Abstract

Canonical WNT signaling through Frizzled and LRP5/6 receptors is transduced to the WNT/β-catenin and WNT/stabilization of proteins (STOP) signaling cascades to regulate cell fate and proliferation, whereas non-canonical WNT signaling through Frizzled or ROR receptors is transduced to the WNT/planar cell polarity (PCP), WNT/G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) and WNT/receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) signaling cascades to regulate cytoskeletal dynamics and directional cell movement. WNT/β-catenin signaling cascade crosstalks with RTK/SRK and GPCR-cAMP-PKA signaling cascades to regulate β-catenin phosphorylation and β-catenin-dependent transcription. Germline mutations in WNT signaling molecules cause hereditary colorectal cancer, bone diseases, exudative vitreoretinopathy, intellectual disability syndrome and PCP-related diseases. APC or CTNNB1 mutations in colorectal, endometrial and prostate cancers activate the WNT/β-catenin signaling cascade. RNF43, ZNRF3, RSPO2 or RSPO3 alterations in breast, colorectal, gastric, pancreatic and other cancers activate the WNT/β-catenin, WNT/STOP and other WNT signaling cascades. ROR1 upregulation in B-cell leukemia and solid tumors and ROR2 upregulation in melanoma induce invasion, metastasis and therapeutic resistance through Rho-ROCK, Rac-JNK, PI3K-AKT and YAP signaling activation. WNT signaling in cancer, stromal and immune cells dynamically orchestrate immune evasion and antitumor immunity in a cell context-dependent manner. Porcupine (PORCN), RSPO3, WNT2B, FZD5, FZD10, ROR1, tankyrase and β-catenin are targets of anti-WNT signaling therapy, and ETC-159, LGK974, OMP-18R5 (vantictumab), OMP-54F28 (ipafricept), OMP-131R10 (rosmantuzumab), PRI-724 and UC-961 (cirmtuzumab) are in clinical trials for cancer patients. Different classes of anti-WNT signaling therapeutics are necessary for the treatment of APC/CTNNB1-, RNF43/ZNRF3/RSPO2/RSPO3- and ROR1-types of human cancers. By contrast, Dickkopf-related protein 1 (DKK1), SOST and glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β) are targets of pro-WNT signaling therapy, and anti-DKK1 (BHQ880 and DKN-01) and anti-SOST (blosozumab, BPS804 and romosozumab) monoclonal antibodies are being tested in clinical trials for cancer patients and osteoporotic post-menopausal women. WNT-targeting therapeutics have also been applied as reagents for in vitro stem-cell processing in the field of regenerative medicine.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, angiogenesis, cancer stem cells, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, FGF, myeloid-derived suppressor cells, Notch, regulatory T cells, tumor microenvironment, WNT5A

1. Introduction

The WNT family of secreted glycoproteins consists of WNT1 (INT1), WNT2, WNT2B (WNT13), WNT3 (INT4), WNT3A, WNT4, WNT5A, WNT5B, WNT6, WNT7A, WNT7B, WNT8A, WNT8B, WNT9A (WNT14), WNT9B (WNT14B), WNT10A, WNT10B, WNT11 and WNT16 (1). WNT signals are transduced through the Frizzled family comprising seven-transmembrane receptors (FZD1, FZD2, FZD3, FZD4, FZD5, FZD6, FZD7, FZD8, FZD9 and FZD10) and single-transmembrane co-receptors (LRP5, LRP6, ROR1 and ROR2) to initiate the canonical and non-canonical signaling cascades (2,3).

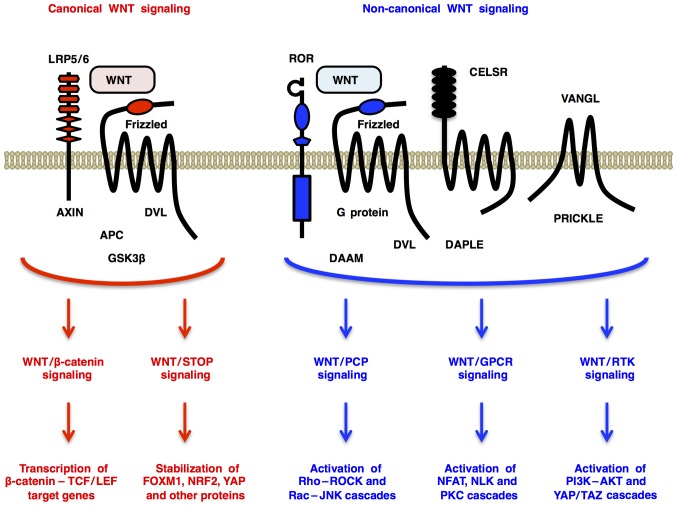

Canonical WNT signaling through Frizzled and LRP5/6 receptors promotes β-catenin-dependent transcription of TCF/LEF target genes (WNT/β-catenin signaling) (4) and β-catenin-independent de-repression of FOXM1, NRF2 (NFE2L2), YAP and other proteins [WNT/stabilization of proteins (STOP) signaling] (5,6) (Fig. 1). By contrast, non-canonical WNT signaling through Frizzled or ROR receptors activates Dishevelled-dependent Rho-ROCK and Rac-JNK cascades [WNT/planar cell polarity (PCP) signaling] (7); G protein-dependent calcineurin-NFAT, CAMK2-NLK and PKC cascades [WNT/G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) signaling] (2); and receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK)-dependent PI3K-AKT (8) and YAP/TAZ (9) cascades (WNT/RTK signaling) (Fig. 1). WNT signals regulate self-renewal, metabolism, survival, proliferation and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) of target cells (10–13), and crosstalk with FGF, Hedgehog, Notch and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) signals (14–16). As the intracellular and intercellular WNT signaling networks orchestrate embryogenesis and homeostasis, genetic alterations in WNT signaling molecules are involved in the pathogenesis of various types of human cancers and noncancerous diseases (Fig. 2).

Figure 1.

Overview of WNT signaling cascades. Canonical WNT signaling through Frizzled and LRP5/6 receptors promotes β-catenin-dependent transcription of CCND1, FZD7, MYC and other genes (WNT/β-catenin signaling) and β-catenin-independent stabilization of FOXM1, NRF2 (NFE2L2), YAP and other proteins (WNT/STOP signaling). Non-canonical WNT signaling through Frizzled or ROR receptors activates DVL-dependent Rho-ROCK and Rac-JNK cascades (WNT/PCP signaling), G protein-dependent calcineurin-NFAT, CAMK2-NLK and PKC cascades (WNT/GPCR signaling) and RTK-dependent PI3K-AKT and YAP/TAZ cascades (WNT/RTK signaling). Context-dependent WNT signaling through canonical and non-canonical signaling cascades regulates cell fate and proliferation, tissue or tumor microenvironment and whole-body homeostasis. GPCR, G protein-coupled receptor; PCP, planar cell polarity; RTK, receptor tyrosine kinase; STOP, stabilization of proteins.

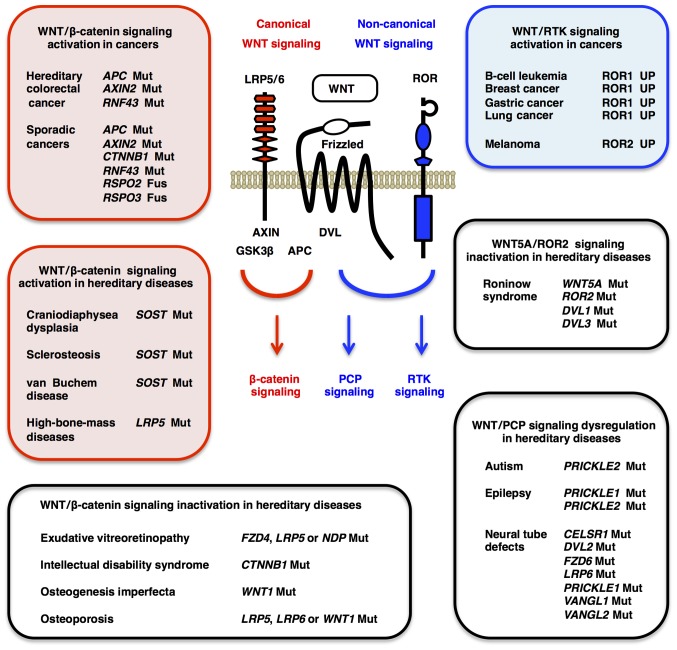

Figure 2.

WNT signaling dysregulation in cancer and non-cancerous diseases. Canonical WNT/β-catenin signaling cascade is aberrantly activated in hereditary colorectal cancer and various types of sporadic cancers owing to genetic alterations in the APC, AXIN2, CTNNB1, RNF43, RSPO2 and RSPO3 genes, and also in hereditary osteoblastic diseases owing to SOST and LRP5 mutations (red boxes). The WNT/β-catenin signaling cascade is downergulated in intellectual disability syndrome owing to CTNNB1 loss-of-function mutations, in familial exudative vitreoretinopathy owing to loss-of-function mutations in the FZD4 and LRP5 genes and in osteoporosis-associated syndromes owing to LRP5, LRP6 and WNT1 loss-of-function mutations (open box). By contrast, non-canonical WNT/RTK signaling cascade is aberrantly activated in B-cell leukemia and solid tumors as a result of ROR1 upregulation (blue box). Non-canonical WNT/PCP signaling cascade is dysregulated in PCP-related hereditary diseases, such as autism, epilepsy, neural tube defects and Robinow syndrome owing to mutations in the CELSR1, DVL1, DVL2, DVL3, FZD6, PRICKLE1, PRICKLE2, ROR2, VANGL1, VANGL2 and WNT5A genes (open boxes). Genetic alterations in the WNT signaling molecules affect multiple WNT signaling cascades. For example, RNF43, RSPO2 and RSPO3 alterations activate WNT/β-catenin and other WNT signaling cascades, whereas loss-of-function LRP5 mutations inactivate the WNT/β-catenin signaling cascade and reciprocally activate the WNT/PCP signaling cascade. PCP, planar cell polarity; RTK, receptor tyrosine kinase.

Next-generation sequencing that produces huge amounts of genomic, epigenomic and transcriptomic data (17–20) and cell-based technologies, such as induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) (21–23), direct reprogramming to somatic stem/progenitor cells (24) and CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing (25,26), have been elucidating the mechanistic involvement of the WNT signaling cascades in human pathophysiology and opening up new therapeutics avenues for human diseases.

We carried out the Human WNTome and Post-WNTome Projects to construct a platform of medical WNT research in the late 1990s and early 2000s (1,2,7 and references therein). Despite amazing progress in basic studies of WNT signaling and genetics, there is still a huge gap that must be addressed before WNT-targeted therapy for patients can be applied. A mechanistic understanding of the pathogenesis of WNT-related diseases is necessary to address the gap between basic research and clinical application. Here, human genetics and genomics of WNT-related diseases will be reviewed (Table I), and then, clinical application of WNT signaling-targeted therapy using small-molecule compounds, human/humanized monoclonal antibodies (mAb) and chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells (CAR-T) will be discussed.

