclonal antibody therapy for RAS wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2015 Jun 9;112(12):1888–94. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2015.173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Roock W, Claes B, Bernasconi D, De Schutter J, Biesmans B, Fountzilas G, et al. Effects of KRAS, BRAF, NRAS, and PIK3CA mutations on the efficacy of cetuximab plus chemotherapy in chemotherapy-refractory metastatic colorectal cancer: a retrospective consortium analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2010 Aug;11(8):753–62. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70130-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yuan ZX, Wang XY, Qin QY, Chen DF, Zhong QH, Wang L, et al. The prognostic role of BRAF mutation in metastatic colorectal cancer receiving anti-EGFR monoclonal antibodies: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2013 Jun 11;8(6):e65995. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Seymour MT, Brown SR, Middleton G, Maughan T, Richman S, Gwyther S, et al. Panitumumab and irinotecan versus irinotecan alone for patients with KRAS wild-type, fluorouracil-resistant advanced colorectal cancer (PICCOLO): a prospectively stratified randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013 Jul;14(8):749–59. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70163-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Atreya CE, Van Cutsem E, Bendell JC, Andre T, Schellens JHM, Gordon MS, et al. Updated efficacy of the MEK inhibitor trametinib (T), BRAF inhibitor dabrafenib (D), and anti-EGFR antibody panitumumab (P) in patients (pts) with BRAF V600E mutated (BRAFm) metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:103. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yaeger R, Cercek A, O'Reilly EM, Reidy DL, Kemeny N, Wolinsky T, et al. Pilot trial of combined BRAF and EGFR inhibition in BRAF-mutant metastatic colorectal cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2015 Mar 15;21(6):1313–20. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-2779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gomez-Roca CA, Delord J, Robert C, Hidalgo M, von Moos R, Arance A, et al. Encorafenib (LGX818), an oral BRAF inhibitor, in patients (pts) with BRAF V600E metastatic colorectal cancer (MCRC): Results of dose expansion in an open-label, Phase 1 study. Annals of Oncology. 2014 Sep 01;25(suppl 4):535. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jaka A, Gutierrez-Rivera A, Lopez-Pestana A, Del Alcazar E, Zubizarreta J, Vildosola S, et al. Predictors of Tumor Response to Cetuximab and Panitumumab in 116 Patients and a Review of Approaches to Managing Skin Toxicity. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2015 Jul-Aug;106(6):483–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ad.2015.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hatzivassiliou G, Song K, Yen I, Brandhuber BJ, Anderson DJ, Alvarado R, et al. RAF inhibitors prime wild-type RAF to activate the MAPK pathway and enhance growth. Nature. 2010 Mar 18;464(7287):431–5. doi: 10.1038/nature08833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Poulikakos PI, Zhang C, Bollag G, Shokat KM, Rosen N. RAF inhibitors transactivate RAF dimers and ERK signalling in cells with wild-type BRAF. Nature. 2010 Mar 18;464(7287):427–30. doi: 10.1038/nature08902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Juric D, Burris H, Schuler M, Schellens J, Berlin J, Seggewiβ-Bernhardt R, et al. Phase I study of the PI3Kα inhibitor BYL719, as a single agent in patients with advanced solid tumors (AST) Annals of Oncology. 2014 Sep 01;25(suppl 4):451PD. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moroni M, Veronese S, Benvenuti S, Marrapese G, Sartore-Bianchi A, Di Nicolantonio F, et al. Gene copy number for epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and clinical response to antiEGFR treatment in colorectal cancer: a cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2005 May;6(5):279–86. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(05)70102-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sartore-Bianchi A, Moroni M, Veronese S, Carnaghi C, Bajetta E, Luppi G, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor gene copy number and clinical outcome of metastatic colorectal cancer treated with panitumumab. J Clin Oncol. 2007 Aug 1;25(22):3238–45. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.5956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cappuzzo F, Finocchiaro G, Rossi E, Janne PA, Carnaghi C, Calandri C, et al. EGFR FISH assay predicts for response to cetuximab in chemotherapy refractory colorectal cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 2008 Apr;19(4):717–23. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Koo BK, Spit M, Jordens I, Low TY, Stange DE, van de Wetering M, et al. Tumour suppressor RNF43 is a stem-cell E3 ligase that induces endocytosis of Wnt receptors. Nature. 2012 Aug 30;488(7413):665–9. doi: 10.1038/nature11308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Karapetis CS, Jonker D, Daneshmand M, Hanson JE, O'Callaghan CJ, Marginean C, et al. PIK3CA, BRAF, and PTEN status and benefit from cetuximab in the treatment of advanced colorectal cancer--results from NCIC CTG/AGITG CO.17. Clin Cancer Res. 2014 Feb 1;20(3):744–53. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ahronian LG, Sennott EM, Van Allen EM, Wagle N, Kwak EL, Faris JE, et al. Clinical Acquired Resistance to RAF Inhibitor Combinations in BRAF-Mutant Colorectal Cancer through MAPK Pathway Alterations. Cancer Discov. 2015 Apr;5(4):358–67. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-14-1518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dummer R, Robert C, Nyakas M, McArthur G, Kudchadkar RR, Gomez-Roca C, et al. Initial results from a Phase I, open-label, dose escalation study of the oral BRAF inhibitor LGX818 in patients with BRAF V600 mutant advanced or metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:9028. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Neuenschwander B, Branson M, Gsponer T. Critical aspects of the Bayesian approach to phase I cancer trials. Stat Med. 2008 Jun 15;27(13):2420–39. doi: 10.1002/sim.3230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Neuenschwander B, Capkun-Niggli G, Branson M, Spiegelhalter DJ. Summarizing historical information on controls in clinical trials. Clin Trials. 2010 Feb;7(1):5–18. doi: 10.1177/1740774509356002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.