Summary

The biliary system plays an important role in several acquired and genetic disorders of the liver. We have previously shown that biliary duct epithelium contains cells giving rise to proliferative Lgr5+ organoids in vitro. However, it remained unknown whether all biliary cells or only a specific subset had this clonogenic activity. The cell surface protease ST14 was identified as a positive marker for the clonogenic subset of cholangiocytes and was used to separate clonogenic and non-clonogenic duct cells by fluorescence-activated cell sorting. Only ST14hi duct cells had the ability to generate organoids that could be serially passaged. The gene expression profiles of clonogenic and non-clonogenic duct cells were similar, but several hundred genes were differentially expressed. RNA fluorescence in situ hybridization showed that clonogenic duct cells are interspersed among regular biliary epithelium at a ∼1:3 ratio. We conclude that adult murine cholangiocytes can be subdivided into two populations differing in their proliferative capacity.

Keywords: bile duct, biliary tree, liver, progenitor, cholangiocyte, liver regeneration, organoid, clonogenic assay

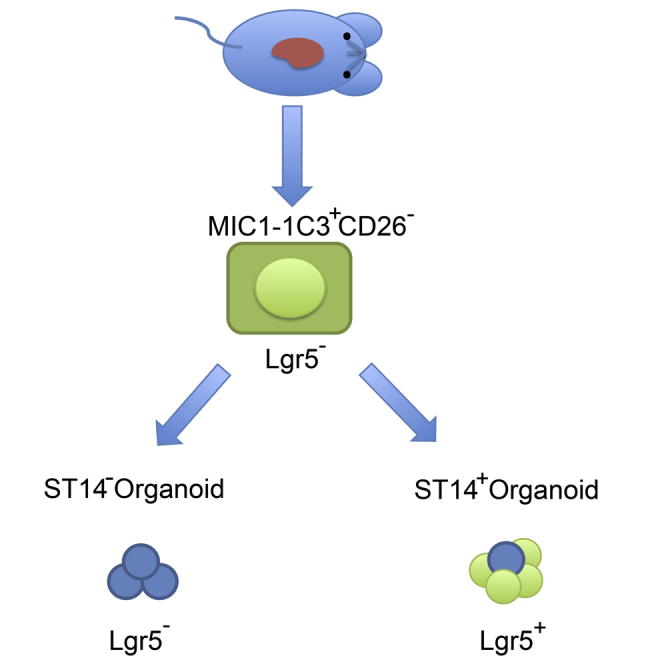

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

Adult cholangiocytes consist of two distinct subsets

-

•

ST14 is heterogeneously expressed in adult biliary epithelium

-

•

ST14hi cells are the clonogenic duct subset interspersed in normal bile ducts

-

•

Gene expression differs between ST14hi and ST14lo duct cells

In this article, Grompe and colleagues show that the cholangiocyte compartment of adult liver is heterogeneous. Their work shows conclusively that they differ in their clonogenic potential in the “Clevers” organoid assay and that they have a distinct gene expression profile.

Introduction

The adult liver is a highly regenerative organ that responds to injury with extensive cell proliferation. Although the mature epithelial cells (hepatocytes and cholangiocytes) can divide extensively, it has long been thought that the liver may harbor facultative stem cells which are called upon in certain chronic injury situations (Duncan et al., 2009, Miyajima et al., 2014). In the intestine, multilineage stem cells are found at the bottom of the crypts and express the R-spondin receptor LGR5 (Koo and Clevers, 2014). The adult liver of both mice and humans also harbors cells that can give rise to Lgr5+ hepatic organoids comparable with those generated from the intestine (Huch et al., 2013, Huch et al., 2015). In the intestine, Lgr5+ cells are observable during normal homeostasis and have been shown to be bona fide stem cells (Barker et al., 2007, Barker et al., 2010). Although adult liver does not contain Lgr5+ cells during normal homeostasis, such cells can emerge under conditions of injury and can give rise to hepatic organoids in vitro (Huch et al., 2013). Cultured hepatic organoids display extensive self-renewal and express hepatocyte-like properties after in vitro differentiation. They also can produce limited in vivo engraftment after transplantation, but the efficiency of this process is significantly lower than with true hepatocytes.

We recently showed that the precursor to Lgr5+ organoid-forming cells resides in the ductal compartments of the liver and pancreas in mice (Dorrell et al., 2014). It is currently unclear whether these highly clonogenic ductal cells are bipotential, i.e., can clonally produce both cholangiocytes and hepatocytes, in the adult liver (Espanol-Suner et al., 2012, Schaub et al., 2014, Tarlow et al., 2014a, Tarlow et al., 2014b, Yanger et al., 2013). It is also unclear whether this population contributes significantly to liver injury repair in vivo. Multiple genetic lineage tracing studies performed in mice argue against a contribution of ductal progenitors to the functional hepatocyte pool even with chronic injury (Grompe, 2014). Nonetheless, experiments performed in other species, most notably the rat, suggest that a bipotential liver stem cell does exist and that it resides within the cholangiocyte compartment (Evarts et al., 1989, Golding et al., 1996, Paku et al., 2001). Our previous work showed that the clonogenic (organoid-forming) population in the adult mouse liver is heterogeneous at the single-cell level (Dorrell et al., 2011, Dorrell et al., 2014) and that only approximately 1 out of 20 fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS)-purified biliary duct cells are clonogenic. We therefore wished to further refine the precursor population for Lgr5+ hepatic organoids and determine some of their key properties, such as their transcriptome. Here we demonstrate that adult mouse biliary duct epithelium is indeed functionally and transcriptionally heterogeneous. Differential expression of the cell surface marker ST14 was used to purify and study the organoid-forming population in the adult mouse liver, defining two distinct subtypes of adult cholangiocytes.

Results

Characterization of Duct Cell Heterogeneity

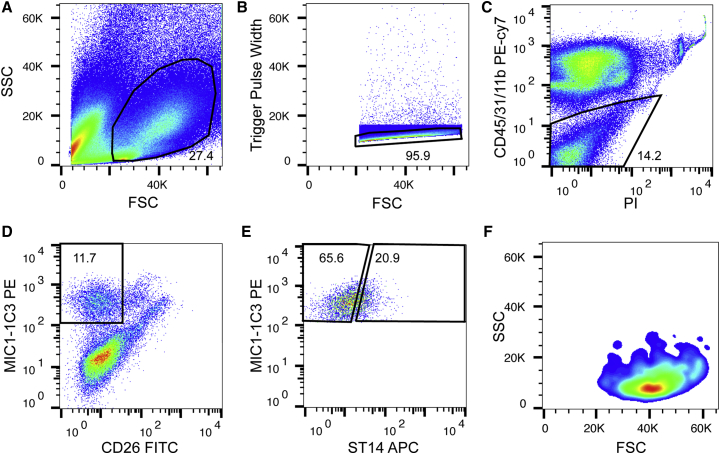

Biliary cells positive for the cell surface marker MIC1-1C3 have been previously shown to contain the precursors for Lgr5+ hepatic organoids (Dorrell et al., 2014). To further enrich clonogenic cells within this fraction, we searched for cell surface markers with heterogeneous expression in this population. Analysis of the DNA microarray data of the MIC1-1C3+/CD133+/CD26− clonogenic adult liver population (Dorrell et al., 2008, Dorrell et al., 2011) revealed several candidate markers including CD24, ANXA13, SLC34A2, COLLECTRIN, and ST14 (suppression of tumorigenicity 14). All of these were tested by FACS to determine whether they could further subdivide the clonogenic cholangiocyte population. Among the markers tested, ST14 gave the cleanest separation (Figures 1, S1E–S1G, and S1I); approximately 20.9% of cells were ST14hi and 65.6% ST14lo. Immunofluorescent labeling also showed that ST14 and the cholangiocyte marker EpCAM (epithelial cellular adhesion molecule) had partially overlapping distributions: EpCAM-expressing cells can be either ST14-positive or -negative (Figure S1A). Moreover, ST14 protein heterogeneity in human duct cells could also be found (Figure S4).

