Nussbaum et al. found that tumor suppression through innate lymphoid cells (ILCs) cannot be predicted solely based on the ILC phenotype and lineage but that their immune properties are shaped both by their ontogeny and by the tissue microenvironment they reside in.

Abstract

Innate lymphoid cells (ILCs) have been classified into “functional subsets” according to their transcription factor and cytokine profiles. Although cytokines, such as IL-12 and IL-23, have been shown to shape plasticity of ILCs, little is known about how the tissue microenvironment influences the plasticity, phenotype, and function of these cells. Here, we show clearly demarcated tissue specifications of Rorc-dependent ILCs across lymphoid and nonlymphoid organs. Although intestinal Rorc fate map–positive (Rorcfm+) ILCs show a clear ILC3 phenotype, lymphoid tissue–derived Rorcfm+ ILCs acquire an natural killer (NK) cell/ILC1-like phenotype. By adoptively transferring Rorcfm+ ILCs into recipient mice, we show that ILCs distribute among various organs and phenotypically adapt to the tissue environment they invade. When investigating their functional properties, we found that only lymphoid-tissue resident Rorcfm+ ILCs can suppress tumor growth, whereas intestinal Rorcfm− ILC1s or NK cells fail to inhibit tumor progression. We thus propose that the tissue microenvironment, combined with ontogeny, provides the specific function, whereas the phenotype is insufficient to predict the functional properties of ILCs.

Introduction

Innate lymphoid cells (ILCs) are a growing family of innate lymphocytes with diverse phenotypic and functional properties (Spits et al., 2013). They have a critical role in various processes, such as the development of lymphoid structures, the generation and maintenance of immune homeostasis especially at mucosal sites, tissue remodeling, and the maintenance of epithelial integrity (Finke et al., 2002; Fukuyama et al., 2002; Monticelli et al., 2011; Mchedlidze et al., 2013; Goto et al., 2014). However, they have also been implicated in the control and suppression of solid tumors (Eisenring et al., 2010; Ikutani et al., 2012; Kirchberger et al., 2013; Bie et al., 2014; Chan et al., 2014; Carrega et al., 2015; Crome et al., 2017; Irshad et al., 2017).

Group 1 ILCs include NK cells and other non-NK ILC1 cells, all expressing the transcription factor T-bet and secreting IFN-γ when stimulated with IL-12, IL-15, or IL-18 (Fuchs and Colonna, 2013; Klose et al., 2014). Despite their similarities to NK cells in transcription factor profiles and cytokine expression, the role of ILC1s in tumor surveillance remains to be established. ILC2s produce type 2 cytokines, such as IL-5 and IL-13, and have been implicated in both tumor surveillance and tumorigenesis. Thus, whereas induction of IL-13 by IL-33 in ILC2s promotes tumor growth in two distinct mouse models (Jovanovic et al., 2014; Li et al., 2014), anti-tumor activity against lung metastasis requires IL-5 production by ILC2s (Ikutani et al., 2012).

Genetic fate mapping identifies type 3 ILCs by the expression of retinoic acid-receptor-related orphan receptor (ROR)γt during their emergence (Eberl and Littman, 2004). These ILC3s include C-C chemokine receptor (CCR)6+ ILC3s (mainly representing lymphoid tissue inducer cells [LTi’s]), CCR6− natural cytotoxicity receptor (NCR)+ ILC3s, and CCR6−NCR− ILC3s (Klose et al., 2013). ILC3s have also been reported to have pro- or antitumorigenic effects in different experimental setups. They were shown to promote bacteria-induced colon cancers in an IL-22–dependent manner, and IL-23 stimulation induces de novo development of intestinal adenomas (Kirchberger et al., 2013; Chan et al., 2014). In contrast, type 3 ILCs have been implicated in tumor suppression in a model of malignant melanoma (Eisenring et al., 2010). In that particular study, IL-12 was responsible for the tumor-suppressive capacity of Rorcfm+ ILCs (Eisenring et al., 2010). The tumor-suppressive cytokine IL-12 was previously described to promote T-bet expression resulting in the loss of RORγt-inducing so-called “ex-ILC3s,” which are phenotypically similar to ILC1s (Vonarbourg et al., 2010). In addition, IL-12 induces a reversible differentiation of human intestinal ILC3s and ILC2 cells into type 1–like ILCs under inflammatory conditions (Bernink et al., 2015; Bal et al., 2016; Lim et al., 2016; Ohne et al., 2016; Silver et al., 2016). Besides the nonredundant role of this cytokine in the plasticity of ILC subsets, little is known about the role of the tissue microenvironment in delineating phenotypic and functional ILC fate. Therefore, whether the functional ILC fate is shaped not only during its lineage commitment but also by the tissue microenvironment is currently unclear.

By systematically interrogating one functional property of tissue-resident ILCs, namely IL-12–mediated tumor-suppressive capacity, we observed that the specific tissue microenvironment determines the fate and function of distinct Rorcfm+ ILCs subtypes. Intestinal Rorcfm+ ILCs predominantly retained expression of RORγt, whereas progeny of the same precursor migrating into lymphoid tissues up-regulated T-bet and acquired potent tumor-suppressive properties. We thus propose that the individual tissue microenvironment shapes the functional specialization of ILCs. Of note, conventional NK cells and bona fide ILC1s, despite being highly responsive to IL-12, did not have tumor-suppressive activity, suggesting that tissue microenvironment-induced plasticity combined with ontogeny and early transcriptional imprinting determines ILC function.

Results

Rorcfm+ ILCs reside in various tissues and adapt to the local microenvironment

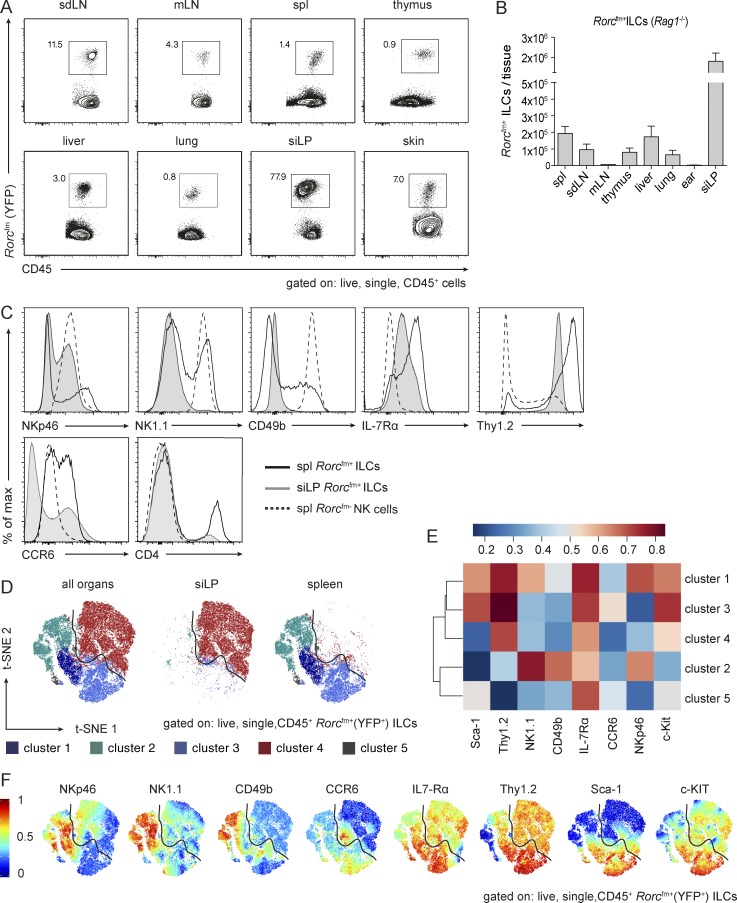

ILC3s express the transcription factor RORγt and regulate various immune responses, most prominently within the intestinal tract (Sanos et al., 2009; Mortha et al., 2014; Bernink et al., 2015; Hepworth et al., 2015). Other than barrier-tissue immunity and their role in lymphoid organogenesis, little is known about the prevalence and function of RORγt-dependent ILCs. Therefore, we characterized the progeny of RORγt-dependent ILC precursors in various lymphoid and nonlymphoid tissues in steady state with multiparametric flow-cytometry analysis (Fig. 1 A). We took advantage of genetic fate mapping using Rorc-CreTg;Rosa26ReYFP/+ mice (from now an referred to as Rorcfm mice; Eberl and Littman, 2004), in which all cells that expressed RORγt at any time during their development, as well as in their progeny, are permanently marked with YFP (hereafter, called Rorcfm+ cells). By crossing Rorcfm mice onto a Rag1−/− background, we eliminated all canonical fate-mapped cells (i.e., T lymphocytes) and exclusively labeled TCR-negative Rorcfm+ ILC. The frequencies and total cell numbers of Rorcfm+ ILCs in steady state were expectedly highest in the small intestine (Fig. 1, A and B; and Fig. S1, A and B). However, we found significant numbers of Rorcfm+ ILCs in the thymus and secondary lymphoid organs as well, including skin-draining LNs, mesenteric LNs, and spleen, and in nonlymphoid organs, such as liver, lung, and skin.

Figure 1.

ILCs reside in various tissues and Rorcfm+ ILCs from spleen and small intestine cluster in demarcated cluster sets. (A) Flow cytometric analysis to identify Rorcfm+ ILCs in various organs of Rorcfm-Rag1−/− mice, including lymphoid organs, such as skin-draining LNs (sdLN), mesenteric LNs (mLN), spleen (spl), and thymus as well as nonlymphoid organs, such as the liver, lung, siLP, and skin in a steady state. Representative graphs of two independent experiments, n ≥ 4 each. (B) Total counts of Rorcfm+ ILCs within the CD45 compartment of various organs of Rorcfm-Rag1−/− mice (skin represents total counts of two ears). Graphs represent pooled data from two independent experiments, n ≥ 4 each (means ± SEM). (C) Histogram overlay of splenic (spl) Rorcfm+ ILCs (black continuous line), siLP Rorcfm+ ILCs (gray continuous line), and splenic (spl) Rorcfm- NK cells (dotted line). Representative histograms of four independent experiments, n ≥ 5 each. (D) Dimensionality reduction using t-SNE. Data from 4 × 104 Rorcfm+ ILCs of spleen and siLP (gated on live, single CD45+Rorcfm+ ILCs) were transformed and plotted in two t-SNE dimensions using R software. Clustering was performed using the flowSOM algorithm (k = 5). Depicted are the combined spleen and siLP data sets (left), the siLP data set only (middle), and the spleen data set only (right). (E) ILC3-associated and NK cell–associated markers plotted in a heat map across flowSOM clusters from D. (F) Expression pattern of ILC3-associated and NK cell–associated markers depicted in the two t-SNE dimensions.

