Abstract

Background and Purpose

The neuropharmacological profile of the synthetic cathinone mephedrone (MEPH) is influenced by stereochemistry. Both MEPH enantiomers are monoamine transporter substrates, but R-MEPH is primarily responsible for rewarding effects of MEPH as it produces greater locomotor activation and intracranial self-stimulation than S-MEPH. S-MEPH is a 50-fold more potent 5-HT releaser than R-MEPH and does not place preference in rats. MEPH is also structurally similar to the cathinone derivative bupropion, an antidepressant and smoking cessation medication, suggesting MEPH has therapeutic and addictive properties.

Methods

We tested the hypothesis that S-MEPH reduces anxiety- and depression-like behaviors in rats withdrawn from chronic cocaine or methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV) using the elevated plus maze (EPM) and forced swim test (FST), respectively. Rats were tested 48-h after a binge-like paradigm (3x/day for 10 days in 1-h intervals) of cocaine (10 mg/kg), MDPV (1 mg/kg) or saline. In vitro studies assessed the receptor binding and activity of S-MEPH.

Key Results

Rats withdrawn from chronic cocaine or MDPV displayed an increase in anxiety- and depression-like behaviors that was antagonized by treatment with S-MEPH (10, 30 mg/kg). S-MEPH displayed affinity, but not agonist activity, for 5-HT2 receptors (2A, 2B, 2C) and showed negligible affinity for dopaminergic, adrenergic and nicotinic receptors.

Conclusion and Implication

S-MEPH attenuated withdrawal behaviors following chronic cocaine or MDPV, perhaps through 5-HT release and/or 5-HT2 receptor interactions. The present data suggest S-MEPH may be a possible structural and pharmacological template to develop maintenance therapy for acute anxiety and depression during early withdrawal from psychostimulant abuse.

Keywords: cathinone, cocaine, MDPV, mephedrone, EPM, anxiety, depression, 5-HT

1. Introduction

Psychostimulants of the designer cathinone class (i.e., beta-ketone amphetamines) are known colloquially as “bath salts” [Karch et al., 2015; Kerrigan et al., 2016]. Mechanistically, synthetic cathinones have been classified according to two distinct actions on the monoamine system. One class is comprised of substrate-type releasers, such as mephedrone (4-methylmethcathinone, MEPH), that enter the presynaptic neuron and promote transporter-mediated release of dopamine (DA) and serotonin (5-HT) [Baumann et al., 2012; Eshleman et al., 2013; López-Arnau et al., 2012; Opacka-Juffry et al., 2014]. In vivo microdialysis studies have shown that the substrate action of MEPH increases extracellular DA and 5-HT in the nucleus accumbens of rats [Baumann et al., 2012; Kehr et al., 2011]. MEPH also increases locomotor activity in rats and mice following acute exposure and produces locomotor sensitization following repeated, intermittent exposure [Gatch et al., 2013; Gregg et al., 2013; López-Arnau et al., 2012; Motbey et al., 2012; Shortall et al., 2012; Wright et al., 2012]. In preclinical rat models of abuse liability, MEPH facilitates intracranial self-stimulation (ICSS), is self-administered, and produces conditioned place preference (CPP) that is dependent on active dopamine D1 receptors [Bonano et al., 2013; Hadlock et al., 2011; Lisek et al., 2012; Motbey et al., 2013].

A second class of synthetic cathinones is comprised of monoamine transport blockers, such as 3,4- methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV), that prevent cellular reuptake of monoamines through a cocaine-like mechanism [Baumann et al., 2013]. Relative to cocaine, MDPV is a 10-fold more potent monoamine transport blocker and shows preferential selectivity for dopamine transporters (DAT) and norepinephrine transporters (NET) with weak inhibition at 5-HT transporters (SERT) [Baumann et al., 2013; Simmler et al., 2013]. MDPV produces cocaine-like behavioral effects, but displays greater potency than cocaine in fixed-ratio and progressive-ratio self-administration paradigms, as well as in locomotor studies [Aarde et al., 2013; Schindler et al., 2016]. MDPV is short acting, so users have a frequent desire to re-dose (binge-like patterns of consumption) [Novellas et al., 2015]. MDPV and MEPH have provided templates for the design and synthesis of newer generation synthetic cathinone compounds, such as α-PVP, 4-MEC, naphyrone, and pentedrone, which differ in structure from MDPV and MEPH by simple functional group substitutions.

The stereochemistry of enantiomers allows us to separate the addictive and potential therapeutic effects of a drug, as each enantiomer can produce different CNS effects. For example, amphetamine salt (Adderall), a widely prescribed drug for attention deficit disorder, uses a 3:1 mixture of S:R amphetamine salts to optimize the pharmacokinetic profile and lower the abuse liability [Heal et al., 2013]. Methamphetamine has enantiomers with different pharmacokinetics where the S-enantiomer (Desoxyn) is more potent and addictive than the R-enantiomer, while the R-enantiomer is used in the nasal decongestant Vick’s Vapor Inhaler [Li et al., 2010]. Research also shows divergent behavioral and physiological effects with the two enantiomers of MDPV (Gannon et al., 2016; Schindler et al., 2016). Although both R- and S-MDPV fully substituted for cocaine, only the S-enantiomer dose-dependently increased locomotor activity, blood pressure and heart rate [Gannon et al., 2016; Schindler et al., 2016].

Stereochemistry also influences the behavioral and neurochemical profiles of MEPH [Gregg et al., 2015; Vouga et al., 2015]. MEPH has a chiral center at the α-carbon and exists as two enantiomers (R- and S-), which are sufficiently stable to racemization to allow for their independent in vitro and in vivo evaluation. Gregg et al. (2015) showed that both enantiomers (R- and S-) of MEPH display similar potency as substrates at DAT, however, S-MEPH is about 50-fold more potent than R-MEPH in promoting 5-HT release by its substrate action at SERT. Dose-response experiments using ICSS to compare rewarding effects demonstrated that R-MEPH (1–10 mg/kg) produces greater maximal facilitation of ICSS than equivalent doses of S-MEPH [Gregg et al., 2015]. In CPP studies, R-MEPH (5, 15 and 30 mg/kg) produces place preference whereas equivalent doses of S-MEPH do not have rewarding effects [Gregg et al., 2015]. Additionally, R-MEPH (5, 10, 20 and 30 mg/kg) induces greater locomotor activity than S-MEPH (5, 10, 20 and 30 mg/kg).

