ABSTRACT

Cadmium is a highly poisonous metal and is classified as a human carcinogen. While its toxicity is undisputed, the underlying in vivo molecular mechanisms are not fully understood. Here, we demonstrate that cadmium induces aggregation of cytosolic proteins in living Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells. Cadmium primarily targets proteins in the process of synthesis or folding, probably by interacting with exposed thiol groups in not-yet-folded proteins. On the basis of in vitro and in vivo data, we show that cadmium-aggregated proteins form seeds that increase the misfolding of other proteins. Cells that cannot efficiently protect the proteome from cadmium-induced aggregation or clear the cytosol of protein aggregates are sensitized to cadmium. Thus, protein aggregation may contribute to cadmium toxicity. This is the first report on how cadmium causes misfolding and aggregation of cytosolic proteins in vivo. The proposed mechanism might explain not only the molecular basis of the toxic effects of cadmium but also the suggested role of this poisonous metal in the pathogenesis of certain protein-folding disorders.

KEYWORDS: metal toxicity, protein aggregation, protein degradation, protein folding, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, cadmium, zinc

INTRODUCTION

Proteins control nearly every biological process in living cells. In the cell, most proteins must first fold into a narrow set of three-dimensional structures with distinct biological functions, defined as their native fold. However, the process of folding is prone to errors and may result in protein misfolding and aggregation. Misfolded proteins are cytotoxic, and accumulation of aggregated proteins is a hallmark of several neurodegenerative diseases and age-related disorders, such as Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases. Various environmental stress conditions, such as heat and oxidative stress, also generate aberrant protein conformations and aggregation and thereby impact cell viability, aging, and disease processes (1–4). Xenobiotic metals are widespread in nature, and accumulating evidence indicates that metals induce and accelerate the progression of certain neurodegenerative diseases caused by aberrant protein folding (5–9). However, the molecular mechanisms that contribute to metal toxicity and pathogenesis in living organisms are poorly understood.

Cadmium is ubiquitously present as an environmental pollutant, and exposure to this highly poisonous metal is of considerable public health concern. Cadmium is classified as a human carcinogen and has been shown to damage kidney and lung, to affect bone metabolism and the cardiovascular system, and to cause neurotoxicity (5, 10). At the cellular level, cadmium toxicity is attributed to several mechanisms; it may interfere with redox processes and cause oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation, disturb homeostasis of nutritional metals, impair DNA repair mechanisms and cause DNA damage, and perturb protein function and activity (10–12). At the molecular level, these toxic effects have until now been ascribed to its interaction with specific, particularly susceptible native proteins; cadmium may bind to free thiol groups in proteins; displace essential metal ions, like zinc and calcium, in metalloproteins; or catalyze oxidative modifications of amino acid side chains (9, 10). There are many reports of cadmium binding to native proteins, including transcription factors and DNA repair enzymes; however, most of these studies used purified proteins and in vitro binding assays (10). Thus, the importance of this mode of action for in vivo toxicity is largely unknown.

Recent studies have indicated that cadmium interferes with protein folding. First, cadmium was shown to strongly inhibit refolding of chemically denatured proteins in vitro (13). Second, cadmium-exposed Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells accumulated aggregated proteins in vivo (14). Third, cadmium-exposed yeast (15, 16) and mammalian (17, 18) cells activated the unfolded-protein response, indicating that unfolded proteins accumulate in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). Together, these reports suggest that cadmium affects protein homeostasis by interfering with protein folding. However, the mechanistic details of how cadmium affects protein folding in the cytosol and the ER have remained elusive.

Here, we demonstrate that cadmium triggers aggregation of cytosolic proteins in yeast (S. cerevisiae) cells primarily by targeting proteins in the process of synthesis or folding. We provide evidence that cadmium-aggregated proteins form seeds that increase the misfolding of other proteins. Cells that cannot effectively protect the proteome from cadmium-induced aggregation or clear the cytosol of protein aggregates are sensitized to cadmium, suggesting that protein aggregation contributes to the toxicity of the metal.

RESULTS

Cadmium causes aggregation of cytosolic proteins in vivo.

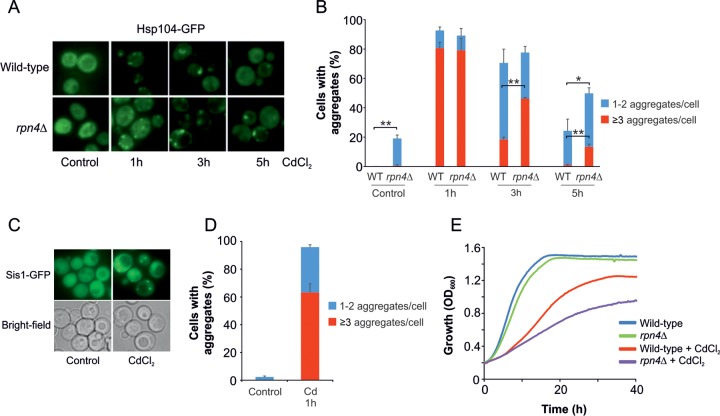

To investigate how cadmium affects the proteome in living yeast cells, we monitored the subcellular distribution of a green fluorescent protein (GFP)-tagged version of the molecular chaperone Hsp104 (Hsp104-GFP). Hsp104 is an orthologue of bacterial ClpB that, together with Hsp70, functions as a disaggregase (19–21), and Hsp104-GFP has been extensively used as a marker for cytosolic protein aggregation in S. cerevisiae (14, 22, 23). In untreated cells, Hsp104-GFP was evenly distributed throughout the cytosol. After 1 h of exposure to 50 μM cadmium chloride (CdCl2), Hsp104-GFP relocalized to distinct cytosolic foci, with the majority of cells containing several foci (Fig. 1A and B). Such Hsp104-GFP foci have previously been shown to correspond to sites of protein aggregates (24, 25). The Hsp40 protein Sis1 is an essential Hsp70 cochaperone (26) and an important player in the sorting and degradation of misfolded cytosolic proteins in yeast (27, 28). Sis1 has been shown to move to and associate with aggregation-prone proteins under conditions of proteotoxic stress (27–29). We transformed yeast cells with a Sis1-GFP plasmid and monitored the subcellular distribution of the fusion protein in response to cadmium exposure. As for Hsp104-GFP, 1 h of exposure to 50 μM CdCl2 resulted in the redistribution of Sis1-GFP to distinct cytosolic foci, with the majority of cells containing several foci (Fig. 1C and D). Together, these results suggest that cadmium induces protein aggregation in living yeast cells. Whether cadmium-induced protein aggregates are sequestered into specific subcellular deposition sites (23, 30) remains to be investigated. We noted that at this cadmium concentration, protein aggregation was time dependent. After 1 h of exposure, nearly all cells contained Hsp104-GFP foci. However, the total fraction of cells with Hsp104-GFP foci decreased over time (Fig. 1A and B). Likewise, the proportion of cells containing ≥3 Hsp104-GFP foci/cell was higher after 1 h of cadmium exposure than at the later time points (Fig. 1B). We verified that 50 μM CdCl2 did not affect cell viability during the 5-hour experimental time course (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material), suggesting an active aggregate dissolution or clearance mechanism.

FIG 1.

Cadmium induces aggregation of cytosolic proteins in vivo. (A) Hsp104-GFP localization was monitored in living wild-type and rpn4Δ cells by fluorescence microscopy before and after exposure to 50 μM CdCl2. Representative images are shown. (B) Quantification of protein aggregation. Hsp104-GFP distribution was scored in wild-type and rpn4Δ cells as for panel A. The fractions of cells containing 1 or 2 aggregates/cell and ≥3 aggregates/cell were determined by visual inspection of 90 to 167 (for wild-type) and 102 to 164 (for rpn4Δ) cells per condition and time point. The error bars represent standard deviations (SD) from three independent biological replicates (n = 3). The error bars on the blue bars concern the total fractions of cells with aggregates, while those on the red bars concern the fractions of cells with ≥3 aggregates/cell. Statistical analyses were performed by Student's t test, and significant differences are indicated; *, P < 0.05, and **, P < 0.005. (C) Sis1-GFP localization was monitored in living wild-type cells by fluorescence microscopy before and after exposure to 50 μM CdCl2. Representative images are shown. (D) Quantification of protein aggregation. Sis1-GFP distribution was scored in wild-type cells as in panel C. The fractions of cells containing 1 or 2 aggregates/cell and ≥3 aggregates/cell were determined by visual inspection of 95 to 151 cells per condition and time point. The error bars represent SD from three independent biological replicates. The error bars on the blue bars concern the total fractions of cells with aggregates, while those on the red bars concern the fractions of cells with ≥3 aggregates/cell. Statistical analyses were performed by Student's t test, and significant differences are indicated; *, P < 0.05, and **, P < 0.005. (E) Growth assay. Growth of cells was monitored by measuring the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) using a microcultivation approach. CdCl2 (50 μM) was added to the cultures as indicated. Each curve represents the average of at least five repetitions.

