Abstract

Rational and Objectives

This study aims to evaluate the diagnostic utility of breast imaging using transmission ultrasound. We present readers’ accuracy in determining whether a breast lesion is a cyst versus a solid using transmission ultrasound as an adjunct to mammography.

Materials and Methods

This retrospective multi-reader, multi-case receiver operating characteristic study included 37 lesions seen on mammography and transmission ultrasound. Cyst cases were confirmed as cysts using their appearance on handheld ultrasound. Solid cases were confirmed as solids with pathology results. Fourteen readers performed blinded, randomized reads with mammog-raphy + quantitative transmission scan images, assigning both a confidence score (0–100) and a binary classification of cyst or solid. A 95% percentile bootstrap confidence interval (CI) was computed for the readers’ mean receiver operating characteristic area, sensitivity, and specificity.

Results

Using the readers’ binary classification of cyst or solid lesions, the mean sensitivity and specificity were 0.933 [95% CI: 0.837, 0.995] and 0.858 [95% CI: 0.701, 0.985], respectively. When the readers’ confidence scores were used to distinguish a cyst versus solid, the mean receiver operating characteristic area was 0.920 [95% CI: 0.827, 0.985].

Conclusions

Transmission ultrasound can provide an accurate assessment of a cyst versus a solid lesion in the breast. Prospective clinical trials will further delineate the role of transmission ultrasound as an adjunct to mammography to increase specificity in breast evaluation.

Keywords: Transmission ultrasound, breast, cyst, mass

INTRODUCTION

X-Ray mammography (XRM) has been used for over 40 years as the primary breast cancer screening modality in the United States. It is a technology that sees shadows and calcifications as a way of determining whether there is an abnormality in the breast. Over the many years of use, mammography has shown mixed results regarding imaging performance and accuracy of diagnosis. Issues of low sensitivity, particularly when used in the dense breast evaluation, and the use of ionizing radiation create significant concerns for physicians and patients. Although early reviews of digital breast tomosynthesis have shown improved sensitivity and decreased noncancer recall rates, digital breast tomosynthesis still involves ionizing radiation, is associated with uncomfortable breast compression, and images the breast in a compressed state, instead of its natural form. The specific-ity of mammography, even when combined with ultrasound, whether handheld or automated methods, results in many false-positives, leading to costly procedures and significant patient anxiety. More than 1.2 million false-positive biopsies are performed in the United States annually (1), and in another recent study $4 billion are spent annually on false-positive mam-mograms in the United States (2).

To improve specificity and decrease the large number of false-positive biopsies, transmission ultrasound has been developed by QT Ultrasound Labs (3–5). Performance features show improved spatial and contrast resolution (4). Transmission ultrasound images breast microanatomy (6) and aims to provide tissue characterization with a unique combination of transmission and reflection B-mode ultrasound images (7). Figures 1 and 2 represent two cases, a cyst and a malignant solid, with transmission images (upper image with top three panels showing coronal, axial, and sagittal views) and reflec-tion B-images (lower image showing top three panels showing coronal, axial, and sagittal views). Whether diagnosing early breast cancer, or confirming that a patient’s exam is normal, high sensitivity and specificity are both important performance measures for providing quality breast care.

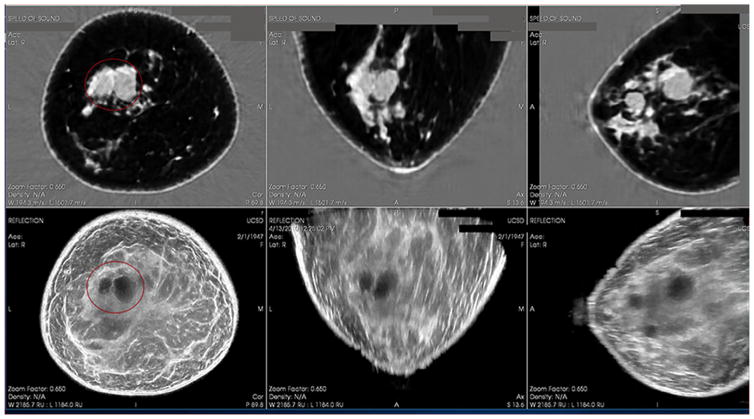

Figure 1.