During the early withdrawal phase, human cocaine abusers report heightened anxiety and depression [Elman et al., 2002; Gawin and Kleber, 1986], both of which are observed in animal studies using validated behavioral assays [Erb et al., 2006; Perrine et al., 2008]. At the neurochemical level, discontinuation of chronic cocaine exposure produces 5-HT deficits, including decreases in extracellular 5-HT in the nucleus accumbens during early withdrawal [Parsons et al., 1995]. Given that S-MEPH is a potent 5-HT releaser and lacks significant rewarding effects in CPP and ICSS assays [Gregg et al., 2015], we hypothesized that it would reduce anxiety- and depression-like behaviors during withdrawal following repeated cocaine or MDPV exposure. We characterized the effects of S-MEPH on withdrawal-induced anxiety- and depression-like behavior using the elevated plus maze (EPM) and forced swim test (FST), respectively. Both are well established and validated rodent tests of emotional behaviors [Walf et al., 2007; Estanislau et al., 2011], and known anxiolytics (e.g., diazapem) and anti-depressants (e.g., fluoxetine and bupropion) produce significant effects in these models [Paine et al., 2002; Liu et al., 2010; Jesse et al., 2010]. Although 5-HT release is the primary mechanism of action of S-MEPH, we also screened S-MEPH against a battery of receptors in binding and functional assays to determine the degree of affinity and interaction between S-MEPH and a range of receptor targets. By correlating the in vitro binding results with the behavioral effects of S-MEPH, we aimed to elucidate a possible secondary mechanism that may contribute to its clinical relevance.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animals and compounds

Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (250–300 g; N=108; Harlan Laboratories, Indianapolis, IN) were used in all experiments. Animals were housed two per cage in a humidity-controlled vivarium, maintained on a 12-h light/dark cycle with lights turning on daily at 7:00AM. Rats were provided with ad libitum food and water access except during experimental testing. All procedures and animal care was conducted in accordance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and Temple University’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines.

Cocaine hydrochloride was obtained from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA, while MDPV and S-MEPH were synthesized according to published methods [Gregg et al., 2015]. All drugs were dissolved in physiological saline (0.9%) and injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) at a volume of 1 ml/kg. Equivalent injections of saline were given for control conditions.

2.2. Experimental Procedures

For both experiments, we used a binge-like paradigm in which saline, cocaine (10 mg/kg), or MDPV (1 mg/kg) was administered 3x/day for 10 days in 1-h intervals during the morning hours (~10:00AM–12:00PM) [Anneken et al., 2015; Craige et al., 2015]. Rats were randomized into 9 treatment groups (N=6 per treatment group): 1) Saline control, 2) Saline + S-MEPH 10 mg/kg, 3) Saline + S-MEPH 30 mg/kg, 4) Cocaine + Saline, 5) Cocaine + S-MEPH 10 mg/kg, 6) Cocaine + S-MEPH 30 mg/kg, 7) MDPV + Saline, 8) MDPV + S-MEPH 10 mg/kg, and 9) MDPV + S-MEPH 30 mg/kg. The doses of S-MEPH were chosen based on Gregg et al. (2015) who showed that R-MEPH (5, 15 and 30 mg/kg), but not S-MEPH (5, 15 and 30 mg/kg), dose-dependently increased place preference.

2.2.1. Elevated plus maze (EPM) experiments

Twenty-four hours after the last injection of cocaine, MDPV, or saline, rats (N=54) were injected with saline or S-MEPH (10 or 30 mg/kg) 2x/day for 2 days 6-h apart (~10:00AM–4:00PM) due to the relatively short half-life of racemic MEPH. Twenty-four hours after the last treatment with saline or S-MEPH (10 or 30 mg/kg), anxiety-like behavior was evaluated using the EPM test. EPM testing was conducted in the afternoon (~1:00PM–5:00PM). The apparatus consisted of four equal-sized runways (19″ by 4″) that were elevated 20″ off the ground in the shape of a plus sign. Two of the arms were enclosed by walls (13″ high) on three sides (“closed arm”), while the other two arms were without walls (“open arm”). Rats were tested using adjusted lighting with the open arm illuminated to 200 lux, while the center was set to 160 lux. Arm entry was considered when a rat’s head, shoulder, and two front limbs moved into the arm. The apparatus was thoroughly cleaned with 70% ethanol and allowed to dry between each session. Individual rats were first placed in the center of the maze and allowed to roam for 10min. The session was recorded, and the time on the open and closed arms was later scored by an experimenter blinded to treatment conditions. The amount of time spent on the open arms was determined and reported as a percentage of the entire session time. Open arm entries were also calculated.

2.2.2. Forced swim test (FST) experiments

Depression-like behavior was assessed in the FST using a separate cohort of rats (N=54). Following the 10-day binge injections of cocaine or MDPV, animals were returned to their home cages for 2 days before behavioral testing. Behavioral testing occurred on a varying schedule: day 1 swim sessions were conducted from ~1:00PM–5:00PM, whilst day 2 swim sessions were run from ~1:00PM–3:00PM. Rats were placed individually into a glass cylinder (18″ high, 8″ diameter) filled with 10″ of water (25°C) [El Hage et al., 2012]. Two swim sessions were performed to test for immobility. A 15 min pretest, during which no behaviors were recorded, served as habituation and was conducted 48-h into withdrawal. This was followed 24-h later by a 5 min test, during which the behaviors were recorded. Immediately after the first test, rats were dried and returned to their home cages and then treated with S-MEPH (10 and 30 mg/kg, i.p.) or saline. Two subsequent treatments were given 4-h and 30 min prior to a second swim session. The dosing paradigm was chosen to achieve the maximal pharmacological effect (Castagne et al., 2010). Time spent in the immobile state was manually scored after testing by an experimenter blinded to treatments. Immobility was defined as no additional movements other than those necessary to keep the rat’s head above water, and was expressed as a percentage of the total session time.

