Abstract

Using native-state hydrogen-exchange-directed protein engineering and multidimensional NMR, we determined the high-resolution structure (rms deviation, 1.1 Å) for an intermediate of the four-helix bundle protein: Rd-apocytochrome b562. The intermediate has the N-terminal helix and a part of the C-terminal helix unfolded. In earlier studies, we also solved the structures of two other folding intermediates for the same protein: one with the N-terminal helix alone unfolded and the other with a reorganized hydrophobic core. Together, these structures provide a description of a protein folding pathway with multiple intermediates at atomic resolution. The two general features for the intermediates are (i) native-like backbone topology and (ii) nonnative side-chain interactions. These results have implications for important issues in protein folding studies, including large-scale conformation search, φ-value analysis, and computer simulations.

Keywords: hidden folding intermediate, native-state hydrogen exchange, NMR structure, protein engineering, protein structure

To understand how proteins fold, a great deal of experimental work has been done to identify and characterize partially unfolded intermediates that occur during the folding process (1–6). However, a high-resolution structure at atomic resolution for a folding intermediate has not been obtained. The main hurdle is that protein folding is a very fast process (<1 s for small single-domain proteins with ≈100 aa), and therefore, intermediates populate only transiently during kinetic folding. The commonly used spectroscopic probes such as fluorescence and circular dichroism, which can signal fast folding events, provide very limited information to define the structure of folding intermediates. Moreover, partially unfolded intermediates do not populate significantly under equilibrium native conditions because the native state is the most stable structure.

One way to obtain detailed structural information on equilibrium folding intermediates has been to populate partially unfolded states at equilibrium at low pH and characterize them by using amide hydrogen exchange or multidimensional solution NMR (3, 7–9). The best-studied example is the partially folded molten globule of apomyoglobin populated at pH 4.1 (7). This low-pH intermediate has been shown to have structural characteristics that are similar to the intermediate populated during kinetic folding (10, 11). In some cases, it has been possible to prepare peptide fragments to represent stable intermediates and study them by NMR (12, 13). Although the backbone conformation for these intermediate models has been obtained, information for their main-chain interactions and side-chain packing is still lacking.

The most detailed structural information on folding intermediates has come from the native-state hydrogen-exchange (NHX) method. The method is able to detect partially unfolded intermediates that exist only in infinitesimal amounts under native conditions in which the native state is the dominantly populated species (14). By measuring the hydrogen exchange rates of amide protons and their dependence on denaturant concentration, the NHX method can characterize the hydrogen bonding pattern, stability, and surface exposure of partially unfolded intermediates. Multiple partially unfolded intermediates have been identified for a number of proteins, including cytochrome c (14), ribonuclease H* (15), apocytochrome b562 (16), T4 lysozyme (17), Rd-apocytochrome b562 (Rd-apocyt b562) (18), OspA (19), barnase (20), and the third domain of PDZ (21).

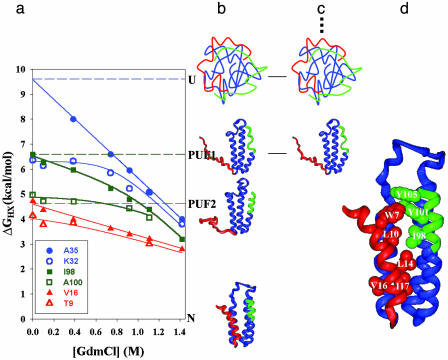

In the case of Rd-apocyt b562, a redesigned stable variant of apocytochrome b562 with a four-helix bundle fold (22), NHX experiments identified two partially unfolded forms (PUFs) (18) (see Fig. 1). PUF1 has the N-terminal helix and a part of the C-terminal helix unfolded. PUF2 has only the N-terminal helix unfolded. In other equilibrium unfolding studies using urea, we identified another intermediate (N*) by monitoring multiple chemical shifts by NMR (23). The structure of N* at 2.8 M urea was solved by high-resolution NMR (23).

Fig. 1.