Cystic mass as seen on QT Ultrasound. Top 3 panels show the Speed of Sound (Transmission) image in 3 planes and the bottom 3 panels show the Reflection images in 3 planes.

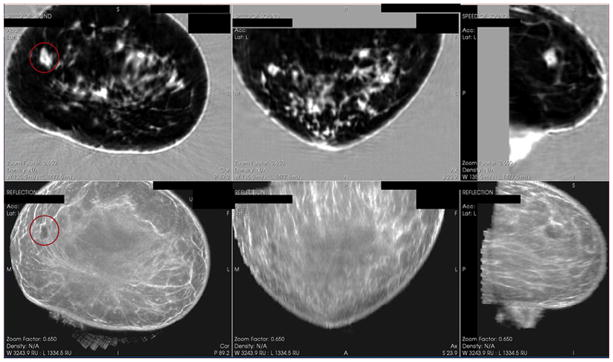

Figure 2.

Solid mass as seen on QT Ultrasound. Top 3 panels show the Speed of Sound (Transmission) image in 3 planes and the bottom 3 panels show the Reflection images in 3 planes.

Current Standard of Care

When XRM identifies a lesion(s), or when a patient has a symptom(s) (eg, palpable lump, focal pain, or nipple discharge), handheld ultrasound (HHUS) is used as an adjunct to XRM for further evaluation. Additionally, HHUS or automated ultrasound may also be used for secondary screening in patients with a normal, dense mammogram to further evaluate the breast and improve upon the lower sensitivity for breast cancer detection seen with XRM alone in this subset of patients. When ultrasound is used to evaluate dense breasts, however, Gerson and Berg (8) reported the “risks of additional testing” and found that “two to six in 100 women who undergo screening sonography will require a breast aspiration or biopsy because of the sonogram” (8). Additionally, “in as many as one out of 10 women, additional short-interval follow-up sonography (usually in 6 months) may be recommended because of the screening sonogram” (8). In Daly et al., only 1 out of 243 lesions (complicated cysts) was found to be malignant (9). These studies highlight the problem that using adjunctive ultrasound in these situations identifies more benign lesions, without providing the specificity required to prevent these benign lesions from requiring additional imaging and procedures. Because cysts are the most common breast lesion with estimated frequency between 50% and 90% (10,11) and because they are benign, with only a 0.23% risk of malignancy for complicated cysts (11), no further work-up is needed (10–12). Berg et al. also indicated that false-positives will be substantially increased with the addition of screening ultrasound (13). To avoid the additional imaging work-up, follow-up, and unnecessary procedures, as well as the significant anxiety and psychological burden experienced by the patient (14,15), transmission ultrasound of the breast aims to improve specificity and prevent women from additional work-up and procedures while maintaining a high sensitivity for the diagnosis of early breast cancer.

Transmission Ultrasound

Transmission ultrasound is an emerging technology that is an automated, standardized alternative to conventional HHUS in breast imaging. In addition to reflection B-mode imaging, transmission data provide speed of sound information regarding the stiffness of breast tissue or lesions. Advances in algorithms and computing have made it possible to develop and determine the clinical relevance of transmission ultrasound (3–5).

The aim of this study is to investigate and report the diagnostic accuracy of transmission ultrasound using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis. We present the readers’ diagnostic accuracy in determining a cyst versus a solid lesion with XRM + quantitative transmission (QT) scan images, including the speed of sound number recorded by the readers.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Oversight

The XRM and transmission ultrasound images were collected from 2006 to 2010 at five institutions (University of California San Diego, San Diego, CA; the Orange County Breast Care and Imaging Center, Orange, CA; McKay Dee Hospital, Ogden, UT; the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN; and University of Freiburg, Freiburg, Germany). The use of these historical images in this retrospective multi-reader, multi-case (MRMC) ROC study was deemed exempt by the Western Institutional Review Board’s Affairs Department under the exemption criteria of 45 Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) §46.101(b)(4). The demographic composition included a cross section of women at the participating facilities who were of diagnostic age. The mean age was 54 years for the 27 subjects included in the reading session with known dates of birth.

