Abstract

PURPOSE

The epidermal growth factor receptor variant III (EGFRvIII) mutation has been considered a driver mutation and therapeutic target in glioblastoma, the most common and aggressive brain cancer. Currently, detecting EGFRvIII requires postoperative tissue analyses, which are ex vivo and unable to capture the tumor’s spatial heterogeneity. Considering the increasing evidence of in vivo imaging signatures capturing molecular characteristics of cancer, this study aims to detect EGFRvIII in primary glioblastoma non-invasively, using routine clinically-acquired imaging.

EXPERIMENTAL DESIGN

We found peritumoral infiltration and vascularization patterns being related to EGFRvIII status. We therefore constructed a quantitative within-patient peritumoral heterogeneity index (PHI/φ-index), by contrasting perfusion patterns of immediate and distant peritumoral edema. Application of φ-index in preoperative perfusion scans of independent discovery (n=64) and validation (n=78) cohorts, revealed the generalizability of this EGFRvIII imaging signature.

RESULTS

Analysis in both cohorts demonstrated that the obtained signature is highly accurate (89.92%), specific (92.35%) and sensitive (83.77%), with significantly distinctive ability (p=4.0033×10−10, AUC=0.8869). Findings indicated a highly infiltrative-migratory phenotype for EGFRvIII+ tumors, which displayed similar perfusion patterns throughout peritumoral edema. Contrarily, EGFRvIII− tumors displayed perfusion dynamics consistent with peritumorally-confined vascularization, suggesting potential benefit from extensive peritumoral resection/radiation.

CONCLUSIONS

This EGFRvIII signature is potentially suitable for clinical translation, since obtained from analysis of clinically-acquired images. Use of within-patient heterogeneity measures, rather than population-based associations, renders φ-index potentially resistant to inter-scanner variations. Overall, our findings enable non-invasive evaluation of EGFRvIII for patient selection for targeted therapy, stratification into clinical trials, personalized treatment planning, and potentially treatment-response evaluation.

Keywords: EGFRvIII, Imaging signature, Radiogenomics, Glioblastoma, Translational Research

Introduction

Glioblastoma (GBM) is the most common and aggressive primary malignant adult brain tumor, with an average survival of 14 months (1) following standard treatment with surgical resection and chemo-radiation, and 4 months otherwise. Despite treatment advances over the past twenty years, the lack of substantial improvement in the overall survival rates, in part, relates to the underlying molecular and cellular heterogeneity of GBM (2–5). Primarily this heterogeneous genetic landscape of GBMs and the resulting different treatment responses, gave rise to recognizing the beneficial effect of personalized medicine, leading to the current investigation and testing of new treatment options targeting specific molecular characteristics (6).

The epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), is a regulator of normal cellular growth in epithelial origin tissues (7), which has been well-validated as a target for cancer therapy, as abnormalities in its expression have been associated with reduced response to aggressive therapy (8, 9). Overexpression of the cell-surface EGFR leads to dysregulation in its signaling, which is a main contributor to the formation of many epithelial malignancies in humans (10). In such cases, which is the majority of GBM patients (11), there is typically an associated gene amplification (12) or mutation (13) in EGFR (9). The most common extracellular EGFR mutation in GBM is the variant III (EGFRvIII), alternatively named de2–7EGFR or ΔEGFR, which is an important factor in driving tumor progression and defining prognosis (14). Half of EGFR-amplified tumors harbor the EGFRvIII mutation, which is a gene rearrangement due to in-frame deletion of exons 2–7 from this receptor tyrosine kinase (15). This deletion consequently causes constitutive signaling in the absence of ligand binding (16). In contrast to wild-type EGFR, which can be found in normal tissue, EGFRvIII is expressed only in tumor cells (17), can be found nearly in 33% of GBM patients (14, 18), and its overexpression worsens the prognosis (11, 14). EGFRvIII is also associated with activation of numerous oncogenic processes leading to aggressive tumor growth and proliferation (13), hence evidence of the mutant’s presence can have an impact on treatment decisions, as well as on evaluating treatment response. For these reasons, vaccination against EGFRvIII is a potentially promising immunotherapy (17), and EGFRvIII represents a potentially viable therapeutic target for GBM patients (19, 20) that has been the target of several investigational drug trials and pilot studies (6, 21–24).

Although determination of EGFRvIII status is vital for targeted therapeutics in GBM, invasive studies are required for current tissue-based approaches, which include immunohistochemistry and next-generation-sequencing (NGS) (25, 26). The process of such approaches is primarily hindered by the spatial (4, 5) and temporal heterogeneity (6, 27–29) of molecular alterations within the GBM tumor that give rise to sampling error. Furthermore, the invasive nature of repeated biopsies makes it nearly impossible to evaluate the dynamic equilibrium of mutations and molecular characteristics that occur during the course of treatment, hence adapt the treatment accordingly. Patient stratification and selection for treatment is limited for the same reason. In other cases, the biopsy (or resection) of the tumor might not always be possible, such as in deep-seated tumors, in which there is no sufficient sample size for histopathological analysis. Finally, molecular testing may be unavailable in certain clinical settings due to cost or equipment availability.

Thus, the aim of this study is to determine the EGFRvIII status based solely on quantitative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) phenotypes. To our knowledge, this study is the first to establish a robust, reproducible, non-invasive and easy to evaluate imaging signature of the EGFRvIII expression in GBM. We hypothesized that the EGFRvIII+ tumors, which are thought to have aggressive, migratory and infiltrative phenotypes, would present imaging signatures consistent with deep infiltration throughout the peritumoral edematous tissue. In addition, we hypothesized that assessment of the tumor cell infiltration heterogeneity (30) in the peritumoral edema, may be discriminatory of the EGFRvIII status and hence lead to a distinctive imaging biomarker. Taking into consideration that edema is a result of infiltrating tumor cells, as well as a biological response to the angiogenic and vascular permeability factors released by the spatially adjacent tumor cells (31), Dynamic Susceptibility Contrast (DSC) MRI was used to indirectly measure changes in perfusion as they relate to EGFRvIII.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

Preoperative multi-parametric MRI data from a combined (discovery and replication) cohort of 142 patients (80 males, 62 females) with de novo (i.e. primary) GBM were included. The inclusion criteria for those patients comprised; a) pathological diagnosis of de novo GBM confirmed by our Board Certified Neuropathologist (M.M.-L.), b) NGS-based EGFRvIII expression, and c) availability of contrast-enhanced T1-weighted (T1-CE), T2-weighted fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (T2-FLAIR), and DSC MRI volumes. Tissue specimens of these patients were obtained by surgical resection and tested for the status of EGFRvIII at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania (HUP) between July 2006 and July 2015. Mean and median age was 59.82 and 60.95 years, respectively (range: 18.65–86.95 years). EGFRvIII was negative in 100 patients (57 males, 43 females) (70.42%) and positive in 42 patients (23 males, 19 females) (29.58%), a proportion consistent with reported rates of EGFRvIII mutation (11). Gender and age did not differ significantly between the EGFRvIII− and the EGFRvIII+ patients. The protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at HUP, and informed consent was obtained from all subjects. No randomization method was used for allocating samples to experimental groups.

