Abstract

Anesthesia and surgery have an impact on inflammatory responses, which influences perioperative homeostasis. Inhalational and intravenous anesthesia can alter immune-system homeostasis through multiple processes that include activation of immune cells (such as monocytes, neutrophils, and specific tissue macrophages) with release of pro- or anti-inflammatory interleukins, upregulation of cell adhesion molecules, and overproduction of oxidative radicals. The response depends on the timing of anesthesia, anesthetic agents used, and mechanisms involved in the development of inflammation or immunosuppression. Obese patients are at increased risk for chronic diseases and may have the metabolic syndrome, which features insulin resistance and chronic low-grade inflammation. Evidence has shown that obesity has adverse impacts on surgical outcome, and that immune cells play an important role in this process. Understanding the effects of anesthetics on immune-system cells in obese patients is important to support proper selection of anesthetic agents, which may affect postoperative outcomes. This review article aims to integrate current knowledge regarding the effects of commonly used anesthetic agents on the lungs and immune response with the underlying immunology of obesity. Additionally, it identifies knowledge gaps for future research to guide optimal selection of anesthetic agents for obese patients from an immunomodulatory standpoint.

Keywords: Anesthesia, Immune system, Perioperative care, Obesity, Inflammation

Core tip: Anesthetic agents have been studied not only for their effects on anesthesia and analgesia, but also their action on the lungs and immune system. Obesity is associated with a chronic state of low-grade systemic inflammation, and may predispose to development of comorbidities. Although efforts have been made to develop guidelines for anesthesia in obesity, to date, no ideal drug combination has been found. Optimization of the immunomodulatory properties of anesthetic agents may enable perioperative modulation of inflammatory response in obese patients and improve postoperative outcomes.

INTRODUCTION

Obesity and associated comorbidities are increasing at epidemic proportions globally[1], with a substantial impact on postoperative outcomes for affected individuals undergoing minor or major surgical procedures that require anesthesia. Intravenous and inhalational anesthetics (IAs) have been shown to modulate the innate and adaptive immune responses, as well as indirect effectors of immunity[2,3].

Since obesity results in chronic low-grade inflammation or metainflammation[4] associated with increased circulating proinflammatory factors, it has been proposed that anesthetic agents may modulate the already altered immune function in obesity, with particular emphasis on pulmonary inflammation.

This review article aims to integrate current knowledge regarding the effects of commonly used anesthetic agents on the lungs and immune response with the underlying immunology of obesity. Additionally, it provides insights and future perspectives into the safe use of anesthetics as immunomodulators for obese patients. Better knowledge of the impact of anesthetic agents on the immune system, especially in the setting of obesity, may improve perioperative management and outcome.

IMMUNE AND INFLAMMATORY CHANGES DUE TO OBESITY: THE ROLE OF IMMUNE CELL INFILTRATION IN ADIPOSE TISSUE

Healthy adipose tissue (AT) is composed of a type-2 polarized immune system, which maintains AT macrophages (ATM) in an M2-like (pro-resolution) state. While in this form, AT is mainly composed of eosinophils, invariant-chain natural killer T (iNKT) cells[5], and regulatory T (Treg) cells[6], which produce interleukin (IL)-4, IL-13, and IL-10. Adipocytes also contribute to the type 2 immune response through production of adiponectin, which exhibits a strong anti-inflammatory effect[7]. These type 2 immune cells are supported by a stromal structure, which promotes immune cell viability through the production of several cytokines, with IL-33 playing a particularly important role[8,9]. Moreover, in order to sustain this environment, AT cells engage in extensive cross-talk to (re)model AT structure and phenotype[10].

The early phases of the diet-induced obesity (DIO) period are characterized by an increase in the amount of fat per adipocyte and an accumulation of immune cells. Acute changes in the microenvironment, such as alterations in oxygen supply and consumption, contribute to triggering a rapid increase in the number of neutrophils[11]. Adipocytes become hypertrophic and hyperplastic. This is associated with a shift in adipokine production from adiponectin to leptin, monocyte chemo-attractant protein-1 (MCP-1), and IL-6, as well as resistin, visfatin, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, retinol binding protein 4 (RBP4), lipocalin-2, and CXCL5[12]. Leptin directly increase the production of several proinflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6, TNF-α, the chemokines CCL2/MCP-1, and leukotriene B4 (LTB4) in peripheral blood monocytes and resident tissue macrophages[13]. Leptin can also induce the production of reactive intermediates in macrophages, neutrophils, and endothelial cells, as well as potentiate interferon (IFN)-γ induced expression of nitric oxide (NO) synthase[14-16], whereas adiponectin, IL-10, and omentin, which have anti-inflammatory effects, are downregulated[17]. In addition, innate inflammatory molecules such as acute phase reactants, C-reactive protein (CRP)[18], complement components C2, C3, and C4[19,20], and other immune-modulating mediators produced in AT contribute to the intricate connection between fat and its tissue-resident immune cells.

The adaptive immunity role is mediated by T-lymphocyte infiltration during early AT inflammation, preceding macrophage recruitment[21,22]. Most of these are CD4+ lymphocytes that differentiate to TH1-cells, governing the local inflammatory process through the release of proinflammatory cytokines like IFN-γ and TNF-α. T-cell recruitment is usually mediated by chemokines released from endothelial cells, stromal cells, or macrophages. While, on the one hand, T-cell derived IFN-γ promotes the recruitment of monocytes by MCP-1 secretion from preadipocytes, it also activates other cells, including macrophages[21].

Resident and recruited ATM are the most common immune cell types in AT, and their infiltration is associated with AT inflammation[23,24]. Recruited AT macrophages induce tissue inflammation when their polarization shifts from an M2 type to an activated proinflammatory M1 state. Stimuli for this shift toward the M1 phenotype includes systemic factors, such as increase in free fatty acids (FFAs), which stimulates toll-like receptors (TLR)-4 on macrophages[25], and activation of the inflammasome, which is responsible for production of the proinflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-18[26]. In addition, IFN-γ is a potent local inducer of M1 polarization during ATM inflammation[27].

The link between metabolism and immunity at the intracellular level occurs through activation of nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) and its cytoplasmic inhibitor IκκB. Likewise, other inflammatory factors, such as c-Jun N-terminal protein kinases (JNK), are activated[28,29]. These proinflammatory mediators are produced in excess, spilling into the peripheral circulation and contributing to the low-grade systemic inflammation that ultimately influences the development of obesity-associated comorbidities, including the pulmonary immune response, thus contributing to pulmonary inflammation[12,30].

AT immune cells contribute to the maintenance of homeostasis and development of chronic inflammation and are responsible for the mechanisms underlying obesity-associated complications and impairment of normal immune system functioning, thus further perpetuating chronic disease development and metabolic complications.

LUNG IMMUNE CELLS AND OBESITY-ASSOCIATED INFLAMMATION

Several mediators elicited by obesity alter immune and inflammatory responses in the lung, and may induce obesity-associated changes to adipokines and lung immune cells.

Leptin

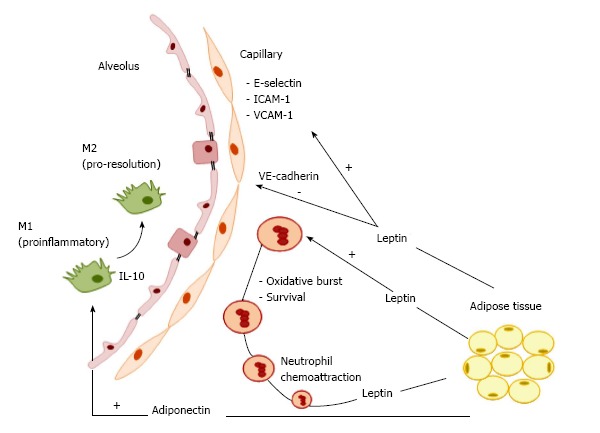

Several lung cell types, such as leukocytes, airway smooth muscle cells, alveolar epithelial cells, and macrophages, express the functional leptin receptor, which, when bound to its main ligand (systemic leptin), participates in triggering inflammatory respiratory diseases. Lungs represent a target organ for leptin signaling. In this line, leptin stimulates neutrophil and macrophage release of cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6, IL-12), eicosanoids, and NO and induces neutrophil oxidative burst[31]. Endogenous leptin has two main effects in the lungs (Figure 1). First, it acts as a neutrophil chemoattractant to the lungs[32]. Once neutrophil levels are increased, leptin lengthens neutrophil survival by delaying or inhibiting apoptosis[33]. Additionally, obese patients with increased levels of leptin exhibited increased susceptibility to respiratory infections, in an association that may be independent and likely additive to metabolic syndrome-related factors[34]. Furthermore, the proinflammatory effects of leptin may contribute to a higher incidence of asthma in the obese population[35]. In chronic obstructive pulmonary disease[36,37], the higher the leptin production, the greater the severity of the disease[38,39]. In the setting of obesity, not only immune cells but also structural cells in the alveolar-capillary membrane are altered. In obese mice, the lung endothelium was found to express higher levels of leukocyte adhesion markers (E-selectin, ICAM-1 and VCAM-1) and lower levels of junctional proteins (VE-cadherin and β-catenin) (Figure 1), providing further evidence that obesity may impair vascular homeostasis and increase susceptibility to inflammatory lung vascular diseases[40].