2.3. Binding and Functional Assays

Binding and functional assays were performed at the National Institute of Mental Health Psychoactive Drug Screening Program (PDSP), which is directed by Dr. Bryan Roth at the University of North Carolina. For radioligand binding, S-MEPH was screened at 10 μM for binding to the following receptors: 5-HT (5-HT1A,B,D, 5-HT2A-C, 5-HT3, 5-HT6, 5-HT7); DA (D1, D2, D3, D4, D5); sigma (sigma-1); kappa opioid; adrenergic (α1A, α1B, α1D, α2A, α2B, α2C, β1, β2, β3); muscarinic (M1–M4); and nicotinic (α2β2; α2β4; α3β2; α3β4; α4β2; α4β4; α7). 5-HT receptor subtypes were screened because 5-HT receptor activity influences DA transmission during cocaine addiction [Vázquez-Gómez et al., 2014]. Nicotinic receptors were screened because S-MEPH is structurally similar to the cathinone derivative bupropion (Wellbutrin), which inhibits monoamine reuptake and nicotinic receptors [Arias et al., 2009; Filip et al., 2006]. Sigma receptors and sodium channels were examined for comparison to the mechanism of action of cocaine. For targets that had more than 50% inhibition, Ki values were obtained, and then moved to functional assays. Functional assays used measurements of intracellular calcium mobilization for Gq/11-coupled targets performed on serotonin receptors: 5-HT2A, 5-HT2B, 5-HT2C. For a detailed description of the protocol, refer to the supplementary material1.

2.4. Statistical analysis

A two-way ANOVA was used to analyze time spent on the open arm and number of open arm entries during EPM testing, as well as immobility time in the FST. The two between-subject factors were “chronic treatment” and “treatment”. “Chronic treatment” was defined as the binge-like paradigm of cocaine, MDPV or saline. “Treatment” referred to the administration of two doses of S-MEPH (10 or 30 mg/kg) or saline following discontinuation of the binge-like paradigm. In the case of a significant overall ANOVA, Bonferroni post-hoc tests were used to determine group differences. All analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism 6.0 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA) with statistical significance set at P < 0.05.

3. Results

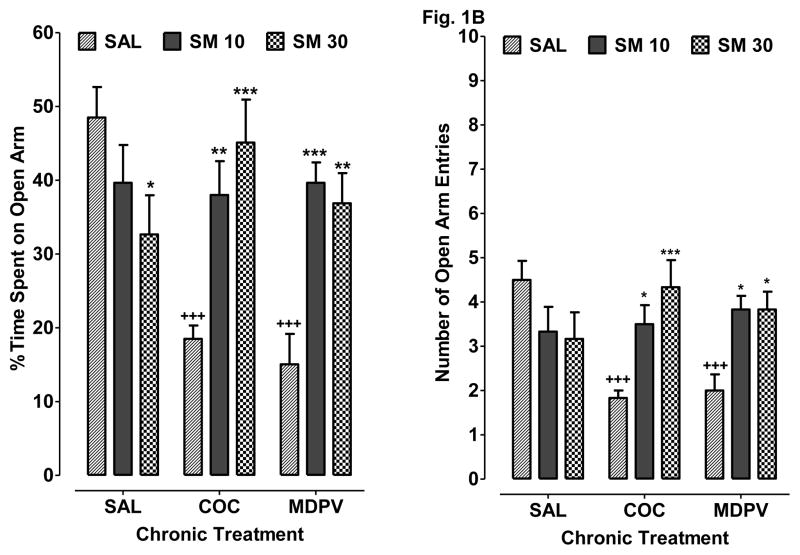

3.1. S-MEPH reduces anxiety-like behavior during psychostimulant withdrawal (Fig. 1)

Fig 1.

S-MEPH reduces cocaine and MDPV withdrawal-induced anxiety-like behavior in the EPM assay. Rats withdrawn from chronic treatment with saline (SAL), cocaine (COC) or MDPV were then treated with SAL, S-MEPH (10 mg/kg) (SM 10), or S-MEPH (30 mg/kg) (SM 30) during the drug-free period. A) Data are presented as percentage of time spent on the open arms + S.E.M. (N=6). B) Data are presented as open arm entry + S.E.M. (N=6). *P < 0.05 compared to respective chronic treatment group (SAL, COC or MDPV). +P < 0.05 compared to drug-naïve saline control (SAL SAL).

Data are presented as percentage of time spent on the open arms (N=6 per treatment group). A two-way ANOVA indicated a significant overall effect of chronic treatment [F(2, 45) = 3.86, P < 0.05] and treatment [F(2, 45) = 6.76, P < 0.05], as well as a significant interaction [F(4, 45) = 8.04, P < 0.05]. Bonferroni analysis showed that rats withdrawn from chronic cocaine exposure (COC SAL) or MDPV (MDPV SAL) spent less time on the open arms compared to drug-naïve control rats (SAL SAL) (P < 0.05). In rats withdrawn from chronic cocaine exposure, subsequent treatment with 10 mg/kg S-MEPH (COC SM 10) increased the percentage of time spent on the open arms compared to treatment with saline (COC SAL) (P < 0.05). Similar efficacy for 10 mg/kg of S-MEPH was observed in rats withdrawn from chronic MDPV exposure, as treatment with S-MEPH during the drug-free period (MDPV SM 10) enhanced the percentage of time spent on the open arms compared to treatment with saline (MDPV SAL) (P < 0.05). Treatment with a higher dose of S-MEPH (30 mg/kg) also increased the percentage of time spent on the open arms for rats withdrawn from either cocaine (COC SM 30) (P < 0.05 versus COC SAL) or MDPV (MDPV SM 30) (P < 0.05 versus MDPV SAL); however, treatment with 30 mg/kg S-MEPH by itself (SAL S-MEPH) caused a slight, but significant, decrease in time spent on the open arms compared to drug-naïve control rats (SAL SAL) (P < 0.05). The mean number of open arm entries for each treatment condition (N=6 per treatment group) are presented in Figure 1B. A two-way ANOVA indicated a significant overall effect of treatment [F(2, 45) = 4.06, P < 0.05] but not chronic treatment [P > 0.05], as well as a significant interaction effect [F(4, 45) = 5.99, P < 0.05]. Bonferroni post-hoc tests indicated that withdrawal following chronic cocaine (COC SAL) or MDPV (MDPV SAL) exposure caused a significant reduction in the number of open arm entries compared to drug-naïve control rats (SAL SAL) (P < 0.05). This effect was reversed after S-MEPH treatment in both cocaine (COC SM 10, 30) (P < 0.05 versus COC SAL) and MDPV (MDPV SM 10, 30) (P < 0.05 versus MDPV SAL) exposed animals.