The ubiquitin-proteasome system has been implicated in protein quality control during cadmium exposure (31) and has been reported to be required for cadmium resistance (32). To assess the role of this degradation pathway in the clearance of cadmium-induced protein aggregates, we monitored Hsp104-GFP distribution in cells that lack Rpn4, a transcriptional regulator of proteasomal gene expression (33). While formation of Hsp104-GFP foci/aggregates was similar in wild-type and rpn4Δ cells, aggregate clearance was strongly affected in the mutant; a higher proportion of rpn4Δ cells had multiple aggregates, and rpn4Δ cells showed a delay in overall aggregate clearance compared to the wild type (Fig. 1A and B). Thus, cells with diminished proteasomal activity are deficient in the clearance of cadmium-induced aggregates. While the viability of rpn4Δ cells was unaffected by cadmium (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material), growth of cells lacking RPN4 was more severely affected by cadmium than that of wild-type cells (Fig. 1E). Thus, proteasomal clearance of aggregated proteins may contribute to cadmium resistance.

Cadmium targets nascent proteins for aggregation.

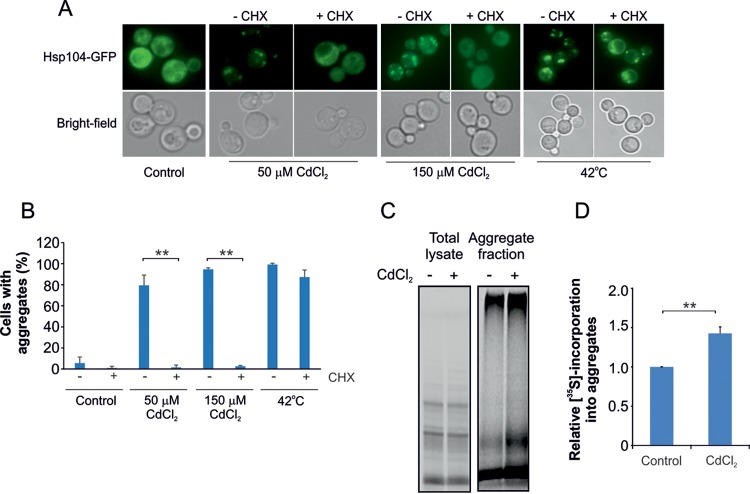

We next examined whether cadmium targets nascent (not yet folded) or native (folded) cellular proteins for aggregation. We treated cells with cadmium and the protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide (CHX), added either separately or together, and monitored the intracellular distribution of Hsp104-GFP. At 50 μM CdCl2, protein aggregation was fully inhibited when translation was blocked (Fig. 2A and B). Likewise, CHX strongly inhibited protein aggregation when cells were exposed to 150 μM CdCl2 (Fig. 2A and B), a concentration that causes more prominent protein aggregation and growth inhibition than 50 μM CdCl2 (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). Importantly, CHX did not prevent protein aggregation/Hsp104-GFP focus formation in response to heat stress (1 h at 42°C) (Fig. 2A and B), a condition that causes thermal unfolding and aggregation of native proteins (34). These findings suggest that cadmium primarily targets nascent proteins for aggregation. To corroborate this interpretation, we labeled newly synthesized proteins by adding [35S]methionine to exponentially growing cells during a 5-min pulse. The cells were either untreated or exposed to 150 μM CdCl2 for 30 min before the [35S]methionine pulse, translation was stopped by adding CHX immediately after the pulse, and aggregated proteins were then isolated by sedimentation. Equal amounts of radioactivity were incorporated into newly synthesized proteins in the total lysates of untreated and cadmium-exposed cells (Fig. 2C). In contrast, a higher fraction of radioactivity was present in the aggregate fraction of cadmium-exposed cells than in unexposed cells (Fig. 2C). Quantification of the 35S-containing material showed an ∼40% increase in aggregation of newly synthesized proteins during cadmium exposure compared to unexposed cells (Fig. 2D). Note that cells exposed to cadmium decrease protein synthesis and redirect sulfur flux to increase glutathione (GSH) biosynthesis (35, 36). Therefore, the effect of cadmium on nascent-protein misfolding and aggregation is probably higher than revealed by this experiment.

FIG 2.

Cadmium targets nascent proteins for aggregation. (A) Inhibition of translation attenuates cadmium-induced aggregate formation. Hsp104-GFP localization was monitored in wild-type cells before and after 1-h exposure to 50 μM CdCl2, 150 μM CdCl2, or 42°C in the absence or presence of 0.1 mg/ml CHX. Representative images are shown. (B) Quantification of protein aggregation. Hsp104-GFP distribution was scored in wild-type cells treated as for panel A. The fractions of cells containing aggregates were determined by visual inspection of 100 to 286 cells per condition. The error bars represent SD from three independent biological replicates. Statistical analyses were performed by Student's t test, and significant differences are indicated; **, P < 0.005. (C) Cadmium enhances aggregation of newly synthesized proteins. Untreated and cadmium-exposed cells were pulsed for 5 min with [35S]methionine to label newly synthesized proteins, and aggregated proteins were isolated by sedimentation. Before adding [35S]methionine, the cells were preexposed to 150 μM CdCl2 for 30 min; 20 μg of the total protein fractions and the isolated aggregate fractions were separated by SDS-PAGE and visualized by autoradiography. (D) Incorporation of 35S-labeled material into the various fractions was quantified by densitometric analysis. The fraction of 35S incorporation into aggregates versus the total 35S label incorporation was set to 1 for untreated cells and compared to that of cadmium-exposed cells. The error bars represent SD from three independent biological replicates (n = 3). Statistical analyses were performed by Student's t test, and significant differences are indicated; **, P < 0.005.

Zinc protects nascent polypeptides from cadmium-induced aggregation.

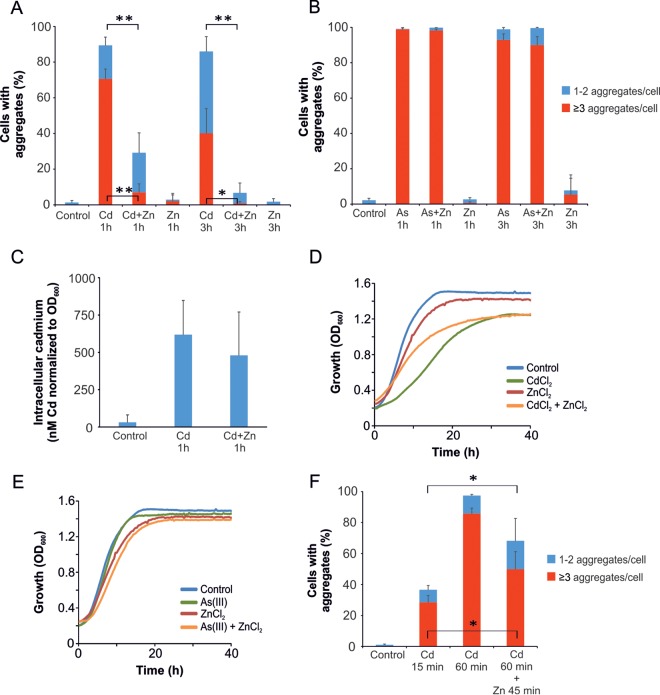

Cadmium can perturb homeostasis of nutritional metal ions and displace essential metal ions, like zinc and calcium, in metalloproteins (10). For some proteins, cadmium-zinc exchange has been shown to alter structure and activity (37). To test whether addition of zinc affects cadmium-induced protein aggregation, we exposed yeast cells to 50 μM CdCl2 with or without addition of 7.5 mM zinc chloride (ZnCl2) and monitored protein aggregation/Hsp104-GFP focus formation. Note that the cells were grown in a medium that contained 1.4 mM zinc and were therefore adapted to high zinc levels. When cadmium and zinc were added simultaneously to yeast cultures, zinc strongly attenuated cadmium-induced protein aggregation (Fig. 3A). Importantly, the addition of 7.5 mM ZnCl2 did not prevent intracellular cadmium accumulation (Fig. 3C) and affected the growth of the yeast cells to only a minor extent (Fig. 3D). In contrast, zinc addition clearly improved the growth of cadmium-exposed cells (Fig. 3D). Thus, our data suggest that zinc protects nascent polypeptides from cadmium-induced aggregation and alleviates cadmium toxicity. We previously demonstrated that arsenite [As(III)] is a potent inducer of protein aggregation (14). In a control experiment, zinc did not affect As(III)-induced protein aggregation (Fig. 3B). Moreover, the presence of zinc slightly aggravated the As(III) sensitivity of cells (Fig. 3E). Since both cadmium and As(III) trigger cytosolic protein aggregation, it is unlikely that the protective effect of zinc during cadmium exposure is due to a general impact of zinc on, e.g., translation or induction of the heat shock response. Instead, we propose that cadmium may interfere with the folding of zinc-dependent proteins (see Discussion).