Figure 1.

FACS Strategy for Adult Duct Cells

The sequence of the sorting work flow is shown from left to right in (A) to (E). Mouse liver non-parenchymal (NPC) cells were labeled with MIC1-1C3, ST14, CD26, CD31, CD45, and CD11b.

(A and B) Cells were sequentially gated based on cell size (forward scatter [FSC] versus side scatter [SSC]) (A) and singlets (FSC versus trigger pulse width) (B).

(C) Dead cells and debris were excluded by detection of propidium iodide (PI) positivity. Concurrently a combination of CD45, CD31, and CD11b antibodies was used for depleting blood, endothelium, and Kupffer cells.

(D) CD26 (DPPIV) was used for hepatocyte staining.

(E) MIC1-1C3+ cells can be subdivided into two populations: ST14 high (ST14hiM+) and ST14 low (ST14loM+).

(F) Size and scatter properties of fully gated ST14hiM+ cells.

n = 10 independent mice. See also Figure S1.

Robust Single-Cell-Derived Organoid-Forming Efficiency

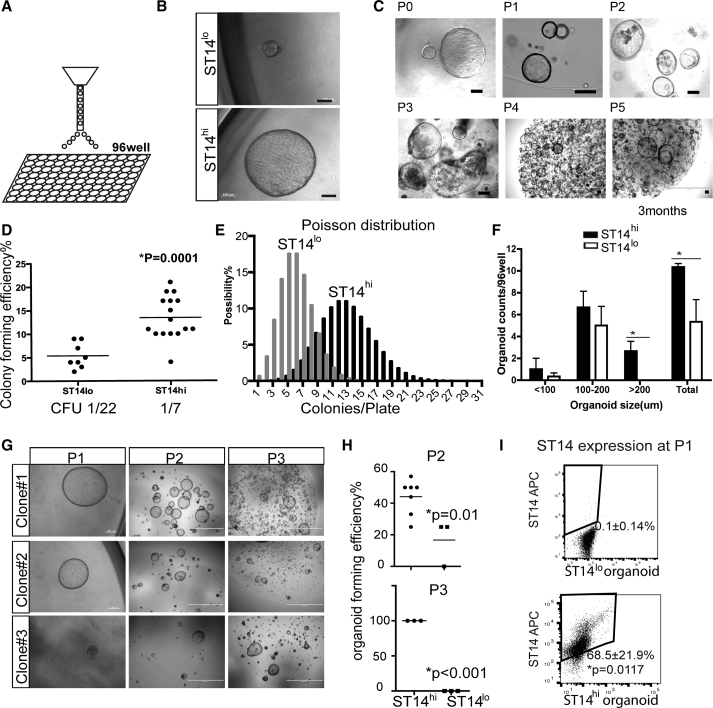

To investigate the expansion capability of these different cholangiocyte populations, we collected MIC1-1C3+ cells expressing high levels of ST14 (ST14hiM+) and MIC1-1C3+ cells expressing low levels of ST14 (ST14loM+) by FACS. Their clonogenic potential was then tested in a modified hepatic organoid-forming assay (Dorrell et al., 2014, Huch et al., 2013). Single ST14hi and ST14lo cells were deposited by FACS into a 96-well plate prefilled organoid culture medium (Figure 2A). At day 14 of culture, the ST14hi cells had formed larger organoids than ST14lo duct cells (Figures 2B and 2C). They also had a higher a priori organoid-forming efficiency (14 ± 4.8 organoids per 100 input cells, mean 1/7, n = 16) compared with ST14lo cells (5.4 ± 2.5 organoids per 100 input cells, mean 1/22, n = 8) (Figures 2D and 2E). Large organoids (>200 μm diameter) were produced from only the ST14hiM+ population (Figure 2F). The capacity for serial expansion was tested by passaging established organoids from the initial 96-well plates to 24-well plates. Organoids established from ST14hi cells displayed higher proliferation rates and could be passaged more efficiently than the small organoids from ST14lo cells (Figures 2G and 2H): Organoids initiated by ST14hi cells could be passaged more than three times while those from ST14lo cells could not be passaged more than twice (Figures 2C, 2G, and 2H). To determine whether ST14 was expressed in organoids in vitro, we performed FACS analysis. More than 65% of cells in the ST14hi derived organoids were ST14+ (Figure 2I, n = 4). Moreover, we found Lgr5 mRNA expressed only in ST14hi but not ST14lo cells from ST14hi cell-derived organoids (Figure S3A). Furthermore, ST14hi cell-derived organoids displayed low levels of expression of the mature hepatocyte marker Fah after differentiation in vitro (Figure S3B). Taken together, these results indicated that ST14hi ductal cells had a higher colony-forming ability, grew faster, and could be serially passaged with higher efficiency than their ST14hi counterparts. We therefore designated the ST14hiM+ population as clonogenic organoid-forming biliary cells.

Figure 2.

Clonogenicity of Biliary Duct Subsets

(A) Individual FACS-sorted ST14hiM+CD26−CD45/31/11b− and ST14loM+CD26− CD45/31/11b− cells were directly deposited into individual cells of a 96-well plate.

(B) Representative morphology of organoids generated by M+ST14lo and M+ST14hi cells. Culture day 14. Scale bars, 100 μm.

(C) Long-term expansion of M+ST14hi population colonies. P, number of passages. Scale bar, 100 μm.

(D) Colony-forming efficiency of single cells. The M+ST14lo population had an efficiency of ∼5.4% and M+ST14hi an efficiency of13.4%. p = 0.0001. Statistical analysis by unpaired t test. CFU, colony-forming unit (n = 8 plates from four independent mice for ST14lo, n = 16 plates from eight independent mice for ST14hi).

(E) Poisson distribution of M+ST14lo versus M+ST14hi organoid-forming efficiency from (D). The M+ST14lo population gave rise to an average of five colonies per 96-well plate while M+ST14hi gave rise to an average of 13. The distribution was clearly bimodal.

(F) Size distribution of organoids derived from single cells. Statistical analysis by t test (n = 3 independent experiments). ∗p < 0.01.

(G) Representative images of three different single-cell-derived M+ST14hi clones during serial passage. Scale bars, 100 μm (left panels) and 2 mm (middle and right panels).