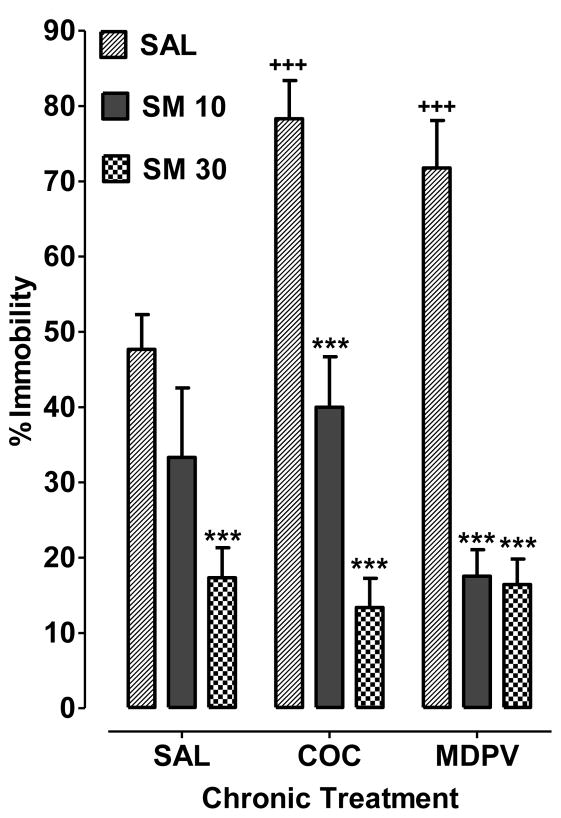

3.2. S-MEPH reduces depression-like behavior during psychostimulant withdrawal (Fig. 2)

Fig 2.

S-MEPH reduces cocaine and MDPV withdrawal-induced depression-like behavior in the FST. Rats withdrawn from chronic treatment with saline (SAL), cocaine (COC) or MDPV were then treated with SAL, S-MEPH (10 mg/kg) (SM 10), or S-MEPH (30 mg/kg) (SM 30) during the drug-free period. Data are presented as the percentage of time spent in the immobile state (% immobility) + S.E.M. (N=5–6). *P < 0.05 compared to respective chronic treatment group (SAL, COC or MDPV). +P < 0.05 compared to drug-naïve saline control (SAL SAL).

Data are presented as the percentage of time spent in the immobile state (N=6 per treatment group, except in group Saline + S-MEPH 10mg/kg with N=5 due to one rat dying during the binge injections). Analysis with two-way ANOVA showed effects of chronic treatment [F(2, 44) = 3.64, P < 0.05] and treatment [F(2, 44) = 72.37, P < 0.05], as well as a significant interaction [F(4, 44) = 5.26, P < 0.05]. Bonferroni analysis indicated that rats withdrawn from chronic cocaine exposure (COC SAL) or MDPV (MDPV SAL) exposure spent more time in the immobile state compared to drug-naïve control rats (SAL SAL) (P < 0.05). In rats withdrawn from chronic cocaine exposure, subsequent treatment with 10 mg/kg S-MEPH (COC SM 10) reduced the time spent in the immobile state compared to saline treatment (COC SAL) (P < 0.05). Similar efficacy for 10 mg/kg of S-MEPH was observed in rats withdrawn from chronic exposure to MDPV, as treatment with S-MEPH during the drug-free period (MDPV SM 10) reduced the time spent in the immobile state compared to treatment with saline (MDPV SAL) (P < 0.05). Treatment with a higher dose of S-MEPH (30 mg/kg) also decreased time spent in the immobile state for rats withdrawn from cocaine (COC SM 30) (P < 0.05 versus COC SAL) or MDPV (MDPV SM 30) (P < 0.05 versus MDPV SAL); however, treatment with the higher dose of S-MEPH by itself (30 mg/kg) (SAL S-MEPH) reduced time spent in the immobile state compared to drug-naïve control rats (SAL SAL) (P < 0.05).

3.3. S-MEPH interacts with 5-HT2 receptors

At 1 μM, S-MEPH inhibited radioligand binding to 5-HT2A, 5-HT2B, 5-HT2C, and sigma-1 receptors by more than 50%. Ki values for receptors were then determined by competitive inhibition of radioligand binding: 5-HT2A (Ki = 1.3 μM), 5-HT2B (Ki = 0.857 μM), 5-HT2C (Ki = 3.9 μM), and sigma-1 (Ki = 1.5 μM). Functional assays using measurements of intracellular calcium mobilization performed on serotonin receptors revealed that there was no stimulation up to 100 μM, suggesting that S-MEPH acted as an antagonist at these receptors. In addition, at a concentration of 1 μM, S-MEPH did not inhibit more than 50% of radioligand binding at the following receptors: 5-HT (5-HT1A,B,D, 5-HT3, 5-HT6, 5-HT7); DA (D1, D2, D3, D4, D5); kappa opioid; adrenergic (α1A, α1B, α1D, α2A, α2B, α2C, β1, β2, β3); muscarinic (M1–M4); and nicotinic (α2β2; α2β4; α3β2; α3β4; α4β2; α4β4; α7).