Figure 1.

Model of obesity-associated pulmonary inflammation. Lung immune cells and inflammation due to obesity. Leptin is implicated in inflammatory respiratory diseases as a neutrophil chemoattractant. The association between obesity and LPS-induced lung inflammation involves an increase in monocytes and lymphocytes, as well as in intracellular adhesion molecule (ICAM)-1 expression in alveolar macrophages, suggesting their polarization toward a pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype. Obesity impairs vascular homeostasis, facilitating increased susceptibility to inflammatory lung vascular diseases by affecting structural cells in the alveolar-capillary membrane. The lung endothelium of obese mice has been shown to express higher levels of leukocyte adhesion markers (E-selectin, ICAM-1, VCAM-1) and lower levels of junctional proteins (VE-cadherin and β-catenin). Adiponectin has anti-inflammatory properties, mainly by its effects on toll-like receptor (TLR) pathway-mediated NF-κB signaling, which regulates the shift from M1 to M2 macrophage polarization, and suppresses differentiation of M1 macrophages by downregulating the pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α, MCP-1, and IL-6. Adiponectin also promotes expression of the anti-inflammatory factor IL-10 in macrophages via cAMP-dependent mechanisms. TNF: Tumor necrosis factor; IL: Interleukin; LPS: Lipopolysaccharide.

In short, leptin plays an important role in respiratory immune responses and pathogenesis of inflammatory respiratory conditions by acting on different cell types in the lung.

Adiponectin

Adiponectin is a well-defined obesity marker that has anti-inflammatory properties. Its predominant immune-related functions involve suppression of inflammation by clearance of apoptotic cell debris[41] and promotion of an anti-inflammatory phenotype in the lung by blunting oxidative stress, inflammation, and angiogenesis. However, several of these immune-related functions depend on the respective adiponectin receptor. AdipoR1, AdipoR2, T-cadherin, and calreticulin are detected in several lung cells[42]. The structure of adiponectin resembles those of complement factor C1q and of surfactant proteins, which act as pattern recognition molecules limiting lung inflammation[43]. Adiponectin receptors are also involved in the regulation of macrophage proliferation and function. AdipoR1 mediates adiponectin suppression of NF-κB activation and proinflammatory cytokine expression in macrophages[44,45], AdipoR2 is involved in adiponectin-mediated M2 polarization[46], and T-cadherin has been shown to play an essential role in the stimulatory effects of adiponectin on M2 macrophage proliferation[47]. The anti-inflammatory effects of adiponectin are mainly guided by the toll-like receptor (TLR) mediated NF-κB signaling pathway, which modulates a shift in macrophage polarization from M1 to M2 (Figure 1) and suppresses differentiation of M1 macrophages by downregulating the proinflammatory cytokines TNF-α, MCP-1, and IL-6[48,49]. Moreover, adiponectin increases expression of the anti-inflammatory factor IL-10 in macrophages via cAMP-dependent mechanisms[50]. Adiponectin has also been proposed to regulate energy and metabolism by targeting innate-like lymphocytes (ILC2)[10,51], natural killer T (NKT)[52], and gamma delta T (γδT)cells[53].

Adiponectin senses metabolic stress and modulates metabolic adaptation by targeting functions of the innate immune system, including macrophage polarization and lymphocyte activity.

ANESTHESIA, ANESTHETICS, AND IMMUNOMODULATION

Anesthesia and the surgical stress response result in several immunological alterations, which cannot be easily separated. The pharmacological effects of anesthetic drugs (sedation, anesthesia, and analgesia) have been widely studied, as have their actions on several cell types, including inflammatory cells, by altering cytokine release[54]; cytokine receptor expression[55]; phagocytosis or cytotoxic actions[56]; and transcription or translation of protein mediators[57,58]. Depending on the clinical setting, immunosuppression and activation can be either detrimental or beneficial. These effects are clinically important because the balance between pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokine secretion is associated with surgical outcomes.

Immune cells are categorized into two lines according to their maturation site: The myeloid lineage, which includes macrophages, dendritic cells (DCs), mast cells, and granulocytes (neutrophils, eosinophils and basophils); and the lymphoid lineage, which is composed of T and B lymphocytes, natural killer (NK) cells, and NK T cells[59,60]. Myeloid cells are considered the main players in innate immunity, and play important roles in adaptive immunity as well; they serve as antigen presenters and macrophages, mast cells, and neutrophils produce several cytokines, thus activating T and B lymphocytes[60]. Immunomodulation can have a dichotomous sense whereby suppression of the immune response can prevent further injury, as observed in models of acute inflammation[61], but also prevent the body from counteracting infections and increase the risk of opportunistic infections. In these scenarios, both inhalational and intravenous anesthetic agents may jeopardize or improve immune function.

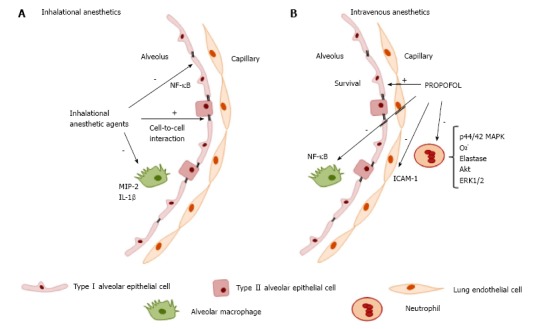

IA agents

The action of IAs on immune cells has been extensively reviewed in preclinical studies[2,62,63]. In vitro experiments on immune cells revealed generally transient, dose- and time-dependent effects predominantly on neutrophil function[64-66], lymphocyte proliferation[67], suppression of inflammatory cytokines in rat alveolar cells, and decrease in the expression of inducible NO synthase by inhibition of voltage-dependent calcium channels, reducing intracellular calcium concentrations[68]. However, in an ischemic setting, the suppression of neutrophil adhesion had a positive effect against the deleterious effects of polymorphonuclear cells, improving cardiac function[69-72]. Furthermore, exposure to the isoflurane attenuated villus, hepatic, and renal injuries in a mouse model of intestinal ischemia; these effects were mediated via plasma membrane phosphatidylserine externalization and subsequent release of the anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic cytokine transforming growth factor β1 (TGF-β1)[73]. In both studies, the proposed mechanisms for protection rely on modulation of endothelial and neutrophil adhesion molecules and reduction of neutrophil migration and margination into tissues[74]. In human endothelial cells, the effects of isoflurane against TNF-α-induced apoptosis are mediated by the phosphorylation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK MAPK) and induction of sphingosine kinase 1 (SK1) to increase production of the lysophospholipid S1P, a cytoprotective signaling molecule product of sphingomyelin hydrolysis that functions as an extracellular ligand for specific G protein-coupled receptors and as an intracellular second messenger[75]. In the context of acute inflammatory lung injury (Figure 2A), isoflurane has been shown to decrease neutrophil influx, as well as the synthesis and expression of macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-2, IL-1β, and the stress proteins heme oxygenase (HO-1) and heat shock protein (HSP-70)[76-79]. These studies showed reduction of proinflammatory cytokine release through several mechanisms: (1) inhibition of NF-κB translocation into the nuclei of human epithelial cells[58,76]; (2) inhibition of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) expression and blockade of NF-κB activation in a mouse model of lung injury; (3) inhibition of proapoptotic procaspase-8, procaspase-3, and inactivated proapoptotic protein Bax expression; (4) promotion of phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase/Akt activation and enhanced expression of the antiapoptotic B-cell lymphoma-2 (Bcl-2)-related protein homeostasis[80]; and (5) maintenance of alveolar epithelial adherence by attenuating reduction of zona occludens 1 (ZO-1) levels[81].

Figure 2.