Equipment and Imaging Data

The multi-parametric MRI data used in this study were acquired in the axial plane using a 3-Tesla Siemens Magnetom Trio A Tim clinical MRI system (Erlangen, Germany), according to a standardized acquisition protocol followed at HUP. For the DSC-MRI scan, the total intravenously (IV) injected dose of contrast material was divided by an initial IV loading dose to help minimize errors due to potential contrast leakage out of intravascular space, and a second bolus IV injection after a 5-minute delay. The DSC acquisition was performed during the second injection. The exact contrast material dosage amount was dependent on patient weight, i.e. 0.3 mL/kg. The dosing ratio of the initial over the second dose was 1/3 prior to September 2013 (107 patients), and 1/1 afterwards (35 patients). The contrast material used early in the study (105 patients) was gadodiamide (Omniscan, GE Healthcare, Mickleton, NJ) whilst later in the study (37 patients) was gadobenate dimeglumine (MultiHance, Bracco SpA, Milan). The T2-FLAIR volumes were acquired between the initial IV injection and the DSC acquisition. The dimensions of the T2-FLAIR images were 192×256×60 pixels, with spatial resolution of 0.938×0.938×3 mm3, slice spacing of 3mm, and inversion time (TI), repetition time (TR), and echo time (TE) equal to 2500, 9420, and 141 milliseconds (ms), respectively. The dimensions of the axial 3D T1-CE were 192×256×192 pixels, with spatial resolution of 0.976×0.976×1 mm3, slice spacing of 1mm, and TI, TR, and TE equal to 950, 1760, and 3.1 ms, respectively. The dimensions of the DSC-MRI images were 128×128×20 pixels, with spatial resolution of 1.72×1.72×3 mm3, slice spacing of 3mm and TR, TE equal to 2000 and 45 ms, respectively. Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) measures, namely the tensor’s trace DTI(TR), fractional anisotropy DTI(FA), radial diffusivity DTI(RAD) and axial diffusivity DTI(AX), were also used for comparison purposes. Axial 2D DTI scans were acquired using a single-shot spin echo planar imaging sequence (Variant: segmented k-space\spoiled, Options: Partial Fourier-Phase\Fat Saturation), with 95 phase encoding steps. Following acquisition at b=0 s mm−2 (repeated 3 times), diffusion weighted images were acquired (b=1000 s mm−2) with diffusion gradients applied in 30 directions. The dimensions of the DTI volumes were 128×128×40 pixels (matrix size=128×128, field of view=220×220 mm2), with spatial resolution of 1.72×1.72×3 mm3, slice spacing of 3mm, flip angle of 90, imaging frequency of 123, and TR and TE equal to 5000ms and 86ms, respectively.

Determination of EGFRvIII mutation status

The histological confirmation of GBM diagnosis was performed by a Board Certified neuropathologist reviewing the pathology of surgically resected tissue, according to the WHO classification criteria. The most representative block per resected tissue specimen was chosen by the neuropathologist on the basis of morphology and was included for genetic analysis. The advantage of this and the ability to use Formalin-fixed Paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue lies upon the knowledge of the precise characteristics of the material used for RNA extraction, as opposed to other assays based on fresh tissue, in which one may be testing necrosis or inflammation instead of the highest number of tumor cells possible, without the ability to quality control what goes into the assay. An in-house NGS-based assay to detect EGFRvIII transcripts (25, 26) has been developed, which was validated with detection by Taqman Reverse Transcription-Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR). Total nucleic acid was extracted from FFPE tissue, and complementary DNA was then synthesized from RNA. PCR primers were designed to capture EGFR wild-type, EGFRvIII, three housekeeping genes, and three primer sets with increasing target sizes to assess the level of RNA degradation in the sample. The sequencing library preparation method was a two-step PCR, with multiplex PCR followed by a second PCR to add Illumina sequencing index and adaptors. Subsequently, the sequencing library was quantified, sequenced on Illumina MiSeq, and analyzed using a bioinformatics pipeline developed in our lab, “EGFRvIII Picker”. EGFRvIII ratio was calculated by the following formula: EGFRvIII reads/(EGFRvIII reads + EGFR wild-type reads). Based on our results using normal brains and GBMs, our cut-off for EGFRvIII+ is >30% EGFRvIII to wild-type allele ratio.

Image Preprocessing

The provided MRI volumes were smoothed using a low-level image processing method, namely Smallest Univalue Segment Assimilating Nucleus, in order to reduce high frequency intensity variations (i.e., noise) in regions of uniform intensity profile while preserving the underlying structure (32). The intensity non-uniformities caused by the inhomogeneity of the magnetic field during image acquisition were removed using a non-parametric, non-uniform intensity normalization algorithm (33). The volumes of all the modalities for each patient were co-registered to the T1-CE anatomic template using a 6-degrees-of-freedom affine registration, and then skull-stripped (34).