(H) Efficiency of serial passage for the different populations. None of the organoids derived from M+ST14lo cells could be passaged more than three times. Statistical analysis by unpaired t test. Independent organoids for ST14hi in P2, n = 7; ST14lo in P3, n = 3; ST14hi and ST14lo in P3, n = 3.

(I) Flow-cytometry analysis of ST14 expression in the M+ST14hi (n = 4 independent experiments) and ST14lo (n = 3 independent experiments) derived organoids after in vitro expansion (unpaired t test, mean ± SD, p = 0.0117).

See also Figure S2.

ST14hi Cells Survive Longer Than Other Duct Cells Post Mortem

We previously reported that mouse liver harbors transplantable hepatocytes for up to 24 hr after death (Erker et al., 2010). We therefore wished to determine the postmortem survival of organoid-forming, clonogenic biliary cells. Mice were euthanized and kept at room temperature until later cell isolation by liver perfusion. Interestingly, large numbers of viable (propidium iodide-negative) cholangiocytes could still be isolated by FACS 24 hr after death. This duct population retained clonogenic activity and was able to form organoids capable of serial passage in vitro (Figure S2A). Moreover, the ST14hi subpopulation increased to ∼45% of M+ duct cells compared with only 21% in the normal liver (Figure S2B). These data indicate that adult liver clonogenic cholangiocytes are resistant to prolonged warm ischemia.

ST14hi Cells Are Present in Injured Liver

To assess the expression of ST14 during injury, we used the 3,5-diethoxycarbonyl-1,4-dihydrocollidine (DDC) diet and carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) to induce liver damage as previously reported (Huch et al., 2013). Importantly, the ST14hi percentage among MIC1-1C3+ duct cells (Figures S2C–S2F) remained stable during injury. In addition, the organoid-forming frequency of ST14hi cells from the injured liver was similar to that in normal liver (Figure S2G). These findings suggest that acute liver injury did not result in a selective expansion or loss of the clonogenic cholangiocyte population.

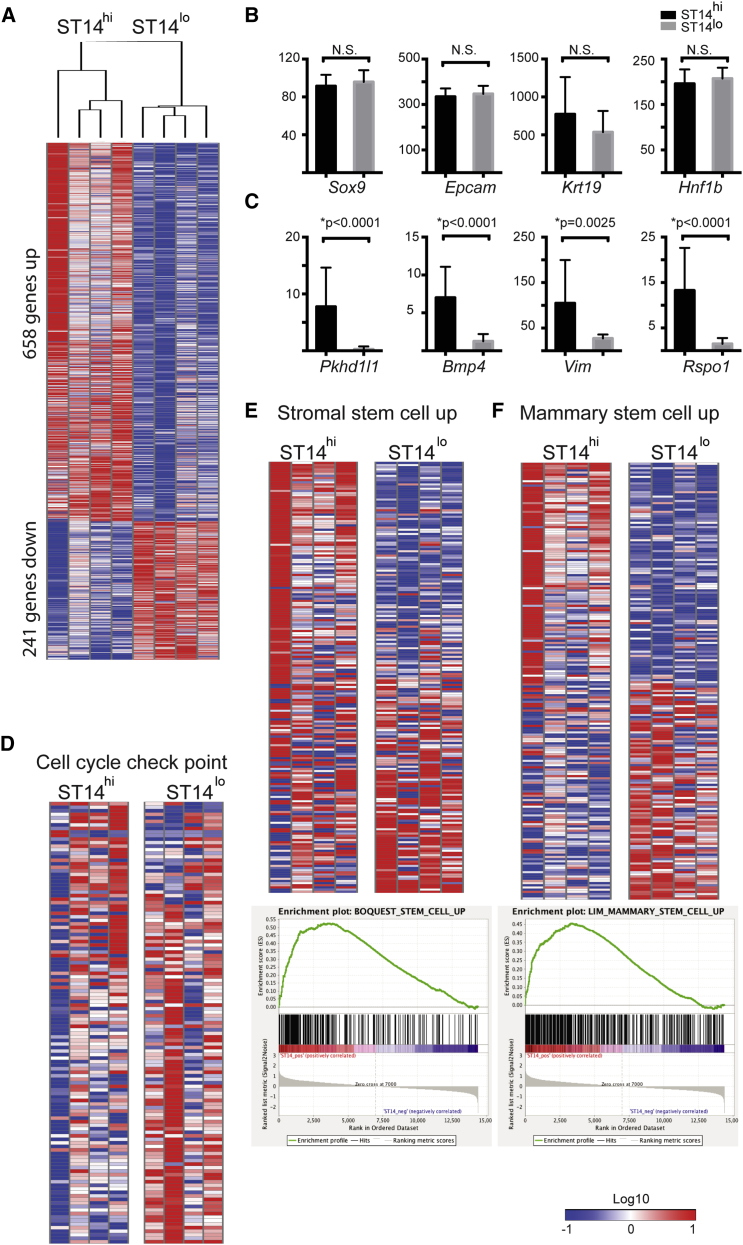

Transcriptomes of Adult Biliary Duct Subpopulations

To compare the ST14hiM+ and ST14loM+ populations at the transcriptional level, we extracted RNA from freshly FACS-sorted cells for sequencing. Multiple replicates (four ST14hi and four ST14lo) from independent cell isolations were analyzed. There were no significant differences between ST14hi and ST14lo populations in the expression of prototypical cholangiocyte cell markers such as Sox9, Epcam, and Krt19 (Figure 3B and Table S2), confirming the biliary duct nature of both populations. However, a sizable list of genes was gene was differentially expressed between the two populations. A total of 658 genes were upregulated and 241 genes downregulated in the ST14hi population using a false discovery rate (FDR) of <0.1 as the cutoff (Tables 1 and S1); 308 genes were upregulated in the ST14hi population with an FDR of <0.05 and 185 genes were upregulated with an FDR of <0.01. Interestingly, ST14 itself was not differentially expressed at the mRNA level (Table S1), suggesting that the heterogeneity observable at the protein level must be due to post-transcriptional mechanisms (Brazill et al., 2000, Mahmoud et al., 2011, Zhao et al., 2015).

Figure 3.

Transcriptome Analyses of M+ST14hi and M+ST14lo Duct Cells

(A) Kendal's tau unsupervised clustering of RNA-seq data of the M+ST14hi and M+ST14lo populations (n = 4 independent experiments for each population).

(B and C) RNA expression levels of selected individual genes. The y axis indicates RPKM (reads per kilobase per million). N.S., not significant. (B) Prototypical cholangiocyte marker expression levels were comparable in the duct populations. (C) Pkhd1l1, Bmp4, Vim, and Rspo1 are examples of differentially expressed genes.

(D–F) Representation of differentially expressed gene set enrichment analysis categories. (D) Downregulated cell-cycle checkpoint genes. (E) Upregulated in stem cells (BOQUEST) (Boquest et al., 2005). (F) Upregulated in mammary stem cells (Lim et al., 2010).

Table 1.

