Abstract

Chromium and uranium are highly toxic metals that contaminate many natural environments. We investigated their mechanisms of toxicity under anaerobic conditions using nitrate-reducing Pseudomonas stutzeri RCH2, which was originally isolated from a chromium-contaminated aquifer. A random barcode transposon site sequencing library of RCH2 was grown in the presence of the chromate oxyanion (Cr[VI]) or uranyl oxycation (U[VI]). Strains lacking genes required for a functional nitrate reductase had decreased fitness as both metals interacted with heme-containing enzymes required for the later steps in the denitrification pathway after nitrate is reduced to nitrite. Cr[VI]-resistance also required genes in the homologous recombination and nucleotide excision DNA repair pathways, showing that DNA is a target of Cr[VI] even under anaerobic conditions. The reduced thiol pool was also identified as a target of Cr[VI] toxicity and psest_2088, a gene of previously unknown function, was shown to have a role in the reduction of sulfite to sulfide. U[VI] resistance mechanisms involved exopolysaccharide synthesis and the universal stress protein UspA. As the first genome-wide fitness analysis of Cr[VI] and U[VI] toxicity under anaerobic conditions, this study provides new insight into the impact of Cr[VI] and U[VI] on an environmental isolate from a chromium contaminated site, as well as into the role of a ubiquitous protein, Psest_2088.

Keywords: anaerobes, nitrate reductase, transposon mutagenesis, metals, heavy, contaminated groundwater

Introduction

The industrial use of chromium for metallic plating, industrial catalysts, and pesticides has led to wide scale environmental contamination (Ayres, 1992). For example, there are high levels of Cr contamination at the Hanford 100-Area in Washington State, a 26-square-mile area along the Columbia River, where several water-cooled plutonium reactors were constructed and operated (Fruchter, 2002). Environmental chromium is problematic since exposure to the element poses significant risks to human health causing skin ulcers, respiratory ailments, allergic reactions and cancer (Grevatt, 1998; Dayan and Paine, 2001). Due to its high toxicity, chromium is considered a priority pollutant and the maximum amount of chromium allowed in drinking water by the US Environmental Protection Agency is 0.1 mg/L (Cheung and Gu, 2007; Gupta et al., 2011).

Chromium exists in several different oxidation states from −4 to +6 with the oxyanion hexavalent state (Cr[VI]) and the oxyanion trivalent state (Cr[III]) being the most stable (Cervantes et al., 2001; Cheung and Gu, 2007). Of these two oxidation states, Cr[VI] is over 1,000-fold more toxic as it is highly soluble and can be transported across membranes via sulfate transport channels (Ohtake and Silver, 1994; Cervantes et al., 2001; Costa, 2003). In contrast, Cr[III] species are largely impermeable (Czakó-Vér et al., 1999). Once inside the cell, there are several ways in which Cr causes toxicity. Cr[VI] is reduced to Cr[V] and Cr[III] by compounds such as glutathione and ascorbic acid, a process that also generates reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Arslan et al., 1987; Costa, 2003; Xu et al., 2004). These intracellular reduced Cr species have additional toxic effects, including Cr[III] binding to cellular proteins and DNA, and the formation of ROS by the reoxidation of Cr[V] (Kortenkamp and O'brien, 1994; Costa, 2003). Cr[VI] toxicity is known to be both mutagenic and carcinogenic causing both frameshift and basepair substitution mutations (Venitt and Levy, 1974; Nishioka, 1975; Petrilli and De Flora, 1977).

Chromate resistance mechanisms involving efflux have been characterized from several different microorganisms (Ramírez-Díaz et al., 2008; Thatoi et al., 2014). The efflux protein ChrA is encoded on plasmids in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Cupriavidus metallidurans (Cervantes-Cervantes et al., 1990; Nies et al., 1990; Alvarez et al., 1999) and transports Cr[VI] to outside of the cell membrane using proton motive force (Alvarez et al., 1999; Pimentel et al., 2002). Other microorganisms respond to Cr exposure by inducing the expression of genes that combat oxidative stress as a defense mechanism. For example, Escherichia coli increases production of ROS detoxification enzymes such as superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase (Ackerley et al., 2006) and Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 generates increased concentrations of thioredoxins and glutaredoxins (Chourey et al., 2006). DNA repair systems are also induced in response to aerobic chromate exposure, including components of the DNA SOS repair system and the Rec system (Ramírez-Díaz et al., 2008).

Uranium is a highly toxic industrial element that contaminates natural environments through processes such as mining and milling (Beneš, 1999). The U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) oversees the monitoring and restoration of uranium contamination at 12 facilities nationwide (Riley and Zachara, 1992). In groundwater, uranium is usually present in either the U[VI] or U[IV] oxidation states. Previous studies have shown that microorganisms can sequester or precipitate uranium extracellularly in several different ways (Marqués et al., 1990; Lovley et al., 1993; Merroun et al., 2003, 2005, 2011; Martins et al., 2010; Thorgersen et al., 2016), but it is unclear if these U immobilization methods act as defense mechanisms for the microorganisms involved.

Herein we report the investigation of chromium and uranium toxicity on a denitrifying bacterium growing under anaerobic conditions. Pseudomonas stutzeri RCH2 (RCH2) was isolated from a Cr-contaminated aquifer at the Hanford 100H site (Han et al., 2010). A random barcode transposon site sequencing (RB-TnSeq) library was created for RCH2 allowing for convenient gene function analysis on a genome wide scale (Wetmore et al., 2015), and this library has been used to determine gene fitness under a number of metal-related conditions, including Mo limitation (Vaccaro et al., 2016b) and Cu/Zn toxicity (Vaccaro et al., 2016a). Herein we grew the RCH2 RB-TnSeq librry under conditions of Cr[VI] and U[VI] stress to determine the main toxicity targets of these metals in RCH2 under denitrifying conditions, and to determine key defense mechanisms RCH2 has against these metals. The resulting fitness data provide new insights into the effects of Cr[VI] and U[VI] on the denitrification pathway, which could impact remediation in sites contaminated with both heavy metals and nitrate. The data also led to the characterization of hypothetical gene psest_2088 in RCH2, which is involved in sulfur assimilation. While there have been many studies on the toxic effects of Cr[VI] and U[VI] using microorganisms grown under aerobic conditions, this is the first in depth look at Cr[VI] and U[VI] toxicity in an anaerobic denitrifying system on a genome wide scale.

Materials and methods

Growth conditions

The basal growth medium had the following composition: 20 mM sodium fumarate, 20 mM NaNO3, 4.7 mM NH4Cl, 1.3 mM KCl, 2 mM MgSO4, 0.2 mM NaCl, 1.2 mM NaHCO3, 5 mM NaH2PO4, 0.1 mM CaCl2 with sterile vitamins and trace elements prepared as described by Widdel and Bak (1992). Initial cultures were grown aerobically. These were then diluted 20-fold into the experimental growth medium. For each experiment, where applicable, the indicated amounts of exogenous sulfur sources, uranyl acetate (U[VI]) and K2Cr2O7 (Cr[VI]) were added to the basal growth medium. Cultures were grown in a 100 well Bioscreen plate with each well containing 400 μL of diluted preculture. The Bioscreen plate was incubated anaerobically or aerobically as indicated at 30°C with continuous shaking in a Bioscreen C (Thermo Labsystems, Milford, MA). In the case of anaerobic growths, the Bioscreen C was placed within an anaerobic chamber (Plas Labs, Lansing, MI) in an atmospheric composition of 95% Ar and 5% H2. Growth was monitored at an absorbance of 600 nm. All experiments were performed in biological duplicate or triplicate, errors bars represent standard deviations.

