Summary

When abruptly exposed to toxic levels of hexavalent uranium, the extremely thermoacidophilic archaeon Metallosphaera prunae, originally isolated from an abandoned uranium mine, ceased to grow, and concomitantly exhibited heightened levels of cytosolic ribonuclease activity that corresponded to substantial degradation of cellular RNA. The M. prunae transcriptome during ‘uranium-shock’ implicated VapC toxins as possible causative agents of the observed RNA degradation. Identifiable VapC toxins and PIN-domain proteins encoded in the M. prunae genome were produced and characterized, three of which (VapC4, VapC7, VapC8) substantially degraded M. prunae rRNA in vitro. RNA cleavage specificity for these VapCs mapped to motifs within M. prunae rRNA. Furthermore, based on frequency of cleavage sequences, putative target mRNAs for these VapCs were identified; these were closely associated with translation, transcription, and replication. It is interesting to note that Metallosphaera sedula, a member of the same genus and which has a nearly identical genome sequence but not isolated from a uranium-rich biotope, showed no evidence of dormancy when exposed to this metal. M. prunae utilizes VapC toxins for post-transcriptional regulation under uranium stress to enter a cellular dormant state, thereby providing an adaptive response to what would otherwise be a deleterious environmental perturbation.

Keywords: Metallosphaera, VapC toxins, uranium stress, dormancy

Introduction

Extremely thermoacidophilic archaea (Topt > 70°C, pHopt < 3.5) are found in both solfataras and in the earthen mounds of heap bioleaching operations (Auernik et al., 2008). Conditions within these environments can vary widely with respect to temperature (55–90°C), pH (0–6), carbon availability (CO2 vs. organic carbon sources), nitrogen availability (inorganic vs. organic), water activity (hot springs with high activity vs. heap mounds or mud pools with low activity), and energy sources (organic vs. inorganic). Importantly, the availability of organic carbon within these environments is limited. Thus, many of these archaea fix atmospheric CO2 and derive energy from the oxidation of inorganic molecules, such as metals found in ores, which can be highly abundant in these extreme environments (Auernik and Kelly, 2010). The biooxidation of metals leads to their mobilization into a soluble form. This gives rise to an interesting dynamic in certain thermoacidophilic archaea, based on the balancing of their energy demands against the resultant toxic effects of increased local metal concentrations (Wheaton et al., 2015). On a related note, the dissolution of ores potentially leads to stressors related to transient levels of solutes affecting osmotic and chaotropic stress in these types of environments, as well as stress associated with decreased water activity (Grant, 2004; Stevenson et al., 2015).

These types of highly stressful environments lead to a plethora of stress response mechanisms related to temperature, water activity, chaotropic effects, osmolarity, and pH (Hallsworth et al., 2003; Muller et al., 2005; Ferrer et al., 2007; de Lima Alves et al., 2015); toxin-antitoxin (TA) loci have recently been examined from this perspective, with an eye toward their broader impact in the mitigation of environmental stressors. TA loci are ubiquitous in many prokaryotic genomes (Pandey and Gerdes, 2005), and consist of a toxic protein and an antitoxin, the latter of which can be RNA or protein. Under non-activating conditions, the toxin is silenced by pairing with its cognate antitoxin, but can impact the microorganism’s physiology in several ways when the antitoxin is decoupled or degraded. TA systems were first identified as assisting in plasmid maintenance via post-segregational killing (Ogura and Hiraga, 1983), as well as in phage exclusion, where activation of the toxin sacrifices some infected cells to preserve the larger population (Pecota and Wood, 1996). Subsequently, the identification of chromosomal TA systems led to a re-evaluation of their physiological significance, including their role in the stress-induced growth arrest, as well as in the stochastic formation of persister cell subpopulations, capable of subsisting through extreme stressors (Harms et al., 2016; Page and Peti, 2016). Initially, the induction of cellular arrest, as well as persister formation, was thought to be activated by specific canonical pathways, such as the second messenger (p)ppGpp or the SOS system (Germain et al., 2015; Harms et al., 2016). However, recent studies have suggested that persister cell formation may occur in the absence of Lon protease, a central component of the canonical activation pathway (Shan et al., 2015; Ramisetty et al., 2016).

Virulence-associated proteins (Vaps) are a particular class of type-II TA systems characterized by a bi-cistronic locus encoding a proteolytically labile antitoxin (VapB), typically followed by a stable ribonucleolytic toxin (VapC). These proteins were first identified in connection with virulence plasmids in human pathogens, such as Salmonella dublin (Pullinger and Lax, 1992), but have since been recognized as a predominant form of type-II toxins, particularly among the archaea (Shah, 2013). VapC toxins have been demonstrated to degrade mRNA (McKenzie et al., 2012; Sharp et al., 2012), rRNA (Winther et al., 2013) and tRNA (Winther and Gerdes, 2011; Lopes et al., 2014; Cruz et al., 2015), with the tRNAs comprising the majority of RNA targets identified (Cruz and Woychik, 2016). Some type-II TA family toxins can also target multiple RNA substrates; for example, MazF toxins can target mRNA, rRNA (Bertram and Schuster, 2014; Cruz and Woychik, 2016) and, as recently reported, tRNA (Schifano et al., 2016). Interestingly, certain MazF toxins target both mRNA and rRNA (Vesper et al., 2011; Schifano et al., 2013; Schifano et al., 2014).

Beyond their biological significance, many efforts of the past decade have elucidated the structural and functional properties of VapBCs. For instance, bioinformatics and in vivo mutational analyses have demonstrated the importance of a few acidic residues in the catalytic groove of VapC dimers that coordinate two metal ions (Arcus et al., 2011; Hamilton et al., 2014). Further, the identification of a heterooctameric structure has suggested a route to transcriptional regulation by the VapB4C4 complex, in which the complex is capable of interacting with the promoter region of the TA locus (Mate et al., 2012; Bendtsen et al., 2016). This interaction is further modulated by ratio-dependent conditional cooperativity, which is critical to both transcriptional repression (when [VapC] ≫ [VapB]) and activation (when [VapC] ≪ [VapB]) of the locus (Winther and Gerdes, 2012). In addition, crystal structures have shown conservation of antitoxin C-terminal motifs that depend on the interaction of arginine residues with the catalytic groove to inhibit toxin activity (Min et al., 2012; Bendtsen et al., 2016).

VapBC represents the most abundant TA loci family in extreme thermoacidophiles, suggesting a critical role in their physiology. For example, Sulfolobus tokodaii and Sulfolobus solfataricus have 25 and 22 VapBC TA loci, respectively (Shah, 2013). Several VapBC pairs in S. solfataricus were differentially transcribed under heat shock (Cooper et al., 2009). In vitro assays with a heat shock-responsive toxin, VapC6 from S. solfataricus, targeted mRNA transcripts encoding the antitoxin vapB6, as well as a tetR transcriptional regulator, and dppB-1, an oligo/dipeptide transport permease (Maezato et al., 2011). When the gene encoding VapC6 was deleted from the S. solfataricus genome, the archaeon was heat shock labile, suggesting a key role in thermal stress response.