Transmission Ultrasound Imaging

The QT Ultrasound Breast Scanner produces reflection B-mode and transmission images in three dimensions: coronal, axial, and sagittal views. The readers were trained in using the region of interest tool to determine speed of sound for lesions to aid in determining whether the lesion is cyst or solid.

Retrospective MRMC ROC Study Design and Execution

Fourteen board-certified/board-eligible diagnostic radiology readers participated in this study. Thirteen readers had Mammography Quality Standards Act (MQSA) certifica-tion, and one radiology reader was an interventional radiology fellow in training and not MQSA-certified. One independent board-certified, MQSA-certified radiologist participated as the independent reviewer. All readers completed the QT Ultrasound Reader Training program and passed the qualifying written exam. The independent reviewer reviewed the cases and confirmed eligibility for the reader study.

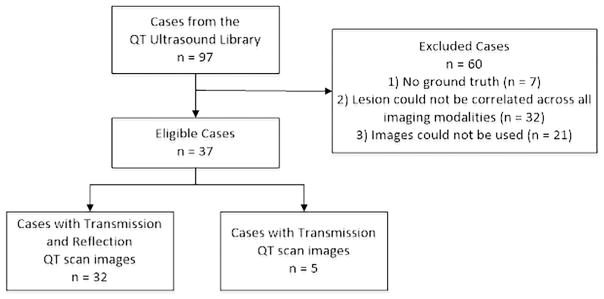

Ninety-seven cases from the QT Ultrasound imaging library were reviewed by the independent reviewer for inclusion in the reader session. Eligible cases were required to have a mam-mographic lesion(s) seen in at least one view on digital XRM confirmed by HHUS. At least two digital XRM views (craniocaudal and mediolateral oblique), as well as any additional XRM views, were included. At least one HHUS view was included. The entire QT scan in Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine format was provided. Five cases included had transmission images only as part of the QT scan as they were historical cases that did not have raw reflection B-mode data (Fig 3).

Figure 3.

Case selection summary.

Ground truth pathology was available for all solid lesions, and the standard appearance of cysts on HHUS was used as ground truth for all cysts. Because cysts are not typically aspirated as a standard of care without symptoms or other imaging signs of concern, the appearance on HHUS was used as the ground truth. Thirty-seven cases (20 cysts and 17 solids) met the eligibility criteria and were included in the reader session. The independent reviewer annotated the target lesions on imaging.

The 14 readers performed blinded, randomized review of the eligible cases. There was one reading session lasting 2 days. A reader reviewed up to 37 cases per day. The readers examined the XRM and QT scan images to determine whether the target lesion was a cyst or a solid based on imaging and speed of sound for which readers were trained. Two cases from one subject were eliminated from the analysis due to the readers’ confusion on which lesions were annotated as target lesions. One reader was omitted from analysis due to incorrect use of the Confidence Score Scale and interrogation of nontarget lesions.

Table 1 provides probabilities for a cyst or solid lesion determination based upon the speed of sound values. This table was derived from a prior feasibility study analyzing speed of sound values of cyst and solid lesions (Klock J, unpublished data) and was provided to the readers as a guide to determine whether the lesion is cyst or solid. Table 1 was included in the case report form provided to the readers.

TABLE 1.

Estimated Probability of a Cyst/Solid Lesion as a Function of the Speed of Sound Value From a Prior Internal Feasibility Study

| Speed of Sound Value (m/s) | Probability That the Lesion Is a Cyst (%) | Probability That the Lesion Is a Solid (%) |

|---|---|---|

| ≤1540 | 0.91–0.98 | 0.02–0.09 |

| 1541–1560 | 0.89–0.98 | 0.02–0.11 |

| 1561–1570 | 0.23–0.64 | 0.36–0.77 |

| 1571–1580 | 0.01–0.06 | 0.94–0.99 |

| >1580 | <0.01 | >0.99 |

Probabilities are applicable to populations with a prevalence rate between 0.40 and 0.80.