Selected Genes Differentially Expressed in ST14hi versus ST14lo Cholangiocytes

| Gene | ST14hi (RPKM) | FC (ST14hi/ST14lo) | p Value | FDR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lgals7 | lectin, galactose binding, soluble 7 | 6 | 60 | 1.83 × 10−10 | 0 |

| Sfrp2 | secreted frizzled-related protein 2 | 3.75 | 37.5 | 1.15 × 10−8 | 0 |

| Pkhd1l1 | oolycystic kidney and hepatic disease 1-like 1 | 7.75 | 31 | 1.58 × 10−5 | 0 |

| Lrp2 | low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein | 2.5 | 25 | 1.58 × 10−5 | 0 |

| Mrgprf | G-protein-coupled receptor MrgF | 2.5 | 25 | 2.51 × 10−6 | 0 |

| Krt14 | keratin 14 | 1.75 | 17.5 | 1.61 × 10−5 | 0 |

| Cdh11 | cadherin 11 | 6.75 | 13.5 | 4.61 × 10−15 | 0 |

| Igfbp5 | insulin-like growth factor binding protein 5 | 122.25 | 10.87 | 2.83 × 10−5 | 0 |

| Des | desmin | 12 | 9.6 | 8.69 × 10−6 | 0 |

| Wt1 | Wilms tumor 1 | 6.5 | 8.67 | 1.17 × 10−10 | 0 |

| Rspo1 | R-spondin 1 | 13.25 | 8.25 | 3.61 × 10−5 | 0 |

| Cd34 | CD34 antigen | 16.25 | 8.13 | 1.47 × 10−5 | 0 |

| Cd248 | CD248 antigen, endosialin | 6 | 8 | 3.44 × 10−4 | 0.01 |

| Igfbp6 | insulin-like growth factor binding protein 6 | 77.75 | 7.97 | 3.58 × 10−6 | 0 |

| Wnt2b | Wingless-related MMTV integration site 2b | 7.25 | 7.25 | 2.75 × 10−9 | 0 |

| Ogn | osteoglycin | 10.75 | 6.14 | 1.89 × 10−4 | 0 |

| Bmp4 | bone morphogenetic protein 4 | 7 | 5.6 | 2.95 × 10−7 | 0 |

| Sulf2 | sulfatase 2 | 5.25 | 5.25 | 2.24 × 10−6 | 0 |

| Gas1 | growth arrest specific 1 | 21 | 5.25 | 1.83 × 10−5 | 0 |

| Gpc3 | glypican 3 | 30 | 4.45 | 8.12 × 10−5 | 0 |

| Vim | vimentin | 104.75 | 3.84 | 2.52 × 10−3 | 0.056 |

| Fgf1 | fibroblast growth factor 1 | 10.25 | 3.73 | 6.17 × 10−7 | 0 |

| Onecut1 | one cut domain, family member 1 | 91.25 | 1.8 | 6.02 × 10−4 | 0.02 |

| Klra2 | killer cell lectin-like receptor, subfamily A | 0 | −15 | 5.74 × 10−4 | 0.02 |

| Ccl5 | chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 5 | 0.25 | −11 | 6.46 × 10−3 | 0.1 |

| Pla2g7 | phospholipase A2, group VII | 0.25 | −10 | 2.64 × 10−3 | 0.06 |

| Clec12a | C-type lectin domain family 12, member a | 0.25 | −7 | 4.48 × 10−3 | 0.08 |

| Itgal | integrin alpha L | 0.75 | −5 | 1.69 × 10−3 | 0.04 |

| AF251705 | Cd300D antigen | 0.75 | −4.33 | 1.93 × 10−4 | 0 |

| Folr2 | folate receptor 2 (fetal) | 2.25 | −4.33 | 2.12 × 10−3 | 0.05 |

| Bdkrb1 | bradykinin receptor, beta 1 | 1.25 | −2.8 | 2.14 × 10−3 | 0.05 |

| Cybb | cytochrome b-245, beta polypeptide | 2.75 | −2.64 | 3.03 × 10−4 | 0.01 |

| Cd38 | CD38 antigen | 5.25 | −2.0 | 3.32 × 10−3 | 0.07 |

Gene ontogeny analysis of the differentially expressed genes showed upregulation of genes related to general stem cell properties, mammary stem cells, and hepatoblast pathways in the ST14hi population. This indicates enrichment for stem/progenitor characteristics (Figure 3 and Table S3). In contrast, the cell-cycle checkpoint gene list was downregulated in the ST14hi population (Figure 3D), consistent with their superior colony-forming ability and growth. Stem/progenitor cell-associated regulators such as Wnt2b (7.25-fold) (Flanagan et al., 2015, Goss et al., 2009, Snow et al., 2009), Igfbp5 (10.87-fold) (Liu et al., 2015), Bmp4 (5.60-fold) (Gouon-Evans et al., 2006), and Gpc3 (4.45-fold) (Grozdanov et al., 2006) were more highly expressed in the ST14hi population (Table 1 and Figure 3B). Interestingly, mesenchymal markers such as Vim (3.84-fold), the hepatic stellate cell marker Desmin (9.60-fold), and cell surface marker Cd200 (2.54-fold) were enriched as well (Table 1). Lgr5+ cells have been shown to appear in the liver only after injury (Huch et al., 2013). Consistent with this report, Lgr5 was not expressed in either population of ST14hi cholangiocytes freshly isolated from normal liver. However, Lgr5 gene expression was ∼80-fold higher in the cultured ST14hi organoids compared with the same cells in monolayer culture, while ST14lo organoids did not express Lgr5 (Figure S1H).

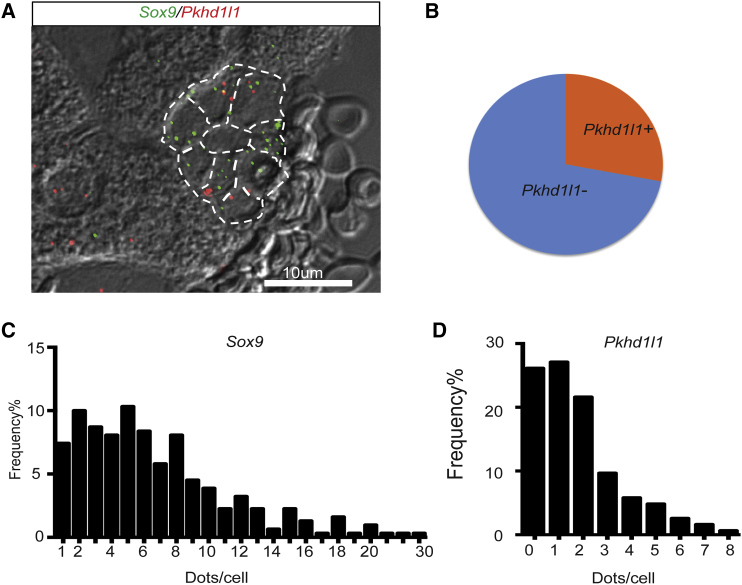

Anatomic Location of Clonogenic Bile Ducts

Having established that adult mouse biliary duct cells have heterogeneous organoid-forming ability, we wished to determine their anatomic location within the liver. The RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) data were mined for marker genes that could be used to visualize the clonogenic bile ducts by RNA fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH). One of the genes most differentially expressed was Pkhd1l1 (Table 1 and Figure 3B), which is highly related to the known liver disease gene Pkhd1 (Zhang et al., 2004). The expression of this gene was 31-fold higher in ST14hi cells than in ST14lo cells. None of the commercially available antibodies to PKHD1L1 we tested produced clear immunofluorescent labeling. Therefore, to find the location of Pkhd1l1 expression within the cholangiocyte compartment, we performed concurrent dual-color in situ hybridization with Pkhd1l1 and Sox9 mRNA. Since RNA-seq revealed that Sox9 was equally expressed in clonogenic and non-clonogenic cholangiocytes, this gene was used as a marker for both duct populations (Figure 4A). Sox9 mRNA was found only in cholangiocytes with about seven to eight signals per cell being detected on average (Figure 4C). In contrast, Pkhd1l1 was expressed in a subpopulation of duct cells (Figure 4D). Only ∼28% of Sox9+ cells were found to express Pkhd1l1 (Figure 4B) (>1 signal/cell), which was consistent with the observed ratio of ST14hi versus ST14lo in MIC1-1C3+ cells as measured by flow cytometry (∼1:3, Figure 1). These data indicate that the clonogenic subpopulation of duct cells is found within normal interlobular portal bile duct structures.