4. Discussion

Synthetic cathinones are noted for their psychoactive effects and categorized as Schedule I drugs in the United States; however, one older cathinone derivative, bupropion (Wellbutrin), is a frequently prescribed antidepressant and smoking cessation therapy. This paradox between newer synthetic cathinones (i.e., ones appearing within the past decade) and bupropion suggests that cathinones possess adverse and therapeutic properties that are dependent on factors such as structure and stereochemistry [Heal et al., 2013; Li et al., 2010]. We demonstrated previously that stereochemistry influences the neuropharmacological profile of MEPH and the R-enantiomer is primarily responsible for rewarding properties of MEPH [Gregg et al., 2015; Vouga et al., 2015]. The S-enantiomer is a potent 5-HT-releasing agent (50-fold stronger than R-MEPH) that does not produce rewarding effects in CPP and ICSS studies [Gregg et al., 2015; Vouga et al., 2015]. S-MEPH is structurally similar but mechanistically distinct from bupropion, with S-MEPH acting as a monoamine substrate to release 5-HT and bupropion acting as a DAT/NET blocker with minimal effects at SERT. Our original work with S-MEPH provided rationale for the present study in which we demonstrated efficacy for S-MEPH against psychostimulant withdrawal behaviors. The major findings of the present study were that: 1) MDPV, a synthetic cathinone and monoamine transport blocker, produced cocaine-like withdrawal behaviors in the EPM and FST; 2) S-MEPH, given to rats during the drug-free period following cocaine or MDPV, attenuated anxiety- and depression-like behaviors resulting from psychostimulant withdrawal; and 3) S-MEPH displayed affinity and interactions with 5-HT2 receptors but no agonist activity.

In our behavioral experiments, S-MEPH counteracted anxiety- and depression-like behaviors in rats withdrawn from a chronic cocaine or MDPV regimen when given during the drug-free period following psychostimulant exposure. In both the EPM and FST, S-MEPH displayed efficacy at 10 and 30 mg/kg. Although neither dose of S-MEPH is rewarding in the rat CPP assay [Gregg et al., 2015; Vouga et al., 2015], both doses produce some locomotor activation, especially ambulation, but not to the magnitude or duration of the R-enantiomer. Evidence that S-MEPH produces locomotor activation has to be considered in the interpretation of its efficacy in EPM and FST experiments. In the case of the EPM results, behavioral testing was conducted 24-h after the last treatment with S-MEPH, well after locomotor activation produced by acute S-MEPH subsides [Gregg et al., 2015]. Therefore, the ability of S-MEPH to increase time spent on the open arms in cocaine- or MDPV-withdrawn rats is more likely due to an anxiolytic-like effect than to locomotor activation resulting from acute S-MEPH exposure.

In the FST experiments, behavioral testing was conducted 30 min after the last S-MEPH injection, so hyperlocomotion caused by acute S-MEPH exposure may have exerted a more significant influence on behavioral outcomes. We chose the 30 min interval between the last S-MEPH injection and onset of behavioral testing based on the temporal profile of S-MEPH locomotor activation [Gregg et al., 2015]. In that study, 10 mg/kg of S-MEPH produced an increase in locomotor activity that returned to baseline levels 30–35 min post-injection, which was the time frame of FST experimentation here, and remained at baseline activity levels for the remainder of the 90-min observation period [Gregg et al., 2015]. Since 10 mg/kg of S-MEPH did not decrease time spent in the immobile state in drug-naïve control rats, the most parsimonious explanation for its efficacy in cocaine- or MDPV-abstinent rats is a reduction in depression-like behavior, as opposed to an increase in locomotor activity. However, with 30 mg/kg of S-MEPH, locomotor activation likely contributed to the efficacy of S-MEPH in the FST, as this higher dose decreased time spent in the immobile state in drug-naïve control rats and is associated with a more protracted increase in locomotor activation that persists for at least 90 min post-injection [Gregg et al., 2015]. Nonetheless, since the lower dose of 10 mg/kg was efficacious in the FST, we posit that S-MEPH is capable of reducing depression-like behavior accompanying psychostimulant withdrawal. Future studies will better examine S-MEPH for baseline anxiolytic and antidepressant effects, especially since acute administration of racemic MEPH produces both of these effects [Pail, 2015].

S-MEPH was screened against multiple receptor subtypes (5-HT, DA, adrenergic, kappa opioid, muscarinic, nicotinic, and sigma) in binding assays to provide a measure of interactions and degree of affinity (weak, strong, or no connection) between S-MEPH and receptor targets. Results showed that S-MEPH has moderate affinity for 5-HT2 receptors but little to no interaction with the other receptors tested. Functional assays revealed that S-MEPH did not display agonist activity at 5HT2 receptors, but exhibited some antagonist activities. Although identification of mechanism by correlating in vitro binding results with behavioral outcomes and pharmacokinetic data is challenging, it is interesting to note that Ki values obtained in the binding assays for 5-HT2 receptors were in the micromolar range [5-HT2A (Ki = 1.3 μM); 5-HT2B (Ki = 0.857 μM); 5-HT2C (Ki = 3.9 μM)]. Pharmacokinetic data indicate that racemic MEPH freely crosses the blood brain barrier and shows considerable distribution throughout the brain, which is reflected by its brain/plasma ratio of 1.85 [Martínez-Clemente et al., 2013]. A plot of locomotor activity versus racemic MEPH concentrations over time shows a direct concentration–effect relationship [Martínez-Clemente et al., 2013]. This model provided by Martinez-Clemente and colleagues (2013) reveals a mean in vivo EC50 value of 0.86 μM for MEPH that is in fairly close agreement with in vitro results showing that racemic MEPH inhibits monoamine uptake at concentrations below 1 μM [Gregg et al., 2015; López-Arnau et al., 2012]. According to Martínez-Clemente et al. (2013), the peak plasma concentration of racemic MEPH (HCl salt) after oral administration is 1.55 μM (331.2 ng/ml). In this study, we used i.p. injection of 10 mg/kg and 30 mg/kg S-MEPH. Assuming similar bioavailability following i.p. and oral administration, S-MEPH at 30 mg/kg (i.p.) would have significant occupancy at 5-HT2A and 5-HT2B and, to a lower extent, 5-HT2C receptors. Therefore, actions of S-MEPH on one or more of these 5-HT2 receptors may have contributed to its in vivo pharmacological effects, even though DAT and SERT are the primary targets of it actions with EC50 values of 70.2 nM and 60.9 nM for releasing DA and 5-HT, respectively.