Regions of interest and perfusion temporal dynamics

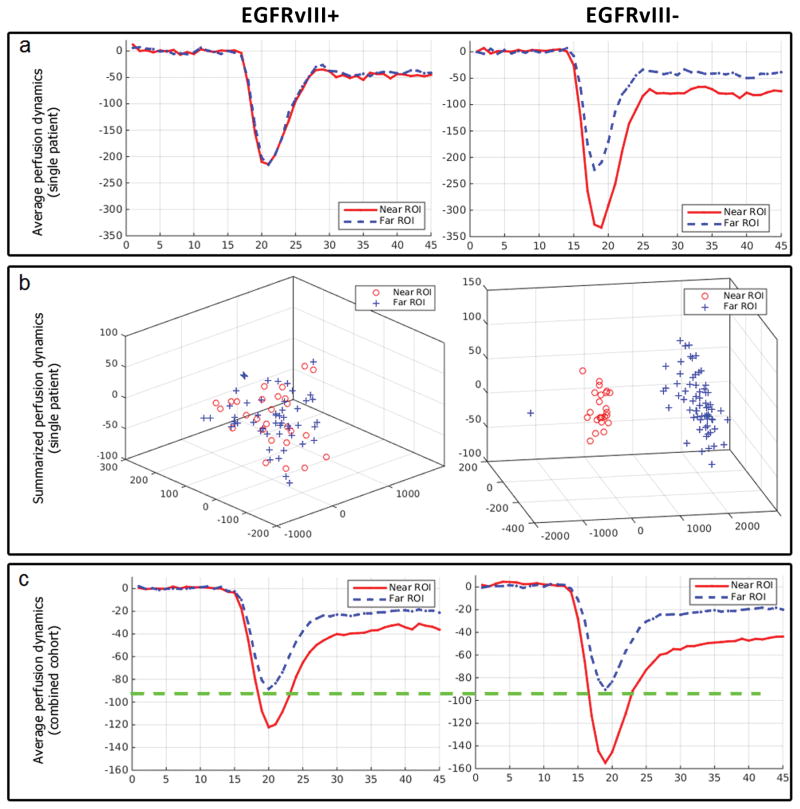

To assess the tumor cell infiltration heterogeneity within the peritumoral edema (i.e., the peritumoral area described by hyper-intensity on the T2-FLAIR volumes) (30), two regions of interest (ROIs) were annotated for each patient by an expert (Fig. 1), blinded to EGFRvIII status. These two ROIs were used to sample tissue located on the two boundaries of edema: near to and far from the tumor, respectively, and hence to evaluate the heterogeneity or spatial gradient of perfusion signals. The T1-CE and T2-FLAIR volumes were used to define the ROIs near to and far from the tumor, respectively. Specifically, the T1-CE volume was used to initially define the ROI adjacent to the enhancing part of the tumor, described by hyper-intense signal on T1-CE, and the T2-FLAIR volume was then used to revise this ROI in terms of all its voxels being within the peritumoral edematous tissue, described by hyper-intense signal on the T2-FLAIR volume. The T2-FLAIR volume was also used to define the ROI at the farthest from the tumor but still within the edematous tissue, i.e. the enhancing FLAIR abnormality signal. These ROIs are described by lines drawn in multiple slices of each image (T1-CE and T2-FLAIR) for each subject, whereas the visual example of Fig. 1 shows only a single slice. The perfusion temporal dynamics for each of these ROIs were obtained from the DSC-MRI volume (Fig. 2.a). Specifically, the perfusion of each voxel during 45 time-points was used to form a feature vector of 45 dimensions. Principal component analysis (PCA) was then used to summarize the perfusion signal of each ROI, as in (31). Specifically, the property of PCA to represent data as an ellipsoidal population in a lower dimensional space, whilst retaining most of its variance, was exploited on these feature vectors. As shown in Figure 2.b, each of these feature vectors can be represented as a single point in a 3-dimensional space. The voxels of each ROI, with similar dynamic behavior, would form almost elliptical clusters of points (ellipsoids) in this 3-dimensional space.

Figure 1.

Example of the immediate and distant peritumoral region of interest (ROI) annotations. Image a illustrates in red an example ROI defined adjacent to the enhancing part of the tumor superimposed on a T1-CE axial image, and image b illustrates in blue an example ROI defined in the periphery of the tumor within edema superimposed on a T2-FLAIR axial image. Note that these ROIs are described by lines annotated in multiple slices for each subject and not just in a single slice, as shown in this visual example.

Figure 2.

Temporal perfusion dynamics for the described immediate and distant peritumoral regions of interest (ROIs), by EGFRvIII expression status. a illustrates examples of aligned average perfusion curves for individual patients. b shows the summarization of perfusion curves through principal component analysis in three components. Note that each perfusion curve in a is represented by a single dot in b. These summarized perfusion curves show more separability (higher φ-index) between the immediate and the distant peritumoral ROI measures among EGFRvIII− patients compared to EGFRvIII+ patients. c illustrates aligned average perfusion curves across 142 patients. Note that the drop in the perfusion signal for the distant peritumoral ROI is almost identical between across all patients, and that the average drop in the immediate peritumoral ROI is much deeper among the EGFRvIII− patients compared to EGFRvIII+ patients.

It should be noted that while drawing these ROIs, 1) the voxels of both ROIs are always within the edema, 2) not in proximity to the ventricles, 3) representative of infiltration into white matter and not into grey matter, 4) the distant ROI is at the farthest possible distance from the enhancing part of the tumor while still within edema, and 5) no vessels are involved within any of the defined ROIs, as denoted in the T1-CE volume.

Measurement of heterogeneity

The Bhattacharyya coefficient (35) is used as a measure of heterogeneity within the peritumoral edema (Peritumoral Heterogeneity Index – PHI, or φ-index), by measuring the separability (range [0,1]) between the summarized ellipsoids of these ROIs for each patient. The Bhattacharyya distance is considered the most reliable for the purpose of measuring the distance of a point observation from a distribution of observations along each principal axis, namely after conducting PCA (36).

Robustness Analysis

Although calculation of the φ-index is mostly automated, it currently requires expert drawing of the immediate and distant peritumoral ROIs (Fig. 1). To test the robustness and reproducibility of the index with respect to this expert input, the intra- and inter-rater agreements were evaluated, using the Intra-class Correlation Coefficient (ICC). Specifically, 40 patients of the combined cohort were randomly selected and new ROIs were defined by a) the same operator but on a different instance (3 months later); b) another operator. The new set of ROIs was drawn in a much faster and less detailed manner, in order to test the reproducibility of PHI in a more typical clinical setting. The definition of the ROIs was conducted by a medical doctor (H.A.) and a computer scientist (S.B.) working in medical image analysis for 8 and 10 years, respectively. This implies that any operator with medical image understanding can conduct this analysis and retrieve PHI, as long as (s)he follows the aforementioned rules, without the background of a neuro-radiologist being required.

Code Availability

We developed the PHI-Estimator, to enable others easily conduct this analysis and retrieve our Peritumoral Heterogeneity Index (PHI). The code source and executable installers are available on: www.med.upenn.edu/sbia/phiestimator.html.

Results

Brief description of the experiment

To assess the peritumoral heterogeneity, two ROIs were defined within the peritumoral edema: one ROI adjacent to the enhancing part of the tumor, typically depicted by high T1-CE signal intensity, and the other at the farthest from the tumor but still within the edema (Fig. 1). The average size for the near and far ROIs (across all subjects) is 72.2 and 172.3 voxels, respectively, which can be considered sufficient in order to account for potentially noisy voxels included in the ROIs. A recently published method (31) utilizing PCA was employed to summarize the perfusion temporal dynamics of each ROI into a group of few principal components capturing more than 95% of the signal’s variance. The Bhattacharyya coefficient (35) was then used to measure the separability between the summarized perfusion measurements of the two ROIs for each patient, and evaluated as a biomarker of EGFRvIII. We refer to this separability measurement as Peritumoral Heterogeneity Index (PHI), or φ-index. Values of the φ-index close to 0 indicate similar perfusion dynamics between the two ROIs, consistent with deeply and aggressively infiltrating and vascularized tumors (37). Such values could also indicate normal phenotype throughout the edema, which is rather unlikely in these aggressively infiltrating tumors. Conversely, values of the φ-index close to 1 indicate substantially different perfusion characteristics between the two ROIs, consistent with a less migratory phenotype of more localized peritumoral infiltration and vascularization, in which tumor-like perfusion characteristics are relatively confined to the vicinity of the tumor.