Previous work with the archaea Metallosphaera sedula and Metallosphaera prunae implicated VapBC loci in stress response to hexavalent uranium. When challenged with uranium exposure, two distinct phenotypes were observed. M. sedula experienced lowered fitness and substantial increases in lag phase growth following a decrease in uranium levels, while M. prunae appeared to enter a dormant state, quickly reversed when soluble uranium levels decreased (Mukherjee et al., 2012). This dormant state appeared to be mediated by near complete degradation of total RNA collected briefly (15 minutes) after exposure to hexavalent uranium, implicating endo- and/or exo-acting ribonucleases in the cytoplasm. Transcriptomic analysis indicated that, at the 60 min time point post-shock, two vapC genes (Msed_0899 and Msed_1307) were up-regulated in M. prunae (Mukherjee et al., 2012). Since VapC toxins are endoribonucleases that could degrade single-stranded regions in ribosomal RNA subunits (Winther et al., 2013), a potential role of these, and possibly other toxins, in the M. prunae genome was suspected.

The genomes for M. sedula and M. prunae, belonging to a genus within the Sulfolobales, are nearly identical (~ 200 nt different) and encode the same twelve VapBC pairs and two solitary PIN domain proteins (with no apparent cognate VapB antitoxin) (Mukherjee et al., 2012). This raised questions as to whether VapC toxins were responsible for cellular RNA degradation in M. prunae and, if so, suggested a potential role in alleviating uranium toxicity. In a broader sense, the widespread occurrence of TA loci in prokaryotic genomes implies that many yet to be discovered roles may exist for these proteins with mechanisms leading to rapid translational arrest and recovery, improving species survival and adaptability. Here, an assessment of the VapC inventory in the M. prunae/M. sedula genome was pursued, centered on the hypothesis that TA systems play a specific, adaptive role in uranium resistance in this archaeon.

Results

Characterization of recombinant M. prunae VapC toxins/PIN-domain proteins

Recombinant versions of eleven VapC toxins and two PIN domain proteins in M. prunae were produced recombinantly in E. coli. These are identical to the VapCs encoded in the M. sedula genome, the genome sequence of which is nearly identical to the M. prunae version (Mukherjee et al., 2012). As such, the vapCs are referenced here to the corresponding M. sedula ORFs, since the M. prunae genome sequence is not yet available. Note that all but one toxin (VapC1, Msed_0338) of the twelve identifiable VapCs in M. sedula/M. prunae could be produced recombinantly in E. coli in soluble, active form. The fact that E. coli grows at a substantially lower temperature than the Metallosphaera species (37°C vs. 70°C) no doubt minimized toxin activity to the extent that the host was not impacted by the heterologous expression of the ribonucleases. Initial screening of in vitro ribonuclease activity using a fluorescently-tagged, generic RNA substrate, revealed the activity of the VapC/PIN domain proteins varied over a wide range (Figure S1). The highest activity was found for VapC7 (Msed_1214), while the lowest activity was found for PIN2 (Msed_0739).

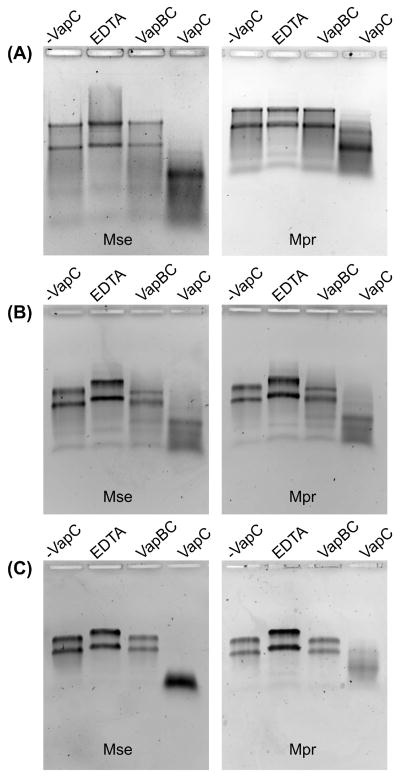

In vitro assays were performed to determine which, if any, VapCs were capable of degrading M. prunae and M. sedula total RNA. As mentioned above, M. prunae, and not M. sedula, exhibited substantial cellular RNA degradation upon ‘U(VI) shock’ (Mukherjee et al., 2012). After screening eleven VapCs and two PIN domain proteins, degradation of both M. prunae and M. sedula total RNA was observed to similar extents for only three toxins: VapC4 (Msed_0899), VapC7 (Msed_1214), VapC8 (Msed_1245) (Figure 1). The hierarchy of activity on total RNA correlated to activity against the generic RNA substrate (VapC7 > VapC8 > VapC4), despite variations in loading and reaction times (Figure S2 and Table S1). Furthermore, RNase activity of these VapCs (against the generic RNA substrate and Metallosphaera total RNA) was inhibited by addition of the cognate VapB (Figure 1, Figure S2, Table S1). Interestingly, the RNase activity of VapC8 against the generic RNA substrate was completely quenched by the non-cognate VapB4, suggesting that cross-regulation among non-cognate VapBC pairs is a possibility in vivo (Table S1). In any case, the RNase activity associated with these VapCs was not attributed to residual ribonuclease contamination from the expression host, E. coli.

Figure 1. Ribonuclease assay of VapCs found to degrade total RNA from M. sedula and M. prunae.

Total RNA harvested at mid-exponential phase from M. sedula and M. prunae treated with (A) VapC4 (Msed_0899), (B) VapC7 (Msed_1214) and (C) VapC8 (Msed_1245). Only three out of the 13 VapC toxins/PIN domain proteins were found to degrade total RNA and their activity could be quenched by the cognate VapB. Mass ratios of VapC:RNA of 1:20, 1:50, 1:50 and reactions times of 45 min, 30 min and 45 min were used for VapC4, VapC7 and VapC8, respectively. The VapC:VapB mass ratio was 1:2 for all VapCs. Key: ‘-VapC’ = No VapC added; ‘EDTA’ = 25 mM EDTA + VapC; ‘VapBC’ = VapB + VapC added; ‘VapC’ = VapC added, no EDTA, no VapB.

Two of the VapCs, VapC3 (Msed_0864) and VapC5 (Msed_0908), although highly active on the generic RNA substrate, did not degrade total Metallosphaera RNA (which is mostly rRNA) at the dilutions tested. This suggests M. prunae and M. sedula 23S and 16S rRNA does not contain VapC3/VapC5 cleavage sites or that the extensive secondary structure of the rRNA (stem loops and double stranded regions) impedes degradation. For the remaining VapCs, total RNA degradation was either not observed at all, or observed only at very high toxin: RNA ratios (1:1, 2:1) that are not likely to be physiologically relevant.

