Abstract

Background

The MTN-020/ASPIRE trial evaluated the safety and effectiveness of the dapivirine vaginal ring for prevention of HIV-1 infection among African women. A nested qualitative component was conducted at six of 15 study sites in Uganda, Malawi, Zimbabwe and South Africa to evaluate acceptability of and adherence to the ring.

Method

Qualitative study participants (n = 214) were interviewed with one of three modalities: single in-depth interview, up to three serial interviews or an exit Focus Group Discussion. Using semistructured guides administered in local languages, 280 interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed, translated, coded and analyzed.

Results

We identified three key findings: first, despite initial fears about the ring's appearance and potential side effects, participants grew to like it and developed a sense of ownership of the ring once they had used it. Second, uptake and sustained adherence challenges were generally overcome with staff and peer support. Participants developed gradual familiarity with ring use through trial progression, and most reported that it was easy to use and integrate into their lives. Using the ring in ASPIRE was akin to joining a team and contributing to a broader, communal good. Third, the actual or perceived dynamics of participants' male partner relationship(s) were the most consistently described influence (which ranged from positive to negative) on participants' acceptability and use of the ring.

Conclusion

It is critical that demonstration projects address challenges during the early adoption stages of ring diffusion to help achieve its potential public health impact as an effective, long-acting, female-initiated HIV prevention option addressing women's disproportionate HIV burden.

Keywords: Africa, dapivirine, HIV prevention, qualitative, vaginal ring, women

Background

Antiretroviral-based oral preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is highly effective for the prevention of HIV [1–7], and recent guidance from the WHO endorses its use. PrEP offers an effective method that women can use autonomously and discreetly to protect themselves – a long-awaited necessity as women bear a disproportionate burden of the global epidemic [8,9]. Importantly, low adherence prompted by a range of personal and contextual reasons [10–12] has resulted in failure to demonstrate effectiveness in three trials with women in sub-Saharan Africa [13–15]. Antiretrovirals in longer acting formulations could potentially overcome some PrEP adherence challenges.

The MTN-020/ASPIRE study was a randomized, placebo-controlled, phase III trial that evaluated the safety and effectiveness of a monthly dapivirine vaginal ring for HIV prevention in sub-Saharan African women [16]. ASPIRE reported a 27% reduction in HIV acquisition in intent-to-treat analyses, a 37% reduction amongst sites with acceptable adherence and 56% reduction in women aged over 21 years who had greater adherence than those aged 18–21 years [17]. Measurement of participants' acceptability of and adherence to new strategies like the dapivirine ring is essential for anticipating future uptake, sustained use and potential public health impact. A multisite qualitative component nested within ASPIRE explored how this female-initiated technology was viewed, used and integrated into the lives of study participants, thereby offering an important complement to the trial's effectiveness results.

Methods

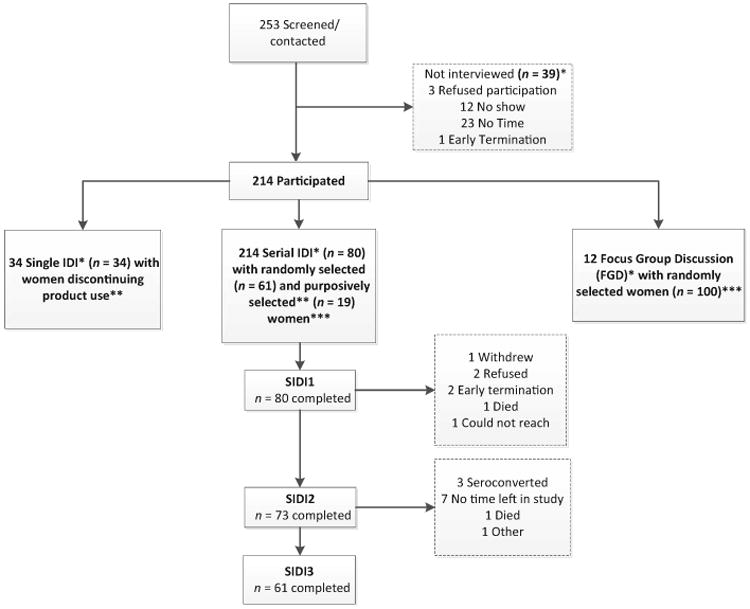

The ASPIRE trial design, population, procedures and primary findings have been previously published [16,17]. Briefly, 2629 women were enrolled at 15 sites in Malawi, South Africa, Uganda and Zimbabwe, and were followed for at least 12 months from August 2012 to June 2015. Women were randomized (1 : 1 ratio) to receive a silicone elastomer matrix ring (outer diameter of 56 mm, cross-sectional diameter of 7.7 mm) containing 25 mg of dapivirine or a placebo ring. The qualitative component was conducted from February 2013 to June 2015 at six study sites, representing each trial country and three metropolitan areas of South Africa. A total of 214 ASPIRE trial participants were recruited into one of three interview modalities: single in-depth interview (IDI) or serial IDI (SIDI), or focus group discussion (FGD), with 280 interviews completed (Fig. 1). This combination of interview approaches was used to provide a variety of complementary perspectives. SIDI, used with randomly selected women and ‘special cases' chosen by site staff for their unique adherence experiences, allowed for exploration of temporal trends while building rapport between interviewer and interviewee. Single IDI were used to gather data from those who permanently discontinued ring use, most ofwhom were seroconverters. FGDs among randomly selected participants allowed for exploration of group norms and attitudes about ring use, as a complement to individual experiences.