PHI yields significantly distinct distributions for EGFRvIII+ and EGFRvIII− patients

The φ-index was initially estimated for a discovery cohort of 64 patients (22 EGFRvIII+) with de novo GBM and displayed significantly distinct distributions between EGFRvIII− and EGFRvIII+ patients (p=1.5725×10−7, AUC=0.9459), with median φ values of 0.3097 and 0.0961 and Inter-Quartile Range (IQR) of [0.1855–0.4808] and [0.0509–0.1095], respectively (Fig. 3.a). Subsequently, an independent replication cohort of 78 patients (20 EGFRvIII+) was analyzed in the same way, and the φ-index distributions for the EGFRvIII− and EGFRvIII+ tumors returned equivalently distinct results (p=2.8164×10−4, AUC=0.8336), with median values of 0.2586 (IQR: [0.1659–0.3938]) and 0.0952 (IQR: [0.0411–0.1348]), respectively (Fig. 3.b). The best threshold (accuracy=0.9219, specificity=0.9762, sensitivity=0.8182) in the φ-index for the discovery cohort was 0.1372, which when applied to the replication cohort returned an accuracy of 0.8590 (specificity=0.8793, sensitivity=0.8) confirming its generalizability.

Figure 3.

Distributions of the Peritumoral Heterogeneity Index (PHI) by EGFRvIII expression status across the discovery cohort in a, the replication cohort in b, and the combined cohort in c. Statistical significance was evaluated via a two-tailed paired t-test comparing between the two distributions of a. the discovery cohort (p=1.5725×10−7), b. the replication cohort (p=2.8164×10−4), and c. the combined cohort (p=4.0033×10−10). The bottom and top of each “box” depict the 1st and 3rd quartile of the PHI measure, respectively. The line within each box indicates the median, and the fact that it is not necessarily at the center of each box indicates the skewness of the distribution over different cases. The “whiskers” drawn external to each box depict the extremal observations still within 1.5 times the interquartile range, below the 1st or above the 3rd quartile. Observations beyond the whiskers are marked as outliers with a “+” sign.

Furthermore, the two cohorts were combined into one larger cohort, of 142 patients (42 EGFRvIII+), and the distinctiveness of the distributions of the φ-index for EGFRvIII− and EGFRvIII+ tumors was even more significant (p=4.0033×10−10, AUC=0.8869), with median values of 0.2806 (IQR: [0.1759–0.4088] and 0.0961 (IQR: [0.0505–0.1309]), respectively. Comparison of the median values, as well as the first and the third quartiles, between the two distributions reveals the ability to distinguish between them based solely on the PHI (Fig. 3.a). To statistically evaluate the significance of the results obtained for the combined cohort, a two-tailed paired t-test was used to compare between the two distributions (Fig. 3.c). This statistical analysis returned a p-value=4.0033×10−10, which confirmed at the 5% significance level that the patients in the pool of EGFRvIII− and EGFRvIII+, come from populations with unequal means, with the confidence interval (CI) on the difference of the means being [0.1526, 0.2795]. A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was also used in the combined cohort to illustrate the performance of PHI on an individual patient basis (Fig. 4.l). The ROC curve was created by plotting the sensitivity against the false positive rate (i.e., 1-specificity) at various thresholds of PHI. The threshold set on 0.1377 returned the best accuracy (88.73%), with sensitivity and specificity equal to 80.95% and 92%, respectively (AUC=0.8869, standard error 0.0351, 95% CI: [0.8180–0.9558]).

Figure 4.

Receiver Operating Characteristics (ROC) Analyses. ROC curves are illustrated in: i) a–i for individual MRI modalities across 140 patients, ii) j and k for combination of modalities across 140 patients, and iii) l for our final proposed approach in 142 patients.

To demonstrate that the results of perfusion heterogeneity between the two ROIs for each subject within the two EGFRvIII groups were not confounded by a potentially larger extent of edema in one of the two groups, we assessed the distance between the two ROIs against the φ-index for each patient (Supplementary Fig. S1) and noted that there is no correlation between them (correlation coefficient:0.0519, p-value=0.5394). Furthermore, by assessing the distribution of distances between the two ROIs for each EGFRvIII group, we show that the extent of the edema between these two groups has no significant difference (p-value=0.6728) (Supplementary Fig. S2). This shows that the obtained results of PHI variation between EGFRvIII+ and EGFRvIII− tumors is a true finding and not an effect of different amount of edema observed between the two groups. A single slice of an example subjects of each EGFRvIII group are shown in Supplementary Fig. S3, in order to show the similar extent of the edema.

Unbiased Estimates of Performance through nested Cross-Validation

A nested 10-fold cross-validation was also performed over the combined cohort using a model configuration of three sets: the training set, for deriving the predictive model; the validation set, for selecting the optimal threshold for the φ-index; and the test set, for testing the generalization of predictions on new/unseen data, thereby avoiding optimistically biased estimates of performance. The cross-validated accuracy, sensitivity and specificity were estimated equal to 89.92%, 83.77% and 92.35%, respectively, and the optimal threshold of the φ-index was found to be 0.1377 in consistency with the one found in the ROC analysis.

Repeatability and Reproducibility of PHI

The median φ values for the intra-rater subset were 0.2761 (IQR: [0.1572–0.4046]) and 0.065 (IQR: [0.0389–0.1303]) for EGFRvIII− and EGFRvIII+ patients, respectively (p=2.8529×10−5, AUC=0.8846), whereas the median φ values for the inter-rater subset were 0.2273 (IQR: [0.1512–0.3426]) and 0.1112 (IQR: [0.0579–0.1294]) (p=0.003, AUC=0.8242). The ICC was 0.825 among the same rater and 0.775 among different raters.

Discriminative value of other MRI modalities

Additional MRI modalities were assessed to investigate their discriminative ability, compared to that of the DSC-MRI. These comprised: native T1-weighted (T1), T1-CE, T2, T2-FLAIR, DTI(TR), DTI(FA), DTI(RAD) and DTI(AX). The number of patients was reduced to 140 due to data availability. It is observed that all additional modalities had notably poorer discrimination ability (Fig. 4.a–h) and the distributions of PHI for each of them were not distinct between the different EGFRvIII genotypes. Furthermore, a support-vector-machine was used for a multivariate analysis of a complete joint/multifaceted model, where only the DTI(TR) (p=0.0053) and T1 (p=0.0054) were found to be significant (38), additive to the DSC. ROC analysis of these two joint models, namely DSC-TR and DSC-TR-T1 showed very small improvement over DSC-MRI alone (Fig. 4.i–k), with AUCDSC=0.8857, AUCDSC-TR=0.8985 and AUCDSC-TR-T1=0.9019.