Mutant library growth

The P. stutzeri RCH2 RB-TnSeq mutant library containing 166,448 single transposon mutations with mapped genome locations (Wetmore et al., 2015) was recovered from a 1 mL, 10% glycerol stock at −80°C by incubating aerobically with shaking (150 rpm) at 30°C for 5.5 h in 125 mL of Luria broth with 50 μg/mL kanamycin in a shake flask to an OD600 of 1.0. A sample of the recovery culture was saved as the pregrowth condition. The fitness growths were carried out in triplicate in the basal growth medium described above except 20 mM sodium lactate was used as a carbon source instead of fumarate, and 0.5 g/L yeast extract were added. No additional metals beyond the trace metals solution were added to the control cultures, while 120 μM K2Cr2O7 (240 μM Cr[VI]) was added to the Cr challenge cultures and 3 mM uranyl acetate (U[VI]) was added to the U challenge cultures. The Cr and U concentrations were chosen as the concentrations that decreased growth (OD600) under the fitness growth conditions approximately 50%. Cultures (5 mL) in sealed anaerobic Hungate tubes with an argon atmosphere were inoculated to an OD600 of 0.02 before incubating with shaking (150 rpm) at 30°C for 5 h. At the end of growth, the OD600 of each culture was recorded and the cultures were saved as postgrowth samples.

DNA isolation, PCR, sequencing, and sequence analysis

The processing of the cultures for DNA isolation, DNA sequencing, and sequence analysis were carried out as previously described with the BarSeq98 method (Wetmore et al., 2015). The Illumina HiSeq system was used to sequence PCR products. Strain fitness defined as the binary logarithm of the ratio of postgrowth to pregrowth relative abundances were calculated for each individual transposon insertion strain. Gene fitness values (w) were calculated as previously described (Wetmore et al., 2015), by averaging the fitness values for strains with insertions in a given gene. Quality control and normalization of data were performed as previously reported (Wetmore et al., 2015; Vaccaro et al., 2016a). The quality of each experiment was evaluated using several criteria. Including, the number of counts for the median gene needed to be greater than or equal to 50, and the median absolute difference in fitness between the two havles of the genes (mad12) was less than or equal to 0.5. Quality metrics for the fitness data are reported for each growth condition in Table S1.

Generation of deletion mutant strain Δ2088

The marker-exchange deletion strain, Δ2088, used in this study was constructed by conjugation of an unstable, marker-exchange plasmid into RCH2 with selection for Kanr, in a manner previously described (Vaccaro et al., 2016a). The plasmid was made with the primers found in Table S2.

Reduced intracellular thiol assay

Cultures (300 mL) of P. stutzeri RCH2 wild-type and Δ2088 were grown in triplicate anaerobically on basal medium in sealed bottles at 30°C with or without 50 μM K2Cr2O7 as indicated to late log phase. The cultures were harvested by centrifugation for 10 min at 4°C and 7,500 RPM. Cell pellets were moved into an anaerobic chamber (Coy Laboratory Products, Grass Lake, MI), with an atmospheric composition of 95% Ar and 5% H2, where they were washed once with 50 mM Tris pH 8.0, and suspended in the same buffer at a volume of 3 mL to 1 g of pellet (wet weight). Lysozyme (0.1 mg/mL) and deoxy ribonuclease (0.1 mg/mL) were added to the cell suspensions, which were then lysed by sonication and centrifuged at 10,000 RPM for 10 min. The supernatant was saved as cell free extract, and the Bradford assay was used to quantitate protein concentration (Bradford, 1976).

Total free thiol concentrations were measured from the cell free extracts using the Ellman assay (Sedlak and Lindsay, 1968). Briefly, 20 μL of cell free extract was combined with 75 μL of 30 mM Tris, 3 mM EDTA pH 8.2; 25 μL of 150 μM DTNB dissolved in methanol; and 400 μL of methanol. Samples were spun at 7.5 rpm for 5 min and 270 μL were transferred to a microplate for absorption measurement at 412 nm. A standard curve of reduced glutathione dissolved in 20 mM triethanolamine-HCl was used to convert absorbance values to moles of reduced thiol groups/g protein. Error is reported as the standard deviation between biological triplicates.

Whole cell nitrite reductase assays

RCH2 cultures (5 mL) were grown anaerobically in crimp sealed Hungate tubes under a 100% argon atmosphere with shaking (150 rpm) at 30°C for 5 h. Cultures in triplicate contained either no additional metal, 3 mM uranyl acetate, or 120 μM K2Cr2O7. Preparation of whole cells and nitrite reductase assays were performed as previously described (Thorgersen and Adams, 2016). Nitrite reductase values are reported as Units/mg protein, where a unit corresponds to 1 nmol of nitrite reduced/min.

Results/discussion

Experimental approach and analysis of RB-TnSeq data

Fitness experiments were conducted using the previously described RCH2 RB-TnSeq mutant library containing 166,448 single transposon mutations with mapped genome locations (Wetmore et al., 2015). The library was grown anaerobically using fumarate (20 mM) as the carbon source under denitrifying conditions with 20 mM nitrate in the presence of either no additional metal (control), 120 μM K2Cr2O7 (Cr[VI]) or 3 mM uranyl acetate (U[VI]). Metal concentrations were selected that would inhibit growth of RCH2 by approximately 50%. Gene fitness values (w) are a measure of the population of mutants with disruptions in an individual gene relative to the overall mutant library population and these were calculated for each gene under all growth conditions as previously described (Wetmore et al., 2015). An increase in the relative abundance of mutants in a given gene in the test condition compaired to the pregrowth condition results in a positive fitness value and a decrease results in a negative fitness value. Both the Cr[VI] and U[VI] challenge growth gene fitness values were compared to the control grown in the absence of these metals to determine genes whose fitness was increased or decreased as a result of the metal challenge. Gene fitness values for the Cr[VI] (wCr) and U[VI] (wU) challenges that have been corrected by the control gene fitness values (wCont) will be referred to by the symbols ΔwCr and ΔwU. Genes with ΔwCr and ΔwU ≤ −1.0 are listed in Tables 1, 2 respectively. Genes with ΔwCr and ΔwU values ≥1.0 are listed in Tables S3, S4 respectively. Analysis of the potential influence of polar effects in the RCH2 mutant library was previously conducted (Wetmore et al., 2015), and it was conluded that they do not have a major effect. The false discovery rate for genes with phenotypes was also estimated for the library, and the rate was under 2% (Wetmore et al., 2015).

Table 1.

Genes with ΔwCr ≤ −1.

| Locus Tag | Gene Function | wctrl | wctrl | wCr | wCr | ΔwCr |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AVE | STDEV | AVE | STDEV | Delta | ||

| DNA REPAIR | ||||||

| Psest_3090 | DNA repair protein, RecO | −0.2 | 0.1 | −2.1 | 0.4 | −1.9 |

| Psest_0004 | DNA repair protein, RecF | −0.2 | 0.1 | −2.1 | 0.1 | −1.9 |

| Psest_2545 | Recombination protein, RecR | −0.2 | 0.3 | −2.0 | 0.5 | −1.8 |

| Psest_2646 | SOS regulatory protein, LexA repressor | −0.5 | 0.4 | −2.2 | 1.0 | −1.7 |

| Psest_0212 | Exodeoxyribonuclease V, RecC | 0.6 | 0.8 | −1.0 | 0.5 | −1.6 |

| Psest_2259 | Excinuclease ABC, UvrC | 0.2 | 0.1 | −1.2 | 0.1 | −1.4 |

| Psest_2872 | DNA repair protein, RecA | −0.7 | 0.8 | −2.0 | 0.4 | −1.3 |

| Psest_2647 | SOS-response cell division inhibitor, SulA | −0.2 | 0.1 | −1.6 | 0.2 | −1.3 |

| SULFUR ASSIMILATION | ||||||

| Psest_4316 | ABC-type Methionine transport system | −0.7 | 0.3 | −3.7 | 0.4 | −3.0 |

| Psest_2088 | Uncharacterized protein conserved in bacteria | −0.4 | 1.3 | −2.7 | 0.7 | −2.3 |

| Psest_0494 | Rhodanese-related sulfurtransferase | −0.2 | 0.0 | −2.4 | 0.1 | −2.1 |

| Psest_4314 | ABC-type methionine transport system, MetN | −0.6 | 0.1 | −2.6 | 0.3 | −2.0 |

| Psest_4315 | ABC-type Methionine transport system | −0.8 | 0.5 | −2.3 | 0.4 | −1.5 |

| Psest_4063 | Sulfate ABC transporter | 0.2 | 0.2 | −0.8 | 0.2 | −1.0 |

| NITRATE REDUCTION AND MO COFACTOR BIOSYNTHESIS | ||||||

| Psest_3482 | Parvulin-like peptidyl-prolyl isomerase | −0.3 | 0.3 | −2.6 | 0.5 | −2.3 |