Cleavage sequence analysis of total RNA-degrading VapCs

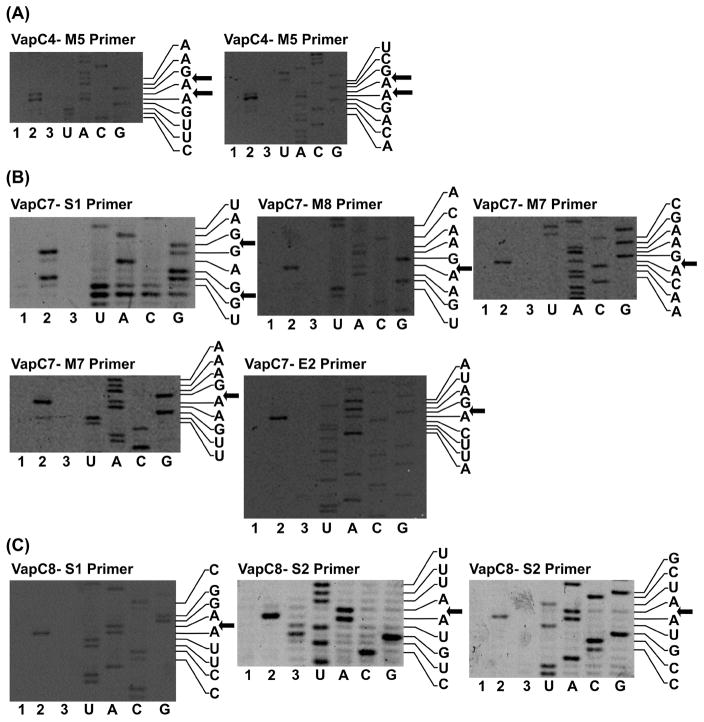

The sequence-specificities of the three VapCs that degraded total Metallosphaera RNA (and, as a consequence, rRNA) were determined by primer extension analysis, using MS2 bacteriophage RNA as substrate (see Figure 2). Alignment of the cleavage sites was used to determine consensus motifs (Table 1). VapC4 uniquely targeted a GAAG consensus motif, while VapC7 and VapC8 targeted the degenerate consensus motifs (A/U)AG(G)A and (U/G)AAU, respectively. The frequency of occurrence of the consensus sequences in Metallosphaera 23S and 16S rRNA are shown in Table 1, with many of the identified consensus motifs occurring in predicted single-stranded regions of the 16S RNA (Figure S3).

Figure 2. Cleavage sites for the VapC toxins found to degrade rRNA.

Identfied by primer extension analysis with MS2 bacteriophage RNA. (A) Cleavage sites for VapC4 (Msed_0899) found with primer M5; (B) Cleavage sites for VapC7 (Msed_1214) found with primers S1, M8, M7 and E2; (C) Cleavage sites for VapC8 (Msed_1245) found with primers S1 and S2. 1-Negative control MS2 RNA, 2-MS2 cleaved with VapC, 3-Negative control MS2 cleaved with VapC + 25 mM EDTA. Displayed sequences 5′ → 3′ top to bottom.

Table 1. Sequence-specificity of Metallosphaera rRNA degrading VapCs.

Consensus motifs were determined by aligning cleavage sites identified from primer extension using MS2 bacteriophage RNA. Sequences 5′ → 3′.

| Toxin | Alignment | # Motifs in rRNA | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||||

| 16S | 23S | |||||||||||||

| VapC4 (Msed_0899) | ||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Cleavage sites | M5 | A | A | G | ▼ | A | ▼ | A | G | U | U | |||

|

|

||||||||||||||

| M5 | U | C | G | ▼ | A | ▼ | A | G | A | C | ||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Consensus motifs | 1 | G | A | A | G | 6 | 27 | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| VapC7 (Msed_1214) | ||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Cleavage sites | S1 | C | U | A | G | ▼ | G | A | G | ▼ | G | |||

|

|

||||||||||||||

| M8 | C | A | A | G | ▼ | A | A | G | ||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||

| M7 | G | A | A | G | ▼ | A | C | A | ||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||

| M7 | A | A | A | G | ▼ | A | A | G | ||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||

| E2 | A | U | A | G | ▼ | A | C | U | ||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Consensus motifs | 1 | A | A | G | A | 4 | 9 | |||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||

| 2 | U | A | G | A | 3 | 7 | ||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||

| 3 | A | A | G | G | A | 4 | 4 | |||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||

| 4 | U | A | G | G | A | 1 | 1 | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| VapC8 (Msed_1245) | ||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Cleavage sites | S1 | C | G | G | A | ▼ | A | U | U | C | ||||

|

|

||||||||||||||

| S2 | U | U | U | A | ▼ | A | U | G | U | |||||

|

|

||||||||||||||

| S2 | G | C | U | A | ▼ | A | U | G | C | |||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Consensus motifs | 1 | U | A | A | U | 3 | 4 | |||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||

| 2 | G | A | A | U | 7 | 9 | ||||||||

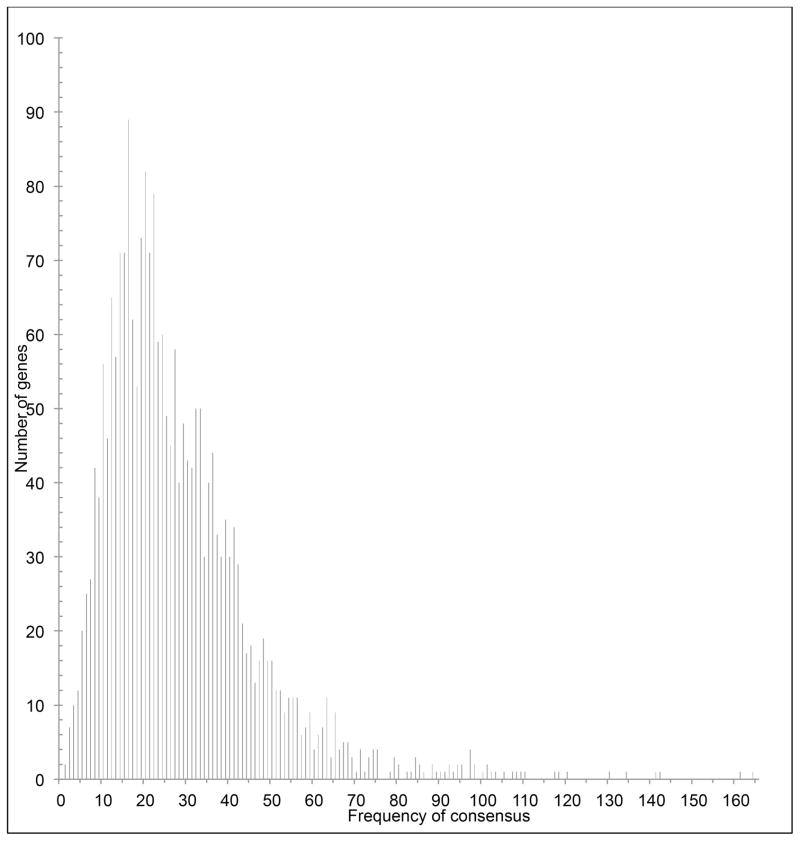

Given that the above identified cleavage sites are likely also to occur in single-stranded regions of mRNA, bioinformatic analysis of primary sequence was performed for all of the genes annotated in the M. sedula/M. prunae genomes. The number of cleavage recognition sites within a transcript and its susceptibility to degradation have been correlated in previous studies (Rothenbacher et al., 2012). Thus, the presence and frequency of these consensus motifs, within a transcript, relates to the likelihood of a specific transcript being a VapC target in M. sedula/M. prunae (Table S2). Distribution analysis of the number of mRNA targets, based on the total of all seven consensus motifs, shown in Figure 3, revealed that most genes encoded in the M. prunae/M. sedula genomes contain at least one consensus motif, although cleavage motifs for certain ORFs were very highly represented.

Figure 3. Distribution analysis of mRNA targets.

All seven consensus motifs identified by primer extension analyses (Table 1) were utilized to search over the M. prunae/M. sedula genomes to determine the distribution of genes as a function of consensus motif frequency. See Table S6 for the complete list of genes and occurance of consensus motifs.