Table I.

Germline and somatic alterations in WNT signaling molecules in human diseases.

| Gene | Function | Germline | Somatic | (Refs.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| APC | β-catenin degradation | Hereditary colorectal cancer | Cancer | (27) |

| AXIN2 | β-catenin degradation | Hereditary colorectal cancer | Cancer | (28,30) |

| CELSR1 | Core PCP component | Neural tube defects | (115) | |

| CTNNB1 | β-catenin | Intellectual disability syndrome | Cancer | (30,50) |

| DAPLE | β-catenin degradation | Hydrocephalus | (170) | |

| DVL1 | Intracellular WNT signaling | Robinow syndrome | (120) | |

| DVL2 | Intracellular WNT signaling | Neural tube defects | (115) | |

| DVL3 | Intracellular WNT signaling | Robinow syndrome | (120) | |

| FZD4 | WNT receptor | Exudative vitreoretinopathy | (91) | |

| FZD5 | WNT receptor | Ocular coloboma | (166) | |

| FZD6 | WNT receptor | Nail dysplasia | (167) | |

| Neural tube defects | (115) | |||

| LRP5 | Canonical WNT receptor | Exudative vitreoretinopathy | (91) | |

| Osteoporosis-pseudoglioma syndrome | (74) | |||

| High-bone-mass diseases | (71) | |||

| LRP6 | Canonical WNT receptor | Osteoporosis and early-onset coronary artery disease | (75) | |

| Neural tube defects | (115) | |||

| Selective tooth agenesis 7 | (163) | |||

| NDP | FZD4 ligand | Exudative vitreoretinopathy | (91) | |

| PORCN | WNT palmitoleoylation | Focal dermal hypoplasia | (165) | |

| PRICKLE1 | Core PCP component | Epilepsy | (117) | |

| Neural tube defects | (115) | |||

| PRICKLE2 | Core PCP component | Autism | (119) | |

| Epilepsy | (118) | |||

| RNF43 | FZD ubiquitination | Hereditary colorectal cancer | Cancer | (29,31) |

| ROR2 | Non-canonical WNT receptor | Brachydactyly type B1 | (128) | |

| Robinow syndrome | (127) | |||

| RSPO1 | RNF43/ZNRF3 antagonist | Palmoplantar hyperkeratosis with skin squamous cell carcinoma and sex reversal | (168) | |

| RSPO2 | RNF43/ZNRF3 antagonist | Cancer | (32) | |

| RSPO3 | RNF43/ZNRF3 antagonist | Cancer | (32) | |

| RSPO4 | RNF43/ZNRF3 antagonist | Congenital anonychia | (169) | |

| SFRP4 | WNT antagonist | Pyle disease | (76) | |

| SOST | WNT-LRP5/6 antagonist | Craniodiaphyseal dysplasia | (68) | |

| Sclerosteosis | (69) | |||

| van Buchem disease | (70) | |||

| VANGL1 | Core PCP component | Neural tube defects | (115) | |

| VANGL2 | Core PCP component | Neural tube defects | (115) | |

| WNT1 | WNT ligand | Osteogenesis imperfecta | (73) | |

| Osteoporosis | (73) | |||

| WNT3 | WNT ligand | Tetra-amelia syndrome | (155) | |

| WNT4 | WNT ligand | Mullerian aplasia and hyperandrogenism | (157) | |

| SERKAL syndrome | (158) | |||

| WNT5A | WNT ligand | Robinow syndrome | (126) | |

| WNT7A | WNT ligand | Fuhrmann syndrome | (156) | |

| WNT10A | WNT ligand | Odonto-onycho-dermal dysplasia | (160) | |

| Selective tooth agenesis 4 | (161) | |||

| WNT10B | WNT ligand | Selective tooth agenesis 8 | (162) |

2. Hereditary colorectal cancer and various types of sporadic cancers

Germline mutations in the APC gene occur in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis, which is characterized by innumerable colorectal adenomas and predisposition to colorectal cancer (27), whereas germline mutations in the AXIN2 and RNF43 genes occur in patients with oligodontia-colorectal cancer syndrome (28) and sessile serrated polyposis cancer syndrome (29), respectively. Hereditary colorectal cancer is caused by loss-of-function mutations in the APC, AXIN2 and RNF43 genes (Fig. 2).

Somatic APC mutations preferentially occur in non-hypermutated or conventional colorectal cancers, and somatic AXIN2 and RNF43 mutations preferentially occur in hypermutated or microsatellite-unstable colorectal cancers (30,31). Gain-of-function mutations in the CTNNB1 gene encoding β-catenin (S33C, S37F/Y, T41A or S45F/P), EIF3E-RSPO2 fusions and PTPRK-RSPO3 fusions also occur in sporadic colorectal cancers (31,32). Loss-of-function APC mutations, gain-of-function CTNNB1 mutations or loss-of-function RNF43 or ZNRF3 mutations have also been reported in breast cancer (33), gastric cancer (34), hepatocellular carcinoma (35), lung cancer (36), pancreatic cancer (37), prostate cancer (38) and uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma (39). Various types of human cancers are driven by somatic alterations in the canonical WNT signaling molecules, such as APC, AXIN2, β-catenin, RNF43, RSPO2 and RSPO3 (Fig. 2).

In the adult intestine, WNT2B and WNT3 are secreted from pericryptal cells and Paneth cells, respectively, and transduce canonical WNT signaling through FZD7 for the maintenance of crypt base columnar (CBC) stem cells (40,41). Binding of canonical WNTs to the FZD and LRP5/6 receptors induces formation of the FZD-Dishevelled-AXIN-LRP5/6 complex and release of β-catenin from its degradation complex consisting of APC, AXIN, casein kinase 1 (CK1) and glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β), which results in nuclear translocation of stabilized β-catenin and subsequent transcriptional activation of TCF/LEF target genes, such as AXIN2, cyclin D1 (CCND1), FZD7 and c-Myc (MYC) (Fig. 3). Gain-of-function mutations in the CTNNB1 gene, as well as loss-of-function mutations in the APC and AXIN2 genes, activate the canonical WNT/β-catenin signaling cascade that regulates self-renewal, survival, proliferation and differentiation of tumor cells.

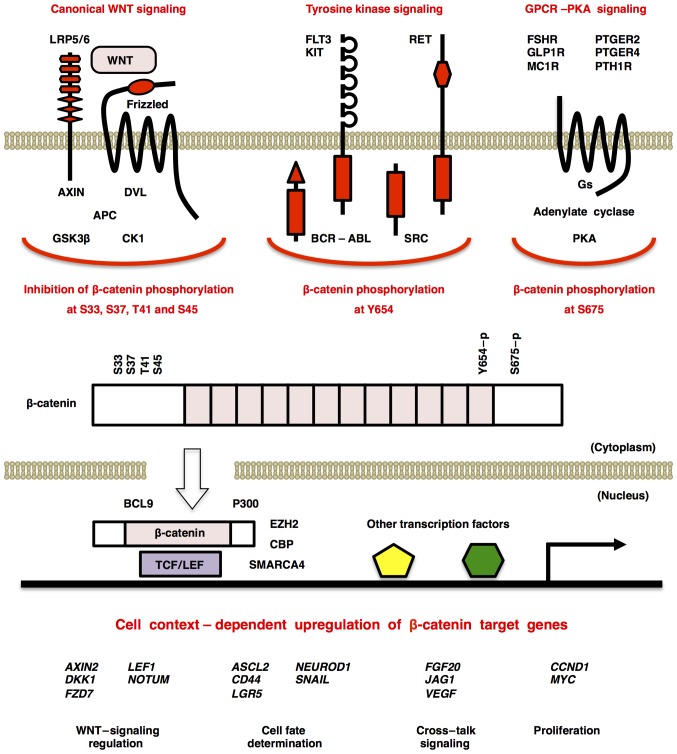

Figure 3.

β-catenin at the crossroad of WNT, tyrosine kinase and GPCR-cAMP-PKA signaling cascades. WNT/β-catenin signaling activation induces stabilization and nuclear translocation of β-catenin and upregulation of β-catenin-TCF/LEF target genes. By contrast, activation of BCR-ABL, FLT3, KIT, SRC or RET tyrosine kinases and GPCR-mediated PKA activation induce β-catenin phosphorylation at Y654 and S675, respectively, which also promotes nuclear translocation of β-catenin and β-catenin-dependent transcription. FSHR (275), GLP1R (276), MC1R (277), PTGER2/EP2 (278,279), PTGER4/EP4 (278,280) and PTH1R (281) are GPCRs that are reported to induce cAMP-dependent PKA activation and subsequent β-catenin activation. AXIN2, CCND1, DKK1, FGF20, FZD7, JAG1, MYC, NEUROD1 and NOTUM are representative targets of the WNT/β-catenin signaling cascade; however, β-catenin target genes are context-dependently upregulated owing to additional transcriptional regulation by the tyrosine kinase and PKA signaling cascades. GPCR, G protein-coupled receptor; PKA, protein kinase A, DKK1, Dickkopf-related protein 1.

RNF43 and ZNRF3 are transmembrane-type E3-ubiquitin ligases that downregulate cell-surface FZD receptors through ubiquitylation and attenuate canonical and non-canonical WNT signaling, whereas RSPO2 and RSPO3 are RNF43/ZNRF3 ligands that de-repress FZD receptors from RNF43/ZNRF3-mediated degradation and enhance WNT signaling (3,42). Loss-of-function mutations in the RNF43 and ZNRF3 genes, as well as EIF3E-RSPO2 and PTPRK-RSPO3 fusions, potentiate the WNT/β-catenin signaling cascade and β-catenin-independent WNT signaling cascades (Fig. 4).

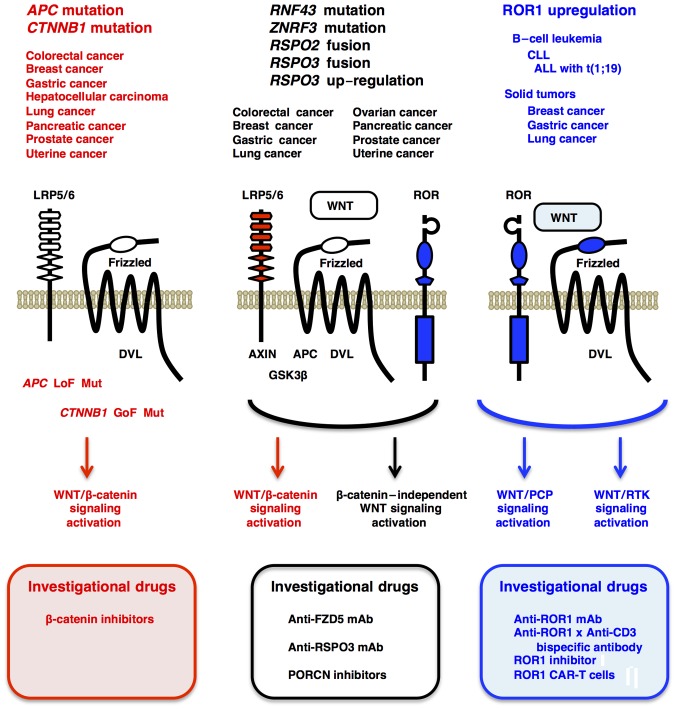

Figure 4.