Fig. 1.

MTN-020 ASPIRE qualitative component: participant disposition. *IDI averaged 61 min, FGD were 159 min on average. **Reasons for single IDI women terminating product use early were (n = 34): 29, seroconversion to HIV-1; three, partner objection; two, pregnancy. Reasons for purposive selection in serial IDI (n — 19): four, lack of adherence; seven, overcoming obstacles; six, partner issues; one, trauma; one, vocal about others' non-use; two, exceptional adherer; one, chronic health issues. ***There were five seroconverters in the SIDI sample and one in the FGD sample.

Conceptual framework

The interview guides, codebook and the analysis strategy were informed by a conceptual model focused on PrEP and microbicides that offers a comprehensive framework to examine: (1) acceptability as a unique construct of its own discrete dimensions, distinct from adherence; (2) the relationship of acceptability to adherence and adherence components; and (3) the impact of broader contextual factors on both acceptability and/or adherence [18].

Procedures and analysis

A total of 161 participants were randomly selected for participation, and 53 were purposively selected to explore circumstances such as HIV seroconversion and adherence challenges. Institutional or Ethics Review Boards at each site approved the study, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Interviews followed semistructured guides administered by trained social scientists in local languages and were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim and translated into English. Interview guides focused on motivations to join the trial, HIV risk perception, trial experiences, attitudes of the participant and her male partner(s) toward the ring, effect of the ring on sex and use of the ring.

Transcripts were uploaded into NVivo11 qualitative software and coded using a codebook developed iteratively through a deductive and inductive process. Intercoder reliability of more than 90% for key codes was maintained among 10% of interviews. The coding team met weekly for ∼14 months to discuss emerging themes and issues, and consensus on the final interpretation of findings was achieved through in-person and telephonic discussions with all analysts and coauthors. The following dimensions of acceptability were evaluated: use attributes, product characteristics, drug formulation and dosing regimen, effect on sex, product-related norms and perceived partner acceptability [18]. Adherence to ring use was assessed by examining narratives related to initial uptake (initiation), consistent use and descriptions of ring expulsions; removals and use-related barriers and motivators. For this primary analysis, data from all qualitative participants were included, and findings represent dominant themes for the key outcomes of acceptability and adherence across subgroups. Demographic characteristics of the qualitative participants were summarized and statistically compared with other participants using Fischer's exact and Wilcoxon tests.

Results

Study population

Table 1 presents the characteristics of the sample in comparison with nonqualitative participants at the qualitative sites and at all ASPIRE sites. At baseline, qualitative study participants were on average 26 years of age (range 18–45), 45% were married and 73% had completed secondary school. The majority had disclosed trial participation (72%) or ring use (59%) to male partners. Qualitative participants were significantly (P < 0.05) younger and had fewer recent sex acts than their counterparts at qualitative sites. Qualitative participants were significantly different (P < 0.05) from others at all ASPIRE sites in regard to having less formal education and fewer reports of recent condom use. In the qualitative component, seroconverters were purposively recruited, which accounts for their disproportionately higher representation in this sample and may, in part, provide insight into some of the demographic and behavioral differences noted.

Table 1. Participant characteristicsa.

| All sites | (A) Qualitative (QUAL) sample | (B) Non-QUAL sample at QUAL sites | Difference [(A) vs. (B), Fisher's P] | (C) Non-QUAL sample at all sites | Difference [(A) vs. (C) Fisher's P] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants enrolled, N | 2629 | 214 | 907 | 2415 | ||

| Age, years x median (mean, min–max) | 26 (27.2, 18–45) | 26 (26.4, 18–42) | 27 (27.5, 18–45) | 0.012 | 26 (27.3, 18–45) | 0.126 |

| Currently married | 1074 (41%) | 96 (45%) | 423 (47%) | 0.648 | 978 (41%) | 0.218 |

| Highest level of education | ||||||

| No schooling | 23 (1%) | 5 (2%) | 8 (1%) | 0.114 | 18 (1%) | 0.002 |

| Primary school (partial and complete) | 381 (14%) | 45 (21%) | 191 (21%) | 336 (14%) | ||

| Secondary school (partial and complete) | 2070 (79%) | 156 (73%) | 646 (71%) | 1914 (79%) | ||

| Attended college or university | 155 (6%) | 8 (4%) | 62 (7%) | 147 (6%) | ||

| Had a primary sex partner during the past 3 months | 2616 (100%) | 213 (100%) | 904 (100%) | 0.572 | 2403 (100%) | 1.000 |

| Had any other sex partners in the past 3 months | 439 (17%) | 36 (17%) | 162 (18%) | 0.784 | 403 (17%) | 0.933 |

| Condom used in the last act of vaginal sex | 1501 (58%) | 101 (47%) | 444 (49%) | 0.205 | 1407 (58%) | 0.001 |

| Had anal sex in the past 3 months | 54 (2%) | 2 (1%) | 17 (2%) | 0.555 | 52 (2%) | 0.316 |