Modulatory effects of anesthetic agents on lung immune cells. A: Inhaled anesthetics: Decreased neutrophil influx, synthesis, and expression of macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-2, IL-1β, and stress proteins heme oxygenase (HO-1) and heat shock protein (HSP-70). Reduction of pro-inflammatory cytokine release, inhibition of iNOS expression and activity by blockade of NF-κB activation in lung tissue, inhibition of proapoptotic procaspase protein expression, and maintenance of alveolar epithelial adherence by attenuating reduction of zona occludens 1 (ZO-1) levels; B: Intravenous anesthetic (propofol): Impairs neutrophil activity by inhibition of phosphorylation of the mitogen-activated protein kinases p44/42 MAPK signaling pathway and disrupts the downstream signaling pathway involving calcium, Akt, and ERK1/2, which decreases superoxide generation, elastase release, and chemotaxis.

Intravenous anesthetic agents

The intravenous anesthetics (IVAs) ketamine and dexmedetomidine, although very important in clinical practice, have well-recognized and characterized immunomodulatory effects and will not be covered in the present review. The immunomodulatory effects of propofol have been investigated since it is widely used for general anesthesia and for sedation at sub-anesthetic doses. In vitro studies have shown that use of propofol at clinically relevant plasma concentrations impairs several monocyte and neutrophil functions, such as chemotaxis[82,83], phagocytosis[84], respiratory oxidative burst activity[85] cellular killing processes, and bacterial clearance[56,86] (Figure 2B). Some of these inhibitory properties are related to its lipid vehicle[87]. However, at the intracellular signal transduction level, Nagata et al[88] have proposed that some of the inhibitory effects of propofol on neutrophil activity may be mediated by inhibition of the phosphorylation of the mitogen-activated protein kinases p44/42 MAPK signaling pathway. A role of other pathways (such as p38 MAPK) in neutrophil chemotaxis has also been posited. Recently, Yang et al[89] proposed a novel mechanism for the anti-inflammatory effects of propofol on fMLF-activated human neutrophils. Propofol decreased superoxide generation, elastase release, and chemotaxis, in a mechanism mediated by competitive blockade of the interaction between fMLF and its formyl peptide receptor (FPR)1, thus disrupting the downstream signaling pathway involving calcium, Akt, and ERK1/2. This provides additional evidence of the potential therapeutic effect of propofol to attenuate neutrophil-mediated inflammatory diseases[89]. In an animal model of endotoxemia, the anti-inflammatory effect of propofol decreased TNF-α, IL-1, and IL-6 levels[90]. Further research in murine macrophages suggests that propofol suppresses lipopolysaccharide (LPS)/TL R4-mediated inflammation through inhibition of NF-κB activation[91] and does not affect MAPKs, including ERK1/2, p38 MAPK, or JNK. The antioxidant properties of propofol, capable of regulating reactive oxygen species (ROS)-mediated Akt and NF-κB signaling, have also been considered. In a clinical study of patients undergoing craniotomy, propofol prevented the decrease in Th1/Th2 cell ratio seen with isoflurane anesthesia[92]. However, no differences in neutrophil function or cellular markers in lymphocytes and monocytes have been observed in patients with severe brain injury requiring long-term sedation with propofol[93].

Studies have demonstrated several effects of propofol in the pulmonary immune response to acute inflammation. It protected cultured alveolar epithelial cells from apoptosis and autophagy by prevention of LPS-induced mitochondrial dysfunction and inhibition of LPS-induced activation of apoptotic signals (caspase 9 activity, ROS overproduction, and Ca2+ accumulation)[94,95]; attenuated iNOS mRNA expression, NO, and TNF-α, which was associated with improved survival in a murine model of endotoxin-induced acute lung injury[94]; decreased neutrophil influx into the lungs through reduction of ICAM-1 expression[96]; reduced apoptosis of lung epithelial cells by downregulation of LPS-induced cytokines (IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α); and reduced levels of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1α, a transcription factor essential for regulating oxygen homeostasis[97]. The lipid carrier vehicle or other constituents of propofol formulations may also contribute to these immunomodulatory effects[87,98].

Many IVAs, including propofol, barbiturates, and benzodiazepines, produce their sedative and anesthetic effects on the central nervous system by inhibition of the GABAA receptor[99]. It is also known that immune system cells are capable of synthesizing and releasing GABA neurotransmitters, which are parts of the neuronal GABA signaling system. The absence of a presynaptic terminal defines these channels in immune cells as extrasynaptic-like channels[100]. GABAA receptors are present on immune cells, and are a potential site of drug action[101]. Studies have shown that, in asthmatic mice, the anti-inflammatory effect of propofol on Th2 inflammation is mediated by inhibition of Th2 cell differentiation, a mechanism attributed to induction of apoptosis via the GABA receptor during Th2 development[102].

In contrast, impairment of immune function by anesthetics may play a role in immunocompromised patients. In this line, Wheeler et al[103] demonstrated that, through their actions on the GABAA receptor, propofol and thiopental inhibited monocyte chemotaxis and phagocytosis. The implications clinical proposed reflect this dichotomous sense: If a patient’s primary pathology is inflammatory, the immunomodulatory effects of propofol or thiopental could be therapeutic, but if the immune response is ineffective, these agents may increase the risk of infection[103].

Opioids

Although the main role of opioid peptides is the modulation of pain by binding to the opioid receptors widely distributed in the central nervous system, there is evidence of immunomodulatory effects exerted by endogenous and synthetic peptides, which activate opioid receptors. Different opioids show different effects on the immune system; immunosuppressive, immunostimulatory, or dual. Proposed mechanisms and sites of action of opioid-mediated immune modulation include: (1) direct action on the immune cells to modulate immune response, with the mu opioid receptor as the main molecular target; (2) the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA); and (3) modulation of the sympathetic activity, either in isolation or a combination thereof[104]. The interaction of opioids with each of these sites is complex and both species- and time-dependent. Regarding T helper cell balance, some opioids (fentanyl, methadone) have been shown to induce IL-4 and exert an anti-inflammatory effect on human T lymphocytes. Conversely, morphine and buprenorphine have not been shown to increase IL-4 mRNA or protein levels[105]. The proposed mechanism of this effect is that different agonists at opioid receptors in T cells may induce different signaling pathways or activate certain pathways with differential intensity.

Chronic morphine administration can suppress the innate immune system by inhibiting cytokine secretion, decreasing bacterial clearance by inhibiting macrophage phagocytosis, and altering leukocyte recruitment[106,107]. On the adaptive immune system, morphine interferes with antigen presentation, prevents activation and proliferation of T lymphocytes, and decreases T cell responses, contributing to lymphocyte apoptosis and B cell differentiation into antibody-secreting plasma cells[106,108]. Therefore, morphine use may be advantageous early in the inflammatory process, but after the initial inflammatory stage, its administration might be associated with an increase rate of infection[106].

While many experimental studies have highlighted the significant immunosuppression caused by opioids or their withdrawal[109], the results from clinical studies are still vague. No conclusive evidence exists that opioids contribute to or prevent infections perioperatively, in the ICU, or when used in the treatment of acute or chronic pain. Moreover, coexisting or underlying diseases such as cancer, diabetes mellitus, sepsis, and even obesity can all induce significant alterations in immune status. These comorbidities and some medications often used concomitantly in the perioperative period, such as corticosteroids, might modify the potential role of opioid-induced immunosuppression[110].

IAs and IVAs have diverse immunomodulatory effects that may yield positive or negative consequences on different disease processes (such as endotoxemia, generalized sepsis, tumor growth and metastasis, and ischemia-reperfusion injury). Therefore, anesthesiologists should consider the immunomodulatory effects of anesthetic drugs when designing anesthetic protocols for their patients. Considering the influence of obesity and anesthetic agents on lung immune cells, it is important to investigate the possible joint role of these factors, e.g., during anesthesia induction in the obese population.

IMMUNOMODULATORY EFFECTS OF ANESTHETICS IN OBESITY

Obesity is a heterogenous condition. Inter-individual variability in AT distribution, presence of the metabolic syndrome, and other associated comorbidities confer several degrees of risk and require different levels of care, thus creating potential confounders that may affect outcomes in research studies. Therefore, perioperative care and anesthesia in obese patients are a great challenge. To date, several studies has proposed to answer the question of which anesthetic agent is best for the obese patient[111-114]. Most of these investigations have evaluated primary outcomes during and after anesthesia[115,116]. Although efforts have been made to develop standardized guidelines or protocols for the anesthetic care of the obese patient[117], there is no known ideal anesthesia technique or drug combination. However, the introduction of enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocols after obesity-related and bariatric procedures has gained great acceptance[118,119].