Figure 4.

Clonogenic Cholangiocytes Are Interspersed within Normal Bile Ducts

(A) Representative image of Pkhd1l1 (red) and Sox9 (green) RNA FISH staining. Scale bar, 10 μm.

(B) Venn diagram of the Pkhd1l1+ cells among all Sox9+ duct cells.

(C) Frequency of Sox9 RNA signals per duct cell.

(D) Frequency of Pkhd1l1 RNA signals per duct cell; 60% of cells has either no or one hybridization signal, delineating the negative population.

n = 88 independent experiments from cells in four different mice. Biliary cells were identified by typical morphology in phase-contrast microscopy.

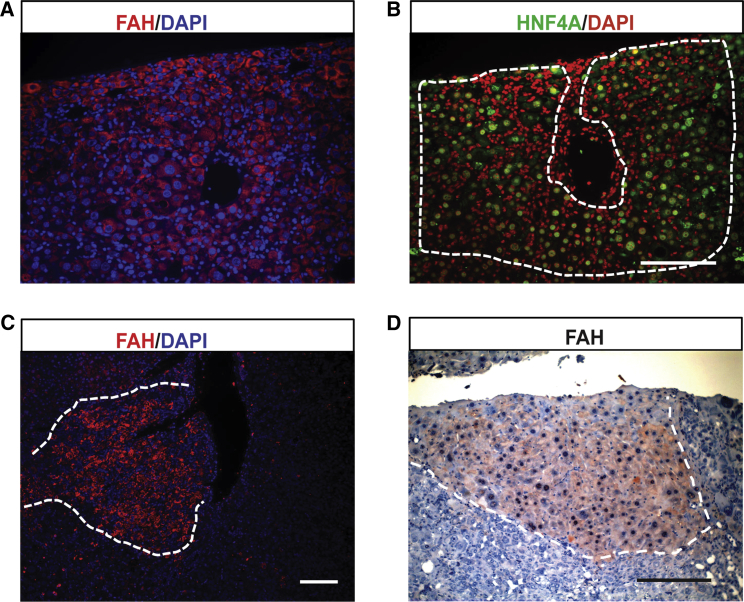

In Vivo Engraftment of Mouse Liver Organoids in FRG/N Mice

To investigate whether ST14hiM+ mouse liver organoids could expand and repopulate damaged liver after transplantation, we dissociated organoids into single cells and performed intrasplenic transplantation of 500,000 cells (>6 passages) per recipient into Fah−/−/Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/−/NOD (FRG/N) mice (n = 8 independent host mice and n = 4 organoid donor mice) as previously described (Azuma et al., 2007, Dorrell et al., 2014, Huch et al., 2013). Of these, four survived NTBC withdrawal. Ten weeks after the transplantation, liver tissues were harvested and labeled to detect hepatocyte markers FAH and HNF4A. Approximately 20 FAH-positive donor-derived hepatocytes nodules were found in each surviving mouse (Figures 5A–5D). Since the host liver does not express FAH, this observation confirms that the hepatic organoids described herein can give rise to hepatocytes and indeed represent the same Lgr5+ population previously reported by us (Dorrell et al., 2014, Huch et al., 2013).

Figure 5.

In Vivo Engraftment of ST14hi-Derived Organoids

(A and B) Immunofluorescent labeling for FAH and HNF4A from serial sections (DAPI stained nuclei as blue).

(C and D) Immunofluorescent (C) and immunohistochemistry (D) staining for FAH (nuclei stained with hematoxylin) in the FRG/N mouse liver. An FAH+ donor-derived nodule of healthy hepatocytes is illustrated.

Scale bars, 100 μm. See also Figure S4.

Discussion

Until recently there was consensus that the adult liver harbors facultative stem cells (Miyajima et al., 2014) which become activated during certain kinds of liver injury, termed oval cell injuries. These facultative liver/stem progenitor cells were deemed to be bipotential, i.e., to give rise to both cholangiocytes and hepatocytes, and be a cell with ductal phenotype located in the canal of Hering. Upon activation, liver stem cells were thought to produce proliferating duct cells (oval cells) and then differentiate into hepatocytes as they migrated out from the portal triad into the hepatic lobule. This previously well-accepted paradigm has now been challenged by lineage-tracing studies performed by several laboratories (Grompe, 2014). Consistently, these studies have shown no significant contribution of oval cells (identified as proliferating duct cells) to the hepatocyte lineage in vivo, at least using the standard injury models in mice.

Other recent studies, however, have demonstrated the existence of a highly proliferative cell resident in normal adult liver that can grow as an Lgr5+ organoid in tissue culture and give rise to hepatocytes upon transplantation, albeit inefficiently. Organoid-forming cells have been found to reside within the ductal compartment (Dorrell et al., 2014, Huch et al., 2015), and exist in both mice (Huch et al., 2013) and humans (Huch et al., 2015). Lineage-tracing studies demonstrated that the organoid-forming cell in adult mouse is derived from a SOX9+ precursor (Tarlow et al., 2014a). Although it is currently unresolved whether the SOX9+ adult liver progenitor can act as a hepatocyte precursor in vivo, these cells can be massively expanded ex vivo. Therefore, they could potentially serve as an abundant source of transplantable cells if their terminal differentiation into hepatocytes could be made efficient.

At most, 1 out of 20 biliary duct cells will form a primary LGR5+ organoid under normal conditions (Dorrell et al., 2014). This observation suggested that this population is heterogeneous and contains a subset of more highly clonogenic cells. Our experiments here clearly demonstrate that cholangiocytes in the adult mouse are indeed functionally heterogeneous and can be subdivided into clonogenic and non-clonogenic subsets. Only the organoids from ST14hi cells could be serially passaged. The small primary organoids from ST14lo duct cells stopped growing after two passages. Our data therefore indicate that the vast majority, if not all, of serially expandable hepatic organoids derive from the ST14hi clonogenic population. The ST14hi and ST14lo populations were not only distinct in their organoid-forming ability but also had clear differences in gene expression. Although classic cholangiocyte genes were not differentially expressed, >10-fold differences were observed in many other transcripts. The genes most highly expressed in the clonogenic subset population are candidates to be novel markers of hepatic progenitors, as they delineate the population that produces Lgr5+ liver organoids. However, it is still uncertain whether the same cells that produce hepatic organoids in culture represent bona fide stem/progenitor cells in vivo. Although clonogenic assays can be useful to isolate progenitors in many systems, we did not perform in vivo lineage tracing of the clonogenic cholangiocytes to formally prove that they are injury-induced stem/progenitor cells. Given the list of differentially expressed genes, however, it should be possible in the future to generate Cre-driver lines to specifically trace the fate of these cells in vivo. Interestingly, none of the many candidate stem cell genes (Table 1) has been previously considered as oval cell or progenitor markers.