| Primary partner knows of participation in the trial | 1972 (75%) | 153 (72%) | 605 (67%) | 0.346 | 1819 (76%) | 0.277 |

| Primary partner knows has been asked to use ring | 1680 (64%) | 125 (59%) | 504 (56%) | 0.444 | 1555 (65%) | 0.171 |

| Primary partner HIV status | ||||||

| HIV positive | 35 (1%) | 4 (2%) | 14 (2%) | 0.133 | 31 (1%) | 0.321 |

| HIV negative | 1444 (55%) | 125 (59%) | 465 (51%) | 1319 (55%) | ||

| Participant does not know | 1137 (43%) | 84 (39%) | 425 (47%) | 1053 (44%) | ||

| Had same primary partner for last 3 months | 2538 (97%) | 206 (97%) | 859 (95%) | 0.367 | 2332 (97%) | 0.833 |

| Number of vaginal sex acts in the past 3 monthsb | 20 (26.5, 0–99) | 15.5 (23.2, 1–99) | 24 (26, 0–99) | 0.036 | 20 (26.8, 0–99) | 0.118 |

Background and demographic characteristics of participants were summarized in SAS (v.9; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina, USA), and statistically compared using Wilcoxon and Fishers exact tests.

Median (mean, min–max).

Acceptability

Ease of ring insertion and lack of interference during daily activities were salient themes. Fears of insertion combined with concerns that it would fall out or cause harm arose commonly, particularly early after starting ring use. These hypothetical fears were mostly overcome with actual experience and repeated use. In addition, reported experiences of physical discomfort wearing the ring, such as heaviness and pelvic pain, occurred mostly within the first 3 months of trial participation. Discomfort was generally described as short-lived and often attributed to improper insertion, which was remedied by reinserting or pushing the ring higher up into the vagina. Indeed, participants described that if the ring was properly positioned, it could not be felt (several described periodic self-checks to confirm it was still in situ), and many forgot that it was in place throughout the month. Many women described how the ring ‘became one with the body’ and integrated seamlessly into their daily activities and lives (Table 2, A). Women appreciated the monthly regimen and the ring's discretion – no one else knew it was being used. Overall participants endorsed the viewpoint that one could ‘set and forget’ [19] the ring (Table 2, B, D).

Table 2. Acceptability componentsa with illustrative quotations.

| (A) Use attributes: Ease and comfort of use, physical sensation in situ, discreetness/secrecy, side effects, ancillary benefits | I like them because once you wear it, you don't feel it, and nobody can suspect that you are wearing something. I like it because nothing changes regarding how we live as women [nobody can tell she is using the ring]. (SIDI1, Lilongwe) |

| (B) Delivery mechanism: Tablet, gel, ring, film, suppository, injectable | Because once we have worn the ring, it will be for once and for all [there is nothing more to be done apart from inserting the ring every month], we will have no inconveniences of carrying it around like we do with condoms. Even the use is different, because it is the man who puts on the condom; a woman does not put on the condom, and so nobody will know that you have the ring. (SIDI2, Lilongwe) |

| (C) Product characteristics: Color, size, smell, volume, consistency | When you seeing the ring for the first time you get shocked, I was too and almost quit because of the size of the ring. When you (are) using it you realise that it's easy to use, it's not a problem. I think what will happen is HIV will continue to spread even if the ring is found effective because people will look at the ring and think it's difficult to be used. I think there will be a need for classes to educate women about the ring …. It wasn't difficult, I got enough education before using it because I was really scared when I first saw it. I thought I was going to quit. But during education I learned that the ring was soft, I thought the ring was hard and painful. They showed that to insert the ring you need to twist it like 8 and when I tried it, it was easy and doable. (SIDI3, Durban) |

| (D) Dosing regimen: Daily, precoital, intermittent | Alright I, I just like that when you have inserted the ring you have inserted it [you are done] …. What's left is to come for the next visit. It's not like you will insert it every day or you will take it [orally] or what. It stays in there, I do not check it, I do not detach it, that is what I like on us-about the way it is used. (SIDI1, Harare) |

| (E) Effects on the sexualencounter: Lubrication, effect on sexual pleasure, timing of use | I noticed a difference before I had the ring and after I had the ring, I enjoy [sex] now, and my partner enjoys it. I don't have anything, I don't have a rash, I don't have a discharge, I am just the same, I don't have a problem with the ring … You see my vagina, I think it [the ring] tightened it [the vagina] and became small. Since I started using the ring, I can feel that when my partner and I are having sex, when he penetrates, I can feel the difference, because it [vagina] is tightened, you see. (SIDI1, Johannesburg) |

| (F) Partners attitude about product: Awareness, support of product use, approval/disapproval |

My husband and I accepted and I got support from him. You know some men might not want their partners to insert things in their vagina, but mine accepted it because he saw it was helping both of us. (SIDI2, Kampala) Yes he thought it was for family planning, then he said, ‘Please tell me (what this ring is).’ Then I said, ‘It does not concern you; it's about my life,’ and he said, ‘I will not give it to you.’ And he took it. (SIDI2, Kampala) |

| (G) Product associated norms: Stigma, community norms about product formulation | Some are saying that it is of some benefit because they will know whether the ring is effective in protecting women from STIs like HIV, while others say that there is no evidence [that the ring works], it is all a farce, that the drugs in the ring will cause problems, and that our systems will not function effectively in our bodies. (SIDI2, Lilongwe) |

As defined in Mensch et al. [18] conceptual model.