Mutations, downstream signaling and therapeutics of WNT-related human cancers. (Left) Loss-of-function APC mutations and gain-of-function CTNNB1 mutations in human cancers, such as colorectal cancer, breast cancer and uterine cancer (uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma), lead to ligand-independent activation of the WNT/β-catenin signaling cascade, which can be treated with β-catenin inhibitors in preclinical model animal experiments. (Middle) Loss-of-function RNF43 or ZNRF3 mutations, RSPO2/3 fusions and RSPO3 upregulation in colorectal cancer, breast cancer, pancreatic cancer and other cancers activate the WNT/β-catenin signaling cascade as well as β-catenin-independent WNT signaling cascades, such as WNT/STOP and WNT/PCP signaling cascades. This type of cancers can be treated with anti-FZD5 mAb, anti-RSPO3 mAb or PORCN inhibitors. (Right) ROR1 upregulation in B-cell leukemia and solid tumors gives rise to WNT/PCP and WNT/RTK signaling activation, which can be treated with anti-ROR1 mAb, anti-ROR1 × anti-CD3 bispecific antibodies, ROR1 inhibitor and ROR1 CAR-T cells. PCP, planar cell polarity; ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; CAR-T, chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; GoF, gain-of-function; LoF, loss-of-function; mAb, monoclonal antibody; Mut, mutation; RTK, receptor tyrosine kinase; STOP, stabilization of proteins; PORCN, porcupine.

APC and CTNNB1 alterations in conventional colorectal cancers induce WNT-independent activation of the β-catenin signaling cascade, whereas RNF43, RSPO2 and RSPO3 alterations in non-conventional colorectal cancers can activate the WNT/β-catenin and other WNT signaling cascades (Fig. 4). To target different classes of genetic alterations in the WNT signaling molecules, several types of anti-WNT signaling therapeutics have been developed and are described later.

3. Intellectual disability syndrome, Alzheimer's disease and bipolar disorder

β-catenin, encoded by the CTNNB1 gene, is a scaffold protein that interacts with WNT signaling components (including APC, AXIN, BCL9 and TCF/LEF), adhesion molecules (such as E-cadherin, N-cadherin and α-catenin) and epigenetic/transcriptional regulators (for example, CBP, p300, EZH2 and SMARCA4/BRG1) (43,44). Cadherin-bound β-catenin is stable and involved in the maintenance of cell-cell adhesion, whereas cytoplasmic free β-catenin is degraded in the proteasome through priming phosphorylation at S45 by CK1, following phosphorylation at S33, S37 and T41 by GSK3β, and subsequent poly-ubiquitylation at K19 by E3 ubiquitin ligase (45). Canonical WNT signaling activation leads to stabilization and nuclear translocation of cytoplasmic β-catenin as mentioned above (Fig. 3). By contrast, activation of BCR-ABL, FLT3, KIT, SRC and RET tyrosine kinases (43,46–48) leads to release and nuclear translocation of cadherin-bound β-catenin through phosphorylation at Y654 and subsequent PKA-dependent phosphorylation at S675 (49). β-catenin is located at the crossroad of canonical WNT, tyrosine kinase and GPCR-cAMP-PKA signaling cascades for the regulation of cell adhesion, cell fate and cell functions (Fig. 3).

De novo loss-of-function mutations in the CTNNB1 gene (for example, Q309X, S425fs and R515X) have been reported in patients with intellectual disability and other common features, such as microcephaly, speech disorder, truncal hypotonia and distal hypertonia (50). A loss-of-function CTNNB1 mutation (P706fs) has also been reported in a patient presenting with intellectual disability, autism-like features, exudative vitreoretinopathy and lipomyelomeningocele (a closed form of neural tube defect) (51). WNT/β-catenin signals promote symmetrical and asymmetrical divisions of neural stem cells for their expansion and generation of neural progenitor cells, respectively, regulate proliferation and differentiation of neural progenitor cells in a context-dependent manner, and thus, maintain synaptic function (52). Therefore, loss-of-function mutations in the CTNNB1 gene give rise to intellectual disability syndrome through impaired expansion and differentiation of neural stem/progenitor cells during embryonic, perinatal and postnatal brain development (Fig. 2).

WNT/β-catenin signals are also necessary for adult neurogenesis or neuronal plasticity and synaptic maintenance (53). As WNT/β-catenin signaling induces the expression of the NeuroD1 transcription factor to promote neurogenesis in the hippocampus and olfactory bulb, Dickkopf-related protein 1 (Dkk1) upregulation in the hippocampus of SAMP8 mice is associated with decreased canonical WNT signaling and neuronal loss (54) and Wnt3 downregulation in the olfactory bulb of streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats is associated with impaired odor discrimination, cognitive dysfunction and increased anxiety (55). Dkk1 induction in the hippocampus of iDkk1 transgenic mice causes synaptic loss and memory defects through canonical WNT/β-catenin signaling inhibition and non-canonical WNT/RhoA-ROCK signaling activation, whereas Dkk1 repression reverts the Alzheimer's disease-like phenotypes in the iDkk1 transgenic mice (56). WNT/β-catenin signaling also induces expression of the REST silencing factor to protect neurons from oxidative stress and aggregated misfolded protein in aging brains; however, neuronal nuclear REST is lost in patients with Alzheimer's disease, frontotemporal dementia and Lewy-body dementia (57). By contrast, impaired canonical WNT/β-catenin signaling is involved in the pathogenesis of bipolar disorder through defective resilience to chronic stress (58). WNT7B downregulation in CXCR4+ neural progenitor cells derived from bipolar-disease iPSCs is associated with a reduced proliferation potential, and canonical WNT/β-catenin signaling activation using GSK3 inhibitor (CHIR99021) restores the proliferation deficits (59), which explains the rationale why another GSK3 inhibitor, lithium, is utilized for the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder. Together, these facts indicate that impaired WNT/β-catenin signaling is involved in the pathogenesis of neuropsychiatric diseases, such as Alzheimer's disease and bipolar disorder.

4. Bone diseases

Bone homeostasis is maintained by mesenchymal stem cells that generate osteoblasts, osteoblast-derived osteocytes and other types of mesenchymal cells, as well as hematopoietic stem cells that give rise to monocytes, monocyte-derived osteoclasts and other types of blood cells. Canonical WNT/β-catenin signaling through Frizzled and LRP5/6 receptors promotes RUNX2-dependent osteoblastic differentiation of mesenchymal stem or progenitor cells (60,61). Canonical WNT signaling in osteoblast-lineage cells upregulates BMP2, and then BMP2 signaling through BMPR1A upregulates WNT7A/10B to synergistically potentiate osteoblastogenesis and bone formation (62,63). BMP2 signaling in osteoblast-lineage cells also upregulates the canonical WNT inhibitors DKK1 and sclerostin (SOST) to turn off canonical WNT signaling for the fine-tuning of bone mass (64,65). By contrast, parathyroid hormone (PTH) signaling through PTH1R in osteoblast-lineage cells downregulates SOST to promote bone formation and upregulates RANK ligand (RANKL) to induce osteoclastic differentiation of osteoclast progenitors (66). Non-canonical WNT5A signaling through ROR2 in osteoclast progenitors upregulates the RANK receptor to promote RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis and bone resorption (67). WNT signaling cascades crosstalk with BMP, cytokine and PTH signaling cascades in a context-dependent manner to precisely control the balance of bone formation and resorption.

Aberrant canonical WNT signaling activation gives rise to bone-formation phenotypes (Fig. 2). Loss-of-function mutation or deletion in the SOST gene occurs in patients with sclerosing skeletal dysplasias, such as craniodiaphyseal dysplasia (68), sclerosteosis (69) and van Buchem disease (70). Heterozygous mutations in the N-terminal signal peptide of SOST (V21M/L) are detected in patients with craniodiaphyseal dysplasia, the most severe form of SOST-defective disease, which is characterized by massive hyperostosis with leonine face and craniofacial foraminal stenosis. Homozygous missense mutation (Q24X) and enhancer deletion in the SOST gene are detected in patients with sclerosteosis and van Buchem disease, respectively, which are characterized by gigantism, facial palsy and hearing loss. Sclerosteosis is a severe form of SOST-defective disease frequently presenting with syndactyly, whereas van Buchem disease is a mild form of SOST-defective disease without syndactyly. By contrast, LRP5 mutations in the first β-propeller domain (for example, D111Y, G171R, A214T and A242T) have been reported in patients with high-bone-mass diseases, such as van Buchem disease type 2, endosteal hyperostosis and osteopetrosis type 1 (71). LRP5 mutations in the first β-propeller domain are gain-of-function mutations, as SOST and DKK1 bind to the first β-propeller domain of LRP5 to inhibit canonical WNT signaling (64,65). Loss-of-function SOST mutations and gain-of-function LRP5 mutations cause bone-formation phenotypes in patients with sclerosing skeletal dysplasias and high-bone-mass diseases, respectively.

Defects in canonical WNT signaling and/or aberrant activation of non-canonical WNT signaling cause bone-resorption phenotypes (Fig. 2). Osteoporosis is characterized by low bone mineral density (BMD), deteriorated bone quality and susceptibility to fracture, whereas osteogenesis imperfecta is a prenatal-onset osteoporotic disease characterized by brittle bones (72,73). Homozygous loss-of-function mutations in the LRP5 gene (such as R428X, E485X, D490fs and D718X) have been detected in patients with osteoporosis-pseudoglioma syndrome, which is characterized by osteoporosis and eye phenotypes (exudative vitreoretinopathy and susceptibility to blindness) (74). Heterozygous loss-of-function mutation in the LRP6 gene (R611C) was found in patients with familial osteoporosis and early-onset coronary artery disease (75). Heterozygous loss-of-function WNT1 mutation (C218G) occurs in patients with early-onset osteoporosis, and homozygous loss-of-function WNT1 mutation (S295X) occurs in patients with osteogenesis imperfecta (73). By contrast, homozygous loss-of-function SFRP4 mutations (V161fs, D167fs and R232X) give rise to Pyle disease, which is characterized by limb malformation, cortical-bone thinning and fracture, through enhanced non-canonical WNT5A signaling and osteoclastogenesis (76). In addition to the rare mutations mentioned above, BMD-associated single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the CTNNB1, LRP5, SOST, WNT4 and WNT16 loci are also associated with slightly increased fracture risk (77). As rare mutations and common variations in the canonical WNT/β-catenin signaling molecules are involved in the pathogenesis of osteoporosis, pro-WNT/β-catenin signaling therapy is a rational option for the treatment of patients with osteoporosis.