Although we did not perform in vivo lineage tracing, we performed experiments to measure the frequency and clonogenicity of our cholangiocyte subsets during injury. Interestingly, neither the percentages nor organoid-forming abilities of the ST14hi/lo populations changed with injury. This could indicate that both populations regenerate equally in vivo despite their different clonogenic properties in vitro. Alternatively, the clonogenic subset may produce both ST14hi and low daughters during injury. The second hypothesis is supported by the observation that single ST14hi cholangiocytes can produce both ST14-high and -low offspring in organoids in vitro. In contrast, ST14lo cells produce only ST14lo offspring in vitro. However, no definite conclusions can be made based on the data presented here, and lineage-tracing studies will be needed to formally evaluate the diverging possibilities.

We used one of the new subset markers, Pkhd1l1, to localize the clonogenic cholangiocytes in the adult liver in situ. Using RNA FISH we found that they are part of the interlobular biliary ducts in the portal triad and appear morphologically identical to regular cholangiocytes. Our analysis was conducted in only two dimensions and it was therefore not possible to clearly discern whether the Pkhd1l1 cells were in the canal of Hering. Future detailed three-dimensional reconstructions should resolve this question.

Our data are consistent with a recent report demonstrating heterogeneity in proliferative capacity among cholangiocytes in vivo (Kamimoto et al., 2016). In fact the observed frequency of clonogenic duct cells and their anatomic location within the liver fit our observations well. It can be speculated that the ST14hi population reported here may represent the same cells giving rise to large biliary duct clones by lineage tracing in vivo. However, our results also indicate differences from the model proposed by Kamimoto et al. (2016). The consistent differences in gene expression between clonogenic and non-clonogenic cholangiocytes found by us suggest inherent differences between the two populations. This is in contrast to the stochastic activation model of a homogeneous population of cholangiocytes proposed by those authors. Interestingly, the existence of distinct populations differing in growth potential has recently also been suggested for hepatocytes (Font-Burgada et al., 2015, Wang et al., 2015). It is currently unclear for both cholangiocytes and hepatocytes whether the different populations reflect different developmental lineages or whether niche signals are responsible for the divergent phenotypes.

Interestingly, we also found that organoid-forming cells were highly ischemia resistant and retained their clonogenic properties for at least 24 hr after death even at room temperature. This suggests that cadaveric tissue sources could potentially be used to establish expandable cultures of these cells, even from non-beating heart donors. This property makes liver organoids a potentially attractive source of transplantable allogeneic hepatocytes in the future, but only if their hepatocytic differentiation can be made more efficient than it is today. Indeed, the Fah transplantation studies reported here confirmed that the organoids have only rather limited hepatocytic potential. The number of FAH+ hepatocyte nodules per input cell was much lower than is seen with transplantation of mature hepatocytes. The development of more efficient protocols to convert expanded organoids into mature hepatocytes should be a research priority for the future.

Experimental Procedures

Animals and Liver Cell Preparation

Eight-week-old C57B/L6 male mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. All animal experimentation was conducted in accordance with protocol IS000000788 of the institutional review committee at Oregon Health and Science University. To produce single liver cell suspensions for FACS, we perfused mouse livers with 0.5 mM EGTA (Fisher) followed by collagenase (Worthington Biochemical), as described previously (Dorrell et al., 2011).

Cell Sorting and Culture

The isolation of defined non-parenchymal cell subpopulations from adult mouse liver was performed as described previously (Dorrell et al., 2011) with some modifications. In brief, cells were incubated at 4°C for 30 min with MIC1-1C3 hybridoma supernatant at a dilution of 1:20 and anti-human ST14 (Abcam) at a concentration of 1:100. For co-staining of CD133 and ST14, biotinylated anti-CD133 (eBioscience) was used. After a wash with cold PBS containing 3% fetal bovine serum, cells were labeled with phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated donkey anti-rat and DL647-counjugated donkey anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (Jackson Immunoresearch) and allophycocyanin (APC)-Cy7-conjugated streptavidin (BD Biosciences). After another wash, the secondary antibody was blocked by a 10-min incubation in DMEM containing 5% rat serum. Cells were then incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-CD26 (BD Biosciences) and PE-Cy7-conjugated anti-CD45 (BD Biosciences), anti-CD11b/Mac1 (BD Biosciences), and anti-CD31 (BD Biosciences) to collectively mark hematopoietic and endothelial cells for exclusion. After a final wash, cells were resuspended in holding buffer containing propidium iodide (1 μg mL−1) and then analyzed and sorted with a Cytopeia influx-GS (Becton Dickinson). Flow-cytometry data were analyzed by FlowJo (Treestar). For FACS gating, isotype control stained with secondary anti-rabbit APC and anti-rat PE only were used for negative gates. Sorted populations were mixed with Matrigel (BD Bioscience) and seeded and cultured as described previously (Huch et al., 2013) with minor modifications. Culture medium consisted of Advanced DMEM/F12 (Invitrogen) supplemented with B27 and N2 (Invitrogen), 1.25 μM N-acetylcysteine (Sigma-Aldrich), SB431542, and the following growth factors: 50 ng mL−1 EGF (Peprotech), 10% RSPO1 conditioned medium (Huch et al., 2013), 100 ng mL−1 FGF10 (Peprotech), 10 mM nicotinamide (Sigma-Aldrich), and 50 ng mL−1 HGF (Peprotech), 100 ng mL−1 Noggin, and Wnt3a (R&D Systems). For the single-cell assay, cells were sorted directly into organoid medium containing 5% Matrigel in non-tissue culture-treated 96-well plates at a density of 1 cell/well. On culture day 14, organoids were trypsinized with TrypLE (Gibco) and replated into 50 μL of Matrigel droplets in a 24-well plate for further expansion. All of the antibodies are listed in Table S4.

RNA Sequencing

Cells were directly sorted and added into TRIzol-LS for RNA extraction. Libraries were made with the Illumina TruSeq protocol following the manufacturer's protocol. Four samples for each population were processed to assure robust comparisons. The sequence reads were trimmed to 44 bases and aligned to the mouse genome NCBI37/mm9 using Bowtie (an ultrafast memory-efficient short-read aligner) version 0.12.7 (Langmead et al., 2009). We used custom scripts to count sequences in exons annotated for RefSeq mouse genes. DESeq2 (Love et al., 2014) was used to calculate the significance of differentially expressed genes based on these counts. Data were analyzed by gene set enrichment analysis (Mootha et al., 2003, Subramanian et al., 2005), and FDRs <0.25 were considered to be significant. The RNA-seq FASTQ data were submitted to the NCBI GEO.