FIG 3.

Zinc attenuates cadmium-induced protein aggregation and toxicity. (A) Zinc inhibits cadmium-induced protein aggregation. Hsp104-GFP localization was monitored in living wild-type cells that were untreated or exposed to 50 μM CdCl2 in the absence or presence of 7.5 mM ZnCl2 added at the same time as CdCl2. Samples were taken at the indicated time points, and protein aggregation levels were quantified. The fractions of cells containing 1 or 2 aggregates/cell and ≥3 aggregates/cell were determined by visual inspection of 99 to 173 cells per condition. (B) Zinc does not inhibit As(III)-induced protein aggregation. Hsp104-GFP localization was monitored and quantified as described above in cells exposed to 0.5 mM As(III). The fractions of cells containing 1 or 2 aggregates/cell and ≥3 aggregates/cell were determined by visual inspection of 107 to 172 cells per condition. (C) Intracellular cadmium. Intracellular cadmium levels were measured in untreated cells (control) and in cells exposed to 50 μM CdCl2 in the absence or presence of 7.5 mM ZnCl2 added at the same time as CdCl2. The measured concentrations were normalized to the OD600 of each sample. The values represent averages from eight independent experiments. The error bars represent SD. (D) Zinc addition improves growth of cadmium-exposed cells. Growth of wild-type cells was monitored by measuring the OD600 using a microcultivation approach. Fifty micromolar CdCl2 and/or 7.5 mM ZnCl2 was added as indicated. Each curve represents the average of six repetitions. (E) Zinc addition aggravates the growth of As(III)-exposed cells. Growth of wild-type cells was monitored as described above; 0.5 mM As(III) and/or 7.5 mM ZnCl2 was added as indicated. Each curve represents the average of six repetitions. (F) Zinc does not prevent further aggregation once primary aggregates have been formed. Hsp104-GFP localization was monitored in living wild-type cells that were untreated or had been exposed to 50 μM CdCl2 in the absence or presence of 7.5 mM ZnCl2 added 15 min after CdCl2. Samples were taken at the indicated time points, and protein aggregation levels were quantified. The fractions of cells containing 1 or 2 aggregates/cell and ≥3 aggregates/cell were determined by visual inspection of 124 to 168 cells per condition. (A, B, and F) The error bars represent SD from three independent biological replicates. The error bars on the blue bars concern the total fractions of cells with aggregates, while those on the red bars concern the fractions of cells with ≥3 aggregates/cell. Statistical analyses were performed by Student's t test, and significant differences are indicated; *, P < 0.05, and **, P < 0.005.

We next asked if zinc added to cells at a time point at which cadmium-induced aggregates had already been formed could prevent further misfolding. For this, we first incubated cells with 50 μM CdCl2 for 15 min to induce protein aggregation (∼35% of cells had aggregates; ∼30% had ≥3 aggregates/cell) and then added 7.5 mM zinc. Interestingly, the fraction of cells with aggregates/Hsp104-GFP foci continued to increase in the presence of zinc (Fig. 3F); ∼70% of the cells had aggregates, and ∼50% had ≥3 aggregates/cell in the presence of zinc. This is in clear contrast to when zinc and cadmium were added at the same time, a treatment that strongly abrogated cadmium-induced protein aggregation (Fig. 3A). Thus, zinc cannot prevent further aggregation once primary aggregates induced by cadmium have been formed.

Cadmium is not a strong inhibitor of cytosolic chaperone action in vivo.

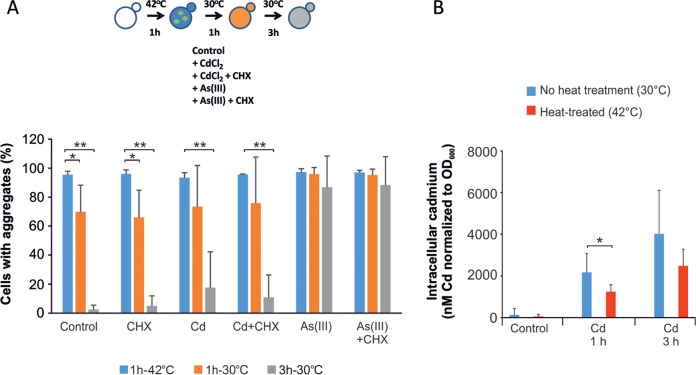

We have previously shown that cadmium inhibits chaperone-assisted refolding of chemically denatured and heat-denatured proteins in vitro using the DnaK/DnaJ/GrpE (KJE) system of Escherichia coli (13). To test whether cadmium interferes with chaperone action in vivo, we performed an aggregate clearance assay in living yeast cells. For this, we first induced protein aggregation/Hsp104-GFP focus formation by heat treatment at 42°C for 1 h and then lowered the temperature to 30°C and monitored the capacity of the cells to clear the cytosol from aggregates in the absence or presence of cadmium (Fig. 4). To prevent de novo formation of cadmium-induced aggregates, we added CHX as indicated. Three hours after the shift back to 30°C, most cells had cleared the cytosol of heat-induced aggregates (Fig. 4A). Unexpectedly, the cells were highly efficient in cytosolic aggregate clearance despite the presence of cadmium. This finding was surprising given that cadmium is a potent inhibitor of chaperone action in vitro (13). In contrast to cadmium, As(III) strongly compromised the aggregate clearance capacity of the cells (Fig. 4A), consistent with our previous data (14). To ensure that the absence of impact on aggregate clearance was not caused by impaired entry of cadmium into heat-exposed cells, we measured intracellular cadmium levels under experimental conditions identical to those described above; cadmium was added to cells after a 1-h pretreatment at 42°C or to cells continuously grown at 30°C. The intracellular cadmium levels increased over time irrespective of whether the cells were heat treated. We noted, though, that cells that were not heat treated accumulated more cadmium after 1 h than the heat-exposed cells, while at the 3-h time point, the difference was nonsignificant (Fig. 4B). The observed difference in intracellular cadmium at the early time point cannot explain the complete absence of impact of cadmium on aggregate clearance. These data suggest that cadmium does not interfere with cytosolic chaperone action in living cells. Alternatively, proteasomal degradation might be the dominant process determining the aggregate lifetime (Fig. 1), masking the effect of cadmium on chaperone-assisted refolding in vivo. Nevertheless, in clear contrast to As(III), cadmium does not appear to be a potent inhibitor of cytosolic chaperone activity in living yeast cells.

FIG 4.

Cadmium does not interfere with chaperone action in vivo. (A) Clearance of heat-induced aggregates. Cells were exposed to 42°C for 1 h to induce protein aggregation and then placed at 30°C. Aggregate clearance was monitored in the absence and presence of 50 μM CdCl2, 0.5 mM As(III), and 0.1 mg/ml CHX as indicated. The percentage of cells containing aggregates was determined by visual inspection of 88 to 414 cells per condition and time point. The error bars represent SD from three independent biological replicates. Statistical analyses were performed by Student's t test, and significant differences are indicated; *, P < 0.05, and **, P < 0.005. (B) Intracellular cadmium. Intracellular cadmium levels were measured under the same conditions as for panel A; cells were pretreated at 42°C for 1 h (heat) or at 30°C (control) before exposure to 50 μM CdCl2 and then placed at 30°C. Samples were taken at the indicated time points. The measured concentrations were normalized to the OD600 of each sample. The values represent averages from eight individual experiments. The error bars represent SD. Statistical analyses were performed by Student's t test, and significant differences are indicated; *, P < 0.05.

Cadmium complexation and vacuolar sequestration may protect cytosolic proteins from aggregating.