| Psest_0811 | Heme d1 biosynthesis radical SAM protein, NirJ | −0.5 | 0.1 | −2.2 | 0.2 | −1.7 |

| Psest_3481 | MoCo biosynthesis protein A, MoaA | −0.4 | 0.3 | −1.9 | 0.1 | −1.5 |

| Psest_3480 | MoCo biosynthesis protein B, MoaB | −1.6 | 0.6 | −3.0 | 1.6 | −1.4 |

| Psest_3479 | MoCo synthesis domain, MoeA | −2.1 | 0.3 | −3.4 | 0.1 | −1.3 |

| Psest_3000 | Molybdate ABC transporter | −1.2 | 0.2 | −2.3 | 0.2 | −1.2 |

| Psest_3486 | Respiratory nitrate reductase, NarG | −1.8 | 0.1 | −2.9 | 0.2 | −1.1 |

| Psest_3485 | Nitrate reductase, NarH | −2.1 | 0.1 | −3.1 | 0.1 | −1.0 |

| HYPOTHETICAL | ||||||

| Psest_2557 | Protein of unknown function (DUF2474) | 0.0 | 0.6 | −1.6 | 0.7 | −1.6 |

| Psest_3230 | Uncharacterized conserved protein | −0.2 | 0.1 | −1.6 | 0.5 | −1.4 |

| Psest_0820 | Hypothetical protein | −0.7 | 0.1 | −2.1 | 0.4 | −1.4 |

| Psest_2090 | Protein of unknown function (DUF2970) | −0.4 | 0.2 | −1.7 | 0.2 | −1.3 |

| Psest_2756 | Hypothetical protein | 0.5 | 0.4 | −0.7 | 0.4 | −1.2 |

| Psest_2026 | Uncharacterized conserved protein | −0.4 | 0.2 | −1.5 | 0.2 | −1.2 |

| Psest_1920 | Uncharacterized conserved protein | −0.9 | 0.5 | −2.1 | 0.4 | −1.2 |

| Psest_2324 | Hypothetical protein | −0.9 | 0.2 | −2.1 | 0.1 | −1.1 |

| Psest_2561 | Hypothetical protein | −0.2 | 0.3 | −1.2 | 0.7 | −1.1 |

| Psest_1563 | Protein of unknown function (DUF548) | 0.0 | 0.5 | −1.0 | 0.2 | −1.0 |

| OTHER | ||||||

| Psest_1957 | Outer membrane porin, OprD family. | −0.2 | 0.1 | −3.2 | 0.4 | −3.0 |

| Psest_3301 | Predicted transcriptional regulator | −1.8 | 0.2 | −4.2 | 0.9 | −2.4 |

| Psest_3721 | Malic enzyme | −0.2 | 0.1 | −1.9 | 0.4 | −1.7 |

| Psest_1231 | Na+/H+ antiporter, NhaD | −0.4 | 0.2 | −2.1 | 0.2 | −1.7 |

| Psest_2975 | tRNA_Arg_CCT | 0.5 | 0.3 | −1.1 | 0.1 | −1.6 |

| Psest_0815 | Cytochrome C, NirS | −0.5 | 0.2 | −2.1 | 0.1 | −1.6 |

| Psest_0830 | cAMP-binding proteins | −0.8 | 0.2 | −2.4 | 0.5 | −1.5 |

| Psest_0821 | Cytochrome D1 heme domain, NirF | −0.6 | 0.1 | −2.1 | 0.2 | −1.5 |

| Psest_1873 | Predicted permease, DMT superfamily | 0.3 | 0.4 | −1.2 | 0.3 | −1.5 |

| Psest_0817 | Ethylbenzene dehydrogenase. | −0.7 | 0.1 | −2.1 | 0.4 | −1.5 |

| Psest_0823 | Transcriptional regulators | −0.6 | 0.4 | −2.1 | 0.2 | −1.5 |

| Psest_0449 | Glutamine synthetase adenylyltransferase | −0.2 | 0.1 | −1.7 | 0.1 | −1.4 |

| Psest_0855 | NAD-dependent aldehyde dehydrogenases | −0.8 | 0.2 | −2.2 | 0.1 | −1.4 |

| Psest_2325 | alpha-L-glutamate ligase-related protein | −0.6 | 0.3 | −2.0 | 0.4 | −1.4 |

| Psest_2285 | ATP-dependent protease La | 0.2 | 1.0 | −1.1 | 0.2 | −1.4 |

| Psest_2027 | ATP-dependent Clp protease, ClpA | 0.0 | 0.1 | −1.4 | 0.2 | −1.3 |

| Psest_3731 | Exopolyphosphatase | −0.4 | 0.1 | −1.7 | 0.0 | −1.3 |

| Psest_1824 | Sugar transferase | 0.2 | 1.5 | −1.1 | 0.1 | −1.2 |

| Psest_0956 | Transcriptional regulators | 0.1 | 0.2 | −1.1 | 0.1 | −1.2 |

| Psest_1888 | Sua5/YciO/YrdC/YwlC family protein | 1.4 | 0.8 | 0.3 | 0.7 | −1.1 |

| Psest_1640 | (p)ppGpp synthetase, RelA/SpoT family | −0.2 | 0.1 | −1.3 | 0.0 | −1.1 |

| Psest_0822 | Transcriptional regulators | −0.3 | 0.6 | −1.4 | 0.2 | −1.1 |

| Psest_0759 | Protein-L-isoaspartate O-methyltransferase | 0.7 | 0.8 | −0.3 | 0.8 | −1.0 |

| Psest_1944 | NAD-specific glutamate dehydrogenase | 0.0 | 0.1 | −1.0 | 0.1 | −1.0 |

| Psest_1819 | Nucleoside-diphosphate-sugar epimerases | −0.6 | 0.1 | −1.5 | 0.2 | −1.0 |

| Psest_0346 | Putative solute:sodium symporter small subunit | 0.3 | 0.5 | −0.7 | 0.2 | −1.0 |

Table 2.

Genes with ΔwU ≤ −1.

| Locus Tag | Gene Function | wctrl | wctrl | wU | wU | ΔwU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AVE | STDEV | AVE | STDEV | Delta | ||

| NITRATE REDUCTION AND MO COFACTOR BIOSYNTHESIS | ||||||

| Psest_3480 | MoCo biosynthesis protein B, MoaB | −1.6 | 0.6 | −5.2 | 1.2 | −3.5 |

| Psest_1724 | Anti-anti-sigma regulatory factor | −1.5 | 0.4 | −4.2 | 0.7 | −2.7 |

| Psest_0393 | Methylase of chemotaxis methyl-accepting proteins | −2.2 | 0.4 | −4.5 | 0.6 | −2.2 |

| Psest_3479 | MoCo synthesis domain, MoeA | −2.1 | 0.3 | −4.4 | 0.1 | −2.2 |

| Psest_1115 | MoCo biosynthesis, MoeB | −2.6 | 0.6 | −4.6 | 0.5 | −2.0 |

| Psest_3486 | Respiratory nitrate reductase, NarG | −1.8 | 0.1 | −3.6 | 0.2 | −1.8 |

| Psest_1961 | molybdopterin-guanine dinucleotide biosyn, MobA | −2.4 | 0.2 | −4.1 | 0.3 | −1.7 |

| Psest_3485 | Nitrate reductase, NarH | −2.1 | 0.1 | −3.7 | 0.2 | −1.5 |

| Psest_3484 | Nitrate reductase MoCo assembly chaperone | −1.8 | 0.4 | −3.3 | 0.5 | −1.5 |

| Psest_3490 | Signal transduction histidine kinase, nitrate/nitrite | −1.2 | 0.9 | −2.7 | 0.6 | −1.5 |

| Psest_3483 | Respiratory nitrate reductase, NarI | −2.4 | 0.1 | −3.8 | 0.1 | −1.4 |

| Psest_3170 | MoCo biosynthesis protein, MoaC | −2.5 | 0.5 | −3.8 | 0.2 | −1.3 |

| Psest_3000 | Molybdate ABC transporter | −1.2 | 0.2 | −2.4 | 0.1 | −1.2 |

| Psest_2999 | Molybdate ABC transporter | −1.4 | 0.5 | −2.5 | 0.5 | −1.1 |

| HYPOTHETICAL | ||||||

| Psest_3489 | Hypothetical protein | −1.3 | 0.0 | −2.9 | 0.1 | −1.5 |

| Psest_3766 | Uncharacterized conserved protein | −0.3 | 1.2 | −1.6 | 0.3 | −1.3 |