To further characterize Rorcfm+ ILCs of distinct tissues, we performed phenotypic profiling with ILC and NK cell markers, revealing vast differences in Rorcfm+ ILCs of various organs, in particular, between lymphoid and nonlymphoid tissues (Fig. S1 C). We chose a representative lymphoid tissue (i.e., spleen) and nonlymphoid tissue (i.e., small intestinal lamina propria [siLP]) for further detailed analysis (Fig. 1 C). Lymphoid tissue–resident Rorcfm+ ILCs express high levels of NK cell–associated markers, such as NKp46, NK1.1, and CD49b and, thus, phenotypically resemble NK cells, even though they clearly arise from a distinct lineage (as defined by Rorcfm). In contrast, intestinal Rorcfm+ ILCs homogenously express IL-7Rα and Thy1.2, heterogeneously express NKp46, but are mostly negative for NK1.1 and CD49b (Fig. 1 C).

Numerous lineage-defining markers for the different ILC subsets have been proposed, with some degree of uncertainty as to whether each subset represents a stable lineage (Spits et al., 2013). Given the apparent heterogeneity and/or plasticity, we decided to use a computer-aided clustering approach for the unsupervised identification of distinct fates and phenotypes of RORγt-dependent ILCs. Therefore, CD45+Rorcfm+ ILCs of spleen and siLP—without any further pregating—were fed into the dimensionality reduction algorithm t-stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE), followed by analysis of the combined data sets with flowSOM (k = 5). Strikingly, the unsupervised clustering separated splenic and siLP Rorcfm+ ILCs into clearly demarcated cluster sets (Fig. 1 D). Although almost all siLP Rorcfm+ ILCs grouped together in one separate cluster (cluster 4), splenic ILCs were split into 4 clusters (cluster 1–3 and 5), indicating greater diversity among splenic subsets of type 3 ILCs compared with siLP ILC3s.

As shown previously (Fig. 1 C), siLPs (represented in cluster 4) express mainly ILC3-associated markers (Fig. 1, E and F). The splenic ILC clusters could be matched to previously described ILC3 subsets. Cluster 1 represents so-called CCR6−NCR+ ILC3s (Klose et al., 2013), whereas cluster 3 resembles CCR6+ ILCs (Klose et al., 2013). Because of the high expression of NK cell markers and the low expression of ILC3-associated markers, cluster 2 may represent “ex-ILC3s,” whereas cells of cluster 5 may hold LTi-like cells expressing IL-7Rα, low levels of c-Kit, Sca-1, and CCR6 (compare CCR6 expression map of Fig. 1 F), but no NK cell markers. Of note, similar splenic Rorcfm+ ILCs clusters were found regardless of whether they were analyzed in WT or Rag-deficient mice (Fig. S1, D–F). These data reveal the distinct characteristics of splenic Rorcfm+ ILCs and siLP Rorcfm+ ILCs, despite sharing the same lineage, and suggest a phenotypic specialization of Rorcfm+ ILCs driven by the tissue microenvironment.

The tissue microenvironment determines the fate of type 3 ILCs

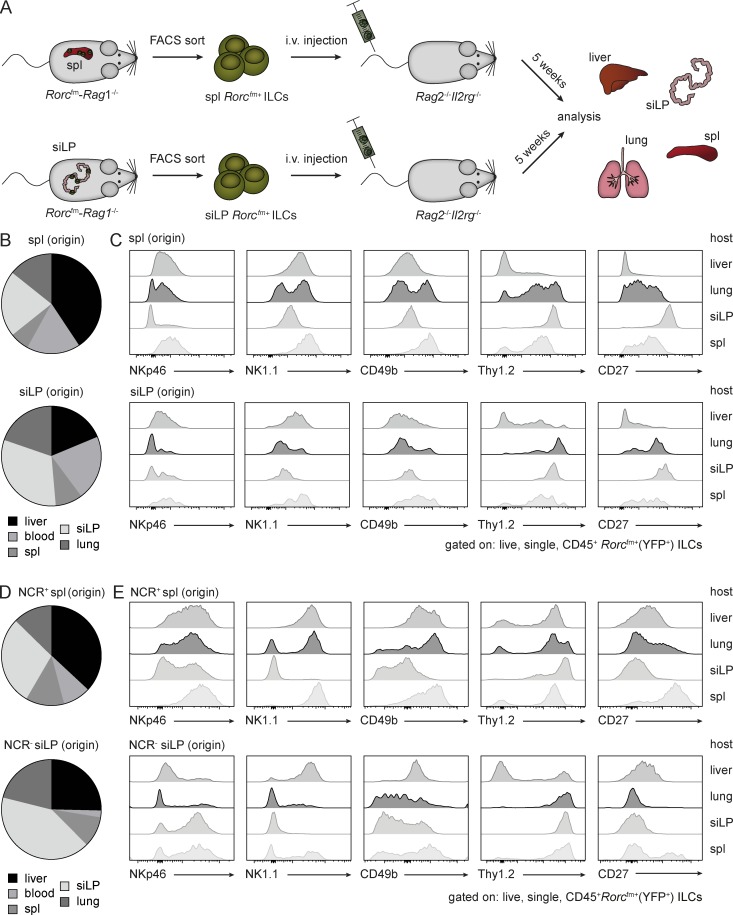

Whether the phenotypic specialization of Rorcfm+ ILCs from various organs is stable over time or whether these phenotypes are plastic and imprinted by the local tissue microenvironment is a matter of speculation. To interrogate the plasticity of type 3 ILCs, we adoptively transferred Rorcfm+ ILCs isolated from various organs into Rag2−/−Il2rg−/− mice, allowing tissue homing akin to the homeostatic expansion of T lymphocytes in a lymphopenic environment (Fig. 2 A). Regardless of the tissue from which the Rorcfm+ ILCs were isolated, they stochastically homed to various organs. Rorcfm+ ILCs isolated, for example, from the spleen did not “home” specifically into the spleen but were similarly disseminated across all examined organs. Conversely, Rorcfm+ ILCs isolated from the small intestine, likewise, colonized lymphoid and nonlymphoid organs, without the predisposition to home into the gut (Fig. 2 B). Importantly, the phenotypic properties and expression of lineage markers of adoptively transferred Rorcfm+ ILCs depended on the local tissue environment they encountered and not on their origin (Fig. 2 C). In other words, Rorcfm+ ILCs colonizing the spleen expressed NK cell-associated markers (Fig. 2 C); Rorcfm+ ILCs colonizing the small intestine adopted the phenotype of ILC3s by expressing, for example, Thy1.2 but no NK cell-associated markers (Fig. 2 C). To investigate whether this phenomenon was caused by selective migration (and/or survival) of a stable subpopulation or was indeed stochastic, we sorted NCR+ ILC1-like (NKp46+NK1.1+Rorcfm+ ILCs) or NCR−ILC3s (NKp46−NK1.1−Rorcfm+ ILCs) cells and adoptively transferred them into Rag2−/−Il2rg−/− mice. As with unfractionated Rorcfm+ ILCs, we found no clear homing preferences of the purified subsets but observed a distribution across various organs (Fig. 2 D). Moreover, both subpopulations changed their phenotypes according to the organs they encountered, thus favoring the notion of site-specific, plastic behavior over selective migration or survival of a specific ILC subset.

Figure 2.

The tissue microenvironment dictates the fate of Rorcfm+ ILCs. (A) Schematic representation of the experimental setup. Rorcfm+ ILCs from spleen (spl) or siLP of Rorcfm-Rag1−/− mice were isolated using flow cytometric cell sorting and adoptively transferred into lymphopenic Rag2−/−Il2rg−/− mice. After 5 wk, various organs were analyzed. (B) Distribution of adoptively transferred Rorcfm+ ILCs of splenic (spl, top) and siLP (bottom) origin, homing to various organs (clockwise: liver, blood, spleen, siLP, or lung) within Rag2−/−Il2rg−/− mice. Graphs represent pooled data from three independent experiments, n ≥ 3 each. (C) Flow cytometric analysis of live, single, CD45+Rorcfm+ ILCs originating from spleen (spl, top) or siLP (bottom) after 5 wk of expansion in Rag2−/−Il2rg−/− mice. Graphs represent pooled data from three independent experiments, n ≥ 3 each. (D) Distribution of adoptively transferred highly purified splenic NCR+ (NKp46+NK1.1+) Rorcfm+ ILCs (top) and NCR− (NKp46−NK1.1−) siLP Rorcfm+ ILCs (bottom), homing to various organs (clockwise: liver, blood, spleen, siLP, or lung) within Rag2−/−Il2rg−/− mice. Graphs represent pooled data from two to five independent experiments, n ≥ 5. (D) Flow cytometric analysis of spleen-derived NCR+Rorcfm+ ILCs (top) or siLP-derived NCR−Rorcfm+ ILCs (bottom) after 5 wk of expansion in Rag2−/−Il2rg−/− mice (gated on live, single, CD45+ Rorcfm+ ILCs). Representative histograms from two to five independent experiments, n ≥ 5.

Taken together, these results reveal that the tissue microenvironment in the steady state provides strong guidance cues for the phenotypic adaptation of ILCs to the individual tissue. This raises the question of whether the phenotypic changes driven by the tissue microenvironment also translate into functional differences regarding cytokine responsiveness and tumor protection.

The tissue microenvironment dictates the function of Rorcfm+ ILCs

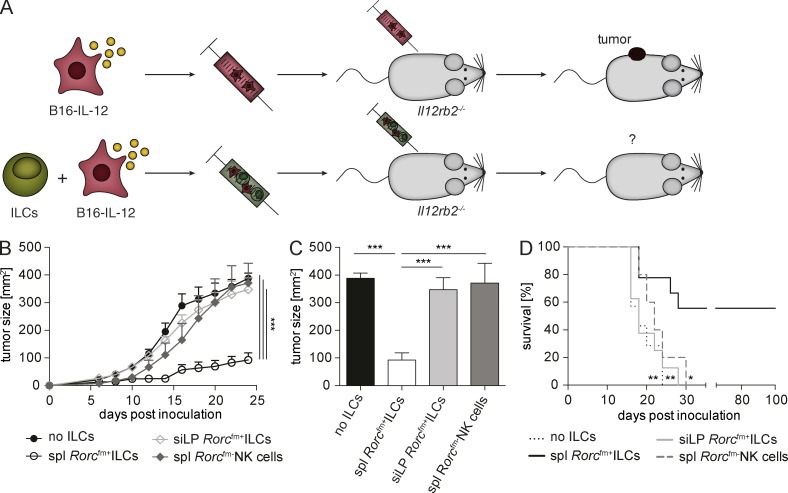

To evaluate functional differences of Rorcfm+ ILCs originating from either a lymphoid or nonlymphoid environment, we investigated the capacity of these cells to modulate melanoma growth in the context of the tumor-suppressive cytokine IL-12. We engineered B16.F10 melanoma cells to constitutively express a recombinant IL-12:Fc fusion protein or an Fc-tag alone (hereafter, called B16-IL-12 vs. B16-ctrl; Eisenring et al., 2010; vom Berg et al., 2013) and cotransplanted these cells with Rorcfm+ ILCs s.c. into Il12rb2−/− mice. In this particular setting, Rorcfm+ ILCs comprise the only IL-12–responsive cell type in the tumor (Fig. 3 A). Small numbers of lymphoid tissue-derived Rorcfm+ ILCs were able to suppress tumor growth over an extended period (Fig. 3 B). In contrast, Rorcfm+ ILCs originating from the siLP failed to reject tumors, suggesting that their conditioning in the gut microenvironment stunted their tumor-suppressive capacity. Conventional NK cells also failed to reject B16–IL-12 melanomas, despite their phenotypic similarity to splenic Rorcfm+ ILCs (Fig. 3, B and C). Tumor suppression by splenic ILC3s resulted in extended survival (Fig. 3 D). Of note, LN-derived Rorcfm+ ILCs possessed tumor-suppressive capacity, whereas hepatic Rorcfm+ ILCs, similar to siLP Rorcfm+ ILCs, did not induce tumor suppression (Fig. S2, A and B). To assess whether our observations resulted from the lymphopenic environment in Rag−/− mice, we confirmed our findings using Rorcfm+ ILCs from WT mice: splenic Rorcfm+ ILCs retain tumor-suppressive properties, whereas neither siLP Rorcfm+ ILCs nor phenotypically similar Rorcfm− NK cells inhibit tumor growth (not depicted). Our data suggest both phenotypic and functional specialization of tissue-resident Rorcfm+ ILCs. Thus, the function of ILCs is shaped not only during their lineage commitment but also by the tissue microenvironment.