5. Vascular diseases

Vascular development and homeostasis are coordinated by a network of VEGF, FGF, Notch, angiopoietin (ANGPT), WNT and other signaling cascades (78,79). Endothelial cells are involved in the maintenance of blood and lymphatic vessels as well as the support of somatic stem cells, such as gastric stem cells, hematopoietic stem cells, liver stem cells, mesenchymal stem cells and neural stem cells (80,81). VEGF signaling through VEGFR2 and FGF2 signaling through FGFR1/2 directly promote proliferation and migration of endothelial tip cells during angiogenic sprouting (82–84), and then, DLL and JAG signaling through Notch directly promote stabilization and elongation of endothelial stalk cells (85–87). ANGPT1 signaling through TIE2 in endothelial cells promotes vascular maturation and stability, whereas ANGPT2 signaling through TIE2 promotes vascular de-stabilization through ANGPT1 signaling inhibition (88). Aberrant canonical WNT/β-catenin signaling activation in cancer cells induces VEGF upregulation (89), which leads to unstable and leaky tumor angiogenesis. By contrast, non-canonical Wnt5a/PCP signaling downregulates Cskn1 and Bax to promote endothelial proliferation and survival, respectively, and upregulates Tie2 to promote vascular maturation and stability (90). Canonical and non-canonical WNT signaling cascades are directly or indirectly involved in vascular pathophysiology.

Familial exudative vitreoretinopathy is a hereditary disorder that is characterized by partial vascular agenesis, neovascularization and exudation in the retina and susceptibility to blindness owing to retinal detachment (91). We cloned and characterized the human FZD4 gene in 1999 (92), and since then germline mutations in the FZD4 gene (such as C45Y, Y58C, W226X and W496X) have been reported in patients with exudative vitreoretinopathy (93–95) (Fig. 2). C45Y and Y58C FZD4 are missense mutations in the Frizzled-like domain that abolish NDP binding to FZD4, and W226X and W496X FZD4 are loss-of-function truncation mutations. NDP and LRP5 mutations have also been reported in patients with exudative vitreoretinopathy (96,97). Loss-of-function LRP5 mutations occur in patients with osteoporosis-pseudoglioma syndrome and present with similar eye phenotypes (74), and a loss-of-function CTNNB1 mutation occurs in a patient with intellectual disability syndrome complicated with exudative vitreoretinopathy (51) as mentioned above. NDP is a secreted protein that binds to the extracellular Frizzled-like domain of FZD4 and activates the β-catenin signaling cascade through FZD4 and LRP5 receptors similar to canonical WNT ligands. Loss-of-function mutations in the NDP, FZD4, LRP5 and CTNNB1 genes in patients with exudative vitreoretinopathy indicate involvement of the NDP/β-catenin signaling defect in the pathogenesis of exudative vitreoretinopathy.

Ndp and Wnt7a/b are required for vascular development in the mouse retina and central nervous system, respectively (97,98), and lithium chloride treatment that stabilizes β-catenin through GSK3 inhibition upregulates the Vegf level to ameliorate retinal vascular phenotypes in an Lrp5 knockout mouse model of familial exudative vitreoretinopathy (99). By contrast, Fzd4 signaling is required for retinal vascular stabilization and maturation (100), and WNT5A induces dissociation of Gα12/13 from FZD4 to promote p115RhoGEF-mediated activation of the RHO signaling cascade in endothelial cells (101). As canonical WNT or NDP signaling to the β-catenin cascade can promote angiogenic sprouting indirectly through transcriptional upregulation of VEGF and FGF family ligands and non-canonical WNT signaling through FZD4 can promote retinal vascular stability and maturation, fine-tuning of the canonical and non-canonical WNT signaling cascade may be necessary for the treatment of patients with familial exudative vitreoretinopathy.

6. Human diseases related to core PCP components

PCP is defined as cellular polarity within the epithelial plane perpendicular to the cellular apico-basal axis (7). The Drosophila PCP pathway coordinates orientation of sensory bristles and hairs and the rotation pattern of ommatidia (102,103), whereas the vertebrate PCP pathway regulates orientation of sensory hair cells in the inner ear, collective cell movements during embryogenesis (convergent extension movements during gastrulation and neural tube closure during neurulation) (104–107), directional movements of neural crest cells and tumor invasion (108–111). The PCP pathway is categorized as the Frizzled-Flamingo-dependent core PCP branch and Fat-Dachsous-dependent alternative or parallel PCP branch (112,113).

Flamingo (Drosophila ortholog of human CELSR1, CELSR2 and CELSR3), Frizzled (including FZD3, FZD6 and FZD7), Dishevelled (DVL1, DVL2 and DVL3), Prickle (PRICKLE1 and PRICKLE2) and Van Gogh/Vang (VANGL1 and VANGL2) are core PCP components that constitute the Flamingo-mediated interaction of the Flamingo-Frizzled-Dishevelled and Flamingo-Vang-Prickle complexes on the opposite sides of neighboring cells. The mammalian core PCP pathway overlaps with non-canonical WNT signaling through FZDs and DVLs to the Rac-JNK and RhoA-ROCK signaling cascades (Fig. 1). We entered the PCP research field through molecular cloning and characterization of novel human PCP genes, such as FZD3, FZD6, FZD7 and VANGL1, from 1998 to 2002 as fruits of the human WNTome project, and identification and characterization of PRICKLE1 and PRICKLE2 in 2003 as fruits of the Post-WNTome project (114). Dr Kibar's group opened up a new avenue for PCP genetics related to neural tube defects, and since then germline or de novo alterations in the core PCP components have been reported in human diseases, such as neural tube defects (115,116), epilepsy (117,118), autism (118,119) and Robinow syndrome (120).

Neural tube defects, including anencephaly, craniorachischisis and myelomeningocele (open spina bifida), are the second most common birth defects in humans, and they occur in ~1/1,000 established pregnancies (121). As the neural tube is generated through orchestrated extension, upward bending and fusion of the neural plate during embryogenesis, failure of the collective movement of neural crest precursors results in neural tube defects (122). Environmental factors, such as teratogenic chemicals, and no less than 200 genetic factors are involved in the susceptibility to neural tube defects (123). Mutations in the WNT signaling related genes, such as CELSR1, DVL2, FZD6, LRP6, PRICKLE1, VANGL1 and VANGL2, occur in patients with neural tube defects (115). CELSR1, DVL2, FZD6, PRICKLE1, VANGL1 and VANGL2 are core PCP components that are involved in non-canonical WNT signaling cascades, whereas LRP6 is a canonical WNT receptor (Table I). LRP6 mutants (Y306H, Y373C and V1386L) repress Wnt3a-induced TCF/LEF-dependent transcription but potentiate Wnt5a-induced JNK-dependent transcription (116). In addition, a patient with intellectual disability syndrome caused by a loss-of-function CTNNB1 mutation presented with exudative vitreoretinopathy and neural tube defect as mentioned above (51). Mutations in the core PCP signaling molecules, as well as loss-of-function mutations in the canonical WNT/β-catenin signaling molecules, give rise to neural tube defects.

The PRICKLE1 and PRICKLE2 genes are also mutated in patients with epilepsy and autism. Epilepsy is characterized by recurrent seizures, whereas autism is characterized by deficits in social interactions, communication and flexible behavior. Homozygous PRICKLE1 mutation (R104Q) occurs in familial cases of progressive myoclonus epilepsy with early-onset ataxia (117). Heterozygous PRICKLE1 mutations (R104Q, R144H and Y472H) and a PRICKLE2 mutation (R148H) occur in sporadic cases of progressive myoclonus epilepsy (118), whereas heterozygous PRICKLE2 mutations (E8Q and V153I) occur in autistic patients (119). Deletion of the PRICKLE2 gene is detected in patients with 3p14 microdeletion syndrome, one type of which is characterized by autism, epilepsy and developmental delay and another type of which is characterized by autism, intellectual disability and language disorder (118,124). By contrast, loss-of-function mutation of the CTNNB1 gene is reported in a patient with autism, neural tube defect, intellectual disability and exudative vitreoretinopathy as mentioned above (51). As the development and maintenance of neural tissues are orchestrated by the spatiotemporal fine-tuning of the canonical and non-canonical WNT signaling cascades, genetic alterations in WNT signaling molecules cause overlapping neuropsychiatric disorders, such as autism, epilepsy and intellectual disability.

Robinow syndrome is a hereditary disorder that presents with common features, such as brachydactyly, frontal bossing, genital hypoplasia, hemivertebra, hypertelorism and mesomelic limb shortening (125). In addition to DVL1 and DVL3 mutations in patients with the autosomal dominant form of Robinow syndrome (120), WNT5A and ROR2 mutations occur in patients with autosomal dominant and autosomal recessive forms of Robinow syndrome, respectively (126,127). By contrast, autosomal dominant ROR2 mutations occur in patients with brachydactyly type B1 (128). As WNT5A signaling through the ROR2 receptor activates DVL1/3-mediated RHO-ROCK and RAC1-JNK signaling cascades to regulate cell polarity and directional migration (129–132), loss-of-function mutations in the WNT5A, ROR2, DVL1 and DVL3 genes give rise to Robinow syndrome through impaired non-canonical WNT signaling (Fig. 2). However, osteosclerotic phenotypes in a subset of patients with Robinow syndrome (133) suggest reciprocal WNT/β-catenin signaling activation in the bone, and Robinow syndrome-like phenotypes in mice with null and hypomorphic Prickle1 alleles (134) suggest the involvement of core PCP components other than DVLs in Robinow syndrome. Signaling mechanisms and Robinow syndrome genes should be further investigated.