Liver Repopulation Assay

The transplantations of ductal cell-derived organoids to Fah-deficient mice were performed as described previously (Dorrell et al., 2011, Huch et al., 2013) with some modifications. Briefly, Fah−/−/Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− (FRGN) mice (Azuma et al., 2007) were pretreated with a urokinase-type plasminogen activator adenovirus 48 hr before transplantation. Before transplantation, liver organoids were exposed to a hepatocytic differentiation medium as described by Huch et al. (2015). NTBC was withdrawn from recipient animals following transplantation, and weight was monitored daily. Upon reaching 80% of their normal weight, NTBC was readministered until health was restored. After four cycles of NTBC withdrawal, mice were euthanized for immunohistochemical assessment of liver engraftment.

Immunofluorescence

Fresh mouse and human tissues were embedded in OCT compound (Sakura) and sectioned for immunofluorescence. Tissue sections were cut at 7 μm and fixed in acetone for 15 min. After washing in 0.05% PBS-Tween 20, sections were blocked at room temperature for 1 hr with 5% serum corresponding to the host species of the secondary antibody. Primary antibody was applied to tissue sections at 4°C overnight. After washing, tissue sections were stained with secondary antibodies as listed in Table S1. Tissue imaging was observed with Zeiss LSM 700 confocal microscope.

RNA Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization

Fresh frozen tissue was embedded in OCT compound and sectioned at 10 μm thickness. RNA in situ hybridization was performed using RNAscope (ACDbio) following the manufacturer's protocol. Sox9 and Pkhd1l1 probes were purchased from ACDbio. Tissues were imaged in a Deltavision CoreDV Widefield Deconvolution microscope. More than 300 individual duct cells from three mice were scored for signal enumeration.

RNA Isolation and qRT-PCR

Cells were FACS-sorted directly into TRI Reagent LS (MRC, catalog #TS120). RNA was extracted with isopropanol and immediately treated with DNase I (Thermo Fisher). cDNA was synthesized with the M-MLV reverse transcription kit (Thermo Fisher). Organoids were lysed into TRIzol (Thermo Fisher, #15596). Relative mRNA expression levels were assessed by qRT-PCR using the LightCycler96 real-time PCR system (Roche). Primer sequences are: mouse Lgr5 forward 5′-AGT TAT AAC AGC TGG GTT GGC-3′, reverse 5′-GGA AGT CAT CAA GGT TAT TAT AA-3′; mouse Gapdh forward 5′-AAG GTC GGT GTG AAC GGA TTT GG-3′, reverse 5′-CGT TGA ATT TGC CGT GAG TGG AG-3′.

Statistical Analyses

All data are presented as mean ± SD. GraphPad Prism software was used for statistical analyses. p < 0.05 and p < 0.01 were considered to be statistically significant and highly significant, respectively.

Author Contributions

B.L. and M.G. designed the experiments and wrote the manuscript. C.D. and P.S.C. assisted with the flow cytometry-related experiments. C.P. designed and generated the RNA-seq analysis data. A.H. assisted with the transplantation. M.F. carried out the Fah immunohistochemistry.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants R01-DK051592 and R01 DK083355 to M.G. The authors thank OHSU core services Massively Parallel Sequencing Shared Resource, OHSU Flow Cytometry Shared Resources, Histopathology Shared Resources, and Advanced Light Microscopy core. We thank Milton Finegold and Angela Major for histology assistance. We also thank Leslie Wakefield, Devorah Goldman, Qingshuo Zhang, Yuhan Wang, and Branden Tarlow for their excellent technical assistance. M.G. is a founder and shareholder of Yecuris. OHSU has commercially licensed MIC1-1C3; authors C.D. and M.G. are inventors of this antibody. This potential conflict of interest has been reviewed and managed by OHSU.

Published: July 6, 2017

Footnotes

Supplemental Information includes four figures and four tables and can be found with this article online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.stemcr.2017.06.003.

Accession Numbers

RNA-seq fastq files are available from the NCBI GEO under accession number GEO: GSE73897.