Despite the growing body of evidence supporting significant immunomodulatory effects for several anesthetic agents, there is a paucity of data on anesthetic-mediated immunomodulation in obesity. In this line, two small randomized controlled trials enrolling obese surgical patients evaluated the effects of different anesthetic approaches (Table 1). Abramo et al[120] investigated the effects of total intravenous anesthesia (TIVA), inhalation anesthesia (sevoflurane), or xenon anesthesia on serum levels of proinflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IL-10, TNF-α) and NO. The authors observed that xenon anesthesia was superior to the other two strategies in inhibiting postoperative serum TNF-α concentrations, but found no differences in other mediators[120]. The effects of ketamine on inflammatory and immune responses after short-duration procedures were similar to those previously reported in non-obese patients[121].

Table 1.

Clinical studies of effects of anesthesia on immune cells and outcomes in obese patients

| Ref. | Population | Interventions | Comparison | Outcome |

| Abramo et al[120] | Morbidly obese patients undergoing laparoscopic gastric bypass (n = 30) | TIVA Sevoflurane anesthesia Xenon anesthesia | Serum levels of IL-6, IL-10, TNF-α, and NO before anesthesia, at the end of surgery, and 12 h after the end of surgery | At the end of surgery, IL-10 and TNF-α levels were lower in patients anesthetized with xenon than in those given sevoflurane or TIVA |

| Roussabrov et al[121] | Obese patients undergoing short-duration gastric or uterine surgery (n = 36) | Ketamine (IV) pre- induction compared with no ketamine before general anesthesia | Serum levels of IL-1β, IL-2, IL-6, TNF- α, lymphocyte proliferation, and NK cell cytotoxicity | Results to those of previous studies in lean patients: No change in inflammation or immune response (11 studies), suppressed immune response (9 studies), or enhanced immune responses (1 study) |

Summary of results from clinical studies comparing inhalational and intravenous anesthetics according to population, intervention, comparison, and outcomes. IV: Intravenous; IL: Interleukin; TNF: Tumor necrosis factor; NK: Natural killer cells; NO: Nitric oxide; TIVA: Total intravenous anesthesia.

Inhaled anesthetics exert multiple protective effects that enhance perioperative organ function preservation in humans[122] and small animals[2]. Preclinical data have investigated the effects of anesthetic agents on the low-grade chronic inflammation of obesity[123-128]. These studies focused on the interaction of obesity and the metabolic syndrome with the expected protective effects of IAs, but did not evaluate immune system interactions.

In one study, sevoflurane preconditioning failed to induce cardioprotection in obese animals, in contrast to the effect observed in lean animals[123]. This negative effect can be explained by reduced activation of the ROS-mediated AMPK signaling pathway[123]. In another study, van den Brom et al[124] showed that sevoflurane has a stronger depressant effect on myocardial function than other agents, thus possibly increasing cardiac vulnerability to limited oxygen supply and increasing risk of ischemia during surgery.

Concerning the role of adrenergic receptors, the long-term metabolic stress seen in obesity and diabetes type 2 alters type α and β adrenoceptor (AR) function and their interaction with isoflurane anesthesia. Bussey et al[125] showed that isoflurane anesthesia enhanced α-AR sensitivity, normalized β-AR response, and impaired cardiovascular function by reducing hemodynamic compensation during acute stress in experimental obesity and type 2 diabetes. Finally, Zhang et al[126] showed that the expected cardioprotective effect of sevoflurane against reperfusion injury through interference on myocardial iNOS signaling was absent in hypercholesterolemic rats.

Obesity has been implicated in altering the protective postconditioning effect of sevoflurane anesthesia against cerebral ischemic injury. Molecular analyses demonstrated reduced expression of Kir6.2, a significant mitoKATP channel component in the brain. This reduced Kir6.2 expression may diminish mitoKATP channel activity, contributing to an inability to postcondition the brain against ischemia reperfusion-injury[127]. Furthermore, in a study of mice fed a high-fat diet, attenuation of neuroprotection was observed after isoflurane exposure in hippocampal slices exposed to oxygen-glucose deprivation. Obese mice exhibited higher levels of carboxyl-terminal modulator protein (CTMP, an Akt inhibitor) and lower levels of phosphorylated Akt than age-matched animals fed a regular diet, suggesting an influence of high-fat diet in decreasing prosurvival Akt signaling in the brain. This may explain the higher isoflurane concentrations required to neuroprotect from oxygen-glucose deprivation in this study[128]. Table 2 lists recent preclinical studies that assessed the potential cardioprotective and neuroprotective effects of IAs in animals with obesity and the metabolic syndrome.

Table 2.

Animal studies of effects of inhalational anesthesia in obese or MetS animals

| Ref. | Population | Interventions | Comparison | Outcome in obese animals | Outcome in lean animals |

| Song et al[123] | Animals fed high-fat vs low-fat diet | Myocardial ischemia and reperfusion | Ctrl x Sevoflurane preconditioning | No sevoflurane cardioprotection | Sevoflurane: ↓ infarct size; ↑endothelial nitric oxide synthase, myocardial nitrite and nitrate |

| van den Brom et al[124] | Animals fed western vs control diet | Sevoflurane 2% vs baseline on echocardiographic myocardial perfusion and function | Myocardial perfusion and systolic function | Sevoflurane: No additional effect on myocardial perfusion but impaired systolic function | Sevoflurane: ↑ microvascular filling velocity, no change in myocardial perfusion |

| Bussey et al[125] | Zucker type 2 diabetic Zucker obese vs lean counterpart animals | Conscious vs 2% isoflurane anesthesia | Hemodynamic effects (mean arterial pressure, heart rate) of α or β adrenoreceptor (AR) stimulation | Isoflurane exacerbated and prolonged α-AR sensitivity and normalized chronotropic β-AR responses | Maintenance of ↑ α-AR sensitivity, ↑ chronotropic β-AR heart rate and mean arterial pressure responses |

| Zhang et al[126] | Animals with hypercholesterolemia vs normocholesterolemic animals | 60 min sevoflurane pre-treatment, 12 h before myocardial IR surgery | Expression of myocardial iNOS and eNOS | No cardioprotectant effects of sevoflurane, downregulation of eNOS. Interference with iNOS signaling pathway | Delayed sevoflurane cardioprotection: decreased infarct size and improved ventricular function |

| Yang et al[127] | Animals fed high-fat vs low-fat diet | 60 min focal cerebral ischemia followed by 24 h of reperfusion 15 min sevoflurane postconditioning | Cerebral infarct volume, neurological score, motor coordination 24 h after reperfusion | Sevoflurane post-conditioning failed to confer neuroprotection; no neuroprotective effect of mitoKATP channel opener | Sevoflurane ↓ infarct size, improved neurological deficit scores; neuroprotective effect of mitoKATP channel opener |

| Yu et al[128] | Animals fed high-fat vs low-fat diet | Middle cerebral artery occlusion; Isoflurane post-treatment after 20 min in vitro ischemia or transient middle cerebral artery occlusion | Cell injury in hippocampal slices, brain infarct volume, neurological deficit | Attenuated isoflurane-induced neuroprotection; ↓ Akt signaling pathway | Isoflurane post-treatment ↓ injury |

Summary of the results of experimental studies comparing inhalational anesthetics according to population, intervention, comparison, and outcomes. AR: Adrenergic receptor; eNOS: Endothelial nitric oxide; IR: Ischemia-reperfusion.

One study showed that, apart from cardioprotective effects, 1 h of propofol (but not dexmedetomidine) infusion increased airway resistance and pulmonary inflammation, in an effect mediated by expression of TNF-α and IL-6 in lung tissue[129]. These results raised questions about the proposed mechanisms of propofol or its lipid vehicles on obesity-associated metainflammation.

CONCLUSION

If the immunomodulatory properties of anesthetic agents are indeed demonstrated to have impacts on perioperative care and short-term or even long-term outcomes, this would provide clinicians and researchers with valuable evidence to rethink the use of these agents and improve their usage, particularly in the obese population. A better understanding of the complex relationships and detailed mechanisms whereby anesthetic agents modulate obesity-associated pulmonary inflammation and immune responses is a growing field of study in which additional basic-science and clinical observation data are necessary. Further studies are required to link important pharmacokinetic aspects of these drugs to relevant aspects of lung immune function in obesity-related inflammatory conditions, as well as to identify the mechanisms of these interactions so that drugs with potential lung-specific immunosuppressive effects can be identified and their impact evaluated. In the very near future, the perioperative care of the obese patient may also be guided by different anesthetic strategies, with careful regard to immune status.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to express their gratitude to Mrs. Moira Elizabeth Schöttler and Mr. Filippe Vasconcellos for their assistance in editing the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supported by Brazilian Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq); Carlos Chagas Filho Rio de Janeiro State Foundation (FAPERJ); Department of Science and Technology (DECIT); Brazilian Ministry of Health; and Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Level Personnel (CAPES).