The use of NHX-directed protein engineering to populate PUF1 of Rd-apocyt b562. (a) Representative NHX results for Rd-apocyt b562 (18). Two color-coded amide protons corresponding to the region of the structural unit in the structure of the native state are shown for each structural unit. The horizontal dashed lines indicate the unfolding free energy of PUF1, PUF2, and the unfolded state at zero denaturant. (b) Structures of the PUFs derived from the complete NHX results. (c) Gly mutations that substitute hydrophobic core residues in the unfolded regions (red and green) of PUF1 destabilize the native state and PUF2 without affecting the stability of the unfolded state and PUF1. Therefore, PUF1 becomes the most stable species. The dashed line indicates that PUF2 and N are high-energy species after the Gly mutations. (d) Structural image of the mutated residues in the native structure of Rd-apocyt b562 for populating PUF1 (59). The side chains of these residues are shown in Corey–Pauling–Kolton models. The Trp at position 7 was mutated to Asp. All other residues were changed to Gly.

In ref. 24, we caused PUF2 to be populated at equilibrium by using an NHX-directed protein-engineering method by substituting some hydrophobic core residues in the N-terminal helix with Gly residues. These mutations destabilize the native state without perturbing the folded regions of PUF1 and PUF2. Accordingly, PUF2 becomes the most stable species. The structure of the PUF2 mimic with Gly mutations in the N-terminal helix was solved by using multidimensional NMR methods (25).

Here, we used the protein-engineering approach to populate PUF1 by further replacing stabilizing hydrophobic residues in the C-terminal helix, in addition to the Gly mutations in the N-terminal helix. The structure of this PUF1 mimic was then solved by using multidimensional NMR. These solution structures found for the PUF1 mimic and the PUF2 mimic closely match the NHX results in respect to main-chain organization, but there are some surprises in respect to side-chain organization, as indicated below.

These results provide a detailed structural characterization of the intermediates in a protein folding pathway at atomic resolution, and they have implications for several other important issues.

Materials and Methods

Sample Preparation. Mutations were made by using the Quik Change kit (Strategene). Expression and purification of the PUF1 mimic followed a procedure described in ref. 18. Isotopically enriched proteins for NMR structure determination were grown on M9 minimal media containing 1 g/liter [U—15N] 15NH4Cl and/or 4 g/liter [U-13C]glucose (Isotec) as the sole sources of nitrogen and carbon for double (13C and 15N)- and/or single (15N or 13C)-labeled proteins. NMR samples included 13C/15N, 15N, 13C, and nonlabeled protein at concentrations of ≈2–3 mM (95% H2O/5% D2O, pH 4.8) with 20 mM NaAc-D4 as buffer.

NMR Spectroscopy. NMR spectra were collected at 15°C on DRX 500-MHz spectrometers (Bruker, Billerica, MA) equipped with a 5-mm x, y, z-shielded pulse field gradient triple resonance probe. A series of 3D experiments [CBCA(CO)NH, HNCACB, HCCH--total correlation spectroscopy (TOCSY), 15N-edited TOCSY, 15N/13C-edited nuclear Overhauser effect (NOE) enhancement spectroscopy (NOESY), 2D 1H NOESY] were collected for complete assignments and 1H-NOE measurement. An HNHA experiment was used to determine 3JαN coupling constants for φ angles (26). For T2 Carr–Purcell–Meiboom–Gill (CPMG) delays, they were as follows: 1, 5000, 2, 2000, 5, 500, 10, 200, 20, 100, and 50 ms, with a duty cycle of 0.45 ms. Steady-state 1H—15N NOE values were determined by recording in the presence (NOE) and absence (NONOE) of 1H saturation for 3 s. NOE and NONOE experiments were interleaved in one experiment. NOE was calculated from the intensities of cross peaks by NOE = INOE/INONOE. NMR data were processed by using nmrpipe (27) and analyzed by using nmrview (28).

Calculation of Structure. Structural calculation was done by using National Institutes of Health x-plor[scap] (version 2.0.6). An extended polypeptide chain of reasonable geometry was used as the initial template. We then randomized the φ and ψ angles before each cycle of simulated annealing (SA) protocol. Each SA structure was optimized by restrained refinement. We selected 10 structures with lower energy and fewer NOE and dihedral angle-violations from 50 SA structures for further refinement. For each starting structure, 10 refined structures (i.e., 100 structures) were calculated. The ones with lowest energy and no NOE and dihedral angle violations from each set were used for a second round of refinement to calculate another 10 structures. This refinement procedure was repeated once more to obtain the final 10 structures with the lowest energy and no violation of restraints. These structures were checked further by using pro-check-nmr (version 3.5.4) (29).