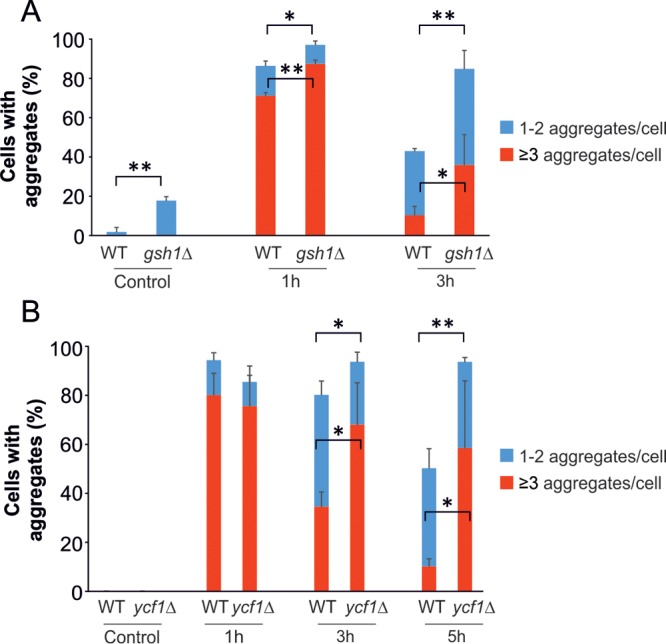

We noted that while yeast cells clear their cytosol of cadmium-induced aggregates (Fig. 1), intracellular cadmium levels actually rise (Fig. 4B). Yeast employs various defense systems to evade cadmium toxicity, including a large increase in intracellular GSH levels (35, 36) and increased expression of the YCF1 gene, encoding an ABC transporter that catalyzes the sequestration of the cadmium-diglutathione complex [Cd(GS)2] into vacuoles (38). We tested whether cellular GSH levels and the cadmium sequestration capacity of the cells had an impact on protein aggregation. To approach this, we first monitored cadmium-induced protein aggregation in wild-type cells and in a gsh1Δ mutant that cannot synthesize GSH. For this experiment, we grew cells in yeast-peptone-dextrose (YPD) medium that contained GSH, since gsh1Δ cells are unable to proliferate unless GSH is provided exogenously (39). The gsh1Δ mutant accumulated more aggregates/Hsp104-GFP foci and showed a strong delay in aggregate clearance compared to the wild type (Fig. 5A), suggesting that GSH protects cytosolic proteins from cadmium-induced aggregation. Since we used medium containing GSH in this assay, the observed difference in protein aggregation most probably underestimates the importance of GSH in counteracting protein aggregation. Alternatively, insufficient cellular GSH levels might have a negative impact on aggregate clearance pathways.

FIG 5.

Cadmium complexation and vacuolar sequestration protect cytosolic proteins from aggregating. (A) Protein aggregation in cells deficient in GSH biosynthesis (gsh1Δ). Hsp104-GFP distribution was scored in wild-type and gsh1Δ cells before and after exposure to 50 μM CdCl2. The percentage of cells containing aggregates was determined by visual inspection of 100 to 163 (for wild-type) and 100 to 174 (for gsh1Δ) cells per condition and time point. (B) Protein aggregation in cells deficient in vacuolar sequestration (ycf1Δ). Hsp104-GFP distribution was scored in wild-type and ycf1Δ cells before and after exposure to 50 μM CdCl2. The percentage of cells containing aggregates was determined by visual inspection of 99 to 157 (for wild-type) and 96 to 151 (for ycf1Δ) cells per condition and time point. (A and B) The error bars represent SD from three independent biological replicates. The error bars on the blue bars concern the total fractions of cells with aggregates, while those on the red bars concern the fractions of cells with ≥3 aggregates/cell. Statistical analyses were performed by Student's t test, and significant differences are indicated; *, P < 0.05, and **, P < 0.005.

We next monitored protein aggregation in wild-type and ycf1Δ cells. Since the ycf1Δ mutant is defective in transport of Cd(GS)2 into the vacuole (38), it should have an elevated cytosolic cadmium content and a higher level of protein aggregation. Indeed, the ycf1Δ mutant contained more protein aggregates than wild-type cells after 3 h and 5 h of cadmium exposure (Fig. 5B). Hence, the observation that the total intracellular cadmium levels increase while the aggregation levels diminish is probably explained by the fact that cells increase their cadmium chelation (by GSH) and sequestration (by Ycf1) capacity during cadmium exposure. This response seems important for resistance, because gsh1Δ and ycf1Δ mutants were previously shown to be cadmium sensitive (40, 41). We conclude that cadmium complexation and vacuolar sequestration mechanisms may protect cytosolic proteins from aggregation and contribute to cadmium resistance.

Cadmium-induced aggregates can act as seeds to induce aggregation of other proteins.

Protein aggregates can act as seeds and inhibit the native folding of other stress-labile proteins, leading to their inactivation and aggregation (42). Moreover, aggregate size and structure can influence the seeding capacity and toxicity of primary aggregates. To estimate the sizes of cadmium-induced protein aggregates, we prepared stable aggregates of luciferase by incubating the protein with cadmium (see Materials and Methods and Fig. S2 in the supplemental material) followed by size exclusion chromatography (see Fig. S5 in the supplemental material). The presence of cadmium strongly affected the aggregation state of a 4-fold molar excess of luciferase polypeptides that corresponded to over 2,000-fold more protein mass than cadmium mass. Sixty-seven percent of the luciferase was found to migrate as soluble inactive oligomers with apparent molecular masses ranging between 300 and 400 kDa (see Fig. S5, peak B), while a smaller fraction of luciferase (33%) refolded spontaneously to its native form (see Fig. S5, peak A). In contrast, heat-denatured luciferase (see Materials and Methods and Fig. S1 in the supplemental material) formed large insoluble aggregates that appeared in the void volume (see Fig. S5, peak C). Thus, under the conditions described here, cadmium-induced luciferase aggregates are smaller than heat-induced luciferase aggregates.

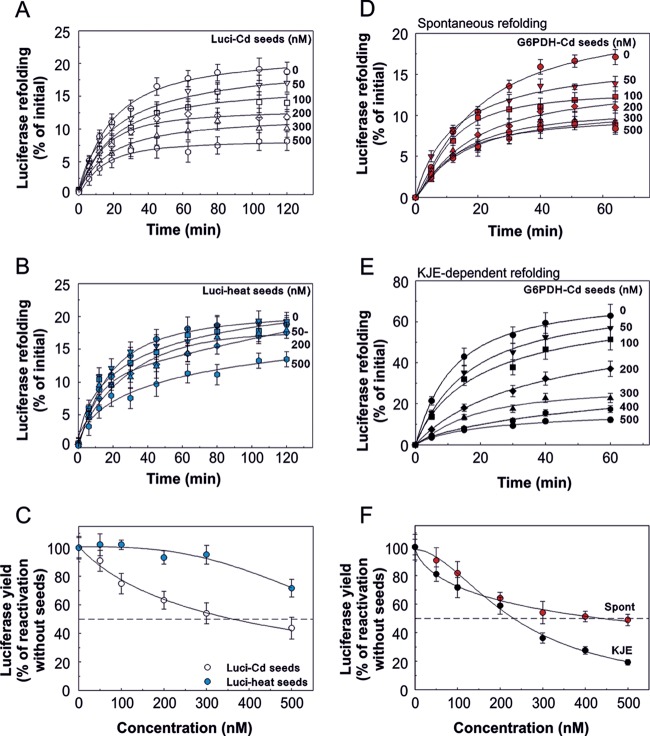

We next used these aggregates to study their seeding effect, i.e., their impact on the folding/misfolding and partitioning of chemically denatured luciferase. Increasing concentrations of cadmium-treated luciferase (Luci-Cd) (Fig. 6A) and heat-treated luciferase (Luci-heat) (Fig. 6B) seeds inhibited the spontaneous refolding of chemically denatured luciferase. Luci-heat seeds were not particularly effective inhibitors of native luciferase refolding; at 500 nM, only 30% inhibition of total refolding was observed, while lower concentrations had an insignificant impact on refolding (Fig. 6B and C). Importantly, Luci-Cd seeds caused 50% inhibition of luciferase refolding at a significantly lower concentration (350 nM) than Luci-heat seeds (Fig. 6B and C). Thus, Luci-Cd seeds are effective inhibitors of protein folding, possibly owing to their small size entailing a commensurately larger total surface.

FIG 6.