Discussion

This study is the first to establish a robust, reproducible, non-invasive and easy to evaluate imaging signature of EGFRvIII in de novo GBM, based on quantitative analysis of peritumoral regions and not on assessment of intratumoral regions that the current general knowledge and understanding of the EGFRvIII status in GBMs is currently based. The results demonstrate that assessment of the heterogeneity of perfusion temporal dynamics throughout the peritumoral edema on in vivo MRI data predicts the EGFRvIII mutation status, hence reveals an accurate (89.92%), sensitive (83.77%) and specific (92.35%) imaging biomarker of the mutation, which can be used clinically for personalized treatment decisions and response evaluations. Our findings support the strengths of an emerging approach that we have termed computational molecular imaging, which refers to molecular target determination by virtue of their distinct imaging phenotypical patterns without the need to deliver specialized molecular probes to the tissue. Importantly, results are obtained using commonly acquired clinical MRI scans as part of standard clinical practice, thereby increasing the likelihood of their translation to the clinic.

EGFRvIII identification in GBM patients using radiographic analysis alone holds significant clinical relevance in terms of personalized medicine. Traditional identification of genomic mutations, such as EGFRvIII by tissue-based techniques, requires invasive surgical resection or biopsy, and is obtained from a single tissue specimen, whereas we report a non-invasive, purely image-based approach for pre-operative evaluation of this molecular target. Since glioma cells bearing the mutant are not uniformly distributed throughout a tumor, sampling error may occur with tissue-based approaches. Conversely, imaging captures the tumor’s spatial heterogeneity more completely, minimizes bias potentially occurring by evaluating a limited portion of tumor, and can provide data on the regional EGFRvIII expression. Such global assessment of the mutant could be used as a more accurate guide to patient selection for clinical trials. Furthermore, once the mutation is identified, EGFRvIII− targeted therapies can be selected. In addition to selecting initial treatment, there may be significant value in detection of EGFRvIII at additional time-points following treatment initiation, as it has been shown that expression of the mutant may be lost at the time of progression (29) following standard chemo-radiation in approximately half of patients (28). There is also a high probability (>80%) of losing EGFRvIII expression following EGFRvIII peptide vaccination (27). Consistent with this finding, antigen editing with quantitative loss of EGFRvIII is also observed, after infusion of genetically modified chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cells targeting EGFRvIII in recurrent GBM patients (21). By using standard clinical imaging sequences, a longitudinal evaluation of EGFRvIII in patients both after treatment and with recurrent tumors, represents a feasible approach to detect changes in EGFRvIII expression. Unlike repeated biopsies, such monitoring can be performed repeatedly without risk and with decreased cost over time. Thus, an imaging-based approach for EGFRvIII identification can aid in all phases of care of the GBM patient from diagnosis to targeted therapy to response surveillance.

Although most of the attention in characterizing tumors has been placed on the tumor bulk, the peritumoral edema, typically depicted by high T2-FLAIR signal intensity, holds much additional data. Despite the fact that more than 90% of recurrences occur in edema (39) due to the highly infiltrative nature of GBM, there is limited research focused on the assessment of this region and its microenvironment (2, 40). Edema results from infiltrating tumor cells and the biological response to the angiogenic and vascular permeability factors released by the spatially adjacent tumor cells (31). Although the peritumoral edema remains mostly unresected and is generally not aggressively treated, by virtue of hosting the tumor’s “propagating font” it is critically important for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes.

Large GBM tumors typically outgrow their blood supply, which results in ischemia, secretion of angiogenic factors, such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and cytokines that eventually lead to neovascularization, increased permeability, and edema (41, 42). These new vessels, when compared with the existing healthy blood vessels, have an increasingly tortuous and branched structure, as well as higher permeability, which typically affect the brain circulation. Such alterations in the brain circulation are captured by DSC-MRI, which is based on the decay of T2 signal during the first pass of a paramagnetic contrast medium through the capillary bed. Therefore, DSC-MRI enables the generation of a perfusion curve by assessing the dynamic changes in the signal intensity of the peritumoral region of a GBM through time. Analysis of the complete perfusion signal through PCA enables microvascular imaging and provides a visual correlation of blood flow, blood volume, and vessel permeability (31).

Variations in the perfusion signal between the immediate and distant peritumoral ROIs relate to phenotypic characteristics conferred by the presence of EGFRvIII. Based on the φ-index, we found that EGFRvIII+ tumors had very similar, and relatively normal immediate and distant peritumoral perfusion patterns, in contrast to the EGFRvIII− tumors (Fig. 2). This finding is consistent with relatively more locally infiltrating EGFRvIII− tumors, accompanied by localized immediate peritumoral vascularization. Note that “more locally infiltrating” does not refer to a generally more infiltrative tumor. Conversely, deeply infiltrating and migrating EGFRvIII+ tumors displayed a more uniform peritumoral perfusion phenotype, consistent with less intense peritumoral vascularization facilitated by the migratory characteristics of EGFRvIII+ tumors that likely allows them to gain access to blood supply farther from the bulk of the tumor. Differences in the perfusion signal (Fig. 2) enabled us to derive an accurate, sensitive and specific imaging biomarker based on DSC-MRI. Specifically, the distribution of the φ-index values (Fig. 3.c) across the EGFRvIII− population has a much larger range of values [0.0340–0.8944] and IQR [0.1759–0.4088] when compared to the distribution across the EGFRvIII+ patients (range:[0.0080–0.5039], IQR:[0.0505–0.1309]). This discrepancy might reflect the underlying expression heterogeneity (2–5), which is prevalent in GBM, with the EGFRvIII− patients potentially expressing the mutant form in areas that were not sampled for tissue analysis, and tumors that were found to be EGFRvIII+ being more likely to have developed the full phenotype of the mutant. It is well-documented that oncogenic EGFRvIII confers a more motile and invasive phenotype to neural stem cells (43) and GBM cells (37). Furthermore, the narrow range of the φ-index distribution across the EGFRvIII+ patients suggests high specificity in terms of identifying a new EGFRvIII+ patient, which can be achieved without significant loss of sensitivity.