| Psest_2324 | Hypothetical protein | −0.9 | 0.2 | −2.2 | 0.5 | −1.2 |

| Psest_0193 | Conserved hypothetical protein | −1.0 | 0.4 | −2.2 | 0.2 | −1.2 |

| Psest_3881 | Hypothetical protein | 0.3 | 0.2 | −0.7 | 0.2 | −1.0 |

| OTHER | ||||||

| Psest_2232 | UTP-glucose-1-phosphate uridylyltransferase | −0.2 | 0.0 | −4.5 | 0.2 | −4.3 |

| Psest_0993 | Glucose-6-phosphate isomerase | −0.7 | 0.1 | −3.1 | 0.3 | −2.3 |

| Psest_3488 | Universal stress protein, UspA | −1.2 | 0.4 | −3.0 | 0.1 | −1.9 |

| Psest_2325 | alpha-L-glutamate ligase-related protein | −0.6 | 0.3 | −2.3 | 0.2 | −1.7 |

| Psest_1805 | Integration host factor, IhfB | −0.6 | 0.8 | −2.3 | 0.7 | −1.7 |

| Psest_1888 | Sua5/YciO/YrdC/YwlC family protein | 1.4 | 0.8 | −0.2 | 0.4 | −1.6 |

| Psest_3960 | 3′(2′),5′-bisphosphate nucleotidase, bacterial | 0.5 | 0.5 | −0.9 | 0.1 | −1.4 |

| Psest_4010 | Peroxiredoxin, OsmC subfamily | 0.6 | 1.4 | −0.7 | 0.6 | −1.4 |

| Psest_1511 | Predicted redox protein | −1.3 | 0.2 | −2.4 | 0.1 | −1.1 |

| Psest_1974 | Integration host factor, IhfA | −1.0 | 0.3 | −2.1 | 0.2 | −1.1 |

| Psest_0999 | Response regulator | −0.7 | 0.5 | −1.8 | 0.5 | −1.1 |

| Psest_1663 | Pyruvate/2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase complex | −1.3 | 0.3 | −2.4 | 0.2 | −1.1 |

| Psest_1293 | VanZ like family | 0.1 | 0.3 | −1.0 | 0.2 | −1.0 |

Chromate toxicity involving DNA repair and ROS detoxification

In response to exposure to Cr[VI], negative ΔwCr values were observed for a large number of genes involved in DNA repair. These included recF (−1.9), recO (−1.9), recR (−1.8), and recA (−1.3), which are all part of the RecFOR pathway involved in homologous recombination to repair single strand breaks (Morimatsu and Kowalczykowski, 2003). The gene uvrC involved in nucleotide excision repair also had a large negative ΔwCr (−1.4), as did the genes of the other proteins involved in excision repair, uvrA and uvrB, that had ΔwCr values of −0.8 each. The gene of a helicase involved in double stranded repair processes, RecC, had a ΔwCr value of −1.6. Interestingly, the gene encoding the SOS response repressor of LexA also had a large negative ΔwCr value (−1.7) indicating that uncontrolled SOS repair under conditions of Cr[VI] stress is detrimental. The SOS-response cell division inhibitor gene sulA, also had a large negative ΔwCr (−1.3).

Some of the DNA repair fitness data seen anaerobically with RCH2 in the Cr[VI] challenge mirror what has been seen in other microorganisms under aerobic conditions. For example, in E. coli, several SOS genes, including those encoding RecA and a cell division inhibitor, had increased transcription upon Cr[VI] challenge (Llagostera et al., 1986) and in C. crescentus, whole-genome transcriptional analysis in response to chromate toxicity revealed upregulation of some of the components of the excision repair system (Hu et al., 2005). In S. oneidensis MR-1, Cr[VI] exposure resulted in the upregulation of numerous DNA repair related genes including recO, that had a large negative ΔwCr value (−1.9) here but homologs of several upregulated genes in S. oneidensis had no significant fitness value change in RCH2 including uvrD (0.1) (Chourey et al., 2006).

When grown aerobically in the presence of Cr[VI], many organisms induce production of enzymes known to detoxify ROS, including SOD, catalase (Ackerley et al., 2006), thioredoxin and glutaredoxin (Hu et al., 2005; Chourey et al., 2006). None of the homologs of these genes in RCH2 had significantly negative ΔwCr values when exposed to Cr[VI] anaerobically, including those encoding SOD (0.2), five catalases (0.0–0.3), seven glutaredoxins (0.1–0.2), and five thioredoxins (0.0–0.2). This indicates that the anaerobic approach described herein is an efficient means to deconstruct the direct effects that chromium has on DNA damage from the indirect effects that are mediated by ROS when Cr[VI] exposure occurs in the presence of O2.

Chromate toxicity involving nitrate reduction and Mo cofactor biosynthesis

In the present study, the RB-TNSeq library of RCH2 was challenged with Cr[VI] and U[VI] while growing under denitrifying conditions. As a consequence, genes encoding nitrate reductase and other accessory proteins required for nitrate reductase synthesis and function were expected to be important for fitness in RCH2 (Vaccaro et al., 2016a,b). This was confirmed as in the absence of either Cr or U (control) the nitrate reductase structural genes narGHI (psest_3483, psest_3485, and psest_3486) had wCont ranging from −1.8 to −2.4 (Tables 1, 2). In addition, genes encoding proteins involved in synthesis of the Mo-cofactor (Mo-co), a required component of the catalytic site in nitrate reductase, were also expected to have negative wCont, and this proved to be the case. The two Mo-co genes (psest_3479 and psest_3480) that are part of the nitrate reductase operon and encode MoeA and MoaB had wCont of −2.1 and −1.6 respectively. Similarly, two unlinked Mo-co genes that encode MoeB and MobA (psest_1115 and psest_1961) had wCont values of −2.6 and −2.4 respectively.

In the Cr challenge experiments, many genes involved in nitrate reduction had even larger negative fitness values than those that were measured in the absence of Cr (Table 1). These included the nitrate reductase structural genes narG (−1.1) and narH (−1.0), Mo-co biosynthesis genes moaA (−1.5), moaB (−1.4), moeA (−1.3), and a component of the molybdate ABC transporter (−1.2) (Table 1). These results show that Cr[VI] interferes with RCH2 growth under denitrifying conditions when nitrate reductase activity is decreased or eliminated. We propose that RCH2 strains lacking nitrate reductase activity survive in the library control growth, albeit with lower fitness, by using the rest of the denitrification pathway to respire (Figure 1). In this case, the presence of Cr[VI] could interfere with a component of the denitrification pathway whose action takes place after nitrate is reduced to nitrite. The likely target(s) of Cr[VI] toxicity in the remainder of the denitrification pathway are one or more of the several cytochrome containing enzymes involved, such as NirS (cytochrome cd1), a nitrite reductase, or NorBC, the cytochrome b and c subunits of Nor, required for nitric oxide respiration (Figure 1). From a previous study, the reduction of Cr[VI] in RCH2 under anaerobic conditions was shown to require the presence of nitrate, indicating that a component of the denitrification pathway is involved (Han et al., 2010). It has also been observed that other organisms reduce Cr[VI] under anaerobic conditions using cytochrome components of electron transport chains (Mangaiyarkarasi et al., 2011; Joutey et al., 2015). If Cr[VI] is reduced by RCH2 denitrification cytochromes at the expense of their normal activities, this could represent a Cr[VI] toxicity target in RCH2 (Figure 1).

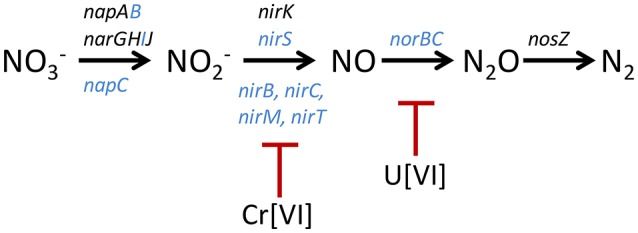

Figure 1.