Seeding capacities of cadmium-induced aggregates. (A) Inhibitory effects of cadmium-induced luciferase aggregates on luciferase refolding. Refolding of chemically denatured luciferase at 25°C was initiated by 1:50 dilution (final concentration of luciferase, 350 nM) with the refolding buffer (50 mM Tris-acetate, 100 mM potassium perchlorate, 15 mM magnesium acetate, pH 7.5) containing the indicated concentrations of Luci-Cd seeds prepared as described in Materials and Methods. Luciferase activity was measured in samples of the refolding solution at the indicated times. (B) Inhibitory effects of heat-induced luciferase aggregates on luciferase refolding were measured as for Luci-Cd seeds in panel A. (C) Luciferase activity after 120 min of refolding in the presence of increasing concentrations of Luci-heat seeds (blue circles) or Luci-Cd seeds (white circles). (D) Inhibitory effects of cadmium-induced aggregates of G6PDH on spontaneous luciferase refolding. Refolding of chemically denatured luciferase at 25°C was initiated through 1:50 dilution (final concentration of luciferase, 350 nM) with refolding buffer (50 mM Tris acetate, 100 mM potassium perchlorate, 15 mM magnesium acetate, pH 7.5) containing the indicated concentrations of G6PDH aggregates prepared in the presence of cadmium. (E) Inhibitory effects of cadmium-induced aggregates of G6PDH on chaperone-assisted luciferase refolding. A refolding assay was performed as described above with the KJE chaperone system (3.5 μM DnaK, 0.7 μM DnaJ, 1.4 μM GrpE, and 5 mM ATP) at 25°C. (F) Luciferase activity after 60 min of refolding without (spontaneous [Spont]; red circles) or with (black circles) KJE chaperones in the presence of increasing concentrations of Cd-G6PDH seeds. (A to F) The error bars represent the standard errors of the mean (SEM) from three independent experiments.

The KJE system of E. coli is a bacterial ATP-fueled chaperone system that can unfold stable misfolded and aggregated proteins and convert them into natively folded polypeptides (43). To address how protein aggregate seeds affect chaperone-assisted refolding, we prepared stable aggregates of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PDH) and measured the effect of G6PDH-Cd seeds on KJE-assisted luciferase refolding. While the presence of G6PDH seeds did not interfere with the enzymatic activity of native luciferase (data not shown), it clearly affected the spontaneous refolding of luciferase in a dose-dependent manner, causing a 50% decrease in the yield of refolding at 460 nM (Fig. 6D). In the presence of KJE, a 50% decrease in the yield of refolding was observed already at 240 nM G6PDH-Cd seeds (Fig. 6E and F). Thus, chaperone-assisted refolding appears more susceptible to Cd seeds than spontaneous refolding. We conclude that cadmium-aggregated species have a strong inhibitory effect on de novo folding of proteins that have not encountered any metal during refolding. Hence, cadmium-aggregated species may act as seeds, promoting the misfolding and aggregation of other proteins.

DISCUSSION

Cadmium is a highly poisonous and carcinogenic metal, but the molecular mechanisms underlying its in vivo toxicity are not fully understood. Here, we report a novel mode of its toxic action: cadmium-induced accumulation of aggregated cytosolic proteins in vivo.

Cadmium targets nascent proteins for aggregation in vivo.

We demonstrate that cadmium triggers aggregation of cytosolic proteins in vivo primarily by targeting nascent proteins (Fig. 1 and 2). First, inhibition of translation (by addition of CHX) prevented cadmium-induced protein aggregation, whereas heat-induced unfolding and aggregation of native proteins was not inhibited by CHX. Second, cadmium-exposed cells incorporated more 35S-pulse-labeled material (i.e., newly synthesized proteins) into the aggregate fraction than unexposed cells. The notion that cadmium primarily targets nascent proteins rather than native proteins for aggregation is supported by previous in vitro assays showing that cadmium efficiently inhibits spontaneous refolding of chemically denatured luciferase while native luciferase is not particularly affected by the metal (13).

How does cadmium impair protein folding? In vitro assays indicate that cadmium inhibits spontaneous refolding of proteins by forming high-affinity multidentate metal-protein complexes (13). Our current in vivo data suggest that chaperone activity is largely unaffected by cadmium, as cadmium-exposed cells effectively cleared the cytosol of heat-induced protein aggregates (Fig. 4). This finding was unexpected, given that cadmium had been found to inhibit chaperone-mediated refolding of chemically denatured luciferase in vitro (13). However, those chaperone-assisted refolding assays had been performed with the E. coli proteins DnaK, DnaJ, and GrpE. When DnaJ was replaced with the homologous CbpA protein, refolding of chemically denatured luciferase was not affected by cadmium (13). Unlike CbpA, DnaJ contains a cysteine-rich zinc finger domain that acts as a thioredoxin-like protein disulfide isomerase (44), and this zinc-binding domain is likely to be preferentially targeted by cadmium for inhibition (45). A total of 16 proteins are annotated in the S. cerevisiae genome as DnaJ-like chaperones or as possessing a DnaJ-like domain (Saccharomyces Genome Database [SGD] [http://www.yeastgenome.org]). Five of these (Apj1, Mdj1, Scj1, Xdj1, and Ydj1) contain C4-type zinc finger domains characterized by four cysteine residues. Since cadmium preferentially interacts with sulfur-containing ligands, these proteins may potentially be targeted by cadmium for inhibition in vivo. Of these, only Ydj1 is localized to the cytosol and thus might be targeted by cadmium. Why, then, is 50 μM CdCl2, as used in our study, insufficient to strongly inhibit cytosolic chaperone activity in vivo even though it is sufficient to cause protein aggregation and toxicity? Most likely, the cellular pool of thiol-containing molecules outnumbers the pool of cadmium molecules in the cytosol, thereby protecting Ydj1 and/or other chaperones from cadmium binding and inhibition. This notion is supported by the fact that the intracellular GSH concentration in yeast cells is about 1 to 2 mM in the absence of stress and increases to about 10 mM during cadmium exposure (36) and by our observation that GSH contributes to keeping cadmium-induced aggregation levels low (Fig. 5). Moreover, native Ydj1 is possibly less sensitive to cadmium than nascent Ydj1. Although our data suggest that chaperone-assisted refolding is not strongly affected by cadmium in vivo, we cannot exclude the possibility that efficient proteasomal degradation masks the effect of cadmium on chaperone action. The relative contributions of the two processes (chaperone-assisted refolding and proteasomal degradation) to aggregate clearance remain to be elucidated.

Cadmium is known to interfere with zinc-binding proteins (10, 37), and it is estimated that 8 to 10% of yeast and human proteomes consist of zinc-binding proteins (46). Interestingly, we found that zinc, when added together with cadmium, strongly inhibited cadmium-induced protein aggregation (Fig. 3). Zinc and cadmium compete for binding to sulfur ligands, but cadmium is considerably more thiophilic than zinc. Thus, to effectively compete with zinc for binding to a C4 zinc-binding site, the cadmium concentration needs to be only 1/1,000 of that of zinc (10). In our assays, we used 7.5 mM zinc and 50 μM cadmium, a difference of 2 orders of magnitude. Hence, at the concentrations used here, cadmium might interact with exposed thiol groups and replace zinc during folding of C4 zinc-binding proteins, thereby promoting their misfolding and aggregation. While it has previously been shown that cadmium may displace zinc in native metalloproteins in vitro (10), our data provide the first evidence that cadmium-zinc exchange may also occur in vivo during protein synthesis and folding. Exchange in the reverse direction appears to be of physiological relevance, as zinc addition prevented cadmium-induced protein aggregation and improved growth of cadmium-exposed cells (Fig. 3). Likewise, zinc addition has been shown to protect renal function against cadmium toxicity in rat (47). We conclude that cadmium primarily interferes with protein folding by acting on nascent polypeptides, probably by interacting with exposed thiol groups, be they ligands of zinc ions or free sulfhydryl groups, or destined to form disulfide bonds.

Protein aggregation may contribute to cadmium toxicity.

Cells that cannot efficiently protect the proteome from cadmium-induced aggregation or clear the cytosol of protein aggregates are sensitized to cadmium, suggesting that protein aggregation may contribute to cadmium toxicity. First, cells defective in proteasomal gene expression (rpn4Δ mutant) showed a delay in clearance of cadmium-induced protein aggregates and enhanced cadmium sensitivity compared to wild-type cells (Fig. 1). This observation extends previous reports implicating the ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis pathway in resistance to cadmium (31, 32). Second, compared to wild-type cells, the gsh1Δ and ycf1Δ mutants accumulated more aggregated proteins and were inefficient in aggregate clearance (Fig. 5) and more cadmium sensitive (40, 41). Cadmium-exposed yeast cells strongly induce expression of genes in the GSH biosynthesis pathway and accumulate large amounts of reduced GSH (35, 36). Likewise, expression of the vacuolar ABC transporter Ycf1 is enhanced during cadmium exposure (38). Our data suggest that the purpose of this response is to increase the cellular capacity to bind (by GSH), sequester (by Ycf1), and thereby diminish the concentration of free cadmium in the cytosol to protect the proteome from cadmium-induced damage.