Toxin-specific cleavage site analysis

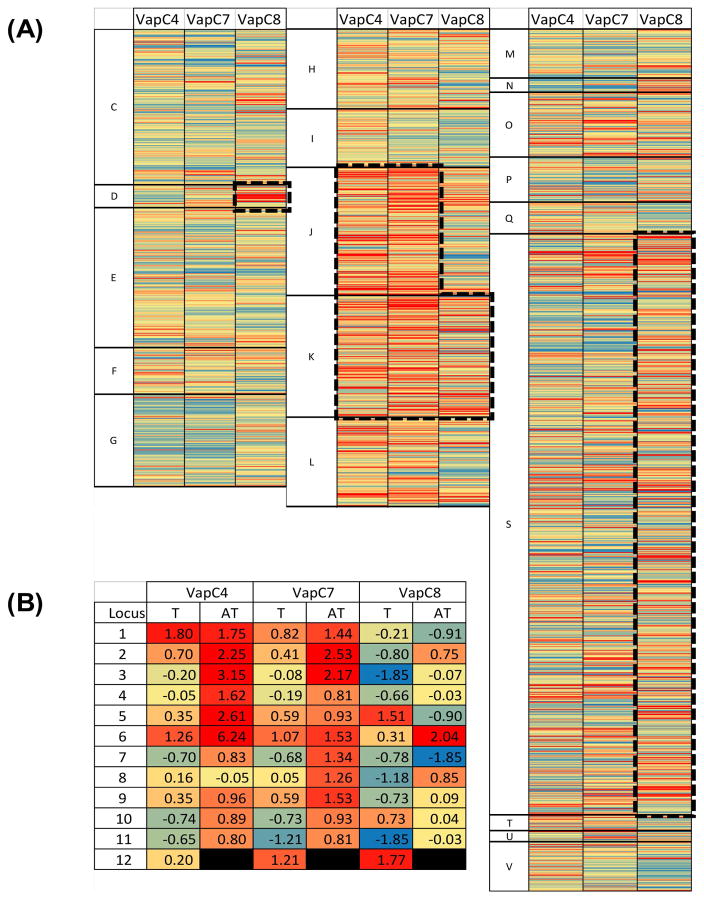

Next, the possible role of individual toxins in regulating key cellular processes through mRNA targeting was examined. In this case, the number of cleavage motifs normalized to the transcript length was calculated for each gene with each consensus sequence (Table S2). For each toxin, a profile was determined based on the z-score (value > 2) from each of the three data sets. Although this analysis should identify the top 2.3% of target sequences within the genome (for a normal distribution), all of the sets are overrepresented by roughly 1.3–1.6%. This result was expected, given the working hypothesis that VapCs have evolved to target particular sequences of RNA. Thus, targeted transcripts should have an abundance of a particular sequence that appears much less frequently in non-targets. In fact, the large number of genes with z-scores higher than 3 (i.e., 35, 24, and 28 for VapC4, VapC7, and VapC8, respectively), supports the significance of the consensus sequences. This result is supported by the distribution shown in Figure 3, where the comparison of cleavage sites per gene length to frequency shows a definite right skew. Interestingly, the examination of clustered orthologous groups (COGs) showed that each of the toxins primarily targets particular cellular functions (Figure 4A). To examine this further, a hypergeometric distribution was utilized to calculate the probability of a group of genes belonging to a single COG appearing within a target list, assuming random sampling of genes from each of the COGs present in the genome (Table 2). This analysis suggests that VapC4 and VapC7 primarily target (P < 0.01) transcripts associated with translation (J) and transcription (K), while VapC8 targets a small, but significant, fraction of cell cycle/division (D) transcripts, as well as some related to transcription (K).

Figure 4. Heat plot visualization of VapC4, C7, and C8 targeting of the whole transcriptome.

(A) For each VapC (4, 7, and 8), the number of cut sites per bp and resulting z-score were calculated for each gene in the transcriptome. The color scale is a gradient from blue (low z-score) to red (high z-score). (A) whole transcriptome: Genes are arranged based on their COG grouping and ordered based on locus ID. (B) VapBC loci.

Table 2.

Probability of COG gene distribution in top VapC4, C7, and C8 targets.

| VapC4 | VapC7 | VapC8 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| C: Energy Production and Modification | 1.0E+00 | 1.0E+00 | 9.5E-01 |

| D: Cell Cycle Control, Cell Division, Chromosome Partitioning | 1.0E+00 | 1.0E+00 | 7.4E-05 |

| E: Amino Acid Transport and Metabolism | 1.0E+00 | 1.0E+00 | 9.9E-01 |

| F: Nucleotide Transport and Metabolism | 1.0E+00 | 8.8E-01 | 1.0E+00 |

| G: Carbohydrate Transport and Metabolism | 9.9E-01 | 1.0E+00 | 1.0E+00 |

| H: Coenzyme Transport and Metabolism | 9.8E-01 | 9.7E-01 | 9.1E-01 |

| I: Lipid Transport and Metabolism | 1.0E+00 | 1.0E+00 | 1.0E+00 |

| J: Translation, Ribosomal Structure and Biogenesis | 2.9E-07 | 5.4E-06 | 6.0E-01 |

| K: Transcription | 1.7E-03 | 2.6E-06 | 4.8E-03 |

| L: Replication, Recombination, and Repair | 6.4E-02 | 5.6E-01 | 9.4E-01 |

| M: Cell Wall/Membrane/Envelope Biogenesis | 1.0E+00 | 8.9E-01 | 9.1E-01 |

| N: Cell Motility | 1.0E+00 | 1.0E+00 | 5.1E-01 |

| O: Posttranslational Modification, Protein Turnover, Chaperones | 6.2E-01 | 5.5E-01 | 8.3E-01 |

| P: Inorganic Ion Transport and Metabolism | 8.9E-01 | 8.7E-01 | 8.9E-01 |

| Q: Secondary Metabolites Biosynthesis, Transport, and Catabolism | 7.9E-01 | 1.0E+00 | 1.0E+00 |

| S: Function Unknown | 1.5E-01 | 1.7E-01 | 5.5E-04 |

| T: Signal Transduction Mechanism | 5.4E-01 | 1.0E+00 | 5.4E-01 |

| U: Intracellular Trafficking, Secretion, and Vesicular Transport | 4.2E-01 | 3.9E-01 | 1.0E+00 |

| V: Defense Mechanisms | 9.1E-01 | 1.0E+00 | 7.0E-01 |

For VapC4, there are ten 30S ribosome subunit targets and nine 50S subunit targets. Additionally, nine putative transcriptional regulators and an RNA polymerase subunit appear as top targets. This result suggests that VapC4 can effectively disrupt translation as well as regulate future transcription events via the targeting of numerous regulator proteins. Similarly, VapC7 appears to target numerous ribosomal subunits from the 30S and 50S complexes (six and nine, respectively), while also targeting twelve transcriptional regulators. In contrast, the VapC8 top targets include only four ribosomal subunits, but also seven proteins associated with cellular division, all containing ParA-like domains, which are associated with chromosomal partitioning. In addition, two RNA polymerase subunits appear in VapC8’s top target list, as well as six transcriptional regulators.

It was interesting to note that some of the hypothetical proteins identified as targets, as well as a few transcriptional regulators, belong to the list of antitoxin proteins identified in the genome of the two organisms. Furthermore, an examination of the VapBC loci in the two organisms suggests that VapBs may be a preferred target of VapCs (Figure 4B). Further examination also suggests that VapCs are not strongly targeted by other VapCs (with few exceptions). Examining potential self-targeting of the toxins, for each toxin, its transcript appears in the bottom (z-score < 0) of targets, while the antitoxin transcript is well above mean (z-score > 0) of its targets. Also, VapC4 and VapC7 appear to target antitoxin transcripts, while avoiding toxin transcripts. Overall, this implies that Vap loci are linked by a complex system of post-transcriptional regulation; this ultimately leads to a dormancy response in the case of M. prunae exposed to soluble uranium.