Results and Discussion

Population of PUF1 by NHX-Directed Protein Engineering. Under native conditions, the native protein is the most highly populated form, but proteins must unfold and refold continually and cycle through all possible higher-energy forms. Partially unfolded intermediates whose stability lies between the native and unfolded states can be identified by HX measurements, even though they exist only at miniscule levels because the predominant native state makes no contribution to the HX rates that are measured. Hydrogens can exchange only when their protecting H-bond is broken in some higher energy state.

We measured the HX rates of 33 amide protons as a function of denaturant concentration and plotted their computed ΔGHX values, as shown for some protons in Fig. 1a. As usual, ΔGHX for the transient opening that allows exchange is defined as –RT ln(kex/kch), where kex is the measured exchange-rate constant and kch is the chemical exchange rate for unprotected amide protons in unfolded polypeptide chains (30). Cooperative structure units (foldons) are recognized by the fact that ΔGHX values for all of their amino acids merge when the hidden unfolding reaction is selectively promoted and becomes their dominant HX pathway (Fig. 1a). Unfolding of such cooperative structural units leads to a partially unfolded intermediate. The infinitesimally populated intermediates were detected by the pattern of ΔGHX values of various amide protons at low concentration of denaturant where the native protein is still very stable. The NHX results identify the folded and unfolded regions of each high-energy intermediate (Fig. 1b) and characterize the thermodynamic stability and the surface exposure of each.

Fig. 1 shows the principle for identifying partially unfolded intermediates based on NHX results and then by using protein engineering to destabilize all more stable forms. Mutations that substitute larger stabilizing hydrophobic residues with Gly residues or charged residues are made to destabilize the native state while leaving the folded region of the intermediate unperturbed. Accordingly, the intermediate becomes the most stable state (Fig. 1c), and its structure can be determined by using multidimensional NMR. The structures found for the intermediates made to populate in this way closely match the structures indicated by the NHX results.

In the case of Rd-apocyt b562, two partially unfolded intermediates have been identified by the NHX method. To selectively destabilize the lower free-energy forms and attempt to cause PUF1 to dominate, hydrophobic core residues at seven positions (W7D/L10G/L14G/V16G/I17G/I98G/Y101G/Y105G) in the unfolded regions of PUF1 were mutated to Asp and Gly. Fig. 1d shows the mutation sites in the native structure.

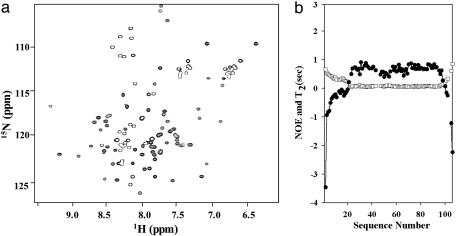

Characterization of the PUF1 Mimic by Backbone 15N Dynamics. Fig. 2a shows the 1H—15N heteronuclear single-quantum correlation spectrum at pH 4.8 and 15°C. The cross peaks were assigned by using triple-resonance methods (see Materials and Methods). Two sets of cross peaks with different intensities are apparent. The peaks with strong intensities are all in the N- and C-terminal regions, whereas the cross peaks with weaker intensities are all in the middle helices and the loop. The values of the transverse relaxation time (T2) for the amide 15N and the hetero-NOE for amide 1H—15N were also measured (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

Dynamic properties of the PUF1 mimic. (a) The 1H—15N, the heteronuclear single-quantum correlation spectrum of the PUF1 mimic. (b) Amide 15N dynamics of the PUF1 mimic at 15°C and pH 4.8. □, T2 values; •, NOEs.

The peaks with strong intensities in the heteronuclear single-quantum correlation spectrum have larger T2 and smaller NOE values, indicating that the mutated regions have very flexible structures, presumably largely unfolded. The peaks with weaker intensities have smaller T2 and larger NOE values, indicating folded regions. The T2 values in the folded region of the molecule are ≈55 ms, consistent with a monomer protein of a ≈12 kDa and a significant part of the structure unfolded at this low temperature. A dimer of ≈24 kDa would have much shorter T2 under such conditions. Also, no chemical-shift changes in the 1H—15N the heteronuclear single-quantum correlation spectrum occur after dilution of a protein sample (≈2 mM) by 100-fold, indicating that the mutant is a monomer at the concentration used for the 15N dynamics studies.