Protein aggregates can be toxic to cells by different mechanisms. In addition to losing their specific biological function, aggregated proteins may affect membrane integrity (48) and, importantly, may induce other metastable or stress-labile proteins to aggregate (49). Thus, a chain reaction of protein aggregation may propagate in the cell if a minority of initially misfolded proteins induce the aggregation of other cellular proteins. We show here that cadmium-aggregated proteins can act as seeds that catalytically increase the rate and yield of aggregation of other native proteins (Fig. 6). Cadmium-triggered seeds of G6PDH, after removal of excess free cadmium, strongly increased the misfolding of other proteins. Moreover, our in vitro data indicated that chaperone-assisted refolding was more susceptible to cadmium seeds than spontaneous refolding. Many molecular chaperones, such as Hsp104 (20), ClpB (21), GroEL (50), and DnaK (43), act as polypeptide-unfolding enzymes that specifically bind to misfolded and aggregated protein substrates and use ATP hydrolysis to unfold them into natively refolded low-affinity products. We found that cadmium-G6PDH seeds at half the concentration of denatured luciferase decreased the yield of luciferase refolding by the KJE chaperone system by half (Fig. 6F). Apparently, the cadmium seeds induce misfolded luciferase to become more resistant to KJE unfoldases. Alternatively, cadmium seeds might irreversibly bind to DnaK and/or DnaJ, thereby preventing them from acting as unfolding chaperones. Indeed, an additional cause of the toxicity of misfolded proteins is their acting as inhibitors of protein unfoldases (e.g., Hsp70, Hsp104, and Hsp60), ATP-fueled proteases (e.g., Lon and ClpAB), or the proteasome. Normally, unfolding chaperones iteratively bind to misfolded polypeptide substrates and unfold and release them to refold to the native state or release them for degradation. However, some substrates fail to dissociate from the unfoldases and may then act as competitive inhibitors of chaperones and proteases, thereby poisoning the cells (4).

Interestingly, zinc cannot prevent further aggregation once primary aggregates induced by cadmium have been formed (Fig. 3F). Likewise, addition of CHX to cells at a time at which cadmium-induced aggregates had already been formed could not prevent further misfolding (see Fig. S6 in the supplemental material). These in vivo observations support the notion that cadmium-induced aggregates may act as seeds in a gain-of-function mechanism, causing misfolding and aggregation of other labile proteins. Our in vitro data suggest that cadmium-induced seeds are more effective inhibitors of protein folding than heat-induced seeds (Fig. 6). Although stable aggregates formed by cadmium treatment produced smaller aggregates than heat-treated luciferase (see Fig. S5 in the supplemental material), thorough examination of aggregate size distribution will be required to firmly establish whether heat- and cadmium-induced aggregates have distinct sizes in general. Seed-induced proteinaceous aggregation has been postulated to contribute to many protein-misfolding diseases (1–3, 51). Cadmium exposure has been associated with neurological disorders, including Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases. The mechanism described here, cadmium-induced formation of primary seeds that can further trigger aggregation of other proteins, may contribute to cadmium toxicity and pathogenicity.

Conclusions.

In vivo experiments with yeast cells showed that cadmium targets nascent cytosolic proteins and triggers their aggregation. This novel mode of cadmium action operates concurrently with previously described toxicity mechanisms (10–12). Thus, xenobiotic metals and metalloids, like cadmium (this work) and As(III) (14), interfere with protein folding in living cells, with nascent or nonfolded proteins being their prime targets. Other metals and metalloids might also perturb protein folding and manifest their toxicity through similar mechanisms. A better understanding of these mechanisms may provide important insights into the contribution of metals and metalloids to protein-misfolding diseases.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast strains and growth conditions.

The S. cerevisiae strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. The yeast strains were routinely grown on minimal synthetic complete (SC) medium (0.67% yeast nitrogen base) supplemented with auxotrophic requirements and 2% glucose as a carbon source. The gsh1Δ mutant and the corresponding wild type were grown in YPD medium. Growth assays were carried out in liquid medium using a microcultivation approach as previously described (14, 52). CdCl2, ZnCl2, sodium arsenite (NaAsO2), and CHX (all from Sigma-Aldrich) were added to the cultures at the indicated concentrations.

TABLE 1.

S. cerevisiae strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotype | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| BY4741 | MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 | EUROSCARF |

| HSP104-GFP | BY4741 HSP104-GFP-HIS3-MX6 | Invitrogen |

| HSP104-GFP rpn4Δ | BY4741 HSP104-GFP-HIS3-MX6 rpn4Δ::KanMX4 | 14 |

| HSP104-GFP gsh1Δ | BY4741 HSP104-GFP-HIS3-MX6 gsh1Δ::KanMX4 | 57 |

| HSP104-GFP his3Δ | MATa his3Δ::kanMX4 HSP104::GFP-LEU2 can1Δ::STE2pr-Sp_his5 lyp1Δ ura3Δ0 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 LYS2+ | Beidong Liu (University of Gothenburg) |

| HSP104-GFP ycf1Δ | MATa yc1Δ::kanMX4 HSP104::GFP-LEU2 can1Δ::STE2pr-Sp_his5 lyp1Δ ura3Δ0 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 LYS2+ | Beidong Liu |

Microscopy.

Yeast cells expressing the Hsp104-GFP or Sis1-GFP (27) fusion protein were grown to mid-log phase in SC medium and treated with cadmium, zinc, arsenite, or heat (42°C) in the absence or presence of 0.1 mg/ml CHX. At the indicated time points, cell samples were fixed with formaldehyde for 30 min at room temperature and washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The GFP signals were observed using an Axiovert 200M (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging) fluorescence microscope equipped with Plan-Apochromat 1.40-numerical-aperture objectives and appropriate fluorescence light filter sets. Images were taken with a digital camera (AxioCamMR3) and processed with AxioVision software. To quantify protein aggregation, the total fraction of cells with aggregates/Hsp104-GFP (or Sis1-GFP) foci, as well as the fractions of cells showing 1 or 2 aggregates/cell and ≥3 aggregates/cell, was determined by visual inspection.

Labeling of newly synthesized proteins.

Newly synthesized proteins were labeled with [35S]methionine as previously described (14). Cells were first starved for 1 h in methionine-free SC medium and then labeled with 20 μCi/ml [35S]methionine for 5 min, quickly chilled, and treated with 300 μg/ml CHX to stop protein translation. The cells were disrupted with glass beads by vortexing (7 times for 30 s each time) in lysis buffer (20 mM sodium phosphate, pH 6.8, 10 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], 1 mM EDTA, 0.1% Tween, protease inhibitor cocktail, 3 mg/ml Zymolyase). After pelleting the cell debris, the supernatants were adjusted to equal protein concentrations in 800 μl, and the aggregated proteins were pelleted at 16,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C. Membrane proteins were removed by washing twice with 750 μl washing buffer (2% Nonidet NP-40 substitute [Fluka], 20 mM sodium phosphate, pH 6.8, protease inhibitor cocktail), centrifuging at 16,000 × g for 20 min each time, and the final aggregated protein extract was resuspended in 40 μl of SDS loading buffer (20% glycerol, 4% SDS, 100 mM Tris-HCl, 0,1% β-mercaptoethanol, bromophenol blue). Proteins in the total and aggregated fractions were separated by 10% reducing SDS-PAGE and visualized by autoradiography (Molecular Imager FX; Bio-Rad).

Measurements of intracellular cadmium levels.

Exponentially growing cells were exposed to CdCl2, and cells were collected at the indicated time points and washed twice in ice-cold water. The cell pellets were resuspended in water and boiled for 10 min, and after centrifugation, the supernatant was collected. The cadmium content of each sample was measured using a flame atomic absorption spectrometer (3300; PerkinElmer) as previously described (53) or using inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry (ICP-MS). The samples were diluted 14 to 20 times in 1% high-purity HNO3, and the samples were then analyzed using either a quadrupole ICP-MS (Thermo Scientific ICAP Q) in standard mode or a triple-quadrupole ICP-MS (Agilent 8800) with He as the collision gas. A multielement standard solution (Merck; VI CertiPur) was used for calibration, and indium was used as an internal standard.

In vitro assays. (i) Materials.