Narratives about the ring's physical characteristics centered on its size (overall diameter and thickness) and ‘hardness’ (rigidity and flexibility). Initial concerns and fears that the ring was too big or ‘scary’ were common. Less-frequent themes included fear that the ring would expand the vagina, cause pain, ‘rotting’ or scarring, be felt by the partner or disturb sex. Importantly, although many acknowledged initial apprehensions, few experienced difficulty with its size or sensation during actual ring use. The ring was most often reported as soft, flexible and comfortable after participants actually used it. The ‘rubber’-like material, smooth texture and the white color (that appeared clean and showed changes when used) were cited as positive attributes. Referencing their own ring-use trajectories, several participants suggested that clinicians should preemptively address negative first impressions of the ring in future studies or programs (Table 2, C).

Effect on sex and male partners

Women differed in their reports as to whether the ring was noticed during, or impacted, their sexual experience; however, it was occasionally reported to change the frequency, type or position associated with intercourse. Improved sexual pleasure was attributed to the ring in several different ways. As one participant explained, unlike the condom, the ring allowed for more natural sex ‘the way God intended’. Change in vaginal lubrication (both increases and decreases) or tightness that improved the feeling of sex was another salient theme (Table 2, E). Finally, some participants noted an improvement in overall libido and sexual pleasure, which was sometimes linked to reduced fears of HIVacquisition and perceptions that the ring offered protection.

Occasionally, women reported experiencing pain using the ring during sex, and some said that their partners complained they could feel it. However, several women across sites described informing their partners that they had removed it when they had not, and subsequently he stopped complaining. Women frequently expressed concerns about the possibility of male partners feeling the ring during sex – either because it would negatively impact his sexual experience or because he would become angry or abusive if he discovered she was using it (Table 2, F). Consequently, many participants preemptively disclosed ring use to partners for fear he would discover it during sex. Although less commonly noted, behavioral alterations to potentially avoid unwanted discovery of ring use (e.g. removing ring before sex, changing sex positions and forbidding fingers during foreplay) were reported. Nevertheless, most women agreed that disclosure of ring use to partners was important to prevent relationship problems such as suspicions about her behavior (e.g. promiscuity) or intentions (e.g. bewitchment) if ring was discovered, and to gain his support.

A small proportion of women reported keeping ring use secret throughout the study because they were afraid of an angry or suspicious reaction. Indeed, a small number of male partners had volatile initial reactions, which included some acts of physical violence and forced removals. By contrast, other nondisclosers didn't feel the need to inform partners, particularly if they were not married or if the relationship was new, casual or transactional. Women with supportive partners described how he encouraged and reminded them to use the ring and to attend study visits or expressed his appreciation that ASPIRE might help them or their children in the future. During SIDIs, several participants described changes in male partner attitudes, almost universally moving from being concerned or outright opposed toward greater acceptance and support of ring use. Few partners remained opposed or left the relationship.

Adherence

High adherence was a dominant theme: participants said that they had no trouble with the monthly use regimen and described being correct, consistent ring users. Individual counseling, education and site-specific group activities such as social gatherings, study on-site lab visits or male partner meetings were motivators not only for adherence, but also provided platforms through which women's concerns about the ring or study procedures were addressed and correct use was encouraged (Table 2, G). At group events, participants appreciated exchanging ring-use experiences with peers, making friends, having direct staff contact in less formally structured interactions and feeling valued by the researchers. Participants received feedback on estimates of their site's aggregate level of adherence relative to other sites, which reminded participants of the importance of adherence and fostered a sense of a shared goal. One participant likened this to feeling like she was part of a ‘team’ (Table 3, A).

Table 3.

Illustrative quotes about product use adherence.

| Theme | Illustrative quote |

|---|---|

| (A) Team effort |

Ah we just felt happy because what we expected-, to be told that ‘as a group’ we were doing well like a soccer ‘team’. Just to be told that all of us were doing well was pleasant than to be given the ‘result’ that some were using while others were not. Ah this pulls back progress [she meant if participants were not using the ring the study will not progress in terms of achieving its study objectives] Ok so can we say those ‘feedbacks' influenced participants' use of the ring in any way here at (clinic site)? Yes because there was going to be a few who would not use the ring but if they heard that all of you are doing well in [ring use] then they would also use. (SIDI3, Harare) |

| (B) Pride; effect of use on future generations | It is also something to be proud of when you will tell your relatives even after 50 years that, ‘Ah do you know that this ring being used we once-, it is us who made it to be approved for use to prevent HIV.’ (SIDI3, Harare) |

| (C) Empowerment | No, I told him to take the ring as the condom. I said: ‘Because you do not want the condom, this is now our condom, just ignore it, it's inside my body and it's mine. Because you don't want the condom so pretend as if this is my condom because you don't want to wear a condom I am wearing mine.’ We never had problems about it and we never spoke about it again. (SIDI2, Durban) |