Model of interactions between the denitrification pathway and Cr[VI] and U[VI]. The denitrification pathway is displayed in black with genes encoding structural proteins located above the pathway, and other cytochrome accessory proteins involved in each step located below the pathway. All genes that encode cytochrome proteins are colored blue (Zumft, 1997). Cr[VI] is shown inhibiting the denitrification pathway at the step of nitrite reduction as evidenced by whole cell assays, and U[VI] is hypothesized to inhibit at the step of nitric oxide reduction. The structural genes are; periplasmic nitrate reductase (nap), nitrate reductase (nar), nitrite reductase (nir), nitric oxide reductase (nor), and nitrous oxide reductase (nos).

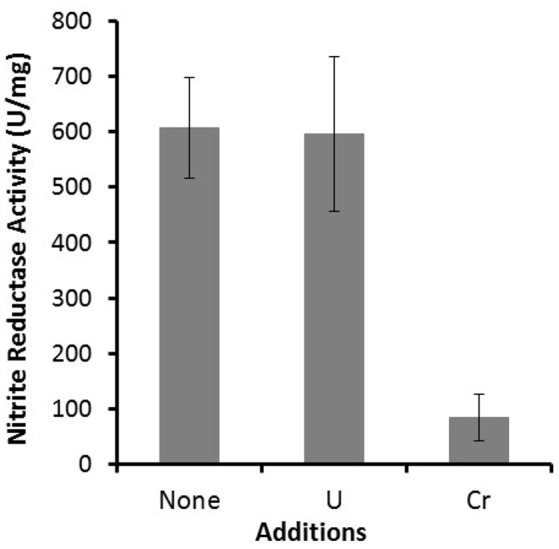

Nitrite reductase activity was measured for RCH2 whole cells grown under denitrifying conditions in the absence and presence of 120 μM K2Cr2O7 and 3 mM uranyl acetate (Figure 2). This was to test the model that Cr[VI] interferes with cytochrome-containing components of the denitrification pathway downstream of nitrate reductase activity, leading to the large negative ΔwCr values seen for nitrate reductase related genes. In support of the model, cells grown in the presence of Cr[VI] had greatly decreased nitrite reductase activity (Figure 2). This indicates that Cr[VI] indeed interferes with nitrite reductase activity, likely through interaction with one or more of the involved cytochrome containing enzymes (NirS, NirB, NirC, NirM, and/or NirT; Figure 1). Many contaminated sites like Hanford, WA, where RCH2 was isolated, and Oak Ridge Reservation, TN are contaminated with both heavy metals like Cr[VI] or U[VI] and nitrate (Riley and Zachara, 1992; Fruchter, 2002). Remediation efforts at sites like these may be complicated by this interaction between metals and the denitrification pathway.

Figure 2.

Nitrite reductase activity was measured for whole RCH2 cells. Cells were grown under anaerobic denitrifying conditions with 20 mM furmarate as a carbon source and 20 mM nitrate as an electron acceptor in the presence of no exogenous metal, 3 mM uranyl acetate or 120 μM K2Cr2O7. Nitrite reductase values are reported as Units/mg protein, where a unit corresponds to 1 nmol of nitrite reduced/min.

Chromate toxicity involving sulfur assimilation and intracellular thiols

Chromate is known to interacts with the sulfur assimilation pathway at multiple levels. One of the major ways in which Cr[VI] enters the cell is through the sulfate transporter system (Cervantes et al., 2001) thereby competing with sulfate transport. In addition, sulfide (H2S) can directly react with and reduce Cr[VI] to the less mobile and less toxic Cr[III] (Kim et al., 2001). Intracellularly, reduced thiols such as glutathione and ascorbic acid can also reduce Cr[VI] (Arslan et al., 1987; Costa, 2003; Xu et al., 2004). These effects of Cr[VI] on sulfur assimilation were demonstrated in anaerobically-grown RCH2 where the growth defect caused by 80 μM K2Cr2O7 was mitigated by the exogenous addition of various sulfur sources (Figure S1). High concentrations (1 mM) but not low concentrations (0.1 mM) of sulfate partially restored growth, presumably by competing with Cr[VI] uptake through the sulfate transport system. Addition of 100 μM H2S also restored growth, presumably by reducing Cr[VI] in the growth medium to the less cell permeable and thus less toxic Cr[III] (Figure S1).

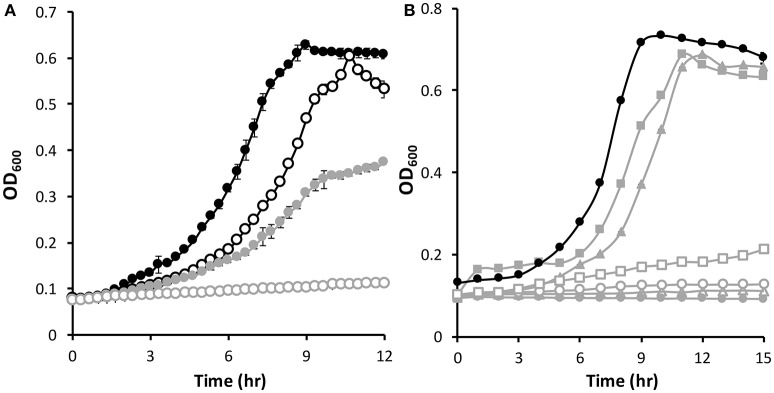

One of the largest negative ΔwCr values observed during the anaerobic Cr[VI] fitness challenge was for the gene encoding the hypothetical protein Psest_2088 (−2.3), which is located directly downstream of the gene encoding the β subunit of sulfite reductase (psest_2089) (no gene fitness data is available for psest_2089), and upstream of another gene of unknown function encoded in the opposite direction. Psest_2088 is predicted to be an intracellular protein with a mass of 19.2 kDa and contains a conserved domain of unknown function found in several bacterial proteins (DUF934 superfamily). A deletion mutant lacking psest_2088 was constructed (Δ2088) and this strain was more sensitive than the wild-type to Cr[VI] (Figure 3A). When grown in the presence of 0.5 g/L yeast extract, the Δ2088 mutant had a growth defect compared to wild-type. However, growth of Δ2088 was severely impaired compaired to wild-type if 25 μM K2Cr2O7 was added to the growth medium (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Anaerobic growth of Pseudomonas stutzeri RCH2 WT (black) and Δ2088 (gray). (A) Growth of WT and Δ2088 in the presence of yeast extract without (filled) and with (open) 25 μM K2Cr2O7 added to the growth medium. (B) Growth of WT and Δ2088 without yeast extract (closed circles) and with various exogenously added sulfur sources: 1 mM sulfate (open triangles), 1 mM sulfite (open circles), 0.3 mM sulfide (closed squares), 0.3 mM cysteine (open squares), and 0.1 mM thiosulfate (closed triangles).

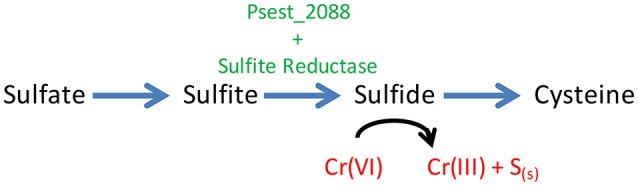

Interestingly, the Δ2088 mutant strain is unable to grow in the absence of 0.5 g/L yeast extract unless an additional sulfur source is added to the growth medium. This is similar to how wild-type behaves when Cr[VI] is present (Figure 3B and Figure S1). Amounts of sulfate and sulfite (1 mM) are unable to correct the growth defect, but 0.3 mM cysteine and sulfide partially restore growth (Figure 3B). Thiosulfate (0.1 mM), a sulfur compound that is enzymatically broken down into sulfide and sulfite (Haschke and Campbell, 1971), also restores growth. This growth restoration profile of sulfur sources is consistent with Psest_2088 having an integral role in sulfite reductase activity since sulfur sources after sulfite reductase in the sulfur assimilation pathway restore growth (sulfide and cysteine) where those before (sulfate and sulfite) do not (Figure 4). One possibility is that Psest_2088 is involved in siroheme biosynthesis, a cofactor required by sulfite reductase. These growth phenotypes of Δ2088 were also seen when the cells were grown aerobically (Figure S2), indicating that the function of Psest_2088 is required both under aerobic and anaerobic growth conditions. Cysteine did not restore growth as well as sulfide likely due to a deleterious effect that cysteine has on RCH2 growth in general.