Figure 3.

Splenic Rorcfm+ ILCs suppress tumor growth in an IL-12–dependent manner. (A) Schematic representation of the experimental setup. B16–IL-12 tumor cells were s.c. injected into Il12rb2−/− mice with or without Rorcfm+ ILCs, isolated from various organs of Rorcfm-Rag1−/− mice using flow cytometric cell sorting. (B) Tumor growth of B16–IL-12 tumor cells coinjected with splenic (spl) Rorcfm+ ILCs (open circles), siLP Rorcfm+ ILCs (open squares), or splenic (spl) Rorcfm-NK cells (closed squares), respectively, or in the absence of ILCs (closed circles) over time. For comparison of the tumor growth curve two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test was used. ***, P < 0.001. (C) Quantification of tumor growth at d 24 after tumor inoculation. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test was performed. ***, P < 0.001. (D) Kaplan-Meier survival curve of mice coinjected with B16–IL-12 and splenic (spl) Rorcfm+ ILCs (bold continuous line), siLP Rorcfm+ ILCs (gray continuous line), splenic (spl) Rorcfm- NK cells (gray dashed line), or in the absence of ILCs (bold dotted line). (B–D). Graphs represent pooled data from three independent experiments, n ≥ 4 each (means ± SEM). For comparison of survival curves, a Lox-rank (Mantel-Cox) test was used. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

Tumor-suppressive Rorcfm+ ILCs down-regulate RORγt and increase T-bet expression

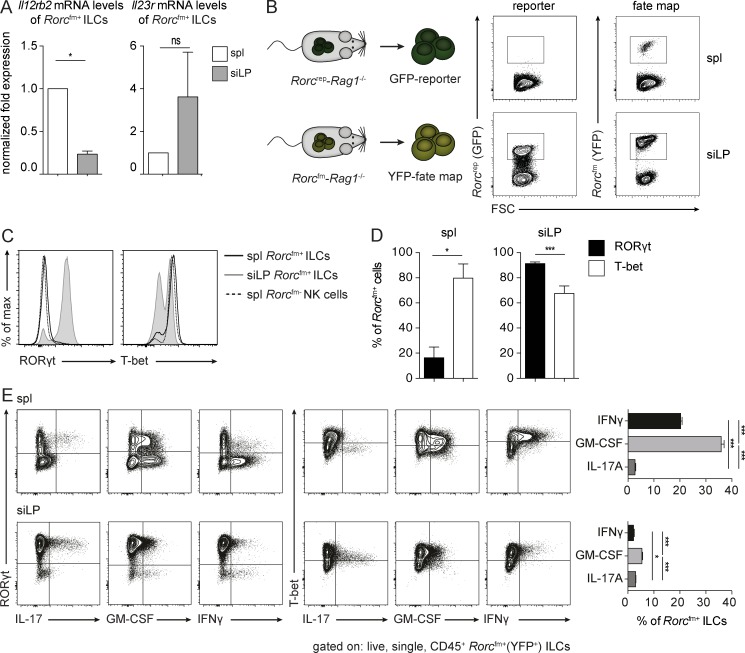

Previously, IL-23 receptor expression was reported on ILC3s, whereas IL-12 receptor expression was restricted to ILC1s (Vonarbourg et al., 2010). To determine whether the tissue influences, which render the tumor-suppressive function of Rorcfm+ ILCs also alter their responsiveness toward IL-12/IL-23, we quantified the expression of IL-12/IL-23 receptors on isolated Rorcfm+ ILCs from spleen and siLP. Splenic Rorcfm+ ILCs expressed higher levels of the IL-12–specific receptor subunit Il12rβ2 compared with siLP Rorcfm+ ILCs, which expressed the IL23r (Fig. 4 A). Thus, the heightened sensitivity of splenic Rorcfm+ ILCs to IL-12 may explain their tumor-suppressive capacity.

Figure 4.

Splenic Rorcfm+ ILCs acquire an “ex-ILC3” phenotype. (A) Normalized expression of Il12rb2 and Il23r mRNA levels of flow cytometric–sorted splenic and siLP Rorcfm+ ILCs. Graphs represent pooled data from three independent experiments, n = 3 each (means ± SEM). Two-tailed unpaired t test was performed. *, P < 0.05. (B, left) Schematic representation of Rorcfm-Rag1−/− and reporter RorcGFP-Rag1−/− mice. (Right) Flow cytometric analysis of splenic and siLP ILCs in reporter (left; GFP) and fm (right; YFP) mice. Representative graphs of three independent experiments, n ≥ 4 each. (C) Histogram overlay of transcription factors expressed by splenic (spl) Rorcfm+ ILCs (bold continuous line), siLP Rorcfm+ ILCs (gray continuous line), or splenic (spl) Rorcfm- NK cells (dotted line). Representative histograms of three independent experiments, n = 4 each. (D) Quantification of RORγt- or T-bet–expressing splenic (spl) or siLP Rorcfm+ ILCs. Graphs represent pooled data from three independent experiments, n = 4 each (means ± SEM). Two-tailed, unpaired t test was performed. *, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001. (E, left) Flow cytometric analysis of cytokine expression by splenic (spl) or siLP Rorcfm+ ILCs. Representative histograms of three independent experiments, n = 4 each. (Right) Quantification of cytokine expressing splenic (spl) or siLP Rorcfm+ ILCs. Graphs represent pooled data from three independent experiments, n ≥ 3 each (means ± SEM). One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test was performed. *, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001.

A previous study suggested an inverse correlation between IL-12 receptor and RORγt expression in Rorcfm+ ILCs (Vonarbourg et al., 2010). To evaluate whether the tissue microenvironment directly influences RORγt expression, we took advantage of the Rorcfm (Rorcfm+ ILCs) and Rorc-reporter (Rorcrep+ ILCs) mice and compared their ILC3 compartment of spleen and siLP. Although the small intestine was rich in both Rorcfm+ and Rorcrep+ ILCs, most splenic Rorcfm+ ILCs lost RORγt expression (Fig. 4 B). Accordingly, most splenic ILC3s expressed T-bet uniformly and the cytokines IFN-γ, GM-CSF (Fig. 4, C–E), granzyme, and perforin (not depicted), thus corroborating a shift of tumor-suppressive Rorcfm+ ILCs toward type 1 immunity.

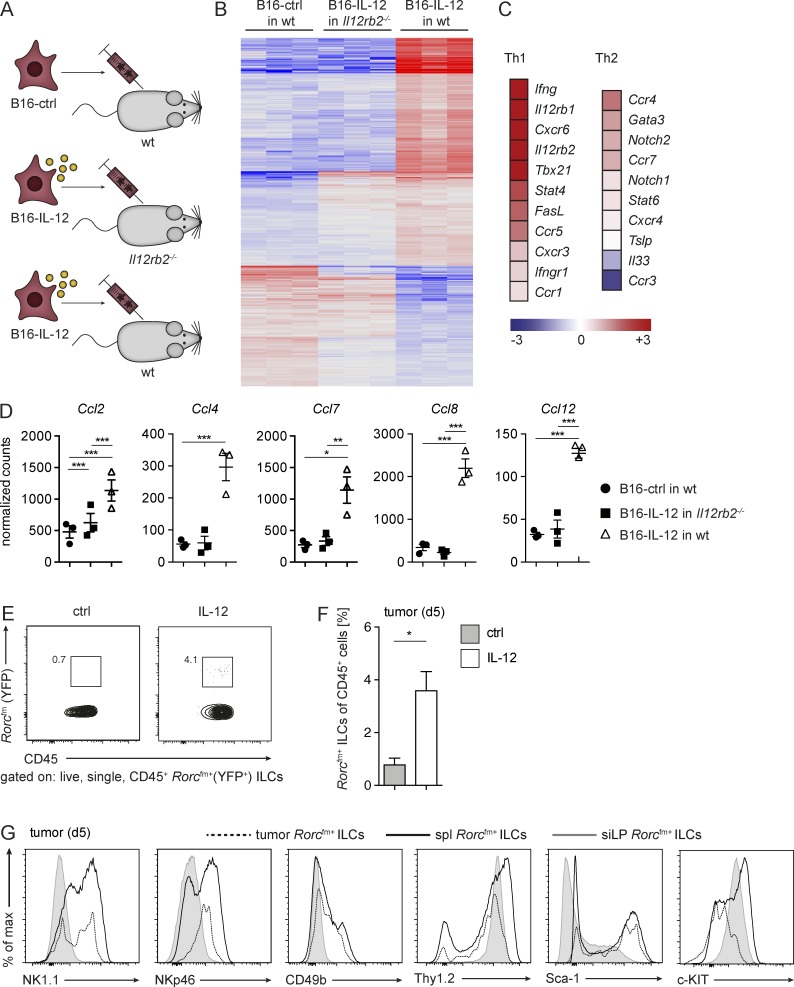

IL-12 activates the tumor microenvironment and the recruitment of tumor-invading ILCs

To assess the effect of IL-12 on the tumor microenvironment and how that influences ILC-driven immune responses, we injected B16-control or B16–IL-12 s.c. into C57BL/6 or IL-12-unresponsive Il12rb2−/− mice (Fig. 5 A). On day 5 after transplantation, the complete tumor tissue was resected, and total mRNA was analyzed by next-generation sequencing (NGS). Fig. 5 B depicts the signature of the tumor microenvironment in the presence or absence of IL-12. Increased expression of both IL-12 subunits, STAT4 and IFN-γ, confirmed the IL-12 responsiveness of the tumor microenvironment at early times (not depicted). IL-12 expression induced a signature in the tumor microenvironment reminiscent of type 1 immune responses, as shown by strong up-regulation of IFN-γ, the FAS ligand, and the type 1–associated chemokine receptors C-X-C chemokine receptor (CXCR)6, CCR5, CXCR3, and CCR1 (Fig. 5 C). Additionally, several chemokines, such as C-C chemokine ligand (CCL)2, CCL4, CCL7, CCL8, and CCL12, known to attract/recruit lymphocytes, monocytes, and a variety of other immune cells were up-regulated in the presence of IL-12 (Fig. 5 D). Taken together, the pro-inflammatory responses induced by IL-12 may support the invasion and activation of ILCs into the tumor tissue.