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors have no conflict of interest.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Critical care medicine

Country of origin: Brazil

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Peer-review started: February 8, 2017

First decision: April 17, 2017

Article in press: July 10, 2017

P- Reviewer: De Cosmo G S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

References

- 1.Flegal KM, Kruszon-Moran D, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Ogden CL. Trends in Obesity Among Adults in the United States, 2005 to 2014. JAMA. 2016;315:2284–2291. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.6458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stollings LM, Jia LJ, Tang P, Dou H, Lu B, Xu Y. Immune Modulation by Volatile Anesthetics. Anesthesiology. 2016;125:399–411. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000001195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson SL, Duke-Novakovski T, Singh B. The immune response to anesthesia: part 2 sedatives, opioids, and injectable anesthetic agents. Vet Anaesth Analg. 2014;41:553–566. doi: 10.1111/vaa.12191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hotamisligil GS. Inflammation and metabolic disorders. Nature. 2006;444:860–867. doi: 10.1038/nature05485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schipper HS, Rakhshandehroo M, van de Graaf SF, Venken K, Koppen A, Stienstra R, Prop S, Meerding J, Hamers N, Besra G, et al. Natural killer T cells in adipose tissue prevent insulin resistance. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:3343–3354. doi: 10.1172/JCI62739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vasanthakumar A, Moro K, Xin A, Liao Y, Gloury R, Kawamoto S, Fagarasan S, Mielke LA, Afshar-Sterle S, Masters SL, et al. The transcriptional regulators IRF4, BATF and IL-33 orchestrate development and maintenance of adipose tissue-resident regulatory T cells. Nat Immunol. 2015;16:276–285. doi: 10.1038/ni.3085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ouchi N, Parker JL, Lugus JJ, Walsh K. Adipokines in inflammation and metabolic disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:85–97. doi: 10.1038/nri2921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miller AM, Asquith DL, Hueber AJ, Anderson LA, Holmes WM, McKenzie AN, Xu D, Sattar N, McInnes IB, Liew FY. Interleukin-33 induces protective effects in adipose tissue inflammation during obesity in mice. Circ Res. 2010;107:650–658. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.218867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Molofsky AB, Savage AK, Locksley RM. Interleukin-33 in Tissue Homeostasis, Injury, and Inflammation. Immunity. 2015;42:1005–1019. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brestoff JR, Kim BS, Saenz SA, Stine RR, Monticelli LA, Sonnenberg GF, Thome JJ, Farber DL, Lutfy K, Seale P, et al. Group 2 innate lymphoid cells promote beiging of white adipose tissue and limit obesity. Nature. 2015;519:242–246. doi: 10.1038/nature14115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Talukdar S, Oh DY, Bandyopadhyay G, Li D, Xu J, McNelis J, Lu M, Li P, Yan Q, Zhu Y, et al. Neutrophils mediate insulin resistance in mice fed a high-fat diet through secreted elastase. Nat Med. 2012;18:1407–1412. doi: 10.1038/nm.2885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mancuso P. The role of adipokines in chronic inflammation. Immunotargets Ther. 2016;5:47–56. doi: 10.2147/ITT.S73223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mancuso P, Canetti C, Gottschalk A, Tithof PK, Peters-Golden M. Leptin augments alveolar macrophage leukotriene synthesis by increasing phospholipase activity and enhancing group IVC iPLA2 (cPLA2gamma) protein expression. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2004;287:L497–L502. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00010.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raso GM, Pacilio M, Esposito E, Coppola A, Di Carlo R, Meli R. Leptin potentiates IFN-gamma-induced expression of nitric oxide synthase and cyclo-oxygenase-2 in murine macrophage J774A.1. Br J Pharmacol. 2002;137:799–804. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Caldefie-Chezet F, Poulin A, Vasson MP. Leptin regulates functional capacities of polymorphonuclear neutrophils. Free Radic Res. 2003;37:809–814. doi: 10.1080/1071576031000097526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bouloumie A, Marumo T, Lafontan M, Busse R. Leptin induces oxidative stress in human endothelial cells. FASEB J. 1999;13:1231–1238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Makki K, Froguel P, Wolowczuk I. Adipose tissue in obesity-related inflammation and insulin resistance: cells, cytokines, and chemokines. ISRN Inflamm. 2013;2013:139239. doi: 10.1155/2013/139239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Choi J, Joseph L, Pilote L. Obesity and C-reactive protein in various populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2013;14:232–244. doi: 10.1111/obr.12003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Greevenbroek MM, Jacobs M, van der Kallen CJ, Vermeulen VM, Jansen EH, Schalkwijk CG, Ferreira I, Feskens EJ, Stehouwer CD. The cross-sectional association between insulin resistance and circulating complement C3 is partly explained by plasma alanine aminotransferase, independent of central obesity and general inflammation (the CODAM study) Eur J Clin Invest. 2011;41:372–379. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2010.02418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mamane Y, Chung Chan C, Lavallee G, Morin N, Xu LJ, Huang J, Gordon R, Thomas W, Lamb J, Schadt EE, et al. The C3a anaphylatoxin receptor is a key mediator of insulin resistance and functions by modulating adipose tissue macrophage infiltration and activation. Diabetes. 2009;58:2006–2017. doi: 10.2337/db09-0323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kintscher U, Hartge M, Hess K, Foryst-Ludwig A, Clemenz M, Wabitsch M, Fischer-Posovszky P, Barth TF, Dragun D, Skurk T, et al. T-lymphocyte infiltration in visceral adipose tissue: a primary event in adipose tissue inflammation and the development of obesity-mediated insulin resistance. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:1304–1310. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.165100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Şelli ME, Wick G, Wraith DC, Newby AC. Autoimmunity to HSP60 during diet induced obesity in mice. Int J Obes (Lond) 2017;41:348–351. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2016.216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weisberg SP, McCann D, Desai M, Rosenbaum M, Leibel RL, Ferrante AW Jr. Obesity is associated with macrophage accumulation in adipose tissue. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1796–1808. doi: 10.1172/JCI19246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu H, Barnes GT, Yang Q, Tan G, Yang D, Chou CJ, Sole J, Nichols A, Ross JS, Tartaglia LA, et al. Chronic inflammation in fat plays a crucial role in the development of obesity-related insulin resistance. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1821–1830. doi: 10.1172/JCI19451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shi H, Kokoeva MV, Inouye K, Tzameli I, Yin H, Flier JS. TLR4 links innate immunity and fatty acid-induced insulin resistance. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:3015–3025. doi: 10.1172/JCI28898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wen H, Gris D, Lei Y, Jha S, Zhang L, Huang MT, Brickey WJ, Ting JP. Fatty acid-induced NLRP3-ASC inflammasome activation interferes with insulin signaling. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:408–415. doi: 10.1038/ni.2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rocha VZ, Folco EJ, Sukhova G, Shimizu K, Gotsman I, Vernon AH, Libby P. Interferon-gamma, a Th1 cytokine, regulates fat inflammation: a role for adaptive immunity in obesity. Circ Res. 2008;103:467–476. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.177105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Solinas G, Vilcu C, Neels JG, Bandyopadhyay GK, Luo JL, Naugler W, Grivennikov S, Wynshaw-Boris A, Scadeng M, Olefsky JM, et al. JNK1 in hematopoietically derived cells contributes to diet-induced inflammation and insulin resistance without affecting obesity. Cell Metab. 2007;6:386–397. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hirosumi J, Tuncman G, Chang L, Görgün CZ, Uysal KT, Maeda K, Karin M, Hotamisligil GS. A central role for JNK in obesity and insulin resistance. Nature. 2002;420:333–336. doi: 10.1038/nature01137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sethi JK, Vidal-Puig AJ. Thematic review series: adipocyte biology. Adipose tissue function and plasticity orchestrate nutritional adaptation. J Lipid Res. 2007;48:1253–1262. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R700005-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Procaccini C, Jirillo E, Matarese G. Leptin as an immunomodulator. Mol Aspects Med. 2012;33:35–45. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2011.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ubags ND, Vernooy JH, Burg E, Hayes C, Bement J, Dilli E, Zabeau L, Abraham E, Poch KR, Nick JA, et al. The role of leptin in the development of pulmonary neutrophilia in infection and acute lung injury. Crit Care Med. 2014;42:e143–e151. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bruno A, Conus S, Schmid I, Simon HU. Apoptotic pathways are inhibited by leptin receptor activation in neutrophils. J Immunol. 2005;174:8090–8096. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.12.8090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ubags ND, Stapleton RD, Vernooy JH, Burg E, Bement J, Hayes CM, Ventrone S, Zabeau L, Tavernier J, Poynter ME, et al. Hyperleptinemia is associated with impaired pulmonary host defense. JCI Insight. 2016;1:pii: e82101. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.82101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sideleva O, Suratt BT, Black KE, Tharp WG, Pratley RE, Forgione P, Dienz O, Irvin CG, Dixon AE. Obesity and asthma: an inflammatory disease of adipose tissue not the airway. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186:598–605. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201203-0573OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bruno A, Chanez P, Chiappara G, Siena L, Giammanco S, Gjomarkaj M, Bonsignore G, Bousquet J, Vignola AM. Does leptin play a cytokine-like role within the airways of COPD patients? Eur Respir J. 2005;26:398–405. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00092404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shore SA, Schwartzman IN, Mellema MS, Flynt L, Imrich A, Johnston RA. Effect of leptin on allergic airway responses in mice. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115:103–109. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vernooy JH, Ubags ND, Brusselle GG, Tavernier J, Suratt BT, Joos GF, Wouters EF, Bracke KR. Leptin as regulator of pulmonary immune responses: involvement in respiratory diseases. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2013;26:464–472. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2013.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Malli F, Papaioannou AI, Gourgoulianis KI, Daniil Z. The role of leptin in the respiratory system: an overview. Respir Res. 2010;11:152. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-11-152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shah D, Romero F, Duong M, Wang N, Paudyal B, Suratt BT, Kallen CB, Sun J, Zhu Y, Walsh K, et al. Obesity-induced adipokine imbalance impairs mouse pulmonary vascular endothelial function and primes the lung for injury. Sci Rep. 2015;5:11362. doi: 10.1038/srep11362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 41.Takemura Y, Ouchi N, Shibata R, Aprahamian T, Kirber MT, Summer RS, Kihara S, Walsh K. Adiponectin modulates inflammatory reactions via calreticulin receptor-dependent clearance of early apoptotic bodies. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:375–386. doi: 10.1172/JCI29709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yamauchi T, Nio Y, Maki T, Kobayashi M, Takazawa T, Iwabu M, Okada-Iwabu M, Kawamoto S, Kubota N, Kubota T, et al. Targeted disruption of AdipoR1 and AdipoR2 causes abrogation of adiponectin binding and metabolic actions. Nat Med. 2007;13:332–339. doi: 10.1038/nm1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nakatsuji H, Kobayashi H, Kishida K, Nakagawa T, Takahashi S, Tanaka H, Akamatsu S, Funahashi T, Shimomura I. Binding of adiponectin and C1q in human serum, and clinical significance of the measurement of C1q-adiponectin / total adiponectin ratio. Metabolism. 2013;62:109–120. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2012.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yamaguchi N, Argueta JG, Masuhiro Y, Kagishita M, Nonaka K, Saito T, Hanazawa S, Yamashita Y. Adiponectin inhibits Toll-like receptor family-induced signaling. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:6821–6826. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mandal P, Park PH, McMullen MR, Pratt BT, Nagy LE. The anti-inflammatory effects of adiponectin are mediated via a heme oxygenase-1-dependent pathway in rat Kupffer cells. Hepatology. 2010;51:1420–1429. doi: 10.1002/hep.23427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mandal P, Pratt BT, Barnes M, McMullen MR, Nagy LE. Molecular mechanism for adiponectin-dependent M2 macrophage polarization: link between the metabolic and innate immune activity of full-length adiponectin. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:13460–13469. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.204644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hui X, Gu P, Zhang J, Nie T, Pan Y, Wu D, Feng T, Zhong C, Wang Y, Lam KS, et al. Adiponectin Enhances Cold-Induced Browning of Subcutaneous Adipose Tissue via Promoting M2 Macrophage Proliferation. Cell Metab. 2015;22:279–290. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yamaguchi N, Kukita T, Li YJ, Kamio N, Fukumoto S, Nonaka K, Ninomiya Y, Hanazawa S, Yamashita Y. Adiponectin inhibits induction of TNF-alpha/RANKL-stimulated NFATc1 via the AMPK signaling. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:451–456. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tsatsanis C, Zacharioudaki V, Androulidaki A, Dermitzaki E, Charalampopoulos I, Minas V, Gravanis A, Margioris AN. Adiponectin induces TNF-alpha and IL-6 in macrophages and promotes tolerance to itself and other pro-inflammatory stimuli. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;335:1254–1263. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.07.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Park PH, Huang H, McMullen MR, Bryan K, Nagy LE. Activation of cyclic-AMP response element binding protein contributes to adiponectin-stimulated interleukin-10 expression in RAW 264.7 macrophages. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;83:1258–1266. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0907631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lee MW, Odegaard JI, Mukundan L, Qiu Y, Molofsky AB, Nussbaum JC, Yun K, Locksley RM, Chawla A. Activated type 2 innate lymphoid cells regulate beige fat biogenesis. Cell. 2015;160:74–87. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lynch L, Nowak M, Varghese B, Clark J, Hogan AE, Toxavidis V, Balk SP, O’Shea D, O’Farrelly C, Exley MA. Adipose tissue invariant NKT cells protect against diet-induced obesity and metabolic disorder through regulatory cytokine production. Immunity. 2012;37:574–587. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mehta P, Nuotio-Antar AM, Smith CW. γδ T cells promote inflammation and insulin resistance during high fat diet-induced obesity in mice. J Leukoc Biol. 2015;97:121–134. doi: 10.1189/jlb.3A0414-211RR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gilliland HE, Armstrong MA, Carabine U, McMurray TJ. The choice of anesthetic maintenance technique influences the antiinflammatory cytokine response to abdominal surgery. Anesth Analg. 1997;85:1394–1398. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199712000-00039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schneemilch CE, Ittenson A, Ansorge S, Hachenberg T, Bank U. Effect of 2 anesthetic techniques on the postoperative proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokine response and cellular immune function to minor surgery. J Clin Anesth. 2005;17:517–527. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2004.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Heller A, Heller S, Blecken S, Urbaschek R, Koch T. Effects of intravenous anesthetics on bacterial elimination in human blood in vitro. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1998;42:518–526. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.1998.tb05160.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Loop T, Scheiermann P, Doviakue D, Musshoff F, Humar M, Roesslein M, Hoetzel A, Schmidt R, Madea B, Geiger KK, et al. Sevoflurane inhibits phorbol-myristate-acetate-induced activator protein-1 activation in human T lymphocytes in vitro: potential role of the p38-stress kinase pathway. Anesthesiology. 2004;101:710–721. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200409000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Watanabe K, Iwahara C, Nakayama H, Iwabuchi K, Matsukawa T, Yokoyama K, Yamaguchi K, Kamiyama Y, Inada E. Sevoflurane suppresses tumour necrosis factor-α-induced inflammatory responses in small airway epithelial cells after anoxia/reoxygenation. Br J Anaesth. 2013;110:637–645. doi: 10.1093/bja/aes469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ferrante AW Jr. The immune cells in adipose tissue. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2013;15 Suppl 3:34–38. doi: 10.1111/dom.12154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lee BC, Lee J. Cellular and molecular players in adipose tissue inflammation in the development of obesity-induced insulin resistance. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1842:446–462. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Medzhitov R. Origin and physiological roles of inflammation. Nature. 2008;454:428–435. doi: 10.1038/nature07201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.O’Gara B, Talmor D. Lung protective properties of the volatile anesthetics. Intensive Care Med. 2016;42:1487–1489. doi: 10.1007/s00134-016-4429-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Anderson SL, Duke-Novakovski T, Singh B. The immune response to anesthesia: part 1. Vet Anaesth Analg. 2014;41:113–126. doi: 10.1111/vaa.12125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fröhlich D, Rothe G, Schwall B, Schmid P, Schmitz G, Taeger K, Hobbhahn J. Effects of volatile anaesthetics on human neutrophil oxidative response to the bacterial peptide FMLP. Br J Anaesth. 1997;78:718–723. doi: 10.1093/bja/78.6.718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cho EJ, Yoon JH, Hong SJ, Lee SH, Sim SB. The effects of sevoflurane on systemic and pulmonary inflammatory responses after cardiopulmonary bypass. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2009;23:639–645. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2009.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Möbert J, Zahler S, Becker BF, Conzen PF. Inhibition of neutrophil activation by volatile anesthetics decreases adhesion to cultured human endothelial cells. Anesthesiology. 1999;90:1372–1381. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199905000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hamra JG, Yaksh TL. Halothane inhibits T cell proliferation and interleukin-2 receptor expression in rats. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 1996;18:323–336. doi: 10.3109/08923979609052739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Giraud O, Molliex S, Rolland C, Leçon-Malas V, Desmonts JM, Aubier M, Dehoux M. Halogenated anesthetics reduce interleukin-1beta-induced cytokine secretion by rat alveolar type II cells in primary culture. Anesthesiology. 2003;98:74–81. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200301000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kowalski C, Zahler S, Becker BF, Flaucher A, Conzen PF, Gerlach E, Peter K. Halothane, isoflurane, and sevoflurane reduce postischemic adhesion of neutrophils in the coronary system. Anesthesiology. 1997;86:188–195. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199701000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Heindl B, Reichle FM, Zahler S, Conzen PF, Becker BF. Sevoflurane and isoflurane protect the reperfused guinea pig heart by reducing postischemic adhesion of polymorphonuclear neutrophils. Anesthesiology. 1999;91:521–530. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199908000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kikuchi C, Dosenovic S, Bienengraeber M. Anaesthetics as cardioprotectants: translatability and mechanism. Br J Pharmacol. 2015;172:2051–2061. doi: 10.1111/bph.12981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tanaka K, Ludwig LM, Kersten JR, Pagel PS, Warltier DC. Mechanisms of cardioprotection by volatile anesthetics. Anesthesiology. 2004;100:707–721. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200403000-00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kim M, Park SW, Kim M, D’Agati VD, Lee HT. Isoflurane post-conditioning protects against intestinal ischemia-reperfusion injury and multiorgan dysfunction via transforming growth factor-β1 generation. Ann Surg. 2012;255:492–503. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182441767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chappell D, Heindl B, Jacob M, Annecke T, Chen C, Rehm M, Conzen P, Becker BF. Sevoflurane reduces leukocyte and platelet adhesion after ischemia-reperfusion by protecting the endothelial glycocalyx. Anesthesiology. 2011;115:483–491. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3182289988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bakar AM, Park SW, Kim M, Lee HT. Isoflurane protects against human endothelial cell apoptosis by inducing sphingosine kinase-1 via ERK MAPK. Int J Mol Sci. 2012;13:977–993. doi: 10.3390/ijms13010977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Faller S, Strosing KM, Ryter SW, Buerkle H, Loop T, Schmidt R, Hoetzel A. The volatile anesthetic isoflurane prevents ventilator-induced lung injury via phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt signaling in mice. Anesth Analg. 2012;114:747–756. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e31824762f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Vaneker M, Santosa JP, Heunks LM, Halbertsma FJ, Snijdelaar DG, VAN Egmond J, VAN DEN Brink IA, VAN DE Pol FM, VAN DER Hoeven JG, Scheffer GJ. Isoflurane attenuates pulmonary interleukin-1beta and systemic tumor necrosis factor-alpha following mechanical ventilation in healthy mice. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2009;53:742–748. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2009.01962.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chung IS, Kim JA, Kim JA, Choi HS, Lee JJ, Yang M, Ahn HJ, Lee SM. Reactive oxygen species by isoflurane mediates inhibition of nuclear factor κB activation in lipopolysaccharide-induced acute inflammation of the lung. Anesth Analg. 2013;116:327–335. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e31827aec06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Reutershan J, Chang D, Hayes JK, Ley K. Protective effects of isoflurane pretreatment in endotoxin-induced lung injury. Anesthesiology. 2006;104:511–517. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200603000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Li JT, Wang H, Li W, Wang LF, Hou LC, Mu JL, Liu X, Chen HJ, Xie KL, Li NL, et al. Anesthetic isoflurane posttreatment attenuates experimental lung injury by inhibiting inflammation and apoptosis. Mediators Inflamm. 