DSC-MRI alone was the focus of this study, even though is an advanced imaging modality that is not always available. However, mounting evidence for the importance of this modality (18, 31, 40) has rapidly increased its adoption in standard clinical settings. Nevertheless, assessment of additional MRI modalities to investigate if a joint/multifaceted model of the peritumoral heterogeneity could lead to an improved biomarker of EGFRvIII showed that only DTI(TR) and T1 were significant, in addition to DSC-MRI (Fig. 4.i–k). However, considering the improvement offered by including these modalities, we still think there is little value in adding other MRI modalities to DSC, unless those additional sequences are acquired anyway for other reasons. Notably, we found that the differences in PHI between the EGFRvIII+ and EGFRvIII− patients were minimal for DTI(TR) (Fig. 5). This would be consistent with similar cell density between the two defined ROIs and for both EGFRvIII genotypes. The actual difference between the EGFRvIII+ and the EGFRvIII− patients lays in the gradient of vascularization throughout the edema that looks to be almost identical for the EGFRvIII+ patients, as opposed to the EGFRvIII− patients, who show a larger drop in the perfusion of the immediate peritumoral ROI, i.e. more confined infiltration and vascularization (Fig. 2, 6). This implies that the EGFRvIII− patients might benefit from a slightly more extended resection and focused radiation, in order to include the immediate peritumoral edema.

Figure 5.

Scatter plot of the Peritumoral Heterogeneity Index (PHI), by EGFRvIII expression status across 140 patients, in the DSC modality (x axis) over the PHI in the DTI-TR measure (y axis) in a, and over the PHI in the T1 modality (y axis) in b.

Figure 6.

Scatter plot of the DTI-TR measure, by EGFRvIII expression status across 140 patients, for the region adjacent to the enhancing tumor (x axis) over the region at the periphery of the edema (y axis).

Our study has several aspects that distinguish it from prior related studies (18, 40, 44–47), which were either demonstrating population-wide associations, thereby not focusing on establishing an individual-patient biomarker, or not validating their results in an independent replication cohort, which is critical for a clinically useful biomarker. Firstly, and most importantly, the results obtained in our study are based on individual-patient in vivo measures and show high accuracy in addition to providing pathophysiological insights, hence increasing the likelihood of the φ-index being clinically applicable. Secondly, instead of limiting the use of perfusion imaging in retrieving isolated hemodynamic features (e.g., leakage corrected relative cerebral blood volume – Supplementary Fig. S4), we employ the complete perfusion signal via PCA, which allows for more comprehensive analysis as it encapsulates the complete hemodynamic information. Thirdly, instead of reporting only results on a discovery set, we use two independent cohorts for the purpose of identification (initial discovery set) of the proposed φ-index and confirmation (independent replication cohort) of its discriminatory generalizability in unseen data. These two cohorts could be noted as retrospective and prospective, since the images of the replication (i.e., prospective) cohort were obtained after the index was identified in the discovery (i.e., retrospective) cohort, and EGFRvIII status for the replication cohort was obtained after the φ-index was estimated for all its patients. Furthermore, we combined these two cohorts under a nested cross-validation scheme, to quantitatively validate the generalization performance of PHI and its threshold, whilst providing unbiased performance estimates. The advantage of cross-validation lies upon the observation that high accuracy score obtained for the training set, might have been obtained through “overfitting” to the training data. The accuracy score obtained for the training set is likely to be higher than the accuracy score obtained by applying the method to new examples, not seen in the training set. Thus, the reported cross-validated performance score and its corresponding φ-index threshold may be considered unbiased. Additionally, none of these previous studies investigate for the reproducibility of their findings, whereas in our case both inter- and intra-rater agreements are evaluated in almost one third of the included data.

This study evaluated the expression status of EGFRvIII alone, as a binary present/absent value, and did not account for other mutations or amplifications in EGFR that might alter the perfusion signal. However, the frequency of EGFRvIII was similar to the rates reported in the literature (11). It is known that EGFR amplification may increase between the initial diagnosis and recurrence (28), and that loss of EGFRvIII may be due to EGFR amplification and individual cells harboring varying levels of EGFRvIII (48) or even regulated by the tumor (49). Thus, it would be informative to include the EGFR amplification values in a future analysis, which could further explain the widespread of PHI values for the EGFRvIII− tumors. We currently consider patients labeled as EGFRvIII−, but with low φ-index values, as patients that may potentially express the mutant in areas that were not sampled for tissue analysis, resulting in inappropriate classification. Future prospective studies could be conducted for retrieving the mutant status on specific spatially distinct radiologically-guided localized biopsies, as described in other studies (4, 50). Then, the proposed φ-index would be employed for evaluating the mutant on these specific known locations, facilitating the creation of a parametric map of EGFRvIII expression. Last but not least, a larger cohort should be considered for analysis, consisting of patients scanned using different equipment, with the intention of validating the robustness of the proposed marker to acquisition differences.

The ability to non-invasively determine the status of EGFRvIII in GBM patients, only by assessing DSC-MRI scans, can assist in obtaining the mutant status faster and more easily. Application of PCA in the raw DSC-MRI signal reveals informative features that represent distinctive imaging phenotypes correlating to EGFRvIII in GBM. This EGFRvIII imaging signature is constructed in a manner that should be robust to MRI scanner variations, by virtue of evaluating within-patient heterogeneity measures, rather than relying on population-wide associations (45–47). The obtained cross-validated results demonstrate that discrimination of the EGFRvIII status, which is critical for personalized treatment decisions and response evaluation, can be achieved based solely on assessing the peritumoral heterogeneity on in vivo perfusion imaging data, whilst potentially obviating costly and not widely-available tissue-based genetic testing. The cross-validation scheme over the available patient data provided unbiased performance estimates and quantitatively validated the generalization performance of the φ-index and its classification threshold. The proposed φ-index contributes to personalized medicine by allowing the identification of an important molecular target on an individual patient basis, using widely available clinical imaging protocols. These characteristics enable the identification of individual patients that could benefit from selective treatments in a more efficient and less invasive way than by current options, with the intention of improving patient prospects while minimizing the risk of side effects.

Supplementary Material

Statement of Translational Relevance.

The discovered non-invasive personalized in vivo imaging marker of EGFRvIII utilizes clinically-available imaging protocols, without the need to deliver radiolabeled probes, which renders it likely for immediate translation into the clinic as a first-line detection of this molecular target. Its accuracy, specificity, sensitivity, and independent sample reproducibility, further support its potential routine clinical use. Moreover, our study revealed a biologically important characteristic associated with the EGFRvIII mutation: EGFRvIII− tumors show relatively more localized peritumorally-confined infiltration and dense vascularization, whereas EGFRvIII+ tumors show characteristics consistent with high motility and potentially with lower need to develop additional vasculature, by virtue of being able to access blood supply deep in the peritumoral region. This EGFRvIII signature contributes to personalized medicine, and can enable non-invasive patient selection for targeted therapy, stratification into clinical trials, and repeatable monitoring of the mutant during the treatment course, in addition to influencing surgical resection and subsequent radiotherapy.