Figure 5.

IL-12 alters the tumor microenvironment and increases the frequency of tumor-infiltrating Rorcfm+ ILCs. (A) Schematic representation of the three experimental groups used for NGS: B16-control (ctrl) tumor cells were injected into WT mice and B16-IL-12 tumor cells into WT or Il12rb2−/− mice, respectively. NGS was performed on RNA obtained from tumors 5 d after tumor inoculation. (B) Heat map of differentially expressed genes in the tumor tissue. (C) Heat map of expression levels of Th1- and Th2-associated genes of B16–IL-12 in WT mice (means of three tumors depicted). (D) Normalized counts of the chemokines Ccl2, Ccl4, Ccl7, Ccl8, and Ccl12. Each data point represents one tumor (means ± SEM). One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test was performed. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. (E) Flow cytometric analysis of live, single CD45+ Rorcfm+ ILCs in the tumor tissue (growing in Rorcfm-Rag1−/− mice) 5 d after tumor inoculation. (F) Frequencies of tumor-infiltrating Rorcfm+ ILCs within the CD45 compartment 5 d after tumor inoculation in the presence or absence of intratumorally administered IL-12. Representative graph of one of three independent experiments, n ≥ 3 each (means ± SEM). Two-tailed, unpaired t test was used. *, P < 0.05. (G) Histogram overlay of Rorcfm+ ILCs of tumor (dotted line), spleen (spl, bold continuous line), and siLP (gray continuous line) 5 d after tumor inoculation into Rorcfm-Rag1−/− mice. Representative histograms from three independent experiments, n = 5 each.

We next investigated whether the effect of IL-12 on the tumor microenvironment would indeed favor the recruitment of tumor-suppressive Rorcfm+ ILCs. We found significantly elevated frequencies of Rorcfm+ ILCs in IL-12–treated tumors compared with controls (Fig. 5, E and F). Similar to lymphoid tissue–resident Rorcfm+ ILCs, tumor-infiltrating Rorcfm+ ILCs mostly expressed Thy1.2, but also the markers NKp46, NK1.1, and CD49b, classifying them as phenotypically similar to NK cells (Fig. 5 G). Our data show that the presence of IL-12 supports the recruitment of ILCs, which resemble tumor-suppressive, lymphoid tissue–resident Rorcfm+ ILCs.

ILC1s resemble tumor-suppressive Rorcfm+ ILCs but fail to suppress tumor growth

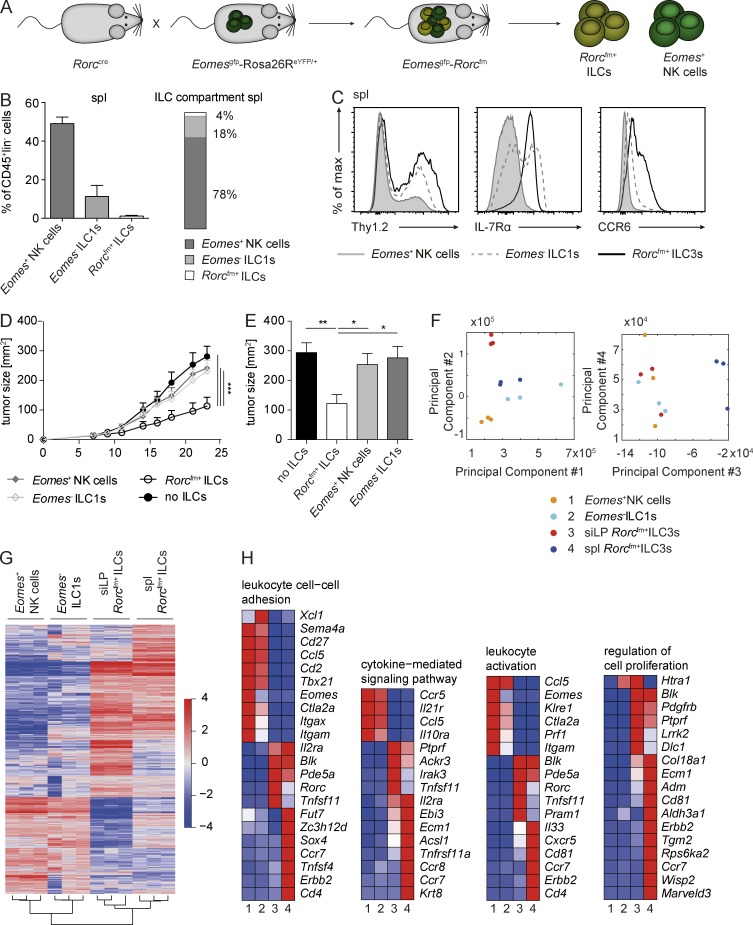

Previous studies demonstrated the plastic nature of ILCs, in particular the conversion of ILC3 toward type 1 ILC polarization (Vonarbourg et al., 2010; Klose et al., 2013, 2014; Bernink et al., 2015). Because we found that tumor-suppressive Rorcfm+ ILCs acquire a phenotype similar to type I ILCs (losing RORγt and expressing NCRs), we evaluated the capacity of the phenotypically similar Eomes− ILC1s to suppress tumor growth in an IL-12–dependent manner.

We made use of a recently introduced mouse model, combining the fm of Rorc with the reporter for Eomes (EomesGFP+; Klose et al., 2014), allowing for the identification of conventional NK cells (Rorcfm-Eomes+), ILC1s (Rorcfm−Eomes−) and ILC3s (Rorcfm+) by their transcription profile and ontogeny tracing (Fig. 6 A and Fig. S3, A and B). When characterizing the splenic ILC compartment, Eomes+ NK cells clearly dominate in numbers, comprising ∼50% of all CD45+lin−cells and almost 80% of the splenic ILC1 and ILC3 compartment (Fig. 6 B), in comparison to Eomes− ILC1s or Rorcfm+ ILCs, which represent 18% or 4%, respectively, of the ILC compartment (Fig. 6 B). As previously observed (Klose et al., 2014), Eomes− ILC1s showed a heterogeneous expression pattern of Thy1.2 and IL-7Rα (Fig. 6 C), expressed T-bet and were negative for RORγt and Eomes, as confirmed by intracellular staining (not depicted). Thus, Eomes− ILC1s clearly show a type 1 phenotype resembling that of most lymphoid tissue-resident Rorcfm+ ILCs, raising the question as to whether they also have tumor-suppressive properties.

Figure 6.

ILC1s phenotypically resemble tumor-suppressive Rorcfm+ ILCs but fail to inhibit tumor growth. (A) Schematic representation of the Rorccre mice crossed to the EomesGFP-Rosa26ReYFP/+ mice labeling all cells expressing RORγt with enhance YFP and all cells expressing Eomes with GFP. (B, left) Quantification of the different ILC subsets within the CD45+ compartment of the spleen. (Right) Distribution of NK cells (dark bar), ILC1s (light bar), and ILC3s (white bar) within the ILC compartment of the spleen. Graphs represent pooled data from two independent experiments, n ≥ 5 each (means ± SEM). (C) Histogram overlay of different ILC subsets in the spleen. Representative histograms of two independent experiments, n ≥ 5 each. (D) Il12rb2−/− mice were s.c. challenged with B16–IL-12 coinjected with splenic (spl) Rorcfm+ ILCs (open circles), Eomes− ILC1s (open squares), Eomes+ NK cells (closed squares), or in the absence of ILCs (closed circles), and tumor growth was measured over time. Graphs represent pooled data from two independent experiments, n ≥ 5 each (means ± SEM). For comparison of the tumor growth curve, two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test was used. ***, P < 0.001. (E) Quantification of tumor burden 21 d after tumor inoculation. Graphs represent pooled data from two independent experiments, n ≥ 5 each (means ± SEM). One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test was performed. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01. (F) PCA of different ILC subsets, including splenic NK cells, ILC1s, and Rorcfm+ ILC3s as well as siLP Rorcfm+ ILC3s. (G) Heat map of differentially expressed genes of splenic NK cells, ILC1s and (Rorcfm+) ILC3s as well as siLP (Rorcfm+) ILC3s. (H) Heat maps of differentially expressed genes clustered to the indicated category. Heat maps show representative data of one sample per group.

We challenged Il12rb2−/− mice with B16–IL-12 tumor cells infused with one of the respective splenic ILC subsets (for schematic representation of the experimental setup, see Fig. 3 A). Despite the phenotypic similarities and the same tissue origin as Rorcfm+ ILCs, Eomes− ILC1s failed to suppress tumor growth (Fig. 6, D and E), pointing out an essential role of the ontogeny for defining their function. Taken together, the type 1 phenotype in lymphoid tissues applies to Eomes− ILC1s, conventional Eomes+ NK cells and Rorcfm+ ILCs, of which only the latter ones are tumor-suppressive in response to the proinflammatory cytokine IL-12.

To further explore the differences between tumor-suppressive and nonsuppressive ILCs, we performed transcriptome analysis of splenic Rorcfm+ ILCs, Eomes− ILC1s and Eomes+ NK cells, as well as siLP Rorcfm+ ILCs. Compellingly, principle component analysis (PCA) shows similarity between splenic Rorcfm+ ILCs and Eomes− ILC1s. Component 3 separates splenic Rorcfm+ ILC3s from the other ILC subsets, indicating that differentially expressed genes in this population may be involved in their functional differences in tumor suppression (Fig. 6 F). Basic hierarchical clustering of the four populations showed that splenic and siLP Rorcfm+ ILCs were more closely related to each other compared with the type 1 ILCs, despite them being isolated from two distinct organs, reflecting the strong guidance cues of their common cellular derivation (Fig. 6 G and Fig. S4, A–D). Further in-depth analysis revealed that wide ranges of cellular mechanisms are significantly altered in tumor-suppressive splenic Rorcfm+ ILCs compared with all the other analyzed ILC subsets. Differences in leukocyte cell–cell adhesion and leukocyte-activation pathways, including the greater expression of genes such as Ccr7, Cxcr5, Cd4, Cd81, and Erbb2 hints toward a distinct migration and homing mechanisms of splenic Rorcfm+ ILCs in response to malignancies. Similarly, genes involved in the cytokine-mediated signaling pathways and cellular proliferation (Krt8, Tnfrsf11a [encoding RANK, i.e., TRANCE], and Adm, Cd81, Erbb2, Wisp2, or Marveld3) are altered, pointing toward distinct functionality of splenic Rorcfm+ ILCs. Similar to previously published studies, genes involved in the pathway of LN development were differentially expressed in splenic Rorcfm+ ILCs, confirming the validity of the approach (Fig. S4 E). Taken together, tumor-suppressive splenic Rorcfm+ ILCs possess transcriptional differences compared with nonsuppressive siLP Rorcfm+ ILCs or other splenic type 1 ILCs, which may explain their differential functionality. Thus, the classification of ILC subsets based on their superficial phenotypic appearance, that is, surface markers alone, seems arbitrary in light of their function and signature being guided primarily by their ontogeny (i.e., transcriptional regulation) and the tissue they reside in.