WNT/PCP or WNT5A/ROR/Frizzled signaling promotes invasion, survival and therapeutic resistance of human cancers (135–141), although WNT5A or non-canonical WNT/Ca2+ signaling is context-dependently involved in tumor suppression (142–144). ROR1 is preferentially upregulated in B-cell leukemia, such as chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) (145) and t(1;19) acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) (146). WNT5A-dependent oligomerization of ROR1 and ROR2 on CLL cells induces recruitment of the guanine exchange factors ARHGEF1, ARHGEF2 and ARHGEF6 and subsequent activation of RhoA and Rac1 to promote chemotaxis and proliferation, respectively (147). ROR1 is also upregulated in breast cancer, gastric cancer and lung cancer, and ROR1 phosphorylation by MET and SRC promote tumor proliferation and invasion (148–150). ROR1 interacts with TCL1A (TCL1) to activate AKT in a mouse model of CLL (151); ROR1 interacts with HER3 and LLGL2 in breast cancer cells to inhibit STK4 (MST1) through K59 methylation, which leads to transcriptional upregulation of YAP/TAZ-target genes (150); and ROR1 interacts with caveolae components in lung cancer cells to promote survival and resistance to EGFR inhibitors through MET- or IGF1R-dependent PI3K-AKT signaling activation (152). ROR1 upregulation in B-cell leukemias and solid tumors promote malignant phenotypes through ROR1 phosphorylation and activation of WNT/PCP and WNT/RTK signaling cascades (Fig. 4). By contrast, ROR2 is upregulated in invasive melanoma (153), and WNT5A/ROR2 signaling induces recruitment and activation of SRC to promote metastasis (154). WNT5A induces de-palmitoylation of MCAM adhesion molecules and subsequently polarizes localization of MCAM and CD44 to promote directional movement and invasion of melanoma cells (110). These facts clearly indicate that the WNT/PCP and WNT/RTK signaling cascades, as well as WNT/β-catenin signaling cascade, drive human carcinogenesis (Fig. 4).

7. Other genetic diseases

WNT3 and WNT7A mutations are reported in patients with tetra-amelia syndrome and Fuhrmann syndrome, respectively (155,156) which are characterized by congenital limb malformations. Heterozygous E216G WNT4 mutation causes mullerian aplasia and hyperandrogenism (157) whereas homozygous A114V WNT4 mutation causes SERKAL syndrome presenting female-to-male sex reversal and dysgenesis of kidneys, adrenal glands and lungs (158). We cloned and characterized human WNT6 and WNT10A in 2001 (159), and then, another group found a homozygous WNT10A E233X mutation in patients with odonto-onycho-dermal dysplasia characterized by severe hypodontia, onychodysplasia and keratoderma in 2007 (160). WNT10A, WNT10B and LRP6 mutations occur in patients with selective tooth agenesis (161–163). By contrast, as porcupine (PORCN) is an O-acyltransferase that is involved in palmitoleoylation and subsequent secretion of WNT ligands (164), loss-of-function PORCN mutations lead to focal dermal hypoplasia characterized by patchy hypoplastic skin and other malformations (165).

In addition to FZD4 and FZD6 mutations in patients with exudative vitreoretinopathy (91) and neural tube defects (115), respectively, FZD5 mutations in patients with ocular coloboma (166) and FZD6 mutations in patients with nail dysplasia (167) have been reported. Loss-of-function RSPO1 mutations cause palmoplantar hyperkeratosis with skin squamous cell carcinoma and sex reversal (168), whereas RSPO4 missense mutations occur in patients with congenital anonychia (169).

Heterozygous Ser1591fs mutation in the DAPLE (CCDC88C) gene has been reported in a patient with hydrocephalus (170). Wild-type DAPLE protein, containing the FZD-binding and Gα-binding/activation motifs in its C-terminal region, assembles FZD7 receptor and Gαi protein to transduce non-canonical WNT5A/Rac1 and PI3K-AKT signaling cascades and inhibit the canonical WNT/β-catenin signaling cascade (171), although the FZD7 receptor is involved in canonical WNT/β-catenin signaling activation in intestinal stem cells (41). As the Ser1591fs DAPLE mutant in a hydrocephalus patient is resistant to nonsense-mediated mRNA decay (170) and lacks the FZD-binding and Gα-binding/activation motifs, the truncating DAPLE mutation is predicted to impair non-canonical WNT/Rac1 and PI3K-AKT signaling cascades.

8. Therapeutics targeting WNT signaling cascades

Development of therapeutics that inhibit the WNT/β-catenin signaling cascade is a topic of great interest in the field of clinical oncology and medicinal chemistry (172–175). By contrast, as aberrant activation and inhibition of WNT signaling cascades are involved in the pathogenesis of cancer and non-cancerous diseases (Table I), therapeutics that inhibit or potentiate canonical or non-canonical WNT signaling cascades are necessary for the future implementation of genome-based medicine for human diseases. WNT-targeted therapy will be discussed in this section with emphases on PORCN, RSPO3, WNT ligands, FZD receptors, ROR1 receptor, tankyrase and β-catenin as targets for anti-WNT signaling therapy (Table II) and DKK1, SOST and GSK3β as targets for pro-WNT signaling therapy (Table III).

Table II.

Anti-WNT signaling therapeutics.

| Target | Mechanism of action | Drug | Stage of drug development | Disease | (Refs.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WNT | PORCN inhibitor | ETC-159 | Phase I | Cancer | (177) |

| IWP-2 | Preclinical | Cancer | (178) | ||

| LGK974 | Phase I | Cancer | (179) | ||

| WNT-C59 | Preclinical | Cancer | (180) | ||

| Preclinical | Cardiac fibrosis | (184) | |||

| Preclinical | Kidney fibrosis | (185) | |||

| WNT | FZD8-binding WNT trap | Ipafricept | Phase I | Cancer | (210) |

| RSPO3 | Anti-RSPO3 mAb | OMP-131R10 | Phase I | Cancer | (186) |

| FZDs | Anti-FZD1/2/5/7/8 mAb | Vantictumab | Phase I | Cancer | (208) |

| FZD5 | Anti-FZD5 mAb | IgG-2919 | Preclinical | Cancer | (198) |

| FZD10 | Anti-FZD10 mAb | OTSA101 | Phase I (terminated) | Cancer | (209) |

| ROR1 | ROR1 inhibitor | KAN 0439834 | Preclinical | Cancer | (216) |

| Anti-ROR1 mAb | Cirmtuzumab | Phase I | Cancer | (147) | |

| Anti-ROR1 × anti-CD3 | ROR1-CD3-DART | Preclinical | Cancer | (218) | |

| bispecific mAb | APVO425 | Preclinical | Cancer | (219) | |

| ROR1 CAR-T cells | ROR1R-CAR-T | Preclinical | Cancer | (220) | |

| AXIN | Tankyrase inhibitor | AZ1366 | Preclinical | Cancer | (239) |

| G007-LK | Preclinical | Cancer | (240) | ||

| NVP-TNKS656 | Preclinical | Cancer | (241) | ||

| XAV939 | Preclinical | Cancer | (243) | ||

| Preclinical | Neuropathic pain | (245) | |||

| β-catenin | Blockade of β-catenin | BC2059 | Preclinical | Cancer | (252) |

| protein-protein-interaction | CGP049090 | Preclinical | Cancer | (253) | |

| CWP232228 | Preclinical | Cancer | (254) | ||

| ICG-001 | Preclinical | Cancer | (255) | ||

| Preclinical | Pulmonary fibrosis | (261) | |||

| Preclinical | CKD | (262) | |||

| LF3 | Preclinical | Cancer | (256) | ||

| MSAB | Preclinical | Cancer | (257) | ||

| PKF115-584 | Preclinical | Cancer | (258) | ||

| PRI-724 | Phase II | Cancer | (259) | ||

| SAH-BCL9 | Preclinical | Cancer | (260) |

CKD, chronic kidney disease; OTSA101, OTSA101-DPTA-90Y; PORCN, porcupine.

Table III.

Pro-WNT signaling therapeutics.

| Target | Mechanism of action | Drug | Stage of drug development | Disease | (Refs.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DKK1 | Anti-DKK1 mAb | BHQ880 | Phase II | Cancer | (226) |

| DKN-01 | Phase I | Cancer | (227) | ||

| PF-04840082 | Preclinical | Osteoporosis | (228) | ||

| SOST | Anti-SOST mAb | Blosozumab | Phase II | Osteoporosis | (224) |

| BPS804 | Phase II | Osteoporosis | (225) | ||

| Romosozumab | Phase III | Osteoporosis | (223) | ||

| β-catenin | GSK3β inhibitor or | BIO | Reagent (in vitro) | (246) | |

| GSK3 inhibitor | CHIR99021 | Reagent (in vitro) | (247) | ||

| LY2090314 | Reagent (in vitro) | (248) | |||

| TWS119 | Reagent (in vitro) | (249) |

DKK1, Dickkopf-related protein 1; GSK3β, glycogen synthase kinase 3β.

PORCN is an endogenous WNT palmitoleoylase that promotes secretion of WNT family proteins and their interaction with FZD receptors (164), whereas NOTUM is an endogenous WNT de-palmitoleoylase that represses WNT-FZD interaction (176). Small-molecule inhibitors for PORCN and NOTUM are applicable to anti- and pro-WNT signaling therapies, respectively. ETC-159 (ETC-1922159) (177), IWP-2 (178), LGK974 (WNT974) (179) and WNT-C59 (180) are representative PORCN inhibitors that attenuate WNT signaling for in vivo treatment of colorectal cancer with RSPO translocations and pancreatic cancer with RNF43 mutations (181–183) (Fig. 4) as well as non-cancerous diseases, such as cardiac fibrosis (184) and kidney fibrosis (185). By contrast, OMP-131R10 is an anti-RSPO3 mAb that neutralizes RSPO3 to attenuate canonical WNT signaling through ubiquitylation-mediated FZD degradation (186). OMP-131R10 inhibits tumor growth in patient-derived xenograft models of colorectal cancers with RSPO3 fusion or non-small cell lung cancers and ovarian cancers with RSPO3 upregulation (Fig. 4). ETC-159, LGK974 and OMP-131R10 are in clinical trials for the treatment of cancer patients (ClinicalTrials.gov; https://clinical-trials.gov) (Table II).

Between 1996 and 2002, we cloned and characterized human WNT2B, WNT3A, WNT5B, WNT6, WNT7B, WNT8A, WNT9A (WNT14), WNT9B (WNT14B), WNT10A, FZD1, FZD3, FZD4, FZD5, FZD6, FZD7, FZD8 and FZD10 as the major products of the human WNTome project (1,2 and references therein). Some of these WNTs and FZDs are potential targets for cancer therapy (Fig. 4). For example, as WNT2B is upregulated in diffuse-type gastric cancer, pancreatic cancer and nasopharyngeal carcinoma and involved in EMT, invasion and metastasis (187–190), WNT2B shRNAs have been used to inhibit tumorigenesis in mouse model experiments (191,192). FZD6 upregulation in colorectal cancer, neuroblastoma and triple-negative breast cancer is involved in stem-like features, EMT and drug resistance (193–196). Based on FZD5 upregulation in solid tumors, including RNF43-mutated pancreatic cancer (197,198), FZD7 upregulation in breast cancer, colorectal cancer, glioma and hepatocellular carcinoma (199–203) and FZD10 upregulation in breast cancer, colorectal cancer and synovial sarcoma (204–207), anti-FZD5 IgG, anti-FZD7 mAb and anti-FZD10 mAbs have been developed for cancer therapy. Vantictumab (OMP-18R5), initially isolated as an FZD7-binding antibody, is a broad-spectrum anti-FZD mAb that reacts with FZD1, FZD2, FZD5, FZD7 and FZD8 (208), which all belong to the FZD1/2/7 or FZD5/8 subfamily among the FZD family (204). OTSA101-DPTA-90Y is a 90Y-labeled anti-FZD10 mAb (209). By contrast, ipafricept (OMP-54F28) is a fusion protein that consists of the cysteine-rich domain of FZD8 and the Fc domain of immunoglobulin, and it functions as a trap for FZD8-binding WNT proteins (210). Vantictumab and OMP-54F28 are in clinical trials for the treatment of cancer patients (Table II). As the FZD7 receptor on intestinal stem cells, endothelial cells and solid tumors is involved in WNT signaling to the β-catenin, RhoA, Rac1, PI3K and Ca2+ cascades (41,171,211,212), FZD7 blockade gives rise to various effects in a cell context-dependent manner. The effectiveness and adverse effects of anti-FZD mAb drugs may be determined by the selectivity of mAbs and the context-dependent functions of targeted FZDs.