In vitro transcript cleavage

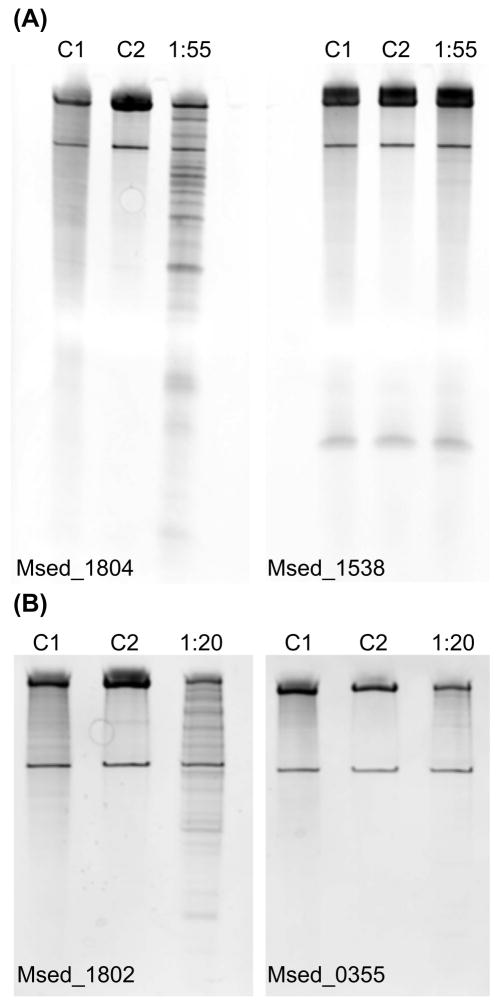

To confirm target mRNA predictions, a target and non-target pair with comparable nucleotide length were selected for further analysis (see Figure 5A). Msed_1804 (target) and Msed_1538 (non-target) were subjected to VapC4 (Msed_0899) degradation. The treatment resulted in Msed_1804 being significantly degraded while Msed_1538 remained intact (Figure 5A). The molar ratio of VapC:mRNA was found to be an important variable, which may reflect in vivo conditions. In support of frequency/availability of cleavage sites being correlated to sensitivity, VapC4 degraded Msed_1804 (25 cleavage sites), while negligible degradation of Msed_0355 (3 cleavage sites) was observed (Figure 5B). Many of the identified consensus motifs occurred in predicted single stranded regions of Msed_1804 (Figure S4), Msed_1802 (Figure S5) and Msed_0355 (Figure S6).

Figure 5. Msed_0899 (VapC4) treatment of the target/non-target pair Msed_1804/1538 and target/target pair Msed_1802/0355.

(A) Msed_1804/1538 (B) Msed_1802/0355. Msed_1804, Msed_1802 and Msed_0355 contained 7, 25 and 3 GAAG motifs, respectively. Msed_1538 contained no identified motifs. For Msed_1804/1538 a molar ratio (VapC:mRNA) of 1:55 was used. For Msed_1802/0355 a molar ratio (VapC:mRNA) of 1:20 was used. C1 is the reaction completed in the absence of VapC. C2 is the reaction completed using VapC with 25 mM EDTA added.

Discussion

Previously, ‘U(VI) shock’ experiments performed with M. prunae showed substantial degradation of cellular RNA within 15 min; cellular RNA was restored by 60 min as the uranium concentration in the media dropped due to complexation of U(VI) with growth medium components (Mukherjee et al., 2012). This was not the case for M. sedula. The reason for the complete degradation of cellular rRNA in M. prunae may correlate with certain mutations in its genome that were not found in M. sedula. The M. prunae genome, which is nearly identical to M. sedula’s (Mukherjee et al., 2012), has single point mutations in Msed_1722 (ribonucleoprotein complex aNOP56) and 23S rRNA. The mutations and heightened cellular ribonuclease activity could make M. prunae rRNA more vulnerable to attack by VapC toxins compared to M. sedula (Mukherjee et al., 2012). However, as shown in Figure 1, overall in vitro degradation patterns for rRNA from the two ‘species’ were comparable.

In order to examine the functionality and cellular targets of VapC toxins and PIN domain proteins in the M. prunae/M. sedula genomes (no mutations were found in the genes encoding for toxins and antitoxins in M. prunae), these proteins were examined with respect to ribonuclease activity and specificity. The ribonuclease activity, on a generic substrate, varied widely across the VapC and PIN domain proteins. Three of the VapC toxins (VapC4, VapC7, VapC8) were found to degrade M. prunae/M. sedula total RNA and their identified consensus cleavage motifs mapped to specific regions of 16S and 23S rRNA (Table 1). Furthermore, these consensus motifs were prevalent throughout the genome, suggesting that they could degrade mRNA targets. This is consistent with reports that certain type II toxins (MazF) target both rRNA and mRNA. For example, MazF-mt6 from M. tuberculosis not only cleaves mRNA, but also 23S rRNA at the ribosomal A site (UU↓CCU) (Schifano et al., 2013). E. coli MazF cleaves single-stranded mRNAs at ACA sequences and also targets 16S rRNA (Vesper et al., 2011). Other work has shown that VapCs can degrade mRNA (McKenzie et al., 2012; Sharp et al., 2012). The observation that VapC4 targets both rRNA and mRNA in vitro indicates that certain VapC toxins, like MazF toxins, exhibit dual RNA substrate activity (Vesper et al., 2011; Schifano et al., 2013).

Interestingly, the putative target transcripts in M. prunae/M. sedula of the total RNA-degrading VapCs were primarily related to transcription, translation, and cell cycle/division. This indicates that under certain stressors (e.g., hexavalent uranium) many key cellular processes could be modulated or stalled following VapC activation. Furthermore, the type of disruption identified by the top targets of each toxin suggests a toxin-specific route to a dormant state. Specifically, VapC4 and VapC7 appear to induce cellular arrest through the cessation of translation and transcription. In contrast, VapC8 appears to cellular division processes. Overall, all three toxins target total cellular RNA (mRNA, tRNA and rRNA), suggesting multiple contributing routes to dormancy.

It seems that activation of a single TA locus is insufficient to trigger and orchestrate the complex process of stress response. The targeting of VapB transcripts by VapC toxins (see Figure 4B) may initiate a complex cascade of toxin activation events, thereby driving specific stress response mechanisms - in the case of M. prunae, cellular dormancy. Why a similar reaction to U(VI) challenge is not observed for the very closely related M. sedula is not clear, but determining the bases for these different responses could help elucidate how stress triggers toxin activation.

Whether TA loci play a significant survival role in environmental biotopes remains to be seen. However, early hypotheses proposed this possibility (Pandey and Gerdes, 2005). While VapBC TA loci are abundant in genomes of the extremely thermoacidophilic archaea, to date they had only been implicated in heat shock (Maezato et al., 2011). The possibility that these loci may also play a role in other kinds of stress survival for these archaea seems likely, given the results presented here.