Figure 4.

Model of the roles of Psest_2088 and Cr(VI) toxicity in sulfur assimilation. The Psest_2088 protein acts as an accessory protein required for sulfite reductase activity. Also shown is the ability of chromate to oxidize intracellular reduced sulfur pools. The combination of decreased sulfite reductase activity and chromate oxidizing the reduced sulfur pool is responsible for the large fitness defect associated with psest_2088 grown in the presence of Cr[VI].

Taken together, these data support a model in which Cr[VI] toxicity is caused at least in part by oxidation of reduced sulfur compounds in the cell or in the oxidation of cellular components that require a reduced sulfur species for function (Figure 4). Strains lacking Psest_2088 have a decreased capacity to reduce sulfite to sulfide and therefore would be more sensitive to Cr[VI] oxidation of intracellular reduced sulfur species. Extracts of RCH2 wild-type cells grown anaerobically in the presence and absence of 50 μM K2Cr2O7 and of Δ2088 were prepared anaerobically and were measured for reduced thiol concentrations. As shown in Figure S3, all of the extracts had comparable concentrations of reduced thiol groups. Although, on the surface the model would predict that the wild-type extract (no Cr[VI] added) should have higher concentrations of reduced thiols than the other extracts, this result is still consistent with the proposed model (Figure 4). RCH2 may strictly maintain a minimum intracellular concentration of reduced thiols during growth and oxidation of thiols by Cr[VI] may result in a slower growth rate rather than in an oxidized intracellular environment.

In addition to psest_2088, a negative ΔwCr value was exhibited by psest_4063 (−1.0), the gene encoding the ATP-binding subunit of the sulfate ABC transporter. The other two genes encoding components of the sulfate transporter psest_4061 (−0.6) and psest_4062 (−0.8) also had negative ΔwCr values. If Cr[VI] enters the cell by multiple transporters and depletes the reduced thiol pool, deletion of a sulfate transporter could have the deleterious effect of decreasing sulfate uptake, even though it may also decrease Cr[VI] uptake. In addition, a gene (psest_0494) annotated as a rhodanese-related sulfurtransferase, putatively involved in the transfer of sulfur containing groups, had a large negative ΔwCr (−2.1). All three genes of the methionine import system, which could provide a source of reduced sulfur, display large negative ΔwCr, psest_4314-4316 (−2.0, −1.5, and −3.0). From the combined data, we propose that the reduced sulfur pool of RCH2 is a target of chromate toxicity (Figure 4).

Chromate toxicity involving chromate reduction

In our study, large negative ΔwCr values were seen for the genes of both cytochrome cd1 nitrite reductase NirS (−1.6), and for NirF (−1.5), a protein needed for NirS maturation (Nicke et al., 2013). If Cr[VI] interferes with nitrate reduction, nitrite reduction, requiring NirS, would become important for respiration and survival. Anaerobic Cr[VI] reduction has been associated with electron transport systems in many organisms with electrons being transferred to Cr[VI] by various cytochromes (Mangaiyarkarasi et al., 2011; Joutey et al., 2015). For example, Desulfovibrio vulgaris soluble cytochrome c3 was shown to be involved in Cr[VI] reduction (Lovley and Phillips, 1994). In a previous study, the reduction rates of Cr[VI] were measured for cell suspensions of RCH2 under both aerobic and anaerobic conditions (Han et al., 2010). In both cases, similar Cr[VI] reduction rates (4–5 × 10−12 μmol. h−1. cell−1) were observed, however, the presence of O2 (in the case of aerobic conditions) or nitrate (in the case of anaerobic conditions) was required for activity in the assay. Cr[VI] reductase activity was not inducible by adding Cr[VI] to the growth medium, and it was concluded that RCH2 could not reduce Cr[VI] unless reducing equivalents for Cr[VI] are first generated in the presence of the physiological electron acceptor (Han et al., 2010).

Chromate toxicity involving chromate efflux

The Cr[VI] efflux protein ChrA has been shown to confer Cr[VI] resistance to P. aeruginosa and other microorganisms (Aguilera et al., 2004; Ramírez-Díaz et al., 2008). RCH2 contains three homologs of ChrA, Psest_1915 and two proteins that are identical in sequence, Psest_0945 and Psest_4025. There was not a negative ΔwCr value for psest_1915 (0.1) and the other two ChrA homologs do not have gene fitness values as no transposon insertions were present in these genes in the RB-TNSeq library. Hence, without further information, the role of efflux in RCH2 Cr[VI] resistance cannot be determined.

Chromate toxicity involving hypothetical proteins

There were ten genes of unknown function with large negative ΔwCr values ranging from −1.0 to −1.6 (Table 1). The function of these proteins in Cr[VI] resistance could be the basis of a future endeavor. Tools such as RB-TNSeq can be used to discover multiple fitness defects for genes of unknown function under diverse conditions, elucidating the roles these proteins have in cellular metabolism.

Uranyl toxicity involving nitrate reduction and Mo-cofactor biosynthesis

In the U challenge experiments, as with the Cr[VI] challenge, genes related to nitrate reduction had large negative ΔwU values (Table 2). These large negative ΔwU values were seen for the denitrification required nitrate reductase structural genes narGHI (−1.4 to −1.8), Mo-co biosynthesis genes moaB (−3.5), moeA (−2.2), mobA (−1.7), moaC (−1.3), and two genes of the molybdate ABC transporter (−1.1 and −1.2). In general, the ΔwU for nitrate reduction related genes were more pronounced and widespread than the ΔwCr. This may simply indicate that the U[VI] challenge was more effective than the Cr[VI] challenge, or uranium toxicity may have a greater effect on this area of metabolism. We propose a similar model for the effect of U[VI] on nitrate reduction gene fitness values as we did for Cr[VI], in that U[VI] likely interacts with cytochromes required for the steps in the denitrification pathway after nitrate is reduced to nitrite (Figure 1). U[VI] reduction by bacteria is not catalyzed by specialized reductases but by redox enzymes that normally function in other cellular processes (Wall and Krumholz, 2006). These include cytochromes such as cytochrome c3 from D. vulgaris (Payne et al., 2002). If U[VI] is reduced by or interacts with one or more of the denitrification cytochromes of RCH2, this could disrupt the later steps of denitrification explaining the large negative ΔwU seen for genes involved in nitrate reduction. Althought U[VI] does not decrease RCH2 whole cell nitrite reductase activity (Figure 2), U[VI] may still interfere with the cytochrome containing nitric oxide reductase resulting in the large negative ΔwU observed for nitrate reductase related genes.

Uranyl toxicity involving stress proteins

A large negative ΔwU value was observed for psest_3488 (−1.9), which encodes the universal stress protein UspA. Expression of the uspA gene has been shown to be up-regulated under several stress conditions in E. coli including starvation, heat, oxidants, metals, uncouplers, ethanol and antibiotics (Kvint et al., 2003). This stress protein also appears to play a role in uranium resistance in RCH2. In E. coli oxidative stress genes including SOD and catalase were also connected with resistance to uranium toxicity under aerobic conditions (Khemiri et al., 2014). In our RCH2 experiment, the gene for SOD and the five annotated catalase genes did not have large negative ΔwU (0.0–0.2), presumably due to the anaerobic growth conditions used in the experiment.

Uranyl toxicity involving exopolysaccharide synthesis

Two genes involved in the formation of polysaccharides had large negative ΔwU values, psest_2232 (−4.3) and psest_0993 (−2.3). They encode UTP-glucose-1-phosphate uridylyltransferase and glucose-6-phosphate isomerase, respectively. These enzymes are involved in the synthesis of UDP-glucose, which is a building block needed to form the polysaccharide glycogen (Alonso et al., 1995). We propose that RCH2 produces an exopolysaccharide using both Psest_2232 and Psest_0993 that is important for uranium resistance. Previously Pseudomonas sp. EPS-5028 and Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans were shown to accumulate uranium on exopolysaccharides under aerobic conditions (Marqués et al., 1990; Merroun et al., 2003), but it was not demonstrated that this accumulation prevented U toxicity. The data presented here supports the idea that under anaerobic conditions, accumulation of uranium on exopolysaccaride constitutes a defense mechanism.