| (D) Involuntary expulsions | No it never got out, I always placed it well, it never got out not when I am having sex, not when I am partying, not when I am urinating, not when I am bathing, it stayed there (in the vagina). (Single IDI, Johannesburg) |

| (E) Removal for sex | When my husband is in the mood for sex, then it's time for sex, which isn't the case with the other man. The other man will spend time caressing me (foreplay), which isn't the case with my husband. That's why I would remove it, fearing that he might feel it. I thought he’d quarrel about the ring. (SIDI1, Kampala) |

| (F) Removals for menses | During my first months [of using the ring] I used to feel uncomfortable, like when I was on my periods because I used tampons so I would feel uncomfortable when I was pulling out a used tampon. So during my periods I used to remove it maybe for the first 2 months but then I came here to the clinic and I explained to the [study] doctors and they told me, ‘No its fine’. From there onwards it has been like that. (SIDI3, Johannesburg) |

| (G) Others (young women) not using ring | I think, what I really wanted you to say, ever since I came here at (clinic site), you can see when people are sitting here and we would be chatting … Yes, what I have noticed is that, most of the younger people, let me say those who are younger than me, they are not using the ring because they are saying it's just for the money; others that it's just a waste of time; they take it off when they get home and put it back again the next week. And you cannot just decide to advise someone, they might humiliate you in front of others, so you decide to rather keep your mouth shut. I wish that there could be something done about this, because most of them are young; I think those who do that are less than 30 years in age. Because when you are chatting with the matured ones, you can see that yes, they are using the ring, but the young ones are not using it. Once a person gets home, they take it off and put it back during the week they are coming to (clinic site). So that is something that they need to look at. (SIDI1, Cape Town) |

Among those who openly admitted to ring nonuse, this behavior was often attributed to only a small number of isolated (involuntary) ring expulsion or (voluntary) removal events, often occurring only within the first couple of months of study participation. Most women described that the ring would not fall out, irrespective of their activities (Table 3, D), and several commented that it was so ‘impossible’ for it to fall out that those who reported this were ‘lying’. The small number of ring expulsions reported were most commonly experienced as a result of sex or during use of the toilet (e.g. during bowel movements and/or squatting over a pit latrine). Ring expulsions during menses were also described, but this was not a dominant theme.

Instances of voluntarily removals were most commonly associated with male partners, menses and perceived side effects. Often women described removing the ring only one or two times at the start of the study, but seldom after. Male partner-related removals resulted because he wanted to see it, asked her to stop using it, ‘discovered’ the ring during foreplay or intercourse and removed it or because she removed it before sex so that he would not find or feel it (Table 3, E). Participants described removing and rinsing or cleaning the ring due to menses, because they felt unclean or were embarrassed to return a dirty ring to the clinic (Table 3, F). Removals were also reported in association to perceived side effects (e.g. vaginal discharge, itching, headache and vaginal odor), and ring was removed to evaluate whether symptoms resolved. Of note, the majority (75%) of younger participants aged 18–21 years reported never removing the ring for any reason during the study, whereas about half of the women aged over 21 years described this behavior.

Some women described longer nonadherent periods (e.g. several months) at the start of the study, as a result of peer influence and fear of side effects, before they received counseling and encouragement from staff. More common than personal disclosure, participants described how ‘other women’ would not wear the ring at home and remove it until 2 days before their next visit. This caused frustration for adherent participants that their own efforts might be wasted if the study was not able to achieve its objectives and measure an effect. ‘Other women’ removed their rings because their male partners didn't know about the study or because they were participating only for the benefits (e.g. free healthcare and reimbursements) and didn't want to use the ring. Indeed, one participant reported that staff made a ‘mistake’ teaching women how to remove the ring themselves. Another participant overheard young people chatting in the waiting room about removing the ring when they got home because they felt that its use was a waste of time or they only wanted the money, but she was afraid to speak up to them (Table 3, G). During the study, nurses conducted visual ring inspections to guide counseling, and at several sites women described immersion of rings in tea and coffee for discoloration, so it would appear used.

Many adherence-related narratives reflected a good understanding of how participant's individual ring use translated more broadly to study objectives and HIV prevention for other women in their communities, future generations and even globally (Table 3, B). These women spoke of the bigger picture as a source of motivation and pride for consistent ring use, and this was often linked to discourses of empowerment that study participation both fostered and reinforced through education, counseling and frequent health checks. For some, ring use and the study offered confidence and a sense of previously unrealized ownership over their own HIV protection. A Durban participant described telling her partner ‘Because you do not want the condom, this is now our condom, just ignore it, it's inside my body and it's mine’, articulating the theme of women's appreciation for a method they could control (for full quote, refer to Table 3, C).

Discussion

The qualitative component of the ASPIRE trial gathered extensive in-depth information from a diverse range of settings about women's attitudes toward and experiences with using an investigational ring in the context of HIV prevention. Our results highlight three key findings: first, despite initial fears about the ring's appearance and potential side effects, participants grew to like it and developed a sense of ownership of the ring once they had experience using it. Second, uptake and sustained adherence challenges were generally overcome with staff and peer support. Participants developed gradual familiarity with ring use through trial progression, and most reported that it was easy to use and integrate into their lives. Using the ring in ASPIRE was akin to joining a team and contributing to a broader, communal good. Third, the actual or perceived dynamics of participants' male partner relationship(s) were the most consistently described influence (which ranged from positive to negative) on participants' acceptability and use of the ring.