Experimental Procedures

Bacterial strains and culture conditions

Escherichia coli NovaBlue GigaSingles™ (EMD Millipore) competent cells were used as the cloning host and E. coli Rosetta™ 2(DE3) Singles™ (EMD Millipore) was used as the expression host. The E. coli strains were cultivated in Luria-Bertani (LB) media (10 g/L casein peptone, 5 g/L yeast extract, 10 g/L sodium chloride) in the presence of either kanamycin (50 μg/ mL) or ampicillin/carbenicillin (50 μg/mL) for pRSF and pET46 Ek/LIC cloning vectors (Novagen, Madison, WI), respectively. Additionally, chloramphenicol (34 μg/mL) was added to cultures of E. coli Rosetta (DE3). The cultures were grown in 5 mL Falcon tubes or 1 L Erlenmeyer flasks at 37°C and agitated at 250 rpm.

Cloning, expression and purification of VapCs, PIN domain proteins and VapBs

VapC and PIN domain encoding genes were cloned into pRSF or pET46 Ek/LIC vector using the pET-46 Ek/LIC Vector Kit (Novagen). VapB genes were cloned into the pET46 Ek/LIC vector using one-step isothermal assembly of overlapping dsDNA, as described previously (Gibson, 2011). In either case, a stop codon was included to prevent inclusion of a C-terminal vector-encoded S-Tag in the final protein product. Oligonucleotides used for cloning of VapC/PIN domain and VapB genes are presented in Tables S7 and S8. Genomic DNA was isolated from Metallosphaera species by methods described previously (Geslin et al., 2003), and PCR products were generated by following established molecular biology techniques (Sambrook J, 1989). Assembled vectors were transformed into E. coli NovaBlue GigaSingles™ (EMD Millipore) competent cells by heat shock. Recovered cells were cultured overnight on LB plates with 1.5% (w/w) agar supplemented with either ampicillin/carbenicillin or kanamycin. Single colonies were picked from the plates and used as inoculum for 5 mL LB broth, also supplemented with appropriate antibiotics, which were grown overnight for plasmid extraction. Plasmid miniprep was done using QIAprep Spin Miniprep Kit (Qiagen) and the presence/sequence of the insert was confirmed by sequencing (Eton Bioscience Inc. (Durham NC) or Genewiz Inc. (Research Triangle Park NC)). Plasmids were transformed into E. coli Rosetta™ 2(DE3) Singles™ (EMD Millipore) by heat shock and plated on LB-agar plates supplemented with kanamycin or ampicillin/carbenicillin and chloramphenicol. Single colonies were picked from the plates and grown overnight in LB broth to serve as inoculum for large-scale (1 L) protein expression. Expression cultures were started with a 1% (v/v) inoculum and were induced by addition of isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (ITPG) (1 mM) at an OD600 of 0.7–0.8. The induction was allowed to continue for 4 hours and cultures were harvested by centrifugation.

Buffers and water used for protein purification were treated with diethylpyrocarbonate (DEPC) to remove ribonucleases. The cell pellets were re-suspended in 30 mL of Buffer A for IMAC affinity chromatography (50 mM sodium phosphate, 300 mM sodium chloride, 10 mM imidazole at pH 7.4). The cells were lysed using a French Pressure Cell (SLM-AMINCO) at a pressure of 16,000 psi. Cell lysate was incubated at 65°C for 20 min as a purification step to precipitate background E. coli proteins. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 25,000 x g for 25 min. The supernatant was collected and sterile filtered. Protein purification was performed on a Biologic LP system using a HisTrap HP 5 mL column (GE). Equilibration and protein binding steps were performed with Buffer A (mentioned above) and the protein of interest was eluted off the column by applying a linear gradient (0–100%) of Buffer B (50 mM sodium phosphate, 300 mM sodium chloride, 500 mM imidazole at pH 7.4). The FPLC fractions were checked for presence of protein by loading samples on a 4–12% SDS-PAGE gel (Invitrogen) and appropriate fractions were pooled together. The protein samples were concentrated using 3,500 MWCO filters (Amicon) and dialyzed into RNase activity buffer (10 mM MgCl2, 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl at pH 6.0).

Two VapC toxins (Msed_0411 and Msed_0338) and 1 PIN-domain containing protein (Msed_0302) were found to form inclusion bodies. These proteins were solubilized from the cell pellet using 50 mM CAPS, pH 11.0 and 0.3% (v/v) N-lauroylsarcosine and re-folded using 4 dialysis steps in 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0 (Protein Re-folding Kit, Novagen). Protein purification was performed using HisTrap HP 5 mL column (GE). In order to avoid issues of protein precipitation, equilibration was done using 20 mM Tris-HCl, 10 mM imidazole at pH 8.0 and eluted with 20 mM Tris-HCl, 500 mM imidazole at pH 8.0.

Ribonuclease assay with fluorescently-tagged RNA substrate

Initial screening of VapC toxins and PIN domain proteins for their respective RNase activities was done using a fluorescently-tagged substrate (IDT DNA RNase Alert substrate). Protein concentration was determined using ThermoScientific BCA Protein assay kit (BCA – bicinchoninic acid). Three different dilutions were used for each sample and three technical replicates were done for each dilution for protein quantification. The reactions were performed in 0.2 mL PCR tubes by mixing 10 μl 10X RNase Alert Buffer (IDT DNA), 10 μl 100 mM MgCl2, 1 μg of purified protein and balance RNase free water (up to 90 μl). The amount of protein was modified, depending on the fluorescence readings, with lower quantities (0.1, 0.01 and 0.001 μg) used for more active toxins. This mix was incubated at 70°C for 5 min to activate the toxins, following which 10 μl (20 pmoles) of RNA substrate was added. The reactions were done in triplicate for each sample and added to an opaque 96 well plate (pre-heated to 50°C) for fluorescence measurements. The fluorescence measurements were done at 50°C with a BioTek plate reader with excitation and emission wavelength of 490 and 520 nm, respectively; readings were taken at 1 min intervals for 60 min. A ‘no protein added’ control was included in the initial screening for all VapCs and PIN domain proteins. For rRNA degrading VapCs (Msed_0899-VapC4, Msed_1214-VapC7 and Msed_1245-VapC8), additional controls were added including 25 mM EDTA and cognate VapB, with the VapC:VapB mass ratio set at 1:2. RNase activity was calculated by measuring the slope of the linear region of the curve (between 15 to 30 min following initiation of the reaction), for three replicates and normalizing for protein concentration. The no protein added control fluorescence was subtracted prior to determination of initial reaction velocity.

Total RNA degradation assays

Total RNA, mostly composed of rRNA, was isolated from exponentially growing cells of M. sedula and M. prunae using a Trizol extraction method, as described previously (Auernik and Kelly, 2008). The VapC toxins and PIN domain proteins were initially screened to select candidates responsible for rRNA degradation. Reaction conditions for rRNA-degrading VapCs (Msed_0899-VapC4, Msed_1214-VapC7 and Msed_1245-VapC8) were optimized and controls, including no protein added, 25 mM EDTA and cognate VapB were included. The VapC:VapB mass ratio was set at 1:2. Activity assays were performed by treating 2 μg of total RNA from each species with a VapC:RNA mass ratio of 1:20, for VapC4 and 1:50 for VapC7 and VapC8. The VapCs were activated by pre-heating in reaction buffer (50 mM Trish-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 250 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, pH 6.0) at 70°C for 5 min, following which RNA was added to the mix. The reactions were allowed to proceed at 65°C for 30 min (VapC7) or 45 min (VapC4 and VapC8). The reaction was stopped by addition of formaldehyde loading buffer and incubation at 65°C for 15 min. For VapC4, higher protein loadings required the reactions be processed via ethanol precipitation. The VapC4 reaction was stopped by adding an equal volume of Trizol Reagent (Life Technologies), followed by 50 μl of chloroform (Fisher Scientific). The aqueous layer was separated from the organic layer by centrifugation at 12,000 x g for 15 min. Sodium acetate (final concentration 0.3 M) was added to the aqueous layer and RNA was precipitated by adding ice cold 100% ethanol (Sigma Aldrich). The RNA was pelleted by centrifuged at 14,000 x g for 5 min. The RNA pellet was washed with 70% ethanol and pelleted by centrifugation at 14,000 x g for 5 min. The RNA was re-suspended in 15–20 μl of RNase-free water. RNA (1 μg) was run on a 1% agarose gel under denaturing conditions and visualized by post-staining with GelRed™ (Biotium).