ROR1 is a rational target of cancer therapeutics as ROR1 is upregulated in subsets of B-cell leukemia, breast cancer, gastric cancer and lung cancer but undetectable in most adult tissues except immature B-cells (Fig. 4). In addition, ROR1 is involved in tumor proliferation, invasion and therapeutic resistance as mentioned above (145–152). ROR1, ROR2, NTRK1, NTRK2, NTRK3, MUSK, DDR1 and DDR2 constitute the ROR/NTRK subfamily among the RTKs, whereas small-molecule inhibitors and mAbs are established approaches to target RTKs (213,214). ROR1 is predicted to be a pseudokinase that lacks intrinsic tyrosine kinase activity (215), but ROR1 is phosphorylated by other tyrosine kinases, such as MET and SRC, and activates downstream signaling cascades (148,149). KAN 0439834 is a small-molecule ROR1 inhibitor that dephosphorylates ROR1 in B-cell leukemia, breast cancer and lung cancer and induces a cytotoxic effect on ROR1-expressing tumor cells (216). Cirmtuzumab (UC-961) is a humanized anti-ROR1 mAb that inhibits WNT5A-induced ROR1 signaling through ROR1 dephosphorylation and represses in vivo growth of ROR1-expressing CLL cells (147,217). ROR1-CD3-DART and APVO425 (ES425) are bispecific antibodies consisting of anti-ROR1 and anti-CD3 mAbs that redirect cytotoxic T cells to ROR1-expressing tumor cells (218,219). ROR1 CAR-T cells were also developed for cancer therapy, and the effectiveness and safety of ROR1 CAR-T cells have been demonstrated in rodent as well as non-human primate model experiments (220). Cirmtuzumab is in clinical trials for the treatment of cancer patients (Table II).

SOST and DKK1 are endogenous canonical WNT antagonists that induce direct inhibition of osteoblastogenesis as well as indirect promotion of osteoclastogenesis, and are involved in the pathogenesis of osteoporosis and cancer-associated osteolysis, respectively (64,221,222). As SOST and DKK1 are rational targets of pro-WNT signaling therapy for human diseases, anti-SOST mAbs (romosozumab, blosozumab and BPS804) (223–225), anti-DKK1 mAbs (BHQ880, DKN-01 and PF-04840082) (226–228) and a bispecific antibody against SOST and DKK1 (Hetero-DS) (229) have been developed. Romosozumab, blosozumab and BPS804 are in clinical trials for female postmenopausal patients with decreased BMD, whereas BHQ880 and DKN-01 are in clinical trials for patients with multiple myeloma and other solid tumors, such as cholangiocarcinoma, esophageal cancer and gastric cancer (Table III).

Tankyrases (TNKS1/PARP5A and TNKS2/PARP5B), PARP1, PARP2, TIPARP (PARP7) and other PARPs are ADP-ribosyl transferases belonging to the PARP family (230–232), and ADP-ribosyl transferase inhibitors, such as olaparib, have been developed for cancer therapy (233–235). Tankyrases promote degradation of AXIN1 and AXIN2 through poly-ADP-ribosylation, and tankyrase inhibitors induce AXIN stabilization for canonical WNT/β-catenin signaling inhibition (236–238). AZ1366 (239), G007-LK (240), NVP-TNKS656 (241,242) and XAV939 (243,244) are investigational tankyrase inhibitors that can block canonical WNT/β-catenin signaling in model animal experiments to repress tumorigenesis (239–244), control neuropathic pain (245) and promote cardiac reprogramming from cardiac fibroblasts (24). As tankyrase inhibitors induce a variety of effects, such as canonical WNT/β-catenin signaling inhibition, YAP signaling inhibition, PI3K signaling inhibition and telomere shortening through defective poly-ADP-ribosylation of AXIN, AMOT, PTEN and TERF1, respectively (236–238), the tankyrase inhibitors mentioned above are not in clinical trials at present (Table II).

β-catenin is an effector of the WNT/β-catenin signaling cascade (2–4), and stabilized nuclear β-catenin associates with BCL9, CBP, p300, EZH2 and SMARCA4 to activate transcription of TCF/LEF-target genes (Fig. 3). As β-catenin does not have intrinsic enzymatic activity, β-catenin inhibitors have been developed with a focus on its protein-protein interactions (175). BIO (246), CHIR99021 (247), LY2090314 (248) and TWS119 (249) are GSK3β or GSK3 inhibitors that can activate the WNT/β-catenin signaling cascade (Table III). GSK3β inhibitors are applied as pro-WNT signaling reagents for cell processing in the field of regenerative medicine (250,251); however, clinical application of GSK3β inhibitors as pro-WNT signaling therapeutics for patients with impaired WNT/β-catenin signaling is too challenging. By contrast, BC2059 (252), CGP049090 (253), CWP232228 (254), ICG-001 (255), LF3 (256), MSAB (257), PKF115-584 (258), PRI-724 (259) and SAH-BCL9 (260) are β-catenin inhibitors that induce antitumor effects through repression of TCF/LEF-target genes, whereas some of these β-catenin inhibitors also show therapeutic effects in model animal experiments of non-cancerous diseases, such as pulmonary fibrosis and chronic kidney disease (261,262). PRI-724 is in clinical trials for cancer patients (Table II).

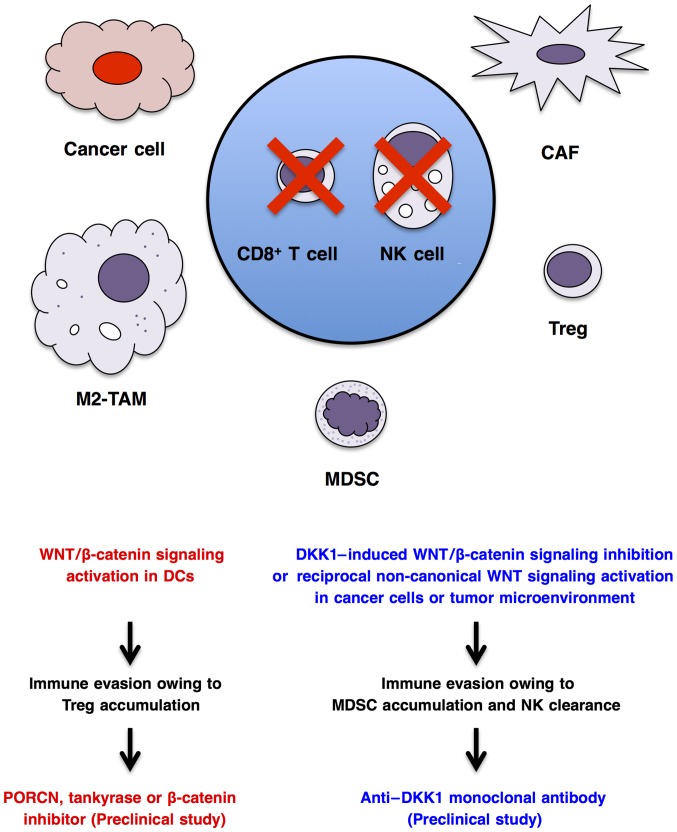

Cancer cells interact with immune cells and stromal cells to regulate antitumor immunity, angiogenesis and metabolism in the tumor microenvironment (78,213,263,264). WNT/β-catenin signaling activation in cancer cells indirectly regulates immunity through transcriptional regulation of CCL4 chemo-kine or ULBP ligands for dendritic cells and natural killer cells, respectively (265,266), whereas canonical or non-canonical WNT signaling activation in dendritic cells (267), macrophages (268), myeloid-derived suppressor cells (269) and T lymphocytes (270) directly regulates their functions and antitumor immunity. WNT/β-catenin signaling activation in dendritic cells can enhance immune evasion through accumulation of regulatory T cells (271–273), and anti-WNT signaling therapy using a PORCN inhibitor, tankyrase inhibitor or β-catenin inhibitor may be applicable for the treatment of immune evasion (Fig. 5). By contrast, WNT/β-catenin signaling inhibition in cancer cells or tumor microenvironment owing to DKK1 upregulation can also lead to immune evasion through the accumulation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells and clearance of natural killer and cytotoxic T cells (266,269,274), and pro-WNT signaling therapy using an anti-DKK1 mAb may be applicable for the treatment of immune evasion in cancer patients with DKK1 upregulation (Fig. 5). As WNT signaling cascades in cancer cells, stromal cells and immune cells regulate immune tolerance and antitumor immunity in a cell context-dependent manner, comprehensive understanding of WNT-dependent dynamic immune regulation based on precise immune monitoring is necessary before prescription of anti- or pro-WNT signaling therapeutics for cancer patients with immune evasion.

Figure 5.

Context-dependent WNT signaling and immune evasion. Cancer cells and CAFs dictate accumulation of M2-TAMs, MDSCs and regulatory T (Treg) cells in the tumor environment to give rise to immune evasion through clearance or functional inhibition of CD8+ effector T cells and NK cells. WNT/β-catenin signaling activation in DCs can enhance immune evasion through Treg accumulation in the tumor microenvironment, whereas DKK1-induced WNT/β-catenin signaling inhibition in cancer cells or the tumor microenvironment can also enhance immune evasion through MDSC accumulation and NK clearance. Anti-WNT signaling therapy using PORCN inhibitor, tankyrase inhibitor or β-catenin inhibitor may be applicable for the treatment of immune evasion induced by WNT/β-catenin signaling activation. By contrast, pro-WNT signaling therapy using an anti-DKK1 monoclonal antibody may be applicable for the treatment of immune evasion associated with DKK1 upregulation. As WNT signaling cascades are involved in context-dependent immune evasion and antitumor immunity, precise immune monitoring and comprehensive understanding of WNT-dependent immune regulation are necessary to apply WNT-targeted therapy for cancer patients with immune evasion. CAFs, cancer-associated fibroblasts; M2-TAMs, M2-type tumor associated macrophages; NK, natural killer; DCs, dendritic cells; MDSCs, myeloid-derived suppressor cells; PORCN, porcupine; DKK1, Dickkopf-related protein 1.