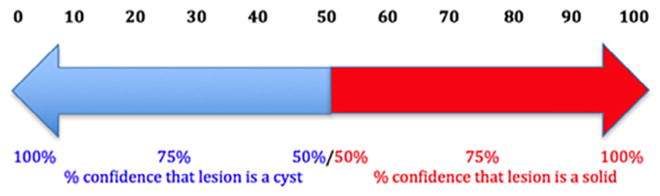

The readers examined the target lesion for the speed of sound on the QT scan exam. Then, they assigned a confidence score of 0–100, where 0 indicates 0% confidence that the lesion is a solid (ie, 100% confidence that the lesion is a cyst) and 100 implies 100% confidence that the lesion is a solid (ie, 0% con-fidence that the lesion is a cyst) (Fig 4). Finally, they gave a binary (cyst vs solid) decision for each lesion. The data were recorded on a case report form for each case set.

Figure 4.

Confidence Score Scale of cyst to solid, where 0 indicates absolute certainty of a lesion being a cyst and 100 indicates absolute certainty that a lesion is a solid.

Statistical Analysis for the MRMC ROC Study

With 37 cases, we determined that a study with 14 readers would allow us to estimate the readers’ mean ROC area to within ±0.05.

Each reader’s ROC area with the XRM + QT scan was estimated from the 0–100 confidence scores using nonpara-metric methods for clustered data (16). Similarly, for each reader, the sensitivity (proportion of solids correctly classified as solid) and specificity (proportion of cysts correctly classified as cysts) were estimated from the forced binary decision (cyst or solid) data. A 95% percentile bootstrap confidence interval (CI) was computed for the readers’ mean area under the ROC curve, sensitivity, and specificity.

RESULTS

Figure 1 shows a transmission and reflection ultrasound image of a large cyst in a breast that is typical of the images used for the study. Figure 2 shows a transmission and reflection ultrasound image of a solid mass in a breast that is typical of the images used for the study. Figure 3 shows a diagram of the case collection design. Figure 4 shows the Confidence Score Scale of cyst to solid used in the study, where 0 indicates absolute certainty of a lesion being a cyst and 100 indicates absolute certainty that a lesion is a solid.

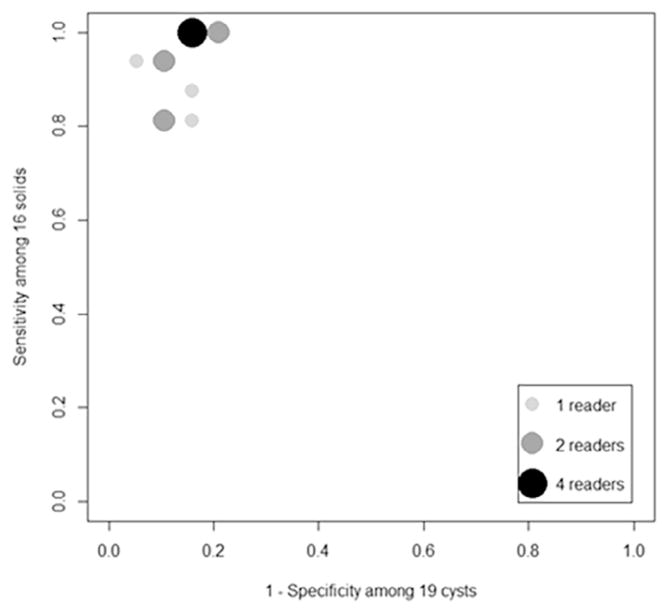

The readers’ estimated ROC areas in determining whether a mass was a cyst or a solid ranged from 0.801 to 0.980. The readers’ mean ROC area was 0.920 with 95% CI [0.827, 0.985]. Figure 5 summarizes the readers’ estimated sensitivities and 1-specificities. The sensitivities ranged from a low of 0.813 to a high of 1.0, whereas the specificities ranged from 0.789 to 0.947. The readers’ mean sensitivity and specificity were 0.933 (95% CI [0.837, 0.995]) and 0.858 [0.701, 0.985], respectively.

Figure 5.

Estimated sensitivity and false-positive results among 13 readers for transmission ultrasound.