Primer extension analyses for rRNA-degrading VapCs

MS2 bacteriophage RNA (Roche) was used as the template for primer extension analysis after cleavage by VapC toxins. This analysis was performed for the three VapCs capable of degrading Metallosphaera species rRNA (Msed_0899-VapC4, Msed_1214-VapC7 and Msed_1245-VapC8). MS2 RNA (0.8 μg) was treated with different concentrations of each VapC (0.08 μg, 0.16 μg, 0.4 μg 0.8 μg) to determine an appropriate VapC:RNA ratio in the reaction. The VapC was preheated in reaction buffer (50 mM Trish-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 250 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, pH 6.0) at 70°C for 2 min, after which MS2 RNA and 0.5 μl of RNase Inhibitor (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) were added. The reaction was allowed to proceed for 5 min. The reaction was stopped by the addition of an equal volume Trizol Reagent (Life Technologies) and purified, as described above, for VapC4 treatment of total RNA. RNA (1 μg) was separated on a 1% agarose gel under denaturing conditions and visualized by post-staining with GelRed™ (Biotium).

Primers used in this study (See Table S9), adapted from previous literature reports (Zhu et al., 2008), were synthesized with a 5′-labeled cy5 dye. Primer extension analyses were performed with 300 ng MS2 cleaved RNA, 1 pmol of primer, 2 mM dNTP mix (Donegan et al., 2010) (Roche Indianapolis, IN), and 2 U of Avian Myeloblastosis Virus (AMV) reverse transcriptase (NEB Ipswich MA) in AMV reaction buffer. Sequencing ladders were generated with 800 ng of MS2 RNA, 6 pmol of primer, 2 U of AMV RT, 4 mM dNTP mix and 2 mM ddNTPs (Roche Indianapolis,IN). Reverse transcription was allowed to proceed at 47°C for 1 h for the cleaved RNA and for 30 min for the sequencing ladders. The reactions were stopped by adding stop solution (95% formamide, 20 mM EDTA and 0.05% bromophenol blue), and denatured at 95°C for 5 min, before loading on a 6% polyacrylamide gel (Acrylamide mix, 8 M Urea and 1X TBE). The gel was run at 80W for 1 h in OWL-S3S Aluminum-backed sequencer (ThermoScientific, Waltham, MA) and the image was obtained using STORM scanner.

Messenger RNA (mRNA) degradation assays

Primers, including the T7 promoter, (Table S10) were used to amplify Msed_0355, Msed_1538, Msed_1802 and Msed_1804 from M. sedula genomic DNA using Phusion® High-Fidelity DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs), following the manufacturer’s instructions. PCR products were purified using a QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen) and examined on an agarose gel to confirm amplicon sizes. RNA was transcribed using the HiScribe™ T7 High Yield RNA Synthesis Kit (New England Biolabs) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Transcribed RNA was purified by sodium acetate and ethanol precipitation and re-suspended in nuclease-free water. RNA concentrations were quantified using an Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 (Genomic Sciences Lab, NCSU). Purified RNA (3.2 μg) was treated at the indicated VapC:RNA molar ratio. The reactions (10μL total volume) were performed in 0.2 mL PCR tubes. The VapC was preheated in reaction buffer (50 mM Trish-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 250 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, pH 6.0) at 70°C for 2 min, after which the RNA (3.2 μg) and 0.5 μl of RNase Inhibitor (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) were added. The reaction was allowed to proceed at 65°C for 15 min. The reaction was stopped by addition of TBE Urea Sample Buffer (Invitrogen) and heat treatment at 65°C for 15 min. Controls included-VapC as well as VapC with 25 mM EDTA added. RNA (1 μg) was run on a denaturing polyacrylamide gel (Novex ® TBE-Urea 10%, Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s instructions and was visualized by post-staining with GelRed™ (Biotium).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the US Defense Threat Reduction Agency (DTRA) (HDTR-09-0300), the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) (RO1 GM090209-01), the US Air Force Office of Sponsored Research (AFOSR) (FA9550-13-1-0236). GHW acknowledges support by a US Department of Education (DoEd) GAANN Fellowship (DoEd P200A070582-09). JAC acknowledges support from a NIH T32 Biotechnology Traineeship (GM008776-16). The authors thank Dr. Scott McCullough, Department of Biological Sciences, NCSU, for helpful advice and for access to imaging equipment in his laboratory. Thanks also to Dr. Chase Beisel, Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, NCSU, for helpful advice on RNA assays and structural modeling. The authors declare no conflicts of interest apply to this manuscript.