2013;2013:108928. doi: 10.1155/2013/108928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Englert JA, Macias AA, Amador-Munoz D, Pinilla Vera M, Isabelle C, Guan J, Magaoay B, Suarez Velandia M, Coronata A, Lee A, et al. Isoflurane Ameliorates Acute Lung Injury by Preserving Epithelial Tight Junction Integrity. Anesthesiology. 2015;123:377–388. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Skoutelis A, Lianou P, Papageorgiou E, Kokkinis K, Alexopoulos K, Bassaris H. Effects of propofol and thiopentone on polymorphonuclear leukocyte functions in vitro. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1994;38:858–862. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.1994.tb04018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Jensen AG, Dahlgren C, Eintrei C. Propofol decreases random and chemotactic stimulated locomotion of human neutrophils in vitro. Br J Anaesth. 1993;70:99–100. doi: 10.1093/bja/70.1.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mikawa K, Akamatsu H, Nishina K, Shiga M, Maekawa N, Obara H, Niwa Y. Propofol inhibits human neutrophil functions. Anesth Analg. 1998;87:695–700. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199809000-00039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Fröhlich D, Rothe G, Schwall B, Schmitz G, Hobbhahn J, Taeger K. Thiopentone and propofol, but not methohexitone nor midazolam, inhibit neutrophil oxidative responses to the bacterial peptide FMLP. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 1996;13:582–588. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2346.1996.d01-405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Krumholz W, Endrass J, Hempelmann G. Propofol inhibits phagocytosis and killing of Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli by polymorphonuclear leukocytes in vitro. Can J Anaesth. 1994;41:446–449. doi: 10.1007/BF03009871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kelbel I, Koch T, Weber A, Schiefer HG, van Ackern K, Neuhof H. Alterations of bacterial clearance induced by propofol. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1999;43:71–76. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-6576.1999.430115.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Nagata T, Kansha M, Irita K, Takahashi S. Propofol inhibits FMLP-stimulated phosphorylation of p42 mitogen-activated protein kinase and chemotaxis in human neutrophils. Br J Anaesth. 2001;86:853–858. doi: 10.1093/bja/86.6.853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Yang SC, Chung PJ, Ho CM, Kuo CY, Hung MF, Huang YT, Chang WY, Chang YW, Chan KH, Hwang TL. Propofol inhibits superoxide production, elastase release, and chemotaxis in formyl peptide-activated human neutrophils by blocking formyl peptide receptor 1. J Immunol. 2013;190:6511–6519. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Taniguchi T, Yamamoto K, Ohmoto N, Ohta K, Kobayashi T. Effects of propofol on hemodynamic and inflammatory responses to endotoxemia in rats. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:1101–1106. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200004000-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hsing CH, Lin MC, Choi PC, Huang WC, Kai JI, Tsai CC, Cheng YL, Hsieh CY, Wang CY, Chang YP, et al. Anesthetic propofol reduces endotoxic inflammation by inhibiting reactive oxygen species-regulated Akt/IKKβ/NF-κB signaling. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17598. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Inada T, Yamanouchi Y, Jomura S, Sakamoto S, Takahashi M, Kambara T, Shingu K. Effect of propofol and isoflurane anaesthesia on the immune response to surgery. Anaesthesia. 2004;59:954–959. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2004.03837.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Huettemann E, Jung A, Vogelsang H, Hout Nv, Sakka SG. Effects of propofol vs methohexital on neutrophil function and immune status in critically ill patients. J Anesth. 2006;20:86–91. doi: 10.1007/s00540-005-0377-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Gao J, Zeng BX, Zhou LJ, Yuan SY. Protective effects of early treatment with propofol on endotoxin-induced acute lung injury in rats. Br J Anaesth. 2004;92:277–279. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeh050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Gu X, Lu Y, Chen J, He H, Li P, Yang T, Li L, Liu G, Chen Y, Zhang L. Mechanisms mediating propofol protection of pulmonary epithelial cells against lipopolysaccharide-induced cell death. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2012;39:447–453. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2012.05694.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Hu XM, Lu Y, Yao SL. [Propofol reduces intercellular adhesion molecular-1 expression in lung injury following intestinal ischemia/reperfusion in rats] Zhongguo Weizhongbing Jijiu Yixue. 2005;17:53–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Yeh CH, Cho W, So EC, Chu CC, Lin MC, Wang JJ, Hsing CH. Propofol inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced lung epithelial cell injury by reducing hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha expression. Br J Anaesth. 2011;106:590–599. doi: 10.1093/bja/aer005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Haitsma JJ, Lachmann B, Papadakos PJ. Additives in intravenous anesthesia modulate pulmonary inflammation in a model of LPS-induced respiratory distress. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2009;53:176–182. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2008.01844.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Bali M, Akabas MH. Defining the propofol binding site location on the GABAA receptor. Mol Pharmacol. 2004;65:68–76. doi: 10.1124/mol.65.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Jin Z, Mendu SK, Birnir B. GABA is an effective immunomodulatory molecule. Amino Acids. 2013;45:87–94. doi: 10.1007/s00726-011-1193-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Shiratsuchi H, Kouatli Y, Yu GX, Marsh HM, Basson MD. Propofol inhibits pressure-stimulated macrophage phagocytosis via the GABAA receptor and dysregulation of p130cas phosphorylation. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2009;296:C1400–C1410. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00345.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Meng J, Xin X, Liu Z, Li H, Huang B, Huang Y, Zhao J. Propofol inhibits T-helper cell type-2 differentiation by inducing apoptosis via activating gamma-aminobutyric acid receptor. J Surg Res. 2016;206:442–450. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2016.08.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Wheeler DW, Thompson AJ, Corletto F, Reckless J, Loke JC, Lapaque N, Grant AJ, Mastroeni P, Grainger DJ, Padgett CL, et al. Anaesthetic impairment of immune function is mediated via GABA(A) receptors. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17152. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Liang X, Liu R, Chen C, Ji F, Li T. Opioid System Modulates the Immune Function: A Review. Transl Perioper Pain Med. 2016;1:5–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Börner C, Lanciotti S, Koch T, Höllt V, Kraus J. μ opioid receptor agonist-selective regulation of interleukin-4 in T lymphocytes. J Neuroimmunol. 2013;263:35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2013.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Roy S, Ninkovic J, Banerjee S, Charboneau RG, Das S, Dutta R, Kirchner VA, Koodie L, Ma J, Meng J, et al. Opioid drug abuse and modulation of immune function: consequences in the susceptibility to opportunistic infections. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2011;6:442–465. doi: 10.1007/s11481-011-9292-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Ninković J, Roy S. Role of the mu-opioid receptor in opioid modulation of immune function. Amino Acids. 2013;45:9–24. doi: 10.1007/s00726-011-1163-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Börner C, Warnick B, Smida M, Hartig R, Lindquist JA, Schraven B, Höllt V, Kraus J. Mechanisms of opioid-mediated inhibition of human T cell receptor signaling. J Immunol. 2009;183:882–889. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Wang J, Barke RA, Charboneau R, Schwendener R, Roy S. Morphine induces defects in early response of alveolar macrophages to Streptococcus pneumoniae by modulating TLR9-NF-kappa B signaling. J Immunol. 2008;180:3594–3600. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.5.3594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Brack A, Rittner HL, Stein C. Immunosuppressive effects of opioids--clinical relevance. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2011;6:490–502. doi: 10.1007/s11481-011-9290-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Brodsky JB, Lemmens HJ, Saidman LJ. Obesity, surgery, and inhalation anesthetics -- is there a “drug of choice”? Obes Surg. 2006;16:734. doi: 10.1381/096089206777346592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Vallejo MC, Sah N, Phelps AL, O’Donnell J, Romeo RC. Desflurane versus sevoflurane for laparoscopic gastroplasty in morbidly obese patients. J Clin Anesth. 2007;19:3–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Zoremba M, Dette F, Hunecke T, Eberhart L, Braunecker S, Wulf H. A comparison of desflurane versus propofol: the effects on early postoperative lung function in overweight patients. Anesth Analg. 2011;113:63–69. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181fdf5d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Arain SR, Barth CD, Shankar H, Ebert TJ. Choice of volatile anesthetic for the morbidly obese patient: sevoflurane or desflurane. J Clin Anesth. 2005;17:413–419. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2004.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Katznelson R, Fisher JA. Fast wake-up time in obese patients: Which anesthetic is best? Can J Anaesth. 2015;62:847–851. doi: 10.1007/s12630-015-0406-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Liu FL, Cherng YG, Chen SY, Su YH, Huang SY, Lo PH, Lee YY, Tam KW. Postoperative recovery after anesthesia in morbidly obese patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Can J Anaesth. 2015;62:907–917. doi: 10.1007/s12630-015-0405-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Members of the Working Party. Nightingale CE, Margarson MP, Shearer E, Redman JW, Lucas DN, Cousins JM, Fox WT, Kennedy NJ, Venn PJ, Skues M, Gabbott D, Misra U, Pandit JJ, Popat MT, Griffiths R; Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain; Ireland Society for Obesity and Bariatric Anaesthesia. Peri-operative management of the obese surgical patient 2015: Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland Society for Obesity and Bariatric Anaesthesia. Anaesthesia. 2015;70:859–876. doi: 10.1111/anae.13101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Awad S, Carter S, Purkayastha S, Hakky S, Moorthy K, Cousins J, Ahmed AR. Enhanced recovery after bariatric surgery (ERABS): clinical outcomes from a tertiary referral bariatric centre. Obes Surg. 2014;24:753–758. doi: 10.1007/s11695-013-1151-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Proczko M, Kaska L, Twardowski P, Stepaniak P. Implementing enhanced recovery after bariatric surgery protocol: a retrospective study. J Anesth. 2016;30:170–173. doi: 10.1007/s00540-015-2089-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Abramo A, Di Salvo C, Baldi G, Marini E, Anselmino M, Salvetti G, Giunta F, Forfori F. Xenon anesthesia reduces TNFα and IL10 in bariatric patients. Obes Surg. 2012;22:208–212. doi: 10.1007/s11695-011-0433-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Roussabrov E, Davies JM, Bessler H, Greemberg L, Roytblat L, Yadeni IZ, Artru AA, Shapira Y. Effect of ketamine on inflammatory and immune responses after short-duration surgery in obese patients. Open Anesthesiology J. 2008;2:40–45. [Google Scholar]