Supplemental Information

References

- Azuma H., Paulk N., Ranade A., Dorrell C., Al-Dhalimy M., Ellis E., Strom S., Kay M.A., Finegold M., Grompe M. Robust expansion of human hepatocytes in Fah−/−/Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− mice. Nat. Biotechnol. 2007;25:903–910. doi: 10.1038/nbt1326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker N., van Es J.H., Kuipers J., Kujala P., van den Born M., Cozijnsen M., Haegebarth A., Korving J., Begthel H., Peters P.J. Identification of stem cells in small intestine and colon by marker gene Lgr5. Nature. 2007;449:1003–1007. doi: 10.1038/nature06196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker N., Huch M., Kujala P., van de Wetering M., Snippert H.J., van Es J.H., Sato T., Stange D.E., Begthel H., van den Born M. Lgr5(+ve) stem cells drive self-renewal in the stomach and build long-lived gastric units in vitro. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;6:25–36. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boquest A.C., Shahdadfar A., Fronsdal K., Sigurjonsson O., Tunheim S.H., Collas P., Brinchmann J.E. Isolation and transcription profiling of purified uncultured human stromal stem cells: alteration of gene expression after in vitro cell culture. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2005;16:1131–1141. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-10-0949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brazill D.T., Caprette D.R., Myler H.A., Hatton R.D., Ammann R.R., Lindsey D.F., Brock D.A., Gomer R.H. A protein containing a serine-rich domain with vesicle fusing properties mediates cell cycle-dependent cytosolic pH regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:19231–19240. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000900200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorrell C., Erker L., Lanxon-Cookson K.M., Abraham S.L., Victoroff T., Ro S., Canaday P.S., Streeter P.R., Grompe M. Surface markers for the murine oval cell response. Hepatology. 2008;48:1282–1291. doi: 10.1002/hep.22468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorrell C., Erker L., Schug J., Kopp J.L., Canaday P.S., Fox A.J., Smirnova O., Duncan A.W., Finegold M.J., Sander M. Prospective isolation of a bipotential clonogenic liver progenitor cell in adult mice. Genes Dev. 2011;25:1193–1203. doi: 10.1101/gad.2029411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorrell C., Tarlow B., Wang Y., Canaday P.S., Haft A., Schug J., Streeter P.R., Finegold M.J., Shenje L.T., Kaestner K.H. The organoid-initiating cells in mouse pancreas and liver are phenotypically and functionally similar. Stem Cell Res. 2014;13:275–283. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2014.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan A.W., Dorrell C., Grompe M. Stem cells and liver regeneration. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:466–481. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.05.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erker L., Azuma H., Lee A.Y., Guo C., Orloff S., Eaton L., Benedetti E., Jensen B., Finegold M., Willenbring H. Therapeutic liver reconstitution with murine cells isolated long after death. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:1019–1029. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.05.082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espanol-Suner R., Carpentier R., Van Hul N., Legry V., Achouri Y., Cordi S., Jacquemin P., Lemaigre F., Leclercq I.A. Liver progenitor cells yield functional hepatocytes in response to chronic liver injury in mice. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:1564–1575.e7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evarts R.P., Nagy P., Nakatsukasa H., Marsden E., Thorgeirsson S.S. In vivo differentiation of rat liver oval cells into hepatocytes. Cancer Res. 1989;49:1541–1547. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan D.J., Phesse T.J., Barker N., Schwab R.H., Amin N., Malaterre J., Stange D.E., Nowell C.J., Currie S.A., Saw J.T. Frizzled7 functions as a Wnt receptor in intestinal epithelial Lgr5(+) stem cells. Stem Cell Reports. 2015;4:759–767. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2015.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Font-Burgada J., Shalapour S., Ramaswamy S., Hsueh B., Rossell D., Umemura A., Taniguchi K., Nakagawa H., Valasek M.A., Ye L. Hybrid periportal hepatocytes regenerate the injured liver without giving rise to cancer. Cell. 2015;162:766–779. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.07.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golding M., Sarraf C.E., Lalani E.N., Anilkumar T.V., Edwards R.J., Nagy P., Thorgeirsson S.S., Alison M.R. Oval cell differentiation into hepatocytes in the acetylaminofluorene-treated regenerating rat liver. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:1182–1190. doi: 10.1016/0270-9139(95)90635-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goss A.M., Tian Y., Tsukiyama T., Cohen E.D., Zhou D., Lu M.M., Yamaguchi T.P., Morrisey E.E. Wnt2/2b and beta-catenin signaling are necessary and sufficient to specify lung progenitors in the foregut. Dev. Cell. 2009;17:290–298. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouon-Evans V., Boussemart L., Gadue P., Nierhoff D., Koehler C.I., Kubo A., Shafritz D.A., Keller G. BMP-4 is required for hepatic specification of mouse embryonic stem cell-derived definitive endoderm. Nat. Biotechnol. 2006;24:1402–1411. doi: 10.1038/nbt1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grompe M. Liver stem cells, where art thou? Cell Stem Cell. 2014;15:257–258. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grozdanov P.N., Yovchev M.I., Dabeva M.D. The oncofetal protein glypican-3 is a novel marker of hepatic progenitor/oval cells. Lab. Invest. 2006;86:1272–1284. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huch M., Dorrell C., Boj S.F., van Es J.H., Li V.S., van de Wetering M., Sato T., Hamer K., Sasaki N., Finegold M.J. In vitro expansion of single Lgr5+ liver stem cells induced by Wnt-driven regeneration. Nature. 2013;494:247–250. doi: 10.1038/nature11826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huch M., Gehart H., van Boxtel R., Hamer K., Blokzijl F., Verstegen M.M., Ellis E., van Wenum M., Fuchs S.A., de Ligt J. Long-term culture of genome-stable bipotent stem cells from adult human liver. Cell. 2015;160:299–312. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.11.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamimoto K., Kaneko K., Kok C.Y., Okada H., Miyajima A., Itoh T. Heterogeneity and stochastic growth regulation of biliary epithelial cells dictate dynamic epithelial tissue remodeling. Elife. 2016;5 doi: 10.7554/eLife.15034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koo B.K., Clevers H. Stem cells marked by the R-spondin receptor LGR5. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:289–302. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B., Trapnell C., Pop M., Salzberg S.L. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol. 2009;10:R25. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim E., Wu D., Pal B., Bouras T., Asselin-Labat M.L., Vaillant F., Yagita H., Lindeman G.J., Smyth G.K., Visvader J.E. Transcriptome analyses of mouse and human mammary cell subpopulations reveal multiple conserved genes and pathways. Breast Cancer Res. 2010;12:R21. doi: 10.1186/bcr2560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D., Wang Y., Jia Z., Wang L., Wang J., Yang D., Song J., Wang S., Fan Z. Demethylation of IGFBP5 by histone demethylase KDM6B promotes mesenchymal stem cell-mediated periodontal tissue regeneration by enhancing osteogenic differentiation and anti-inflammation potentials. Stem Cells. 2015;33:2523–2536. doi: 10.1002/stem.2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love M.I., Huber W., Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15:550. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoud L., Al-Saif M., Amer H.M., Sheikh M., Almajhdi F.N., Khabar K.S. Green fluorescent protein reporter system with transcriptional sequence heterogeneity for monitoring the interferon response. J. Virol. 2011;85:9268–9275. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00772-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyajima A., Tanaka M., Itoh T. Stem/progenitor cells in liver development, homeostasis, regeneration, and reprogramming. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;14:561–574. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mootha V.K., Lindgren C.M., Eriksson K.F., Subramanian A., Sihag S., Lehar J., Puigserver P., Carlsson E., Ridderstrale M., Laurila E. PGC-1alpha-responsive genes involved in oxidative phosphorylation are coordinately downregulated in human diabetes. Nat. Genet. 2003;34:267–273. doi: 10.1038/ng1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paku S., Schnur J., Nagy P., Thorgeirsson S.S. Origin and structural evolution of the early proliferating oval cells in rat liver. Am. J. Pathol. 2001;158:1313–1323. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64082-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaub J.R., Malato Y., Gormond C., Willenbring H. Evidence against a stem cell origin of new hepatocytes in a common mouse model of chronic liver injury. Cell Rep. 2014;8:933–939. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snow G.E., Kasper A.C., Busch A.M., Schwarz E., Ewings K.E., Bee T., Spinella M.J., Dmitrovsky E., Freemantle S.J. Wnt pathway reprogramming during human embryonal carcinoma differentiation and potential for therapeutic targeting. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:383. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian A., Tamayo P., Mootha V.K., Mukherjee S., Ebert B.L., Gillette M.A., Paulovich A., Pomeroy S.L., Golub T.R., Lander E.S. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:15545–15550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarlow B.D., Finegold M.J., Grompe M. Clonal tracing of Sox9(+) liver progenitors in mouse oval cell injury. Hepatology. 2014;60:278–289. doi: 10.1002/hep.27084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarlow B.D., Pelz C., Naugler W.E., Wakefield L., Wilson E.M., Finegold M.J., Grompe M. Bipotential adult liver progenitors are derived from chronically injured mature hepatocytes. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;15:605–618. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B., Zhao L., Fish M., Logan C.Y., Nusse R. Self-renewing diploid Axin2(+) cells fuel homeostatic renewal of the liver. Nature. 2015;524:180–185. doi: 10.1038/nature14863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanger K., Zong Y., Maggs L.R., Shapira S.N., Maddipati R., Aiello N.M., Thung S.N., Wells R.G., Greenbaum L.E., Stanger B.Z. Robust cellular reprogramming occurs spontaneously during liver regeneration. Genes Dev. 2013;27:719–724. doi: 10.1101/gad.207803.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M.Z., Mai W., Li C., Cho S.Y., Hao C., Moeckel G., Zhao R., Kim I., Wang J., Xiong H. PKHD1 protein encoded by the gene for autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease associates with basal bodies and primary cilia in renal epithelial cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:2311–2316. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400073101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao N., Nizzi C.P., Anderson S.A., Wang J., Ueno A., Tsukamoto H., Eisenstein R.S., Enns C.A., Zhang A.S. Low intracellular iron increases the stability of matriptase-2. J. Biol. Chem. 2015;290:4432–4446. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.611913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.