Uranyl toxicity involving hypothetical proteins

There were five hypothetical proteins that had large negative ΔwU values ranging from −1.0 to −1.5 (Table 2). The function of these proteins in uranium resistance is not known and these will be the basis of future research.

Conclusions

Many new insights were gained through the course of this genome-wide fitness analysis on the targets of Cr[VI] and U[VI] toxicity in RCH2 grown under denitrifying conditions, as well as the defense mechanisms RCH2 uses to defend itself against these metals. For Cr[VI], DNA is a toxicity target even under anaerobic conditions. Cr[VI]-dependent fitness defects were seen under anaerobic conditions for strains lacking proteins involved in homologous recombination and nucleotide excision DNA repair. This is a result of direct DNA damage by Cr in the absence of O2, as the generation of DNA damaging ROS is another route of Cr toxicity observed in aerobic experiments (Arslan et al., 1987; Costa, 2003; Xu et al., 2004). Fitness data together with physiological growth studies on wild-type RCH2 and the Δ2088 mutant strain were used to develop a model in which the reduced thiol pool is an additional target of Cr[VI] toxicity (Figure 4). In this model, Psest_2088, a protein of previously unknown function, is a key protein involved in sulfur assimilation at the step of sulfite reduction. Both Cr[VI] and U[VI] toxicity have large fitness effects on RCH2 strains with defects in nitrate reduction. We propose that both metals interfere with cytochrome components of the remainder of the denitrification pathway, which is critical to respiration and survival when nitrate reduction is hindered (Figure 1). This could hinder the remediation of sites contaminated with both nitrate and heavy metals such as Cr[VI] and U[VI]. Finally, exopolysaccharide biosynthesis and the universal stress protein UspA were identified as possible defenses mechanisms against U[VI] toxicity. Cr[VI] and U[VI] damage living organisms in diverse ways, and RB-TnSeq technology is a powerful tool that can be used to study these processes, and identify the metabolic pathways involved.

Originality-significance statement

Much of what has been observed regarding chromium (Cr[VI]) and uranium (U[VI]) toxicity has been studied under aerobic conditions in which metal toxicity is caused not only directly by the metal, but also indirectly due to redox reactions of the metal with oxygen and the resulting reactive oxygen species. Herein we report the results of random barcode transposon site sequencing experiments performed on the chromium-contaminated environmental isolate, Pseudomonas stutzeri RCH2, grown under anaerobic denitrifying conditions. This combined with other techniques has allowed us to elucidate on a genome wide scale the anaerobic toxicity targets of Cr[VI] and U[VI] and the mechanisms used by RCH2 to defend against these metals.

Author contributions

MT, WL, and XG designed and performed the experiments, analyzed and interpreted the data. GZ and AY constructed deletion mutant strains. KW carried out the DNA sequencing and provided support for the RB-TNSeq experiments. MT wrote the manuscript and BV, FP, AD, AA, JW, and MA contributed input and critically reviewed the manuscript. MA supervised the work.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This material by ENIGMA- Ecosystems and Networks Integrated with Genes and Molecular Assemblies (http://enigma.lbl.gov), a Scientific Focus Area Program at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory is based upon work supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Biological and Environmental Research under contract number DE-AC02-05CH11231.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fmicb.2017.01529/full#supplementary-material

References

- Ackerley D., Barak Y., Lynch S., Curtin J., Matin A. (2006). Effect of chromate stress on Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 188, 3371–3381. 10.1128/JB.188.9.3371-3381.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguilera S., Aguilar M. E., Chávez M. P., López-Meza J. E., Pedraza-Reyes M., Campos-García J., et al. (2004). Essential residues in the chromate transporter ChrA of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 232, 107–112. 10.1016/S0378-1097(04)00068-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso M., Lomako J., Lomako W., Whelan W. (1995). A new look at the biogenesis of glycogen. FASEB J. 9, 1126–1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez A. H., Moreno-Sánchez R., Cervantes C. (1999). Chromate efflux by means of the ChrA chromate resistance protein from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 181, 7398–7400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arslan P., Beltrame M., Tomasi A. (1987). Intracellular chromium reduction. BBA Mol. Cell Res. 931, 10–15. 10.1016/0167-4889(87)90044-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayres R. U. (1992). Toxic heavy metals: materials cycle optimization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 89, 815–820. 10.1073/pnas.89.3.815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beneš P. (1999). The environmental impacts of uranium mining and milling and the methods of their reduction, in Chemical Separation Technologies and Related Methods of Nuclear Waste Management. NATO Science Series (Series 2: Environmental Security), eds Choppin G. R., Khankhasayev M. K. (Dordrecht: Springer; ). [Google Scholar]

- Bradford M. M. (1976). A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72, 248–254. 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervantes C., Campos-García J., Devars S., Gutiérrez-Corona F., Loza-Tavera H., Torres-Guzmán J. C., et al. (2001). Interactions of chromium with microorganisms and plants. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 25, 335–347. 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2001.tb00581.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervantes-Cervantes M., Hadjeb N., Newman L. A., Price C. A. (1990). ChrA is a carotenoid-binding protein in chromoplasts of Capsicum annuum. Plant Physiol. 92, 1241–1243. 10.1104/pp.92.4.1241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung K., Gu J.-D. (2007). Mechanism of hexavalent chromium detoxification by microorganisms and bioremediation application potential: a review. Int. Biodeter. Biodegr. 59, 8–15. 10.1016/j.ibiod.2006.05.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chourey K., Thompson M. R., Morrell-Falvey J., Verberkmoes N. C., Brown S. D., Shah M., et al. (2006). Global molecular and morphological effects of 24-hour chromium (VI) exposure on Shewanella oneidensis MR-1. Appl. Environ. Microb. 72, 6331–6344. 10.1128/AEM.00813-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa M. (2003). Potential hazards of hexavalent chromate in our drinking water. Toxicol. Appl. Pharm. 188, 1–5. 10.1016/S0041-008X(03)00011-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czakó-Vér K., Batiè M., Raspor P., Sipiczki M., Pesti M. (1999). Hexavalent chromium uptake by sensitive and tolerant mutants of Schizosaccharomyces pombe. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 178, 109–115. 10.1016/S0378-1097(99)00342-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dayan A., Paine A. (2001). Mechanisms of chromium toxicity, carcinogenicity and allergenicity: review of the literature from 1985 to 2000. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 20, 439–451. 10.1191/096032701682693062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fruchter J. (2002). Peer reviewed: In-situ treatment of chromium-contaminated groundwater. Environ. Sci. Technol. 36, 464A–472A. 10.1021/es022466i [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grevatt P. C. (1998). Toxicological Review of Hexavalent Chromium. Support of Summary Information on the Integrated Risk Information System (IRIS), US Environmental Protection Agency; Washington DC. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta V., Agarwal S., Saleh T. A. (2011). Chromium removal by combining the magnetic properties of iron oxide with adsorption properties of carbon nanotubes. Water Res. 45, 2207–2212. 10.1016/j.watres.2011.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han R., Geller J. T., Yang L., Brodie E. L., Chakraborty R., Larsen J. T., et al. (2010). Physiological and transcriptional studies of Cr (VI) reduction under aerobic and denitrifying conditions by an aquifer-derived pseudomonad. Environ. Sci. Technol. 44, 7491–7497. 10.1021/es101152r [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haschke R. H., Campbell L. L. (1971). Thiosulfate reductase of Desulfovibrio vulgaris. J. Bacteriol. 106, 603–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu P., Brodie E. L., Suzuki Y., Mcadams H. H., Andersen G. L. (2005). Whole-genome transcriptional analysis of heavy metal stresses in Caulobacter crescentus. J. Bacteriol. 187, 8437–8449. 10.1128/JB.187.24.8437-8449.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joutey N. T., Sayel H., Bahafid W., El Ghachtouli N. (2015). Mechanisms of hexavalent chromium resistance and removal by microorganisms, in Reviews of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology Volume 233. Reviews of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology (Continuation of Residue Reviews), ed Whitacre D. (Cham: Springer; ). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khemiri A., Carrière M., Bremond N., Mlouka M. A. B., Coquet L., Llorens I., et al. (2014). Escherichia coli response to uranyl exposure at low pH and associated protein regulations. PLoS ONE 9:e89863. 10.1371/journal.pone.0089863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim C., Zhou Q., Deng B., Thornton E. C., Xu H. (2001). Chromium (VI) reduction by hydrogen sulfide in aqueous media: stoichiometry and kinetics. Environ. Sci. Technol. 35, 2219–2225. 10.1021/es0017007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kortenkamp A., O'brien P. (1994). The generation of DNA single-strand breaks during the reduction of chromate by ascorbic acid and/or glutathione in vitro. Environ. Health Persp. 102:237 10.1289/ehp.94102s3237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvint K., Nachin L., Diez A., Nyström T. (2003). The bacterial universal stress protein: function and regulation. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 6, 140–145. 10.1016/S1369-5274(03)00025-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llagostera M., Garrido S., Guerrero R., Barbé J. (1986). Induction of SOS genes of Escherichia coli by chromium compounds. Environ. Mutagen. 8, 571–577. 10.1002/em.2860080408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovley D. R., Phillips E. J. (1994). Reduction of chromate by Desulfovibrio vulgaris and its c3 cytochrome. Appl. Environ. Microb. 60, 726–728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovley D. R., Widman P. K., Woodward J. C., Phillips E. (1993). Reduction of uranium by cytochrome c3 of Desulfovibrio vulgaris. Appl. Environ. Microb. 59, 3572–3576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangaiyarkarasi M. M., Vincent S., Janarthanan S., Rao T. S., Tata B. (2011). Bioreduction of Cr (VI) by alkaliphilic Bacillus subtilis and interaction of the membrane groups. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 18, 157–167. 10.1016/j.sjbs.2010.12.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marqués A. M., Bonet R., Simon-Pujol M. D., Fusté M. C., Congregado F. (1990). Removal of uranium by an exopolysaccharide from Pseudomonas sp. Appl. Environ. Microb. 34, 429–431. [Google Scholar]