The results corroborate previous ring research, in which participants have similarly reported initial fears, followed by increased comfort and overall acceptability of physical and use-associated attributes of the ring [20–22]. Indeed, women in other female-initiated HIV prevention trials in sub-Saharan Africa have consistently reported favorable attitudes toward investigational products [21–27]. However, although qualitative research with participants in these trials has highlighted experiential complaints with product characteristics (e.g. gel leakage) or dosing regimen (e.g. burden of daily use), such accounts were rarely noted with the ring. The residual ring and plasma dapivirine data in ASPIRE suggested higher adherence with the ring than previously measured with other dosing regimens [13,17,28]. Although the relationship between acceptability and adherence is not straightforward (women may use a product without liking it and vice versa), these biomarker data imply that reported acceptability might have been informed by more experiences of actual use than in other studies.

The circumstances and reasons for ring removals and expulsions described here are remarkably similar to previous studies of ring use in these research settings [20,22]. Similarly, across sites, participants reported patterns of poor execution (e.g. ‘white-coat’ effect of removing ring after visit and reinserting immediately before next) and reasons for nonadherence that have been reported elsewhere such as fear of side effects and interest only in trial benefits [10,11,29,30]. However, unlike other studies, adherence in ASPIRE – although imperfect – was sufficient to demonstrate protection despite nonuniversal use [17].

Consistent with modeling from the main ASPIRE analysis depicting lower adherence during the first several months of trial participation, qualitative participants reported ring removals at the early stages of the study for a variety of reasons (e.g. unwanted partner discovery and fear of or discomfort with the device or insertion) [17].

ASPIRE provided individual-based counseling and group-based peer support that seemingly had an important influence on ring adoption. In trial communities, the vaginal ring is a novel technology, and the importance of peer influence observed here (particularly during the early assessment and evaluation stages of product uptake) is consistent with diffusion of innovations theory [31,32]. The importance of peers in adoption of the contraceptive NuvaRing (N.V. Organon, Oss, The Netherlands) was a key finding in a US study among adolescent girls [33]. By contrast, at the start of ASPIRE, and in other PrEP trials at the same African research sites, negative peer influence – for example rumors and widespread reports of nonadherence in waiting rooms – negatively affected adherence [10,34]. Researchers' efforts to provide individual and peer support may be critical investments of time and energy that ultimately serve multiple overlapping objectives: addressing physical and emotional barriers to product use, educating participants about the research process and their role in a global HIV prevention effort, fostering respect and trust among researchers and participants and ultimately supporting adherence and enhancing product effectiveness.

Throughout participant's narratives of ring acceptability and use, consideration of male partners' attitudes toward, or awareness of, the ring was a pervasive theme. Given that the ring is designed for use during heterosexual vaginal intercourse, and particularly in a traditionally patriarchal context, it is logical that the male half of the dyad would be influential, as has been described elsewhere [20,35–38]. Microbicides were initially envisioned as tools for women's empowerment, but as has been repeatedly shown, ‘empowerment’ is a complex, multifaceted and culturally prescribed concept [39]. Despite the strong influence of male partners reported here, empowerment related to the ring was observed in several different ways including consistent use in response to partners not wearing condoms and altruistic pride for contributing to women's HIV prevention.

Qualitative methods are well suited to both explore and explain the depth, nuance and complexity of the acceptability and use of novel technologies like the ring and offer important insights to complement ASPIRE trial results [30,40]. Nevertheless, there are several limitations that should be considered in interpreting these findings. First, social desirability bias likely inflated participants' accounts of liking the ring and downplayed their experiences of nonadherence. For example, subgroup analyses of residual ring data suggest that the majority of women inconsistently used the ring throughout their trial duration [41], yet narratives of nonadherence here were often limited to a few isolated events or short durations of time at the start of the study. This bias seemed to be more pronounced among younger women, the majority of whom described never removing the ring. In addition, qualitative data analysis is inherently interpretive. We implemented a stringent transcription and translation quality control process, conducted regular intercoder reliability checks and interpretation meetings and vetted findings across analysts, interviewers and investigators at all sites to maximize consensus.

The findings suggest several areas for further research. The discrepancy between high reported acceptability noted here and suboptimal adherence reported in the trial supports the need for continued research into, and attention toward, the multilevel contextual factors that inhibit consistent ring use. As the ring moves forward in open-label extension studies, it will be important to evaluate how male partners' attitudes and behaviors (or women's perceptions thereof) continue to influence acceptability and adherence, how ring disclosure changes and to identify feasible and effective strategies to increase women's agency to safely and consistently use methods that will reduce their HIV risk.

In conclusion, the dapivirine ring is an effective, long-acting female-initiated prevention method that is easy to use discretely and independently, and thus has important potential to reduce women's disproportionate burden of HIV. In the context of HIV prevention, and in Africa, the vaginal ring is a new innovation, and uptake was correspondingly challenging for many women. Increased experience, counseling and camaraderie were essential for getting comfortable with its appearance and use during daily life and sex. Given the ring's potential public health impact, it is critical that demonstration projects address challenges during the early adoption stages of ring diffusion and thereby help to realize its potential as an effective, mainstream HIV prevention option for women.