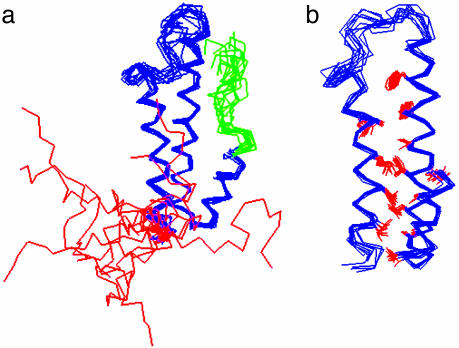

The Molecular Structure of the PUF1 Mimic at Atomic Resolution. We used multidimensional NMR methods to determine the structure of the PUF1 mimic. Chemical shifts of 1H, 15N, and 13C of a double-labeled (15N/13C) protein sample were assigned by using triple-resonance methods (see Materials and Methods). The 1H—1H NOEs, backbone dihedral angles, and chemical shifts were used as constraints for the calculation of structures (see Table 1). Fig. 3a shows 10 NMR structures that are superimposed on the Cα carbons from residues 26 to 94. Fig. 3b shows the conformation of the hydrophobic core residues.

Table 1. Parameters for the structure of the folded region of PUF1 at pH 4.8 and 15°C.

| rms deviation from ideal geometry | |

| Bonds, Å | 0.00457 ± 0.00005 |

| Angles, ° | 0.552 ± 0.010 |

| Impropers, ° | 0.424 ± 0.010 |

| NOE (all), Å | 0.058 ± 0.007 |

| rms deviation from the mean structure* | |

| Backbone atoms | 0.73 (0.48) |

| All heavy atoms | 1.11 (0.90) |

| Experimental constraints | |

| Intraresidues NOE | 450 |

| Sequential NOE (|i — j| < 5) | 771 |

| Long-range NOE (|i — j| ≥ 5) | 85 |

| H-bonds | 86 |

| Dihedral angles | 55 |

| Others | 104 |

All residues (23-97). Values for the helical region are given in parentheses.

Fig. 3.

NMR structure of the PUF1 mimic. (a) Backbone conformation, in which 10 NMR structures are superimposed on the Cα carbons from residues 24 to 94. (b) Some hydrophobic side chains.

The folded region of the structure is very well defined, with an rms deviation of 1.11 Å for all heavy atoms. In contrast, the N-terminal helix and the end of the C-terminal helix with Gly mutations have no identifiable long-range NOEs and show significantly different conformations among the 10 NMR structures. Table 1 gives the parameters describing the constraints and the quality of the structures. An interesting observation is that the C-terminal region appears to be less random, although no long-range NOE constraints in this region were found and used in the calculation of the structures. Thus, the less-randomly populated conformations appear to arise from local constraints defined by the sequential NOEs.

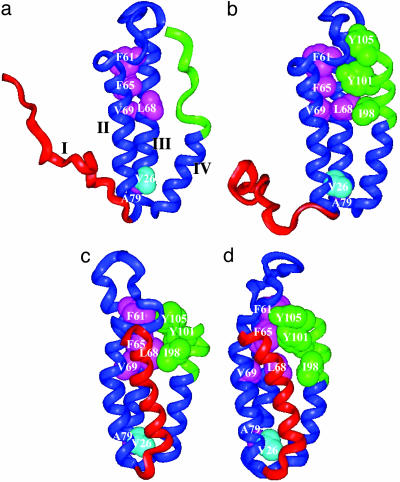

Native-Like Backbone Topology and Nonnative Side-Chain Interactions. Fig. 4 compares the structures of PUF1, PUF2, N*, and the native state. The folded regions of PUF1 are very similar to the corresponding regions of PUF2 and N*. They all retain the native-like backbone topology and secondary structures. However, major nonnative side-chain packing and subtle differences in the secondary structures of the three intermediates are apparent. For example, in the native state, the side chains of residue F61 and F65 face inside the structure and form hydrophobic contacts with Y101 and Y105. However, in the PUF1 and PUF2 intermediates, they rotate ≈180° away from the original hydrophobic core and repack between helix II and helix III. In the case of N*, the situation is reversed. Y101 and Y105 have rotated away and pack between helix III and IV, leaving a cavity in the original hydrophobic core. In the native state, F65 interacts with L68. In PUF1 and PUF2, this packing is lost. Instead, F65 packs with V69. In the native state, L68 and I98 are not in direct contact, but they pack together in PUF2 and N*. Similarly, Y101 has no contact with L68 in the native state but it packs with L68 in PUF2. Helix III is somewhat distorted in the native state and N*, presumably because of the side-chain packing between helix I and helix III. This distortion leads to the slightly different packing between A79 and V26 side chains in the structures of N and N* when compared with those in the PUF1 and PUF2 intermediates. In summary, the common feature of the three intermediates is that they all have a part of the reforming protein with native-like backbone topology and a number of nonnative side-chain interactions.