DnaK of E. coli was expressed and purified as described previously (43, 54), and its concentration was determined photometrically with a molar absorption coefficient ([cepsilon]280) of 14,500 M−1 cm−1. Purified DnaK contained <0.1 mol of nucleotide/mol DnaK and was stored in 25 mM HEPES-NaOH, 100 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, pH 7.4 at −80°C. DnaJ and GrpE of E. coli were gifts from H. J. Schönfeld (F. Hoffmann-La Roche, Basel, Switzerland). The stock solutions in 50 mM Tris-HCl and 100 mM NaCl, pH 7.7, were kept at −80°C. The concentrations of DnaJ and GrpE were determined photometrically, with ε277 values of 18,100 M−1 cm−1 and 2,720 M−1 cm−1, respectively. Photinus pyralis luciferase was obtained from Sigma. Leuconostoc mesenteroides G6PDH was from Fluka. The denatured proteins were stored in 6 M guanidinium HCl (GuHCl) and 50 mM Tris acetate, pH 7.5, at −20°C. Their concentrations were determined by the Bradford method with bovine serum albumin as a standard.

(ii) Preparation of chemically denatured luciferase.

Lyophilized luciferase (1 mg) was dissolved in 1 ml of 50 mM Tris acetate, 50 mM potassium perchlorate, and 15 mM magnesium acetate, pH 7.5, and precipitated by adding 5 volumes of acetone (−20°C; 30 min). After centrifugation for 10 min at 10,000 × g and 4°C, the pellet was redissolved in 1 ml of denaturing buffer (6 M GuHCl, 100 mM Tris acetate, 5 mM Tris [2-carboxyethyl]phosphine [TCEP], 50 mM potassium perchlorate, 15 mM magnesium acetate, pH 7.5) (13). The residual activity after exposure to acetone at −20°C was <1% of the initial native stock.

(iii) Preparation of stable luciferase and G6PDH aggregates.

To prepare heat-denatured seeds, native luciferase (2 μM) was incubated for 7 min at 42°C in 50 mM Tris acetate, 50 mM potassium perchlorate, and 15 mM magnesium acetate, pH 7.5. The residual activity after heat exposure was <2% of the initial native stock (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). For Luci-Cd seeds, luciferase was chemically denatured with 6 M GuHCl, diluted to 2 μM, and allowed to spontaneously refold for 2 h in the presence of 500 nM cadmium. At this cadmium concentration, the residual activity was <2% of the initial native luciferase activity (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). The inactive species thus prepared were separated from free cadmium using PDSpinTrap G-25 (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) columns (800 × g; 2 min), and the protein concentration was measured using a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay. The effects of different concentrations of misfolded inactive protein seeds thus prepared on the spontaneous and chaperone-assisted refolding of GuHCl-preunfolded luciferase were then examined. To prepare G6PDH seeds, native G6PDH (2 μM) was incubated for 7 min at 52°C in 50 mM Tris acetate, 50 mM potassium perchlorate, and 15 mM magnesium acetate, pH 7.5, with and without 500 nM cadmium, and the inactive G6PDH seeds were separated from free cadmium as described above for luciferase. Chaperone-assisted refolding was performed in the presence of 3.5 μM DnaK, 0.7 μM DnaJ, 1.4 μM GrpE, and 5 mM ATP at 25°C. All protein concentrations are expressed as micromolar protomer concentrations.

(iv) Luciferase and G6PDH activity assays.

Luciferase activity was measured as described previously (43, 55, 56). In the presence of oxygen, luciferase catalyzes the conversion of d-luciferin and ATP into oxiluciferin, CO2, AMP, PPi, and photons. Generated photons were counted with a Victor Light 1420 luminescence counter from Perkin-Elmer. The activity of G6PDH was determined by measuring the increase in NADH concentration at 340 nm. The assay solution (500 μl) contained 3 mM glucose 6-phosphate and 0.15 mM NAD+ in 200 mM Tris acetate, pH 7.5. All assays were carried out at 25°C.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Magdalena Migocka (University of Wroclaw) for cadmium measurements, Beidong Liu (University of Gothenburg) for providing strains, Simon Alberti (Max Planck Institute of Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics, Dresden, Germany) for providing plasmids, and Hans-Joachim Schönfeld (F. Hoffmann-La Roche, Basel, Switzerland) for providing DnaJ and GrpE.

This work was supported by grants from the Swedish Research Council (VR) (grant number 621-2014-4597) and the foundation Åhlén Stiftelsen (grant number mC33/h14) to M.J.T.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/MCB.00490-16.