Acknowledgments

Financial support: Source: National Institutes of Health; Grants: R01-NS042645, U24-CA189523

This work was primarily supported by two grants awarded from the National Institutes of Health (NIH); 1) R01 grant on “Predicting brain tumor progression via multiparametric image analysis and modeling” (R01-NS042645), and 2) U24 grant of “Cancer imaging phenomics software suite: application to brain and breast cancer” (U24-CA189523). It was also supported in part by a sponsored research grant from Celldex Therapeutics to the University of Pennsylvania (D.M.O).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest disclosure statement: The application and results of a preliminary version of the proposed approach, in a smaller population size, were presented at the 20th Annual Scientific Meeting of the Society for Neuro-Oncology 2015 in San Antonio, Texas. The authors declare that they have no other potential conflicts of interest.

Author contributions

S.B., H.A., D.M.O’R. and C.D. conceived and designed the study; S.B., H.A. and C.D. conceived and designed the predictive features; J.P. retrieved the examination details for each subject from the radiology reports; M.R. retrieved and pre-processed the imaging data corresponding to patients from the Brain Tumor Tissue Bank (BTTB) of the University of Pennsylvania (UPenn); N.D. and D.M.O’R. provided access to UPenn’s BTTB and EGFRvIII genotype; M.-M. L. did the histological confirmation of the tumor samples and developed the NGS-based assay to detect EGFRvIII transcripts and its validation with detection by RT-PCR; S.R. implemented the developed algorithm into a software tool, publicly available in www.med.upenn.edu/sbia/phiestimator.html; S.B., H.A. and S.R. analyzed the provided data; S.B. and H.A. perceived the rules for drawing the ROIs, made the ROI annotations, interpreted the data, analyzed and validated the obtained results; C.D. sponsored this research through the NIH grants R01-NS042645 and U24-CA189523; S.B. wrote the manuscript; H.A., J.P, M-M.L., M.R., S.R., N.D., D.M.O’R., and C.D. edited the manuscript; All authors read and approved the manuscript.

References

- 1.Johnson DR, O’Neill BP. Glioblastoma survival in the United States before and during the temozolomide era. Journal of Neuro-Oncology. 2011;107:359–64. doi: 10.1007/s11060-011-0749-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lemee J-M, Clavreul A, Menei P. Intratumoral heterogeneity in glioblastoma: don’t forget the peritumoral brain zone. Neuro-Oncology. 2015;17:1322–32. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nov119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aum DJ, Kim DH, Beaumont TL, Leuthardt EC, Dunn GP, Kim AH. Molecular and cellular heterogeneity: the hallmark of glioblastoma. Neurosurg Focus. 2014;37:E11. doi: 10.3171/2014.9.FOCUS14521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sottoriva A, Spiterib I, Piccirillo SGM, Touloumis A, Collins VP, Marioni JC, et al. Intratumor heterogeneity in human glioblastoma reflects cancer evolutionary dynamics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:4009–14. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1219747110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patel AP, Tirosh I, Trombetta JJ, Shalek AK, Gillespie SM, Wakimoto H, et al. Single-cell RNA-seq highlights intratumoral heterogeneity in primary glioblastoma. Science. 2014;344:1396–401. doi: 10.1126/science.1254257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O’Rourke D, Chang S. Pilot Study of Autologous T Cells Redirected to EGFRVIII-With a Chimeric Antigen Receptor in Patients With EGFRvIII+ Glioblastoma. 2014 (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02209376) [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gan H, Cvrljevic A, Johns T. The epidermal growth factor receptor variant III(EGFRvIII): where the wild things are altered. FEBS Journal. 2013;280:5350–70. doi: 10.1111/febs.12393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Verhaak R, Hoadley K, Purdom E, Wang V, Qi Y, Wilkerson M, et al. Integrated Genomic Analysis Identifies Clinically Relevant Subtypes of Glioblastoma Characterized by Abnormalities in PDGFRA, IDH1, EGFR, and NF1. Cancer Cell. 2010;17:98–110. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brennan CW, Verhaak RGW, McKenna A, Campos B, Noushmehr H, Salama SR, et al. The Somatic Genomic Landscape of Glioblastoma. Cell. 2013;155:462–77. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Humphrey P, Wong A, Vogelstein B, Zalutsky M, Fuller G, Archer G, et al. Anti-synthetic peptide antibody reacting at the fusion junction of deletion-mutant epidermal growth factor receptors in human glioblastoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:4207–11. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.11.4207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heimberger AB, Suki D, Yang D, Shi W, Aldape K. The natural history of EGFR and EGFRvIII in glioblastoma patients. Journal of Translational Medicine. 2005:3. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-3-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arteaga C. Epidermal growth factor receptor dependence in human tumors: more than just expression? Oncologist. 2002;7:31–9. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.7-suppl_4-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nishikawa R, Ji X, Harmon R, Lazar C, Gill G, Cavenee W, et al. A mutant epidermal growth factor receptor common in human glioma confers enhanced tumorigenicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:7727–31. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.16.7727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heimberger AB, Hlatky R, Suki D, Yang D, Weinberg J, Gilbert M, et al. Prognostic effect of epidermal growth factor receptor and EGFRvIII in glioblastoma multiforme patients. Clinical Cancer Research. 2005;11:1462–6. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gan HK, Kaye AH, Luwor RB. The EGFRvIII variant in glioblastoma multiforme. Journal of Clinical Neuroscience. 2009;16:748–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2008.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fan Q-W, Cheng CK, Gustafson WC, Charron E, Zipper P, Wong RA, et al. EGFR Phosphorylates Tumor-Derived EGFRvIII Driving STAT3/5 and Progression in Glioblastoma. Cancer Cell. 2013;24:438–49. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sampson JH, Archer GE, Mitchell DA, Heimberger AB, Bigner DD. Tumor-specific immunotherapy targeting the EGFRvIII mutation in patients with malignant glioma. Semin Immunol. 2008;20:267–75. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tykocinski ES, Grant RA, Kapoor GS, Krejza J, Bohman LE, Gocke TA, et al. Use of magnetic perfusion-weighted imaging to determine epidermal growth factor receptor variant III expression in glioblastoma. Neuro-Oncology. 2012;14:613–23. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nos073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kalman B, Szep E, Garzuly F, Post DE. Epidermal growth factor receptor as a therapeutic target in glioblastoma. Neuromolecular medicine. 2013;15:420–34. doi: 10.1007/s12017-013-8229-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Veliz I, Loo Y, Castillo O, Karachaliou N, Nigro O, Rosell R. Advances and challenges in the molecular biology and treatment of glioblastoma - is there any hope for the future? Ann Trans Med. 2015;3:7. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2305-5839.2014.10.06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O’Rourke D, Desai A, Morrissette J, Martinez-Lage M, Nasrallah M, Brem S, et al. Pilot Study of T Cells Redirected to EGFRvIII with a Chimaric Antigen Receptor in Patients with EGFRvIII+ Glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol. 2015;17:v110–v1. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Celldex. Phase III Study of Rindopepimut/GM-CSF in Patients With Newly Diagnosed Glioblastoma (ACT IV) 2011 (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01480479) [Google Scholar]