Fig. 4.

Comparison of the ribbon structures of PUF1 (a), PUF2 (b), N* (c), and N (d). Representative hydrophobic residues are shown in Corey–Pauling–Kolton models. The four helices are labeled with I, II, III, and IV from the N terminus to the C terminus in a.

These structures have immediate implications for interpreting experimental results from amide hydrogen exchange and protein engineering studies. It is commonly assumed that protection of amide hydrogens in protein folding intermediates is due to native-like hydrogen bonding. Similarly, in the φ-value-analysis method, mutational effects on the stability of partially unfolded states (intermediates or transition states) are generally assumed to arise from native-like side-chain interactions. The native-like backbone conformation of the intermediates of Rd-apocyt b562 provides experimental support for the native-like hydrogen bonding assumption. However, the broad nonnative-like side-chain interactions observed in these intermediates indicate that the interpretation of mutation results in terms of native-like side-chain interactions may not be well founded. In addition, we recently have shown that nonnative-like interactions can actually produce fractional φ values in the expected normal range of 0–1 (31). These observations do not support the idea that nonnative interactions may be recognized by nonideal φ values.

The Folding Pathway of Rd-apocyt b562 with Intermediates at Atomic Resolution. In earlier studies on the kinetic folding of Rd-apocyt b562, we found that Rd-apocyt b562 folds in an apparent two-state manner with the absence of detectable folding intermediates. Protein engineering studies indicated that the rate-limiting transition state mainly involves the formation of the two middle helices (18). These results, together with the structures of the three discrete intermediates, suggest that Rd-apocyt b562 folds with an early rate-limiting step (RLS). The intermediates are formed only after the initial RLS; therefore, they are hidden and kinetic folding appears to be a two-state process.

Based on the structure of each species, it seems reasonable to speculate that folding of Rd-apocyt b562 occurs in a sequential manner with the increase of folded structure in each step (i.e., U→RLS→PUF1→PUF2→N*→N). Fig. 5 shows this structure-based folding pathway by using the high-resolution structures of the intermediates and the native state.

Fig. 5.

A putative folding pathway with multiple intermediates at atomic resolution for Rd-apocyt b562. The specific discrete intermediates form sequentially. The order for folding is defined by the nativeness of the intermediates. PUF1, PUF2, N*, and N are represented by 10 structures determined by NMR methods. Aromatic side chains for residues Y101 and Y105 (purple) in N* and N are shown to illustrate their different conformations in the two structures. Note that N* is observed at 2.8 M urea. Its existence in water needs to be demonstrated further.

More direct kinetic experiments will be needed to test the above model. Available experimental results from studies of other proteins support the view that constructive on-pathway intermediates form the folding pathway. For example, by using stability labeling and kinetic NHX, the Englander laboratory has provided strong evidence for a sequential folding pathway in cytochrome c folding (32–38), which also involves multiple folding intermediates (14). Specific demonstrations for other on-pathway intermediates have also been obtained for RNase A (39), cytochrome c (33), lysozyme (40), dihydrofolate reductase (41), IM7 (42), and RNase H* (43).

Hidden Intermediates in Small Single-Domain Proteins. Since the establishment of the thermodynamic hypothesis of protein folding by Anfinsen (44) in the 1960s, a critical issue has been how, in a biologically meaningful time scale, protein molecules find the native state in the enormously large conformational space. A straightforward hypothesis for solving this puzzle has been the existence of folding intermediates (45). For example, assuming that each amino acid contributes three conformations, the total number of conformations for a polypeptide chain with 100 aa is 3100 or 1048. If the transition from one conformation to another takes ≈10–12 s, a random search will take ≈1036 s to find the native state. However, if the molecule folds in four steps and each step involves 25 aa, then the total number of conformations becomes 4 × 325 ≈ 1012. Thus, stepwise folding could find the native state in ≈1 s.