9. Conclusion

WNT signaling molecules are dysregulated in human diseases, such as cancer, bone diseases, cardiovascular diseases, neuropsychiatric diseases and other PCP-related diseases. Therapeutics targeting PORCN, RSPO3, FZD receptors, ROR1, β-catenin and DKK1 are in clinical trials for cancer patients, and SOST-targeting therapeutics are in clinical trials for osteoporotic patients. Fine-tuning of WNT-targeting therapeutics is necessary for the optimization of their clinical efficacy and safety, as WNT signals regulate a variety of pathophysiological conditions in a context-dependent manner. WNT-targeting therapeutics have also been applied as in vitro stem-cell processing reagents for regenerative medicine.

Acknowledgments

This study was financially supported in part by a Grant-in-Aid for the knowledge base project from M. Katoh's Fund.

References

- 1.Katoh M. WNT and FGF gene clusters (Review) Int J Oncol. 2002;21:1269–1273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Katoh M, Katoh M. WNT signaling pathway and stem cell signaling network. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:4042–4045. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Niehrs C. The complex world of WNT receptor signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:767–779. doi: 10.1038/nrm3470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang K, Wang X, Zhang H, Wang Z, Nan G, Li Y, Zhang F, Mohammed MK, Haydon RC, Luu HH, et al. The evolving roles of canonical WNT signaling in stem cells and tumorigenesis: Implications in targeted cancer therapies. Lab Invest. 2016;96:116–136. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2015.144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Acebron SP, Niehrs C. β-catenin-independent roles of Wnt/LRP6 signaling. Trends Cell Biol. 2016;26:956–967. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2016.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rada P, Rojo AI, Offergeld A, Feng GJ, Velasco-Martín JP, González-Sancho JM, Valverde ÁM, Dale T, Regadera J, Cuadrado A. WNT-3A regulates an Axin1/NRF2 complex that regulates antioxidant metabolism in hepatocytes. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2015;22:555–571. doi: 10.1089/ars.2014.6040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Katoh M. WNT/PCP signaling pathway and human cancer (Review) Oncol Rep. 2005;14:1583–1588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang S, Chen L, Cui B, Chuang HY, Yu J, Wang-Rodriguez J, Tang L, Chen G, Basak GW, Kipps TJ. ROR1 is expressed in human breast cancer and associated with enhanced tumor-cell growth. PLoS One. 2012;7:e31127. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhuo W, Kang Y. Lnc-ing ROR1-HER3 and Hippo signalling in metastasis. Nat Cell Biol. 2017;19:81–83. doi: 10.1038/ncb3467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Medema JP. Cancer stem cells: The challenges ahead. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15:338–344. doi: 10.1038/ncb2717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holland JD, Klaus A, Garratt AN, Birchmeier W. Wnt signaling in stem and cancer stem cells. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2013;25:254–264. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2013.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lamb R, Bonuccelli G, Ozsvári B, Peiris-Pagès M, Fiorillo M, Smith DL, Bevilacqua G, Mazzanti CM, McDonnell LA, Naccarato AG, et al. Mitochondrial mass, a new metabolic biomarker for stem-like cancer cells: Understanding WNT/FGF-driven anabolic signaling. Oncotarget. 2015;6:30453–30471. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tam WL, Weinberg RA. The epigenetics of epithelial-mesenchymal plasticity in cancer. Nat Med. 2013;19:1438–1449. doi: 10.1038/nm.3336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ranganathan P, Weaver KL, Capobianco AJ. Notch signalling in solid tumours: A little bit of everything but not all the time. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:338–351. doi: 10.1038/nrc3035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gonzalez DM, Medici D. Signaling mechanisms of the epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Sci Signal. 2014;7:re8. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2005189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Katoh M, Nakagama H. FGF receptors: Cancer biology and therapeutics. Med Res Rev. 2014;34:280–300. doi: 10.1002/med.21288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yu M, Ting DT, Stott SL, Wittner BS, Ozsolak F, Paul S, Ciciliano JC, Smas ME, Winokur D, Gilman AJ, et al. RNA sequencing of pancreatic circulating tumour cells implicates WNT signalling in metastasis. Nature. 2012;487:510–513. doi: 10.1038/nature11217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bozdag S, Li A, Riddick G, Kotliarov Y, Baysan M, Iwamoto FM, Cam MC, Kotliarova S, Fine HA. Age-specific signatures of glioblastoma at the genomic, genetic, and epigenetic levels. PLoS One. 2013;8:e62982. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miyamoto DT, Zheng Y, Wittner BS, Lee RJ, Zhu H, Broderick KT, Desai R, Fox DB, Brannigan BW, Trautwein J, et al. RNA-Seq of single prostate CTCs implicates noncanonical Wnt signaling in antiandrogen resistance. Science. 2015;349:1351–1356. doi: 10.1126/science.aab0917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gu Z, Churchman M, Roberts K, Li Y, Liu Y, Harvey RC, McCastlain K, Reshmi SC, Payne-Turner D, Iacobucci I, et al. Genomic analyses identify recurrent MEF2D fusions in acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Nat Commun. 2016;7:13331. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pettinato G, Ramanathan R, Fisher RA, Mangino MJ, Zhang N, Wen X. Scalable differentiation of human iPSCs in a multicellular spheroid-based 3D culture into hepatocyte-like cells through direct Wnt/β-catenin pathway inhibition. Sci Rep. 2016;6:32888. doi: 10.1038/srep32888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Motono M, Ioroi Y, Ogura T, Takahashi J. WNT-C59, a small-molecule WNT inhibitor, efficiently induces anterior cortex that includes cortical motor neurons from human pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2016;5:552–560. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2015-0261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matsuno K, Mae SI, Okada C, Nakamura M, Watanabe A, Toyoda T, Uchida E, Osafune K. Redefining definitive endoderm subtypes by robust induction of human induced pluripotent stem cells. Differentiation. 2016;92:281–290. doi: 10.1016/j.diff.2016.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mohamed TM, Stone NR, Berry EC, Radzinsky E, Huang Y, Pratt K, Ang YS, Yu P, Wang H, Tang S, et al. Chemical enhancement of in vitro and in vivo direct cardiac reprogramming. Circulation. 2017;135:978–995. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.024692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tao L, Zhang J, Meraner P, Tovaglieri A, Wu X, Gerhard R, Zhang X, Stallcup WB, Miao J, He X, et al. Frizzled proteins are colonic epithelial receptors for C. difficile toxin B. Nature. 2016;538:350–355. doi: 10.1038/nature19799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Collery RF, Volberding PJ, Bostrom JR, Link BA, Besharse JC. Loss of zebrafish mfrp causes nanophthalmia, hyperopia, and accumulation of subretinal macrophages. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2016;57:6805–6814. doi: 10.1167/iovs.16-19593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Lessons from hereditary colorectal cancer. Cell. 1996;87:159–170. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81333-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lammi L, Arte S, Somer M, Jarvinen H, Lahermo P, Thesleff I, Pirinen S, Nieminen P. Mutations in AXIN2 cause familial tooth agenesis and predispose to colorectal cancer. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;74:1043–1050. doi: 10.1086/386293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gala MK, Mizukami Y, Le LP, Moriichi K, Austin T, Yamamoto M, Lauwers GY, Bardeesy N, Chung DC. Germline mutations in oncogene-induced senescence pathways are associated with multiple sessile serrated adenomas. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:520–529. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.10.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Muzny DM, Bainbridge MN, Chang K, Dinh HH, Drummond JA, Fowler G, Kovar CL, Lewis LR, Morgan MB, Newsham IF, et al. Cancer Genome Atlas Network Comprehensive molecular characterization of human colon and rectal cancer. Nature. 2012;487:330–337. doi: 10.1038/nature11252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Giannakis M, Mu XJ, Shukla SA, Qian ZR, Cohen O, Nishihara R, Bahl S, Cao Y, Amin-Mansour A, Yamauchi M, et al. Genomic correlates of immune-cell infiltrates in colorectal carcinoma. Cell Rep. 2016;15:857–865. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.03.075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seshagiri S, Stawiski EW, Durinck S, Modrusan Z, Storm EE, Conboy CB, Chaudhuri S, Guan Y, Janakiraman V, Jaiswal BS, et al. Recurrent R-spondin fusions in colon cancer. Nature. 2012;488:660–664. doi: 10.1038/nature11282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ciriello G, Gatza ML, Beck AH, Wilkerson MD, Rhie SK, Pastore A, Zhang H, McLellan M, Yau C, Kandoth C, et al. TCGA Research Network Comprehensive molecular portraits of invasive lobular breast cancer. Cell. 2015;163:506–519. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.09.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bass AJ, Thorsson V, Shmulevich I, Reynolds SM, Miller M, Bernard B, Hinoue T, Laird PW, Curtis C, Shen H, et al. Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network Comprehensive molecular characterization of gastric adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2014;513:202–209. doi: 10.1038/nature13480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guichard C, Amaddeo G, Imbeaud S, Ladeiro Y, Pelletier L, Maad IB, Calderaro J, Bioulac-Sage P, Letexier M, Degos F, et al. Integrated analysis of somatic mutations and focal copy-number changes identifies key genes and pathways in hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Genet. 2012;44:694–698. doi: 10.1038/ng.2256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Campbell JD, Alexandrov A, Kim J, Wala J, Berger AH, Pedamallu CS, Shukla SA, Guo G, Brooks AN, Murray BA, et al. Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network Distinct patterns of somatic genome alterations in lung adenocarcinomas and squamous cell carcinomas. Nat Genet. 2016;48:607–616. doi: 10.1038/ng.3564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bailey P, Chang DK, Nones K, Johns AL, Patch AM, Gingras MC, Miller DK, Christ AN, Bruxner TJ, Quinn MC, et al. Australian Pancreatic Cancer Genome Initiative Genomic analyses identify molecular subtypes of pancreatic cancer. Nature. 2016;531:47–52. doi: 10.1038/nature16965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Robinson D, Van Allen EM, Wu YM, Schultz N, Lonigro RJ, Mosquera JM, Montgomery B, Taplin ME, Pritchard CC, Attard G, et al. Integrative clinical genomics of advanced prostate cancer. Cell. 2015;161:1215–1228. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kandoth C, Schultz N, Cherniack AD, Akbani R, Liu Y, Shen H, Robertson AG, Pashtan I, Shen R, Benz CC, et al. Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network Integrated genomic characterization of endometrial carcinoma. Nature. 2013;497:67–73. doi: 10.1038/nature12113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barker N. Adult intestinal stem cells: Critical drivers of epithelial homeostasis and regeneration. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15:19–33. doi: 10.1038/nrm3721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Flanagan DJ, Phesse TJ, Barker N, Schwab RH, Amin N, Malaterre J, Stange DE, Nowell CJ, Currie SA, Saw JT, et al. Frizzled7 functions as a Wnt receptor in intestinal epithelial Lgr5(+) stem cells. Stem Cell Reports. 