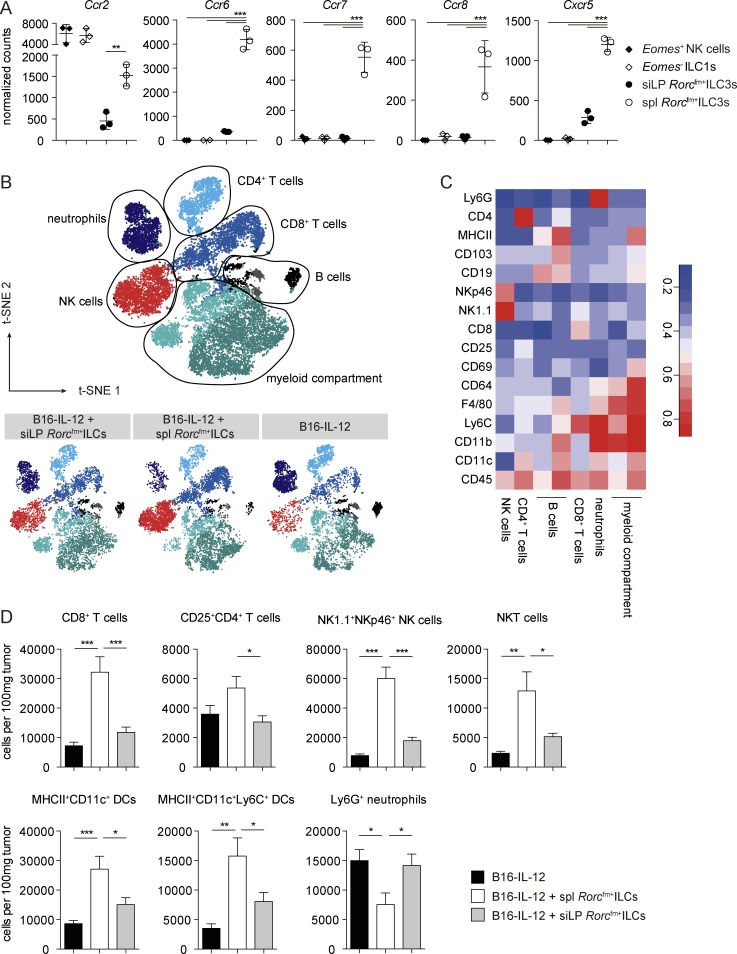

Splenic Rorcfm+ ILCs change the tumor microenvironment, favoring leukocyte invasion

The mechanism by which IL-12–activated Rorcfm+ ILCs suppress tumor growth remains unknown. The fact that Rorcfm+ ILCs only express low amounts of cytotoxic molecules, compared with NK cells or ILC1s (Fig. S5 A), and suppression of B16–IL-12 tumors is perforin independent (Eisenring et al., 2010) led us to hypothesize that Rorcfm+ ILCs may shape the tumor microenvironment in a way that it is more conducive for other immune effector cells to invade. Similar to LTi’s, we found high levels of the chemokine receptors CCR2, CCR6, CCR7, CCR8, and CXCR5 in splenic Rorcfm+ ILCs, compared with siLP Rorcfm+ ILCs (Fig. 7 A), suggesting an involvement of ILCs in the formation of lymphoid structures (Shields et al., 2010). Along that line, splenic Rorcfm+ ILCs showed an activated phenotype, indicated by greater expression levels of MHC II, CD74, and CD28 compared with siLP Rorcfm+ ILCs (Fig. S5 B). To further analyze the tumor microenvironment and the pattern of tumor-infiltrating immune cells, we coinjected B16–IL-12 tumor cells with splenic and siLP Rorcfm+ ILCs 10 d after tumor inoculation by high-dimensional, 22-parameter flow cytometry. Unbiased, algorithm-driven analysis revealed differences in the tumor-infiltrating immune compartments of splenic Rorcfm+ ILCs compared with the other experimental groups (Fig. 7, B and C), characterized by increased invasion by CD8+ T cells, NK cells, and NKT cells, as well as by activated myeloid cells (Fig. 7 D). Interestingly, all these cell types have previously been shown to be involved in tumor suppression driven by IL-12 (Kerkar et al., 2011; Tugues et al., 2015) and might cooperate to provide an efficient IL-12–driven antitumor response through Rorcfm+ ILCs. Taken together, our results suggest a preferential recruitment of lymphoid-tissue–derived Rorcfm+ ILCs to the tumor site, which, in turn, may render the tumor microenvironment more conducive to the invasion of further immune effectors.

Figure 7.

Splenic Rorcfm+ ILCs render the tumor microenvironment more conducive to immune cell invasion. (A) Chemokine receptor expression by the different splenic and siLP Rorcfm+ ILCs; data from NGS (means ± SD; Fig. 6). One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test was performed. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. (B) Dimensionality reduction using t-SNE. Data from tumor-infiltrating immune cells of B16–IL-12 tumors (day 10) coinjected with siLP, splenic (spl) Rorcfm+ ILCs, or without ILCs (gated on live, single CD45+) were transformed and plotted in two t-SNE dimensions using R software. Clustering was performed using the flowSOM algorithm (k = 8). Depicted are an annotated, combined data set (top) and the data sets of tumor-infiltrating immune cells of tumors coinjected with siLP Rorcfm+ ILCs (left), splenic Rorcfm+ ILCs (middle), and without ILCs (right). (C) Lymphocyte and myeloid-associated markers plotted in a heat map across flowSOM clusters from B. (D) Quantification of the altered cell populations identified in B using manual gating. Graphs represent pooled data from two independent experiments, n ≥ 5 each (means ± SEM). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

Discussion

Since the discovery of LTi’s two decades ago, ILCs have been studied intensively and shown to be involved in tissue homeostasis and host defense (Artis and Spits, 2015; Eberl et al., 2015; Sonnenberg and Artis, 2015). It is becoming increasingly clear that ILCs affect tumor immune surveillance (Eisenring et al., 2010; Ikutani et al., 2012; Kirchberger et al., 2013; Chan et al., 2014; Jovanovic et al., 2014; Li et al., 2014; Crome et al., 2017; Irshad et al., 2017). The function of ILCs varies depending on the tumor model and tissue localization, raising questions as to how the tissue microenvironment influences these cells and especially their function. Here, we show that ILC3s adapt to their local tissue microenvironment and demonstrate vastly different phenotypic characteristics (i.e., marker expression). Their functional properties (i.e., tumor suppression), however, are guided by their ontogeny (i.e., early transcriptional imprinting) as well as by adaptation to their tissue microenvironment, uncoupled from their phenotype.

Although the development of ILC3s has been elucidated in various studies (Satoh-Takayama et al., 2010; Cherrier et al., 2012; Constantinides et al., 2014; Klose et al., 2014; Montaldo et al., 2014), the effect of the tissue microenvironment on their phenotype and function remains largely elusive. Notably, our computer-aided dimensionality reduction and clustering showed a clearly demarcated specification for ILC3s in lymphoid and nonlymphoid organs. Parabiosis experiments demonstrated that ILCs are tissue-resident cells (Gasteiger et al., 2015); only a few of them have been found in the circulation, suggesting distinct phenotypes and functions for these cells in different tissues. Moreover, the expression of homing markers, such as α4β7, CXCR6, CCR9, and CCR7 (Hoyler et al., 2012; Chea et al., 2015; Kim et al., 2015; Mackley et al., 2015), in ILCs and ILC precursors indicates a differential recruitment into tissues or lesions. We found ILC3s to distribute among various organs in the steady state and to phenotypically adapt to their new tissue environment, regardless of their origin. Hence, the phenotypic properties of ILC3s are not invariably imprinted during early development but are acquired upon homing to new localizations. In line with our findings, two previous studies demonstrated that a considerable part of intestinal Rorcfm+ ILCs lose RORγt expression when homing to colon lamina propria or spleen (Vonarbourg et al., 2010) and that the transcription factor was reexpressed when “inflammatory” ILC1s reconverted to “homeostatic” IL-22–producing ILC3s in the small intestine after adoptively transferring into Rag2−/−IL2Rg−/− mice (Bernink et al., 2015). Taken together, these findings suggest that the tissue microenvironment in the steady state provides strong guidance cues for the phenotypic adaptation of ILC3s to an individual tissue. Although this hints toward the high plasticity of ILCs, single cell-tracing experiments would be necessary to fully exclude heterogeneity of the transferred ILC population, as well as a differential maturation status or the presence of potential precursor cells that might undergo tissue-specific maturation or differentiation.

How the splenic and siLP microenvironments drive Rorcfm+ cells to predominantly ILC1/NK cells or ILC3 phenotypes remains unclear. This dichotomy might be explained by the differential functions between both organs—the lymphoid organs representing a “sterile” environment and a site of antigen presentation, whereas the intestine is a barrier tissue highly colonized by commensal bacteria. Cytokines, such as IL-23 and IL-1β or IL-12, for example, have been shown to induce the ILC3 and the ILC1 phenotypes, respectively (Vonarbourg et al., 2010; Bernink et al., 2015). Accordingly, we and others found that splenic Rorcfm+ ILCs expressed higher levels of the IL-12–specific receptor subunit Il12rβ2 compared with siLP Rorcfm+ ILCs, whereas the latter population expresses the IL-23 receptor and higher amounts of IL-1β receptor. Moreover, mice deficient for IL12a were found to have increased numbers of RORγt+NCR− ILC3s (Vonarbourg et al., 2010).

In addition to cytokines, commensal bacteria, metabolic products, and the dominating cell types populating the different tissues may regulate the phenotypic properties of ILC3s. For example, the gut metabolite retinoic acid was found to induce the conversion of CD127+ ILC1 to IL-22–producing ILC3 (Bernink et al., 2015). CX3CR1+ mononuclear phagocytes/intestinal DCs that develop in the intestine after commensal colonization drive the production of IL-22 by RORγt+ ILCs (Niess and Adler, 2010; Manta et al., 2013; Satoh-Takayama et al., 2014). Further, commensal bacteria might be able to stimulate ILCs directly by engaging NCRs, such as NKp46 or NKp44, in human or mouse, respectively (Esin et al., 2008; Chaushu et al., 2012; Glatzer et al., 2013).