DISCUSSION

Transmission ultrasound is an emerging technology that uses both transmission and reflection B-mode imaging to evaluate breast microanatomy and perform tissue characterization. The technology provides high accuracy in distinguishing cyst versus solid lesions in the breast. By having high spatial and contrast resolution and quantitative speed of sound measurements, transmission ultrasound can aid in distinguishing cyst versus solid lesions in the breast. Our study suggests that readers can use the QT images and successfully use the speed of sound measurements to aid in distinguishing a cyst versus a solid lesion, with an average reader accuracy of 0.920. Additionally, the mean reader sensitivity and specificity with transmission ultrasound were 0.933 and 0.858, respectively. The study was limited by the small case sample size. Additionally, five cases used in the study only had transmission images, instead of transmission and reflection B-mode images, that could have negatively affected the accuracy of the readers, although a subanalysis excluding these cases indicated little effect of reader accuracy.

The high accuracy of transmission ultrasound in distinguishing a cyst versus a solid lesion in this retrospective analysis demonstrates the importance of further study with this novel true three-dimensional automated technology for improving specificity while maintaining high sensitivity in order to prevent false-positive biopsies and ultimately provide quality breast care. We believe that transmission ultrasound imaging can be used as an adjunct to mammography to improve the sensitivity and specificity of the breast screening process. Prospective clinical trials evaluating the clinical utility of transmission ultrasound are currently being conducted by the authors.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by QT Ultrasound Labs and a grant from the National Cancer Institute (National Institutes of Health Grant R01 CA138536)

Footnotes

This study used retrospective data and has received an exemption from the Western Institutional Review Board.

References

- 1. [accessed May 18, 2017];The know error system for breast biopsies. Online: knowerror.com/biopsytypes/breast/

- 2.Ong M-S, Mandl KD. National expenditure for false-positive mammo-grams and breast cancer overdiagnoses estimated at $4 billion a year. Health Aff. 2015;34:576–583. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andre M, Wiskin J, Borup D, et al. Quantitative volumetric breast imaging with 3D inverse scatter computed tomography. Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), 2012 Annual International Conference of the IEEE; 2012. pp. 1110–1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lenox MW, Wiskin J, Lewis MA, et al. Imaging performance of quantitative transmission ultrasound. Int J Biomed Imaging. 2015;2015:8. doi: 10.1155/2015/454028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wiskin J, Borup DT, Johnson SA, et al. Non-linear inverse scattering: high resolution quantitative breast tissue tomography. J Acoust Soc Am. 2012;131:3802–3813. doi: 10.1121/1.3699240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klock JC, Iuanow EI, Malik B, et al. Anatomy-correlated breast imaging and visual grading analysis using quantitative transmission ultrasound. Int J Biomed Imaging. 2016 doi: 10.1155/2016/7570406. http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2016/7570406. Article ID 7570406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Malik B, Klock JC, Wiskin J, et al. Objective breast tissue image classification using quantitative transmission ultrasound tomography. Nature Sci Rep. 2016;6:38857. doi: 10.1038/srep38857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gerson ES, Berg WA. Screening breast sonography. Am J Roentgenol. 2003;180:1477–1478. doi: 10.2214/ajr.180.5.1801477a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Daly CP, Bailey JE, Klein KA, et al. Complicated breast cysts on sonography. Acad Radiol. 2003;15:610–617. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2007.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rinaldi P, Ierardi C, Costantini M, et al. Cystic breast lesions: sonographic findings and clinical management. J Ultrasound Med. 2010;29:1617–1626. doi: 10.7863/jum.2010.29.11.1617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berg WA, Sechtin AG, Marques H, et al. Cystic breast masses and the ACRIN 6666 experience. Radiologic Clinics. 2010;48:931–987. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2010.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harvey JA, Nicholson BT, LoRusso AP, et al. Short-term follow-up of palpable breast lesions with benign imaging features: evaluation of 375 lesions in 320 women. Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193:1723–1730. doi: 10.2214/AJR.09.2811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berg WA, Blume JD, Cormack JB, et al. Combined screening with ultrasound and mammography vs mammography alone in women at elevated risk of breast cancer. JAMA. 2008;299:2151–2163. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.18.2151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brodersen J, Siersma VD. Long-term psychosocial consequences of false-positive screening mammography. Annals Fam Med. 2013;11:106–115. doi: 10.1370/afm.1466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tosteson AA, Fryback DG, Hammond CS, et al. Consequences of false-positive screening mammograms. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:954–961. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Obuchowski NA. Nonparametric analysis of clustered ROC curve data. Biometrics. 1997;53:567–578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]