Acknowledgments

The MTN-020/ASPIRE study was designed and implemented by the Microbicide Trials Network (MTN). The MTN is funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (UM1AI068633, UM1AI068615 and UM1AI106707), with cofunding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the National Institute of Mental Health, all components of the US National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The vaginal rings used in this study were supplied by the International Partnership for Microbicides.

Role of authors: E.T.M., A.V.: were involved in the conception and design of the study, and data analysis and interpretation for the work. E.T.M. drafted the work. M.C., K.R., K.W., M.A., L.-G.B., J.E. were involved in collection and interpretation of the data; A.J.M. was involved in study implementation and interpretation of the data; A.K., N.L. were involved in the data management, analysis and interpretation of the data; C.I.G., L.S. were involved in the conception of the work; T.P., J.M.B.: were involved in the conception and design of the study and interpretation of the data; All authors reviewed and revised the article critically, approved the version to be published and agreed to be accountable for the work.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Baeten JM, Donnell D, Ndase P, Mugo NR, Campbell JD, Wangisi J, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention in heterosexual men and women. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:399–410. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1108524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL, McMahan V, Liu AY, Vargas L, et al. Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2587–2599. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grant RM, Anderson PL, McMahan V, Liu A, Amico KR, Mehrotra M, et al. Uptake of preexposure prophylaxis, sexual practices, and HIV incidence in men and transgender women who have sex with men: a cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14:820–829. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70847-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO. Policy brief: WHO expands its recommendation on the use of oral PrEP. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choopanya K, Martin M, Suntharasamai P, Sangkum U, Mock PA, Leethochawalit M, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV infection in injecting drug users in Bangkok, Thailand (the Bangkok Tenofovir Study): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2013;381:2083–2090. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61127-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bekker LG, Grant R, Hughes J, Amico R, Roux S, Hendrix C, et al. Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections. Seattle, WA: 2015. HPTN 067/ADAPT Cape Town: a comparison of daily and nondaily PrEP dosing in African Women. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCormack S, Dunn DT, Desai M, Dolling DI, Gafos M, Gilson R, et al. Preexposure prophylaxis to prevent the acquisition of HIV-1 infection (PROUD): effectiveness results from the pilot phase of a pragmatic open-label randomised trial. Lancet. 2016;387:53–60. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00056-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.UNAIDS. UNAIDS reports on the global AIDS epidemic. [Accessed 10 November 2016];2010 http://www.unaids.org/globalreport/default.htm.