2015;4:759–767. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2015.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jiang X, Cong F. Novel regulation of Wnt signaling at the proximal membrane level. Trends Biochem Sci. 2016;41:773–783. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2016.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Valenta T, Hausmann G, Basler K. The many faces and functions of β-catenin. EMBO J. 2012;31:2714–2736. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Katoh M. Mutation spectra of histone methyltransferases with canonical SET domains and EZH2-targeted therapy. Epigenomics. 2016;8:285–305. doi: 10.2217/epi.15.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang Z, Liu P, Inuzuka H, Wei W. Roles of F-box proteins in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14:233–247. doi: 10.1038/nrc3700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kajiguchi T, Katsumi A, Tanizaki R, Kiyoi H, Naoe T. Y654 of β-catenin is essential for FLT3/ITD-related tyrosine phosphorylation and nuclear localization of β-catenin. Eur J Haematol. 2012;88:314–320. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2011.01738.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jin B, Ding K, Pan J. Ponatinib induces apoptosis in imatinib-resistant human mast cells by dephosphorylating mutant D816V KIT and silencing β-catenin signaling. Mol Cancer Ther. 2014;13:1217–1230. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-13-0397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fernández-Sánchez ME, Barbier S, Whitehead J, Béalle G, Michel A, Latorre-Ossa H, Rey C, Fouassier L, Claperon A, Brullé L, et al. Mechanical induction of the tumorigenic β-catenin pathway by tumour growth pressure. Nature. 2015;523:92–95. doi: 10.1038/nature14329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.van Veelen W, Le NH, Helvensteijn W, Blonden L, Theeuwes M, Bakker ER, Franken PF, van Gurp L, Meijlink F, van der Valk MA, et al. β-catenin tyrosine 654 phosphorylation increases Wnt signalling and intestinal tumorigenesis. Gut. 2011;60:1204–1212. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.233460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kuechler A, Willemsen MH, Albrecht B, Bacino CA, Bartholomew DW, van Bokhoven H, van den Boogaard MJ, Bramswig N, Büttner C, Cremer K, et al. De novo mutations in β-catenin (CTNNB1) appear to be a frequent cause of intellectual disability: Expanding the mutational and clinical spectrum. Hum Genet. 2015;134:97–109. doi: 10.1007/s00439-014-1498-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dixon MW, Stem MS, Schuette JL, Keegan CE, Besirli CG. CTNNB1 mutation associated with familial exudative vitreoretinopathy (FEVR) phenotype. Ophthalmic Genet. 2016;37:468–470. doi: 10.3109/13816810.2015.1120318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lui JH, Hansen DV, Kriegstein AR. Development and evolution of the human neocortex. Cell. 2011;146:18–36. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Inestrosa NC, Arenas E. Emerging roles of Wnts in the adult nervous system. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010;11:77–86. doi: 10.1038/nrn2755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bayod S, Felice P, Andrés P, Rosa P, Camins A, Pallàs M, Canudas AM. Downregulation of canonical Wnt signaling in hippocampus of SAMP8 mice. Neurobiol Aging. 2015;36:720–729. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wakabayashi T, Hidaka R, Fujimaki S, Asashima M, Kuwabara T. Diabetes impairs Wnt3 protein-induced neurogenesis in olfactory bulbs via glutamate transporter 1 inhibition. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:15196–15211. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.672857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Marzo A, Galli S, Lopes D, McLeod F, Podpolny M, Segovia-Roldan M, Ciani L, Purro S, Cacucci F, Gibb A, et al. Reversal of synapse degeneration by restoring Wnt signaling in the adult hippocampus. Curr Biol. 2016;26:2551–2561. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2016.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lu T, Aron L, Zullo J, Pan Y, Kim H, Chen Y, Yang TH, Kim HM, Drake D, Liu XS, et al. REST and stress resistance in ageing and Alzheimer's disease. Nature. 2014;507:448–454. doi: 10.1038/nature13163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dias C, Feng J, Sun H, Shao NY, Mazei-Robison MS, Damez-Werno D, Scobie K, Bagot R, LaBonté B, Ribeiro E, et al. β-catenin mediates stress resilience through Dicer1/microRNA regulation. Nature. 2014;516:51–55. doi: 10.1038/nature13976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Madison JM, Zhou F, Nigam A, Hussain A, Barker DD, Nehme R, van der Ven K, Hsu J, Wolf P, Fleishman M, et al. Characterization of bipolar disorder patient-specific induced pluripotent stem cells from a family reveals neurodevelopmental and mRNA expression abnormalities. Mol Psychiatry. 2015;20:703–717. doi: 10.1038/mp.2015.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Karantalis V, Hare JM. Use of mesenchymal stem cells for therapy of cardiac disease. Circ Res. 2015;116:1413–1430. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.303614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Atashi F, Modarressi A, Pepper MS. The role of reactive oxygen species in mesenchymal stem cell adipogenic and osteogenic differentiation: A review. Stem Cells Dev. 2015;24:1150–1163. doi: 10.1089/scd.2014.0484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chen Y, Alman BA. Wnt pathway, an essential role in bone regeneration. J Cell Biochem. 2009;106:353–362. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhang R, Oyajobi BO, Harris SE, Chen D, Tsao C, Deng HW, Zhao M. Wnt/β-catenin signaling activates bone morphogenetic protein 2 expression in osteoblasts. Bone. 2013;52:145–156. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2012.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ke HZ, Richards WG, Li X, Ominsky MS. Sclerostin and Dickkopf-1 as therapeutic targets in bone diseases. Endocr Rev. 2012;33:747–783. doi: 10.1210/er.2011-1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Boudin E, Fijalkowski I, Piters E, Van Hul W. The role of extracellular modulators of canonical Wnt signaling in bone metabolism and diseases. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2013;43:220–240. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2013.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Silva BC, Bilezikian JP. Parathyroid hormone: Anabolic and catabolic actions on the skeleton. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2015;22:41–50. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2015.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Maeda K, Kobayashi Y, Udagawa N, Uehara S, Ishihara A, Mizoguchi T, Kikuchi Y, Takada I, Kato S, Kani S, et al. Wnt5a-Ror2 signaling between osteoblast-lineage cells and osteoclast precursors enhances osteoclastogenesis. Nat Med. 2012;18:405–412. doi: 10.1038/nm.2653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kim SJ, Bieganski T, Sohn YB, Kozlowski K, Semënov M, Okamoto N, Kim CH, Ko AR, Ahn GH, Choi YL, et al. Identification of signal peptide domain SOST mutations in autosomal dominant craniodiaphyseal dysplasia. Hum Genet. 2011;129:497–502. doi: 10.1007/s00439-011-0947-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Brunkow ME, Gardner JC, Van Ness J, Paeper BW, Kovacevich BR, Proll S, Skonier JE, Zhao L, Sabo PJ, Fu Y, et al. Bone dysplasia sclerosteosis results from loss of the SOST gene product, a novel cystine knot-containing protein. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;68:577–589. doi: 10.1086/318811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Balemans W, Patel N, Ebeling M, Van Hul E, Wuyts W, Lacza C, Dioszegi M, Dikkers FG, Hildering P, Willems PJ, et al. Identification of a 52 kb deletion downstream of the SOST gene in patients with van Buchem disease. J Med Genet. 2002;39:91–97. doi: 10.1136/jmg.39.2.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Van Wesenbeeck L, Cleiren E, Gram J, Beals RK, Bénichou O, Scopelliti D, Key L, Renton T, Bartels C, Gong Y, et al. Six novel missense mutations in the LDL receptor-related protein 5 (LRP5) gene in different conditions with an increased bone density. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72:763–771. doi: 10.1086/368277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Canalis E. Wnt signalling in osteoporosis: Mechanisms and novel therapeutic approaches. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2013;9:575–583. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2013.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Laine CM, Joeng KS, Campeau PM, Kiviranta R, Tarkkonen K, Grover M, Lu JT, Pekkinen M, Wessman M, Heino TJ, et al. WNT1 mutations in early-onset osteoporosis and osteogenesis imperfecta. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1809–1816. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1215458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gong Y, Slee RB, Fukai N, Rawadi G, Roman-Roman S, Reginato AM, Wang H, Cundy T, Glorieux FH, Lev D, et al. Osteoporosis-Pseudoglioma Syndrome Collaborative Group LDL receptor-related protein 5 (LRP5) affects bone accrual and eye development. Cell. 2001;107:513–523. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00571-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mani A, Radhakrishnan J, Wang H, Mani A, Mani MA, Nelson-Williams C, Carew KS, Mane S, Najmabadi H, Wu D, et al. LRP6 mutation in a family with early coronary disease and metabolic risk factors. Science. 2007;315:1278–1282. doi: 10.1126/science.1136370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Simsek Kiper PO, Saito H, Gori F, Unger S, Hesse E, Yamana K, Kiviranta R, Solban N, Liu J, Brommage R, et al. Cortical-bone fragility: Insights from sFRP4 deficiency in Pyle's disease. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:2553–2562. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1509342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Estrada K, Styrkarsdottir U, Evangelou E, Hsu YH, Duncan EL, Ntzani EE, Oei L, Albagha OM, Amin N, Kemp JP, et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis identifies 56 bone mineral density loci and reveals 14 loci associated with risk of fracture. Nat Genet. 2012;44:491–501. doi: 10.1038/ng.2249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Carmeliet P, Jain RK. Molecular mechanisms and clinical applications of angiogenesis. Nature. 2011;473:298–307. doi: 10.1038/nature10144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Katoh M. Therapeutics targeting angiogenesis: Genetics and epigenetics, extracellular miRNAs and signaling networks (Review) Int J Mol Med. 2013;32:763–767. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2013.1444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hayakawa Y, Ariyama H, Stancikova J, Sakitani K, Asfaha S, Renz BW, Dubeykovskaya ZA, Shibata W, Wang H, Westphalen CB, et al. Mist1 expressing gastric stem cells maintain the normal and neoplastic gastric epithelium and are supported by a perivascular stem cell niche. Cancer Cell. 2015;28:800–814. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rafii S, Butler JM, Ding BS. Angiocrine functions of organ-specific endothelial cells. Nature. 2016;529:316–325. doi: 10.1038/nature17040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Goel HL, Mercurio AM. VEGF targets the tumour cell. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13:871–882. doi: 10.1038/nrc3627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ferrara N, Adamis AP. Ten years of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor therapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2016;15:385–403. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2015.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]