- 122.Frässdorf J, De Hert S, Schlack W. Anaesthesia and myocardial ischaemia/reperfusion injury. Br J Anaesth. 2009;103:89–98. doi: 10.1093/bja/aep141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Song T, Lv LY, Xu J, Tian ZY, Cui WY, Wang QS, Qu G, Shi XM. Diet-induced obesity suppresses sevoflurane preconditioning against myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury: role of AMP-activated protein kinase pathway. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2011;236:1427–1436. doi: 10.1258/ebm.2011.011165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.van den Brom CE, Boly CA, Bulte CS, van den Akker RF, Kwekkeboom RF, Loer SA, Boer C, Bouwman RA. Myocardial Perfusion and Function Are Distinctly Altered by Sevoflurane Anesthesia in Diet-Induced Prediabetic Rats. J Diabetes Res. 2016;2016:5205631. doi: 10.1155/2016/5205631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Bussey CT, de Leeuw AE, Lamberts RR. Increased haemodynamic adrenergic load with isoflurane anaesthesia in type 2 diabetic and obese rats in vivo. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2014;13:161. doi: 10.1186/s12933-014-0161-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Zhang FJ, Ma LL, Wang WN, Qian LB, Yang MJ, Yu J, Chen G, Yu LN, Yan M. Hypercholesterolemia abrogates sevoflurane-induced delayed preconditioning against myocardial infarct in rats by alteration of nitric oxide synthase signaling. Shock. 2012;37:485–491. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e318249b7b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Yang Z, Chen Y, Zhang Y, Jiang Y, Fang X, Xu J. Sevoflurane postconditioning against cerebral ischemic neuronal injury is abolished in diet-induced obesity: role of brain mitochondrial KATP channels. Mol Med Rep. 2014;9:843–850. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2014.1912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Yu H, Deng J, Zuo Z. High-fat diet reduces neuroprotection of isoflurane post-treatment: Role of carboxyl-terminal modulator protein-Akt signaling. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2014;22:2396–2405. doi: 10.1002/oby.20879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Heil LB, Santos CL, Santos RS, Samary CS, Cavalcanti VC, Araújo MM, Poggio H, Maia Lde A, Trevenzoli IH, Pelosi P, et al. The Effects of Short-Term Propofol and Dexmedetomidine on Lung Mechanics, Histology, and Biological Markers in Experimental Obesity. Anesth Analg. 2016;122:1015–1023. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000001114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]