- 9.UNAIDS. 2013 UNAIDS report on the epidemic. Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 10.van der Straten A, Montgomery ET, Musara P, Etima J, Naidoo S, Laborde N, et al. Disclosure of pharmacokinetic drug results to understand nonadherence. AIDS. 2015;29:2161–2171. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Corneli AL, Deese J, Wang M, Taylor D, Ahmed K, Agot K, et al. FEM-PrEP: adherence patterns and factors associated with adherence to a daily oral study product for preexposure prophylaxis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;66:324–331. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Corneli AL, McKenna K, Headley J, Ahmed K, Odhiambo J, Skhosana J, et al. A descriptive analysis of perceptions of HIV risk and worry about acquiring HIV among FEM-PrEP participants who seroconverted in Bondo, Kenya, and Pretoria, South Africa. J Int AIDS Soc. 2014;17 ((3 Suppl 2)):19152. doi: 10.7448/IAS.17.3.19152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marrazzo JM, Ramjee G, Richardson BA, Gomez K, Mgodi N, Nair G, et al. Tenofovir-based preexposure prophylaxis for HIV infection among African women. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:509–518. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1402269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Damme L, Govinden R, Mirembe FM, Gue´dou F, Solomon S, Becker ML, et al. Lack of effectiveness of cellulose sulfate gel for the prevention of vaginal HIV transmission. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:463–472. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0707957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rees H, Delany-Morelwe S, Lombard C. Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections. Seattle, WA: 2015. FACTS 001 phase III trial of pericoital tenofovir 1% gel for HIV prevention in women. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Palanee-Phillips T, Schwartz K, Brown ER, Govender V, Mgodi N, Kiweewa FM, et al. Characteristics of women enrolled into a randomized clinical trial of dapivirine vaginal ring for HIV-1 prevention. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0128857. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0128857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baeten JM, Palanee-Phillips T, Brown ER, Schwartz K, Soto-Torres LE, Govender V, et al. Use of a vaginal ring containing dapivirine for HIV-1 prevention in women. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:2121–2132. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1506110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mensch BS, van der Straten A, Katzen LL. Acceptability in microbicide and PrEP trials: current status and a reconceptualization. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2012;7:534–541. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e3283590632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van den Berg JJ, Rosen RK, Bregman DE, Thompson LA, Jensen KM, Kiser PF, et al. ‘Set it and Forget it’: women's perceptions and opinions of long-acting topical vaginal gels. AIDS Behav. 2014;18:862–870. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0652-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Montgomery ET, van der Straten A, Cheng H, Wegner L, Masenga G, von Mollendorf C, et al. Vaginal ring adherence in sub-Saharan Africa: expulsion, removal, and perfect use. AIDS Behav. 2012;7:1787–1798. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0248-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van der Straten A, Montgomery E, Cheng H, Wegner L, Masenga G, von Mollendorf C, et al. High acceptability of a vaginal ring intended as a microbicide delivery method for HIV prevention in African women. AIDS Behav. 2012;16:1775–1786. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0215-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nel A, Bekker LG, Bukusi E, Hellstro¨m E, Kotze P, Louw C, et al. Safety, acceptability and adherence of dapivirine vaginal ring in a microbicide clinical trial conducted in multiple countries in sub-Saharan Africa. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0147743. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0147743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Montgomery ET, Woodsong C, Musara P, Cheng H, Chipato T, Moench TR, et al. An acceptability and safety study of the Duet cervical barrier and gel delivery system in Zimbabwe. J Int AIDS Soc. 2010;13:30. doi: 10.1186/1758-2652-13-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Minnis AM, Gandham S, Richardson BA, Guddera V, Chen BA, Salata R, et al. Adherence and acceptability in MTN 001: a randomized cross-over trial of daily oral and topical tenofovir for HIV prevention in women. AIDS Behav. 2013;17:737–747. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0333-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nel AM, Mitchnick LB, Risha P, Muungo LT, Norick PM. Acceptability of vaginal film, soft-gel capsule, and tablet as potential microbicide delivery methods among African women. J Womens Health. 2011;20:1207–1214. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2010.2476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Montgomery ET, Cheng H, van der Straten A, Chidanyika AC, Lince N, Blanchard K, et al. Acceptability and use of the diaphragm and Replens lubricant gel for HIV prevention in Southern Africa. AIDS Behav. 2010;14:629–638. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9609-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Montgomery CM, Gafos M, Lees S, Morar NS, Mweemba O, Ssali A, et al. Reframing microbicide acceptability: findings from the MDP301 trial. Cult Health Sex. 2010;12:649–662. doi: 10.1080/13691051003736261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Van Damme L, Corneli A, Ahmed K, Agot K, Lombaard J, Kapiga S, et al. Preexposure prophylaxis for HIV infection among African women. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:411–422. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1202614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Corneli A, Perry B, McKenna K, Agot K, Ahmed K, Taylor J, et al. Participants' explanations for nonadherence in the FEM-PrEP clinical trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;71:452–461. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van der Straten A, Stadler J, Montgomery E, Hartmann M, Magazi B, Mathebula F, et al. Women's experiences with oral and vaginal pre-exposure prophylaxis: the VOICE-C qualitative study in Johannesburg, South Africa. PLoS One. 2014;9:e89118. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kincaid DL. Social networks, ideation, and contraceptive behavior in Bangladesh: a longitudinal analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2000;50:215–231. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00276-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rogers E. Diffusion of innovations. 5th. New York: The Free Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Epstein LB, Sokal-Gutierrez K, Ivey SL, Raine T, Auerswald C. Adolescent experiences with the vaginal ring. J Adolesc Health. 2008;43:64–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Musara P, Munaiwa O, Mahaka I, Mgodi Nyaradzo M, Hartmann M, Levy L, et al. The effect of presentation of pharma-cokinetic (PK) drug results on self-reported study product adherence among VOICE participants in Zimbabwe. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2014;30:A42–A50. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Montgomery CM, Lees S, Stadler J, Morar NS, Ssali A, Mwanza B, et al. The role of partnership dynamics in determining the acceptability of condoms and microbicides. AIDS Care. 2008;20:733–740. doi: 10.1080/09540120701693974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Montgomery ET, van der Straten A, Chidanyika A, Chipato T, Jaffar S, Padian N. The importance of male partner involvement for women's acceptability and adherence to female-initiated HIV prevention methods in Zimbabwe. AIDS Behav. 2011;15:959–969. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9806-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Montgomery ET, van der Straten A, Stadler J, Hartmann M, Magazi B, Mathebula F, et al. Male partner influence on women's HIV prevention trial participation and use of pre-exposure prophylaxis: the importance of ‘understanding’. AIDS Behav. 2015;19:784–793. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0950-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lanham M, Wilcher R, Montgomery ET, Pool R, Schuler S, Lenzi R, Friedland B. Engaging male partners in women's microbicide use: evidence from clinical trials and implications for future research and microbicide introduction. J Int AIDS Soc. 2014;17 ((3 Suppl 2)):19159. doi: 10.7448/IAS.17.3.19159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Montgomery CM. Making prevention public: the co-production of gender and technology in HIV prevention research. Soc Stud Sci. 2012;42:922–944. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pool R, Montgomery CM, Morar NS, Mweemba O, Ssali A, Gafos M, et al. Assessing the accuracy of adherence and sexual behaviour data in the MDP301 vaginal microbicides trial using a mixed methods and triangulation model. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11632. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brown E, Palanee-Philips T, Marzinke M, Hendrix C, Dezutti C, Soto-Torres L, Baeten J. Residual dapivirine ring levels indicate higher adherence to vaginal ring is associated with HIV-1 protection. Durban: IAS; 2016. [Google Scholar]