Rorcfm+ ILCs, more precisely LTi’s, are implicated in the organogenesis of lymphoid structures, thus having a constructive or organizational character. In addition, they may interfere with the establishment of the tumor tissue itself or tumor-associated lymphoid structures. High lymphocyte infiltration (recruited by chemokines such as CCL21) and a tumor landscape resembling lymphoid structures have been suggested to be beneficial for tumor suppression (Messina et al., 2012). Early after B16 inoculation, IL-12 led to the up-regulation of chemokines (such as CCL2, CCL3, CCL4, CCL5, CXCR9, and CXCR10; unpublished data) that are also associated with LN-like structures in human melanoma, pointing toward successful tumor suppression. Of those, CCL2 and CCL5, expressed in the tumor microenvironment, were previously shown to correlate with lymphocyte infiltration and tumor destruction (Balkwill, 2004). Whether IL-12–responsive ILC3s also induce lymphoid-like structures in our tumor setting will require further investigation, but the presence of NCR+ ILC3s has been correlated with increased lymphoid structures and beneficial clinical outcome in patients with human lung cancers (Carrega et al., 2015), suggesting that Rorcfm+ ILCs have a role at the tumor–immune interphase in preclinical models and patients alike.

We show that the tumor-suppressive properties of Rorcfm+ ILCs are shaped not only during their lineage commitment but also by the tissue microenvironment. As such, lymphoid tissue–derived Rorcfm+ ILCs are sensitive to IL-12 and suppress tumor growth, whereas intestinal Rorcfm+ ILCs fail to do so. In contrast, ILCs that mainly reside in mucosal barrier tissues engage the IL-23/IL-17 axis to protect against invading pathogens and have been reported to drive gut tumorigenesis (Chan et al., 2014). Collectively, these studies demonstrate how powerful the tissue microenvironment effects on Rorcfm+ ILCs are and how it shapes them along the IL-12/IL-23 axis toward a pro- or antitumorigenic response (Eisenring et al., 2010; Chan et al., 2014).

Even though the cellular tissue origin of tumor-suppressive ILCs remains unknown, our data suggest that they might arise from the lymphatic system, where they promptly react to and/or initiate a type 1 immune response. A recent study showed active migration of ILCs in response to CCR7 and CCR9 (Mackley et al., 2015), indicating that ILCs actively migrate to certain tissues upon triggering of homing receptors. In our setting of IL-12–mediated tumor suppression, Rorcfm+ ILCs are recruited to the tumor tissue, in all likelihood, responding to specific chemokines present in the activated tumor tissue. Once Rorcfm+ ILCs are present in the tumor, they render the tumor microenvironment more conducive to the invasion of immune effectors, potentially activating the adaptive immune system and/or, as previously hypothesized, by potentiating the crosstalk between innate and adaptive antitumor immune responses.

The effect of IL-12–induced plasticity and the tissue microenvironment on the phenotype and function of ILCs seems undisputable (Cella et al., 2010; Vonarbourg et al., 2010; Klose et al., 2013, 2014; Huang et al., 2014; Bernink et al., 2015; Bal et al., 2016; Lim et al., 2016; Ohne et al., 2016) and justifies further analysis of the mechanism by which ILCs can alter the tumor microenvironment. Moreover, we show a convergence of ontogeny, phenotype, and function, suggesting that classification of ILC subsets based on their phenotypic properties seems unreliable because ILCs are guided primarily by their ontogeny (i.e., transcriptional regulation) and the tissue they reside in.

Materials and methods

Study design

Our aim was to study the effect of the tissue microenvironment and ontogeny on the phenotype and function of ILC3s by investigating their tumor-suppressive capacity. We used several genetically modified mouse models for tumor experiments and to distinguish various ILC3 and ILC1 subsets. Age- and sex-matched mice were randomly divided into experimental groups. Experiments to characterize the phenotype and determine the function of ILC3s were performed at least two times with three to eight mice per group. All animal care and handling were performed according to the guidelines by the Swiss cantonal veterinary office.

Mice

Mice were housed in individually ventilated cages under specific pathogen-free conditions. Conventional C57BL/6 mice (WT) were purchased from Janvier Labs. Il12rb2−/−, Rag1−/−, Rag2−/−Il2rg−/−, and RorcGFP/+ (Rorc−/−) mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. Il15ra−/− mice were provided by S. Bulfone-Paus (Forschungszentrum Borstel, Borstel, Germany); Rorc-eYFP and Rorccre mice by A. Diefenbach (University of Mainz, Mainz, Germany); and EomesGFP/+ mice by S.J. Arnold (University of Freiburg, Freiburg, Germany; Arnold et al., 2009). All experimental procedures were performed according to the animal licenses approved by the Swiss cantonal veterinary office (licenses 145/2012 and 142/2015).

Tumor cell lines

B16.F10 melanoma cells were purchased from ATCC. The generation of tumor cell lines stably producing IL-12:Fc or Fc has been previously described (Eisenring et al., 2010). B16 tumor cells were cultured in DMEM (PAN-Biotech) supplemented with 10% FBS (Biochrom), 1% glutamine (Gibco), 1% sodium-pyruvate (Gibco), and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Invitrogen; hereafter, referred to as complete medium). Transfected cell lines were selected with hygromycin B (Invitrogen) and maintained at 37°C, 5% CO2.

Tumor transplantation and monitoring

A total of 2 × 105 tumor cells were s.c. injected into the lateral abdomen of the mouse. Tumor growth was measured three times a week. Animals that showed clinical symptoms, such as apathy, severe hunchback posture, weight loss of >20% of peak weight, and/or tumor ulceration were euthanized.

IL-12 treatment

IL-12:Fc (IL-12) was administered systemically i.p. or local intratumoral, at a dose of 200 µg three times a week. Production and purification of mouse IL-12:Fc (IL-12) was performed as previously described (vom Berg et al., 2013).

Lymphocyte isolation

Mice were sacrificed by CO2 inhalation, perfused with 25 ml ice-cold PBS, and organs were harvested and processed as follows. Lymphoid organs were digested in 0.4 mg/ml collagenase IV (from Clostridium histolyticum; Sigma-Aldrich) in HBSS, including MgCl2 and CaCl2 (Gibco) supplemented with 10% FBS for 30 min at 37°C and agitated. The lung and the liver tissues were digested using 1 mg/ml collagenase IV. For liver samples, a Percoll gradient was performed (continuous gradient, 27%; GE Healthcare). The colon and small intestine were digested as described before (Burkhard et al., 2014). The skin and tumor tissue were isolated using 1 mg/ml collagenase IV and 0.2 mg/ml DNase I (Sigma-Aldrich) for 1 h at 37°C and agitating.

Flow cytometry and cell sorting

Single-cell suspensions were stained for 20–30 min at 4°C in PBS. Fluorochrome-conjungated antibodies specific against mouse c-KIT (2B8), CCR6 (29-2L17), CD103 (2E7), CD11c (N418, HL3), CD19 (6D5, 1D3), CD27 (LG.3A10), CD3 (145-2C44), CD4 (GK1.5, RM4-5), CD45 (30-F11), CD49b (DX5), CD5 (53–7.3), Eomes (Dan11mag), GM-CSF (MP1-22E9), IFN-γ (XMG1.2), IL-17 (TC11-18H10), IL-7Rα (A7R34, SB/199), NK1.1 (PK136), NKp46 (29A1.4), RORγt (Q31-378), Sca-1 (D7), T-bet (4B10), TCRβ (H57-597), and Thy1.2 (30-H12, OX-7) were purchased from BioLegend, BD, or eBioscience. In all staining, dead cells were excluded using Live/Dead fixable staining reagents (Invitrogen), and doublets were excluded by FSC-A versus FSC-H and SSC-A versus SSC-H gating. Samples were acquired using a FACSCanto II, LSR Fortessa II, or FACSymphony flow cytometer and FACSDiva software (BD). Cell sorting was performed on a FACSAria III (BD) using a 70-µm nozzle, with a purity of >95%. Data analysis was performed using FlowJo 10.0.8 software (Tree Star). For some graphs, data from several individual samples were concatenated in FlowJo.

In vitro stimulation and intracellular staining

For cytokine staining, cells were stimulated for 4 h at 37°C in complete RPMI with 0.05 µg/ml PMA, 0.5 µg/ml ionomycin, and 1 µl/ml brefeldin A (GolgiPlug; Invitrogen). Intracellular staining was performed using the Cytofix/Cytoperm kit (BD) or the Foxp3/transcription factor staining buffer set (eBioscience), according to manufacturer’s instructions with the respective antibodies at 4°C for 30–60 min or overnight.

Automated population identification in high-dimensional data analysis and t-SNE dimensionality reduction

After preprocessing of the flow cytometric data gating on live, single CD45+Rorcfm+(YFP+) ILCs, flow cytometry standard (.fcs) files of splenic and siLP Rorcfm+ ILCs were down-sampled to 4 × 104 events per sample and combined into one file. FlowSOM clustering algorithm was used to identify biologically meaningful clusters in an unbiased way using R software, and the created nodes were subjected to meta-clustering. The flowSOM algorithm clusters cells with similar phenotypic appearance into subpopulations or subsets, which are depicted in special proximity on the t-SNE plot (Levine et al., 2015; Van Gassen et al., 2015). To identify meaningful ILC subsets, based on knowledge of the literature, a k-value of 5 was chosen. Heat maps were drawn using the ggplot2 R package to display median expression levels for the indicated clusters. Dendrograms were calculated using hierarchical clustering. To visualize the high-dimensional data and clusters, two-dimensional t-SNE plots were created using R software and were overlayed with the clusters created by the FlowSOM algorithm.

RNA isolation and quantitative RT-PCR

RNA isolation was conducted using the RNeasy Mini Plus or Micro Plus Kits (QIAGEN). First-strand cDNA synthesis was performed using Superscript II reverse transcription (Invitrogen) and oligo (dT) priming (PeproTech), according to the manufacturers’ protocols.

Quantitative analysis was conducted using a SYBR Green master mix (Roche). The PCR reaction was performed with a C1000 Touch thermal cycler (Bio-Rad Laboratories). For analysis, cycle threshold values of the genes of interest were normalized to the values of the polymerase 2 (Pol2) gene (as housekeeping gene). Primers used were IL12rb2 (forward): 5′-TGTGGGGTGGAGATCTCAGT-3′; IL12rb2 (reverse): 5′-TCTCCTTCCTGGACACATGA-3′; IL-23r (forward): 5′-CCAAGTATATTGTGCATGTGAAGA-3′; IL-23r (reverse): 5′-AGCTTGAGGCAAGATATTGTTGT-3′; Pol2 (forward): 5′-CTGGTCCTTCGAATCCGCATC-3′; Pol2 (reverse): 5′-GCTCGATACCCTGCAGGGTCA-3′.