REFERENCES

- 1.Valastyan JS, Lindquist S. 2014. Mechanisms of protein-folding diseases at a glance. Dis Model Mech 7:9–14. doi: 10.1242/dmm.013474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tyedmers J, Mogk A, Bukau B. 2010. Cellular strategies for controlling protein aggregation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 11:777–788. doi: 10.1038/nrm2993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hipp MS, Park SH, Hartl FU. 2014. Proteostasis impairment in protein-misfolding and -aggregation diseases. Trends Cell Biol 24:506–514. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2014.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goloubinoff P. 2016. Mechanisms of protein homeostasis in health, aging and disease. Swiss Med Wkly 146:w14306. doi: 10.4414/smw.2016.14306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang B, Du Y. 2013. Cadmium and its neurotoxic effects. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2013:898034. doi: 10.1155/2013/898034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caudle WM, Guillot TS, Lazo CR, Miller GW. 2012. Industrial toxicants and Parkinson's disease. Neurotoxicology 33:178–188. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2012.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chin-Chan M, Navarro-Yepes J, Quintanilla-Vega B. 2015. Environmental pollutants as risk factors for neurodegenerative disorders: Alzheimer and Parkinson diseases. Front Cell Neurosci 9:124. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2015.00124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gong G, O'Bryant SE. 2010. The arsenic exposure hypothesis for Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 24:311–316. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e3181d71bc7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tamás MJ, Sharma KS, Ibstedt S, Jacobson T, Christen P. 2014. Heavy metals and metalloids as a cause for protein misfolding and aggregation. Biomolecules 4:252–267. doi: 10.3390/biom4010252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maret W, Moulis J-M. 2013. The bioinorganic chemistry of cadmium in the context of its toxicity, p 1–29. In Sigel A, Sigel H, Sigel RK (ed), Cadmium: from toxicity to essentiality. Springer, Doordrecht, Netherlands. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wysocki R, Tamás MJ. 2010. How Saccharomyces cerevisiae copes with toxic metals and metalloids. FEMS Microbiol Rev 34:925–951. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2010.00217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beyersmann D, Hartwig A. 2008. Carcinogenic metal compounds: recent insight into molecular and cellular mechanisms. Arch Toxicol 82:493–512. doi: 10.1007/s00204-008-0313-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sharma SK, Goloubinoff P, Christen P. 2008. Heavy metal ions are potent inhibitors of protein folding. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 372:341–345. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.05.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jacobson T, Navarrete C, Sharma SK, Sideri TC, Ibstedt S, Priya S, Grant CM, Christen P, Goloubinoff P, Tamás MJ. 2012. Arsenite interferes with protein folding and triggers formation of protein aggregates in yeast. J Cell Sci 125:5073–5083. doi: 10.1242/jcs.107029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gardarin A, Chedin S, Lagniel G, Aude JC, Godat E, Catty P, Labarre J. 2010. Endoplasmic reticulum is a major target of cadmium toxicity in yeast. Mol Microbiol 76:1034–1048. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Le QG, Ishiwata-Kimata Y, Kohno K, Kimata Y. 2016. Cadmium impairs protein folding in the endoplasmic reticulum and induces the unfolded protein response. FEMS Yeast Res 16:fow049. doi: 10.1093/femsyr/fow049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hiramatsu N, Kasai A, Du S, Takeda M, Hayakawa K, Okamura M, Yao J, Kitamura M. 2007. Rapid, transient induction of ER stress in the liver and kidney after acute exposure to heavy metal: evidence from transgenic sensor mice. FEBS Lett 581:2055–2059. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.04.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu F, Inageda K, Nishitai G, Matsuoka M. 2006. Cadmium induces the expression of Grp78, an endoplasmic reticulum molecular chaperone, in LLC-PK1 renal epithelial cells. Environ Health Perspect 114:859–864. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mogk A, Bukau B. 2004. Molecular chaperones: structure of a protein disaggregase. Curr Biol 14:R78–R80. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2003.12.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Glover JR, Lindquist S. 1998. Hsp104, Hsp70, and Hsp40: a novel chaperone system that rescues previously aggregated proteins. Cell 94:73–82. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81223-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goloubinoff P, Mogk A, Zvi AP, Tomoyasu T, Bukau B. 1999. Sequential mechanism of solubilization and refolding of stable protein aggregates by a bichaperone network. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96:13732–13737. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.24.13732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Erjavec N, Larsson L, Grantham J, Nyström T. 2007. Accelerated aging and failure to segregate damaged proteins in Sir2 mutants can be suppressed by overproducing the protein aggregation-remodeling factor Hsp104p. Genes Dev 21:2410–2421. doi: 10.1101/gad.439307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaganovich D, Kopito R, Frydman J. 2008. Misfolded proteins partition between two distinct quality control compartments. Nature 454:1088–1095. doi: 10.1038/nature07195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kawai R, Fujita K, Iwahashi H, Komatsu Y. 1999. Direct evidence for the intracellular localization of Hsp104 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by immunoelectron microscopy. Cell Stress Chaperones 4:46–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lum R, Tkach JM, Vierling E, Glover JR. 2004. Evidence for an unfolding/threading mechanism for protein disaggregation by Saccharomyces cerevisiae Hsp104. J Biol Chem 279:29139–29146. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403777200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yan W, Craig EA. 1999. The glycine-phenylalanine-rich region determines the specificity of the yeast Hsp40 Sis1. Mol Cell Biol 19:7751–7758. doi: 10.1128/MCB.19.11.7751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Malinovska L, Kroschwald S, Munder MC, Richter D, Alberti S. 2012. Molecular chaperones and stress-inducible protein-sorting factors coordinate the spatiotemporal distribution of protein aggregates. Mol Biol Cell 23:3041–3056. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E12-03-0194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Park SH, Kukushkin Y, Gupta R, Chen T, Konagai A, Hipp MS, Hayer-Hartl M, Hartl FU. 2013. PolyQ proteins interfere with nuclear degradation of cytosolic proteins by sequestering the Sis1p chaperone. Cell 154:134–145. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Choe YJ, Park SH, Hassemer T, Korner R, Vincenz-Donnelly L, Hayer-Hartl M, Hartl FU. 2016. Failure of RQC machinery causes protein aggregation and proteotoxic stress. Nature 531:191–195. doi: 10.1038/nature16973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miller SB, Mogk A, Bukau B. 2015. Spatially organized aggregation of misfolded proteins as cellular stress defense strategy. J Mol Biol 427:1564–1574. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2015.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Medicherla B, Goldberg AL. 2008. Heat shock and oxygen radicals stimulate ubiquitin-dependent degradation mainly of newly synthesized proteins. J Cell Biol 182:663–673. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200803022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jungmann J, Reins HA, Schobert C, Jentsch S. 1993. Resistance to cadmium mediated by ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis. Nature 361:369–371. doi: 10.1038/361369a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mannhaupt G, Schnall R, Karpov V, Vetter I, Feldmann H. 1999. Rpn4p acts as a transcription factor by binding to PACE, a nonamer box found upstream of 26S proteasomal and other genes in yeast. FEBS Lett 450:27–34. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(99)00467-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Singer MA, Lindquist S. 1998. Multiple effects of trehalose on protein folding in vitro and in vivo. Mol Cell 1:639–648. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80064-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fauchon M, Lagniel G, Aude JC, Lombardia L, Soularue P, Petat C, Marguerie G, Sentenac A, Werner M, Labarre J. 2002. Sulfur sparing in the yeast proteome in response to sulfur demand. Mol Cell 9:713–723. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00500-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lafaye A, Junot C, Pereira Y, Lagniel G, Tabet JC, Ezan E, Labarre J. 2005. Combined proteome and metabolite-profiling analyses reveal surprising insights into yeast sulfur metabolism. J Biol Chem 280:24723–24730. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502285200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tang L, Qiu R, Tang Y, Wang S. 2014. Cadmium-zinc exchange and their binary relationship in the structure of Zn-related proteins: a mini review. Metallomics 6:1313–1323. doi: 10.1039/C4MT00080C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li ZS, Lu YP, Zhen RG, Szczypka M, Thiele DJ, Rea PA. 1997. A new pathway for vacuolar cadmium sequestration in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: YCF1-catalyzed transport of bis(glutathionato)cadmium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 94:42–47. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.1.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grant CM, MacIver FH, Dawes IW. 1996. Glutathione is an essential metabolite required for resistance to oxidative stress in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr Genet 29:511–515. doi: 10.1007/BF02426954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Szczypka MS, Wemmie JA, Moye-Rowley WS, Thiele DJ. 1994. A yeast metal resistance protein similar to human cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) and multidrug resistance-associated protein. J Biol Chem 269:22853–22857. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu AL, Moye-Rowley WS. 1994. GSH1, which encodes gamma-glutamylcysteine synthetase, is a target gene for yAP-1 transcriptional regulation. Mol Cell Biol 14:5832–5839. doi: 10.1128/MCB.14.9.5832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gidalevitz T, Ben-Zvi A, Ho KH, Brignull HR, Morimoto RI. 2006. Progressive disruption of cellular protein folding in models of polyglutamine diseases. Science 311:1471–1474. doi: 10.1126/science.1124514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sharma SK, De los Rios P, Christen P, Lustig A, Goloubinoff P. 2010. The kinetic parameters and energy cost of the Hsp70 chaperone as a polypeptide unfoldase. Nat Chem Biol 6:914–920. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mattoo RU, Farina Henriquez Cuendet A, Subanna S, Finka A, Priya S, Sharma SK, Goloubinoff P. 2014. Synergism between a foldase and an unfoldase: reciprocal dependence between the thioredoxin-like activity of DnaJ and the polypeptide-unfolding activity of DnaK. Front Mol Biosci 1:7. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2014.00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Banecki B, Liberek K, Wall D, Wawrzynow A, Georgopoulos C, Bertoli E, Tanfani F, Zylicz M. 1996. Structure-function analysis of the zinc finger region of the DnaJ molecular chaperone. J Biol Chem 271:14840–14848. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.25.14840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Andreini C, Banci L, Bertini I, Rosato A. 2006. Zinc through the three domains of life. J Proteome Res 5:3173–3178. doi: 10.1021/pr0603699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jacquillet G, Barbier O, Cougnon M, Tauc M, Namorado MC, Martin D, Reyes JL, Poujeol P. 2006. Zinc protects renal function during cadmium intoxication in the rat. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 290:F127–F137. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00366.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lashuel HA, Hartley D, Petre BM, Walz T, Lansbury PT Jr. 2002. Neurodegenerative disease: amyloid pores from pathogenic mutations. Nature 418:291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hinault MP, Ben-Zvi A, Goloubinoff P. 2006. Chaperones and proteases: cellular fold-controlling factors of proteins in neurodegenerative diseases and aging. J Mol Neurosci 30:249–265. doi: 10.1385/JMN:30:3:249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Priya S, Sharma SK, Sood V, Mattoo RU, Finka A, Azem A, De Los Rios P, Goloubinoff P. 2013. GroEL and CCT are catalytic unfoldases mediating out-of-cage polypeptide refolding without ATP. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110:7199–7204. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1219867110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tipping KW, van Oosten-Hawle P, Hewitt EW, Radford SE. 2015. Amyloid fibres: inert end-stage aggregates or key players in disease? Trends Biochem Sci 40:719–727. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2015.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Warringer J, Blomberg A. 2003. Automated screening in environmental arrays allows analysis of quantitative phenotypic profiles in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 20:53–67. doi: 10.1002/yea.931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Thorsen M, Di Y, Tangemo C, Morillas M, Ahmadpour D, Van der Does C, Wagner A, Johansson E, Boman J, Posas F, Wysocki R, Tamás MJ. 2006. The MAPK Hog1p modulates Fps1p-dependent arsenite uptake and tolerance in yeast. Mol Biol Cell 17:4400–4410. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-04-0315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Feifel B, Sandmeier E, Schönfeld HJ, Christen P. 1996. Potassium ions and the molecular-chaperone activity of DnaK. Eur J Biochem 237:318–321. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0318n.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Natalello A, Mattoo RU, Priya S, Sharma SK, Goloubinoff P, Doglia SM. 2013. Biophysical characterization of two different stable misfolded monomeric polypeptides that are chaperone-amenable substrates. J Mol Biol 425:1158–1171. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2012.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bischofberger P, Han W, Feifel B, Schönfeld HJ, Christen P. 2003. d-Peptides as inhibitors of the DnaK/DnaJ/GrpE chaperone system. J Biol Chem 278:19044–19047. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300922200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Talemi SR, Jacobson T, Garla V, Navarrete C, Wagner A, Tamás MJ, Schaber J. 2014. Mathematical modelling of arsenic transport, distribution and detoxification processes in yeast. Mol Microbiol 92:1343–1356. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.