- 23.Celldex. A Study of Rindopepimut/GM-CSF in Patients With Relapsed EGFRvIII-Positive Glioblastoma (ReACT) 2011 (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01498328) [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thomas AA, Brennan CW, DeAngelis LM, Omuro AM. Emerging therapies for glioblastoma. JAMA Neurol. 2014;71:1437–44. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Daber R, Sukhadia S, Morrissette JJ. Understanding the limitations of next generation sequencing informatics, an approach to clinical pipeline validation using artificial data sets. Cancer Genet. 2013;206:441–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergen.2013.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hiemenz MC, Kadauke S, Lieberman DB, Roth DB, Zhao J, Watt CD, et al. Building a Robust Tumor Profiling Program: Synergy between Next-Generation Sequencing and Targeted Single-Gene Testing. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0152851. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0152851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gedeon PC, Choi BD, Sampson JH, Bigner DD. Rindopepimut: anti-EGFRvIII peptide vaccine, oncolytic. Drugs Future. 2013;38:147–55. doi: 10.1358/dof.2013.038.03.1933992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bent MJvd, Gao Y, Kerkhof M, Kros JM, Gorlia T, Zwieten Kv, et al. Changes in the EGFR amplification and EGFRvIII expression between paired primary and recurrent glioblastomas. Neuro-Oncology. 2015;17:935–41. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nov013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Niclou SP. Gauging heterogeneity in primary versus recurrent glioblastoma. Neuro-Oncology. 2015;17:907–9. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nov078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamahara T, Numa Y, Oishi T, Kawaguchi T, Seno T, Asai A, et al. Morphological and flow cytometric analysis of cell infiltration in glioblastoma: a comparison of autopsy brain and neuroimaging. Brain Tumor Pathology. 2010;27:81–7. doi: 10.1007/s10014-010-0275-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Akbari H, Macyszyn L, Da X, Wolf R, Bilello M, Verma R, et al. Pattern analysis of dynamic susceptibility contrast-enhanced MR imaging demonstrates peritumoral tissue heterogeneity. Radiology. 2014;273:502–10. doi: 10.1148/radiol.14132458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith SM, Brady JM. SUSAN - a new approach to low level image processing. International Journal of Computer Vision. 1997;23:45–78. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sled J, Zijdenbos A, Evans A. A nonparametric method for automatic correction of intensity nonuniformity in MRI data. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging. 1998;17:87–97. doi: 10.1109/42.668698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jenkinson M, Beckmann CF, Behrens TE, Woolrich MW. FSL. NeuroImage. 2012;62:782–90. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bhattacharyya A. On a measure of divergence between two statistical populations defined by their probability distributions. Bulletin of the Calcutta Mathematical Society. 1943;35:99–109. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kailath T. The Divergence and Bhattacharyya Distance Measures in Signal Selection. IEEE Transactions on Communication Technology. 1967;15:52–60. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lal A, Glazer CA, Martinson HM, Friedman HS, Archer GE, Sampson JH, et al. Mutant epidermal growth factor receptor up-regulates molecular effectors of tumor invasion. Cancer Research. 2002;62:3335–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gaonkar B, Davatzikos C. Analytic estimation of statistical significance maps for support vector machine based multi-variate image analysis and classification. NeuroImage. 2013;78:270–83. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.03.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Petrecca K, Guiot M-C, Panet-Raymond V, Souhami L. Failure pattern following complete resection plus radiotherapy and temozolomide is at the resection margin in patients with glioblastoma. Journal of Neurooncology. 2013;111:19–23. doi: 10.1007/s11060-012-0983-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jain R, Poisson LM, Gutman D, Scarpace L, Hwang SN, Holder CA, et al. Outcome Prediction in Patients with Glioblastoma by Using Imaging, Clinical, and Genomic Biomarkers: Focus on the Nonenhancing Component of the Tumor. Radiology. 2014;272:484–93. doi: 10.1148/radiol.14131691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kerbel RS. Tumor angiogenesis: past, present and the near future. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:505–15. doi: 10.1093/carcin/21.3.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bullitt E, Zeng D, Gerig G, Aylward S, Joshi S, Smith JK, et al. Vessel tortuosity and brain tumor malignancy: a blinded study. Acad Radiol. 2005;12:1232–40. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2005.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Boockvar JA, Kapitonov D, Kapoor G, Schouten J, Counelis GJ, Bogler O, et al. Constitutive EGFR signaling confers a motile phenotype to neural stem cells. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2003;24:1116–30. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2003.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Arevalo-Perez J, Thomas AA, Kaley T, Lyo J, Peck KK, Holodny AI, et al. T1-Weighted Dynamic Contrast-Enhanced MRI as a Noninvasive Biomarker of Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor vIII Status. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2015;36:2256–61. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A4484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gevaert O, Mitchell LA, Achrol AS, Xu J, Echegaray S, Steinberg GK, et al. Glioblastoma multiforme: exploratory radiogenomic analysis by using quantitative image features. Radiology. 2014;273:168–74. doi: 10.1148/radiol.14131731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ellingson BM. Radiogenomics and imaging phenotypes in glioblastoma: novel observations and correlation with molecular characteristics. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2015;15:506. doi: 10.1007/s11910-014-0506-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Batmanghelich N, Dalca A, Quon G, Sabuncu M, Golland P. Probabilistic Modeling of Imaging, Genetics and Diagnosis. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2016 doi: 10.1109/TMI.2016.2527784. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Johnson BE, Mazor T, Hong C, Barnes M, Aihara K, McLean CY, et al. Mutational Analysis Reveals the Origin and Therapy-Driven Evolution of Recurrent Glioma. Science. 2014;343:189–93. doi: 10.1126/science.1239947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vecchio CAD, Giacomini CP, Vogel H, Jensen KC, Florio T, Merlo A, et al. EGFRvIII gene rearrangement is an early event in glioblastoma tumorigenesis and expression defines a hierarchy modulated by epigenetic mechanisms. Oncogene. 2013;32:2670–81. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gill BJ, Pisapia DJ, Malone HR, Goldstein H, Lei L, Sonabend A, et al. MRI-localized biopsies reveal subtype-specific differences in molecular and cellular composition at the margins of glioblastoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:12550–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1405839111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.