NGS

For NGS, tumor tissue was resected 5 d after tumor inoculation and was immediately transferred into RNAlater stabilization solution (Ambion). For total RNA isolation, the tumor tissue was homogenized using a tissue homogenizer (Omni International), and total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Micro Kit Plus (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. NGS was performed by the Functional Genomic Center Zurich (http://www.fgcz.ch) using the HiSeq 2500 v4 System (Illumina). Quality control included the fastqc and DESeq2 analysis. The GO pathway analysis of tumor tissues was performed using the MetaCore software (Thomson Reuters), and visualization was performed with the TM4 MultiExperiment Viewer (Saeed et al., 2003). Pathway analysis of differentially expressed genes in splenic Rorcfm+ ILCs versus splenic Eomes− ILC1s, Eomes+ NK cells and siLP Rorcfm+ ILCs (based on Fig. S3) using David Bioinformatics Resources to extract GO terms “BP” (biological process) and “ReViGo” for visualization of the false discovery rate: Benjamini-Hochberg ≤ 0.01. PCA was performed using Matlab 2014b (MathWorks).

Statistical analysis

To analyze data statistically, GraphPad Prism 6.0 software (GraphPad Software) was used. A two-tailed unpaired t test was performed to determine statistical significance between two groups. Welsh's correction was applied in case of significantly different variances. For three or more groups, one-way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparisons test was performed. For comparison of the tumor growth curve two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test was used; p-values <0.05 were considered significantly different (exact p-values indicated in figure legends). Data are displayed as means ± SEM, unless otherwise stated.

Online supplemental material

Fig. S1 shows that Rorcfm+ ILCs from various organs possess different expression patterns. Fig. S2 shows that lymphoid Rorcfm+ ILCs suppress tumor growth, whereas nonlymphoid Rorcfm+ ILCs fail to do so. Fig. S3 shows a schematic representation of Rorc fate map crossed to Eomes reporter mice, which allows identification of type 1 and type 3 ILC subsets (gating strategy). Fig. S4 NGS reveals differentially expressed genes by splenic Rorcfm+ ILCs compared with other ILC subsets. Fig. S5 shows splenic Rorcfm+ ILCs only express low amounts of cytotoxic molecules and an activated phenotype.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Sabrina Nemetz, Jennifer Jaberg, Mirjam Lutz, and the Flow Cytometry Facility, University of Zurich for technical assistance.

This study was supported by grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF; grants 316030-150768, 310030-146130, and CRS II3-136203 to B. Becher), European Community FP7 (grant no. 602239 [ATECT] to B. Becher), and the University Priority Research Project (URPP) Translational Cancer Research (to B. Becher). K. Nussbaum holds a fellowship from Boehringer Ingelheim Fonds. S.J. Arnold is supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG AR732/1-1 and CRC 850, project A3). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author contributions: K. Nussbaum, S.H. Burkhard, and B. Becher designed the research; K. Nussbaum, S.H. Burkhard, I. Ohs, F. Mair, and S. Tugues performed and/or analyzed the data. C.S.N. Klose and A. Diefenbach provided mice and helped to interpret the data, S.J. Arnold provided mice, and K. Nussbaum, S. Tugues, and B. Becher wrote the manuscript.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used:

- CCL

- c-c chemokine ligand

- CCR

- c-c chemokine receptor

- CXCR

- C-X-C chemokine receptor

- ILC

- innate lymphoid cell

- LTi

- lymphoid tissue inducer cell

- NCR

- natural cytotoxicity receptor

- NGS

- next-generation sequencing

- PCA

- principal component analysis

- ROR

- retinoic acid-receptor-related orphan receptor

- siLP

- small intestinal lamina propria

- t-SNE

- t-stochastic neighbor embedding

References

- Arnold S.J., Sugnaseelan J., Groszer M., Srinivas S., and Robertson E.J.. 2009. Generation and analysis of a mouse line harboring GFP in the Eomes/Tbr2 locus. Genesis. 47:775–781. 10.1002/dvg.20562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artis D., and Spits H.. 2015. The biology of innate lymphoid cells. Nature. 517:293–301. 10.1038/nature14189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bal S.M., Bernink J.H., Nagasawa M., Groot J., Shikhagaie M.M., Golebski K., van Drunen C.M., Lutter R., Jonkers R.E., Hombrink P., et al. . 2016. IL-1β, IL-4 and IL-12 control the fate of group 2 innate lymphoid cells in human airway inflammation in the lungs. Nat. Immunol. 17:636–645. 10.1038/ni.3444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balkwill F. 2004. Cancer and the chemokine network. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 4:540–550. 10.1038/nrc1388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernink J.H., Krabbendam L., Germar K., de Jong E., Gronke K., Kofoed-Nielsen M., Munneke J.M., Hazenberg M.D., Villaudy J., Buskens C.J., et al. . 2015. Interleukin-12 and -23 control plasticity of CD127+ group 1 and group 3 innate lymphoid cells in the intestinal lamina propria. Immunity. 43:146–160. 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.06.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bie Q., Zhang P., Su Z., Zheng D., Ying X., Wu Y., Yang H., Chen D., Wang S., and Xu H.. 2014. Polarization of ILC2s in peripheral blood might contribute to immunosuppressive microenvironment in patients with gastric cancer. J. Immunol. Res. 2014:923135 10.1155/2014/923135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkhard S.H., Mair F., Nussbaum K., Hasler S., and Becher B.. 2014. T cell contamination in flow cytometry gating approaches for analysis of innate lymphoid cells. PLoS One. 9:e94196 10.1371/journal.pone.0094196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrega P., Loiacono F., Di Carlo E., Scaramuccia A., Mora M., Conte R., Benelli R., Spaggiari G.M., Cantoni C., Campana S., et al. . 2015. NCR+ ILC3 concentrate in human lung cancer and associate with intratumoral lymphoid structures. Nat. Commun. 6:8280 10.1038/ncomms9280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cella M., Otero K., and Colonna M.. 2010. Expansion of human NK-22 cells with IL-7, IL-2, and IL-1β reveals intrinsic functional plasticity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 107:10961–10966. 10.1073/pnas.1005641107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan I.H., Jain R., Tessmer M.S., Gorman D., Mangadu R., Sathe M., Vives F., Moon C., Penaflor E., Turner S., et al. . 2014. Interleukin-23 is sufficient to induce rapid de novo gut tumorigenesis, independent of carcinogens, through activation of innate lymphoid cells. Mucosal Immunol. 7:842–856. 10.1038/mi.2013.101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaushu S., Wilensky A., Gur C., Shapira L., Elboim M., Halftek G., Polak D., Achdout H., Bachrach G., and Mandelboim O.. 2012. Direct recognition of Fusobacterium nucleatum by the NK cell natural cytotoxicity receptor NKp46 aggravates periodontal disease. PLoS Pathog. 8:e1002601 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chea S., Possot C., Perchet T., Petit M., Cumano A., and Golub R.. 2015. CXCR6 expression is important for retention and circulation of ILC precursors. Mediators Inflamm. 2015:368427 10.1155/2015/368427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherrier M., Sawa S., and Eberl G.. 2012. Notch, Id2, and RORγt sequentially orchestrate the fetal development of lymphoid tissue inducer cells. J. Exp. Med. 209:729–740. 10.1084/jem.20111594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constantinides M.G., McDonald B.D., Verhoef P.A., and Bendelac A.. 2014. A committed precursor to innate lymphoid cells. Nature. 508:397–401. 10.1038/nature13047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crome S.Q., Nguyen L.T., Lopez-Verges S., Yang S.Y.C., Martin B., Yam J.Y., Johnson D.J., Nie J., Pniak M., Yen P.H., et al. . 2017. A distinct innate lymphoid cell population regulates tumor-associated T cells. Nat. Med. 23:368–375. 10.1038/nm.4278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberl G., and Littman D.R.. 2004. Thymic origin of intestinal αβ T cells revealed by fate mapping of RORγ+ cells. Science. 305:248–251. 10.1126/science.1096472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberl G., Colonna M., Di Santo J.P., and McKenzie A.N.J.. 2015. Innate lymphoid cells: A new paradigm in immunology. Science. 348:aaa6566 10.1126/science.aaa6566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenring M., vom Berg J., Kristiansen G., Saller E., and Becher B.. 2010. IL-12 initiates tumor rejection via lymphoid tissue-inducer cells bearing the natural cytotoxicity receptor NKp46. Nat. Immunol. 11:1030–1038. 10.1038/ni.1947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esin S., Batoni G., Counoupas C., Stringaro A., Brancatisano F.L., Colone M., Maisetta G., Florio W., Arancia G., and Campa M.. 2008. Direct binding of human NK cell natural cytotoxicity receptor NKp44 to the surfaces of mycobacteria and other bacteria. Infect. Immun. 76:1719–1727. 10.1128/IAI.00870-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finke D., Acha-Orbea H., Mattis A., Lipp M., and Kraehenbuhl J.. 2002. CD4—CD3− cells induce Peyer’s patch development: role of α4β1 integrin activation by CXCR5. Immunity. 17:363–373. 10.1016/S1074-7613(02)00395-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs A., and Colonna M.. 2013. Innate lymphoid cells in homeostasis, infection, chronic inflammation and tumors of the gastrointestinal tract. Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 29:581–587. 10.1097/MOG.0b013e328365d339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuyama S., Hiroi T., Yokota Y., Rennert P.D., Yanagita M., Kinoshita N., Terawaki S., Shikina T., Yamamoto M., Kurono Y., and Kiyono H.. 2002. Initiation of NALT organogenesis is independent of the IL-7R, LTβR, and NIK signaling pathways but requires the Id2 gene and CD3−CD4+CD45+ cells. Immunity. 17:31–40. 10.1016/S1074-7613(02)00339-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasteiger G., Fan X., Dikiy S., Lee S.Y., and Rudensky A.Y.. 2015. Tissue residency of innate lymphoid cells in lymphoid and non-lymphoid organs. Science. 350:981–985. 10.1126/science.aac9593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glatzer T., Killig M., Meisig J., Ommert I., Luetke-Eversloh M., Babic M., Paclik D., Blüthgen N., Seidl R., Seifarth C., et al. . 2013. RORγt+ innate lymphoid cells acquire a proinflammatory program upon engagement of the activating receptor NKp44. Immunity. 38:1223–1235. 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.05.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goto Y., Obata T., Kunisawa J., Sato S., Ivanov I.I., Lamichhane A., Takeyama N., Kamioka M., Sakamoto M., Matsuki T., et al. . 2014. Innate lymphoid cells regulate intestinal epithelial cell glycosylation. Science. 345:1254009 10.1126/science.1254009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hepworth M.R., Fung T.C., Masur S.H., Kelsen J.R., McConnell F.M., Dubrot J., Withers D.R., Hugues S., Farrar M.A., Reith W., et al. . 2015. Group 3 innate lymphoid cells mediate intestinal selection of commensal bacteria-specific CD4+ T cells. Science. 348:1031–1035. 10.1126/science.aaa4812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyler T., Klose C.S.N., Souabni A., Turqueti-Neves A., Pfeifer D., Rawlins E.L., Voehringer D., Busslinger M., and Diefenbach A.. 2012. The transcription factor GATA-3 controls cell fate and maintenance of type 2 innate lymphoid cells. Immunity. 37:634–648. 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.06.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y., Guo L., Qiu J., Chen X., Hu-Li J., Siebenlist U., Williamson P.R., Urban J.F., and Paul W.E.. 2014. IL-25-responsive, lineage-negative KLRG1hi cells are multipotential “inflammatory” type 2 innate lymphoid cells. Nat. Immunol. 16:161–169. 10.1038/ni.3078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikutani M., Yanagibashi T., Ogasawara M., Tsuneyama K., Yamamoto S., Hattori Y., Kouro T., Itakura A., Nagai Y., Takaki S., and Takatsu K.. 2012. Identification of innate IL-5-producing cells and their role in lung eosinophil regulation and antitumor immunity. J. Immunol. 188:703–713. 10.4049/jimmunol.1101270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irshad S., Flores-Borja F., Lawler K., Monypenny J., Evans R., Male V., Gordon P., Cheung A., Gazinska P., Noor F., et al. . 2017. RORγt+ innate lymphoid cells promote lymph node metastasis of breast cancers. Cancer Res. 77:1083–1096. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-0598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jovanovic I.P., Pejnovic N.N., Radosavljevic G.D., Pantic J.M., Milovanovic M.Z., Arsenijevic N.N., and Lukic M.L.. 2014. Interleukin-33/ST2 axis promotes breast cancer growth and metastases by facilitating intratumoral accumulation of immunosuppressive and innate lymphoid cells. Int. J. Cancer. 134:1669–1682. 10.1002/ijc.28481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerkar S.P., Goldszmid R.S., Muranski P., Chinnasamy D., Yu Z., Reger R.N., Leonardi A.J., Morgan R.A., Wang E., Marincola F.M., et al. . 2011. IL-12 triggers a programmatic change in dysfunctional myeloid-derived cells within mouse tumors. J. Clin. Invest. 121:4746–4757. 10.1172/JCI58814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M.H., Taparowsky E.J., and Kim C.H.. 2015. Retinoic acid differentially regulates the migration of innate lymphoid cell subsets to the gut. Immunity. 43:107–119. 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.06.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchberger S., Royston D.J., Boulard O., Thornton E., Franchini F., Szabady R.L., Harrison O., and Powrie F.. 2013. Innate lymphoid cells sustain colon cancer through production of interleukin-22 in a mouse model. J. Exp. Med. 210:917–931. 10.1084/jem.20122308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klose C.S., Kiss E.A., Schwierzeck V., Ebert K., Hoyler T., d’Hargues Y., Göppert N., Croxford A.L., Waisman A., Tanriver Y., and Diefenbach A.. 2013. A T-bet gradient controls the fate and function of CCR6−RORγt+ innate lymphoid cells. Nature. 494:261–265. 10.1038/nature11813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klose C.S.N., Flach M., Möhle L., Rogell L., Hoyler T., Ebert K., Fabiunke C., Pfeifer D., Sexl V., Fonseca-Pereira D., et al. . 2014. Differentiation of type 1 ILCs from a common progenitor to all helper-like innate lymphoid cell lineages. Cell. 157:340–356. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine J.H., Simonds E.F., Bendall S.C., Davis K.L., Amir A.D., Tadmor M.D., Litvin O., Fienberg H.G., Jager A., Zunder E.R., et al. . 2015. Data-driven phenotypic dissection of AML reveals progenitor-like cells that correlate with prognosis. Cell. 162:184–197. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Razumilava N., Gores G.J., Walters S., Mizuochi T., Mourya R., Bessho K., Wang Y.-H., Glaser S.S., Shivakumar P., and Bezerra J.A.. 2014. Biliary repair and carcinogenesis are mediated by IL-33-dependent cholangiocyte proliferation. J. Clin. Invest. 124:3241–3251. 10.1172/JCI73742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim A.I., Menegatti S., Bustamante J., Le Bourhis L., Allez M., Rogge L., Casanova J.-L., Yssel H., and Di Santo J.P.. 2016. IL-12 drives functional plasticity of human group 2 innate lymphoid cells. J. Exp. Med. 213:569–583. 10.1084/jem.20151750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackley E.C., Houston S., Marriott C.L., Halford E.E., Lucas B., Cerovic V., Filbey K.J., Maizels R.M., Hepworth M.R., Sonnenberg G.F., et al. . 2015. CCR7-dependent trafficking of RORγ+ ILCs creates a unique microenvironment within mucosal draining lymph nodes. Nat. Commun. 6:5862 10.1038/ncomms6862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manta C., Heupel E., Radulovic K., Rossini V., Garbi N., Riedel C.U., and Niess J.H.. 2013. CX3CR1+ macrophages support IL-22 production by innate lymphoid cells during infection with Citrobacter rodentium. Mucosal Immunol. 6:177–188. 10.1038/mi.2012.61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mchedlidze T., Waldner M., Zopf S., Walker J., Rankin A.L., Schuchmann M., Voehringer D., McKenzie A.N.J., Neurath M.F., Pflanz S., and Wirtz S.. 2013. Interleukin-33-dependent innate lymphoid cells mediate hepatic fibrosis. Immunity. 39:357–371. 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.07.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messina J.L., Fenstermacher D.A., Eschrich S., Qu X., Berglund A.E., Lloyd M.C., Schell M.J., Sondak V.K., Weber J.S., and Mulé J.J.. 2012. 12-Chemokine gene signature identifies lymph node-like structures in melanoma: potential for patient selection for immunotherapy? Sci. Rep. 2:765 10.1038/srep00765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montaldo E., Teixeira-Alves L.G., Glatzer T., Durek P., Stervbo U., Hamann W., Babic M., Paclik D., Stölzel K., Gröne J., et al. . 2014. Human RORγt+CD34+ cells are lineage-specified progenitors of group 3 RORγt+ innate lymphoid cells. Immunity. 41:988–1000. 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monticelli L.A., Sonnenberg G.F., Abt M.C., Alenghat T., Ziegler C.G.K., Doering T.A., Angelosanto J.M., Laidlaw B.J., Yang C.Y., Sathaliyawala T., et al. . 2011. Innate lymphoid cells promote lung-tissue homeostasis after infection with influenza virus. Nat. Immunol. 12:1045–1054. 10.1038/ni.2131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortha A., Chudnovskiy A., Hashimoto D., Bogunovic M., Spencer S.P., Belkaid Y., and Merad M.. 2014. Microbiota-dependent crosstalk between macrophages and ILC3 promotes intestinal homeostasis. Science. 343:1249288 10.1126/science.1249288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niess J.H., and Adler G.. 2010. Enteric flora expands gut lamina propria CX3CR1+ dendritic cells supporting inflammatory immune responses under normal and inflammatory conditions. J. Immunol. 184:2026–2037. 10.4049/jimmunol.0901936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohne Y., Silver J.S., Thompson-Snipes L., Collet M.A., Blanck J.P., Cantarel B.L., Copenhaver A.M., Humbles A.A., and Liu Y.-J.. 2016. IL-1 is a critical regulator of group 2 innate lymphoid cell function and plasticity. Nat. Immunol. 17:646–655. 10.1038/ni.3447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saeed A.I., Sharov V., White J., Li J., Liang W., Bhagabati N., Braisted J., Klapa M., Currier T., Thiagarajan M., et al. . 2003. TM4: a free, open-source system for microarray data management and analysis. Biotechniques. 34:374–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanos S.L., Bui V.L., Mortha A., Oberle K., Heners C., Johner C., and Diefenbach A.. 2009. RORγt and commensal microflora are required for the differentiation of mucosal interleukin 22-producing NKp46+ cells. Nat. Immunol. 10:83–91. 10.1038/ni.1684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satoh-Takayama N., Lesjean-Pottier S., Vieira P., Sawa S., Eberl G., Vosshenrich C.A.J., and Di Santo J.P.. 2010. IL-7 and IL-15 independently program the differentiation of intestinal CD3−NKp46+ cell subsets from Id2-dependent precursors. J. Exp. Med. 207:273–280. 10.1084/jem.20092029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satoh-Takayama N., Serafini N., Verrier T., Rekiki A., Renauld J.-C., Frankel G., and Di Santo J.P.. 2014. The chemokine receptor CXCR6 controls the functional topography of interleukin-22 producing intestinal innate lymphoid cells. Immunity. 41:776–788. 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields J.D., Kourtis I.C., Tomei A.A., Roberts J.M., and Swartz M.A.. 2010. Induction of lymphoidlike stroma and immune escape by tumors that express the chemokine CCL21. Science. 328:749–752. 10.1126/science.1185837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver J.S., Kearley J., Copenhaver A.M., Sanden C., Mori M., Yu L., Pritchard G.H., Berlin A.A., Hunter C.A., Bowler R., et al. . 2016. Inflammatory triggers associated with exacerbations of COPD orchestrate plasticity of group 2 innate lymphoid cells in the lungs. Nat. Immunol. 17:626–635. 10.1038/ni.3443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnenberg G.F., and Artis D.. 2015. Innate lymphoid cells in the initiation, regulation and resolution of inflammation. Nat. Med. 21:698–708. 10.1038/nm.3892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spits H., Artis D., Colonna M., Diefenbach A., Di Santo J.P., Eberl G., Koyasu S., Locksley R.M., McKenzie A.N.J., Mebius R.E., et al. . 2013. Innate lymphoid cells—a proposal for uniform nomenclature. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 13:145–149. 10.1038/nri3365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tugues S., Burkhard S.H., Ohs I., Vrohlings M., Nussbaum K., Vom Berg J., Kulig P., and Becher B.. 2015. New insights into IL-12-mediated tumor suppression. Cell Death Differ. 22:237–246. 10.1038/cdd.2014.134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Gassen S., Callebaut B., Van Helden M.J., Lambrecht B.N., Demeester P., Dhaene T., and Saeys Y.. 2015. FlowSOM: Using self-organizing maps for visualization and interpretation of cytometry data. Cytometry A. 87:636–645. 10.1002/cyto.a.22625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- vom Berg J., Vrohlings M., Haller S., Haimovici A., Kulig P., Sledzinska A., Weller M., and Becher B.. 2013. Intratumoral IL-12 combined with CTLA-4 blockade elicits T cell-mediated glioma rejection. J. Exp. Med. 210:2803–2811. 10.1084/jem.20130678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vonarbourg C., Mortha A., Bui V.L., Hernandez P.P., Kiss E.A., Hoyler T., Flach M., Bengsch B., Thimme R., Hölscher C., et al. . 2010. Regulated expression of nuclear receptor RORγt confers distinct functional fates to NK cell receptor-expressing RORγt+ innate lymphocytes. Immunity. 33:736–751. 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.10.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.