Preclinical studies have identified roles for 5-HT2A and 5-HT2C receptors in regulating anxiety-induced cocaine withdrawal. Anxiety-like behavior is blocked by a 5-HT2A receptor antagonist, MDL 11,939, but enhanced by a 5-HT2A receptor agonist, TCB-2 [Clinard et al., 2015]. 5-HT2C receptor antagonism attenuates anxiety-like behavior [Craige et al., 2015; Martin et al., 2002] whereas a 5-HT2C receptor agonist produces anxiogenic effects [Cornelio et al., 2007; Moya et al., 2011]. One potential mechanism that contributed to the ability of S-MEPH to reduce anxiety-like behavior during psychostimulant withdrawal is 5-HT2C receptor blockade, which could reduce the activity of GABA interneurons and promote downstream elevation of extracellular DA in the nucleus accumbens. Interestingly, 5-HT2C receptor antagonism is thought to be a reason that fluoxetine (Prozac) does not produce the degree of anxiety during initial dosing that often plagues other selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) [Pälvimäki et al., 1996]. Thus, S-MEPH may work through a dual 5-HT-based mechanism to mitigate psychostimulant withdrawal, with a 5-HT2C receptor block underlying its anxiolytic efficacy and an increase in 5-HT release through its monoamine substrate actions underlying its antidepressant effect [Baumann et al., 2012; Eshleman et al., 2013; Gregg et al., 2015; López-Arnau et al., 2012; Opacka-Juffry et al., 2014]. A role for 5-HT2 receptors in the antidepressant effects of S-MEPH is also possible because 5-HT2A and 5-HT2C receptors facilitate depressive-like behavior in preclinical studies [Diaz and Maroteaux, 2011; Patel et al., 2004]. Although selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are used as antidepressants, their effects are not directly related to acute effects on the serotonin system. It takes at least two weeks of repeated administration for the antidepressant effects to be manifested, which has been attributed to upregulation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and BDNF-associated neurogenesis. It is possible that the behavioral effects of repeated administration of S-MEPH demonstrated in this study are also related to neuroplasticity.

In conclusion, we demonstrate that the S-enantiomer of MEPH, at doses that are not rewarding in CPP and ICSS rat experiments, may attenuate psychostimulant withdrawal, perhaps through both 5-HT transporter and receptor interactions. Our results suggest S-MEPH may be a potential structural and pharmacological template to develop maintenance therapy for psychostimulant dependence. However, it will be important in future studies to compare the therapeutic efficacy of S-MEPH against approved antidepressant and/or anxiolytic drugs such as diazepam, fluoxetine or bupropion. Our current design enabled us to simultaneously compare the effects of multiple doses of S-MEPH against two psychostimulants using behavioral measures of anxiety- and depression-like behavior, which did not allow for testing against known approved antidepressant and/or anxiolytic drugs. An advantage of the S-MEPH template is a rapid onset of action, whereas a disadvantage is its short duration of action and potential for in vivo racemization. It will be important to further assess the abuse liability of S-MEPH using rat self-administration assays, and to determine if S-MEPH can antagonize deficits in extracellular monoamine levels that occur during psychostimulant withdrawal.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

S-mephedrone effects against psychostimulant withdrawal were investigated

S-mephedrone reduced anxiety and depression during cocaine abstinence

S-mephedrone reduced anxiety and depression during MDPV abstinence

S-mephedrone displayed affinity, but not agonist activity, for 5-HT2 receptors (2A, 2B, 2C)

Acknowledgments

Role of Funding Source

The present work was supported by National Institutes of Health and National Institute on Drug Abuse through grants R01 DA039139, P30 DA013429-16, and T32 DA007237.

Footnotes

Supplementary material can be found by accessing the online version of this paper at http://dx.doi.org and by entering doi:...

Supplementary material can be found by accessing the online version of this paper at http://dx.doi.org and by entering doi:...

Contributors

Helene Philogene-Khalid conducted behavioral testing (elevated plus maze and forced swim test). Helene Philogene-Khalid and Scott Rawls contributed to data analysis, interpretation, and manuscript preparation. Lee-Yuan Liu-Chen interpreted in vitro binding studies conducted by the NIMH Psychoactive Drug Screening Program in the laboratory of Bryan Roth. Allen Reitz synthesized MDPV and the S enantiomer of mephedrone (MEPH). All authors approved of the final manuscript before submission.