Although kinetic folding intermediates have been identified and characterized to some extent in a number of cases (4), they either involve larger proteins (>120 aa), which could have multiple coupled domains, or other factors that are not intrinsic for protein folding such as proline isomerization (46), disulfide bond formation (47), misligation (48), and aggregation (49–52). These factors slow folding and cause the transient accumulation of intermediate forms. In contrast, studies on smaller proteins (<120 aa) in the absence of these nonintrinsic factors have shown that they generally do not have detectable kinetic folding intermediates (53, 54). These results can be taken to support that the accumulation of folding intermediates represents kinetic traps that impede folding rather than constructive on-pathway forms (55, 56).

Although conventional kinetic studies have failed to detect partially unfolded intermediates for small single-domain proteins, multiple partially unfolded intermediates have been identified for a number of small proteins by the NHX method, as described (14, 16, 18, 20, 21). These observations do not depend on kinetic traps and have the characteristics one expects for constructive on-pathway intermediates that build the native state in a conventional folding pathway. Also, these intermediates exist only after the initial rate-limiting kinetic transition state (18, 20, 21, 57, 58), providing an explanation for why the intermediates are not observed in kinetic folding experiments. Also, the fact that folding remains two-state shows that the hidden intermediates do not serve as kinetic traps. The determination of the three high-resolution structures for the folding intermediates of Rd-apocyt b562 in the absence of any complicating factors further provides evidence for the existence of multiple specific discrete folding intermediates.

Summary. High-resolution structures of several partially unfolded intermediates have been obtained for Rd-apocyt b562. They have native-like backbone conformation and topology and nonnative side-chain interactions. The determination of these structures provides further evidence for the existence of partially unfolded intermediates in the folding of a single-domain protein and displays a putative folding pathway at high resolution. Analogous results have been found by the NHX method for other single-domain proteins. These results strongly suggest that proteins solve the large-scale conformational search problem by folding in a stepwise-pathway manner through discrete intermediate forms. Further, the nonnative side-chain interactions in the intermediates have implications for the interpretation of φ values measured in protein engineering studies. Last, the high-resolution structures of these intermediates should be useful for benchmarking computer-simulation studies of protein folding.

Acknowledgments

We thank Walter Englander for helpful comments and encouragement. We also thank two anonymous reviewers for their intelligent comments.

Author contributions: H.F. and Z.Z. performed research; H.F. and Y.B. analyzed data; Y.B. designed research; and Y.B. wrote the paper.

Abbreviations: RLS, rate-limiting step; Rd-apocyt b562, Rd-apocytochrome b562; PUF, partially unfolded form; NOE, nuclear Overhauser effect.