References

- Arcus VL, McKenzie JL, Robson J, Cook GM. The PIN-domain ribonucleases and the prokaryotic VapBC toxin-antitoxin array. Protein Engineering Design & Selection. 2011;24:33–40. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzq081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auernik KS, Kelly RM. Identification of components of electron transport chains in the extremely thermoacidophilic crenarchaeon Metallosphaera sedula through iron and sulfur compound oxidation transcriptomes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74:7723–7732. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01545-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auernik KS, Kelly RM. Impact of molecular hydrogen on chalcopyrite bioleaching by the extremely thermoacidophilic archaeon Metallosphaera sedula. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76:2668–2672. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02016-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auernik KS, Cooper CR, Kelly RM. Life in hot acid: pathway analyses in extremely thermoacidophilic archaea. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2008;19:445–453. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2008.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendtsen KL, Xu K, Luckmann M, Winther KS, Shah SA, Pedersen CN, Brodersen DE. Toxin inhibition in C. crescentus VapBC1 is mediated by a flexible pseudo-palindromic protein motif and modulated by DNA binding. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016:gkw1266. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertram R, Schuster CF. Post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression in bacterial pathogens by toxin-antitoxin systems. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2014:4. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2014.00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper CR, Daugherty AJ, Tachdjian S, Blum PH, Kelly RM. Role of vapBC toxin-antitoxin loci in the thermal stress response of Sulfolobus solfataricus. Biochem Soc Trans. 2009;37:123–126. doi: 10.1042/BST0370123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz JW, Woychik NA. tRNAs taking charge. Pathog Dis. 2016;74:117. doi: 10.1093/femspd/ftv117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz JW, Sharp JD, Hoffer ED, Maehigashi T, Vvedenskaya IO, Konkimalla A, et al. Growth-regulating Mycobacterium tuberculosis VapC-mt4 toxin is an isoacceptor-specific tRNase. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7480. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lima Alves F, Stevenson A, Baxter E, Gillion JL, Hejazi F, Hayes S, et al. Concomitant osmotic and chaotropicity-induced stresses in Aspergillus wentii: compatible solutes determine the biotic window. Curr Genet. 2015;61:457–477. doi: 10.1007/s00294-015-0496-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donegan NP, Thompson ET, Fu Z, Cheung AL. Proteolytic regulation of toxin-antitoxin systems by ClpPC in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 2010;192:1416–1422. doi: 10.1128/JB.00233-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer M, Golyshina OV, Beloqui A, Golyshin PN, Timmis KN. The cellular machinery of Ferroplasma acidiphilum is iron-protein-dominated. Nature. 2007;445:91–94. doi: 10.1038/nature05362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germain E, Roghanian M, Gerdes K, Maisonneuve E. Stochastic induction of persister cells by HipA through (p)ppGpp-mediated activation of mRNA endonucleases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:5171–5176. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1423536112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Geslin C, Le Romancer M, Erauso G, Gaillard M, Perrot G, Prieur D. PAV1, the first virus-like particle isolated from a hyperthermophilic euryarchaeote, “Pyrococcus abyssi”. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:3888–3894. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.13.3888-3894.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson DG. Enzymatic assembly of overlapping DNA fragments. Methods Enzymol. 2011;498:349–361. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-385120-8.00015-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant WD. Life at low water activity. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2004;359:1249–1266. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2004.1502. discussion 1266–1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallsworth JE, Heim S, Timmis KN. Chaotropic solutes cause water stress in Pseudomonas putida. Environ Microbiol. 2003;5:1270–1280. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2003.00478.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton B, Manzella A, Schmidt K, DiMarco V, Butler JS. Analysis of non-typeable Haemophilous influenzae VapC1 mutations reveals structural features required for toxicity and flexibility in the active site. PLOS One. 2014;9:e112921. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harms A, Maisonneuve E, Gerdes K. Mechanisms of bacterial persistence during stress and antibiotic exposure. Science. 2016;354:aaf4268. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf4268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopes AP, Lopes LM, Fraga TR, Chura-Chambi RM, Sanson AL, Cheng E, et al. VapC from the leptospiral VapBC toxin-antitoxin module displays ribonuclease activity on the initiator tRNA. PLoS One. 2014;9:e101678. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0101678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maezato Y, Daugherty A, Dana K, Soo E, Cooper C, Tachdjian S, et al. VapC6, a ribonucleolytic toxin regulates thermophilicity in the crenarchaeote Sulfolobus solfataricus. RNA. 2011;17:1381–1392. doi: 10.1261/rna.2679911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mate MJ, Vincentelli R, Foos N, Raoult D, Cambillau C, Ortiz-Lombardia M. Crystal structure of the DNA-bound VapBC2 antitoxin/toxin pair from Rickettsia felis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:3245–3258. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie JL, Robson J, Berney M, Smith TC, Ruthe A, Gardner PP, et al. A VapBC toxin-antitoxin module is a posttranscriptional regulator of metabolic flux in mycobacteria. J Bacteriol. 2012;194:2189–2204. doi: 10.1128/JB.06790-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min AB, Miallau L, Sawaya MR, Habel J, Cascio D, Eisenberg D. The crystal structure of the Rv0301-Rv0300 VapBC-3 toxin-antitoxin complex from M. tuberculosis reveals a Mg2+ ion in the active site and a putative RNA-binding site. Protein Science. 2012;21:1754–1767. doi: 10.1002/pro.2161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee A, Wheaton GH, Blum PH, Kelly RM. Uranium extremophily is an adaptive, rather than intrinsic, feature for extremely thermoacidophilic Metallosphaera species. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:16702–16707. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1210904109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller V, Spanheimer R, Santos H. Stress response by solute accumulation in archaea. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2005;8:729–736. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2005.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogura T, Hiraga S. Mini-F plasmid genes that couple host cell division to plasmid proliferation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1983;80:4784–4788. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.15.4784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page R, Peti W. Toxin-antitoxin systems in bacterial growth arrest and persistence. Nat Chem Biol. 2016;12:208–214. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey DP, Gerdes K. Toxin-antitoxin loci are highly abundant in free-living but lost from host-associated prokaryotes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:966–976. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pecota DC, Wood TK. Exclusion of T4 phage by the hok/sok killer locus from plasmid R1. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2044–2050. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.7.2044-2050.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pullinger GD, Lax AJ. A Salmonella dublin virulence plasmid locus that affects bacterial-growth under nutrient-limited conditions. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:1631–1643. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb00888.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramisetty BC, Ghosh D, Roy Chowdhury M, Santhosh RS. What is the link between stringent response, endoribonuclease encoding type ii toxin-antitoxin systems and persistence? Front Microbiol. 2016;7:1882. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothenbacher FP, Suzuki M, Hurley JM, Montville TJ, Kirn TJ, Ouyang M, Woychik NA. Clostridium difficile MazF toxin exhibits selective, not global, mRNA cleavage. J Bacteriol. 2012;194:3464–3474. doi: 10.1128/JB.00217-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook JFE, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Schifano JM, Vvedenskaya IO, Knoblauch JG, Ouyang M, Nickels BE, Woychik NA. An RNA-seq method for defining endoribonuclease cleavage specificity identifies dual rRNA substrates for toxin MazF-mt3. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3538. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schifano JM, Edifor R, Sharp JD, Ouyang M, Konkimalla A, Husson RN, Woychik NA. Mycobacterial toxin MazF-mt6 inhibits translation through cleavage of 23S rRNA at the ribosomal A site. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:8501–8506. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1222031110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schifano JM, Cruz JW, Vvedenskaya IO, Edifor R, Ouyang M, Husson RN, et al. tRNA is a new target for cleavage by a MazF toxin. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:1256–1270. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah SAG, RA . In: Prokaryotic Toxins-Antitoxins. Gerdes K, editor. Springer-Verlag; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Shan Y, Lazinski D, Rowe S, Camilli A, Lewis K. Genetic basis of persister tolerance to aminoglycosides in Escherichia coli. MBio. 2015:6. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00078-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp JD, Cruz JW, Raman S, Inouye M, Husson RN, Woychik NA. Growth and translation inhibition through sequence-specific RNA binding by Mycobacterium tuberculosis VapC toxin. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:12835–12847. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.340109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson A, Cray JA, Williams JP, Santos R, Sahay R, Neuenkirchen N, et al. Is there a common water-activity limit for the three domains of life? ISME J. 2015;9:1333–1351. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2014.219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vesper O, Amitai S, Belitsky M, Byrgazov K, Kaberdina AC, Engelberg-Kulka H, Moll I. Selective translation of leaderless mRNAs by specialized ribosomes generated by MazF in Escherichia coli. Cell. 2011;147:147–157. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheaton G, Counts J, Mukherjee A, Kruh J, Kelly R. The confluence of heavy metal biooxidation and heavy metal resistance: implications for bioleaching by extreme thermoacidophiles. Minerals. 2015;5:397–451. [Google Scholar]

- Winther KS, Gerdes K. Enteric virulence associated protein VapC inhibits translation by cleavage of initiator tRNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:7403–7407. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019587108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winther KS, Gerdes K. Regulation of enteric vapBC transcription: induction by VapC toxin dimer-breaking. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:4347–4357. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winther KS, Brodersen DE, Brown AK, Gerdes K. VapC20 of Mycobacterium tuberculosis cleaves the Sarcin-Ricin loop of 23S rRNA. Nature Commun. 2013:4. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J, Ji Z, Wang J, Sun R, Zhang X, Gao Y, et al. Tumor-inhibitory effect and immunomodulatory activity of fullerol C60(OH)x. Small. 2008;4:1168–1175. doi: 10.1002/smll.200701219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.