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aarde SM, Huang PK, Creehan KM, Dickerson TJ, Taffe MA. The novel recreational drug 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV) is a potent psychomotor stimulant: Self-administration and locomotor activity in rats. Neuropharmacol. 2013;71:130–140. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anneken JH, Angoa-Perez M, Kuhn DM. 3,4-Methylenedioxypyrovalerone prevents while methylone enhances methamphetamine-induced damage to dopamine nerve endings: beta-ketoamphetamine modulation of neurotoxicity by the dopamine transporter. J Neurochem. 2015;133:211–222. doi: 10.1111/jnc.13048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arias HR. Is the inhibition of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors by bupropion involved in its clinical actions? Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2009;41:2098–2108. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2009.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann MH, Ayestas MA, Partilla JS, Sink JR, Shulgin AT, Daley PF, Brandt SD, Rothman RB, Ruoho AE, Cozzi NV. The designer methcathinone analogs, mephedrone and methylone, are substrates for monoamine transporters in brain tissue. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012;37:1192–1203. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann MH, Partilla JS, Lehner KR, Thorndike EB, Hoffman AF, Holy M, Rothman RB, Goldberg SR, Lupica CR, Sitte HH, Brandt SD, Tella SR, Cozzi NV, Schindler CW. Powerful cocaine-like actions of 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV), a principal constituent of psychoactive “bath salts” products. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;38:552–562. doi: 10.1038/npp.2012.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besnard J, Ruda GF, Setola V, Abecassis K, Rodriguiz RM, Huang XP, Norval S, Sassano MF, Shin AI, Webster LA, Simeons FR, Stojanovski L, Prat A, Seidah NG, Constam DB, Bickerton GR, Read KD, Wetsel WC, Gilbert IH, Roth BL, Hopkins AL. Automated design of ligands to polypharmacological profiles. Nature. 2012;492:215–220. doi: 10.1038/nature11691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonano JS, Glennon RA, De Felice LJ, Banks ML, Negus SS. Abuse-related and abuse-limiting effects of methcathinone and the synthetic “bath salts” cathinone analogs methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV), methylone and mephedrone on intracranial self-stimulation in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2013;231:199–207. doi: 10.1007/s00213-013-3223-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castagne V, Moser P, Roux S, Porsolt RD. Rodent models of depression: Forced swim and tail suspension behavioral despair tests in rats and mice. Curr Protoc Pharmacol. 2010;5(Unit 5.8) doi: 10.1002/0471141755.ph0508s49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinard CT, Bader LR, Sullivan MA, Cooper MA. Activation of 5-HT2a receptors in the basolateral amygdala promotes defeat-induced anxiety and the acquisition of conditioned defeat in Syrian hamsters. Neuropharmacol. 2015;90:102–112. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2014.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornélio AM, Nunes-de-Souza RL. Anxiogenic-like effects of mCPP microinfusions into the amygdala (but not dorsal or ventral hippocampus) in mice exposed to elevated plus-maze. Behav Brain Res. 2007;178:82–89. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craige CP, Lewandowski S, Kirby LG, Unterwald EM. Dorsal raphe 5-HT2C receptor and GABA networks regulate anxiety produced by cocaine withdrawal. Neuropharmacol. 2015;93:41–51. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2015.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz SL, Maroteaux L. Implication of 5-HT2B receptors in the serotonin syndrome. Neuropharmacol. 2011;61:495–502. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Hage C, Rappeneau V, Etievant A, Morel AL, Scarna H, Zimmer L, Bérod A. Enhanced anxiety observed in cocaine withdrawn rats is associated with altered reactivity of the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex. PLoS One. 2012;7:e43535. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elman I, Karlsgodt KH, Gastfriend DR, Chabris CF, Breiter HC. Cocaine-primed craving and its relationship to depressive symptomatology in individuals with cocaine dependence. J Psychopharmacol. 2002;16:163–167. doi: 10.1177/026988110201600207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erb S, Kayyali H, Romero K. A study of the lasting effects of cocaine pre-exposure on anxiety-like behaviors under baseline conditions and in response to central injections of corticotropin-releasing factor. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2006;85:206–213. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eshleman AJ, Wolfrum KM, Hatfield MG, Johnson RA, Murphy KV, Janowsky A. Substituted methcathinones differ in transporter and receptor interactions. Biochem Pharmacol. 2013;85:1803–1815. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2013.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estanislau C, Ramos AC, Ferraresi PD, Costa NF, de Carvalho HM, Batistela S. Individual differences in the elevated plus-maze and the forced swim test. Behav Process. 2011;86:46–51. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2010.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filip M, Bubar MJ, Cunningham KA. Contribution of serotonin (5-HT) 5-HT2 receptor subtypes to the discriminative stimulus effects of cocaine in rats. Psychopharmacol. 2006;183:482–489. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0197-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gannon BM, Williamson A, Suzuki M, Rice KC, Fantegrossi WE. Stereoselective Effects of abused “bath salt ” constituent 3, 4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone in mice: Drug discrimination, locomotor activity, and thermoregulation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2016:615–623. doi: 10.1124/jpet.115.229500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatch MB, Taylor CM, Forster MJ. Locomotor stimulant and discriminative stimulus effects of ‘bath salt’ cathinones. Behav Pharmacol. 2013;24:437–447. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e328364166d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gawin FH, Kleber HD. Abstinence symptomatology and psychiatric diagnosis in cocaine abusers. Clinical observations. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1986;43:107–113. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1986.01800020013003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregg RA, Tallarida CS, Reitz A, McCurdy C, Rawls SM. Mephedrone (4-methylmethcathinone), a principal component in psychoactive bath salts, produces behavioral sensitization in rats. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;133:746–750. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregg RA, Baumann MH, Partilla JS, Bonano JS, Vouga A, Tallarida CS, Velvadapu V, Smith GR, Peet MM, Reitz AB, Negus SS, Rawls SM. Stereochemistry of mephedrone neuropharmacology: Enantiomer-specific behavioural and neurochemical effects in rats. Br J Pharmacol. 2015;172:883–894. doi: 10.1111/bph.12951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadlock GC, Webb KM, McFadden LM, Chu PW, Ellis JD, Allen SC, Andrenyak DM, Vieira-Brock PL, German CL, Conrad KM, Hoonakker AJ, Gibb JW, Wilkins DG, Hanson GR, Fleckenstein AE. 4-Methylmethcathinone (mephedrone): Neuropharmacological effects of a designer stimulant of abuse. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2011;339:530–536. doi: 10.1124/jpet.111.184119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heal DJ, Smith SL, Gosden J, Nutt DJ. Amphetamine, past and present--A pharmacological and clinical perspective. J Psychopharmacol. 2013;27:479–496. doi: 10.1177/0269881113482532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jesse CR, Wilhelm EA, Nogueira CW. Depression-like behavior and mechanical allodynia are reduced by bis selenide treatment in mice with chronic constriction injury: A comparison with fluoxetine, amitriptyline, and bupropion. Psychopharmacol (Berl) 2010;212:513–522. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-1977-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karch SB. Cathinone neurotoxicity (“The ”3Ms”) Curr Neuropharmacol. 2015;13:21–25. doi: 10.2174/1570159X13666141210225009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehr J, Ichinose F, Yoshitake S, Goiny M, Sievertsson T, Nyberg F, Yoshitake T. Mephedrone, compared with MDMA (ecstasy) and amphetamine, rapidly increases both dopamine and 5-HT levels in nucleus accumbens of awake rats. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;164:1949–1958. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01499.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerrigan S, Savage M, Cavazos C, Bella P. Thermal degradation of synthetic cathinones: Implications for forensic toxicology. J Anal Toxicol. 2016;40:1–22. doi: 10.1093/jat/bkv099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroeze WK, Sassano MF, Huang XP, Lansu K, McCorvy JD, Giguère PM, Sciaky N, Roth BL. PRESTO-Tango as an open-source resource for interrogation of the druggable human GPCRome. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2015;22:362–369. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Everhart T, Jacob P, Jones R, Mendelson J. Stereoselectivity in the human metabolism of methamphetamine. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;69:187–192. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2009.03576.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisek R, Xu W, Yuvasheva E, Chiu YT, Reitz AB, Liu-Chen LY, Rawls SM. Mephedrone (‘bath salt’) elicits conditioned place preference and dopamine-sensitive motor activation. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;126:257–262. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Garza JC, Bronner J, Kim CS, Wei Z, Xin-Yun L. Acute administration of leptin produces anxiolytic-like effects: a comparison with fluoxetine. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2010;207:535–545. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1684-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Arnau R, Martínez-Clemente J, Pubill D, Escubedo E, Camarasa J. Comparative neuropharmacology of three psychostimulant cathinone derivatives: Butylone, mephedrone and methylone. Br J Pharmacol. 2012;167:407–420. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.01998.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin JR, Ballard TM, Higgins GA. Influence of the 5-HT2C receptor antagonist, SB-242084, in tests of anxiety. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2002;71:615–625. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(01)00713-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Clemente J, López-Arnau R, Carbó M, Pubill D, Camarasa J, Escubedo E. Mephedrone pharmacokinetics after intravenous and oral administration in rats: Relation to pharmacodynamics. Psychopharmacol. 2013;229:295–306. doi: 10.1007/s00213-013-3108-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motbey CP, Hunt GE, Bowen MT, Artiss S, McGregor IS. Mephedrone (4-methylmethcathinone, ‘meow’): Acute behavioural effects and distribution of Fos expression in adolescent rats. Addict Biol. 2012;17:409–422. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2011.00384.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motbey CP, Clemens KJ, Apetz N, Winstock AR, Ramsey J, Li KM, Wyatt N, Callaghan PD, Bowen MT, Cornish JL, McGregor IS. High levels of intravenous mephedrone (4-methylmethcathinone) self-administration in rats: Neural consequences and comparison with methamphetamine. J Psychopharmacol. 2013;27:823–836. doi: 10.1177/0269881113490325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moya PR, Fox MA, Jensen CL, Laporte JL, French HT, Murphy DL, Wendland JR. Altered 5-HT2C receptor agonist-induced responses and 5-HT2C receptor RNA editing in the amygdala of serotonin transporter knockout mice. BMC Pharmacol. 2011;11:1–9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2210-11-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novellas J, López-Arnau R, Carbó M, Pubill D, Camarasa J, Escubedo E. Concentrations of MDPV in rat striatum correlate with the psychostimulant effect. J Psychopharmacol. 2015;29:1209–1218. doi: 10.1177/0269881115598415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opacka-Juffry J, Pinnell T, Patel N, Bevan M, Meintel M, Davidson C. Stimulant mechanisms of cathinones - Effects of mephedrone and other cathinones on basal and electrically evoked dopamine efflux in rat accumbens brain slices. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2014;54:122–130. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2014.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pail PB, Costa KM, Leite CE, Campos MM. Comparative pharmacological evaluation of the cathinone derivatives, mephedrone and methedrone, in mice. Neurotoxicol. 2015;50:71–80. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2015.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paine TA, Jackman SL, Olmstead MC. Cocaine-induced anxiety: Alleviation by diazepam, but not buspirone, dimenhydrinate or diphenhydramine. Behav Pharmacol. 2002;13:511–523. doi: 10.1097/00008877-200211000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pälvimäki EP, Roth BL, Majasuo H. Interactions of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors with the serotonin 5-HT2c receptor. Psychopharmacol. 1996;126:234–240. doi: 10.1007/BF02246453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons LH, Koob GF, Weiss F. Extracellular serotonin is decreased in the nucleus accumbens during withdrawal from cocaine self-administration. Behav Brain Res. 1995;73:225–228. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(96)00101-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel JG, Bartoszyk GD, Edwards E, Ashby CR. The highly selective 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-ht)2a receptor antagonist, EMD 281014, significantly increases swimming and decreases immobility in male congenital learned helpless rats in the forced swim test. Synapse. 2004;52:73–75. doi: 10.1002/syn.10308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrine SA, Sheikh IS, Nwaneshiudu CA, Schroeder JA, Unterwald EM. Withdrawal from chronic administration of cocaine decreases delta opioid receptor signaling and increases anxiety- and depression-like behaviors in the rat. Neuropharmacology. 2008;54:355–364. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schindler CW, Thorndike EB, Goldberg SR, Lehner KR, Cozzi NV, Baumann MH, Brandt SD. Reinforcing and neurochemical effects of the ”bath salts” constituents 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV) and 3,4-methylenedioxy-N-methylcathinone (methylone) in male rats. Psychopharmacol. 2016;233:1981–1990. doi: 10.1007/s00213-015-4057-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schindler CW, Thorndike EB, Suzuki M, Rice KC, Baumann MH. Pharmacological mechanisms underlying the cardiovascular effects of the “bath salt” constituent 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV) Br J Pharmacol. 2016;173:3492–3501. doi: 10.1111/bph.13640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shortall SE, Macerola AE, Swaby RT, Jayson R, Korsah C, Pillidge KE, Wigmore PM, Ebling FJ, Richard Green A, Fone KC, King MV. Behavioural and neurochemical comparison of chronic intermittent cathinone, mephedrone and MDMA administration to the rat. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012;23:1085–1095. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2012.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmler LD, Buser TA, Donzelli M, Schramm Y, Dieu LH, Huwyler J, Chaboz S, Hoener MC, Liechti ME. Pharmacological characterization of designer cathinones in vitro. Br J Pharmacol. 2013;168:458–470. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.02145.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez-Gómez E, Arias HR, Feuerbach D, Miranda-Morales M, Mihailescu S, García-Colunga J, Targowska-Duda KM, Jozwiak K. Bupropion-induced inhibition of α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors expressed in heterologous cells and neurons from dorsal raphe nucleus and hippocampus. Eur J Pharmacol. 2014;740:103–111. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2014.06.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vouga A, Gregg RA, Haidery M, Ramnath A, Al-Hassani HK, Tallarida CS, Grizzanti D, Raffa RB, Smith GR, Reitz AB, Rawls SM. Stereochemistry and neuropharmacology of a “bath salt” cathinone: S-enantiomer of mephedrone reduces cocaine-induced reward and withdrawal in invertebrates. Neuropharmacol. 2015;91:109–116. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2014.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walf AA, Frye CA. The use of the elevated plus maze as an assay of anxiety-related behavior in rodents. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:322–328. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright MJ, Angrish D, Aarde SM, Barlow DJ, Buczynski MW, Creehan KM, Vandewater SA, Parsons LH, Houseknecht KL, Dickerson TJ, Taffe MA. Effect of ambient temperature on the thermoregulatory and locomotor stimulant effects of 4-methylmethcathinone in Wistar and Sprague-Dawley rats. PLoS One. 2012;7:e44652. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.