References

- 1.Kim, P. S. & Baldwin, R. L. (1982) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 51, 459–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim, P. S. & Baldwin, R. L. (1990) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 59, 631–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Englander, S. W. & Mayne, L. (1992) Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 21, 243–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matthews, C. R. (1993) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 62, 653–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ptitsyn, O. B. (1995) Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 5, 74–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Englander, S. W. (2000) Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 29, 213–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hughson, F. M., Wright, P. E. & Baldwin, R. L. (1990) Science 249, 1544–1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jeng, M. F. & Englander, S. W. (1991) J. Mol. Biol. 221, 1045–1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Debora, J. & Marqusee, S. (1996) Biochemistry 35, 11951–11958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jennings, P. A. & Wright, P. E. (1993) Science 262, 892–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eliezer, D., Yao, J., Dyson, H. J. & Wright, P. E. (1998) Nat. Struct. Biol. 5, 148–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oas, T. G. & Kim, P. S. (1988) Nature 336, 42–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peng, Z. Y. & Wu, L. C. (2000) Adv. Protein Chem. 53, 1–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bai, Y., Sosnick, T. R., Mayne, L. & Englander, S. W. (1995) Science 269, 192–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chamberlain, A. K., Handel, T. M. & Marqusee, S. (1996) Nat. Struct. Biol. 3, 782–787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fuentes, E. J. & Wand, A. J. (1998) Biochemistry 37, 9877–9883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Llinas, M., Gillespie, B., Dahlquist, F. W. & Marqusee, S. (1999) Nat. Struct. Biol. 6, 1072–1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chu, R. A., Pei, W. H., Takei, J. & Bai, Y. (2002) Biochemistry 41, 7998–8003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yan, S., Kennedy, S. D. & Koide, S. (2002) J. Mol. Biol. 323, 363–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vu, D., Feng, H. & Bai, Y. (2004) Biochemistry 42, 3346–3356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feng, H., Vu, N. D. & Bai, Y. (2005) J. Mol. Biol. 346, 345–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chu, R. A., Takei, J., Knowles, J. R., Andrykovitch, M., Pei, W., Kajava, A. V., Steinbach, P., Ji, X. & Bai, Y. (2002) J. Mol. Biol. 323, 253–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Feng, H., Vu, D. & Bai, Y. (2004) J. Mol. Biol. 343, 1477–1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Takei, J., Pei, W., Vu, D. & Bai, Y. (2002) Biochemistry 41, 12308–12312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feng, H., Takei, J., Lipsitz, R., Tjandra, N. & Bai, Y. (2003) Biochemistry 42, 12461–12465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vuister, G. W. & Bax, A. (1993) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 115, 7772–7777. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Delaglio, F., Grzesiek, S., Vuister, G., Zhu, G., Pfeifer, J. & Bax, A. (1995) J. Biomol. NMR 6, 277–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnson, B. A. & Blevins, R. A. (1994) J. Biomol. NMR 4, 603–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Laskowski, R. A., MacArthur, M. W., Moss, D. S. & Thornton, J. M. (1993) J. Appl. Cryst. 26, 283–291. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bai, Y., Milne, J. S., Mayne, L. & Englander, S. W. (1993) Proteins 17, 75–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Feng, H., Vu, D., Zhou, Z. & Bai, Y. (2004) Biochemistry 43, 14325–14331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xu, Y., Mayne, M. & Englander, S. W. (1998) Nat. Struct. Biol. 5, 774–778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bai, Y. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 477–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hoang, L., Bedard, S., Krishna, M. M. G., Lin, Y. & Englander, S. W. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 12173–12178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maity, H., Lim, W. K., Rumbley, J. N. & Englander, S. W. (2003) Protein Sci. 12, 153–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krishna, M. M. G., Lin, Y., Rumbley, J. N. & Englander, S. W. (2003) J. Mol. Biol. 331, 29–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maity, H., Maity, M. & Englander, S. W. (2004) J. Mol. Biol. 343, 223–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maity, H., Maity, M., Krishna, M. M. G., Mayne, L. & Englander, S. W. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Laurents, D. V., Bruix, M., Jamin, M. & Baldwin, R. L. (1998) J. Mol. Biol. 283, 669–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bai, Y. (2000) Protein Sci. 9, 194–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Heidary, D. K., O'Neill, J. C., Jr., Roy, M. & Jennings, P. A. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 5866–5870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Capaldi, A. P., Kleanthous, C. & Radford, S. E. (2002) Nat. Struct. Biol. 9, 209–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Spudich, G. M., Miller, E. J. & Marqusee, S. (2004) J. Mol. Biol. 335, 609–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Anfinsen, C. B. (1973) Science 181, 223–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Baldwin, R. L. (1997) Protein Sci. 6, 2031–2034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brandts, J. F., Halvorson, H. R. & Brennan, M. (1975) Biochemistry 14, 4953–4963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Creigton, T. E. (1997) Biol. Chem. 378, 731–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sosnick, T. R., Mayne, L., Hiller, R. & Englander, S. W. (1994) Nat. Struct. Biol. 1, 149–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Silow, M. & Oliveberg, M. (1997) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94, 6084–6086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nawrocki, J. P., Chu, R. A., Pannell, L. K. & Bai, Y. (1999) J. Mol. Biol. 293, 991–995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chu, R.-A., Takei, J., Barchi Jr., J. J. & Bai, Y. (1999) Biochemistry 38, 14119–14124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Krishna, M. M., Lin, Y. & Englander, S. W. (2004) J. Mol. Biol. 343, 1095–1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jackson, S. E. (1998) Folding Des. 3, R81–R91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Krantz, B. A., Mayne, L., Rumbley, J., Englander, S. W. & Sosnick, T. R. (2002) J. Mol. Biol. 324, 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Baldwin, R. L. (1994) Nature 369, 183–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wolynes, P. G., Onuchic, J. N. & Thirumalai, D. (1995) Science 267, 1619–1620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sosnick, T. R., Mayne, L. & Englander, S. W. (1996) Proteins 24, 413–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bai, Y. & Englander, S. W. (1996) Proteins 24, 145–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Feng, H. & Bai, Y. (2004) Proteins 56, 426–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]