- Martins M., Faleiro M. L., Da Costa A. M. R., Chaves S., Tenreiro R., Matos A. P., et al. (2010). Mechanism of uranium (VI) removal by two anaerobic bacterial communities. J. Hazard Mater. 184, 89–96. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2010.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merroun M. L., Nedelkova M., Ojeda J. J., Reitz T., Fernández M. L., Arias J. M., et al. (2011). Bio-precipitation of uranium by two bacterial isolates recovered from extreme environments as estimated by potentiometric titration, TEM and X-ray absorption spectroscopic analyses. J. Hazard Mater. 197, 1–10. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2011.09.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merroun M. L., Raff J., Rossberg A., Hennig C., Reich T., Selenska-Pobell S. (2005). Complexation of uranium by cells and S-layer sheets of Bacillus sphaericus JG-A12. Appl. Environ. Microb. 71, 5532–5543. 10.1128/AEM.71.9.5532-5543.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merroun M., Hennig C., Rossberg A., Reich T., Selenska-Pobell S. (2003). Characterization of U (VI)-Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans complexes using EXAFS, transmission electron microscopy, and energy-dispersive X-ray analysis. Radiochim. Acta 91, 583–592. 10.1524/ract.91.10.583.22477 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morimatsu K., Kowalczykowski S. C. (2003). RecFOR proteins load RecA protein onto gapped DNA to accelerate DNA strand exchange: a universal step of recombinational repair. Mol. Cell 11, 1337–1347. 10.1016/S1097-2765(03)00188-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicke T., Schnitzer T., Münch K., Adamczack J., Haufschildt K., Buchmeier S., et al. (2013). Maturation of the cytochrome cd1 nitrite reductase NirS from Pseudomonas aeruginosa requires transient interactions between the three proteins NirS, NirN and NirF. Bioscience Rep. 33:e00048. 10.1042/BSR20130043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nies A., Nies D. H., Silver S. (1990). Nucleotide sequence and expression of a plasmid-encoded chromate resistance determinant from Alcaligenes eutrophus. J. Biol. Chem. 265, 5648–5653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishioka H. (1975). Mutagenic activities of metal compounds in bacteria. Mutat. Res.-Envir. Muta. 31, 185–189. 10.1016/0165-1161(75)90088-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohtake H. I. S. A. O., Silver S. (1994). Bacterial detoxification of toxic chromate, in Biological Degradation and Bioremediation of Toxic Chemicals (London: Chapman & Hall; ), 403–415. [Google Scholar]

- Payne R. B., Gentry D. M., Rapp-Giles B. J., Casalot L., Wall J. D. (2002). Uranium reduction by Desulfovibrio desulfuricans strain G20 and a cytochrome c3 mutant. Appl. Environ. Microb. 68, 3129–3132. 10.1128/AEM.68.6.3129-3132.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrilli F. L., De Flora S. (1977). Toxicity and mutagenicity of hexavalent chromium on Salmonella typhimurium. Appl. Environ. Microb. 33, 805–809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pimentel B. E., Moreno-Sánchez R., Cervantes C. (2002). Efflux of chromate by Pseudomonas aeruginosa cells expressing the ChrA protein. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 212, 249–254. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2002.tb11274.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez-Díaz M. I., Díaz-Pérez C., Vargas E., Riveros-Rosas H., Campos-García J., Cervantes C. (2008). Mechanisms of bacterial resistance to chromium compounds. Biometals 21, 321–332. 10.1007/s10534-007-9121-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley R. G., Zachara J. (1992). Chemical Contaminants on DOE Lands and Selection of Contaminant Mixtures for Subsurface Science Research. Richland, WA: Pacific Northwest Lab. [Google Scholar]

- Sedlak J., Lindsay R. H. (1968). Estimation of total, protein-bound, and nonprotein sulfhydryl groups in tissue with Ellman's reagent. Anal. Biochem. 25, 192–205. 10.1016/0003-2697(68)90092-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thatoi H., Das S., Mishra J., Rath B. P., Das N. (2014). Bacterial chromate reductase, a potential enzyme for bioremediation of hexavalent chromium: a review. J. Environ. Manage. 146, 383–399. 10.1016/j.jenvman.2014.07.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorgersen M. P., Adams M. W. (2016). Nitrite reduction assay for whole pseudomonas cells. Bio Protocol 6:e1818 10.21769/BioProtoc.1818 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thorgersen M. P., Lancaster W. A., Rajeev L., Ge X., Vaccaro B. J., Poole F. L., et al. (2016). A highly expressed high molecular weight S-Layer complex of pelosinus strain UFO1 binds Uranium. Appl. Environ. Microb. 83, 3016–3044. 10.1128/AEM.03044-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaccaro B. J., Lancaster W. A., Thorgersen M. P., Zane G. M., Younkin A. D., Kazakov A. E., et al. (2016a). Novel metal cation resistance systems from mutant fitness analysis of denitrifying Pseudomonas stutzeri. Appl. Environ. Microb. 82, 6046–6056. 10.1128/AEM.01845-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaccaro B. J., Thorgersen M. P., Lancaster W. A., Price M. N., Wetmore K. M., Poole F. L., et al. (2016b). Determining roles of accessory genes in denitrification by mutant fitness analyses. Appl. Environ. Microb. 82, 51–61. 10.1128/AEM.02602-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venitt S., Levy L. (1974). Mutagenicity of chromates in bacteria and its relevance to chromate carcinogenesis. Nature 250, 493–495. 10.1038/250493a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wall J. D., Krumholz L. R. (2006). Uranium reduction. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 60, 149–166. 10.1146/annurev.micro.59.030804.121357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetmore K. M., Price M. N., Waters R. J., Lamson J. S., He J., Hoover C. A., et al. (2015). Rapid quantification of mutant fitness in diverse bacteria by sequencing randomly bar-coded transposons. MBio 6, e00306–e00315. 10.1128/mBio.00306-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widdel F., Bak F. (1992). Gram-negative mesophilic sulfate-reducing bacteria, in The Prokaryotes, eds Balows A., Trüper H. G., Dworkin M., Harder W., Schleifer K. H. (New York, NY: Springer; ). [Google Scholar]

- Xu X.-R., Li H.-B., Li X.-Y., Gu J.-D. (2004). Reduction of hexavalent chromium by ascorbic acid in aqueous solutions. Chemosphere 57, 609–613. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2004.07.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zumft W. G. (1997). Cell biology and molecular basis of denitrification. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. R. 61, 533–616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.